Years after the ambiguity and hardship in life will all make sense~

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Given the amount of surveillance, can social activism prevail in China?

China Social Stability

In China, the maintenance of social stability is crucial in the view of the China government officials. Hence, it is prohibited for the citizens to gather and protest. Even if the action is in an online collective manner, it is seen as a destabilizing threat. Online activism has a high potential for the cooperative movement, where China officials have paid close attention to through the country's censorship procedures (Zeng 2020, p. 181).

China's Censorship

China's censorship measures were introduced in 1996, and it is commonly referred to as the "the Great Firewall of China", or the official name "The Golden Shield Project", in which the policy prohibits any content deemed as harmful to the Chinese government, and is determined solely by State censors (Gu 2020, p. 290). Therefore, for the government to have a more comprehensive media control in the country, the Great Firewall has bans users in China from accessing foreign media. For example, news media such as The Wall Street Journal, BBC, The New York Times, and even social networking sites, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and YouTube (Zucchi 2021). LinkedIn, the last big founded American social media in China, has recently joined the list of banned social networking sites in China due to the operational challenges in cooperating with the local censorship regulation (Saul 2021).

youtube

What are the guidelines?

On August 10, 2013, China's State Internet Information Office had announced a series of guidelines named the 'Seven Bottom Lines' during the inaugural Internet conference informing the Internet users to obey. The 'Seven Bottom Lines' policies indicate that Internet users should be careful when releasing content on the Internet of the seven factors: authenticity of the information, socialist system, morality, public order, laws and regulations, national interest, and the citizens' legitimate interest. Failure to comply with the policy can lead to negative consequences of 'drinking tea' - brought into questioning the police, deleting, or blocking the user's social media account. As information disseminated on Internet rapidly, the China government has placed the monitoring responsibility upon the Internet company to regulate the illegal content, in which China's government publically warned Weibo the inefficient censorship could result in shutting down on the company. Thence, within the two months of China's State Internet Information Office conference, Sina, who owns Weibo, has shut down 103,673 accounts on its platform (Luqiu 2017, pp. 128-132).

Social activism activity

The #MeToo movement is a social campaign to fight sexual harassment, violence, and abuse (Gill & Rahman-Jones 2020). Six years after the sexual harassment incident, Sophia Gyang Xueqin was inspired by the #MeToo campaign and took to WeChat to express her sexual harassment experience and created a poll to raise conversation and awareness of harassment issues in China (Denyer & Wang 2018). However, China has taken a cautious approach to the #MeToo movement as it worries it may threaten its male-dominated halls of power stability (Hernandex 2018).

Although #MeToo hashtags were censored in China social media, the platform users implemented a camouflage strategy by modifying the content to circumvent the censorship. For example, with rice bunny's pronunciation in Mandarin sounds similar to Me Too, the platform users have used #ricebunny or emoji of rice bowls and rabbit as a code name in discussing the issue. Moreover, the platform users have also utilized Northern Chinese and Sichuan dialects term that refers to Me Too on WeChat to circumvent the censorship (Zeng 2020, pp. 182-185).

Additionally, as the action of avoiding censorship through posting text in image format becomes noticed, text-detection algorithms were further developed to detect text-embedded images. Again, the platform users' creativity has a trick to challenge the image detection function by rotating the text-image upside down or slightly tilted when publishing it on social media to decrease censorship (Zeng 2020, pp. 182-185).

In summary

Social activism can be complex and challenging in China due to government control and the sophisticated technological censorship detection on social media. Through text and image detection, social media censorship in China has also sparked platform users' creativity in modifying the content to circumvent censorship; social activists also used the virtual network provider (VPN) to avoid the censorship (Ritzen 2018). However, actions may lead to facing potential consequences of the account being deleted, blocked, or interrogated by the police officers.

Reference List

Denyer, S & Wang, AZ 2018, ‘Chinese women reveal sexual harassment but #MeToo movement struggles for air’, The Washington Post, 9 January, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/chinese-women-reveal-sexual-harassment-but-metoo-movement-struggles-for-air/2018/01/08/ac591c26-cc0d-4d5a-b2ca-d14a7f763fe0_story.html>.

Gill, G & Rahman-Jones, I 2020, ‘Me Too founder Tarana Burke: Movement is not over’, BBC News, 9 July, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-53269751>.

Gu, CY 2020, ‘Peering past the firewall: The gender of disobedience and social control in Mainland Chian’, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 290-293, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14680777.2020.1720348>.

Hernandez, JC 2018, ‘China���s #MeToo: How a 20-Year-Old Rape Case Became a Rallying Cry’, The New York Times, 9 April, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/09/world/asia/china-metoo-gao-yan.html>.

Luqiu, LR 2017, ‘The cost of humour: Political satire on social media and censorship in China’, Global Media and Communication, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 123-138, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1742766517704471>.

Ritzen, Y 2018, ‘Meet the activists fighting the Great Chinese Firewall’, Aljazeera, 21 June, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/6/21/meet-the-activists-fighting-the-great-chinese-firewall>.

Saul, D 2021, ‘Microsoft’s LinkedIn leaves China following charges of censorship’, Forbes, 14 October, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/dereksaul/2021/10/14/linkedin-leaves-china-following-charges-of-censorship/?sh=5f760a9e4fc7>.

Zeng, J 2020, ‘#MeToo as connective action: A study of the anti-sexual violence and anti-sexual harassment campaigns on Chinese social media in 2018’, Journalism Practice, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 171-190, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17512786.2019.1706622>.

Zucchi, K 2021, ‘Why Facebook is banned in China and how to access it’, Investopedia, 5 June, viewed 20 November 2021, <https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/042915/why-facebook-banned-china.asp#:~:text=1%20That's%20because%20the%20service,the%20interest%20of%20the%20state>.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Has the Covid-19 pandemic changed the public perception of gaming?

Social Gaming Networks

Social gaming networks are Internet-based computer networks that numerous users inhabit simultaneously as a community, enabling interaction, communication, relationships building, and exchange of information to play games (Alturki, Alshwihi & Algarni 2020; p. 97383; Gong et al. 2020, p. 658).

Gaming Perception and Potential Adverse Effect of Excessiveness

In the eyes of the public, gaming activities may be viewed negatively. For instance, some may consider social gamers irresponsible as gaming provides a fantasy environment and an escape from real-life problems. Besides, gaming may be seen as unproductive or an addiction. As gaming becomes more portable, individuals can play anywhere, from attending class, during meals, waiting for the subway, or crossing the street. Findings from eMarketer on 20,929 online users survey show that 47% of users played an average range of one to four hours daily, while 11% played over five hours each day. On the WeChat-linked social battle game, Arena of Valor, the 200 registered users play an average of six hours per week. Some obsessive gamers may also interrupt their sleeping schedule to play longer. Obsessive gaming situations may lead to adverse health, mood, social, or even deadly consequences. An examplar, after playing online social games nonstop for 40 hours, a Chinese user developed a cerebral infarction (Gong et al. 2020, pp. 657-658). This addictive gaming behavior has also resulted in China's government imposing a gaming curfew. Between the hours of 22:00 and 08:00, gamers under the age of 18 will not be allowed to play online. They will be limited to 90 minutes of gaming on weekdays. They will be limited to three hours of gaming (Video game addiction: China imposes gaming curfew for minors 2019).

Public Perception on Gaming since Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic led to an increase in experiencing social isolation, loneliness, and risk of depression due to the social distancing and quarantine to minimize the spread of the virus. As social gaming promotes social relationships, the application becomes a coping mechanism for many.

The game Farmville that links to Facebook is a game that encourages players' interaction. A type of Mimicry-simulation game where the player becomes a farmer performs agriculture activities such as raising livestock, growing and harvesting crops. Farmville encourages players to invite their social circle to join the game to build a neighborhood of farmers because Farmville's Ludus requires players to exchange the labor "materials" with a neighbor or friends to expand the farm. As Farmville is connected to Facebook, the player can publish exchange needs on the Facebook wall, which raises awareness to friends and family players to click on to help. Farmville's platform has enabled players to form rituals that develop social cohesion and increase engagement levels between friends and family. The exchange creates relationships and allows message leaving to spark communication (Burroughs 2014, pp. 152-162).

youtube

Additionally, the game Animal Crossing, released during the pandemic, has allowed players to better cope with loneliness and anxiety. Animal Crossing is a Mimicry-simulation game that enables users to create their deserted island village, replete with character personalization, interact with non-playable island people, and play cooperatively with up to eight real-life individuals (Lewis, Trojovsky & Jameson 2021, pp. 1-5). The Animal Crossing's Paidia to visit friends' islands has stimulated players to socialize virtually, allowing players to cope with loneliness, stress, and anxiety while in the Covid-19 pandemic, physical isolation (Zhu 2020, p. 158). Moreover, the pandemic has restricted and caused cancelation to many gatherings such as weddings and graduation ceremonies; players then took to Animal Crossing to hold temporary substitutes weddings and graduation ceremonies, inviting real-friends’ players to attend as a humorous celebration (Garst 2020).

Gaming has also been shared and streamed on social media platforms such as YouTube to interact with viewers, gain excitement and reaction, promoting an online gaming community.

youtube

youtube

Previously, the World Health Organization (WHO) has labeled game addiction as an indication of mental illness in 2019 and advised individuals to avoid being addicted to video games. However, since the pandemic, WHO has shifted its position on online gaming, from warning about its dangerous and addictive nature to complimenting its positive effects on socialization and stress management, urging people to stay at home and play games in 2020 (Kriz 2020, p. 405).

Conclusion

As Zhu (2020, p. 158) stated, over one-third of respondents say they chat to their online pals about difficulties they wouldn't tell an offline buddy, 75% of players made suitable friends, and 30% met a romantic partner through social gaming. In summary, if played moderately, social gaming can promote mental health benefits of decreasing loneliness, coping with stress, improving personal relationships with friends, families, and others.

Reference List

‘Video game addiction: China imposes gaming curfew for minors’ 2019, BBC News, 6 November, viewed 11 November 2021, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-50315960>.

Alturki, A, Alshwihi, N & Algarni, A 2020, ‘Factors influencing players’ susceptibility to social engineering in social gaming networks’, IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 97383-97391, viewed 10 November 2021, <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9096355>.

Burroughs, B 2014, ‘Facebook and FarmVille: A digital ritual analysis of social gaming’, Games and Culture, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 151-166, viewed 11 November 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1555412014535663?journalCode=gaca>.

Garst, A 2020, ‘The pandemic canceled their wedding so they held it in Animal Crossing’, The Washington Post, 2 April, viewed 11 November 2021, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/2020/04/02/animal-crossing-wedding-coronavirus/>.

Gong, X, Zhang, KZK, Chen, C, Cheung, CMK & Lee, MKO 2020, ‘Antecedents and consequences of

excessive online social gaming: A social learning perspective’, Information Technology & People, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 667-688, viewed 10 November 2021, <https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ITP-03-2018-0138/full/html>.

Kriz, WC 2020, ‘Gaming in the Time of COVID-19’, Simulation & Gaming, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 403-410, viewed 11 November 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1046878120931602>.

Lewis, JE, Trojovsky, M & Jameson, MM 2021, ‘New Social Horizons: Anxiety, isolation, and Animal Crossing during the COVID-19 pandemic’, vol. 2, pp. 1-7, viewed 11 November 2021, <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2021.627350/full>.

Zhu, L 2020, ‘The psychology behind video games during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Animal Crossing: New Horizons’, Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 157-159, viewed 11 November 2021, <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/hbe2.221>.

0 notes

Text

Are media representations of fans as 'weird' and 'overly emotional' fair?

What are Fan and Fandom?

Fan refers to an individual with a strong, positive emotional attachment to someone or something famous (Fuschillo 2018, p. 348). When the fan comes together as a group or community, sharing a common interest in a media object, it is known as fandom (Tsay-Vogel & Sanders 2017, pp. 32-33). Fandom also provides a social identity for individuals. For instance, people who are fans of the K-pop girl group Blackpink identify themselves as Blinks (Sng 2021).

Fan Stereotypes in Media

36-year-old Azusa Sakamoto frequently shares her love for Barbie on YouTube, showing her Barbie doll collections, Barbie room, and more, spending over $80,000 on Barbie's relevant purchase (Pike 2018). Akihiko Kondo received Hatsune Miku's fans' congratulations and encouragement through Twitter on Kondo's $18,000 marriage ceremony with the Hatsune Miku anime character (Reuters 2018). Oli London frequently shares his love for the K-pop BTS idol Jimin on social media and even his cosmetic plastic surgery message to look like Jimin on YouTube (Haasch 2021). The media tends to portray fans as abnormal, pathological people due to their high engagement behavior (Smutradontri & Gadavanij 2020, p. 3). For example, willingness to purchase anything with their favorite idols or program logo or image, unable to differentiate daily life from fantasy, and to spend significant time and effort in thinking thoughtfully of the topic can come across as culturally worthless (p. 193). However, is the media's negative stereotype on fandom truly fair to represent the whole community?

youtube

Barbie Fan: Azusa Sakamoto

youtube

Hatsune Miku Fan: Akihiko Kondo

youtube

BTS Jimin Fan: Oli London

Fan Production

Fan activities promote and spark creativity. An example is fan arts. The fan uses their drawing skills to draw the celebrity or characters and frequently posts it on social media to share their talented artwork and hope to get noticed. On Instagram, #FanArtFriday, actor Deepika Padukone constantly repost fans' sketches, animated illustrations, and painting of her on Instagram Stories function to support and show appreciation to her fans (Bhatt 2021). Due to celebrities' social media endorsement of fans' artwork, it provides credibility and benefits the fans. For instance, South Indian actors - Tovino Thomas and Anusree sharing Punith fan art posts- increased Punith's Instagram popularity and provided Punith work opportunities daily with 10-20 inquiries of RS1,500 and Rs7,000 charges per assignment (Bhatt 2021).

The current Covid-19 pandemic has negatively impacted many individuals' mental health due to the environmental changes of one's daily life and physical interaction restrictions (Alfonseca 2021). Working as a frontline person during the pandemic, Michelle Anderson faced similar difficulty, worrying and stressing if she had contracted the virus. To cope with the worries, Anderson turned to cosplay, planning, creating the outfits, and dressing up as a fictional character to share on TikTok for comfort (Orsini 2021). As physical Cosplay conversations are canceled, many moves to online events such as #DragonConGoesVirtual on Twitter, where fans turn to show their cosplay creation and connect with others throughout the pandemic (Orisini 2021).

Michelle Anderson (Tiktok username: Tatted Poodle), dressed as Shinra Kusakabe records a TikTok video.

Fan activism

Apart from the 'save the show' campaign, such as the Fringe show fan activism on Twitter, fan activism can go beyond TV shows to change societal issues (Guerrero-Pico 2017, p. 2086). An examplar, celebrity Lady Gaga fans, Little Monsters, have been known for their effort in partaking in the Don't Ask Don't Tell (DADT) policy activism on YouTube and Twitter. The DADT is a policy that prohibits the US military from disclosing or knowing the sexual orientation of members or candidates and rejecting or refusing openly gay or bisexual individuals from military service. Lady Gaga has posted a video regarding the DADT situation on YouTube with two million views, urgency fans' involvement (Bennett 2014, p. 144). In the video Lady Gaga stated:

"I am here to be a voice for my generation, not the generation of the senators who are voting, but for the youth of this country, the generation that is affected by this law and whose children will be affected. [...] Will you support repealing this law on Tuesday and pledge to them that no American's life is more valuable than another? For those watching that would like to reach out Celebrity Studies 145 to their Senators and ask for their vote to repeal Don't Ask Don't Tell, you can log on to www. sldn.org/gaga or you can call 202-224-3121, like I'm going to do, right now!"

This has prompted many Lady Gaga fans to record videos on YouTube of themselves implementing Gaga's direct action advice and calling their senators, causing many to phone calls received by the Senator. The fans' activism has brought awareness to the Senator regarding the DADT issues and successfully repealed the law on December 18, 2010 (Bennett 2014, p. 146 ).

Reference List

Alfonseca, K 2021, ‘Anxiety, depression fluctuated with COVID-19 waves: Study’, ABC News, 9 October, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://abcnews.go.com/Health/anxiety-depression-fluctuated-covid-19-waves-study/story?id=80475431>.

Bennett, L 2014, ‘If we stick together we can do anything’: Lady Gaga fandom, philanthropy and activism through social media’, Celebrity Studies, vol. 5, no. 1-2, pp. 138-152, viewed 3 November 2021, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19392397.2013.813778>.

Bhatt, S 2021, ‘#FanArt becomes an instant formula for amateur artists to gain popularity on Instagram’, The Economic Times, 25 May, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/fanart-trends-on-instagram-during-lockdown/articleshow/77814451.cms?from=mdr>.

Fuschillo, G 2018, ‘Fans, fandoms, or fanaticism?’, Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 347-365, viewed 11 October 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1469540518773822?casa_token=20yRitrrY2wAAAAA:fBCDO0eYf12a9i1MTgNwsbi-4t9uK2yM-HjhtnYPMTYIiFlP0ZA1ap_hyQ5e-pIqJ0kj5ZrV7vDqYw>.

Guerrero-Pico, M 2017, ‘#Fringe, audiences, and fan labor: Twitter activism to save a TV show from cancellation’, International Journal of Communication, vol. 11, pp. 2071-2092, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4020>.

Haasch, P 2021, ‘A British influencer got plastic surgery to look like a BTS member. Now, they're facing backlash for saying they identify as Korean’, Insider, 25 June, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://www.insider.com/oli-london-white-influencer-criticized-for-identifying-as-korean-2021-6>.

Orsini, L 2021, ‘All dressed up with nowhere to go: Cosplaying in the pandemic’, The Washington Post, 25 June, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/2021/06/25/cosplay-in-the-pandemic/>.

Pike, MR 2018, ‘Inside the REAL Barbie Dreamhouse: Superfan transforms her apartment into a hot pink shrine to her favourite doll - complete with $80,000-worth of merchandise’, Daily Mail Online, 17 May, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-5739769/Barbie-fan-transforms-Los-Angeles-apartment-Barbie-Dreamhouse.html>.

Smutradontri, P & Gadavanij, S 2020, ‘Fandom and identity construction: an analysis of Thai fans’ engagement with Twitter’, Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, vol. 7, no. 177, pp. 1-13, viewed 3 November 2021, <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-020-00653-1>.

Sng, S 2021, ‘Blackpink will no longer accept gifts from fans, only handwritten letters allowed’, The Straits Times, 14 October, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://www.straitstimes.com/life/entertainment/blackpink-will-no-longer-accept-gifts-from-fans-only-handwritten-letters-allowed>.

Sullivan, JL 2019, Media Audiences, Sage Publication, USA.

Reuters, T 2018, ‘Japanese man pledges to have, hold and cherish hologram pop star Hatsune Miku’, CBC News, 15 November, viewed 4 November 2021, <https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/hologram-marriage-1.4906711>.

Tsay-Vogel, M & Sanders, MS 2017, ‘Fandom and the search for meaning: Examining communal involvement with popular media beyond pleasure’, Psychology of Popular Media Culture, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 32-48, viewed 11 October 2021, <https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2015-22664-001.pdf>.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Discovering Breakthrough with Crowdsourcing and Crowdfunding in Social Media

What is crowdsourcing?

The act of numerous individuals collectively contributing ideas, opinions, or information related to the topic via social media or the internet is known as crowdsourcing (Hargrave 2021; Ghezzi 2018, pp. 343-344).

Companies Initiative in Engaging Crowds' Creative Developments

Lay's

In July 2012, PepsiCo's division - Frito-Lay- launched a crowdsourcing campaign named "Do Us A Flavor" on Facebook, inviting individuals to brainstorm ideas for the next Lay's potato chip flavor (Frito-Lay 2013). The crowdsourcing campaign strongly motivates participants to join because the grand winner will receive one million dollars or the new flavor's 1% net sales in 2013 (Durisin 2013). The contest lasted from July 20 to October 6, 2012; people gathered on Lay's Facebook page to submit their flavor recommendation, stating the flavor name, three potential ingredients, and a 140-character description or inspiration of the flavor, reaching 3.8 million entries on Facebook (CPS 2012; Frito-Lay 2013).

Frito-Lay invited the public to vote for the top flavor winner among the three finalists flavors: Cheesy Garlic Bread, Chicken & Waffles, and Sriracha derived from the 3.8 million Lay's Facebook entries (Frito-Lay 2013). PepsiCo worked with Facebook to create the "I'd Eat That" button to make the vote more memorable and relevant in replacing the usual "Like" button for voting purposes (CPS 2012). Additionally, voters would share their choice, providing opportunities for discussion and interaction with friends, family members, and the other contestants in head-and-head "flavor showdowns" (CPS 2012). In further decentralizing the campaign, #SaveGarlicBread, #SaveChickenWaffles, or #SaveSriracha were used by the Twitter users to vote for the desired winning flavor (Champagne 2013). The winner, Karen Weber-Mendham, stated that Karen had been continuously using the #SaveGarlicBread to increase the winning possibility throughout the voting period (Durisin 2013). Thanks to the crowds' collective intelligence in generating flavor ideas, Frito-Lay developed a new product.

What is Crowdfunding?

The allocation of a specific period to collectively raise funds from numerous individuals in financing a project is known as crowdfunding (Sahaym, Datta & Brooks 2021, p. 483; Smith 2021).

How Crowdfunding makes it Possible

From September 2019 till March 4, 2020, Australia was devastated by rising temperatures with a prolonged drought that resulted in mass bushfire incidents, burning more then 46 million acres of land (Center for Disaster Philanthropy c. 2020). Many took to social media to raise awareness of the Australian bushfire situations and funds to support the circumstances. For example, the Australian comedian Celeste Barber opened a Facebook page on January 3, 2020 (Masige 2020). The page asked others to donate collectively to support the Australian bushfire relief; the page grew funds from Australia and internationally from the United States, United Kingdom, Portugal, and Belgium and reached 20 million Australian dollars within 48 hours (BCC 2020; Masige 2020). Celebrities such as Kylie Minogue, Nicole Kidman, Elton John, and Chris Hemsworth also gather to donate and spread awareness of the Australian bushfire emergency (BCC 2020). The United States singer Pink has shared on Twitter that she has donated 500,000 dollars to the Australian fire services and provided a photo with a list of donation links to encourage post viewers to help support the funding (BCC 2020).

In summary, social media can be valuable in crowdsourcing and crowdfunding activities that rapidly gain support, ideas, and information to attain the desired goal.

Reference List

BCC 2020, ‘Australia fires: How the world has responded to the crisis’, 8 January, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-51024904>.Center for Disaster Philanthropy c. 2020, 2019-2020 Australian Bushfires, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disaster/2019-australian-wildfires/>.Champagne, C 2013, ‘How Lay’s got its chips to taste like chicken and waffles’, Fast Company, 13 February, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.fastcompany.com/1682425/how-lays-got-its-chips-to-taste-like-chicken-and-waffles>.CPS 2012, ‘Lay’s launches Do Us a Flavor contest’, 27 July, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.cspdailynews.com/snacks-candy/lays-launches-do-us-flavor-contest>.Durisin, M 2013, ‘Lay's reveals its newest potato chip flavor’, Insider, 9 May, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.businessinsider.com/winner-of-lays-new-flavor-contest-is-2013-5>.Frito-Lay 2013, Lay's brand issues last call for fans to vote on three finalist flavors in the Lay's "Do Us A Flavor" contest; contestants vying for $1 million or more in grand prize winnings, 22 April, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.fritolay.com/news/lay-s-brand-issues-last-call-for-fans-to-vote-on-three-finalist-flavors-in-the-lay-s-do-us-a-flavor-contest-contestants-vying-for-1-million-or-more-in-grand-prize-winnings>. Ghezzi, A, Gabelloni, D, Martini, A & Natalicchio, A 2018, ‘Crowdsourcing: A review and suggestions for future research’, International Journal of Management Reviews, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 343-363, viewed 27 October 2021, <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijmr.12135?casa_token=0dMwo06NrW0AAAAA%3A2VpnvWdv_bDnivZLxachTXZyiJsGWSBynitsVG8Bz-w5uzRpYL5Z449l2whPwTMJ_T7EHeV-3ph2rkM>.Hargrave, M 2021, ‘Crowdsourcing’, Investopedia, 16 May, viewed 27 October 2021, <https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/crowdsourcing.asp>.Masige, S 2020, ‘Celeste Barber’s bushfire fundraiser on Facebook is officially the largest in the platform’s history, raising over $50 million’, Business Insider Australia, 13 January, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.businessinsider.com.au/celeste-barber-facebook-bushfires-fundraiser-2020-1>.Sahaym, A, Datta, A & Brooks, S 2021, ‘Crowdfunding success through social media: Going beyond entrepreneurial orientation in the context of small and medium-sized enterprises’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 125, pp. 483-494, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014829631930551X?casa_token=C57FzcIgCDIAAAAA:mxLMj2CVXCKPMhHQaFSGXQNE-NXHW-MPBLd-eT4dZ4EHukvTru83GTWD5fqUwdz6XI3hdvc3WUM>.Smith, T 2021, ‘Crowdfunding’, Investopedia, 15 May, viewed 28 October 2021, <https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/crowdfunding.asp>.

0 notes

Text

Social Media in Spreading Information on Covid-19 in Malaysia

Coronavirus (Covid-19)

In late December 2019, Wuhan, China, detected an unknown virus on dozens of individuals who had visited a live animal market. On 2020 January 11, a 61-year-old-man passed away from the virus name Coronavirus (Schumaker 2020). The Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) contaminates respiratory disease that infects human liquid particles such as coughing, speaking, sneezing, singing, or breathing (WHO c. 2021). Before the lockdown procedures in various countries, the Coronavirus became a global pandemic as people traveled without precaution and preventive measures (Schumaker 2020). The Coronavirus caused an estimated death of 2 million people on January 18, 2021 (Tsao et al. 2021, p. 175).

Social Media on Covid-19 Information

In 2020, global social media users stood over 3.6 billion individuals and remained to grow (Statista Research Department 2021). Hence, in the Coronavirus pandemic emergency, social media platforms are vital tools in rapidly disseminating health-related information (Tsao et al. 2021, p. 192). For instance, the Malaysian government uses social media to provide the latest Covid-19 information to ensure effective communication on the pandemic risk. Examples, through Facebook pages named Crisis Preparedness and Response Center (CRPC), Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia (KKM), and Facebook online streaming from the Director-General of Health to inform the public daily Covid-19 situations (Dawi et al. 2021, pp. 2-3).

According to Liu (2021, p. 5), frequent exposure to Covid-19 details on social media evokes individuals' perception of personal responsibility to overcome the Covid-19 spread, leading to an increase in preventive actions. Additionally, peer influence on social media also influences one's behavior (Liu 2021, p. 5). An examplar, the rise of Covid-19 vaccination selfies posted across social media platforms, from celebrities to influencers to friends and family members, promotes one's interest in receiving vaccination due to the psychological traits in fear of missing out (Bresge 2021; Cochrane 2021). This circumstance was similar in Malaysia; based on personal experience, during June 2021, I noticed numerous distant relatives and friends started posting vaccination photos and videos of themselves receiving vaccination on Instagram. The photo trend then overcame my hesitation and fear of the potential adverse effect of the vaccination.

youtube

Additionally, social media also provided two-way communication. On October 1, 2021, a 12-year-old Malaysian boy was injected with an empty syringe that was supposed to contain the Covid-19 vaccine video uploaded onto Facebook. The video was shared 22,000 times and watched nearly 300,000 times, causing a significant discussion in the comment section (Ram 2021). The attention raised authority awareness, leading to police and armed force cooperating to investigate empty syringe issues in Malaysia (CNA 2021).

youtube

Fake News?

Raising awareness on Covid-19 health topic on social media sometimes may raise potential fake news. Referring to Apuke and Omar (2021, p. 11), people with altruistic traits - the enjoyment of helping others, tend to share fake news on social media due to the lack of attention towards the information's reliability. Mohd Fatrim Syah Abd Karim and Mohd Syuhaidi Abu Bakar (2021, p. 25) stated that Malaysian were unaware of the adverse effect of fake news sharing, creating 95% of WhatsApp messages regarding MCO and Covid-19 to be untrue. The situation leads the WhatsApp platform and Malaysian officials to handle misinformation as the effects ripple internationally (Mohd Fatrim Syah Abd Karim & Mohd Syuhaidi Abu Bakar 2021, p. 25). Instead of WhatsApp, I encountered receiving Covid-19 misinformation that the direct family members continuously shared via the Messenger application due to concern and caring without adequately investigating the credibility of the sources.

youtube

Reference List

Apuke, OD & Omar, B 2021, ‘Fake news and COVID-19: modelling the predictors of fake news

sharing among social media users’, Telematics and Informatics, vol. 56, pp. 1-16, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0736585320301349?casa_token=s3d6cdZMF3AAAAAA:4Hkl6-4lXKiKGDFOh8z6sFIHA-ViWM8RVh8bOmzKo-5jw_Ehc_hZwi5DHe6x5tV9djoCQQs6SJs>.

Bresge, A 2021, ‘Vaccine selfies are the new social media trend, but also a reminder of unequal access’, CTV News, 5 April, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/vaccine-selfies-are-the-new-social-media-trend-but-also-a-reminder-of-unequal-access-1.5374668>.

CNA 2021, ‘Malaysia COVID-19 task force cooperating with authorities over claims of improperly administered vaccine doses’, 19 July, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/malaysia-covid19-vaccine-empty-syringe-not-properly-administered-2049346>.

Cochrane, L 2021, ‘What a great shot! Vaccination selfies become the latest social media hit’, The Guardian, 31 January, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jan/31/what-a-great-shot-vaccination-selfies-become-the-latest-social-media-hit>.

Dawi, NM, Namazi, H, Hwang, HJ, Ismail, S, Maresova, P & Krejcar, O 2021, ‘Attitude towards protective behavior engagement during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia: The role of e-government and social media’, Original Research, vol. 9, pp. 1-8, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.609716/full>.

Khan, A 2021, I got vaccinated! dose one complete vlog, 22 June, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ZJ-_X1vnMo >.

Liu, PL 2021, ‘COVID-19 information on social media and preventive behaviors: Managing the pandemic through personal responsibility’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 277, pp. 1-8, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953621002604?via%3Dihub>.

Mohd Fatrim Syah Abd Karim & Mohd Syuhaidi Abu Bakar 2021, ‘Functions, influences & effects of WhatsApp use during the Movement Control Order (MCO) in Malaysia’, Asian Social Science, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 24-34, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350538732_Functions_Influences_Effects_of_WhatsApp_Use_During_the_Movement_Control_Order_MCO_in_Malaysia>.

Ram, S 2021, ‘Here's how a 12-year-old was mistakenly given empty jab of covid-19 vaccine at UM PPV’, Says, 2 October, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://says.com/my/news/citf-a-apologises-after-video-shows-12-year-old-was-given-empty-shot-of-covid-19-vaccine>.

Schumaker, E 2020, ‘Timeline: How coronavirus got started’, ABC News, 22 September, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://abcnews.go.com/Health/timeline-coronavirus-started/story?id=69435165>.

Statista Research Department 2021, ‘Number of global social network users 2017-2025’, Statista, 10 September, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/>.

The Economic Times 2020, Fake news on Covid-19: WhatsApp to limit sharing of frequently forwarded messages, 7 April, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C0i2zOo1sgE >.

The Star 2021, CITF-A apologises after 12-year-old mistakenly given empty jab at PPV UM, 2 October 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PqW2eopWlk0>.

Tsao, S, Chen, H, Tisseverasinghe, T, Yang, Y, Li, L & Butt, ZA 2021, ‘What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review’, Lancet Digit Health, vol. 3, pp. 175-194, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33518503/>.

WHO c. 2021, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), World Health Organization, viewed 21 October 2021, <https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1>.

0 notes

Text

Social media impact on Black Lives Matter protest

Civic culture is the sociocultural environment aspect that serves as conditions for people's engagement in public and political society (Dahlgreen 2009, p. 104). In 1619 American history, black African slavery treatment was typical (A&E Television Network 2021). With years of civilian participation that created numerous evolutions, American law, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, protected black African Americans for equal treatment (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration and Management n.d.).

However, was there indeed equality for black African Americans? On May 25, 2020, citizen journalism - ordinary people who act as journalists for a portion of the content creation process for mainstream journalism coverage, Darnella Frazier captured the police officer, Derek Chauvin forcing his knee onto George Floyd's neck during police custody. Floyd was later pronounced dead in hospital due to suffocation (Luo & Harrison 2019, p. 72; Kansara 2020; Deliso 2021). Frazier uploaded the eight-minute and 46 seconds video of Floyd's tragic treatment due to counterfeit money usage accusation onto Facebook, which went "viral" because of its raw content (Kansara 2020).

youtube

youtube

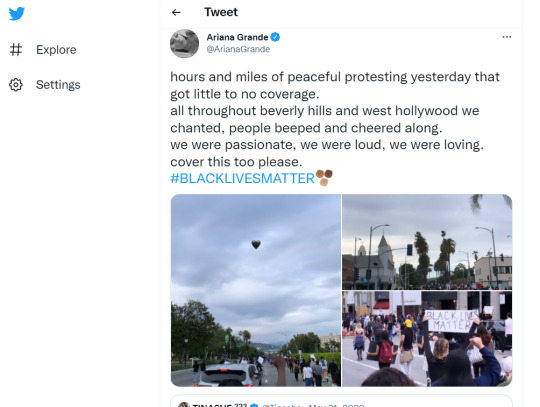

The video caused a massive reaction from the digital citizens, raising awareness, expressing discontent about Floyd's treatment, and demanding law enforcement changes via social media platforms (Anderson et al. 2020; Ho 2020). Black Lives Matter protestors shared photos with captions, videos of themselves and the surrounding situation with location tags, hashtags, and tagging others to express their support towards elevating recognition of the issues.

According to Anderson et al. (2020), from May 26 to June 7, the #BlackLivesMatter on Twitter was used 3.7 million times daily. On Instagram, 28 million users posted plain black squares with the caption #BlackoutTuesday to support the Black Lives Matter (BLM) social movement (Ho 2020). The intense social media discussion on Floyd's death also brought attention to previous less well-known cases and victims, such as Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, and Michael Brown (Maqbool 2020).

youtube

YouTube content creators, especially black Africans, uses the platform to voice out and share personal inequality treatment experiences due to the BLM problem. Based on data analytics, in June, Black Lives Matter's relevant video exhibited high spikes (Pettie, Buxton & Meenan 2020).

As celebrities, public figures, social media users joined in to post, share, forward, like, tweet, and retweet BLM content (Rao 2020; Beckman 2020). These actions elevated the activism upon racial treatment importance beyond America. Social media conversations on #BlackLivesMatter activities also took place in various countries such as South Korea, Brazil, France, Thailand, Canada, United Kingdom, and Spain (Beckman 2020). The BLM social media trends even prompted several countries to move out of the screen and physically protest in their own country (Kirby 2020).

Peace Black Lives Matter protest in South Korea (Kirby 2020)

Eventually, the voices and confrontation of the protest, may it be in-person or on social media, urges the official to take action. Minnesota Attorney General Keith Elisson charged Chauvin with the second-degree murder of George Floyd (Millhiser 2020). In addition, Elisson also charges the on-scene former police officers, Tou Thao, Thomas Lane, and Alexander Kueng, on aiding and abetting Floyd's murder (Millhiser 2020).

Reference List

A&E Television Network 2021, ‘Black history milestones: Timeline’, 27 April, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/black-history-milestones>.

Anderson, M, Barthel, M, Perrin, A & Vogels, EA 2020, ‘#BlackLives Matter surges on Twitter after George Floyd’s death’, Pew Research Center, 10 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/10/blacklivesmatter-surges-on-twitter-after-george-floyds-death/>.

Beckman, BL 2020, ‘#BlackLivesMatter saw tremendous growth on social media. Now what?’, Mashable, 2 July, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://sea.mashable.com/social-good/11349/blacklivesmatter-saw-tremendous-growth-on-social-media-now-what>.

Dahlgreen, P 2009, Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication and Democracy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Deliso, M 2021, ‘Timeline: The impact of George Floyd's death in Minneapolis and beyond’, ABC News, 22 April, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://abcnews.go.com/US/timeline-impact-george-floyds-death-minneapolis/story?id=70999322>.

Grande, A 2020, Peaceful Black Lives Matter protest, 1 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://twitter.com/ArianaGrande/status/1267161027042402304?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1267161027042402304%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.insider.com%2Fcelebrities-protests-black-lives-matter-ariana-grande-halsey-2020-6>.

Ho, S 2020, ‘A social media blackout enthralled Instagram. But did it do anything?’, NBC News, 13 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/social-media/social-media-blackout-enthralled-instagram-did-it-do-anything-n1230181>.

Kansara, R 2020, ‘Black Lives Matter: Can viral videos stop police brutality?’, BBC, 6 July, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-53239123>.

Kirby, J 2020, ‘Black Lives Matter has become a global rallying cry against racism and police brutality’, Vox, 12 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium>.

Luo, Y & Harrison, TM 2019, ‘How citizen journalists impact the agendas of traditional media and the government policymaking process in China’, Global Media and China, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 72-93, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2059436419835771>.

Maqbool, A 2020, ‘Black Lives Matter: From social media post to global movement’, BCC News, 10 July, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53273381>.

Millhiser, I 2020, ‘The 3 former officers who aided Derek Chauvin are charged in George Floyd’s killing’, Vox, 3 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.vox.com/2020/6/3/21279481/george-floyd-second-degree-murder-derek-chauvin-thao-kueng-lane>.

MSNBC 2021, Pulitzers honor Darnella Frazier who recorded George Floyd murder, 12 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5l-Hi4ro3ds>.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management n.d., Legal highlight: The Civil Right Act of 1964, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.dol.gov/agencies/oasam/civil-rights-center/statutes/civil-rights-act-of-1964>.

Pettie, E, Buxton, M & Meenan, K 2020, The growth of racial justice content, in 7 charts, YouTube, 19 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/trends/articles/racial-justice-content-on-youtube-explainer/>.

Rao, S 2020, ‘Celebrities are rushing to support the Black Lives Matter movement. Some might actually make an impact’, The Washington Post, 11 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2020/06/11/celebrities-black-lives-matter-movement/>.

Tamikadmallory 2020, Gratitude for others joining protest, 7 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.instagram.com/p/CBHKLKuBP11/>.

The New York Times 2020, How George Floyd was killed in police custody visual investigation, 1 June, viewed 6 October 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vksEJR9EPQ8>.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Social media and politics? Is it relevant to each other?

Globally, 2020, on average, people scroll on social media for 145 minutes daily (Statista Research Department 2021). We see photos and videos of our friends and families and occasionally politicians-related posts as like below.

Image taken from Joebiden 2020

Image taken from Ismail Sabri Yaakob 2021

Image taken from President of Russia 2021

Maybe more of like as below with meme and video parodies.

youtube

Image taken from SarawakGags 2020

So why do politicians utilize social media? When it comes to political voting, engagement with young voters plays a significant role. In 2020, the American election broke the record with 159.7 million voters, and Biden won many young votes, 65% age 18-24, 54% age 25-29, and 51% age 30-39 (Hess 2020). Based on studies, the primary demographic of social media stood by young people, 84% aged 18-29 and 81% aged 30-49 (Auxier & Anderson 2021). Therefore, showing the importance of implementing social media in political engagement to gain young adults' votes.

Image taken from Hess 2020

According to Sahly, Shao, and Kwon (2019, p. 8), social media is a strategy tool in political campaigns. It provides direct control in building relationships with the voter without relying on third-party media such as traditional news media (Sahly, Shao & Kwon 2019, p. 8). With horizontal information flow tactics, social media provides two-way communication between the politicians and the users. Additionally, as the social media platform offers data analysis of the users' interactions, politicians can better identify and comprehend popular topics users discuss. Henceforth, the two-way communication and data analysis information allows the politicians to adequately align their response and discussion of policy proposals and immediately address political discontent (Zhuravskaya, Petrova & Enikolopov 2020, p. 417). In Barack Obama's second presidential campaign, Obama used several social media platforms to have two-way communication interactions with the users. For example, Obama conducted questions and answers sessions on Twitter and the 'Ask Me Anything' on Reddit (Contentgroup c. 2020). The implication of hashtags is a method for sparking mass political conversation too. An examplar, former President Donald Trump's campaign titled "Make America Great Again," was written by Trump often on Twitter (Earl 2016). Today, it remains to create a massive topic discussion by Twitter users using the #MakeAmericaGreatAgain (Twitter c. 2021).

However, there is a downside of politics on social media. As social media platform relies on user-generated content, the barries to entry as a user are low. Furthermore, with users' ability to reshare, report, and copy content produced by others, it's challenging for politicians to cover potentially damaging information. As social media provides sharing at unprecedented speed, misinformation or fake news may arise. Thus, negatively impacting political reputation (Zhuravskaya, Petrova & Enikolopov 2020, pp. 416-417).

Consequently, low restrictions on users' content sharing produce political memes and video parodies. The political meme is visually designed to trigger an emotional reaction to inside political jokes and shared across social media (Tenove 2019). Although political memes and video parodies act as attraction, persuasion, and bemuse strategies for votes, they also raise concerns about boundaries, privacy, and respectfulness. For instance, impersonating politicians made mislead the politicians' personalities and voters' impression.

Reference List

Auxier, B & Anderson, M 2021, ‘Social media use in 2021’, Pew Research Center, 7 April, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/>.

Contentgroup c. 2020, Social media on the campaign trail: Barack Obama and Donald Trump, Contentgroup, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://contentgroup.com.au/2017/09/social-media-campaign-trail-obama-trump/>.

Earl, J 2016, ‘Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton's most popular tweets of 2016’, CBS News, 7 November, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/donald-trump-and-hillary-clintons-most-popular-tweets-of-2016/>.

Hess, AJ 2020, ‘The 2020 election shows Gen Z’s voting power for years to come’, CNBC, 18 November, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/18/the-2020-election-shows-gen-zs-voting-power-for-years-to-come.html>.

Ismail Sabri Yaakob 2021, RM400 billion allocation in Malaysia, 28 September, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=419436586197670&set=a.419269872881008>.

Joebiden 2020, Vote for Democracy, 2 November, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.instagram.com/p/CHEo-k8iPvO/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link>.

Maestro Ziikos 2017, Donald Trump and Barack Obama singing Barbie girl by Aqua, 17 January, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLNy6T3KkEc >.

President of Russia 2021, Russia President award Olympic athlete, 11 September, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://twitter.com/KremlinRussia_E/status/1436666243205976066>.

Sahly, A, Shao, C & Kwon, KH 2019, ‘Social media for political campaigns: An examination of Trump’s and Clinton’s frame building and its effect on audience engagement’, Social Media + Society, pp. 1-13, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2056305119855141>.

SarawakGags 2020, Malaysia politicians’ cabinet meme, 23 February, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://m.facebook.com/sarawakgags/photos/a.134669094054347/597225217798730/?type=3&source=48&__tn__=EHH-R>.

Statista Research Department 2021, ‘Daily social media usage worldwide 2012-2020, 7 September, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/433871/daily-social-media-usage-worldwide/>.

Tenevo, C 2019, ‘The meme-ification of politics: Politicians & their ‘lit’ memes’, The Conversation, 5 February, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://theconversation.com/the-meme-ification-of-politics-politicians-and-their-lit-memes-110017>.

Twitter c. 2021, Make America Great Again, Twitter, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://twitter.com/search?q=%23makeamericagreatagain>.

Zhuravskaya, E, Petrova, M & Enikolopov, R 2020, ‘Political effects of the Internet and social media’, Annual Review of Economics, vol. 12, pp. 415-438, viewed 29 September 2021, <https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-economics-081919-050239>.

0 notes

Text

Week 4: Is blogging still relevant in the age of TikToks and Instagram?

In today's world of TikToks and Instagram, is blogging even relevant? Before the deliberation, let's understand the fundamentals.

Social networking services (SNS)

Xu et al. define SNS as an online service that allows users to create and share personal profiles, explore, interact with, and establish connections through personal networks within the bonded system (2014, p. 240).

Blogging

Pettigrew, Archer, and Harrigan described blogging as an informative website that displays content in reverse chronological order, with the most recent post at the top (2016, p. 1026).

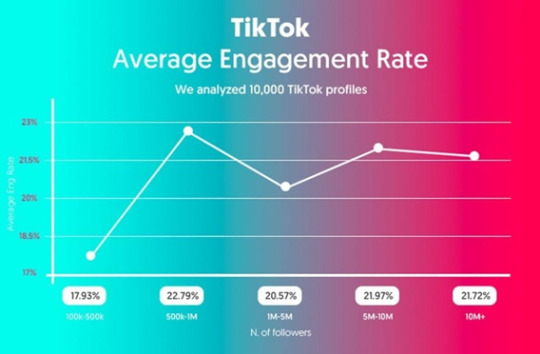

Initially architectural for plan posting, photo sharing, and check-in on the Burbn app, then deconstructing to central its commenting, "like," and photo function, based on the computational IOS structure, the renowned Instagram was launched in 2010, receiving 25,000 users on the first day (Gillespie 2010, p. 349; Blystone 2020). Ultimately computational with the Andriod operating system in 2012 and bought over by Facebook (Blystone 2020). Instagram's continuous enhancement with attractive features, enabling users to upload media with filters, viewable posts for 24 hours known as "Instagram Stories," messaging, and more, led to one billion active users monthly in June 2018 (Blystone 2020; Statista Research Department 2021). In addition, after acquiring the competitor Musical.ly and having 200 million accounts ported over, TikToks became today's rising social media platform (D'Souza 2021). Including addictive functions to create 60 seconds videos and combine music, filters, sticker, and more, TikToks withstands approximately 65.9 million active users monthly as of 2020 in the United States (D'Souza 2021; Statista Research Department 2021). Meanwhile, in the United States, Statista Research Department (2021) estimated 31.7 million bloggers in the United States.

youtube

Based on the image, it shows the slow growth of blogging (Djuraskovic 2021). Thence, what makes SNS such as Instagram and TikToks popular?

According to Lin and Lu, studies found that people are motivated to adopt SNS because of its pleasure-oriented information system and its capability to connect with peers (2011, p. 1159). Based on the Maslow hierarchy of needs, humans desire belongingness, and SNS has built prompting interaction functions (Ghatak & Singh 2019, p. 298). For instance, on the user-generated content, the other users can react using commenting, instant messaging, reaction "like," sharing, mentioning of others, and more (Voorveld et al. 2018, p. 40). The interaction results in forming virtual communities, whereby social aggregations develop from the Internet when sufficient people participate in public debates for an extended period and enough human emotion to build personal relationships in virtual worlds (Akar & Mardikyan 2018, p. 1).

Thus, when social media is so popular, how is blogging still relevant? Although there are declines in personal "diary" blogging, blogs are read by 77% of internet users. As blogging evolves and sustains more in the knowledge-providing direction, blog posts emerge whenever individuals search for answers (Dietz 2021; Edgecomb 2016). For example, famous blogging service WordPress has dodged the blogging decline as the platform commercial towards professional bloggers instead of novice bloggers (Kopytoff 2011). Moreover, as SNS providers tend to have writing limitations, such as Instagram restricting to 2,200 characters, it is unsuitable to accommodate extended writing on topics than blogs (Zote 2021). Since the blog has comments, it also promotes a public sphere where diverse individuals gather to provide ideas and opinions and public debate on the shared information (Batorski & Hrzywinska 2018, p. 358). Additionally, blogging implies a promotional tool. According to Chang (2021), 81% of United States customers rely on blogs as a means of advice and information, showing blogs' influence on purchasing decisions.

In conclusion, blogs remain relevant in the age of social media as the platforms serve different purposes and meet the distinctive needs of the users.

Reference list

Akar, E 7 Mardikyan, S 2018, ‘User roles and contribution patterns in online communities: A managerial perspective’, SAGE Open, pp. 1-19, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244018794773>.

Batorski, D, Grzywinska, I 2018, ‘Three dimensions of the public sphere on Facebook’, Information, communication & society, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 356-374, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1281329?needAccess=true>.

Blystone, D 2020, ‘The Story of Instagram: The Rise of the #1 Photo-Sharing Application’, Investopedia, 6 June, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/102615/story-instagram-rise-1-photo0sharing-app.asp>.

Chang, J 2021, Number of US Bloggers in 2021/2022 demographics, revenues, and best practices, FinancesOnline, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://financesonline.com/number-of-us-bloggers/>.

Dietz, R 2021, ‘Is blogging dead in 2021?’, Medium, 20 April, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://medium.com/@rebekahdietz/is-blogging-dead-887f35a83587>.

Djuraskovic, O 2021, ‘Blogging Statistics 2021: Ultimate list with 47 facts and stats’, First Site Guide, 26 August, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://firstsiteguide.com/blogging-stats/>.

D’Souza, D 2021, ‘What is TikTok?’, Investopedia, 22 July, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://www.investopedia.com/what-is-tiktok-4588933>.

Edgecomb, C 2016, ‘Blogging statistics: 52 reasons your company blog is worth the time & effort’, Impact, 2 December, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://www.impactplus.com/blogging-statistics-55-reasons-blogging-creates-55-more-traffic>.

Ghatak, S & Singh, S 2019, ‘Examing Maslow’s hierarchy need theory in the social media adoption’, FIIB Business Review, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 292-302, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2319714519882830>.

Gillespie, T 2010, ‘The politics of ‘platforms’’, New media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 347-364, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1461444809342738>.

Kopytoff, VG 2011, ‘Blogs wane as the young drift to sites like twitter’, The New York Times, 20 February, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/21/technology/internet/21blog.html>.

Lin, K, Lu, H 2011, ‘Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 1152-1161, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563210003766?casa_token=cNw_sMthERQAAAAA:Ey0DiPzEL_8GFAx5UufCM2uMPD-RnJ9wNSA-FEakQVZyrqH6-Odm01kb2WXuHtgL0H0qxS46GNI>.

Pettigrew, S, Archer, C, Harrigan, P 2016, ‘A thematic analysis of mother’s motivations for blogging’, Maternal Child Health Journal, vol. 20, pp. 1025-1031, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10995-015-1887-7.pdf>.

Statista Research Department 2016, ‘Number of bloggers in the United States 2014-2020’, Statista, 29 February, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/187267/number-of-bloggers-in-usa/>.

Statista Research Department 2021, ‘Number of monthly active Instagram users 2013-2018’, Statista, 10 September, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/>.

Statista Research Department 2021, ‘TikTok: number of users in selected countries 2020’, Statista, 26 July, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/1202979/number-of-monthly-active-tiktok-users/>.

Xu, Y, Yang, Y, Cheng, Z & Lim, J 2014, ‘Retaining and attracting users in social networking services: An empirical investigation of cyber migration’, Journal of Strategic Information System, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 239-253, viewed 20 September 2021, <https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0963868714000195?token=59850A05BB92383D18EF618453A92BB7E8F6B070EE0FA7C11B9F04E23570CBD313FC20FA4E65A77440E33D3D87ED99EE&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20210920062516>.

Vaeth, K 2020, ‘Tapping into TikTok as a branding platform’, Infinite, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://theinfiniteagency.com/insights/social/tapping-into-tiktok-as-a-branding-platform/>.

Voorveld, HAM, Noort, GV, Muntinga, DG, Bronner, F 2018, ‘Engagement with social media and social media advertising: The differentiating role of platform type, Digital Engagement with Advertising, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 38-54, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405754?needAccess=true>.

Wall Street Journal 2020, The Rise of TikTok: From Chinese App to Global Sensation | WSJ, 15 September, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P2VO6ELhwQY>.

Zote, J 2021, ‘How long should social posts be? Try this social media character counter’, Sprout Social, 26 July, viewed 22 September 2021, <https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-character-counter/>.

1 note

·

View note