Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

She’s wadding through history as each foot implants itself on a rock older than the popularly narrated story of the world. The rocks are slippery and seagulls have made their temporary abode closer to water. Empty seashells look back at her. She notices the green moss stuck to a particularly big rock, touches it, lets go.

There’s a spot close to where the wooden bridge ends. Jagged rocks barely touch her feet as she rests her tired legs. She’s been carrying a book for a long time, a piece of a culture some stranger gifted her. There’s no one author to this bizarre set of stories and that’s okay. Reading soothes her but today she is restless and so she closes the book and retraces her steps to the beginning – to the lighthouse. A faded yellow, infantile graffiti etched onto the tower’s side, the structure has no occupants. Roughly a mile away gelato cafes and memento shops are overrun by tourists as they procure simulacra, not knowing the original sits not far off.

Much like her, the lighthouse stands out in the weirdness of its surroundings; at this junction, the old and the new don’t blend. A gentle breeze turns into a strong gust of wind, picking up an errant thought and running with it. She closes her eyes and opens them to find herself in her family’s living room.

The idiot box is on. She hums.

For 2019 she has no new wishes. She just wants to learn to live with monachopsis.

0 notes

Photo

Arising out of man’s social needs, cities are a product of the earth and of time. A city has no singular past or present rather multiple histories that tie it to our world.

0 notes

Text

So below.

Their nights always consume their days.

Every creature has a purpose in the world below, they are told. Where the world above ends and theirs begins, they do not know. The birds chirp the same way, it sounds. Wolves howling incessantly, snakes rattling, slithering, their eyes seeing things beyond the darkness. Every creature moving in a direction unknown; crawling, hopping, running.

And so every time a bird from the world above chirps, the one below responds to its call. The creatures are joined to their counterparts in an infinity loop. As above, so below. And so it goes on and on for no one can say how long. Their infinity becomes their nothingness. But this is the only existence they’ve known.

So how do you measure nothingness?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I love coffee shops. They hold a certain air of unfulfilled promise, a feeling of expectation, an anticipation of what could be. I like people watching, and listening to the hum drum conversations, of being in a place without feeling the need to share my existence with anyone. I can read, or write, listen to music, gaze in the distance, or just be there, sitting.

I love coffee: espresso for when I need a pick-me-up, mocha for when I want to self-indulge. I love the smell of coffee, the quirky artwork, the self-assured baristas in their white aprons, the indie playlists I would probably never listen to at home. There’s a facade to this place that you can accept because for all its shallowness it speaks to you.

I love coffee shops because they remind me of being on a train: there’s no static in this town, only a journey to experience.

0 notes

Text

Urban Abstract: New York

It’s a cold December morning and you’re making your way through a throng of human beings drafted especially for Times Square. There’s a sea of million faces, bodies, rapidly moving hands and legs unable to stay still. Move. Move. Keep moving. It’s a cold December morning, and your body is half freezing, half humming in anticipation. You’re walking through a city the world dreams about collectively, each dream more elaborate than the other, no face the same, neither the story. It’s a cold December morning and you’ve travelled more than 270 miles to see a tree.

Rockefeller Centre from 30 Rock. Like most things New York, your perception of the city is grounded in pop culture references patched together through years of media consumption. It’s only as you’re walking through the city - a city you’ve fantasized about more times than you’d like to count - that the reality of your surroundings hijacks your sense of wonderment. And you come to realize: this is not the New York you’ve dreamt about all along. Or is it?

During that first stroll through the city, you compare it to the version in your head. The sea of people is less noisy in your head, more like a perpetual mass of bodies that glide together without breaking apart. The sun shines a little less brightly upon gleaming skyscrapers, glass mausoleums, unforgiving in the glare they pass on to you. The streets are not dark and dank, smelling of piss and cheap perfume. Fire escapes make sense and there are portraits that are more than epitaphs of modern love.

It’s a cold December morning and this is how you’re spending the last sequential date of your life: getting lost in New York.

Exploring a city on foot is more than a case of the curious cat. For the time that your feet hit the ground you are both the tenant and the owner of the space you set out to explore. Such a strange dichotomy, navigating your way through years upon years of history permeating, encircling, the solid ground (or so you imagine) you walk on. Are there pieces of yourself you glimpse in passerbys? Waiting at the curbside, ears plugged to static, your memory a swirl of what came before. You shake your head. Move on. Your feet are too tired for your brain.

But first the tree.

The Rockefeller Centre Christmas tree sits (stands tall) in Midtown Manhattan.

There’s a good chance Holly Golightly just walked past you, perhaps as Blair and Serena traipsed into one of the Bendel’s.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my eyes and all is born again.

New York is a psychedelic trip and you don’t know how to stop yourself from tripping just yet.

Walking through the entirety of Manhattan is something you never registered fully. Upper East Side locks your entire day and there you are walking into a store, unable to tear your eyes off the magnificent displays, tired, and hungry, yet craving what only this city can give you.

Maybe you’re really good at convincing yourself.

The tree is grand, the ambience even more so. There are skaters along the rink, waiting for their turn to twirl in this sea of human foam, as you watch from above, distant - but you want to be there at the centre of it all - this human commotion of celebratory unity in form.

Google Maps is the ally you never knew you needed. Manhattan sprawls and stretches as it lives and breathes but you only have two legs. You are greedy.

You want Manhattan but you also want Brooklyn.

The Brooklyn Bridge is a conundrum all enveloping, and then it explodes. The nervous energy was always there, and before you are able to put two and two together, the lights get brighter, sirens louder, and the air thickens with the promise of a war brimming on the precipice of what’s considered done and dusted. There’s a dirty restroom you end up using, as police swarm a local coffee shop. There are murmurs of riots. Of arrests and night time patrols. Of finding safe spaces. And yet, the bridge is where you end up at. It’s all steel and quiet agitation.

There’s a darkness underneath. Dark City, inspiring countless versions, all folding into itself. Regenerative City, with its promises of exotic cuisines and cheap halal carts. The night has fully descended and now your feet have led you to Chinatown. Have some boba tea why don’t you? You politely decline. The dumplings are delicious. There’s a fridge magnet that catches your eye. The Big Apple. You pay five bucks. The cold edges feel nice in your hand. There is an empty seat waiting for you on the midnight bus. You hold on to the promise the city offers.

All this and still you loathe New York.

--

Eight months later, you’re back at Times Square for the Gopi-Contagion.

But first retrace your steps.

At least four different modes of transportation were involved in getting you to New York this time. It’s a crisp October morning and getting lost in New York is turning out to be an art form after all. Locate a diner and order some baguettes. Sugar should help.

By the time you step outside the streets are filling up. There’s a hesitant aura of expectancy associated with this visit, and the next couple of hours are a blur of culture soaking: independent bookstores and the Guggenheim. Everything comes back a circle. You smile.

Art is not just for the inside of buildings. Your legs are weary but the prospect of Central Park is too tempting. You stumble upon conversations about Halloween costumes, old escapades and the sheer impoverishment that comes with being a resident of this city. It’s a litany by now: no money, no prospects, no escape. It goes up a volume, and then dies down too. You sigh and sip on your Machiatto. The sun is out. This city is on to you.

Journeying around the city gets easier with every new destination you map out. Imagine Chelsea market as a person, with all its nooks and crevices, bright lights and lavish Halloween decorations. The newly rich relative, putting his best face forward. Ply all the raw edges together, make everything new again. Between this and the facade Times Square puts on, you wonder who lost.

It’s 10:30 pm and you’re back at Times Square, searching for a piece of Pakistan. Your stomach grumbles and you reluctantly head to a nearby halal cart, but your eyes are glued on the bright screens, waiting, willing. It doesn’t end as you hoped it would. DC calls you sooner than you had imagined it would. There is no great revelation, no thunderous applause. Only a run for the bus as you leave the installation behind.

You came for Gopi-Contagion. You leave hating New York a little less.

--

The city calls you back. It’s been less than a month.

By now you’re used to red eye buses. The seats are crampy by the second hour, but that’s already half the trip so you don’t make a big deal about it. The city feels less alien this time around, as you sprint across Hell’s Kitchen for Midtown West. There’s only one other person in line and the doors haven’t opened yet. A coffee place nearby. Good. You make a quick coffee run, befriend a stranger’s dog and make your way back to the convention venue.

You’re here to meet Margaret Atwood on a whim. And no entrance pass (as yet).

An hour of waiting and suppressing yawns later, you make it to Book Riot Live.

Three hours later you meet Atwood, an encounter as surreal as you first thought it would be. She’s tired but gracious. You’re tired and clumsy. You recount all your favourite passages from Oryx and Crake and go quiet, because what else do you say to the person who has written some of your favourite books? Some inconsequential chatter later, you end up in a heap on one of the many bean bags spread across the venue. You haven’t had any sleep for the past 28 hours and it’s starting to show, in the small, understanding smiles of fellow attendees, and your habit of splurging on books doubled. You smile back and make another coffee run. Sleep can wait till you get back home.

--

In the course of two years you’ve changed travel buddies with every subsequent trip. The only constant is New York.

You’ve tried exploring New York like a native and a tourist. With every visit, the streets feel welcoming, while the subway is your ultimate nemesis. And what about ‘the places to see’? You’ve enjoyed the usual suspects such as The MET and the MOMA but also the ones tucked further away; The Cloisters. Here the city feels different. You’re walking through ruins of bygone eras, sometimes finding yourself in a chapel, sometimes a monastery.

Does this city want your soul? Why should it? It possesses the souls of so many others. The world stares at New York, foaming at its mouth, watching, whispering, the greatest whodunit of modern time. What the museums cannot hold, end up in the gutters, the underground network of a fool’s paradise. Perhaps, every living being to come in contact with the city is treated to a different fracture. How many other skeletons are you hiding? Does the city answer back? If it does, the abyss bellows.

There’s a time you ended up having dinner under the shadow of the Empire State Building. A standard pizza slice and some lemonade to wash it down with. Are you a New Yorker then? In essence, playing at being a native of a city that won’t hesitate to chew and spit you out? Will it see the many schisms and cover them, or will you be exposed for others to turn a blind eye to?

You’re thinking of this and so much more. Your head a mess, your legs faster than they’ve ever walked before.

“Run me over, why don’t you!?” someone shouts as you brush past the same throng of human bodies.

You ignore that voice and keep moving. Always moving.

You have a lot to catch up to.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It hits you at odd times.

You're sitting with a group, listening to people talk, nodding, smiling at their funny and not so funny jokes when suddenly it washes over you and you're left just a tiny fragment of the current conversation. Instead you end up straddling two different worlds, time zones, continents - lifetimes apart.

Or so it seems.

You miss a place in small ways. At inopportune and awkward moments.

You miss it by its smell. The smell of autumn serves not so much a romanticized olfactory function but a realization of evening winds being a little more chilly than usual as you walk back home, when pumpkin spice lattes will be something you’d naturally crave, when the arrival of Halloween would excite you.

You miss it by its feel. Leaves crunching under your feet as you walk along well-trodden paths, detours along water, your feet guiding you on lazy days with a mind of their own. Old brick buildings that are your home away from home. Freshly pruned grass, concrete, cobbled streets underneath your feet as you walk, jog, run. Sometimes static, sometimes moving, a black rose you once saw on the sidewalk.

It never washes over you all at once. Not in a big way at least. The feeling that you don't belong in what you've always called home. The city you grew up loving and living in. The city that has nurtured you over the years with its eccentricities, with patience and a certain amount of love.

You don't know what to tell the city you used to call home. The people you can still talk to. It's easier with them, they can't pick at your newfound hollowness, this miasmic void you try so hard to swallow that some days convinces you of the wrongness of it all.

The people you can still talk to.

It's the city you feel can look in to you much more clearly and you're afraid of what it can see with its wise eyes.

Places you've come to hold dear, you hold on to still more tightly than you ought to. Friends and family that are a spider web of emotions and experiences of what seems like your life, only not yours anymore.

Dislocation.

It's such an odd word, dislocation.

As if you’ve forgotten your place. As if you moved to something new of your own accord. As if events were under your control.

Dislocation.

As if you just changed spots during a game of musical chairs.

Dislocation.

As if you walked five miles to get to a place that was just a mile away.

Disorientation, perhaps?

You've lost, but you've gained too. You tell yourself.

There's a certain violence to this process you've come to realize. Like having your umbilical cord cut too soon.

Like jumping in front of an oncoming train in jest and getting your foot stuck between tracks.

Like drowning but not waving, because you still think the water is your friend.

You let these little things creep inside of you and here you are trying to hold yourself together, a patchwork of people and past lives, trying to hold on to the skin you’re shedding.

There are twenty-one places you can sit by but there’s only one you choose to, every time.

It’s by the koi pond, a small Greco-Roman statue hanging in the background, trying to mind its own business but its vacant stare offends you.

Why do you get to stay stagnant and still, here, at the place I love, when I must wander on to new places?

Utraque Unum.

The statue only stares back.

0 notes

Text

Aerial Vegas

People usually go to Vegas for one of three things: gambling, getting so drunk you pass out, or both.

My friend and I? We went to Vegas for a hot air balloon ride. This post is about this rather once-in-a-lifetime experience and our almost-failure to ride a balloon.

Upon reserving our spot on the flight, we were instructed by the balloon company to check in with their team the night before the big adventure to ensure Vegas winds were willing to let us make this journey. Early reports were not too hopeful with predictions of the winds being 10 knots or higher. For those wondering, winds above 10 knots (or 11.5 MPH) is automatic disqualification for a balloon flight. Considering our primary reason for being in Vegas was to take the balloon flight, you can well imagine how bummed we were. Couple that with binge-watching reality tv and you have two snappy, grumpy grads stuck in Vegas heat refusing to leave the hotel room except to answer the protestations of our grumbling stomachs (mostly with frozen yogurt).

So armed with this rather discouraging news, we went to sleep. Fast forward to 4 am in the morning when I wake up to check on our flight status and what do you know, we’re good to go! Vegas winds had decided to behave themselves (we’d witnessed a desert storm just a day before) and we were on schedule to seeing Vegas from up above at sunrise.

We reached our designated meeting spot from where our group of nine was driven to the middle of nowhere (with a hospital nearby) where I witnessed my first desert sunrise which was quite spectacular and totally worth skipping normal human hours of sleep for.

While our group of enthusiasts (comprising of one pilot-in-training) waved our cameras around trying to snap the best possible pictures, the Vegas Balloon Rides team started putting together our mode of transportation. Yep. You read that right. Have you ever seen your ride being assembled right in front of your eyes? We have. From putting final touches to the basket to unloading the monstrous balloon from the van and blowing it up with hot air we witnessed every exciting (and laborious) element that went in to making our flight possible.

With our ride prepared, we hopped on to the basket after being given safety instructions for safe landing. Our pilot, who has been flying balloons for the past twelve years, wanted us to know he had a spotless record with zero incidents and that he wanted it to remain so. That meant refraining from climbing onto the basket edges and attempting Cirque du Soleil style tricks and trying to get close to the flame among other things (other things which included dropping recording devices and phones from 2000 ft above ground). Naturally, we all agreed.

What follows next is my camera’s monochrome love affair with the Vegas landscape.

As we rose up in the air and the houses and cars turned to mere specks the one realization that hit me hard was how peaceful it was up above. Eyes closed all I could feel was the gentle breeze with a calm sense of peace and quiet enveloping this curious company of strangers. More than a week of travel and adventure behind me, this unexpected halcyon silo was rather welcome (until our pilot started talking again and we were back to the business of human life).

Our hour ride was cut short by the wind acting up again (oh wind) so we decided (or rather our pilot did, we just nodded along) that everyone was definitely interested in trying out this experience again, for which we first needed to touch ground safely. We landed in the middle of nowhere (this time with no hospital nearby) outwardly in high spirits, while inside our mind was already sorrowful at returning to the ‘real’ world. As my friend quipped upon touchdown, “we really had our head in the clouds!”

So while people equate Vegas with modern day debauchery for me the experience turned out to be something I will remember for a long time to come, for all the right reasons. I know most of us contemplate our existence up in the air these days (with the problems that come with bumpy airplane rides) but existential crises on a hot air balloon are something else entirely.

All said and done, I’m glad I got to see this side of Vegas. Here’s to wandering on unknown paths and coming out a slightly recalibrated version of your former self.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Elsewhere is a Negative Mirror

Marco enters a city; he sees someone in a square living a life of an instant that could be his; he could now be in that man’s place, if he had stopped in time, long ago; or if, long ago, at a crossroads, instead of taking one road he had taken the opposite one, and after long wandering he had come to be in the place of that man in that square. By now from that real or hypothetical past of his, he is excluded; he cannot stop; he must go on to another city, where another of his pasts awaits him, or something perhaps that had been a possible future of his and is now someone else’s present. Futures not achieved are only branches of the past: dead branches.

“Journeys to relive your past?” was the Khan’s question at this point, a question which could also have been formulated: “Journeys to recover your future?”

And Marco’s answer was: Elsewhere is a negative mirror. The traveler recognizes the little that is his, discovering the much he has not had and will never have.”

Reading Zeki’s thesis on how our brains function and what that means for creativity reminded me of one of my favourite books: Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. I felt the echo of Zeki’s thoughts in Calvino’s words; where every city that Marco Polo visits is more of an imagination of his mind’s eye, and where each city is supplanted by the past and future simultaneously.

My takeaway from Zeki’s thesis is that what our mind imagines can hardly be achieved in the reality of our existence. In that respect, the book tends to tilt more towards the philosophical side of our brain’s functions, and even though Zeki takes care to back his thesis with scientific reasoning, I feel at its heart Splendors and Miseries of the Brain is itself a highly innovative reimagining of what our brain is supposed to epitomise: the pinnacle of creativity. Zeki writes, “Abstraction is the critical characteristic that is common to both inherited and acquired concepts.” Abstraction finds its place in not only art but also love. We cast the idea of love in an image acquired from the neurobiological processing of our mind, yet at its most basic we can never understand it. I believe, love, as a concept, a philosophy, a wandering of the mind can only be understood the way Polo imagines his cities to be; wispy and unattainable, yet more attractive than any worldly concept.

I am particularly fascinated by Kantian philosophy about how the acquisition of knowledge is not just possible through an understanding of the physical but also the ‘contribution of the mind’. This comprehension might well be incomplete, but who says incomplete knowledge is a flaw? In my experience of writing and making sense of the world, I have found creative potential to be interspersed within this fragmentation of knowledge. Many times as human beings, we make the mistake of trying to achieve perfection in knowledge. I think that with a universe as old as ours it’s an oversight to disregard the forgotten bookmarks of our time and space; sometimes within forgetfulness we might attain, that which belongs to the noumenal world.

Sometimes thinking in abstraction I wonder if we unduly hold order to a higher stature than chaos. For me, without chaos, order itself is an alien conception: our knowledge of one draws its metaphors and roots from the reality of the other. It is this borrowed existence of each other that I believe leads to misery - because in the deepest corner you know this incomplete existence is pivotal in helping you navigate your way around the world.

I for one am in accordance with the brain’s capacity for misery and it being advantageous from a creative standpoint. There’s something poignant in our brain being a stand-alone chamber of thoughts and confluences that it is unable to share with anyone apart from the physical manifestation in terms of art and creative works. How solitary our brain must be - to sit on its throne of conspicuous loneliness; of billions of nerve endings and neural processes; a cavity inside the human body that knows itself a little too well.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Creativity, Culture and Two Different Histories

Q: If it takes a village to raise a child, what does it take to raise a creative soul?

A: A village, some turmoil and displacement

Displacement

| noun |

: the act or process of displacing : the state of being displaced

Our world today is in a constant phase of displacement: both bodily and mental displacement. While our villages are still as important for the maturation of a child, they are no longer just silos, rather networked silos. Our villages have achieved a fluidity past civilizations could only dream of, we are now on-air 24/7. In our world, I don’t have to just stick to my village now, I can travel to yours and yours and even yours. Essentially, I can pick and choose the village I want to be a part of.

Or can I?

It seems like our current world is proliferated with the illusion of choice, while Weimar Germany wasn’t afforded even that. But before talking about the modern world, I would like to talk about the Islamic Golden Age and how the creativity and innovation that flourished during the Middle Ages was different to how Weimar Germany handled creativity.

The Muslim world experienced great prosperousness in art, science, medicine and economy in the Middle Ages. From translating Greco-Roman texts to Arabic, to strides in astronomy, medicinal sciences, technology, physics and architecture the Golden Age was an epitome of creativity and lasted for half a millennium. In fact the advancements made under Muslim rule in the middle ages are of such importance that in his book The Spirit of Creativity: Basic Mechanisms of Creative Achievements, Gottlieb Guntern writes:

Muslim culture engendered an entire chain of glories for the Christian West. The Italian Renaissance, in its turn, inspired and triggered the emergence of the European Renaissance. That Renaissance was followed by Luther’s Zwingli’s and Calvin’s Reformations, and Protestant work ethic that played such a crucial role in the industrial revolution and the free spirit giving birth to the Age of Enlightenment. To a certain extent, all of these events owed their origin to the Islamic cultural heritage, although the West denied the contribution of the Muslim civilization. It conveniently overlooked the fact that the Muslim era had saved the essence of Greco-Roman culture from oblivion and physical destruction; without its rescue mission, that glorious ancestry might have never been known to the post-medieval Europe.

Unlike the Weimar Republic, the Muslim world did not undergo a stream of violence in order to turn out great thinkers and artists. Creative geniuses worked alongside the state to exhibit their work and in fact found the state to be their biggest benefactors. It was only when the Muslim world was faced with the threat of the Crusades that there was a visible decline in creative output as the infrastructure that had been in place for hundreds of years, began to crumble.

Two different states, in two different times, and both fostered creative projects under completely different conditions.

What I’d like to draw from this example is our reliance on our past and the need to formulate our understanding of the world in a more holistic manner. If we are to take in to account the current creative state of the world, we need to think outside the limits of Western conceptions of creativity. In a world that is increasingly networked, it is important to realize the contributions of various civilizations and cultures and to learn from them collectively. I strongly champion this cause, primarily because my biggest fear is that refusing to acknowledge other cultures and celebrating their differences is one of the reasons why we’re faced with an increasing polarization of worldviews with no middle ground in sight.

In a constant battle between the Spartacists and Freikorps of the world, there are no winners, only bedraggled survivors.

0 notes

Text

Books and New Media

Growing up in the past two decades or so every bibliophile would have come across and engaged heatedly in a debate on the threat to books by ‘new media’. I believe it says a lot about us as a society and culture when we turn a blind eye to the fact that the written word has adapted itself very well to whatever new technologies have sprung up over time. In this regard the debate needs to be centered more on what we mean when we say ‘books’ rather than what we consider the future of publishing and books to be.

From papyrus rolls to bound parchments, from hardbacks to glossy magazines and finally the tablet, the written word has found ever new forms and mediums to be displayed in. In her article Murphy talks about how the relationship between publishing and new media has been viewed as a zero-sum paradigm, pitting both against each other, when in research shows, new media complements books. How these various mediums converge in a social, economic and cultural context, and what that means for the so-called ‘old media’, however, is a different debate.

One of my favourite TED Talks tackles book digitization, much like the Samuelson article discusses. The digitization of books on its own is a giant task, especially if these books are being made available to the public for free. Moreover, this shift in medium - from analog (physical form) to digital - allows for data to be studied and interpreted in ways that would not have been possible previously. Harvard researchers Aiden and Michel, look at what books can teach us about the eras they were written in and how they give us so many more clues about our social existence than what we could imagine. What this means is that abstract terms and concepts can now be represented in numbers and diagrams for others to study. Aiden and Michel consider their work to be culturomics: the application of massive scale data collection analysis to the study of human culture. From influenza epidemics, to charting the success and decline of a particular artist; each of inferences can only be drawn from studying large scale data, made possible by digitizing records and books.

I think equating new media and books is a wrong analogy since both can’t be compared in relation to each other; they both serve different purposes, for different people. What new media can do is to add to the knowledge base we already have through books and make it available to a greater number of people.

0 notes

Text

Changing Metaphors: Why Tech Metaphors Matter

I have a rather contentious relationship with passwords. I know they are important for security purposes, yet making an effort to remember them in all their confusing glory has led to one too many incidents with one ending: face meet palm.

So when I read that there was possibly a new way around passwords I was reasonably excited. Fast IDentity Online (FIDO) is a consortium of some of the most innovative companies in the world who are working to make identification and authentication simpler, yet stronger.

How does it work, you may ask. The consortium has developed separate devices which come pre-installed with security specifications that require the user to just use their username and a simple PIN. The Forbes article compares this technological device to a ‘digital key’, whereas the Telegraph article likens it to a ‘USB keyring’.

Even though the Forbes article is older than the Telegraph one and talks about the development of this technology before it was unveiled late last year, it is clearer in its use of description and metaphor, which subsequently makes it easier to understand how said technology would work. And why is it important that the metaphors used in this case are clear? To ensure that this new technology reaches out to its intended user base (supposing it is general users and not large conglomerates being targeted). Much like Lakoff’s argument that “any human understanding of abstractions, whether computational or in other domains, will be based on embodied metaphorical images”, I believe, for a new technology to gain traction it is important that the metaphors and analogies associated with it are visually crisp and sound from the get go.

But metaphors might also change as technologies change, and we need to accept that. The Forbes article discusses this new technology from Google’s perspective, whereby the device is the key and our Google account is the ‘lock’. The use of this metaphor allows one to understand that these devices will only work with one particular account. Whereas, the Telegraph article makes use of a more hip metaphor by calling the device a usb keyring.

I find the use of these two different metaphors interesting in terms of their visual imagery. Before the launch of these devices, they were portrayed to the public in terms of an older technology - something as simple as a lock and key. The release of these devices along with the launch of its open protocol for simple login practices, has perhaps urged technologists to view them in more current terms.

0 notes

Text

It Takes an Entire Nation to Send One Man to the Moon

Walking through the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, what struck me the most was how often technology and policy have intersected through time and space (pun intended). Technology has never existed in a vacuum – it has always been accompanied by some policy and legislation to either use or abuse it. President Kennedy’s address before a joint session of Congress in 1961 (played on a loop next to the Space Race exhibit) is a testament of this symbiotic relationship. In his address, President Kennedy urges the American people to take a stand and prepare for a “new American enterprise”, in the form of space exploration.

In many ways, this address puts things in to perspective for present-day readers of history because it goes to show that the race to the moon was not just to test technological mettle but in large parts, a new avenue for competition between the then USSR and USA. The only other technological rat race in recent times that comes to my mind is between Pakistan and India when acquiring nuclear capabilities. What matters in this comparison is the relationship between both players and the scale of the technologies. At the time that frantic strides were being made by the USA to scale the pace of their attempts to send a manned spacecraft in space the overwhelming fear was that USSR might use its manned spacecraft to spy from space.

Perhaps President Kennedy’s address only made the USSR more determined in its attempts to send a manned spacecraft before the USA because in the years that preceded the USSR was able to accomplish a number of firsts through its Vostok spacecraft mission.

I can well imagine the way media, public addresses and campaigns would have asked for public support to ensure that the first person on moon be an American astronaut. After initial setbacks, the USA was able to accomplish just that by landing Neil Armstrong on the moon. His landing then was not just a technological feat but also policy and PR done right.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Playing Alien: Colonial Tropes in District 9

Contrary to Neil Blompkamp’s claims, audiences chose to see District 9 as an allegory of apartheid in South Africa. And who can blame them? Set in a country which operated under a system of racial segregation for more than three decades, District 9 is guilty of using colonial tropes in its discussion of race and the fear of the ‘other’.

On the outset, District 9 can be studied as a struggle to remain human. A mockumentary format provides glimpses in to the human population’s mindset: the aliens are unwelcome. Set against this backdrop, the MNU’s decision to evict the aliens appears reasonable at first. However, as the film progresses, the alien’s denigration is an unwelcome reminder of the human propensity for cruelty, subjugation and injustice. Ironically, all the finer human attributes such as courage, love and empathy are depicted through the characters of Christopher Johnson and his son. Christopher is fiercely protective of his son, as evidenced in his stand against the MNU workers. He empathizes with Wikus’ dilemma and promises to return with a cure for him.

In losing his humanity, Wikus is at his most humane. Prior to being sprayed with the black liquid, he is an unlikable character at best. His obsession with his self-image, derogatory remarks about the aliens, and most importantly his act of aborting the alien breeding facility set him as a villain of sorts. It is only in his transformation from human to alien, that he gains the audience’s understanding and sympathy. The white man’s guilt at being part of the system that suppressed and legitimized horrid acts against the ‘alien’ population is transmuted in his bodily transformation, whereby the oppressor becomes the oppressed.

Seen from this perspective, District 9 sends a powerful message against apartheid. However, for a movie that aims to criticize racism and segregation District 9 problematizes issues of race by typecasting Nigerians and perpetuating stereotypes. While the white-dominated MNU’s unspeakable treatment of the aliens finds a counter-narrative in Wikus’ decision to stand against the MNU mercenaries in order to buy some time for Christopher, the Nigerians are afforded no foil. They have no redeeming qualities: they plunder and pillage, scam and cannibalize under their leader. Colonial stereotypes of unruly gangs of violent, drug dealing, voodoo practicing Native African and black men are apparent in the depiction of the Nigerians.

Cultural and racial typecasting in sci-fi is especially dangerous because of the power of the metaphor in an unfamiliar landscape. These issues are critical to understand if we recognize the importance of how visual cues and one-sided narratives play a part in framing public memory, leading to a greatly polarized world.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Killer Robots

Unmanned aircrafts. Autonomous weapon systems. Human-out-of-the-loop weapons. Killer robots. Different terminologies for the same phenomena: whereby human involvement in the decision to attack a target is either not present at all, or if it is present, is of not much consequence.

In this post I look at the Department of Defense’s directive on autonomy in weapon systems and compare some of the terminology it uses with the UK Ministry of Defence’s Joint Doctrine Note.

The DoD Directive [1] was the first policy document by any country to take in to consideration fully autonomous weapons that had not yet been developed. What this means is that the Directive not only applies to current technologies but also future technologies which might give rise to the question of unmanned operation of robotic technology. Considered from this perspective, the Directive appears to be a positive step towards ensuring human control over individual attacks. However, the Directive limits its own edict by including the following waiver:

Autonomous or semi-autonomous weapon systems intended to be used in a manner that falls outside the policies in subparagraphs 4.c.(1) through 4.c.(3) must be approved by the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (USD(P)); the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD(AT&L)); and the CJCS before formal development..

This waiver allows for the usage of fully autonomous weapon systems under certain circumstances, as determined by the military, and hence, sidesteps the question of blanket ban on the use of killer robots.

Much like the DoD directive, MoD’s Joint Directive [2] is also riddled with ambiguous terminology. Moreover, while the DoD brings the question of future killer robots (5-10 years) in the mix, MoD is mostly concerned with current weapon systems. MoD categorically states its disinterest in building fully autonomous weapon systems, however, the language used in its Directive is abstruse:

“… a mission may require an unmanned aircraft to carry out surveillance or monitoring of a given area, looking for a particular target type, before reporting contacts to a supervisor when found. A human-authorised subsequent attack would be no different to that by a manned aircraft and would be fully compliant with [international humanitarian law], provided the human believed that, based on the information available, the attack met [international humanitarian law] requirements and extant [rules of engagement]. From this position, it would be only a small technical step to enable an unmanned aircraft to fire a weapon based solely on its own sensors, or shared information, and without recourse to higher, human authority. Provided it could be shown that the controlling system appropriately assessed the [international humanitarian law] principles (military necessity; humanity; distinction and proportionality) and that [rules of engagement] were satisfied, this would be entirely legal.”

Given this context, it appears the MoD is uncertain about its stance on fully autonomous weapons and would like to keep its options open were there to be a headway in the development of such weapons. What the MoD Joint Directive seems to be struggling with the most, however, is the legality of unmanned weapon systems – a situation it believes might be resolved in “less than 15 years”.

The issue that both policy documents gloss over is that of human agency and accountability in times of war. With traditional weapon systems it is easier to hold a certain person responsible for unwarranted use of force or choosing the wrong targets. However, that accountability is minus from the equation in relation to killer robots.

As such both DoD and MoD are unsure about their stance on killer robots, primarily because they are unsure of how technological advancement would affect weapon systems in the foreseeable future. It is mostly for this reason that organizations around the world are asking for nation states to clarify their stance on killer robots before any such scenario should arise.

Perhaps this is why the debate around killer robots can be said to resemble that which centers on disruptive technologies. There is a definite potential for killer robots to take over conventional weapon systems in the coming years as technological advancements increase in the weapons industry. In the DoD directive especially, the provisions provided for testing of new weapons and the waiver provision alert us to the fact that the DoD believes in taking precautions when approaching this new area of weapons manufacturing. Disruptive technologies can also be accessed by a section of the consumer population, which they had not been originally intended for[3] - I believe the technology behind drone manufacturing will allow more people access to drones – again, how they choose to use industrial drones, and should war drones get in the wrong hands, are serious questions that need to be asked.

How does one talk about technology that does not as yet exist? The way we frame debates and policy questions on killer robots must stem from considerations under which the current weapons program is already being managed. If the core values and end goals of weapon usage policy are delineated, it becomes more productive for nation states to meaningfully contribute to this discussion on the use of killer robots. Some of these considerations include: assessing the variability of autonomy, outlining the role of ‘drivers’ and perhaps most importantly, shifting the focus of the discussion from a ‘technological and innovation-centric frame’[4] to one that takes in to account the long-term consequences and impacts of the use of killer robots.

[1] Department of Defense Directive Number 3000.9: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/300009p.pdf

[2] Ministry of Defence Joint Doctrine Note 2/11: The UK Approach to Unmanned Aircraft Systems: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/33711/20110505JDN_211_UAS_v2U.pdf

[3] Clayton Christensen: http://www.claytonchristensen.com/key-concepts/

[4] UNIDIR’s report on Framing Discussions on the Weaponization of Increasingly Autonomous Technologies: http://www.unidir.org/files/publications/pdfs/framing-discussions-on-the-weaponization-of-increasingly-autonomous-technologies-en-606.pdf

0 notes

Text

The revolution of slogans? How media coverage can make or break your revolution(s)

Welcome to public displays of disgruntlement.

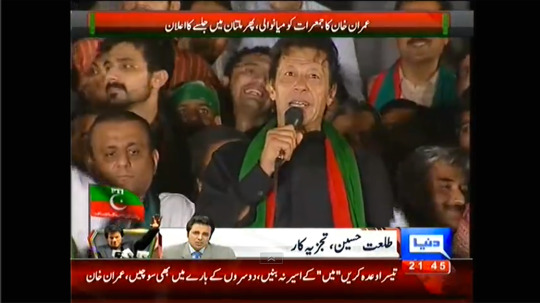

Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaaf (PTI), one of Pakistan’s most vocal political parties, has been staging large-scale demonstrations and sit-ins against the current government for the past 50 days. On Sunday, September 28 it organized arguably the biggest demonstration in Lahore, Pakistan, an historic gathering that was live telecasted on all major national channels as well as livestreamed for international audiences.

Termed all across media as Azadi March (Freedom March), the demonstration at Lahore’s historic monument Minar-e-Pakistan, was seen as a defining moment in PTI’s rise to power. While the demonstration itself and the rhetoric espoused from the main pulpit is an interesting study in its own right, I will be focusing on the media coverage of the event and analyze audience’s reception of this coverage. For my project I will look at not only the demonstration’s coverage on mainstream media but also how the audience on social networking sites received that coverage.

PTI’s chairman Imran Khan has enjoyed celebrity status long before he joined Pakistani politics. Prior to his rise as a politician, Khan led the Pakistani cricket team to its first and only cricket world cup victory in 1992. This win further solidified Khan’s status as Pakistan’s sweetheart and won him a large following. Upon his retirement from cricket, Khan turned to philanthropy by helping establish the largest cancer research hospital in Pakistan. An Oxford graduate, Khan delved in to politics with the formation of Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaaf in 1996 and was elected to the National Assembly twice between the years 2002-2013.

I provide this brief sketch of the kaptaan – ‘captain’ as Khan is referred to in mainstream media – to show how Khan’s personality is arguably the strongest driving force behind his politics and in many ways the reason why he enjoys strong support.

As a viewer of the live stream of the Lahore jalsa (demonstration), I was naturally curious how those present on ground felt being there in person. While watching the live stream, I browsed through my Facebook newsfeed and posted a status asking for first hand accounts. The screenshot below from my Facebook account succinctly encapsulates the difference between attending a live event in person versus hearing about it through the media.

The event was aimed at gathering a large crowd of people to not only show PTI’s power but also public dissent against the current government. Iqbal Park, which houses Minar-e-Pakistan, is a sprawling 45 acres and can accommodate around 2.5 million people. Local news channels started covering the event early morning as that is when people started arriving. The event commenced at 3 pm, whereas Imran Khan delivered his address around 8 pm.

Pre-event coverage focused on the number of people who would be attending the event. Most networks estimated the number to exceed 2 million excepting two large news networks: the state-owned PTV and private channel Geo News, whose estimates ranged between 25000 to 50000 people. According to one news channel:

How many people were there today? Question’s the same but answers are many. One thing’s for sure though, when the tsunami came it was in the form of a sea of human heads. Estimates for today’s gathering according to various sources include: PTI: 2.5 million Independent sources: 1.5 million Government: 50 thousand

When talking to people who were on ground, a few complained that correct numbers had not been mentioned by most news channels as there were around 3 million people who had attended the jalsa. Those who were unable to enter the park chose to gather on the streets as a show of solidarity instead of going back home. Many demonstrators parked their cars more than ten miles away from the venue and walked all the way to it.

This leads to the possible question of technological bias (Lang). Most networks chose to focus their on-ground cameras on the demonstrators in the front rows. Only one network made use of drone cameras to record aerial view of the gathering.

This coverage quickly spread throughout social media as PTI supporters who had been unable to attend the demonstration shared these images on their social media pages to indicate the triumph of their political party. In this regard, I find this symbiotic relationship between mainstream media and new media very interesting for our times as many networks are experimenting and learning with how what they broadcast affects their viewers and their credibility online.

In an effort to build their credibility and ‘proximity’ to the news, all major networks covered the event by sending their correspondents and cameramen to the venue (Zelizer). Crew vehicles were parked adjacent to the main stage, allowing correspondents a view in close proximity of the main stage as well as a panoramic view of the gathering.

Most networks chose to cover the event by inviting live commentators on their shows as the event proceedings took place. PTV News, which is a state-owned channel, did not mention the demonstration in any of its news bulletins. Government spokesmen however were present for comment on various news channels’ political talk shows and denounced the demonstration and its goals. One politician compared Khan to a ‘street boy’ and fended off an anchor’s claims about the demonstration being a huge success by claiming that only a particular subset of the society was with Khan and the crowd at the demonstration was only around ‘forty to fifty thousand’.

Prior to Khan’s speech, the event was covered from a wide-angle lens, to show the main stage, peppered with crowd footage. Upon Khan’s arrival on stage the camera angles focused closely on his appearance and demeanor. Many anchors and political pundits later commented on Khan’s ecstatic response on seeing such a large crowd and how his ‘cheeks were infused with colour’. Like Messaris mentions in his article, the low-camera angle technique was used to paint Khan in a powerful light, and was used by the media during discussions in instances of PTI’s successful demonstration and the consequences for the government (Messaris).

Interestingly, the high-camera angle shot showing Imran Khan addressing the crowd was popular for use in English dailies, but not on mainstream television.

The shot makes Khan appear more in control, unlike Messaris’ assertion stating otherwise. One reason for that could be the shot being taken from the back instead of front-facing.

Networks also chose to comment on the proceedings on-stage. One news anchor repeatedly pointed out the agitation on stage when a PTI party member was pushed aside by Khan. Another commented on Khan’s strong language in his speech. Perusing through various news analysis, it was obvious which news anchors were pro-demonstrations and which were not. Leading opinion leaders and political pundits reiterated their previous stances with regards to Imran Khan and his demonstrations. However, one major change in their analysis – whether they were pro-Imran Khan or not – was that everyone vehemently agreed that the demonstration had been a success and that Imran Khan had been able to tap in to the young voter base. One political analyst also sarcastically remarked on the crowd statistics presented by the government as being ‘absolutely wrong’ and something that ‘anyone with eyes could see’.

A topic of great interest to audiences and media alike was the use of anthems and songs during the demonstration. While critics dismissively termed the demonstration as nothing more than a ‘concert’, certain news channels paid closer attention to the kinds of songs being played at the event. During Khan’s hour-long speech various anthems, which were specially recorded for these demonstrations, were played in between to give the crowd a break and allow it to re-energize.

Many of the major networks have an active online social media presence through their Facebook and Twitter accounts. This has allowed them to disseminate news to a wider audience than what was possible with only the television. A noticeable trend on social media has been the coverage of news in a comparatively light-hearted manner than what is expected of mainstream media. Hence, even ‘serious’ news channels sometimes would post satirical and snarky status updates on their social media pages.

While many families and individuals relied on the television for their major news regarding the demonstration, overseas Pakistanis (including myself) along with a great chunk of young people who had been unable to attend the demonstration turned to social media. With networks updating their Facebook and Twitter profiles it was easy to keep abreast of the developments at the jalsa. Those at home watched the jalsa with their families and even switched on for post-jalsa commentaries by leading political pundits (Levy).

PTI’s demonstrations and their subsequent coverage have given much fodder along the way to political satirists. It is interesting to note that most newspapers choose to post their lighter political satire on their online blogs rather than their daily newspapers. Dawn, a leading news daily published the following images by Fasi Zaka, a Rhodes scholar and political commentator.

These demonstrations have also paved way for creative young people to create short video clips on how they see the political situation in Pakistan, which I believe is a positive step in the direction of youth involvement for a better country. In essence, more people are now proactively participating in politics, whereas a few years back political activism within younger demographics, while not non-existent was relatively lower.

Watch 7 Things We Dislike About the Pakistani Media by Lolz Studio

Moreover, social media has allowed news consumers to reject the establishment’s reports regarding the demonstration in ways not possible through mainstream media.

My study goes to make an important point about audience as ‘consumers’. As identified through various examples, both the demonstrators and TV viewers were not passive consumers of the televised event. While watching the live stream, I browsed through my social media profiles and chatted with friends who were watching it in Pakistan. I also entered in to long discussions with family and friends alike regarding the consequences of the jalsa and what it meant for the future of Pakistani politics.

Through this study I have begun to question my earlier ideas of media consumption. Like Press I believe media reception is a complicated process and while we cannot completely de-black box it we can try to understand the dynamics of the consumers or audience to give us a better understanding on this subject (Lewis).

More importantly, I’ve tried to analyze how media coverage of important political events can add to our understanding of those events in a broader construct. Be it heated debate or outright negation of a political party’s stance, coverage of the PTI jalsa gave Pakistani citizens a host of issues to talk about. Many political pundits, while questioning the legitimacy of these demonstrations were not afraid to admit that the demonstrations had paved a way for Pakistani citizens to question and critique the political sphere. Whether media coverage is biased towards an event or not, that’s for us to decide, but if it gives us an insight in to how media production and consumption works, the media has succeeded in playing its role as an informer.

Zelizer, B. “Where is the author in American TV news? On the construction and presentation of proximity.” Semiotica 80.1-2 (1990): 37-48.

Lang, Kurt Lang and Gladys Engel. “The Unique Perspective of Television and Its Effect: A Pilot Study.” American Sociological Review 18.1 (1953): 3-12.

Lewis, Vincent Mosco and Kaye. “Questioning the Concept of the Audience.” Consuming Audiences? Production and Reception in Media Research. Ed. Janet Wasko Ingunn Hagen. Cresskill: Hampton Press, 2000. 35-45.

Levy, M.R. “Watching TV news as para-social interaction.” Journal of Broadcasting 23 (1979): 69-80.

Messaris, P. “Four Aspects of Visual Literacy.” Visual Literacy (1994): 1-40.

0 notes

Text

Want to sell your product? Make a reality show around it.

In 2013 Discovery Channel broadcasted the three-part reality series Driven to Extremes. The press release on the Discovery channel website described the series thus:

Prepare for the ultimate Hollywood road movie, as A-list actors, Tom Hardy, Henry Cavill and Adrien Brody, join forces with Formula 1 star Mika Salo and World Superbike champion Neil Hodgson, to take on the most extreme roads in the world in exciting new series Driven to Extremes. Each episode follows a celebrity pair as they take on some of the toughest terrain on the planet, at the harshest time of the year. From keeping the car running in temperatures of -50ᵒC on Russia’s notorious Road of Bones to navigating through the depths of the Malaysian jungle in the middle of the monsoon season, accompany these high-profile petrol heads as they push themselves and their car, to the limit.

Promoted as the ‘ultimate Hollywood road movie’, Driven to Extremes is primarily a marketing campaign for Shell’s Helix Ultra brand of automotive oil. Developed by JWT, the world’s largest advertising agency, it has been labeled as ‘the most expensive advertiser-funded programme to date in the UK.’ The series was broadcasted to 75 countries and was supported by a rigorous online marketing campaign that included a dedicated Youtube channel, Behind the Scenes footage and online games.

In my post I look at this rather innovative marketing campaign as well as study the phenomena of celebrities choosing to be a part of such reality shows. Instead of featuring ordinary people, shows such as Driven to Extremesdepend on the celebrities they choose to feature and the number of viewers they subsequently attract.

Within the world of reality television there are two distinct celebrities. One is where ordinary people achieve the status of the celebrity through a particular reality show; what Sue Collins calls TV’s “construction of a new stratum of celebrity value” (89). The other is where celebrities who have been in the public eye for some time star in their own reality shows; from The Osbournesto House of Carters and Snoop Dog’s Fatherhood, these shows rely on the real-world celebrity value of these ‘stars’ and keep them in the public eye.

Both types of programming, however, play on the idea of celebrity being a commodity. In her article Collins’ writes: “reality shows featuring ordinary, real people demonstrate that the genesis of celebrity as a top-down production of the cultural industries is being challenged by the audience’s attention to itself. (89)” In many ways this stands true for most reality television programming. In Driven to Extremes, however, we see the reverse application of this phenomenon where ordinary people have been replaced with A-list celebrities to the same end goal: the audience’s attention to itself.

Episode 1 of Driven to Extremes stars Tom Hardy of the Dark Knight fame and former Finnish Formula One driver Mika Salo. The duo, flanked by a team of experts, have to make their way to the coldest city on Earth in Siberia where the lowest temperature to be recorded is -70 C. The experts include an expedition leader, security office, adventure mechanic and chief medical officer, among others. This same team leads other Hollywood stars to the hottest place on Earth and through a dangerous tropical rain forest in Episodes 2 and 3.

Driven to Extremes plays on a peculiar mix of inclusionary and exclusionary narrative. Episode One’s opening narration reinforces the idea that this expedition will “push man and machine to the edge of what’s survivable.” Within the opening sequence there are hints of a marginalized reality: “…where so many others have failed.” Each of the Hollywood celebrities is introduced either as “action hero” or the “physical side of Hollywood roles”. In Episode Two, actor Henry Cavill says, “I do action films. That’s pretend. This is the real deal.” His words strip the celebrity of his ‘higher status’ and bring him to the level of the ordinary person by emphasizing the ‘reality’ of this situation.

However, ironically, this reality is crafted over a two-year period. The vehicles used in this show have been modified to perform to their best capability in the harshest environments, and there is an emergency helicopter always at call for this group of adventurers, should the situation demand. Every last detail of these expeditions was minutely studied and planned by the adventure group heading this expedition.

Driven to Extremes does not openly invite audiences in to its group of supremely fit white males; rather, it draws on the elements of suspense and drama as it pushes its cast into a wild terrain to make for a relatable viewing experience. Travelling to either the coldest or the hottest place on Earth is not a feat most viewers can think of accomplishing, however, the sense of adventure and danger that underlies far away expeditions is a factor that allows viewers to connect with the premise of the show and likewise respond to it. The Security Officer from the team of experts builds on this sense of urgency and drama during an interview: “Everyone needs to look out for each other… (there’s) no dead weight on this expedition.” This observation is further supported by Nabi et al. who suggest that “reasons for watching reality programming may be based not on the quality of “reality” but, rather, on other characteristics, like suspense or drama, that are associated with good storytelling.” (422)

In his article on the success behind shows like the American Chopper, Carroll states: “The custom motorcycle embodies a powerful set of symbolic resonances that integrate the outlaw lifestyle of the biker gang with the myth of the American frontier that still maintains a powerful hold on the American psyche (266).” I argue that for the UK this translates in to the fascination for customized cars (The main team behind the development of the show is based in the UK). The heavily customized car in Driven to Extremes is not just a transport vehicle, it is a lifeline for these men; “lives of the entire team depend upon this vehicle.”

All through the series emphasis is put on the need for the right oil for such dangerous expeditions and how and engine failure could be fatal for the team. Flat tires, engine failures and engine overheating are dealt with the same urgency as water shortage, hypothermia and medical emergencies. In fact, on their expedition to the Taklimakan Desert in China Henry Cavill and Neil Hodgson are required to keep their windows up in sweltering heat and turn on the car heater to avoid the engine from overheating consequently resulting in engine failure in an environment where if you remain out long enough “delirium would set in followed by certain death.” The vehicle hence becomes a physical extension of these adventurers as they travel through harsh terrains.

Driven to Extremes can be seen as part adventure documentary and part travelogue. Within each episode are informational insights in to the places each duo visits. In Episode One, Hardy competes in a wrestling match with the locals at a gymnasium, which has produced Olympic medalists. Salo and Hardy also take part in a local ceremony where they offer trinkets to the fire asking for safe passage to the mountains. Episode Two has Henry Cavill act as travel guide as he provides small informational tidbits about the places they travel through on their way to the ‘Desert of Death’. The duo meet a Chinese local during their journey who is known as ‘the living map’ since he is rumored to have never gotten lost in the desert. During their journey, Cavill personal recordings of their surroundings through a hand held camera distinctly resemble a traveler’s documentation of his journey. The show thus casts its celebrities in the light of an ordinary traveller in extraordinary situations.

The sense of urgency and drama is showcased within a natural setting and otherwise, for high sensation seeking viewers the journey can prove to be too drab and unexciting. Hence, even relatively trivial incidents such as a flat tire are dramatically portrayed in the show. Images of Hardy changing a flat tire on his own, Cavill digging through sand to get their vehicle out of soft sand, and Brody being besieged by insects are accompanied by voice overs reiterating how these stars are “not acting like superstars”, and have no “chauffeurs” around them doing their work. In this the show perpetuates the myth of equality between the viewer and the celebrities.

However, as stated earlier, Driven to Extremes is first and foremost an innovative marketing campaign. A case study on the success of Driven to Extremes marketing campaign was published online with formidable statistics which claimed how the show’s reception had not only boosted sales for Shell Helix motor oil but also carved a place for Shell Helix as the top most visible motor oil brand.

While this marketing endeavor obviously paid for Shell Helix, what did the celebrities gain from it? An online search on the impact of this docutainment-centered visibility did not spare any results for any of the featured celebrities. For former motorsport heroes it can be claimed that this proved to be yet another challenge within their field of expertise, but what of the Hollywood heroes, who self-proclaimed to be in an unfamiliar situation? It can be argued since this was an advertiser-backed program; the monetary compensation for these celebrities was relatively higher than the usual adventure themed reality programs. However, pecuniary considerations cannot be the only reflection behind such an endeavor. For these celebrities the expeditions served to be “life-changing” experiences. Bleak, inhospitable and remote, their destinations are not just another goal, as Cavill believes trips like these “can do nothing but change you.”

I posit that the success of Driven to Extremes rests on the dynamic hybridity of the genre of docutainment. Through its preoccupation with the human element of the expedition by centering the narrative on the participating celebrities and symbiotic relationship between man and vehicle the show calls on for the emotional involvement of those who are watching while sending out one clear message: your journey is dependent on the welfare of your engine. Through various short clippings inserted within the narrative of the show, the importance of the motor engine oil and how the right oil is important for any expedition these messages are subtly conveyed. By using the realm of the reality television genre, Driven to Extremes further blurs the line between a documentary, travelogue, entertainment and advertisement.

Carroll, Hamilton (2008, July) “Men’s Soaps: Automotive Television Programming and Contemporary Working-Class Masculinities.”Television & New Media, Vol. 9, No. 4: 263-283.

Collins, Sue (2008, March) “Making the most out of 15 minutes: Reality TV’s dispensable celebrity.” Television and New Media, Vol. 9, No. 2: 87-110.

Nabi, Robin L., Stitt, Carmen R., Halford, Jeff, and Finnerty, Keli (2006) “Emotional and cognitive predictors of the enjoyment of reality-based and fictional television programming: An elaboration of the uses and gratifications perspective.” Media Psychology 8 (4), 421-447.

6 notes

·

View notes