Note

Hey. So the hypothetical "were". Is that the "fuera" and "estuviera" in Spanish? I ask for better recognition of the hypothetical. 🎗️

Generally it would be fuera

estuviera "were" would be used like estar in general, primarily location and emotions... like si estuviera en casa "if I were at home" or si estuviera allí "if I were there"

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

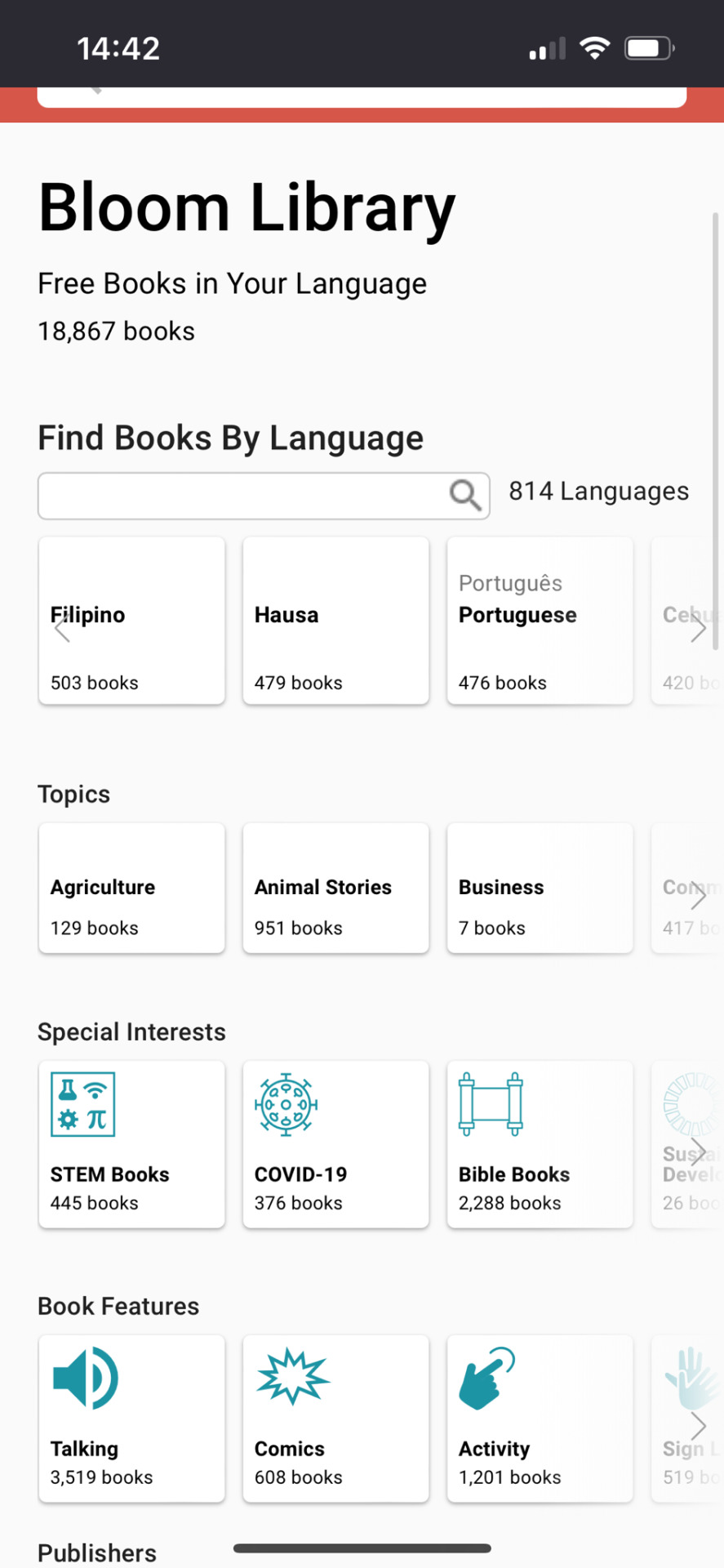

my friend and i were going to study a language together and wound up having to cancel our plans due to scheduling pressures, but! through research we came across a really cool resource for reading in a TON of languages: bloom library!

as you can see, it has a lot of books for languages that are usually a bit harder to find materials for—we were going to use it for kyrgyz, for example, which has over 1000 books, which was really hard to find textbook materials for otherwise. as you can see it also has books with audio options, which would be really useful for pronunciation checking. as far as i can tell, everything on the site is free as well.

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

Heyo 🍓:

What are the connotations between "tirar", "echar", and "lanzar" for throwing?

This is a really difficult one to answer because there's a lot of idiomatic expressions used with the verbs for "to throw" - but typically echar and tirar have the most secondary uses

This is gonna be a long one

There are actually 4 general verbs for "to throw":

tirar = to throw / to toss

lanzar = to throw / to toss

arrojar = to throw [less common but still used, generally it is physical not so much figurative like the others]

echar = to fling [very idiomatically used]

In general, tirar and lanzar tend to be more synonymous - you can easily see tirar la pelota or lanzar la pelota "to throw the ball"

And in many other applications they feel synonymous like tirar/lanzar la primera piedra "to cast the first stone"

[One of the translations you see would be like - El que (de ustedes) esté sin pecado tire/lance la primera piedra which is literally "He that (among you) is without sin, throw the first stone" or "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone" more idiomatically]

Where they're less common is that lanzar also means "to launch" so you can see el lanzamiento to be like "a launch" both in the show business industry like a show's new "launch", or launching a pilot is el lanzamiento typically... and in rocketry and space things, el lanzamiento tends to be the most commonly used one

I also tend to see lanzar used as "to cast spells" [lanzar hechizos or lanzar conjuros; sometimes used with echar], and I see it used a lot with missiles and rockets [lanzar un cohete]

I tend to think of lanzar as more weaponry based in my head, but it can just be "to throw"

Note: You also see these with tirar/lanzar los dados "to roll the dice", both make sense but it's literally "throw"; but tirar un dado is very commonly what you see in tabletop games as "to roll a die" or plural los dados "dice"

...

Now tirar is "to throw" and probably the most commonly used one for "to throw" in everyday life

It can be used in lots of situations and mostly synonymous with lanzar except for certain idiomatic expressions

One that might be a bit confusing is that tirar can also be "to pull" for some levers etc - you can also see jalar "to pull" or arrancar "to yank/pull"; like "to flush the toilet" is often tirar (de) la cadena which is literally "to pull the chain" and sometimes used with jalar

If that sounds odd just kind of think of "to throw a switch" and it's the same kind of idea

...

Now where you see a lot of variation is "to throw out garbage" because certain countries use different verbs but they're all kind of understandable

Some countries say tirar (de) la basura, other countries use echar la basura. And then some countries (I think Latin America mostly) use botar la basura which is a different "throw" but still "throw"

This can also extend to "to throw out"

And tirar can also be used as tirar(se) un pedo "to fart", and there are lots of variations on that

If you see an idiomatic expression with tirar it usually means "to throw", "to pull", or "to let out"

You can also see tirar used with "to shoot" like with disparar... so el tiro con arco is "archery" but literally "shooting with a bow"

el tiro can be "shooting" or un tiro can be "a shot" from a gun; and el tiro can sometimes refer to "a shot/kick" in sports

You don't see echar used with that at all

-

echar is most commonly "to fling", it's super common in a lot of idiomatic expressions:

echar un vistazo = to take a look [I think this is mostly Spain; lit. "throw a big look"]

echar de menos = to miss (something/someone) [Spain]

echar una mano = to give someone a hand [I think Spain?]

echar un cable = to give someone a hand [I think Spain?]

echar a perder = to waste / to spoil

echarse a perder = to go to waste

echar a suerte(s) = to flip a coin / to draw straws [lit. "to leave it up to luck(s)" but it's generally "to flip a coin" like to leave something to chance]

echar humo = to give off smoke [or "to be angry" like "to fume"]

echar chispas = to spark / to give off sparks [also "to be angry"]

echar una bronca = to give someone a telling off

echar(le) la sal = to jinx someone, to curse [lit. "to throw salt"]

echar/tirar leña al fuego = to add fuel to the fire / to give someone more ammo / to egg someone on [lit. "to throw firewood in the fire"]

echar agua = to water

echar tierra = to bury

echar raíces = to settle down, to put down roots

echar(se)/tomar una siesta = to take a nap

echar un ojo = to look over

There are also times when tirar/echar can mean "to waste" or "to throw out" or "pour down the drain", generally the same ideas

And sometimes it's weird because tirar/echar la casa por la ventana is "to break the bank" or "to spare no expense" [lit. "to throw the house through the window"] and you can use either one

But then something like echar agua al mar "to do something useless" like "to waste your time" or "to spend your time doing something that won't make a difference" [lit. "to throw water into the sea"] I usually only see with echar

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day of the Dead Vocabulary

Día de los Muertos

the Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico on Nov. 1 to remember the children in our lives who have passed, while Nov. 2 is reserved for adults.

los difuntos

the deceased loved ones are commemorated as a reminder to celebrate life.

la Catrina

the name of the female skeleton image dressed in upper class European garb and is most famously associated with this day.

el altar

the altar or shrine for the deceased installed at home with many offerings.

las ofrendas

the offerings, placed on top of the altar, consist of traditional items like flowers and candles; as well as items the deceased loved like tequila or a food dish.

la flor de cempasúchil

the Mexican marigold is traditionally used to adorn the altars and tombs of the deceased. Cempasúchil means ‘20 petal flower’ in the Nahuatl language.

las veladoras

the candles symbolize faith and hope. Its flames guide the souls on their way.

el pan de muertos

the bread of the dead is a baked sweet bread roll eaten throughout October.

los tamales

tamales are a corn based dough filled with meats, vegetables, and/or chillies then wrapped in a leaf and steamed.

el atole

a hot corn drink with added notes of cinnamon, vanilla, fruits, and/or chocolate.

las calaveritas de azúcar

sugar skulls are decorative skulls made of sugar and can be used as offerings.

las tumbas

the tombs of the deceased are visited and decorated with marigolds while eating dinner, listening to mariachis, telling stories, and celebrating with others.

Day of the Dead Phrases

Mexican people have a very humorous and creative way of talking about death. Here are a few common phrases that reference death in this way.

La Catrina al muerto se va a llevar, pero en la fiesta se va a quedar.

The Catrina may take the deceased, but they’re still staying to party.

La muerte está tan segura de alcanzarnos que nos da toda una vida de ventaja.

Death is so sure to catch up to us that it gives us our entire life as a head start.

Buen amor y buena muerte, no hay mejor suerte.

Good love and good death, there’s no better luck.

Hay que vivir sonriendo, para morir contentos.

Let’s live smiling so we can die happy.

El muerto a la sepultura y el vivo a la travesura.

The dead to the grave and the living to mischief.

Antes muerta que sencilla.

I’d rather be dead than basic.

Bendita la muerte cuando viene después de buen vivir.

Blessed is death when it comes after a life well lived.

Ya colgó los tenis.

He kicked the bucket. (lit. He hung up his tennis shoes.)

Sobre mi cadáver.

Over my dead body.

Vive y deja morir.

Live and let die.

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the general meaning and usage for "lo" in these examples "ella no es perfecta en lo absoluto" and "Ya sabes lo perturbador que puede llegar a ser eso programa"? Is this similar to the "lo" in "lo que"?

lo in general is used as a stand-in for a noun; it's often used to make an adjective a noun

For example lo perturbador reads as "what's disturbing", but more literally "that which is disturbing"

For example:

el asunto importante = the important matter

la cosa importante = the important thing

lo importante = what's important / that which is important

el asunto interesante = the interesting matter

la cosa interesante = the interesting thing

lo interesante = what's interesting / that which is interesting

el asunto curioso = the curious/strange matter

la cosa curiosa = the curious/strange thing

lo curioso = what's curious / that which is curious

When you use lo + adjective, the adjective always remains in what you'd think of as masculine singular, which is why it stays curioso there

[Note: This is different from a masculine noun; el rojo means "the color red" or "the redness"; lo rojo is "that which is red" - you also sometimes see masculine/feminine articles used with an adjective to describe a person - el encargado / la encargada is "the one in charge" so it reads differently in most cases]

Note: You also see it in some expressions - a lo hecho, pecho is like "what's done is done" but literally "to what's done, chest" ...like kind of "just take it and move on" in a way

You will also see lo de used a lot to sum things up:

lo de hoy = (concerning) today / today's (things)

¿Qué pasa con lo de viajar? = What's going on with the traveling thing?

Todo el mundo sabe sobre lo de los vecinos. = Everyone knows about what happened with the neighbors. [lit. "everyone [the whole world] knows about the thing with the neighbors"]

And then lo que is used with verbs as "that which is" or "what" - taking the place of a noun or abstract concept

Lo que no entiendo... = What I don't understand... / The thing I don't understand...

No saben lo que no saben. = They don't know what they don't know.

Eso no es lo que quiero decir. = That's not what I mean.

lo que almost always has a conjugated verb following it since que as "that" usually connects clauses

[aside from ¿Qué lo que? which I think is Dominican but it means "What's up?"]

-

Also, you didn't specifically ask but it does come up - you see lo bastante and lo suficiente + another adjective to mean "(adjective) enough"

By themselves as adjectives, bastante can be "very/quite" or "sufficient", and suficiente is "sufficient" like "enough food" or "plenty of chairs", that kind of thing and it works like normal adjectives. But when you add the lo it all stays in singular:

bastante comida = enough food

bastantes sillas = enough chairs

Eres bastante bueno/a. = You're pretty good. / You're quite good.

Eres lo bastante bueno/a. = You're good enough.

lo bastante is like trying to assign a goalpost that someone has met, so someone can be "good enough", "smart enough", etc.

-

From a grammatical sense lo is considered "neutral" or "neuter" gender, or sometimes "agender" - it looks like masculine, but it is considered "the absence of gender" because it usually shows up in the absence of a noun

You do see it from time to time but you rarely can tell what neutral gender is because it looks like masculine but the best way to explain it is uno vs. un/una

uno without a noun is "one"; un/una with a noun is "a"

If there's no discernible or implied gender, it's neutral

Others include:

él = he

ella = she

ello = it

este = this [m]

esta = this [f]

esto = this (thing)

ese = that [m]

esa = that [f]

eso = that (thing)

It's also why you'll see algún or alguna for "some (thing)" then alguno by itself, or ningún and ninguna for "not a single (thing) / no (thing)" then ninguno "not a single one / none"

Quick Additional Note: en absoluto can be used by itself here as "not at all"; en lo absoluto is like "not in the least / not in the slightest" as a noun phrase but you could use either here, the lo is like describing an abstract amount almost

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you help me understand what the second line is supposed to be? I imagine it has some colloquial significance but alas I don't know

(Thank you in advance I love you)

It's more like an idiomatic construction. There are lots of times you'll see por + adjective used where they omit the verb ser

What it means is: "We're not alone in the universe.... Well, you are because you're ugly"

It's like "for (being) + something"

Especially with kids you might see por malcriado/a "for being a brat"

Something along those lines

They also didn't put the accent mark on the tú but it's very common to use a pronoun + sí/no... like yo sí, tú no "I am, you aren't" or "me, not you"

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

not really a question about a specific sentence/situation but after finally getting comfortable with spanish pronouns i discovered that there are certain indicators for passive voice and one of them is se. in what contexts would you use this passive voice in spanish and could you explain more about the construction?? your blog is very helpful btw!!

This is one of the weird parts of Spanish - se has many functions and so it can be really confusing to see them all in different ways

I'm going to have a LOT to say below, so bear with me it's a long read and I'll try to explain everything, just know that a lot of it is very advanced in places

-

I'm assuming that you've seen se used in reflexives/pronomial verbs [like lavar "to wash" vs. lavarse "to wash oneself"]...

...And that you've probably seen se used to replace le/les when you're doing indirect objects + direct objects... lo escribo "I write it", le escribo "I write to him/her", then se lo escribo "I'm writing it to him/her"

...

Grammatically just know that se has MANY functions and they're all generally 3rd-person-related, and carries a more impersonal function

-

As for se in passive voice, first let me explain passive voice - I'm sure you have an idea of what it is but I'm going to briefly explain it like you're 5 so I'm sorry about that

Passive voice places emphasis on the object rather than the subject

Active voice = Subject verbs an object

Passive voice = An object is verbed (by Subject)

When you're first introduced to passive voice it's often done with ser in past tense + past participles + por (alguien)

El libro fue escrito en el siglo XVI (dieciséis). = The book was written in the 16th century.

El libro fue escrito por Cervantes. = The book was written by Cervantes.

escrito/a "written" being the past participle of escribir "to write"... and an irregular one at that; a past participle is really just the adjectival form of a verb

Most participles end in -ado or -ido; as adjectives they can change, but as past participles they're unchanging

[in other words: ha escrito "he/she has written", and then fue escrito/a "was written"]

Other more common examples:

Las galletas fueron horneadas por la pastelera. = The cookies were baked by the pastry chef (f).

El hombre fue empleado por la compañía. = The man was employed by the company.

La mujer fue empleada por la compañía. = The woman was employed by the company.

Fuimos contratados. = We were hired. [m+m, m+f]

Fuimos contratadas. = We were hired. [f+f]

Because passive voice focuses on the object, the verb will conjugate according to them... that's why las galletas fueron horneadas

If you wanted to phrase it in active voice: la pastelera horneó las galletas "the pastry chef (f) baked the cookies"

The por alguien part is not necessarily needed such as in fuimos contratados / contratadas.

-

As for passive voice with se, there's one more thing I need to point out

There's another almost identical construction that uses se and that is "impersonal se"

The more impersonal Spanish gets, the more se gets used... this is "one does" or "someone does"; an undefined person, often "one", or a "you" or "they" in English

¿Cómo se hace un pavo asado? = How do you make/cook a roast turkey?

Like I said though, they look almost exactly the same so your translation might change depending on what you mean; but in Spanish they're very slight differences:

Se habla español. = They speak Spanish. [impersonal]

Se habla español. = Spanish is spoken. [passive]

If you're reading about what languages a country speaks, these are pretty much the same idea so it's easily interchangeable.

¿Cómo se pronuncia llamar en Argentina? = How do they pronounce llamar in Argentina?

¿Cómo se pronuncia llamar en Argentina? = How is llamar pronounced in Argentina?

The only real difference is that impersonal is ALWAYS singular [because the subject as a "they" is considered singular ambiguous "they"]

And passive voice with se can be singular OR plural because it adheres to the object... which could be plural:

Se hizo un pastel. = They made a cake. [impersonal]

Se hizo un pastel. = A cake was made. [passive]

Se hizo pasteles. = They made cakes. [impersonal]

Se hicieron pasteles. = Cakes were made. [passive]

-

Now we get into the more advanced stuff, and I mean this is C2 level the most advanced and least explained parts of se, that native speakers will use and your textbooks rarely talk about

This whole thing is classified as "superfluous dative" which is a linguistic subset - essentially times you use se when it doesn't seem to fill a grammatical function

[note: "dative" means "indirect objects", or "to whom or for whom something is done" - it places more emphasis on who is receiving the benefits/inconveniences of something that is done]

Predominantly it's used in dativo ético or "ethical dative", which again just means it places more emphasis on the person receiving the benefits/inconveniences which will make sense later. But for linguistic purposes in things I barely understand, just know that superfluous dative has multiple terms under it for specific functions/things but dativo ético is probably the most common one under that umbrella

...

The passive se is especially used in expressions of things that "were done", or things that "happened" to people. This is most commonly used for things that were unexpected, inconvenient, or for trying to place the blame on someone else

You'll probably notice this in verbs that are "reflexive" but don't have the same reflexive meaning you normally associate with the idea... Meaning that lavar "to wash" and lavarse "to wash oneself" makes sense, but then you'll have something like dormir "to sleep" vs. dormirse "to fall asleep"

...And dormirse doesn't come out as "to sleep oneself" so it is a bit weird as a reflexive... that's dativo ético

This is most commonly introduced with olvidar vs. olvidarse

olvidar = to forget [which feels purposeful in some cases]

olvidarse (de) = to forget [which is more common]

But you'll have seen it with other verbs like ir/irse "to leave/to go away", mudar/mudarse "to change / to move (residences)" or romper/romperse "to break/break down" and also morir/morirse which morir is "to die", but people will sometimes use moririse as "to pass away suddenly".

The -se endings seem to give the verb a whole separate meaning or more nuance

It can be used as a with additional indirect objects to show specifically who was benefitted/inconvenienced:

Se acabó. = It's over. / It ended.

Se me acaba el tiempo. = Time is running out for me.

Rompí el coche/carro/auto. = I broke the car. [purposeful]

Se rompió el coche/carro/auto. = The car broke down. [on its own]

Se me rompió el coche/carro/auto. = The car up and died on me.

Se me durmió la pierna. = My leg fell asleep (on me).

Se me durmieron las nalgas. = My butt fell asleep (on me).

Mis estudiantes se me dormían. = My students were falling asleep on me. [as in "my students were falling asleep during (my) class"]

Se me cayó el diente. = My tooth fell out.

Se me olvidó el libro. = The book totally slipped my mind.

Se me olvidaron las llaves. = I forgot my keys. / My keys completely slipped my mind.

*Note: In these cases you'll be using indirect objects... so se + me/te/le/les/nos/os + verb

You'll occasionally see this written in infinitive form with the le attached... like olvidar "to forget", olvidarse "to forget" (more passive), then olvidársele "to slip one's mind" meaning extra passive dativo ético

...

And so you'll find that with passive and expressions like this objects will "become forgotten (themselves)" to someone, a bus will "leave itself to someone", etc

These expressions carry an inherent lack of control and occasionally lack of guilt or responsibility... like saying se rompió el espejo reads like "the mirror broke all on its own" and implies you had nothing to do with it, while se me rompió el espejo implies that it also negatively affects you but that you had nothing to do with it

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you maybe talk a bit about when to use "acabar de", "justo" and "sólo"? Thanks!

The short answer is that if you had a venn diagram, acabar de would be on one side, solo would be on the other side, and justo would be the overlap

-

acabar de needs an infinitive for "to just have done something". It reads as "just done" or "recently done", but it's a kind of "past tense adjacent" way to say things

Acabo de leer tu mensaje. = I just read your message.

Acabamos de comprar las zanahorias. = We just bought (the) carrots.

Me acaban de decir que... = They just told me that...

Also note: acabar by itself means "to finish"; acabarse means "to run out" [like se me acaba el tiempo "time is running out for me"; or se me acabó la harina "I ran out of flour"]. And acabar con (algo/alguien) is "to get rid of" or "to do away with"

-

justo/a as an adjective means "just" or "fair" [it can also be used for "tight" with clothes; different application]

justo as an adverb - unchanging - means "just done something" OR it means "only"

It can be either; justo as an adverb is also used as "precisely" or "right (at that time)"

Lo hice justo después. = I did it right after.

Justo ahora... = Just now...

-

The last one is a bit of backstory

solo/a as an adjective means "alone" or "on one's own" or "lonely"

Adverbially solo (or sólo) means "only"; it's that kind of "just"...

Now, you don't need the accent mark for solo anymore. It's sometimes kept for vocal emphasis, the way some people emphasize "only". It used to be used more frequently to distinguish the adjective from the adverbial form, but today you'll see solo more often with no accent mark

You can absolutely include it though

solo/sólo will be used as "only" as in like "just (a certain amount)"... it is used for expressing limitations, so it's not the same as acabar de

Solo hago lo que me digan. = I just do what they tell me.

No solo yo... = Not just me... / Not only me...

Solo digo la verdad. = I'm just telling the truth. / I only tell the truth.

In some cases you will also see solamente which is "only" but a little more fancy, "solely" which is the expressed adverbial form of solo [the -mente form, if you will]

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, I was wondering when to switch between the imperfect and preterite tenses? I’ve been reading some spanish texts and I’ve noticed that the imperfect is the main tense used, but I also see the preterite thrown in sometimes.

I'll link to my other things I've done on this in a reblog since I'm on my phone atm but it comes down to narration vs action a lot of the time

In linguistic terms "perfect" means "completed" [lit. "thoroughly done"], so "imperfect" means "not yet completed"... the imperfect tense is used for things that may or may not still be happening or continuing, so it is often used for narration and description

Imperfect is often used for:

narration, description

continuous past ("was doing", "was eating", "was sleeping")

used to, was in the habit of

telling time - always imperfect (era la una, eran las dos, etc)

soler + infinitive as "used to" as past tense is ALWAYS imperfect; there is no preterite form accepted so you normally only see soler in present tense "to be in the habit of" and imperfect "used to"

Preterite is commonly called "simple past", where it is things that happened and are done, and they are actions

In terms of reading, it's more that imperfect introduces something and describes it, while the preterite shows an "interruption" or "the action"

A common example I like to use:

Dormía y sonaba el teléfono. = I was sleeping and the phone was ringing. [imperfect + imperfect; no interruption, background description]

Dormía y sonó el teléfono. = I was sleeping and the phone rang. [imperfect + preterite; involves an "interruption" of an "action" to the background description]

If you use the two imperfect, it sounds like someone was sleeping through the phone ringing, and/or that the phone ringing was part of the background. If you use imperfect and then preterite, it implies the preterite was a sudden occurrence that breaks up the narration.

...

But please be aware that most verbs can exist in the two different tenses and it becomes a matter of how they're understood...

Assuming 3rd person singular - se dormía would be "was falling asleep", while se durmió would be "fell asleep"

Sometimes it really depends on the mood - especially with ser and estar in preterite or imperfect - like you don't see too much difference between ¿dónde estabas? "where were you?" vs. ¿dónde estuviste? "where were you?" except in context where preterite feels more like interrogation "where were you (at that specific time)?"

...

There are a handful of verbs that change meaning depending on preterite and imperfect

I'll link things below that will explain it more but in general be wary of:

poder

no poder

querer

no querer

conocer

saber

haber

And also tener. Where normally tener is imperfect as preterite tener can come across as "to obtain", but there are so many idiomatic ways of using tener like "hungry", "thirsty", "hot/cold", and your age that there are times when preterite could be used. Still, in general, preterite tener is most often a synonym of conseguir or obtener as "to get"

-

Additional links:

A Linguistic Perspective on the Spanish Past

More in-depth explanation of imperfect

Using soler

The imperfect tag

The preterite tag

Preterite and Imperfect Contrasted from Bowdoin

Spanish Tenses & Moods Masterpost

131 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anatomy of Spanish: A direct object [objeto directo] is the part of the sentence that receives the action. In other languages that have case systems, direct objects are known as “accusative”. Direct objects are used for the sake of brevity, when the object is known there’s no need to include the noun itself.

In Spanish, a masculine direct object can be substituted for lo in singular, and los in plural. A feminine direct object can be substitued for la in singular, and las in plural.

The direct objects stand in for definite articles (el libro / la flor = “the book” / “the flower”) or for indefinite articles (un libro / una flor = “a book” / “a flower”).

Pay special attention to where the direct object goes when it's lo / los or la / las - before the verb.

In English, direct objects are often translated as “it” or “them”. But sometimes direct objects can be people; in English it would be something like lo conozco “I know him” or la conozco “I know her” instead of the longer sentence.

*Note: It’s totally okay, and is probably preferable, to just say compro un libro / lo compro and leave out the yo. This is just done for the sake of being specific; the compro only exists in present tense yo so there’s no confusion as to what the subject of the sentence is. If it were 3rd person compra you might have to specify if it’s “he”, “she”, or “You (formal)”, or compran “they (masculine / masculine + feminine), “they (feminine only)”, or “You all”… but the other conjugations (compro, compras, compramos, compráis) only apply to one potential subject.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Finalmente acabé mi clase de español II hace unas semanas. Recebí un A. Mi universidad no ofrece español III hasta septiembre así que planeo practicar mi español con varios tutores por el verano. También, voy a trabajar delante en mi libro de texto así que estaré más preparada para español III.

Esta semana es un semana muy mala. Estoy enferma. Tengo un resfriado. Mi novio es enfermo también. Pero mi jefa en mi trabajo es súper simpática y me permitió salir del trabajo temprano. Salí al mediodía. Planeo trabajar mañana. Espero que me siento mejor.

_______

I finally finished my Spanish II class a few weeks ago. I received an A. My university isn’t offering Spanish III until September so I plan on practicing my Spanish with various tutors through the summer. Also, I’m going to work ahead in my textbook so I will be more prepared for Spanish III.

This week is a very bad week. I’m sick. I have a cold. My boyfriend is also sick. But my boss at my job is super nice and allowed me to leave work early. I left at noon. I plan on working tomorrow. I hope I feel better.

(Las correcciones son siempre bienvenidas.)

#espanol#spanish#spanish practice#aprender español#learning spanish#work#trabajo#sick#enferma#writing practice#learning languages

1 note

·

View note

Note

i have a question about something -- i say "paso por ti" if im telling someone im passing by for them later today or something but im realizing that isn't the technical future conjugation, that'd be "pasare por ti". is there a reason we say paso instead of pasare. if you say it in the conditional is that saying that you aren't sure so have a back up plan lol

This is actually a very common question or concern. The thing is that present tense can also be used for short-term future

Like the way people say voy al banco can be "I'm going to the bank" or like in the very short future "I will go to the bank"

Another one is nos vemos as an expression is "see you later" but more literally "we will see each other"

(Also I'm assuming you mean pasar por alguien in the sense of "to come get someone" or "to pick someone up" in that sense?)

Using future tense pasaré por ti "I'll come get you" isn't wrong, it just feels more distant future planning... Like I'd say paso por ti enseguida "I'll come get you right away", or paso por ti temprano "I'll come get you early"

Present tense generally has three-ish basic meanings, the regular statement, present continuous, and short-term future. In other words if you say voy it could be "I go", "I am going", and "I will go (shortly)"

-

As for conditional, it would probably make more sense in an "if/then" statement which can be more actually hypothetical with imperfect subjunctive

si me hubiera pedido, pasaría por ti "if you had asked me, I would have come to get you"

...

In a regular sentence that isn't so hypothetical you might say, si me pides, paso por ti "if you ask, I'll come get you" or paso por ti cuando termino "I'll come get you when I'm done" which are more certainty-based statements

Subjunctive is more doubtful but possible... and conditional needs a condition to be met, in other words, "I would get you (assuming something were to happen)"

~

Related: I wouldn't say conditional sounds like a back-up plan it just requires something else to happen first, like "if only I could", "if I had time", "if I were there"... those kinds of expressions are often imperfect subjunctive, followed by conditional. If you were going for a more doubtful present-y feeling it would be present subjunctive

That more reads like doubtful like less than 50% probability or there are certain subjunctive phrases...

Like, es posible que pase por ti antes "it's possible I'll come get you sooner/before"

And it can exist with regular subjunctive - paso por ti cuando termine la película which reads as "I'll come get you once the movie ends" as if you don't know when it will end

Note here that present subjunctive has the same future-y quality as regular present indicative, like cuando termine la película "whenever the movie ends" vs. cuando termina la película "when the movie ends" both have the same element of "hasn't happened yet"

Same would be true for es posible que pase por ti "it's possible I'll come get you" it's just an indefinite future versus regular indicative paso por ti "I am going to come get you"

-

I think in this particular context, all of it can make sense it's more just the vibe of it; certain or uncertain, short-term or long-term planning, etc.

Present tense is a very nuanced tense in my experience; English tends to use more modals to express things like "will" or "would" which makes us question the exact timing of certain tenses

For us "I go", "I am going", and "I will go" require entirely different words (which Spanish does have) but it makes it hard to understand when Spanish present tense could possibly be any one of them

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

How often is the conditional tense really used in spanish? I feel like I almost never see it unless it's used with poder. I feel like many of the instances when we would use conditional in English work better with subjunctive in Spanish. Would you say my instincts/observations are right?

The conditional tense is used a decent amount, though sometimes it's replaced by other tenses in indicative, not usually (but not always) by the subjunctive

Typically, conditional tense is used for hypothetical situations, what someone "could" do - but implies a certain possibility

As an example: puedo ir "I can go" vs. podría ir "I could go"... both kind of imply the same thing, but podría feels like future planning or a specific "if/then" sentence; but just by themselves they seem interchangeable

Meanwhile I would consider subjunctive to be a more doubtful "might", conditional is more certain "could" or "would be able to"

The primary way that conditional is used is for "if/then" statements, although there are cases where conditional is omitted. Typical standard Spanish says "if" is imperfect subjunctive, while conditional is "then"

Si fueras rico/a, ¿qué harías? = If you were rich, what would you do?

Si tuvieras la oportunidad, ¿qué dirías? = If you had the chance, what would you say?

Viajaría más si pudiera. = I would travel more if I could.

*Note: Imperfect subjunctive has 2 different forms, the ones that seem to end in -ara/-iera are more common in Latin America genereally, and the ones ending in -ase/-iese are more common in Spain; this is really more about imperfect subjunctive when it's used as contrary to fact statements / unlikely hypotheticals which read as for the sake of argument - "if you were", "if you were to", "if you could have" etc.

Again, sometimes people omit the conditional here and use both imperfect subjunctive but standard Spanish definitely uses conditional more

-

What you quickly find with subjunctive vs conditional is that English doesn't have a very clear distinction. We use "could", "would", and "should" for past, subjunctive, and conditional which makes it very difficult to recognize it in Spanish

As an example si podría "if I could" implies a certainty, while si pudiera reads more doubtful like "if only I could"

Even "were" is odd in English - "we were" [fueron/eran] is past tense, but "if I were" [si fuera] is imperfect subjunctive

-

Related to the section above, is that very often "should" is debería in conditional

This confuses even native Spanish speakers as they try to decide if an expression "coulda, woulda, shoulda" sound better in conditional or imperfect subjunctive

[Note for non-native speakers: this is colloquially a form of "could have, would have, should have" but as an expression you kind of just shorten it to "coulda, woulda, shoulda" and it sometimes comes in different variations like "woulda, coulda, shoulda"]

In my experience, standard Spanish does them typically in conditional - talking about a "then" statement were the implication is "if only" which is imperfect subjunctive... like "(if only I had known) I could have / would have / should have"

An important distinction: debería as "should" is often used for things that haven't been done yet, like making plans... if talking more about things someone "should have done" in the past, you sometimes see it in past tense debía/debió like "must have / ought to have"

I find debería as "should" gets more used in talking about regrets or making plans - if not just regular present tense

I see a lot of debería + haber... like no deberíamos haber llegado tarde "we shouldn't have come late", deberían haber dicho la verdad "they should have told the truth", deberías haberme llamado antes "you should have called me earlier/sooner"

...

However, you're not wrong in thinking that conditional feels a bit redundant with subjunctive, that's why there are parts of the Spanish-speaking world that don't use conditional as much. The typical replacement is imperfect subjunctive

But in castellano [official Spanish] at least, and in a lot of literature, you still see conditional used... colloquially however, conditional is sometimes less common

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you know of any adjective order rules in spanish? not necessarily rules as in "anything else is wrong", but in "anything else sounds weird"

(like in english, where "brown big bear" isn't technically wrong, just... weird)

Okay FYI I ramble a lot in this, and I tried to make it clearer in places but just know that this is a lot of stuff, and I repeat myself, and though there are some rules, sometimes it's about feeling and what sounds right rather than a regular rule

Regardless of whether the adjectives go in front or in back, just know that Spanish (and English) tends to put adjectives of opinion, size, origin/nationality, color, and quality as the most important

Other adjectives like determiners take precedence always

And other adjectives are stuck to the noun as a collocation. More below.

-

There are four things I just need to say first and then we'll really get into it:

For your basic average garden variety adjectives, they typically go behind the noun like la flor hermosa "beautiful flower". If you put them in front, you're sounding extra super fancy poetic lyrical so do this sparingly or for Dramatic Flair; la hermosa flor "the beautiful flower" sounds like I'm reading poetry

There are some adjectives that change meaning depending on placement - prime example is mismo/a, where you can say la misma cosa "the same thing" vs. la cosa misma "the thing itself", where mismo/a is related to "same" or "selfsame" [like el mismísimo rey "the king himself" or "the very king himself"]. Literally it is "selfsame"... in front "same", in back "self". Another one is antiguo/a which in front often means "ancient" or "antique" or "former", while in the back it can be "old" as in "old-fashioned" or "antiquated". And bueno/a and malo/a for "good" and "bad" will constantly confuse you too

There are certain adjectives that are what we call "determiners" that are almost always in front (except occasionally for dramatic effect). A determiner is usually a specific adjective like possessive adjectives, demonstratives, adjectives of quantity (mucho/a, poco/a), and question words just to name a few. Determiners are also the definite and indefinite articles - el, la, los, las and un, una, unos, unas, and also includes numbers both cardinal [one, two, three] and ordinal [first, second, third]

A very important thing to note about adjectives is a potential "collocation" - meaning a noun + adjective that work together as a sort of cohesive unit. An example las bellas artes is "fine arts", but literally "the beautiful arts" but written fancy-like because bello/a meaning "beautiful" would typically go behind. In this case, las bellas artes is almost like a separate piece of vocab because you can't really separate them. Another would be something like el oso pardo which is "brown bear" or "grizzly bear", the adjective pardo/a refers to a brownish coloring but in this case it is stuck to oso almost like it's a specific descriptor that makes it a full "unit". These are best learned like your normal vocab, or understood as compound nouns that you can't break up... things like el agua dulce "freshwater" [instead of salt water], la sal marina "sea salt", las malas hierbas "weeds", la luna llena "full moon", el águila calva "bald eagle", el pavo real "peacock", la caja fuerte "safe/lockbox" etc etc.

-

Essentially, the adjectives are free to move around, except for when they're not

When it's your regular adjectives, you're free to say them in any order you like - they're regular descriptions, and all you need to keep in mind is potentially when y turns to e / o turns to u, and little grammatical hiccups like that:

Su ascendencia es alemana, irlandesa, e italiana. = Their heritage is German, Irish, and Italian.

Su ascendencia es italiana, irlandesa, y alemana. = Their heritage is Italian, Irish, and German.

No difference though I would personally assume the first one you mention is maybe the most important or the largest part.

Same with general descriptions:

Es un edificio notable y llamativo. = It's a notable and eye-catching building.

Es un edificio llamativo y notable. = It's an eye-catching and notable building.

Es una mujer lista y trabajadora. = She's a smart and hard-working woman.

Es una mujer trabajadora y lista. = She's a hard-working and smart woman.

Where you get into iffy territory is when adjectives come in front

I personally would say if you're using bueno/a or malo/a in front of an adjective it's one that almost always goes first except if there's a determiner:

el buen hombre = the good man

un buen hombre = a good man

este buen hombre = this good man

la buena mujer = the good woman

una buena mujer = a good woman

esta buena mujer = this good woman

Same with other determiners like cualquier buen hombre "any good man", cada buen hombre "each good man", muchas buenas mujeres "many good women" etc.

This is also something to keep in mind with collocations and set phrases:

En el Antiguo Egipto, había dos reinos distintos - Alto Egipto y Bajo Egipto, y en las épocas posteriores se unificaron, y fueron gobernados por unos poderosos reyes-dioses conocidos como los faraones.

"In Ancient Egypt, there were two different kingdoms, Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, and in later times they united and were governed by some powerful god-kings known as the pharaohs."

So let's examine that further:

Something like el Antiguo Egipto, el Alto Egipto, el Bajo Egipto or something like el Imperio Antiguo "the Old Kingdom" of Egypt are collocations, consider them their own vocab and try not to think too hard on it because sometimes they're just set phrases like la Antigua Grecia "Ancient Greece", Gran Bretaña "Great Britain", or el Sacro Imperio Romano "the Holy Roman Empire"

A word like poderoso/a sort of becomes a more intense verison of itself changing its normal location; if it were el rey poderoso you might translate that as "powerful king" or "strong king", putting el poderoso rey adds some oomph to it and now it's "the mighty king" as if that's the most important aspect of it and it's exceptional - and regular adjectives can follow normally; el poderoso rey conocido como "the mighty king known as"

-

I should also mention that there are adjectival phrases involving de, but you've probably seen them already... like... es un libro de literatura infantil "it's a children's literature book"

I think this is more specifically like "the genitive case", which is normally used linguistically to talk about possessives or qualifiers of some kind, but they are often attached directly to the noun and tend to preempt most adjectives:

El maravilloso mago de Oz es un libro de literatura infantil estadounidense muy popular. = The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is a very popular book of children's literature.

-

...Again, just some general notes because I feel like I was rambling a lot:

Adjectives sometimes go in front or behind the noun depending on their function in the sentence

Most adjectives end up behind the noun

Determiners pretty much always go in front 95% of the time

The articles - el/la/los/las or un/una, unos, unas are the first determiner adjectives 99.999% of the time; possessives can take the place of articles... el dinero "the money" vs. su dinero "their money"

Determiners of numbers (cardinal numbers or ordinal numbers) are almost always the second adjective mentioned, even if there are other determiners... el primer paso "the firststep", mi primer paso "my first step"

Adjectives like "good", "bad", "big", and a few others are often the next adjectives if there are other determiners... el primer gran paso "the first great step" or mi primer gran paso "my first great step"

As a quick example... las tres buenas hadas "the three good fairies"... 1st is las as the article, then tres is a cardinal number, and then you have the adjective of quality "good"

Some adjectives can change meaning depending on placement - las tres buenas hadas "the three good fairies" implies that "good" is their main quality, as opposed to evil. But if you said las tres hadas buenas it comes out as "the three nice fairies" as if you're talking about personality

Keep an eye out for certain collocations and set phrases that should be treated as separate vocab and not to be separated - esta noche "tonight", la prensa rosa "tabloids" [lit. "pink press"], or la montaña rusa "rollercoaster" [lit. "Russian mountain"]

Collocations or set adjectival phrases like de can't be broken up... la luna de hoy "today's moon" vs. la luna llena de hoy "today's full moon" / and la luna de esta noche "tonight's moon" or la luna llena de esta noche "tonight's full moon"

If you're adding nationalities, they tend to show up immediately after the noun or the first noun phrase since they qualify everything - la literatura infantil popular "popular children's literature" vs. la literatura infantil estadounidense popular "popular American children's literature" or la literatura infantil francesa "popular French children's literature"

If you're doing a list of regular adjectives, you can probably put them in any order you want

But be aware that some adjectives go in front more and some go in back more, and sometimes it's a matter of style - such as el famoso oso panda chino "the (very) famous panda bear from China"

Certain qualities like "big/small", nationality, "good/bad", "elder/younger" do take priority though; as an example mi heramana inteligente "my smart sister" vs. mi heramana menor inteligente "my smart younger sister" or mi hermana pequeña inteligente "my smart little sister"

Additionally:

Adverbs always go in front of the adjective they're modifying... la familia más conocida "the most well-known family", una historia muy larga "a very long story"

Possessives in their more adjectival form ALWAYS go after the noun... su libro "their book" vs. el libro suyo "the book of theirs"; this is part of the genitive/possessives but possessives

Don't separate collocations or set phrases or things get confusing

I wish I could be more specific but this is really contextually-based and so it becomes more like give me an example and I'll tell you what I think sounds the most natural

What I can say is that you get a feel for what sounds the most natural as you go and you get more examples in your daily life of what sounds right or what just sounds a little bit off

But, Spanish-speakers probably will understand generally what you mean even if something sounds a little off as long as you don't separate the set phrases

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mi clase de español II es casi terminada. Tengo que hacer el examen oral, y estoy muy nerviosa, como siempre. Creo que es porque tengo que hablar con mi profesora y sé es una prueba. Odio pruebas.

Mi universidad no ofrece español III este verano así que iba a asistir antropología cultural, pero tengo unos problemas crónicos de salud que estás ¨flaring up¨ (no sé como se dice eso en español) ahora. Así que decidí tomar una clase se llama caminar por la salud. Necesito una clase de educación fisica para mi título universitario y será buena para mi salud. Luego, puedo tomar español III en el otoño.

Vivo cerca de un bosque. Está verano, y tenemos un comedero para pájaros y mi novio y yo vemos tantos tipos de pájaros diferentes. Entonces, los mapaches llegaron. Y entonces, las ardillas...y entonces las ardillas listadas...y entonces los venados. Los venados comen las semillas que caen al suelo. Es genial. A mi me encantan los animales. :)

----------------

My Spanish II class is almost over. I have to do the final oral exam and I’m really nervous, as usual. I think it’s because I have to talk with my profesor and I know that it’s a test. I hate tests.

My university doesn’t offer Spanish III this summer so I was going to take Cultural Anthropology, but I have some chronic health problems that are “flaring up” now. So I decided to take a class called Walking for Health. I need a physical education class for my degree and it will be good for my health. Then, I can take Spanish III in the fall.

I live near a forest. It’s summer and we have a bird feeder and my boyfriend and I see so many different types of birds. Then, the raccoons arrived. And then the squirrels...and then the chipmunks...y then the deer. The deer eat the seeds that fall to the ground. It’s great. I love animals. :)

------------

(Las correcciones para mi escritura son siempre bienvenidas.)

#spanish#learning spanish#español#espanol#spanish practice#animals#animales#spanish ii#aprender español#languages#romance languages

1 note

·

View note

Text

accessible classic lit in spanish

tale as old as time: a learner asks for a classic reading rec and people suggest masterful works like don quijote and cien años de soledad. these are WONDERFUL works of fiction but they're not really level appropriate for someone who is trying to start reading classic lit. so here are some recommendations for someone who wants to start reading but is a bit intimidated by these works. they are by no means an absolute cakewalk to read, but a lot less demanding than the novels mentioned above. here are the criteria i used to select books:

(relatively) canonical: i tried to stick to things i read in college and names that are relatively recognizable. it's easier to start conversations with others about these authors because they're widely read.

on the shorter side: to make it easier to get through the book and to help build stamina. it's like training for a marathon, you don't go out and run 26 miles on your first day

simpler language & graspable plot: it takes some getting used to to be able to read different styles, so i picked things that are a bit simpler and not filled with time skips and narrator changes every step of the way

20th and 21st century: just to keep things a bit more relevant. there are some great works pre-20th century but again, the style takes some getting used to

some of the recommendations might not fit all four criteria, and i'll specify when. that said, i think these are all good options for starting out:

aura, carlos fuentes (mexico, 1962): probably the shortest on the list, gothic, written in second person, really just an enjoyable read. i feel like this should be every learner's first novel in spanish just because of how accessible it feels.

la última niebla, maría luisa bombal (chile, 1934): also quite short, and usually paired with la amortajada, so if you like it, check that novel out as well! bombal's work is very concerned with the position of women in society and uses the gothic to get that across.

el coronel no tiene quien le escriba, gabriel garcía márquez (colombia, 1961): if your heart is SET on cien años de soledad, this is a great alternative by the same author. much shorter but still has the signature garcía márquez feel.

la casa de los espíritus, isabel allende (chile, 1982): this one is on the longer side, but i found it to be like. cien años de soledad written for eighth graders. it's got the same dynamics (magical realism, history of a country, intergenerational story, etc). but just simpler. it's not a bad story by any means.

abel sánchez, miguel de unamuno (spain, 1917). this is the bibical story of cain and abel but told in modern times and in spain. probably my favorite of unamuno's novels (if not niebla). his style is relatively straightfoward in the sense that he isn't constantly looking for the most flowerly language. since it is older than the other novels, you'll have to look out there, but it's still an entertaining option

ficciones, jorge luis borges (argentina, 1944): ok this is cheating. it's not a novel but rather a collection of short stories, AND borges' style can get quite convoluted. i'm putting it here because during my undergrad we read a ton of borges' short stories and they are always very thought provoking and linguistically helped push my limits. since they are stories, you can stop after one if it was too much, later revisit it, let yourself be challenged. my most fondly remembered stories from this collection are la muerte y la brújula, funes el memorioso, and las ruinas circulares

and that’s it for the list! if you’ve read one of these or decide to read one because of this post, let me know what you think! i’m working on making a list of more accessible materials for my students :)

956 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spanishskulduggery - Spanish Tenses & Moods Masterpost

In Spanish, the various tenses are known as los tiempos and can be divided into three basic categories: the indicative, the subjunctive, and the commands.

This masterpost is designed to help those who are trying to learn Spanish better navigate a particular tense.

This will serve as an overview of the various grammatical tenses and moods in Spanish, and some extra links and lessons on them, many from questions I’ve answered or from StudySpanish’s grammar section, or extra things from other people (all credit the respective creators).

Note 1: This is going to be probably repeatedly updated, with more and and more sources as I find them, or create them myself.

Note 2: Some of the links are the same but in different sections if they apply to different tenses.

Note 3: This post talks about Spanish tenses and moods, not other Spanish grammar.

(Please let me know if there are typos, or if a link’s not working etc.)

Keep reading

972 notes

·

View notes