Text

First things first: this isn’t a biography, despite the use of the word—twice!—on the back of the cover. It is, instead, a memoir of Divine by his personal manager.

Having known nothing about Bernard Jay before reading this, I quickly smelled bullshit, and this book reeks of it. Reading between the lines, it becomes apparent, almost immediately, that Jay was a huckster who exploited Divine throughout most of his career.

Divine reads like a secondary character in this “biography,” a deeply unhappy man forced to endure years of touring and recording sessions, and, despite frequent tours and hit singles throughout Europe’s, a man who was always broke, who spent more than he made because, in part, he somehow never seemed to make money.

Jay didn’t interview any of the Dreamlanders for this book. His treatment of John Waters and his eclectic crew of actors and artists is mean-spirited, and it feels as if he had many axes to grind.

John Waters is barely mentioned in most of this book. When he is discussed, he’s dismissed as a worthless side character, as someone almost detrimental to Divine’s career and not as the architect of it. (Divine was Waters’s creation. Van Smith designed his looks and Waters created the character, his personality, and even named him, yet this is largely played down or ignored here.)

The treatment of Divine’s parents, especially of his mother, is as mean-spirited as the treatment of Waters and company.

Jay seemed determined to portray Divine as largely a product of his manager’s success. The phrase “my star” appears in every single chapter, usually multiple times in a chapter. It’s hard to read this book and walk away with a positive opinion of Bernard Jay.

Throughout the book, Divine in many ways feels like a secondary character, and we never get a sense of who he was. Often, he’s portrayed as someone deeply frustrated and unhappy with his life’s trajectory, a course established and paved by Bernard Jay.

This isn’t so much a biography of Divine; instead, it’s an essay on how unhappy he was as the result of decisions made by his huckster manager.

Harris Glenn Milstread, Divine, deserved better—in life and as the subject of a biography.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Thinking Animal

by D. Dickey

—So tell me why you’re here.

—I’m tired. Not exhausted, but … just, I don’t know, tired. Sarah’s wearing that gray face sad people wear, that mask with dead eyes looks like an unpainted statue.

—Can you describe it? “Tired” is so …

—Not clear?

—Mmm Hmm.

—I didn’t want no attention, she says. —Some people, I think, will think I did it for attention. But it wasn’t attention I wanted.

—What did you want? What did you hope to achieve?

—Shit. What you think?

—And that seemed like a solution?

—No, she says. —Not a solution. An escape.

—But an escape’s not a solution.

—Didn’t say I was looking for no solution. Escape sounded fine by me.

The doctor glances at his notes. He spins his pen between his fingers and clicks his tongue. Seems like there’s some place he’d rather be, like maybe drinking martinis on his yacht or whatever it is doctors do when they ain’t talking to suicides.

—It says here you’re on LexiPro and Wellbutrin, he says. —Were you taking them when you attempted …

—Hell yes I was, Sarah says. —They numbed things, but they didn’t stop the thoughts, the bad thoughts flying through my head. They didn’t make me feel full when all I feel is empty all the time.

—Elaborate on that, would you please?

—On what? Feeling empty?

—Mmm Hmm. Just how you feel in general. Guide me on a tour of a day in your life. And don’t leave anything out.

A clock on the wall ticks, ticks. Sarah feels her eyes pull toward it, like they hear the ticks and want to see what time it is, even though she ain’t much interested in the time, and she don’t even really want to look. But then it’s too late. She’s looking. And what does it matter what time it is, anyway? Ain’t like she’s got anything better to do. They holding her here for three days. They have to by law, or so they say. So what’s time matter anyway?

But then now the clock’s distracted her. And so she tries to think what to say. How does she even tell him about that empty feeling? How can she even describe it? Like it’s like this feeling crawls through her, like her bones is made of those hollow plastic tubes they use for plumbing, like her organs and skin are balloons filled with that stuff … What’s it called? Helium. Like everything she sees is gray. And everyone she sees is practically pretty much dead. That’s how she sees everyone: dead. They just walking corpses ain’t realize yet they dead—or will be soon.

Or so should she even tell him about how she stands in the bathroom in front of the mirror, staring at her face and eyes? Should she even bother trying to explain how dead her face looks? how it usually seems like it don’t even belong to her? how sometimes she stares at her face so long it seems to fade and age, and how her eyes usually—not always but usually—seem dead and decayed and …

But then what’s it even matter? What’s it matter what she tells him? Ain’t no one can help her. No one’s been able to help her yet. But then she thinks, ‘why not?’ Ain’t like she’s got anything better to do.

—What compels you to stare at yourself in the mirror? the doctor says.

—Don’t know. Just something to do, I suppose.

—What about when you’re at work? Do you find it difficult to interact with co-workers?

—Don’t work.

—Then social functions: how do you cope when you’re around other people?

—I don’t like spending time with other people much, she says. —They too sad, too dead and sad, and it makes me feel like my bones want to jump out my skin.

—What do you do all day?

—Watch TV. Or sit online. Sometimes I sit on the couch with music playing and just kind of stare at the wall.

—What do you think about when you’re doing that?

—Sometimes I don’t think nothing, she says. —And sometimes I think about … I don’t even know.

What does she think about? Should she bother to tell him about the time she stared at the wall for so long she saw her thoughts scroll across the wall like they was part of that stream of words scroll across the bottom of news shows? Or what about that time she watched her marriage break down, watched it right on the wall, like she was watching reruns of a TV show she didn’t like the first time around? Maybe she should tell him about the way she like sits and thinks about maybe going on some TV show, maybe trying out for some reality show to make herself famous. Or rich. Or about how she sometimes thinks she should start playing the lottery. How she sometimes wonders if being rich will solve her problems.

But then she ain’t never heard of money making people feel less dead. Everyone knows money don’t buy happiness. Just look at the celebrities with lives like one long-running gossip column. She don’t even really think money can solve her problems. Her problems is in her head. Her problems is the fact—the sad and tragic fact—that everyone losses everyone, that happiness don’t or can’t or won’t last, that everyone does and will die. And ain’t nothing gone happen after death. Be a fool to think otherwise. You die and that’s all there is. You die and then … nothing.

—So you’re not, I take it, religious? the doctor says. —Do you believe in God?

—Which one?

—The Son, the Father, and the Holy Ghost.

—So I take it you a Christian.

—I am.

—Good for you, she says. —But it don’t do nothing for me. If God exists, he ain’t helped me none. If God exists, I got a bone to pick with him for making me this way. For making me at all.

The doctor flips through his notes. His face and eyes are red, like he’s drunk or sick or ready to pass out or something.

—There’s a note here from Dr. Bel, he says. —It says you sometimes think you’re an animal?

—That’s ’cause Dr. Bel don’t like to listen. She hears something and assumes.

—But do you know what she’s talking about?

—Probably I told her we all animals. Born like every other animal. Only we think. And thinking makes us know things, things like how we gone die. Then we know we gone die, and we know ain’t no one can save us. But then we think and think, and then we think maybe fame or money will make us happy, or we think maybe buying something will make us happy. They tell you all the time buying stuff will make you happy. And then we try that and see it don’t work, and so we think some more. And we think maybe someone can save us. We think love can save us. But then we date and fall in love and we think some more, and but then it don’t even matter because we know whoever we with is a walking corpse don’t know he’s dead yet, she says. —And Dr. Bel probably wrote that note that time I said I wish I was an animal, an animal not cursed to think, to know everything is dead or dying.

For some reason, saying this and thinking this reminds Sarah of the time she was riding her bicycle—this was back when she was still a kid—and she hit the curb and her front wheel turned and she fell into the street and skinned her palms and knees. She remembers the sting, how much it hurt. And she remembers sitting on the street near the curb, the bike lying half on her and half on the street. And she remembers crying and looking around, hoping somehow that her mom heard her and was running to save her, to pick her up and kiss her wounds and tell her everything would be all right. But her mom didn’t hear her. Her mom didn’t come to save her. And so she limped home, crying.

Blood flowed from her hands and knees, and everything hurt when she walked. And she cried. She cried. And she cried harder and louder when she stepped into her house, like probably because she wanted her mom to hear her, to know she was hurt. And so she limped into the kitchen and into the bathroom. But she couldn’t find her mom. And so she limped into the living room and into her mom’s bedroom. And she stopped crying. Something made her stop crying. Like someone somewhere flipped a switch inside her head that made her stop crying. And she stopped crying because she saw her mom hanging on the closet door, a belt wrapped around her neck. Her face was purple and her eyes bulged, like they was ready to pop.

—Sarah, the doctor says. —What’re you thinking about? Right now?

The clock on the wall ticks, ticks. Sarah drags her eyes to the clock and watches the second hand bounce, bounce. Then she thinks about her mom, hanging there. And she thinks about the note, that note stuck with a safety pin to her mom’s shirt. She remembers what it said, word for word: Everyone is dead and I’m dying and I don’t want to keep dying. So I’m going to die once and for all and just get it over with. I love you, my darling. Be good and do good. I love you.

—Sarah? The clock ticks, ticks. — Ms. Poe?

Sarah watches it, the clock. She focuses her attention on it. Everything is dead and dying, and the clock will die, too. Any minute now. Any minute the clock will stop and everything will stop being gray, and everyone will stop dying and simply die. Any minute now everything will end and she won’t have to think. Any minute now she’ll be just another animal drops dead and stops thinking. Any minute now. Any minute. The clock ticks, ticks.

0 notes

Text

Autoportrait d'un Pataphysicien

by D. Dickey

Beyond the shade of black twice removed from surrounding shades

Through a funnel of vortices too dark to observe

A shape emerges: an oval the color of seared meat

It hovers beneath a chunk of flesh from which protuberances writhe,

All five curl inward and latch onto the oval

To view the darkness, to pay attention to it, to perceive it

Confounds the rudest cynic

Beauty emerges

The absence of light calls attention to itself only as a

Contrast to muted particles and waves flowing into it

This darkness is tainted, however:

Although it feels authentic, it isn’t a glimpse into the gaps in the universe;

Instead, it’s an emulation, the convergence of different kinds of frequency

Ahead of the darkness, the chunk of flesh merges with cylinders of meat

Deformed to mimic two thirds of a triangle

Then they pour downward, a torrent of flesh dripping into the darkness

When taken together, the blob, hollow yet sentient, commands

Your attention—then betrays it as flesh resembling a face melts and

Droops downward

The eyes, hollow and empty, shift in a gradient from gray to black,

Haunting in their vacancy

Agape, the mouth deforms into a wormhole devouring the anxiety

Of existence,

The expression of which bubbles out of the darkness and latches

Onto a brush

Held by an amorphous blob fitted in fibers, the brush sways in

Arches as it translates the hollowness of boredom and loneliness

Into a shade of black twice removed from surrounding shades

0 notes

Text

Manufactured Lament

by D. Dickey

For a brief moment, no longer than ten years, which wasn’t too long, all things considered, the city seemed on the verge of greatness. Nestled at the mouth of Lake Michigan, it had served as a portal for steel manufacturers to transport their goods to and from Gary and Chicago, both voracious consumers of raw and processed steel. Houses bloomed in fields until no fields remained. Streets and sidewalks, buildings and stores and factories filled the city. The leaders of industry diversified, and soon a Pullman boxcar manufacturer popped up. By the lake, a cough lozenge manufacturer erected a simple, box-shaped building. The city boomed, as people would say. Incomes increased, and along with it the accoutrements concomitant to disposable income: pools and swings and cars, some excessively luxurious, and general stores packed with disposable goods, all of which people devoured, people looking to fill their lives with evidence of their squandered time. Then voodoo economics and global trade deals crushed the steel industry, and the port withered and died. Chasing jobs, people fled. Poverty replaced prosperity. Drugs and alcoholism, crime and violence, anxiety and depression and suicide scarred the faces and fattened the bodies of everyone left to rot in the city. Paint on buildings and signs and fences chipped and faded, and concrete cracked and broke. Gray replaced color. The world seemed to dim. Every once in a while, sometimes twice a month, the sky over the city cracked: blood and sulfuric effluvia drenched the city. The poor bastards buried in the bottom-most levels of the social strata, left to rot when the wealth of the middle class fled, watched as the faces of their friends and loved ones drooped. No one understood the affliction. Doctors hypothesized neurological disorders possibly caused by an ecosystem poisoned by decades of industry, but they nixed the neurological argument when faces melted and slid off and merged with the flesh on chests or necks or stomachs or arms. Something else was clearly at work. That no one seemed to notice or care, that doctors only treated it with anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medication didn’t evoke questions from anyone passing through the city. Most people, those with money who passed through town, dismissed the affliction as a problem relegated to the impoverished. In some way, people argued, it was probably their fault—maybe not directly; perhaps it was the product of poor upbringing, or genetics. At any rate, people said, there wasn’t much use in worrying. ‘My life’s good,’ one traveler said, ‘my face’s intact; why should I worry?’ The old woman, who lived in the abandoned post office, known to everyone in town as a ‘crazy witch,’ laughed when she overheard the traveler’s apathy. ‘The way things are going,’ she said, ‘the sky over every city will crack, and every face will soon droop and melt.’ The traveler ignored her. Everyone ignored her. And when the sky over cities around the country–around the world, even–cracked and bled, and faces drooped and melted, entire populations ignored the problem, pretended it didn’t exist, by focusing on alcohol, drugs, sports, and pop culture. ‘I mean, really, there’s nothing to worry about,’ a local community organizer said. He was a prominent billionaire, face intact, who lived in a neighborhood enclosed in a dome and often acted as the voice of the people. ‘This is something that happens,’ he said. ‘It’s important now, it’s absolutely critical, that we carry on with our lives. We as citizens must continue shopping, go on vacation, go to college, accumulate as much debt as is needed to help our struggling economy. Faces change. Yes, some even melt. But it must not prevent us from living our lives, from raising our children, from playing our part in maintaining the economy.’ Footage of his speech played on repeat on news broadcasts around the country. Few people expressed alarm when his cheek twitched and his eyelid sagged mid-way through the speech. Sometime later, he retired from public view.

0 notes

Text

I’m a huge fan of Goldsworthy and so I’m re-reading this, which is, I think, a spectacular biography. Show me what you’re currently reading.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This was sorely needed.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every September, Clara’s sister returned from the grave for three weeks to perform Albinoni’s Adagio in G. She played it on a cello only half-remembered, and therefore woefully unable to stay in tune. It often sounded as if she were shaking a bobcat, but her sister feigned delight.

#art#artwork#aiartist#nft#contemporaryart#nftcommunity#nftmagazine#artists on tumblr#dark art#digital art#nftart

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The phenomenology of spaces pointed consciousness away from itself and into a world of matter and meat, a world where the “I” vanished in a quiet, unreflective gaze. The meat of existence bled into the world and catered to the whims of what Joyce called “the ineluctable modality of the visible.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

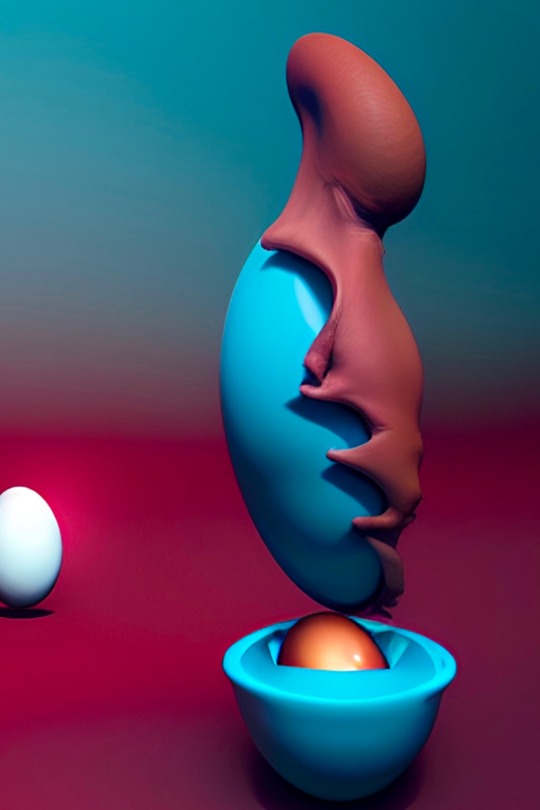

Eggs lobotomize sensations coursing through the gaps between grains of sand as they filter through an hourglass. Silence. The fractals of space coalesce and collide, and in the concussive waves of their collisions eggs tumble out.

Why eggs?

They are particles of transformation.

Phenomenology of Eggs

Being an exploration of the phenomenology of eggs as representative for the entirety of the human condition.

A series limited to 50 1/1s

https://objkt.com/collection/KT1BBkfumnAEN83yintHChff5uinpNLupZN7

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“REGENESIS,” ACQUIRED ON THE SUPERRARE.COM CRYPTOART / NFT PLATFORM FOR 4 ETH ($5.5K) BY COLLECTOR VINCENT VAN DOUGH.

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

To what end does she offer herself to the universe? The meat of her desires corresponds to the spirit of her awakening, and her transformation, although incomplete, tips her toward happiness. She had longed for something else, to be someone else. Now, on her way to becoming another, she sheds her previous existence as she offers herself to the universe.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Ludwig Wittgenstein articulated a straightforward ontology: the world is all that is the case. Possible states of affairs can either be the case of not be the case. Reality is the totality of states of affairs that are the case.

Language is a logical function that pictures states of affairs. We can assign truth values to these propositions. True propositions reflect states of affairs that are the case, the totality of which reflect reality.

But language can only reflect the logical structure of concrete concepts—as opposed to concepts that can or should only be shown. This assertion limits philosophical discourse, which was Wittgenstein’s intention.

Taking up on Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy, Wittgenstein argued that philosophers too often misunderstood language itself; therefore, they undertook discourses in which few found agreement, and many intellectual chasms opened, because philosophers embarked on inquiries dealing with concepts that language couldn’t adequately picture.

Some concepts can only be shown, not discussed. “Whereof one can not speak, thereof one must remain silent,” he famously argued. And now that pretty much everyone quit reading this, tell me how’ve you been.

1 note

·

View note

Text

An old video, found inside a decayed fireplace, preserved the only known image of the Demon Queen—in little more than a still from her wedding. Legend tells us the sky darkened as she uttered the phrase “I do.” When she died, her son ordered all images of her destroyed.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! Tell me about yourself.

0 notes

Text

A self portrait from the wondermundo inner world. She’s flawed, but she doesn’t hide anymore. She finally sees the beauty in her that others told her was always there.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflections and Revelries

5 notes

·

View notes