Derby's Silk Mill is the site of the world's first factory and has undergone a ten-year multi-million pound programme to create a inspirational and active Museum of Making - locally designed and delivered; globally significant. The Museum of Making has been co-produced with our communities, inspiring future generations of makers, creators and innovators.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

We Backyard Foundry

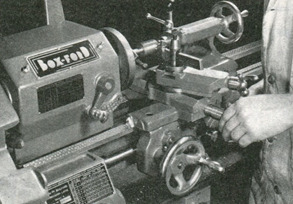

August, Tuesday, 23rd, 2022 the Museum of Making workshop team travelled to Artisan Foundry, Liverpool for a one-day course in greensand foundry practice, patternmaking and casting.

The course was taken by Art, an experienced foundry trainer and practitioner. The comprehensive course taught everything from sand moisture content and pre-moulding preparation, setting new and old patterns for moulding, ramming sand techniques, correct mould venting, sprue cutting, chemical additions to metal, heating and pouring hot aluminium and other metals such as bronze and gun metal.

Undertaking the course was preparation for commissioning the Museum of Making workshop crucible -- the final piece of equipment to be brought to life in the newly-opened museum workshop space. Post course, with the critical H&S and casting PPE regimes poured into our minds (aluminium melts at extremely high temperature) - the workshop is preparing to design courses and demonstrations in patternmaking, greensand moulding and metal casting.

Below is a selection of images in a quasi non-linear order featuring Steve, Arthur, Andy, and, of course, the mighty Art.

The green foundry student checking the ‘greensand’ which isn’t green but red. Green denotes it is damp and sticky with natural moisture and clay. Art left, Andy right.

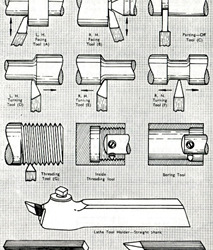

A chicken doorstop casting repurposed as a ready-made pattern, moulded to make another slightly smaller chicken doorstop in aluminium - (all cast metal shrinks after casting, aluminium about 1mm for every 70mm 1/70 -- patternmakers use special calibrated ‘expanded’ contraction rules). Using the casting from an original pattern as the next pattern and then that cooled casting as the next pattern the chicken casting would, of course, eventually stop being there. Don’t copy copies then.

Art also runs a day course in lost wax casting. Lost wax casting as everyone knows is the oldest industrial casting process known to man. As a workshop, we will at some point be lost wax casting.

The Museum of Making is the keeper of hundreds of cast metal plaques, mostly railway related, which carry information in the form of cast text. With a crucible in workshop and the greensand training in place we intend to run courses wherein makers can create their own word signs using handmade or off-the-shelf white-metal or plastic letters, 3D text simply applied to a flat backboard.

Art is here applying a parting powder to a metal ingot pattern. A bit like talcum powder, it is kept in a traditional permeable muslin ‘pounce bag’ and the trick is to dust the pattern as if with icing sugar evenly. Parting powder stops the wet greensand sticking to the pattern and the mould sand tearing when the pattern is withdrawn after ramming. the sharpie circles denote where we are to cut riser and runner system.

We decided to cast a sign for Museum of Making workshop. The aluminium plaque pattern in the picture is ready-made and different sized letters and fonts and logos can be placed on the pattern to make varying bespoke castings. Bit Jamie Reid meets Fawlty Towers going on at this stage. The letters and logo are attached using Copydex latex glue which holds objects in place for moulding but can be pinged off - and glue residue piggled off - to clean up base pattern and let letters be used again.

Parting Powder mist

Art closing the two parts of a mould - known as ‘cope’ and ‘drag’. Cope is the upper box and has locating pins, drag the lower with accepting negative dowel holes or ‘eyes’. A mnemonic to use the moulding boxes in correct sequence is “eyes down”. You can see the down sprue and riser cut into the cope like two eyes in a strange Bruno Munari abstract face design. (Design as Art, Bruno Mari, 1966)

From this image you can see that the the ingot pattern is placed in the drag first, which is common. The pattern has no core box and is known as a shell pattern. The pattern makes its own cores which are extensions of the sand rammed up in the cope after the drag has been processed and turned over for the second-stage of sand moulding process. This ingot piece is also a good example of a ‘flat back pattern’, i.e., the pattern is placed flat on its back on a moulding board before sand is rammed (compacted) around it. * For a fuller description of different types of pattern equipment see Patternmaking Explained to Children - Steve Smith Museum of Making Tumblr).

Once a mould is completed and ‘closed up’ on its pins - and pattern of course withdrawn - the paired boxes are set on the floor ready for casting in the hot metal needed to make the required casting: iron, bronze, gunmetal or aluminium. The sprue and riser holes are then covered to prevent debris entering the mould before casting - usually a piece of wood is used. The ‘sprue’ is where the metal is poured in and the riser is usually diametrically opposite the pouring gate. The riser is there because the air within sealed mould must escape pushed out by the incoming stream of metal from the runner -- the riser also acts as a reservoir of metal and heat to feed the shrinking casting. When metal appears running up the riser to the top of the cope box the furnace pouring person realises the mould is full of hot metal and desists feeding the mould.

Art pointing out the particular sections of a ramming ‘dolly’. The tapered wedged section nearest to our instructor is designed to get into the tight corners a multiform pattern will present, the opposite flatter end - more mallet-like - is for when the pattern has been fully embedded in compacted sand and the rest of the void of the box is filled with backing greensand which provides the supporting structure of the fragile mould. Making these dollies in-house is easy and looks a good coproduction learning opportunity (how-to-turn-between-centres) for a Museum of Making volunteer. You Know who you are...

Greensand has to have just the right moisture and natural clay content to make it mouldable -- not too dense. thick sticky sand can prevent dangerous high-temperature chemical gases permeating through mould in the red-hot casting process. Here Art started to explain the properties the sand should have by demonstrating ‘by hand’ and in practice how right-damp sand should feel and behave under compression. At Ilkeston College, as apprentice patternmakers, we had to also complete City &Guilds Foundry Technology and Metallurgy examinations and empirical practice in college micro-foundry was essential. We used a closed flask - a bit like a cocktail shaker with a dial attached - to measure the moisture and chemical contents of greensand. If sand is too wet there can be gas-driven (steam powered) explosions - very dangerous - too dry and sand is friable, and casting will be a ‘scrapper-shitter’ filled with unwanted washed sand (inclusions) from decomposed mould.

Early stages of moulding: taking sand from Artisan Foundry under-bench greensand storage bin. The bin has a lid and a plastic membrane to retain moisture and keep out contaminating materials. Andy is here taking sand from the bin to start filling his wooden moulding box, the frame you can see on bench placed around the ‘Chicken Doorstop’ pattern. A sieve can be used to sift the sand that ‘faces’ against the pattern or - as here - you simply rub the sand through the palms of the hands feeling carefully to eradicate lumps and spot unwanted stones, even old cast metal amongst the essential fined-out stock material. Arthur has made a hybrid sand and moulding bench crossing Art’s bin with a foundry station he saw when a Derbyshire school D&T Technician for our workshop.

The WORKSHOP pattern is nested in the drag -’eyes down’ box - after ramming with wood dolly on moulding bench top. The welded metal moulding box has been carefully turned over and, before the cope box is located and the cope rammed to make the second section of the complete mould, excess parting powder applied to back of pattern and joint sand is removed with a pair of traditional bellows. This historical-but-still-used old-school air-making device is held away from box to avoid blasting the fragile sand with over-compressed air.

Art coached the Museum of Making team throughout our training visit to Artisan Foundry. Passing on relentless tips and dodges (’hacks’) - learnt through his own empirical practice as a jobbing foundry man and educator - in his thick scouse accent Art passed on priceless knowledge. The background has Arthur ‘sleeking off’ the top of the cope box with a moulders trowel. The next step is to then split the completed mould, withdraw the pattern and cut pouring sprues and risers, as well as vent the cope-section sand where necessary.

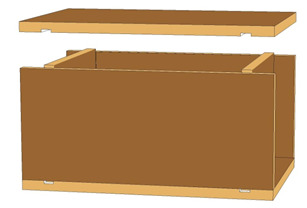

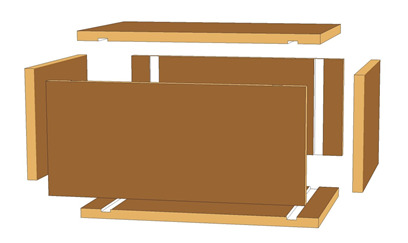

Small scale moulding boxes - in the sub-culture of the maverick ‘Background Foundry’ - can be made from simple homemade square section softwood. Not ideal foundry material, in all-ways, as the hot aluminium or (especially) iron can easily set alight the timber box; spot the combusted charred areas on the DIY ‘flasks’ in these images. To avoid this dramatic, though hazardous, outcome post moulding and before casting these boxes can be stripped from the sand blocks before pouring. Look closely and you can see the ‘loose-pinned’ butt hinges. Withdrawal of the thin wire pin ‘hand-grenade’ style releases the knuckle of the hinge and the box can be opened out away from sand. The box-less cope and drag can be reassembled - closed up as if with traditional moulding boxes - and the metal cast into what is termed in foundry jargon a ‘flaskless’ mould stack.

I trained at Stanton and Staveley Ironworks in Derbyshire 1977-1981. As part of our industrial education, we were exposed to the ‘real-life’ of Erewash Foundry. If you have never been inside a dark industrial dirty hot and dangerous foundry, it can seem like a kind of hell-on-earth scene. I recall monster bogeys of hot glowing spitting iron whizzing around the foundry (high in the air suspended from overhead moving cranes) glowing orange against the dark interior of the black sand-dirty foundry. In the late seventies none of the iron casting men or moulders - iron melts at 1200 degree centigrade - were equipped or supplied with regulation protective gear, except perhaps loose moulding boots which had a quick release fastening to allow leather ankle boots to be kicked off when spitted-out dangerous metal splashed inside the shoes and would burn through skin and bone until it came through the bottom of the foundry workers’ foot. Rather than wear thick fire-resistant smocks or leather aprons - as Andy is wearing here - hard Ilkeston men simply sported layers of thick wool jumpers which hopefully slowed down and cooled the ever-present flying spots of molten iron that peppered those pouring iron from oversized industrial ladles into equally oversized industrial-scale sand moulds before they hit skin. PPE advice was a topic Art majored on.

In the spirit of DIY renegade Backyard Foundrydom, Art had improvised a blast furnace from what looked like an old stainless steel camper-van oven and some square refractory bricks. The metal is heated by a propane-gas-bottle generated -flame through a hole in the contrived cupola to play on the small melt-crucible into which the raw aluminium has been placed. In this image Art is plunging a ‘de-gassing’ agent into the red-hot non-ferrous metal to chemically purify molten material before casting. A small section of a broken-up 50mm x 20mm round tablet (about the size of a walnut) is forced to the bottom of the hot melting metal until dissolved. The resulting dross (slag) is then skimmed of the surface of liquidised aluminium.

Empty moulding box awaiting pattern. In fact the dowel locating pins at the end of the fabricated-steel box indicate that this is the ‘cope’ top box. The cope pins are dropped through the receiving accurately-machined hardened-steel bushes on the base ‘drag’ box of the two-part mould which has already been rammed up with pattern in situ. Because the drag has no protruding pins the metal container which holds the green sand can be placed around the pattern on the same flat ramming board. As Art pointed out, and I pointed out above, a good aid to remembering that the drag is rammed-up first is the bingo catchphrase “eyes down”.

Here you can see the metal ‘shell pattern’ of the ingot mould bedded (post-ramming) in the drag which has been turned over ready to take the cope box and then filled with greensand compacted with the dolly so completing the two-part mould. The pattern is again dusted with parting powder as is the sand mould joint to avoid sand adherence to either surface. Facing sand is riddled onto the pattern for a finer cast finish before un-riddled sand is used to build up the back of the mould.

Sand is kept in a plastic bin covered with polythene and a tight-fitting lid to help sand remain damp and so clay-sticky for successful mould-making. Note the chalk X-X marks on both boxes. This is done to ensure mould is reassembled - post-pattern withdrawal, and pre-casting re-closing of mould - in correct position, i.e. closed in the same end-to-end ‘handed’ relation as the boxes were when rammed up.

Parting dust, like scotch mist, rising from earthy mould. (It takes your breath away.) Pretty sure in the heyday of Foundry life and Northern Soul ( early-mid1970s) them lad dancers - many of whom would’ve worked in Midland foundries-would have filched parting powder from work to save on the more infamous talcum powder sprinkled on floors of soul all-dayers and all-nighters. Art where you a Casino-Soul Star?

Andy drives the Dolly into the un-sieved greensand to ram up the cope section of mould, taking care to make sure sand is evenly rammed - but not over-rammed since over-compaction of sand leaves fewer micro apertures for hot gases and steam to rise through greensand created by hot metal poured into closed mould - Iron, Aluminium, Bronze, gun metal etcetera. (To allow gases to escape - which can blow cope and drag apart in large moulds - floor hand-moulders used/use a fine sharp rod of about 1.5mm diameter to pepper the sand above the pattern (but not hit the pattern) with vent channels. Art showed us this process using his pinched fingers holding the venting spike as a depth stop to create deep vents, but vents stopping above mould surface.

Cope and drag boxes rammed successfully, the boxes are split, pattern ‘rapped’ and lifted carefully from fragile surrounding sand revealing requisite negative impression of positive pattern into which hot molten metal will run after reclosing boxes.

Because this ingot mould is a two part mould in which the ‘cods’ or ‘cores’ which form the metal troughs of the finished ingot casting are ‘self left’ and so would ‘hang down’ if the standard Drag and Cope order had been followed, experienced Art inverted the order and so the cods are raised up from the sand by making the rammed up cope the drag. As in all forms of making there are general rules but no unbreakable ones. In making the cods stand or sit up in the mould this avoids potential situation in which unsupported cods would be suspended - merely held together and to the backing sand by moisture and sticky clay - and as such could snap off when inverted pre-casting. In Art’s right hand can be seen a short section of hollow metal pipe (Ikea wardrobe rail) he has just used, as can be seen in right aperture of mould, to bore a runner hole through the rammed sand to the top of the (upside down) cope. Hot metal will be poured (cast) through the runner - metal running downwards with gravitational forces - into the negative empty cavity of the pattern-formed ingot mould ready to shape liquid plastic metal.

Art boring out the riser through which the metal and air are expelled under diametric pressure from runner and elevated poring basin.

The runner we are to pour the metal down is approximately 20mm in diameter and exits the mould through the top of cope and is connected to underside of finished ingot casting. However, it is difficult to aim the viscous heated aluminium into such a constricted channel from an often cumbersome pouring flask. To aid filling the mould with metal and avoid hot aluminium running free and dangerously over the top of the glassy flat cope sand, down the side of the moulding box, onto the floor, potentially splashing casting-person’s boots - a pouring basin is made up with a wider tapering channel through which the hot metal can enter the narrow runner. The extra height also gives favourable downwards header pressure - like a water tank in a loft - to drive the immediately -cooling-now-unheated metal ‘faster’ into the mould and up the riser. This is often called a basin. The top reservoir of hot metal also aids the shrinkage of the casting. As the aluminium or iron cools down it dimensionally contracts, as I said. As it contracts against the cool sand of the damp mould it needs to be ‘fed’ with molten material. The basin then acts as a surplus tank supplying the hot-thirsty nascent casting with the metal feed it requires. Many larger castings require internal ‘feeders’ which are made to prevent shrinkage in a casting, which means a cast object becomes a failure or ‘scrapper’. As a first-year apprentice I was made to make feeder patterns for the first six months of my training as a patternmaker.

In the maverick spirit of the Back-yard Founder, Art has used an old pineapple ring tin as a flask for his pouring basin; the sprue cutters were crafted from truncated chrome Ikea wardrobe hanging rails.

Casting or moulding boxes don’t have to be heavy metal. This small flask has a removable pin and so the wood frame can be deconstructed and removed from sand mould leaving a ‘flask-less’ block of green or core sand that hot metal can be poured into. Working this way a backyard foundry can make multiple small moulds - and thus cast artefacts - from a single pattern and moulding box in readiness for a serial pouring and crucible firing. The box is clearly made from some simple stock softwood and hinges buyable from a DIY store but painted with red pattern varnish to avoid deterioration from wet sand.

Art and Artisan cast in a variety of materials. Plaster kept out back of workshop.

Small flask used in shrinking casting chicken doorstop with articulated flask.

Artisan foundry shop sells aluminium and bronze ingots for backyard casting community and homemade DIY foundry punks. We have spoken in workshop about the potential clever buzz around running short casting courses at Museum of Making wherein attendees bring in their own used beer cans. Post-weekend binge, smelt the used-up Brew Dog and Special Brew aluminium tins into interesting new products: chicken doorstops, nameplates or other unimagined contemporary material wants. Art cautioned against this: ‘Paint’s toxic lad’, ‘poor quality ally to be fair lads’, ‘you don’t want sticky booze-smelly ally cans hanging around a workshop do yer lad’. In the above photograph the- casting newly-knocked-out-of-steaming-hot-sand-mould is a casting poured into the mould taken from the ingot mould Art uses to cast sellable ingots, used as a pattern. Thus on the day we cast our own ingot mould for Museum of Making workshop for casting ingot bars. The ingot mould was cast from reclaimed aluminium core-wire that is used in high voltage electricity cables -- so you can use recycled ‘found’ metal. A casting course offering potential neo-backyard founders to make their own ingot mould might not grab audience. But if I modify physically the form of the ingot pattern to make a partitioned ingot-like casting and reconfigure (recast) it descriptively as a object into a pistachio-Bombay-mix-Italian caper-kimchi presentation receptacle for table top appetisers, things sound more appetising. As the Italian saying ‘L’appetito vien mangiando’ wisely advocates ‘with eating comes appetite’. I also think casting a small aluminium pie dish has potential. The silvery stems you see poking from the sand are the runner and riser connected to pouring basin.

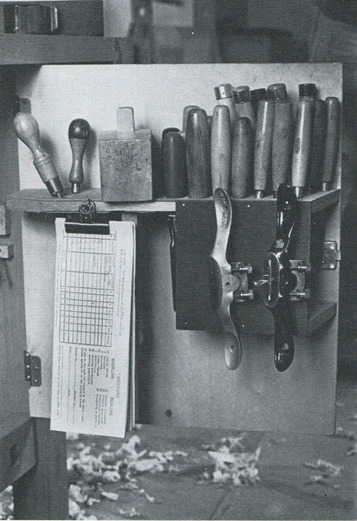

Various tools and casting ladles needed for backyard foundries. Make your own kit if you can

Steve Smith

Workshop-Studio Manager

Museum of Making

February 2023

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

h**k this and h**k that…”: Art(i)factualism, Detournement, Belper Punks, and DIY Making (1719 -2022)

Anything can be used -- Situationist Maxim

The two fundamental laws of detournement are the loss of importance of each detourned autonomous element – which may go so far as to lose its original sense completely – and at the same time the organisation of another meaningful ensemble that confers on each element its new scope and effect. SI Communique 1957

Even writing 50 pages of crap can give a sense of achievement. DBC Pierre Guardian 2017

Dovedale Crescent, Belper, Derbyshire, e-1970s:

A modern housing estate of near-identical detached houses: bungalows, two and three-bedroom dwellings constructed in the early 60s – man-made (unimaginatively) from red orange brick – individual constructions facing snaking black tarmac forming distinctive interconnected roads, streets, nooks, crescents, avenues and closes. Classified by their idiosyncratic banal pastoral signifiers like ‘Beaurepaire’, ‘Millersdale’, ‘Lowlands’ ‘Ladywood’ and ‘Dovedale’ – these were surely ironic places to live since the new-built estate was a brutal imposition of bricks-absurd covering over the once-green fields. A new estate, hacked out of the benign land of rolling hills of Belper because farms, fields, woods, leas, dells, hollows, natural beauty spots, and wildflower meadows were here before the houses and their inhabitants came. 2 Dovedale Crescent Wally Cant – Pit Deputy; 4 Dovedale Crescent Bob Smith - Coal-face worker; 6 Dovedale Crescent Alec Laws - Shot blaster; 25 Dovedale Crescent (facing Alec Laws) ‘big’ John Marshall – coal face worker; 21 Dovedale Crescent (facing Wally Cant) Jimmy Bell - pit worker; 23 Dovedale Crescent a man of unknown occupation and provenance who wore a deerstalker, tweeds, grubby shirt and regimental military tie, thick corduroy britches and thick leather-soled plain shoes, a fellow who, to all intents and purposes, looked like an old English estate owner and looked down on the NCB deferent families who surrounded his Englishman’s castle, with class difference. How he got here nobody knew. Oh, on his face he wore steel-framed bank-manager glasses and sported an ex-RAF handlebar moustache; in socio-cultural terms, then he was a hu-man manmade archetype existentially homological to semiotic-ally important inorganic manufactured objects like the 20th century designer angle-poise desk lamp or a Bahausian architect-designed bent tubular metal and leather chair.

A group of late-teenage boys sit talking on the wooden six-barred gate guarding the entrance to common scrubland known as the back-field. Like the gang of vultures in Disney cartoon film of Rudyard Kipling’s story called The Jungle Book (bored flock birds perched on the thick branch discussing what to do “I don’t know…what do you want to do”? ordinary lads from the estate lads - birds of a feather - were discussing what fashions were now passing and emerging on the local scene in terms of youth wear and companion hairstyles. As they talked together about flash clothes they stared blankly at the essential electric company substation on the opposite side of the road.

Mop-top Vultures, Jungle Book, Walt Disney, 1967

Youth, emerging from the mod(ernist) culture of the late sixties was transitioning-transposing-morphing with velocity into suedeheads via skinheads. The transformation was subtle but sure of itself in style. # 5 clipper blade all over from now-on-in for getting the new suede-head felt-smooth smart combed look, i.e. grown out skinhead #1. Navy-blue wool Crombie coats were still in; nowadays with funereal ‘suede’ collars, red handkerchiefs in top pocket pinned with a new DCFC club badge the size of a tanner gave the look a local tribal sense. Button-down cotton shirts were printed with beautiful checked and colourful designs, manufactured by either Brutus or Ben Sherman. Trousers were smart -- blue or green two-tone ‘Stapress’. A uber suedehead – like the cool Steve Ottowell (Lowlands Road) - now even carried a gentleman’s umbrella. The classic black umbrella replaced the army-surplus green mod parka as protection against the weather. The metal tips sharpened by the suedehead; (converted) reground for fighting on the grinder-wheel at work. Suedeheads were very creative and modified stainless steel combs too. The long tapering handle reformed into a stiletto blade at work on the same workshop grinding wheel trans-formed into a dual tool for doing your hair right or wrong and harm. [1] Working-class youth then – blue-collar apprentices serving the demands of Derby-based industrialism - were reworking the city-gent look – a legacy from the bowler hats worn in the violent (awful) film Clockwork Orange; revising the populist anti-hippy proletarian skinhead fashion. Contra the skinhead and his/her hard-worker look, Suedehead chic parodied or copied the hard-core white-collar post-shopfloor office worker: ‘all of a sudden stepping out wearing a bowler hat…Suedehead represented a more tailored approach to the skinhead aesthetic with velvet-collared Crombie, houndstooth checked suits and brogues’. [2]

Brogues were highly-polished black leather shoes, and handmade by Loake, Grenson or Gibson. Patterned with geometric indentations and raised leather ornamentation this traditional footwear spoke out for the English past. [3] The hard-soled shoes were worn with thin wool blood-red ankle socks which contrasted mysteriously with the dark surrounding serious formal trousers and black shining leather clothing worn against the slack ethnic swinging sixties. [4]

[1] See blog Hegel’s Trowel and Elaine Scarry’s distinction between tools and weapons. The suedehead comb was a tool for personal aesthetic use, styling hair, sharpened for inflicting pain, a weapon: suedehead was a dark cult…P173

[2] Andrew Stevens, Introduction to Suedehead, 2015

[3] In The Wheelwrights Shop (1923) the author Georg Sturt recounts how one of the master blacksmiths he admired marked with dot punch and file a simple geometric pattern, a mysterious enigmatic design ‘come down from some far-off generation’. Sturt called it ‘a simple and ancient decoration. A design very like it (it could hardly be less ornate) may often be seen stamped in leather across the toes of a pair of boots, where likewise it may be of a prehistoric date’.

[4] The Language of Things (2009) is a book by Deyan Sudjic. A design historian and commentator on the attraction to modern objects and how they communicate subconscious and conscious meanings to consumers notes that there is a whole family of objects and artefacts that juxtapose red details against black backgrounds from the VW golf GTI to the cult Tizio angle poise light. In all cases they connote argues the critic ‘a faint air of suppressed violence’ in that their original model was the red dot safety catch on the Walther PKK gun. I recently plagiarised (incorporated-subverted this series by including this red-dot-on-black-ground detail on a loom I have made for the Museum of Making. See Detournement and Adam Blenkoe below Weaponising Weaving...?

At the end of the day, then, these lads took off their blue-collar steel-toe-capped workshop boots and slipped into their newly-acquired brogues. Not content though with the shoes as they were, they paid a King-Street cobbler to adorn their new leather outsider/insider brogues with Blakey metal ‘segs’. Function-wise, nailed into the soft natural leather undersole of this expensive footwear, the metal tips let into heels and toe sections were crafty customisations – pragmatic additions - to prevent the wearer wearing out the vulnerable animal hide when walking about on tarmac across town; aesthetically segs were sonically transformational making a great CLICK CLACK CLICK CLACK noise on English pavements. The 1970 streets rang with the alarming sound of footwear made musical instrument, and remade walking a violent performance. Amplification of the latest youth culture.

Respected New-Left man Raymond Williams (1921-1988) - the Welsh intellectual at the forefront of the developmental trajectory of what became both lauded (and derided) as Cultural Studies - in his well-known books Keywords and Resources of Hope mentions that there are only two other words in the English language that rhyme with Culture.

1) Sepulture – burial, grave or tomb

2) Vulture – bird of prey that scavenges on carrion.

Hence Culture-Vulture [5]

Despite his apparent radical stance that culture is universal, democratic, classless and for everyone - a thesis developed in his essay ‘Culture is Ordinary’ – he worries that what he identifies as new ‘flip words’ such as “culture-vulture” are malign phrasal attacks against any attachment to learning or the arts -- a stabbing verbal assault on what he would call ‘high-culture’ wounding what he wants to say the word ‘Culture’ stands for. Moreover, worried for high culture, he was surprised that, as the late 60s collapsed and 70s progressed, ‘we don’t yet call museums or art galleries or even universities culture-sepultures’, i.e. dead burial places. For Williams, writing back in the 1950s, milk bars and teddy boys upset the Marxist Williams as valueless bubble-gum mindless ‘low-popular’ culture and kickstarted the serialisation of youth cults: Teddy Boy, Rocker, Mod, Skinhead, Suedehead, neoTeds and then the Punks. To be fair, Williams politically-motivated writing translates a second alternative meaning of the ‘complex’ word ‘culture’ a word sign Williams would say had as its other signified a particular or common ‘way of life’. Yet, still, Ray said the working classes needed saving by equal access to big culture in the form of ‘the arts’: literature, classical music, and top Universities. The cultural problem I had was getting my hands not on Ulysses, Prokofiev or a sporting chance to join Williams at Cambridge, but on the sublime de-culture objects: Gibson-Black-Leather-Brogues. Us Dovedale Crescent lads were culture vultures only hungry for the low-level youth culture meat Williams’ academic elite Marxism had no appetite for. Red socks were easy to acquire. Barbara Blount was a market trader who lived a few houses up from us round the corner in a bigger identical non-identical house. She bought-up ‘seconds-socks’ from a hosiery factory on Spencer Road – Blounts -- and repaired unwanted socks or tights quality-controllers rejected. Repaired, the Blount family sold the saved stock from a bleak cold Ripley Market Place; or from the back of their modern brick garage store. She sold scrap socks to the estate; cheap and fair. Via Barbara I got into my first red-socks, i.e. small signs of self/group expression showing off the way-of-life I wanted to be part of. The shirts favoured by suedehead - Brutus and Ben Sherman - were also cultish objects of material fashion. Out of my reach until finally getting a knocked-down gorgeous sky-blue checked Brutus (life saved again by Barbara Blount) -- I had to imagine/fantasise the dead-man check shirts I found (picked over) at diabetic jumble sales me mam ran were the real thing. Fool’s gold or creative thinking? Whatever, I used the same stubborn suspension of disbelief in my quest to walk in the same shoes as those big youth-culture vultures sat on that three-bar gate. For no matter what them damned Gibson brogues were dead expensive. Down in Belper on the High Street – near the cobblers - was the Army and Navy Stores.[6] In the shop window were some lookalike brogue-esque black shoes with decorative indentations and raised leather applique. They caught my eye. The laces were black and red chevrons but these could be easily swapped out for thin leather laces. They were called Toppos and a lot of us younger lads adopted them in place of – or until – brogues could be got.[7] But like the umbrella and steel comb, they needed adaptation. Blakeys were expensive, and I don’t think the thinner rubber soles would have taken the heavy metal masculine accoutrement so what we did was hammer drawing pins nail-like into heels and toes of the false-brogues to get the metallic clipping sound we wanted to hear. DIY fashioning was a constant presence on our new estate. When mid 70s there was a rock’n’roll revival after Showaddywaddy starred on New Faces and Bill Haley came to play the new brutalist concrete Assembly Rooms in Derby neo-teds at Belper High posed at the youth club in crap paper-thin drape suits bought from the NME back pages in an early manifestation of mail-order consumerism; rag-traders cottoning on to new fads. Now then Barbara Blount started selling illuminous pink, green and orange socks. Surprisingly, since as the son of market-traders he was the first to get to new objects of commercial fashion - and a popular shop in Derby Market Hall sold the real things - my best mate (her son) Simon Blount made himself a Teddy boy bootlace-woggle by deconstructing an unwanted B52 bomber kit from Airfix and using the weapon of war’s pilot to form a passable, but absurd, imitation of the type of neckwear the Teddy boys from Leicester were seen wearing on TOTP. The pilot’s arms were set on a plain back tab and stuck out to resemble cow-horns his visored helmeted head the contrived animal’s skull/head. He left it all white. It had a sort of Greco-Roman classical sculptural style.

Showaddywaddy, circa 1974

[5] Raymond Williams, Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism, (London, Verso, 1989), p 6.

[6] From here, post-suedehead times (after a temporary Ted– revival) – we would buy large navy-blue sailor’s bell-bottom trousers as ‘found’ skinners as Bootboy slowly evolved from suedeheads

[7] A pair of Toppos became an actual well-known (socio-historical) youth-culture object in Belper, recognised as a credible alternative to Grenson brogues. I was talking with Tim Finch in The Grapes pub Belper a few years back. Tim, a life-long youth-culture follower and knowing modish fashion exponent, says they were called Toppos after some kid called Toppo who recognised their stylistic worth and set the phenomenal trend off; in our town at least.

Another guy who eventually came to embrace constructing his own articles of fashion was Robinson Crusoe. Shipwrecked and alone with no skills and experience of making things Daniel Defoe’s gentile everyman of the book of 1719 had to manufacture his own clothes, utensils, baskets, tables, chairs, general estate, and interestingly an umbrella. i.e. Crusoe made himself by necessity a tailor, weaver, potter, carpenter, architect, boat-builder, stonemason, baker, toolmaker and candlestick maker. He got his materials from repurposing and recycling the wrecked ships commodities and materials (especially dead sailor’s clothes) and those of the raw natural world where he found himself a past-passive consumer desperate and thrown into commodity poverty which made him be active. On the island washed up money he had no use for: ‘I smiled to my self at the sight of this money. ”O drug!” said I aloud, “what art thou good for?’

‘And now in managing my household affairs, I found my self wanting in many things, which I thought at first it was impossible for me to make, as indeed as to some of them it was… I began to apply my self to make such necessary as I found I wanted, as particularly a chair and a table; for without these I was not able to enjoy the few comforts I had in the world; I could not write, or eat, or do several things with so much pleasure without a table.

So I went to work; and here I must needs observe, that as reason is the substance and original of the mathematicks, so by stating and squaring every thing by reason, and by making the most rational judgement of things, every man be in time master of every mechanic art. I had never handled a tool in my life, and yet in time, by labour, application and contrivance, I found at last that I wanted nothing but I could have made it, especially if I had had tools; however, I made abundance of things, even without tools, and some with no more tools than an adze and a hatchet, which were perhaps never made that way before, and that with infinite labour…

However, I made me a table and a chair, as I observed above, in the first place, and this I did out of the short pieces of boards that I brought on my raft from the ship… ‘

Elaine Scarry - who I cited on making in Hegel’s Trowel - writes about Defoe’s intent to expose human making as at the heart of autonomous healthy modern enlightenment subjectivity.

Crusoe begins by being a person who “makes” either as a result of acute need (where willed artifice is the only available strategy of self-rescue) or as a result of accident (where artifice entails the human genius of observing a wholly unintended outcome), but increasingly becomes one who wilfully “makes” merely to make. That is, in addition to transforming his external world, Crusoe has transformed the nature of the act of creating itself; he has remade making; he has remade the human maker from one who creates out of pain to one who creates out of sheer pleasure.

Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe, Penguin, 1981

May 1956, some situationist writing somewhere in Europe:

Detournement as Negation and Prelude

Detournement, the reuse of pre-existing artistic elements in a new ensemble, has been a constantly present tendency of the contemporary avant-garde both before and since the establishment of the SI. The two fundamental laws of detournement are the loss of importance of each detourned autonomous element – which may go so far as to lose its original sense completely – and at the same time the organisation of another meaningful ensemble that confers on each element its new scope and effect. Detournement has a peculiar power which obviously stems from the double meaning, from the enrichment of most of the terms by the coexistence within them of their old senses and their new, immediate sense. Detournement is practical because it is easy to use and because of its inexhaustible potential for reuse. Concerning the negligible effort required for detournement, we have already said, “The cheapness of its products is the heavy artillery that breaks through…walls of understanding”. (Methods of Detournement, May 1956)

Detournement has a historical significance. What is it? “Detournement is a game made possible by the capacity of the devaluation” writes Jorn in his study Detourned Painting (May 1959), and he goes on to say that all the elements of the cultural past must be “reinvented” or disappear. Detournement is thus first of all a negation of the value of the previous organisation of expression. It arises and grows increasingly stronger in the historical period of decomposition of artistic expression. But at the same time, the attempts to reuse the “detournable bloc” as material for other ensembles express the search for a vaster construction, a new genre of creation at a higher level. Any elements, no matter where they are taken from, can serve in making new combinations…Anything can be used. Situationist International Anthology, Edited translated Ken Knabb, 1981)

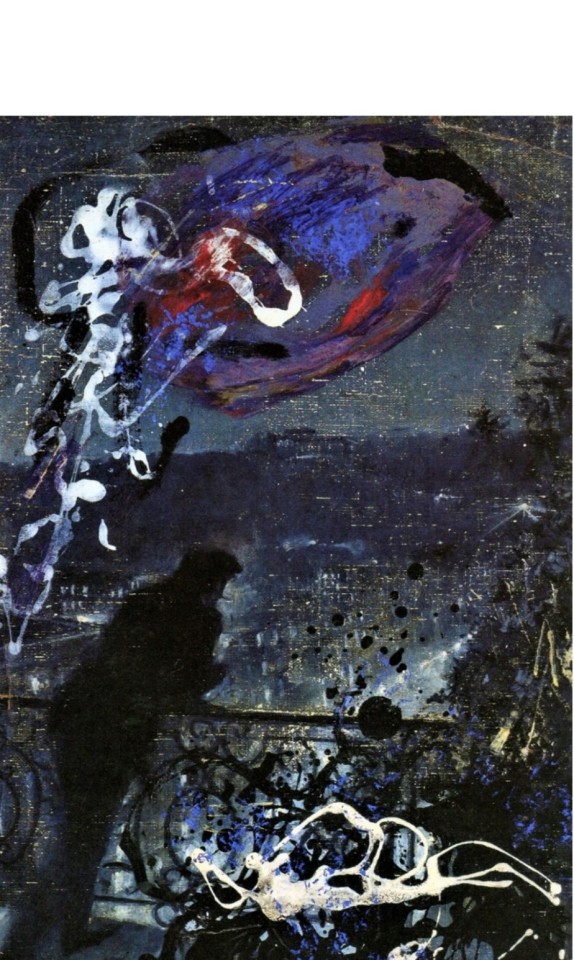

To explain Detournement – the hybrid aesthetic outlined in the SI communique - we can turn to Asger Jorn’s avant-garde painting Paris By Night (1959). referenced above.[8]

Paris By Night, Asger Jorn, 1959 Oil on Canvas

Rather than create (buy) a new painting, Jorn would salvage a piece of obsolete art, in this case a romantic lone figure gazing into the Paris night, from junk shops.[9] Taking these discarded portraits, Jorn added expressionistic patterns in the style of Jackson Pollock - an act of experimental cultural intervention he called a modification. The political import of the modification was that it allowed an artist to simultaneously breathe ‘new life’ or value into two different devalued cultures, in one straightforward gesture. The received dead-art of bourgeois naturalistic painting received renewed input from the avant-garde, whilst the avant-garde retained its status within the field of culture, a status suggested by the new art’s stubborn situation within the existent framing of the canvas or wooden picture frame. Through this new cultural arrangement Jorn gestured to destroy or devalue a passé art form - classic portrait painting, say - whilst, through reclamation or salvage, re-valued art’s essential potential as a carrier of meaning. Jorn’s experimentation, then, was not about re-making a new art or ‘ism’, ignorantly destroying the old ‘isms’, but ‘playing around’ with orthodox cultural heritage, amalgamating diverse forms of cultural production into revolutionary new conglomerations. Like the SI, the avant-garde Jorn wanted to ‘reinvent’ and ‘bankrupt’ culture on an ‘entirely new basis’, though, at the same time, acting in and with that culture.[10]

[8] ‘Paris By Night’ Jorn detourned painting analysis cut and pasted from doctoral thesis Worker’s Playtime, Steve Smith, 2004

[9] Crow, The Rise of the Sixties, pp. 50-51.

[10] Knabb, Situationist Anthology, pp. 111-113.

Detournement = DESTROY = Creation

It is this devaluation and re-valuation of one form of cultural expression at the expense of the other - the alchemical change brought about by experimental modification - that interests detourners and two women from Derbyshire; both work in fashion.

Derbyshire Maker Vivienne Westwood wearing detourned white-office shirt – Seditionaries - Circa 1976

Auchencairn, South-West Scotland, 2008:

17th June 2008. BBC Radio Scotland. Vivienne Westwood is live on air talking about her work. She says in her still-strong peak-district accent (slow and considered):

I’d been making clothes with holes and rips

in for quite a while.

I’d tear the cloth and

machine around it. I was making clothes

with holes in. People would come into the shop and

moan about the price.

I never understood why

they didn’t go home and make their own clothes

with holes in or rip the clothes they had.

November, 1976, Belper High School: In a state-of-the-art Derbyshire comprehensive school - under diffused delayed pressure from the subversive philosophy of a well-documented situationist led counter-culture of May ’68 - a movement bent on collapsing high and low cultural difference – a school led by an (allegedly) communist red-head and a progressive education policy that protested against the eleven-plus and so ripped up the difference between grammar and secondary modern education, high and low culture, school and non-school life - hip kids - some of whom end up in sixth form doing art - crowded around an opened New Musical Express; a cult-pose pop newspaper I despised as much as The Guardian) for it signified violent class distinction and affected commodity adoption by those who bought and drawled all over it like daft dogs. That said, there is the feint idea that something cultural is happening in England; a thing emergent from the sticky residual and stubborn dominant culture to paraphrase the aforementioned Raymond Williams. Inside the bohemian rock-world rag is a DIY identikit sketch of what a ‘punk rocker’ must dress like. And, not long to go from this real now, the “rough-tough” Clash (London punks) are playing a concert in Nottingham. After maths and before geography Alison Taylor, a student at Belper High School, strides down to the Oxfam shop on the still-a-mill-town-for-now High Street (or was it the ‘dead-man’s-shop on the Market Place?) with two lads from that comprehensive culturally-maligned detourned school. The future pro-textile-designer/maker buys two differently patterned formal suit jackets. Takes the unwanted old-man clothing home to Ambergate.[11] That night, in her bedroom-as-atelier, razor blades both out-of-fashion thin-lapelled jackets SSSHHHHKKKK down the middle seam. She sews them back up together – sutures rough as you like – and brings the two split rejigged garments back to school the next day. Not the next day, the local lads - early Derbyshire punks - go to see the group from the capital; stood in Nottingham Palais, wearing the doctored detourned jackets. Later in the year one of these punk rockers would get beaten up by Teddy Boys on Abbey Street, Derby, after leaving a shop selling commercial punk clothes called ID.

Alison Taylor, Belper High School, 1976

[11] Alison Taylor studied art at Hull Art College. She is a successful design-maker and has an artisan textile company in West Sussex.

October, 1976, Modern Belper – A New Housing Estate: A quiet clever man, Alex Paxton, lived a few doors up from us on Dovedale Crescent. He, like most of the others on this new 1960s Belper housing estate, owned his own house. Our house, like up to twenty-more, was not owned by us: it belonged to the National Coal Board (NCB). The nationalised industry purchased these new state-of-the-art houses to entice miners to old-mill-town Belper -- from South Scotland and County Durham -- to dig out coal in the Derbyshire pits. The coal dug up made electric. Some aspirational people on our modish ‘white-heat-of-technology’ street resented our social-cultural presence smearing their residential art and commodity dreams. Even though the miners were making electricity to drive their new consumer goods - Black & Decker saws, drills or jigsaws as well as TVs and refrigerators - they rejected the miners as an unwanted addition; black-collar stains on their social scene. A petition was circulated amongst residents to put a block on taking our place on the street even before the first miners arrived. What do I think today, about this coming-together? Was it accidental? Planned out? Socio-cultural Detournement? NCB left-wing thinkers creating a Jornian cultural intervention, making a modification, creating a new ‘Belper by Day’. Growing up on the estate the prole kids of the miners and the offspring of upwardly mobile toy shop owners, market traders, Deb chemists, self-employed electricians and skilled craftsman - products of two tribes - notionally clashed economically and culturally but also got mixed up with each other in an everyday picture. A sort of social alchemy came about and notional NCB hacking had made a new situation. A few of us naturally – post suedehead - became punks. Well me and the Deb chemist’s son; the original owner of one half of Alison Taylor’s hybrid schizoid jackets known as Paul Hough.

Hacking Life:

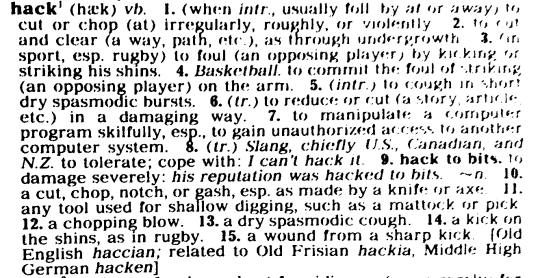

Poly(semic)

Nowadays living in the 21st century everywhere it’s hats off to hacking: ‘Hack this’ and ‘hack that’. There are 24-hour hack spaces in Leeds, Bristol, Manchester, Nottingham, Sheffield, Leicester, London: Hackspace UK is here to stay. I’ve seen ‘apron hack’ events at work; heard of pubescent international computer hackers on local news who live in Codnor, Portslade, or Fife; during a typical day I say self-critical things like ‘what a hack’ when I see or do bad workmanship; AVG watches out for me scanning for dangerous folk that hack your computer. Dominic Morrow told me on a visit to Nottingham Hack space “some-here-people-want-to-hack-the-state”. You can be hacked off, miserable and down in the mouth about something – the state or status of making perhaps (or people running you down for being miners). Aggression brought about by being hacked off can lead you to hack something to pieces; even death. Newspaper ‘hacks’ cut-up stories and quotes - distorting text to a new end and can produce hack writing, texts ‘banal, mediocre, or unoriginal’. Leicester hack space gang - anarchistic to a person - always managed to hack the communal beer barrel when we had re: make parties: ‘we’re only ‘ere for the beer’ and would give you a kick on the shin (a hack) to get to the bottom dregs of the local-brewed ‘Ay Up’ kegged ale before you could. Is the word/concept ‘hack’ what my old English lecturers would call critically a polysemic ‘floating signifier’? A sign/word/lexeme that can mean or be made to mean so many things - denotational with spiraling connotations - by so many different in-crowd users (like its sister word ‘disruptive’) that its position as a major mention-tool in contemporary maker hipster overuse renders it banal and unoriginal? Can you hack the word hack or hack hackerworld? Or is hack a positive case of a democratic general ‘unlimited semiosis’, a phrase borrowed from the proto semiotician Charles Pierce and adopted by Umberto Eco which describes the uncontrolled life of a sign/word in language?In my dull mind to hack describes a sort of contemporary hijacking, a commandeering of an artefact and then cutting it up for an adaption. As synthesiser, hacking culture re-makes the selected object into something useful and not of its originally designed purpose as commodity (for commodities as objects are what get hacked most): Toppo’s shoes and drawing pins; a green landscape in Belper carved up into housing estate; the private street hacked into by a mining community; grammar school clashed with secondary-modern education to form an new alloy called the comprehensive; plastic B 52 Bomber model becomes repurposed as teddy-boy paraphernalia; Oxfam jackets cut up and reformed, Crusoe hacks his ruined ship and makes an interior for his cave, and Westwood’s stencilled shirts adorned with zips and holes. Back in 2013, during the Re:make experimental phase of manufacturing a new Derby Museum of Making, a Rolls Royce engineer put together some plastic milk crates and with a pair of scissors cut up some thick cardboard and made a prototype back that slotted into the already-in-place slots of the milk crates. The back was modified and CNC cut from 12 mm plywood and 8mm clear acrylic. It became the infamous crate chair. The museum manufactured its own chairs; DIY self-production a radical gesture of active making against the passive buying ethics Westwood identified at her Kings Road shop SEX. Visitors asked ‘can we buy these chairs from you?’

Crate Chair, Co-produced, 2013, plastic, felt and plywood

Hacking is voguish then but not new, not now. I can think of two other interconnected examples of hacking; one historical the other contemporary (if you count the mid-70s as historical and today contemporary). Both activities and actors as ‘hackers’ used a common-garden DIY store electric jigsaw. In 1977 I used an inverted jigsaw at Abbey Patterns Derby to make a plywood pattern for a decorative grate. It was probably made by Black & Decker. Adam Blenkoe brought his modified Makita jigsaw to Derby in 2016.

Jigsaw Illustration, Woodworkers Bible, Alf Martensen,

Abbey Patterns, Derby 1976:

My first experience of any form of patternmaking - which is my original first-choice trade - was arranged by Alex Paxton. Some-thing called ‘a patternmaker’, he, as I have said, owned his own house – he was a business partner in Abbey Patterns, a small master-shop in Derby. Alex as patternmaker was a skilled man. We knew Alex was a maker because Alex’s wife came down to our rented house and inter alia mixed with us spoil of miners.

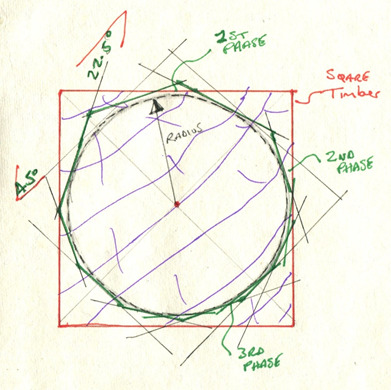

Back in 1976, still a schoolboy, while my mates were off to buy punk records after seeing see the Clash (modishly rejecting Tangerine Dream, Deep Purple, Genesis -- yada yada) I visited Abbey Patterns workshop one Saturday morning for a taster session. Arranged by my father via Alex via Pam his wife – I was invited to try patternmaking, see if I liked the strange esoteric trade, had aptitude for the rationally complex craft. Abbey Patterns was then -1977 – manufacturing in a tiny cramped pattern-shop in a post-residential converted house on Gerrard not Abbey Street. I got to the ‘hacked-out’ Derby house by bus. Prompt 8am. I was set to work right from the off. No time to lose. I had a single tea break when they the two partners stopped for ten minutes, until stopping the week’s work at 12pm. My task was to work on an improvised machine the patternmakers had contrived to shape a small pattern – approximately 300 x 300 mm square – the kind of pierced grate-cum-screen you see on the pavements of red-brick terraced housing forming cast-iron apertures that let air and light into small underground cellars, walls, and chimney stacks. The contraption was ingenious.

They had inverted an old Black & Decker/Wolf/Bosch Jigsaw, and removed the blade for a small wood file. The bed could tilt to create required degrees of draft or taper for patterns when machining intricate shaped work. A full-sized paper photocopy of the required intertwined design was glued with PVA onto a small sheet of 12mm birch plywood. The laminated ply product was perfect for making a pattern with fine interlocked sections because the pattern would have structural integrity at all sections of the pattern, thus resisting breakage (or shrinkage) in the foundry environment. It saved time-consuming jointing as might be expected in pre-plywood classic purist pattern practice and construction since the membrane of birch laminations made an integrated and thus strong stock material. However, plywood is tricky and hard to ‘pare out’ with traditional chisels and gouges. Conflicting grain directions add strength but carve poorly. A file can therefore abrade the material evenly and flatly.

The black lines on the white paper indicated to me where I had to file to. The fretwork design was cut as close to the line possible – potentially with the same customised jigsaw contraption using a blade rather than rasp or file. (This is pre - CNC existence. Today the design would simply be imported from a digital drawing package, into a tool-pathing software such as Vectric 2D Cut or v-carve, and automatically routed out with precision tapered hi-tech cutters. The CNC operator a semi-skilled presence. So, in some ways the inverted–hijacked jigsaw I used at Abbey Patterns prefigured this need for mechanised patternmaking. Abbey Patterns made a lot of grates, and detailed small scale cast-iron work that can still be seen on the Derby streets -- if you are smart/interested enough to spot them. In this way their business needs and technical nous drove forward their creative DIY product design, inventive in-house toolmaking. Amazed at what I had seen, I left Abbey Patterns when they said it was time to go home catching the red Trent 90 bus back to Belper. Looking back in time these skilled patternmakers didn’t self-consciously call themselves hackers.

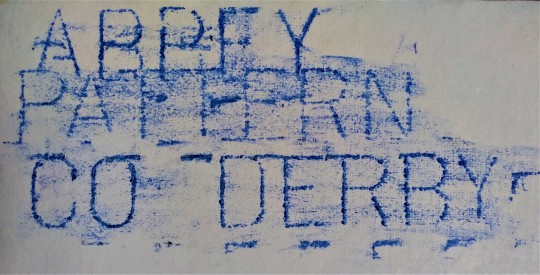

Abbey Pattern Street Grate, Cast Iron, Derby, 2022

(‘anything can be used’) - rubbing Abbey Pattern Co grate – blue charcoal on paper, Steve Smith, 2018

The Mekons, Leeds, circa 1976

440 Kingsland Road Workshops, London, 1992--“Never Been in a Riot”: Mark White was the first lead singer with the Leeds-university based punk groupuscule The Mekons. Around about 1977 The Mekons put out a delicious scrappy amateurish single “Never Been in a Riot”. Never Been in a Riot was the avant-garde groups anti-masculine pink repost to the butch ‘rough-tough rock’n’roll revolutionary red art of The Clash and their song “White Riot”. These softer punks were thus ideologically detourning the hard-core detourners -- hacking to bits the SI influenced cultural big-time punk-rock hackers (and the punk rock movement at large) posing in their stencilled political sloganeering shirts (Red Guard, Brigade Rosso) rebel anti-fashion contradictorily made popular and fashionable by Viv Westwood. Nowadays he was not a punk singer, but a humble maker in our cooperative London workshop: 440 Kingsland Road, an old print works converted and chopped in two – hacked into a ground-floor woodwork shop and first-floor graphic design studio - in Hackney.

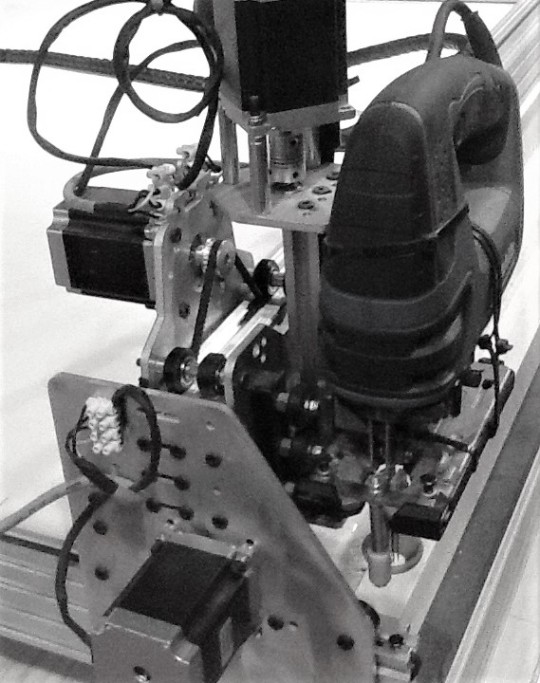

Fast forward to 2015. I am back working with a hacked jigsaw again in a Derby workshop. Returned, I am part of a team returning making to Lombe’s Silk Mill – the world’s first factory. In the workshop is a maker from London: Adam Blenkoe. Up-and-coming, a neo-21st century maker up from the East London Hack space – he is running a morning weaving workshop. Apart from Adam and me, students are all women. Interested in traditional textile crafts - embroidery, dressmaking, tapestry, weaving – attendees are disturbed to not find scissors, sewing machines, overlockers, embroidery hoops, needles and thread, paper patterns, plastic cutting French curves arranged on the cutting table, rather a selection of thick art books: thick cult texts on the art of Bauhaus, Russian constructivism, De Stijl.

There was no sign of a loom either. There was simply a Makita jigsaw bolted rather amateurishly to an aluminium off-the-shelf mobile CNC bed. Driven by electric stepper motors that pulsed right, left, vertical and horizontal, forward and back the jigsaw could be driven in micro movements along a digitally-programmed X-Y-Z axis. Like the inverted machine at Abbey Patterns the orthodox functional saw blade had been removed and replaced in this instance with a broad-gauge needle.

Commercial Makita Jigsaw Bolted to CNC Frame

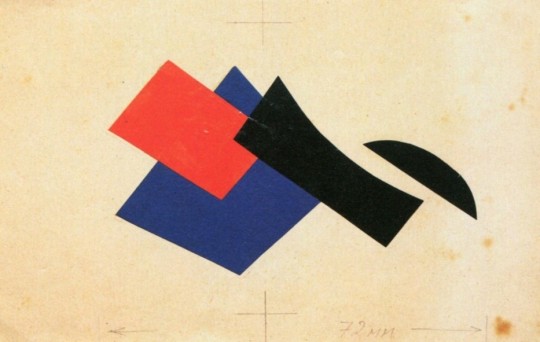

The women were encouraged to select abstract designs from the art books on the table. Then, having selected one avant-garde pattern, students cut felt or cotton samples replicating the geometry they had found in the coloured plates.

Liubov Popova, Embroidery Design For The Artisan Co-operative Verbovka, 1917 (cut-and-pasted papers on paper)

The bright primary-coloured sections were then individually placed on a large single canvas back cloth over which the jigsaw sat still waiting to be activated.

Adam Blenkoe and Student Loading the Jigsaw Loom

When each art-weaver student had added to the cloth picture – thus constructing a communal patterned wall hanging (à la Lyubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko, Annie Albers) - Blenkoe flicked the electric switch on the CNC.

Fired up by the powerful current of the mains electricity the jigsaw ranged over the cloth to a pre-set quilted grid pattern and, at the same time, as the probe-like needle oscillated in a highspeed pecking action, stabbed the felt through the background material. Sort of tattooing the textiles the constructivist cum Bauhausian inspired synthetic designs were infused deep into the skin of the white cloth. When the noisy jigsaw motor stopped running, returning quietly to its fixed X-Y-Z home position (the workshop sounded like a hi-tech weaving shop as the needle click-clicked-click-click clicked back and forth like speed shuttle making -- a kind of metallic sonic composition) the tapestry was complete. In stark contrast to the thin hard lifeless 2D reproduction masculine modernist plates the workshop attendees’ patterns were lifted from – the dead lifeless art prints were paradoxically facsimiles of historical designs for wall hangings or rugs - the plagiarised Silk Mill weaving had depth, softness, life, texture, warmth, a non-masculine aura. Post-man-work; maybe. Moreover, rather than simply passively (spectacularly) consuming the geometric abstract designs from the art book as commodity, the weavers-in-the-workshop had actively produced their own tangible material original self-made artefact.

Finished Constructivist Wall Hanging

Circa 1977 Alex Paxton, as I have conjected, didn’t know he had hacked the small bladed shop-bought DIY power tool – designed for amateur woodworkers to cut curved shapes – just like some of us didn’t know we were punks until the NME posted that picture of what a punk lookalike looked like. But I suggest, Blenkoe a 21st maker knew he was a hacker hacking this electric jigsaw. Obviously, Adam at the Museum of Making workshop Derby, wasn’t punching-out the State, but coloured felt. Yet, that said, there is for me, if no one else (even Blenkoe), hard political import in this radical soft textile-hacking gesture. Like The Mekons chant “Never Been in a Riot”, his antimacho punk art was a deft retro counter-critique within trendy macho-modernist (hackneyed) critical thought movements. His target - if not the Clash – was perhaps butch graphic aesthetics or cultural art revolutionaries and their sanctification of hard-edged constructivist art; Blenkoes workshop and his co-opted women students - was hitting back with a detourned form of constructivist/suprematist art ‘modified’ and emasculated with a sub-Jornian fuzzy textile making attitude. Self-conscious - perhaps ironic - metro-cosmopolitan Adam was cutting up – emasculating – man-making craftwork itself. Blenkoe took a masculinised woodworking tool ‘the jigsaw’ (and CNCing – a staple of the new ‘techno’ male-dominated maker movement) and co-opted ‘mediated’ it for a ‘feminised’ arty-crafty weaving course. One in the loom or jigsaw for men running all the male workshops in the world. Bauhaus detourned – constructivism hacked off. Hacking, then can be practical, technical, political or cultural.

No women at all if possible into the workshop, both for their sakes and the sake of the workshop…Weimar Bauhaus edict 1923

At the ‘revolutionary’ Bauhaus workshops, it is pointed out, the early years (1919-1920) the Council of Masters passed resolutions that aimed at benefitting the large numbers of women students attending the school. The new Weimar Constitution assured women unrestricted freedom of study. In his inaugural speech to the Bauhaus students Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus director, made express reference to the women present. His notes referred explicitly to ‘no special regard for ladies, all craftsmen in work’ and ‘absolute equality of status, and therefore absolute equality of responsibility’. Yet as early as September 1920 Gropius was backtracking. And suggesting ’no unnecessary experiments’ should be made and that women should be sent directly to the weaving shops having completed the mandatory Vorkurs (the compendium multidisciplinary craft course 21st century art foundation courses came from). If weaving was refused, rebel female students were directed towards bookbinding or pottery. No women were allowed to study architecture; female student cohort made unwelcome in the woodwork shop.

Bauhaus Weaving Studio Loom

It may be noted that the Weimar Bauhaus presented a number of fundamental obstacles to the admission of women and that those who overcame the first hurdles were forcibly chanelled into the weaving workshop. Much of the art then being produced by women was dismissed by men as ‘feminine’ or ‘handicrafts’. The men were afraid of too strong an ‘arty-crafty’ tendency and saw the goal of the Bauhaus – architecture – endangered. (Bauhaus archive, 1919-1920, Magdalena Droste)

Bauhaus girls looking out from weaving shop, circa 1925

Bolshevik art in the Soviet Union, in particular ‘constructivism’ and its related movements ‘suprematicism’ and ‘productivism’, post-1917 revolution, looked to deconstruct the bourgeois world epitomised by a residual adherence to a ‘his’ and ‘her’ conception of society and human expression. The Russian avant-garde – of which Liubov Popova as a rare woman art-worker was a part – practice ‘unfolded in the context of the Bolsheviks proclamation of the emancipation of women under socialism, which was supposed to entail the destruction of the private, domestic sphere of everyday life in which women had traditionally been trapped, and their seamless entry into productive and public life – including the practice of art.’ However, coincidental with the gender-distinctions and craft bias evidenced at the Weimar Bauhaus the progressive constructivist project still split artisan practices along predictable male-female lines:

Popova chose to enter production through the traditionally feminine fields of fabric and clothing design, while Rodchenko [her close communist art collaborator] taught in the exclusively masculine wood and metalworking faculty at the newly established state art school VKhUTEMAS, focusing on furniture design, and maintained a reputation for ‘iron constructive power’ among his colleagues in the avant-garde group Lef (Left Front of the Arts).[12]

[12] Rodchenko & Popova: Defining Constructivism, 2009, Tate Modern Exhibition Publication. In ‘His and Her Constructivism’ Christina Kiaer writes that despite Popova Rodchenko anomaly, ‘There is ample evidence, within the works, writings, and lifestyles of the members of the left avant-garde, that they rejected most stereotypes of femininity inherited from capitalism, and embraced the egalitarian ideals of the ‘new everyday life’ and the full participation of women in artistic, literary, and working life’. She calls the constructivist radicals formal experimenters and productive practitioners of a prototypical ‘Bolshevik feminism’.

Cultural Goods:

“Kings road shopper…it’s just a fake make no mistake a rip off for me a Rolls for them” Rip Off Sham 69

“Turning rebellion into money” White Man in Hammersmith Palais, The Clash

Back to Vivien Westwood, then. A brilliant maker, if confused thinker, this infamous Derbyshire rebel woman professed a Situationist agenda and, despite supressing some of it with some sweet bad faith -- post 1968 she’s running a Kings Road shop selling commodified rebellion, a situation critiqued by the situationist influenced punk commodities she aligned herself with –- she was in 1977 (and still is) anti-consumption –pro-making. What else was/is her complaint that folks didn’t/don’t go home and make their own ripped clothing or adorn it with zips and DIY stencilled slogans about then? But what did the SI (Situationist International) have against commodities? Despite unthinkingly (knowingly) luring the likes of Vivienne Westwood into their philosophical elephant trap – as she co-opted their abandoned-by-now Mai ’68 theory for snappy political slogans she could rescue, repurpose and hack for her very saleable detourned revolutionary clothing “demand the Impossible” - Raoul Vaneigem and the SI wrote about how paradoxically a sort of cultural existential spiritual poverty is brought about by the totalising domination of the Society of the Spectacle in which commodified goods and their spectacular consumption are paid for in the name of social distinction by consumers. But these states-of-modern mind are in fact disabling, ontologically ‘alienating’ rendering the subject a passive consumer. They called this condition-in-common proletarianisation: The act of choosing between a variety of commodities, whether they are roles or things, lifestyles, or opinions is, by virtue of its distinctive hierarchical position in the alienated whole, fated to be an instance of ‘false choice offered by a spectacular abundance’; an irrelevant and meaningless choice between empty and equivalent commodities.

Every product represents the hope for ‘a dramatic shortcut to the long-awaited promised land of total consumption’. But the fulfilment of this promise is possible only with the attainment of the totality of commodities, a desire which excites the accumulation of commodities but which is ultimately insatiable. ‘The satisfaction that the commodity in its abundance can no longer supply by virtue of its use value is now sought in the acknowledgement of its value qua commodity’. Commodities circulate as ends in themselves; goods which are presented as unique ultimate products, the very best and latest goods, are replaced and forgotten the next. (Sadie Plant, The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age, - Guy Debord Society of the Spectacle cited in ‘’)

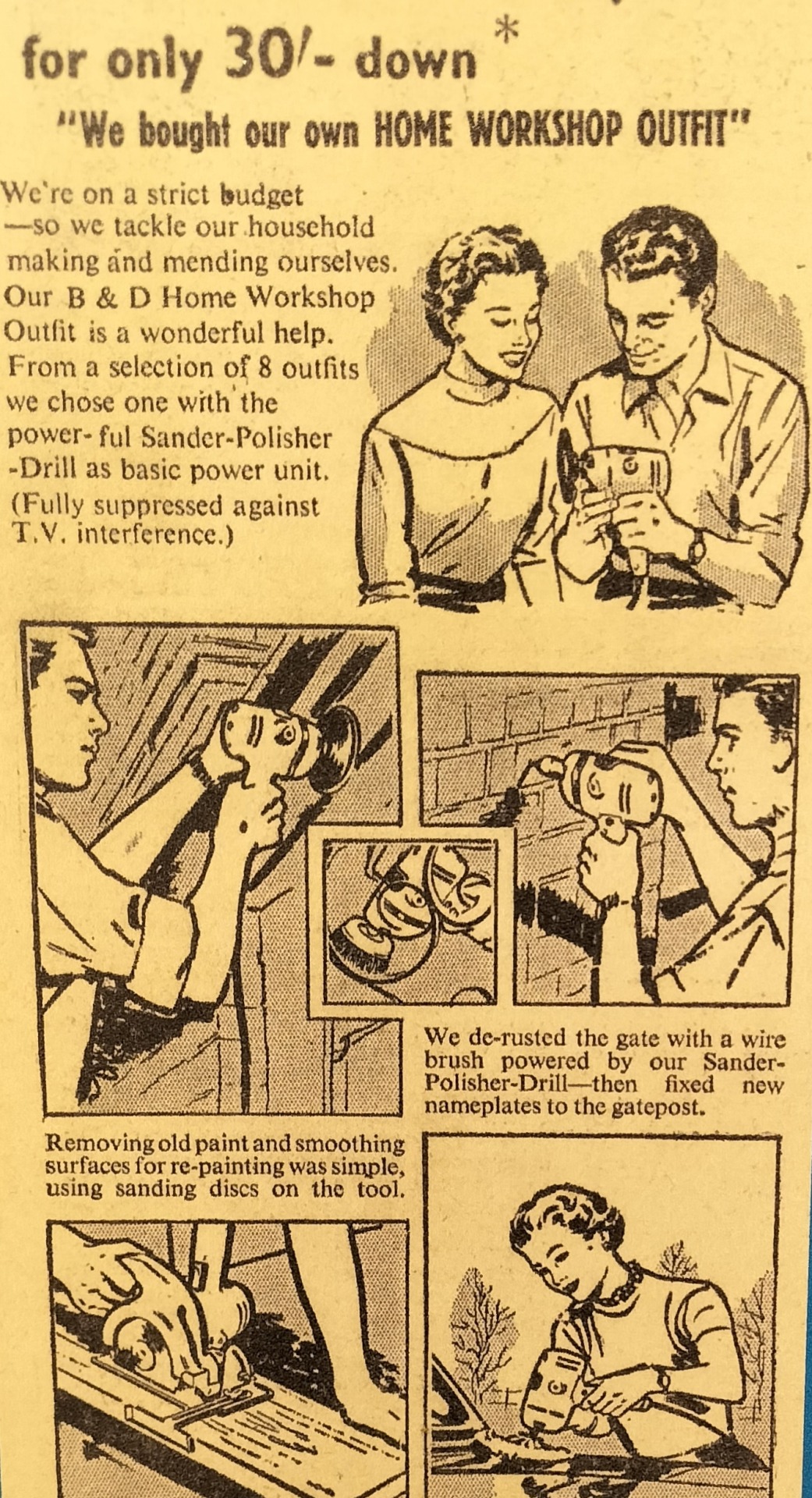

Man Gifts, Black and Decker advertisement, circa 1950s

But as we have seen above, within radical SI influenced culture (macho punk V effete punk) there, by anti-spectacle logic, exists a circular self-critical ongoing examination of the holes and misunderstandings in its own theoretical position. (The society of the spectacle is wholesale, totalitarian, and therefore subjectively inescapable) Vaneigem – the Mai ’68 philosopher (overshadowed by distinctive Debord (philosopher as commodity)) - might contra Debord - controversially shout out: "THREE CHEEERS FOR COMMODIITES—HIP-HIP-HOORAY”. Writing in 1967 -- contra inter alia the malign product fetishism the continental radicals sensed pervading everyday post-war life -- Vaneigem declared for a need, not to refuse manufactured goods, but to subvert modernity’s electrical and technological commodities for creative ends. Predicting, pre-empting, prescribing, ‘producing’ what we today call ‘hacking’, a creative German engineer he told of, ‘Using makeshift equipment and negligible funds’, had created a DIY apparatus able to replace a Cyclotron; a homemade particle accelerator using magnets and high voltage electrodes. (The Revolution of Everyday Life). Blenkoe and his subjugated reborn modern-man jigsaw can be retrospectively reviewed from this Vaneigem(ist) perspective.

Clash of Worlds:

Bauhaus, “Arty” Book, Cover Detail,

If an ELU electric jigsaw, like a Seditionaries shirt, the glossy art book on Bauhaus Adam Blenkoe left out for his constructivist felt workshop, a Clash LP, Gibson Brogues, are distinctive BRANDED commodities so are Universities, art galleries, football grounds, shops, night clubs. Museums couldn’t escape the critical mind of the SI, any more than the power tool did. These carefully curated places can be – and are – today consumed as any cultural commodity. Modern subjects consume passively the museum as brand, looking over the fixed and revered inanimate objects. In consuming these residual respected cultures, we are looking to exhibit a spectacle of intellectual social distinction. The SI were getting at the exhibitionistic posing inherent in spectacular intellectual-consecrated consumption. ‘Who do we think is watching us when we consume culture?’ to paraphrase Jean Paul Sartre. (In his 2018 book Fewer Better Things Glenn Adamson – former director of the Museum of Arts and Design New York ‘one of the main things people look at in exhibitions is one another’.

Peter Wollen, in a very precis reprise of the compendium of ideas which situationism is constructed from writes that, despite their provocative journalism and philosophical gesturing, the Situationists’ wilder projects for détournement never took off. But they did want to change the cultural landscape and they are still well known for their urban fantasies and desire to alter the city. Arguing that ‘the Paris Metro should be running all night, special aerial runways should be constructed to facilitate journeys across the rooftops, churches should be turned into children’s playgrounds (or Chambers of Horror), railway stations should be left exactly as they are—except that all timetables and travel information should be removed from them. Graveyards should be abolished. Prisons should be opened. Street-names should be changed’ and anti-museums set up; art galleries should be raided i.e. hacked: ‘All museums should be closed and the art works distributed, to be hung in bars and Arab cafés’.

Jean Baudrillard in Revenge of the Crystal; Selected Writings on the Modern Object and its Destiny: 1968-1983 suggests that after functional objects, objects he calls ‘by-gone objects’ have been superseded or become obsolete in commodified society, i.e. non-functional, they nevertheless stick around the social and cultural scene and inter alia re-function as ‘rare, quaint, folkloric, exotic or antique objects. They seem inconsistent with the calculus of functional demands in conforming to a different order of longing: testimony, remembrance, nostalgia, escapism’. Baudrillard theorist of the simulacra goes on ‘One might be tempted to see them as relics of the traditional and symbolic order. Yet for all their difference, these objects also form part of modernity, and this is the source of their double meaning’[13] to the philosopher of commodity-objects-as signs list we might add ‘industrial’. For writing in 1968 amidst the heat of the Mai’68 anti-commodity fire Baudrillard and his cohort were still living in the epoch of production, manufacturing and thus industrial society. In our post-industrial setting the objects and functional tools of industry thus evoke as live signs of by-gone dead objects the secondary denotations and connotations he identifies in religious, ethnic, hereditary objects. Industrial-alia is chic and now belongs to that different order of longing: testimony, remembrance, nostalgia, escapism.

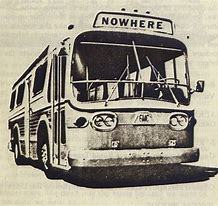

The industrially-derived objects on display as museum ‘collections’- housed in the open-displays of Museum of Making – are not left to do the work of this secondary order: creating/facilitating passive nostalgic longing in its spectating visitors. The world’s first factory is the Silk Mill in Derby which as the Museum of Making unlike many heritage places (and definitely other passive engagement museums –physically speaking anyway) has an authentic working workshop space where things can be actively made inspired by and associated with the industrial artefacts and objects on show. For example, my making course Kitchenalia used selected relevant industrial objects from the collections – carved patterns, aero-dynamic wooden models, presentation bowls and hand-made spoke gouges – as a starting point for this woodworking course. Although participants made serving platters, utensils and bowls, they explored the same skills and techniques used to make the objects picked out from the collections. In this way they were actively engaging with the process of making the by-gone functional objects and refuting their consignment to the realms of that secondary order of non-functionalism. Plus, in making artefacts they are acting under Westwood’s punkish radical imperative to make their own functional objects – not buy them from the internet or expensive commercial cookery shops. Consumption is therefore purposefully clashed with authentic production, commercialism confronted with DIY. The workshops are at the living centre of the museums’ making ethos and inform a certain development of a city ‘Making Quarter’. As part of the MoM project we have already created a mobile workshop ‘The Makory’ which we take out across the city - loaded up with tools and museum collections – into unorthodox spaces like laybys, country parks and inner-city concrete carparks reclaiming creativity and making – moving the museum in a converted – hacked - library bus.

[13] J. Baudrillard, Revenge of the Crystal, p35

Punk Making:

Punk was infamously founded (found out) on a radical DIY ethic. The low-fi influential fanzine Sniffin’ Glue drove forward this do-it-yourself ethic of anti-consumption – a well-told critique of complicated commercial pop and elite ‘progressive’ music – by printing in one of its most renowned editions a diagram showing three guitar chords. The gesture was a call to self-production, the guitar its means of original production. Showing finger positions required to make A, E, G chords it challenged the passive consumer-of-other-people’s-songs to stop passive consumption fandom and demanded “NOW FORM A BAND”.

Sniffin Glue, Fanzine, 1976

Over the last thirty years I have led many studio-courses and summer-school introductions to furniture making; most recently in courses prototyping #2 development phase of Museum of Making programming and a post-opening two craft course called Kitchenalia and Plywood Furniture where attendees made their own handmade chopping boards bowls and utensils, cabinets, bookcases, shelving units. After explaining to students what they can do with a simple raw skill saw and rail, biscuit jointer, and router, I refer to the Sniffin’ Glue provocation. I say, plagiarising Sniffin’ Glue, in order to provoke as the fanzine wanted to, ‘here’s a saw, here’s a router, here’s a biscuit jointer -- now you go make your own furniture’.

Power tools – hand-held machines – are not independently spectacular commodities, but inevitably gain their social distinction – semiotic worth – from their purchase price; good kit is expensive. But community craft centres like ORW, where I worked for ten years in London, and the 2021 Museum of Making inner-city workshop, are built on the premise of the DIY ethic. Not self-consciously anarchist or punk, yet subconsciously culturally determined by the autonomous punk ethos – all small community fabrication studios enable independent making by holding-in-common the tools needed for DIY furniture production: a saw, a router, a biscuit jointer (21st century it is a domino jointer). Given that amateur makers and post-grad students can’t afford to set up workshops and buy expensive equipment seminal to the manufacture of aesthetic and utilitarian artefacts, (you need more than scissors or razor blade) the community workshop hold these means of production as joint stock which can be commandeered with membership fees, small rents, and short-term public hire. Skilled help and technical advice the essential complimentary resource.

In a ‘sniffing glue’ punk-making mind-set I try to disenchant the ‘mystery of making’ (without undermining its skilled aspect) as fast as possible by associating independent making with the three-chord-mentality. The rawness of three-chord making can, I often want to point out, be reduced to two items of kit (planer and saw) or one chord production with a modern accurate circular or hand-held rail saw. In a workshop with a single robust circular saw, stripped back of guards and riving knives (illegally) I can rip, crosscut, groove, rebate, tongue, tenon and mortice furniture components to a professional standard. Most south-of-England antique restorers and cabinet-making workshops - secreted in hard-to -find anonymous marginal buildings - work a central table saw hard in this anarchist making fashion - stereotypically an old Wadkin cast-iron like the one we had at the Silk Mill circa 2013. I know because I’ve been in these raw brute foundational workshops and made complex beautiful stylish furniture in them. They exist all over the country if you can or want to find them and design/make your own stuff.