Photo

A Plan for the Endgame: Plots, Protests, Scandals and Assassinations

On January 30, 1970, the insolence of Edgar Jopson, the Atenean student leader of the moderate National Union of Students in the Philippines (NUSP) whose family had a grocery business, was what President Marcos couldn’t take. Sensing the spirit of “revolution” after the January 26 riot triggered by his SONA, Marcos wanted to placate the people by inviting the student leaders and university faculty into Malacañang to express grievances. The previous day, Marcos called on the president of the University of the Philippines, Salvador P. Lopez, for a conversation, in line with many of the UP faculty holding a street demonstration in Agrifina Circle. Journalist Pete Lacaba described Marcos as reprimanding Lopez, quoting him saying “You yourselves are vague and confused about the issues you have raised against the government.” This was followed by a challenge to any Communist to debate.

*UP President Salvador Lopez, with the UP Faculty, meets with President Marcos, January 29, 1970. Source: FQS Library.

This was corroborated by what Marcos said in his diary:

I had said that I was disappointed in the faculty of my alma matter; that the UP was charged as the spawning ground of communism and that the manifesto was full of ambiguous generalities that had a familiar ring to them.

Hence, it was this same intent that Marcos extended his invitation to Jopson, recognizing NUSP as one of the largest youth groups in the country.

*Edgar Jopson, Portia Ilagan and other student leaders, meeting with President Marcos on January 30, 1970. Source: FQS Library

So Jopson went to Malacañang with Portia Portia Ilagan of National Students League (NSL) and a host of other student leaders from different campuses. No one knows what went on in those few hours of conversation, but Lacaba described it in a few words:

“The President had told them he was not interested in a third term. Jopson had demanded: ‘Put that down in writing,’ and Mr. Marcos, piqued by the boy’s insolence, had lashed back at Jopson by calling him the ‘son of a grocer.’”

Jopson, a Moderate, would soon be disillusioned by government impunity and corruption that he would soon go underground with the Communist Party after the declaration of Martial Law, and eventually get killed in 1982.

As Jopson, Ilagan and student leaders made their way out of the Palace past 6:00 pm, Malacañang was already under siege by violent protesters. Known as the Battle of Mendiola, it was a new level of fierce anger, the most violent demonstration yet, unleashed by the rallyists on government, as they captured a fire truck to ram it at Gate 4 of Malacañang. Upon entry on the grounds, a government car was burned and stones were thrown on palace windows. Several buildings were also burned. The Presidential Guard Battalion, the Constabulary, the Metrocom, and the Special Forces all united to break the siege at the Palace. Students fled as tear gas filled the streets of Mendiola, and conflict spread around Aguila, Legarda and Recto. The violence was eventually quelled after the long night, and papers the next day revealed the casualties: 4 deaths, 300 arrested and detained in Camp Crame.

Violent protesters burned a government car within Malacañang grounds on January 30, 1970 near Gate 4 of the Palace. The Presidential Security Group cordoned the Palace to push back the protesters, throwing tear gas.

*The streets of Manila (possibly Avenida) after the Battle of Mendiola, January 31, 1970. Source: FQS Library.

*Policemen advance against the protesters, with shields and truncheons, January 30, 1970. Source: FQS Library.

Amidst the brouhaha of the moment, with Marcos announcing on live television that the riot was an attempt by Communists to overthrow his government, Marcos was preoccupied with fleshing out his plans to put the unrest at bay, and maybe use it to legitimize his extending of executive power.

He was being, quite frankly, paranoid.

Marcos was thinking of a myriad of possibilities. Four days after his inaugural, for example, Marcos wrote in his diary:

They [Lopezes and Montelibanos] are the worst oligarchs in the country. I must stop them from using the government for their own purposes.

Marcos was already plotting on unseating his Vice President Fernando Lopez this early. Clearly, the choosing of his running mate was only made out of political expediency.

This journal entry was followed by another one, indicating that Marcos have long suspected the ROTC Hunter’s Guerrillas, led by World War II hero Eleuterio Adevoso, of planning a coup against him. This was corroborated by Primitivo Mijares’ account, who wrote in his book that Marcos believed Adevoso and Sergio Osmeña Jr. were conspiring against him.

And then there was also Marcos’ plans to depose House Speaker Jose B. Laurel. For Marcos, according to his diary entry on January 5, 1970, Laurel was implementing “socialist and communist policies” under “the guise of nationalism.” While that may be Marcos’ perspective, it must also be noted that the Speaker was the one strategically positioned in the House of Representatives to oppose the President. Of course, as history would tell us, the lower chamber was and has always been easily swayed or pressured by the incumbent President.

Then there was also the United States. As Marcos would write in the same diary, he met with U.S. Ambassador Henry Byroade, confronting the ambassador of rumors being spread allegedly by the Liberal Party that a coup was on its initial planning and it was backed up by the U.S. The ambassador was said to have denied this, and gave assurance that the Americans would cooperate, to Marcos’ relief. In another account by journalist Raymond Bonner, however, Byroade, probably sensing this alarmist stance of Marcos, warned him that if ever Philippine democracy was toppled, the U.S. would react negatively against the Marcos’ administration. The American ambassador probably sensed Marcos’ plans for the imposition of Martial rule.

The next day, on January 31, Juan Ponce Enrile’s feasibility study on Martial Law was finally submitted to Marcos. Marcos then, met with the Defense Secretary, Chief of Staff and other military service and staff and divulged to them the eventuality of suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus (citizens could be detained without trial or fair hearing). He would also write in his diary possible opposition to this in the media, identifying Chino Roces of Manila Times and Teodoro Locsin Sr. of the Philippines Free Press.

Marcos wasted no time. By February 7th, he reshuffled his Cabinet, appointing then Justice Secretary Enrile as his new Defense Secretary on the 8th. He also proceeded with the reshuffling of the top brass of the Armed Forces. Thus began the “Ilocanization” of the Philippine military, as many Ilocanos were promoted to higher ranking positions, ignoring merit or seniority, ensuring the military’s loyalty to Marcos.

On the 12th, a massive rally of 50,000 people assembled at Plaza Miranda in Quiapo, sponsored by an unheard-of group, the Movement for a Democratic Philippines, a coalition of progressive groups. It held a massive “teach-in” assembly, teaching the protesters the meaning of the terms imperialism, feudalism and fascism, all of which, the protesters believed, were espoused and epitomized by Marcos. Marcos himself was surprised of how peaceful that rally was. He noted on his diary:

For a time I secretly hoped that the demonstrators would attack the palace so that we could employ the total solution. But it would be bloody and messy.

*A page of the Marcos Diary, on February 12, 1970. Source: Philippine Diary Project. A note to historians: Normally, diaries are private and made in secret, and thus, the writer tends to be brutally honest, with no inhibitions on his part. However, a reader would get an impression that Marcos seem to be conscious that his diary will be read widely for posterity. Hence to obtain an impartial view of an event in question, one has to corroborate Marcos’ claims in his diary versus other existing documents of the time to arrive at an impartial judgment.

On February 19, Marcos announced for the first time publicly a possibility of the imposition of martial law if these rallies continue. And yet, it only fired up the protests. On February 25, Manila Chronicle writer, Indalecio Soliongco writes that it was Marcos who should change, and prove to the people that he is not adhering to “imperialism, feudalism and fascism.” The writer warned that if Marcos continue to deafen his ears to the people’s plight and tighten the noose, his administration would be the “most turbulent in history.”

But the brutality of the police on the protesters only increased. The Communist scare was implied by Marcos in all his actions and speeches. He ordered the arrest and deportation of Rizal and Quintin Yuyitung who managed the Chinese Commercial News. Marcos accused them of engaging in communist activities. This was followed by an arrest of the president and faculty of Miriam College, all of whom were being accused by Marcos of inciting rebellion. Nilo Tayag, leader of the militant Kabataang Makabayan, was arrested on June 11, triggering another protest on Independence Day, with large streamers that said, “Expose Fake Independence and Fake Democracy! Finish the Unfinished Revolution!”

And as if validating the discontent and the hatred of protesters on corruption in all levels of government, two assassination attempts were made that year. One failed and the other succeeded. Rep. Salipada Pendatun of the Liberal Party was gunned on September 24, by unknown men using sophisticated weaponry (armalite rifles and grenade launchers). The assassination failed, but Pendatun’s bodyguard was killed.

*Unidentified gunmen gunned Rep. Floro Crisologo on October 18, 1970 while hearing mass at the Vigan Cathedral. Source: Xiao Chua

Meanwhile, on October 18, Rep. Floro Crisologo (head of the political dynasty whom the Crisologo Street in Vigan was named), was gunned down inside the Vigan cathedral, and was instantly killed, shocking the nation. Mijares would later write that Crisologo turned out to be involved in the tobacco monopoly with President Marcos and Col. Fabian Ver. Crisologo confronted Marcos and threatened him of exposing the entire operation if he doesn’t get his share, thereby leading to his assassination. Even the assassins themselves, upon asking of their fee to their superiors, were also murdered to tie loose ends.

All this while the campaign for the election of the delegates of the Constitutional Convention was on, which was another controversial thing in itself. Many of whom were elected in the Convention tasked to revise the 1935 Constitution were delegates who were easily swayed by Marcos. That was, despite the people’s insistent demand for the ConCon to be non-partisan.

*Philippines Free Press editorial cartoon, circa 1971. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Hence another conflict would ensue, this time in the premier State University, the University of the Philippines in Diliman. From February 1 to 9, 1971, UP student activists and faculty, echoing the activists from various schools and universities, private or public, occupied their campus and barricaded its roads for 9 days in protest of the price hike on oil which was caused by rampant spending and borrowing in government, exacerbated by corruption. Known as the Diliman Commune, it was the first organized student activist demonstration since the First Quarter Storm. It was a “militant solidarity of the students against military incursions into the campus,” said UP Professor, and now Secretary of Social Welfare and Development, Judy Taguiwalo. Historian Cesar Majul reportedly joined the protests. Meanwhile, Senator Eva Kalaw visited the protesters and gave away food. The Philippine Constabulary with the UP Police entered the campus and arrested students and faculty alike, ending the standoff, with 17 year old freshman UP student, Pastor Medina of Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan, getting killed.

Journalist Pete Lacaba, upon realizing that even students from “exclusive schools” have become militant, said:

“What is it about this society and these times that has driven the best minds of my generation to dissipation and despair, or taken them down the road to revolution?… anyone who bothered to listen [to them] intently would have felt a chill in the spine, a shudder in the heart, a thickening in the blood.”

The Road to Martial Law is a series of blog posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The Road so far:

- It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

- Marcos Beginnings

- Truth or Dare?: Marcos during WWII

- The Turbulent ‘60s and Marcos’ Ascent to Power

- The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the ‘60s

- The First Quarter Storm of 1970: The Philippines on the Brink

Photo Slides above:

(1) A scene from the Battle of Mendiola, on the night of January 30, 1970. The photo was taken during the storming of the Malacañan Palace. Source: The FQS Library.

(2) A scene from the Diliman Commune, on February 1971. The Philippine Constabulary surrounds students protesting near the Oblation. One can see UP’s Quezon Hall from afar. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

(3) An editorial cartoon from the Philippines Free Press, circa 1970. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Bibliography

Bonner, Raymond. Waltzing with the Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy. New York: Times Books, 1987.

Doronila, Amando. The State, Economic Transformation, and Political Change in the Philippines, 1946-1972. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Enrile, Juan Ponce. Juan Ponce Enrile: A Memoir. Quezon City, ABS-CBN Publishing Inc., 2012.

Lacaba, Jose. Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage: The First Quarter Storm & Related Events. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, Inc., 2003.

Marcos, Ferdinand E., “January 4, 1970,” Philippine Diary Project, link.

Marcos, Ferdinand E., “January 23, 1970 ,” Philippine Diary Project, link

Marcos, Ferdinand E., “January 27, 1970,” Philippine Diary Project, link.

Marcos, Ferdinand E., “January 31, 1970,” Philippine Diary Project, link.

McCoy, Alfred W. Closer than Brothers: Manhood at the Philippine Military Academy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999.

Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. San Francisco: Union Square Publications, 1976.

Pimentel Jr., Aquilino. Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story. Mandaluyong City: Cacho Publishing House, 2006.

Robles, Raissa. Marcos Martial Law: Never Again, Student Edition. Quezon City: Filipinos for a Better Philippines, Inc., 2016.

Santos, Vergel. Chino and His Time. Pasig: Anvil Publishing, Inc., 2010.

Taguiwalo, Judy, “Notes on the 1971 Diliman Commune,” Diliman Diary, February 24, 2011, link.

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Repeat steps 1, 2, 3.

— Duterte's administration.

Hijacking Democracy: The Mood Before the Declaration of Martial Law

It was year 1972. President Ferdinand Marcos had everything planned out for the full implementation of a nationwide Martial Law. He was just looking for the timing. Most of the media, with the exception of Manila Chronicle and the Philippines Free Press, did not believe that Marcos had the audacity to implement Martial Law. Even opposition leaders, like Senator Ninoy Aquino didn’t. But perhaps, this element of surprise played out in Marcos’ favor as we would see.

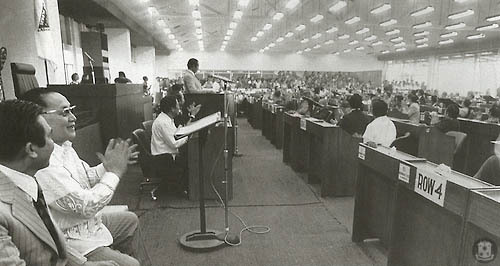

*Former President Diosdado Macapagal heads the Constitutional Convention at Quezon City Hall, sometime in 1971. Source: National Library of the Philippines.

As the Constitutional Convention continued to convene in the Quezon City Hall in amending the 1935 Constitution, rumors of Malacañang’s hand in influencing the delegates to vote for a parliamentary system of government slowly made it to the news.

*Free Press editorial cartoon on the Constitutional Convention, 1972. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Free Press editorial dated January 22, 1972 noted:

Marcos, if he were not disqualified from running for a third term by the new Constitution and should run, would get the political licking of his life. As a presidential candidate Marcos would be a sure loser. But if the parliamentary system were adopted, then Marcos could run for Parliament in Ilocos Norte, win—and be elected Premier through bribery of the members of Parliament, who would be no better than congressmen, or out of a sense of gratitude on the part of those whose election he had financed with private funds and, as President still in 1973, with government funds. As the richest member of Parliament, Marcos would be sure of election as Premier by a corrupt or corruptible majority of that body, which may be expected to rise to no higher moral level than the present House of “Representathieves.”

The parliamentary system, if adopted by the Constitutional Convention, would mean Marcos in Malacañang till hell freezes over. Unless he, not to mention Mrs. Marcos, is disqualified from being elected to the Premiership by the new charter.

As quiet as many people would have wanted 1972 to be, and with the shadow of the Plaza Miranda bombing looming over everyone’s heads, the nation once again would be wrought with another bombing, this time in the Arca Building in Pasay on the night of February 15. Witnesses claimed to have seen the bombers as two men riding in tandem using motorcycles. This was followed by another explosion, on April 23. A bomb in the boardroom of the Filipinas Orient Airways detonated. As days and months passed, the bombings would become more frequent and more devastating.

*President Ferdinand Marcos meets the top brass of the military, sometime in 1972. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

On May 8th, according to an entry in the Marcos Diary, Marcos met with key military leaders “to update the contingency plans and the list of target personalities in the event of the use of emergency powers.” The dreaded list of people to be arrested had already been drafted. “I directed Sec. Ponce Enrile to finalize all documentation for the contingency plans, including the orders and implementation.”

*ConCon Delegate Eduardo Quintero reveals the envelope containing bribe money, allegedly given away to 39 ConCon delegates by Malacañang, August 1972. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Meanwhile, on May 29th in the ConCon, in one of the most shocking reveals yet that confirms Marcos’s hand on the Convention, Delegate Eduardo Quintero of Leyte revealed to the Convention floor that on January 7th, 39 ConCon delegates were invited to a dinner in Malacañan Palace, after which, Delegate Casimiro Madarang of Cebu announced, “The envelopes are ready. They will be distributed in a couple of days.” Quintero confessed that the envelope contained P1,000.00 in 50-peso bills, as bribery for them to vote in favor of parliamentary form of government. On that same day of the exposé which had already made waves in the media, President Marcos vehemently denied the allegation saying Quintero’s statement was “as vicious as it is false.”

*Philippines Free Press editorial cartoon of the alleged Quintero exposé, pointing to the alleged January 6 dinner of some ConCon delegates at Malacañang. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

As a result of such allegations, by June, an interesting development took place in the ConCon. Several delegates forwarded a proposal in the new constitution barring any former President, his wife, and relatives by affinity and consanguinity within the fourth civil degree from seeking the post of Prime Minister. It was nicknamed the “Ban Marcos” resolution, with which Senator Arturo Tolentino called on Marcos to support. It would have been the first detailed anti-dynasty provision within a Philippine constitution, designed perfectly for Philippine politics that has always been plagued with political dynasties, one of the culprits of corruption.

*Philippines Free Press editorial cartoon of the bomb scare that spread throughout the country, August 1972. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

In the streets, the bombings continued. Bombs were detonated at the South Vietnam Embassy, the Court of Industrial Relations, Philippine Trust Company in Cubao, Philam Life Building in UN Avenue Manila, from June to July. The government blamed all on the Communist insurgency. This was supplemented by police reports. On June 18, for example, at Barrio Taringsing, Cordon, Isabela, an alleged copy of the document entitled “Regional Program of Action 1972” was said to have been captured by the Constabulary. The document allegedly revealed the overall plan of the CPP to “foment discontent and precipitate the tide of nationwide mass revolution.” Whether true or false, we cannot determine the validity of the document, but in Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law, this was cited as one of the reasons for it. In fact, this became Marcos’ “proof” that Communists were behind the bombings.

Reports also came about the illegal entry of a substantial quantity of weapons and ammunition, brought to the country by the Communist Party of the Philippines via an unidentified U-boat, with some 200 passengers. According to a report by Col. Rosendo Cruz, it landed at Digoyo Point, Palanan, Isabela. The newly appointed chief of the Philippine Constabulary, Fidel Ramos, went to Palanan to investigate on June 30, only to find out that it was “without basis.”

By July 5, after midnight, MV Karagatan, unloaded cargo at Digoyo Point. The cargo consisted of state-of-the-art military weaponry, and other supplies. Police reports indicated that as the Philippine Constabulary unloaded the cargo, elements of the New People’s Army attacked them, but were fired upon. NPA guerrillas retreated in disarray. Primitivo Mijares, Marcos’ former pressman, would reveal that these “NPAs” were actually members of the Presidential Guard Battalion charged with “planting” ammunitions in Palanan to frame the Communists.

As the bomb scare spread throughout Metro Manila, an undetonated bomb was found hidden in the Senate Publications Division in the Legislative Building on July 18, causing the congressional sessions to be suspended for the day until the place was snooped clean. Nobody knows if the bomb was intended to explode or just to intimidate, but it was clear that not just the building but Congress as an institution itself was under attack.

*Front page cover editorial cartoon of the Philippines Free Press, July 1972. It is one of the few media outlets that warned the public of the possibility of Martial Law.

In one of the most insightful articles predicting how Marcos would implement Martial Law, the Philippines Free Press released an editorial entitled “Military rule next?” dated July 22, 1972. It reads:

Marcos could remain in Malacañang as President–after the suspension of elections under martial law–only if he turned bandit and if the Armed Forces of the Philippines should join him in banditry. He could remain in power only by violating the Constitution under which he declared martial law and if the military supported him in his criminal act […] Martial law should not be declared at all in the first place, not under present conditions, if the purpose were not to junk the Constitution–after invoking it to justify the declaration of martial law–establish a dictatorship. There is no good and sensible reason for the declaration of martial law, whatever, the Supreme Court may say to the contrary, but that does not mean that martial law will not be declared. Then it will be goodbye Constitution, hail dictatorship.

A week later, at night, unidentified men on a jeepney tossed bombs at the Tabacalera Cigar & Cigarette Factory at Marquez de Comillas, Manila. This was followed by the PLDT Exchange bombing at East Avenue, and Philippine Sugar Institute at North Avenue, Quezon City, both on August 15.

As the bombings intensified, Marcos secretly met with Defense Secretary Enrile and the top brass of the military, where he told them that he planned to declare Martial Law within the next two months. The fact that they discussed on the tentative dates to implement it, meant that the declaration was not at all in reaction to or dependent on premeditated threats to the State, but rather predetermined in its execution. Due to President Marcos’ knack for numerology, the tentative dates chosen were either in sevens or numbers divisible by seven. President Marcos took a liking of the date, September 21.

In the afternoon of August 18, a portion of the Department of Social Welfare building in Sampaloc, Manila was destroyed by explosives. Two days after, the water main on Aurora Boulevard and Madison Avenue was destroyed by a plastic bomb. Witnesses saw suspected bombers escaping via a bantam car. On the 30th, for the second time, Philam Life Building was bombed, and 15 minutes after, several buildings lined up in the Railroad St., Port Area, Manila.

By September, the bombings became more and more frequent. Joe’s Department Store in Carriedo, the Manila City Hall, San Miguel Corporation in Makati, and San Juan water mains, were the casualties. Meanwhile, an undetonated homemade explosive was found at the escalator on the ground floor of the Good Earth Emporium, near Joe’s in Carriedo. The bomb was a small bar of soap with a timer, 3 matchsticks, and a blasting cap.

In the ConCon, the “Ban Marcos” resolution gained a fever-pitched momentum. Delegate Augusto Espiritu suggested to Convention President Diosdado Macapagal to either “freeze the ball” and slow down the Convention proceedings so as to move the Constitutional plebiscite further back after the expiration of Marcos’ term, effectively banning him to join the Parliament, or “declare a recess until January 1974.” Espiritu writes on his diary:

For some delegates, the point is, the ban-dynasty provision has already failed anyway; Marcos would surely win. Therefore, we might just as well postpone the election and hold over the positions of elective officials. The bonus is that we, the delegates, would be there in the first parliament.

Unknown to Espiritu and the delegates in favor of the anti-dynasty provision in the draft Constitution, Marcos was already a few steps ahead of them. Marcos had many people within the convention who would resist the delaying tactic of the opposing delegates. And even if the delays work, Marcos never planned to wait for the Convention to adjourn. Under martial law, whether by intimidation or coercion, the delegates would give in to Malacañang’s pressure, and the plebiscite would follow suit.

On the night of September 11, 1972, President Marcos’s birthday, there was a massive blackout in Metro Manila, caused by the bombing of three undocumented power company substations. Interestingly, this was one bombing incident that would not be cited in Marcos’s proclamation of Martial Law. Having planned the philosophical bedrock (“Bagong Lipunan”) of martial law to rally the people to support it by means of cultural influence, and having finished all its legal papers lest Martial Law be challenged in the Supreme Court, Marcos sat comfortably in his study room in the Palace that night, and writes on his diary:

It is now my birthday. I am 55. And I feel more physically and mentally robust than in the past decade and have acquired valuable experience to boot.

Energy and wisdom, ‘the philosopher’s heaven.”

Ever a Narcissus in his own eyes, the Philippine president beamed proudly at his accomplishment.

*President Ferdinand Marcos’s desk as displayed now in the Presidential Museum and Library.

The Road to Martial Law is a series of blog posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The Road so far:

- It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

- Marcos Beginnings

- Truth or Dare?: Marcos during WWII

- The Turbulent ‘60s and Marcos’ Ascent to Power

- The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the ‘60s

- The First Quarter Storm of 1970: The Philippines on the Brink

- A Plan for the Endgame: Plots, Protests, Scandals and Assassinations

- Pawns in Cities lobbed with Bombs: Events leading to the Plaza Miranda Bombing

Photo above: Free Press editorial cartoon, August 1972. Courtesy of the Malacañang archives.

Bibliography

Bonner, Raymond. Waltzing with a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy. New York: Times Books, 1987.

De Quiros, Conrado. Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy. Pasig City: Foundation for Worldwide People’s Power, Inc., 1997.

Editorial, “Constitutional Convention or Malacañang Kennel?” Philippines Free Press, January 30, 1971, link.

Espiritu, Augusto Caesar, “September 7, 1972”, Philippine Diary Project, link.

G.R. No. L-35149, June 23, 1988, Eduardo Quintero vs. The National Bureau of Investigation.

Martinez, Manuel. The Grand Collision: Aquino vs. Marcos. Quezon City: M. F. Martinez, 1987.

Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. San Francisco: Union Square Publications, 1976.

Rempel, William. Delusions of a Dictator: The Mind of Marcos as Revealed in His Secret Diaries. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1993.

Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Press, Inc., 1990.

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

@kathnappy: I heard from an insider info that people from davao are indeed abusing their so-called power since it’s the president’s hometown. They greedily want all budget for davao, leaving other provinces in Mindanao striving. Ironic how he vows to end corruption but it is happening in his town.

Sorry for the late reply btw. But that’s true. I am from Cagayan de Oro and many of the people back there regret voting for Duterte, mostly because it gave Davao a free pass to bully the other cities and municipalities of Mindanao.

Davao is so quick to call themselves the most livable city ever when in fact, they can’t even keep the terrorists out and they fought the terrorists with islamophobia (wearing the hijab is now banned in Davao malls). Not to mention it’s always been a hotbed of EJKs, from the pre-Duterte days until today.

In fact, CDO is far more peaceful than Davao despite the fact that we’re close to Davao in terms of the degree of urbanization. You never see EJKs here, you don’t see terrorists being able to roam around freely here. Oh also, we don’t enable rice smugglers and we don’t blame all Muslims for what Abu Sayyaf does to Mindanao. We know that even Muslims themselves hate Abu Sayyaf.

Not to mention that our mayors actually care about us, they put us first, yes, even Emano (although personally, I’m happy he stopped being our mayor, we were so fed up with him during the last years of his term as mayor) - they don’t become mayors simply because they want to overfeed their starving egos.

In fact, if Davao City were to be partitioned, the northern part should be given to Region 10 and the Bukidnon province - they deserve it for so many reasons such as the fact that people from that part of Davao have a culture closer to Region 10 than to the Davao region itself.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching yesterday’s hearing in the House of Representatives is like watching a circus. A bizzare spectacle with whack characters.

The freak show led by Secretary of Justice Aguirre who, while wearing his toupee, presented convicted drug personalities as credible witnesses before the congress. The congress with its hall filled with politicians who, with greed written on their faces and shining in their eyes, jumped ship after the national elections. Sycophants who are so eager to lick the President’s balls and suck his ass. A funny caricature of crocodiles posing as men and women dressed immaculately while intently listening to the tall tales spun.

A convicted druglord saying he recognized De Lima’s voice because he was watching her on TV and he can’t possibly be wrong because that’s the same voice he talked to once — in 2014 using another person’s phone.

Another zealous incarcerated witness claiming there were multiple transactions involving millions and millions of peso but cannot provide any hard evidence.

Nowhere are the receipts nor ledgers. Just words. Words of criminals who made lying a way of living.

And the DOJ secretary, like his President, expects the clueless citizenry to keep on eating up the shit they served. And like the sheep they are, they do. Amazed and in awe of their great Duterte. Applauding and cheering without an ounce of doubt.

Preposterous doesn’t even begin to cover it. Ridiculous is not enough to describe it.

If you are going to sell lies, atleast make it believable. And a little less obvious.

0 notes

Text

I wonder if there'll ever be the day when Duterte's personal damage control team can get their act straight. Like, if there is some major news, they can agree to one version of the story and stick to it. God knows they have been struggling for quite some time now. Abela will say one thing, only to be contradicted by a different story from Andanar. And on the next room, Yasay is relating another version of what happened. All the while, Panelo has a disparate narrative. Kinda exhausting if you ask me. But what is more frustrating are Duterte's supporters who are willingly lapping up this circus of misinformation. Not only that, they are also tirelessly making excuses for their dearest leader.

0 notes

Text

"The reason is that I do not like the Americans."

Well hell, even if the All-mighty Duterte does not like the Americans, he can't deny the fact that the Philippines' relation with the Americans has been beneficial for us, the Filipino people. Duterte is the prime example of those government official who would put the highest priority to his personal need and gratification over the good of the nation which he promised to serve. Remember last May, when he said he will not give a cabinet post to Leni Robredo because Bongbong was his friend and because it will hurt Bongbong's feelings? Yikes. How has his actions pre and post ASEAN conference been beneficial to us? P.S. Duterte also said he had a one-on-one meeting with Putin in the ASEAN Summit. But guess what, Putin was not in the summit, it was actually the Russian President Dmitry Medmedev who was there. Talk about someone not getting his facts straight. But it's been the norm for him ever since he was sworn into office. Source: http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/814802/duterte-purposely-skipped-us-asean-summit

1 note

·

View note

Text

Now, can we talk about Federalism?

Rodrigo Duterte won in a landslide in the 2016 bringing about the message of change. Recent news about his 8 Point Economic Agenda which is nothing different from “Aquinomics”, but what he’s really planning to change is the entire economic and political system of the country if he will be successful. Duterte before deciding to run for the presidency last year is already advocating Federalism by touring forums around the country. I think this stems from Duterte’s frustration on “Imperial Manila’s” interference on Local Affairs.

I think this is not the first time Federalism as a form of government for the Philippines was proposed, but the latest was 2008 by Senator Nene Pimentel. In his plan, The country will be divided into 11 Federal States + a Federal District.

Metro Manila will become a Federal District like Washington, D.C.

Ilocos, CAR and Cagayan Valley will become Northern Luzon

Central Luzon

CALABARZON

Bicol

MinPaRom (In the Federal Setup, Palawan is geared more towards Visayas)

Western Visayas

Central Visayas

Eastern Visayas

Northern Mindanao (Northern Mindanao + Zamboanga+Caraga)

Southern Mindanao (Davao + Socsargen)

Bangsamoro

A Federal System of Government is Different from the current system we have where the National Goverment has vast powers and little to the regions. The provinces remit the taxes to the central government, and the central government will appropriate the taxes to the provinces through a legislated budget.

The Federal System will have less interference from the National (Federal Government), it has it’s own local, executive and judicial bodies, and as well as State Constitutions. Acting more independent from the National government, it could enact its own laws, budget, taxation as long as it doesn’t conflict with the Federal Laws, which is the more supreme law of the Nation. The National Government now becomes the Federal Government, and will be only have exclusive jurisdictions on some things like Foreign Policy, National Defense among others. Countries with this set up are Unites States, Malaysia and Australia.

The federal system is one thing that is being offered to secessionist groups, the same is also happening to Myanmar, where a Federal Form of Government is being offered to the rebel groups. A shift to the Federal Form will also entail amending the 1987 Constitution.

Duterte’s Federalism concept was vague in the start, but seeing that Pimentel and Duterte come from the same party, it is possible that this is the direction we’re all heading to. But I still have reservations on fully supporting this. (Please read Sen. Nene Pimentel’s presentation on the Federal Proposal here: https://www.scribd.com/doc/4969949/Federalism-Presentation-of-Aquilino-Pimentel-Jr)

My questions on the Federal Proposal:

How can we be sure that the assignments of the States will be acceptable to the residents? For example, are Region I, II and CAR better of combined as a single state or different states on their own?

On the start of the Federal Shift, some states will be more developed than the others, how can we be sure that more developed States will contribute in developing the other States so they can catch up?

Is the government still is a Presidential or Parliamentary?

POLITICAL DYNASTIES. There is a fear that Federalizing the country will further entrench political dynasties, so How can we be sure that aside from dismantling Imperial Manila’s economic and political control, we are also dismantling dynasties?

Power sharing between State and Federal Governments, How?

Can we afford and actually implement the shift? Remember that new units of government (State Government) will be established, provincial government downwards will be retained.

Duterte is betting his political capital in the first half of his presidency to change the political system. So I think, even before the proclamation, this one should also be already talked about in the open. What’s your take on the possible shift?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The death toll in this campaign does not equal success. It will never be a success unless the government addresses the real problems.

People are not poor because they use drugs. People turn to drugs because they are poor.

Plus, does the government even have a solid rehabilitation program for these people? The only options provided to those users that had surrendered are either:

A. Be thrown in overwhelmingly packed prison so they can pray to God for the strength to drop their addiction. Or,

B. Be grilled by the police, their names and personal details taken only to be placed on a death list. They will be sent home and maybe give it a week or two, be shot dead. Sometimes by police in a “buy-bust operation,” sometimes by unknown men riding a motorbike in tandem.

But say, by some miracle, these people are actually able to quit without medical intervention? What happens next? What happens after these drug users get out of prison? If they want to prove the success of this “War on Drugs,” the government better make sure they have jobs available for these people lest they return to their old habits.

And what if it’s option B? What about the children of those people killed in this war? What happens to them? If they don’t get proper support and education, then they will most probably grow up to have just the same fate as their parents, no?

It will be an endless cycle.

Or is the government just going to kill off these kids as well? Like Althea Barbon? The 4 year old girl who was callously called a “collateral damage” by the police. She was caught in the crossfire because the police did not see her. Is that also the reason why congressmen are pushing for this law wherein kids as young as 9 years old can be punishable by law?

I’ve always said that people shouldn’t blame everything on the government, that a person should be reponsible for one’s self. That still holds true but it’s not a one way street. The government still a has responsibility to its people to keep them safe and ensure their basic well-being. After all, that’s what we carry the burden of paying taxes for.

This “War on Drugs” is a just sham. It’s just taking the easy way out. The President and his cronies would rather see these people who had lost hope in life dead than think of ways on how to improve their living conditions and actually help them.

It’s not doing anyone a favor. Except maybe Duterte’s ego. It’s now so bloated with so much hot air.

1 note

·

View note

Text

PNP Starter Pack for reaching quota of 1.8M drug users in 6 months: - Packets of shabu - "Drug" money - .38 caliber revolver Optional: - Grenade

0 notes

Text

Criticism is always a good thing. It forces all of us to reflect and improve, otherwise people become complacent, and satisfied with mediocrity, and that marks the start of a backward slide.

Duterte, and his decidedly uneducated followers, have always set low standards and therefore try to reduce others to their level, rather than try to rise above the gutter. Their anger is a mask for their inferiority complex, their vulgarity a shield to deflect debate, and their cult mentality reflects a need to belong, to anything which will have them. An ‘us vs them’ mentality born out of playing the victim and failing in life. A narrow-minded outlook which is both myopic and delusional – the drained brain brigade.

In his first test of leadership Duterte has come up short, and exposed his limitations of simply being an autocratic mayor of a provincial town, and his own inability to rise up to the level of a presidential leader of a nation – he, and his alter egos, panicked, over-reacted, mis-communicated, mis-informed, micro-managed, and then went silent.

Leadership demands more than just insults and whims.

Duterte is starting to look like a relic from a bygone era, chained to the past with no understanding of the present, let alone a concrete plan for the future. Old men always want to relive their youth, which is why they are so out of touch.

0 notes

Quote

The Philippine culture is a uniquely indigenous culture that has been neglected for aeons because the colonization of these people distorted their culture enough to that it is almost unrecognizable in the modern world. What the Philippines is missing is a sense of legacy and pride in their uniqueness. Instead, the people have fallen under the spell of the Western world, and their priorities and goals are a hollow echo of the old, outmoded values of Western civilization. The Filipino people are starved for an identity that goes beyond Spain and America. They don’t want to be some other stepchild. They deserve to claim their inheritance… Having been colonized for so long, we have to rediscover ourselves. European culture is the legacy of kings and the commerce of merchant bankers. Our own culture has been suppressed by centuries of colonial subjugation, and that cannot be achieved without restoring to our people the pride of identity.

Way of the Ancient Healer: Sacred Teachings from the Philippine Ancestral Traditions (via wlnghya)

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Truth or Dare?

War brings out the best and the worst in people. This was true for all Filipino families that lived through the Japanese Occupation in the Philippines that lasted from January 1942 to September 1945. The traumatizing part of the war, perhaps, aside from the ghastly human atrocities and desperation caused by famine was the breakdown of trust among fellow Filipinos. Amidst death and conflict, it was hard not to see the complexity of everything in black and white–Filipinos versus invaders, American defenders versus Japanese “butchers”, Filipino guerrillas versus Filipino “kolaborator” (collaborator). Of course, each person then had reasons for doing what they did–whether for survival, for security, or for freedom.

This was true in the case of the Marcoses.

It was said, according to the Marcos-authorized Marcos of the Philippines by Hartzell Spence, that before the Japanese invasion, President Manuel L. Quezon offered Marcos the post of Chief Prosecutor in the Department of Investigation after he won in the Nalundasan case. Quezon was quoted as saying “You are on the threshold of an astounding career, if I am any judge… You are the most famous young man in this country. You can capitalize on that to catapult yourself into a political career.” Marcos turned down the opportunity, and preferred instead the practice of law with his uncle Pio and father Mariano.

When war came to the Philippines, Marcos was already drafted into service under the Philippine Constabulary. He fought in the Battle of Bataan as records indeed show.

This is where Hartzell Spence’s biography of Marcos should be corroborated in the light of contesting evidences that contradict the book.

Spence’s said, as repeated again and again by Ferdinand Marcos in his speeches as president, that General Douglas MacArthur himself pinned on Marcos the Distinguished Service Cross. He was then subsequently awarded by the United States the Silver Star Medal for attacking…

“… a greatly superior enemy force which had captured the outposts and machine gun emplacements of the 1st Infantry in reserve, culminating in driving the enemy back who had infiltrated the bivouac. His coolness of conduct under fire, exemplary courage and utter disregard for his personal safety inspired the men under him to act like veteran soldiers.”

Moreover, Spence added that Marcos was conferred the U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor with the citation that hailed him for “extraordinary heroism and valor beyond the call of duty in suicidal actions against overwhelming enemy forces.” The citation as quoted in Spence’s book, continued:

“By his initiative, his example of extraordinary valor and heroism, courage and daring in fighting at the junction of the Salian River and the Abo-Abo River, he encouraged the demoralized men under him, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy and successfully blocking the Japanese 9th Infantry…”

With a short disclaimer though, Spence inserted:

“Had the papers not been lost in the last days of Bataan, Marcos would have been the only Filipino army officer to win the United States’ highest valor award in the Bataan campaign.”

The only problem was, these were all a sham.

From the main players of the war like Generals Douglas MacArthur, Jonathan Wainwright, or Maj. General Edward P. King–none of them ever mentioned Marcos in their memoirs nor in recorded interviews. They did not even hinted that there was a Filipino who garnered these military honors from the U.S. If ever this was a cover up, this doesn’t make sense. If Marcos indeed fought as he claimed, it was impossible not to be noticed by the USAFFE, which accorded honors to Filipino war firebrands like Jesus Villamor. What about these honors to Marcos not even being mentioned by the living veterans of the time? And yet the glaring silence of the records in the U.S. National Archives and Records on these supposed Marcos medals is telling.

Spence effectively laid out the Marcos version of the story: After the Bataan Death March, Marcos became a Prisoner of War in Camp O’Donnell. Josefa Marcos, Ferdinand’s mother, was said to have appealed for his release, and it was granted, upon having convinced the Japanese that Josefa too was Japanese based on her features. A hesitant Ferdinand came home, but a short while later, was taken again and moved in the dungeons of Fort Santiago for allegations of espionage. He would be tortured, beginning in the evening of August 4, 1942, and after days, Marcos would be released, on the condition that he would lead the Japanese to the hideouts of some guerrillas led by Vicente Umali. The Japanese contingent would be ambushed, and Marcos, rescued by none other than Umali. After this, Marcos established the Maharlika Guerrilla Unit (term based on the social status of free men/warriors during the Pre-Colonial Period) which was claimed by Marcos to have operated on clandestine and daring missions throughout the duration of the occupation, eventually being the Filipino guerrilla to have resumed contact with Gen. MacArthur and the Allied forces.

youtube

*Part of the Marcos propaganda film “Iginuhit ng Tadhana” (1965).

Again, historical primary sources say otherwise. Researcher Marie Vallejo through the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office (PVAO), have made almost all Filipino guerrilla files available online, thanks to her untiring efforts in scouring the archival materials in the United States. A file significant to our discussion which can be accessed online is the “Ang mga Maharlica” Grla Unit files, which contain only the names who were supposed members of the guerrilla unit, but upon close inspection were close allies of the Marcoses before the war. A significant number were also family members. Furthermore, the names were all from Ilocos Norte. The claim was submitted by Marcos to the U.S. Army in 1947, expecting for reparations money and veteran benefits. A short paragraph on the first page was the scathing judgment of the U.S. military, concluding that these records were “fraudulent” and “malicious.”

Moreover, as cited by Raissa Robles, survivors of the Japanese torture machine in Fort Santiago, like Conrado Agustin (whose memoir was approved by the Marcos administration itself), never even mentioned nor remembered Ferdinand Marcos being tortured there.

Ferdinand Marcos also told of how Mariano Marcos, the father, was “shunned” by the guerrillas and eventually tortured to death by the Japanese. And yet, records show that the guerrillas themselves were the ones who executed the man on March 8, 1945 for being a collaborator.

The Maharlika unit’s exploits in the Battle of Bessang Pass, the battle that ended the last Japanese foothold in the Philippines, was also put into question, not only by the silence of the documents and veterans, but also, when a credit given to an honored soldier would be unjustly taken by Marcos as his.

youtube

It must be remembered that during the Presidential Elections campaign in 1965, Marcos heavily relied on these claim to superhuman achievements as his own.

So was it all really a lie?

Not all. But seeing how convoluted this is, it’s hard to sift truth from lies.

How did he get away with it… for so long?

For one, the information we know now was not available then especially when Marcos won the presidential elections the first time in 1965. Another thing to consider is that, for most of the time war veterans preferred to be silent of their ordeal for the emotional scars they could never forget, while others remained silent (as was the case with the Rigor family) to cause no fuss. But memoirs are there for all of us to read, but unfortunately, they remain unread. Third, the audacity of Marcos is such that he was willing to muddle truth to achieve his aim–a true pragmatist. This truth-fused-with-myth was but part of this Marcos myth-making propaganda, a thing the Marcoses would excel in, especially during Martial Law.

As concluded by acclaimed The New Yorker journalist Raymond Bonner:

“It was all a monumental fraud, and Marcos was nothing if not daring in perpetuating it.”

The Road to Martial Law is a series of blog posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The Road so far:

-It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

-Marcos Beginnings

Bibliography

___. Why Ferdinand E. Marcos Should Not Be Buried at Libingan ng mga Bayani. Manila: National Historical Commission of the Philippines, 2016.

Ariate, Joel and Reyes, Miguel, “File No. 60: A Family Affair,” The Philippine Star, July 4, 2016, link.

Bonner, Raymond. Waltzing with the Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy. New York: Times Books, 1987.

Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. San Francisco: Union Square Publications, 1976.

Gerth, Jeff, “Marcos’s wartime role discredited in U.S. Files,” The New York Times, January 23, 1986, link.

Robles, Raissa. Marcos Martial Law: Never Again, Student Edition. Quezon City: Filipinos for a Better Philippines, Inc., 2016.

Smith, Robert Ross. The War in the Pacific: Triumph in the Philippines. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1991.

Spence, Hartzell. Marcos of the Philippines: A Biography. New York: The World Publishing Co., 1969.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is reminds me so much of those times when kids don't want to go to school so they pretend to be sick. Or when adults don't want to go to work so they make up excuses like personal emergencies and such. But since this is the President, and he doesn't want to go to Brunei, he came up with the best excuse not to go. Sadly, it involves 14 lives and 67 more. It's super effective though.

0 notes

Photo

This person is the media liaison officer of your dearest Duterte. If you read his post, you’ll notice he has similarities with his master. He also likes conspiracy theories and spouting accusations without presenting evidence. Please note that this person works closely with the President. So his way of thinking may be influenced by the President and vice-versa.

You can take it whichever way you like, he’s either good at his job for mongering confusion and panic to the witless public. Or just so dense as to come up with statements like these.

Why don’t we add a fifth while we’re at it then.

With the way Duterte has been idolizing Marcos, it’s not too unlikely that he is following the same pattern. If you ever bothered to read history, you’ll know of the Plaza Miranda bombing. You know, that time when Marcos had an undercover military personnel penetrate the Liberal Party’s rally to bomb them? But he blamed it on the communists and that lead to the suspension of Habeas Corpus. Or that time, when Marcos had Enrile plant explosives in his own car (which by the way, Enrile admitted to doing in his memoir) that lead to the declaration of Martial Law.

So, back to present day, we have the Davao bombing and the palace declaring State of Lawlessness on the entire nation. Mind you, not just Davao but the entire Philippines. Do you see the parallels? We can now surmise that the fifth group is Duterte and his cronies. It’s not too farfetched either, no?

And yes, I like conspiracy theories too. But I’m not in a position of power where I can impose my delusions on people.

0 notes