Writing advice from an editor's point of view. I have fun and even provide real information, too. You never know what you're going to get.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Link

There’s mayhem, there are highs, and there are lows. Read about the advantages and drawbacks of NaNoWriMo participation to see if it’s something you want to do.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

#dialogue #writingadvice #writingtips #writing #books #editing

0 notes

Photo

(via Should an Editor Fix Every Single Mistake?)

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

The Perils of Info Dumps and How to Avoid Them

Have you ever read a book and thought, Wow, that's a lot of information in one spot! Well, you may have been the victim of what we in the book industry like to call an info dump.

Information dumps can be as obvious as an entire paragraph describing someone's look or backstory; they can also be as subtle as a single line in dialogue. At its core, an information dump is when a writer puts it all out there, so to speak. All the information that's in their head has to go onto the paper somehow—or so they think.

But sometimes it's not that simple. Would you rather, as a reader, have every detail dictated to you, or is it more interesting to create a mental snapshot along the way as specifics are revealed? Sometimes it’s tedious to be spoon-fed.

How’s this for an info dump example?

Drew walks into a room. We've never met Drew before, and he is important to the person who is already in the room. An info dump would read something like this:

Drew walked into the room. Six foot two and lanky in build, he was wearing khaki pants and a blue dress shirt. His Italian loafers had a high gloss to them that could only be obtained by starting with Italian loafers in the first place. His hair, a deep chocolate brown, curled in tiny waves over his ears. His deep blue eyes peered over the tops of his silver-rimmed glasses, which were perched at the end of his nose as per his usual style.

Anna looked at him and remembered the first time they had met, on a day almost exactly opposite of today. It had been raining, she was trying to find her way to class, and another student had bumped into her, knocking her books out of her hand and onto the wet ground. Drew was there and they had bumped heads when they both bent down at the same time to pick up the books. Through the auburn strands of her own hair that were sticking to her heart-shaped face, she had noticed his full lips and his kind eyes instantly, along with the fact that he was carrying many of the same books she was. Or had been, anyway, before they had been dropped so unceremoniously to the ground. Their friendship was born that day out of clumsiness and laughter.

Now that, ladies and gentlemen, is what we call an info dump.

How to Determine the Information Your Readers Really Need

What's happening in this scene?

I almost can’t remember because we’ve diverted from it for so many words. As the reader, I’ll have to look back a paragraph or so just to remember where we were in the story.

Ah, yes, there it is. Drew walked in the door. That’s it. That’s all that happened so far.

Did we need to know in this scene how they met? Maybe, maybe not. Probably not. What we need to know is that Drew walked in and Anna was glad to see him for whatever reason. If the way they met is important, it can come into play naturally in a different part of the story. She can be reminiscing because of something else that triggered the memory, or a friend can ask how they met, or any number of things. But the moment Drew walks into the room is not the time to reveal the entire backstory.

It is also not the time to describe Drew from head to toe. There is nothing that disrupts the flow of a story more effectively than describing a character for no purpose other than that you want the reader to know what they look like. Do we really need to know that Drew is exactly six foot two? Probably not, unless it has something to do with the plot where his height is a factor in clearing him of criminal charges because the bank robber clocked in at five foot seven.

Do we need to know what he's wearing? Again, probably not, unless he is dressed inappropriately for the weather and that has something to do with the immediate scene, or if he only has one set of clothing. Again, it has to be part of the plot, and he's always recognizable by his khakis and blue dress shirt. If Anna is observing him and notes how attractive he happens to look in a dress shirt as opposed to his typical scruffy T-shirt, then maybe that's a good reason to include his clothing in a description. My sons always wear black—we’re a family of musicians, so black is actually the clothing color of choice for most of us—and our younger son joked once about how he was someday going to wear a pastel-colored shirt and tuck his long hair under a baseball cap to see if anyone would recognize him.

Another Common Method of Info Dumping

One of the most common types of info dump is when a character starts off by saying to another character, “Well, as you know . . .” If the character knows, then there is no purpose in telling the character that particular tidbit, solely for the reader’s benefit.

This is something worth examining. When the information benefits a character, such as “Timmy fell down the well!” then that is certainly not an info dump. But when two characters are talking at the kitchen table, for example, and Character A says, “Well, as you know, Timmy fell in the well and you took three days to find him because you couldn't understand what your dog was barking about,” then you're looking at an info dump.

Character B already knows that it took him three days to rescue poor Timmy because he had never learned to understand dog language. You can use this for effect without it being an info dump, like this:

“I can’t believe it took you three full days to get Timmy out of the well!” She glared at him over her coffee cup.

He rolled his eyes. “Sorry if I never took Barking As a Second Language lessons. And it’s not like Timmy is a real person. That dumb chew toy could have stayed lost in the well, and I would never have missed it.”

She knew he was right, but she felt that someone should stick up for the poor dog. “But Spot could tell you weren’t looking very hard. And it was his favorite. No wonder he wouldn’t stop barking at you.”

Here’s a helpful guideline for determining whether you’ve written an info dump or not:

If the information is for the benefit of a character, it's probably solid. If the information is there for the benefit of the reader only, it's probably an info dump.

We can look at specifics that follow this “Is It an Info Dump?” guideline:

If we’ve been told a character’s backstory, did we need to learn it so a previous scene makes sense, or as a “big reveal”—or does its removal have no impact on what is currently happening?

When a character has been introduced, is there anything still left to learn about their physcial description and personality as the story progresses?

Are we repeatedly being told what each character is wearing when the scene changes, and if so, is it relevant to that scene?

If you imagine you’re Character B, would you be rolling your eyes and saying, “I know! Why are you telling me what we both already know?” (Unless, of course, you’re in a detective novel, in which case reviewing What We Know is perfectly fine and even required.)

Could you build a diorama of any room in a character’s house, and is that house’s layout essential to the plot?

I think the most difficult part about avoiding the info dump is that as writers, you have a lot going on inside your head. But the reader doesn't need to know everything you know. I read something recently that advised writing up your character sketches, figuring out every detail about them, their likes and dislikes, whether they have a cute little mole on one butt cheek or a lisp that they've always been self-conscious about. Learn them inside and out, top to bottom.

And then don't tell your readers much more than 1% of that. They simply don't need to know.

What If I Just HAVE to Tell Someone?

If you’re a writer who is also a blogger, you can flush out those details by giving your readers a sneak peek into someone's quirks or physical attributes without having to write all of that into the story. Look at all the “extras” J.K. Rowling doled out, bit by bit, long after the Harry Potter series was completed.

Creating a character or even an entire world is a great accomplishment. And you are allowed to love the rich descriptions of your characters, or the house they live in, or their car, or whatever you're describing in all its minor detail, down to the grain of wood on their dining room table. However, if all those things don't have anything to do with furthering your story, then you can love them all you want; nobody is stopping you.

But your reader doesn't need to know those things to enjoy the story as written, so keep the rest of it to yourself. Let us fill in the blanks. It’s why we love to read, after all.

Follow my blog with Bloglovin’

0 notes

Text

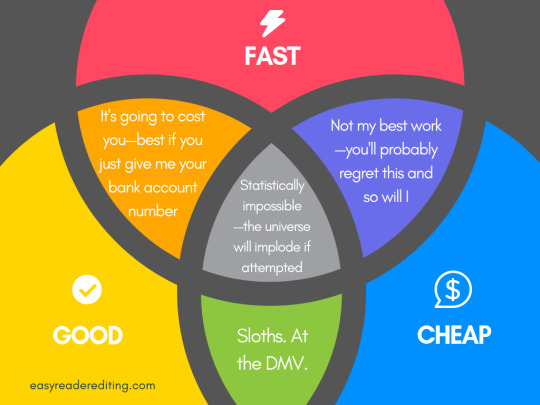

Good, Fast, Cheap—Choose Any Two

There’s a reason for the saying “Good, fast, or cheap. Choose any two.” It’s simple truth combined with grade school math and maybe a teeny bit of physics.

I get it. Most of us are not independently wealthy.

Everyone’s busy and in a hurry. Nobody wants garbage quality.

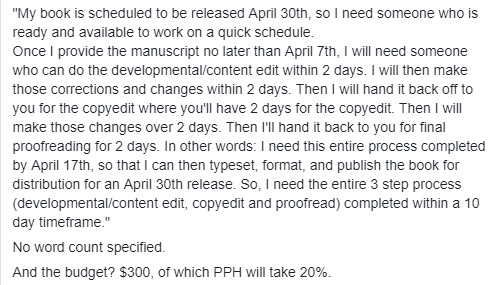

But you may be surprised to know how many people somehow expect high quality at a bargain basement price, all within a week’s time. Consider this post on a UK-based site called PeoplePerHour recently (the portion in quotes is the actual post):

What’s Your Hurry?

I’ve often wondered what compels someone to rush the publishing process. Oh, I understand excitement as well as anyone. After all, I can barely wait until Christmas Day to give someone their gifts, especially if I’ve already wrapped them. But if you’ve spent hours, days, weeks, months, often YEARS writing and rewriting your book, why would you hurry through the final steps that make it shine?

Better yet, why would you want someone else to race through that final bit of TLC on your manuscript baby? There’s a reason for the old saying “haste makes waste.” Rushing any project—whether it’s writing a book, painting your house, or baking a fancy dessert—rarely yields the best results.

But What About the People Who Tell Me I Can Have It All?

A little plain talk here: they’re lying. No kidding. I don’t say this to discourage you, and I don’t say it so you’ll hire me and not the ever-present “them.”

I say this because it’s a truth that has been proven time and time again. The internet is full of people who promise everything for nothing in no time flat. “I can edit your book for $50!” “Super-quick edits for a super-low price!” The list goes on.

How Fast Can I Get It Done?

Editing a manuscript is nothing like sitting in your favorite chair to read for pleasure. Book revisions take time. Copyediting takes time. Proofreading takes time.

An average-quality fiction manuscript (in pretty decent shape, good grammar for the most part, easy-to-follow plot) allows me to read about 5000 words per hour. If it’s extremely clean with minimum intrusion on my part, I can often manage 8000–10,000 words per hour. Nonfiction manuscripts typically move slower (about 2/3 the speed of fiction), because there are often footnotes or endnotes to check and standardize, references to verify, fact-checking and more, but you get the idea.

Conversely, a manuscript that’s a little rougher around the edges can slow me down to about 2000–3000 words per hour. I’ve copyedited novels that needed so much line editing that I slowed to a crawl of barely 1000 words per hour.

Using our middle school math skills, if a train carrying an average manuscript of an average length is traveling due east at an average speed, and the editor is traveling due west . . . oh, wait. There are no trains. Just my desk and computer. All right, then. Mathematics will still tell me that an average-length manuscript will take about 50–80 hours of work on my part, with two rounds of editing.

What’s It Going to Cost Me?

I cringe when I see the “Any Length Manuscript Edited for $100” advertisements listed on places like Fiverr, Goodreads, Elance, and other race-to-the-bottom job-bidding sites. I liken that to a car mechanic—without ever seeing the car or finding out what may be wrong—telling someone that their repair will cost $100.

The fact is that there are too many variables (quality of writing, manuscript length, genre) that determine the estimated cost. One of those variables ends up being the time involved. As I mentioned above, it takes quite a few hours to go through a manuscript for copyediting, and most editors provide two passes of edits. Work time is valuable, and editors of all types provide a skill set that has value.

Let’s say you find a job you enjoy. Your boss tells you that you’ll be paid $100 for two weeks’ worth of work. Hmm. Maybe you’ve fallen on hard times and really need the money, so you agree. One hundred dollars sounds like a lot, right? Except that when 80 hours of work has been put into the job, you realize you’re only earning $1.25 an hour, and it will take you roughly 70 hours of work at that rate to pay your electric bill for the month, and only if there’s a fluke in payroll and they don’t withhold any taxes. Heck, it will take you at least 20 of those hours to afford a small handful of fruits and vegetables so you can keep up your strength.

Everyone wants a living wage, even copyeditors. The total cost for your book edit will reflect fair compensation for the hours spent.

I’ll Need This Completed in Two Days, Thank You

There are times, as the old FedEx ad used to say, when it “absolutely, positively has to be there overnight.” Maybe someone dropped the ball along the way and now you’re behind schedule. Maybe you’re a poor planner.

Maybe your dog got sick and your beta readers were late and your typesetter is already booked for next week and you regret that crazy moment when you thought you would have had the book finalized already and told everyone to preorder because it would be available BY THIS DATE and now you have very little time for the actual editing process.

It happens.

The problem with making your schedule someone else’s problem (because let’s be frank: that’s exactly what is happening) is that you’re taking time that they may have had planned for something else. Do they need to set aside someone else’s project for a day or two so yours can be the priority? Do they have to work over the weekend, or late into the evening when they typically keep weekday/daytime office hours? Do they have to hire a babysitter because they’ll need to lock themselves in their home office with earplugs and a “DO NOT DISTURB” sign?

Well, you can probably find someone to do the job quickly for you in a pinch, but it’ll cost you. It’s called a “rush fee” for a reason. And the thing about having someone hurry for you is that you need to hire someone who’s exceptional at what they do, so you know the quick action doesn’t leave you with a lack of quality.

Sometimes the speed can be accomplished only by compromising on what gets done. Maybe there’s only time for a single pass. Errors may be missed, but it’s better than nothing. Or perhaps the editor can go through it for typos and punctuation but not sentence structure. Either way, something has to give.

The Bottom Line

What it all boils down to is this: plan ahead for an experienced and recommended editor, save your money for quality work, and allow for enough time to get the job done well. Miracles happen, but never on demand.

Follow my blog with Bloglovin’

0 notes

Text

Anachronisms: Timing Is Everything

Fiction writers create worlds we can immerse ourselves in. They often create entire universes that are nothing like the known world, allowing us to imagine "what if?" as we read.

There’s Always a “But”

But fiction that's set in our own world—current-day, ancient history, or somewhere between—needs to make sense within the boundaries of that world. We would no sooner give Cleopatra a can of Coca-Cola than we would have Columbus crossing the seas on an ocean liner.

Some items are a little more subtle, though, and that's where it pays to do your research. A book I read years ago was set in medieval times, but the little children were amusing themselves by making parchment paper airplanes. I read another where the main character slammed her cell phone shut in anger—too bad it had already been mentioned that she had a smart phone, which was (even then) a far cry from the early flip phones . . . and with nothing to shut.

This type of slip-up is called an anachronism, "an error in chronology," according to Merriam-Webster's dictionary—something that's out of place because it's out of time.

At best, goof-ups like this will cause readers to leave scathing remarks in their reviews. It's frustrating to be pulled from the fictional world by typos, bad grammar, and the like. It's even more frustrating when the created world that's surrounding you is ripped away like cardboard walls on a theater set.

It Only Takes a Moment to Fact-Check

At worst, though, lack of research on the writer's part just might make the decision for an acquisitions editor as to whether a manuscript gets a deeper look or the slush pile. I recently read a post from someone who evaluates self-published books for an industry publication to determine whether they will be considered for review. He said one book looked promising and had a nice cover, so he read the preview on Amazon, hoping to give the book a good shot at a helpful industry review. However, in the first three pages of the book, there was a scene in which a character screamed for someone to get an epi-pen. The scene was set in 1979, and the evaluator took about 30 seconds of Googling to determine that epi-pens did not come to the market until 1987. He said the way the scene played out, there was no epi-pen available anyway (in the story world), so the scene could have functioned just fine without that line. The result? Trash can for that book. The evaluator mentioned what a waste it was for that writer to sabotage their own sales, due to sloppiness.

I once edited a manuscript set in the present day in which a centuries-old character used a particular apparatus (and had, since medieval days) that wasn't invented until the early 1800s. I made sure to mention it to the author, because these things are important to the readers. Just because a world is being created doesn't mean real-life things can just appear wherever the author thinks they're cool. Even fiction needs to make sense, and simple fact-checking can make or break whether people will continue to read to the end of your book. Granted, there will always be those readers who don’t notice a thing, but the people who can propel your book to the next level will always notice because it’s their job to notice.

The Buck Stops Where?

Ultimately, research for accuracy falls to the author. After all, it’s their book and their responsibility to think through such things as what type of armor was used in the Middle Ages, the shooting distance of various handguns, clothing material most common in Ancient Egypt, food and cooking trends in the 1960s, and much more.

The editor has a responsibility as well. Yes, the author is first and last in this, but a decent editor does a lot of fact-checking along the way through a manuscript. During a recent memoir edit, I did so much looking up of places and names that my style sheet ended up with hundreds of entries on a multi-page spreadsheet. It was well worth the time, though, because I was reminded of something I learned in a copyediting class last year: just because it’s not a typo doesn’t mean it’s accurate. The memoir featured the first and last names of hundreds of people in the entertainment industry, both in the US and South Africa. And the internet is only as accurate as those who enter its data. Even some of the bigger names were spelled differently from website to journal article to social media page. Thank goodness, the author was still in contact with many of the people whose name spellings I needed to verify, and he happily provided anything I couldn’t find on my own. The best thing about it was that he was genuinely appreciative and impressed that I’d gone to so much trouble to get it right.

Don’t Stress—Just Do the Research

Movies are famous for having anachronisms that moviegoers revel in catching: the kilts worn in Braveheart, for example, that weren’t in use in Scotland until well after William Wallace’s time. Sometimes they’re used for cinematic effect, and other times, they’re not intentional at all.

In the literary world, even famous writers screw up now and then. William Shakespeare had quite a few anachronisms in his plays, including referring to a clock in Julius Caesar. Clocks were certainly not around in 44 AD—not clocks as we know them, anyway, capable of striking the hour in the manner that Cassius mentions in Act 2, scene 1 (“The clock has stricken three”). He didn’t have editors in the modern sense, but I don’t think his audience noticed or cared about his oopses anyway, since most of them were unable to read and most likely didn’t notice the errors when spoken in a live performance.

That’s not to say that today’s writers can use Shakespeare as their own “Get Out of Jail Free” card. We’re still responsible for publishing content that won’t make people put the book down in frustration.

The Obvious

Sometimes, anachronisms are so easy to spot that we can’t imagine how a writer or editor missed them. The parchment paper airplanes I mentioned earlier, for example. A book set in the early days of black & white television that refers to the onscreen vibrant colors on an actress’s evening gown. A reference to a bit of technology in a setting before it was actually invented.

Not So Obvious

Other times, the out-of-place-ness (yes, I just made that up, but I like it so I’m keeping it) can be a lot more subtle. Words and phrases in our everyday usage have morphed as the language has adapted. Using the word “fantastic” in a current-day novel would most likely imply that something is excellent or superlative, e.g. “That was a fantastic vacation spot!” But if your novel is set in, perhaps, the 1700s, a character who used the word would imply that something was unbelievable, not real, based on fantasy: a “fantastic” device or invention, such as those in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Improper usage of a word is as bad as having a character say a word that isn’t in use until decades after the novel’s setting.

Readers are particularly harsh with authors who place weapons in the wrong time period. Some are eagle-eyed enough to catch that certain clothing is “off” by decades. I once read a book that was set in the current day, but the anachronisms were more season-specific, such as football practice at the high school only a month or two before graduation in the spring, or harvesting particular fruits out of season for the region.

At its best, it’s irritating enough to pull the reader out of a story. At worst, it’s lazy writing, and no writer wants to be known for carelessness. If you can’t be bothered to put the effort into your book, why should the reader keep reading?

Follow my blog with Bloglovin

0 notes

Photo

Welcome To My New Blog Home!

After blogging on another site for the better part of six years, I realize it’s time for a change.

Why?

I don’t normally like change for change’s sake, but this seems like a good move. My website is here on Squarespace, but my blog has always been with Blogger. When I finally set up a website in 2018 after years of trying to make my blog do all the heavy lifting, I made the difficult decision to keep my blog where it was so I wouldn’t lose any of my consistent readers. But the recent changes from Google, like getting rid of Google+ (a good move, in my opinion), have automatically sliced my readership to a fraction of what it was. I can only speculate that the Blogger Reading List (similar to the WordPress Reader) will also go away in time, making it even more difficult for people to see my posts unless they follow me on other social media. Perhaps Blogger itself will disappear.

So . . .

I’m not waiting around for the other shoe to drop. It only makes sense to have my blog in the same place as my website.

I plan on continuing the same great content I’ve provided all along, whether I’m giving out tips for better writing, advice from an editor’s point of view, book recommendations to help you along your writing journey, or just plain silliness from time to time. I’ll also be moving some of my most recent blog posts over here, since many of them are part of a continuing series. I even have some surprises in store!

When?

The official move will happen on Thursday, April 4. My final Blogger post on March 21 will mark my 200th post there, so it’s a fitting time for change.

Here’s looking forward to a long and happy blogger/reader relationship.

1 note

·

View note