Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Back to the drawing board

Animation Notes: The Human Head part 1: preliminaries

Hi friends! Remember Animation Notes? Sure been a while. Well, let’s see if we can bring that fucker back, since I would like to level up my art and that means, more studies.

To begin with, I want to look into the question of drawing the human head - one of the few body parts I can be absolutely certain every single reader has! So let’s get started…

Here’s a still from Avatar: The Last Airbender, a Korean-animated show that in a sense functioned as a ‘sakuga awakening’ for me. In this shot, three villains have disguised themselves as members of a heroic faction called the Kyoshi Warriors who wear face paint and elaborate uniforms. Despite this, we can immediately tell all three characters apart from the familiar Kyoshi Warriors such as Suki, because the face models are just very subtly different.

This is the power level we need to be able to reach!

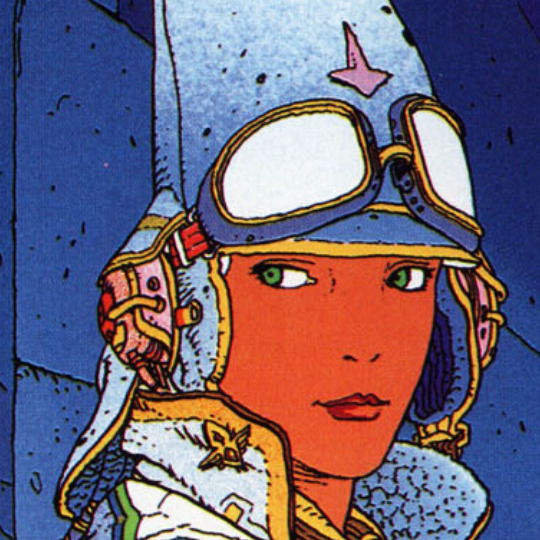

Human heads, and especially faces are really important. And as such, they’re really finicky. A minute difference in placement of a line can totally change the whole feeling of head. A particular illustrator’s way of drawing heads can act as a stylistic hallmark. For example, if I show you this picture…

I bet you could tell me at once that it’s by Moebius. Moebius was a very versatile artist who could draw a lot of different kinds of heads, but there are certain hallmarks here - the style of hatching with lines fading into dots, the fairly rounded circular shapes, and the shadow under the cheekbone. But mind you, here’s a crop of one of Moebius’s best-known pictures:

Here, he omits almost all shading on the face - just a little hatching under the chin - and avoids most lines altogether. Only the face contour and hints of line around the eyes, and the asymmetries in the eyes, lips and nose, tell you about the structure of the face. Despite this, the face feels unmistakably 3D.

At other times, particularly in his Western comics as ‘Gir’, Moebius would go for a really hyperdetailed style that’s just overloaded with hatching, as for example here on the cover of The Airtight Garage:

Here an enormous amount of detail in the face structure is shown: you can clearly see the major planes of the face, the wrinkles around the jaw, the shapes of the chin and nose and eyes. So you get the sense that this character is a sort of colonial masculine ideal like you might see in an old movie, a Lawrence of Arabia type of deal - an older authoritative man, who spends a lot of time outdoors. His expression feels thoughtful, perhaps a tad amused, but in a reserved way. All that from shapes and lines!

Moebius’s style might be considered a ‘realistic’ style, in that the proportions and anatomy closely correspond to what you might expect in photographic projection of a real person’s face, and he saves most of his stylisation for the rendering. (He wouldn’t always draw in this style, sometimes adopting a more schematic ligne claire style, but this is the one he’s most known for.)

In animation, it is rare to see this level of commitment to anatomical realism. But definitely not unheard of! The 90s anime ‘realist’ movement, documented in great detail by Matteo Watzky, had similar commitments. Per Watzky, a lot of the driving force behind what would become the ‘movie style’ in 90s anime, was prolific animation director Kazuchika Kise, who while working on the Patlabor films persuaded character designer Akemi Tokada to adopt a more realistic, less cute style compared to the original TV series - a perfect fit which became the standard in Oshii’s later films, particularly Ghost in the Shell.

Satoshi Kon is the other director who springs to mind on this front; I don’t have such clear info on the process for defining the look of Satoshi Kon’s films, but he was known for his meticulously detailed storyboards, and as early as Magnetic Rose you can see him working with the absolute best realist animators - notably distinct from the realism of Otomo, in terms of how subtly it handles its human characters. While Kon was not the primary character designer for all of his films - instead credits list Hisashi Eguchi (Perfect Blue), Masashi Ando (Paranoia Agent, Paprika), Kenichi Konishi (Tokyo Godfathers) - he is credited as a character designer on all of them and no doubt had a big influence on the style.

^ one of the many incredible shots from Magnetic Rose in the Memories anthology, where Kon is credited for writing and ‘setting’, but has been confirmed to have worked on layouts e.g. in this scene.

So ‘realism’ is one strand, and one of the most demanding. But this is not a post to talk about realism. If you want to learn to draw realistic heads there are many resources out there, and you’ll need to study photos as well. We’ll still talk about schemes for analysing the structure of a realistic head in a bit, since they’ll be relevant for the more abstract approaches.

But of course, the vast majority of the time, we’re actually abstracting away a lot of this anatomical precision for artistic effect. The prevailing style in American TV animation these days is to draw a head that’s basically two overlapping oval-like shapes, sort of like this:

The connection to face anatomy may seem very distant at this point, and yet we certainly see this as a face, and the simplicity allows the animators to push expressions a lot more - and don’t get me wrong, drawing a simple but precise shape consistently is not a simple feat either. On the other hand, it is such an abstract 2D shape that it is rare to see such characters standing in anything other than a ¾ view long shot facing the camera, which is a limit on shot composition.

We’ll cover a lot more examples soon, but let’s first of all cover some preliminaries!

The structure of a head

To draw anything from imagination, you have to have some kind of handle to simplify it. One of the most enduring approaches for drawing human heads is the ‘Loomis head’, defined by the widely influential American illustrator Andrew Loomis who wrote a series of widely referenced books on drawing up to his death in 1959.

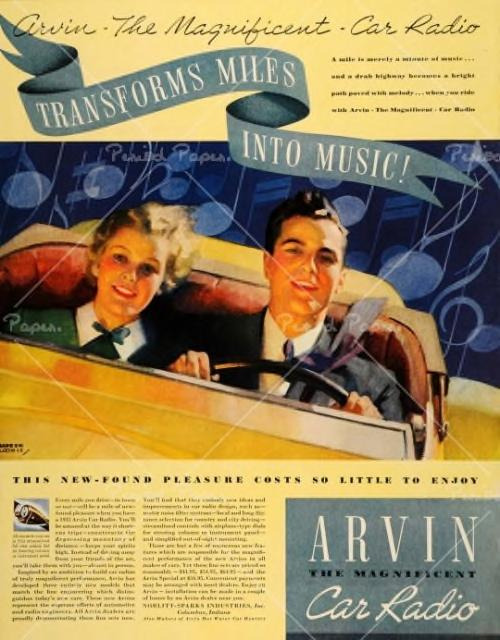

In his books, Loomis mentions selling commissioned portraits to families, and drawing for advertising. Back in the first half of the 20th century, colour photography did not exist, nor tools like photoshop, so adverts were almost always painted by illustrators like Loomis. I’m sure you know the type. Here’s one that Loomis painted which I got off the Internet Archive:

Loomis-sensei painted thousands of illustrations across his life, all in what can be described as a relatively ‘photorealistic’ style - although bear in mind that any ‘realist’ drawing still very much involves abstraction and simplification. Given the prevailing social forces in his time, Loomis’s illustrations almost all depict a lot of quite similar smartly dressed white people, in a variety of settings; that’s what he’ll teach you to draw. But that doesn’t mean his insights aren’t useful!

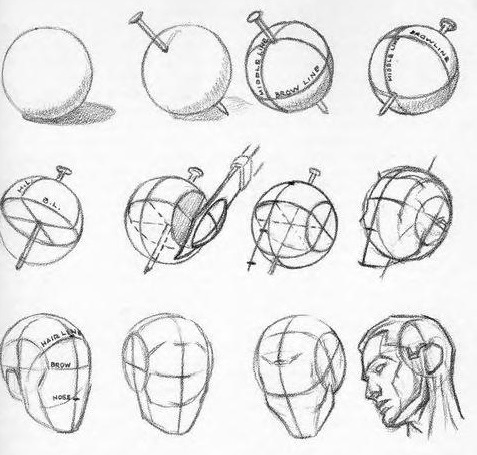

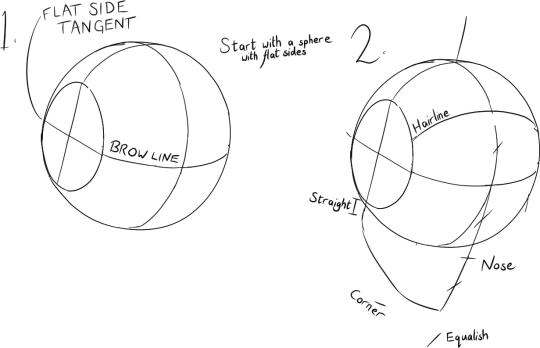

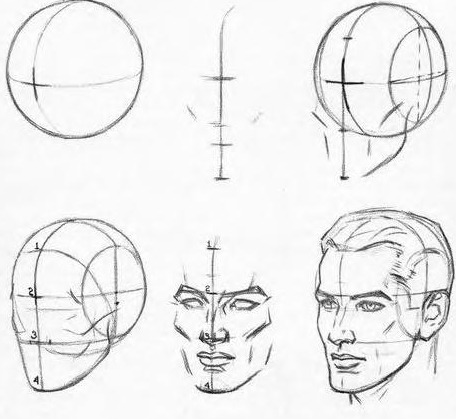

So, the ‘Loomis head’. This is a particular schematic approach to breaking down the head into a few simple 3D forms, which Loomis recommends as the starting point of any head drawing - he advises you on how you can vary the shape of the head by squashing it around, but that the relative proportions tend to be pretty similar. Here’s how he introduces it in Drawing the Head and Hands (1956):

You start with a sphere with the sides cut off, and make sure to mark the centre lines and brow line; the point where they cross indicates the direction of your head in 3D space. So let’s do some studies.

Actually drawing a circle freehand is the most fiddly part lol. I noticed that in Loomis’s pictures, the flattened side almost always touches the outer contour of the sphere at a tangent. Anyway, here’s my go:

From this cross, you drop down a vertical line, about twice as far as the distance from the brow line to the forehead. The centre of this line is the bottom of the nose. To the bottom of this line, you draw a line in three sections connecting to the bottom of the flattened side of the sphere. These sections are the chin, the bottom edge of the jaw, and the vertical part of the jaw connecting to the ear.

Next, you draw the cheek contour, which is a boundary between two planes. This connects to the brow line, but notably there’s a bit of a kink in it, which I believe indicates the cheekbone:

You can then place your features to get your classic 50s advert guy. Though I drew it pretty rough, I tried to follow Loomis’s choices of what lines to draw and how to stylise, with this ref in particular:

…though in my version the downwards tilt to the head and the slightly pouty lips make him feel like more like some kind of yaoi boy lol.

The cheek contour - more on that shortly - is made quite hollow, the more to emphasise the cheekbone itself. Inside the form of the face, Loomis seems to usually place a line indicating the transition from the front plane to the side plane of the head, again indicating the cheekbone.

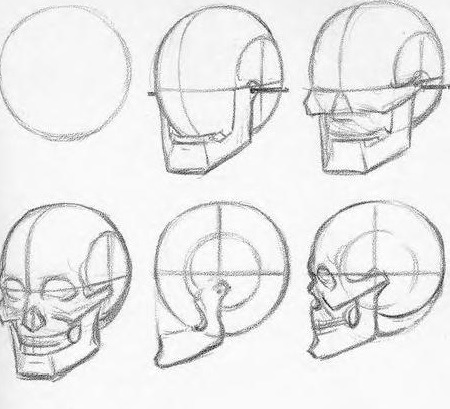

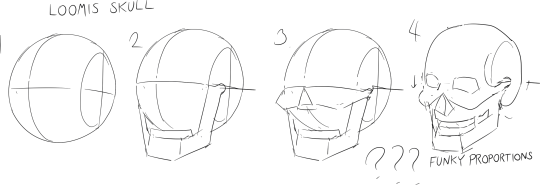

The great advantage of this method is that by breaking down the head into simple 3D forms, you can easily place it at any angle (modulo your skill at perspective drawing!) within the picture. The features that Loomis emphasises are mostly, he writes, features of the skull; he offers a method for drawing skulls as well:

I tried to follow it with somewhat less aesthetic results:

no doubt with practice i’d more reliably get the proportions right, but that would get us sidetracked.

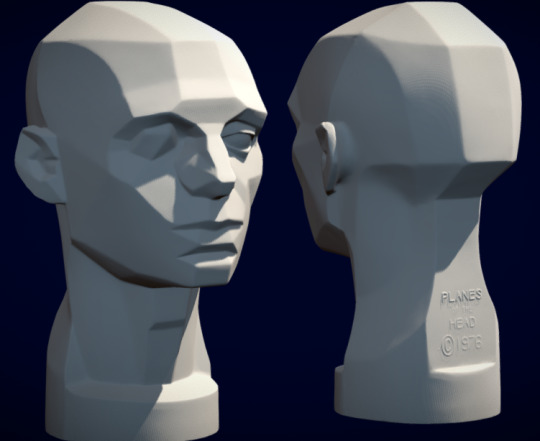

From this basic construction, Loomis elaborates considerably, asking us to look at the planes of the face with increasing detail, resembling the Asaro head:

and offering advice on how faces might be varied from the basic template, on applying perspective etc. I will definitely come back and do more Loomis studies down the line, but we’ll leave it at that for now.

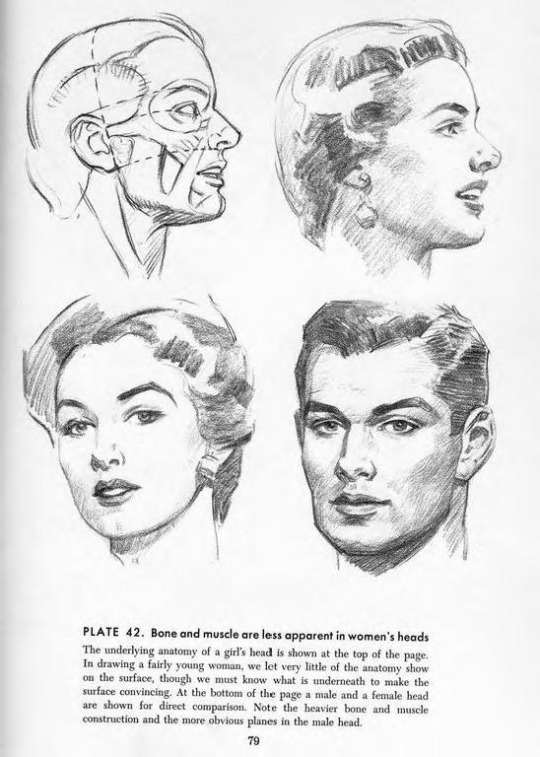

One other thing of note: after introducing men’s heads as the default, Loomis gives sections on womens’ and childrens’ heads. Gender divides are definitely emphasised in his work. In contrast to his male heads, Loomis advises you to eschew some of the planar structure he describes for men’s heads:

Nowadays the main reason to look at the Loomis head is not because you want to make a 1950s-style commercial illustration. Certainly, it’s useful for ‘realism’. But for our purposes, it’s also because a variant of this construction has ended up as the basis for a lot of standard designs used in anime.

For a more modern treatment of the Loomis technique, see Proko’s video:

youtube

In contrast to Loomis’s original method, Proko doesn’t have that small cheekbone kink in the line representing the plane change from the front to side plane of the face, nor the emphasis on the cross at the centre of the head as the starting point of the drawing. So don’t assume when someone says a ‘Loomis head’ they’re exactly going to use the method outlined above.

Other ways of breaking down the head

Loomis may have one of the simplest and most straightforward methods, but I would be remiss not to mention other important breakdowns.

The ‘Asaro head’ is a small plastic statue made in the 70s by John Asaro, widely used by painters as a way to break down the planes of the head for light and shadow. Here’s a render of a 3D scan of it:

With the Asaro head, we can really clearly see how the front planes of the face form a kind of inverted triangle, narrowing towards the chin, while the back of the jaw is of course much wider. While it’s useful to be aware of these plane changes, they’re mostly relevant at a later stage of the drawing, when we’re dealing with value - although we may choose to mark the plane changes with a line.

Then there’s the Reilly method, which is broadly less popular than the Loomis method, breaking down the head not into blocky 3D forms but a series of arcs and proportional measurements designed to find relationships between features of the face. This is named for another early-20th-century American illustrator and art teacher, Frank J. Reilly, who lived from 1906 to 1967. Here’s a video that breaks it down step by step:

youtube

Honestly, I’ve never tried using this method, it looks too cumbersome to be very useful most of the time. But I do feel like it might be useful to apply it at least a few times, to try to get an intuition for the information it gives about planes and structures.

The jaw/cheek contour

All well and good for painters, but let’s assume you are in a flat- [kagenashi] or cel-shaded style; then what does give your drawing structure?

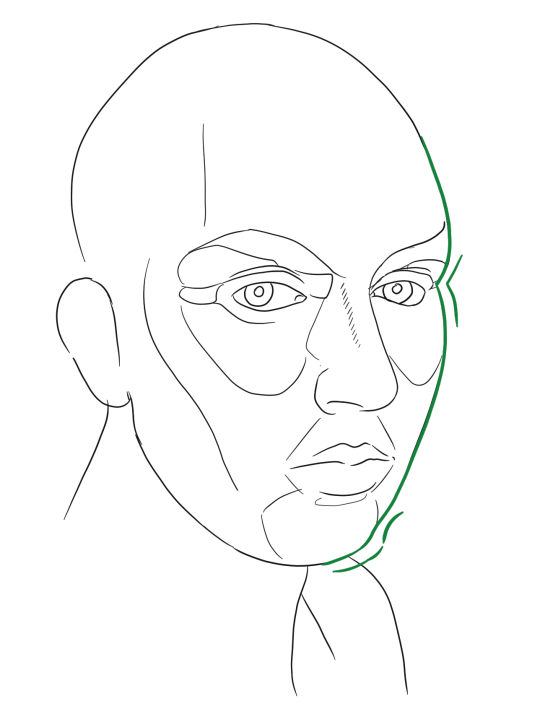

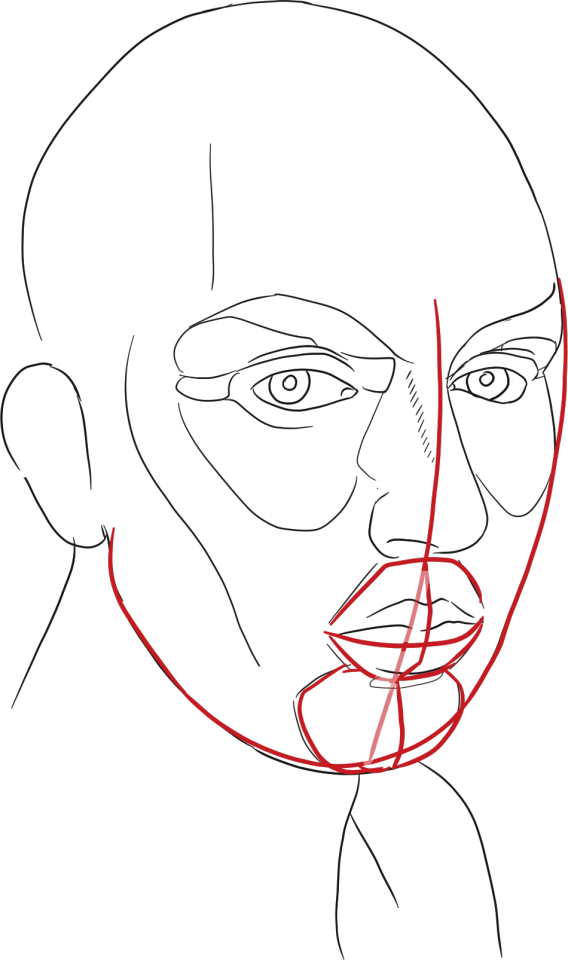

I’ve increasingly been inclined to see the contour of the face as being one of the most important parts of the drawing: the lumps and bumps there carry a lot of information. And this is also the path we’ll be taking towards more stylised heads.

Let’s start with realism, though. I took a photo of myself at a ¾ view and traced the major plane changes and structures:

That’s one uncanny looking picture, but let’s now take a look at the green line on its own:

I marked two important points. The first one is the indentation of the eye socket. Depending on angle and size of the eye, this may be less sharp.

The second is the chin bump. We can think of the chin and ‘muzzle’ of the mouth are smaller forms which poke out of the overall simple ‘Loomis head’ wedge shaped structure.

In the case of plumper cheeks, we can imagine a kind of ‘cheek bump’ as well, which has the effect of making a character look younger.

If we view the head at a more oblique angle, closer to a profile view, the bumps become more pronounced: the lips start to cross that contour line and the cheekbone becomes more evident. This time I’ve tried to indicate major plane changes with cross-contour hatching rather than lines, imitating Moebius a little.

Note that even though the lips don’t outright cross the contour line, the ‘muzzle’ does create a break in that contour line there.

Of course, there’s a lot more to it than that. The size and shape of the main features are also incredibly important, as is the approach taken to light and shadow. But when we start breaking down particular artists, particularly in anime, this concept of a contour line will be valuable I think - I certainly think about it a lot when drawing.

Next time: A survey of the diversity that exists within ‘anime style’, and an account of its stylistic evolution!

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

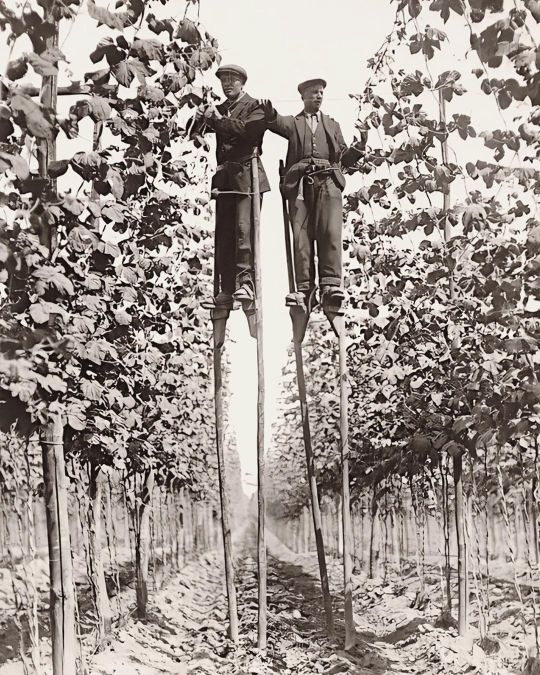

Proof these were made for giants

Hop pickers on stilts in Faversham England 1920

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

We are trapped in our situatedness. There are no foundations that are not themselves contingent from which to build a certain and agreed-upon body of knowledge. Knowledge really comes down to one’s perspective: we never really have the facts; there is only interpretation.

0 notes

Text

God sleeps in the rock, dreams in the plant, stirs in the animal, and awakens in the man.

0 notes

Text

Book Review: Murder on the Orient Express

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545; min-height: 14.0px} span.Apple-tab-span {white-space:pre}

Murder on the Orient Express

1934

Agatha Christie

Abstract:

Aristocrats use their wealth and power to break the law and kill a man who used his wealth and power to break the law and kill a girl.

Synopsis:

A murder happens on the Orient Express and is quickly solved due to a highly skilled detective who happened to be there and other strokes of bad luck for the criminals. The train is stopped by a blizzard and the passenger who is a reputable detective takes on the case at the request of the train director and assisted by a doctor. He uncovers the elaborate plot on the train car filled with conspirators of the Armstrong household. They all took turns in stabbing the victim to death in solidarity of vengeance for the alleged murder of their beloved family’s daughter. Caught between the lawful process and emotional appeal, the train director chooses to affirm the detective’s credible yet false theory that protects the bereaved family from any law enforcement outside the train.

Symbolism: Divine justice

There are three ways the murderer’s put themselves in the right: by having wealth, using charm, and campaigning their position.

Class segregation. The criminals are in the opulent first class coach with fine dining. This special treatment partitioned their kind of law, much like the cars that made up the train. The outside was locked off and irrelevant like the doors closed shut to the other passenger cars. It implies that their sense of justice is better than the public’s and their conviction can be the only option;

Barbarism behind beauty. The civilized formalities and social etiquette swoon the investigators. During the investigation, Poirot values scientific evidence as a detective but eventually dismisses reason for sympathy and intuition. Even though they all participated in stabbing someone to death, he took their side. His sentiment dismissed pertinent questions that were left unanswered. He relied only on the family’s word, the suspicious alias, and the man’s unlikeable appearance.

Appeal to the masses. The wealthy Armstrong household formed a unified front to uphold their baseless accusations. If the story wasn’t international news then there would be no use. They become petulant and emotional when their lies are uncovered during the investigation. Ratchett had to be Cassetto, and Cassetto had to be the dreadful kidnapper.

Allegory: the state and the people

The people. Ghandi was famous for saying, ”An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind." The Armstrong household circumvented due process for a vendetta—lex talionis They retaliate to his ransom notes by sending him threatening letters to grip him with fear in kind before drugging and stabbing him to death. Despite their immense wealth and means to perform a proper investigation to find solid evidence linking Ratchett to the kidnapping and murder. The household behaved as mobs do for lynching and witch hunts. They choose to bypass any of the lawful procedures for the sake of their unbridled revenge.

The state. The Poirot, M. Bouc, and Dr. Constantine valued evidence and procedure as they represented the law. However, the consensus is that Ratchett seems to be Cassetto and Cassetto slipped past the law. They knew that court and lawmakers are corruptible and fallible. Poirot is persuaded by the family and deems it best that one man rightly dies to make this family feel better for their international newsworthy loss. Also if it was their correct target, then the killer couldn’t do any further harm. Poirot M. Bouc. and Dr. Constantine appeared in the right to protect the family,.

The verdict required a decision based on limited evidence and the consensus was based on intuition over reason. Reason and intuition conflict as justice does with clemency. If the court is corrupted or powerless to bring justice, the victims will pursue in their own way. There is strength in unity. If the Armstrong household is caught or proven to be mistaken about Ratchett’s identity after they get off the train, then they can much more easily bear the blame and responsibility together.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Blade Runner

Blade Runner

1982

Abstract:

Deckard is an android hunter who loses his resolve to discriminate against androids. Throughout his investigation, he begins to value the lives of others once he starts valuing his own. His near death encounters and budding romance invigorate a new desire to live. After the hunt finishes, Deckard chooses to not serve the state but instead protect the android that loves him.

Retelling:

In an impoverished and derelict world, Deckard is a Blade Runner who gets tangled up in the lines between humans and androids. To keep his privileges, Deckard is coerced back into serving the state for another assignment to sift out and “retire” more replicants. The androids struggle to free themselves from their chains while Deckard is jaded by his duty of hunting them. With the android falling in love with him and watching another facing tragedy and death, he chooses a new path that puts him on the run.

Symbolism: Slavery

The replicants are made expendable for space slave labor just as the working class is on Earth. Deckard is a replacement and declines his new assignment until admitting “I have no choice,”. Like a watchdog, the police are always checking in on him throughout the case.

LA citizens and replicants had opposite directions yet work towards their same distant goals of some better life. The rebellious androids return to Earth, while the working class hopes to leave. The sparkling blimp over the polluted and derelict planet promises a better life in the space colonies.

Tyrell tells Roy they can’t extend their lives. They were sentenced to a short lifespan long ago. The police officer says at the end, “it’s too bad she won’t live, but then again, who does?” The humans, just like the replicants, were slaves to their mortal coils.

While enslaved, romance gives new meaning. The sexual attractions to the females infer that Roy and Deckard both used their intimates for strength; they faced the fears of going against their duty and making a choice to run.

Allegory: Coming of Age

Restricted as youth, humans have limited rights until a certain age. The androids are always too young since they die after 4 years. Both minors, children and androids cannot make a living, make a family, or vote for representation. The Nexus-6 replicants are smart and skilled, but their sentience doesn’t have legal grounds to grant them rights. As with minors, their intellect and abilities aren’t considered in the eyes of the law.

Androids and minors live with roles given by their respective establishments. Their destinies are chosen for them: The replicants are sent to the outer world colonies for work, and minors are sent to school for education. They both have limited respect as the replicants are compared to toys and called “skinjobs”; they live in servitude of their master’s wishes. Minors are rewarded for obedience, used for free labor. and treated as an accessory to their owners.

Youth face discrimination based on the ambiguous ages of adulthood and consent. Being very young, replicants tend to be emotionally childlike. In the unseemly romance, Deckard may have taken advantage of the replicant’s immature feelings of love. To protect minors, the law turns them into consenting adults after living for a certain number of years. This rudimentary measurement for maturity is useful in protecting those who can’t protect themselves but attests to the lack of understanding in what makes somebody human.

0 notes

Text

Review: Toy Story 4

Toy Story 4

2019

Abstract

Woody is an unwanted toy who finds meaning outside of being a child’s piece of property. He struggles with obsolescence and losing his place. His values turn against him. As a result, he is a bother and trouble to others. Throughout his destructive journey of self realization, he learns how to move forward and ultimately gives himself the agency to redefine his purpose in life.

Retelling

Convinced he knows what’s best, Woody scrambles to maintain his usefulness: he takes on the role of a babysitter for a dysfunctional toy, Forky, made by his child. Through his futile attempts to be useful while bringing other toys into predicaments, Woody becomes painfully aware of his own conflict of interests due to his blind determination. He chooses to give up a valuable part of himself, his voice box, to another toy so that she might have the opportunities he had. With the excessive help from his friends, Woody returns Forky but chooses to abandon his child and to stay behind with the rekindled Bo-peep and the rest of the unwanted toys he befriended along the way.

Symbolism: Voice Box

The virtuous conflict of self-denying and self-affirming. Woody is driven by virtue of the selflessness that gives someone else happiness. He defines what is to be most noble as service to the children, loyalty, and “no toy left behind”. In contrast, Woody learns how to listen to his inner voice as Buzz took quite literally by clicking on his voice box for guidance. Buzz shows how the toys can’t think for themselves without a placed purpose. When Woody let’s Gabby take his voice box, he is also giving up that old inner voice. Woody goes beyond his selfless virtues and finds the voice that says to take care of himself.

Analogy: The Seasons of Life

Parents and children: pining for love and dependency. Relationships can grapple with either growing apart or changes in roles. Woody had to change his role or let go of his child. As children become more independent parents must regain their own sense of identity outside of being the chief caretaker. Woody used Forky to be involved with Bonnie in a way parents might use manufactured problems to remain involved in their children’s lives. The other toys wanted to believe in Woody and his “noble” cause to make things better, but he continually made things worse. As parents must realize, their selflessness can sabotage relationships. This fear of loss in purpose can be shown through over-involvement as he took upon himself the extraneous duty to help Bonnie at kindergarten, the over-protection as in the creation of Forky with the ridiculous responsibility of pulling him repeatedly from the trash. and the destructive care-taking as he helped Forky, a piece of trash toy, at the expense of others and himself. Both parents and children, like Woody, must realize that following one’s own path will not only benefit themselves but those they cherish.

0 notes

Text

Review: Alita: Battle Angel

Alita: Battle Angel

2019

In the hi-tech dystopian world, Alita struggles with her love, duty, and family as an elite warrior teenage cyborg girl. Dismantled and suffering from amnesia. she is found in the scrapyard in the center of Iron City, the dump under the sky city Zalem. She gets repaired and revived by the fatherly Doctor Ido, who takes care of this curiously trashed charm.

Dr. Ido and his wife were both exiled from Zalem, by a someone known by the name, Nova. Working in a dangerous sport business, they separated after their cripple daughter was murdered by a client. Doctor Ido dedicated his life to charity and bounty hunting while his ex wife continues helping in the cyborg death sport called motor ball.

Alita’s counterpart enemy is the giant cyborg hitman, Grewishka. He longs for approval from his boss. He is also a scrapyard rescue like Alita but a level below Iron City and Zalem. Alita first battles the giant when she saves her father figure /bounty hunter /doctor from a trap set to kill him. After the encounter and learning of her fighting abilities she wants to protect the doctor from Grewishka and so joins the bounty hunter’s guild. However, Grewishka has no bounty on his head since he works for a mysterious boss in Zalem.

Through life-or-death situations, Alita eventually learns she is an elite Martian “URM” warrior programmed to destroy

Earth’s last sky city Zalem. She uses her doctor’s daughter’s body for incredible fighting, but destroys it fighting Grewishka. She discovers and is rejoined with her old “berserker” body using it to further achieve her goals.

Alita’s love interest, Hugo, is an attractive yet dense Iron City youth who dreams of living up in Zalem. Hugo is key in introducing her to the sport motor ball. Like the doctor, Hugo also has a shady job. He secretly jacks body parts from cyborg hosts for his “connection” to Zalem. Conflicted since his girlfriend is a cyborg, he eventually quits at a time that endangers his friends and himself. He also gets outwitted by his Zalem connection and leads Alita into a death trap through motor ball trials. Through his lack of foresight and Alita’s wanton aggressions, he gets a bounty on his head and dies pursuing his dream to Zalem and risking Alita’s life again.

After the tragic death of Hugo, she becomes driven threefold; by avenging love, fulfilling duty, and protecting family. The exile of Dr Ido, the death of the dullard Hugo, and her military programming all conveniently center the come to a headon one man, , the elusive eye in the sky.

She breaks into the Factory, Iron City headquarters, and exchanges threats through Nova’s puppet. Determined to find and kill Nova, she rejoins the motor ball competitions as the top champions are sent to Zolum, where her new target resides. With her overpowered fighting style, body, and blade, she seems to quickly rise up in the ranks off screen and the story ends at the start of her final race.

Character:

Alita is the paragon of purity in the form of an innocent girl. She is also the most deadly weapon in existence. Despite her immense power, her main weakness takes the form of naively trusting those she meets and lacking suspicion. The Dr. Ido and boyfriend Hugo both use this trait to their advantage while also discouraging it.

Dr. Ido is very selfless and virtuous in his work, but coddles Alita as he can’t let go of his past. She immediately gives an unusual amount of loving affection to Dr. Ido despite being complete strangers. Giving Alita both his daughter’s body and name, the doctor openly takes the opportunity of having a girl with no memory to groom her into replacing his daughter.

Hugo is bent on going to Zalem at all costs and for unclear reasons. He works in the black market and is naively convinced he can earn enough to pay off his Factory boss. Alita is content living in Iron City but wants to help her boyfriend follow his dream. Hugo refuses both of her offers: to sell her heart or collect bounties. Instead he gives her a more dangerous offer. Seeming to blindly following his connection’s advice, he convinces Alita to play competitive motor ball, a deadly sport, so that she can become the city champion earning the grand prize of going to Zalem. Hugo plans to pay off his connection with her winnings.

Hugo’s work conflicts with his relationship since he preys on cyborgs and jacks their parts. He is the foil to Dr. Ido. One is stuck in the past, while the other in the future.

They both have similar weaknesses. Dr. Ido appears to naively trusts Alita and expects her to obey despite knowing about her URM programming. The boyfriend naively trusts the promise of going to Zalem.

Alita is innocent yet an extremely powerful warrior. Fortunately for her though, her ignorance never appears to conflict with her deadly strength; as all of her goals align with her actions.

At first she acts as a child with adorable curiosity. She then savagely passes judgement on everyone at the bounty hunter’s tavern and chooses to fight them all immediately. She then falls deeply in love “it’s all or nothing with me”.

0 notes