Follow some of our students and scientists as they venture far off campus and brave the elements – all in the name of science.#Seaplastics (Mediterranean Sea)#Ciudadabierta (Chile)#MasterProjectInCostaRica (Costa Rica) #MasterInternshipCali (Colombia)#VanishingGlaciers (World)#SnowFallInAntarctica (Antarctica)#SiberianSnowpack (Samoylov, Russia)#ArcticPermafrost (Svalbard, Norway)#CoralSeaGenomics (New Caledonia)#SnowFallInKorea (Korea)#CoralsOnAChip (Israel)#LifeUnderTheIce (Russia)#HairPollution (Burkina Faso)#PortAuPrince (Haiti)#FallingIce (Antarctica)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Aller-retours dans les bouches de Bonifacio

Semaine du 27 juin au 3 juillet

Cette semaine, nous avons vogué entre le Sud de la Corse et le Nord de la Sardaigne, guidé par notre nouveau skipper Marc! Première escale: le petit village coloré de Castelsardo.

On y rencontre une vingtaine de lycéens, venus prendre un cours de surf. Nous sommes entourés de l’adjoint au maire, des moniteurs du Bulli surf Club - particulièrement impliqués dans la protection des océans - et membres de l’association italienne Plastic Free et de la brigade des sauveteurs en mer de la ville. Présentation sur les microplastiques et l’association, puis on se penche sur le sable pour faire un ramassage… et découvrir des quantités énormes de pellets! On apprend que cela viendrait d’une ancienne usine de plastique sur le littoral, fermée depuis plus de 30 ans… On enchaîne avec un stand en français-anglais-italien, puis on assiste au lever de drapeau bleu.

A Bonifacio, petite séquence émotion… c’est notre dernière sensibilisation dans une école! On y rencontre des élèves éveillés et attentifs malgré les grandes vacances qui approchent. Nous distribuons pour la dernière fois les carnets de Fabrice Amedeo, puis on redescend de la vieille ville fortifiée vers le port. Le lendemain, on tient un stand à la capitainerie: le monde est au rendez-vous, de tout âge et nationalité!

Nous repartons dans l’après-midi vers la Sardaigne. A la Maddalena puis le long de la descente vers Olbia, nous y enchaînons les mouillages et les prélèvements… nous en sommes à notre 17ème échantillons pour OceanEYE!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seaplastics en Corse et en Sardaigne!

Semaine du 20 au 26 juin

Descente de la côte Ouest Corse … direction la Sardaigne !

Cette semaine on est descendu de Calvi à Ajaccio, puis on a traversé les bouches de Bonifacio vers Castelsardo. La côte est magnifique, et on s’en ait mis pleins les yeux : les roches rouges de la réserve de Scandola, les iles sanguinaires, les criques Cacao et Campomoro…

Mais nous avons aussi bien travaillé! Nous avons fait une sensibilisation à l’école d’Ajaccio, avec des enfants de CE2. Comme la fin d’année approche, nous avons opté pour un nouveau format: que des jeux! Nous avons pu tester et partager le jeu de société créé par Anne-Laure, Ecosys, où le but est de construire de manière collaborative un écosystème… en contrant les cartes menaces qui viennent le fragiliser ! Il a été très apprécié par les enfants, et permet de découvrir pleins de nouvelles espèces aux noms scabreusement poétiques! 😊

Nous avons aussi poursuivi les échantillonnages… avec quelques péripéties! En effet, nous avons découvert un trou dans le filet Manta utilisé pour les prélèvements du LNE-AP … Après discussion avec nos partenaires et visite dans une mercerie, nous avons décidé de le recoudre le long d’un pli: à nos fils et aiguilles!

Nous avons aussi numérisé les données des échantillons pour OceanEYE, et nous nous sommes rendu compte qu’une partie étaient non valides… après un appel avec nos correspondants de l’association, nous avons pu corriger quelques informations (la numérisation en navigation n’est pas une science exacte!), et avoir des pistes pour améliorer le reste. Le dernier échantillon fait avec les corrections de protocoles est noté valide… on continue sur cette voie!

Et cette semaine, ce sont nos premiers pas en Sardaigne! Hissons le pavillon avec les 4 têtes de Maures, et Buongiorno a tutti!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Retour en mer pour Seaplastics

Semaines du 15 mai au 19 juin

Ça y est, nous sommes est à bord de notre nouvelle maison!

Le bateau est chargé, les cales remplies, les pleins faits: on est fin prêts pour faire la traversée pour la Corse ! On est en pleine zone Pelagos, une aire de protection de cétacés entre la côte française, italienne et corse. Pendant les quarts de la traversée, on a la chance d’apercevoir deux paires de rorquals communs, plusieurs dauphins stenella, des tortues et des poissons lunes ! La mer est d’huile, et on peut bricoler sur le pont du bateau un nouveau système qui va nous éviter de pomper 45 min toutes les 6h pour les jarres. On arrive à Saint Florent, première escale corse!

Les activités de sensibilisation reprennent, avec la rencontre d’une classe à St-Florent avec l’association Corse Mare Vivu, et d’un stand tenu à Calvi. Les prélèvements avec le filet Manta sont aussi de retour, car il faut rattraper le temps de pause dû à la recherche du bateau. Cette semaine, on a pu faire 3 prélèvements en triplicats pour le LNE et APT, et 4 points pour OceanEye avec le filet de la SCS ! On a pris nos repères sur le Five, et nous sommes de plus en plus efficaces.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Moments marquants pour Seaplastics

Semaines du 15 mai au 19 juin

Que s’est-il passé ces dernières semaines … ? Beaucoup de rebondissements pour notre aventure SeaPlastics !

Suite à un imprévu majeur sur le Meltem, nous avons quitté le bateau à Gruissan. Vider les cales, mettre en pause les expériences, ranger et nettoyer le bateau, cela n’a pas été de tout repos! On a sorti les 210 boîtes encore immergées dans les jarres, on les a séchées puis nous les avons congelées. 9h de séchage à trois, en rotation pour soulager nos poignets! Heureusement, nous avons trouvé un toit accueillant et du soutien logistique auprès de la famille d’Antoine, encore merci!

Ensuite nous nous sommes mis à fond tous les 5 pour chercher un bateau… Direction Hyères, dans la maison de la famille d’Alice, pour se rapprocher du point de départ pour la Corse. Cadre idéal pour chercher un bateau, à deux pas de la plage ! Un immense merci à eux ! Démarchage des ports, rencontres dans les clubs de plaisanciers, milliers de coups de téléphone… on s’est bien démené! Cela a fini par payer, car nous sommes tombé sur des gens très bienveillants, à tel point qu’il a fallu choisir entre plusieurs solutions!

Finalement nous sommes reparties sur un Ketch de 50 pieds, le Five, basé à Porquerolles. Gracieusement prêté par un particulier, il va nous permettre de faire le tour de la Corse et le nord de la Sardaigne. On rentrera à Hyères le 15 juillet, pour rendre le bateau. On a aussi rencontré Nicole, skipper professionnelle, avec qui on va reprendre la mer. Confiance et bonne ambiance, ça promet d’être sympa!

Pour les deux dernières semaines de juillet, nous embarquerons à bord du Sun Fizz, Haumana, de Julien. Avec comme projet de partir en tour du monde en octobre (@haumana_tdm), lui et sa compagne ont bricolé leur bateau depuis un an! Pour notre plus grand bonheur, nous avons pu embarquer dessus à l’occasion d’un tour de Porquerolles. En escadre avec Julien, notre futur capitaine, et Alex, un de ses amis voileux, on a pu reprendre plaisir à naviguer… Avec 30 nœuds de mistral, les sensations étaient au rendez-vous! Les retrouvailles de juillet son prometeuses!

La dernière semaine, nous avons préparé notre ré-embarquement: nouvel itinéraire, nouvel inventaire, reprise et organisation des sensibilisation, prévision des échantillonnages. On vide le Five des affaires personnels du propriétaire qu’on stocke à Hyères, afin de libérer de la place pour nos jarres et filets! Il n’y a pas de doute, nous avons hâte de reprendre la mer!

0 notes

Text

Bilan du premier mois en mer

Semaine du 25 avril au 1er mai

Déjà un mois que nous sommes parties! Cette semaine, nous avons terminé notre périple le long de la côte espagnole. Après une sebsibilisation au lycée français de Barcelone, nous avons longé la Costa Brava en direction du port de Roses. Puis nous avons traversé le Golfe du Lion pour rejoindre Marseille, notre première escale française. La navigation de nuit fut sportive, mais nous sommes malgré tout arrivées à bon port!

Ce premier mois peut se résumer en quelques chiffres:

- 949 milles nautiques

- 9 escales : Gibraltar, Malaga, Cartagena, Alicante, Valencia, Ibiza, Cala Figuera, Barcelona et Roses

- 18 echantillonages avec nos filets: 3 pour OceanEye, 4 triplicats au manta et 1 au fermant pour le LNE-APT

- 4 échantillonages de nos petites boites filtrantes:

- 3 semaines depuis que nos bandes de plastiques sont exposées:

En terme de sensibilisation, nous n’avons pas chômé non plus! Nous avons déjà rencontré 1414 élèves, tenu deux stands et donné une conférence. Ce n'est que le début du périple, l'aventure continue!

0 notes

Text

Iles Baléares – navigation et échantillonnages

Semaine du 18 au 24 avril

Cette semaine, nous avons beaucoup navigué et effectué de nombreux prélèvements scientifiques. Parti·e·s de Valencia, nous avons caboté le long des Îles Baléares.

Profitant des moments calmes de la météo, nous avons réalisé deux points d'échantillonnages de microplastiques avec triplicat pour le LNE-APT, en utilisant le filet manta. La procédure avec le tangon est maintenant bien rodée! Nou avons également effectué notre premier point de prélèvements dans la colonne d'eau. Assurer la verticalité de la descente du filet fermant s'est avéré plus technique que pensé, mais on va se faire la main!

Nous avons aussi mis en route la dernière partie de l'expérience de vieillissement, en trainant derrière le panier contenant le dernier set de bandelettes. Nous avons fait le premier point de prélèvement des bandelettes accrochées au mât et au balcon arrière. Ces échantillons ont été placés dans la glacière avec les petites boites filtrantes récoltées chaque semaine dans les jarres. L'expédition se poursuit au rythme des traversées et des escales, des coups de filet et de la tension des batteries.

0 notes

Text

Seaplastics en Méditerranée

Semaine du 11 au 17 avril

Bonjour à tous et toutes !

Je m’appelle Laurine et je suis étudiante en master SV à l’EPFL. J’ai fait mon Bachelor dans cette même section et j’ai pu partir en 3ème année à NTNU Trondheim en Norvège. Là-bas, j’ai pu découvrir la biologie environnementale et plus largement les sciences de l’environnement. L’implication concrète des études dans nos problématiques de climat actuelles m’a beaucoup plu, avec l’impression d’avoir un pied dans le réel et d’essayer, humblement, de comprendre et de faire bouger les choses. De retour à l’EPFL, j’ai gardé cette orientation par le choix de mes cours et des stages.

En mars 2021, j’ai pu rejoindre l’équipe SEA Plastics, avec Anne-Laure, Alice et Clara. Ce projet étudiant d’AgroParisTech a pour but chaque année de monter une expédition de 4 mois en mer Méditerranée.

A bord du voilier-laboratoire, nous effectuons des prélèvements pour le LNE (Laboratoire National de Métrologie et d’Essai) et AgroParisTech dans le cadre d’une étude sur les méthodes de caractérisation des microplastiques. Ce partenariat est dans la continuité du travail de l’équipe SEA Plastics de l’année passée, et les nouveaux échantillons permettent d’améliorer les protocoles et d’avoir des données comparatives.

Nous participons également à la mise en place de la base de données international de OceanEYE (Genève), qui est partagée avec le Programme des Nations Unies pour l’environnement. Cette année, nous avons aussi monté nos propres expériences sur le bateau, pour étudier les cinétiques d’adsorption des micropolluants sur les microplastiques, et le vieillissement des plastiques en conditions marines. Épaulées par Mr. Breider dans le design des expériences, nous avons également été aidées par de nombreuses personnes de l’EPFL dans la conception. Nous avons découvert le défi que représentent les expériences embarquées et les mesures du terrain… ! Le système que nous avons finalement mis à bord à Gibraltar le 29 mars est le résultat de l’imagination, débrouillardise, motivation, solidarité et discussion de nombreuses personnes. Encore merci à elles et eux !

L’expédition est aussi rythmée par les escales dans les ports. On y retrouve des classes pour des ateliers, on monte des stands. Parler de cette pollution au plus grand nombre de personnes est notre deuxième défi ! Jeu, conférences, news lettre pédagogiques et réseaux sociaux, on essaie de diversifier les points d’accroche. L’expédition est sportive, humainement intense et scientifiquement très enrichissante ! Tout est source d’apprentissage! 😊

0 notes

Text

The Rainless Transect

Patagonia. An austral territory partitioned between Chile and Argentina, famous for its wild landscapes and unparalleled beauty, hosts the largest ice masses outside Antarctica and Greenland. Notorious for its intense rainfall and ferocious winds, it was selected as the starting point of the 11th Vanishing Glaciers expedition. In theory, this wild setting would tune our team with the boreal winter conditions we left behind by mid-January. So it made more sense that in our quest to be in “Harmony with Nature” to start in the most wintrery part of Chile to avoid potential climatic shocks.

Again, things worked again in the opposite direction to our desires. To our “disappointment” right from the first day we were confronted to the heat and the blazing austral sun, totally disharmonized from the boreal winter and the harsh weather continuum built over the last year’s expeditions in the Himalayas, Pamirs and in Uganda’s Rwenzori Mountains. By the time of our arrival, Patagonia was experiencing a heat wave. But this time, the climatic paradoxal conditions were greeted as a good surprise, with a “too good to be true” feeling suspended in the air that stayed with us for the entire expedition.

The first sight of the Patagonian glaciers was something like “love at first sting”. Vulcan Michinmahuida seen from the ferryboat ride from Puerto Montt to Chaiten (Photo © Mike Styllas)

Going the distance full house

Our plan involved the sampling of glacier streams and rivers spanning the diverse climatic regions of the wet and dry Andes. Two years ago, we worked in the tropical Andes of Ecuador, so in order to get a representative view of the entire Andes mountain chain we planned to work along a 1500km traverse from northern Patagonia, to Val de Maipo, northwest of the capital Santiago. In this trip, we were not just usual four suspects, but the house was full. Our colleague Peter Hannes joined us for the first part of the expedition. Hannes who was the locomotive of the inaugural Vanishing Glaciers expedition in New Zealand, resolving ever surfacing fieldwork setbacks when the rest of us were struggling to figure out the sampling protocols and make proper use of the equipment, had also surprised us with his fly fishing capacities. Same story, different place. In Patagonia, Hannes reminded the team that some delicate skills acquired in the field are there to stay and fresh trout became synonymous with his participation in the project’s expeditions. Luis Gomez, who was a member of the River Ecology lab for two years, also joined our ambitious fieldwork traverse from his new position, as a researcher in the Centre for Research on Ecology and Forestry Applications (CREAF), in Spain. As a native Spanish speaker, Lluis was there to help the team navigate through several delicate situations that would have taken us considerably more time and effort to resolve. Throughout our traverse, we also had several local colleagues from the Universidad Austral de Chile in Valdivia and the Universidad de Conception that contributed to the success of our back-to-back fieldwork campaigns and added a different flavor to our daily working routine, enriching our knowledge with social and political feats that shaped the modern history of Chile.

Guest stars Lluis (left) and Hannes (right) showing their special fieldwork skills…here pumping liters of very dirty (turbid) water in front of a Mocho outlet glacier (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

A smooth and hot journey One of the most frequent terms in nearly all previous updates is “logistical hurdles”. Herein, is omitted just because there was none. The pleasant weather in Santiago was complemented by a quick and easy experience with the Chilean customs, with the invaluable help of Professor Mauricio Gonzalez from INTA (Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnología de los Alimentos de la Universidad de Chile) and soon enough our equipment was travelling with us to the northern tip of Patagonia. Approaching the glaciers by the sea was a sort of deja-vu, as we had lived through a similar situation in our Greenland expedition, back in 2019. Sights of seals, green lush forests and low elevation rounded and heavily glaciated peaks under blue skies filled the cadre as the ferry was approaching the small town of Chaiten.

Living earth I. Pyroclastic flows on the moraine and volcanic ash covering Turbio glacier, with Vulcan Villarica steaming in the background (Photo © Martina Schoen)

Once we finished with the southernmost cluster of glaciers, we hit the road and moved northwards just to verify that Chile is a very active member of the Pacific “Ring of Fire”. The volcanoes of Villarica and Chillan were degassing constantly giving us the pace of earth’s breathing. Villarrica had a major eruption in March of 1971, when the upper part of the crater was cut by a 4 km long fracture and 30 million cubic meters of lava were ejected half kilometer above the crater and then flowed downslope as far as 14 km from the summit. The tephra fallout of this eruption covered an area of 200 km2 with black basaltic ash. Villarrica erupted for the last time on March 3, 2015, this time emitting gas, ash, and lava up to 1000m into the air. Even though we had worked in volcanoes before (Disko Island in Greenland, Mount Elbrus in Caucasus and in the Ecuadorian volcanoes), the sampling the glaciers of a steaming and vivid volcano was something new.

Living earth II. Volcano Chillan just breathed once more, alarming the evening calmness of our base camp (Photo © Vincent De Staercke)

Alive

“Welcome to my mountains” said Roberto Frank, as he was patiently waiting for our team to arrive in the gate and enter his property on our approach to Universidad Glacier. This glacier was an important feature of our long traverse, as it marks boundary between the wet and dry Andes, along which rock glaciers and other periglacial features do not exist further south. Aside from the scientific importance of the location, what we did not know is that Universidad glacier was the stage where one of the wildest acts of survival of the 20th century took place. Roberto described in detail the airplane crash above Universidad glacier in October 1972, when a military plane that was carrying the Uruguayan rugby team, crashed above our sampling point. The survivors of the crash, after resorting to cannibalism, had to find the strength to cross the glacier to make it down to the valley and call for help. The survival was brought to the broad public in 1974 through the book of Piers Paul Read “Alive”, which later on made it also to the big screen. To our luck, after the day we sampled Universidad Glacier, there was an event hosted in Roberto’s ranch where the helicopter rescue pilots and other people directly or indirectly involved in the accident were present along with the memories of this incredible story.

The intimidating mountaintops towering above Universidad glacier, a place where the ultimate act of surviving the Andes took place in 1972 (Photo © Mike Styllas)

The 150 milestone

Universidad glacier was not only a glaciological landmark, or a place of the ultimate survival act, but comprised the site where we celebrated the sampling of the 150th Vanishing Glaciers.

Juan, Mike, Gianni, Ramon, Matteo, Pablo. Luis and Martina with Vincent celebrating the 150th ice kiss. (Photo © Vincent De Staercke)

Past the 150-glacier milestone and upon our return from Chile, we figured out that so far we have ticked all but one points on the Vanishing Glaciers project destinations map. The final destination of our project’s expeditions is Alaska, and we are confident that after some time in the lab, our desire for more special encounters and fieldwork in the wilderness of The Last Frontier will revive more and more as the spring is coming in.

Our best wishes for a productive and pleasant springtime! Martina, Matteo, Vincent and Mike

1 note

·

View note

Text

A High Prize for the Vanishing African Ice

The return of our team from the summery Uganda to the wintery Lausanne before the Christmas break had a feeling of achievement. Our tropical raid to sample the Vanishing African glaciers was awarded by a desired “window of opportunity” which gave the chance to collect our samples and run our experiments in a stunning setting that does not remind of Africa. However, the momentum was outpaced by the intense preparations for the following Andes expedition and the Festive Season, but on the other hand, this period gave enough time to recall the wonders of the Rwenzori expedition and organize a gesture of gratitude to the local people that made things work for us.

Martina Schoen and Matteo Tolosano enjoying the hidden frozen jewel of African nature, the Stanley glacier, in the only sunny day of a 2-week trekking raid in the Rwenzori Mountains (Photo © Mike Styllas)

For most people, glaciers in Africa are an obscured concept, shared between relatively few passionate mountaineers, who are allured by the conquest of the Roof of Africa. Kilimanjaro holds this title, but we would argue that most local people in Kenya and Tanzania, where the Uhuru Peak is rising 5895m above the sea level, are not aware of their country’s vanishing ice masses. A few hundred kilometers to the northwest, Margherita Peak, the pinnacle of Uganda’s Rwenzori National Park, a declared UNESCO world heritage site since 1996, is the third highest summit in Africa and also hosts several small glaciers, which in contrast to their Kenyan - Tanzanian counterparts, display movement and feature glacier streams, an ideal setting for our project.

Our beloved guide, Ochora with Martina Schoen and Tyler Kohler embarking for the most demanding and “wet” sampling undertaken so far, for Vanishing Glaciers project (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

Our official collaboration with Makerere University in Kampala was very fruitful and to our pleasure and gratitude came the fact we shared the impacts of tropical African glacier recession and alpine ecosystems dynamics with two very dynamic women, Dr Juliet Nattabi and Dr Rosemary Kawaga from Makerere University, who were also catalyzers in overcoming and resolving successive logistical setbacks. Our experience and persistence, as well as the fact that English is the official language in Uganda, gave additional momentum to the never-ending bureaucratic battles, which were dressed with certificates from states agencies over other agencies and other delays. After we spent a few days in the calm and quite campus of Makerere University and with all issues resolved, we loaded the safari vans and headed to the Rwenzori National Park.

While driving through the Ugandan countryside and bumping into the different species of the eastern African fauna, the thought that we had to pull off the climb to the Rwenzori’s at the end of the wet season was suspended in the back of our minds. This meant that humidity would be our best friend over the next weeks. Polar scientists that undertook research on the Rwenzori glaciers claimed the place to be “colder” than Antarctica itself, due to the combination of constant wetness and cold conditions on the upper mountain.

The first encounters with the African fauna occurred on the road from Kampala to Kilembe (Photo © Mike Styllas)

Our ultimate goal to collect samples from an ecologically, microbiologically and geomorphologically extreme glacier, resting in a tropical setting at 5000m above the sea level, revived when we set foot on the Rwenzori’s base camp, the village of Kilembe. The massive deposits of the 2013 Nyamwamba river flash flood, which destroyed 70 buildings, several bridges, a hospital, a school, a tarmac road and other infrastructures , gave us a contrasting welcome in a very dynamic the place with calm local people.

Remnants of the 2013 destructive flash flood in Kilembe (Photo © Martina Schoen)

From the first day of the march towards Stanley glacier, we were awed by the vegetation and strange animal species found along the trail. As we climbed higher, we were relieved to leave behind the malaria threat of the lowlands, but from the first evening, we felt the moisture penetrating through several layers of clothing. Our daily menu involved muddy trails through patches with incredible plants and trees, through bamboo forests, through bogs with wooden passages. And this magnificent landscape kept changing every day.

Crossing a wooden passage through one of the numerous bogs (Photo © Mike Styllas)

The high levels of humidity, as these tropical forests “respire” and the daily rain, were a good reminder that glaciers in the tropics are still surviving due to ever-recycled moisture and dense cloud cover. Other climate extremes over eastern Africa such as severe droughts were evident from the burned stacks of trees left behind from a wildfire that occurred nearly a decade ago. With so much rain and humidity during our stay, it was hard to imagine a wildfire burning the entire catchment, but in 2012 a widespread drought in the area, with two consecutive dry seasons and minimal rain during the intervening wet season occurred. The wildfire burned down significant portion of the upper catchment and climbed up to the proglacial area. The year after the wildfire, the devastative flash flood occurred when torrential rains over the burned slopes and released large amounts of water, mud, sediment from the upper catchment.

From the base of the mountain to our highest camp, we had to hike in rubber boots, as mud and continuous stream crossings filled our daily hiking menu (Photo © Martina Schoen)

In addition to the abundant moisture and water flowing everywhere, we were also struck by the dark color of the stream water. The entire setting appeared to be a great storage of carbon that was flushed out of these steep and densely vegetated catchments through the hydrographic network.

The typical landscape of the misty Rwenzori’s during the first days of our approach to the glaciers with the dark carbon rich water flowing everywhere. (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

As we moved higher, successive glacial lakes and frontal moraines marked our entrance to the extensive proglacial zone, which unlike the mid and high-latitude glacial settings, was dressed in a tropical suit. As the glaciers extended down to these locations a few thousand years ago, it was amazing to see how fast vegetation can be established and climb to higher elevations in the tropical alpine belt. Cloud cover, moisture and rain kept being our companions on a daily basis.

Despite the dense vegetation the proglacial lake bounded by a terminal moraine, reminded us that the glaciers extended at this location a few thousand years ago (Photo © Martina Schoen)

When we finally reached Margherita camp and prepared our sampling equipment the cloud finally broke and we were suddenly exposed to a stunning alpine setting with small glaciers hiding between steep rock walls and rocky towers. Sampling the stream of Stanley glacier on a sunny day made all the muddy hiking and wetness related fatigue to evaporate and still looms like the perfect moment of our trip. However, even this day did not start as easy and the going in the rocky ledges was tough, as frozen moisture and verglass were spread over the cliffs and couloirs leading to Stanley Plateau. Then the cloud dissapeared and the views became fantastic as alpine Africa and Stanley glacier were basking into the strong tropical sun. The sunny day and the blue skies during our fieldwork time up there were definitely a highlight of this trip, but there were brighter moments during our Uganda expedition.

The intimidating view of the upper mountain from Margherita camp (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

En route to Stanley Plateau. Nothing could foretell that this foggy, cold, wet and slippery scramble would lead to a glorious day (Photo © Martina Schoen)

While in Kampala, we had the chance to share Vanishing Glaciers project concept and recent sceintifc findings with the students of the Seven Hills International School. We are particularly thankful to Ms Romina Kohler, the Swiss Honorary Consulate in Kampala and to Ms Alice Bourgoin, the Head of the School for organizing this event. The general interest and the acute questions of the students, was a good reminder that young generations are aware and interested into issues related to climate change impacts on glaciers and alpine ecosystems. To our surprise, this event concluded with an aura of hope, as the millennials attending the talk were also seeking solutions to the ongoing climate and environmental crises.

Tom Battin, presenting the expeditions and most recent scientific findings of Vanishing Glaciers project to the students of the Seven Hill high school in Kampala. (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

Over the two weeks spent on the slopes of Rwenzori Mountains, we had a great chance to become friends with our team of guides and porters. Besides the scientific part, the whole raid was a very informative process, as from the start of the trek we became exposed to several legends and myths that envelope the Rwenzori’s in a similar fashion as their moisture clouds. The mountain tribes were an open encyclopedia in terms of the plants healing and medical capabilities and our guides conveyed this collective empirical knowledge in every corner of the trail. Several talks with the team members over smoky fires burning wet wood invovled broader subjects like the social structure of Uganda, the civil war and the difficult years that followed, and gave us the chance to become familiar with the evolution of life in eastern Africa since the colonial times.

The team with Dr Rosemary Kawaga on its way to Uganda’s Vanishing glaciers (Photo © Martina Schoen)

The bonding with the entire team of porters and guides became stronger as the days went by. We were inspired by their professionalism and patience to make our expedition happen and by their willingness to share with us knowledge about their mountains and life experiences. On the downside, it was very disappointing to see that these bright people, among several difficulties of their everyday life, had to face the cold and humid conditions of the mountain with inadequate, not to say primitive equipment. The fact that we were hiking with a team of porters and guides lacking the essentials to pull out a trek like ours, ranged in our ears from day one. As the days went by and the conditions became harder, we felt that the least we could do upon return to Lausanne, was to organize a campaign and ship used outdoor equipment to these people that will make their work on the mountain as guides and porters a little easier.

Mountain gear bound to Africa. Tom Battin’s initiative to collect used equipment and send it to Uganda found a great response from the UNIL – EPFL community (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

In the end, the High Prize for our African expedition was not the demanding and successful sampling campaign of Africa’s vanishing glaciers. The highlight from our Rwenzori expedition is the fact that we did meet many hard working, bright people inhabiting the jewel of Africa and thanks to the solidarity response of the joint EPFL- UNIL community, these people with their big smiles, can work under better conditions on their beloved mountain and shine a little more. They deserve it!

Best Wishes for a Fruitful and Productive New year to the entire EPFL - UNIL community!

The Vanishing Glaciers project team

0 notes

Text

Exploring the last bits of the African tropical glaciers

Out of the wintery Lausanne, armed with vivid memories of High Mountain Asia, bound for the tropics this time to encounter the last African glaciers. When it comes to the impacts of climate change on the melting of the world’s glaciers, tropical glaciers are definitely the first victims. In Ecuador, we witnessed the tremendous retreat of the glaciers on the prominent volcanoes of the tropical Andes. This time we are privileged and challenged to conduct our fieldwork in the Vanishing Glaciers that tower the Pearl of Africa.

The glaciers of Uganda’s Rwenzori Mountains have witnessed a dramatic retreat that was nicely captured (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eHiRQMHtYFI) by Tim Jarvis’ project 25Zero. To the mountaineering world the adjacent Roof of Africa the Kilimanjaro, which also hosts last bits of African glacial ice, shadows the misty Rwenzori Mountains. However, the glaciers of the Rwenzori resemble better locations for Vanishing Glaciers project. An ice-capped peak protruding above the misty tropical forests can only have surprises, in its vegetation, in its scenery, in its microbial life, and in the adventure to reach the glacier.

As we start to see the light of logistical labyrinth in Uganda’s capital Kampala, we get increasingly impatient to be confronted to the misty mysteries of the Rwenzori Mountains.

The Vanishing Glaciers project team Tom, Martina, Tyler, Matteo, Vincent & Mike

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the NoMads lands

Well, apparently we are No Mads. It’s an anagram, sourcing from the special echo that still rings in our ears after a month of intense fieldwork in the land of Nomads. From the cold and wind swept Arabel Plateau, where time seemed to be frozen, we rapidly found ourselves back to the heat of Kyrgyzstan’s capital Bishkek, navigating through the Kyrgyz bureaucratic reefs, to obtain the necessary permits for the exportation of our samples. Such violent change shook the inner peace we acquired up there can really drive someone mad, so the title of the blog update goes. Far from that the calmness of Nomadic life and vivid images of the vast Kyrgyz countryside, monopolize our thoughts since our return back home.

From the Capital to the Mountains

Kyrgyzstan is the country where the Nomads house, the yurt dome, is omnipresent and the Tunduk, the central part of the yurt, is proudly illustrated along with 40 rays of sun in the country’s national flag. The Kyrgyz mountain ranges of Tien Shan and Pamir Alay, hosted the second (after Nepal) High Mountain Asia expedition of Vanishing Glaciers project. This expedition was a dive into the unknown, as it was the first encounter with the mountains of Central Asia for all team members. Besides the mountains themselves, it was our first flirt with the Nomadic culture and an introduction to the way that Kyrgyz alpinists treat their home mountains, a behaviour that has been largely inherited from the Soviet times.

The extensive piedmont of the Pamirs with carefree camels and horses, which unlike us seemed to have no reason to bother for the stormy conditions up on the mountains (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

The capital Bishkek is a good example of a fast developing and expanding central Asian city. Many green spaces and parks with running waters constitute a safe hideout from the blazing summer heat. Old Soviet grey and blocky shaped buildings alternate with traditional and more delicately shaped constructions of Central Asian architecture and a fast evolving commercial center occupied by western style modern constructions, make up an interesting visual mix in the crossroads of the Soviet past, the Kyrgyz present and the globalized future. Bishkek is one of the very few places in the world, if not the only, that people drive from both right and left sides, which apparently is the aftermath of second hand automobile importation from different corners of the world. The overall calm vibes of the city apparently help a lot in avoiding car crashes and accidents and the relaxed attitude of the Kyrgyz people is evident from the second one disembarks from the airplane. Bishkek is intelligently placed in the corner of a large fertile plain, receiving water from the glaciers of the proximal West Tien Shan Mountains, which on a clear day one feels that can really “touch” them.

Pleasant walks through many of Bishkek’s green parks, historical monuments and well maintained governmental buildings, with the glacier-covered summits of Tien Shan Mountains posing in the background (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

Familiar landscapes but…

The proximity of a large number of glaciers to Bishkek and their relatively low elevation, makes them an easy target for scientific research and after our recent Himalayan high-altitude, long-distance marches in cold and snowy conditions, we could not pass by such a luxurious reality. Ala Archa valley is a major touristic destination, where many local people spent their summer weekends to get the coolness of the glaciers’ waters, while flinging to various activities such as daylong barbequing, and some volleyball and hiking for digesting. As one moves higher in the valley, the scenery is changing and encounters with trekkers and alpinists become dominant. The landscapes were visually familiar, resembling parts of the Alps, but the wakeup call of being in Kyrgyzstan and not in the Alps, was the diet in our base camp, which involved large portions of meat from breakfast to dinner. For sure, this is not the best place for people with vegetarian or vegan rituals…

It could have been anywhere in the Alps, but it’s not. The beautiful Ala Archa valley had a little surprise for us on its upper reaches (Photo © Mike Styllas)

In Ala Archa, we worked with a big team of porters, as our goal was to sample six glaciers spread along the valley. This meant that we had to move our camp almost every day. In our efforts to pace ourselves over successive long climbs, we had to walk, or crawl across awkward metallic constructions that resembled river bridges and we came upon locations dubbed “The Dream of Idiots”, which blew philosophical dilemmas in our heads, such as “Are we also idiots to be up here?” Of course, such mental loops were blown away by the next day’s strenuous climb. Our work in the end of the valley exposed us to a new experience. A ghost building, which resembled an old Soviet ski station that was operating year round. It was hard to imagine the place crowded with people from Bishkek and workers from Lenin Factory both winter and summer. People were arriving there either by big mining trucks through the road (?), or by helicopters sponsored by the USSR state…different times, different realities, but good food for imagination and of how our world has been changing.

Remnants of another era and a reminder of Global Changes… Glaciers were reaching the buildings of the year-round ski station that was flooded with people from Bishkek back in the Soviet times. Hard to imagine nowadays (Photo © Mike Styllas)

The Pamirs If the access to Ala Archa valley from Bishkek was short and easy, then our drive to the heart of the Pamirs proved to be long and difficult. Nevertheless, the two days of driving to reach Pic Lenin base camp, was an interesting northeast-to-southwest traverse of Kyrgyzstan. As one approaches the city of Osh, which stands there for 3,000 years, the route passes through ever-changing landscapes. For several kilometers, the road moves on the borderline with Uzbekistan. The more south we moved the more the Uzbek culture was becoming dominant, but anywhere in the landscape, we could spot the nomads and their yurts, as white dots into the green background.

Alternating landscapes on the drive to Osh, confirmed our initial view that Kyrgyzstan is culturally and geologically a diverse country. The golden hills were another piece in the puzzle (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

For novices to Pamir mountaineering reality, like ourselves, the arrival in Pic Lenin base camp by automobile, was an interesting experience. After crossing the extensive piedmont of the Pamirs through the bumpy dirt road, we were warmly welcomed by Michail, the base camp manager. Right away like all the aspiring summiteers of this 7000-meter peak, we were placed in already set tents. The whole setting resembled a tight and well-organized high-mountain camping, rather than a base camp. Nothing like we faced before, but again we were assured that this structure is another remnant of the Soviet style of mountaineering.

The whole setting was exhilarating with large glaciers originating at 7000m and terminating down to 3600m, making them accessible. The retreat of these monstrous rivers of ice and rock has done a great job in leaving behind huge moraines that we were called to surf down in our efforts to approach their terminus. Thanks to their sandy texture, it was fun to go down, but not easy to come back up. Aside such pleasurable moments, the daily challenge was to get out of base camp as early as possible in order to avoid the afternoon storms, which were of great severity. The heat of the extensive piedmont at the foot of the gigantic Pamirs, results in high rates of moisture build up, turbulence and instability, which are a daily phenomenon. Large cumulus clouds are formed rapidly, strike the mountains with thunder and lightning in an amazing speed. Several times, we got caught unprepared, as we were basking in the sun waiting for our experiments and incubations to finish and minutes after we were enveloped in the dark clouds with hail and rain coming along in a package deal. Our success rate to avoid this repeated pattern was destroyed by the fast moving storms and accounted for a mere 25%. After more than a week in this special location with Pic Lenin towering above our heads, we said goodbye to a few fellow mountaineers we met during our and stay, wished them good luck in their summit bids and moved on to the coastal region of Issyk-Kul lake in search of dry weather and warmer temperatures.

Fieldwork below the emblematic Pic Lenin, along with our support team. Despite the worrisome faces, this was the only day that we escaped the storm and were not drenched (Photo © Andrey Savinykh)

To the heart of the Nomads land Leaving behind the cosmopolitan Ala Archa valley and Pic Lenin base camp, we opted for the mountains above Issyk-Kul Lake, which have a smooth morphology and a special sense of solitude. Issyk-Kul Lake is listed in the world’s Top-10 largest and deepest lakes and is an important body of water for Kyrgyz people, as it is the most famous place for summer vacations by the water. Its extensive surface area is 11 times larger than Lac Leman and from the coastline, one can easily spot glaciated peaks. The lake never freezes in the winter and thus provides ample moisture for the adjacent mountains to be covered, not to say buried, with snow. The place is particularly cold during the winter, as it is struck by polar outbreaks that resume from the persistent Siberian anticyclone. Even though we knew that summer up there lasts for less than two months and that with this particular climatic setting, snow can fall anytime, we had to live through it, just to confirm the theory.

Vincent De Staercke greets a polar morning on August 15, 2021 in our Arabel Plateau camp (Photo © Mike Styllas)

The landscape in Ak Shirak and Arabel Plateaus is dominated by extensive flat areas, dissected by glacier-fed rivers and sparse bogs, where the cattle water themselves, bounded by a rolling topography and smooth valleys occupied by glaciers. Nomads and their yurts contemplate the visual monotony of the landscape. Their sheep and cattle along with the clouds were the only moving objects in this otherwise immobile scenery.

The vast Arable Plateau with its rolling topography and wetlands. Time seemed to be frozen there (Photo © Mike Styllas)

Surprises are everywhere though. On a rainy day when we had to strip down and cross a deep river, two young Shepard kids appeared out of nowhere riding their horse and donkey. They spotted us from the distance as we were trying to find a safe passage through the raging river and offered their equidae as a gesture of help and friendship. Struck by the Kyrgyz sense of solidarity in this vast and empty territory, the least we could offer was a cup of team in our base camp and a visual tour of our scientific equipment that triggered wonder in their sights.

Our fellow young shepherds appeared out of the blue and after donating their horse and donkey for us to cross the river, showed a particular interest in our scientific apparatus (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

Our scientific mission was heavy with an ambitious goal of visiting 10 glaciers in three different locations within these vast open spaces. Even though the distance and the elevation gain to reach the glaciers were not that great, we could succeed this goal without the help of our guide Andrey, and his team of young porters, Ruslan, Mirsaid and Nikita. Our success would have been diminished even more without the base camp support of our lovely cook Shasha and his team Elia, Boris (in Ala Archa), Timoja, and Nastia (in Arabel Plateau). For many years, Andrey has been involved in social work mainly working with orphans. Our team of young porters was a delicate pick from Andrey. Besides the heavy workload, it was an enlightening experience to talk with the young Kyrgyz generations about issues regarding their lifestyle, the way the see their mountains, their need to go abroad and their dispersed worries of the post 18-year old life. Bridging connections with the Kyrgyz youth left us with a very sweet taste of an expansion of our social horizons, as we had not experience anything similar in our previous expeditions.

From the anagram to the epilogue Tien Shan and Pamir Mountains, the Nomad, the yurts, the meat and cheese diet, the mix of Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Soviet temperaments, the clash of generations between western older and central Asian your people, briefly account for the colors that filled the canvas of our Kyrgyzstan expedition. However, the privileges do not stop there. The last time that our colleague Amy Holt from Florida State University had the chance to join us was in the volcanoes of Ecuador during pre-pandemic times. We shared a lot in the mountains of Ecuador, but since then we could only meet with each other virtually. Things worked out again and we were delighted to have spent this long lasting expedition with Amy on board. An additional member always brings new aura to the team. We admired her persistence in setting her molecular organic carbon analyses lab by her tent under any conditions, while the rest of us were seeking shelter in our warm sleeping bags. Scientifically speaking, it is very challenging to fingerprint the sources of carbon exported by the glaciers and we are happy having a small contribution to this effort.

Early morning delicate lab work involving organic carbon molecular analyses preparation. Pipettes were frozen but persistence wins. Delighted to have Amy Holt in our Kyrgyzstan expedition (Photo © Matteo Tolosano)

As in Nepal, it has been a great pleasure to share with Tom Battin an extensive period of this expedition as well. Conesus has been made that for scientific projects that involve a great deal of fieldwork like Vanishing Glaciers, it is fruitful and exciting for the fieldwork team to spend as much time as possible with the Principal Investigators out there. The angle is different, the discussions colorful and richer than in the campus and the bonding gets stronger, as we all have to live through the same tight situation, resulting from the weather, the local dietary habits, the cultural gaps and so on.

Our expedition would have not even started without the close collaboration with the Central Asian Institute of Applied Geosciences (CAIAG). We are thankful to Dr. Bolot Moldobekov, Dr Ryskul Usubaliev for their overall support to our project and particularly to Dr Nargiza Shaidyldaeva and Mr Ruslan Kenzhebaev, for running with us the bureaucratic ultramarathon in Bishkek.

Besides acquiring scientific knowledge through fundamental research, we are delighted for the cultural and social encounters and Kyrgyzstan was no exception to this rule (Photo © Tom J Battin)

With a great sense of accomplishment not only the scientific goals, but for expanding our vision of this world and understanding a bit more of how our world has been changing, we send our wishes to the EPFL community for a healthy fall semester.

MMMV

0 notes

Text

Majestic mountains under a shy sky

As far as Déjà vu goes, upon organizing the porters and shouldering our backpacks for the steep climb to Razek Hut, in Kyrgyzstan’s Ala Archa gorge, oblivion broke loose and the memories of our previous long lasting expedition resurfaced along with the desire to put thoughts into words…

Early morning bird view of the Majestic Himalayan peaks welcoming the team to Nepal © Tom Battin

The dawn was arriving and the plane was still crossing the large Indian Plane. The first sunrays were caressing the smog across this vast area, caused by seasonal wildfires and pollution. To the north, small white cones started appearing, while on the other side the large Himalayans Rivers with their muddy waters were flowing seemingly unhampered towards the Indian Ocean. As the plane turned to approach and land in Kathmandu, the mountains came closer and the shapes became clearer. Then the parade commenced…Dhaulagiris, Annapurnas, Manaslu, Lirung, Mount Everest, Lhotse, Makalu and many other giants protruding above the atmospheric planetary boundary layer, touching the Earth’s deep blue sky.

This was the seventh expedition of Vanishing Glaciers project and beforehand, everybody knew that it would be the hardest in terms of physical and mental strain. Working for successive weeks above 5000m, in harsh, cold and dusty environments, is not the typical fieldwork conditions that a scientist fancies on a regular basis.

For the first part of the expedition, we had the pleasure to be accompanied by the mastermind of the project Tom Battin, along with Fanny Arlanids and Sophie Rodriguez; two French journalists that were covering our Himalayan expedition for “Le Figaro Magazine”. This made things smooth as the first cold evenings in Langtang’s Kyanjin Gompa, were warmed by several interesting discussions off the science bounds. Once our companions left, we were left along to carry on with the task we were here for. To sample more than a dozen of glacier-fed streams from Langtang, Annapurna and Mount Everest regions.

The first encounters with the Asian reality of material transport and organization of loads, prior to our march in Langtang valley. Photo © Matteo Tolosano

Langtang valley was a revelation. It was the first time for most of our team members that came vis-à-vis with the Great Himalayan mountains. The bus ride from Kathmandu was an interesting introduction to the Asian reality of transportation. The loading of our equipment inside and on top of the bus made us look with awe the local rituals of space arrangement. Once on the road to the mountains, we witnessed the cultural transition as the Hindu culture gradually gave place to the Buddhist colorful prayer flags and prayer rolls. After an interesting 14-hour bus drive, we finally reached the end of the road and re-arranged the equipment to be transported by our team of porters. Within three days of hiking, semitropical forests with dense vegetation and wild bees hanging off large cliffs, gave place to subalpine and alpine vegetation, before the first glacial moraines appeared. Then, reality hit hard, as the first headaches became a sort of a new norm for the team and a slow acclimatization process was activated to prevent us from the worst. This was an interesting phase of the trip, with each member responding in a different way to the thin air.

On our third day, we reached Kyanjin Gompa, the last settlement of Langtang valley. Once a religious destination, but now the touristic capital of Langtang with excess infrastructure of lodges and small shops, Kyanjin Gomba offers close proximity to several glaciers. Our first target was Lirung glacier. This glacier has been a subject to frequent research due to its close proximity to the village. The whole setting was enchanting as 7000m peaks were towering above our heads.

Working under the Himalayan legendary peaks for two months, will always loom like a dream in our minds. Here, the team sampling water and sediment from the glacier streams draining the infamous Lhotse South Face towering at 8516 m a.s.l. Photo © Vincent De Staercke

After our second day of work, we got the warning shots of what was about to come, at least in terms of water runoff from our targeted glaciers, as the spring of 2021 never really came in the Himalayas. As we moved deeper into Langtang valley and set our base camp in Langshisha Kharka, a herder’s favorite spot, snow became a normality. On our daily long excursions from our base camp to the glaciers of Langtang valley, we would return in late afternoon to our base camp under a snowfall, only to find the courage to store the samples in the liquid nitrogen containers and lay down the plan of the next day. While we were taking care of our fieldwork chores and equipment preparation, Ambar our Sirdar, along with his team were making our lives much easier by pouring hot tea in our cups and feeding us with boiled potatoes and general doses of garlic to sustain our energy levels high. Once we passed the “Introduction Test” in Langtang valley, with minor symptoms summing up to coughing and fatigue, we returned to Kathmandu that was buzzing at the time, to store our samples and get some rest.

Recuperation was beneficial and after few days, we headed out again, much loaded with desire to explore and work in another valley. Our next destination was the Annapurna region. One of the most famous treks for many hikers around the world, the Annapurna Circuit highlights the crossing of Thorung La pass at 5416 m.a.s.l. Annapurna proved to be another foray in the classroom for our fieldwork tactics and physical limits. The drive to Manang through the bumpy, rocky and during the last stretch dusty road, crosses several exposed cliffs, which can bring nightmares even to the most calm and hopeful people. After two days of driving, we reached the village of Manang and from our lodge we could literally touch Gangapurna glacier. This glacier was extending close to the village of Manang only 54 years ago[1], before enhanced melting and the formation of a large proglacial lake begun due to an extended phase of climate warming.

[1] Konchar et al., 2015. Adapting to the Shadow of Annapurna: A Climate Tipping Point. Journal of Ethnobiology, 35(3): 449–471.

Gangapurna glacier, in the outskirts of Manang village. Photo © Vincent De Staercke

The landscape surrounding Manang valley with its stunning eolian landforms and erosional features. Photo © Martina Schön

Thorung La Pass (5416 m a.s.l.), an altitude record for some members of the team. Photo © Lhakpa Nuru Sherpa

After few days of working close to the ancient village of Manang, which is surrounded by a plethora of aeolian landforms and with small Gompas perched on these seemingly loose hills, we moved up the valley to work near Thorung La. The unusually cold spring conditions did not bring the normal glacier ice melt in elevations above 4500m and the glacier streams were still frozen. In a few cases, we had to break the ice to recover sediment from the ice covered streams. The highlight of this part of our expedition was the remote camp to the east of Thorung La. Cold, windy and occasionally sleepless nights gave place to majestic days and exposed us to the footprints of the snow leopard and to a great sense of isolation. The feeling of research and exploration was there with us and was very alive.

Advanced basecamp in the heart of Annapurna valley. A location away from the trekking highway of Annapurna Circuit granted us with some enchanting moments and a great sense of isolation. Photo © Vincent De Staercke

The return to the lower valley proved to be a challenging task for our team of porters and Sherpas, but mainly for ourselves. The idea to shortcut our return route to the lower valley was a unanimous decision. Ambar with the porters broke the camp and took the heavy loads down, as we were working on our last glacier of this area. Then we followed their track only to be surprised by the exposure and looseness of the terrain they had chosen. Upon crossing the most challenging part of our return route, philosophical wondering penetrated our minds…How can a man with 50kg on his back can walk down this steep and loose slope without any problems?

Though the answer was there: He is a Himalayan citizen, A Gurung, A Raj, A Tamang, A Sherpa!

The reputation that accompanies these people, as the hardmen of the highest mountains was justified in front of our eyes. Without their support, their kindness and their big smiles, not many expeditions, scientific or mountaineering, would have reached their goals. We are eternally grateful to these people and delighted that we spent moments sharing their thoughts and visions about their lives, their families, their mountains and the world itself.

Our team of porters kept impressing us with their easiness of walking down step and loose terrain with heavy loads on their backs, but mainly with their big smiles and positive attitude. Photo © Lhakpa Sherpa

Not having completely recovered from the exhilaration and fatigue of Annapurna valley, we opted for the final stretch of our expedition. The Khumbu valley - Mount Everest region. Surprises were different but this part was also full of them. The first highlight of the approach to Khumbu valley, the traditional home of the Sherpas, is the flight to Lukla. This is an experience that makes everybody tremble to various levels. As the small plane approaches the Lukla airstrip in the narrow gorge, passengers get the feeling that the winds of the small bird will touch the cliffs at some point. Then it all happens fast. The wheels come out under a violent sound, and the landing takes place in the up sloping airstrip, with the adrenaline rush discharging from the head through the toes. After a quick coffee in the nowadays-cosmic Lukla, to digest the flight experience, there followed two days of hiking under the rain and snow. The route from Lukla to the upper Khumbu valley, crosses several high suspension bridges and there at some point we arrived in Namche Bazar. In our first day in Namche Bazar, snowfall gave place to a sunny morning and we grasped the opportunity by hiking around Namche and exposed ourselves to the first breathtaking views of Mount Everest, guarded by Ama Dablam in the foreground. Rushing to complete our sampling plan, we moved higher in Khumbu valley and after another two days, we reached the otherwise magnificent Ama Dablam base camp. Once again, the climatic reality came hard on us and we were turned down for another time by the climatic conditions. Both Ama Dablam targeted glaciers proved dry, with no water recharge draining in their streams. This was a showcase of a high level of disappointment one can get, due to external factors. After climbing for 1500m to resume the fieldwork goals of the project, we realized that we were not able to do so due to climatic conditions. This left a bitter taste in our mouths and reminded us that the Himalayan reality can be tough in many different ways.

Snow welcoming us at the entrance of Mount Everest National Park was a precursor of the next weeks. Photo © Matteo Tolosano

Still optimistic to move forward and with adequate energy in our tanks, we left behind the Ama Dablam bitter experience and moved on to reach our next target; the village of Chukung. This settlement is composed only by few lodges and climbers arriving there aspire to either climb the 6153m summit of Island Peak, or they arrive from Amphu Laptsa pass, which at 5845m stands as the most challenging high pass of the Nepali Himalayas. To our benefit was the encounter with Island Peak climbing expedition members that broke the monotony of our small team’s everyday routine. Despite the fact that the glaciers were close to the settlement of Chukung, daily snowfall made the going hard and our electrical experimental equipment to deteriorate. While we were suffering the effects of cumulative fatigue after working for nearly two months in the Himalayas, news came that the Nepali Government imposed a complete lockdown in Kathmandu due to an unprecedentent increase in COVID-19 cases. This raised doubt among us, but no matter what, we did continue and concluded our fieldwork under Mount Everest’s iconic Khumbu glacier, battling the snowfall, the rain and a cloud covered sky along with the uncertainty of our return back to Switzerland.

Snow became our loyal companion in the Chukhung area (c) Vincent De Staercke

When we finally reached to Kathmandu by mid-May, we faced a different reality that resembled more of a ghost town than the buzzing crowded place we experienced before. Tuning up with the Buddhist mentality that we embraced for two months, we managed to turn frustration into patience and explosive thoughts to some kind of persistence. As for the first time in this project we were fighting to find our balance between positivism and despair, some crucial moves from Tom back in Lausanne, gave us the exit from Nepal after 2.5 unforgettable months that still shine in our minds as The Expedition that had it all. Friendly and hospitable people, big glaciers, exposure to high altitude, cold, snow, rain, fatigue a good dose of coughing, but most important enchanting fieldwork experiences that took place in the majestic Himalayan mountains under an overall shy sky.

During the lockdown, pigeons were the only visitors of the otherwise crowded Patan’s Durbar square © Martina Schön

Even though the sun did not smile to us a lot in Nepal, the first part of our Kyrgyzstan expedition proves to be the opposite so far…

Best wishes for a nice summer!

Martina, Matteo, Mike & Vincent

1 note

·

View note

Text

When hours turn to days

The fieldwork season of last summer was long and smooth. The end of September found us giving our Centennial Ice Kiss in the Massif des Ecrins and celebrating the midway milestone of Vanishing Glaciers fieldwork ultramarathon.

The infamous Langtang glacier. Photo © Vincent De Staercke

The period from October 2020 to the moment that these words slip out of the mind and typed into the keyboard, involved reducing physical activity, but an increasingly heavy load of science in its widest spectrum. The lab work intensified and the entire team involved in the project soon realized that the countless hours of tedious samples’ analyses, give place to days of statistical processing, hypothesis testing, discussions and writing. Then, it takes even more days for the project’s manuscripts to be published.

I guess this is normal, and it looks like the obscured transition from hours to days, came to stay with us not only in the lab and along the manuscript publication continuum. In early March, we embarked for the “Crown” of the Vanishing Glaciers project expedition. The Himalayas. Truth is that before this expedition, we were arranging our fieldwork tactics and approach times to the glaciers in hours. But here the things are augmented in many different ways, as the scales are humongous. We now realize that the hours previously needed to reach the streams fed by the glaciers, have turned into days…and in many occasions into many days.

Privileged to have Tom on board, we lived through the first shock of the hours-to-days fieldwork reality and completed the first leg of this lengthy expedition, working in the glaciers of Langtang valley. Dealing with our usual preparation chores, tomorrow we set off for the second leg in the Annapurna region, feeling a bit more in tune with this new tempo.

Vanishing Glaciers fieldwork team in front of Kyimoshung glacier (Photo © Sophie Rodriguez)

As we get infatuated by the diffuse fieldwork pace, the gigantic Himalayan summits, and by the glaciers that flow down from them, we send to the EPFL community our warmest greetings from warm and hospitable Nepal!

Mike, Martina, Matteo, Vincent and Tom

0 notes

Text

A fascinating trip to Antarctica

Researchers from EPFL have been joining the Belgian Antarctic Research Expedition to Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station every year since 2016. Armin Sigmund, a PhD student in the Laboratory of Cryospheric Sciences, recently participated in the expedition to study snow-atmosphere interactions. After coming back from the extreme and impressive environments of Antarctica, he provided insights into his first trip to the polar regions.

Uncertainties before the journey

To reach Antarctica in the exceptional year of 2020, we had to manage additional challenges. Until my arrival in Antarctica at the end of November 2020, it was always a bit uncertain whether my trip was going to take place because of the risk of getting infected by the new coronavirus. Due to the limited medical care in Antarctica, we had to do everything to avoid bringing the virus to this remote continent.

After two weeks of quarantine in South Africa and multiple tests for Covid-19, we were ready for the flight to Antarctica. However, we still had to be patient because the flight was postponed due to bad weather conditions. Finally, the exciting day arrived and a big cargo plane brought us to the cold and white continent.

Arrival in Antarctica

I was particularly excited because I had never been to the polar regions before. Although the weather was sunny, I was expecting cold temperatures. So I put on my warmest clothes before leaving the plane at the Novolazarevskaya (Novo) runway in East Antarctica. From there, we were to continue the journey with a smaller plane. It was a good decision to wear the warmest clothes because a strong and cold wind welcomed us.

Arrival in Antarctica. Drifting snow is visible near the surface (Photo © Martin Leitl, IPF).

I was fascinated by the streams of drifting snow, which moved quickly along the snow surface. This process is at the heart of our research and it reminded me of the goals of my trip. The transport of snow particles by the wind increases the amount of snow that is removed from the Antarctic ice sheet by sublimation (transfer to water vapour). An important goal of our project is to quantify the contribution of sublimation to the surface mass balance of Antarctica, which can help to improve predictions of sea level rise. To achieve this goal, we need both simulations and measurements, and performing the measurements was the mission of my trip.

Impressive landscape

During the flight from Novo to Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station, the plane window offered a fantastic view on the huge ice sheet. From time to time, crevasses were visible below us and impressive mountains appeared at some distance.

The Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station is located in a nice scenery with mountains towards the South and a flat snow surface towards the North. Unfortunately, we were too far away from the coast to see penguins. Nevertheless, we observed other animals that choose to live at that remote location: Birds, which find a protected home in the mountains.

The landscape at Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station (Photo © Martin Leitl, IPF).

Life in Antarctica

The Belgian Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station is a zero emission station operated by the International Polar Foundation (IPF). Thanks to solar and wind energy, the rooms were warm and comfortable and freshwater was made available by melting snow. I enjoyed the fresh and delicious food that was prepared every day.

As we had all gone through a quarantine before the trip, there was no need for wearing face masks and and avoiding social gatherings in Antarctica. It was nice: In this regard, life was more normal in Antarctica than at home in Europe. Another interesting experience was the absence of the sunset. There was daylight all the time although the station was in the shadow of a mountain for a while in the late evening.

Fieldwork at the “end of the world”

In the beginning of my three-week stay, it was sunny and the wind velocity was low. This weather was ideal for taking high-resolution aerial photographs of the snow surface using a professional mapping drone. In combination with GPS measurement, we use these photographs to quantify changes in surface elevation over periods of several days or a whole year.

Preparing the drone measurements (Photo © Martin Leitl, IPF).

The drone at take-off (Photo © Preben Van Overmeiren, Ghent University).

While being in the field, it was important to protect the face with sun screen because of the particularly intense UV radiation in Antarctica. Even on cloudy days, it was possible to get a bad burn.

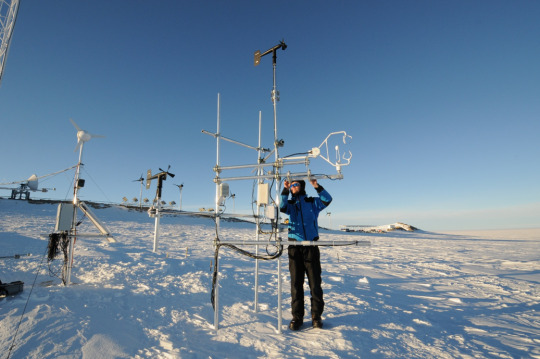

Four years ago, my colleagues had installed two automatic measurement stations to collect weather- and snow-related data throughout the year. My task was to relocate one of these stations, to connect it to the more reliable power system of the Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station, and to install additional sensors. I was happy that I could rely on the great help of other expedition members.

Setting up one of the measurement stations at its new location (Photo © Henri Robert, IPF).

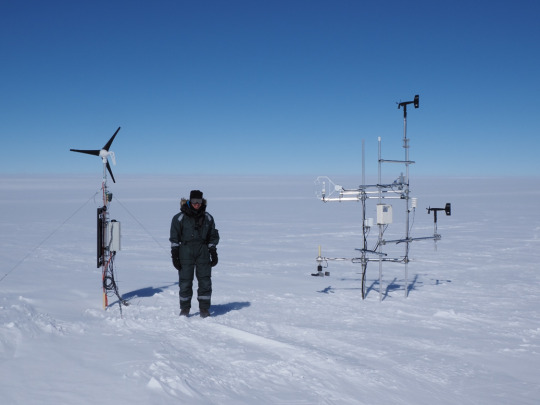

The other measurement station is located at the edge of the Antarctic plateau, approximately 40 kilometres away from the Princess Elisabeth Antarctica. The conditions at that site are usually more extreme because it is colder and directly exposed to the katabatic winds coming from the interior of the continent.

On the way to the measurement station, we travelled through the mountains and enjoyed a lot of fantastic views. The first time we went there, the weather was not as extreme as I expected. The temperature was about -17 °C and luckily the wind was rather calm. We made good progress with lifting the measurement system and replacing the solar panel and the batteries of the station.

Working at the edge of the Antarctic plateau (Photo © Preben Van Overmeiren, Ghent University).

During the following week, the wind was too strong and the visibility was too low for a second trip the distant measurement station. Luckily, the weather was favourable during the last few days of my stay. So we went out there again to replace the wind generator and resume the measurements.

However, there was an unexpected problem with the wiring of the instruments. Unfortunately, two instruments were still not powered, when we left the measurement station in the evening.

I was nervous because my departure was approaching and there was only one more chance to travel to the measurement station. The following morning, when we arrived at the edge of the Antarctic plateau, I got an impression of the typical windy and harsh conditions at this location. Finally, I managed to power the last two instruments by connecting one wire in a different way. What a relief!

Final measurement setup at the edge of the Antarctic plateau (Photo © Martin Leitl, IPF).

Overall, it was a nice and exciting time in Antarctica and I am grateful for the support from the expedition team, from my colleagues at EPFL and the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in Davos, and from the Swiss Polar Institute.

0 notes

Text

The Centennial Ice Kiss

It has been already two years since Tom layed down the sampling strategy the project…” You arrive to the snout of the glacier, kiss the ice, walk back ten meters and set up your sampling station”. At that point, it was hard to imagine that this proposition would become a normality and eventually set up the tempo of the project. It took some time for the pace of the fieldwork to be in-phase with that of the lab and now everyone has a good reason to celebrate 100 ice kisses of the earth’s Vanishing Glaciers.

Celebrating the sampling of 100 glaciers in the ice front of Glacier de Bonne Pierre, Parc National des Ecrins, French Alps. (Photo © Vincent De Staercke)

Common to climbing expeditions is the motto “it’s all about the trip not the destination”, but in the science realm, this rhetorical is skewed towards the destination. The iterative cycle of our project starts in the seemingly lifeless terminus of the world’s alpine glaciers, with in situ measurements, experiments, collection of microbial-laden sediment samples and their transportation back home in deep frozen state. The loop continues in the lab with the tedious analyses of a great deal of microbiological and biogeochemical parameters, finding an exit through publications.

Of course, in a flowing life, like the glacier streams we study, nothing is at steady state. Upon return form our Ecuador expedition, the new COVID-19 pandemic broke loose. We all felt flashed frozen, exactly like the microbes we collect from the glacier streams when we dump them in the liquid nitrogen. Unlike these minute forms of life thawed in the lab to decode their lives’ secrets, the summer thaw of the long confinement brought much needed action. The lab work got on fire, but the expedition radius was confined within the European continent, encircling the European Alps and the Norwegian mountains.

At the snout of Tuftebreen; one of the many outlet glaciers of the Jostedalsbreen ice cap in Southern Norway (Photo © Martina Schoen)

A special science project brings special moments for those involved and especially for the one in lead. There is always a unique, albeit sensitive balance between objectives and achievements. While the former remain solid, The Centennial Ice Kiss will be metabolized into fuel for the marathon like long stretches in the lab and for the coming expeditions to the Himalayas, Pamirs, Patagonia and to the mountains of Alaska.

With a sense of achievement, we send our best wishes to the entire EPFL community for a smooth and productive fall and winter seasons.

Mike, Martina, Matteo & Vincent

0 notes

Text

Drifting through the ice on board a polar climate research vessel

The German research icebreaker Polarstern has been drifting through the frozen waters of the Arctic Ocean since September last year. Julia Schmale, an atmospheric scientist from EPFL, joined the crew two months ago to study cloud formations and their role in local and global climate change.

More than two months ago, EPFL researcher Julia Schmale joined the crew of the Polarstern, a German research icebreaker that has been drifting slowly through the frozen waters starting north of Siberia towards Svalbard since September last year. The vessel is carrying an international team of scientists on a year-long research expedition, working in unusual and often challenging conditions: changeable weather, temperatures plummeting as low as –40°C, interminable darkness giving way to endless daylight, and ice as far as the eye can see.

The crew is carrying out research as part of a major expedition titled Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, or MOSAiC for short, which aims to gain fundamental insights into conditions in the Arctic, the impact of climate change on the region and vice versa the region’s influence on global climate change.

Schmale, an atmospheric scientist, is leading the observatory’s atmospheric research team. She had planned a mid-April return to Switzerland, where she was recently appointed head of the brand-new Extreme Environments Research Laboratory at EPFL, but the COVID-19 crisis means she will remain on board until early June. Schmale is no stranger to polar environments, having taken part in the Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition (ACE) in 2017. Her role in this latest expedition is to study how airborne molecules and particles influence cloud formations in the Arctic. In this interview, she talks to us from the front line about living and working in this extreme environment, what it’s like to head out onto the ice floe, and the aims and methods of her research.

- What’s it like living and working on the ice?

“Unpredictable. The icescape changes frequently and new cracks, leads and ridges form overnight, often preventing us from reaching our research sites on the ice. Depending on how severe the changes are, we might need to go scouting for a new route or reschedule whatever activities we had planned. Sometimes the ice becomes dynamic during the day while we’re out. When that happens, we either have to keep a close eye on our path back to the ship or we get called back by the bridge, where the on-board team coordinates and monitors activities out on the ice. Before we head out, we always complete a trip log detailing who’s going where, what gear they’re carrying and – importantly – who’s acting as the polar bear guard. Most of us are qualified polar bear guards, a role that involves keeping a permanent lookout while our colleagues are working. We carry a flare gun to scare any bears away, as well as a rifle to use if an animal approaches us too quickly. On 23 April, we saw the first bear on our floe since we arrived in early March.

The environment is just beautiful. It was still dark when we arrived, with only a slither of daylight on the horizon. The research sites on the floe looked far away, but they were easy to reach across flat ice. Now, with the sun up 24 hours a day, everything seems much closer. But moving about is much harder because many leads and cracks have formed, especially between the ship and our team’s main research site. With temperatures at around –20°C, open leads freeze over relatively quickly – about 6 cm in one day. Sometimes, ridges form when open leads close and we can end up surrounded by ice rising up to 6 meters high in just a couple of hours. On occasion, we can hear the ice moving and, if it happens fast, we can also see it. It’s also fascinating to watch frost flowers grow. We sample them to learn about their biogeochemistry.