Ehren Stanhope, CFA, is a Principal at O'Shaughnessy Asset Management. He examines investment themes that are informed by deep historical research and are timely given the current market environment.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Current State of Affairs for Value, Profits, and Debt

The woes of value investors reached a new peak today. A well known institutionally-oriented value shop decided to close its doors at year end. The firm has been around for decades and at its peak managed tens of billions of dollars.

For the most part, both Value’s underperformance during the crisis can be explained by sector composition. The panel below shows a time series of sector composition for the cheapest value decile, most expensive value decile, and highest-ranking momentum decile.

There are a few key takeaways from these visuals. First, cheap value has a disproportionate allocation to Financials and Energy—both acutely impacted by the crisis—with low allocations to Info Tech. Conversely, expensive value has a disproportionately high exposure to Info Tech and Health Care and low ones to Financials and Energy. Lastly, although high-ranking momentum’s sector allocation was not as favorable as expensive value, it did have a sizeable weight to Info Tech and an increasing trend to Health Care and Communication Services while reducing exposure to Financials and Industrials.

How Value Rewards

In “Factors from Scratch” we decomposed the historical performance of Value and Growth into their component parts—Return of Capital, Fundamental Growth, and Multiple Expansion. Return of Capital consists of dividends and buybacks. Fundamental Growth represents EPS growth, and Multiple Expansion is measured as the impact of the change in the P/E ratio. From 1965-2019, value derived its edge from higher levels of Return of Capital. Fundamental Growth was a detractor, and Multiple Expansion was effectively a wash.

Over the last two years, however, Fundamental Growth has weakened for both categories relative to history. Value’s Return of Capital advantage contracted while Growth’s Fundamental advantage widened. The key driver of Growth’s outperformance has been Multiple Expansion. Value’s multiples shrunk and Growth’s expanded, a spread of 7.03% annualized.[1]

Value’s Recovery Underperformance

P/E multiples can be viewed as the price per $1 in earnings per share, which allows us to extrapolate that multiple expansion over the last two years was driven by an increase in price.[2] Price can be thought of on a per share basis, or as the stock’s overall market capitalization. In either case, both market cap and price per share theoretically represent an investors’ collective measure of the present value of all future cash flows associated with the stock.

Discount rates, which can be approximated using bond yields, are a key contributor to present value calculations. We can see below that the real yield for Treasury Inflation Protected Securities has fallen roughly 2.3% from the recent peak in late 2018. Falling rates mean falling discount rates, which is generally supportive of higher valuations.

However, multiples are not rewarded evenly. Value stocks are generally cheap because their underlying businesses are not expected to grow at the rate of their Growth peers. In our present value calculation, this suggests that near-term earnings are more meaningful for Value than Growth. In a situation like the COVID-19 crisis, when Value’s near-term earnings are severely impaired, discount rates are falling, and Growth’s earnings are expanding, it’s a perfect Growth-leadership cocktail.

Using S&P 500 index dividend futures, we can back into the short-term (next five years) and long-term (5 years and beyond) components of the S&P 500’s value using pre-crisis and current yields. The left-most chart in the panel below shows the change in value of the short and long-term components of the S&P 500’s market cap using prevailing discount rates since the start of the year. Notice that the short-term component has declined in value while the long-term component has risen. The rise is tied to the decrease in yields, as can be seen in the middle panel, which have shifted down during the crisis. The right-most chart in the panel shows what would happen to the components if we applied pre-crisis yields today. The analysis suggests the long-term component would be 23.5% lower.

Unfortunately, we are unable to dissect the Value vs Growth dynamic in this analysis because dividend futures don’t exist on those indexes, but we can infer that the impact on the long-term component of valuations would likely disproportionately impact growth stocks.

All of this suggests that higher long-term rates may cause a shift in the Value-Growth dynamic. With the Fed’s pause on Fed Funds for the foreseeable future and massive fiscal stimulus ongoing, it is not inconceivable that we could see higher rates at the long end of the curve, which would favor Value.

Debt and Profitability

Another point that bears noting in this environment is the prominence of unprofitable firms and massive debt issuance. The third quarter marked the largest debt issuance binge on record—$267 billion for investment grade corporates and $119 billion for High Yield. The surge is evident when looking at the U.S. stock universe. What is notable is that when dividend into two cohorts, profitable and unprofitable companies, the unprofitable ones are taking on more debt with greater leverage. Probably, not going to end well and argues strongly for an active approach in the coming years.

[1] The analysis concludes in 2019 due to the extreme aberrations in Q1 and Q2 earnings data related to the COVID crisis.

[2] Another way for multiples to expand would be for earnings to decline, but that’s not the case here

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Do Markets Go Up?

Stock markets are the greatest compounders of wealth the world has ever seen. The key objective of any investor is to get more than $1 back for every $1 invested. Sadly, most introductory investment courses and literature do not begin with an explanation as to why markets go up. It’s such a fundamental question, but it is often overlooked. With greater understanding as to why, it may well prove easier to stay invested when “Mr. Market” goes on a binge and lops 20% off the value of your portfolio.

Think of the U.S. stock market as one holding company named USA, Inc.[1] that holds a portfolio of businesses. If you were the CEO of this holding company, you would have two jobs. First, ensure profits are generated by the underlying businesses. Second, reinvest those profits in the best interests of the company’s owners. To do so, you would seek investments that grow USA, Inc.’s future earnings—like starting, expanding, acquiring, and/or selling businesses. If opportunities for those activities weren’t enticing, you might offer a dividend or repurchase shares outstanding (an implicit bet on the portfolio companies of USA, Inc. itself).

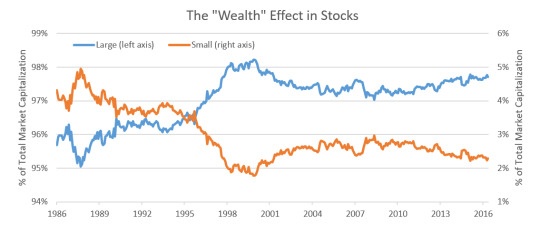

USA, Inc. has done a remarkable job of all this over time, but not in the ways you might expect. First, the reallocation of capital via dividends is more important to return than the underlying earnings generated themselves. Second, demographic and long-term economic forces drive earnings persistently higher.

Let me explain.

Earnings Growth, Dividends, and Valuation Multiples

Since 1871, the earnings of USA, Inc. have grown by 3.99% annually.[2] We can think of earnings growth as the first of three sources of return to the investor.[3] Keep in mind that this growth is for the entire portfolio of USA, Inc.’s businesses. Some businesses within the portfolio grew at dramatically higher rates and some at much lower rates, but they averaged out to 3.99%.

Dividends account for the second source of return. If we assume that shareholders of USA, Inc. reinvested their dividends, that reinvestment would tack 4.55% annually onto the 3.99% of earnings growth, bringing total return to shareholders at 8.54%. Note that the contribution of dividends is greater than from underlying earnings growth. That seems strange. How can reinvestment be more important than the underlying earnings upon which dividends are generated?

One potential reason is that dividends, when reinvested, represent a redistribution of underutilized capital to firms that may have higher earnings growth rates. Dividend payers tend to be more mature firms, while non-dividend payers may be growing at a pace that requires all capital to be ploughed back into the business. Here’s an example. In a hypothetical two firm market, firm A is a young Technology company growing earnings at 20% per year. Firm B is a mature Consumer Staples firm growing earnings at 3% per year. Firm A is in growth mode and offers no dividend. Firm B offers a 3% yield to entice investors. Firm A is smaller and has a market capitalization of $5 billion. Firm B has a market cap of $10 billion. When Firm B issues its 3% dividend, $300 million gets paid to shareholders. Those who choose to reinvest do so pro rata—~33% to Firm A ($100 mil) and ~66% to Firm B ($200 mil). Because Firm B paid a dividend, $100 mil more is now invested in Firm A than would have otherwise been if no dividend were paid. $100 million has been reallocated to a more efficient use—a higher earnings growth firm.

The third component of return, which is more transient, is directly related to the valuation placed on the stream of earnings and dividends generated by USA, Inc.’s portfolio of businesses at different points in time.

The value of any company should theoretically be the combined value of 1) its existing business persisting into the future, and 2) a speculative component that represents the market’s guesstimate of the present value of future growth. That’s a mouthful so let’s dig in.

The simplest valuation measure is the price paid for each $1 of earnings generated by the company, commonly referred to as the Price-to-Earnings, or PE, ratio. In 1871, the PE for the market was 11.1x. At the end of 2018, it was 22.3x, which means the multiple “expanded” 0.47% per year. Unfortunately, multiples don’t always expand in linear fashion; we have simply smoothed the impact by annualizing the change.

Valuation multiples oscillate between expansion and contraction for the very reason that they are attempting to value the future, and the best guess of the future is constantly evolving (see chart below). It should be noted, however, that except in extreme circumstances like the tech bubble on the high end and the 1970’s on the low end, the PE ratios tend to revert to the long-run average of about 15x. Forecasting is an inherently difficult exercise for obvious reasons. It is unknown. The ability to do so would require a forecaster to accurately predict future cash flows, interest rates, and inflation—among a suite of other variables.

Add multiple expansion to the 8.54% generated via earnings and dividends, and we arrive at 9.01%, the annualized total investor return for the market (USA, Inc.) since 1871.

So, why do markets appreciate over time? Because earnings have grown over the very long term, dividends are paid—and when reinvested—are powerful additional contributors to return that implicitly reallocate capital. Finally, markets value the stream of earnings and dividends from the market differently at various points time. Changes in this valuation result in multiple expansion or contraction, which makes up for the balance of total investor returns.

The Three Components of Growth

Though we’ve broken down total investor return to show why markets go up, we have not addressed the second-order question— “what causes earnings to grow?”[4]

To answer this, we will assume that the S&P 500 Index is a decent proxy for the overall economy. This turns out to be a pretty good assumption, as the business sector represents 75% of GDP.[5] We also need to invoke three economic forces—inflation, productivity, and demographics.

Inflationary forces result from increases in costs—i.e. labor or raw materials—when demand overwhelms supply.[6] Over the very long term, these get passed along to the consumer via price hikes. The classic analog being too much money chasing too few goods. A little bit of persistent inflation can be good—it encourages consumption that fuels the economy, and it diminishes the future burden of debt repayments. Conversely, demand can decrease, resulting in deflation. Deflation is bad because it deters spending in favor of excessive saving (see Japan), and it increases the future burden of debt repayments.

Productivity generally results from either efficiency gains or value creation.[7] If a technological advancement allowed a worker to increase output to two widgets per hour from one, that’s a measurable doubling of productivity. Value creation would be the invention of something totally new, i.e. the internet. Productivity is amazing because more value is created with the same or fewer inputs than would otherwise have been possible. For the most part, productivity tend to be a gradual force. Productivity, defined as Real GDP per Capita, has grown consistently in the 2% range for many decades.[8]

Inflation tends to be more volatile—with a notable decade-long spike in the 1970’s—but has increased at around 3% on average. Inflation often lays the foundation upon which productivity induced innovation creates value, and so the two are interlinked forces. Inflation drives up costs, which necessitates a more efficient means of production, which increases profits, which attracts competitors into the market, which lower profits, which drives investment out of the space until a new, more efficient means of production is discovered and the cycle repeats.

Here is an example where this plays out in the real world—education. Until the advent of online classrooms, there were no noticeable productivity gains in education over the last several decades (I suspect longer, but don’t have the data!). The only way to increase educational productivity was to hire more teachers to teach more students in a physical space at a time. There are practical limits to this endeavor. In the last two decades, more students with loan-fueled pocket books have been attending school than ever—increase in demand without a commensurate increase in supply, resulting in inflation. Since 1947, higher education costs in the U.S. have grown dramatically faster than across the rest of the economy (5.7% versus 3.0%).[9] Enter online classrooms, which have no physical constraints, and they are contributing to lower educational inflation in recent years.

Demographic trends, though boring due to their glacial pace, are important because labor is often the most expensive component of production. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it represents more than 60% of the value of economic output.[10] Labor means workers. Workers are a part of the population. Growing populations will have more eligible workers in the future. Workers earn wages which they spend to support their growing families and lifestyle. Demographic headwinds and tailwinds can be identified by simply understanding the change in the overall population, or a subset—like workers employed.

Using these three forces, we can break down GDP into its component parts. I have shortened the time frame here to 1947-2018 for ease of access to Federal Reserve data. Over this period, nominal GDP has grown by 6.36% per year. That can be broken down into our three forces—Inflation 3.25%, Productivity 1.95%, and Population Growth 1.16%. When combined Productivity and Population Growth constitute Real GDP, which has grown at 3.11%.

We can then recategorize the drivers of market return in economic growth terms. To level set, here is the table from above but with a shortened timeframe of 1947-2018 and adding a column for inflation-adjusted data.

The data point we seek to explain is real earnings growth of 3.42% using the forces of Productivity and Population Growth. Notice that it is relatively close to the 3.11% real GDP growth number above. Productivity in the business sector differs from that of the overall economy in that the labor force is smaller than an entire country’s population. Here again, demographic trends play a role because the working age population ebbs and flows with generational birth trends. For business Productivity, we look to real corporate output relative to nonfarm payrolls. Over our time frame, business Productivity has grown at a 1.64% clip, accounting for slightly less than half of real earnings growth of the S&P 500.

The Population Growth component of real earnings has grown by 1.73% over this period, slightly more than half. Though I haven’t dived into it extensively, I suspect that the higher contribution for business versus real GDP is due to women entering the workforce in the latter half of the twentieth century.[11] The women’s labor force participation rate nearly doubled from 35% in 1950 to 60% in 2000, which means the labor force grew at a greater rate than the overall population.

At our firm, we spend a lot of time thinking about the characteristics of stocks that predispose them to outperform over time. We’ve found that attempting to predict first order results—like returns—is generally a fool’s errand. There are too many variables. However, if you can identify characteristics that are more stable—like underlying earnings—you can increase your odds of laying proper wagers on one or a portfolio of stocks.

When I look at the previous table, the stable and more predictable measure that jumps out at me is population growth. As noted before, its glacial and persistent. Given birth rates today, one can fairly reasonably predict what the labor force will look like in 10, 20, 30 years. Which is also to say that one can also potentially predict, with reasonable confidence, one major contributor to real earnings growth.[12]

Snow fall, Navigation, and Grinding Higher

I grew up in New Orleans. Besides being the Mecca of everything music, food, and culture, it happens to sit near the mouth of one of the greatest commerce thuways on the planet, the Mississippi River.

Kids love big, fast stuff, and I was no different. Watching the tanker ships glide by was a favorite pass time when we went downtown. There’s something pretty magical about hundreds of thousands of pounds moving in complete silence and seemingly effortlessly. What makes it even better is when those big tankers move fast. Naturally, I asked how all this was possible.

I learned a few things about rivers, navigation, and delayed gratification at a young age. First, the water tends to be higher in spring because all the snow from winter up north melts and fills the river. Second, more snow = more water = faster current = faster ships = cooler to watch.

At some point I realized that the cool factor was predictable. When it snowed an inordinate amount in January, the river was higher and the current moved faster. And the icing on the cake, a ship can only steer when it is moving faster than the current. So if the current was moving quick, ships moved even faster in April. This was a predictable cycle. It didn’t repeat every single year, but thematically, it has persisted since time immemorial.

Markets do tend to go up over time, but in cycles. While I think there is a decent portion of the population that still thinks markets are unpredictable casinos, there are fundamental trends at play that justify the continued rise of markets for decades to come—demographic trends and productivity gains.

Though imperfect in many ways, capitalism generally works. Businesses generate profits. Successful businesses employee people. Employees earn wages. They spend those wages to support their lifestyles, often raising a family. Inflation persists at a low rate, but periodically crops up as generational waves (i.e. Baby Boomers) stress the capacity of an economy. As new trends take shape, preferences change. Technological innovation occurs, resulting in disruption to the status quo and new value creation. Hopefully, in their quest for maximizing shareholder return, businesses continue to allocate to these new innovations, spurring relentless productivity gains over decades, and pushing markets higher.

—

[1] I use the S&P 500 Index as a proxy for USA, Inc.

[2] Irrational Exuberance [Princeton University Press 2000, Broadway Books 2001, 2nd ed., 2005]

[3] This approach was developed by my colleagues in a research paper titled “Factors from Scratch”.

[4] https://www.oaktreecapital.com/docs/default-source/memos/2015-09-09-its-not-easy.pdf

[5] https://www.bls.gov/lpc/faqs.htm#P01

[6] In economics there are the paradigms of financial markets and goods markets. Though the requisite balance of demand and supply apply in both markets, the mechanism by which inflation/deflation occurs is different. For example, in financial markets, inflation (deflation) can be generated via excess (deficient) monetary supply with no real change in the goods market. For the purposes of this piece, I refer primarily to the goods markets.

[7] http://reactionwheel.net/2019/01/schumpeter-on-strategy.html

[8] How the Economic Machine Works

[9] Federal Reserve Economic Data

[10] https://www.bls.gov/lpc/faqs.htm#P01

[11] https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2017/women-in-the-workforce-before-during-and-after-the-great-recession/pdf/women-in-the-workforce-before-during-and-after-the-great-recession.pdf

[12] The BLS offers a report every two years which lays out their projections for growth of the labor force. The most recent projection can be found here.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where is the Value?

Investors always want to know what’s cheap—cheap relative to the opportunity set and relative to history. Cheapness could refer to any number of things—price relative to trailing twelve months earnings, to trailing earnings over multiple years, to analyst earnings estimates, to long-run projections, or a dozen other variations based on sales, cash flows, book value, etc.

Because analyst estimates tend to be tainted for a number of different reasons (see this discussion on why), we tend to focus on price relative to trailing twelve month sales, cash flows, and earnings to measure cheapness. This gives a more holistic and objective view of valuation.

Using this simple construct, we’ll give every investable stock across the globe a percentile valuation score from 1-100. Scores are then rolled up to countries and regions to get value scores for each relative to the entire global stock market. Our universe will be all stocks with a market cap greater than an inflation adjusted $1 billion (USD) and with reasonable daily liquidity from 1990-2018.*

Because developed and emerging markets are often treated differently, we’ll separate the two within each region. Some countries are such large portions of the overall global stock market that they warrant their own “region”, i.e. the U.S. and Japan.

The chart below summarizes the results. Each green column represents a region/country. The vertical axis are the average percentile scores for each region/country discussed above. The top of each region column is the highest (most expensive) valuation since 1990, and the bottom is the lowest (cheapest). The red triangle represents the average valuation over the period, and the blue triangle represents current valuations.

As value investors, the most intriguing regions/countries are those with current valuations (blue triangle) below the historical average (red triangle) and low relative to the rest of the global market. Based on this chart, Japan and Emerging Europe, Middle East, Africa (EMEA) fall into this group. On the flip side, the U.S. stands out as being one of the most expensive markets relative to other regions and its own history. Given the massive run in the U.S. market over the last decade, this is no surprise.

Over the last several decades, it is common for there to be long cyclical trends of U.S. outperformance. Since the 1970’s at least, it has always reverted to form with non-U.S. markets outperforming for long stretches. Below is a chart of rolling 3 year returns for U.S. vs Foreign markets. At some point, the tide will change and foreign markets will have their day in the sun. Timing uncertain.

Regions give a decent overview but drilling down by countries within each region reveals some interesting stuff. Let’s turn first to the broadest region—EMEA. Obviously, Europe has been afflicted by several political events in the post Global Financial Crisis (GFC) era. Grexit, Brexit, questions on solvency in Italy, Spain, Portugal, etc. Setting all that aside, there are three countries that are trading reasonably below their historical averages and relative to others in the region—Portugal, Greece, and Turkey. These countries are not for the faint of heart, but then again, opportunities tend to require a contrarian bent form investors that can see through the noise.

Turning to the Asia Pacific region, there are a few standouts. For developed markets, Japan and Singapore are both trading well below their historical average and with discounted valuation relative to other countries. On the EM side, Russia is the clear winner—cheap relative to history and within the region. With high economic reliance on the Energy sector, a volatile currency, and a few political concerns, the valuation seems to make sense, but certainly worthy of a closer look.

Turning to the Americas, as mentioned above the U.S. appears expensive relative to history and other countries/regions, but that has been the case for some time and could persist. Of interest on this side of the Atlantic is Mexico. A little ways into The Absent Superpower, author Peter Zeihan makes a succinct case for an industrial revolution in Mexico based on the U.S. shale revolution.

Long story short, there seem to be more opportunities, based on valuation, in Emerging Markets. Among Developed Markets, Japan seems the most attractive. The U.S. remains expensive.

We could stop there, but there is always more to the story. Value investing is great, but there exist lots of value traps the world over. An interesting corollary to value investing is that of growth. Peter Lynch famously quantified this concept in the PE to Growth ratio. Basically, what are you paying for a dollar of earnings growth. We extend this concept below by using the same Value score framework and adding to it some growth metrics. We will measure Earnings Growth using a combination of 1-year EPS change, Return on Invested Capital, the trend of earnings over the last several quarters. The chart below shows the percentile ranks for value on the horizontal axis and Earnings Growth on the vertical axis. A country with the highest growth and cheapest valuation would fall int eh lower left corner. Expensive and low growth countries would fall in the upper right corner.

I’ve highlighted a few countries on the chart that I found interesting. The countries noted above as being deeply discounted relative to peers and history are also showing up as having favorable Earnings Growth relative to peers—Portugal, Greece, and Russia.

For the most part, if you can find discounted stocks with strengthening fundamentals, you usually have a solid cocktail for a good investment. For enterprising investors willing to bear the currency and geopolitical risks, there may just be some diamonds in the rough in some of these unloved and beaten down markets.

* If you don’t see a country, its likely because there weren’t enough tradeable stocks to warrant inclusion. China being a prime example here. Lots of stocks that aren’t tradeable to foreign investors.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

False Promises: Going Passive is Not Momentum Investing

There is some popular marketing spin going around that indexing—constructing portfolios based on market-cap weights—is effective because it allows an investor to own more of companies that have been successful and appreciated, while moving away from losers that have been unsuccessful and declined.

This sounds logical, but it is empirically wrong.

The strategy suggested above is tantamount to a diluted form of momentum investing, which seeks stocks that have appreciated recently and avoid those that have fallen in price.

But the devil is in the details. The above is false because it doesn’t take into account the investment horizon over which indexes hold positions and the momentum factor delivers return.

Let’s look at the data.

Momentum investing does work over time. The below creates a series of momentum portfolios—strong momentum on the left, poor momentum on the right. Strong momentum stocks do, in fact, outperform while weak momentum stocks underperform.

But, lets take a deeper dive. If you invest in a strong momentum name (decile 1 above), how does the outperformance come? Does it all come in the next month, 6-months, 12-months, 2 years? How long does the signal remain effective before you need to move out of that momentum name and into another strong momentum name?

The chart below answers the question. It is the information horizon for momentum investing using 12-month momentum. The logic would go as follows. If someone finds a strong momentum stock and makes an investment, on average, how will they get rewarded, relative to the market.

If you made an investment in one of the top 3 momentum portfolios at time 0 and held it for 36 months, this would be your average cumulative return relative to the market at each holding period-- 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months.

As you can see, excess return (return better than the market) peaks at about 10 months. Then you see a decline in the strongest momentum decile. This is reversion to mean in action. Whatever the behavioral phenomenon—I would say it’s initial excessive optimism— that originally drove the misprising has worked itself out and performance has reverted. If the investor holds the strong momentum stock too long, that outperformance erodes and even turns negative.

In other words, if you don't move out of momentum names, you will end up underperforming.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say the optimal holding period, selling at the peak, is 12 months. This suggests that the entire "strongest momentum" portfolio must turn over every 12 months--100% turnover to realize the benefits of momentum. For the middling momentum deciles, it needs to turnover even faster.

Last I checked, no passive cap-weighted indexes have anything near 100% turnover. If they did, it would be completely antithetical to their objective, low cost exposure to the market. It is empirically impossible for low turnover cap-weighted indexes to provide value-add momentum exposure over a market cycle.

In fact, over longer periods, they actually provide the opposite! Why? Because the turnover for passive funds is 3%, not 100%! (Turnover of SPY per Morningstar). A 3% turnover implies a holding period of 33 years. I wonder what the momentum horizon looks like over 33 years?

Because the holding period is so long, cap-weighted strategies can actually have negative contribution from momentum over long periods. Here’s why... compounding. The excess return (outperformance) for an investor in the strongest momentum decile peaks at 2.17% in month 10, but then goes on to lose all the gains by month 21 and then produce underperformance for a cumulative return of -1.49% in month 27.

A more nuanced implication of the Investment Horizon chart is that more of your capital is “at risk” at the peak of this curve than at the bottom. If you have more money at risk before a downturn in performance, it stands to reason that all of those gains erode and you eventually end up in a worse position than when you started.

This phenomenon is why investors would actually be much better off in an annually rebalanced equal-weighted portfolio. A portfolio that set each position at the same weight for one year (approximately the optimal momentum holding period) implicitly buys into beaten down names ("Weakest Momentum" in the chart below) that could be about to revert in the information horizon and sells ones that have appreciated to the peak of the horizon ("Strongest Momentum" in chart below).

Don’t believe the spin, passive cap-weighted products are market exposure, not momentum investing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dimensions of Return

This post originally appeared on osam.com as part of a new push to accelerate the velocity of our firm's research and tackle "big" questions in investing.

There are three universal dimensions of return that drive the performance of all strategies—regardless of investment style or asset class: consistency, magnitude, and conviction. These dimensions serve as levers that can increase or decrease performance of any strategy. They also provide context for why portfolios are constructed in the manner that they are. This piece will attempt to create a framework for evaluation and to identify which of the dimensions have a disproportionate influence on performance. In applying the framework to the Russell 1000® and 2000® Value, and the top and bottom large and small cap managers, I find that the dimensions provide insight as to which skills differentiate top and bottom professional managers.

Investing in any asset class, be it public equities or seed stage venture capital consists of two critical decisions: what to buy and sell (selection) and in what proportions (weighting). To understand the drivers of return, an investor must disaggregate the impacts of these selection and weighting decisions. Selection decisions can be evaluated through the dimensions of consistency and magnitude. Weighting decisions can be evaluated through the dimension of conviction.

Having studied markets for almost two decades, I have found the existing knowledge base to be abundant on investment selection and sparse on weighting, or portfolio construction. This piece breaks with existing literature, which conflates the effects of selection and weighting decisions in an overarching assessment of “skill”. Evaluating selection and weighting as distinct skills provides unique insight into what drives manager returns, and how active manager returns might be improved with no additional improvement in selection abilities. My hope is that this framework contributes to the portfolio construction literature as an alternative perspective to the theoretically beautiful, but over-utilized and impractical, modern portfolio theory

Before we can get into the practical application, bear with me as I build intuition for the framework. Caution: there is some math involved. If Greek letters evoke some inner anxiety, skip over the equations and focus on the concepts.

CONSISTENCY – HOW OFTEN POSITIONS WIN

Consistency measures the performance impact of how often winning investments are selected.

The return of a portfolio over any holding period is the weighted average of the underlying position returns and weights. If a position is held at a 1% weight and it appreciates 10% over the holding period, its contribution to return is 0.1% (1% X 10%). The sum of all individual contributions is the portfolio return, which is the weighted average of position returns:

To isolate consistency, we need to level the playing field across portfolio positions by neutralizing the investor’s expression of preference for one investment over another through position weights. This can be done by assuming that each position receives the same weight. When you assume positions have the same weight, you get the portfolio’s equal-weighted return, defined as:

The equal-weighted portfolio is the simplest expression of neutrality because its weighting scheme suggests that the expected probability of some investment outcome is the same for each position. Said another way, uncertainty as to which investments will win or lose is at its maximum. The outcome has nothing to do with manager skill beyond simply selecting the investments from a wider opportunity set. To understand the connection between expected outcomes and how positions are weighted, we can look to probability and information theory.

In attempting to predict the outcome of a fair coin toss—fair in the sense that each toss is 50% likely to be heads or tails—there exists no edge to betting on one outcome over the other, despite our behavioral biases to the contrary. The chart below illustrates the amount of uncertainty as the outcome of the toss becomes more certain, either a tails or heads outcome. Notice how uncertainty (measured on the vertical axis) falls as the probability of tossing heads (moving to the right on the horizontal axis) or tails (moving to the left) increases. As uncertainty decreases, an investor should revise his bets accordingly by increasing the wager—more on this later when we discuss the weighting component of skill. But for now, our equal-weighted portfolio is evaluated as if it were a series of fair coin tosses where each position either wins or loses.

We can break out the winning and losing positions from the equal-weighted portfolio return in equation (2) as follows:

After some manipulation, we can derive the average return of winners and losers as:

Knowing the number of winning and losing positions in a portfolio is useful because it allows you to calculate a batting average. The batting average quantifies how often a manager picks winners. It is a measure of breadth of wins across the portfolio and is the yard stick for consistency.

A batting average can be generated relative to any objective—a benchmark index, a fixed return, or just whether a positive return is produced. The batting average (𝐵𝑝) can be defined for a given holding period as:

All else equal, a manager with a higher win rate will outperform one with a lower win rate.1

The impact of consistency in investment selection is most easily thought about in terms of its extremes—a manager that wins often, and one that loses frequently. On one extreme, Manager A in the table below implements a strategy where 99 out of 100 of her picks produce a win. Her batting average is 99%. On the other extreme, Manager B implements a strategy where 1 out of 100 of his picks produces a win. His batting average is just 1%. Given the choice between Manager A and B, most people would select Manager A, as A seems like a sure bet. This betrays an inherent bias to oversimplify complex problems. Given a batting average, most think of 100 equally placed bets, perhaps $1 each with even money odds—bet $1, win $1. In that context, Manager A would effectively double her money, while Manager B loses almost everything:

In this example the entire difference in return can be explained through the dimension of consistency. This should be intuitive given that the only variable introduced is a different batting average.

To determine the contribution to return from consistency (𝑅𝐶), we multiply the difference between the batting average and 50% with the difference between the average win and loss. 50% is important because it represents the dividing line between winning more than losing.

𝑅𝐶 is the amount of a portfolio’s return generated from winning more often than losing. All else equal, the impact of consistency improvements are linearly related to portfolio return as the batting average improvement multiplied by the difference in average wins and losses.

MAGNITUDE – WIN BY MORE THAN LOSERS LOSE

As it currently stands, our manager performance narrative is incomplete. What if the winnings do not result in equal payouts? If Manager B’s single win was a two hundred bagger—returning 20,000%—and his other positions were total losses, his return would be 101% (1% x 20,000% + 99% x -100%). Similarly, if Manager A’s wins only generated a 2.5% return and her losses were 50%, her portfolio return would be just 2.0% (99% x 2.5% + 1% x -50%). Consistency alone does not define a manager. To add to our narrative, we need to provision for the magnitude of wins versus losses.

The contribution to return from the magnitude (𝑅𝑀) of winning versus losing positions is defined as:

Here, we assume that the winning positions and losing positions have equal influence on the portfolio’s return. This again harkens back to our idea of neutrality. Assuming that a manager is equally likely to pick a winner or a loser aids in disaggregating the impact of the magnitude of wins versus losses.

Given the dimensions of consistency and magnitude, one can build intuition for how different types of investors select investments, and the risks for which they need to be aware. Extending our example above, Manager A generates small frequent wins and large periodic losses, a return profile that is similar to insurers, but which can be extrapolated to option portfolios. Insurers effectively write short put option portfolios against a wide range of risks. Their upside is known and consistent, while their downside is unknown and unlimited, but estimate-able and infrequent.

Manager B is at the opposite end of the spectrum, generating infrequent large wins and lots of small losses. This is similar to the return profile of a Venture Capital fund in which a few big wins often pay for all the failed bets in spades. At a basic level, VC’s invest in portfolios of call options with a known limited downside, but unknown, unlimited, and infrequent upside.2 It is important to note here that the return profiles of insurers and venture firms are unique corner cases on a spectrum of investment styles where more mainstream asset classes fall somewhere in the middle. I say this because, when combined, the payoff diagrams above equate to that of a simple long stock position.

That said, the return profiles of insurance and venture managers can be stylized using consistency and magnitude even though there is a strong case to be made that Venture returns are distributed according to Power Law distributions. Beyond certain limits, power law distributions have no theoretical mean or variance. This clearly poses problems within the framework presented here as the analysis is dependent on the mean, or average. This is an area that deserves a deeper dive and further research. Jerry Neumann, on his blog Reaction Wheel, has presented a compelling case that venture outcomes follow Power Law distributions.3

To the Insurance and Venture examples, I add bond and stock portfolios below. Bond portfolios generally have very high batting averages with favorable average wins to losses. Stock portfolios feature batting averages closer to 50% with favorable, but more volatile average wins to losses.

As mentioned previously, these two dimensions evaluate the impact of investment selection decisions. It turns out there is a relationship between the two. Consistency and magnitude are proportional components which sum to the equal-weighted return of the portfolio: 𝑅𝑒w = 𝑅𝐶 + 𝑅𝑀. As such, improvements in the consistency of wins can only increase return to the limit of the average win in the portfolio. In other words, consistency can only drive so much improvement. When the investor’s batting average hits the natural limit of 100%, consistency and magnitude become equal contributors to portfolio return.

All else equal, the impact of improvements in magnitude are also linearly related to portfolio return as the average of the change in wins and losses.

This is reflected in the following chart. The light blue lines represent improvements in the batting average (moving from left to right) given a static set of average wins and losses. For example, the highest light blue line shows the impact of a batting average improvement based on average wins of 10% versus average losses of -5%. The dark line represents improvement in both consistency and magnitude. Notice that it is non-linear, which suggests that there is leverage in simultaneous improvements in more than one dimension.

This occurs because of the symbiotic relationship between consistency and magnitude. Together they represent an investor’s skill in stock selection. Improvements in one or both will drive the portfolio’s equal weighted return 𝑅𝑒w higher.

Equations (7a) and (8a) quantify the impact from changes in consistency and magnitude individually. Realistically, that does not happen. Let’s say an investor runs an analysis and finds her batting average is poor. If she wants to improve upon it, there are two approaches. She can either attempt to select more winners— improve the numerator in her batting average—or, she can attempt to do a better job of screening out losers— lower the denominator in her batting average. Both methods, if successful, will improve her overall batting average. I refer to the latter as pruning. Just as trees periodically require removing dead branches to improve overall health, investors aught look at their processes to prune the waste.

Naturally, this has implications for concentration within portfolios. It even suggests that there is some optimal level of concentration based on a particular strategy’s batting average and magnitude.

In either case, the improvement has to capture two effects, the improvement in the batting average, and the difference in average wins versus losses from either bringing in new winners or eliminating losers. As such the combined improvement to 𝑅𝐶 and 𝑅𝑀 can be modeled as:

CONVICTION – PLAYING TO STRENGTHS

Conviction is the X factor in portfolio performance. Whereas consistency and magnitude can only be improved through the challenging exercise of better investment selection, conviction can improve performance outcomes with no additional skill in the investor’s selection abilities.

Conviction evaluates the relationship between position weights and investment outcomes. The concept is predicated on the assumption that information content is inherent in the weight of a position. This requires a departure from our previously established concept of neutrality. All else equal, a high position weight suggests greater confidence on the part of the investor in a successful investment outcome than for a lower weighted position. Unfortunately, investor confidence, conveyed through the position weight, may not always align with reality. A classic example of this calibration error would be the well-documented bias towards overconfidence in one’s decision-making abilities. A corollary is that underconfidence, or undue conservatism, can also negatively impact performance by leaving return on the table when the distribution of potential outcomes suggests being more aggressive.

Let’s say, for example, that Venture Firms A and B regularly co-invest and have decided on the same set of investments. From their own historical experience, they know that about 1/3 of investments fail to return any capital, 1/3 break even and return the invested capital, and 1/3 deliver a 200% return on capital.4 At the outset, the firms have no way to reliably differentiate between which investments will fall into each group, so they equal-weight the investments. Let’s assume that investments proceeding with additional “up” financing rounds—Series A, B, C—are more likely to persist to a successful venture exit. In the decomposition of outcomes below, Venture Firm A makes the decision to equal-weight all investments after the Series A round despite the evidence that some of those investments are more likely to be successful. The expected return for its portfolio is 78%, or 12% annualized over five years. Venture Firm B recognizes that after a successful Series A round, those investments are probabilistically more likely to be winners. The expected return for its portfolio is a significantly greater 124%, or 17% annualized.

Clearly, the expected return of Firm A is significantly understated relative to Firm B, which is to say that Firm A’s portfolio construction approach likely leaves a lot of return on the table by under-allocating to winners. However, there is another subtle, but important point. Assuming investment outcomes played out as the probabilities suggest, Firm B’s portfolio would exhibit higher correlation between position weights and ex-post investment outcomes.5

Conviction is relatively easy to define, but complicated to evaluate because it represents the convergence of portfolio construction decisions and investment outcomes. The contribution to return from the investor’s conviction (𝑅𝐾)—deviation from equal-weighting—is defined as:

In our venture example, Firm A does not deviate from equal-weighted so there would be no contribution to return from conviction. The difference in expected returns of the two firms, however, is completely explained by differences in conviction. As such, conviction can be defined even more simply as the difference between the weighted-average and equal-weighted portfolio return:

Now that we’ve defined each of the three dimensions, we find that they are additive and should sum to the portfolio return over a given holding period.

Impact attributable to conviction can result from either manager-driven portfolio construction decisions, as in our example, or spurious exogenous shocks that increase correlation between position weights and returns. For simplicity, I assume that any shocks are short-lived, independent, and mean-reverting over time, allowing us to focus on the effects of manager-driven weighting decisions.

To illustrate the return impact of varying levels of conviction, I create ten hypothetical portfolios which differ only by the degree of conviction applied to the portfolio’s weights.6 The graphic below charts the position weights on the vertical axis for each portfolio from highest on the left to lowest on the right. For example, the portfolio represented by the dark blue line suggests about a 3% weight in its highest conviction position, and a 0.5% weight in its lowest conviction name.

I then introduce look-ahead bias to create three sets of randomly generated position returns.7 The returns differ only in their level of correlation with position weights. The first set is uncorrelated with position weights— correlation of 0.0. This functions as a control set whereby our expectation is that the investor’s conviction has no bearing on performance. The second set has a positive correlation with position weights of +0.1. This replicates a scenario in which an investor’s confidence is somewhat aligned with investment outcomes; she is skilled. The third set has a negative correlation with position weights of -0.1—suggestive of a manager who is overconfident in weighting decisions and is unskilled.

The chart below plots the portfolio return at each level of conviction for the skilled, uncorrelated, and unskilled investors. Conviction is plotted on the horizontal axis and increases from left to right. As is expected, the control portfolio with uncorrelated weights and returns delivers the same performance despite the level of conviction. The skilled manager with appropriate and realistic conviction (correlation +0.1) is progressively rewarded as his expression of conviction increases. Conversely, the unskilled manager (correlation -0.1) is penalized as his conviction/overconfidence increases.

This highlights that even slight deviations—correlation of +0.1 is not particularly large—can have a significant impact. In this case, the hypothetical portfolio with a slight positive correlation outperforms an equal-weighted portfolio by 2.7%—exact same securities, different weighting scheme. The payoff for expressing confidence is symmetric with the skilled manager outperforming by 2.7% and the unskilled manager underperforming by -2.7%.

While normal, bell-shaped distributions are great for theoretical exercises, they generally do not reflect reality. For example, if an equity investor were formulating an investment strategy and had to choose between two opportunity sets, he would likely face the choice represented in the table below. In this case he would probably always choose Option 2—higher average return, higher batting average, better magnitude in average positive versus negative return. Option 2 is statistically “skewed” in the investors favor.

From this opportunity set, an investor would then apply some conviction framework to weight the names. Option 2 differs from our hypothetical example in that it is a skewed distribution that is approximately, but not perfectly, normal. The data above is taken directly from monthly returns of US stocks from 1987-2017. Option 1 are all large stocks. Option 2 is a subset of cheap large stocks as measured by sales, earnings, and cash flows.

SO WHAT?

One useful purpose for the framework is in identifying skilled and unskilled managers within a competitive peer group. The dimensions framework quantifies the value add from investment selection (consistency and magnitude) as opposed to portfolio construction (conviction).

As we have seen, portfolios of the exact same underlying investments can yield very different performance depending on the manager’s ability to align position weights with ex-post investment outcomes expressed through conviction. One would think that managers which use a process-driven portfolio construction methodology should deliver value-add on the conviction dimension over time.

To test this thesis, I pulled positions and returns for the top 20 and bottom 20 managers from Morningstar’s U.S. Large Value and Small Value peer groups for the 5 years ending December 31, 2017.8While an analyst could theoretically evaluate a strategy over any time frame, I look at rolling one-year periods. Public equity managers are attempting to beat indexes, and most equity indexes rebalance once annually, which aligns with a one-year buy and hold. The benchmark for the peer groups are the Russell 1000® Value and Russell 2000® Value Indexes.

To level set, below are the contributions to return by dimension for these benchmarks for the 5-year period from 2013-2017.9

The indexes generate most of their return from consistency. Though there is no explicit empirical tie to beta, I interpret this as exposure to a broad market category—large value or small value. Magnitude is a much smaller contributor but is probably analogous to style exposures—value or growth. Conviction is the smallest contributor. As we established earlier, this contribution should only be significant in the presence of investor skill. Since the average correlation between benchmark weights and forward position returns is 0.0 for the Russell 1000® Value and Russell 2000® Value over the analysis period, it seems safe to conclude there is no “skill” implied in their cap-weighted construction.

How do professional active managers stack up? The answer is, as always, “it depends”. The scatter plot below shows the top and bottom large value managers from Morningstar. The vertical axis plots the contribution to total return over the last five years from conviction, while the horizontal axis shows consistency and magnitude (investment selection).

What is readily apparent in large value is that most managers, even the top ones, are not able to differentiate themselves through conviction. For the majority, the dimension is a net detractor from performance, which suggests their skill in portfolio construction is poor. In fact, most would be better off simply equal-weighting their portfolios. Notice though, that the top and bottom managers are clustered into two groups. Dots further to the right generate greater return from selection. What does it take to excel in the equity US large value space? Be a really good stock picker

It turns out though, that is not universally true across equity asset classes. Moving down capitalization to a less efficient space, small value, and the results are a bit different. The scatter plot below shows the same analysis, but on top and bottom small value universes.

As compared to the large value chart, a few things jump out. Dispersion is much greater at the bottom end of small than large value. Large and small managers generate roughly the same amount of return from investment selection, but small value managers appear to be more skilled at portfolio construction. The majority of small value managers plot above the 0 line on conviction, suggesting portfolio construction is additive to performance.

The analysis above is by no means exhaustive. This is just one five-year period among many, and a particularly difficult one for professional managers. Future research would apply this analysis more broadly in the equity space to growth and non-U.S. managers, as well as expanding to other asset classes—fixed income, venture, and private equity portfolios.

CONCLUSIONS

This framework should be useful for both allocators and investment managers. Allocators are always seeking managers with robust processes that have the ability to deliver alpha over time. This framework provides a quantitative process whereby allocators can identify manager skill in certain areas, selection and portfolio construction. In our work studying value factors, one of the things that has surprised us is that most companies we study have negative free cash flow yield yet can still go on to produce strong investment returns. Because of this, when we see companies with strong and sustainable free cash flow, we try to figure out what structural advantages exist. Conviction is the free cash flow of manager analysis. Some managers succeed in spite of their poor skill in portfolio construction. Some managers thrive because of it. Why is this important? Because skill in conviction is all about the manager’s process, something he/she can control to amplify existing skills. Conversely, investment selection, is a wait-and-see affair.

For professional managers, the inferences from the analysis can be used to aid in refining their portfolio construction processes. While it would be impossible to suggest managers to get better at predicting the future, I do think it is fair to suggest that investors can do a better job of understanding the distributions of their own investment outcomes. If an analysis shows even mild positive correlations (+0.1), it could be a massive contributor to their advantage versus other managers. If its negative, the investor should set hubris aside and equal-weight their portfolio until they can develop a reliable and repeatable portfolio construction methodology

FOOTNOTES:

1 The batting average, which is always a percentage from 0 to 100%, can be used to reconstruct the equal-weighted return of the portfolio by proportionally weighting the average of wins and losses from equations (4) and (5): Rew = BpRw + (1-Bp)Rl

2 In both cases, insurance and venture capital, provisions are put in place by managers to tilt the odds of success in their favor. Insurers place policy limits to limit losses and Venture Capital firms insert liquidity preferences to mitigate losses on their investment. In both cases, risk is shifted to the counterparty—policyholders and founders, respectively.

3 See references to Reaction Wheel.

4 “What Is A Good Venture Return?” http://avc.com/2009/03/what-is-a-good-venture-return/.

5 Grinblatt and Titman (1993) find that a positive covariance means that active weights are large for securities with positive excess return, which they interpret as a measure of skill in security selection. I extrapolate the finding to correlation effects, but attribute to skill in conviction (portfolio construction) rather than selection.

6 The weighting scheme is determined through a decay rate meant to represent an investor’s degree of conviction in positions. Weights are determined by re-weighting the results of a formula for logarithmic decay: wi = -d ln(i) + wmax where d = a decay rate and wmax = the maximum allowable position weight

7 Returns are log-normally distributed with a mean and standard deviation of 10% and 15%, annualized. Approximately half will outperform the mean and half will underperform

8 To determine the top and bottom 20 managers, I excluded duplicate mutual fund share classes, enhanced index strategies, and strategies with greater than 500 holdings. Portfolios are reweighted to exclude cash holdings.

9 I chose this time period purposefully because it has been an exceptionally difficult period for active managers. In extending the analysis back ten years I found similar conclusions, however, the ten-year period encompasses the financial crisis which does skew the results.

REFERENCES:

Kelly, J. L., “A New Interpretation of the Information Rate”. The Bell System Technical Journal. July 1956.

Shannon, Claude E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” The Bell System Technical Journal. October 1948.

Grinblatt, Mark & Titman, Sheridan, 1993. "Performance Measurement without Benchmarks: An Examination of Mutual Fund Returns," The Journal of Business, University of Chicago Press, vol. 66(1), pages 47-68, January.

Colin, Andrew. “Portfolio Attribution for Equity and Fixed Income Securities”. Chapter 5, Smoothing Algorithms. Amazon. 2014.

“Entrepreneurship and the U.S. Economy”. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/bdm/entrepreneurship/entrepreneurship.htm

“Venture Outcome are Even More Skewed Than You Think”. VCAdventure. https://www.sethlevine.com/archives/2014/08/venture-outcomes-are-even-more-skewed-than-you-think.html

“Power Laws: How Nonlinear Relationships Amplify Results.” Farnham Street. https://www.fs.blog/2017/11/power-laws/

“Power laws in Venture”. Reaction Wheel. http://reactionwheel.net/2015/06/power-laws-in-venture.html

“Power Laws in Venture Portfolio Construction”. Reaction Wheel. http://reactionwheel.net/2017/12/power-laws-in-venture-portfolio-construction.html

“Applying Decision Analysis to Venture Investing” Clint Korver, Class 14. Kaufman Fellows Press. https://www.kauffmanfellows.org/journal_posts/applying-decision-analysis-to-venture-investing/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Breaking up is Easy To Do

This post is a bit of an experiment. My good friend Steven Wood and I started discussing some collaborations a few months ago. We hope that it ups the quality of our research and also brings some new insights into each of our philosophies. Below is his recent post, for which I helped provide some research on the performance of spin-offs, which was popularized by Joel Greenblatt in the mid 2000's.

One of the most common questions I receive when talking to allocators and advisors is "Have you found factors that just stop working?" I think this post helps answer that question.

When Breaking Up Is Easy To Do

March 29, 2018 Steven Wood

We get by with a little help from our friends. The back-testing for this article was done by our dear friend, Ehren Stanhope who writes a great blog, factorinvestor.com. This is the first of what we hope will be many collaborations with Ehren, and we thank him for his generous data-crunching on our behalf.

Speed Read:

Returns from spinoffs are no longer categorically great, but when they work, they WORK

When the clown car (hedge fund crowd) goes left, we go right.

Nearly ¾ of our portfolio is undergoing some type of split in the coming years.

One has to go where there is no competition. Always.

Healthy Break Ups

Your author grew up in a traditional catholic household, in which the Italian-born mother was more comfortable with the F-word than she was with the D-word. The word which must not be named was “divorce,” and our mouths were washed out with soap if we let it slip out.

Yet at the same time, quite paradoxically, numerous relatives showed that separations not only can sometimes make both sides happier but also healthier people. This was the first, of many, paradoxes noticed within Catholic dogma.

In a very similar vein, investors who push for corporate separations are often relegated to the “short-term profit maximizing,” bucket which we so staunchly despise. The evidence supporting long-term thinking and decision-making is large, growing, and nearly irrefutable. We disagree with many activists which call for company separations merely to take a quick buck and move on.

We disagreed with Jana’s insistence that Whole Foods sell itself, though once Amazon decided to enter the physical grocery space, we did eventually prefer to not compete against that combination and were happy to sell our shares to Amazon.

Despite the bad name given to “break it up,” activists, there are in fact many businesses which make sense to stand apart from each other. Of course, the pioneer researcher of spin-offs is Joel Greenblatt, who wrote the tome on the subject You Can Be A Stock Market Genius.

Your author read it in 2004, nearly identically matching the peak interest in the book and special situations in general. In perhaps my first contra-indicator move, I took the bait and joined a Special Situations fund straight out of Tulane. That school was also where I first met Ehren, who generously crunched the data contained in this analysis. I hadn’t even seen the performance of the fund, I simply knew the type of investing made sense and spoke to me.

Apparently, it did for everyone else too.

From Conglomerates to Splits

In January of 1997, Joel Greenblatt published Stock Market Genius. Not coincidentally, it followed less than 18 months after ITT, one of the largest and most famous conglomerates announced it would split itself into three units. The ITT breakup was the tombstone that capped the terrible reputation that conglomerates came to have. Just a few months after Stock Market Genius debuted, ITT announced another 3-way split and the era of conglomerate had officially given way to the era of the spinoff.

Greenblatt cited third party research which claimed that spinoffs outperformed the market by 10% per year and then offered some case studies on what particularly worked well. Studies that have been published since the publishing of the book have confirmed 10-20% outperformance of the spun companies. Indeed, Stanhope’s data suggests this “rule of thumb,” still holds.

Exhibit 1: Spinoff & Parent Excess Performance (vs. S&P 500) 1996-2017

Kellogg Capital Group’s Special Situation Group, the family office your author joined out of university, generated outstanding returns following similar strategies, compounding at 41.8% per year. When you generate performance like that, you create friends for life. While one PM wished to remain anonymous, I’d like to publicly thank Co-PM Jeff Anderson and his partner for giving this naive fool an early education. Yet, as the contra-indicator comment suggested, the “discounts” on these event-driven situations had completely collapsed and by the time I joined the fund, there were very few new ideas to look at. I added zero value.

Exhibit 2: KCG’s Special Situations Group Returns

The Climax

Greenblatt’s own hedge fund at the time had compounded returns above 50%, outstanding performance that invited herds of investors to join the cult. Even had he not written the book, we suspect these returns would have been diminished as word spread of the performance and the strategy, but the book officially killed the category.

But it took a while. While we only have Google trends data going back to 2014, it was right around 2014 or 2015 that the steady stream of ideas had completely dried up. Sure, there were still spin-offs, but they would no longer sell-off. The valuations of such securities were driven to abnormally high levels, as the herd of investors chasing >50% returns crowded out the value guys.

Exhibit 3: Google Trend Data for Key Terms

Opportunities dried up, and we had a much harder time finding attractive special situations candidates. We had to look for similar types of opportunities, but ones that hadn’t formally announced a spin or split. Yet all the “confirmatory” studies on whether or not spinoffs still generated excess returns suggested the category was still attractive and still outperformed the index. That ran counter to our experience.

Curious to know if our personal experience was backed by empirical data, we spliced the same data above by a pre-craze and post-craze time period. We identify 2004 as the year of “peak,” interest in Greenblatt, Special Situations and Spinoffs as measured by Google Trends. While Greenblatt’s early 2006 interest eclipsed the mid 2004 experience, it was in conjunction with the launch of his second book, The Little Book That Beats the Market, where he didn’t refer to special situations strategies. Thus, we isolated 2004 as the point of maximum interest in these strategies to see how spin-offs before and after such a period performed.

The empirical data confirmed our suspicions, by a long shot.

The Let Down

Exhibit 4: Excess Performance of Spinoffs by Vintage

Splicing the exact same data as shown in exhibit 1 shows a completely different experience. The retrospective studies all included the best years in the sample. This hid the more lackluster performance that was being experienced by the same exact strategy in subsequent years. This empirical data is why we constantly catch ourselves rolling our eyes at “backtested,” strategies as if they were predictive of future returns.

This data also matches the experience of the Guggenheim ETF (CSD) that was created to buy spinoffs a couple years after the climax. Returns have been fairly languid relative to the overall index.

Exhibit 5: Guggenheim S&P Spin-Off ETF (CSD) vs. S&P 500

The data analyzing the performance of the parent is similar, the strategy performed slightly better before the Special Situations craze had climaxed, yet still remained a fairly lackluster way to generate alpha.

Exhibit 6: Excess Performance of Parent Companies by Vintage

When everyone is crowding into the clown car, it’s time to pump the brakes. Being contrarian, even against the “contrarians,” is of the utmost importance.

However, we’re not saying one needs to give up on the category. In fact, of the 2005-2017 cohort of spinoffs, 48% outperformed the market two years after the spin. But it is no longer a “set it and forget it,” strategy, and each opportunity requires serious scrutiny.

When the Clown Car Goes Left, We Go Right

Our experience with splits has been very positive and quite a bit different that that of the overall spinoff sample size. Yet, we’ve been keen to look for hidden assets within companies rather than wait for the actual announcement of a split to come. Of course, this means that we’re taking transaction “risk,” in the event a split isn’t announced. And that’s ok for us, we’re not often investing based on a catalyst (we are post-catalyst investors). Rather, if there are assets within a company that the market is choosing to ignore, that is not only our opportunity, but if we back good managers, they will tend to create value from these assets over time.

Often times, however, the easiest way to build value is to actually split. There are innumerable reasons why a split may be better for each individual situation. Often times it’s allowing a unit to access a cheaper cost of capital, other times it’s in order to hire an independent management team that myopically focuses on value creation of the individual unit.

Isn’t it interesting that in preparation for the spin-off of Ferrari, FCA had to fire its complacent manager and install Sergio Marchionne as head of the unit? The company could have easily lifted deliveries sooner, given the waiting lists had dragged past two years for its performance models, but it took a public debut for the company to step on the gas. Ferrari currently trades for 3x the market capitalization of FCA when we bought it, not to mention the positive performance FCA has since posted.

Exhibit 7: FCA-Ferrari Performance Vs Peers

Yet, quite opposite from most special situations in the US pursuing “strategic alternatives,” when we purchased our stake in 2011 and 2012, FCA was in an “untouchable” area given it was a leveraged auto company in Italy. Three strikes, and it was out for nearly all global investors. In fact, it was a favorite short among London hedge funds. If we remember correctly, the short pitch at Ira Sohn London was that, “it’s just shitty.”

Sometimes, though not often, it pays to be a contrarian against contrarians.

Renaissance

Now that most roll ups have completely blown up (we think Kraft-Heinz is next), the last few decades of GE have completely unwound, and the historical performance of spin-offs has deteriorated so thoroughly, we think breakups are about to stage a comeback.

We still think all of the useful lessons learned from the last decade of lackluster category returns apply. Given the competition for catalysts, we need to invest before any split has been announced or is apparent. Furthermore, starting valuations need to be constructive and we need to stay contrarian.

Each of our top five holdings (~55% of our portfolio excluding the coinvestment, ~75% including the coinvestment as our largest position) has quite mistakenly ended up in splitsville. EXOR’s FCA is about to spinoff its parts division, and its CNH unit is preparing to fix its Iveco truck unit to spin it out. TripAdvisor has had approaches for multiple units within its business, though here we agree with Aristotle, and think the sum of the parts is greater than the whole.

“The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” – Aristotle

Telecom Italia is preparing the separation of its network infrastructure from the retail arm, and despite an activist fund coming in and “demanding” that TI split itself, had it actually met with the chairman, it would have known this was already in motion. Investors can see our notes from our meeting with the chairman last week here. We believe the group is headed for a New-Zealand style breakup, a divorce that ended quite well for investors.

Exhibit 8: New Zealand Telecom’s Split Experience

Vivendi has been a Special Situations machine since our Bolloré holding took control. The group is preparing to carve out a portion of Universal Music Group (see our notes from our meeting with the CEO last week) and is backing the TI split. We would be surprised if one day, Bolloré doesn’t eventually split itself in two.

Lastly, and quite surprisingly to the market, Rolls-Royce announced it was pursuing a sale or split of its marine division a couple months ago. While there are zero synergies between aerospace and marine engines, we are surprised by this timing. We would prefer the group to follow FCA’s lead and only split the division when results are accelerating.

Certainly not to come last, we are working with our largest position, which remains confidential, to accelerate the build out of its key growth business. Not only will be backstopping a public offering of its capital-intensive growth business, so that it can access cheaper capital, but we are encouraging the company to ignore short-term margin expansion and reinvest profits back into longer-term growth.

By doing so, we hope and trust, we will fall on the right side of the history of splits.

Steven’s article originally posted here. I highly recommend subscribing!

https://www.gwinvestors.com/blog/

0 notes

Text

Panic! At the Disco

“I chime in with a

"Haven't you people ever heard of closing a goddamn door?!"

No, it's much better to face these kinds of things

With a sense of poise and rationality.

I chime in,

"Haven't you people ever heard of closing a goddamn door?!"

No, it's much better to face these kinds of things

With a sense of...” -Panic! At the Disco

This band was a little early in their political discourse (this song is from 2005), but it rings true in the current environment.

I have no doubt that there was waffling and waning on courses of action played out in previous administrations, but now it’s just political theatre for all to see. The sausage is being made in front of us.

Markets are paying attention. Markets are rational, in the long run, but speculative sentiment is for the “here and now”. It dominates the short term.

I have no idea what direction market the will move next week, next month, or this year—except that it will go up on some days and down on others. But, I do know that markets dislike uncertainty.

Uncertainty is distinct from risk. Risk is quantifiable and manageable; uncertainty is not.

It’s the tail event of a trade war, or of hundreds of billions coming out of share repurchase activity. It’s the heavy foot of the Fed pressing on the gas way too late in the economic cycle. It’s the specter of global elimination of term limits (see Russia and China), and perpetual rulers. Does anyone not believe President Trump would seek a third term after watching on as his “peers” Putin and Xi establish permanent rule with relative ease?

I would argue that each of these events are distinct and independent events. There is no distribution with which to quantify them all.

Mathematically, the variance of independent events (in my opinion, a definition of uncertainty) is additive when combined together.

This suggests that layering in the wide variance within which any of these independent events may occur should increase market volatility substantially.

Practitioners are much more used to correlated events, where diversification can be useful in mitigating quantifiable risk.

For me, this isn’t a signal to sell and run. It too shall pass. I worry more that people will panic and hit the sell button at the bottom and then miss the recovery.

I do believe markets will be more volatile going forward. Making money has been too easy since 2009. It’s about to get harder.

“No, it’s much better to face these kinds of things

With a sense of poise and rationality again...”

1 note

·

View note

Text

What’s Cheap? A Factor Perspective

There are a hundred ways to evaluate whether an investment is cheap--discounted cash flows, competitor multiples, mean reversion, multiple of projected earnings--the list goes on...and on. To each his own on what is the "best" valuation methodology, but suffice it to say that the persistent tug of our own behavioral biases suggests that objective measures (as opposed to subjective) are preferable.