Text

Fox Vs. The Elephant Man

One of the most frustrating elements of David Lynch’s visual aesthetic is his reliance on (often gross) visual shorthand for his characters. Usually, beautiful people are either beautiful to signify goodness or purity, or they are beautiful as a means of highlighting the gap between their assumed goodness and purity and their debauched, dark, or otherwise sordid insides. Much of Twin Peaks is predicated on a somewhat insulting question - how could a beautiful, innocent girl like Laura Palmer come to such a horrific end? Eventually, this question is resolved, explored, and changed into many much more powerful questions, but the visual language of the series’ cast is very intentionally loaded in ways that are both powerful and unfortunate (for a powerful example, look to the clean-cut, professional exterior of Dale Cooper and the lovable, spiritual inside, for an unfortunate example look at the myriad awful ways that Audrey gets utilized).

My first viewing of The Elephant Man was refreshing and surprising because it attempts to subvert societal prejudices about disability and deformity. This is Lynch’s second feature and a notable move away from the internality of most ‘good’ Lynch films. The Elephant Man is a collaboration with other writers (Christopher De Vore and co) and reality, or at least, 19th-century records of reality. It is an adaptation of two books, Frederick Treve’s 1923 book The Elephant Man and Other Rememberances and The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity by Ashley Montagu. Lynch (mostly) steps outside of his typical surrealistic mode to deliver a straightforward period piece / biopic about Joseph Merrick (changed to John Merrick in the film) a severely deformed twenty-two year old London man in the nineteenth century who is discovered by the surgeon Frederick Treves and becomes the talk of London high-society.

The most easily identified ‘classic Lynch’ aspect of the film are the opening and closing impressionistic dream sequences. The opening scene is a stylized take on whatever befell John Merrick’s mother whether his severe deformations were really the result of elephant trampling or not. It opens with a photograph of a woman (John’s mother), which then dissolves into a seemingly unframed photograph, which then dissolves into a small herd of out-of-focus elephants knocking down and attacking an actress who seems to be a composite of the two photographs of Merrick’s mother. This sequence contains terrifying distorted sounds of screaming and elephant trumpeting and faux-stop motion images of a woman writhing in pain. The sequence concludes with white smoke and the crying of an infant. The metaphors on display here aren’t exactly elaborate, but they do give a hint into the pathos of Merrick, as I believe we are meant to see them as originating from his mind.

The second dream sequence is very explicitly also from Merrick’s mind, and bookends the film. Frankly, I have very little to say about it. It’s comforting, I assume it exists to give a sense of closure and peace for Merrick who dies young in bed, but there just isn’t that much in it to really latch onto.

This write up will not be a scene-by-scene of the plot. I want to speak, instead, about a few of the stylistic and thematic elements of the film that I thought were interesting and worth expounding on.

The most important interior in this film are the corridors and chambers of the East London hospital. When Merrick is first brought to the hospital, Lynch uses the techniques of horror films to give insight into perspective of the normal characters, the hospital staff. The ‘monster’ is jostled into the hospital with a bag over his head. Every head in the room is turned to him immediately and you can imagine them imagining what this man looks like that he should be brought in in a large coat and with a bag over his head. There is a lot of powerful imagery in the first half of the film: high-angle shots of nurses walking tensely down long hallways, long trips up flights of stairs, etc. A nurse walks in on a half-naked Merrick, there is an extremely typical jump cut to her screaming face, straight out of Hitchcockian horror, a la Psycho. This seems to be used to evoke the visceral ‘feeling’ that these women have towards the disfigured and strange Merrick. It’s a horror film intentionally drained of all danger. Their reactions are very pointedly unwarranted – Merrick is not a threat, the man can barely walk and has to sleep sitting up to avoid suffocating. The fear, as with most fear of the other, comes more from the hangups of their culture than the reality of the situation. As the hospital staff comes to know and understand the common humanity that Merrick shares, the visual language of the interior of the hospital becomes much more conventional. Merrick is transported from a drab, clinical room to a cozy, homely apartment.

Another interesting aspect of the film is the reactions to Merrick from the differing social classes. A somewhat underbaked question that the film presents is: does high society actually harbor the same sensibilities and biases, as the unwashed masses? Is the façade of social class simply the differences in expressing the same things? John Merrick is made an exhibit multiple times throughout the film. In the beginning, he is a fixture of a traveling freak show where he is treated as an invalid and exploited by a modern-day slave owner who parades Merrick around, exploits his misfortune, and pretends they are in a mutually beneficial partnership. After all, if Merrick cannot work – what other option is there than ritual debasement and abuse? The second form of exhibitionism is perpetrated by Dr. Treves, who uses Merrick’s deformed body to make a name for himself in London’s anatomical society. There is a scene where Merrick is displayed naked to the audience of doctors that is eerily reminiscent of the circus freak show – he is treated as a pitiful mass of flesh to be gawked at but not to be understood. Treves clinical exhibition is certainly his most unsympathetic moment in the film. He will eventually reckon with the similarities between the anatomical society and the freak-show slaver, and his efforts to give Merrick a comfortable, noble life certainly end up redeeming Treves. The third form of exhibitionism is perpetrated by London high-society socialites who install Merrick as a fashionable dinner guest. These men and women are mostly uninterested in the life or perspective of Merrick and they seem to fear his appearance as much as the impoverished freak show attendees do. There are only a few visitors who dash these expectations, and they are certainly the heroes of the film. The fourth form of exhibitionism is perpetrated by a night watch guard using John Merrick as an attraction for his crowd of seedy, deviant friends. I almost read this as a commentary on the inherent exhibitionism of freakshow horror films in general, or the zeitgeist of the counterculture who goes to see Rocky Horror or Eraserhead at drive-ins at midnight. To look forward for a moment, I could certainly imagine Dennis Hopper’s band of deviants paying Merrick a drunken visit if Blue Velvet were in The Elephant Man’s universe. These scenes are deeply unsettling: he is abused, spun around, and made an object of mockery and exoticist derision. However, it is also the most honest form of abuse. No bones are made about the point of these excursions. There is no feigned interest in his unusual anatomy from a scientific standpoint; no one (like the circus owner in the freakshow) considers there to be any form of mutual benefit. There is no rhetoric of ‘partnership’ between the security guard and Merrick. It is pure, straightforward profiteering and abuse.. Another fourth form is Merrick’s role in London high society.

The reason I consider the preceding theme to be somewhat undercooked is how little water it holds. While you can, certainly, notice the parallels between tea and biscuits and a traveling circus, it is obvious which one is preferable to Merrick. In one, he is abused, gawked at, and cheated. In the other, he gets to keep the company of the most exclusive Londoners, pursue his artistic ambitions, and experience art and culture – all at the cost of a few trendy tea parties.

It has also been mentioned to me, and I should point out, that this film almost certainly contains some of the best ‘naturalistic’ performances in Lynch’s career. Now, before I get into this, I should explain what I mean. Last week, I wrote about Lynch’s unique perspective on the medium of film and his intuitive understanding of the artifice: we are watching a dream projected onto a two-dimensional canvas. This perspective extends into the performances he gets from his actors. Since the mid-1950s, and especially since the 1970s, big-budget American filmmaking has been very explicitly linked to naturalistic acting. Most of the time, American directors are trying to get performances that feel real, or at least internally consistent, and there are plenty of incredible examples of this: Orson Welles in Citizen Kane, Al Pacino in The Godfather, Elizabeth Taylor in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Daniel Day-Lewis in There Will Be Blood etc. These performances are about the creation, sustaining, and dramatic deviation from a ‘center’, a realistic voice and perspective. David Lynch is not, in my opinion, a great ‘naturalistic’ character writer or director. That simply isn’t his usual focus, though the emotions he does wish to conjure are real and powerful. He will often take actors to cheesy or unconvincing places (think of the glassy eyed women of Blue Velvet or Patricia Arquette in Lost Highway) in service of a broader point or narrative aesthetic.

The Elephant Man feels notable for both being a good David Lynch film and featuring naturalistic, centralized characters.Anthony Hopkins is, by virtue of being Anthony Hopkins in a well-made film, fabulous. The character of Frederick Treves is absurdly well defined for how little we tangibly learn about him. You can watch the film and see his reservation, his deep self-awareness and sense of morality, his goodness, and his conflict. However, the real runaway of the film is certainly John Hurt as John Merrick. Despite the fact that he is an insane prosthetic getup the whole time (or because of it?) he is able to give Merrick depth and pathos. The first third of the film is spent with Merrick in silence. Joseph Treves believes that Merrick can mostly only vocalize as a parrot, and when it is revealed that Merrick has his own mind and knows how to express it – it’s just beautiful. One of my favorite aspects of this film is just to watch John Hurt walk. So much physical pain and exhaustion is in every step. It’s a beautiful, thoughtful performance.

To wrap this film up, I want to get a little more personal. I have Moebius Syndrome, a neurological condition that is most visibly present in my face. My face is mostly paralyzed. I can’t smile, my speech (though much better than it was as a kid) is always going to be hard for some people to understand, my eyes don’t really close in the traditional sense, I have virtually no lateral eye movement, etc. As a result, I have an eternal poker face that I spoil by also being uncontrollably expressive with my body. I find it reassuring that Lynch, who is often kind of gross to me with how he uses deformity and disability as a shorthand for deviousness or immorality, made a film where we are supposed to cheer for and believe in the ‘monster’. The most accurate part of the film, to my experience as a disabled person, was John Merrick’s socialization process by Treves and the hospital staff, and the natural downsides he still has with communication. Something that people who cannot express themselves ‘normally’ can’t understand is how much of their internality they can make external unconsciously. Without concerted effort, I cannot present the full spectrum of my thoughts with my face, or even the surface level ones like happiness or anger, and so what exists inside of me is able to simply stay there, if I don’t act on it. There is a sort of solace and superpower to being able to choose what you will show, and I love that we always have a sense that Merrick has a deeper internality than he lets on. There are a few examples, like knowing the 23rd Psalm, recognizing his impending death, and his attempts to explain to others his feelings. I love that there is a film that tries to take seriously the experience of forced internality. I also love that this film believes in the goodness of the helpers, the people who know there is value inside of every person and who work to bring it out.

Next week, we meet Kyle MacLachlan for the first time in this series – IN SPACE! That’s right, it’s nearing time to take on David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation of Dune, the 1965 Frank Herbert novel.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fox Vs. Eraserhead

“What’s the strangest thing anyone has ever said to you about Eraserhead?

I like to have people be able to form their own opinion as to what it means and have their own ideas about things. But at the same time, no one, to my knowledge, has ever seen the film the way I see it. The interpretation of what it’s all about has never been my interpretation.”

From Vulture.com’s interview with David Lynch, September 2014.

There you have it. If you are searching for a ‘correct’ interpretation or analysis of David Lynch’s 1977 debut Eraserhead, you have come to the wrong place. Every place you could conceivably go is also wrong because, according to Lynch, no one has ever read Eraserhead like he does. In this write up, and in all the write ups to come, I do not ever want to claim I have gotten anywhere close to the ‘correct’ interpretations. However, I do want to write about the images Lynch presents, and where they lead me.

Image is the perfect jumping-off point to discuss this film. David Lynch’s formal training as a visual artist at the Pennsylvania Academy of Visual Art is oft-cited as a means of contextualizing the focus of his filmmaking. Eraserhead is ground-zero for David Lynch the painter creating David Lynch the filmmaker. The first thing I always notice when I watch Eraserhead is how consciously composed every frame of the film is. To the extent that this film has any clear precedent in filmmaking, it is reminiscent of very early impressionistic and experimental films of the early twentieth century. However, where those films necessarily lack a degree of self-consciousness or experience, Eraserhead uses the canvas of black and white film expertly. The film is deep and rich and grungy. Lynch’s keen interest in two-dimensional projection as his canvas always shines through. Frankly, Eraserhead can be enjoyed simply as an exercise in careful, beautiful framing and cinematography.

However, most people (including yours truly) do not go to the movies simply to marvel at the visual ingenuity of directors. That era of filmmaking and viewing died long before we, or even Lynch, were alive. We want to see images on the big screen that, in some way, speak to us about our own lives. Eraserhead on its’ face may confound that demand. It’s mysterious, and weird, and single-minded in a direction that we aren’t privy to. In my viewing of Eraserhead I’ve isolated quite a few interesting themes worth tugging on and stretching on which will make up the focus of this write-up.

Eraserhead’s life begins at ejection. Specifically, the oral ejection of a horrific sperm-worm piloted by a barnacled man inside of a planet. This film is steeped in bodily violation. Henry’s nightmare gives a crash-course in the sort of horror Eraserhead specializes in. It is reminiscent of HR Giger’s work in Alien, but is even bulkier and more unreal.. Many of the creature effects in this film are either physical puppets or stop-motion animated. Escaping Henry’s dreams into the ‘real world’ (more on that later) gives us an understanding of the environment that produces these nightmares.

I often end up viewing Eraserhead as being about adolescence, and the ways that children have to try on the clothes of adulthood in preparation for the real thing. The sequence of Henry walking home with his sack of nondescript groceries provide tons of fodder for this interpretation. It’s worth re-watching this scene as if it were film of a child making their way home from school in typical suburbia. We can observe the common obstacles like mounds of dirt and thick mud; it’s not a stretch to imagine the sack as reminiscent of a backpack or a lunch sack. Another point for this interpretation is his ritual of checking the mail cubby. I can almost imagine Henry’s dejection every time he gets no mail. Henry’s extreme vulnerability is central to all of his scenes outside of his apartment. The world dwarfs him, it is cruel and industrial and uncaring, he has to establish a single route home just to exert some sense of stability and control (as evidenced by his very deliberate mound traversal). This manufactured comfort will be contrasted during his awkward visit to Mary X’s house.

Viewing Henry as somehow adolescent or childish, we can see many references to common childhood emotions in the film. Walking down his apartment hallway, he is stopped by his enticing neighbor (Judith Anna Roberts). Henry is obviously intimidated and confused by his own intimidation in the face of a confident adul, and he escapes the conversation with as few words as possible. This disparity or outclassing between Henry and the world of adults is another thread I’ve found particularly interesting.

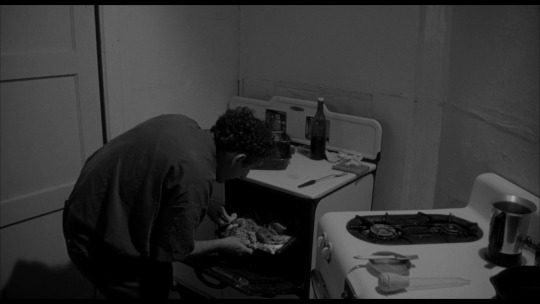

It’s worth making a note about the physical design of the lived-in spaces of this world. The most important space in the film is Henry’s apartment, and it’s incredibly dour and depressing. His attempts at sprucing up the place with plants go as far as piles of dirt with twigs stuck in them. He has virtually no real belongings. And the sound. Like most spaces in this world it is permeated by a constant vaguely industrial whirl and drone. To cover it up, Henry plays a record of atonal carnival music, but that only makes the aural assault even more troubling. An underlying aspect of Eraserhead is the results of industry on society. The rooms we see feel absolutely barren and devoid of what we would recognize as the human element. How do people get used to this? Is that a normal function of becoming a fully-realized human?

Eraserhead is often interpreted as a film about the fear of fatherhood. I see a lot of merit in this analysis. Henry is invited to dinner at the home of his on-again off-again girlfriend, Mary X (though, tellingly, this invitation is conveyed by someone much smokier and more seductive). His trek to her house is about as perilous as his walk home from the grocery store: the streets are now dark and muddled, exposed piping belches steam, dogs yelp in the distance, vines and semi-trees are growing up the exterior of the X household.

Before we get to the meat of the dinner scene (no pun intended), let’s circle back around to the notion of dreams. As I mentioned before, Lynch takes a peculiar approach to the canvas of cinema. The observation is often made that film is essentially a mass hallucination or dream, yet, many mainstream filmmakers want to avoid the reality of how film is consumed as much as possible. The goal of set and sound design, acting, editing, and visual effects in many ‘standard’ films is to convince viewers that they are experiencing a version of reality, as opposed to watching a series of moving pictures projected on a screen. We will come to some examples later in Lynch’s canon where he plays with the idea of verisimilitude and what it means to trick an audience into believing in the unreal, but you have to remember that Lynch is always aware of the façade and is often either counting on you to forget or remember it. It is seductive to imagine Eraserhead as operating on two separate layers of reality; Henry’s dreamscapes and the dreamscapes presented as Henry’s reality (ostensibly). However, do not feel restrained by this delineation at all. This is a free-for-all, and you are always watching a dream.

The whole dinner scene (including the lengthy preamble) is wonderful and confounding. This could be its’ own essay, where we dissect (pun intended?) the dense relationships and symbolism on display. However, since this write-up isn’t meant to be a play-by-play, I’ll stick to my two favorite elements: man-made chickens, and Henry and Mary’s sex life.

The chickens are a fascinating piece of symbolism, in part because they may be the only time a character seems to note, out loud, the odd state of their world (with the possible exception of Bill on the subject of plumbing – people think pipes grow in their houses). The chickens are very explicitly stated to be the result of human genetic muddling. Bill believes them to be just like regular chickens, but once one starts writhing and bleeding on the plate, we are forced to either wonder about what chickens are like in this universe, or consider that perhaps we are not dealing with people who are fully there. There are so many things you can take from the chicken-carving scene and analyze, but I’m going to stick with the physical act. Carving a bird at a family gathering is a classic signifier of masculinity and adulthood in Western culture, hell, James Joyce wrote about it in The Dead. However, in Eraserhead, this mode of human existence, like music and agriculture, is also perverted and horrifying. It is drained of all it’s commonness and played fully for horror.

Is becoming an adult an exercise in desensitization? Is becoming a man, specifically? This dinner scene raises that question. We’ll get back to it. After the aborted dinner, the real point of this whole play comes out – “Did you and Mary have sexual intercourse?”

This entire evening, Henry has had to try on the clothes of adulthood. He’s been asked about his vocation (he’s on vacation, a very adolescent dodge that Mary’s mother does not waste time accommodating), he’s been asked to carve the chicken, and after dinner he is asked directly if he has been having sex with Mary. Henry cannot answer this forward question, just as he can’t handle the smoky siren next door. He might be having sex, but he is not even close to being in a place where he can understand it, or speak about it. In fact, as we have seen, his nights are haunted by immensely sexual imagery. Henry’s attempts at adulthood have been markedly unsuccessful so far, but he doesn’t have much time to get with the program – there’s a baby, and even in Eraserhead babies need fathers.

At this moment, I’m going to follow the somewhat obtuse structure of Eraserhead, and let myself off the hook for annotating every scene, and get into some broader discussions of the themes I’ve detected in the film.

Fatherhood

Henry and Mary’s new infant is not human, even granting that sometimes babies are hardly human. It is small and reptillian. It rejects food, and very quickly contracts sores reminiscent of the barnacles on the face of the man in the planet from the beginning of the film. In a sense, this is the most hyper-charged way of talking about an issue that is common but not very popular: what if you have a responsibility to a baby that you did not want and cannot bond with?

Henry and Mary are neglectful parents to their quasi-baby. Mary ghosts Henry within days. Henry is not perturbed by the incessant crying of the creature, but it drives Mary crazy. This is a playful use and inversion of the instant perfect mom. Mary’s motherly instincts have not kicked in, she isn’t upset that the creature is crying because crying indicates some distress, she’s upset because it is annoying and robs her of her sleep. She does seem to try her best for a short time, but she’s paired with a man-child (a scene I’d like to draw attention to is when he arrives home on what seems to be the first day and lays lengthwise across the bed. It’s classically adolescent.) But within a night, she is gone, not to be seen in the *real* world again.

Henry also doesn’t find much in fatherhood to latch onto. When the baby becomes sick, he gets a radiator for it, but his concern is mostly centered on the fact that it would look bad if the infant died or got sick under his care, especially after an argument with his wife. Henry cannot accept his responsibility, in part because he cannot actually imagine this creature as having any meaningful relation to him, or even to the concept of a real child. The woman in the radiator suggestively points to filicide as a real option for Henry as she stomps on sperm worms. He further abdicates responsibility in the related dream where he pulls worms out of his wife, seemingly shifting the blame away from Henry’s troublesome sperm.

The real moment of Henry’s undoing comes with his affair with the woman next door. In an unbelievably intense scene, Henry is immediately seduced and (in a sense) liberated. Finally, we see Henry as a sexual entity, as he tries (in an outrageously symbolic manner) to keep his monstrous baby silent (though, in a telling moment that points to this being a dream of another sort, his neighbor apparently cannot retain focus on the infant for too long in the heat of Henry’s newfound prowess).

Henry’s lengthy post-coital dreams take him on a whirlwind psychic tour. He encounters the lady in the radiator again, is decapitated, his head is replaced with a leering sperm worm, and so on. There’s a lot to read into all of this. Henry’s head’s new use as an apparatus of his industrial world, the old man lying in the dusty street feebly watching a child collecting his head. All of it is dense and mystical and deserves another adjoining essay, which I haven’t written. Were these dreams about heaven, hell, suicide, guilt? I don’t have the answers, and again, I find the questions themselves more interesting.\

Is Adulthood Just Desensitization?

I briefly mentioned the sound design in Henry’s apartment, and I feel guilty that I don’t have the expertise on audio production to give this element of the film the gravity it deserves. Sound is so important to Eraserhead. The mixture of foley work and the otherworldly (though not entirely unfamiliar) industrial droning is iconic. Desensitization or failure to desensitize to sound is an important element of Eraserhead.. Henry has to put on a faded record to try and escape the constant drone of his apartment. Mary X cannot deal with the sonic stress of her crying creature/baby. Henry has to gag the creature to not alert his neighbor to its’ presence. The proliferation of unpleasant sound in this world is fundemental to its’ construction, and it seems like a big part of existing in the world of Eraserhead is simply dealing with intrusive sound.

Another aspect of desensitization in this film is Henry’s apparent sexual awakening. I’ve struggled a little in my interpretation of what the film is trying to say about sexual maturity. Henry, despite the construction of the story and the fact that he got a woman pregnant, has an extremely virginal outlook at the start of the film. Remember back to how he describes his outings with Mary X “why don’t you come around anymore?” and his dodginess when faced with Mary’s mother and her frank questioning. Henry seems marginally more comfortable in making sexual advances by the end of the film, but it also seems to be a wellspring of guilt and fear for him. His desires, rather than being healthily realized either by Mary X or his neighbor, instead seem to be made manifest as a terrifying, spermic creature.

New watchers of David Lynch should get ready for lots of confusing depictions of sex and gender in general. Lynch can don the clothes of a turn of the century white American man or a bohemian, depending on what sort of imagery he chooses to create. I think it’s more helpful to simply ask the question - what is Eraserhead saying about Henry’s growing knowledge and desire for sex?

A third type of desensitization present in Eraserhead is related to the lived-in environment. I touched on before how unflattering and unkempt Henry’s apartment is, but we should also retain sight of the fact that, well, David Lynch is working with late mid-century Philadelphia as his canvas. He seems to delight in the factory town in a way that I cannot fully understand, but if you read interviews with him about Eraserhead, he states that he loves the universe they created for the film and would live in it if he could. He’s an industrialist. But it’s also clear that these characters are not made whole by their environment. No one seems worried that all their plants die, and that all their music is atonal and garish This desensitization to an abjectly gross living situation isn’t an active process in the film- Henry never seems to be that upset by the shabbiness of his apartment, the concrete caverns of his apartment building, or the dead factories of his city. But we, as viewers, not accustomed to it, do have to take note of the circumstances, and eventually we come to internalize them as well. People are moulded by their environment, and Eraserhead wants to see what shapes they can take.

Adolescence

To wrap up my analysis, I want to think a little bit about the ending of the film. I come to it with a simple question: what direction is Henry going?

I’ve made previous mention to many instances of Henry’s evident childishness and naivete, but I perhaps haven’t been explicit enough.

I consider Henry’s sexual encounter with his neighbor to be almost purely adolescent fantasy (which isn’t to make a statement on it’s level of truth in the layered structure of this film, it seems to reside on the same layer as any other concrete event in the film, which is to say, it’s one layer down from planet man, and half a layer down from Henry’s head being used to make erasers, but also my layered structure is also completely just my own invented heuristic). My statements on the levels of narrative in this film are almost certainly undercooked, but I don’t necessarily think that we are meant to ever get any further than we want to on the question of what is real).

Adolescent impressions of sexuality are often eclipsed by real experiences later on, but in this scene the moments feel very raw and expectant. They are the impressions sustained by a preceding lifetime of unexperience. Every word in this scene hangs heavy. It’s incredible straight male wish fulfillment, and an intensely frank depiction of what children imagine sex to be: enticing and cosmically terrifying. What are we to see in this encounter? It seems like it is a source, or reincarnation, of guilt that Henry has created in the past and cannot escape, an interpretation that is bolstered by the violent imagery that follows as a consequence, and the fact that the two characters literally sink into a pool of goo.

Also, as a forward-looking note, this is not the last time Lynch creates impossible sexual encounters that feel positively inescapable. It’s one of the things that really draws me to his work.

But does all this - change Henry? Does it change us? What, by observing his dreams, are we meant to understand about him? I have impressions, but they are not concrete enough to try and write out. I consider the last twenty-five-ish minutes of Eraserhead to be a true litmus test. How they make you feel, what worlds they conjure and what possibilities are included and excluded in them is entirely personal. Frankly, writing about Eraserhead is somewhat quixotic because the film succeeds in a realm beyond words. There’s a reason telling someone else about your dream is so boring, after all.

So there we go! That’s the first post in my series. I cannot believe I’m going to write one of these every week for the next few months, but it’s immensely exciting and a new type of challenge. If you don’t like my take, or if you have your own, comment it. If you like this project and are excited for more, I’d really appreciate you subscribing or sharing this post!

Next week: The Elephant Man!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What the hell did I just watch?” Introducing Fox Vs. Lynch

(source: http://www.rollingstone.com/tv/news/see-david-lynch-eat-doughnut-in-new-twin-peaks-tease-w456657)

David Lynch is one of the most revered living American directors. His films are dense, beautiful, expressive, horrifying, and always one of a kind. However, his films also have a parallel reputation of being weird-for-weirdness sake, self-indulgent, and cold. Almost every Lynch film is divisive, even (or especially) for self-proclaimed Lynch fans.

Discovering David Lynch’s films (first through Twin Peaks) was a major stepping stone in my appreciation for and understanding of film as a medium. To be frank, his work got me from barely being able to focus on a film outside of a theater to being a major film fan. He demanded my attention, and he rewarded it almost every outing.

I had a list of writing projects I’ve been putting off for a long time, and no. 1 on my list has been a personal challenge: I want to watch and write about every David Lynch feature film. Here’s the list, for reference:

Eraserhead

The Elephant Man

Dune

Blue Velvet

Wild At Heart

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

Lost Highway

The Straight Story

Mulholland Drive

Inland Empire

Not only do I want to watch and critically consider these films, I want to do it from a different perspective than much of the Lynch discussion I see. Namely, I have come to believe that every Lynch film, underneath it’s abstract and surrealist mysteries, is about intimately documenting trauma, alienation, and guilt. I want to write about Lynch’s films on what some may consider the most surface level - the emotional lives Lynch depicts. We will talk symbolism, we will talk head-scratching non-sequiturs, we will talk intricate sound design and cinematography, but we will not stop at “huh, what an interesting choice”. I want to go as deep as I can into the assumption that Lynch is challenging us to watch his films and see what their mysteries have to do with every day life.

I plan to take a lightly metatextual look at his filmography. I have conducted thought experiments to imagine how I might perceive any of his films individually, without ever knowing that the man behind the camera was named David Lynch and he has been creating films for decades but I cannot, for better or for worse, extract any individual Lynch film from his broader canon.T This seems to be a uniquely challenging issue for directors, though it’s obviously also a large argument in the criticism community and has been for decades. I will not hesitate from mentioning past or future films for this reason, though when I do I will make sure to highlight it. Also, I will not refrain from viewing interviews or personal statements by Lynch, but I also know Lynch is typically not interested in giving you ‘his’ take on the film, as he is necessarily an unreliable narrator, so his own comments probably won’t be of much use.

I hope readers will join me on this journey. I think it will be a lot of fun to revisit his films, and watch the ones I have not seen yet for the first time (full disclosure: I have not seen a handful of them, and I will make sure to note it when I get to each film). David Lynch is a director worth watching, and re-watching, and re-re-watching.

Schedule

Because this is a passion project, and because it is meant to fill in a void of activity over the summer, I want to keep a rigid schedule. I plan to have a post up on the blog every Sunday, starting on June 3rd, where I will be re-watching and re-considering the plight of Henry (Jack Nance) in the cult classic Eraserhead.

Notes on Handling Twin Peaks

I’ve given some thought to how I will handle bridging Wild At Heart to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, because it is not my intention to rewatch every episode of Twin Peaks. I imagine most Lynch fans are already familiar with Twin Peaks but I also don’t want to cast away anyone who isn’t interested in watching the entire series, plus the eighteen part new season airing this summer. If you have any suggestions, feel free to comment or tweet to me @Gamebeast23456 (I know).

I’m excited to get started!

0 notes