They/them | 24 | nostalgic new graduateA blog to collect my thoughts and discoveries as I reread the books from my French Revolution history class’s syllabus (and more!). My main is @fantasiavii

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

My Writings and Contributions

Translations of Frev Sources

Media and books influenced by Thermidorian propaganda

Here are some facts we take for granted that revolutionaries didn't know that will blow your mind

Learning to Be a Lawyer in 18thc France

Brief historiography on women, the law, marriage and divorce (scroll down)

Brief overview of the Thermidorian Reaction

On Saint-Just's Personality: An Introduction

Saint-Just in Five (Long) Sentences

Random Sources and References on Saint-Just's Youth (In French)

Louise Michel's Poem on Saint-Just

On Charles Le Bas, Philippe's brother and Élisabeth Duplay's second husband

References on Couthon

Book and article recommendations:

The "short" version

Part 1 - A Note On Objectivity and Two Approaches (introduction) + Culture: Enlightenment and Antiquity

Part 2 - Ideological Stakes

Part 3 - Old Classics and Syntheses

Part 4 - Specific Topics and Areas of Research

Part 5 - Side-related but still important

Part 6 - Highlights and Short Reviews

My Posts In Progress and Eventual Research:

My thoughts and analysis of Saint-Just's unsent letter to Villain d’Aubigny

A (brief?) introduction to Saint-Just’s many faces and myths

Could Saint-Just have been neurodivergent?

Why Enjolras was inspired by Saint-Just: comparing the text of the brick to Saint-Just’s Romantic Myth

An Episode of the Thermidorian Reaction: the Attack on the Club des Jacobins and the Misogynist Targetting of Women

How the pamphlet about the Club infernal locates them in the circle of Wrath and not Treason - the latter would out them as counterrevolutionaries

Can we call the French Revolution a "fandom"? The invention of celebrity culture, etc.

The differences between Thermidorian propaganda and Anglo-American propaganda (and where they overlap)

Other Important Posts

Some primary and secondary sources available online for free (by anotherhumaninthisworld; some additions by myself)

Frev Resources (by iadorepigeons)

Myths and misconceptions about the French Revolution

Anglo American historiography (by saintjustitude and dykespierre)

On the Terror's Death Toll and Donald Greer (by montagnarde1793) More about this topic here and here (by lanterne, anotherhumaninthisworld, frevandrest and radiospierre)

On Robespierre's Black Legend (by rbzpr)

On Thermidorian propaganda (by lanterne)

On Couthon (by iadorepigeons)

Marat Ressource Masterpost (by orpheusmori)

Collaborative Masterpost on Saint-Just (many authors)

Saint-Just Masterpost (by obscurehistoricalinterests)

One myth on Saint-Just (by saintjustitude and frandrest)

Saint-Just as political philosopher and theorist (by saintjustitude)

Élisabeth Lebas corrects Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des Girondins (1847) (by anotherhumaninthisworld)

On Charlotte Robespierre's memoirs (by montagnarde1793 and saintjustitude)

On Simonne Évrard (French and English biography copy-pasted by saintjustitude from the ARBR website)

Regulations for the internal exercises of the College of Louis-le-Grand (by anotherhumaninthisworld)

Were Robespierre and Desmoulins together at Louis-le-Grand? (by robespapier and anotherhumaninthisworld)

Robespierre was not Horace Desmoulins' godfather (by robespapier and anotherhumaninthisworld)

The relationship of Camille Desmoulins and Robespierre in literary works of Przybyszewska (by edgysaintjust)

Last edited: 16/05/2023

Support me!

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exhibition 1793-1794 at the Carnavalet Museum (Part I)

For anyone interested in the French Revolution, a visit to the Carnavalet Museum is essential. Though the museum covers the history of Paris from its very beginnings to the present, it’s also home to the world’s largest collection of revolutionary artefacts. Which makes sense, given that Paris was the epicentre of it all.

Frankly, if you plan to explore it all, you’ll want to set aside a good 3–4 hours. For those focused solely on the French Revolution, head straight to the second floor, where you can get through the collection in under an hour. Best of all, the permanent collection is free, making it a brilliant way to spend an afternoon in the city on a budget.

Currently, though, there’s a special treat on offer. Running from 16 October 2024 to 16 February 2025, the museum is hosting an exhibition dedicated to my favourite (and arguably the most chaotic) year of the revolution: Year II (1).

Now, since the family and I were in Reims for a long weekend, I somehow managed (possibly after too much Champagne) to convince my husband to drive 150 kilometres to Paris just so I could see Robespierre’s unfinished signature. It helped that the kids were on board, too. Yes, the four-year-old fully recognises Robespierre by portrait. The one-year-old is, predictably, indifferent.

So, slightly worse for wear after a ridiculous amount of Champagne tastings, off we went to the museum.

1. Why Year II?

Because it was a catastrophe. No. Really. Let me explain, in a very overly-simplified summary:

In Year II, France was plunged into an unparalleled storm of internal and external crises that would define the Revolution’s most radical year and ultimately mark its turning point.

Internally, the government was riven by factional divides, economic collapse, and civil war. The Jacobins (2) took control of the Convention, sidelining the federalist Girondins (3), aligning themselves with the sans-culottes (4), and arguing that only extreme measures could preserve the Revolution. Meanwhile, the more radical Enragés (5) demanded harsh economic policies to shield the poor from spiralling inflation and food shortages. The Convention introduced the Maximum Général (6) to placate them, which capped essential prices; however, enforcement was haphazard, fuelling discontent across the country. At the same time, the Indulgents (7) called for a reduction in violence and a return to clemency.

Externally, France’s situation was equally dire, encircled by the First Coalition—a formidable alliance of Britain, Austria, Prussia, Spain, and the Dutch Republic, all intent on crushing the Revolution before it spread further. With the execution of Louis XVI, France found itself diplomatically isolated, and the army was, frankly, a shambles. Most officers were either nobles or incompetent (8), and the soldiers were inadequately trained and equipped. In a desperate bid to defend the Republic, the Convention issued the Levée en Masse (9) in August 1793, sparking revolts in many cities and outright civil war in the West.

Confronted with this barrage of existential threats, the Convention dialled up its response in spectacular fashion, unleashing what we now know as the Terror—a period of sweeping repression backed by some rather questionable legislation. As you can likely guess from the name alone, this was a brilliant idea…

Put simply: by the end of Year II, nearly all the key figures who had spearheaded the Revolution up to that point were dead. And no, they didn’t slip away peacefully in their sleep from some ordinary epidemic. They met their end at the guillotine.

In short, Year II wasn’t just the Revolution's most radical and defining phase—it was also the year the Revolution itself died. Yes, the Revolution, in its truest, purest, most uncompromising form, met its end the moment the guillotine's blade struck Robespierre’s neck.

2. Overview of the exhibition

The visit opens with the destruction of the 1791 Constitution and closes with Liberty, an allegorical figure of the Republic depicted as a woman holding the Declaration of the Rights of Man in her right hand. In between, the experience is structured around five main themes:

A New Regime: The Republic

Paris: Revolution in Daily Life

Justice: From Ordinary to Exceptional

Prisons and Execution Sites

Beyond Legends

More than 250 artefacts are featured, including paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, historical items, wallpapers, posters, and furniture. The layout is carefully structured around these themes, with a distinct use of colour to set the tone: the first three sections have a neutral palette, while the final two glow in vivid red, creating a very nice change in atmosphere.

What I appreciated most was how the descriptions handle the messy legacy of Year II. The texts actually admit that, while some Parisians saw this year as a bold step towards equality and utopia, for others it was an absolute nightmare. This balance is refreshing, even if things are a bit simplified (because how could they not be?), and it gives a well-rounded view of a wildly complicated time.

In this first part, I'll focus on the first two sections, as the latter three fit together neatly and deserve a deep dive of their own. Besides, there's so much to unpack that I'll likely exceed Tumblr's word limit (and the patience of anyone reading this).

3. A New Regime: The Republic

The first section covers the shift from the Ancien Régime to the First Republic, and, fittingly, it starts with a smashed relic of the old order: the Constitution of 1791. After the monarchy’s fall and the republic’s proclamation in September 1792, the old constitution was meaningless. Though it technically remained in force for a few months, it was replaced by the Constitution of Year I in 1793, marking the end of France’s brief experiment with a constitutional monarchy. In May 1793, the old document was ceremonially obliterated with the “national sledgehammer”—a bit dramatic, perhaps, but Year II was nothing if not dramatic.

This section zeroes in on the governance of the new republic, featuring the Constitution of Year I, portraits of convention members, objects from the Committee of Public Safety and the National Convention (including a folder for Robespierre’s correspondence), and national holiday memorabilia. There’s even a nice nod to Hérault de Séchelles (10) as a principal author of the republican constitution.

3.1 Martyrdom as a political tool

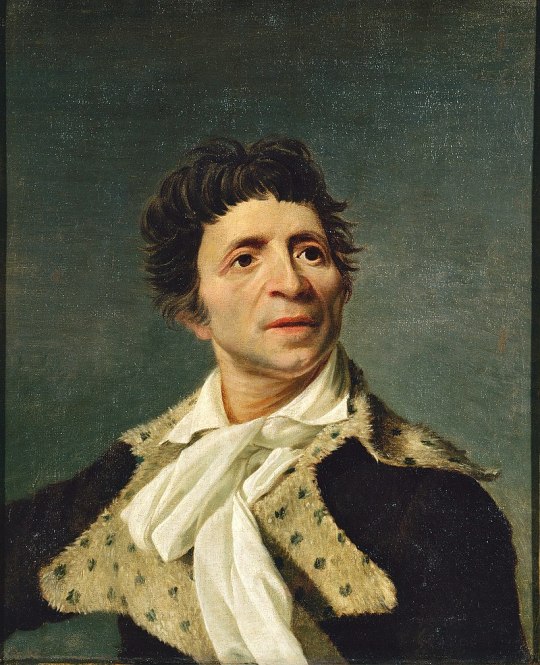

Interestingly, the exhibition places a heavy emphasis on the concept of martyrdom. A significant portion of this first area is dedicated to the Death of Marat (11) and, to a lesser extent, the assassination of Le Peletier (12). It’s a clever angle since martyrs—whether well-known figures or nameless soldiers—have always been handy for rallying public opinion. The revolutionary government of Year II understood this all too well and wielded the concept to its full advantage.

In this spirit, the middle of this section features a reproduction of David’s Death of Marat, several drawings from Marat’s funeral, Marat’s mortuary mask, a supposed piece of his jaw, and more. Notably absent are any issues of L’Ami du Peuple, as though the display suggests Marat’s death was more impactful to the Republic’s narrative than his actual writings. I’d agree with that—the moment he died, he was elevated to a mythic status, and his legacy as a martyr of Year II took on a life of its own.

4. Paris: Revolution in Daily Life

While the first section focuses on the workings of governance, this part delves into Year II’s impact on ordinary Parisians. This period stands out for two reasons: France was in economic and political turmoil (wars, both internal and external, aren’t exactly budget-friendly), yet it also managed to introduce some remarkably forward-thinking legislation aimed at improving the lives of the common people.

4.1 The Paris Commune & Paranoia

To understand life in Paris during Year II, we can’t overlook the role of the Paris Commune (13). Rooted in the revolutionary spirit of the Estates General of 1789 and officially formalised by the law of 19 October 1792, the Commune was the governing body responsible for Paris. Divided into forty-eight sections, each with its own assembly, it gave citizens a strong voice in electing representatives and local officials. Led by a mayor, a general council, and a municipal body, the Commune handled essential civic matters like public works, subsistence, and policing.

From 2 June 1793 to 27 July 1794 (the height of Year II), the Commune implemented the policies of the Montagnard (14) Convention, which aimed to build a social structure grounded in the natural rights of man and citizen, reaffirmed on 24 June 1793. This social programme sought to guarantee basic rights such as subsistence (covering food, lighting, heating, clothing, and shelter), work (including access to tools, raw materials, and goods), assistance (support for children, the elderly, and the sick; rights to housing and healthcare), and education (fostering knowledge and preserving arts and sciences).

All this unfolded in an atmosphere thick with paranoia and intense policing; enemies were believed to lurk everywhere. The display does a solid job of capturing this side of the Paris Commune, featuring various illustrations that urged people to conform to new revolutionary norms—wear the cockade, play your part in the social order, fight for and celebrate the motherland, and so on.

One of my favourite pieces was the record of cartes de sûreté (safety cards) from one of the 48 Parisian sections. Made compulsory for Parisians in April 1793, these cards were meant to confirm that their holders weren’t considered “suspects” in a climate thick with paranoia. This small, seemingly random document—issued or revoked at the discretion of an equally random Revolutionary Committee—had the power to decide a person’s freedom or the lack of it.

At the risk of sounding sentimental, in the study of history, we often focus on broad events and overlook the "little guy" who lived through them. But here, this record reminds us that behind each document was, in fact, a real person. And that this very real person was trying to make their way through a reality that, 230 years ago, must have felt stifling and, at times, terrifying.

4.2 Education

A significant spotlight is rightly placed on education in this exhibition section, given the sweeping changes it underwent during the Revolution.

Before 1789, Paris was well-supplied with educational institutions. Eleven historic colleges and a semi-subsidised university offered prestigious studies in theology, law, medicine, and the arts, drawing students from across France. Inspired by Enlightenment ideals, boarding schools and specialised courses in subjects like science and mathematics had sprung up, mainly catering to the middle class, while working-class children attended charity schools. Private adult education also provided technical and scientific training. The catch? Most of these were church-operated.

Revolutionary policies targeting the Church caused a mass departure of teachers, financial difficulties, and restrictions on hiring unsalaried educators. Military demands, economic turmoil, and protests added to the strain on schools. Even the Sorbonne (15) was shut down in 1792, and by late 1793, nearly all Parisian colleges were closed except for Louis-le-Grand (16), which was renamed École Égalité. With the teacher shortage and soaring inflation, a handful of institutions struggled on.

This left the Convention and the Paris Commune scrambling to find new ways to educate the young, and they rose (or at least attempted to rise) to the occasion. On 19 December 1793, the Bouquier Decree aimed to establish free, secular, and mandatory primary education—a remarkable move, though it never fully materialised due to lack of funding.

With France at war, the Convention turned public education towards the needs of a nation in crisis. Throughout 1793 and 1794, new scientific and technical programmes sprang up to meet urgent demands, combat food shortages, and push social progress. Thousands of students were trained in saltpetre refinement (vital for gunpowder), and scientific knowledge spread beyond chemists to artisans and tin workers. In the final months of Year II, a saltpetre refinement zone was set up, the École de Mars was founded to rapidly train young men in military techniques, and the École Centrale des Travaux Publics (future École Polytechnique) was established to develop engineers in military-technical fields.

The education display features a fascinating array of educational degrees, lists of primary school students, and instructor rosters. Although a bit more context on the educational upheaval would have been helpful, the artefacts themselves are intriguing. Placed in the context of the rest of the exhibit, it’s clear that the new educational system wasn’t just about breaking away from the Ancien Régime; it was also very deliberately and openly crafted to instil republican ideals. Nothing illustrates this better than the way Joseph Barra(17) was promoted as a model for students at the École de Mars.

And, of course, this section also showcases one of the most enduring legacies of the Revolution: the introduction of the metric system and modern standardised measurements.

4.3 The (lack of) Women in Year II

The women of Year II were not real women. They were symbols—or so the imagery from the era would have us believe. There is shockingly little about the actual experiences of women in the collective memory of Year II.

Women played active roles in the Revolution. They filled the Assembly’s tribunes as spectators, mobilised in the sections, founded clubs, joined public debates, signed petitions, and even participated in mixed societies. In many cases, they worked side by side with men to bring about the Republic of Year II. So where are they?

Well, they’re certainly not prominent in this exhibition—but that’s not the fault of the organisers. It’s a reflection of how the time chose to represent them. In revolutionary imagery, women became allegories: symbols of Liberty, wisdom, the Republic, or the ideal mother raising citizens for the state, often reduced to stereotypes and caricatures. Rarely were they depicted as part of the public sphere.

The absence of a serious discourse on women’s rights in this part of the exhibition speaks volumes and is true to the period itself. At the time, there was no cohesive movement for women’s rights, and while specific individuals pushed for aspects of female citizenship, these efforts lacked unity or a common cause. Eventually, being perceived as too radical, all women's clubs were closed in 1973.

4.4 Dechristianisation

In my view, dechristianisation was perhaps the greatest misstep of the various governments from 1789 onwards. Not because I think religion should be central to people’s lives—not at all—but because, in 18th-century France, it simply was essential for most. The reasoning behind this attack on religion was sound enough: no government wants to be beholden to a pope in Rome who had heavily supported the deposed king. But in practice, the application of this principle was far from effective.

By Year II, Parisian authorities were still grappling with the fallout from the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790), which had left Catholics split between two competing churches: the constitutional church, loyal to the Revolution, and the refractory church, loyal to Rome. Patriotic priests suspected refractory priests of using their influence to fuel counter-revolutionary sentiment—a suspicion that only intensified the general atmosphere of paranoia.

As tension mounted, it devolved, as these things often do, into outright destruction. On 23 October 1793, the Commune of Paris ordered the removal of all monuments that "encouraged religious superstitions or reminded the public of past kings." Religious statues were removed, replaced by images of revolutionary martyrs like Le Peletier, Marat, and Chalier (19), in an effort to supplant the cult of saints with the cult of republican heroes.

The exhibition presents this wave of destruction with artefacts from ruined religious statues, the most striking being the head of one of the Kings of Judah from Notre-Dame’s facade. These 28 statues were dragged down and mutilated in a frenzy against royalist symbols in 1793. . Ironically, they weren’t even French kings; they were Old Testament kings, supposedly ancestors of Christ—a fact that most people at the time were probably blissfully unaware of. But hey, destruction in the name of ignorance is nothing new, is it?

Many in the Convention and the Commune were atheists and enthusiastically supported the secularisation of public life. Unfortunately, they didn’t represent the majority of the French population. To bridge this gap, Robespierre proposed a "moral religion" without clergy, a way for citizens to unite and celebrate a shared, secularised liberty. In December 1793, the Convention passed a decree granting "unlimited liberty of worship," leading to the Festival of the Supreme Being, held in Paris and throughout France on 8 June 1794.

As with so much in Year II, the "Supreme Being" affair was a logical solution to a pressing problem that ended up blowing up in Robespierre’s face—by now, you might detect a pattern. But that’s a story for Part II of this already very long post.

5. Conclusion to Part 1

Overall, the exhibition presents the first two themes—A New Regime: The Republic and Paris: Revolution in Daily Life—in a balanced way, which I really appreciate. I was expecting a bit more sensationalism, given that Year II is known for its brutality, but instead, it provides a thoughtful overview of how the Republic was structured and the impact this had on Parisians.

The range of media and text offers a good dive into key points, especially on everyday life during the period. I didn’t listen to everything, but from what I saw, the explanations were well done. Naturally, since the exhibition is aimed at the general public, many aspects are simplified.

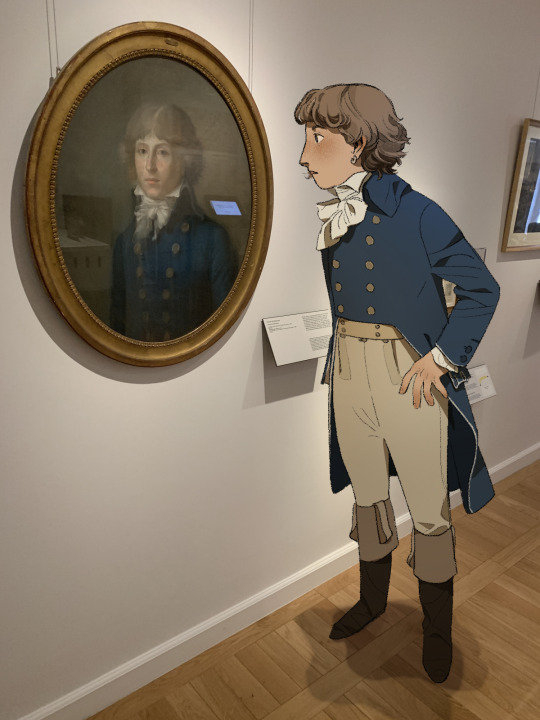

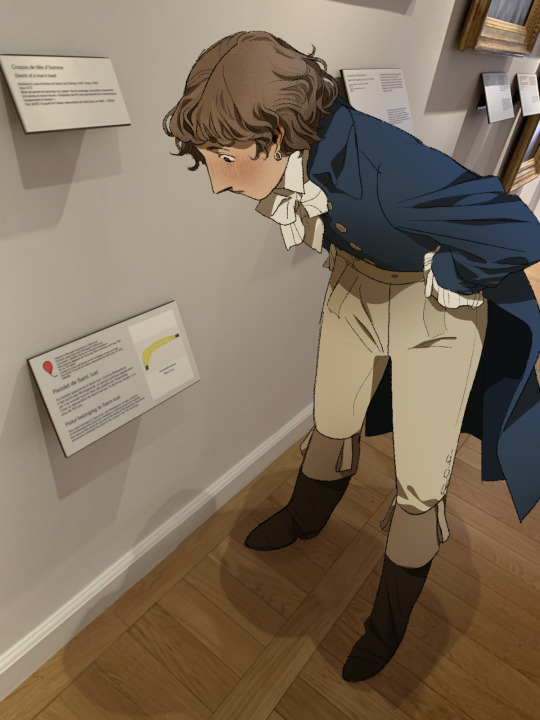

For younger audiences (pre-teens, perhaps?), the exhibit includes 11 watercolour illustrations by Florent Grouazel and Younn Locard. These two artists attempt to fill the gaps by depicting events from the period that lack contemporary representation (like the destruction of the Constitution with the “national sledgehammer” on 5 May 1793—an event documented but unillustrated at the time). For each scene, they created a young character as an actor or observer, sometimes just a witness to history, to make the scene more immersive. It’s a nice touch, though easy to overlook if you’re not paying close attention.

In Part II, I’ll share my thoughts on the remaining themes: Justice, Prisons and Execution Sites, and Beyond Legends. And yes, a lot of that will involve Thermidor—how could it not?

In the meantime, if you made it this far… well, I’m impressed!

Notes

(1) Year II: Refers to the period from 22 September 1793 to 21 September 1794 in the French Revolutionary calendar.

(2) Jacobins: A political group advocating social reform and, by 1793, strongly promoting Republican ideals. Most revolutionaries were, or had once been, members of the Jacobin club, though by Year II, Robespierre stood out as its most prominent figure.

(3) Girondins: A conservative faction within the National Convention, representing provincial interests and, to some extent, supporting constitutional monarchy. Key figures included Brissot and Roland.

(4) Sans-culottes: Working-class Parisians who championed radical changes and economic reforms to support the poor. The name “sans-culottes” (meaning "without knee breeches") symbolised their rejection of aristocratic dress in favour of working-class trousers.

(5) Enragés: An ultra-radical group demanding strict economic controls, such as price caps on essentials, to benefit the poor. Led by figures like Jacques Roux and, to some extent, Jacques Hébert, the Enragés urged the Convention to fully break from the Ancien Régime.

(6) Maximum Général: A 1793 law imposing price caps on essential goods to curb inflation and aid the poor. Though well-intended, it was difficult to enforce and stirred resentment among merchants.

(7) Indulgents: A faction led by Danton and Desmoulins advocating a relaxation of the severe repressive measures introduced in Year II, calling instead for clemency and a return to more moderate governance.

(8) Incompetence: At the Revolution’s outset, military positions were primarily held by nobles. By Year II, these noble officers were often dismissed due to mistrust, and their replacements—particularly in the civil conflict in the West—were frequently inexperienced, and some, quite frankly, incompetent.

(9) Levée en Masse: A mass conscription decree of 1793 requiring all able-bodied, unmarried men aged 18 to 25 to enlist. This unprecedented mobilisation extended to the wider population, with men of other ages filling support roles, women making uniforms and tending to the wounded, and children gathering supplies.

(10) Hérault de Séchelles: A lawyer, politician, and member of the Committee of Public Safety during Year II, known primarily for helping to draft the Constitution of 1793.

(11) Jean-Paul Marat: A radical journalist and politician, fiercely supportive of the sans-culottes and advocating revolutionary violence in his publication L’Ami du Peuple. Assassinated in 1793, he became the Revolution’s most famous martyr.

(12) Louis-Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau: A politician and revolutionary who voted in favour of the king’s execution and was assassinated in 1793 shortly after casting his vote, becoming a symbol of revolutionary sacrifice.

(13) Paris Commune: Not to be confused with the better-known Paris Commune of 1871, this Commune was the governing body of Paris during the Revolution, responsible for administering the city and playing a key role in revolutionary events.

(14) Montagnard Convention: The left-wing faction of the National Convention, dominated by Jacobins, which held power during the Revolution’s most radical phase and implemented the Reign of Terror.

(15) Sorbonne: Founded in the 13th century by Robert de Sorbon as a theological college, the Sorbonne evolved into one of Europe’s most respected centres for higher learning, particularly known for theology, philosophy, and the liberal arts. It was closed during the Revolution due to anti-clerical reforms.

(16) Louis-Le-Grand: A prestigious secondary school in Paris, temporarily renamed École Égalité during the Revolution. Notable alumni include Maximilien Robespierre and Camille Desmoulins.

(17) Joseph Barra: A young soldier killed in 1793 during the War in the Vendée, whose death was used as revolutionary propaganda to inspire loyalty and martyrdom among French youth.

(18) Civil Constitution of the Clergy: A 1790 law that brought the Catholic Church in France under state control, requiring clergy to swear allegiance to the government. This split Catholics between “constitutional” and “refractory” priests, heightening religious tensions.

(19) Joseph Chalier: A revolutionary leader in Lyon who supported radical policies. He was executed in 1793 after attempting to enforce these policies, later becoming a martyr for the revolutionary cause.

245 notes

·

View notes

Photo

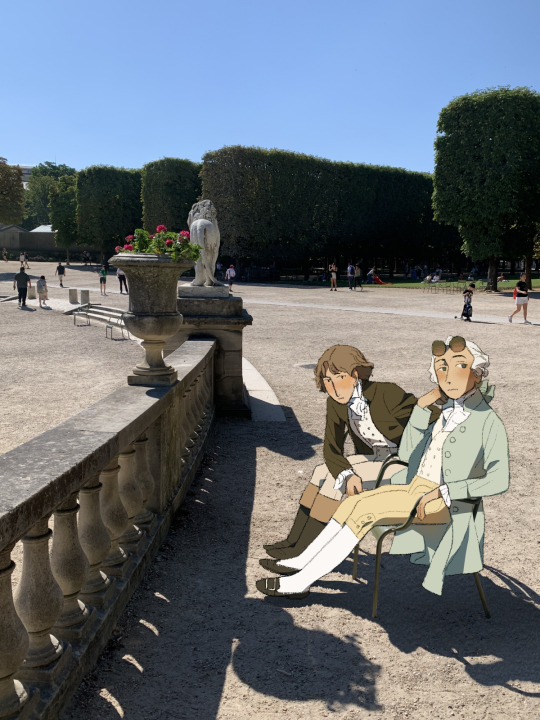

Joyeux 14 juillet ! Look who I found…..

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Marisa Linton really didn’t like the BBC documentary and Hilary Mantel’s portrayal of Saint-Just

The Sea-Green Incorruptible and the Archangel of Death: How narratives of the French Revolution contrast the roles of Robespierre and Saint-Just

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

His was an unearthly beauty. His large deep-blue eyes reflected the firmament of an unknown universe. His fair curly hair fell over his rounded forehead, almost touching his eyebrows, whose delicate arches continued the curve of his nose. His mouth was finely moulded and almost unnaturally pure, as if formed by the spatula of an artist. Whence came the almost delirious charm of this physiognomy? Perhaps from the ability to inspire both tenderness and icy fear. If one felt inclined to lay one’s hand on those golden locks thickly covering the childlike head, one also wished to flee to the end of the world from the enigmatic hardness of that look. Had another mouth ever touched those perfect lips? What did that face look like asleep: were the cheeks flushed, the mouth open? Did he ever sleep? Was he alive? Was he dead?

~ Friedrich Sieburg describing Saint-Just (Robespierre the Incorruptible; full book here).

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

In honor of Marat's birthday I found a complete (?) collection of L'Ami du Peuple ! Happy reading frev pals and happiest of birthdays to Jean-Paul, wherever he may be. In memory of our forever favorite sewer-dwelling doctor, scientist, and revolutionary friend of the people.

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my gosh I can actually share all the frev finding here AAAAAAA

I went to the temporary exhibit Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette & la Révolution at Musée des Archives Nationales and it's really really worth it! Also it's free

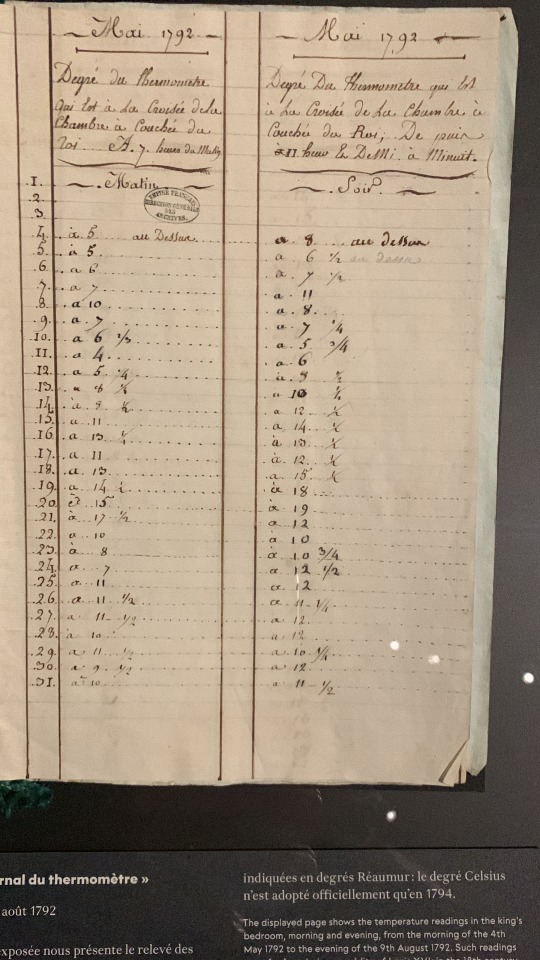

They had recordings of Louis' room temperature in the Tuileries (which is recorded in réaumur unit). The highest temperature record here is 19 reaumur which apparently converts to 23.75 celsius, so damn Louis' room is pretty cold in May lol. (sorry edit: that's highest it ever reaches most of time it's much colder than that hhhh)

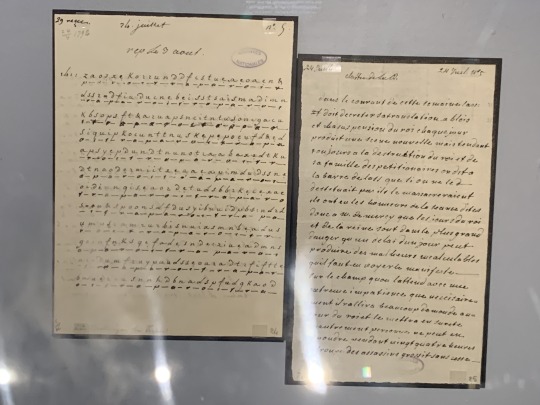

There is also a bunch of exchanges between Antoinette and Fersen that's actually written in cipher! (So yes concrete proof that Antoinette is actively working against the revolution Antoinette stans take that) Sorry the picture is blurry the room is dark

ALSO Robespierre's draft for his speech against the war in the Jacobins!! His writing!!!

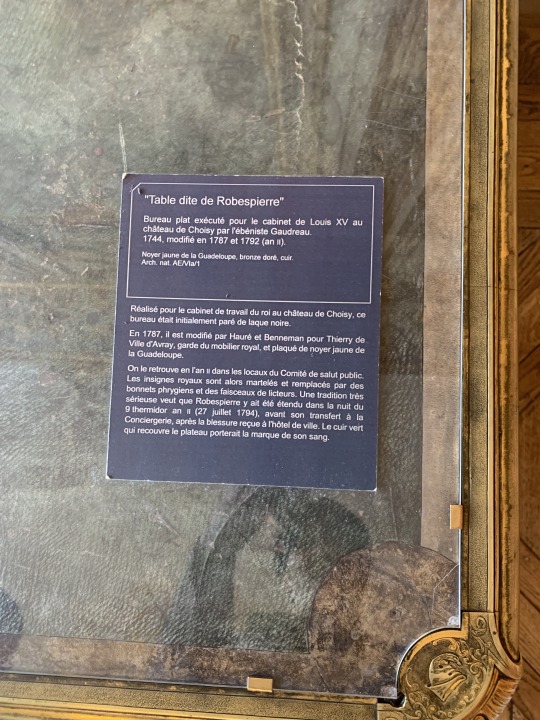

ALSO ALSO APPARENTLY the alleged table in which he layed upon during 9 thermidor is in the permanent collection in this museum?? Which i never knew before??

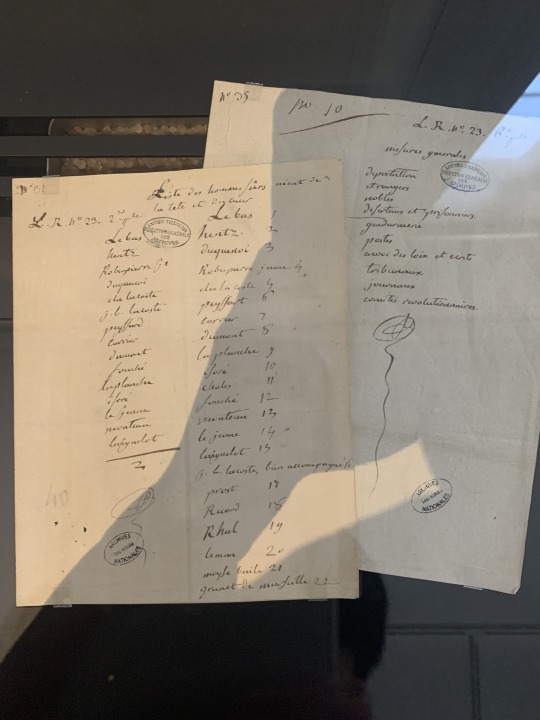

one final thing there's also a page from Robespierre's notebook that is also on display (not part of the temporary exhibit) and it's just...a list of people...with numbers associated to them? It would be very funny if he is ranking them and giving them each a score based on how likeable they are lol

The exhibit continues all the way till July 3rd! But then it will reopen again in later months I believe.

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

a kind soul uploaded on YouTube an old French miniseries about Toussaint Louverture with English subtitles! i’m about one hour in and so far it’s pretty good (bonus for the least charismatic Bonaparte i’ve ever seen lmao)

link

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille Desmoulins at Palais Royal by Félix-Joseph Barrias

215 notes

·

View notes

Note

wtf is the bordel patriotique????

An erotic pamphlet from 1791 written under the name of the queen, which features almost every relevant figure of the revolution at the time.

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

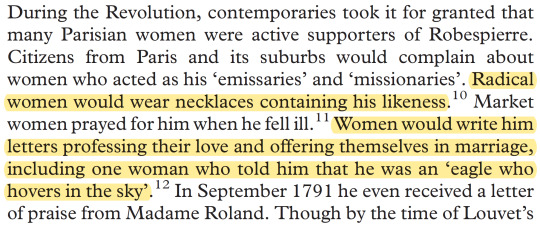

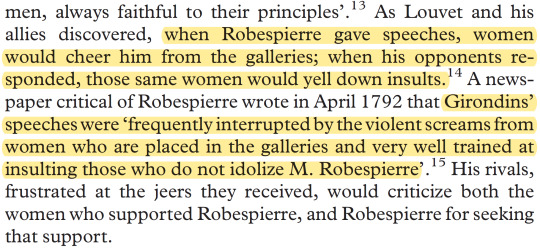

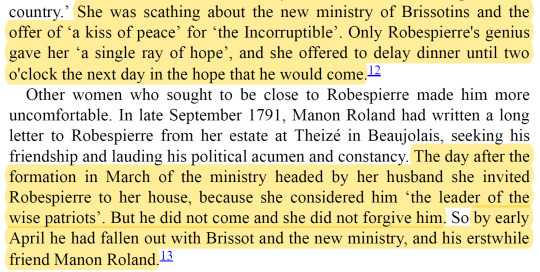

one of the funniest things about studying Robespierre is discovering he was actually a revolutionary heartthrob...while being a scrawny autistic nerd whose popularity with women confused everyone in the national convention, including himself. he was a Tumblr sexyman two hundred years before Tumblr.

from “All of His Power Lies in His Distaff: Robespierre, Women and the French Revolution” by Noah C. Shusterman

from “Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life” by Peter McPhee

(As for Robespierre being autistic, it’s extremely obvious once you study what he was like, how he behaved, and how people reacted to him, but just read these contemporary descriptions of him for an idea)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Terracotta bust of Maximilian Robespierre.

Terracotta bust of Augustin Robespierre.

Both busts are displayed next to each other at the French Revolution Museum in Vizille, France.

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Ce n’est point assez d’avoir renversé le trône ; ce qui nous importe, c’est d’élever sur ses débris la sainte égalité et les droits imprescriptibles de l’homme. […] Vous avez chassé les rois : mais avez-vous chassé les vices que leur funeste domination a enfantés parmi vous ? »

- Maximilien Robespierre, Lettres à ses commettants #1, 1792

139 notes

·

View notes

Note

What would you say it’s the biggest misconception about French revolution?

If I have to choose ONE thing, I’d say it would be that what is known as the Terror was not a specific government policy and that it was retroactively constructed as such for political gain of a specific group of people.

Expanding from that: what happened in 1793-1794 should be viewed as a state of emergency as a response to war – while not everything that happened is directly related to the war, this is a key component that is often missed when discussing the Terror. Many people don’t even know that France was at war and that the state of emergency due to this is a common thing that happens at the state of war. Things like martial law introduced, more powers to the government, stricter laws (particularly for military misconduct and treason), suppression of the constitution and civil rights and freedoms – all of this is a pretty standard set of measures that happen during wartime. (True for frev, World War II, current war in Ukraine, etc.) And this is also true for suppression of any inside rebellions that go against the war effort and the government. Nobody says that people have to like and support what happened during what we know as the Terror, but it is important to contextualize it correctly. (And nobody says that what happens during emergencies is nice necessarily - it's just that state of emergency is kind of a standard response to the war situation and has to be viewed as such, vs as some sort of a special case that happened during Terror because of evil revolutionaries/Robespierre/etc).

And also related to this, it’s important to say that while they did manage to win the war (at that point), the way that these measures were implemented was faulty. It was faulty not because the government had so much control over France, but quite the opposite – the biggest problem was that they had very little control. The infrastructure was not there, the institutions were not there; they were basically inventing/perfecting the modern government system on a large territory that just was not ready for it yet (both in institutional AND cultural sense). It was not possible to control properly what was going on. They tried (and some of those attempts were better than the others, some were bad, some were horrible, etc.) but they had no proper control. The situation during Terror was more akin to anarchy than a powerful authoritarian state (led by Robespierre) that is often imagined. Everyone implemented emergency measures in their local community how they saw fit, which led to some of the worst crimes committed during this period. And part of the problem were vague instructions from Paris (so it’s not like they don’t have their own share of responsibility). So, it was more of a chaotic mess + war with half of Europe + counter revolutionary conspiracies inside and outside (another misconception was that revolutionaries were paranoid about this – nah, this shit was real. The problem was that they didn’t always go after the right people who were to blame for conspiracies, but conspiracies def existed).

571 notes

·

View notes

Text

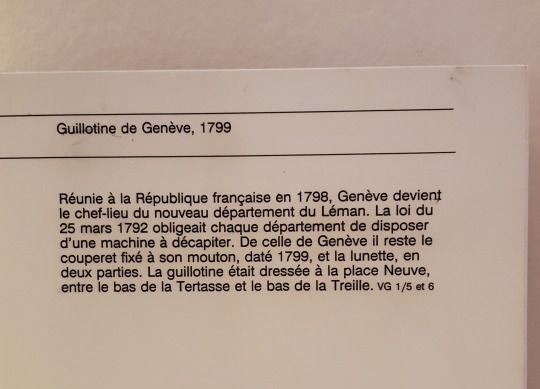

The guillotine of Geneva kept in the maison Tavel museum used to be just the blade and the lunette, and in 2019 I’ve seen a sign saying they were restoring it

I’m back today and I’ve just seen a teacher followed by their students dramatically go THE GUILLOTINE!!! with a theatrical arm gesture as their group reached a room

I had no idea they were going for the whole tall, threatening thing!

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

what does he mean by the "Invasion of marxism"? the creation of the third republic? anyway this entire quote is... chef kiss

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Élisabeth Lebas corrects Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des girondins(1847)

Source: Le conventionnel Lebas: d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1901) page 327-331

Volume 4 — page 341: ”Saint-Just… mute as an oracle and sentient as an axiom, seemed to have stripped away all human sensibility to personify in him the cold intelligence and the ruthless impulse of the Revolution, etc… his passion had, so to speak, petrified his entrails. His logic had contracted the impassiveness of a geometry and the brutality of a material force. It was he who, in intimate and long-lasting conversations in the night under Duplay's roof, had most combated what he called Robespierre's weaknesses of soul and his reluctance to shed the king's blood, etc.” (In the hand of the son of Lebas): My mother did not recognize Saint-Just in this portrait. Where do you know that from?"

Volume 5 — page 65. (Interior aspect of the Convention during the trial of Louis XVI): ”The first benches of these popular stands were occupied by butcher boys, their enameled aprons rolled up on one side of their belts and the handles of long knives, etc…” Mark of denial.

Volume 5 — page 73: ”Robespierre, having returned to Duplay's house that evening and discussing the king's judgment, seemed to protest against the vote of the Duke of Orleans: 'to listen to his heart and to recuse himself, he did not want or he did not dare to do it: the nation would have been more magnanimous than he!” Word from Robespierre on d'Orleans made up.

Volume 6 — page 35: “The bourgeoisie, the bank, the upper class, the men of letters, the artists, the landowners, were almost all of the party which wanted to moderate and contain anarchy. They promised the orators of the Gironde an army against the suburbs, etc…” Lamartine does not explain the temporary triumph of the Girondins. See my husband's letters.

Volume 6 — page 300: ”Love warmed, without softening, the hearts of these men. Couthon's tenderness for the devoted woman who consoled his infirm life, Saint-Just's stormy and passionate feelings for Lebas's sister, Robespierre's grave and chaste predilection for his host's second daughter, Lebas's love for the youngest, etc…” Correction: very calm feelings.

Volume 7 — page 105: ”Fort Vauban was taken by the Austrians, Landau was about to fall. Saint-Just and Lebas were sent to Alsace to intimidate treason or weakness with death.” (Mark of protest.)

Volume 7 — Page 212: (About the proscriptions of Collot d'Herbois and Fouché in Lyons.) "Fouché, in his letters to Duplay, endeavored to circumvent Robespierre, and presented Lyon as a permanent counter-revolution." Letters of Duplay — false. [1]

Volume 7 — Page 232 (Imprisonment of Madame Roland) “They arrested her in spite of her summons, and threw her into another prison, at Sainte-Pélagie, that sewer of vices where the prostitutes of the streets of Paris were swept away. One wanted to debase her through contact and torture her through her modesty.” (Note from the son of Lebas:) Madame Roland was sent to Sainte Pélagie by the Commune; my mother to Saint-Lazare by the Thermidorians.

Volume 7 — page 287 and following: ”Robespierre, now dominant in the Committee of Public Safety, threw in notes, since revealed, the vague outlines of the government of justice, equality and freedom… When will, he wrote, their interest (interest of the rich and the government) be confused with that of the people? Never! "To that terrible word, etc...." Never! — Papers seized and falsified by Courtois. [2]

Volume 7 — page 341: ”Saint-Just… brought to the battlefield the enthusiasm of his youth and the example of an intrepidity that astonished the soldier. He spared no more his blood than his fame, etc…” So his heart was not petrified.

Volume 7 — page 342: ”He sent to the guillotine the president of the revolutionary tribunal of Strasbourg…” He sent to the revolutionary tribunal.

Volume 7 — page 343: ”Lebas, his friend and almost always his colleague, had been Robespierre's classmate.” Fellow patriot, not classmate.

Volume 7 — page 344: ”Lebas had become the commensal of this family (the Duplay family).” Not the commensal: the friend.

Volume 7 — pages, 344, 345 et 346 (reproduction of letters from Lebas to his fiancée). Made up letters.

Volume 7 — page 396. ”Hébert’s wife, a nun freed from the cloister by the Revolution, but worthy of another husband, frequented the Duplay house.” Invention.

Volume 7 — page 409. (Arrest of Hébert, and his friends) “They lamented, they shed tears, a spy of Robespierre, imprisoned as their accomplice, in order to reveal their confidences…” A spy of the Committee. (The Committee of Public Safety which had just instructed Collot d'Herbois to replace Robespierre at the session of the Jacobins which immediately preceded the arrest.)

Volume 7 — page 411: ”Robespierre's dark imagination magnified everything.” Courtois.

Volume 8 — page 8. (Attempt to reconcile Danton and Robespierre): “An interview was accepted by the two leaders. It took place at a dinner in Charenton at the house of Panis, their mutual friend…” Narrative of the dinner meeting between D and R — Melodrama.

Volume 8 — page 67. (Robespierre's words on the death of Danton and Camille Desmoulins): ”Poor Camille! Why couldn't I save him! But he wanted to get lost! As for Danton, I know very well that he clears the way for me; but it is necessary that, innocent or guilty, we must all give our heads to the Republic…” (Lamartine adds): “He pretended to moan…” He pretended to moan (Mark of protest)

Volume 8 — page 76: (About the letter from Madame Duplessis in favor of her daughter Lucile Desmoulins) “This letter remained unanswered. Robespierre… either did not receive it, or pretended to ignore it. He was silent…” Who proves that he received this letter? If he did not receive it, why reproach him for not having paid attention to it?

Volume 8 — page 153. ”Saint-Just, his only confident.” His only confident?

Volume 8 — page 159: ”…Finally, Courtois, deputy of Aube, friend of Danton, having never applauded his crimes but never betrayed his memory, an honest man whose honest and moral republicanism had not hardened his heart. Praise of Courtois!

Volume 8 — page 207 (Feast of the Supreme Being): “A symbolic mountain rose in the center of the Champ-de-Mars, in place of the old altar of the fatherland. Access was difficult. Robespierre, Couthon carried in an armchair, Saint-Just, Lebas, placed themselves alone on the summit. ?

Volume 8 — page 249. (About Dom Gerle): ”Robespierre often received the former monk at the Duplay’s.” (Note from Lebas's son:) My mother saw him two or three times.

Volume 8 — page 255: ”Trial, a man of the theater and mutual friend, took Robespierre to Madame de Sainte-Amaranthe. He was received there as a dictator. He sat down at the table in the middle of a circle of guests chosen by himself, etc…” Interview of Robespierre with the Sainte-Amaranthe — false

Volume 8 — page 257: ”Make every effort, Payan wrote to Robespierre, to diminish in the eyes of public opinion the importance that they want to give to the Catherine Théos affair…” Payan. — is his letter authentic?

Volume 8 — page 278: ”The fear that the insurrection, without moderator and without limits, would break out of its own accord and carry off the Convention, which he regarded as the only center of the country, finally determined Robespierre not to act, but to speak. … He only recalls Saint-Just, his brother and Lebas, to assist him in the crisis or to die with him. (Note from Lebas's son) My father had been in Paris for six weeks and more.

Volume 8 — page 366. ”Robespierre, carried by four gendarmes on a stretcher, his face covered by a bloody handkerchief, led the procession. The carriers of Couthon, etc. Robespierre the younger, having fainted, was carried by his arms by two men of the people. Lebas' corpse was covered with a bloodstained tablecloth. Saint-Just… followed on foot.” The corpse of Lebas — Error. (It is these passages from Lamartine that Mme Le Bas seems to be referring to in the last part of the manuscript reproduced above.)

Volume 8 — page 369. ”After the dressing, the wounded were all transferred and brought together in the same cell at the Conciergerie. Saint-Just would wait for them there beside Lebas. — ibid

Volume 8 — page 370. ”At five o'clock, the tumbrels were waiting for the condemned at the foot of the main staircase. Robespierre, his brother, Couthon, Hanriot, Lebas were either human remains or corpses. They were tied by the legs, by the throne and by the arms, to the wood of the first cart.” — ibid

Volume 8 — page 374: ”These twenty-two thrones were thrown pell-mell into the dumpster with the corpse of Lebas” — (We have already said that this passage, on the edition of the History of the Girondins owned by Mrs. Lebas, was annotated with the word ” No")

Volume 8 — page 372: (At the time of the passage in front of the Duplay house, of the tumbrel driving Robespierre to the execution) ”A child was holding a butcher's calf filled with ox blood and deceiving a broom on it, the goettes were thrown against the walls of the house. Fable.

Volume 8 — page 372: On the evening of the same day, these furies of vengeance invaded the prison where Duplay's wife had been thrown, strangled her and hung her from the rod of its curtains. That very evening its furies — la Lacombe.

[1] Élisabeth is mistaken here, Collot d’Herbois did in fact send a letter regarding Lyon to Maurice Duplay December 5th 1793.

[2] Élisabeth is mistaken here, the ”catechism” where Robespierre wrote this has been accepted as his.

99 notes

·

View notes