Freedom is a state of mind. Freedom of mind and freedom of expression are the bedrock of human society.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Have I lost my groove? (Did I ever have one?)

The first time I saw Rod Stewart he was still a blues shouter. He stood comfortably alongside Long John Baldry and Chris Farlowe and needed no apologies. He was good. Songs like “Gasoline Alley”, “Only a Hobo”, “Cut Across Shorty”, “Street Fighting Man” and “An Old Raincoat Won’t Ever Let You Down” provided a perfect medium for Rod’s voice, an amazing blend of Scottish falsetto and pure gravel. Then there was that first version of Mike d’Abo’s beautiful “Handbags and Gladrags”, which he sang with all the raw emotion that the later saccharine version missed.

The second time I saw him was at the old Wembley Stadium, fronting for the Faces. I say “saw” but they were just tiny doll figures off in the distance. Fortunately, they were loud. And it was such fun, the way rock music was supposed to be. By that time, Maggie Mae had brought them to Top of the Pops and we had the added pleasure of watching the cameras try to avoid capturing John Peel pretending to play mandolin – and Rod doing everything he could to thwart them. Yes, it was fun. But it also had the power to take me over. In so far as this repressed mummy’s boy could allow himself to let go.

But I swear that inside this buttoned-up boy I was capable of hearing the music. The first time In heard Springsteen on the radio, I was in bed with ‘flu, but “Born to Run” set a fire that I have never forgotten. Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac rendered me deaf for at least 48 hours and left me with tinnitus but the music thrilled me. They didn’t need to be prancing around in their underwear, as every wannabe pop star seems to have to today.

When did I lose that enthusiasm? Did I lose it?

I lost my appreciation for Rod not long after he split with the Faces, apparently convinced that he was a solo superstar who could sing. When he came out with “Do you think I’m Sexy?” I had no hesitation in answering, “Sexy? No. Sleazy? Definitely.”

It wasn’t just Rod. Paul McCartney was, in my view, proving conclusively that without John Lennon he was just a purveyor of vapid pop. “Maybe I’m Amazed” was the last song of his to send a shockwave through me. I plead “Mull of Kintyre” and a host of other catchy little bits of tat in my defence.

Maybe the fault was mine. To quote the late night conversation between Brady and Drummond, in the stage play “Inherit the wind” –

Brady: We were good friends once. I was always glad of your support. What happened between us? There used to be a mutuality of understanding and admiration. Why is it, my old friend, that you have moved so far away from me? Drummond: All motion is relative. Perhaps it is you who have moved away – by standing still.

Perhaps it is I who have moved away from Rod and Paul by failing to appreciate their shift from strong performances and well-written songs towards crowd-pleasing crap. But maybe not. I quickly lost interest in Nile Rodgers’ boastful set this weekend after it became apparent that he was just playing slight variations of the same song over and over; and The 1975’s set only confirmed to me their appalling mediocrity and Matty Healy’s unwarranted good opinion of his own talent. But I was hugely impressed by CMAT and genuinely moved by Lewis Capaldi’s courage and songwriting.

I know the old adage “Old rockers never die,…” It has several versions of an ending. I quite like “… they just fade out at the end.” But frankly, Rod’s performance on Sunday at Glastonbury left me trying to feel sorry for the old feller, shaking his butt at all the wrong moments and struggling to hold on to the tunes. It only livened up when he wasn’t trying to sing or when Ronnie Wood and Lulu came on (the less said about Mick Hucknall the better).

Rod has never had great sartorial taste and that at least remains true. It appears now to be matched by an appalling lack of political judgment, if, as has been reported, he really thinks we should “give Farage a go”. The only thing I would give that egregious spiv a go on would be as pilot of Elon Musk’s first rocket ship to Mars, with musk and Bezos aboard. Perhaps it is time for Rod to devote himself exclusively to his trainset.

But the upshot of watching him attempting his old numbers yesterday was that this morning I broke out the originals to remind myself that once upon a time he was a contender.

It worked.

0 notes

Text

Regime change now

He’s a misogynist. He’s a religious phoney. He is presiding over a corrupt administration. He is daily violating the human rights of his own people. He is using oppression to hold onto power. He has built a nuclear and military arsenal that threatens the free world and he is so irrational you can’t guarantee he won’t use it. He even dresses oddly.

Yes, it‘s Donald Trump I am talking about. The world really deserves a regime change. This man-baby is putting the rest of us at risk for no better reason than to fuel his own crass belief in his ineffable greatness. The world has had its Caesars, its Il Duces, its Moghuls, its dynasties, its pharaohs, its Hitlers and Stalins, its Pol Pots. But it has never known the like of Donald J Trump. He is the Best Worst Tyrant in all history.

All these others were weak beside him. They all believed in something outside their own ego. They all had a sense of their own responsibility for failure. That is not a mistake Donald is about to make.

It is not as if he has any choice in the matter. His stupid, unchecked ego is all he has. You can call him a liar but it is meaningless because truth has no meaning to him, beyond what spews from those pretty little pursed lips when he speaks. You can call him a fraud but it has no meaning because to him morality is, and only is, about Donald getting what Donald wants. You can call him a lecher but to him that is what his stupid prick tells him is his right.

All hail the King Rat. The apotheosis of American “culture”. Greed and lust and wickedness personified. The American Dream.

But when we have done worshipping this creep, let’s get back to quality, integrity and decency. Hell, even Richard Nixon was better than this.

0 notes

Text

A Wreath for the BBC

Before John Reith came on the scene

Our choice of listening was mean

A distant strangled baritone

Trapped in a wind-up gramophone

Or trudge through mire to costly stalls

In one of Britain’s concert halls

To remedy this paucity

John brought us all the BBC

All hail the new democracy

Enlightenment for you and me

It didn’t matter who you were

A Lord, a boss or his chauffeur

If you could find a wireless near

Broadcasts were for you to hear

Just turn the dial to hear the station

Speaking truth unto the nation

But some decried this new excursion

Saw this medium as subversion

Teaching plebs to think? Disgrace.

They’ll quickly lose their sense of place.

They’ll fill the air with mindless chatter

With Clitheroe and cockney patter

Still our Home Service kept its nerve

Brought us the fare that we deserve

With ITV came new complaints

“You’re strapping us with new constraints

We can’t compete on quality

While profiteering, can’t you see?”

They had the Tories on their side

A gravy train for spivs to ride

They urged the BBC’s demise

Into another ad franchise.

But Murdoch had a smarter thought

What if the BBC was bought

And placemen filled its upper floors

In hock to me and Tory whores?

We wouldn’t need to gerrymander

If we controlled the propaganda

And so the BBC became

Truth speaking only in its aim

The racist spivs once got short shrift

For peddling lies to suit their grift

But now they have a seat reserved

On Question Time though undeserved

As Chairmen strive to find a balance

Between what’s real and all their nonsense

Thus conscience doth make cowards kneel

Before these liars and their spiel

The BBC, once justly famed

For drama, sport and arts, is blamed,

And put to torture on the rack

By politicians who lack

An interest in truth or candour,

Wanting flattery or blander

Treatment from the people’s station

That once spoke truth unto this nation.

0 notes

Text

Defence

I was walking down the corridor at school trying to find the classroom where, unless we could distract him again with calls to relate to us his experiences as an air-raid warden in Little Thew, we would face an hour of Mr Quick’s Latin declensions. Amo, amas, amat, – who could learn to love that? Omne taedium in tres partes diversa est.

All of a sudden there was a thud in the small of my back that sent me sprawling onto the floor. It was followed by a boot to the ribs and another that caught my thigh as I swiftly curled myself up into a protective foetal ball. Fighting for breath I looked up. Standing over me, a wet snarl on his face, fists clenched, was Pratt. He was already lifting his leg for another strike.

Ian Pratt was a little runt of a boy who made up for his diminutive stature by exhibiting an unflagging hatred of anyone else, with particular reference to anybody bigger than him. Which, let’s face it, was most people. Some people have a chip on their shoulder. Pratt carried an entire fish shop extra large portion on his, reeking of the sour vinegar of years of accumulated victimhood and resentment. By dint of his ungovernable aggression he had gathered around him a gang of mentally and emotionally challenged hangers-on who saw their function primarily as a Greek chorus of wannabe bullies. They swaggered around the school in his malevolent shadow making lives miserable wherever they went like it was a sacred vocation.

The received wisdom was that if you couldn’t be in the gang you tried your best to keep out of their sight. Which was easier said than done when, like me, you were already a foot taller than Pratt and had a mother who insisted on your uniform being pristine, your shoes polished to a mirror shine and your cap straight on your head and a father who in 1964 still insisted on a short back and sides and trousers with turnups. And we were in the same damned year.

From somewhere, I found the breath to speak. “What have I done? I haven’t done anything.”

Pratt paused the swing of his boot. “Not yet, you ‘aven’t.”

I was thrown by that. “What do you mean?”

Pratt’s answer was immediate. “I ‘ave a right to defend myself.”

Immediately the two flabby members of his gang standing behind him chimed in. “That’s right. He has a right to defend himself.”

I could’nt help myself. “But… but… I haven’t… I wouldn’t… I haven’t touched you, Pratt.”

“Not yet, as I say. But that’s why I’ve got to defend myself, right. In case you ever think about it.” And then the boot landed again.

It was a lesson in itself. One that I carry to this day. And when I listen to the news, it all makes sense. Some people just have a right to defend themselves. Even when they are not under attack.

0 notes

Text

Pet frowns

I know we shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, and, honestly, that is not what I am about here.

It’s just all these claims that Brian Wilson was “a genius”. And with it, the claim that, somehow, Pet Sounds was “a masterpiece”. He wasn’t and it wasn’t.

Don’t get me wrong. Wilson wrote some good songs and a handful of absolutely fabulous ones. To have written just one of the fabulous songs would have been the pinnacle for most pop singers in the last six decades. But most of the rest, even the surfing classics that we rained-in Brits learned to think of as a part of our summer, were one dimensional ditties made slightly more interesting by the use of barbershop harmonies (just as some of Lennon and McCartney’s output was lifted out of banality by the harmonies they had grown up with in Liverpool and the exuberance with which they played).

Yes, Pet Sounds was a step away from those bouncy little numbers about sea and surf but it was quirky rather than excellent and, dare I say as one who grew up with it, for the most part, boring. There are hundreds, thousands even, of better, more original, more inspirational, songs and better albums, made both before and after it. For the most part it was just over-produced pap. The musical equivalent of a steelworks. Plonk plonk, bang bang, thud thud, whoop whoop. And only three of its 12 songs have proved in the least bit, memorable.

But Wilson has at last died and that provides the opportunity for all the self-appointed gurus of greatness to submit achingly glowing articles extolling Wilson’s all-time greatness.

God Only Knows and Good Vibrations were great songs. Don’t Worry Baby is a lovely ballad. But Ray Davies, Pete Townsend, Jimi Hendrix, Paul Simon, The Beatles, The Stones, Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, John Martyn, Janis Ian, James Taylor, Carol King, Burt Bacharach and a host of others have back catalogues strewn with songs that are at least their equal, as compositions and as arrangements. Detroit was churning out pop masterpieces way before the Beach Boys even hit their stride. Songs that have equally stood the test of time without any obvious influence from Wilson.

No I am not going to speak ill of the dead. Brian Wilson was a good song writer and sometimes a fine arranger and the best of what he produced is up there with the best of the rest. When the sun shines, it is still a joy to reach for the Beach Boys’ Greatest hits and revel in the easy, happy music. But “Genius”? No. Let’s reserve that word for the truly exceptional. Bach was a genius, So were Haydn, Beethoven and Mozart. They truly did move the music along. Brian Wilson sometimes wrote good pop songs. And that is enough commemoration.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Paradox Lust

“No He didn’t take very much Just your flesh from the bone” Al Stewart, Anna from Zero She Flies

To anyone who thinks they’ve been here before, I am sorry. I have been trying to get my head around this for a while. I just hope I can get it right this time. More right, anyway. Though I doubt it. Not because the truth isn’t there to be had but because of my limited ability to grasp, and then express, it.

I must first introduce Clare. We first met over a telephone line. It was her first day as a government lawyer. Literally. She had been sent to a remote court on some departmental business and while there she met some clients of mine. They needed urgent legal help. They weren’t her clients. She knew nothing about them. But she phoned me after they approached her and I asked her if she would help them. Without a moment’s hesitation she leapt into action and the next thing I knew was that my clients were phoning me to insist that she receive credit for saving their day. I was happy to do so.

It wasn’t until months later that she joined my team and I met the young woman who had risen so magnificently to an immediate challenge. And I was stunned. She was beautiful. I would like to be able to say that it was only her mind that captivated me but truth is that it was inseparable from the radiance of her presence. Not for the first time, I fell instantly, besottedly and childishly in love.

I am not exactly proud of that confession. And in a way that is what this needs to be about. Clare was in her late twenties, newly qualified, newly appointed. I must have been in my late forties, A team leader, married and with a young child and a second on the way. I could say in my defence that my marriage was already on the rocks but that doesn’t wash because I still loved my wife and, as I now realise, a lot of what was wrong was my fault.

(One of the only lessons my pupil master ever taught me when I was a trainee barrister was “It takes two people to break up a marriage, except in the case of adultery, when it takes three.” Cynical but clever.)

Anyway, nothing was ever going to come of my infatuation. I made sure of that. The one truth in my whole life until then had been that if I fancied someone there immediately arose – no let’s be clear, I built – a massive wall of unsurmountable self-disgust between us. It was my dogma. No-one I loved could possibly love me.

And that is where this story begins. It should begin with a mantra that I had deployed for so long that it came out without thinking or correction. In my head, it sounded witty, a bit like something Oscar Wilde would say on a bad day. It went like this.

“Do I feel my age? No, most of the time I feel no more than forty. Except when I am in the company of a beautiful woman. Then I feel about fourteen.”

To be as fair as I can to myself, I only came out with this piece of near sophistry when someone expressed disbelief at my real age. But that had become a standard occurrence. I did look startlingly young, all the time: a bit like Dorian Grey was said to, but without the picture.

The trouble is that the mantra had became so automatic a response that, if I ever had given any serious thought to what it actually implied, I no longer did. And that has remained the case until now.

Anyway, back to Clare. My infatuation did not diminish over time. Rather, it embedded itself, as unrequited infatuations tend to. She did not work for me for long (others recognised her astonishing talent as a lawyer and were keen to exploit it) but, from that first actual encounter even the sight of her from across the room at any event we attended would take hold of my concentration and the only thing I was then capable of thinking was how lovely she was and how I wished she was mine. At every office party, I would be restless until she appeared, usually in the company of other bright young things, intellectual butterflies floating around her sainted head. But in her presence, I would be tongued-tied, rendered stupid by the feelings I could not dream of expressing, believing “in my heart” that she would not find them welcome. To me, she became “The Blessed Clare”. She was Dulcinea to my Don Quixote.

Clare, being a truly wonderful human being, allowed my infatuation without any hint of resentment or reciprocation. This was not, I swear, out of any coquetishness on her part. She had a great sense of fun but not of mischief (though her integrity did, I think hold her back within the Government machine, which was at that time obsessed with fostering a “can do” approach to our trivialising, transient political masters: Yes Minister without the irony). She always spoke gently to me, as if she knew that I was struggling inside. She was kind. Always.

Years passed, and suddenly the news came from a friend and fellow admirer that Clare had been struck down with a brain tumour. To my shame, I did not rush to her bedside but watched from a distance as she fought for recovery and made a return to work. I never saw her again and eventually I heard that the cancer had come back for her and killed her. She could only have been in her thirties, in her prime. One of the best of us.

For the next twenty years she has never been far from my mind, a fitting punishment for my cowardice. But now you know this, I can at last bring the story up to date.

Clare was with me in my head when I woke a few nights ago. I felt guilty for having called her up even though I knew that this was just a trick of my own brain. But somehow her presence triggered a memory of all the other young women I had “fallen in love with”. And that made me guiltier still. I asked myself the obvious question: which one would you choose if you could? And I could not answer. There was Clare and Catherine, Pam and Anna (all from work), Stassy, Anna, Faye, Issy, Reitseal, Jen, … the list went on through the years. All of them had this much in common: my infatuation. That and the form it took: hopelessness. I craved sight of each of them, craved their company, even from a distance, but also from an unbridgable acceptance that I could not begin to let them know how attracted to them I felt.

All these young women were radiant. All of them bright with promise, all of them bursting with positivity and kindness. And all I could do was worship them from afar. Why?

And that was when a spotlight came on in my head and I saw it pan round and focus on that mantra –

“Except when I am in the company of a beautiful woman. Then I feel about fourteen.”

Why “fourteen”? And then I saw it. It was a coin with two faces, a Janus beast. On the one side, I was fourteen when I first started lusting after girls. And on the other, I was also fourteen when the idea became locked in my head that I was ugly, that no girl would be, could be, interested in me. It was a wonderfully convenient thought. It saved me from trying. In the quiet of my own bedroom I could fantasise about the girls who surrounded me, at school, in town, in the library, knowing that in their actual presence I would immediately become shy and voiceless and useless. In fact, fantasising about them in private only compounded my difficulty as in their actual presence I was immediately aware of how shamelessly I had objectified them in my head.

For decades, I have blamed my mother for this. I know that she did play a part in making me feel that any association with a girl was unsavoury. I felt it would be disloyal, to her, even to appear to be attracted to one of them. It blighted my first love, for Caroline, which remained totally platonic until the poor girl had had enough of my depressing distance. But I see now that there is more to it than a boy’s devotion to his mother. I see that the truth is that I was scared. Scared of the banal teenage intensity of my feelings, scared of the commitment that any hope of realising those feelings seemed to imply, scared, above all, of the possibility of rejection.

It was less dangerous in my mind to be the hapless apprentice celibate than to put myself out there.

And that became embedded in my brain, no longer thought about, just acted on: “Except when I am in the company of a beautiful woman. Then I feel about fourteen.”

But now I was seeing the awful truth in the words of my mantra. And now, suddenly, I could see how it had carried on even unto my eighth decade. Still, in the presence of a beautiful young woman, I was reverting to that fourteen-year-old and his repression. And that was why I had defaulted to “falling hopelessly in love” every time I met one.

I have no doubt that Andrew Tate, bless his little cottonwool brain, would sneeringly tell me that I was a wimp and not fit to call myself a man, that I should be, and should always have been, “taking what was mine by rights”, that it was ”what women are for”. I should like to be able to answer him dismissively that I prefer to respect the women I meet and to acknowledge their right to choose.

But the truth lies neither with him nor with me. By hiding from my feelings, I ensured that nobody I met could choose, one way or the other.

And by hiding my feelings from Clare, I deprived her of exactly that right. She probably would have rejected me. That was her right. But I shut the door on the possibilities. And all that I have left are the regrets and the guilt.

Meanwhile, the Blessed Clare is gone.

“It’s going to be Hard for a while Trying to get by On your own.”

0 notes

Text

Raining in my app

Apologies to Huddy Brolly

I should go out

To buy some bread

But there’s a problem

In my head

Cos it’s raining

Raining in my app

My window says

The weather’s fine

There’s washing hanging

On next door’s line

But it’s raining

Raining in my app

Oh mystery, mystery

How can I trust what I see

I tell myself

I won’t get wet

The sun is shining

It’s safe and yet

It’s raining

Raining in my app

0 notes

Text

Bank Holiday Blues

I remember, I remember

Days out by the sea

Mum and Dad sat in the front

Sister sitting next to me

I remember, I remember

Hours spent on the road

Nose to tail for forty miles

Bladders ready to explode

I remember, I remember

Parking at the front

Bonnet pointing out to sea

Windscreen bearing all the brunt

I remember, I remember

Coffee from the flask

Grey as cardboard, flat and grim

Not even condensed milk could mask

I remember, I remember

Corned beef sandwiches

Slabbed between curled sliced white bread

Greaseproof wrapped, no garnishes

I remember, I remember

Windscreen wipers swishing

Fighting to preserve the view

Against the rain’s infernal lashing

I remember, I remember

Vying with my sister

My raindrop or hers to win

Coat sleeves used as our demister

I remember, I remember

Trying to hold my pee

Wriggling on the leatherette

Hoping Mum and Dad won’t see

I remember, I remember

Dragged out to the gents

Hold your breath, look straight ahead

And never mind the awful stench

I remember, I remember

Driving home again

Dad cursing all the other cars

As we queue in the teeming rain

I remember, I remember

Memories all shades of grey

Cold and wet and miserable

Every damned bank holiday

0 notes

Text

Reform my arse

I suppose it was inevitable. As with the rise of Fascism in England in the thirties, the BNP in the 80s and 90s and then UKIP, political illiteracy supported by consumerist avarice, bad education, a corrupt media and a diet of awful American culture was bound to give rise to that heartburn in the British electorate that is presently manifesting as support for “The Reform Party”.

People who have made themselves too stupid to tell the difference between fact and fiction are easily sucked in by the gobshite promises of that prince of spivs, Nigel Farage, as he preys on their disappointment, disillusion and distrust to line his pockets at their expense. They do not understand, perhaps just plain do not care, that he offers, and intends to offer, no solution to their trumped-up woes. He gives their desire for toil-free, cost free utopia a voice, or appears to, as snake oil salesmen always have.

He does not want to govern. He only wants power, the power that comes from provoking dissatisfaction. Talking of fact and fiction, anyone who has seen Monsters Inc should be able to understand his schtick. Misery is a powerful source of energy to be tapped for his private advantage. Happiness would work ten times better but other people’s misery is so much easier to contrive and manage.

Well, I’m not buying it. And nor should the British people for long. “Reform” is like a salt and water mouthwash. It may be a good short-term device for keeping wounds clean but it tastes disgusting and you should never swallow it. Rinse with it, then spit it out.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victoria

I have a confession to make and I am afraid to make it here. You see, I have always sought the approval of those around me. I like to be thought well of. And yet the only people likely to approve of what I am about to say are the kind of people who, for the most part, disgust me. There is a part of me that is trying to persuade me that it is okay and that I have done nothing wrong, that this is just how men are. I don’t know if that is true and, frankly, it doesn’t matter if it is, though I hope it isn’t. What matters for now is that it is what is in my head and that I need to own it while I can. It is, when I can bear to think about it at all, about as ugly as I can imagine, which is perhaps why I have suppressed it for so long.

The news that Victoria Guiffre had taken her own life shook me when I read it a week ago. It brought back to me - and this is my confession - that when I had first seen that picture of her as a young girl, allegedly being held round the waist by our most tawdry prince, my immediate response was to think “what a pretty young thing, I wouldn’t have minded making out with her.” And every time since then that I have seen that same photo I have had to remind myself that she was just 17 and, despite that smile, she was there under duress. I have to tell myself that it is not appropriate to look at her that way. I shouldn’t have to tell myself, but I do.

If I had one-tenth of the empathy or emotional intelligence that I have at times claimed for myself it would have taken no giant leap of imagination but the just smallest step to cross the notional boundary that appears to divide my experiences from hers and to know the agony which was her daily companion. The indelible stain of having been used, treated as an object to relieve the insatiable lusts and pitiful insecurities of self-aggrandising men.

It has not helped to be aware that if someone had been on hand with a camera at any one of my daughter’s parties from 2010 to 2020 I might have been found in the same pose as the tawdry prince with any one of a number of my daughter’s friends who would have been around the same age. And in case it needs saying, the fact that they were there of their own volition and that they had invited me to put my arm around their waists makes not a smidgeon of difference. It was very flattering, for the ageing me, but it was not appropriate and I should have known that. And, even more significantly, on some level I did know that.

I can offer in mitigation that it never went any further than these little displays of affected affection. I can say that it was always “of their choosing”, that I never once imposed myself on even one of them. I can say that the girls were just being happy and open with me. I can try to defend myself by saying that “any red-blooded male” would have found himself attracted to these lovely, nubile young things. Does it change anything? No.

What a terrible word “nubile” is. It sounds so warm and innocently cuddly. It encourages you to lay the whole “attractiveness” thing at the door of the young girl, something she is doing to you, and to gloss over the point that it is you who are finding her attractive. Sexually attractive.

Yes, they are old enough to bear children, physically. And yes, through most of the history of humankind that is what, at that age, they would have been consigned to, ageing prematurely, maybe dying in child birth, expecting nothing better.

But that is not where we are, surely? We know better now, don’t we, we men?

Sadly no. And I fear as long as there are men like me, men who perhaps want to behave decently but still find themselves revelling in the fantasy that these young girls, on the cusp of womanhood, might possibly find in them suitable sexual partners (until, that is, the next fantasy comes along), and worse, men who actually think it’s okay, the tawdry prince and the predatory billionaire will still find undeserved sympathy when they get caught, literally or metaphorically, with their pants down. At best we will envy them, we will be silently thinking “yes, please”. And so the depravity and the corruption and the damage will go on.

But I wonder, though it really doesn’t help me to do so, how I would have behaved if I had been a man in the room with the tawdry prince and his predatory facilitator and Victoria. I fear I might have stood by, thinking my lascivious thoughts. That is a terrible thing to have to admit.

We choose not to see the damage until it is too late. But if we are going to ensure that no more Victorias have untimely ends we have to. This is not “wokeness” (well yes, it is). It is just common decency and humanity (which is what wokeness is). And it falls to us men to put a stop to the enabling of harm. We alone can deprive these self-indulgent males of the approbation that enables them to flourish.

The only thing about us that should be standing firm is our commitment to protecting the young from exploitation. No more excuses.

Rest in peace, Victoria. Now that it is too late to save you.

0 notes

Text

Norma Jean: An American Dream

This is a bit of a new departure for me. It is an attempt to set down a short story that had been rattling around in my brain these past few days. I hope it is not too bad.

They first met on-line. When John’s drinking buddies at the bar had, from, he accepted, the best of intentions, suggested he looked at dating sites he had fought against the idea. Every time the suggestion came up, which was just about every time he met these well-meaning people, he would counter with “That’s not the way it’s done.” For a while this would close down the discussion but then they started to come back with, “Yes, yes it is. That’s exactly how it’s done now.” And he would have to change tack to “Well, it’s not the way I do it.”

And then they started saying, “And how’s that working out for you?” And he would have no comeback for that so, in the end, while making a great play of reluctance, of how he was only doing this to pacify them and he didn’t know why they couldn’t just let him be, he allowed himself to be tutored in searching on-line.

And just as he made what seemed like the thousandth swipe left and he was about to throw up his hands and say “Told you,” there she was.

To him, she was the embodiment of The American Dream. She had platinum blonde hair, curly like Monroe’s, she had a half-full cocktail glass tilting dangerously in her hand, she was wearing a white flowing dress that plunged in front to offer a tantalising glimpse of cleavage. But most of all, her eyes seemed to be looking straight through the screen at him. And her smile seemed somehow to convey both invitation, pleasure and warmth. He got the strangest feeling that she would get him.

Now his buddies were telling him to slow down. One step at a time. These things can be deceptive, you know. But when he looked at her bio all it did was make him feel more certain. It lacked any artifice or pretension. She was clearly educated but not threateningly so. She had never been married but had recently split up with a “boyfriend” who’d “turned out not to be as nice as he first seemed” but she left it there, didn’t go into details. She lived barely fifty miles away, had her own house and a car, a sensible sedan, and a job in the local library. She liked cooking but ‘cooking for one wasn’t much fun’. She had a cat – well he could get on board with that though he preferred dogs, or thought he did. She said she preferred staying in watching movies to going out partying, liked being outdoors, if the weather was nice, and loved the ocean, as long as she could enjoy it from the beach. For the first time in his life the thought of meeting someone new didn’t make him feel afraid. Crazy, he knew, but he felt they were already friends. This was the one, he was sure, the one he’d been waiting for all this time. So, she was ten years younger than him but the gap was not so big as to be a problem if she didn’t see it as one. A lot of his contemporaries were already on their second or third wives, some of them barely out of their teens.

He swiped right and waited. Things went quiet for over a week, except inside his head where he found that picture interrupting his work, his play and his sleep.

He was about to give up and give his friends hell when he got her message. She began with ‘sorry for keeping him hanging’ but said she’d ‘been a bit scared by his show of interest and needed time to think’. He found that pleasantly reassuring. She told him she’d always loved books, so being a librarian, which she knew would not appeal to everyone, had seemed the perfect job for her and she couldn’t see that changing. Again, he liked that, it showed she had character. And then she said “Would you like to meet for a coffee or something?” He immediately shut his laptop at that. It was as if an electric shock had passed from the screen directly into his brain. Suddenly, the comfortable remoteness lent by IT had been shattered, and now he was the one feeling scared.

When he mentioned her message, the reaction at the bar was immediate. Never agree to meet someone you only know from social media. Some of them even painted graphic pictures of cellars and chains and torture. But he thought, what’s the point of all this then? Sometimes you just have to trust, go with your gut. And she seemed really nice, genuine. So, paradoxically, their concerns only strengthened his determination to take the next step that she had suggested. What did he, a lonely forty-something insurance clerk, have to lose?

So he went on-line again and after some vague apology for “being busy” – his first attempt had said “tied up” but that brought back his friends’ warnings so he deleted it – he said coffee would be nice.

Within the hour she was back, hinting without actually saying that she knew what he meant when he said “busy” and apologising if she had been too forward, this was all new to her too. That blew his mind for a while but then he realised he was smiling. He liked this woman and her honesty. So they made a date.

They met at a diner on the highway midway between them. And when he first saw her all the admonitions of his friends came pouring back. The curly blond hair of the photo was gone, replaced by a quite severely cropped mousy brown with a streak of grey over her right temple. The face was still nice but clearly careworn, the white floaty dress replaced by a heavy, buttoned-up cotton shirt and lived-in jeans. Below them were a pair of beaten-up Doc Martens. He thought, “Oh well, the boys will love this story.” And then “Well I am here now, let’s get this over with.” It was then that he met her eyes. They hadn’t changed a bit.

At first he was tongue-tied. Something from all the TV and films he’d seen was telling him it was his job to take the lead and be charming but every time he thought of something to say, he looked up and saw, not his blonde ideal, but this frankly rather ordinary-looking woman. And yet, those eyes. They lit up everything, they fixed him and seemed to be daring him, “Just look past my face and into me. See me for who I really am.”

She could see that he was struggling. Suddenly, she came out with, “Look, it’s okay. I know. I understand. You’re thinking ‘I came here for Monroe and I got this fusty old librarian’, right? I get the same every time I look in the mirror. I think, ‘Where did she go, that woman?’ It’s okay. You don’t have to pretend.” It was said without a trace of self-pity, just with great understanding. She was giving him permission to be straight and he found himself talking.

“It’s not that. No really. Well, perhaps a bit. You know, I had this picture… your photograph. And yes, I am struggling. Was that you? In the picture? Why did you choose that photo?”

She laughed then, and to him it was like beautiful bells ringing out, “Oh, that? That was my sister, Bobby. She chose it. Goodness, where did she find that photo? That must have been ten years ago, before…” and with that she trailed off into silence, too much said too soon. He was waiting for her to go on but she seemed stuck, lost in thought, so he offered her a cue. “Before?” She sighed, “Well I suppose I’ll have to tell you now.”

“Before this thing hit me, I was having a great time. I was at college and partying, having fun almost every day. That photo was at a fancy dress party. I remember. I was into Marilyn then. No, not in a lesbian way – not that I’m against that kind of thing – I’d just finished reading a biography. About her.” Now it seemed like she was not so much telling him as just thinking aloud. “About how she changed everything about her because she just wanted to be loved and how, instead, she ended up making so many guys she never even knew, sad guys, lonely guys, feel like she loved them. And yet she was so sad inside. It was like a tribute to her. Did you know I was named for her? Norma Jean? You know her hair was originally the same colour as mine? And she was just this rather plain little girl who men had preyed on since she was a child. Anyway, soon after that party I started to get these headaches. Really bad. The worst. So I went to see the doctor and they …” And suddenly she was looking down and her tone became flatter. “… they found this tumour. In my head. Brain tumour.”

She paused. The sudden silence seemed like a damp, dark cloak around them. He wanted to speak, to push it away but no words would come. Then she began again, picking her words as though they were dangerously hot and fresh.

“I was still in my twenties, for God’s sake. I thought this only happened to older people. It threw me. Thank God I had Bobby to support me. Bobby’s always taken care of me. The dating app was her idea. She did it, I think, because I had just shrunk into myself. After the illness, then Sam… not a nice man. Classic gaslighter but after the op I was too desperate to see it until she took me away for a long walk in the hills and it all became clear, why I was feeling so bad all the time. Why I couldn’t get better. The best sister ever.”

She lifted her face again and he saw it was wet with tears. But the eyes were not pleading, they were fierce, combative. It was almost as if she was silently challenging him now to stay or go. He knew he could not move. He was overwhelmed by a feeling he had never felt for another human being. He felt now like he wanted never to go.

“Anyway, after the op, it was chemo and radiation, and my hair fell out and my skin got old and … here I am.” She shrugged a little self-deprecating shrug that seemed to say “So?” and suddenly her face was bright again and, damn the photo, he could see how beautiful she was. He wondered what her age really was but felt it was too rude to ask outright. “But you’re okay now?” It sounded so banal. “So … how much was true? … O-of the bio?”

“Oh you mean how old am I actually? No, it’s okay. It’s understandable. Look, don’t be fooled by these wrinkles. I am in fact 35. It’s been a tough few years.” And again she said it without a hint of self-pity and again he was struck by how easy she made him feel.

“Technically, I’m told the term is ‘in remission’. Nine years and counting. Well, that’s me, out on the slab. Now it’s your turn.”

It all seemed so comfortable and under her gentle guidance he found himself telling her that there had been someone, once, a few years back and he’d thought this was it but then without warning she had gone off with someone else, a salesman from New York they’d met at a works do. Something about the way he told it gave her the sense that he had never quite got over it. She had sighed then, not a sigh of boredom but of empathy, and then she had reached out and softly brushed his hand. It felt as he imagined an angel’s kiss would feel.

After that they had just talked and talked, like old friends meeting up and catching up after too long apart. As he called for the check and she immediately put her card next to his in the saucer, he realised that it had indeed been a long, long time, if ever, since he had felt so comfortable with anyone. And the next words seemed to choose themselves.

“I’m not much of a fancy speaker but this much I know. I came here looking for Marilyn, yes. But – and I know this is as strange to me as it must be to you – I think I have found something so much better.” And any remaining tension seemed to vanish, from her face and then her shoulders, and she looked up at him again. “You are a good listener, you know. Women don’t expect that of a man.”

“Let’s do this again. Shall we?” “Yes, please. I’d like that. Very much.”

All the way back home he wished he had kissed her. If he had only dared to think it, she was wishing the same.

Over the next few months they met most weeks. The diner became a regular haunt. And each time it was like picking up where they had left off before.

One evening, after a long, meandering and happy conversation they were saying their goodbyes in the car park and he found himself stammering, “Y-you know, it’s not like with Sam. I will a-always be here for you? I-if you want?” And at the mention of that name he wished he could bite out his tongue but she just quietly nodded then, turning her head slightly away from him, breaking their gaze, and said, quietly, “And I for you.”

Then she reached up and kissed his cheek, lightly. And he felt dizzy and light-headed. And in the next moment their lips met.

More time passed and then he was about to suggest they met in that old diner when she said there was no need. For a moment, he felt a sickening feeling inside. This was it. She was dumping him. He always knew it was too good to last. But then she explained. A job had come up in the library of his own town and, well, she’d applied for it and they’d said yes. So they’d be in the same place, sort of. She hoped he didn’t mind. Didn’t find that at all threatening?

It blew him away for a moment, the idea of his two worlds suddenly colliding but at the same time he knew he wanted this a lot. “But where will you stay, I mean, have you fixed yourself up?”

“Oh, I think I’ve found myself a little studio apartment to rent while I sell up. I don’t want to get in your way.”

“You don’t have to… ,” Oh, God, was this a step too far? “I mean, my house isn’t grand but I have a spare room. You could … have that. I mean, I wouldn’t… you’d be safe. Totally. Sorry, is this too much?”

She laughed and immediately the awkwardness fell away.

“I mean, if you are serious? I really don’t want to get in your way.”

“No, no, I’d like that. I’d appreciate the company. Really.” He could feel his heart beating fast and his face going red.

“I have a cat, you know.”

“I can do cats.”

“Okay, if you’re sure. But if it gets too much just kick me out, okay?”

And so it was decided.

The first few weeks were difficult. Not that they fought or tripped over each other. More that they tiptoed around each other in mutual discomfort and that old easiness was just not there. They didn’t kiss, didn’t touch. They were tentative, overly solicitous of each other’s space and needs. The physical distance that they so deliberately observed became like dead air between them. It was painful. It felt wrong to him and yet there was an invisible barrier that he felt sure he must not cross and she seemed to feel the same. At night they wished each other goodnight and went to their separate rooms, she taking her cat and firmly closing the door behind her. He began to think this had been a mistake, that he had ruined everything.

One night, it was a Friday, it was her turn to choose a film. She chose “Sleepless in Seattle.” He was a great Tom Hanks fan. The man exuded decency and class in everything he did. But that Meg Ryan, constantly trying to steal attention with her cutesy twitches, arch mannerisms and weird deliveries. Jean could see that he didn’t really want to but he insisted that he was okay with that and they sat in silence through it, he in his chair, she curled up on the sofa, and, to his surprise, at the end he had tears on his face, which he tried to hide by blowing his nose. Which of course only made it more obvious. And she laughed, “That Meg Ryan, eh? What a piece!” and it was not a cruel laugh but one that broke the tension, and he joined in.

As they cleared the dishes, she came close to him and said, “I was wondering. Could I sleep with you tonight? Would that be all right?”

For a moment he was silent, taking in what he had heard and she started to back track, “No, of course … stupid suggestion … sorry … forget…”

“No, no. I’d like that. Really.

“Sure? We don’t have to, you know, do anything. Just be close.”

And that is how it was for several nights. Just them holding each other and falling into comfortable sleep with the warmth of each other’s body reminding them of how good it could be just being next to someone you love and trust.

It changed everything, though. Now they were at ease again. The conversations became natural, the spaces stopped being his and hers and became theirs. It felt right.

It was some time before they made love and when they did it was not like the films. It had been a long time since he had been intimate with anyone. He felt clumsy but was gentle, wanting somehow to let her know without words how much he loved her, wanting it to be for, and all about, her. Afterwards, he felt awkward and worried about whether he had got it right, but she just looked up at him with a smile that said, as eloquently as any words could have, that it had been fine and that he had made her very happy. From then on, whenever they made love it was just that, making love.

John had been used to dropping by the bar most nights before he met Jean but since she moved in, without ever consciously choosing, he had known that when the day’s work finished what he most wanted was to get home to her. One night she said, “You never seem to see your friends any more.”

His first thought was, “She’s bored with me. She wants me out from under.” But it was as if she was reading him. “I’ve not met these people and I’d like to. After all, they brought us together in a way. They must be nice people to care about you so much. Maybe we could go to the bar. Maybe we could meet there one evening after work. Do you think?”

So they arranged to meet at the bar the next Friday. He made sure he got there first so that she wasn’t hanging around feeling embarrassed. Truth to tell he was a bit worried about how it would go. His buddies were decent enough but they could be a bit … well a bit chauvinist, he supposed. He hadn’t really thought about it before but there had been times when the banter had made him cringe a bit inside.

He needn’t have worried. When she walked through the door, in her neat grey work suit, she lit up the room. Old Nick, always playing the curmudgeon but really soft as butter, tried to come on surly, “Well, it’s my round. What’s it to be, young lady. I s’pose you’ll be wanting one of them fancy cocktails, cost a fortune.” But Jean just looked him in the eye, smiled her best smile and replied, “No, I think I’ll have what you’re having if that’s okay. Bud, right?”

Nick’s jaw dropped a little then he cleared his throat and said to John, “Fine woman you got yourself, there, John. She’s all right.”

From then on it was a great evening. He could feel the men opening up and, as he watched them vying with each other for her attention, he was reminded of Marilyn Monroe’s effect on the males she encountered. A couple of times one or other of the men said something a bit challenging but Jean always had an easy response that made everyone, even the speaker, laugh. She was a hit.

He felt stupidly proud as they walked home, much later than he had intended, and she took his arm and laughed and they went light-heartedly over some of the things that had happened and been said. It became a regular Friday night thing, and movie night switched to Saturday.

John had worked in the same insurers’ office since leaving college. He had given up counting the years, given up seeking advancement, given up on thinking about moving on. And now, with Jean, he felt more settled than ever. Just occasionally, he would find the thought surfacing “What if this doesn’t last?” but he mostly managed to banish it. Coming home to her after another dull day was, he found, a good way of forgetting.

Then, one day, his supervisor called him into his office. The supervisor was not a bad boss. He expected competence and diligence but as long as you delivered on them regularly, he was pretty relaxed. So when John entered the room he was slightly unnerved to find his boss agitated, something clearly on his mind.

“John, I’m not gonna beat about the bush. The company’s gonna have to let you go. I’m sorry.”

For a moment, John was too stunned to respond. Then he asked, in a tone more pleading than challenging, “Why, Bart? Are they unhappy with me? Have I not been up to the mark…? Why me, why now?”

Bart leaned forward over his desk in a way he hoped would appear avuncular and conciliatory, “No, John. Your work’s fine. It’s the economy, John. Downturns, prices up, people making what savings they can. Everywhere. The company sees its margins disappearing. It needs to cut back, consolidate, if you like. I’m sorry but there it is.”

John thought ‘So you’re getting rid of me to save your necks’. But he didn’t say it, just bowed his head and tried to keep the host of unanswerable questions that had suddenly appeared in his mind from taking over. He heard Bart’s chair creak as he sat back and said, “Of course, there’ll be a package and we can give you four weeks’ notice, starting today. You can take it as leave. Sorry, John, but there it is.” And with that, Bart stood up and extended his hand across the desk. Instinctively, John stood too and took the hand, mumbled “Sorry”, though he could not for the life of him think why, then turned and left.

Back at his own workstation, he avoided the questioning looks of his younger colleagues, gathered his few personal possessions, signed out of his computer, placed his office keys and badge in the middle of the desk and left.

Walking home, the same route he had taken five days out of seven all those years, he passed the entrance to the bar then, on an impulse, went back and through the door. The barman looked up and said “Well, hi, John. You’re early. Half day? Bud?”

John said no, he’d have a large bourbon on the rocks. The barman flinched slightly but did as he was asked and John perched on a stool at the empty bar and started to fret about what he would tell Jean.

He need not have worried. When he came into the kitchen, several hours and bourbons later, she saw a man miserable and struggling with something hurtful and went straight to him and held him close, unspeaking, for what seemed a long time. He felt her warmth and felt himself start to unwind.

“What is it, John? Whatever it is, tell me. We’ll get past it. I promise.”

And so he told her. “They sacked me, Jean. After all these years, after all my work, they sacked me, no discussion, just ‘So long, John’” It seemed strange to him to hear his own name coming out of his mouth.

Jean didn’t waste time on recriminations. She just shifted slightly then looked up at his face, forcing him to focus on hers, “We’ll get through this. Don’t fret, darling. We’ll get by.” And then, releasing him and making a show of busying herself around the kitchen, she said, “You go and get yourself into the shower and change into something comfortable. Dinner’s in about half an hour.”

And he did as she said. The shower eased everything and he had time to think, not for the first time, what a wonderful blessing this woman was, and how – yes, how lucky he was – to have found her.

Turned out they weren’t in such bad position financially. He owned the house outright and the car, which wasn’t new but it would serve for some time. He’d kept it well. And there was her income and their savings to supplement the feeble financial package he got from work.

After a couple of weeks, which Jean insisted he took to let things settle, he started to think about what he wanted to do. He realised he had had enough of offices and insurance. He’d always been interested in cars since he was a kid, had done his own servicing on the car, and when a job came up as a mechanic at a local garage, he applied and persuaded them to try him out. It sure was different from the desk job he’d been used to but after a while he realised that for the first time in his adult life he was happy, more than happy. Content.

And so it went on. It turned out they couldn’t have kids. The combination of the chemo and the medications had taken an irrevocable toll on Jean’s reproductive system bringing an early onset of the menopause. When she broke the news to him, he had said to her that it was okay, which it was. He had in fact felt slightly ashamed at the wave of relief that had come over him with the news. Jean just gave him that look again, the one that said “I know what you are feeling but that’s fine.” And he just loved her more. They got another cat “to keep Jackson company” and poured their affection into both of them. The next ten years passed easily and though they never wed, everyone saw them as a happy, settled couple.

He got home from work one evening, tired and dusty and longing for the steaming relief of a shower followed by a cold beer. But immediately the unnatural stillness of the house off-balanced him. He called out, “Jean?” and walked through the house in search of her. He found her in the kitchen, bent over a saucepan on the hob in an unusually deliberate way. He couldn’t see her face but it was as if a stifling cloud of sadness had filled the house and that she was its source.

Again, he called her name, but this time in a hushed reverence. She flinched slightly but did not look up. This spooked him. He tried again, “Jean, love, what’s wrong?” And watched as a tear dropped off her chin and into the pan. Before he could think again, he crossed the kitchen floor and took hold of her shoulders pulling himself close to her back. She was quivering, as he had seen Jackson do before the rat poison it had accidentally ingested ripped the last shreds of its life away. “What is it, Jean? Tell me, … please.”

She turned round quickly and buried her face in his filthy shirt. She was clearly crying pitifully now. He found it was hurting his heart like nothing he’d ever felt before. Eventually she found enough control to speak.

“It’s back.”

She didn’t need to say any more but she did. “The tumour … the cancer … it’s back.”

He made her put down the spoon she had been using, turned off the gas and guided her to the sofa, where they both sat down. He held both her hands in silence then said, quietly but firmly, “Tell me. What does this mean.”

She took a deep breath and, looking steadily at her lap, laid it out as plainly as she could. “I’d started having those headaches again. I thought I’d better get it checked out. They did a CT scan. There’s a lump, just like before but it is growing. I don’t know if they can do anything this time.”

He wanted to ask “Why didn’t you tell me? How long have you known?” But these questions seemed so accusatory.

Then she looked him in the face, “Oh, John, I’m so sorry.”

For a moment these words shocked him. “Hey, you don’t say sorry to me. You haven’t done anything wrong.” He remembered how strong she had been for him, remembered her words all those years ago and said, “We’ll get through this. We’ll fight this together. We can beat this.”

And for the next few months that’s what they did. She still had her job and her health insurance and they went to all the appointments together, held each other’s hands, pressed for answers. But the answers were always the same. “It’s aggressive.” “All we can do is slow it down.” “Palliative care.” Then John found himself asking the big question. Jean had left the room briefly. “How long has she got?” And the answer came with cruel clarity. “Six months if she’s lucky. But it will get worse before then.”

As they drove home, Jean in the front passenger seat, John concentrating fiercely on the road, she broke the silence without even turning her head. “So what did he say? How long?” She still had that power to read him. For a moment he couldn’t speak, his throat seemed too full of grief. Then he said, quietly, as if he hoped the words wouldn’t reach her. “Six months.”

“Oh, that won’t do.” It sounded scolding, as if fate was just some naughty child to be made to do better. Then she looked at him. “I’m not done yet, darling.”

As if she had convinced herself, Jean discovered new levels of energy. He could almost believe at times that it had all been a bad dream, the diagnosis. She took leave and repainted the house, hung new drapes, cooked batch meals for the freezer. They went shopping and she made him buy clothes he didn’t need. And they went places, driving hundreds of miles to get to remote forests and the coast. And the six months came and went and she was still smiling and laughing and making him happy just by being there.

But one morning, when he brought her the cup of green tea and ginger that had become her favourite, she had trouble sitting up, didn’t take the cup and held her head in her hands. Her colour was pale and when she looked up there was unmistakeable fear in her eyes. He said simply, “I’ll call the doctor.”

The doctor confirmed that things had moved on. In his somewhat callous words, “We’ve reached the endgame.” He brought in a nurse who efficiently shot drugs into her veins and installed monitors and other paraphernalia as if to confirm Jean’s new status as “patient”. And from that time, Jean only left her bed to totter, accompanied, to the bathroom and back.

John did his best. He cooked for her, even though she hardly ate. He washed her like she was the most precious china doll. He sat with her and read to her while she could stand it. And when she closed her eyes to sleep he looked down on that still beautiful face trying not to see how it, and she, was shrinking, fading, retreating from the world. There were times, many times, when he left her sleeping to sit in his armchair and weep uncontrollably. But in her presence he resolved to remain steadfast.

It was as if she could not let herself die. The pain grew and grew and eventually the doctor set up what he called a morphine driver to control it. He took John aside and instructed him earnestly that if the pain grew too great he was to turn the dial on the little pump up, but just by a little. If she got too much morphine, she would fall asleep and die. John listened avidly and took his new task to heart. If he realised the power that had been placed in his hands, the power to end her suffering for good, he ignored it. In his mind somewhere there lurked the foolish thought that there was some way back from this, that one morning she would wake up cured. Not to have that thought would be unbearable.

One afternoon, he was sitting in the chair he had placed alongside what had once been their bed. He was watching her sleep, thinking how peaceful she looked. She could no longer talk much when she was briefly awake, hadn’t left the bed for weeks, fed only by a drip from a bag. As he watched, her eyes opened and she looked at him. He thought he saw once more in them that embracing love that had so captivated him from the start. Then she spoke.

“I promised you I would always be there.” Her voice was barely audible but surprisingly firm. She had turned her face enough to look directly into his. Her eyes were moist and seemed now to convey an overwhelming sense of sadness. A tidal wave of pity rose through him for this poor, defeated woman, his love. He wanted to burst into tears but knew he must not. “Oh don’t you worry about that. I’ll be fine. You just…” And suddenly he knew what he had to say. “We’re fine. You have done all you can … done enough … more than enough. Thank you, my darling, thank you. Peace now. I love you. I will always love you.”

And, as if she now had the permission she had needed, she closed her eyes, turned her head back and with one last long breath, relaxed into the pillow. He noticed the faintest of smiles on her mouth. He saw that her small, frail chest was no longer rising and falling. A new depth of silence seemed to command the room.

He sat there for maybe five minutes, maybe longer, just watching her face, trying to take in that she was gone, holding on to her in his head. Then he gently prised his hand free from hers and, rising from his chair, turned down the morphine driver and removed the needle from her arm. As he did so he was struck by how clinically he was acting, like this was just another part of the job. But all the time a part of his brain was fighting to stave off the devastating emptiness that he was feeling. Was this how “heartbroken” felt?

He sat back down, heavily in the chair, and for a moment allowed the emptiness to take him over. Then, taking an anaesthetic swab from the packet on the bedside table, he rolled up his left sleeve and rubbed it against the skin of his inner arm. For a moment he paused. He had never liked needles. It had been his standing joke with nurses, “I could never be a drug addict.” They had all smiled dutifully. But now he nodded to himself as if to confirm what must now be done and, taking up again that needle attached to the long clear tube that linked it to the driver he found a vein and, gritting his teeth, pushed the needle through his leathery skin into it. A small teardrop of dull blood appeared around the needle as he fixed it in place with some medical tape, just as he had seen the doctor do with Jean. That done, he reached over with his right arm to the dial of the machine and turned it up to its highest setting.

Then he took her hand again, already colder than when he had removed his own, and, turning his head for the last time to look at her face, settled back in his chair.

0 notes

Text

Tate and Lying

Let me say at the outset that I have not visited any of Andrew Tate’s websites or listened to any podcasts in which he has featured and I have not followed, or even read, him on social media. All I know about him is the views attributed to him by others, mostly journalists and commentators, which, experience has taught me, is not always the most reliable way to find out about a man.

In my general defence, this is not often the case. For example, my loathing of Donald Trump, his egregious family, the toad Vance, Elon Musk, Nigel Farage, Lee Anderson, Liz Truss and Kemi Badenoch, to name but a few, has come almost exclusively from reading and listening to and watching them. In short, each of them is directly responsible for the profound contempt in which I hold them.

But because I cannot say the same for Andrew Tate, I must tread carefully. He may have been misquoted, misrepresented and wrongly accused. That last one is certainly something he asserts, much as Trump claims that he is the victim of a witch-hunt and Nigel Farage claims he is not a money-grubbing racist but a real politician.

So what is it that has been suggested about Andrew?

Well, to begin with, and in essence, that he is a rather pathetic grifter with profoundly toxic misogynistic views about women. Let’s take some examples.

He appeared on Big Brother (not in itself a crime, except against good taste) where he only lasted six days on the programme, before being removed following the emergence of a video that appeared to show him attacking a woman with a belt then telling her to count the bruises. He denies this.

He has said, publicly, that he is "absolutely a misogynist", and added: "I'm a realist and when you're a realist, you're sexist. There's no way you can be rooted in reality and not be sexist."

He has said women are "intrinsically lazy" and said there was "no such thing as an independent female".

He has said, on “X”, women should "bear responsibility" for being sexually assaulted.

He has been accused of believing that women, free of control, will undermine men and that it is men’s duty to force them into obedience to their will, with particular reference to sexual coercion.

He is alleged to have sent a text to a woman saying "I love raping you".

He has been recorded as saying “It’s bang out the machete, boom in her face and grip her by the neck. Shut up bitch,”

Now I should put this much on the record. I don’t so much mind if Andrew Tate actually holds these views. That is not to say that I approve of them in any degree. I think they are pathetic, vile and worthless, the utterances of a total loser. It may be that he has become a wealthy loser but then so did Trump and Al Capone and Bashir Assad. They are still views that any sane and well-balanced man would be ashamed of. And if Andrew Tate actually holds them I think he needs to volunteer for a fairly intensive re-education.

What I object to is that he should see fit to make those views public, and indeed to make them the core of his business model. I don’t say that he is not entitled to do so. Freedom of expression, one of those “woke” concepts that make up “human rights” entails allowing individuals to espouse the most pernicious of false ideas. But, contrary to popular belief, freedom of speech is not absolute. It is hedged around by caveats about taking responsibility and the need to accept the consequences of what you say. It is a matter of choice, grown-up choice. And I don’t think Andrew Tate understands that.

I think that if Andrew Tate was a decent, kind and considerate man, which, after all, should be what every man, even someone as pathetic as Andrew Tate, should strive to be, and what any real man is, he would be looking at the impact of what he is reported as having expressed, realising the colossal and irreparable damage that those views are doing to vulnerable people – young men and boys in particular – and would be distancing himself from them in the most public way he could. Because whatever he personally feels, the fact is that when they are peddled to people, young people, who do not have the skills or experience to challenge them and who may well be going through emotional crises of their own, they become powerful propaganda for bad behaviour. It is actually in his own interest to disavow them, because they will lead, inexorably, to the antithesis of the society that Tate himself depends on for the continuance of his apparently depraved lifestyle. Selfishness of the scale that Andrew appears to take as his right requires a bedrock of conformity and selflessness in others. A paradox but still true.

Let me set the assertion I have just made in a very personal context. I am 73. I was brought up in the fifties by strong women pretending to be weak to fulfil the needs of their weak husbands to appear strong. I grew up sexually repressed because I loved my mother and wanted to honour what she told me about the insatiable desires of men and how they were ugly and wrong. As a consequence, I failed to have a girlfriend throughout my teens and did not even have the courage to kiss a woman until I was thirty-two. It was not a pleasant or fun time for me. I felt a failure. If I had had Andrew Tate’s alleged pronouncements ringing in my ears, I have no doubt that, while remaining a profoundly inadequate and unhappy teen, I would have espoused a toxic and predatory attitude to women which would have prevented any mutually respectful relationships from ever forming and would probably have ended up with my being a sad and lonely sexual abuser who had nothing to offer the world but pathetic rages of victimhood against women and society in general. Instead, I worked on what I saw was my problem, opened myself up to learning from others, eventually married, and fathered two splendid children of whom I am enormously proud. And because of that I will die a happy man having never knowingly hurt anyone. That may appear a very narrow ambition to Andrew, who seems to think that his worth can be measured in dressing badly, poor hygiene, bad manners, nurtured hatred and driving around in stupidly expensive cars. But it seems to me like a life well-lived.

You would think that Andrew Tate would, above all, respect the “manly” attributes of respect and discipline, and from them a family life lived well. Instead, it appears, he wants to poison the minds of children against their parents, women and their culture to enable him to live a life of empty, toxic hedonism as some perverted kind of anti-hero. He must have had a very sad childhood, but therapy can help with that. What is inexcusable is the passing on of brutality and prejudice and malevolence. Especially when it is only done to make a fast buck out of some unfortunate child. Yet it would appear that that is precisely what he is doing.

Of course, it may just be that all these reporters and commentators are lying about what Andrew Tate has actually said and written. Or it may be that Andrew Tate is lying about what he believes. In a way it doesn’t really matter which is true. What matters is the harm that parading views like these before impressionable kids can do, and is doing.

So, just in case it is true, my message to Andrew Tate would be, to borrow his own words, “Dear Andrew, just shut up, bitch.” You are not helping. You are just embarrassing all of us.”

0 notes

Text

As light as air

Remember that one time we kissed?

Victoria Station late at night?

We’d sat all evening drinking wine

In a bar not far from there.

Ten years had passed since our last tryst

No, more than ten, a long respite,

With me too scared to cross the line

And consummate our love affair.

For far too long I’d wanted this

And now I asked you if I might

Expecting that you would decline

But you said yes, and in a blur

I bent my head and kissed your lips

My tongue touched yours, my heart took flight.

I held you close, it felt divine.

Two lovers in the streetlamp’s glare.

We drew apart, my vision misty,

Brain abuzz, my breathing tight.

I tried to speak, my mouth declined

Still savouring the spark we’d shared.

But, reeling from our virgin kiss,

I fought to make my words come right

And fumbled some appalling line

How good you felt, how fine, how fair!

I see again your sparkling eyes,

The pleasure in those words so trite

And as we stood, some tattered wino

Bowling up our joy to share

Bestowed his blessing on our bliss.

A celebrant, a holy knight,

He seemed the moment to define,

In drunken, slurring, happy prayer.

We left him there, said our goodbyes,

And on the journey home my heart

Began its terrible decline

Remorse gushed in, too strong to bear.

So, with the day, that longed-for kiss

Transformed into a poisoned bite

And you, my lovely Caroline,

My Eve, I just abandoned there.

Now I am old and memories

Are riven by this coward’s sleight

I should have fought to make you mine

But truth to tell I did not dare.

Is it too late? Some hope persists

My present emptiness to spite

But to my fate I am resigned

And doubts infest me with despair

Remember, d’you remember this

Or did I dream that blissful night

Our first embrace, our tongues entwined

You in my arms as light as air

0 notes

Text

For Jeremy, rest in peace

Jeremy was that rare thing, a good man. I came to know him at the Old Cross Tavern where, for a while, he brewed beer so good that when it was on I preferred it to all the others on the pumps. But that was it with Jeremy. After his first run in with cancer he had given up banking to become a gardener and even the flowers and bushes seemed to make an extra effort to be glorious under his careful nurture.

Jeremy managed to be kind, gentle and fun. It seemed effortless but it was never absent. I relished his conversation every time he came into the pub, sometimes bringing with him his daughter Amy who, like her Dad, radiated kindness.

Sadly, after a respite of 17 years, cancer came back to claim Jeremy and yesterday I joined 150 others for his funeral. There was so much love for him at that ceremony.

Two days before, I woke in the middle of the night and could not rest until I had written this. A poor epitaph to a lovely man. Rest in peace, Jeremy.

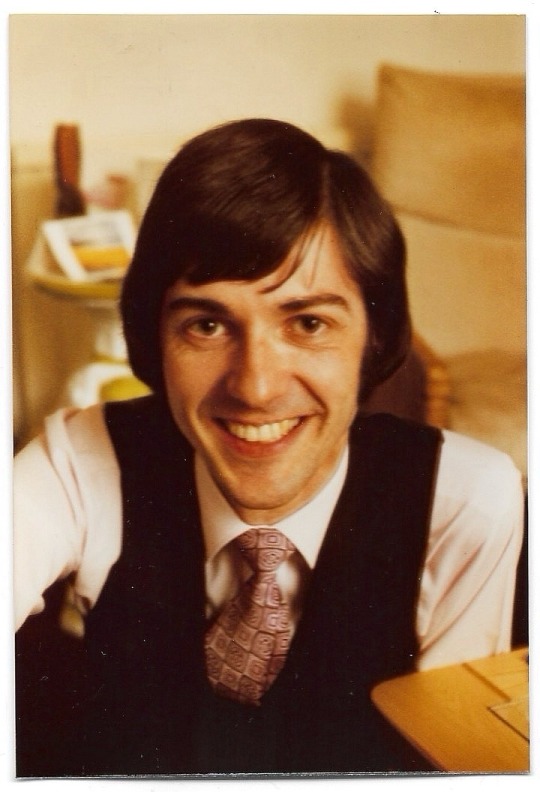

Photo courtesy of South Herts CAMRA

Just as we thought the Winter ended,

Endless night now dawning day

Returning hopes of life suspended,

Every bud a promise made,

Making every garden splendid,

Your kind, noble heart gave way

But, as each snowdrop breaks the soil

And arches up to drink the air, we

Relicts will recall your toil

To bring us joy and ease our care. The

Love in which you gently coiled

Each heavy heart. And, with it, dare we

To remember how you foiled

The dark to show what light there be.

0 notes

Text

Americans, are you feeling guilty yet?

Because you should be. It is a basic courtesy, recognised all over the civilised, and not so civilised, world that when you invite someone into your house you treat him with respect and hospitality.

I suppose that different rules may apply to hoodlums like that narcissistic, felonious fraud that you chose to elect to your highest office, or, perhaps more likely, that such hoodlums think they do, but the world expects a president to act presidentially, and so should you.

This orange buffoon who would be King of the World and his Mini-Me sidekick Vance are people whose idea of “making a deal” means only bullying decent folk and capitulating to bigger bullies. They clearly consider that there is only one acceptable question that can follow the direction “Bow before my might”, and that is “How low should I bow?”

Outside their trumped-up world of lies, these mobsters have no credibility. They are just mouthy delinquents. Their braying is just an unfunny joke told in a sleazy bar to a bunch of drunk hangers-on. But they speak in your name, America. And they do so because you put them there. Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?

These things the rest of the world knows to be true:

· Ukraine is a sovereign country;

· Zelensky is the elected leader of that country;

· Russia, specifically Putin, is the aggressor. It started the war;

· In Europe, we have freedom of expression and democracy;

· In the US, you only have freedom of the oligarchs and money;

· Your so-called President is a convicted felon, a philanderer and a bully;

· Your claim to be a Christian nation cannot stand alongside his elevation.

It’s your choice how long you live with being ruled by a third rate gangster and his mob of over-privileged pirates pretending to royalty like latter-day, kiss the ring, Mafia Dons. But don’t expect the world to bend its knee to his tyrannical, and yet fatuous, strutting.

Time to grow up, America. Time to honour your forebears. Time to call time on the man-baby. Time to rejoin the human race. Time is running out.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry