My name is June and I like to write book reviews! Currently reposting 2020-21 from goodreads. Blog will officially launch in Jan 2022.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac

by Mary Oliver

1. Why should I have been surprised? Hunters walk the forest without a sound. The hunter, strapped to his rifle, the fox on his feet of silk, the serpent on his empire of muscles— all move in a stillness, hungry, careful, intent. Just as the cancer entered the forest of my body, without a sound.

2. The question is, what will it be like after the last day? Will I float into the sky or will I fray within the earth or a river— remembering nothing? How desperate I would be if I couldn’t remember the sun rising, if I couldn’t remember trees, rivers; if I couldn’t even remember, beloved, your beloved name.

3. I know, you never intended to be in this world. But you’re in it all the same.

so why not get started immediately.

I mean, belonging to it. There is so much to admire, to weep over.

And to write music or poems about.

Bless the feet that take you to and fro. Bless the eyes and the listening ears. Bless the tongue, the marvel of taste. Bless touching.

You could live a hundred years, it’s happened. Or not. I am speaking from the fortunate platform of many years, none of which, I think, I ever wasted. Do you need a prod? Do you need a little darkness to get you going? Let me be urgent as a knife, then, and remind you of Keats, so single of purpose and thinking, for a while, he had a lifetime.

4. Late yesterday afternoon, in the heat, all the fragile blue flowers in bloom in the shrubs in the yard next door had tumbled from the shrubs and lay wrinkled and fading in the grass. But this morning the shrubs were full of the blue flowers again. There wasn’t a single one on the grass. How, I wondered, did they roll back up to the branches, that fiercely wanting, as we all do, just a little more of life?

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle by C. G. Jung - 4/5

I’ve been experiencing a lot of synchronicities lately, and though I had not read Jung before this, I knew the bare minimum to recognize them for what they are. But what do they mean? This is what I was hoping to find out by going to the source of where the term was coined, and though this treatise was interesting, I didn’t really find any answers. Carl Jung coined the term synchronicity to describe “meaningful coincidences” defined in opposition to causal events. The first half of the book was an argument that modern science cannot explain everything in the universe — I tend to agree, but ascribe inexplicable phenomena as a result of nature’s complexity; chaos theory predates Jung but I’m not sure how deeply he actually addresses it. In any case, much of the book is devoted to “proving” synchronicity exists, which is not something I personally felt I needed proven to me, but perhaps it’s of interest to the skeptic. Jung’s “case study” by which he attempts to empirically prove the existence of synchronicity is a statistical analysis of astrological compatibility in married couples. I felt this approach was counterproductive because, though I have a healthy belief in astrology and divination, I don’t look for empirical proof of it existing. I believe these are most useful for inspiration and finding new thought pathways, not predictive tools, so I feel that this study was misguided, flawed methodology aside. The same goes for his inclusion of Rhine’s parapsychological ESP experiments. Most of the book was devoted to describing the phenomenon of synchronicity, without answering what these “meaningful coincidences” might actually mean, and without any real psychoanalytical application of the principle.

0 notes

Text

The Glimpses of the Moon by Edith Wharton - 4/5

I have said before that while I find Wharton’s style exceedingly hard to read for some reason, I nonetheless find myself drawn into her stories. Glimpses of the Moon is no exception with regards to the style, but despite being a lesser-known work, it is by far my favorite of her novels. It tells the story of two social climbers in 1920s New York (who might be described as “influencers” today) who enter a sham marriage to reap the benefits of honeymooning indefinitely at their rich friends’ vacation homes. After a minor disagreement they entertain divorce, and what’s so fascinating about the novel is that it is a romance between two people who spend almost the entire novel apart. One could only imagine what Glimpses of the Moon would look like set in the present day, because the yearning over long-distance is all too familiar. It’s much less heavy than The Age of Innocence or House of Mirth (one might even describe it as a rom-com) but retains the same social critique under all the levity.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Universe in Verse ed. Maria Popova - 4/5

I have often complained about contemporary poetry being inaccessible, or failing at outreach by only speaking to other poets. This slim collection targets a different audience: scientists. The parallels between science and art are obvious but oft-ignored, and in The Universe in Verse, Maria Popova presents fifteen moments in the history of scientific thought paired with fifteen poems. Ten of these are within the realms of physics, math, and astronomy which makes the few about biology seem a bit out of place — perhaps the collection would have been more concise with a narrower focus. But the poems selected are all gorgeous and easy to follow, and the accompanying essays are little works of poetry in themselves. Though every page features elegant drawings, the book’s style is in no way a mask for lack of substance.

0 notes

Text

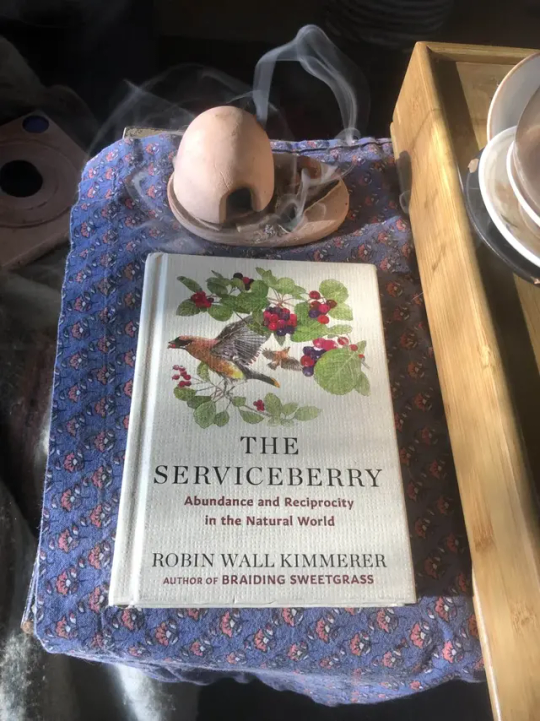

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer - 5/5

Firstly, if you’re going to publish a book this tiny, there had better be pictures in it. And this did not disappoint.

Like many others, I read and loved Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s preceding collection of essays. But after it exploded in popularity, I noticed this phenomenon of hippie types who read Braiding Sweetgrass once taking away only a surface level interpretation, as is wont to happen with any book so frequently gifted. These are the same people who don’t understand what I mean when I tell them Braiding Sweetgrass is a work of political theory. The crux of that book is the gift economy, or the idea that the same principle of reciprocity can be applied not only to the ecology but also to our socioeconomic system. But I don’t think people fully understood this. The most egregious example, in my city, where everyone is trying to sell you something, was an acquaintance offering an apprenticeship in herbal medicine and saying that it was a reciprocal relationship that required an “energy exchange” of a thousand dollars. By using the language without internalizing the principles, these (mostly white) people are doing little more than rehashing the “noble savage” myth.

So I can understand why Kimmerer would want to clear things up. The Serviceberry is a tiny book, published right before Christmas with a cover illustration of red berries, so it’s almost expected that it would be sold as a generic stocking stuffer. It would have been very easy for her to completely phone it in (and to be fair, the hundred pages of large font size are just a reprinted magazine essay). Instead, The Serviceberry expands on one of the most powerful essays in Braiding Sweetgrass, and delves into the political and economic theory behind the gift economy. Aside from her personal experience teaching and working the land, there isn’t much that isn’t rehashed from other thinkers (I’m currently reading Devall and Sessions’ Deep Ecology anthology which cites a lot of the same literature), but she condenses it all into something easily digestible. It’s a concise and yet staggeringly important manifesto, and even if the ideas within are fairly redundant with her other work, I am glad she put it in a more approachable package.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cry of the Kalahari by Mark and Delia Owens - 2/5

In college, I studied abroad Botswana for two months doing ecological research in the Kalahari. Before we left, we were all supposed to read this book, and for whatever reason I didn’t. Every time this happens I start feeling kind of guilty so when I found a nice vintage copy (that split down the spine right after I bought it) I decided it was time.

Cry of the Kalahari was written by married couple Mark and Delia Owens. Delia has become the more prolific of the two, authoring Where the Crawdads Sing, a novel which I know nothing about except that Taylor Swift wrote a song for the film adaptation. But before that, the Owens were biology students who moved to the Kalahari to conduct large mammal research, seemingly spontaneously. Cry of the Kalahari is an account of their seven years in Botswana.

Early on, very little separated this story from having a Grizzly Man or Chris McCandless ending. Two scrappy, untrained Americans with no external support moving out to the middle of the desert to conduct some vague notion of “research” seems intended to be charismatic, but really comes across as just sort of dumb. Towards the beginning, almost every chapter includes comically over-the-top escapades: running out of water, Land Rover catching on fire, and generally not getting any meaningful research done. As the Owens raised funds to continue the research, the writing became less sensationalistic and more about the animals, and they do write beautifully about the animals, but the first half had me shaking my head on every page. I’m not trying to claim that I would do better if in that situation, just that I wouldn’t end up in that situation in the first place, because there is a very fine line between tenacity and foolishness that the Owens continuously toed.

As I said, Cry of the Kalahari shows great love for the natural world. The Owens did meaningfully contribute to research on the life histories of lions and hyenas. The end chapter is a plea for wildebeest conservation in the face of insurmountable pressures from ranching lobbyists. But the unspoken thread that runs throughout this book is the specter of imperialism. The Owens write about the wildlife of the Kalahari with more sympathy than they hold for the locals, save for the white minority. While Botswana does not have as fraught a history as neighboring South Africa, it was not lost on me that almost every named human character the Owens come across are part of a very wealthy, segregated minority descending from either English or Dutch colonists. Sure, I almost cried when the lion they had nursed back to health was shot by European tourists, but any critical analysis of the causes of the big-game trade were lacking. And then they write about the indigenous populations as if they are savages. They pay a Tswana local fifty cents a day to be their live-in servant thousands of miles away from human settlement, then characterize him as a violent alcoholic dimwit without even bothering to learn his language. It’s appallingly chauvinist, and I know from first-hand experience that it is a common attitude amongst the white minority. Unfortunately, while the chapters on humans in Botswana were nauseating at worst and ignorant at best, the chapters on the animals were not scientifically rigorous enough to redeem this book.

Years later, Mark and Delia Owens were investigated for murder of a Zambian. Many have written thinkpieces on this incident, but all I have to say is that it does not seem out of character for them based on this book.

#Cry of the Kalahari#mark owens#delia owens#nonfiction#science#biography#autobiography#2#february 2025#2025

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lords of Chaos by Michael Moynihan and Didrik Søderlind - 3/5

First, I watched the film adaptation, which zeroes in on a crimewave connected to the early 90s black metal scene in suburban Norway, a battle of personalities between Euronymous of the band Mayhem, and his eventual killer Varg AKA Burzum AKA Lord Grishnakh. It’s comical in a Scorsesean way, think Wolf of Wall Street if it was about teenagers who think they’re more important than they are, think Amadeus if it was about musicians who aren’t very good. So I enjoyed the movie so much that I decided to read Moynihan and Søderlind’s book-length work of investigative journalism, because I found the whole microcosm fascinating in a voyeuristic way.

The book Lords of Chaos covers the Euronymous/Varg saga, but does not dwell on it. It’s a comprehensive portrait of a time and place. And because of that, it’s actually somewhat boring. Moynihan and Søderlind did not do much curation (like one of my favorite journalistic books, Blood, Sweat & Chrome did) and instead opted to print full-length interviews with musicians from the scene. I’m not moralistically opposed to “platforming” people like Varg (Nazi, racist, and murderer, though if he murdered another racist, I guess he can’t be that bad, right?) because they come across as so stupid that I can’t imagine anyone from outside their immediate sphere taking them seriously. But I found the meat of this book to be very boring, because the authors take these guys seriously enough to print the entire interviews, seemingly unedited.

Some have criticized Moynihan as being right-wing and sympathetic to the Neo-Nazis portrayed in this book. I can’t really see that — as aforementioned, I don’t think there’s an editorial duty to criticize and dissect someone who willingly makes themselves look stupid. The one thing that Moynihan and Søderlind actually excel at, though it is a comparatively meager part of this book, is cultural criticism. Many cogent analyses of Satanism, Neo-Paganism, and the Norwegian far-right movements are given, most of which boil down to bored teenagers in a sheltered middle-class suburb craving some sort of extreme reaction. Early on, Moynihan and Søderlind make an argument I have never seen anywhere else. They (rightfully) trace the lineage from blues to rock to black metal, but make the point that moralism has followed this musical genealogy since the start — the first “Satanic Panic” being at Congo Square, where slaves from Louisiana first invented jazz. I love this being a blow to the fascist worldview of someone like Varg.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dalva by Jim Harrison - 4/5

I’ve largely abandoned my fiction-reading for memoirs, journals, and other nonfiction. I have read too many books that sacrifice character for plot, and as a result, they just don’t compel me. In biography, and especially autobiography, the author is distilled into character, without the pressures of plot. So when a novel is written like a memoir, I’m interested — in the case of Dalva, the execution depends on the quality of the character.

In a way, Jim Harrison’s Dalva is a western. Much focus is given to the cultural and ecological landscape of Nebraska and its grim history during Manifest Destiny. To describe the plot of Dalva would do it a disservice — at heart, the book is simple: it is a story about its title character searching for her long-lost son. Dalva’s sections are written as a letter to her son, and the character is so convincing that I felt like I was reading a work of nonfiction. Part of this has to do with how meandering the book is — nothing much happens in the first third of the book, but it was nevertheless my favorite part, because Dalva’s voice was so interesting.

Where Harrison lost me was the middle section, concerning a man who has a fling with Dalva while researching her family history. The difference between the sections was that Michael just wasn’t an interesting, or even a believable guy to read about! He will say something really genius, like “If the Nazis had won the war the Holocaust, finally, would have been set to music, just as our victorious and bloody trek west is accompanied on film by thousands of violins and kettle drums,” and then go on and on about how down bad he is for teenagers. Just not an interesting guy to spend time in the head of! And when the character is not interesting enough, I would hope the story would be, but in this case it was not.

As hard as it is to describe what this book was about, it was certainly impressive to have crammed so many “themes” into something that feels so nebulous and natural. There’s Dalva and her half-Sioux son, and there’s the conquest of the West, and somehow the two work together. If I have to give this book props for anything it’s for being bluntly honest about America’s genocide of the Native Americans at a time when perhaps most white authors would not dare acknowledge this fact.

0 notes

Text

Against Interpretation and Other Essays by Susan Sontag - 3/5

It feels weird to be reviewing what is mostly a book of reviews, but the essays in Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation are classics for a reason: her ability to universalize regardless of the reader’s familiarity with the work she analyses. Like with Dworkin’s Intercourse, I feel like I can appreciate the literary criticism at a deeper level if I’ve read what is being criticized, but each essay still holds something of value. The title essay, and perhaps the second-most famous, “On Style”, are dense little polemics on art and why it is created; as difficult as they are to really engage with, I appreciated Sontag’s perspective (even if I did not fully agree with it). I went through an Ionesco phase when I was younger, but did not agree with her disdain for him; her essay on Robert Bresson on the other hand very much deepened my appreciation of his films. “Notes on Camp” and “The Death of Tragedy” are perennials; the former being the subject of the 2019 Met Gala, and the latter resonating for an almost completely opposite reason, even more poignant today in light of recent events on the geopolitical stage. Perhaps my favorite essay was “The imagination of disaster,” in which Sontag, who comes off as very judgmental and prim about most other things, confesses her love for Godzilla vs. Rodan.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

After Dark by Haruki Murakami - 5/5

The first Murakami book I ever picked up was After Dark, and I have said before, had it been something else (such as Norwegian Wood), I likely wouldn’t have given him a second chance. Luckily, I chose one of his best to start with, and although this may have set my expectations higher than deserved, I was happy to revisit this book many years later. On the surface, After Dark seems simple. I remembered it as a Before Sunrise-esque slice of life story set over the course of a single sleepless night… which is true, but by no means is it all this book has to offer. I remembered some surrealist elements, but I didn’t remember how focal they were. The conceit is a popular cliché in online spaces these days — the liminal space, the Edward Hopper bar (the novel literally opens in a Denny’s at midnight, which seems like a prescient shitpost from five years ago and not something from a novel from the early-aughts — why Denny’s? Does anyone even remember Denny’s insane Tumblr account from a few years ago??). While the main characters’ story still feels very sort of Scott Pilgrim-era indie twee, there is a darker undercurrent that beckons the reader to take this novel seriously, though it reads like YA. Upon my reread, I was impressed with how well these elements fit together, too. I don’t think I’m amiss in sensing an indie film influence though, because parts of After Dark really do read like Murakami wanted to write it as a film script instead. Almost every chapter starts with a scene heading, and all the action takes place externally — the characters’ backstories are conveyed through dialogue instead of internal monologue, and some of the subplots are literally written with specific camera directions. It’s one of those novels that would not have to change much if adapted for the screen, and I fervently await someone to take on the challenge of shooting it.

0 notes

Text

Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics by Andrea Dworkin - 5/5

As long as we have life and breath, no matter how dark the earth around us, that sun still burns, still shines. There is no today without it. There is no tomorrow without it. There was no yesterday without it. That light is within us—constant, warm, and healing. Remember it, sisters, in the dark times to come.

Although Andrea Dworkin is one of my favorite writers and thinkers, the main issue I find with some of my favorite of her works is that, astute as her social critique may be, she seems to be writing to an audience of people who already agree with her. Her prose, while revelatory, probably won’t convince someone who disagrees with a preconceived notion of what her point of view already is. Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics changes that. The difference, I think, lies in that some of her more notable books such as Intercourse or Woman Hating are works of literary criticism, whereas Our Blood consists entirely of transcripts of speeches and lectures delivered to the general public. For this reason, Dworkin is at her most personal, and her most polemical, in this collection. Essays such as “Feminism, Art, and My Mother Sylvia” and “Lesbian Pride” poetically draw from Dworkin’s own life moreso than anything else I’ve read from her; others, like “The Rape Atrocity and the Boy Next Door” explain some of the ideas found in her other works in a more succinct and accessible manner. For me, the centerpiece of the work was the essay “The Sexual Politics of Fear and Courage,” in which Dworkin appeals to women to find the courage buried deep within us — the true courage to love, a “heroic commitment to the worth of human life … If we do betray that commitment, we will find ourselves, hands dripping with blood, equal heroes to men at last.”

#Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics#Andrea Dworkin#radical feminism#feminism#nonfiction#5#september 2024#2024

0 notes

Text

Thus Were Their Faces by Silvina Ocampo - 4/5

Yes, I bought this book only because of the Remedios Varo cover, not knowing anything about it. There is something perfectly apt about this selection, something not quite surrealist and not quite magical realist, that sums up Silvina Ocampo’s writing. I couldn’t figure out if this book was her collected short stories or just a selection over the years, but as a somewhat extensive sampling of her writing, it convinced me to seek out more.

Thus Were Their Faces has a preface from Jorge Luis Borges, one of Ocampo’s contemporaries from her native Argentina. Previously I have not been terribly impressed with Borges’ idea that “Writing long books is a laborious and impoverishing act of foolishness: expanding in five hundred pages an idea that could be perfectly explained in a few minutes,” and I honestly think it is a shame that his fame has eclipsed Ocampo’s, who I consider a far superior writer. Most of her stories in this collection are brief, as brief as anything in Ficciones, but within as few as two pages she is able to distill ideas as efficiently as Borges while not neglecting the flavor of character and setting. I mean, not every story was exemplary; some didn’t make much sense at all, but the best of this collection were insanely good. I marked which stories I liked the best but I left my copy somewhere, but the two that are most worth mentioning were the title story “Thus Were Their Faces” and “The Perfect Crime”. The former is a haunting surrealist tale about angels with the regional verisimilitude of Latin America’s acceptance of spirituality as a daily fact of life, and the latter is a darkly funny murder mystery from the point of view of the culprit. I can only imagine it told without so much dramatic irony!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Birthday Stories edited by Haruki Murakami - 4/5

The short story collection Birthday Stories, edited by Haruki Murakami for his own birthday, is a bit of a “who’s who” of what I somewhat derisively like to call “New Yorker fiction.” The anthology collects stories about birthdays from contemporary authors, mostly English language, from a particular generation. Every anthology will show its editors biases, and Birthday Stories definitely shows a bias towards a certain type of literary fiction that tries hard to downplay its pretension. Still, I enjoyed most of these stories; it’s a good introduction to a cohort of authors I’ve heard a lot about but haven’t had the time to peruse individually. I left my copy somewhere and can’t find a pdf so I won’t be able to review the individual stories as in-depth as I wanted to, but here are the highlights that I remember.

I had read one novel by William Trevor before, his Story of Lucy Gault, and found its questions of Irish national identity interesting (similar to the recent film The Banshees of Inishirin). His short story “Timothy’s Birthday” functioned similarly, though more elegantly in my opinion, with an added social dimension which is hard to discuss without giving some of the story away. I would check it out if you can find a copy, as the social commentary was done very subtly with a lot of refreshing ambiguity.

“Forever Overhead” by David Foster Wallace was one of those short stories that seemed more like an exercise done in a creative writing class, but it was so well done that it made me curious to pick up a copy of his Infinite Jest. It recounts a teenage boy’s internal monologue before jumping off a high dive into a swimming pool, a single moment exploded into a stream-of-consciousness. I can’t make it sound more interesting than it was, but it was objectively well-executed and had shades of Bret Easton Ellis.

Murakami did not do Andrea Lee’s “The Birthday Present” justice in his brief introduction, opting to say nothing about the story but in characteristic Haruki fashion, making some sort of sexist remark about how attractive she was when they met. This was probably my favorite story in the collection; once you figure out what’s going on in the story, it’s downright crazy. It served as an effective character piece without falling victim to what a lot of New Yorker stories do, which is only considering character and neglecting plot (the opposite is bad too)!

Lewis Robinson’s “Ride” is the most whimsical and least literary story in the collection (I say this as a good thing.) It felt like it could be a children’s book, or a Wes Anderson movie; finding the delicate balance between humor and poignancy.

It would be remiss not to mention the story that Murakami wrote expressly for this collection, “Birthday Girl.” I have never preferred his short-form work, because there is a fine line between ambiguous and lazy in my opinion. “Birthday Girl” has a characteristically frustrating ending, but it stays with you long after you read it. It is not his best short story, but definitely worth checking out.

Most of the rest of the stories were passable to decent. I only actively disliked one or two stories in this collection. Despite kind of a weird theme linking the stories together, it felt cohesive and an easy initiation to those who don’t usually tend to seek out short stories.

1 note

·

View note

Text

South of the Border, West of the Sun by Haruki Murakami - 4/5

Previously I admonished one of Haruki Murakami’s earliest attempts at realism, the critically acclaimed Norwegian Wood that read like a juvenile fantasy. In some ways, South of the Border, West of the Sun feels like a sequel to Norwegian Wood; more mature but sharing some of the same failings, namely the apparent lack of tutorial distance. Murakami is apparently an only child from the baby boomer generation who ran a jazz bar before becoming a writer — if these similarities to his protagonist were a coincidence I would be surprised! South of the Border, West of the Sun tells the story of Hajime, his protagonist, reconnecting with his childhood best friend who was in love with him. If I weren’t going through similar feelings right now, I would probably not be as generous to this book, but like Mary by Vladimir Nabokov, the universality really hit me hard. It’s unquestionably generic, and even if that doesn’t make for the most interesting literature, it’s something that the heartbroken can easily relate to.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary by Vladimir Nabokov - 4/5

An author’s first work is rarely their best, even in the case of a talent such as Nabokov’s. But what makes Mary an immature work is also what makes it so powerful. I read Mary breathlessly over the course of just a few days, which is not a difficult feat as it is little over a hundred pages. Perhaps I only found it so heartwrenching because I am currently going through something similar to the protagonist, as Nabokov did himself, and as surely almost everyone has at one point or another in their lives. The plot of Mary is not significantly different from that of the Katy Perry song “The One That Got Away,” tacky but once it happens to you, you can’t listen to it without crying. The protagonist, Lev, finds out that the titular Mary who he had a fling with five years prior is not only married to a man staying at the same pension as him, but is on her way there. He then spends most of the novel recalling his brief affair with Mary. Not much happens in this novella, and some of the passages that were the most disappointingly on-the-nose were also amongst the most poignant:

“His shadow lodged in Frau Dorn’s pension, while he himself was in Russia, reliving his memories as though they were reality. Time for him had become the progress of recollection, which unfolded gradually. And although his affair with Mary in those far-off days had lasted not just for three days, not for a week but for much longer, he did not feel any discrepancy between actual time and that other time in which he relived the past, since his memory did not take account of every moment and skipped over the blank unmemorable stretches, only illuminating those connected with Mary. Thus no discrepancy existed between the course of life past and life present. It seemed as though his past, in that perfect form it had reached, ran now like a regular pattern through his everyday life in Berlin. Whatever Ganin did at present, that other life comforted him unceasingly.”

Lev and Mary are woefully generic. Though this may be the mark of an inexperienced writer, it also enables the reader to relate more, which is honestly half of the appeal of this book. It is an over-the-top tragic romance that contains hints of Nabokov’s later genius, so I can’t not recommend it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unknown Language by Hildegard of Bingen and Huw Lemmey - 3/5

I find channeling to be an interesting literary device, moreso than it is a serious New Age practice. Tom Kenyon and Judy Sion’s Magdalen Manuscript was more interesting to me as a work of fiction than whatever channeled authenticity they were claiming about it. Which is what drew me to what Huw Lemmey has done with Saint Hildegard’s texts here in Unknown Language. The book is attributed “by Hildegard of Bingen and Huw Lemmey,” but really, it’s a contemporary work of (science) fiction heavily inspired by the visions of Hildy. Is the attribution false advertising? Maybe, but Lemmey’s intent is pretty obviously not to deceive.

Unknown Language is something between the eschatological writings of Anna Kavan in Ice, the abstract prose of a later Jeff VanderMeer, and some of the surreal dream-like imagery of a darker Miyazaki film. It’s disjointed, but the story tells of a woman fleeing a post-rapture city occupied by tyrannical angels and her sapphic fling with a prostitute and fellow refugee. I would argue that, while the worldbuilding is rich, not much actually happens in this book, and I found the prose pretty hard to follow. It’s a compelling piece of abstract science fiction, but some of the Hildegardian inspirations seem somewhat forced and an attempt to get a recognizable (and a bit trendy) name on the cover. For example, towards the beginning, the unnamed protagonist prepares a remedy for chest infection straight out of Hildegard’s Physica, which is total pandering, but in a way that I love.

0 notes

Text

[series review] The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins - 3.5/5

I picked up The Hunger Games because I wanted something easy and kind of stupid for a stressful road-trip, but I found myself interested enough that I bought the second volume Catching Fire on the trip. I didn’t remember ever reading it, though I had seen the movies, but my friend mentioned some plot twist that wasn’t in the first movie and I did remember it so apparently I had read the first book as a kid but evidently it wasn’t notable enough to remember in great detail. I wouldn’t say this series is great, but it certainly is evocative of its time, the same way that John Green or Lorde or Vine feels like high school to me. And I still found myself entertained, so these books filled their purpose for me.

The first two were genuinely very engaging, if a little lacking in depth. I would not use the word poignant to describe these books, because as much real-world relevance one tries to eke out, only surface-level interpretations can be drawn. Is The Hunger Games a story about leftist freedom fighters — or is it a right-wing parable about blue-collar coal miners fighting villains that kind of look like drag queens? I am not saying Suzanne Collins intended either message, but I think her reluctance to include any sort of political commentary in an overtly political story is a very smart and even shrewd marketing strategy, even if it is not one I respect.

The first volume, the titular Hunger Games, is high concept and a story everyone of a certain generation knows: a Battle Royale on reality television. It’s staggeringly effective as a thriller, even if it is sort of comically over the top. I found myself laughing a lot at parts that definitely weren’t supposed to be funny, because most of the book is just people dying in increasingly over-the-top ways. By Catching Fire, Collins successfully found a direction to take the series without making it too repetitive… until they just do a Hunger Games All Stars? Repeating the games was not terribly interesting to me compared to the more plodding sections on the rebellion. By the third book, Mockingjay, I felt the series was starting to lose momentum and I definitely did not enjoy it as much as the first two. The one aspect I really thought was funny was how sort of annoying the rebellion was, but the story itself seemed overly meandering and without purpose, until the admittedly powerful ending.

I am not sure what I got out of reading these books aside from pure entertainment, but I suppose there is room for that in the new canon of contemporary literature. The characters are interesting, if a bit one-dimensional, but Collins’ real strength is in her worldbuilding. I was driving through Colorado as I read this series, and kept visualizing how her bizarre vision of a future dystopia would look grafted onto the Rocky Mountains. For all its deficiencies, you can’t say The Hunger Games isn’t an imaginative series.

5 notes

·

View notes