Photo

1 note

·

View note

Link

Germany is making social networks and social media sites accountable for their users! Hitting them where it counts - in the pocket book 💰

“They must delete threats of violence, slander, and other hateful content within 24 hours of the complaint, or within a week if the issue is more legally tricky. The government can fine the firms up to €50 million (£45 million) if they don’t comply.“

Sites that do not remove “obviously illegal” posts could face fines of up to 50m euro (£44.3m).

The law gives the networks 24 hours to act after they have been told about law-breaking material.

Social networks and media sites with more than two million members will fall under the law’s provisions.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube will be the law’s main focus but it is also likely to be applied to Reddit, Tumblr and Russian social network VK. Other sites such as Vimeo and Flickr could also be caught up in its provisions.

The Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (NetzDG) law was passed at the end of June 2017 and came into force in early October.

The social networks were given until the end of 2017 to prepare themselves for the arrival of NetzDG.

Germany’s strict new law about social media hate speech has already claimed its first victim, Business Insider

Lying fascists, welcome to 2018.

The new law has already claimed its first scalp in far-right politician Beatrix von Storch, who is under police investigation after describing Muslims as “barbarians” on Facebook and Twitter.

251 notes

·

View notes

Photo

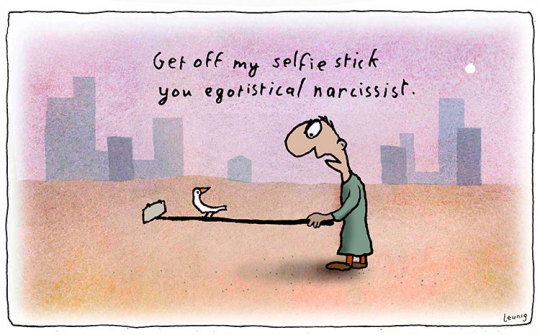

May 5, 2016 | Ronny Chieng on The Daily Show talking about selfie culture

9K notes

·

View notes

Photo

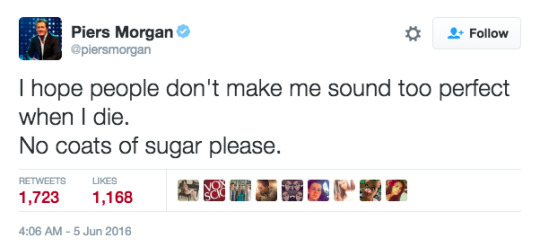

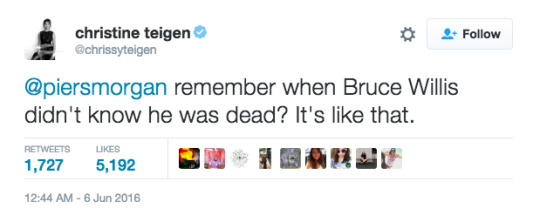

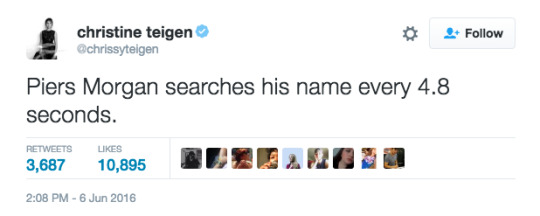

Chrissy Teigen is trolling Piers Morgan with the most delicious intensity right now

84K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here here! I’ll take UNO over online gaming any day! And I for one am beyond grateful that the Pokemon Go craze is over. It was the bane of my existence when my local train station was transformed into a “training center” that warranted 50 odd people blocking the entries and exits at any given time. I will admit though, that it was a very interesting attempt at merging the real and virtual worlds!

GAME ON - SOCIAL GAMING

Online gaming is entirely another world, this digital community has grown exponentially in the last 20 years. But it was the 2000’s that started the era of gaming we see today. “As the 2000s began with the dot-com bubble bursting, you might have thought tech was risky. What actually occurs is online gaming begins to do what gamers have been waiting almost 2 decades for” (Rivenes 2017)

I personally am not a gamer, the furthest I’ve gotten was on a SEGA, then Mario Kart on Nintendo and now occasionally, arcade games at a Time Zone outlet. Although I did have a phase after Facebook upped their gaming configurations of simultaneous running a farm (Farm Town), theme park (Coaster World), restaurant (Restaurant City) and cafe (Cafe World). It was exhausting being a tycoon and I soon consolidated my assets and deactivated my franchise.

A housemate of mine, on the other hand, delved right into the online gaming community, they played COD (Call of Duty) in an MMOG, had a very high ranking, headed up an all-female squad, would wake in the late afternoon to play all night tournaments, and would share stories of trolling, abuse, threats, verbal sexual taunts, racism and even more creative narcissistic behaviours in these digital communities. I always wondered why they went back, with so much harassment why continue to participate?

But my housemate was an introvert with a social anxiety disorder, and basically as Stuart (2013) describes being a part of an online community takes away traumas and inhibitions, and gamers are able to create, contribute and participate with a community that understands them. For the most part.

But who are these “games”? Here some states to clear that up; “68% of Australians play video games. 47% of video game players are female. 33 years old is the average age of video game players. 78% of players are aged 18 years or older. 39% of those aged 65 and overplay video games. 12 years is the average length of time adult players have been playing” (Brand & Todhunter 2016).

And now with smartphones, the gaming communities just keep growing, remember the Pokemon pandemic? But even as the Pokemon craze slowed gaming hasn’t, but it’s not all about the players. The industry itself is peaking as “gaming has become so popular that some schools are adding professional video gaming and esports to their curricullum [sic]” (Milligan 2018)

The gaming world does not just consist of first player games, or MMOG’s, but there is also gambling communities, which are highly unregulated. Other games require you to spend real money to be able to progress in the game. There are worldwide gaming conventions as well as continuous play live gaming tournaments or E-Sports played out in “Multiplayer online battle arenas, or MOBAs” (Jensen 2015). And then there was Jon Eimer who “broke the world record for longest video game marathon on a MOBA game, coming in at 72 hours with two allocated breaks” (Bishop 0217), think about that for a minute…

As our future moves closer to becoming all online and virtual, with STEM education taking over precedence of future employment gaming communities may, in fact, be in front of the rest of us who do not participate in this lifestyle. That’s ok with me, you’ll still find me at home playing UNO with my real life community with Blade Runner in the background.

REFERENCES

Bishop, S 2017, Streamer breaks record for longest marathon on a MOBA, Gamereactor, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.gamereactor.eu/esports/508323/Streamer+breaks+record+for+longest+marathon+on+a+MOBA/>.

Brand, J E & Todhunter, S 2016, Digital Australia report 2016, Bond University, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.igea.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Digital-Australia-2016-DA16-Final.pdf>.

Jensen, T 2015, The greatest gaming tournament in the world, PCmac.com, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.pcmag.com/feature/332886/the-greatest-gaming-tournaments-in-the-world>.

Milligan, M 2018, Gaming goes mainstream for both playing and watching, Limelight networks, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.limelight.com/blog/state-of-online-gaming-2018/>.

Rivenes, L 2017, The history of online gaming, Datapath.io, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://datapath.io/resources/blog/the-history-of-online-gaming/>.

Stuart, K 2013, Gamer communities: the positive side, The Guardian, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2013/jul/31/gamer-communities-positive-side-twitter>.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In defence of online gaming

Gamers get a bad rep. I’ll be the first to admit that I have long been a believer that gaming is a sign of laziness, an unhealthy escape from the pressures and expectations of the real world. Barely a week goes by without the media reassuring us that gaming leads to all kinds of grizzly ends, from opioid overdoses to obesity, school shootings, and parental neglect. There seems to be no in-between, only non-gamers or gaming addicts, destined to become baby-starving recluses with wasted lives. I honestly wasn’t expecting to have much to say on the topic. Games exist, people waste their time playing them, the end. I was wrong.

As I’m sure is evident, my gaming experience is extremely limited. I played Sims growing up, a bit of Mario Kart here and there, spent a solid month trying to play Call of Duty whilst living in a college dorm in the dead of winter, and had a very brief fling with Candy Crush. My interests and hobbies lay elsewhere, but for 14.5 million gamers in Australia alone (Liddy & Tilley 2018), it may well be the most common form of entertainment – and the most active users are not who you would think. The online gaming world is of epic proportions, with over half a million subscribers participating in the virtual massively multiplayer online world of EVE Online (de Zwart & Humphreys 2014, p.77), and an even more staggering 45 million player base logging into the current blockbuster, Fortnite (Romano 2018). Whilst on the outside appearing to be a lonesome existence, online games have become a place to form relationships, catch up with friends, and forge communities.

youtube

The most intriguing intersection of digital communities is apparent in the phenomenon of online game streaming. At face value, it makes no sense – why on earth would anybody want to watch other people play games?! But this game-lover’s spectacle has taken off at breakneck speed, and young gamers are spending an average of almost three and a half hours each week (that’s an hour more than is spent watching actual sports) watching their favourite streamers tap away at their computers for the simple reason that, like star athletes, they’re good at what they do. Comparable to what Instagram did for the millennial influencer, streaming platforms like Twitch (which I will admit, I had never heard of) have made career gaming a reality, drawing the attention of some hundred million visitors and their credit cards each month (Clark 2017). Indeed, a good portion of YouTube’s highest-earning users are gamers, some easily raking in six-figure salaries through subscriptions and sponsorship deals. Game streaming has generated a new form of digital community, one that borrows from the content creating like-minded fandoms of YouTube, whilst incorporating the real-time communication affordances of instant messaging and old-school chat rooms. A real sense of community has been crafted, and as a Twitch spokesperson states, “we’re essentially a social network for the gaming age” (Clark 2017).

As the worlds of social media and gaming collide, it begs the question of why we aren’t as quick to criticise the likes of professional bloggers or Instagram influencers, as we are career gamers. Their mission statements are, at their core, identical – to create content and navigate the attention driven economy of the online world for commercial gain. Like those trying to amass followers on other platforms, popular streamers face the same pressures of the “always on” cyberspace – their unnegotiable online presence and need to attract and maintain public attention. A far cry from lazy work, some streamers are broadcasting days long marathons, barely stopping to eat or even use the bathroom. There’s a demand (more people tune in to watch the League of Legends World Championships than the NBA finals), and if people are enjoying it, who are we to judge?

youtube

Like any hobby or career, online gaming has its drawbacks. There are definite health concerns that come with engaging in all night benders, but perhaps more heart attack than mental health-related, as the media would have you believe. The lack of regulation or an enforced code of conduct in the virtual world has repercussions, particularly surrounding cyberbullying and the treatment of female gamers. But, as long as gamers are not straying into the realm of addiction, committing hours to gaming is surely no more harmful to society than taking 1000 photos for a single Instagram post, or spending several mind-numbing hours in a Netflix black hole. I’ll be thinking twice before I jump on the gamer-hating bandwagon from now on.

References

Clark, T 2017, 'How to Get Rich Playing Video Games Online', The New Yorker, 20 Nov 2017, Available at <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/20/how-to-get-rich-playing-video-games-online> (Accessed 3 June 2018).

de Zwart, M & Humphreys, S 2014, 'The Lawless Frontier of Deep Space: Code as Law in EVE Online', Cultural Studies Review, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 77-99.

Liddy, M & Tilley, C 2018, 'Chart of the day: Online gamers don’t fit the stereotype', ABC News, viewed 3 June 2018, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-05-29/chart-of-the-day-online-gamers/9784286>.

Images and video

‘How Do Twitch Streamers Make Money’ 2018 [video], Techquickie, viewed 4 June 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QeNwrVTCy4>.

‘Penny going downhill’ 2008 [image], The Big Bang Theory, viewed 3 June 2018, <http://bigbangtheory.wikia.com/wiki/The_Barbarian_Sublimation>.

‘This is FORTNITE - “This is America” Recreation’ 2018 [video], WiziBlimp, viewed 3 June 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhSFQXBVt1E>.

0 notes

Text

#myauthenticfabulouslife

Camera phones and social media – name a more iconic duo.

It seems almost impossible to remember a time when snapping a picture of your dinner wasn’t the norm. When the term “selfie” didn’t exist, and photos existed only in albums and frames scattered around your grandma’s house. When you were lucky to get even one photo of your mug each year, and it would be distributed to friends and family far and wide as visual evidence of your growth and achievements, tucked inside the annual family Christmas card. Trying to explain this concept to people who have grown up with the back of an iPhone pointed at them makes me feel older by the second. “Back in my day, you had to walk a mile to get your film processed, and when you got them back, half your photos were unrecognisable”. Somewhere in my house, there’s a box of cameras gathering dust that have been ruled obsolete. There’s no time for developing film or searching for camera cables – posting a photo more than 24 hours after it was taken will warrant a #throwbackthursday or #flashbackfriday. We need photographic evidence of our fabulous lives, and we need it right now.

youtube

Social media has become an important tool of social self-formation (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292), providing us with a means to archive moments that we deem important enough to share with the masses. Visual media has turned everyday life into a public performance (Khamis, Ang & Welling 2017, p. 199), a vapid competition of whose content can generate the most attention, in a world where content is abundant and attention, depleting. With every like, comment, and follow, we are reaffirming social conventions of what merits our attention and why (Lange 2009, p. 70) – and narcissism wins every time.

During the process of social media taking over our lives, the concept of public vs. private got lost somewhere along the way. This constant state of connectedness brought with it an expectation of constant exposure and self-disclosure (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292), and from that we have somehow construed that every second of our lives is worthy of sharing. Scrolling through your Instagram feed, it’s not uncommon to find a never-ending stream of gym selfies, lunch pics, bathtub selfies, dog pics, #ootd selfies, sunset pics, and selfies “just because”. Our curated lives – allowing us to be seen exactly as we’d like, no matter how edited or misleading. And while it is fair to assume that we can strike up the perfect mix of FOMO and admiration with a pretty vacation picture, the most intriguing phenomenon of all is our fascination with posting pictures of ourselves. Studies suggest that selfie culture exists predominantly amongst young women, and there are a multitude of explanations on offer. Is it out of pure narcissism? A need for validation in a world where self-esteem seems to be at an all-time low? Some suggest that it’s the deliberate act of women claiming back their bodies and independence in a voyeuristic man’s world (Murray 2015, p. 490). Whatever the reason, we’re all here for it. A recent study has determined that pictures containing our faces are 38 percent more likely to bring in the likes, and 32 percent more likely to attract comments.

With the popularity of shameless self-promotion on Instagram, a whole generation of social media “influencers” has risen from the sea of likes. Bypassing the traditional gatekeepers of celebrity status, your ability to rack up followers has become the standard for measuring fame and success (Khamis, Ang & Welling 2017, p. 198). And our willingness to take their photos at face value has come at a cost, reaffirming - perhaps to a greater extent - the standards of beauty and good living that have long been enforced by traditional media. The constant bombardment of (usually carefully staged) selfies has been hugely detrimental to self-esteem. And in our own efforts to emulate, plastic surgeons have noted that apps that allow us to filter our appearances are grooming us for plastic surgery down the track, and children as young as three are already working on perfecting their poses (Diefenbach & Christoforakos 2017, p. 2).

It’s a strange contradiction when sharing more of our lives online also means sharing less of our real, authentic selves. I personally don’t post many photos of myself online, not because my life is particularly uninteresting (hell, I eat dinner, go to the gym, pat dogs, etc as much as your average mid-level influencer), but because production expectations for an Instagram-worthy shot are far beyond the level of effort I’m willing to put in. This is not to say I am above the anxieties that come with social media posting that affect the best of us. With every photo I share, the question remains - am I just posting for the likes?

References

Diefenbach, S & Christoforakos, L 2017, 'The Selfie Paradox: Nobody Seems to Like Them Yet Everyone Has Reasons to Take Them. An Exploration of Psychological Functions of Selfies in Self-Presentation', Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1-14.

Khamis, S, Ang, L & Welling, R 2017, 'Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers', Celebrity Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 191-208.

Lange, PG 2009, 'Videos of affinity on Youtube', in P Snickars (ed.) The Youtube Reader, National Library of Sweden, Stockholm, pp. 70-88.

McCosker, A & Wilken, R 2014, 'Social Selves', in S Cunningham and S Turnbull (eds), The media & communications in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 291-295.

Images and video

‘How Millenials Became the Selfie Generation’ 2018 [video], The New Yorker, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3_CHnYg-yc>.

‘Selfie Stick’ 2016 [image], Michael Leunig, viewed 3 June 2018, <http://www.leunig.com.au/works/recent-cartoons/688-selfie-stick>.

#mda20009#digitalcommunities#selfie culture#social media#folllow4follow#like4like#narcism#instagram#influencer

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crowdsourcing - by the people, for the people

There’s no denying that a solution to almost any problem can be found on the internet. Armed with our devices everywhere we go, this “always-on” ecosystem of peripheral connections (boyd 2012, p. 73) has opened up a world of possibilities, and also a world of combined knowledge and resources. Whether it’s solving complex problems or looking for advice on stain removal (also complex, in my opinion), a simple shout into the cyberspace void can yield more answers than you’ve ever dreamed of. “Crowdsourcing”, as it’s called, captures the magic of the seemingly infinite number of human computation systems available online – an estimated 5 billion by 2020 to be exact (Deloitte LLP 2016, p. 7), tapping into the ‘wisdom of the crowd’ for the purposes of collaboration, innovation, and labour.

youtube

A melody written by a crowd - https://crowdsound.net/

I will admit – when the word first popped up on my screen, I was hard-pressed to think of a single occasion in which I had taken part. Sure, one time I contributed $10 to a Kickstarter for a Veronica Mars movie reboot (worth it), and I’ve definitely wondered what kind of work quality I’d get back if I popped a couple of uni assignments on Airtasker. But the reality is that, much like we now take the internet for granted, variations of crowdsourcing are so ubiquitous in our lives that we no longer think twice about what we’re doing. This concept covers everything from fundraising efforts to scientific research, affording the diverse universe of anyone with an internet connection the ability to invest in a start-up or discover a supernova (Stargazing Live, anyone?), with minimal knowledge or expertise. Big brands are even incorporating crowdsourcing into their marketing strategies, offering regular consumers the chance to express their ideas – with mixed results.

Perhaps one of the most well-known crowdsourcing initiatives is Wikipedia. Since 2001, over 33 million users have contributed to 5,659,935 articles, or 45,088,806 pages at time of posting – and that’s just the English language section. Whilst its reliability is a little contentious, its general expansiveness and up-to-date nature have made Wikipedia the go-to resource for all basic information searches (Michelucci & Dickinson 2016, p. 32), and an important weapon in winning many an argument.

Users of social media platforms are likely more familiar with a less obvious form of crowdsourcing – the humble hashtag. These user-generated flags are used to indicate a message’s relation to a theme or topic (Bruns et al. 2012, p. 7), and can be used for anything from curating brunch pictures on Instagram, to reporting on major events and coordinating emergency response. In emergencies, where communication is key, specific hashtags have played an important role in both gathering information from the public, and disseminating important information back to them (Simon, Goldberg & Adini 2015, p. 209), where other communication channels may have failed. Harnessing this data, platforms like Ushahidi can map disaster zones or political events, allowing virtual and field teams to better provide aid, and providing a mouthpiece to those who may otherwise be silenced (Ford 2012, p. 33; Simon, Goldberg & Adini 2015, p. 613).

No matter the application, the main issue associated with crowdsourcing is reliability. When you open the gates to the minds of the masses, you’re no doubt going to run into some misguided contributions, and maybe even sabotage. Whether it’s a virtual manhunt or trivial research, the risky crowdsourcing path will always have a giant question mark looming over it. And it’s a fine line between maintaining verification procedures and reinstating the gatekeepers that social media, at its core, avoid.

But I for one am happy to take my internet searches with a grain of salt. The combined brainpower of millions is arguably the greatest affordance of the internet, and the scientific and social advances that crowdsourcing have allowed far outweigh the bad. My internet search history alone is a testament to this - just this morning I called upon the wisdom of the message boards to help me brew a cup of coffee. I’ll drink to that.

References

boyd, d 2012, 'Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle', in M Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, New York, pp. 71-76.

Bruns, A, Burgess, J, Crawford, K & Shaw, F 2012, #qldfloods and @QPSMedia: Crisis Communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland Floods, Arc Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation, viewed 30 May 2018, <http://www.cci.edu.au/floodsreport.pdf>.

Deloitte LLP 2016, The three billion: Enterprise crowdsourcing and the growing fragmentation of work, Deloitte, viewed 30 May 2018, <https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/Innovation/deloitte-uk-crowsourcing-pov.pdf>.

Ford, H 2012, 'Crowd Wisdom', Index on Citizenship, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 33-39.

Michelucci, P & Dickinson, JL 2016, 'The power of crowds', Science, vol. 351, no. 6268, pp. 32-33.

Images and video

‘A melody generated by a crowd’ 2016 [video], Crowd Sound, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgcA5A_Fm_0>.

‘Solange Knowles’ Wikipedia occupation’ 2014 [image], Metro, viewed 1 June 2018, <https://metro.co.uk/2014/05/13/solange-knowles-labelled-as-jay-zs-100th-problem-by-wikipedia-prankster-4726327/>.

‘We Didn’t Make Our Kickstarter Goal for Steak’ 2013 [image], Joe Dator, The New Yorker, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://condenaststore.com/featured/we-didnt-make-our-kickstarter-goal-for-steak-joe-dator.html>.

#mda20009#digitalcommunities#social media#crowdsourcing#crowdfunding#hashtags#kickstarter#wisdom of the crowd

0 notes

Text

Dealing with cyberbullies in the online playground

Not so long ago, the internet was a very different place. In the year 2000, it was all dial tones and askjeeves.com, and social connectivity meant sending emails back and forth. Now the internet isn’t so much a tool as it is an augmentation of ourselves, where your online presence is just as (if not more) important, as your physical presence. Your friends, family and strangers alike are always with you, in a digital form at least, ready and willing to offer their two cents with the click of a button. But in this new virtual space, the rules are somehow different. There’s no need for niceties or genuine human interaction, and ethical norms and social conventions are challenged and renegotiated every day (boyd 2012, p. 75). We live in an “economy of attention”(McCosker 2014, p. 203), and being seen and heard matters above all else.

Code Name Melania - click here to see the rest - it’s worth it

Cyberbullying and trolling are hot topics in the media these days. Even Melania Trump, has named fighting cyberbullies as her chosen cause (an interesting choice, for obvious reasons). Taking schoolyard fights online is the norm now (boyd 2014, p. 130), following kids home with a relentless verbal bashing in the palm of their hand. And it’s not just the youths that have gone wild. Fully grown adults are tearing each other apart all over the internet from the comfort of their own homes, some more sinister, and others just messing with people for fun. Our inability to be decent human beings when given a platform has reached epidemic proportions, but the question remains – is this a social media issue, or have our real-world conflicts just found a new home?

youtube

My schooling experience seemed to coincide with a major shift in online behaviours. In primary school, I had nothing more than an e-mail address (cyber_kitty – in hindsight a terrible idea) and a Neopets account. My tweenage years saw a boom in instant messaging, and the couple of valuable hours of internet access I had each afternoon were spent discussing (and causing) drama amongst my friendship circles. The scariest things on the internet were perverted chat rooms, which I was strictly forbidden from entering. LiveJournal, Bebo and MySpace changed the game though. Suddenly our young lives and tortured teenage souls were on show to the outside world and an influx of ‘anonymous’ users. Meanness had always existed, but on notes passed around the classroom or in a lunchtime gossip session. With social media though, the attacks could come from anywhere and anyone, long after the school bell had rung. The difference for my Nokia 3310-wielding generation though was that we had the choice to disconnect – an affordance that isn’t plausible for many in 2018.

These online behaviours have serious consequences. Studies suggest that over 33% of youths in the U.S. have been the victim of cyberbullying and that young victims are twice as likely to attempt suicide and/or self-harm. Most alarmingly, there is a rising trend of young people bullying themselves via anonymous or fake social media accounts (boyd 2014, p. 141; Fraga 2018), perhaps for attention or maybe to validate their own feelings of hopelessness. There is no doubt that young people, who seem particularly attached to their devices, are especially susceptible to these kinds of attacks, however, it is also important to consider that many victims are often also perpetrators (Ewens 2017). The veil of anonymity that platforms offer, combined with this strange perceived notion that online activities don’t have real-world consequences, have taken “freedom of speech” to a scary new level. This “cyberbullying” umbrella term has also blurred the lines between plain old conflict and downright harassment, further changing our perceptions of how we are allowed to treat each other, and what the ramifications will be when we do so (boyd 2014, p. 132).

Bullying and general nastiness have always existed. And there is no doubt that this new constant state of connectivity and public exposure has upped the ante, and unpoliced social media platforms are the weapon of choice. It seems inappropriate to approach this as a “social media issue” though, and nor does it seem right to say our antics have moved to a “new home”. There is no longer a separation between cyberspace and the physical universe, and with the affordances of constant communication, it makes sense for an exponential rise in meanness to coincide. I see no end in sight, as platform-based regulation can only ever truly be as effective as our own abilities to be decent human beings. And is logging off truly worth the risk of becoming invisible?

References

boyd, d 2012, 'Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle', in M Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, New York, pp. 71-76.

boyd, d 2014, It’s complicated: the social lives of networked teens, Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

Ewens, H 2017, 'The Ugly Evolution of Cyberbullying', Vice, 1 September, Available at <https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/gyy8kq/the-ugly-evolution-of-cyberbullying> (Accessed 22 May 2018).

Fraga, J 2018, 'When Teens Cyberbully Themselves', NPR, 21 April, Available at <https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/04/21/604073315/when-teens-cyberbully-themselves> (Accessed 22 May 2018).

McCosker, A 2014, 'Trolling as provocation: YouTube’s agonistic publics', Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 201-217.

Images and video

‘Celebrities Read Mean Tweets #7’ 2014 [video], Jimmy Kimmel Live, viewed 27 May 2018, <https://youtu.be/imW392e6XR0>.

‘Code Name Melania: Secret Agent Fighting Cyber Bullying’ 2017 [image], Ward Sutton, The New Yorker, viewed 27 May 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/humor/daily-shouts/code-name-melania-secret-agent-fighting-cyberbullying>.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clicking your way to freedom - does social media activism translate to real world change?

In 2011, Time Magazine named Wael Ghonim as one of the Most Influential People of the Year. Via a Facebook group he had led the call for thousands to take to the streets of Cairo, the start of a series of events that would inevitably lead to the overthrow of a 30-year regime (ElBaradei 2011). Reaching the masses via Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, this “Facebook revolution”, as the media liked to call it (Shearlaw 2016), was one of many events that would occur in the middle east and surrounding areas during the Arab Spring. Social media platforms proved themselves as an incredibly useful tool for mobilisation, as well as for spreading news to the outside world in a regime-controlled media landscape, setting the benchmark for future activists.

Indeed, two years later when revolution occurred again in Egypt, it was social media calls that brought the masses back to Tahrir Square (Shearlaw 2016). Across the Mediterranean, the people of Turkey too were feeling the buzz of the Arab Spring. When protests broke out in Istanbul, Twitter and Facebook became the primary sources of information for those occupying Gezi Park and foreign news outlets alike, circumventing the news blackouts sanctioned by the Turkish government and broadcasters (Hutchinson 2013). Rattled by the wavelike effect of social platforms, the Prime Minister of Turkey went as far as calling them a “menace to society” (Knibbs 2013). But looking back on these events, is it the hashtags or the images of thousands gathered in public squares that are burnt in your memory?

Whilst the likes of Facebook and Twitter undoubtedly played important roles in mobilising support, to credit them with the success of actual change is to do a disservice to those who were on the ground and their circumstances. In 2013, I decided to pack a bag and head off to Turkey and Egypt. Unbeknownst to me (or perhaps due to my inability to follow the news), I was about to waltz into two countries on the brink of revolution. I was quickly made aware of my error when I pranced out of my hostel in Istanbul on Day 1, straight into a cloud of tear gas – word to the wise, the term “tear gas” is a gross understatement of where exactly it’s going to hurt i.e. everywhere. On the day we went up to Taksim Square, we weren’t met with a mob of thousands, armed with their phones, fiercely tweeting, but rather a disillusioned public physically occupying a space, whilst being met with a violent pushback by police. The protests that defined these pro-democracy uprisings across the middle east certainly had social media in common, but so too were their factors of years of state repression and social issues, and a people ready for change (Shearlaw 2016; Youmans & York 2012, p. 316).

In the digital age, where the activist population is equipped with mobile technology, social media serves the same role that the newspaper or flyer did for previous movements (Gerbaudo 2012, p. 4). Offering a public space for expression and information distribution, anger, pride and shared experience combine in online forums and often translate into real world action (Gerbaudo 2012, p. 14; Youmans & York 2012, p. 315). Posting the locations and intentions of protestors on public forums, however, comes with its risks. Open to the public also means open to government security officials, and with that a risk to personal safety. These causes also fall victim to the trolls that run rampant on the internet and ever-present instigators of moral outrage. As put by Ghonim, when speaking about the current state of activism in Egypt, “the same tool that united us to topple dictators eventually tore us apart” (Shearlaw 2016).

Opening the gates of a movement to anybody who has a social media account also places unrealistic expectations on its success. The ease of action means users are quick to identify as supporters when it comes to clicking ‘Join’ or ‘Like’, or adding the odd hashtag to a selfie at a safe distance from the action, but not so quick to picket. Yet those whose social feeds are filled with their symbolic good deeds reap the same satisfaction of meaningful impact as those camping out in city centres – and this mentality trickles all the way down from revolutions to charity fundraisers. In fact, studies suggest that those who offer token support are no more likely at all to offer substantial monetary or physical contributions to a cause (Kristofferson, White & Peloza 2014).

youtube

In a society driven by likes and followers, and the perceived social status they award, adding the title of ‘Activist’ to your profile is all too appealing. Whether it boils down to laziness or a genuine belief that a retweet will feed a starving child in Africa or end a civil war, the role of social media in creating meaningful change is dubious. I appreciate the positive effects social campaigns like #MeToo and #NeverAgainMSD have had on raising awareness of existing social issues and mobilising supporters, but I’m yet to be convinced that social media really deserves the “revolutionary” praise it receives. But unlike almost everything else in my life, I’d love to be proven wrong on this one!

References

ElBaradei, M 2011, 'The 2011 Time 100: Wael Ghonim', Time, 21 April 2011, Available at <http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2066367_2066369_2066437,00.html> (Accessed 11 May 2018).

Gerbaudo, P 2012, Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism, Pluto Press, London.

Hutchinson, S 2013, 'Social media plays major role in Turkey protests', BBC News, 4 June 2013, Available at <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-22772352> (Accessed 12 May 2018).

Knibbs, K 2013, 'Arrested for tweeting in Turkey: The social media machine of the #Occupygezi movement', Digital Trends, viewed 11 May 2018, <https://www.digitaltrends.com/social-media/the-invaluable-role-of-social-media-in-occupygezi-and-protest-culture/>.

Kristofferson, K, White, K & Peloza, J 2014, 'The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action', Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1149-1166.

Shearlaw, M 2016, 'Egypt five years on: was it ever a 'social media revolution'?', The Guardian, 25 January 2016, Available at <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/25/egypt-5-years-on-was-it-ever-a-social-media-revolution> (Accessed 10 May 2018).

Images and video

‘A man during the 2011 Egyptian protests carrying a card saying "Facebook, #jan25, The Egyptian Social Network" illustrating the vital role played by social networks in initiating the uprising.’ 2011 [image], Essay Sharaf, viewed 12 May 2018, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2011_Egyptian_protests_Facebook_%26_jan25_card.jpg>.

‘Hashtag activism’ 2017 [image], Eric Allie, Furious Diaper, viewed 11 May 2018, <http://furiousdiaper.com/2014/05/14/hashtag-activism/>.

‘Your ‘Like’ Doesn’t Help Charities, It’s Just Slacktivism’ 2013 [video], DNews, Seeker, viewed 10 May 2018, <https://youtu.be/efVFiLigmbc>.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are social media platforms bad for democracy?

From revolutions to presidential elections, there is little doubt that the realm of Web 2.0 has real-world political consequences. Social media has long been heralded as a tool for liberation, giving a platform to those who had been excluded from the political arena, and affording them the ability to mobilise support (Tucker et al. 2017, p. 47). Likewise, official Facebook and Twitter accounts have become commonplace on the campaign trail, providing a forum for politicians to reach the masses and niche audiences alike (Young 2010, p. 221).

The events of the 2016 U.S. presidential election have raised serious questions over the capacity of such platforms to interfere with the democratic process. Previously, my biggest social-media-based election concerns might have been whether to unfollow my local member (and his incessant parking meter posts) on Facebook, or if I should post a picture of my ballot sheet that listed Meow-Ludo Disco Gamma Meow-Meow as a candidate (I did). Now, they’re more along the lines of whether my accounts have (undoubtedly) been exposed to foreign interference and fake news. These concepts are not new but, like many others prior to 2016, I was still riding the optimistic high of social media’s democratic potential, unaware of the dark world of algorithms, data breaches, and filter bubbles that lurked beneath. As stated in a 2017 leading story in The Economist – “Facebook, Google and Twitter were supposed to improve politics. Something has gone very wrong” (The Economist 2017).

youtube

A couple of nights ago I went to see Hillary Clinton speak. When asked what she believed influenced the outcome of that November 2016 night, her response was clear – her fate was sealed by social media. In a presidential race that earned “fake news” and “alternative facts” places in our vernacular, the unsuspecting digital citizenry was bombarded with political bias, unprecedented vitriol, and highly unconventional campaign social strategies. Even Trump himself has declared that he probably wouldn’t be where he is had it not been for Twitter (Factba.se 2017). Circumventing traditional media outlets, Trump led a one-man Twitter campaign. Policy, attacks on other candidates, and self-praise came tumbling out in bizarre late night Twitter tirades, controlling the mainstream news of the day with perfectly timed distractions. When asked how he would change his social media behaviour upon being sworn in he responded "I'm going to do very restrained. If I use it at all, I’m going to be very restrained.” (Firozi 2016). I’ll just leave these here.

The biggest threat, however, comes from the influence we cannot see. Facebook has admitted that between January 2015 and August 2017, 146m users may have been exposed to Russian backed misinformation across its platform (The Economist 2017). Additionally, the data of 87 users was accessed by big data firm Cambridge Analytica in an effort to deliver targeted political bias to Facebook users (Solon 2018). The danger lies in the fact that social media platforms are increasingly being treated as news sources (Tucker et al. 2017, p. 49), a trend that is particularly rampant amongst those who are “headline-checkers” (Young 2010, p. 218). The UI of social media platforms, combined with our “attention economy”, ensures that fake news travels fast and largely unchallenged (The Economist 2017; Tucker et al. 2017, p. 54), using so-called filter bubbles to keep us safe inside our like-minded microcosms. To step outside the filter bubble is to be confronted with an anger and moral outrage that seems to multiply on the internet, amplifying divisions that have long existed, and giving voice to partisans that were previously sidelined. Civilised discussion seems to have no home on our feeds - “Facebook is where you go to be outraged among people who are outraged by the same things; Twitter is where you take your outrage to the enemy” (Williams 2017). In the months surrounding November 2016, I witnessed many a post implosion, as people seemed to forget about general niceties, going straight for the throat at the first mention of politics. Magnified by this concept of everybody having a voice on social media, these disputes moved offline, making for many an awkward thanksgiving dinner in my own friendship circle.

Whilst the events of 2016 (unfortunately) cannot be undone, I at least hope that they serve as an example of how not to use the internet. The attention that has been brought to privacy and authenticity concerns on social media has offered an opportunity for individuals and corporations alike to take stock of their own practices – and maybe untick a few boxes in their Facebook settings. Perhaps if we spend as much time investigating sources as we do screaming at each other on the internet, there may be hope for us yet. As Hillary told us the other night - “we need to make social media work for democracy”.

References

Factba.se 2017, Fox News: Tucker Carlson Interviews Donald Trump - March 15, 2017, Factba.se, viewed 10 May 2018, <https://factba.se/transcript/donald-trump-interview-fox-march-15-2017>.

Firozi, P 2016, 'Trump vows to be 'very restrained' with Twitter as president', The Hill, 11 December 2016, Available at <http://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/presidential-races/305747-trump-vows-to-be-very-restrained-with-twitter-as> (Accessed 10 May 2016).

Solon, O 2018, 'Facebook says Cambridge Analytica may have gained 37m more users' data', The Guardian, 5 April 2018, Available at <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/apr/04/facebook-cambridge-analytica-user-data-latest-more-than-thought> (Accessed 10 May 2018).

The Economist 2017, 'Do social media threaten democracy?', The Economist, Nov 4, Available at <https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21730871-facebook-google-and-twitter-were-supposed-save-politics-good-information-drove-out> (Accessed 4 May 2018).

Tucker, JA, Theocharis, Y, Roberts, ME & Barberá, P 2017, 'From Liberation to Turmoil: Social Media and Democracy', Journal of Democracy, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 46-49.

Williams, Z 2017, 'We are all angry on social media - at least try to listen to the rage of others', The Guardian, 9 October 2017, Available at <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/oct/09/angry-social-media-facebook-twitter-silicon-valley> (Accessed 10 May 2018).

Young, S 2010, How Australia Decides: Election Reporting and the Media, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Images and video

‘Bruce Plante Cartoon: Trump and Twitter’ 2017 [image], Bruce Plante, Tulsa World, viewed 10 May 2018, <http://editorialcartoonists.com/cartoon/display.cfm/161817>.

‘How social media helped weaponise Donald Trump’s election campaign’ 2017 [video], Planet America, ABC News Australia, viewed 11 May 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6VFTCwKLlgg>.

‘Outcome of political arguments meme’ 2016 [image], Me.me, viewed 10 May 2018, <https://me.me/i/outcome-of-political-arguments-on-facebook-you-change-your-mind-2911634>.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Our Public Private Lives

It seems our days of prolific brunch documentation and oversharing shan’t be behind us anytime soon. A 2015 survey found that the average online individual actively uses 2.82 social media platforms – 5.54 accounts per person and rising (Mander 2015). Collectively, we share 95 million photos and videos on Instagram every day (Osman 2018), creating a never-ending feed of selfies, puppies, meals, and sunsets. Social media has become an essential tool of social self-formation (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292), serving our longing to connect with others, whilst fuelling our relentless need to share every detail of our lives.

youtube

Perhaps the greatest affordance of the reign of social media is our ability to customise our lives. Producing our own content means that we are in control of how our profiles, or our lives as seen by cyberspace, appear (Siapera 2012, p. 198). All aspects of our online existence are malleable, from our friendship circles to our interests and affiliations, where this data can then be used to track down other individuals of similar circumstance, wherever they may be. This “networked individualism” removes us from geographical constraints, allowing us to form “communities of choice”, and extending the reach of our content to a global audience (Siapera 2012, p. 199). Our levels of openness, as well as our negotiated online appearances, can be altered to fit our audiences (van der Nagel 2013), raising the question of whether there is a clear distinction in this modern world between what is public and what is private.

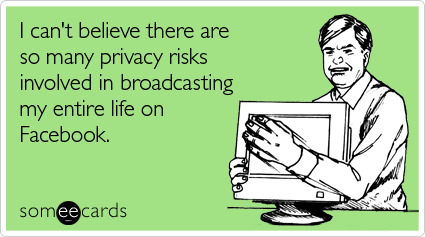

As social media usage continues to climb, so do our levels of public exposure and self-disclosure (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292). Feeling the pressures of the constant drive to produce content, many seem to believe that broadcasting everything from the traffic they’ve encountered to their workout schedules is appropriate in the social media sphere. But are we engaging in this behaviour to feel connected to others or for fear of ceasing to exist if we fail to participate (Siapera 2012, p. 205)? The term “Facebook official” has become part of our vernacular, implying that if it has not been posted to social media, and thus broadcast to the world, then it isn’t real. Disagreements and grievances are being taken online, whether it be for convenience or to share our experiences with the masses. An entire generation of social media influencers have been born, encouraging people to participate in real-world activities just “for the gram”, and the perceived social validation that comes with an influx of likes and followers. In this strange new world of publicness, it seems that the more you are perceived to share with the world, perhaps the more private you can be as your audience assumes transparency (boyd 2012, p. 76).

Issues of online privacy have been brought to the forefront recently, as our personal data is increasingly harvested, sold, and then thrown back at us for manipulation. Our incessant desire to share products we like, political affiliations, and our locations with our social networks has meant that not only can our online shopping experiences and advertisements be personalised and targeted, but so can the news and political dialogue we are exposed to. Social media platforms are perhaps the biggest offenders in the undisclosed sharing of data, to the extent that this past week, Mark Zuckerberg has been giving congressional testimony. But isn’t it ironic that we are so horrified by the concept of our personal data being breached when, really, it’s only available for corporate use due to our own willingness to broadcast it?

References

boyd, d 2012, 'Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle', in M Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, New York, pp. 71-76.

College Humour, Look at this Instagram (Nickelback Parody), 10 December 2012, viewed 13 April 2018, <https://youtu.be/Nn-dD-QKYN4>.

Mander, J 2015, Chart of the Day: Internet Users Have Average of 5.54 Social Media Accounts, Global Web Index, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://blog.globalwebindex.com/chart-of-the-day/internet-users-have-average-of-5-54-social-media-accounts/>.

McCosker, A & Wilken, R 2014, 'Social Selves', in S Cunningham and S Turnbull (eds), The media & communications in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 291-295.

Osman, M 2018, 18 Instagram Stats Every Marketer Should Know for 2018, Sprout Social, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://sproutsocial.com/insights/instagram-stats/>.

Siapera, E 2012, 'Socialities and social media', in Understanding new media, SAGE, London, pp. 191-208.

Images

'Daily Cartoon: Thursday, November 9th' 2017 [image], Farley Katz, New Yorker, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/cartoons/daily-cartoon/thursday-november-9th-marathon-forest>.

'I can’t believe there are so many...' [image], Someecards, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://www.someecards.com/cry-for-help-cards/i-cant-believe-there-are-so-many-privacy-risks-involved-in-broadcasting-my-entire-life-on-facebook/>.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s take this online.

Technology is pervasive. As the availability of portable devices, in conjunction with network bandwidth, becomes greater, so does our need for it to be accessible at all times. A Nokia “brick phone” once sat comfortably in your back pocket, but an iPhone’s preferred location is glued firmly to your hand, contact breaking only to eat (if necessary) and shower (for now).

We are in a state of perpetual connectedness (boyd 2012, p. 72), driven by a need to stay on the proverbial ball, and an insatiable thirst for information. With this constant state of connection comes a constant need to be present –but not in the ways we once were. We no longer need to be in the same office to be colleagues, and no longer need to actively reach out to maintain friendships. Concepts of time and space have transformed, taking our relationships with friends and family online, lifting boundaries previously enforced by distance, and changing our ideas about how and when we should be communicating (Siapera 2012, p. 191).

With the birth of social platforms, came the ability to publish the infinite details of our lives for the masses, to connect with people we know, those we used to know, and those we never would have crossed paths with otherwise (Murthy 2012, p. 9; Siapera 2012, p. 202). We can now stay up-to-date on our cousins’ vacations, participate in book clubs, and be active members of grassroots movements, simultaneously and all from the comfort of our own couches. Does this mean we are destined to become social recluses, misguided in our beliefs that we are interacting whilst wasting away from loneliness (TED-Ed 2013), or is it time to renegotiate what it means to be socially engaged?

Technology has broken down our social conventions, transforming them, and the possibilities are endless (boyd 2012, p. 75). It’s not about having the latest and greatest devices though, it’s about bettering our abilities to connect with people and information – our universal need to associate with others (boyd 2012, p. 73; Siapera 2012, p. 192). Being an accepted, useful member of a community is still important to us, but time is scarce and connecting with those geographically close-by somehow requires more effort than engaging with people anywhere on earth. Rather than being constrained to communicating with those who share a locality, we now seek to be grouped with those who share our interests and beliefs (Siapera 2012, p. 194), wherever they may be, in infinite, always “on”, digital communities.

Whilst the implications of these new communities are far-reaching and fluid, opening a whole realm of questions we don’t always have answers to (am I digging myself into a narrow-minded grave? did it even happen if it’s not on Instagram? did my Facebook data somehow get Trump elected???), I believe the positives far outweigh the negatives. The world is more connected than ever before. Instantly catching up with loved ones far and wide just requires decent network service. Any information we’ve ever dreamed of knowing (sometimes to be taken with a grain of salt) is literally at our fingertips. And if you’re ever feeling lonely, just write a status about it!

References

boyd, d 2012, 'Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle', in M Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, New York, pp. 71-76.

Murthy, D 2012, Social Communication in the Twitter Age, Wiley, Oxford.

Siapera, E 2012, 'Socialities and social media', in Understanding new media, SAGE, London, pp. 191-208.

TED-Ed 2013, Connected, but alone?- Sherry Turkle, viewed 14 March 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rv0g8TsnA6c>.

Images

'A man and woman talk at the bar' 2013 [image], Liam Walsh, New Yorker, viewed 14 April 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/explain-yourself-liam-walsh-cartoonist>.

4 notes

·

View notes