Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

One of the things that’s really struck me while rereading the Lord of the Rings–knowing much more about Tolkien than I did the last time I read it–is how individual a story it is.

We tend to think of it as a genre story now, I think–because it’s so good, and so unprecedented, that Tolkien accidentally inspired a whole new fantasy culture, which is kind of hilarious. Wanting to “write like Tolkien,” I think, is generally seen as “writing an Epic Fantasy Universe with invented races and geography and history and languages, world-saving quests and dragons and kings.” But… But…

Here’s the thing. I don’t think those elements are at all what make The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings so good. Because I’m realizing, as I did not realize when I was a kid, that Tolkien didn’t use those elements because they’re somehow inherently better than other things. He used them purely because they were what he liked and what he knew.

The Shire exists because he was an Englishman who partially grew up in, and loved, the British countryside, and Hobbits are born out of his very English, very traditionalist values. Tom Bombadil was one of his kids’ toys that he had already invented stories about and then incorporated into Middle-Earth. He wrote about elves and dwarves because he knew elves and dwarves from the old literature/mythology that he’d made his career. The Rohirrim are an expression of the ancient cultures he studied. There are a half-dozen invented languages in Middle-Earth because he was a linguist. The themes of war and loss and corruption were important to him, and were things he knew intimately, because of the point in history during which he lived; and all the morality of the stories, the grace and humility and hope-in-despair, was an expression of his Catholic faith.

J. R. R. Tolkien created an incredible, beautiful, unparalleled world not specifically by writing about elves and dwarves and linguistics, but by embracing all of his strengths and loves and all the things he best understood, and writing about them with all of his skill and talent. The fact that those things happened to be elves and dwarves and linguistics is what makes Middle-Earth Middle-Earth; but it is not what makes Middle-Earth good.

What makes it good is that every element that went into it was an element J. R. R. Tolkien knew and loved and understood. He brought it out of his scholarship and hobbies and life experience and ideals, and he wrote the story no one else could have written… And did it so well that other people have been trying to write it ever since.

So… I think, if we really want to write like Tolkien (as I do), we shouldn’t specifically be trying to write like linguists, or historical experts, or veterans, or or or… We should try to write like people who’ve gathered all their favorite and most important things together, and are playing with the stuff those things are made of just for the joy of it. We need to write like ourselves.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

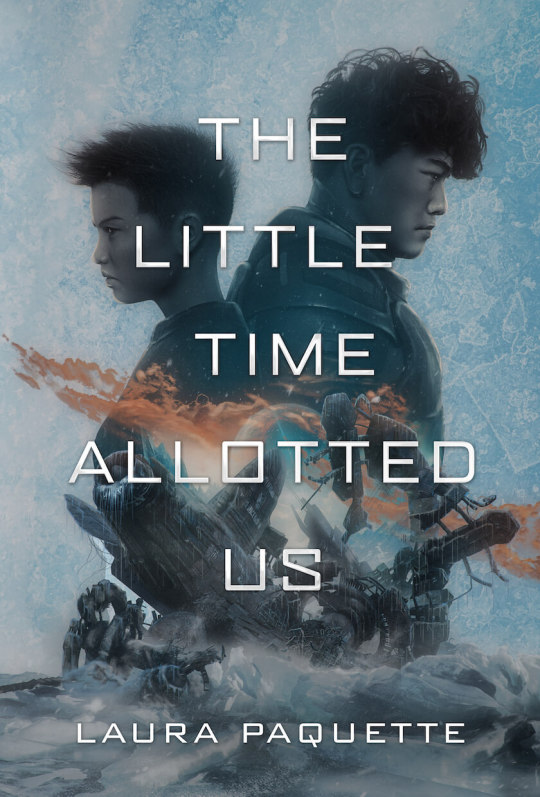

Book Launch!

So, I'm far from home and too busy to properly celebrate, but my sci-fi novel, The Little Time Allotted Us, came out today. It's sort of niche, a little cerebral at times, with a lot of dark humor spread out, but i did get a five star review, so I know someone's enjoyed it. I hope you enjoy! It's free on kindle unlimited, but if you don't like Amazon, you can get it on barnes and nobles.

0 notes

Text

Hey all! I've been lurking around the site for years, so it's time to put something out. My novella, The Pre-Corpse and Mortician, comes out on March 12th, but you can get it free if you subscribe to my newsletter at my website. I send out free sci-fi or fantasy stories once a month. Hope you enjoy!

0 notes

Text

u ever see someone with extremely fucked up views (or actions) and think wowww if a couple of things in my life went the tiniest bit differently that would have been me

104K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Write about what really interests you, whether it is real things or imaginary things, and nothing else.”

— C. S. Lewis

592 notes

·

View notes

Text

J. R. R. Tolkien, undisputedly a most fluent speaker of this language, was criticized in his day for indulging his juvenile whim of writing fantasy, which was then considered—as it still is in many quarters— an inferior form of literature and disdained as mere “escapism.” “Of course it is escapist,” he cried. “That is its glory! When a soldier is a prisoner of war it is his duty to escape—and take as many with him as he can.” He went on to explain, “The moneylenders, the knownothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as possible."

Stephen R. Lawhead

54K notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't you sometimes get an absolutely extrodinary, mind blowing, such an awesome idea for a story, but you just don't have enough skill level to pull it off?

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

I find it personally offensive how many bad writers can get published so easily.

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

So I launched a blog breaking down awesome books, writing craft, and the intersection of literature and philosophy. The first article explores how books can be true, and what it means for us as authors. Enjoy!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I'm at that section and she also cries because it'll take her a while to get gray hair

sometimes i think, as readers we exaggerate nynaeve’s drama-queen antics but then i remember that she started crying in the middle of the street after she and elayne survived a kidnapping attempt because she realized that mat was right all along and she’d have to accept his help and elayne, sweet sweet elayne who was probably concussed was like ‘hush nynaeve, its gonna be ok. mat cant be that bad!’ which only made nynaeve sob even harder. she is hysterical. sorry to the people who hate joy but i never, ever stop laughing when i read her chapters.

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

It convinced me to go out and buy the first three books. There were some parts that seemed cheesy, but I liked the epic scale of it and it's an older work so it would be different from my normal reads.

I DESPERATELY want reactions from people about the Wheel of Time teaser who have never so much as glanced at one of the books tbh

like I wanna know what normal people think of it

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really didn't like her in the first book, but she gets better and balanced out by other POV female characters in the next book

I’m reading the first book in the Demon Cycle by Peter V Brett and I’m beginning to remember why I don’t read a lot of dark fantasy written by male authors.

The first part focusing on Arlen was great, but then the POV switched to Leesha and ooooh no.

She’s a 13 year old girl, and she constantly goes on and on about wanting to get her period so she can get married and have kids. All her and her friends seem to talk and think about is having sex and giving their future husbands babies and I just want to scream.

Admittedly, I haven’t finished the book yet. Maybe she’ll go through a bunch of character development and become a fully realised character. I hope so, but if what I’ve heard about this series is correct (mainly the islamophobia) then I don’t have high hopes.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eysenck’s PEN Personality Model

Overview

Personality here is defined as a “pattern of deeply embedded psychological characteristics” that are not easily changed, and that express themselves “automatically in almost every facet of functioning” (5). Eysenck believed that personality was more than observable behavior, but permeated our subconscious, and accounts for the differences between individuals. Because according to Eysenck personality is seated within biological factors and genetics and other 'natural factors', environmental and social pressures and other ‘nurture’ type factors are less important. Because personality is biology dependent, he believed that even vermin like rats had them.

Eysenck uses three dimensions or traits to characterize personality; a trait here is an aspect of personality that is relatively consistent and therefore predictable. This trait theory wasn’t particularly original, the ancient Greeks had a similar idea, and medieval Europeans had their theory of four humors, which they also tied to biology. Nor is this the end all theory of personality traits today, there are other competing models such as the Five Trait Model. However, Eysenck was one of the first to try and use empirical data in concordance with the trait theory.

Eysench’s research was done using factor analysis, a process of allowing the subject to rate themselves on a trait, such as an extroverted personal rating themselves as outgoing. Obviously, this could lead to problems as it relies on accurate self-reflection. This methodology puts him in the idiographic view (rather than the nomothetic view), which assumes that each person has a “unique pyschological structure and that some traits are possessed by only one person and that there are times when it is impossible to compare one person with others” (3).

Eysenck himself was an impressive man. He was born in Germany in 1916, raised by his grandmother after his parent’s divorce, and fled Germany at 18 because he was in danger for sympathizing with the Jewish people. During World War II, he was a psychologist at an emergency hospital where he questioned the reliability of psychiatric diagnoses, resulting in a life-long feud with main-stream clinical-psychology. This was where he compiled his behavioral questionnaire in order to give a preliminary diagnosis, and as a result, produced his PEN theory.

He became a professor at the University of London. He wrote over 75 books and 700 articles, writing till his death in 1997. At his death, he was the most cited author in psychology journals.

Specifics:

Eysenck’s identified traits are: Neuroticism (N), Extraversion (E), and Pyschoticism (P). Neuroticism is stability, as opposed to anxiety. Extraversion ranges from being outgoing and sociable to being introverted and withdrawn. Pychoticism isn’t necessarily a psychotic break but rather displaying emotions extremely or inappropriately as well as having a general antipathy toward social convention or manners.

The name ‘neuroticism’ comes from nervous disorders called neuroses, hence neuroticism refers to how extensively one suffers anxiety or nervousness. Having a high neurotic score doesn’t necessarily mean being neurotic, but means being more susceptible to those sorts of conditions (this is one of the criticisms of the theory, giving relatively ‘normal’ people abnormal labels). Not only are people with neuroticism more easily startled, but they require more time to come down from their reaction.

Eysenck believed that this dimension is rooted in the sympathetic nervous system. If someone had an overactive, more responsive sympathetic nervous system, they are more likely to get a panic attack, or display other neurotic symptoms. The sympathetic nervous system controls our emotional reaction to emergency situations, releasing adrenaline, opening the pupils, or giving goosebumps. By initiating this process, the body believes it’s in danger and so continues to intensify the physical aspects of panic, creating a downward spiral of amplifying fear.

The extraverted-introversion spectrum is fairly mainstream today, although it can have slightly different meanings in different contexts, and tends to be exaggerated. Here, it’s used to measure social inhibition and excitation. Inhibition is the brain resting or protecting itself from overwhelming simulation, whereas excitation is the brain preparing or waking up. According to Eysenck, the extravert has strong inhibition; if they witness a trauma or other overwhelming phenomena, they’ll shut down and go numb and should recover quickly. This allows them to be more sociable and optimistic, however they can be less responsible. The introvert will feel like they see the trauma in slow motion, and need to take longer to recover. This is what makes in the introvert more cautious in social situations, they remember their past fiascos and are able to both learn from them and over-analyze them, while the extrovert can shrug embarrassments off. Introversion then can tends to lead to pessimism, however it’s also linked to reliability as the consequences of their actions are more easily recognized.

The third dimension, psychoticism, was a result of Eysenck’s research within English mental institutions. This includes a proclivity toward risk-taking, a disregard to common sense or social convention, and inappropriate emotional expression. Biologically, Eysenck linked it to higher testosterone levels. However, there’s been considerable pushback against the designation of this trait, and some have replaced this one dimension with three, Insensitivity, Orderliness, and Absorption. This adaption brings the PEN theory closer to its contemporaries, but also orphans it from Eysenck’s emphasis on biological reactions.

There are several critiques of the theory, or even the concept of personality psychology in general; depending on the definition of ‘observe’ personality may be impossible to observe, and thus would be outside the scope of the scientific method. Others argue that Eysenck doesn’t weigh in environmental condition enough; someone who had been abused as a child for instance might appear introverted, whereas their natural self might have been extroverted if not for their trauma. There’s also a critique of wording, as in this model, traits like ‘psychoticism’ can be overused. Eysenck himself didn’t seem entirely satisfied either, since he wasn’t convinced that traits were fixed for all time; certain aspects of biology are malleable, so personality could be one of them.

Why It Matters

Eysenck’s PEN theory is often used to study risky or criminal behavior. Typically, people with low neuroticism and high extroversion are more likely to engage in risks, including crime. Which makes sense, no one is going to mug someone if they get a panic attack when they hold a weapon. However, that doesn’t mean that introvert or those with high neuroticism have an advantage, they are also more likely to suffer anxiety or related conditions. Even high psychoticism—or at least, some aspect of it—doesn’t have to be a bad thing; Eysenck himself frequently clashed with established authority, from the German government to respected British psychologists.

An interesting aspect of the PEN theory is that people have different biological reactions to danger. This doesn’t necessarily mean that some people are programmed to be brave so that their courage means nothing, or that some people are doomed to be cowards, but it could give a more plausible reason for certain people not having as strong a reaction to tragedy, or contrast a character's choices with their physical reaction.

The PEN theory also allows for a wide variety of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ characters. A more socially cautious character can be wiser and responsible, or manipulative or apathetic to others. A more neurotic character can be clever or cowardly. A character with high pyschoticism can be a Byronic hero that plays by their own rules no matter what society says, or they can be a selfish brat that just does whatever they want. Moreover, by playing up the biological underpinning of these traits, you can create more tension as a character tries to break free from their biological destiny. The whole concept of factor analysis or characters self-identifying with some traits could be fun to play with, balancing who people believe they are with who they are.

There are a few sample tests you can take online, this one doesn't store your data or anything creepy like that: https://www.idrlabs.com/pen-personality/test.php.

1. https://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/eysenck.html

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2858518/

3. https://www.simplypsychology.org/personality-theories.html

4. http://www.personalityresearch.org/pen.html

5. https://www.ukessays.com/essays/psychology/critical-evaluation-of-eysencks-theory.php

6. https://www.psychologistworld.com/personality/pen-model-personality-eysenck

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Farming

Overview:

Nowadays, we mostly remember Rome for her republic declining into an empire, or her military prowess. However, Romans thought of themselves as peace-loving, and even violent figures such as Sulla or Pompey the Great retired (temporarily, in Pompey’s case) from public life to their farm, as did the idealized Cincinnatus. Festivals celebrated farming holidays, art depicts farming tools, and noble gentlemen wrote farming manuals. Perhaps this was because the Romans rarely had a hard time providing food for themselves, their own land was fertile, and as the empire expanded they were fed by north African farms, or perhaps it was because the city of Rome was started as a little military outpost to protect Italian farmers from their northern Etruscan neighbors.

Because farming was so idealized, it’s a difficult subject to cover extensively, I’m going to highlight some practices, inventions, and produce that could add realism to historical fiction or fantasy as well as distinguish it from the typical fantasy landscape, then go into some of the cultural implications (besides people having better things to do than starve to death).

Specifics:

Even if farming was an appropriate side hustle for patrician nobility, farming itself was difficult, and it yielded far less than it does now. Nearly half of the crop had to be used as seeds. Even still, Romans farmed so well that their farming methods were picked up by Britains and Gauls, which is appropriate since Romans built off efforts by the Greeks and people of the Near East. Additionally, despite the difficulties of the ancient world, the period between 500 BC and 500 AD had peak farming conditions in Europe (as opposed to the mini Ice Age that followed). Italy had other farming advantages; although rainfall can be spotty at times, it’s normally abundant, there are plenty of rivers and streams, and the soil is rich from volcanic ash.

The Romans grew wheat, spelt, barley, legumes like peans, peas, chickpeas, alfalfa, turnips, radishes, and fruit like figs. Wild fruits and nuts could be collected at will. Grapes and olive oil were popular and sold abundantly—both grow naturally in Italy—and with grain were the most important plants, sometimes called the “Mediterranean triad” (2). Though olive and grapes could be grown with little effort, grain—around 75% of a normal person’s calories—required extensive effort. Moreover, early Roman holdings were often as small as 1.25 acres or half a hectares. Normally, 1 acre will feed one person.

Because there’s a large difference in the temperature and rainfall in north and south Italy, there’s a good bit of variance in farming method. However, we can get the idea in broad strokes. Roman tools were bronze or iron, hand tools like hoes and mattocks, plows (with a forecarriage—an apparatus at the front that makes it steadier), carts, harrow, manure hampers and baskets, spades, shovels, rakes, scythes, axes, wedges, an olive-crushing mill and oil press.

The plow was used first to turn soil over, as it is now, and could invert soil if turned sideways; some plows had metal ‘ears’ on the bottom that improved them. In light soil it could be pulled by a donkey, otherwise, it might require a few oxen. That was followed with a mattock (which looks like a cross between a pick-axe and a wood-axe), which broke up large lumps of dirt so that the seeds could fall into the proper rows the plow had turned up. Fields were plowed at least twice to conserve moisture (called cry-farming, still a staple around the Mediterranean), and manure was laid down after the second plowing, which came from a compost pit with animal excrement and rotting leaves, weeds, or leftovers. Seeds were either thrown out (which is quicker), or placed by hand. They were then raked over with a harrow, which could be a tool with iron teeth like nails raking the ground, or a convenient thorn bush.

Harvesting was done with a sickle (curvy knife on a stick that looks like a bad guy’s weapon), which has changed little since then, and was then brought to the threshing floor. Threshing was done by animals stomping on the grain on a hard floor, or by being crushed by a tribulum, or wooden frame with metal on its belly which was pulled across the floor. Winnowing was done by tossing the threshed grain and letting the light chaff blow away while the heavier grain well back down. Grain was then usually ground with rocks, although there were some working water mills at the end of the empire.

On rainy days when not much farming could get done, Cato (one of the politicians writing farm manuals) says to make sure to remind the overseer of work that could be done “scrubbing and pitching wine vats, cleaning the farmstead, shifting grain, hauling out manure, making a manure pit, cleaning seed, mending old harness and making new; and that the hands ought to have mended their smocks and hoods. Remind him, also, that on feast days old ditches might have been cleaned, road work done, brambles cut, the garden spaded, a meadow cleared, faggots bundled, thorns rooted out, spelt ground, and general cleaning done.” (4)

Although vineyards and olive groves remained unchanging, the Romans realized that they couldn’t grow the same crop the same place forever as it depletes the soil, so they divided their fields and rotated crops between them. They also identified which soil was best for which plant, and paid attention to that as they were cordoning off sections; for instance, olives were to be planted in thinner soil and exposed to the sun, at intervals of twenty five feet. Forage crops were also planted, such as alfalfa, which also aided the farm animal’s fertility. Vegetables were also grown to supplement human and beast, though farmers would also forage for acorns or other foodstuff to feed their animals through winter.

To offset the dangers of a poor year, in the good year, farmers stored as much as they could—not just food, but animals and jewelry that could be sold. People also used each other as resources; when one person helped another, the person helped incurred an obligation to return the favor.

Certain plants were also grown for medicinal purposes: Pliny reports that garlic had 61 medicinal uses, radish 43, and lettuce 42. Parsnip relaxed the stomach and relieved swelling when used as a bandage, the onion’s juice was used to relieve pain from snake bites, the wild cucumber’s juice was used for tooth aches and to heal eyes, beets were boiled and eaten with raw garlic to cure tapeworm.

Farming evolved as Rome did. Initially, it was a family thing, with that small acre and change farm earlier described. However, as Rome grew and the need for soldiers increased, Rome turned to conscription. Young men were pressed into military service, and while they were gone those rich off of conquests bought up land that couldn’t be maintained without the citizen farmer, and used captured slaves as free labor. These slave run estates were so common, there was even a name for them, the latifundia. These latifundia undercut the family farm and forced the rural people to the city, where they struggled to find work and depended on the empire’s bread and circuses. However, this theory has come under fire recently from new archeology evidence which doesn’t seem to support a decrease in small farms, yet even if it wasn’t true, it was the narrative the poor Romans told themselves. Regardless, it is verifiably true that as the empire expanded, it depended more and more on fertile North Africa, such as Egypt, Tunisia (where Carthage was), and Algeria, as well as their own islands Sicily and Sardinia.

Why It Matters:

We can see a tension between Rome as it was originally, a farming outpost, and the military empire it became in Cato, who has nothing but praise for farmers, but still draws them from their farm claiming that they make the sturdiest soldiers. More subtly, in the Aeneid, Aeneas’ father Anchises tells him it’s the Roman legacy to conquer, and yet the author Virgil spends more time on the domestic scene, in romance and familiar love, than battle. Seeing as no culture can live up to its ideals (unless they have lame ideals like flaying people *cough* Assyrians), a good fantasy culture will have both what it wants to be, and what it is. Sometimes those two are even in conflict with each other, or ideas mutate without the (sophisticated, fancy smancy part of) culture realizing or noticing the difference. Moreover, even if you want to cast a nation as ‘the bad guys’ they’ve got good motivations; Roman expansion was initially defensive, or honoring treaties with allies.

We can also see that cultures love their origins. Rome seemed to be more proud of their agrarian roots, than of their military prowess, which they actually seemed almost ashamed of early in their history (the ‘victory arch’ began as a sort of atonement ceremony where soldiers had to purify themselves before entering the city). Which is why we see houses in the city decorating their houses with natural scenes rather than scenes of battle, so that they can pretend they were proper Roman farmers.

As always, the technical details can help with realism.

1. https://www.britannica.com/topic/agriculture/Improvements-in-agriculture-in-the-West-200-bce-to-1600-ce

2. https://facultystaff.richmond.edu/~wstevens/history331texts/farming.html

3. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah20007

4. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cato/De_Agricultura/A*.html (Cato’s On Agriculture)

5. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Plin.+Nat.+toc&redirect=true (Pliny’s Natural Histories)

6. http://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub408/item2049.html

#writingfantasy #worldbuilding #writingtips #ancientworld

1 note

·

View note

Text

Attachment Theory

Without further adieu, the first psych installment of my grounded fantasy series (which I’m fangirling over like a dork):

In attachment theory, the child is constantly checking if the primary caregiver is close, available, and attentive. If they are, the child feels secure, and behaves normally, playing, exploring, and interacting with other children. If not, the child experiences anxiety and distress, and responds by seeking and summoning the caregiver until they return or the child gives up.

Attachment theory was proposed by John Bowlby in 1958 after he had served as a psychiatrist in London treating children. He observed their behavior and noted that the children who’d been separated from their mother showed emotional distress even when their physical needs were meet, such as crying when they were fed by other caregivers. However, Bowlby still believed the strong attachment between the mother and the child was survivalist in nature because the mother had first fed the child, so she was associated with safety.

Attachment is defined here as a deep and enduring emotional bond that does not have to be reciprocal. This is different from ‘bonding’ which is a theory based off close skin-to-skin contact that has been largely discredited. Basically, attachment revolves around the parents’ response to the child when they feel threatened. This first attachment with the caregiver (the mother in John Bowlby’s original theory as he placed a strong emphasis on the mother due to her initially feeding the child) is believed to influence the rest of the child’s relationships, including those in their adult life. It can be considered a WEIRD theory (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) in origin and worldview, but has been empirically grounded and claims universality as one of its early proponents, Mary Ainsworth, conducted studies in Uganda.

Specifics:

The stages of attachment were studied by Rudolph Schaffer and Peggy Emerson in a 1964 study that studied 60 infants for the first 18 months of their life. The stages of the baby’s attachment were recorded in mother’s diaries and by monthly visits.

(0-6 wks) Asocial: Most stimuli, social or non-social, produce a favorable reaction.

(6 wks-7 months) Indiscriminate attachment: The infants show no preference to anyone, and just want constant attention. Around three months, the infant can recognize familiar faces, but still responds roughly equally to anyone.

(7-9 months) Specific Attachment: the infant shows special preference for a single person who is associated with protection and comfort, and unhappiness if separated from that person, while others may be regarded with fear or anxiety.

(10+ months) Multiple Attachments: the infant becomes increasingly independent and forms multiple attachments.

Mary Ainsworth classified children into types of attachments in a study done with year old infants who were repeatedly separated and reunited with their caregiver. About 60%, the securely attached, responded as Bowlby expected, with distress at the caregiver’s absence and joy at the return. About 20% or less, the anxious-resistant, were despondent at their caregiver’s absence, but this distress continued even when their caregiver returned, and these children even appeared to punish their caregiver for leaving (or maybe for making them human lab rats). The avoidant, about 20%, didn’t appear upset at their caregiver’s absence and turned to toys or other distractions (although biologically they showed signs of distress, such as elevated heart rate). These behaviors were modeled at home, with the securely attached able to trust that their needs would be met, whereas the anxious-resistant or avoidant could not always depend on their caregivers.

In 1987, researchers Hazan and Shaver explored the adult romantic connotations of initial attachment. Romantic behavior was studied as an attachment since similarly to the initial bond, it requires the partners to feel safe with the other is nearby, requires the partner to be responsive, involves intimate contact, and those involved show preoccupation with the other, and pay close attention to facial features and body language. If this is true, we’d expect to see secure, anxious-resistant, and avoidant bonds between adults in a romantic relationship. It also implies that adults consider one another desirable by the same standards they did as an infant: safety, attentiveness, and availability. Or, perhaps an adult would seek to replicate their initial relationship, for instance, someone who had a secure relationship would continue in a pattern of healthy relationships.

The theory of attachment has since been modified, with secure attachments, anxious-resistant (or insecure-resistant), and avoidant (or insecure-avoidant) remaining, but with the addition of insecure-disorganized. These are children who don’t easily fit into the other three categories because their response varies. At home, the secure know they can rely on their parents to provide responsible care. As adults, they’re willing to show displeasure or frustrations without punishing their partners. The insecure-resistant have experienced inconsistent or unpredictable behavior at home; this doesn’t have to abuse, this could also be an overwhelmed parent. This child responds by amplifying their behavior to showcase their displeasure and try to get the response they’re seeking. As adults, they tend to worry about their partner’s response or take their frustrations out on their partner. The insecure-avoidant have experienced ridicule, irritation, or rejection to their needs, and so avoid their caregiver when distressed. As adults, they may be unable to acknowledge their distress or isolate themselves. The insecure-disorganized are typically victims of abuse or unresolved trauma, and appear to be frightened or frightening or atypical sexualized behavior. This type of behavior is often linked to psychopathy, defiance disorders, or other issues.

Why It Matters:

Although unless you’re writing a very strange book you’re not going to say “my protagonist has a disorganized attachment,” but it’s still an interesting thing to know. Personally, I tend to group my character’s childhood into ‘good’ or ‘bad’ or ‘very bad,’ but it’s helpful to be more specific when crafting characters. Having variety also adds interest, instead of having three different pairs of abusive parents to traumatize your characters, in which case it starts to look like your world is populated by losers, you could have a character feel bad since his parents loved him but were young and didn’t know how to be parents, or a single parent who loved his daughter but had to work all the time.

Besides psychologically damaging your characters, you can use attachment theory to add complexity in character relationships. Mature characters will realize they have anger issues or tend to be clingy (even if they don’t know why), and so may try to overcompensate and seem aloof because they’re trying to give their friends space or may be a bit of a pushover because they’re constantly biting back their anger. Or, characters that behave normally in most of their relationships might have a sore spot in their relationship with their parents, children, or significant other that seems to come out of nowhere.

Or, if you get nothing else out of this, you can at least diagnose yourself and your friends.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment.html

http://labs.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/attachment.htm

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2724160/

http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins.pdf

https://www.pnas.org/content/115/45/11414

https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory

2 notes

·

View notes