>>>>>>>> This site traces the collective learning journey of the remote participants based in London during the Live Workshop in Berlin. Here we are recording the stories of different projects and places that we gather throughout the week. <<<<<<<<<

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Migration and Housing

Having an interest in social justice, migration and housing , I joined the program via DesincLive in London

During the course, I want to investigate different possibilities for the long-term housing of migrants. This involves researching structures with the architectural potential as well as questions of socio-cultural development.

During the visit, I will document a specific story of migration and housing in London, linked to the “Windrush generation” and the use of the Clapham South Deep-Level Shelter as a place of refuge.

I will have a reflective and reflexive summary of the projects of my peers, with an underlying thematic of solidarity in hardship as a transversal aspect of the different (inter)actions observed in London and Berlin. Those reflections will be embedded in the presentation when directly linked, and will also take the form of a stand alone chapter at the end of my presentation.

MY VISIT ON THURSDAY JULY the 1st

I planned the visit of the sites as following

Deep-Level Shelter at Clapham South. Credit photo Agnes Fouda

Here is a link to the (short version) video that I made of the site visit :

https://share.icloud.com/photos/01NAP4Oe866hFS3lBjYh3RYBQ#London

Why Clapham South Deep-Level Shelter?

The site piked my interest because it was home to the very first generation of the “Windrush migrants” who came to the UK from Jamaica in 1948, at the invitation of the British government aiming at solving the shortage of labour subsequent to the Second World War.

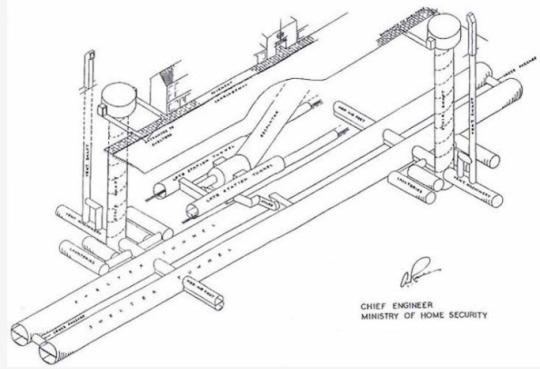

The site at Clapham South is not the only structure of the sort : there were in total 8 underground tunnels locations built as bomb shelters in London, but Clapham South is the one that became house per se to Windrush migrants. In 2016, it opened to the public as part of the TFL’ s hidden London tours, but is currently closed indeed because of Covid ; therefore I had to rely on the internet to find pictures of the inside :

Overview of the structure . Credit photo Transport Museum of London

Inside one of the tunnels. Credit photo Transport Museum of London

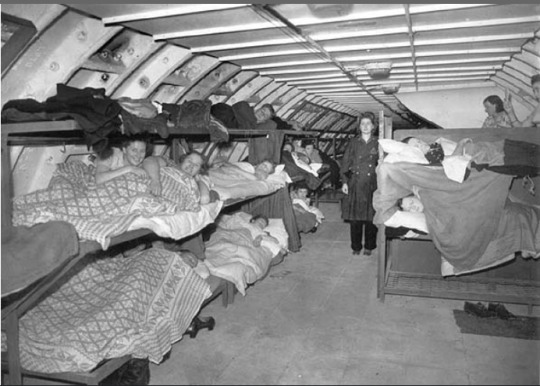

Residents shielding from the bombings inside the Shelter. Credit photo Wikimedia

The temporary measure put in place for the London population to shelter from the bombings became for the Windrush migrants a longer term solution . The parallel is easy to draw with today, as migrants and vulnerable populations of any background are often kept in so-called temporary accommodations (when it happens) for lenghty periods of time. An interlocutor from #Berlin mentioned incidentally that the question was raised before the authorities in charge, of the definition of temporary, given that migrants (and homeless for the matter) are staying in the #Marzahn shelters for many years in a row.

Furthermore, the current political sub-categorisation of migrants also affects the likeliness of accessing a shelter in the first place, let alone a hypothetical stable housing : indeed, a refugee, a stowaway, a “boza”, an undocumented, a documented-but-in-hardship migrant will have different rights and treatments, at least from the government. Could it be, therefore, a viable option to transform the temporary into more permanent by making the necessary changes, be it structural, architectural, cosmetic or administrative, or is my view too simplistic and naive?

By any means, living conditions in shelters are usually not ideal, neither were they at Clapham South in 1948. BBC’s Bethan Bell, in 2018, penned an account titled “Going underground: The Windrush arrivals' subterranean dormitories”. The article quotes a resident describing the accommodation as "primitive and unwelcoming, like a sparsely furnished rabbit's warren". Below is a link to the said article :

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-44483090

1948, three gentlemen from Jamaica settling in the Shelter. Credit photo Getty Images

Having tried to interrogate the very few (it was early morning) passers-by to no avail, I decided to set forth to visit the next site : the Black Cultural Archives located in Brixton.

The Black Cultural Archives (BCA) building in Windrush Square, Brixton. Credit photo Agnes Fouda

I wanted to find tangible documentation about the situation of the Windrush generation and their housing conditions back then and as of today. The BCA is a repository of their journey and narrative, and this aspect of legacy and preservation is also important when related to migration, precarity and displacement. The same preoccupation and urgency of preservation, I observed the day before at #Clitterhouse farm, and even though not related to migration nor housing per se, it has been implemented for the sake of a community which was about to be amputated of a significant historical landmark when the developers of the nearby Brent Cross shopping mall set forth to destroy the 14th century building. It is telling that in #makingthecity, historicity and cultural background are integral part of the comprehensiveness.

In addition to the Clapham South Deep-Level Shelter and the Black Cultural Archives, the site of the Stockwell Deep-Level Shelter was interesting for my investigation. Therefore, I added a virtual visit via a Youtube video link which I found on the channel :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fq-ofhGwS6c&list=RDCMUCMB8HFoi_QUoGsoRRHyZGAQ&start_radio=1&rv=fq-ofhGwS6c&t=149&t=149

(The mark for the Stockwell Deep-Level Shelter is at 2:33.)

The significance of it is that the Deep-Level Shelter at Stockwell is now used as an archive ; it also stands out due to the artwork that adorns it and the nearby first statue of a British African Lady. I thought, therefore, that it was a good way to liaise all the components of my topic by incorporating it to the visit, albeit virtually.

Stockwell Deep-Level Shelter. Credit Photo DAVID ILIFF. License: CC BY-SA 3.0" https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stockwell_Deep_Level_Shelter_Entrance_-_Diliff.jpg

The BCA

I met with #Santiago in front of the BCA building, and we both headed inside.

We first heard from “K” - at the front desk, a very knowledgeable gentleman who gave an in-depth context of the choice of Clapham South deep-level shelter : discrimination, says he, was the main reason, the migrants being unable to rent from the predominantly White Caucasians landlords.

Discrimination in the open back in the days. Credit photo Wikimedia

The government had no other choice than to use the facility for their housing until the newly arrived were able to find a place to live. An account from the BBC reports that within 4 weeks of their arrival, the Windrush migrants were able to get out of the shelter and find a more suitable place. I wanted to assess the affirmation, knowing that until before the Race Relations Act of 1965, it was common to find this :

So how were the migrants able to find work and housing? Are there reliable accounts to base an analysis on? Are there witnesses of the time still alive whom I can talk to? What has changed in terms of housing for that generation and their offspring? Has the housing discrimination totally disappear, what is going on exactly in that regard, do you still live at your parents’ and can we interview them?

Those were overwhelming questions for the receptionist who was about to finish his shift and leave, advising us to make an appointment with another person at a later time, but then something (un)expected happened.

Listening nearby and unbeknown to us was a Lady who then took the relay in the conversation. Santiago and I found ourselves soon interacting with her, Ms Assata Nzingha, who is a living archive on her own right. It was a stroke of luck and a high privilege.

Assata Nzingha (right) and this writer. Credit photo Santiago Poneyra.

Parts of our conversation here :

https://youtu.be/Rz5G6ASTZEs (video)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zghIVHNLTFM (audio)

In the video, we can hear that prior to obtaining a dedicated venue for their activities, the initiators of the Black Cultural Archives would take turn gathering in their houses. It is an occurrence in the migrant community that is not often observed within the practices of the locals ; the migrant house often serves as a circumstantial vector for the community needs. The variety of events that can be hosted in mirrors the fluidity and porosity of the relatives circle. Seldom abode to nuclear family, the house was considered primary as a tool or accessory for helping the peers. Only was it considered otherwise when a sustainable number of other migrants had been able to settle on their own - thus replicating the cycle anew. When she immigrated at 7 years old, Assata Nzingha’s father was the owner of 2 houses, one for his family , the other rented out. Who knows how many people were first welcome free of charge until Papa was able to morally afford to put a property for rental?

The audio is a very poor quality because we were sitting in the library and other visitors were talking. Grosso modo, I asked Ms Assata Nzingha why did Windrush generation settled in Brixton. She explained that it was a part of the city that was in a very bad state, with run-downed houses, and that it was subsequently the ones that the migrants at the time could afford. Doesn’t it ring a bell, Berlin and Milan?

I wonder what factors comes into play for the descendent of the Windrush generation when it comes to choose a place to live ; do they inherit the houses of their elders? Do they move out of the neighbourhood depending of their financial standing or social status? Also, how many of the Brixton homes are still owned by the very family of the original buyer? Those lines of inquiry might not get an answer right away but it would be interesting to know where, why and how the new generation of “Windrush” elect their place of abode, and how new housing models like Airbnb and Couchsurfing are playing in the field of migrant solidarity.

#Solidarity in hardship

An interesting point in the audio is the mention by Assata Nzingha of the #pardner that the migrants organised in order to buy properties in Brixton. It touches to the theme of #solidarity in hardship that I observed during the different visits.

Definition of a pardner by an online source : “In simple terms, a pardner is where a group of people pool their money together by handing over a set amount each week or month. ... The banker hands over all the contributions in a week or month, called the draw, to the person whose turn it is to get paid. Everyone usually joins at the start for a set period”.

This type of money handling is very much ingrained in the African tradition ; its importation and implementation as a coping mechanism to face the duress of #accesstohousing and #ownership is simply remarkable. It is one of the many ways that the migrant communities are actively supporting their own : #Santiago is pointing out that Elephant and Castle is a hub for real estate offers in Spanish aimed at the Latin American community. As it was before the demolition of the #Elephant and Castle market site, the phenomenon is very much alive to this day.

A Colombian store at Elephant & Castle. Credit photo Agnes Fouda

Above is one of the many businesses that Maha, Rowan and I visited with Santiago on the site of the redevelopment of Elephant and Castle. Distriandina is located in the Arches, selling delicious array of “productos”. While the main purpose is commercial, it also serves as a beacon of solidarity for the community. The Latin american population is quite numerous in London, and have settled mainly in the Elephant and castle vicinity ; after decades of harbouring an heterogeneous and vibrant universe of traders, the site was torn down in 2019 to make room for a new shopping mall. Faced with uncertainty regarding their relocation, the Latin american traders relied on the collective #Latinelephant to defend their interests before the stakeholders. While some traders have been allocated new business venues, others are still awaiting for a suitable offer. In cases like these, solidarity is vital for the survival of groups or individuals. From subletting a unit, or making room on the easement for a stall, traders have found a way to not let their people down. In term of housing, it would be interesting to investigate further the different ways of coping besides the ads, “anuncios”, encountered on the walls of the businesses, in the Spanish-written newspapers or other locations.

The #solidarity in hardship, I also witnessed it at #Clitterhouse farm during the visit organised by Maha. As mentioned before, it is not specifically related to the matter of migrant housing, however it is worthy and noticeable as a project of #inclusion, #solidarity,#perseverance. In effect, the building that hosts the #Clitterhousefarm project, is way more than what meets the eyes. When entering the premises, one is facing a huge field on the left - old training facility of the Hendon football club ; on the right, barely perceptible at the moment of entering, is a long bricked wall covered with images that blend into the surrounding vegetation; a few steps forward, a right turn and here are a big parking lot, and garden partially enclosed , all adjacent to the front facade which main entrance is concealed by a colourful MDF fence : the site, under construction, has been threatened by the Brent Cross redevelopment project that affects the neighbourhood and its surrounding. But, like the last Gaul village in Asterix, a group of defiant people has been fighting the invasion of developers, rallying overtime the support of the community at large.

The Clitterhouse farm. Credit photo Agnes Fouda

Maha has just indicated that there should be a cafe opening in the coming months. For now, the structure hosts Saturday family gatherings ; while pacing around, admiring the grass-roots garden and what I guess will serve as tables for the cafe, I cannot help but think that scores of old and abandoned buildings are awaiting to be, maybe, revived by hopeful cohorts of migrants, refugees or the homeless.

Paulette, one of the director of the collective #Ouryard, eventually came to greet us with a beautiful infant carried on her tummy. She led us along the aforementioned painted wall, retrieved a key and from there we fell into the rabbit hole. The backyard. Surprising, totally unexpected, big, cluttered and belonging to a tools repair businessman. #Maha and #Rowan will correct me, but Paulette explained that it is the said businessman who actually owns a leasehold to the premises, and that, because they are getting along - she has been able to negotiate and be granted, gratuitously at times, more space after more space to expand the #Clitterhousefarm project. The barter proves absolutely successful and is sticking with me as a definite model of good cohabitation in the prospect of #makingthecity.

Conversely and sadly, the principle of #solidarityinhardship is not universal nor automatic, as heard from S27 regarding the clashes between #homeless and #refugees in Marzahn. Yet both communities are supposed to share the same combat at least when it comes to housing. Why would some be shunned by the others, and vice versa? Is it the additional precarity that exacerbates the conflicts? Does a more stable housing situation quells the antagonising? Does solidarity rhymes only with same community? Those questions and many more , I would like to further explore. For now, I am happy and thankful that the workshop and projects have opened my eyes to details and considerations that might have not crossed my mind otherwise. One thing is certain, I shall never look at #London the same way as before.

A.F

0 notes

Photo

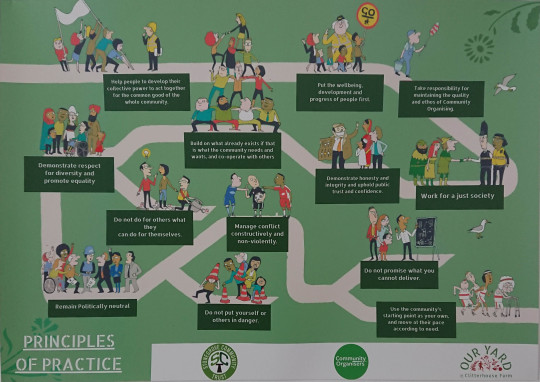

Picture : Community organising workshop day run by Our Yard social enterprise - Principles of practice

The role of the Architect in urban practices: Reflections

Throughout this week, I have been reflecting on the presence of the architect in different urban projects we have explored, how their skills could have been used more effectively, and how grass-root organisations have ‘filled in the gap’ to negotiate an alternative solution that is more inclusive and sensitive to the needs to local residents.

Clitterhouse Farm project: Brent Cross Development (Background information for the project can be found in this post)

The Our Yard social enterprise has had different engagements with the architects through their journey.

1) Initially, one of the main residents who came together to save the building from demolition was a professional architect and suggested 2013 Forgotten Spaces competition run be RIBA and the Mayor of London. The group did not win the competition but this process helped galvanise them towards a future vision for the site

2) In the early stages of the project an architect was hired on a fee earning basis to do small feasibility studies which were used to apply for funding. It was difficult to develop a strong collaboration because Our Yard had very limited financial resources at the time. It was also felt that they needed someone who was able to be actively involved without the limitation of a professional contract

3) Two architectural students from Central St. Martins spent time on the site engaging with users through craft workshops (clay tile / furniture building) and developed a future vision for the site.

4) The team have now issued a call to tender for professional architects to develop the future vision into a full design in collaboration with the architectural students.

Clearly, the momentum for this project has been fuelled by design; however, there are other strategies Our Yard group have utilised to resist the current development plans:

1)Organised formal objections to development’s planning application

2)Physical presence on site and creating collaborative relationship with current leaseholder of the land.

3)Giving space for resident initiated ideas to be tested (grub club / people’s theatre / allotment)

4) Extensive surveys and focus groups with local residents on what they want the space to be

5) Fundraised for an alternative vision –this enabled political backing from the mayor and a focus to the discussions with the developers

6) Incorporated into a limited company with charitable purposes helped increase their legitimacy

7) Negotiated with council and developer to build a collaborative partnership model for the redevelopment of the site

Latin Elephant: Elephant and Castle Market redevelopment (Background information for the project can be found in this post)

In contrast to Our Yard, the architect role in this development has been purely dictated by the land owner / developer through a professional contractual relationship. The only interaction the architect has had with traders has been through formal planning objections. It’s not surprising that this is strategy is shared between the two projects as it is one of the very few legal means residents have to speak in the planning system.

Again, like Our Yard, Latin Elephant have had to plug in the gap between the local community needs and wishes and the developer ambitions through the following strategies:

1) Mapped the traders that were on site and their eventual relocation

2) Mapped the stakeholders especially land owners that are part of the development

3) Organised workshops for traders to go through planning documentation so they can organise objections

4) Lobbied pressure on local councillors through protest and social media campaigns

5) Being actively present in the community on a regular basis so they can listen to their needs and build relationships of trust.

I feel like both projects highlight key limitations in current architect role in large scale developments and it has been interesting to contrast this with Edit collective projects we explored this week, whose practice I feel is much more aligned with Latin Elephant and Our Yard. For example Honey, I’m Home ongoing research project use comedy / mixed media / design to agitate ‘accepted’ spatial practices and question why and who benefits and is disadvantaged by these practices – in a similar way to how both grassroot initiatives questioned careless demolition instigated by developers. Also, for all three groups there is a clear focus on the collaborative process instead of the final product, for example the – How we live now? Barbican exhibition – displayed emails, working construction details and engagement tools – instead of just the final building design.

Key lines of inquiry I will be taking away from this week:

1) The current focus is to document what exists ‘physically’ on a site in planning documentation for example access to site or legal land issues. This means that the social networks and economic dependencies of traders in Elephant and castle and the community needs in Brent Cross were just completely missed, and the architects/ urban designers were not obligated to consider them in the design process.

2)The current business structure of most architectural practices as private for-profit companies, means it is difficult for them to sustain their business while work with grass-root groups with limited financial resources (Studio Polpo provides an alternative to this – discussed in this post)

3) A key element of both Latin Elephant and Our Yard strategies is ongoing presence on site, continuously checking in with local people and developing collaborative networks. How can an architect play a role in this if they are contractually obligated to the single most powerful stakeholder – the developer?

0 notes

Text

Chronicled reflections - Elephant and Castle walkabout

By Santiago

It's a nice breezeless Wednesday morning in Elephant and Castle. As some of the local traders are still recovering from the consequences of the massive explosion this week, I meet Maha and Agnes outside the train station. We get a coffee from Esmeralda's, a lovely Colombian woman who has been running this small caf under un arch for the past decade or so. We walk along Elephant Road and turn on New Kent Road, and as we get to the traffic light we meet Rowan. All four of us cross the road towards the historic Elephant and Castle pub, and as we turn we observe a massive hoarding covering what was until recent months the home of Latin Americans and other migrant communities in the UK, the beloved E&C Shopping Centre.

We stand outside Nando's restaurant reflecting on the history of this building, built in 1965, and the consequences of the displacement for many communities that have made of London a new home.

But I can't help keep thinking the pavement we are standing on, the route and turn we took on New Kent Road, the coffee we got in Elephant Road and of course the site we are now observing... None of these places are public-owned. Effectively, we have been walking around the area for the past half hour or so but have not stand on public land for a second.

This is a sad reality here in South London, as well in many other areas in London. Land has become a commodity, each square meter mostly sold to oversees developers whose sole interest is to maximise their profits.

But if for a second you look beyond these tall towers and luxury apartments in the area, there are many communities that once inhabited this place and created a multi-ethnic hub in the heart of London, contributed hugely to the economy of the city and offered invaluable social and cultural value to a once very deprived area of UK's capital.

How did they appropriated these places? Can they overcome the threat of gentrification? Can they continue to perceive Elephant as their home in the UK?

With these questions in mind, we continue our walkabout towards Castle Square, a temporary retail market where some of the long-standing small independent traders relocated once the Shopping Centre closed its doors for the last time 24th September 2020.

This site was gained during the planning process by campaigners and local groups as a result of tough negotiations with developers Delancey and local authority Southwark Council. To be able to relocate some 20 or so traders (out of over 80), the Council had to sell this square to private developers based oversees.

As we wander around, Maha makes a remark on the wooden structure of the market -which could be any market in any city, really...- and wonder if the aesthetics has an impact on how certain communities appropriate space.

"Inside the shipping centre was much better, we used to have many customers, now I've lost 95% of my regulars. People don't know where are here...," local trader Abdul Reza, owner of Magic Carpets sin 2002, tells Rowan, Agnes and Maha.

Upstairs on the upper floor, Kevin joins Reza to say that his mobile repair shop was very successful until closure of the Centre. In the case of Kevin, the impact has more layers as his son and daughter would come back from school every day and run around the Centre until he and his wife Andrea, who owned the beauty salon next to Kevin's, would close and go back home as a family. Andrea is now on a much smaller unit on a different wing of Castle Square, and their kids still run around the square and the adjacent Elephant Park - but as both sites are owned by private developers, their future is uncertain as they can only rely on financial decisions taken in fancy offices somewhere in a glassed building on the River Thames. Or based at an offshore tax heaven in the Caribbean.

We then cross the road and immerse into the micro-world of the 'Elephant Arches', where around 80 or so Latin American-run businesses make the so-called Latin Quarter of London, an area that was a ‘no-go zone’ in the 80s and 90s and were displaced Colombians, Ecuadorians and Peruvians appropriated a quite central pocket of London making it a landmark for many Spanish-speaking and other migrant communities in London.

As we get a taste of Latin America with a Colombian coffee and guava pastry from 'Distriandina', once a restaurant and night club, now turned into a mini-market due to the pandemic, I once again reflect on how much longer we will be able to enjoy these treats since Colombian owner César and his family will eventually have to empty the arch to make room for Delancey's vision of a Town Centre, not owning the arches themselves but having to acquire it from... another oversees company named The Arch Company, who recently purchased all UK's railway arches from Network Rail, a public sector company.

It hasn’t always been like this. Behind us stood the Heygate Estate, one of the biggest public owned housing complex in the country. When it was demolished to make room to luxury flats in 2014, small traders lost most of their regular customers. And after the Shopping Centre closure, another fraction of their regulars was sadly gone too.

And yet, despite facing challenge after challenge, migrant communities have managed to outlive the several attempts of displacement. It’s almost as if it were in their skin -a very thick skin-, having been displaced from their home countries, starting a new life in an unknown country, setting up a business, having to close to start all over again.

How do you do it?, I ask Ana Castro, another long-standing trader who relocated from the Shopping Centre to Castle Square.

‘We are migrants. We are used to surviving, fighting for everything. So if we find a small piece of land, even a corner, we will make something out of it,’ she says as she pinches herself in the arm. ‘Thick skin,’ she laughs.

0 notes

Text

The Brief

“Making cities’ will be perceived from an inside perspective and upon the alliances between urban planning, architecture, art, social movements and bottom-up initiatives and their aim of designing (social) public infrastructures and their perception of architecture as an instrument for progressive social change. We will engage with topics such as: the context of migration, ethics, subversion and dissent, power and space, care, social impact of the built environment, urban practice.”

During this week we have visited and been introduced to urban practice projects of different scales and complexities to help us reflect on the theme of Making cities through our individual research questions.

The following projects have been featured on the Tumblr page :

Stadtwerk Mrzn https://www.s27.de/portfolio/stadtwerk-mrzn/

Haus Der Statistik https://hausderstatistik.org/

Urban Praxis http://development.urbanepraxis.berlin/about/?lang=en

Elephant and Castle Redevelopment https://latinelephant.org/map/#

Cricklewood/Brent Cross Redevelopment https://transformingbx.co.uk/

Clitterhouse Farm Project https://www.clitterhouse.com/

Deep-Level Shelter at Clapham South

https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/hidden-london/clapham-south

Black Cultural Archives https://blackculturalarchives.org/

How We Live Now? Barbican Exhibition https://www.editcollective.uk/how-we-live-now

Honey I’m Home https://www.editcollective.uk/honey-im-home?lang=en

Now You Know https://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/sound-advice-now-you-know

Learning from London’s Lack of Lockdown Loos - https://www.editcollective.uk/post/manage-your-blog-from-your-live-site?lang=en

0 notes

Photo

It was so incredibly interesting to see the incredible efforts of #latinelephant to work with the traders of the elephant and castle market to negotiate fair relocation deals with council and developers. What really struck out for me is how the social fabric of the old market was never considered important to analyse by the developers and the design team. One of the ramifications of this is traders who are long term neighbours and whose businesses benefited from each other have been separated across the different sites - impact social and economic networks and relationships.

#designinginclusion #makingofthecity #collaborativedesign #regenerationofmigrantspaces

0 notes

Photo

Interesting quote from the book Migrants & city making, which I feel relates to alot of the discussions we have been having this week

Migrants & City-Making. Dispossession, Displacement & Urban Regeneration. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Available at: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/25763/1004325.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

0 notes

Photo

An interesting point of discussion during our clitterhouse farm tour is the role of the architects throughout the years. Paulette talked about long-term relationship they have developed with two student architects who have spend many hours on site and embedded in the community - and have run a series of art workshops through the years. They are now a key player in the future vision of the site and it reminded me of this article which takes about the business model of Studio Polpo.

‘’In practice previously, Parsons and Cerulli spotted a gap that many community organisations struggle with – accessing advice and expertise at those early stages before feasibility studies or any sign of funding. So another of their aims as a social enterprise is to support third sector organisations and help them develop strategically. Through a formal asset lock, they committed to spending profit or surplus in that sector – they use it for funding early stage feasibility work. Occasionally this work has generated payment, as organisations take on the ‘receipt’ for the work to the funding bid. But more excitingly it has meant Polpo establishing working relationships with interesting organisations that over time have enriched both.’‘

https://www.ribaj.com/intelligence/studio-polpo-profile-community-service-sheffield

#communityengagement #designinginclusion #makingofthecity #roleofthearchitect #businessstructures #socialenterprises

0 notes

Photo

Another site visit today was clitterhouse farm in North-West London. We were taken on a tour of the site by social enterprise #OurYard co-founder Paulette, who explained the long history of this site and how a community group came together to save it from demolition. The building is in the midst of the brent cross regeneration scheme and is currently planned to be replaced by a depot - #OurYard have been working for 7 years to convince the council and the developer to work in partnership to regenerate this site in a way that addresses community needs, while simultaneously provide a physical space for any individual in the community to try out ideas such as festivals, theatre groups, art workshops through negotiating with current leaseholders and creating a strong network within the community and wider london.

A key tactic they have in negotiations with the council and developers is a feasibility study which is a result of a long and extensive consultation with the local community.

#designinginclusion #northwestlondon #makingofthecity #collaborativedesign #developmentpartnerships #communityspace #socialresilience

0 notes

Photo

Such an inspiring exhibition @barbicancentre produced by #editcollective featuring so many woman-led feminist practics with a focus on Matrix - Spatial agency describe as ‘co-operative with a non-hierarchical management structure and collaborative working. Their work explored issues surrounding women and the built environment, but also the relationship of women to the architectural profession and to the procurement of architecture’

We learnt so much and now more fustratted than ever that such practices are not a central part of architecture education

#designinginclusion #themakingofthecity #participatorydesign #feministarchitecture

0 notes

Text

www.latinelephant.org/map

This interactive map will hopefully complement our walk this morning by showing all the small businesses there were inside the shopping centre and how there were discrepancies with Southwark Council and Delancey as to how many there were, and how many available units for relocation were offered

0 notes

Text

A good example of a mixed uses Arch on Elephant Road, Elephant and Castle.

One arch, 12 small businesses. Despite being inside the red line of the development, these local traders are still trading but will eventually have to leave as developers Delancey have included them in their plans.

Inside, Nancy's restaurant serves a succulent lunch to dozens per day for just £8. The importance of affordable meals and products in the area is key to the local population.

0 notes

Text

Rowan, Agnes and Maha speaking to Abdul Reza, owner of Magic Carpets. Reza has been trading in Elephant and Castle since 2002.

Says: "Inside the shipping centre was much better, we used to have many customers, now I've lost 95% of my regulars. People don't know where are here..."

Reza has been relocated to Castle Square, one of the three main relocation sites after closure of the Centre in September 2020.

0 notes

Text

This is one of the about 80-90 Latin American run businesses in Elephant and Castle. A Colombian family business that has been in Elephant Road (next to the train station exit) for over a decade and has been affected by the explosion on Monday.

In terms of the so called regeneration, the 'red line' of the development forced them to close their back garden with big refrigerators and toilets. Not a displaced business but an affected one for sure

0 notes

Text

Diversity of inclusion and inclusion of diversity

0 notes