Robin / R.J. BSc(hons) Zoologist who just loves talking about little guys!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

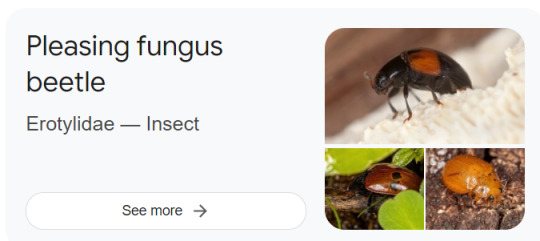

The shape of a fish's caudal tail can tell you a lot about how fast the fish moves! A rounded tail is the slowest and a lunate tail is the fastest! The lunate tail has the most optimal ratio of high thrust and low draw, making it the fastest.

Ichthyology Notes 2/?

#today is apparently fish day for this blog#I ADORE comparative anatomy like this. It's the main line of study I want to specialise in#teleosts#icthyology#fish

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

Parrotfish are a group that I recently learnt about for my degree, and I can't believe I hadn't heard of them before!

Parrotfish come in all shapes, sizes and colours and can be found within tropical waters, most prominently in the Indo-Pacific. Their favourite places to live are coral reefs, rocky coastlines and seagrass forests.

Quoy's parrotfish (Scarus quoyi) - François Libert

Why do I like them so much? Well, they take part in a key role within ecosystems, called bioerosion.

Have you ever been to a white, sandy beach before? That is the work of parrotfish! They are predominantly herbivores, scraping algae off of rocks and coral, with some also being able to slice through tough macroalgae (seaweeds). My personal favourites are the corallivores - parrotfish that exclusively feed on coral.

Because of their sophisticated diets, parrotfish have evolved very fancy dentition, where their teeth have rearranged over time to become beak-like (hence their name!) along with evolving strong jaw muscles and a mill-like structure (called a pharyngeal mill), which helps them grind up their food.

Tricolour parrotfish (Scarus tricolor) - François Libert

Since they scrape along coral and other rocky substances all day, they tend to ingest a lot of minerals, including calcium, which is eventually excreted. Long story short, those white sandy beaches are actually the hard work of bioerosion carried out by hundreds of thousands of parrotfish over millions of years.

Just one humphead parrotfish can produce 90kg of sand per day!

School of blue parrotfish (Scarus coeruleus) - Gérard Cachon

Without parrotfish, we wouldn't have those beautiful beaches. But more importantly, they are absoloutely key to the health and structure of tropical reefs.

Tricolour parrotfish (Scarus tricolor) - François Libert

Image credits:

François Libert - Flickr

Gérard Cachon - Flickr

Thank you to the photographers for providing such stunning images under creative commons licenses so I can write about my favourite species with beautiful pictures to accompany my work.

I thought I would branch out from only writing about invertebrates so far to talk a bit about some vertebrates for once. I had some lectures on marine ecology and I was enamoured with this group of fish, I just had to write about them. They're just so beautiful!

I may talk about their sequential hermaphroditism in a future post, since that's a whole other can of worms that I would love to write about. Maybe a pride month special?

#biology#zoology#marine biology#scaridae#parrotfish#fish#teleosts#mantismage#ecology#marine life#environmental science

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honeypot ants are fascinating, but feel like something that in concept, is terrifying. And would definitely be a plotline in a Mad Max movie.

These are specalised worker ants that deliberately consume huge amounts of food, to the point where their abdomens will swell to ridiculous sizes. The sclerites (the thickened keratin armour) on their abdomens will separate, revealing the honey inside of their abdominal membrane.

These ants will collect and store liquid which other ants in the colony will then consume, basically functioning as living larders. When they become big enough, they'll hang from the ceiling and can reach the size of a blueberry or a small grape:

They're mostly found in more arid areas of the world; in hot deserts, dry woodlands and other similar habitats (Australia, North Africa, some areas in the Americas etc.). Their existence is likely to allow for colonies to store food during extreme dry seasons, or during periods where food is scarce.

There's been some research indicating that honeypot ants contain unique antimicrobial properties within their honey, which has been used by indigenous people in Australia for centuries!

(Extra note: They also go by repletes or rotunds?? I love scientists.)

Resources and extra reading:

Conway, J. R. (1991). The biology and aboriginal use of the honeypot ant, “Camponotus inflatus” Lubbock, in Northern Territory, Australia. Australian Entomologist, 18(2), 49–56. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.108392124224680

Dong AZ, Cokcetin N, Carter DA, Fernandes KE. (2023). Unique antimicrobial activity in honey from the Australian honeypot ant (Camponotus inflatus) PeerJ, 11:e15645 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15645

National Geographic (2016). Honey Ant Adaptations. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20210120124043/https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/honey-ant-adaptations-wbt/

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellowjacket-Mimicking Moth: this is just a harmless moth that mimics the appearance and behavior of a yellowjacket/wasp; its disguise is so convincing that it can even fool actual wasps

This species (Myrmecopsis polistes) may be one of the most impressive wasp-mimics in the world. The moth's narrow waist, teardrop-shaped abdomen, black-and-yellow patterning, transparent wings, smooth appearance, and folded wing position all mimic the features of a wasp. Unlike an actual wasp, however, it does not have any mandibles or biting/chewing mouthparts, because it's equipped with a proboscis instead, and it has noticeably "feathery" antennae.

There are many moths that use hymenopteran mimicry (the mimicry of bees, wasps, yellowjackets, hornets, and/or bumblebees, in particular) as a way to deter predators, and those mimics are often incredibly convincing. Myrmecopsis polistes is one of the best examples, but there are several other moths that have also mastered this form of mimicry.

Above: Pseudosphex laticincta, another moth species that mimics a yellowjacket

These disguises often involve more than just a physical resemblance; in many cases, the moths also engage in behavioral and/or acoustic mimicry, meaning that they can mimic the sounds and behaviors of their hymenopteran models. In some cases, the resemblance is so convincing that it even fools actual wasps/yellowjackets.

Above: Pseudosphex laticincta

Such a detailed and intricate disguise is unusual even among mimics. Researchers believe that it developed partly as a way for the moth to trick actual wasps into treating it like one of their own. Wasps frequently prey upon moths, but they are innately non-aggressive toward their own fellow nest-mates, which are identified by sight -- so if the moth can convincingly impersonate one of those nest-mates, then it can avoid being eaten by wasps.

Above: Pseudosphex laticincta

I gave an overview of the moths that mimic bees, wasps, yellowjackets, hornets, and bumblebees in one of my previous posts, but I felt that these two species (Myrmecopsis polistes and Pseudosphex laticincta) deserved to have their own dedicated post, because these are two of the most convincing mimics I have ever seen.

Above: Pseudosphex sp.

I think that moths in general are probably the most talented mimics in the natural world. They have so many intricate, unique disguises, and they often combine visual, behavioral, and acoustic forms of mimicry in order to produce an uncanny resemblance.

Several of these incredible mimics have already been featured on my blog: moths that mimic jumping spiders, a moth that mimics a broken birch twig, a moth caterpillar that can mimic a snake, a moth that disguises itself as two flies feeding on a pile of bird droppings, a moth that mimics a dried-up leaf, a moth that can mimic a cuckoo bee, and a moth that mimics the leaves of a poplar tree.

Moths are just so much more interesting than people generally realize.

Sources & More Info:

Journal of Ecology and Evolution: A Hypothesis to Explain Accuracy of Wasp Resemblances

Entomology Today: In Enemy Garb: A New Explanation for Wasp Mimicry

iNaturalist: Myrmecopsis polistes and Pseudosphex laticincta

Transactions of the Entomological Society of London: A Few Observations on Mimicry

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

People who like mantises but aren't that into entomology are always "orchid mantises" this and "orchid mantises" that. Overrated. Can we talk about Toxodera integrifolia for a minute:

(Image links because as much as it pains me I've never seen one of these beauties irl: 1 2 3)

Like how are these things real. Girl what is that thorax shape. Why are you wearing eyeliner. And the colors? Absolutely fire. This is a 10/10 insect if you ask me.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact: there’s a virus that makes bugs iridescent

disease that makes you beautiful then kills you

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

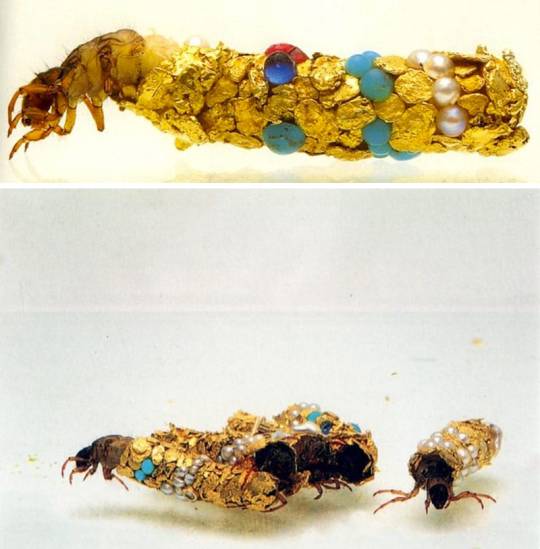

After years of observing these caddisfly larvae, French naturalist and artist, Hubert Duprat, wondered if the caddis flies would use any materials to build their cocoon. He introduced flakes of gold, pearls and opals to the caddis flies and they did in fact use them for their cocoons. They use their own silk as the glue to hold their pupal constructions together.

49K notes

·

View notes

Photo

GIRL POWER A female Lynx Spider (Hamadruas sp., Oxyopidae) exerts her dominance over a male of the same genus (but maybe not the same species). Although the females of some spiders devour the males as a courtship ritual, I am unaware that this is standard for the lynxes, so this may simply be a predator/prey situation. by Sinobug (itchydogimages) on Flickr. Pu'er, Yunnan, China See more Chinese spiders and arachnids on my Flickr site HERE…..

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invert fact #3: Leeches

Did you know that most annelids (marine worms, earthworms and leeches) are hermaphrodites; having both "male" and "female" reproductive organs? Terrestrial and marine worms can reproduce both asexually and sexually, but leeches can only reproduce sexually. And guess what? They have penises. Well, some of them.

For example, the family Gnathobdellae transfer sperm this way. They reproduce by having two individuals basically rub up against eachother, with their heads facing in opposite directions; this allows contact between one Leech's "male" gonopore (a genital pore in the side of the body), and the other Leech's "female" gonopore. This allows a leech to transfer a spermatophore, which is basically a little packet of sperm cells, to the other leech. The miracle of life, everyone.

Bonus fact: Earthworms have prostate glands. I'll leave you to think about that one in your spare time, though.

Sorry it's been a while since a new post! I have been very busy with Uni work, but I'm hoping on bringing this back to a weekly thing.

References:

Study.com. (2019). Annelid Reproduction: Facts & Example

Foundation, C.-1. (n.d.). Annelid Reproduction.

Image credits go to Niel Phillips

#annelid#leech#Hirudinea#entomology#invertebrates#MantisMage's Invert Facts#zoology#biology#mantismage

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invert fact #2: Giant Dead Leaf Mantis

Also known as Deroplatys desiccata, A species native to Southeast Asia...

These mantises get their namesake from their highly adapted camouflage, making them look similar to a dead leaf. They use this camouflage to ambush prey, and hide from predators in the tropical forests and shrublands of Southeastern Asia.

Their thorax is commonly seen flattened, copying the look of many leaves. Their bodies are brown in colour, with speckling and vein-like protrusions which also contribute to the fascinating camouflage they have evolved.

Their wings also have 'eyespots', which they display when they feel under threat. They also commonly 'sway' when threatened to replicate the movement of a leaf in the wind.

#Deroplatys desiccata#Deroplatys#Mantodea#Mantis#Praying mantis#Zoology#Biology#MantisMage's Invert Facts#Invertebrates#Bugblr#mantismage

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invert fact #1: Fairy Flies!

Fairy Flies may be named flies, but are actually a genus of parasitoid wasps, known for encompassing both the smallest insect and smallest flying insect in the world.

The smallest flying insects, being from a genus named Kikiki, contains one single species; Kikiki huna. Some K. huna individuals have been recorded being only 150 μm! (0.15 mm). They are the smallest flying insects known (as of 2019).

Well, how about the smallest non-flying insects? Specifically, males in the genus D. echmepterygis. These boys only average 186 μm (0.186 mm), shorter than some amoebas and bacteria! They are also blind, lack wings and are tiny in comparison to females of the same species, which range closer to 550 μm (0.55 mm)

Citings for nerds (including image citations) and extra notes:

Huber J, Noyes J (2013) A new genus and species of fairyfly, Tinkerbella nana (Hymenoptera, Mymaridae), with comments on its sister genus Kikiki, and discussion on small size limits in arthropods. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 32: 17-44. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.32.4663.

Welcome to Invert facts! I am unsure how frequently I will post to this blog, but I do hope you enjoy its content. I may expand things in the future if the blog gets enough attention, but we will see how stuff goes!

#MantisMage's Invert facts#Entomology#insects#wasps#fairy flies#Invert facts#invertebrates#bugblr#biology#zoology#mantismage

49 notes

·

View notes