Desconstrucion and analysis of artwork and photos, book covers, film posters, magazine illustrations, adverts, etc., created for a persuasive purpose. My name is Dave Wilt and my mission is to inform and entertain.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

Hi. Have you ever seen this poster or film? “Chivato, the Bearded Betrayer.” I’ve had the poster since the 70s and I’m curious. Thanks I can’t figure out how to attach a photo of the poster

This was completely new to me! I'm building up a file of pop culture references to Castro and this fits right in. Will have to do some research on the origins of this film.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A Hair-Raising Tale (Hair-Growing Beatles, 1965)

Were the Beatles the first “hair band?” Not like Poison, RATT or Twisted Sister, of course, but the Beatles’ hairstyles were an integral part of their public image. They weren’t called the “mop tops” for nothing, and while their hair (and outfits) seem positively conservative today (at least until the latter part of the Sixties when they turned into a bunch of hippies--get off my lawn!), there were many jokes about their “long hair.”

[“One day a boy with exceedingly long but untrained hair walked into a barbershop, sat down in the chair and demanded, "Make me look like Ringo Starr." The barber studied the tonsorial problem for a moment, carefully picked up his hairbrush, took aim and broke the boy's nose.” ‘Think and Grin’ in Boys Life magazine, October 1965]

The Beatles were frequently referred to as “long-haired” and even “shaggy,” adjectives which in the 1960s weren’t necessarily positive. The conventional style for men in this era was short hair, clean shaven. “Beatniks” were disparaged as hairy, unkempt, unclean (and later in the decade “hippies” were tarred with the same brush, even moreso). The Beatles weren’t beatniks by any stretch of the imagination, and were consistently better-dressed than their short-haired rivals like the Beach Boys. Still, that hair!

In the “Los Angeles Times” (11 February 1964), a critic wrote: “With their bizarre shrubbery, the Beatles are obviously a press agent's dream combo…the hirsute thickets they affect make them rememberable…” Newsweek (Feb. 24, 1964) referred to the Beatles’ “great pudding bowls of hair.” Many of these early critics (presumably middle-aged men) also disparaged the Beatles’ musical ability and found the intensity of Beatles’ fandom puzzling and upsetting.

Merchandisers got into the long-hair act as well, selling Beatles wigs, board games (“The Beatles Flip Your Wig” game, 1964), Beatles combs and brushes, Beatles shampoo, Beatles hair spray, and so on. There was even a Beatles’ alarm clock featuring artwork of the Fab Four adorned with actual hair.

A number of these items would probably have been sold regardless of the notoriety of the Beatles’ hairstyles (since there were countless other Beatles-labeled items which had no specific connection to their life, such as nylon stockings!), but it’s undeniable that their hair was part of their brand, for good or ill.

The particular advertisement analysed here (from the comic book Teen-Age Love 43, 1965) is an item which doesn’t appear to have an actual name--or at least not one that’s discernable from the advertisements. The ad header just says THE BEATLES, and the text never settles on a specific product name, referring to the “fabulous BEATLES,” “your Beatles,” “miniature BEATLES,” and “LIVING BEATLES.” No image of the product is shown, and the description of what a buyer gets for her/his $1.00 and what happens thereafter is quite vague. Intensive research (alright, I spent some time searching the web) provides no concrete information about the product.

It’s not a “game” or “toy” or even a personal product. The ad says “you can even give them haircuts!” but most of the time the buyer is expected to sit around and watch “RINGO, GEORGE, PAUL AND JOHN grow their famous hairdoes right before your very eyes.” Yep, next to watching paint dry, watching hair grow is about the most exciting thing I can imagine. But your impressionable friends will “gasp with awe and delight.” Come visit next week and I’ll let you watch the mildew spread in my shower.

It’s “a scientific wonder” and a “fantastic scientific method” will allow the BEATLES to GROW BIGGER AND BIGGER, FASTER AND FASTER EACH AND EVERY DAY. Soon they’ll take over your room, your house, your town, the world!! Mwa ha ha!!

Could this have been a precursor to the “Chia Pet,” first created in 1977? There actually was a “Chia Beatles” set available in the 2000s, but this 1964 product certainly doesn’t refer to that. Although the ad clearly states “grow their own hair,” one assumes this is marketing hyperbole, and actual human hair didn’t grow on these…whatever they were. The text provides a slight hint by stating “All you have to do is lead them to a cup or glass of water and give them a drink,” from which we can infer that the “hair” is some sort of renewable plant. Are these just weeds that are named RINGO, GEORGE, PAUL AND JOHN (I bet Ringo was happy to get top-billing at last)? Or are there 4 little clay pots with images of the Beatles on them?

It seems significant that the ad not only doesn’t go into detail about the nameless product, the product isn’t pictured. This wasn’t entirely unknown, and even ads which do include artwork of items for sale must be taken with a grain of salt. But given the extreme mystery surrounding this item, suspicion is aroused.

But did Beatles’ fans in 1964 care what they were getting when they sent their $1 (plus $.25 for postage and handling) off to Novel Products Corp.? (Another ad for the same product lists A&B Industries as the seller, at a different New York address) Probably not. Fans will buy anything.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bowling for Dictators

Deconstructing propaganda is an interesting exercise. Like advertising (in fact, the word “propaganda” is used almost interchangeably with “advertising” in some countries), propaganda is intended to motivate the recipient towards a particular action or to reinforce and/or instill a specific mindset (as opposed to simply educating or entertaining the consumer of such material).

Wartime propaganda tends to be ubiquitous, obvious and strident. During the First World War, propaganda appeared in print media (newspapers, magazines, books), visual media (posters), audio recordings, and motion pictures (commercial radio was not yet in place and television and the Internet hadn’t been invented). The Second World War added radio to the media mix, and some might argue that this was when propaganda reached its peak, since no subsequent wars have been as widespread (and thus had so many different countries producing propaganda).

Even 70+ years later, WWII propaganda still resonates. “Keep Calm and Carry On,” “Rosie the Riveter,” “Loose Lips Sink Ships,” and other phrases and images are re-purposed as memes, advertisements, etc. In some cases, people doing this “ironically” may not be especially aware of the significance of the original, seeing it as just something old and amusing.

There were certain repeated themes and motifs in WWII propaganda (some of them are common to all propaganda). In Allied media, Hitler is crazy & demonic but also a vain buffoon. Mussolini is also a buffoon, and Hitler’s toady. The Japanese are “treacherous,” and “stabbed us in the back” at Pearl Harbor. They’re also more likely to be depicted as animals, insects, or monsters. The Nazis and the Japanese are prone to committing atrocities, such as murdering women and children. All of these themes and many more can be seen in different forms of propaganda, from comic books to posters to motion pictures.

Occasionally the motifs are so specific that one can’t imagine they would have been widespread, but one learns that sometimes one can be wrong (one need not be embarrassed about it). Today’s deconstruction subject is the “Axis as bowling pin” metaphor--aka “Bowling for Dictators”--which exists as a War Production Board propaganda poster (probably the earliest example, dated 1942--there are both colour and sepia-tone versions of the poster online), actual bowling pins (possibly just novelties and not really used in a bowling alley), a home bowling game (“Bo-Lem-Ova”--see above), at least one other piece of merchandise (an illustrated envelope or postcard) and two comic book covers. It’s possible, even likely, that “Hitler, Mussolini and Tojo/Hirohito/generic Japanese officer as bowling pins” also appeared in other formats.

The comic book covers and the bowling game will be the primary focus of this essay, although first, a few words about the overall meaning of this motif. Two basic statements are being made. First, “we will punish the Axis leaders (and by extension, their soldiers).” Bowling is one way to symbolise this punishment; other propaganda motifs with the same idea utilise a boxing metaphor or simple and direct depictions of Hitler, Mussolini, and a militant Japanese figure--either the actual characters or some stand-in such as a photo or poster--being punched, kicked, slapped, and so forth. Hitler dartboards and Hitler pincushions also existed. It’s not enough to defeat the enemy on the battlefield, their leaders or surrogates must suffer personally and physically.

The second idea conveyed by the Axis bowling pin motif is that the dictators are unsteady and can be “toppled” if the proper pressure is brought to bear on them. This is fairly specific to the bowling metaphor, although similar precarious situations could be imagined (a dictator on a high-wire, a dictator out on the limb of a tree, and so forth).

The “Bo-Lem-Ova” game was issued in 1943 by Kindred MacLean & Co., a “window display” company based in Long Island City, NY. They also produced at least one other game in this era, “Luk-E-Star” (somebody at Kindred MacLean liked hyphens and phonetic spelling). The bowling “pins” are printed on cardboard, and were assembled with stand-up bases. The bowling “balls” are marbles, which are rolled down the cardboard “alley” (which looks pretty nice--an assembled version can be seen on page 34 of this 1943 toy catalog). As the box notes, this is “2 Big Games in 1,” since there are two sets of pins: one featuring Hitler, Mussolini, Generic Japanese Militarist Man, and 7 Nazi soldiers, and the other with 10 cardboard fascimiles of regular bowling pins. I suppose Kindred MacLean was hedging their bets, either trying to make the game acceptably non-partisan in case it was sold in a neutral country, or hoping to extend its shelf-life past the war’s end, when “K-O the Axis” was no longer relevant.

If you look closely at the box, you’ll see the figure of Mussolini has printing on its chest: “One Down July 25, 1943 Two to Go,” an allusion to the date when Mussolini fell from power in Italy. It’d be interesting to know if this figure was originally conceived with this printing, or if it was hastily added at the last minute. “Bo-Lem-Ova” newspaper ads exist from as early as November 1943 (and began appearing again in the run up to Christmas 1944), so--given the lead time required to design and manufacture the set--it may have been a close-run thing. Many (but not all) pop culture depictions of the Axis largely ignored Mussolini after his downfall, so it is possible Kindred MacLean wanted to include him even though he had been deposed just before the game was created, to highlight the fact that there were still “two to go” to defeat the Axis powers.

The Nazi soldier figures are individualised, a nice touch: some look mean, some are deadpan, and a few appear fearful. The Japanese character grimaces fiercely, and Hitler is giving his signature “Heil!” salute. Out of all the “bowling pin” material bearing the Axis images, only the novelty envelope (or is it a postcard?) has Hitler, Mussolini and their Japanese partner reacting as if in pain to the impact of the bowling ball, for what it’s worth.

The two comic book covers utilising this motif were dated January 1943 (Sensation Comics 13)--on sale in November 1942--and “Winter” 1944-45 (Bomber Comics 4). Sensation Comics was published by All-American Publications, which later merged into what is now known as DC Comics (although the cover of Sensation 13 features the “DC” logo, the two companies were separate-but-related at the time). All-American superheroes included Green Lantern, the Flash, and the cover star on every issue of Sensation from numbers 1-106, Wonder Woman.

The cover was drawn by H.G. Peter, the original and primary Wonder Woman artist from 1941 until 1957. Peter had a distinctive style, neither rigidly realistic nor overtly cartoony. Wonder Woman was generally drawn “straight,” as she is on this cover, while her sidekick Etta Candy (the pudgy redhead at right) was more of a caricature. [This was not unique in the Golden Age: the mostly-realistic “Blackhawk” strips included the grossly exaggerated Asian caricature Chop Chop, for instance.] Etta and the other young women in the upper right-hand corner of this cover are wearing what one assumes are athletic outfits for Holliday College, hence the “H.” Either the bowling lane is very short, and the bowling ball and pins are huge, or Peter was forced to cheat on the perspective so as to make Wonder Woman sufficiently large and prominent and still squeeze in the large Hitler, Mussolini, Japanese militarist figures in the foreground.

The cover of Sensation Comics 13 is neither allegorical nor realistic, falling somewhere in between. An “allegorical” cover might, for instance, show Wonder Woman waving the American flag, while “realistic” covers depict Wonder Woman in some sort of action situation (fighting criminals and so forth). This cover has the main character participating in a realistic activity (bowling) but the Axis-themed bowling pins are symbolic of anti-fascism.

Both the cover of Sensation 13 and Bomber 4 are drawn so that the reader is seemingly situated behind the bowling pins, rather than putting the pins at the rear of the page and placing the reader behind the bowler. The cover of World’s Finest 9 (Spring 1943) features an example of the reverse perspective: Batman, Superman and Robin are in the left foreground, throwing baseballs at Hitler, Mussolini, and a Japanese caricature in the right background, which seems a more logical layout.

The cover of Bomber Comics 4 is very similar to Sensation Comics 13, and could very well have been “inspired” by the earlier issue. The design is practically the same: the hero is in the left background, bowling towards the pins in the right foreground. The bowler is superhero Wonder Boy, while the spectators are Kismet “Man of Fate,” a Muslim superhero, and a young woman (who may be Sally Benson, a character from the Wonder Boy strip). Such multi-hero covers were fairly common in the Golden Age, even if cross-overs in comic stories were not (in fact the cover of Bomber Comics 3 depicted Kismet, Wonder Boy, and numerous other characters from interior stories in a single scene).

While the bowling pins on Peter’s Sensation cover looked more like chess pieces, with large carved heads on top of each pin (making them rather top-heavy, one would imagine), the unknown artist on Bomber Comics goes with standard pins bearing the painted likenesses of the Axis leaders, a more practical design. Oddly enough, Hitler appears to be wearing a German Navy cap, and Generic Japanese Militarist is also dressed in an atypical blue (naval?) uniform. The inclusion of Mussolini on this cover is less logical than it was on Sensation, which was published while he was still in power; Bomber Comics 4 was released no earlier than late 1944 (possibly even early 1945), a year and a half after Mussolini had been deposed (although he was later the titular head of a Nazi puppet government). It’s highly unlikely this cover was drawn in 1943, so Mussolini’s appearance on Bomber Comics 4 makes little sense: in late 1944, the “Axis” in the public mind was Hitler and the Japanese, period.

Bomber Comics was one of only 2 titles issued by Elliott Publishing in the 1944-45 period (the other was Spitfire Comics). Oddly enough, Bomber features characters formerly published by Quality, including “Wonder Boy”--these don’t seem to be reprints, but may represent unused Quality inventory. This doesn’t explain the covers, however, since Kismet was not an existing superhero, appearing only in the four issues of Bomber.

How did the “Bowling for Dictators” motif develop and why was it used multiple times? We may never know. The permutations of propaganda are varied, but not unlimited, so a good metaphor is often recycled.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Fish With Human Hands Attacked Me! (True Weird magazine)

As cartoon Leonard Nimoy said in an episode of The Simpsons: “The following tale of alien encounters is true. And by true, I mean false. It's all lies. But they're entertaining lies. And in the end, isn't that the real truth?” The word “true” is frequently used in marketing to literally add a veneer of verisimilitude to whatever is being sold. Magazine titles with “true” in the title include the long-running True, True Action, True Confessions, True Crime, True Detective, True Experience, True Love Stories, True Romances, True War, and True West, to name a few. Also, True Weird and True Strange, the subjects of today’s desconstructive criticism.

Setting aside the odd-sounding titles, which consist of two adjectives but no subject (the titles aren’t True Weird Stories or True Strange Tales, for instance), these two relatively short-lived magazines are notable chiefly for their provenance (published by a body-builder), their prescience (foreshadowing future publications dealing with “weird but true” events), and their interesting covers (of primary interest to us).

True Weird and True Strange were published by Joe Weider, a body-builder and fitness guru born in Canada in 1919. In the 1930s he started selling nutritional supplements and in 1940 began his magazine career with Your Physique. As time went on, he sold body-building books and courses, and expanded his publishing empire with physical culture magazines like Mr. America, All American Athlete, Muscle Builder, American Manhood, and Junior Mr. America. Weider branched out into other genres as well, issuing Animal Life, Fury, Outdoor Adventures, Jem, and Monsieur (the latter two were Playboy-esque girlie magazines), and historical magazines such as Armchair General and Civil War Times in the 1980s . He died in 2013 and is survived by his wife Betty (who, as Betty Brosmer, was an incredible glamour model in the 1950s).

True Weird lasted 3 issues, and was apparently (if not strictly technically) succeeded by True Strange, which ran for 7 issues. True Strange followed mostly the same format as its predecessor: “true” stories about historical oddities, ghosts, and so forth. The cover of True Weird’s second issue depicted Abraham Lincoln (the other 2 covers are the one we’re looking at today, and the one with a large image of the Devil), while 6 of the 7 True Strange covers (all painted by Thomas Beecham) featured contemporary celebrities: Elvis Presley (twice--one solo cover and sharing a cover with Bill Haley), Marilyn Monroe, Sophia Loren, Anita Ekberg, Bill Haley, and James Dean. This was probably an attempt to improve newsstand sales, although trying to connect these people with the supernatural was a stretch in some cases (“Did the Devil Send Elvis Presley?”, “The Weird Sex Magnetism of Anita Ekberg” and “The Miracle That Made Sophia Loren a Star”) but easier in others (“James Dean Speaks from the Grave”). True Weird’s covers, on the other hand, seemed aimed at readers interested in more esoteric topics.

True Weird’s first issue, shown here, was dated November 1955. One writer calls it “an exuberantly trashy magazine that offered articles on historical oddities and mysteries.” The cover is a trash-literature classic, showing a bikini-clad woman surrounded by “Fish With Human Hands.”

This cover was painted by Clarence Doore (who also painted the “Abraham Lincoln’s ghost” cover for True Weird #2). Doore, born in Montreal in 1913, moved to the United States with his parents as a child (his parents were both U.S. citizens). Doore began working as an illustrator in the late 1930s, serving in the Army during World War II. He painted covers for pulps, comic books, paperback books, and men’s magazines, retiring in 1966. Doore died in 1988.

Doore, although not a household name (not even in households where pop culture artists’ names are common currency), has a solid reputation even today: a cursory online search brings up a number of references to him and examples of his work. His cover painting for True Weird’s first issue is quite popular on the web: numerous bloggers snark on it and numerous image sites reproduce it. It was never immortalised in a song by Frank Zappa in the manner of Wil Hulsey’s painting “Weasels Ripped My Flesh” (first seen on the cover of Man’s Life, September 1956), but it’s still well known among aficionados of such things. The original painting sold for $18,750 in a 2015 auction (none of 7 other Doore paintings sold by Heritage Auctions went for more than $3,000 and several sold for less than $1,000).

The True Weird cover is fine, well-rendered and dramatic. It combines horror and sex, a familiar and effective combination in popular culture. “Nature attacks” covers on men’s magazines--like Man’s Life mentioned above--seem to be slightly tilted towards rugged outdoorsmen battling hostile weasels, crabs, turtles, rats, bats, sea snakes, spiders, baboons, wildcats, scorpions and so on. On some of the covers a woman-in-peril is also present, and a relatively small percentage feature a woman as the primary or sole target of ferocious fauna. “Monster attacks” artwork, on the other hand, often specialises in female victims. Doore’s cover shows only one person, a young woman wearing a red bikini, confronted by 2 fish-men. “Nature attacks” covers, even those featuring a female victim, usually portray the predators as solely interested in killing the human(s) in their midst, whether to eat them or simply out of savage spite. “Monster attacks” illustrations, on the other hand, often have an inherent undertone of sexuality. So file “Fish With Human Hands Attacked Me!” in the “Monster attacks” genre.

The fish-men on the magazine’s cover are partially obscured by water and mist; the story’s main illustration (drawn by Warren Knight, scroll down) inside this issue of True Weird shows a single fish-man--who does resemble Doore’s version--standing upright, suggesting the creature is a true fish-man (with arms and legs), not just a “fish with human hands.” As I discussed in a previous post, 1954’s Creature from the Black Lagoon helped popularise the fish-man (or frog-man) in popular culture.

One odd point is the fish-men’s eyes. Those horizontal, slit-like pupils give me the creeps. Seriously, goats have pupils like that, and they bother me as well. The Creature from the Black Lagoon has round pupils, why don’t these fish-men? The interior illustration depicts its creature with similar eyes, suggesting either the original story describes them thusly, or Doore & Knight collaborated on the imagery of the fish-man (i.e., one of them used the other’s artwork as a model).

The cover painting differs significantly from the interior artwork: Doore’s woman-in-peril is clearly a contemporary skin diver, given her bikini, face mask, and spear-gun, whereas Knight’s drawing shows a single monster grabbing a woman in 16th -century (I’m guessing) garb, as an armour-clad conquistador and four other men attempt to rescue her. The caption says the scene takes place on a “lonely Nicaraguan beach,” during the Spanish Conquest period. None of this is reflected in the cover painting, of course, presumably because the editors figured a modern setting for a fish-man assault on a woman would sell more copies of True Weird. However, Knight’s interior drawing does make the fish-man’s intention slightly clearer: he’s abducting the woman, possibly for nefarious & sexy purposes, whereas the two menacing fish-men on the magazine’s front cover might only be considering murdering the young woman (and then eating her, or not).

In Creature from the Black Lagoon, the Gill-man’s attraction to Julia Adams is romantic, if not (for biological reasons) sexual. Humanoids from the Deep (1980) depicts fish-men who kill men and rape (some) women, romance be damned. Having not read the “Fish With Human Hands Attacked Me!” story, I don’t know what the fish-man’s purpose was, but some human-like motivation is assumed. It’s not just their hands that are human, if you get my drift.

It’s a bit of a mystery why the first issue of True Weird has a gaudy, exploitative cover, and the second and third issues have more strait-laced artwork on their covers (if you can call a giant Devil looming over a stylised medieval city “strait-laced”). True Weird almost appears to have deliberately walked back from the policy of their eye-catching first issue, choosing a more sedate, “serious” tone. Sales may have played a factor: issue 1 was cover-dated November 1955, #2 February 1956, and #3 May 1956, giving the editors enough time to review the sales figures for each preceding issue. One supposes the news wasn’t good--True Weird folded, and True Strange wouldn’t appear until October 1956, at which time the Weider group made the decision to showcase current celebrities on the covers (James Dean, on the cover of the March 1957 issue, had died in September 1955 but was possibly even more famous after his death than while he was alive).

If you ask me, a more powerful sales gimmick would have been to showcase publisher Weider’s wife Betty Brosmer on every cover. One month she could have been a sexy witch, then a sexy vampire, then a sexy werewolf, then a sexy zombie, then a sexy ghost, then a sexy fish-woman…

#true weird#monsters attack#nature attacks#betty brosmer#joe weider#creature from the black lagoon#1950s magazines

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“A Picture Crammed With Guts!” (Shield for Murder, 1954)

Shield for Murder was a 1954 crime film adapted from a novel by William P. McGivern, co-directed by and starring Edmond O’Brien as a “Dame-Hungry Killer-Cop” who “Runs Berserk!” Shut up and take my money! The posters for this movie, released through United Artists, have a number of interesting, exploitative touches--so let’s start deconstructing, shall we?

Edmond O’Brien had a long career on the stage and in films and television; most often seen in second-lead and supporting roles (winning an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor for The Barefoot Contessa), he did play some “character leads” in pictures like D.O.A. and Shield for Murder. He retired from performing in 1974 and died a decade later. While reasonably handsome as a young man, O’Brien quickly aged into a sort of a stolid, slight-paunchy “everyman,” frequently cast as a cop or press agent or lawyer or military man. In addition to co-directing (with Aubrey Schenck) Shield for Murder, O’Brien directed some episodic television and one other feature film (Man-Trap, 1961, which he also co-produced but did not appear in).

Shield for Murder is about a schlubby cop named Barney (O’Brien), who kills a “runner” for a bookie and steals $25,000 from him. The mob doesn’t like being ripped off and pursues Barney, who winds up murdering an innocent witness to his initial crime and a private detective, and even slugging his former partner. He tries to skip town with his girlfriend but winds up being shot to death by his fellow policemen.

The “poster” for Shield for Murder we’re examining today may not actually be a film poster. The same image--minus the “Dame-Hungry Killer-Cop Runs Berserk!” text--was used for the one-sheet (the National Screen Service information at the bottom of the poster verifies this), and thus it is possible that this augmented version was a magazine ad or something of the sort (it’s not the pressbook cover, though). However, I like the “Dame-Hungry Killer-Cop” tagline so much that I decided to use this one (the authors of the recent BluRay release also chose this version for their cover).

This is one of the “yellow background” posters I’ve mentioned before, a design quite popular in the 1950s (or perhaps it was just popular with one ad agency who was creating posters, and I’ve just happened to see a lot of them). The design is clever and effective, with a smaller box inside the outlines of the poster itself, but a box which is ruptured by Edmond O’Brien’s head at the top and by a small, borderless text “balloon” in the lower right. The yellow background attracts attention, but the interior box frames most of the graphic imagery against a white background.

Curiously, the large figure of O’Brien and the thumbnail illustration in the lower right are black-and-white, while the image of Marla English (at left) and the photo-sourced picture of O’Brien kissing Carolyn Jones (at right) are in colour. I don’t know the rationale behind this decision, but it actually works, at least for the full-length art of O’Brien--the lack of colour ironically makes it stand out against the colourful backdrop. The verified one-sheet for the movie has all of the images in colour. Both posters are fine, but I still prefer the “Dame-Hungry Killer-Cop” version.

The central artwork, while certainly competent, is odd in another way. It’s not a very good likeness of O’Brien, looking too young and handsome (compare the figure’s face to the smaller image of O’Brien at right). Indeed, it slightly resembles a younger O’Brien/William Bendix hybrid, with maybe a little early Wallace Ford mixed in. Also, he has a rather quizzical look on his face, not much like a “killer-cop.” I imagine this image may have been photo-sourced as well (many film posters, even though that used artwork rather than photographs, sourced at least some of their imagery from publicity stills): I’ve seen a screen shot that shows a sweaty O’Brien with a pistol in one hand and a stack of cash in the other, but he’s wearing a police uniform and isn’t in the same pose as the artwork. This doesn’t mean a publicity shot of more or less like this image didn’t exist, but even if it did, that doesn’t excuse the apparently deliberate glamourisation of the film’s flawed protagonist/anti-hero. Also, he’s wearing loafers.

The other images are probably all retouched photographs. Although I haven’t been able to locate the exact stills used, I’ve found a reasonable facsimile for the O’Brien-Jones smooch here, and the pistol-whip image here. The closeup of bad-girl Marla English could have been taken from almost any glamour shot of her.

The text on the poster is both strategically placed and fantastically hyperbolic in content. As noted above, the giant red lettering reading “Dame-Hungry Killer-Cop Runs Berserk!” is only present on this version. It doesn’t obscure much of the artwork and adds some much needed emotional punch and provides the potential audience member with important information. He’s a crooked cop! He kills people! He likes “dames!” And he’s running “berserk!” So you’ve got a pretty good idea of what to expect. The taglines beneath the picture at right reinforce these attributes: he’s got a “wild trigger finger,” “a lust for money,” and a “weak spot for fast blondes,” who left the “straight-and-narrow” and went down a “crooked one-way road!” Got it.

That text was primarily descriptive rather than qualitative, suggesting the studio was too modest to claim that Shield for Murder was “Terrific!” or “Packs a Punch!” The last bit of non-credits text, hovering about the pistol-whipping art, tries to make up for this, but in a rather diffident manner. “If ever a picture was crammed with guts--this is it!” “If ever?” Aren’t you sure? The phrase “crammed with guts” is a good (if awkward) one, albeit surprisingly graphic for the time period. The phrase is “tough,” gangster-ish talk that meshes with the theme of the film, but it’s still surprising to see it on a movie poster intended for a mass audience. Maybe the distributor thought the intended audience for Shield for Murder could handle it: the movie is clearly a hard-boiled crime picture and anyone who’d be offended by “crammed with guts” probably wouldn’t want to see Shield for Murder anyway.

The rest of the poster text is just the title and credits information. The pyramidal layout of “Edmond O’Brien” and “Shield for Murder” is aesthetically pleasing: the star’s name is between his legs and he’s standing on the film title, with the rest of the credits outside of the framed white area. This is all more or less contractually-required boiler-plate and had little to do with selling the picture, but I’m a little surprised by the extremely large print for “A SCHENCK-KOCH Production.” Aubrey Schenck and Howard W. Koch were producing partners for most of the 1950s, grinding out mid-level genre pictures like Shield for Murder, Big House U.S.A., The Black Sleep, Voodoo Island, Tomahawk Trail and Fort Yuma. It’s unlikely that any potential ticket-buyer would have recognised their names and/or cared enough to make a see/don’t see decision based on this information, but this may have been an attempt at “branding.”

In any case, the Shield for Murder poster is competently executed, effectively conveys the subject matter and tone of the film itself, and invites the viewer to ascertain for himself (or herself) if there ever was “a picture crammed with guts!” (Aside from The Goofy Movie, that is)

0 notes

Photo

“Your girl will gasp with wonder…” (Glow in the Dark Neckties)

The “Glow In the Dark Necktie Company” (215 N. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL) seems to have been a classic “niche” company. “We know our market. We make glow in the dark neckties, that’s all.” There is very little information on the web about this business (the address still exists but appears to be a more modern high-rise office building), which advertised in comic books, newspapers, and popular magazines during the 1940s. At least 3 different designs were offered in this era, one “patriotic” and 2 risqué (one moreso than the other).

The earliest necktie design for which I’ve been able to find an advertisement is for the “Blackout Necktie.” It shows up in a multi-item ad that appeared in Blue Bolt 3/7 (December 1942): the tie is said to glow “in dark for 20 minutes after exposure to electric light” and cost $1.00. By December 1943 the tie was now called the “Victory Necktie,” and the price had dropped to $.98 (plus postage). Advertisements for this version appeared throughout 1944 in newspapers, pulp magazines, and comic books. One assumes, since the ads in 1943 and beyond made a point of referring to the tie as the “Victory (also called Blackout) Necktie,” that the design was the same from the beginning, but the 1942 ad neither provides details nor shows the tie clearly enough to determine what it looks like.

Renaming the tie from “Blackout” to “Victory” reflects (perhaps not unconsciously) the shift from a defensive posture and attitude in World War II to an offensive one. The USA had been attacked in December 1941: civil defense precautions were instituted, and “blackouts” were a common-place thing, often mentioned in popular culture. By late 1943, the Allied war effort was making progress, and it was permissible (even encouraged) to look forward to ultimate “Victory” over the Axis. The ad copy mentions the patriotic design in passing, referring to the “strange, luminous pattern of the patriot’s universal fighting code. . . . - - - “V!” and later describing the design as “the fighting man’s…Victory Code.”

Otherwise, the tie’s aesthetic and utilitarian attributes are the selling points. By day, the tie is “wonderful” as well as “stylish, wrinkleproof, high-class…fine material…Ties up perfectly!” At night, the glow in the dark design has “magic beauty,” produces “the most unique effect you have ever seen” and “its [sic] actual protection in blackouts, or dimouts, for its light can be seen at a distance.” Avoid being struck by cars while crossing the street in a blackout! Driver: “My gosh, I nearly ran you over! Lucky you were wearing that luminous necktie! I’d hate to have injured such a patriotic individual!”

[As an aside, the exact technology used to create the glowing effect is not known, but it was probably not paint containing radium. This was notoriously used on wristwatches, which had resulted in horrible injuries to the women who manually painted watch dials. You can look it up, but I’d advise skipping the photographs. Radium glows because it’s radioactive, and the original “Blackout Necktie” advertisement (although none of the later ones) refers to charging up the tie by exposing it to an electric light, which indicates the tie has a phosphor substance embedded, rather than radium.]

The ad reassures readers that the tie bestows true distinction and pride of ownership upon those fashionable individuals willing to part with 98 cents (plus postage) to purchase a tie (or 3 for $2.79). “Creates a sensation wherever you go…Everywhere you go, by day or night, your Victory…Tie will attract attention, envy, and admiration…both men and women rave about its magnificent beauty…”

Eventually, World War Two came to an end and there was little inherent value in wearing a tie emblazoned with three dots, three dashes and the capital letter “V.” Unless you were a Morse code fanatic, or your name was Victor. The Glow in the Dark Necktie Company, never one to rest on its laurels, came up with two new designs.

The “Kiss Me Necktie” was actually available even before war’s end, since an advertisement can be seen as early as Dynamic Comics 15, cover-dated July 1945 (and printed several months before that). The price has escalated to $1.49 (plus postage), perhaps because this tie doesn’t merely affirm your patriotism, it issues “a Call to Love in Glowing Words!” “Your girl will gasp with wonder!” The “Kiss Me Necktie” will “surprise and thrill every girl you meet!” (in the dark) “Be different and the life of the party in any crowd!” (in the dark) “See how it excites and thrills.” (in the dark) Yes, “in the dark it seems like a necktie of compelling allure, sheer magic! Like a miracle of light there comes a pulsing, glowing question--WILL YOU KISS ME IN THE DARK, BABY?” Sure, but only if you keep the tie on and the lights off. Once the lights are on, the spell is broken, jerkface.

There is slightly more artwork in the “Kiss Me Necktie” ad than in the “Victory Necktie” version. We get the identical little drawings of Daytime Man and Nighttime Man (whose face inexplicably turns black when his tie lights up, possibly due to radium poisoning…), but in keeping with the babe-magnet concept of the “Kiss Me Necktie,” there are 3 drawings of women admiring the tie itself--bow down to the Almighty Tie!--and one of a kissing couple, presumably before-and-after depictions of the tie’s magic power. Why, it’s “a Hollywood riot wherever you go!” (sounds good, sign me up!)

The coupon for the “Kiss Me Necktie” includes the standard offer of one tie or multiple ties, but also throws in an additional, surreptitious opportunity, the chance to purchase a “Glowing Gorgeous Pin-Up Girl Necktie.” Could this be the same item later offered as the “Strip-Tease Necktie” by our old friends at the Glow in the Dark [Neck]Tie Company, beginning in 1947? “She Loses Her Clothes As She Glows in the Dark.”

The ads for the Strip-Tease Tie differ from its predecessors in several ways. First, they appear not in comic books, but in magazines like Popular Science and Modern Detective between (at least) 1947 and 1950. Also, they aren’t full-page, but appear as a one-column, black-and-white ad, often “stacked” with offers for other dodgy products (in Modern Detective, the Strip-Tease necktie ad is below one for mail-order false teeth, and above ads for an asthma remedy and a mail-order detective school). Obviously, the Strip-Tease Tie is an “adult” product, offered only to discerning grown men who read serious magazines rather than those frivolous, juvenile comic books. And even then, the tie is only “for men who demand the distinctive and unusual!”

Given the smaller size of the ad, there’s less redundant descriptive text. The tie will “Bring[s] gasps of sheer wonder [and] thrilling admiration the first time you wear it!” (but every time you wear it after that…nothing.) It won’t save you in a blackout or compel women to kiss you, but it does depict “a glorious goddess of light revealed for all to see! A glorious, gleaming blonde beauty revealed in daring pose in the briefest of costumes, mysterious and magnificent!” Definitely worth the increased price of $1.64 (plus postage), because the briefest of costumes, that’s why.

Of the 3 neckties on offer in these ads, one imagines the “Victory Necktie” was the most versatile (or least offensive), although its topical relevance after 1945 was seriously diminished. The “Kiss Me Necktie” would have to be hidden under one’s coat until just the proper moment--when you’re in the dark and in close proximity to someone you’d like to kiss. Otherwise, it’s just awkward (you wouldn’t want to flash it while sitting in the cinema with your grandma, would you now?). The “Strip-Tease Necktie” isn’t fit for mixed company: wear it to your lodge meeting, to poker night with the guys, or when you visit the local gentleman’s club, but avoid wearing it to midnight mass on Christmas Eve or to a candlelight vigil.

Sadly, the Glow in the Dark Necktie Company is no more. I blame Casual Fridays.

0 notes

Photo

“Needs More Lightning Bolts!” (House of Horrors Realart film poster)

In the days before television, home video, and the internet, most films effectively vanished after their theatrical release. Film exhibition often involved a circuitous path (roadshow for some, then first-run, sub-run, etc.) but once a film was played out, it went into the vaults. Extremely popular movies (The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind) could be periodically re-released nationally, but this wasn’t a widespread practice.

There were companies that specialised in re-releasing older films for lower-tier cinemas. Some films were resurrected when a new marketing aspect appeared (for example, a supporting actor suddenly shot to stardom, or a particular theme became topical), others were simply given a different title and exhibited in hopes that audiences wouldn’t remember (or care) that they’d seen it before. [Or, given the vagaries of exhibition, it’s very possible that someone living in a town with only one or two cinemas had never had the opportunity to see 50% or more of Hollywood’s annual output because those films never played in their local theatres when new. No television or home video, remember.]

The re-release sector of film distribution had existed for years, but became more prominent in the late 1940s. The Paramount Decision of 1948 compelled the vertically-integrated major studios to divest themselves of one aspect of their organisation (most chose to drop exhibition), and the studio system began to slowly crumble. The eight "majors" released 363 feature films in 1940; by 1950 this total dropped to 263, and in 1955 it was only 215. To compensate for this shortage of new product, cinemas began to show more independent films, foreign movies, and re-releases.

The two predominant re-release companies of the era were Astor Pictures and Realart. Astor Pictures released independent films (and late in its existence, some prestigious foreign movies) as well as re-releasing older studio product, and lasted from 1930-1963. Realart was founded in 1948, and had a 10-year lease on Universal films made between 1930 and 1946. It didn’t, obviously, release all of Universal’s output from these years, just those which seemed saleable: this amounted to 34 movies in Realart’s first year, 48 in the second season. The ten-year contract was in some ways prescient, since at the end of the 1950s even the major studios were selling their back catalogs to television, limiting the market even further for theatrical release of old movies.

While Realart’s rentals included pictures by directors like Alfred Hitchcock (Shadow of a Doubt), “classics” such as All Quiet on the Western Front, and those starring John Wayne (Pittsburgh) and other “A”-level actors, the company’s bread-and-butter was the Universal horror film catalog, with numerous entries in the Frankenstein, Dracula, Mummy, Invisible Man, and Wolfman series, not to mention team-ups and one-shots. One of these horror-film re-releases, House of Horrors, is the focus of today’s examination.

House of Horrors was originally shown in 1946, and Realart re-released it six years later in 1952. The film deals with an ill-tempered, impoverished artist who rescues a brutish, facially deformed man from drowning and utilises him as the model for a sculpture of "the perfect Neanderthal man." Out of a twisted sense of gratitude, “the Creeper” murders the artist’s enemies. This film, and the subsequent The Brute Man (produced by Universal but released by PRC after Universal became Universal-International and stopped making “B” pictures…for a while) both star Rondo Hatton, who suffered from acromegaly and became a cult figure many years after his death.

While there are similarities between the two ad campaigns, “Realart put fresh coats of paint on campaigns they inherited from Universal. Posters were new and sometimes more arresting than originals.” Today we’ll compare the half-sheet for the 1946 Universal original and the one-sheet for Realart’s re-release.

[As an aside, Universal's one-sheet for House of Horrors is quite nice as well, but its design is significantly different than the half-sheet--with entirely different images--and thus doesn't match up as nicely with the Realart poster. It's interesting to note that the House of Horrors Universal one-sheet is quite similar in layout and content to the 1943 poster for Universal's Son of Dracula.]

Both the Universal poster and the Realart version sell House of Horrors as a thriller/horror movie, with Rondo Hatton’s “the Creeper” as the monster. [Ironically, there was an independent film titled The Creeper released in 1948, but it had no relation to Rondo Hatton’s character, instead dealing with a mad scientist whose hand turns into a cat’s paw. Really.] The essential elements of the two posters are the same: a large portrait of menacing Rondo Hatton, and a photo of a cowering blonde. The Universal half-sheet adds photo-sourced portraits of Robert “Batman” Lowery, Virginia Grey and Martin Kosleck, while the Realart poster substitutes painted artwork, to be discussed shortly.

The tagline on the Universal posters (both the one-sheet and the half-sheet) is simply “Meet the Creeper!”, an indication the company envisioned Hatton’s character as a continuing one, but also evidence that he was the designated “monster” (“Meet the Murderer!” is not as evocative). Realart’s marketing team opted for different phrases on their one-sheet and half-sheet. The one-sheet bills Rondo Hatton “as the Creeper” but the tagline is “Monstrous Murderer of Artists Models!” while the half-sheet ballyhoos “Beautiful Artists Models and a Beastly Killer!” [Someone didn’t like apostrophes.] Both phrases are considerably more exploitative than the text on the Universal posters.

Lest one criticise both the Universal and Realart publicity departments of blatant cheesecakery (although “sex sells” was probably discovered by the very first ad man, back in prehistoric times) due to the inclusion of the scantily clad blonde on the posters, the film itself provides some justification: while Martin Kosleck’s character is a failed “serious” artist, Robert Lowery’s art career is much more successful, dedicating himself as he does to painting pinup girls. The blonde on the posters is Joan Fulton (later known as Joan Shawlee), one the models-- in the film’s narrative--for the aforementioned cheesecake artwork.

While the Universal poster image of Joan is from a publicity still for House of Horrors, suitably colourised, the Realart one-sheet is retouched to depict her in a strapless gown that exposes her shoulders and 75% of her breasts (but covers up her bare mid-section--no visible navel, though, that was forbidden). Curiously, the Realart half-sheet uses a different publicity still of Fulton--one in which she’s standing, albeit still in a “horrified reaction” pose--but once again puts her in the more revealing red dress outfit rather than the halter-and-skirt combo.

Aside from the costuming of the "woman in peril," the biggest difference in the two posters is the depiction of the Creeper. The Universal half-sheet features a photograph of a menacing Rondo Hatton, while the Realart posters replace this with artwork. And what artwork!

Many of the Realart re-release posters--especially for the horror movies--utilised retouched photographs in a montage style; those consisting primarily or wholly of new artwork are relatively rare (All Quiet on the Western Front and Saboteur are two examples). The posters for House of Horrors contain a photographic element but the artwork predominates (the Realart half-sheet for Night Monster is also a mix of art/photo).

The image of the Creeper on the Realart one-sheet for House of Horrors was clearly modeled after the publicity photo used for the Universal half-sheet, but the artist eschewed a realistic style (because you could just use the photo itself if you wanted realism, right?) and let his/her freak flag fly. The Creeper is rendered in garish yellow-and-green, he loses one hand and the other is displaced to the lower left-hand quadrant of the poster (the better to menace the blonde). [In the Realart half-sheet, the Creeper keeps both hands, which surround the blonde, and it's obvious that these were copied from the still used for the Universal half-sheet.] But best of all...HE SHOOTS LIGHTNING BOLTS FROM HIS EYES!!

Sure, in the film itself, the Creeper is just a strong, rather dim-witted sociopath who murders people by strangling them, but film marketers never let the "facts" get in the way of a compelling movie poster. [Exhibit A: The Wasp Woman poster.]

The artist also added artwork of a spooky old house (although the film is set in a big city) and some decorative green, yellow, black, and purple swirlies for atmosphere. The art isn’t particularly accomplished, but has a nervous energy and flair that compensate. “This movie is exciting, one might even say…shocking!” the poster implies. Did audiences really expect to see a movie in which the monster kills using eyeball-lightning? Probably not, but there was always that possibility…maybe this time the poster won’t be just hyperbole…

Although created for the same film just 6 years apart and featuring much of the same content, the two posters for House of Horrors are considerably different in tone. Universal, while it wasn't one of the "big five" (MGM, Warner Bros., Paramount, 20th Century-Fox, RKO Radio), was a major Hollywood studio, albeit one that made a lot of economical, popularly-focused product (lowbrow comedies, musicals, genre pictures, serials). Its horror film posters were atmospheric, glossy, dramatic, even "classy," despite the genre, and the House of Horrors poster shown here illustrates that.

Realart, on the other hand, was renting its product to theatres which were desperate for product, not worried about showing "old" movies, probably located in smaller communities, and--certainly in 1952, when House of Horrors was re-released--battling the encroachment of television. This required a harder sell, with more garish poster design and content. The television-jaded audience demanded thrills in exchange for putting on trousers, driving to the cinema and paying for their entertainment, instead of sitting at home in one’s underwear and watching the home screen for free. House of Horrors (the film) may not necessarily have provided these thrills, but House of Horrors (the poster) promised them.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

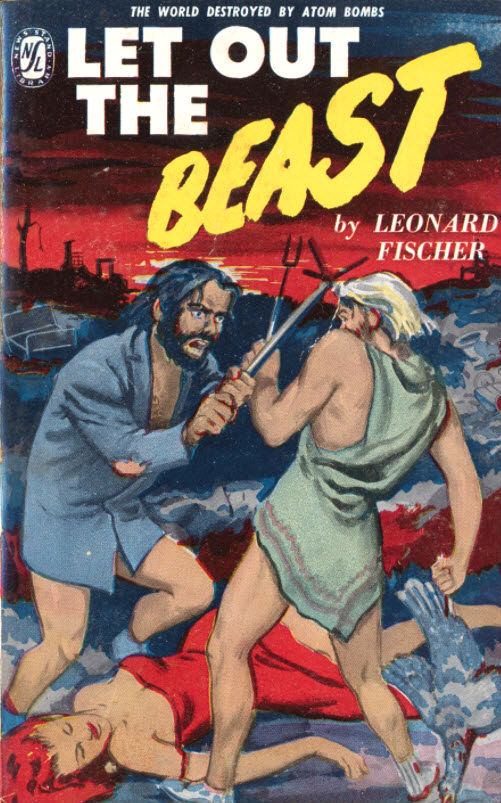

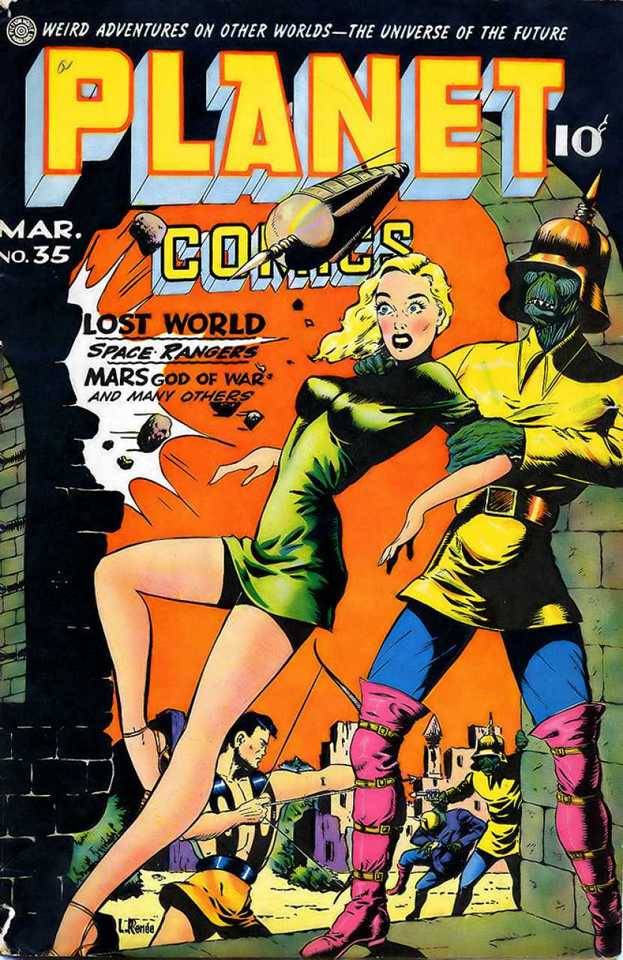

Post-Apocalyptic Fashion Show: "Let Out the Beast" (1950) and Planet Comics 35 (1945)

What does one wear after the apocalypse (assuming you’re one of the survivors, of course)? Pop culture has some suggestions, from “whatever you were wearing before the apocalypse” to “rags & furs” or, perhaps, “futuristic outfits.” Today’s essay takes a look at two extremes, the 1950 Canadian paperback “Let Out the Beast” and Planet Comics 35 (March 1945).

“Let Out the Beast” was written by Leonard Fischer, about which little is known (one website gives his birth/death dates as ?1903-?1974), and who doesn’t appear to have written any other books, at least under this name. Although I’d never heard of this novel before, it’s apparently rather well-known, as least among post-apocalypse literature aficionados, although it doesn’t exactly have a stellar reputation: “There are tons of novels and short stories better than this effort…” , “badly written…inept” and “I tried to read this but it was, without a doubt, the worst novel I've ever started” are typical comments.

The book was published by Export Publishing Enterprises in January 1950, in both Canadian and U.S. versions, and does not seem to have ever been reprinted. The highly readable and informative Fly-By-Night website indicates Export published 28 paperbacks in U.S. editions, and 20 of these had dust jackets, a rare but not unknown phenomenon. The dust jacket for “Let Out the Beast” is a stylised image of an explosion, with the tag-line “The World Destroyed by Atomic Blast in 1965,” whereas the cover of the actual paperback is what we’ll examine here (where the tag-line is much smaller and simply reads “The World Destroyed by Atom Bombs”). Most of the Export dust jackets featured similarly toned-down and symbolic images as opposed to the representational art on the covers of the books themselves, presumably to allow these rather lurid, exploitative novels to be sold in more conservative venues.

The actual cover of “Let Out the Beast” was the work of artist D. Rickard; Fly-By-Night discussed him a number of times, but concrete information is hard to come by. It seems his name was Douglas Rickard and he probably worked for a Toronto advertising agency at one time. “He was one of only two artists to have worked for the big three publishers” of the era, painting numerous covers in the 1949-53 period but apparently vanishing afterward (possibly because his market dried up: Export went out of business after a fire in late 1950, White Circle ceased publishing in 1952).

The cover of “Let Out the Beast” depicts two men fighting over a woman in the middle of a post-apocalytic, ruined landscape (or possibly a municipal garbage dump…or maybe Detroit). The man on the left is clad in what appears to be a sports jacket, buttoned for modesty’s sake, since he doesn’t seem to be wearing anything underneath it. So, you found a coat but you couldn’t find any trousers? His blonde opponent wears a toga and tennis shoes, although it’s just as likely that the “toga” is a repurposed table cloth. This is a better look than jacket-no pants, however: at least a toga is a recognisable article of clothing, whereas Blackbeard resembles a pre-apocalypse flasher (who is also wearing tennis shoes or--given this is a Canadian novel--“runners”).

Let’s stop to consider the no-pants world of “1965” (when “Let Out the Beast” takes place). In the modern Western world, trousers have been popular for quite some time (even the Scots generally wear kilts only for ceremonial occasions now), and if the atomic cataclysm of 1965 destroyed the world’s supply of pants, this would be one more source of anxiety for the (male) survivors. It’s going take some getting used to, all this fighting for survival and such, especially if you’re going commando, the full Monty, free-balling, whatever.

The unconscious redheaded woman on the cover wears a standard (for pulps, paperbacks and other pop culture literature) dress--which is to say it exposes her shoulders, 50% of her bosom, and her legs--not much the worse for wear. Perhaps Blackbeard is battling Toga-Man for the right to claim her outfit (alternately, one might cynically speculate that she’s dead and the men are fighting for the right to barbecue and consume her corpse).

Attire aside, there are some other things to like about this cover. Notice their weapons: Toga-Man has a barbecue fork, while Blackbeard is wielding what looks like a microphone stand. Also, Toga-Man apparently believes a bird in the hand is worth two on the barbecue fork. The background features mostly indistinguishable garbage, but a bed (on the left) and a toilet (on the right) can be glimpsed, which unfortunately only reinforces the impression that this cover doesn’t really depict desperate men struggling to survive the apocalypse, but a confrontation between two impoverished people in a landfill. Or, as they might say in Mexico, a pleito entre pepenadores (a clash between trash scavengers).

The art on Canadian original paperbacks in this era, whether by D. Rickard or anyone else, tends to be less polished than contemporary U.S. paperback covers. This is not necessarily a negative value judgement, since Canadian publishers were drawing from a smaller pool of artists, selling to a smaller potential audience, and were thus constrained financially and technically. Nonetheless, and contrary to the opinion of some people, I like the cover of “Let Out the Beast.” It’s a bit “naïve” but isn’t artistically incompetent, does convey the basic theme of the novel (mankind reverting to savagery), and is rather eye-catching.

The second entry in our Post-Apocalyptic Fashion Show is the cover of Planet Comics 35 (March 1945). Planet Comics was published by Fiction House, a company that put out both comic books and pulp magazines. In both media, Fiction House specialised, although not exclusively, in certain genres: science fiction (Planet Stories and Planet Comics), jungle tales (Jungle Stories, Jungle Comics, Jumbo Comics), and aviation-themed (Wings pulp and Wings Comics). [They also put out Fight Stories and Fight Comics, but the pulp was boxing oriented and the comic was generic action.] The pulp magazines were certainly aimed at a somewhat older, presumably more literate audience, but Fiction House comics--as evidenced by their cheesecake-laden covers--were also a bit more "adult" than many of their competitors' works.

Planet Comics ran from 1940 until 1953 (Fiction House got out of the comic book business in 1954). Although most of the Fiction House titles were genre oriented rather than "starring" a single character, there were recurring series in their comics. Planet Comics featured space heroes like Flint Baker, Reef Ryan, Gale Allen, Star Pirate, Mysta of the Moon, and Auro, Lord of Jupiter. Another continuing strip was "The Lost World" (issues 21-69), set in the 33rd century: "Civilization on Earth died--crushed by the inhuman Volta hordes--but Hunt Bowman and Lyssa lived and roamed the devastated planet."

The cover of Planet Comics 35 is based on "The Lost World" strip, and depicts Lyssa in the grip of a Volta Man, while (in the background) Hunt wields his bow-and-arrow (his name is "Hunt Bowman," after all) against the despotic conquerors of Earth. Since we're concentrating on post-apocalyptic fashion in this essay, let's admire the wide variety of costumes on display here. But first, a few words about the cover artist, Lily Renée. One of a relatively small number of female artists who worked on comic books in the "Golden Age," Lily Renée Wilhelm was born in Austria in 1925 but her family fled the country after the 1938 Anschluss which left the country under Nazi domination (the Wilhelms were Jewish). Eventually, Lily and her parents wound up in the USA and the artistically-talented teen went to work for Fiction House, which was trying to replace male artists drafted into the armed forces. Renée worked for Fiction House and other publishers until the mid-1950s. She was (much later) re-discovered by feminist cartoonist Trina Robbins and feted by comics fandom.

On the right-hand side of the cover is a Volta Man. The primary menace in most (but not all) of the "Lost World" saga, the Volta Men appeared in the very first series story (Planet Comics 21) but looked considerably different than their later incarnation: their faces were yellow and skull-like, and they wore space-type helmets with spikes on the top. However, it was not until the next time they showed up (Planet Comics 25) that their classic "look" emerged--sort of a green, mummified Creature from the Black Lagoon-ish face, and a helmet definitely reminiscent of the German military pickelhaube. This story was drawn by Graham Ingels, best known for his later work for EC horror comics in the 1950s, and subsequent artists, including Lily Renée, would follow his lead. [It's probably not a coincidence that the change in the appearance of the Volta Men--from generic aliens to quasi-German soldiers--occurred in 1943, right in the middle of World War II.]

The Volta Men on this cover are garbed in their familiar outfits, although the unknown colourist went wild, giving the main figure a golden helmet (instead of grey), a yellow tunic and blue leggings (instead of uniform military green) and absolutely fabulous fuschia boots (rather than the boring black ones seen inside the comic). It might also be noted that one of the other Volta Men in the background has a blue tunic--in the actual series, the Volta Men were rarely individualised and were garbed identically. Still, it's a jolly look for the normally sinister alien invaders.

Lyssa, Hunt's main squeeze, is the primary focus of the cover of Planet Comics 35. Although her usual costume in the interior stories was a tight blue top (exposing lots of cleavage) and a red miniskirt (sometimes skin-tight red shorts--she later switched to a tattered red mini-dress), Lyssa obviously dressed up for her rare cover appearances. She's wearing a red mini-dress on the cover of issue 33 (also drawn by Lily Renée), and a tattered skirt & blouse combo on issue #30 (Joe Doolin art--he also changed the spike on the Volta Man's helmet to a shark fin!). For Planet Comics 35, Lily Renée went all out to create a slinky emerald green dress that showcases Lyssa's lithesome lines (although, ironically-- given the plentiful cleavage on display in the interior art--she's technically covered up to her neck).

In the background, Hunt is garbed in his usual leather suspenders and kilt outfit, proving that Planet Comics was not averse to beefcake in addition to cheesecake. It's amusing to compare the always clean-shaven, short-haired Hunt with the shaggy, scruffy looking battlers on the cover of "Let Out the Beast"--apparently an alien-invasion apocalypse is less disruptive to personal grooming than an atomic-war apocalypse.

[If you're interested, the cylindrical object partially obscuring the word "Comics" in the masthead is a reasonable facsimile of a Volta spaceship, pointy protuberance (which resembles the Volta helmet spike) and all. I'm not sure why the craft is shooting, given that Volta soldiers are clearly in the target range. One assumes the warlike Volta are not averse to sacrificing their own troops to "friendly fire" if they can eradicate the pesky Hunt and Lyssa.]

The covers of "Let Out the Beast" and Planet Comics 35 share a similar but not identical vision of the future. Both covers depict deadly struggles in a post-apocalyptic, ruined landscape. While D. Rickard clothes his disheveled opponents in cast-off rags, Lily Renée presents a future where the opposing sides are both stylishly clad. In "Let Out the Beast," the survivors are armed with makeshift weapons, but Planet Comics shows that alien high-tech (ray guns, a spaceship) can be effectively countered with a traditional Earth weapon (a bow-and-arrow). On the cover of the Canadian novel, we see a fight for survival between two humans: symbolic, because humanity has destroyed itself in atomic war between "Americanada" (probably pronounced "Ameri-Canada" rather than "American-ada") and "Europasia." Planet Comics, on the other hand, is about the aftermath of an alien invasion of Earth, and the opposing forces--humans and Volta Men--are the antagonists in the artwork as well.

The media are different: "Let Out the Beast" is a paperback book with a serious theme: "... clearly intended as an awful warning..." about the moral consequences of nuclear holocaust. The novel was aimed at an adult audience and the cover, while mildly exploitative, reflects that. Planet Stories 35 is pulp-light, a space opera comic book whose readers would have been, on the main, younger than those for a text-heavy pulp magazine, let alone an actual novel.

So, a similar premise, depicted differently: but in both cases, the colourful, outré artwork is intended to catch a buyer's eye and hint at the fantastic content within.

#post-apocalyptic#science fiction#planet comics#lily renee#let out the beast#d.rickard#science fiction comic#golden age comic book#canadian science fiction#post-apocalyptic fiction

0 notes

Photo

Hey Mickey! Hey Minnie! Oh, wait… [The Skipper 459 and Ribtickler 2]

First seen on-screen in 1928, Mickey Mouse quickly became globally famous. From his very first cartoon, Mickey had a sweetheart: Minnie Mouse. In addition to the Disney animated cartoons, the anthropomorphised rodents appeared in various print media, were immortalised in song, and spawned a never-ending stream of merchandising tie-ins.

Very quickly there emerged imitators, bootlegs, and parodies of Disney’s falsetto-voiced, round-eared money machine. Where they could, Disney’s lawyers expressed their legal displeasure. Some homages, like “Mickey Rodent” (Mad, 1955) and Robert Armstrong’s ‘70s underground comix character “Mickey Rat,” skated by, while others--the underground comix created by Dan O’Neill and “The Air Pirates”--did not. It was obviously impossible to identify and prosecute all of the dodgy companies around the world making unauthorised Mickey Mouse toys, figurines and such (although clearly Disney would have liked to).

Today’s two objects of deconstruction represent “cameo” appearances of (pseudo-)Disney characters in pop culture which somehow avoided the wrath of Disney, possibly because they were fleeting and not overly egregious or mercenary.

The first example comes from the British “story paper” The Skipper, number 459 (17 June 1939), and appears to show Mickey Mouse and (possibly) Daffy Duck as opposing cricketers. It’s Disney versus Warner Bros. on the pitch!

British “story papers,” which flourished in the first half of the 20th century (they began in the 19th century, and a few hung on after 1950, but they were basically all gone by the early Seventies) are a publishing genre largely unique to the United Kingdom, although they bear a certain resemblance to American “dime novels” and pulp magazines in form and content. Story papers, sometimes called “boys’ weeklies” (there were some aimed at girls, however), had many fewer pages than pulps (usually 28 pages compared to over 100 for a pulp), were aimed at a juvenile audience, and often contained continued stories (feasible because of their weekly schedule).

The Boys’ Own Paper (which ran for more than 70 years), The Champion, The Gem, and The Magnet were among the most popular and longest-lived story papers (Girls’ Crystal was possibly the most popular story paper aimed at girls, lasting nearly 30 years). The contents varied: many, particularly in the 1920s, specialised in tales set in British “public schools” (which, as is often pointed out, were actually private schools, like Eton and Harrow); others were more or less straight adventure genre works, some focused on fantastic content, and others featured a variety of types of stories. Many stories were set in the American West, Canada, Africa, India, the Far East, and other “exotic” locations, to balance the stories about school hijinks, sport (especially football and cricket), and other traditional British topics and settings.

Additional material included editorials, readers’ letters, joke pages, contests, and premiums (such as photos of footballers). Most stories were illustrated (usually quite well) and in later years story papers would incorporate the odd comic strip (there were distinct “comic papers” as well).

Amalgamated Press was the predominant publisher of story papers but D.C. Thomson also put out a number of them (as well as the long-running comic paper Beano). The “Big Five” Thomson titles included The Hotspur, The Wizard, Adventure, The Rover and The Skipper.

The Skipper was published from 1930 until 1941, when wartime paper shortages resulted in its cancellation. Over 100 issues of The Skipper can be read online.

This issue of The Skipper contains 7 stories: 2 “school stories,” a Western, a cricket story, one set in Australia, one set in India, and a science fiction/crime tale that takes place on the Devon coast. The cover painting illustrates a situation from the “Big-Handed Arthur” cricket story. [The protagonist’s name evokes “Big-Hearted Arthur,” the nickname of British comedian Arthur Askey.] Arthur convinces an Australian cat-burglar to join his cricket team for a match, but both he and the burglar resort to wearing “huge and grotesque paper maché heads”-- “last seen in the Bidworth Hospital Carnival procession”--to avoid identification for their misdeeds. “Arthur was wearing the head of a merry looking mouse with large ears. Harold’s head was that of a duck.”

The Mickey Mouse resemblance is down-played on the cover art (and the interior illustrations don’t feature this scene), but the ears are definitely Mickey-ish, and the juxtaposition of an angry-looking black duck (one supposes the artist deliberately avoided making the duck white, to avoid the too-obvious Donald Duck comparison) and a cartoon mouse is certainly no coincidence.

The name of the artist who painted this and many other covers of The Skipper is not known. This particular cover is almost surreal, compared to the more or less realistically representational covers of other issues (some may have had odd comedic or fantastic content but realistic settings): we’ve got two cricketers with giant, cartoon heads on human bodies charging at each other (I know, this is part of the game, but it looks like they’re going to fight), and three “normal” players, apparently participating in a match taking place in a purgatory-like void. The blank white wall surrounding the pitch seems to indicate this is taking place in some sort of gladiatorial arena. Possibly the teams have been abducted by the Grandmaster and this is a preliminary for the much-anticipated Thor vs. Hulk rematch?

The second cover features a Minnie Mouse clone. Ribtickler was a comic book title used by Fox in the 1940s, then resurrected by Green Publishing and Norlen Magazines in the late 1950s. The later versions contained reprint material, but--oddly enough--not always from Fox comics! The cover shown here was used three times (they were really begging for Disney to complain, weren’t they?): for Ribtickler 2 (Fox, 1946), Ribtickler 8 (Green, 1957) and Ribtickler 8 (Norlen, 1959). The contents of all three comics were completely different, by the way: the Green version reprinted some Fox material but was mostly reprints of the “Noodnik” strip (previously seen in Comic Media comics and later reprinted by Charlton), and the Norlen comic contained re-used Charlton “L’il Genius” and “Timmy the Timid Ghost” strips!

We’ll go with the original Ribtickler 2 (1946) for analysis here (although the cover was basically identical each time it was re-used). The cover has no direct connection with any of the interior content, which is mostly funny-animal humour strips (no mice or giant caterpillars, though). If the cover of The Skipper was “surreal,” what would we call this? A human photographer (vaguely Jerry Lewis-like, although this was well before Jerry Lewis started his career in earnest) says “Just for the fun of it!” and pretends to take a photograph of Minnie Mouse and her cat (possibly Figaro, although he doesn’t look like it--the concept of a mouse having a pet cat is mind-blowing enough, but that’s Disney for you), but a giant, laughing, bow-tie wearing caterpillar erupts from the lens instead!

You might say, “Minnie Mouse, that’s a bit of a stretch, innit?” Oh, I don’t know, take a look at this image from the main title of “The Barnyard Broadcast,” a 1931 Mickey Mouse cartoon. The “real” Minnie Mouse and Ribtickler Minnie are both black mice wearing high heeled shoes, a polka-dotted skirt with exposed bloomers, and a modified stovepipe hat (although real Minnie’s hat sports a flower while Ribtickler Minnie opts for a feather). Sure, Ribtickler Minnie is wearing a blue blouse while real Minnie is topless (she apparently didn’t cover up until the Sixties), but it wasn’t Fox’s fault that Disney’s Minnie was shamelessly parading herself around for 3 decades.

One commenter on comicbookplus.com suggests the giant caterpillar was inspired by “Mr. Mind,” a super-intelligent alien worm who was one of Captain Marvel’s arch enemies in this era. There are points of similarity: both can talk, both have mostly green, segmented bodies, have antennae sticking out of their heads, and both have something around their neck (Mr. Mind has a radio-shaped “talk box,” while Ribtickler Caterpillar has a purple bow tie). The biggest difference is their relative size: Mr. Mind was two inches long; Ribtickler Caterpillar is closer to Monster That Challenged the World size.

The burning question is, however: does this cover seem funny? Or, more relevant, does it encourage someone (presumably an adolescent boy or girl) to buy the comic book? The comic is called Ribtickler after all, strongly implying humour, and yet this cover is horrific, bizarre, even nightmare-inducing. The giant caterpillar is laughing (“Ha! Ha! Ha!”) but Minnie and her cat are plainly terrified, not just startled.

I don’t know, this cover just doesn’t seem that appealing to me. Not that the contents of the comic book are great--not by a long shot--but they’re not as brain-numbing as the cover image and all that it implies. But what do I know? There aren’t too many comic book covers that were used three times over the space of 13 years, so apparently somebody thought it was…good enough.

0 notes

Photo

One-Way Ticket to Hell: Teen-Age Madness!

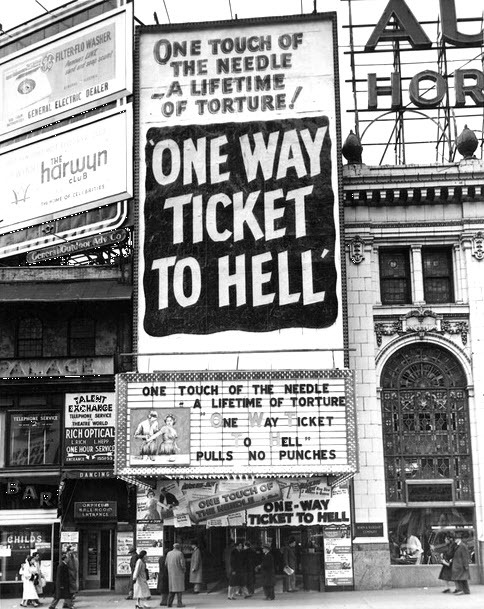

Although this series of essays concentrates on the analysis of print materials, we’ve bent the rules slightly this time to present a two-fer: a one-sheet poster and a theatre marquee display for One-Way Ticket to Hell (1955).

One-Way Ticket to Hell (better-known today as Teenage Devil Dolls, the video release title) was originally titled One Way Ticket. The film was produced, directed, and written by Bamlett “Bam” Lawrence Price Jr. (who also plays the main villain), a film student at UCLA (and married to actress Anne Francis from 1952-55). Picked up for theatrical release by Eden Distributing, it was sold as an exploitation film, although it is actually rather serious in tone. Like some other notorious future “cult classics” (such as The Creeping Terror), One-Way Ticket to Hell features no “name” actors and has no sync dialogue.

An extensive collection of One-Way Ticket to Hell “paper” can be found here, including a one-sheet (27x41 inches) poster, a 40x60 poster, a lobby card set and a still set. We’ll examine the one-sheet poster, as well as the marquee display for the film’s December 1955 exhibition at the Globe Theatre in New York City.

The one-sheet poster is colourful, lurid and well-crafted. The overall “look”--including the printing--seems a bit old-fashioned for 1955. Posters for mainstream releases in this era tended to be much brighter, even for movies in the exploitation/crime genre.

The text elements--the tagline and two text boxes--are common to both the one-sheet and the 40x60, although the larger poster reduces the number of separate images from 5 to 2. The “reclining woman in green” art appears in the same, lower position in both posters, but the upper sections are very different.

The 40x60 has a single key illustration of a man injecting a woman with drugs as another woman looks on, while the one-sheet gives us 4 different images from the film, as well as two newspaper headline mock-ups. This makes the one-sheet a little “busier” that the 40x60, but it also provides the potential ticket-buyer additional information about the film’s contents.

Interestingly enough, while both posters depict a woman getting a drug injection from a man, the images are different, featuring the same, presumably evil, man but a different woman. This “key art” ties directly to the film’s tagline: “One Touch of the Needle--A Lifetime of Torture!”

[As an aside, the lobby cards may have been produced for a different release, since they carry the “Bamlet L. Price Jr. presents” credit (the posters have no company name). The lobbies do feature a line-drawing version of the “reclining woman” art and the secondary tag-line “The Story of Teen-Age Madness,” however, both of which link them to the poster versions.]

Thanks to the aforementioned website containing the lobby card set and still set for One-Way Ticket to Hell, the photographic “inspiration” for the individual images on the one-sheet poster can be identified. Woman getting injection? Yes. Man picking up unconscious woman? Yes. Woman tries to prevent a sinister-looking guy from choking another woman? Yes. People on motorcycles? Well, this image isn’t on the extant lobbies or stills, but it’s in the movie so the poster artist probably got a photo for reference. In fact, there’s a chance that a fair amount of the artwork was pasted-up from the photographs themselves and then retouched and colourised. No shame in that.