Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

David Drummond &

Dhurrumtollah Academy Backdrop At the time when Anglican education was being introduced in Bengali society in late eighteenth century, many belonging to the Hindu community had compromised their religious beliefs and practices. On the other hand, quite a few erudite Englishmen and Europeans, who took to teaching in Bengal, lacked adherence to their religious orders. David Hare was an atheist, a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Home of the National Theatre

Immortalized in Thomas Daniell’s Gentoo Buildings Gentoo Buildings: Calcutta from the River Hoogly; Plate 8. By Thomas Daniell, Aquatint, ink and watercolour on paper. 1886. Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of Art. Overview This paper aims to establish Thomas Daniell’s aquatint ‘Gentoo Buildings’ created around 1787 as the pleasure house of Russick Krishna Neogy on the river Ghat…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

NATIONAL THEATRE, Calcutta: Myths & Realities

The home of the National Theatre Society on the first floor of the magnificent pleasure house, Bardwari Baithakkhana, Babu Rashik Neogi built on the River Ganges. The image of the run-down 2-storied building may be seen in the famous oil on canvas, Ghentu Residents on Hooghly River that Thomas Daniell had painted in 1788. Courtesy British Library. THE STORY The National Theatre, Calcutta was…

0 notes

Text

VANISHING ENGLISH THEATRE & the Emerging Bengali Stage in Renaissant Calcutta

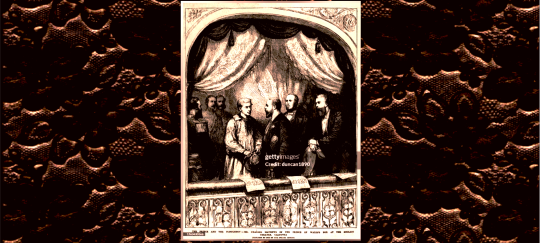

Prince of Wales’s Box at the English Theatre. Calcutta. 1875. Courtesy Getty’s Backdrop British ex-pats built ‘Town Calcutta’ replicating London to continue to live in an exclusive English style, shutting out the natives of the land. It may appear a hard saying, yet the fact remains that, even for the natives, Calcutta was an artificial place of residence [Firminger]. The Britishers were…

View On WordPress

#Amateur Dramatic Society#Augustus Hicky#Baishnav Charan Auddy#barnaby brittle#bengali stage#Bishop Carew#Bishop’s House#british culture#C.H. Tawney#calcutta theatre#Captain Richardson#Charles Mathews#Charles Metcalf Plowden#chowringhee theatre#college of St. John#David Lester Richardson#democratic theatre#derozians#Dramatic and Burlesque and Ballet Company#Dramatic Performances Act#Dumdum Garrison Theatre#Dwarkanath Tagore#East India Company#Emily Eden#emma robert#english theatre#esther leach#George Chinnery#George Lewis#George Williamson

1 note

·

View note

Link

Check out this awesome 'Buon Natale' design on @TeePublic!

0 notes

Text

CHOWRINGHEE THEATRE & ITS ALTER EGO MRS ESTHER LEACH

CHOWRINGHEE THEATRE & ITS ALTER EGO MRS ESTHER LEACH

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Playhouses of Town Calcutta

The Playhouses of Town Calcutta

The Old Fort, Playhouse, and Holwell’s Monument. 1786 Thomas Daniell. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum CALCUTTA THEATRE After a lull of two decades since the Play House had closed, Calcutta’s second playhouse, Calcutta Theatre, opened ceremoniously in 1776, if not a bit earlier. Preliminaries Unlike the first ‘Play House’, the Calcutta Theatre, often called ‘Second Playhouse’, has left us plenty…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

The Last of the English Theatres in Colonial Calcutta:

The Last of the English Theatres in Colonial Calcutta:

THEATRE ROYAL This is where Lewis’s Theatre Royal stood at 16 Chowringhee next to today’s Grand Hotel Backdrop After a warm farewell at Lyceum Theatre on 31 March 1870 night George Benjamin William Lewis and his wife Rose Edouin Lewis had left for Melbourne with no plan to revisit Calcutta any sooner for renewing the fame and commercial success they achieved during the last two and half a year…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

LEWIS'S ROYAL LYCEUM

LEWIS’S ROYAL LYCEUM

In the Making of Homegrown Professional Theatres and Theatricals of Calcutta View of Calcutta Maidan By Charles D’Oyly. Courtesy: BL. Lewis’ Royal Lyceum Theatre was situated near Ochterlony Monument. Backdrop When the English came to Calcutta they brought with them the plays of William Shakespeare. When Lewises arrived in 1864, English theatre made a century dating from Calcutta’s second…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

ANTOINE DE L'ETANG : THE OTHER CHIVALROUS ADVENTURIST

ANTOINE DE L’ETANG : THE OTHER CHIVALROUS ADVENTURIST

Details not available

BACKDROP

Antoine De L’Etang (1757-1840) is the other chivalrous adventurist, who was like Julius Soubise (1745-1798) [Puronokolkata], deported to India in the late eighteenth century for outrageous romancing. His last-name appears in many styles in literature, such as ‘de l’Etang’, ‘De L’Etang’ and ‘Deletang’ that he used in his books. About his early life…

View On WordPress

#adeline marie#ambroise#antoine de l’etang#barbier#bodyguard#book on stud#calcutta#chevalier#chevalier de l’etang#chinnai#colonel maxwell#de l’etang#dragoons#dupont de l’etang pierre#East India Company#eugene#floyd#garde de corps#grand equerry#grand-croix#guard du corps#hans axel von fersen#jeane barbier#julia adeline antoinette#julius soubise#lettre de cachet#louis xv#louis xvi#louis-auguste#m. vinditien guillain

0 notes

Text

I

PRELIMINARY WORDS Calcutta acquires its distinctive flavour presumably from the fusion of characters grown in diverse cultural environs in distant lands. Being the first capital of modern India, the city attracted overseas traders, bread-earners, fortune hunters and travelers who spent varying length of their lives here amid the locals giving exposure of spectacular living styles and standards to them. Many of those were great names who had left for us textual and visual details, others left too little to trace back their lives in those maiden days of Town Calcutta still wrapped in haze. Much of the important constructs gone amiss in want of contexts culled from firsthand records, or from the secondary sources left by contemporaries. Reconstruction of the period can possibly be done only by collaging syntactically the fragments likewise promising many a surprise.

This portrait of Julius Soubise(1746-1798) a self-styled ‘African Prince’, is believed to be the long-forgotten work of Johan Jaffony referred to in the Reminiscences of Henry Angelo.(1830). See Notes

It is, indeed, surprising to know how many shades of skin the early visitors of Calcutta had and in how many different tongues they spoke. But more amazing was the loaded experience of the colourful past they had lived before landed in India. They looked different, thought different and did things differently for living. Those were the people who opened up new sources of learning to live in different ways beautifully in a plural society of modern time. The 18th��century Calcutta with its formative society had welcomed the harbingers of change. Among them were two cavaliers of rare charms, both banished from their homelands apparently for guilt of chivalrous romancing. Julius Soubise the Caribbean boy groomed as a English dandy, and the French nobleman Antoine de l’Etang the personal bodyguard of Luis the XIV were contemporaries. Although l’Etang was 3 year senior by age, arrived later in 1796, while Soubise, nearly a decade before, in 1778.

II

JULIUS SOUBISE IN LONDON

Soubise may be said to have been born twice, the first time in London, next time in Calcutta. His two lives were opposite to each other but inseparable like day and night. This is why you must allow me to dwell upon his London life before narrating his life in Calcutta.

Catherine Hyde Douglas (1701-1777), Duchess of Queensberry, Painted by Jervas. 1720

Charles Douglas. 3rd Duke of Queensberry

CIS:E.2185-1949

Dominico Angelo, Italian fencer

Angelo’s Fencing School, Haymarket

Little we know of the Caribbean child, later grown to a notorious young dandy, a self-stylized ‘Black Prince’ in London high society, except that he was born around c.1754 in St. Kitts to a white planter father and a mother of African descent. The boy was sent under the guardianship of Captain Stair Douglas of Royal Navy to England. Reaching London on April 2nd 1764 he was given to the care of the captain’s cousin sister Kitty or Catherine Hyde Douglas, the Duchess of Queensberry (1701-1777) – an eccentric beauty and a socialite, known for her fondness for aprons. [Here is a portrait of her painted by Charles Jervas in the 1720s]

The Duchess apparently freed the boy from slavery and named him Julius Soubise, after Charles de Rohan, Prince of Soubise. [Miller] An all round education appropriate for the British genteel society was set out for him. The celebrated Italian master Angelo Dominic taught Soubise in gentle arts in his School of Arms. Soubise began to make his mark by 1772 – a decade before the rising popularity of amateur and competitive fencing matches cemented the sport’s position in the leisure economy of the fashionable world. He also became proficient at the violin and composed a few merry pieces in the Italian style, and even sang in a comic operatic manner. Soubise was a great favourite of David Garrick’s, the elder Sheridan gave him lessons on elocution, and was loved by some of the brightest luminaries of his time.

His rising success in such a young age inspired Soubise in modeling himself as the ‘Black Prince’ – an epitome of aristocratic masculinity – opened for him a reckless life of a ruthless womanizer and squanderer. He became a source of worries for the upper-class Britons because of not having any real contenders to stop Soubise demeaning the values and the image of the British nobility. As we find from the stray records fetched by recent scholars, the Duchess, alone had the key role in upbringing Soubise in baronial fashion. She maintained a house in town for Soubise, as well a liveried carriage to take him around, and all amenities for leading his foppish life. She herself suffered often from his heedless drives, but made no attempt to check him firmly, probably due to her kindly feelings toward the black boy less than half of her age. The vanguards of the high society in London thought that circulation of a scandalous cartoon involving Soubise and the Duchess should be a sure measure to stall Soubise by embarrassing him as well as his patron the Duchess, and his mentor Dominico Angelo all at once.

A satirical picture depicting Soubise and the Duchess of Queensbury engaged in a fencing match, an engraving of Austin brought about on May 1,1773

“Macaroni” was a contemporary name for a fashionable young man; “Mungo” was a name of an officious slave from the 1769 comic opera The Padlock

On May 1, 1773, they brought about a satirical picture depicting Soubise and the Duchess of Queensbury engaged in a fencing match, an engraving of Austin based on illustrations of fencing compiled by the Angelo fencing dynasty. Duchess Catherine and Angelo are thus implicated in the most disgraceful public attack on Soubise. As researchers think, it would be a mistake to read the cartoon’s use of fencing as merely allegorical, or to assume that the duchess is the cartoon’s only target. In fact, the cartoon also implicates Dominico Angelo. Besides William Austin’s engraving, there have been most notably, A Mungo Macaroni (published September 10, 1772), part of a famous 1771-73 satirical series of engravings depicting fashionable young men, published by Matthew and Mary Darly.

In some sense, Cohen pointed out, “the ultimate target of the cartoon is neither Soubise nor the Duchess of Queensberry, nor even Angelo, but the market economy in which the trappings of rank could be indiscriminately bought and sold.” [Cohen. 2018] The satire was of poor taste and offensive in nature. It must have dampened the spirit of Soubise at least temporarily, and the Duchess felt obliged to bring him back to his good senses to the possible extent. As it appears, Soubise used to stay at Angelo’s, yet remained a favourite of the Duchess who continued to take care of his fads and follies and pay off his large debts quietly. Things suddenly went out of her hand when the Duchess got informed that ‘one of her maids had been raped by Soubise’. She tried to dissuade the woman in vain from going to court. [Sandhu] It was probably from the Duchess, Angelo came to know of the kind of fast life Soubise had been leading in his private apartments where he assumed the habits of an extravagant man of fashion in company of succession of visitors in rooms decorated with roses, geranium, and expensive green-house plants. It was Angelo on whose recommendation, Soubise was sent to India at the expense of the Duchess. [Miller] The Duchess had hardly any option but to arrange passage for Soubise to flee the country he was so madly in love. It was the tragic end of her cherished relationship with the little black boy she brought up as a social rebel decrying against racialist, xenophobic and moralist sentiments in her own fashion. She died of eating too much cherries on June 17th 1777 [Fryer]. Next month Soubise sailed for Calcutta on July 15th 1777 [Sandhu] to start another life very different from the one vanished with the passing of his noble patroness.

III

SOUBISE IN CALCUTTA

On July 15, Julius Soubise left the English shore boarding the Bessborough East Indiaman under the captaincy of Alexander Montgomerie. The ship reached Madras via Media and Cape on 9 February 1778 [Three Decks]. In those days river trips from a South India port to Calcutta would take about three weeks. It could not be any earlier than March 1778 Soubise arrived at Calcutta’s Chandpal Ghat where large vessels used to embark. Almost a nameless black boy of twenty-three, Soubise landed in the small township of Calcutta leaving back his gorgeous past of princely life assuredly protected by the Duchess of Queensberry till her last. Soubise wanted her most to be at his side while starting a new life of a labouring common man instead.

Nabakissen’s Evening Party attended by Calcutta British and European families

Begum Johnstone, the grandmother of the Earl of Liverpool

Calcutta was then ‘the grave of thousands, but a mine of inexhaustible wealth’. [Long] Already the capital of British India, Calcutta was still then a small township resurrected from the ashes of Lalbagh Battle centering around the Customs House amid the ruins of the old Fort William. Clive Street was then ‘the grand theatre of business’, and there stood the Council House, and every public mart in it. The day Soubise landed, there was no Mint, no Calcutta Gazette, no Asiatic Society of Bengal, but a Court House to render legal services as well as facilities of balls and theatrical acts besides running of the charity school for which the building was funded by the Lottery Committee and Omichand a Rothschild of India. Calcutta had ‘a noble play-house—but no church’, service was held in a room next to the Black Hole. The St John Church – the first Anglican Cathedral of Calcutta was founded by Lord Hastings on the land donated by the Hindu Nabokissen in 1874. [Long] All these institutions nevertheless came up one after another in the presence of Soubise. There were, however, no dearth of amusement and recreation with theatrical houses, hotels and coffee shops for the white population, largely Englishmen, Eurasians, few Americans. The presence of native society in Tank Square vicinity was imperceptible, excepting a few men of affairs like Omichand and Nabokissen. Those days the influence of the fabled socialite, Begum Johnstone, the grandmother of the Earl of Liverpool, prevailed over the lifestyle of Calcutta’s citizenry. Till ten at night, their houses were lit up in their best style, and thrown open for the reception of visitors. There were music and dancing for the young, and cards for the old. Common people live both splendidly and pleasantly, the forenoons being dedicated to business, and after dinner [= midday meal] to rest, and in the evening to recreate themselves in chaises or palanquins in the fields, or to gardens, or by water in their budgeroes. [Blockmann] The condition of Calcutta was not too kind to the young men fresh from school, lavishing large sums on horse-racing, dinner parties, contracting large loans with Banians, who clung to them for life like leeches, and quartered their relations on them throughout their Indian career.

It was perhaps the most critical phase in Calcutta history that Soubise witnessed during the last two decades of the 18th century. This was the time when Calcutta extended itself far beyond its boundary limits to the jungle, covering one-third of the Company’s territories, inhabited only by wild beasts, and in Chowringhee, between Dhurrumtollah and Brijitalao, where the new colony of the Europeans was being stretched out. The changing scenario of the Town Calcutta growing into the City of Palace can be envisioned by looking into the earliest Calcutta maps charted by Aaron Upjohn and Mark Wood, and going over the innumerous paintings of world-class artists, like Thomas and William Daniells, Thomas Hickey, Tilly Kettle, William Hodges, John Zoffany, and others. Within a year after the momentous duel fought between Lord Hastings and Sir Francis on 17 August 1777, Soubise entered the Calcutta scene prospecting as an accomplished lancer, a musician, and a horseman.

IV

ENTREPRENEURIAL VENTURES Settlers of those days were hospitable. As we learn from an anonymous account of travels (1760—1768), “there was no part Hospitality of the world where people part with their money to assist each other so freely as the English in India.” [Anon. Edin. Mag.] We might have then some reasons to believe that Soubise had not been left all by himself totally incapacitated in his ventures, if not black-skinned.

Soubise took a couple of years to initiate the business plans he designed after his mentor Dominico Angelo’s model. It was from Angelo, Soubise equipped himself with the arts of aristocratic sportsmanship – horse-riding and fencing, and also some marketing skills as well. Before he formally inaugurated his Riding Academy on Thursday, November 7, 1780, Soubise had started teaching fencing. We understand from an insertion, most likely by Soubise himself published in Bengal Gazette of November 4, 1780, that next Thursday Mr. Soubise will open his Manège for the reception of the horses. His Fencing days will be shifted to Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. The next thing he did was staging Othello in the Theatre commemorating his first business venture in Calcutta. The Bengal Gazette declared sometime between 9th and 12th December that the Managers of the Theatre generously offered to give a benefit play to Mr. Soubise, toward the completion of his Manège. Mr. Soubise will appear on that night in the character of Othello. And afterward perform the part of Mungo in the entertainment ….. The part of Iago will be attempted by the Author of the Monitor, and Desdemona by Mr. H. a gentleman of doubtful Gender. [Bengal Gazette, Dec. 9th-12th 1780] Here, the reference to Mr. H. seems to be to Hickey himself, the editor of Bengal Gazette, who was known as an eccentric Irishman. Hickey’s acting or posing as a person of neutral sex may have been one of his eccentricities as Cohen maintains but it was perfectly in tune with the contemporary practices followed in the British stage in London as well as in Calcutta she pointed out. [Cohen. 2018].

Four years after, in 1784, Soubise set up his Fencing School advantageously housed behind Harmonic, the famous tavern of 18th century Calcutta, stood opposite the Lall Bazaar Police Court. As announced in the Calcutta Gazette on Thursday, June 24, 1784, Soubise proposes to teach the art of fencing against a nominal fees of two Gold Mohurs for the entry and two Gold Mohurs for tuition per month. His days are Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Such Gentlemen as choose to take private lessons at their own house’s, will be attended on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays; in which case his terms are three Gold Mohurs entrance, and three Gold Mohurs per mouth. [Seton-Karr]

Soubise was preparing for his new riding school since early 1788. Fort William reportedly granted him permission to run the school vide Calcutta Gazette April 24, 1788. The most enthralling publicity feat Soubise brought about for his new venture was an event report he made to appear in the Calcutta Chronicle of December 11, 1788. The report clearly reflects the way his businesses were packaged for a defined clientele belonging to Calcutta society as Domino used to do it in London. The report went as follows:

“Yesterday morning, early, the manly exercise of horsemanship was practiced at the Manège, by the scholars of Mr. Soubise, before a very numerous assembly. After the practice was over, near two hundred of the principal people of the settlement sat down to an elegant breakfast provided on the occasion. Breakfast being over, a ball was given, and the ladies and gentlemen were so highly delighted, that it was not without evident signs of regret, they relinquished such a pleasing and health-giving source of amusement …” [Calcutta Chronicle of December 11, 1788] Soubise in his manège taught “more than just horsemanship: it offered education in – as well as the opportunity to take part in a simulative performance of – English gentility”.[Cohen. 2020] Notwithstanding his best motive and organizational capability time and again he failed to take off.

“The newspapers that document these years are a chronicle of his financial instability. Soubise placed advertisements to publicize his new ventures – fencing lessons, horse riding lessons, sales of the mare. Those were followed at regular intervals by notices of insolvency. Yet, whether imprisoned for debt, hounded by creditors, or suffered the sale of his stables at auction, Soubise inevitably bounced back with new ventures”. [Cohen, 2020]

So far we have seen him in Calcutta, Soubise was a master performer and zealous teacher – a man of extraordinary talent in public entertainment with full of ideas for publicity and promotion, yet success eluded him in Calcutta. Soubise lost every business opportunity he created but never let go his indomitable spirit to start anew over and over again. His social and personal life too was rarely without unwelcome events. We come to know from Calcutta Gazette of 26 March 1789 that Soubise survived a brush with death when a French neighbour took a razor to his throat. He bore a ‘large Scar on the left side of the Throat’ from this encounter until his death.

Portrait of Nathaniel Middleton.by Tilly Kettle c.1784.

Lucknow After recovery, Soubise disappeared from Calcutta scene for three years while he stayed in Lucknow. One of his attractions was the famed stable of Nawab of Awadh . Soubise got acquainted with many distinguished people. It was told that a gentleman who held a high station in the east, known by the appellation of Memory Middleton, became a friend and patron of Soubise at Lucknow. [Angelo ] The gentleman could have been none other than Nathaniel Middleton a closed associate of Warren Hastings who sent him at the court of Nawab as the Resident. Middleton got involved in the lengthy dispute between Hastings and his Bengal Council, which eventually led to Hastings’ impeachment. However, since Middleton had resigned from the East India Company in 1784 and went back to England much before Soubise arrived at Lucknow, no meeting ever taken place between the two contrary to the general belief. [Stonopedia] Before Soubise left Lucknow at the end of 1791, he had developed some good connections with high officials of the Stables of the Awadhi court, some of the largest and best on the Indian subcontinent, which he exploited later. Calcutta meanwhile prepared to move south with completion of the Esplanade ground after getting the Dhurrumtollah Tank constructed. He took quite some time to resettle.

V

PRIVATE LIFE VS SOCIAL ISSUES This was the time when Soubise met Miss Catherine Pawson, a pretty and progressive young lady, popularly known as Kate. She was the only daughter of William Pawson, a good friend of Richard Blechynden (1759-1822), who became a soar critic and an reluctant business patron of Soubise.

Eduardo Territa, Active by James Gillrayi(Activen 1792

Richard Blechynden. Courtesy: Gerald Johnson Fox

Blechynden arrived in Calcutta in 1786 at the age of 22 years, and since then worked in various capacity – as a civil engineer, architect, or building contractor on his own, and sometimes worked under the Superintendent of Streets and Buildings – an Italian architect called Eduardo Tiretta of the Tiretta Bazaar fame. Blechynden also had a share in the Chronicle newspaper. Although he lived in rented houses in town, Blechynden spent his leisure time hunting in the manner of an English squire in “Belle Couchée” – a grand garden house with stables he owned at North-East Calcutta, off Dum Dum (later ‘Belgatchya’) road, about an hour’s walk from Tank Square. By 1806, after renovations, it turned into a very large, lower-roomed house with plenty of grounds and a tank of excellent water. It looks like, this had been the original premises of the legendary Belgachia Garden House and Blechynden its first owner before the property was sold to Lord Auckland and then passed on to Dwarkanath Tagore.

Rammohun Roy 1772-1833

Dwarkanath Tagore 1794-1847

In spite of his multiple income sources, Blechynden was not always financially steady, particularly in those days of French War, neither was his friend William Pawson. On coming to India, Pawson, son of a London wine merchant, joined the East India Company in 1765 and held the position of Paymaster General [Busteed]. He was dismissed in 1781 on the abolition of Provincial Councils. Depending on a small allowance he was permitted to draw, Pawson lead a humble life with his daughter. Although Blechynden, Pawson, and many like them, struggled with debts in 1790s, they nonetheless considered themselves genteel. Catharine Pawson, a member of the ‘polite society’ like her father, never cared much for social sanctions and taboos. “Upon making her acquaintance in 1793, Blechynden ‘thought she was very forward for a young lady’. A newspaper poem published by one of her admirers gives a similar impression, as does her penchant for acting, an activity considered out of bounds for gentlewomen.” Blechynden believed “her attitude undermined her class identity and social standing.” He might have felt something more than that – that it was not she alone but her family and friends too were at risk. The fear and anxiety of social rejection disturbed Blechynden’s peace of mind. His debts, his inability to pay salary to his staff, his gradual loss of hearing – were some of his moral and physical failings that made him apprehensive of social repercussion. The latest however was the shock he received from his friend’s freakish daughter and her scandalous affair with Soubise the ‘Coffree’ boy of a questionable character. Later, when Blechynden heard about their engagement, he could hardly conceal his indignation from the bride’s father, ‘I had heard, but scarcely knew how to believe it’. Pawson had no answer for him but openly speculated as much, that ‘he supposed the Coffree screwed her up tight — and that was the reason she preferred him’. [Cohen. 2020]

It was not interracial marriage as such that vexed Blenchynden’s mind. As Cohen pointed out, ”especially among men of Blechynden’s milieu, who tended to establish long-term relationships with Indian ‘bibis, albeit often outside the legal institution of marriage.’ In fact, between 1792 and 1809, Blechynden fathered two sons and six illegitimate children by four mothers – two Indian Muslim, one Indian or Eurasian, and one India-born Eurasian bibi.

Blechynden acted like a responsible father by providing the children with English education and did nothing exceptional against the norms of the then Calcutta society. Two noblemen of his time, Major General Claude Martin and the business tycoon William Palmer had their children by native mothers socially recognized as their wives unlike all others. [Puronokolkata] Of course, in the case of Soubise’s marriage the racialization of gender was contrary to the conventional model. White men marrying black women were not unheard of in Job Charnock’s settlement, as he himself took a deshi wife, and many followed him thereafter. But the interracial marriage in opposite direction, that is, white-women marrying black-men most probably did not take place in colonial India ever before, although hundreds of Indian Lascars of British ships espoused English wives in England for more than two centuries.

Major William Palmer with his second wife, the Mughal princess Bibi Faiz Bakhsh by Johann Zoffany, 1785.

It was hardly possible for Blechynden to judge Soubise by common social parameters as they belonged to different layers of the English society at two different cultural setups, one in London, the other in Calcutta. In London, Soubise ‘was taken up by fashionable society, became a fop among fops, used expensive scent, went around in a liveried carriage, a favourite of Garrick, brushed shoulders with some of the brightest luminaries of his time. He was Britain’s first Black Dandy, and a virtual socialite.[Fryer] Whereas, “the Calcutta social milieu Soubise entered after his marriage was a world away from such exalted circles.” [Cohen. 2020] What bothered Blechynden was the class identity and social standing rather than ethnicity issues. Catherine’s wedding, he feared, should undermine the very ground on which Catherine stood with her people socially connected. It was more so because the black man here was none but Julius Soubise, an African by birth, overly proud of his own black figure reminding an Othello. Blechynden, with his racist mind-set could not stand the air of self-importance and arrogance of Soubise. Blechynden hoped, Soubise being a chronic debtor and all-around rogue, could hardly promise to make an ideal husband. But he was all wrong and he came to realize that in later days and admitted it with a shade of repentance when Soubise was no more. It was Blechynden who investigated if Soubise did actually married Catharine and found that they did marry but in Portuguese Church by Padre Geovan showing their limited positioning in polite society.

Belying her father’s friend Blechynden’s forebodings, Catherine wedded Soubise and remained devotedly in love with him. She never ever left side of Soubise while passing through a series of challenges up to the end of his tormented life, physically decrepit and financially bankrupt. Soubise, even in his worst time never stopped admiring his wife’s beauty. We see him saying to his guests at dinner “I declare my wife grows handsomer every day”, and sportively to his wife, ‘I wish I had a couple of you!”.

VI

It looks like Soubise with his family had been staying around Lall Bazar-Cossitollah area for more than a decade until he moved into Dhurrumtollah neighborhood. His new establishment, Calcutta Repository was ready by early 1795. The Calcutta Gazette published on February 19th, 1795 an elaborate description with a complete business profile of the Calcutta Repository, including its services, facilities, locale and t&c. Very likely, the news report was penned and sponsored by Soubise himself.

CALCUTTA REPOSITORY “Mr. Soubise having observed that the disagreeable and ill-contrived stables in which many gentlemen’s horses stand in Calcutta, and even in home that are more convenient, the smell, noise, and mosquitoes they occasion, has long had a wish to erect a set(?) of spacious, airy, and convenient stables, upon a plan of his own, for the accommodation of the Settlement; and having at length, by the patronage of some of his friends, been enabled to carry it into execution, he tenders his Calcutta Repository to his friends, his subscribers, and the public in general. As every convenience that could possibly be devised has been adopted to render them complete, he flatters himself they are, without exception, the best stables of any in India; and as Mr. Soubise’s professional knowledge and long residence in the country enable him to pay every requisite attention to that noble animal, the horse, he hopes to obtain a share of that liberal patronage which has so often distinguished this Settlement. The Repository, which in now open for the reception of horses, is situated to the north of, and nearly behind Sherburne’s Bazar [where Chandni Market now located], leading from the Cossitollah down Emambarry Lane, and from the Dhurumtollah by the lane to the west of Sherburnc’s Bazar.

With a view to the further convenience of the Settlement, Mr. Soubise has erected one [range?] of stables, nine feet wide, for the accommodation of breeding mares, or horse who have colts at their side. There are likewise carriage houses, with gates, locks and keys to each, which render them very complete. The terms of the Repository are made as reasonable as possible and are twenty-three Sicca Rupees per month, in which is included every expense (medicines excepted) for standing, syce, grass-cutter, feeding, and shoeing, and for standing at Livery only at five Rupees per stall. Further particulars may be known on application to Mr. Soubise at his dwelling house, near the Repository, or at the menage.”

The Repository was the last major effort Soubise made with Mr. Pawson as his partner. Pawson invested a good amount of money he borrowed from Blechynden but had no luck to pay him back. This project failed as every other one did. Returned from Lucknow, the idea of trading horses came naturally to a clever horseman like Soubise, who knew all about horses. The first horse race of India was held at Akra on January 16, 1794, where Soubise must have been present to enjoy the inspiring mounted sports and became alive to a potentially big market of horses in Calcutta. Besides, the growing demands of war horses after Plassey, and carriage horses with the road expansions there always a niche market for the horse as a luxury commodity. Being in India for nearly a decade Soubise had enough exposure to realize that the horse trade was a risky game, but for an over-confident man like Soubise the first concern was the money to fuel his business, and that too not so much a problem for him being a shrewd negotiator in credit manipulation – so long the project was profitable enough. But as we know, luck seldom favoured Soubise. Out of the amount of Rs. 5000/- Pawson borrowed from Blechynden, Soubise lost Rs 3500 on the horses of Awadh stables that Saadat Ali Khan sent him in August 1796. In the same month, Soubise was imprisoned ‘for shortchanging a customer on the sale of a horse in another complicated credit transaction.’ Pawson’s stables were later sold by lottery and the lotto winner made an offer to Blechynden but he was not ready with the money. Ultimately the stables went to De l’Etang who completed the deal by December 1797.

VII

FINAL YEARS

Blechynden noted in his diary that the final three years of Soubise’s life were a downward spiral. The stabling proved unprofitable and by 1795. Soubise was already looking out for new revenue streams. Blechynden noticed with dismay, Pawson was in a mood to seriously consider Soubise’ latest fad for setting up an Auction House at the ‘old Harmonic’ – the grand tavern equipped with spacious accommodation once used for holding large parties, and ball. Blechynden was perturbed: ‘how then could Soubise prosper without money—without interest—without friends — and without a particle of public confidence’? He sounded genuinely worried. But didn’t Soubise dare to take such a challenge many a time since he landed in Calcutta? A failure could not deter him ever to take another stake in another sphere of business. Besides running horse-riding and fencing schools, and livery stables, Soubise worked for the East India Company conducting breaking-in of military horses. As suggested in an unverified source, Soubise might have also tried out an unfamiliar field like keeping a bookshop in Calcutta – the only shop of its kind owned by a man of African origin.

Before launching his Auction House Soubise planned for establishing a ‘temporary’ Riding House. Why did he call it ‘temporary’ we are not sure. Perhaps that he wanted to generate a quick money to meet some pressing expenses or meant this experimental in scope.What we know for certain is that his plan was inspired by his recent rapport with Nilmoni Halder, a resourceful Bengali businessman of Bowbazar. He came forward from outside Soubise’s circle, to support him with money and encouragement. The Calcutta Gazette advertised Riding House on July 5, 1798 inviting public attention to its sessions. We had no idea, however, how it all went off, but his other plan, a promotional theatrical evening at Calcutta Theatre was performed successfully on March 7, 1798 where ‘Kate’ (nickname of Mrs. Catherine Soubise) was reportedly ‘played with great applause’ [Busteed ?] Next Monday, on the 12th, the Calcutta Theatre presented the Comedy of of the Chapter of Accidents by Miss Lee was staged for the benefit of Mrs Soubise.

There was no indication that Soubise himself took any part in that evening; perhaps he did not. Soubise, a stage-artist groomed by Garrick, an elocutionist tutored by the elder Sheridan, a gifted violinist and singer, was surely expected on stage playing a stunning show befitting to the occasion. The sole reason for his remaining behind the screen might have been his suffering from intense rheumatism he was suffering from last few years.

The Riding House, that started on July 5, made way to the sudden accidental fall of Soubise from a devilish Arabian stallion on August 24. Blechynden found him in the Gallery laying on a mat, perspiring profusely — his head was slightly cut behind — but his Skull did not feel fractured. Blechynden saw blood oozing out of his right ear, and immediately sensed the blow was not only very dangerous but most probably mortal. Pawson and Mrs. Soubise went to the Hospital and remained with him till he died the next day from hemorrhaging in his brain. The death of Julius Soubise was reported in the Calcutta Gazette on 25th August 1798, and entered in the Asiatic Annual Register, vol.1 1798-99.

Within a week, Calcutta Gazette on August 30, 1798 reported the ‘Sale of Horses by Public Auction’ to be held every Wednesday at 10 o‘Clock in the forenoon. It was the beautiful Arabian saddle ‘Noisy’ – a property of Joseph Thomas Brown – to be on auction sale for the benefit of Mrs Soubise. The auctioneer Mr. A. L’Etang was the nobleman who alongside Mr. Blechynden rushed to see Soubise at the site of the accident. We will find him again in closer perspective in the forthcoming episode of magnificent horsemen.

Soubise’s death turned Blechynden, his worst critic in Calcutta, into a compassionate ally, appreciative of his talents and aggrieved at his tragic end. Blechynden did not press his friend Pawson or Mrs Soubise to repay his loan but could not save them from financial distress. Mrs Soubise with her father and children moved in a barrack, possibly one of the Bow Barrack quarters. Mr. Pawson passed away in 1802 leaving his daughter Catherine alone with her children William and Mary. We know nothing for sure about Catherine and her daughter Mary (baptized on 20 June 1785). William Soubise, an assistant in the Sudder Dewanhy Adawlat, married Flora Ward in 1819, and Maria was born to them on April 25, 1821, and Henry in 1824 (died in his teens). In 1839, Maria was married to James Bernadotte Vallente. William Soubise died on July 9, 1841 at the age of 43 at Calcutta.

VIII

END NOTES

If high fashion and luxurious life of love with a fair lady is an offence for a black gentleman then Michael Madhusudan Dutta, the Bengal’s celebrity poet of the next century Calcutta, was no lesser offender. The British-African Soubise was driven out of country by the racists and got blackballed by their counterpart British-India society in Calcutta, otherwise laudable for their camaraderie and supportive spirit. Madhusudan flared, as he had a friend like Vidyasagar to help the pauper to live princely regardless of social decry and hostility that had strangled Soubise to death.

Michael Madhusudan Dutta, 1824-1873

Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar, 1820-1891

It is interesting to note that both of his contemporary authors believed that the accidental death of Soubise was particularly tragic because of two separate reasons. Angelo writes “departed from his former thoughtless habits, his talents and address had placed him in the way to fortune.”[Angelo] Blechynden seemingly believed that having had Nilmoni Halder as a dependable impartial partner “a career was at length opened to him of getting out of his difficulties, in short, we can better spare a better man.” [Blechynden] This was the first time Soubise had a chance to overcome the racist resistance since he was ousted from the British society and exiled to colonial India inflicted with politically influenced racial hatred. In an environment of mistrust, Soubise had little opportunity to secure business credit on fair terms. Often he had to take deceptive means and ended up in jail; or prayed and rejected, for an instance, Soubise requested Blechynden to be one of his securities to the Asiatic Society for Rs 5000. Blechynden lied and declined politely.

Soubise did not leave anything in writing for us, except a specimen of his stylish love letters. There have been luckily two important documents of his contemporary writers: Henry Angelo the memoirist, and Richard Blechynden the diarist, providing significant events of Soubise’s life, and some scholarly works of recent writers that critically reviewed and analyzed those facts to portray Soubise meaningfully in modern contexts. In my modest attempt to restate Soubise’s life in the ethnocentric settings of the last score of the 18th century Calcutta, I remain indebted to Ashley Cohen and Peter Robb in particular for using their in-depth studies extensively.

NOTES This portrait of Julius Soubise(1746-1798) an Afro-British self-styled ‘African Prince’, is believed to be the long-forgotten work of Johan Jaffony referred to in the Reminiscences of Henry Angelo (1830). Until now, the pastel painting has been identified and re-identified with some nameless black servant or an ‘African prince’ attributed to John Russell, or toOzius Humphry.

Joffany painted Soubise’s portrait either in London before 1777 when Soubise left for Calcutta or in Calcutta between 1773-1789 when Zoffany visited India to paint number of masterpieces like Mordaunt’s Cock Fight (1784–86) Last Supper (1787) and significant portraits of dignitaries like Warran Hastings, Asaf-ud-Daula. Courtesy: Tate gallery.

See more: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/humphry-baron-nagells-running-footman-t13796

REFERENCE Ajantrik. 2017. “Fort-City Calcutta, A Faded Legacy.” Puronokolkata.Com. 2017. https://puronokolkata.com/2017/08/15/fort-city-calcutta-a-faded-legacy/.

Angelo, Henry. 1830. Reminiscences of Henry Angelo; with Memoirs of His Late Father and Friends .. Oxford University. Vol. 1. London: Colburn and Bentley. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=xsK6QCfrXPQC&hl=en.

Anonymous. 2004. “Middleton Nathaniel.” Sotonopedia. 2004. http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:middleton-nathaniel.

Blechynden, Richard. 2011. Sentiment and Self: Richard Blechynden’s Calcutta Diaries, 1791–1822. Edited by Peter Robb. New Delhi: Oxford U P. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=9PQtDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Blochmann, Henry. 1868. Calcutta during Last Century: A Lecture. Calcutta: Thomas Smith. https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Calcutta_During_Last_Century.html?id=1iIUvwEACAAJ&redir_esc=y.

Busteed, Henry Elmsley. 1908. Echoes from Old Calcutta; Being Chiefly Reminiscences of the Days of Warren Hastings, Francis and Impey. London: Thacker. https://archive.org/details/echoesfromoldcal00bustuoft.

Cohen, Ashley. 2018. “Fencing and the Market in Aristocratic Masculinity.” In Sporting Cultures, 1650-1850., edited by Alexis Tadie Daniel O Quinn. Toronto: Toronto University. https://books.google.com.au/books?redir_esc=y&id=xoBSDwAAQBAJ&q=soubise#v=snippet&q=soubise&f=false.

Cohen, Ashley. 2020. “Julious Soubise in India.” In Britain’s Black Past, edited by Gretchen H Gerzinz. Liverpool: Liverpool U.P. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ojfWDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA215&lpg=PA215&dq=julius+soubise+britain%27s+black+past&source=bl&ots=If5xkJmj-y&sig=ACfU3U3_7EEHLEjLsSShYgWW59kbgjMFcg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjU3MD0mrPoAhXzwTgGHfayC6cQ6AEwBnoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=julius.

Dahiya, Hema. 2013. Shakespeare Studies in Colonial Bengal: The Early Phase. New Castle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=hiBJDAAAQBAJ&pg=PP4&lpg=PP4&dq=Dahiya,+Hema.+(2013).+Shakespeare+studies+in+Colonial+Bengal:+the+early+phase.+New+Castle+upon+Tyne:+Cambridge+Scholars.&source=bl&ots=nSfRNhXIup&sig=ACfU3U2r7ne30FqWFwdLv1GM8IA-mFJVdQ&hl.

Fryer, Peter. 1984. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London: Pluto. https://books.google.com.au/books?redir_esc=y&id=J8rVeu2go8IC&q=soubise#v=snippet&q=soubise&f=false.

Long, Rev. James. 1859. “Calcutta in the Olden Time – Its Localities : Map of Calcutta, 1792-3.” Calcutta Review 36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(73)90259-7.

Miller, Monica. 2009. Slaves and Fashion: Black Dynamism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. London: Duke U.P. https://books.google.com.au/books?redir_esc=y&id=Bh4I_r6qV_8C&q=soubise#v=snippet&q=soubise&f=false.

Spencer, Elizabeth. 2015. “The Female Phaeton: Catherine Douglas, the Duchess Who Set the World on Fire.” In Difficutwomenconference May 1, 2015. https://difficultwomenconference.wordpress.com/2015/05/01/the-female-phaeton-catherine-douglas-the-duchess-who-set-the-world-on-fire/.

Sukhdev, Sandhu. 2003. London Calling: How Black and Asian Writers Imagined a City. London: Harper. https://www.harpercollins.com.au/9780006532149/london-calling-how-black-and-asian-writers-imagined-a-city/.

JULIUS SOUBISE: A MAGNIFICENT HORSEMAN IN 18TH CENTURY CALCUTTA

I PRELIMINARY WORDS Calcutta acquires its distinctive flavour presumably from the fusion of characters grown in diverse cultural environs in distant lands.

JULIUS SOUBISE: A MAGNIFICENT HORSEMAN IN 18TH CENTURY CALCUTTA I PRELIMINARY WORDS Calcutta acquires its distinctive flavour presumably from the fusion of characters grown in diverse cultural environs in distant lands.

#alexander montgomerie#angelo dominic#aristocratic masculinity#Asiatic Society of Bengal#begum johnstone#belgachia garden house#Belgachia Villa#belle couchée#bengal gazette#bessborough east indiaman#black dandy#black prince#bookshop#bow barrack#british nobility#calcutta chronicle of december#calcutta gazette#calcutta repository#calcutta theatre#captain stair douglas#catherine hyde douglas#catherine pawson#charles de rohan#clive street#comedy of of the chapter of accidents#Cossitollah#court house#customs house#david garrick#de l’etang auction house

0 notes

Text

A pair of racehorces. By Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya (1830-1850). Courtesy: Christie

PRELUDE Not until the British revamped army to recapture Calcutta in 1757, horses in India had the leading role in wars, and in everyday public and private life as well. Gradually the other two robust animals, camels and elephants, were being withdrawn from military and public services. The demands for suitable horses grew manifolds, and so was the prospect of horsetrading in India that attracted horse dealers from around the world to come and stay in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta engaging themselves in all kinds of horse-related enterprises, including horse auctions, livary stable services, saddlery, fodder supply, coach building, veterinary services, equestrian schools.

HORSE IN INDIA

India had an indigenous supply of excellent elephants, but not many good horses. Yet the horse of ‘Ashwamedha’ fame served as a symbol of power and glory in Indian tradition. There are evidences of horse riding in the era of Rikveda. [Coomaraswamy] The earliest known work on veterinary science India’s Shalihotra-sanghita, proves how seriously the fitness of horses was taken care of. Even so, India had to depend much on imported war horses since the indigenous horses were found inadequate for battlefront and their high war mortality rate. The good horses were imported to the Mughal state from Arabia, Iran, Turan, Turkey,Turkestan, Badakhshan, Shirwan, Qirghiz, Tibbet, Kashmir and other countries. Kabul and Qandhar were the major entrepots on the land-routes for the horse traders. While horses from Central Asia came to India by the overland route, Persian and Arabian horses were largely brought by the sea. [Khan] The ports of Surat, Cambay, Kutch, Thatta, Lahori Bandar and Sonargoan in Bengal were the major entrepots for the bahri horses brought for breeding. In order to establish control over the horse trade, the Mughal Emperors established friendly and diplomatic relations with the neighbouring countries. [Choudhary]

COUNTRY-BREEDS The Indian Country-bred, generally plain heads, long necks, narrow chests, strong hooves and low-set tails, archaically known as tattoo, vary from good-quality riding horses to small and poorly-conformed animals used for pack and draught work. They derive from many diverse horse breeds and types, including the small horses of the Himalayas of northern India, and the strong horses of the Punjab. Outside influences include Arab horses imported to Bombay and Veraval from the Persian Gulf, and the Australian Walers imported in very large numbers in the nineteenth century to Calcutta via Madras. The Indian Half-bred is a cross-breed between Thoroughbred stallions and local and imported mares of various types, raised mainly by the Indian Army as a cavalry mount. Apart from the regulars, the Militia Cavalry also required to be equipped with horses as well. It is also used by the Indian Police Service, as a polo pony, and for recreational and competitive riding. The most distinguished Indian high-breeds are:

Bhutia – Like Mongolian and Tibbetian horses,

Kathiawari – Western India breed intended to be a desert war horse,

Manupuri – Famous for their unruffled demeanour and learning ability,

Marwari – As an ambling gait and a superior level of hardiness ,

Spiti – A mountain-based breed,

Zaniskari – In many respect similar to Spiti, Chmmarti – A well-muscled, can easily survive cold temperatures, and

Deccani – Arabian and Turkic crossbreeds with local ponies; “a perfect compendium of all the qualities required in a campaigner. ”He doubted if even the war-born Arabian Badoo can be deemed the superior of the ponies bred on the banks of the Bhima and Tapti”. [Burckhardt]

HORSES IN CALCUTTA Bengal never had any better horses than the Bhutia and the Manipuri breeds of local origin. So long the Sonargaon river port was in operation, Bengal not only received regular supplies of imported horses, but also witnessed the transportation of some of these war machines to the Deccan and China. [Chakrabarti]. The other centre was the Sonepur Cattle Fair for one month long trading of animals – the largest in Asia.

Esplanade . Artist: William Daniell (1769-1837)James Baillie Fraser.1814

Horse Bathing in Ganges near Prinsep Ghat. near

Horsemen near Old Fort (Tank Square) (now CliveStreet)_Charles D’Oyly1842. Courtesy:_BL

The emergence of Bengal as a regional political entity during the early medieval times must have increased the demand for war horses, but it was never so desperately pressing as the English felt after they lost the 1756 Battle of Calcutta. “The question of our horse supply, though primarily a military one, is far from exclusively so.” [Burckhardt] Burckhardt was right. Life in Calcutta literally depended much on horse power, otherwise Calcutta would have remained stand still even though there had been elephants, camels and bullocks roaming on roads carrying passengers and goods. None of those animals were as agile and sportive as the horses in battlefields, roads and lanes, racing grounds, or ambling for a promenade.

Since the city was rebuilt on the ashes of 1756 Battle horses were being imported in huge quantities particularly from Arabia, Britain and Australia.

A Horse and His Trader, circa 1800 Painting; Watercolor, Opaque / Artist: Bagta. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

ARAB HORSE The oldest pure breed in the world, Arab horse is actually the horse of the the wandering Arab – the true Bedouin. The animal possesses incomparable virtue as reverend of hardship and master of abstinence. Its strength and stamina apart a particular form of elegance has made it an enviable sire to breed superior horses everywhere in the world. Either directly or indirectly, the Arabian contributed to the formation of virtually all the modern breeds of light horse. As found in some critical studies, the qualities of the Arabian horses in foreign lands considerably vary. The characteristics of the Arabian horses in India differ from those bred in Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia. [Curr]

The Arabian is a symmetrical saddle-horse, not a racer – with a bright, alert outlook and great pride of bearing. Men who look only at their stop-watches may be disappointed; but not they who love to look on horses racing. [Daumas] As the people of Persia and Arabia didn’t like mares to go out of their countries, the horses traded were invariably stallions. Over centuries of similar trading – the earlier influx was in the Mughal era – it’s thought the native horses and ponies of India thus gained a lot of Persian and Arabian horse genes. In Bombay during the British era, Arab horse dealers set up stables for selling – most held 1,000 to 1,500 horses. [Lane]

ENGLISH HORSE The East India Company in an endeavour to improve the native breeds of horses established a special department, called ‘Stud Department’ in 1794. Both for political and economic reasons, the Company desired India should produce the horses necessary to mount both British and native cavalry, and to horse the artillery. Colonel Hallen gave a list of thirteen country-breeds of Indian horses described as ” possessing good powers of endurance, and showing thereby blood, but generally wanting in size, and many too small for the work of the Indian Army, constituted as it now is ; though some of purely local breeds can be found fit for native cavalry.” [Gilbey}

European man with a horse in India by Bourne & Shepherd, 1882. Source: Commons

Militia Cavalry of the East India Company

After four decades the British raj abandoned the project, and set up the ‘Army Remount and Horse-Breeding Departments’ in 1876 to introduce the ‘Diffused System’ , which used the Thoroughbred sires and India mares treating the thirteen different Indian breeds of horse as one, all mares being classed as ‘country-bred mares’. The animal got by the English thoroughbred “is, as a rule, handsome in top and outlines of back, hind quarters, and carriage of head and tail, but is often shallow in girth and back rib, light in barrel, and from 70 to 8o per cent, are leggy and deficient in bone of limb. Diseases of legs are more common among thoroughbred stock. It provided no means nor machinery whereby the result of using any given stallion on any given mare can he ascertained. Sir John Watson’s gravest objection is that because of the ‘Diffused System’ there does not now exist in India even an experimental stud in which the results of different crosses can be observed. [Glibey]

AUSTRALIAN HORSE Horses first arrived in Australia in 1788, with the First Fleet of prisoners. Like the Arab and the Deccan pony, Waler owes his qualities to the conditions of life amid which he is bred and not on their stud-farms managed on English principles, but chiefly on the grasses which he can pick up for himself on Nature’s own bountiful bosom. Australian horse traders chiefly sold horses to India – where the Waler got its name picked from “New South Waler” – a horse from Australia. In India many famous men and regiments rode Walers – from the Viceroys and Rajah’s down, but pricey for common civilians, like Rudyard Kipling’s father John Kipling who always adored a Waler but could never afford to buy one. [Lane]

European man with a horse in India by Bourne & Shepherd, 1882. Source: Commons

New Mode of Shipping Horses to India.. Wood engraging. 1880. Courtesy: Waler portal

Lumsden Horse on parade.Calcutta_Bourneand shepherd_18xx. Source:AngloBoerWarMedal c 1875-6

In 1836, the first Governor of Perth city, Admiral Sir James Stirling, received an anonymous letter from Calcutta enquiring about a spot in Albany that can combine good climate and port facility for the purpose of breeding and exporting quality horses for catering the needs of the British India cavalry. A decade after The Hobart Town Courier of 30 January 1845 reported export of horses from Australia to India for the first time. The ‘Waler’ horses were exported from Sydney to the Indian Presidencies. Australia was chosen as an alternative source not only for being the closest supplier but also because of its breed of healthy horse. Horse buyers from India representing the Remount service would attend horse sales in Adelaide. Kidman’s annual horse sales held at Kapunda attracted local and Indian Army horse buyers. In turn, there were South Australians who bought horses from overseas to breed their own stock with and so improve their horses’ speed. Some horse dealers like the Pathan tribesmen from the Quetta, in Pishin district, took their horses down the Ganges Valley, most likely as far as Calcutta, where they sold some horses to Australians.’

In the end, Australia became the principal supplier to the 39 regiments of Indian Cavalry and about 7 more of the British Cavalry, each consisting of 1000 horses. The over all demand was pretty high, indeed, even without taking into account the fact that ‘people did play polo, apart from just hacks’, and horse racing became popular recreation around 1810. [Westrip]

A pair of racehorces.By Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya (1830-1850). Courtesy: Christie

HORSE MARKETING IN CALCUTTA In Calcutta horse business initially started in Loll Bazaar- Cossaitollah locality then moved toward Dhurrumtollah where several horse liveries and stables grew to provide all round professional services. In Burraha Bazaar there is still having a locus called Pageya Patty, which might have been earlier a market sector for horse trading, as because the rare and homonymous Bengali word ‘pageya’ (পগেয়া) is used for a ‘breed of horse’ from a particular province’. [চৌধুরী]

The earliest livery stables, as recorded, were established adjacent to the celebrated 18th century tavern, Harmonica, by certain Mr. Meredith. The erstwhile Meredith’s Lane, which connected Bentinck Street with Chandney Choke Lane, derived its name from this Mr. Meredith’s Livery Stables. In Cossaitollah also was the shop of Mr. Oliphant ‘Coach-maker’, the rival of Messrs Steuart and Co., at Old Court House Corner. On Chitpore Road there existed a horse mart, few stables and coach-factories. With the southward expansion of the Calcutta township across Govindapore a number of new horse establishments clustered on Dhurrumtollah Street, to cater all kinds of horse related services and facilities to private and corporate clientele. The most known horse sellers and livary stable keepers among them were: TF Brown & Co. (Partner: Thomas Flitcher Brown), Cook & Co. (Partner: T. Greenhill), Hunter & Co (Partner: John Sherriff). Martin & Co. (Partner: J.P. Martin), and T. Smith & Co. The Grand Hotel in Calcutta had a “Waler Corner” where Australian horse traders met; often after the horses were sold at the Army Remount Depot at Alipore. Some traders such as Jim Robb also stayed in Calcutta.

HORSE CULTURE IN CALCUTTA Horse induces a sense of freedom from monotony – a sportive spirit to win the best at work and leisure. In Colonial Calcutta leisure and recreation became indispensable parts of the social and cultural life of Europeans and native aristocrats. [Mukherjee] Horses have had the primary role to play in the new form of recreation culture, such as hunting, playing polo, horse racing, fencing and pleasure riding.All these were being played in India since long. Yet it was the British who brought some characteristic changes into the games by introducing new sets of rules acceptable worldwide as standards. These reinvented games, however, were meant to be played exclusively by the ‘whites’. For long, natives were not allowed to approach playgrounds, the Respondentia Walk or the King’s Bench Walk on the riverside, the Eden Gardens, and select parts of the Maidan. Mountain Police patrolled the areas to protect the white people’s privilege, besides their regular duty of escorting shipments from river-ports to the safe location. In a changed environment of collaborative Anglo-Indian enterprise, native aristocrats started taking part in all masculine brands of outdoor games.

MOUNTED GAMES

Driving tiger out of a jungle; colored sketch by Thomas Williamson. Source: East India Vade Mecum. 1810

Hunting Hunting wild beasts on horseback is an ancient frantic game that the Europeans much loved to play while in India. The practice of chasing and killing wild animals, what the food-gathering humans commonly did for their survival and defence, turned into a trigger-happy recreation for power loving civilized people. The oriental princes, British and European civilians and dignitaries were the ones most interested in the game locally known as shikar. There were wild habitats all over the country in every province. One of the most tiger-infested jungles, Sundarban was stretched up to Govindapore before the Fort William II constructed. They say, Warren Hastings had a luck to shoot a Royal Bengal tiger on the spot where the St. Paul Cathedral stands today. [Cotton] Chitah hunting at Barrackpore Park was a favourite sport for the Governors-Genral and Viceroys since Wellesley ’s time. King George V had shot no less than 39 tigers and 4 bears when he visited Nepal in 1911. After half a century, his granddaughter Queen Elizabeth when visited India, wished she had a live calf as bait in her tiger hunting expedition. The wish remained unfulfilled due to Mr. Nehru’s interference. An estimated 80,000 of tigers were killed from 1875–1925 and probably more till 1971 when hunting tigers was totally banned. In modern world the hunting has been redefined in terms of fishing, wildlife photography, birdwatching and the like sport items that do not threaten worldlife. [Dasgupta]

Polo Polo, often referred to as ‘the game of kings’, was invented and played by the commoners of Manipore, where the world’s oldest polo-ground, Mapal Kangjeibung, still exists. From obscure beginnings in Manipore, the modern version of polo was developed and soon being played in the Maidan by two British soldiers, Captain Robert Stewart and Major General Joe Sherer.

A polo game: the dervish and the shah on the polo field from a Guy u Chawgan by Arifi (d.1449). Courtesy: Smithsonian Nat.MuseumAsian Art

Calcutta Polo Club of 1862 Drawing by unidentified artst. Source: justGo

Manipore Polo Team’s first visit to the Calcutta Polo Club in 1884. Courtesy: HindusthanTimes. Possibility photographer: Bourne. 1864

They established the Calcutta Polo Club in 1861, and later spread the game to their peers in England. The club runs the oldest and first ever Polo Trophy, the Ezra Cup (1880). The modern Polo has been necessarily a sport meant exclusively for wealthy people capable of meeting its fabulous expenses and extensive leisure time that the heads of the princely states, high ranked British military and administrative personnel. Prominent teams of the period included the chiefs of the princely states of Alwar, Bhopal, Bikaner, Jaipur, Hyderabad, Patiala, Jodhpur, Kishengarh and Kashmir. The majority of the Cavalry regiments of the British Army and the British Indian Army also fielded teams. The civil service bureaucrats to whom the sports and pastimes peculiar to the country are accessible ‘upon a scale of magnificence and affluence unknown to the English sportsman, who ranges the fields with his gun and a brace of pointers, and seeks no nobler game than the partridge or the hare’. [Cotton] The gorgeous game of polo attracted the fanciful young minds, irrespective of financial constraints, if any. Winston Churchill loved polo and played the game vigorously. Aga Khan the celebrated racehorse owner and equestrian found in young Churchill, then an officers of the Fourth Hussars stationed at Bangalore, an irrepressible, and promising polo player. In November 1896 Churchill’s team won a silver cup worth £60. [Langworth ] “Polo became a game that in many ways, did more than ambassadors to promote goodwill in the days a man was judged by his horse…” . [Lane]

Horse Racing Horse racing, one of the oldest of all sports, developed from a primitive contest of speed or stamina between two horses. In the modern era, horse racing developed from a diversion of the leisure class into a huge public-entertainment business.

Calcutta being the first centre of British power in India commanding large cavalry regiments, all mounted sports such as hunting, polo and racing were encouraged to be played. Organized horse races were first held in India on 16 January 1769 at Akra, near Calcutta, where they were held on a rough, narrow, temporary course for the next three decades. Lord Wellesley, as soon he arrived India in 1798, stopped horse racing and all sorts of gambling. After a lull the Calcutta Races again commenced under the patronage of Lord Moira. In 1812 the Bengal Jockey Club laid out a new course in the southwest part of the Maidan. A viewing stand was built in 1820 to watch racing horses in the cool of mornings just after sunrise. The Calcutta Derby Stakes began in 1842, where maiden Arabs ran over 2.5 miles. Five years after the Calcutta Turf Club was founded on 20 February 1847. In 1856 the Calcutta Derby was replaced by the Viceroy’s Cup. In 1880 public interest in racing grew when races started to be held in the afternoons, and new stands were built.

A Grey Racehorse and a Groom. Pencil and watercolour by Sheikh Muhammad Amir. Courtesy: Christies

Race Cource Calcutta. Undated/ photographer unknown. Source: Hippostcard (New Market)

Racing becomes Calcutta’s biggest wintertime attraction, except during a Royal visit —”and then the Turf Club contrives to work the two things very much together. For months women have studied pictured lists from Piccadilly, searching for something to wear at the Races. New milliners’ signs adorn the city’s streets, as short lived as the flies, just for the Racing season. The Indian has unpacked his shawls of many colours only to sport it on the crowded course where the patterned shoulders work a mosaic that is hardly ever seen in a human picture.” Minney who visited Calcutta in early 1920s left a spectacular description of the city in sunny winter. “Gay and busy, it is a season that attracts a multitude from the world’s four comers. They come for the racing,, they come for frivolity, but they come primarily for the climate. … Calcutta would become the most coveted place in this sad globe, more cursed than blessed with climate.” [Minney]

Horse Riding The horse is a partner and friend of humans for more than 5,000 years, and the art of horseback riding, or equestrianism, took most of it to be evolved, of necessity, with maximum understanding and a minimum of interference with the horse. In Colonial Calcutta, as the contemporary narratives reveal, riding was not a monopoly of the cavalry and the rich who rode for sport, as it was the case elsewhere till the 20th century. After Plassey, in the revived Calcutta society, horse riding was regarded as a valued social asset and symbol of prestige.

Portrait of a lady rider with her horse and indian groomsman. Like the photograph taken by Thomas Alfred Rust. Courtesy: Cabinet Card Gallery

The Course at Calcutta. Drawing by ADA Claxton.c1859 Source: Alamy

Girls on horseback on Calcutta Road. Date unknown. Photographer unknown. Courtesy: Open Magazine.

The opening of many new riding clubs and stables has made riding and horsemanship accessible to a much larger segment. Calcutta then was different in too many counts, but “nothing in which we differ more remarkably from them than in the distribution of our time”. In the early days of Calcutta, the midday dinner and the afternoon siesta were recognized institutions. “The dinner hour here is two,” wrote Mrs Fay. In the days of Warren Hastings “reposing, if not of sleeping, after dinner is so general that the streets of Calcutta are, from four to five in the afternoon, almost as empty for Europeans as if it were midnight. Next come to the evening airings on the course, where everyone goes, though sure of being half-suffocated with dust.” [Cotton] The scene here in the evening was very lively ; soldiers exercising in the square; officers riding on horseback, or driving in gigs ; the band playing on the esplanade; groups promenading. [Bellow] About this garden, as well as the Maidan and Strand Road and to the south of the Eden Garden are the places to see and to be seen, because all the grand folks of Calcutta of an evening go on foot, or riding, or in beautiful barouches, broughams, phaetons, buggies, etc., drawn by beautiful horses. [Cesry]

Good riding and driving horses may be had from 400 to 600 rupees each, Arabs for a bit more. On setting up housekeeping in Calcutta, or in the provinces, a new recruit in civil service earning Rupees 400 a month, must provide himself with bed, tables, chairs, cooking utensils, china, plate, table linen, a buggy, and buggy horse, and a riding-horse. The buggy being kept then principally for business, visits, and day trips, the riding-horse is requisite for morning and evening exercise. [Roberts] During the days of Cornwallis, they used to get on horseback just as the dawn of day begins to appear, ride on the same road and the same distance, pass the whole forenoon. [Bagchi] The Eden sisters, particularly Emily, was extremely fond of riding horse wherever they go. She found riding a foot’s pace cooler than the carriage. The air she felt coming more round one on horseback than in the carriage. She had a little pony-carriage with no head to it, and wicker sides, and extremely light, and that was much the coolest conveyance they had; besides that, she says “it will go in roads which will not admit of our carriage” [Eden] After nearly four decades, in a more liberal colonial climate we find Jyotindranath Tagore along with his young wife Kadambari Devi riding on their horses down Chitpore Road to the Eden Garden for an evening prom. [Sen]

The pleasure of horse riding has been an added attraction for the European settlers in Calcutta. Except the army horsemanship, ambling or easy walking on horseback was the most popular mode of riding – a slow, four-beat, rhythmic pace of distinct successive hoof beats in an order. Alternately it may be extended walk of long, unhurried strides. One needed to undergo a systematic training to execute precisely any of a wide range of maneuvers, from the simplest riding gaits to the most intricate and difficult airs. This was true for the British and Indian soldiers as well as the civilian men and women. The first Riding school was established in Calcutta as early as in 1790s followed by more in the next century to teach whoever interested irrespective of sex and age. The untold stories behind those early Riding Schools will be posted next.

REFERENCE

Bagchi, P. C. (1938). The Second city of the Empire. Calcutta: Indian Science Congress Assoc. Calcutta: Indian Science Congress.

Bellow, F. J. (1880). Memoirs of a griffin; or, A cadet’s first year in India. London: Allen. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/memoirsagriffin00bellgoog/page/n5/mode/2up

Burckhardt, J. L. (1831). Notes of the Bedouine and Wahabees collected during his travel in the East;vol; vol.1(2). London: Bentley. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/notesonbedouins00burcgoog/page/n6/mode/2up

Cesry, R. (1818). Indian Gods, sages and cities. Calcutta: Catholic Orphan Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.128152

Chakravart, R. (1999). Early Medieval Bengal and the trade in horses: a note. No Title. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient., 42(2). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3632335

Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1942). Horse-Riding in the Rgveda and Atharvaveda.No Title. Journal of the American Oriental Society. Vol. 62, No. 2 (Jun., 1942), Pp. 139-140. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/594467

Cotton, E. (1909). Calcutta old and new: a historical and descriptive handbook of the city. Calcutta: Newman.

Curr, E. M. (1863). Pure saddle-horses, and how to breed them in Australia. Melbourne: Wilson and Mackinnon. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/puresaddlehorses01curr/page/n6/mode/2up

Dasgupta, R. R. (n.d.). Killing for sport: To live, we Indians need to let live too. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/SilkStalkings/killing-for-sport-to-live-we-indians-need-to-let-live-too/

Daumas, E. (1863). Horses of the Sahara, and the manners of the desert. London: Allen. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/horsesofsahara00daum/page/n7/mode/2up

Eden, E. (1872). Letters from India; vol.1. London: Bentley. Retrieved from https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/eden/letters/letters.html

Gilbey, W. (1906). Horse breeding in England and India and army horses abroad. London: Vinton.

Jaccob, J. (1858). The Views and opinions of Brigadier-General John Jaccob. CB; (C. L. Pelly, Ed.). London: Smith & Elder. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.ao/books?id=mn9CAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=pt-PT&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Khan., I. A. (1984). The Import of Persian horses in India 13-17th centuries. In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. (pp. 346–351). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40173319

Lane, J. (2016). Buying Walers. Retrieved from https://walers.blogspot.com/2016/07/buying-walers-australian-horse-traders.html

Langworth, B. F. (n.d.). Churchill and Polo: The Hot Pursuit of His Favorite Team Sport, Part 1. Retrieved from https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/polo-churchills-favorite-team-sport/

Minney, R. (1922). Round about Calcutta. Calcutta: OUP. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/roundaboutcalcut00minnrich

Mukherjee, S. (2011). Leisure and recreation in colonial Bengal: A sociocultural study. In IHC: Proceedings, 71st Session, 2010-11. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147545?seq=1

Roberts, E. (1839). The East India voyager, or, Ten minutes advice to the outward boun. London: Madden. Retrieved from https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/193246575?q&versionId=211570278

Sen, A. P. (1993). Hindu Revivalism in Bengal, 1872–1905: Some Essays in Interpretation. New Delhi: OUP. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ZCwpDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT47&lpg=PT47&dq=jyotirindranath+maidan+horse&source=bl&ots=mpVG5W2xkS&sig=ACfU3U30J0X-sa2ToOMLn1AjgzWARWVcaA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjwkJOUrajoAhVaeX0KHYMGCRsQ6AEwAHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=jyotirindranath m

Westrip, Joyce P, and P. H. (2010). Colonial Cousins: A Surprising History of Connections Between India and Australia. Kent Town: Wakefield. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.in/books?id=ALbaCwe6VHkC&pg=PR4&lpg=PR4&dq=A+surprising+history+of+connections+between+India+and+Australia+by+Joyce+Westrip+and+Peggy+Holroyde&source=bl&ots=zzor8RrxQ1&sig=ACfU3U1NylPfKTO2iTXbYFNByhjgvS-0zQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjspeP3yILnAhXs73MBHUpTCMw4ChDoATAFegQICBAB#v=onepage&q=horse&f=false

চৌধুরী, প্রমথ. (1914). চুটকি। প্রবন্ধ সংগ্রহ

https://bn.wikisource.org/wiki/%E0%A6%AA%E0%A6%BE%E0%A6%A4%E0%A6%BE:%E0%A6%AA%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%A8%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%A7_%E0%A6%B8%E0%A6%82%E0%A6%97%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%B9_-_%E0%A6%AA%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%AE%E0%A6%A5_%E0%A6%9A%E0%A7%8C%E0%A6%A7%E0%A7%81%E0%A6%B0%E0%A7%80.pdf/%E0%A7%A7%E0%A7%A6%E0%A7%AA

HORSES AND MOUNTED GAMES IN COLONIAL CALCUTTA

PRELUDE Not until the British revamped army to recapture Calcutta in 1757, horses in India had the leading role in wars, and in everyday public and private life as well.

HORSES AND MOUNTED GAMES IN COLONIAL CALCUTTA PRELUDE Not until the British revamped army to recapture Calcutta in 1757, horses in India had the leading role in wars, and in everyday public and private life as well.

#buggy#buggy horse#eden sisters#emily#horsemanship#jyotindranath tagore#kadambari devi#riding schools#riding-horse

0 notes

Text

Tea, ‘the second most commonly drunk beverage after water’ Ellis, is now being cultivated in more than 61 countries (2018), and consumed by not less than 54 nations (2016). There have been so many varieties of tea, prepared and consumed in so many different ways, all tuned in their respective ecological as well as sociological settings. Britain had no tea of its own, India had. Yet it was the British who grew a tea culture of its own since the time of King Charles II, more accommodative than the ceremonial tea of the Chinese and Japanese traditions, which later globally accepted as a standard.

Camellia Sinensis Categories Courtesy:@Leaves of Tea Ring