Oblivion Records is an independent American music recording company, revived during the pandemic after 50 years to drop the digital release of an historic performance in New York City in 1973. Three of us –Dick Pennington, Tom Pomposello and Fred Seibert– started it in the back room of Tom's hippie record store in Huntington, Long Island. Click here to listen to the Oblivion catalog. Our entire library is available on your favorite music service. Written by co-founder Fred Seibert. [email protected] (Detailed navigation is available with tags on each post. Disqus comments can be left under individual posts.) ©1972-2022, Oblivion Records 2021, Inc. All rights reserved.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

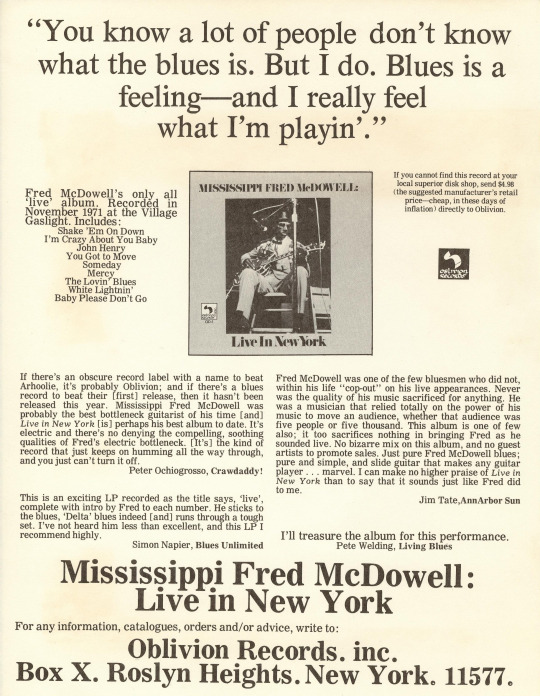

Mississippi Fred McDowell > The Complete Live in New York

Mississippi Fred McDowell The Complete Live in New York November 1971 at the MacDougal Gaslight II

• Available on all streaming platforms

...

Mississippi Fred McDowell: vocals & guitar Tom Pomposello: bass guitar

November 5, 1971, Live at the MacDougal Gaslight II, 116 MacDougal St., New York City Engineered by Fred Seibert, assisted by Roy Langbord Produced by Tom Pomposello & Fred Seibert

Executive producer: Richard H. Pennington III

All songs written by Fred McDowell

Cover illustration of Fred McDowell by Carlos Ramos

...

#OD10#OD-10#Complete Live in New York#1971#Tom Pomposello#blues#country blues#AllFred#guitar#Mississippi Fred McDowell#New York#Manhattan#Village Gaslight

0 notes

Photo

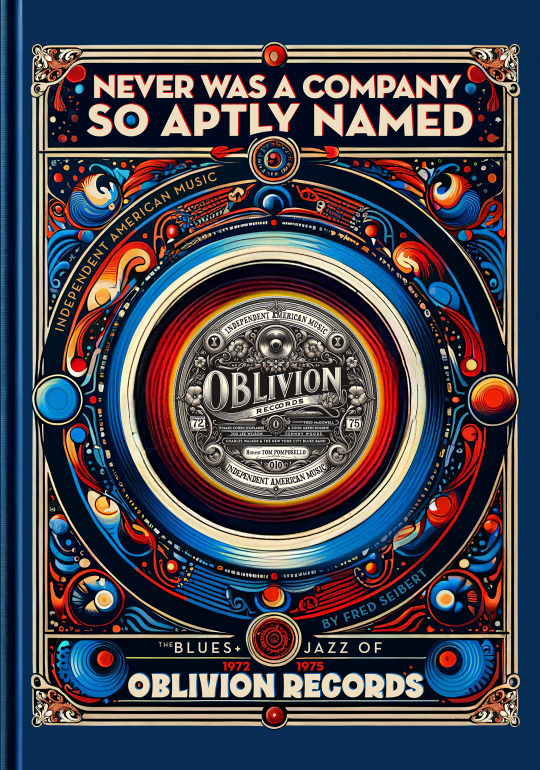

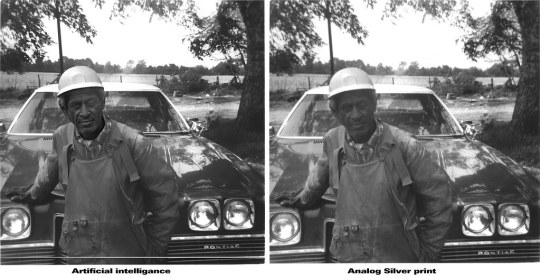

Oblivion Records book cover concept as of April 2024, all elements subject to change.

The state of not forgetting.

It would be a severe understatement to say that Oblivion Records was a successful business. After all, we went belly up within four years of our first release. I’m not implying anything about the quality of our recordings, which, IMHO, are pretty damn good. But seriously, never was a company so aptly named.

oblivion [uh-bliv-ee-uhn]

noun 1. the state of being completely forgotten or unknown 2. state of forgetting

Digital technology for music distribution has kept Oblivion alive in the 21st century. There’s no way we could continue to make most of our music recordings available otherwise. The alternative would’ve been a shame, so we’ve kept up with the easiest ways to share it with listeners around the world.

But, as we get older it occurred to us that our children were too young, or not even born yet, when we had the company in the early 1970s, the era in which all our music was recorded. So, for their sake, we’ve started writing down the behind the scenes of actually getting things done at Oblivion.

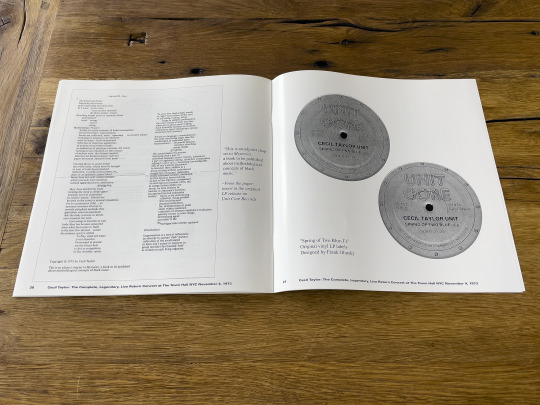

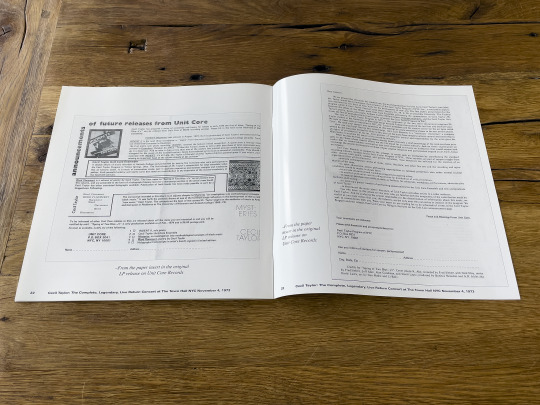

Hopefully, sometime in 2024, we’ll be publishing “Never Was a Company So Aptly Named: The Blues + Jazz of Oblivion Records 1972-1975” (at least, that’s the working title; everything’s subject to change. Record jackets, LP labels, posters and illustrations of the (not much) ephemera we can get our hands on will be included. But, it’s the stories behind the records that will take up most of the 250+ pages.

Will it all be true? Hopefully, but memories fade, spindle and mutilate, so we’ll see.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joe Lee Wilson/Ladies Fort flyer, October 1976, courtesy of Jim Eigo, Jazz Promo Services

How Oblivion came to release Joe Lee Wilson’s Livin’ High Off Nickels & Dimes

Jazz entered my life as a transition from the "rock" evolution led by The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and James Brown, and into the avant-garde, "new music" of Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler and Cecil Taylor. But in the summer of 1972, when the smoke signals started coming out of WKCR-FM about an amazing live shot of the jazz vocalist Joe Lee Wilson, I wasn't yet able to make the backwards leap to his mainstream sounds. That would take me a little while.

Starting in 1970, I was almost the exclusive engineer for live broadcasts at Columbia University's student run radio station. I hadn't any particular knowledge or talent –I was literally making things up as the musicians came by– but because I eagerly volunteered and no one else seemed to have any interest. My background as an organist in amateur rock bands had proved to me that I wasn't motivated to become a professional, but the infection of recordings had taken hold including an overriding interest in figuring out how to accomplish them. And when one of my earliest airshots was released as an actual vinyl album by German band leader Gunter Hampel I was completely hooked. Sessions for a few dozens of performances followed.

Of course, I wasn't actually the only one doing the recordings. But since I wasn't working at the station in the summer of '72, when the New York Musicians’ Jazz Festival* started showing up to promote their concerts, other folk stepped up.

Don Zimmerman was part of the technical team that kept the radio station functional and on the air. It didn't occur to me that he had any music chops. When I was told that he'd engineered the Joe Lee session, and that it sounded great, I suppose I was more than a little indignant. and to be honest, a lot jealous. After all, I had been the one getting all the accolades for the live shots over the past couple of years.

My revenge? I steadfastly avoided listening to the Zim recorded, Joe Lee tapes.

FOO (friend of Oblivion), my great friend and roommate, Nick Moy, had no such reservations. I knew him as a devout lover of classical music, and was surprised that he was also a dedicated jazz listener with much wider appreciations than me. He had a particular interest in jazz vocalists and had attended the original session. When we started Oblivion Records, he worked me hard to convince us to consider the session for a vinyl release.

Tom, Dick and I agreed that Oblivion's mission was to expose emerging artists to wider recognition. Once I got over myself and listened to the extraordinary voice on that tape from July 1972, I realized we had the makings of a special album.

.....

*The famous Newport Jazz Festival had been banned from it's Rhode Island home after raucous, young rock fans rioted. Relocated the next summer to New York, then the jazz center of the universe, city based musicians, world class but not necessarily household names, felt left out. They decided to put on an alternative festival as a protest.

Click here for more stories about "Livin' High Off Nickels & Dimes"

2 notes

·

View notes

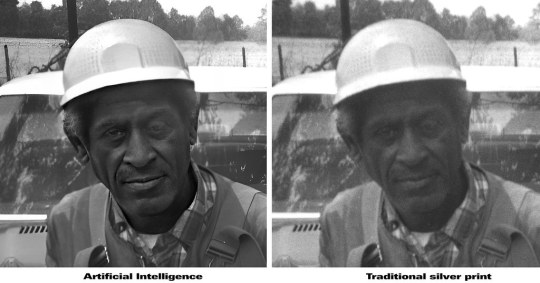

Photo

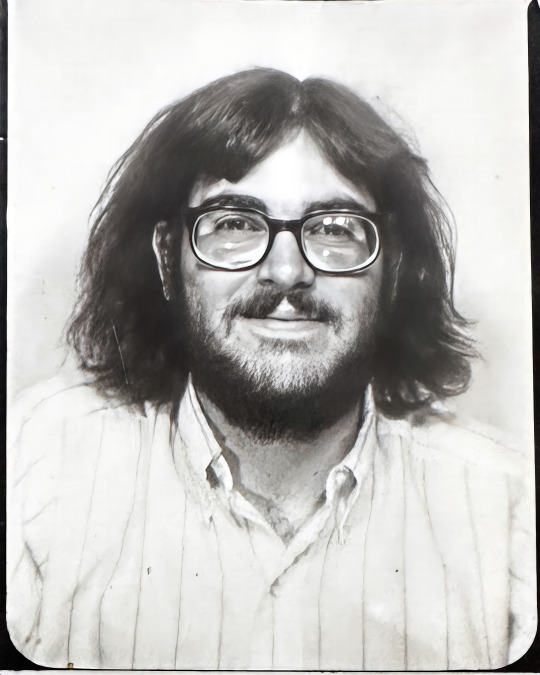

Alan Goodman, photobooth 1970's

Alan saved the day.

”Jazz Ain’t Nothin’ But Soul” Part 2 (Part 1 here)

TThrough some dumb luck and a belief in our artist, Oblivion almost had a hit with “Jazz Ain’t Nothin’ But Soul.” To my ears, and on Van Jay’s mainstream jazz show on WRVR-FM in New York, Joe got it just right, a performance that hit it better than Betty Carter’s original or any others, with an exuberance and joie de vivre that let anyone listening that jazz was... it!

youtube

But, I had completely screwed up.

Sure, Van was playing the track like crazy, and the rest of the RVR jocks followed. We were getting calls from retailers throughout the New York metropolitan area, they wanted to record! Yay!

Nooooo!!!!! The record I’d delivered to the radio station was a test pressing! The only copy we had. And, to add insult to injury, Oblivion was pretty much broke. I was just out of college without a job, Tom Pomposello ran a small record store that gave him enough money to shelter his young family, and Dick Pennington –our initial financial savior– didn't have any more resources for us.. We had the test pressing, but we hadn’t OK’d the pressing order at the plant because we couldn’t pay for it!

My buddy Alan Goodman stepped in and saved the day. He provided us with some cash from an inheritance. What a friend. He was pretty much living hand to mouth himself, but after he bought himself a 16mm movie camera –Alan was in film school– he gave me the rest. It enabled us to make the pressing order.

(I never paid Alan back directly. But, I tried to make up for it, working at MTV together, changing the way people used TV in the cable era. We eventually become partners in the world’s first media branding company, and becoming brothers-in-law and lifetime friends!)

We eventually got the records, sent them to retail, but... it was too late. We’d missed the window.

I made a total rookie error. “Jazz Ain’t...” became a classic “turntable hit.” It deprived Joe –and Oblivion– of a real hit, the only one he’d have in his career. I’ve never forgiven myself, Joe deserved better.

0 notes

Photo

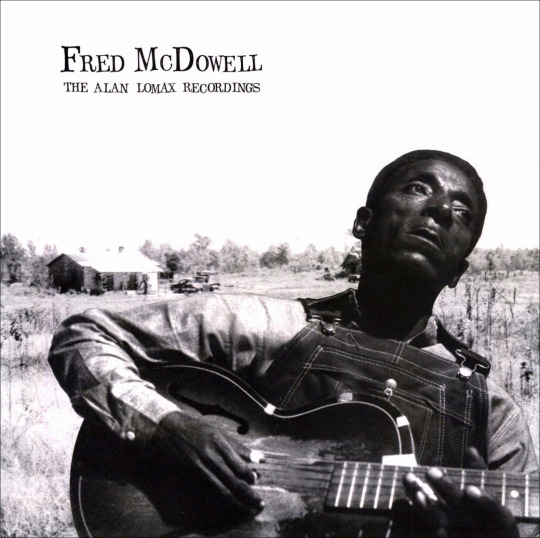

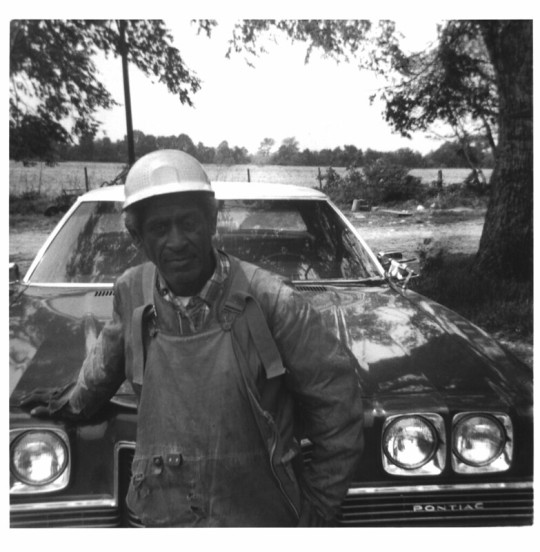

Fred McDowell: The farmer who emerged from the woods and made a masterpiece

I thought it might be good for newbies to Mississippi Fred McDowell –like I was when I recorded “Live in New York”– to find out about where Fred came from, recording wise. This article in the UK webzine, Far Out, lays it out pretty well. You might want to dig deeper into folklorist Alan Lomax, but more importantly, you'll get a glimpse of the ambition that drove Fred from a Mississippi farm to his well deserved worldwide acclaim. -Fred Seibert.

By Tom Taylor @tomtaylorfo Far Out Magazine Sat 18 November 2023 22:00, UK

Some blues players can get their guitars to tell a story; Fred McDowell could get his to sing an opera akin to a southern Les Mis. “With Fred McDowell, I just love the way he articulates the notes,” fellow blues guitarist Bill Orcutt explains. “I’m hardly unique in that, but there’s just something about that that I love.” He’s not alone in that love either; everyone from Keith Richards to Bonnie Raitt have cited him as a star that they have attempted to emulate.

However, the one element nobody could ever copy was the humble backstory that brought him to the world. Long before he earned the prefix of Mississippi and became a big attraction at juke joints, got swamped backstage at folk festivals, or had his track covered by The Rolling Stones, he was just strumming away to an audience of nearby wildlife on his porch after a long day at work. Occasionally, he’d find himself in a situation where someone might toss him some loose change, but any notion of fame seemed unfamiliar.

But his skills were profound all the same, and fate would drag him towards another American numen on his travels. Alan Lomax was a roving ethnomusicologist, which is a big word for a curious fellow with a portable recording device that could capture the nation’s true folk on the move. One day, during Lomax and Shirley Collins’ great Southern Journey expedition, they rocked up in Como, Mississippi. They were intent on capturing the music at a local dance and the Young brothers’ fife and drum ensemble.

It was 1959, and McDowell was a 54-year-old wondering what his legacy would be beyond the farm he kept. So, without much fanfare and no warning, he decided to pick up his guitar, weave his way through the local woods, and rock up at Lonnie Young’s porch, where the recording was said to be taking place. Lomax and Collins lent him their ears, hit record, and old McDowell began to play.

Half a century later, if you close your eyes while listening to the masterpiece now known as The Alan Lomax Recordings, you can almost see the overalled maestro on the creaking porch ahead of you, hear the rustle of the southern breeze through the lowering tupelo trees, and smell the dancehalls buffer in the air. Of course, some of that is due to the suggestion of the cover art on the Mississippi Records pressing, but what I’m trying to convey is the dogeared sincerity that renders this authentic tape so beguiling.

Even at the time, Lomax and Collins were so flummoxed by the humility and skill of this unknown farmer that they quickly whisked their tapes off to a blues label, and in his autumn years, McDowell became an internationally renowned star, typifying what was best about the blues when the revival movement had somewhat muddied the waters — he was the new (old) find that the kids were craving.

He would soon rub shoulders with the next generation, teaching Raitt how to play slide guitar, touring with the likes of Big Mama Thornton and John Lee Hooker, and embracing the flattery of being covered by rockers despite declaring himself that he did not play rock ‘n’ roll. He left the farm behind and enjoyed a good 13 years of fame until his death in 1972, aged 68, but his old porch was never truly that far from his artistic thoughts, so even beyond the masterful Lomax Recordings, he’s the bluesman who can capture the earthiness of the South with more verity than anyone.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The roots of Oblivion: Interview with Kropotkin Records, July 21, 1970.

Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, one of the inspirations for Kropotkin Records

Oblivion Records really started when a new, hippie record store opened in my hometown, Huntington, Long Island, New York. One of my best music buddies, Mike Altshuler, told me about the joint, and I was so excited that a place with “our” music opened up that I ran right down. Despite my lack of experience I blurted out to the owners that I wanted to interview them on my new college radio show. (If you listen, you’ll hear that none of the three of us were all that accomplished.)

The three of us became fast friends, and less than a year later, Tom asked me to record his gig in Greenwich Village accompanying Mississippi Fred McDowell. And the train left the station and we started Oblivion with third partner Dick Pennington.

There are two versions of the interview here. The first is a heavily shortened edit to focus it on key points and the main ideas. Below that is the entire interview, lightly edited for clarity.

Interview with Rob Witter & Tom Pomposello, by Fred Seibert 1970 Proprietors of Kropotkin Records 273 New York Avenue Huntington, NY

Interviewed by Fred Seibert @WKCR-FM Ferris Booth Hall, Columbia University 115th Street & Broadway New York City Recorded July 16, 1970, aired July 21, 1970

Fred Seibert: And now, on WKCR-FM in New York, we have Tom and Rob from Kropotkin, a record store out in Huntington, Long Island. Let’s dive into how you got started.

Tom Pomposello: Well, we both grew up in the same town and knew each other, though Rob was more friendly with my older brother. We both worked at a record store that had high prices, and that’s where the idea of opening our own store began.

Rob Witter: Yeah, we wanted to create a store with cheaper prices because we were tired of being ripped off.

Fred Seibert: How did you pick your location?

Tom Pomposello: We chose Nassau County, specifically Roslyn, because we thought there was money to be made there. But the rent was too high, so we ended up in Huntington.

Fred Seibert: How did you finance it?

Tom Pomposello: We started with about $1,000, which was mostly our own money.

Fred Seibert: How’s business going?

Tom Pomposello: We’re starting to make back our investment, but most of our money is still tied up in stock. We’re not in it for big profits; our goal was to offer cheap prices and create a community space where people could hang out and buy records.

Fred Seibert: Why the name Kropotkin?

Tom Pomposello: It reflects our personal beliefs. Prince Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist who opposed the structures of capitalism. We wanted our store to embody some of those ideas, like offering an alternative to the high prices and rigid systems of traditional stores.

Fred Seibert: Are you actually making any money?

Tom Pomposello: Not much. We work 72-80 hours a week and take home about $40 each. We’ve only recently started paying ourselves, but our focus has always been on creating something different rather than getting rich.

Fred Seibert: Do people see you as anarchists?

Tom Pomposello: Some do, but it’s hard to be true anarchists while operating within a capitalist system. We’re trying to offer something different, but we’re still part of the same old exchange of money for goods.

Fred Seibert: Do you see your business expanding?

Tom Pomposello: Not really. We’re not here to put others out of business. Our goal is to provide a cheap alternative, but we know we’re not going to revolutionize the industry.

Fred Seibert: What about the pressure from bigger stores like Goody’s?

Tom Pomposello: We haven’t felt much yet, but we’re aware it could happen. We’re small, and they could easily pressure our distributors, which would hurt us.

Fred Seibert: What’s your ultimate goal with the store?

....

And here is the entire interview:

Fred Seibert: And now, on WKCR-FM in New York, some sounds and thoughts of people from a liberation record store out on Huntington, Long Island. The name of the store is Kropotkin. I hope that some people listening to this will listen closely and take to heart some of the things that these guys are saying. Their names, by the way, are Tom and Rob.

One thing I should say is that the... there are places within the interview where a word sounds very muddled, and that was probably where I had to take a word that was said, and because of some FCC regulations, reversed it, because if we got a complaint here [about] an obscene word, the FCC would have to take some sort of action that wouldn't be good for our station. There were a few places where there was some sloppy editing. My fault. Inexperience. But that's how it goes.

So now, uh, some Kropotkin.

Fred Seibert: Why don't you just tell me what happened, how you got into it and the whole bit.

Tom Pomposello: Well, Fred, it happened this way...

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: We both, like, grew up in the same town together, and we just knew each other. But like, he was more friendly with my older brother, and so then...

Tom Pomposello: I still am.

Rob Witter: (laughs) Okay. And so then. like, we were joined at this record store like that, you know, it was supposedly the cheapest around then, but it was still ripping them off, 'cause the prices were $3.70, $3.69, or something like that.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: Well, first, see, I worked at this appliance store, like a record store, for about six months, and then this guy came along (laughs) and, uh, we kinda ran the record thing there. You know what I mean? And that way, like, he got in good with some of the distributors and that, you know. And I knew one of the guys from Columbia [Records] a little bit. And, uh, they used to think he was the manager up there.

Tom Pomposello: And there the idea gelled that someday we would open a record store of our own. At that time, we were still straight necks however, and we thought we would rob everybody else just like...

Rob Witter: (laughs) Now we do...

Tom Pomposello: Well, we, we knew would have cheap prices.

Rob Witter: We wanted to make it cheap and like... It was at a time where there weren't, like, too many head shops either.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: It wouldn't have worked. We just didn't know it then.

Tom Pomposello: It would've been a disaster.

Rob Witter: So then like we, we both quit and, uh...

Tom Pomposello: We went away to school.

Rob Witter: Right.

Tom Pomposello: Is what happened. And then around the middle of April of this year, uh, I wrote him a letter, uh, capitalizing on our old plans.

Fred Seibert: Right. How did you happen to pick on the place that you opened up?

Rob Witter: Well, he wrote me a letter and said like, "Definitely Nassau County, [Long Island]." (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: The Roslyn area because there's a lotta bread, man.

Rob Witter: I was thinking about it.

Tom Pomposello: And then we took a look at the rent in Roslyn.

Rob Witter: That's why there a lotta bread. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: That's why we're, we're capitalist pigs.

He got home at the end of May, and from there we started going.

Fred Seibert: Right. Where'd you get the money?

Tom Pomposello: Well, we put the whole thing together on very little money to begin with.

Fred Seibert: How much did you need?

Tom Pomposello: Um, we put it together on about $1,000, because we knew what we were doing, ha, ha, ha.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Is that like out of your own personal things, or did you get somebody to say, "Give me some money so I, I can start a record store"?

Tom Pomposello: No. It's from the government.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: We got a grant.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Okay. And have you made it back?

Tom Pomposello: Um, yeah, most of it. We're starting to make it back. Now, most of our money is still tied up in, um, stock.

Rob Witter: We set it up like we had to... have it like, you know, cheap prices and... because we didn't wanna rob anybody and we just... 'cause we were in the same thing, buying records like... and paying exorbitant prices for them. And, um, we just thought it would be, you know, really a good idea, you know what I mean?

We knew it wouldn't be really unique, 'cause like you said, what was it, the, the all-time heavy or something like that, that being the novel idea, it's not... you know what I mean, it's not really novel, but, uh, opening a record store. But we just thought, like, we'd cater to different people if we had to, like you know what I mean, we'd make it like a so-called freak store, but it really wasn't. You know what I mean?

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: We knew it wouldn't be either, but you know, it would seem that way, because the prices were low and we weren't making any money.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: And we'd come in with our, our, uh, suits from Robert Hall's.

Tom Pomposello: (laughs)

Rob Witter: (laughs) You know, our dungarees and everything.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: And that was it, but just, you know, there's nothing really unique about it, as he says.

Tom Pomposello: Never said that.

Rob Witter: Sure you did.

Tom Pomposello: Okay.

Fred Seibert: Okay. The reason I call it a liberation record store is just because I've read papers that had, "These are liberation record stores, and they have a lot to do with..." They try to say it has a lot to do with politics and the economic system and, and the whole bit.

Tom Pomposello: That's right. Why don't you ask us how we got the name?

Fred Seibert: How did you get the name? I, I looked it up last night, and, and they told me that he was a, a Russian, uh, geographer and-

Tom Pomposello: Uh, he was just a philosopher. Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin.

Fred Seibert: A philosopher. Okay.

Tom Pomposello: 1842 to 1921. Got the bass, that's why.

Fred Seibert: Okay.

Tom Pomposello: Um, basically, um, what we were trying to do was, um, more or less name the store, um, to reflect our own personal beliefs as much as we could. Um, Prince Kropotkin was a, was a Russian anarchist, and in many ways, um, anarchism conjures up to people, um, declaring yourselves against what constitutes the real strength of capitalism, um, the state and its principal supports, you know, the centralization of authority and law, which is always made by a few for a few, and also against a, f- a form of justice whose chief aim is to protect authority and capitalism.

But you see, it's really more than this. Grove Press just, um, uh, republished, uh, “Memoirs of a Revolutionist,” Kropotkin's famous book, and in the introduction, they, they sorta give you the impression, um, of comparing him to Abbie Hoffman of today. In other words, he was a, a, a culture- that, "Is a cultural revolutionary who saw the need for a, a change in people's basic lifestyles," and that's what we felt like doing.

Um, for example, social philosophers like, uh, Arthur Lothstein, make this distinction that, um, society, uh, can be envisioned in terms of a basis structure and a superstructure. Um, base and structure are more or less synonymous, in other words, the relationships entailed by, um, you know, ownership relations, okay? And superstructure being the cultural mores entailed by socialist institutions.

Now, what we wanted to get into was... before you can be a revolutionary and have a, you know, a revolutionary base, you've gotta, I think, first work on... a revolutionary superstructure. And that was the importance of our record store, trying to develop, uh, a kind of alternative institution, um-

Fred Seibert: Like the alternative media.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. Where, where people could go and get their records, uh, cheaply, or as we put in our manifesto, just come in and rap with us. We have couches in the store. And, uh, our record prices are about the lowest around. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: They are the lowest around. Um, I know anywhere around on Long Island, where the store is, or around New York, I know... that I know of anyway ...unless you happen to get used records, or a super sale... even... super sales have gone up.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: So you are the cheapest even when they're on, on sale.

Tom Pomposello: Right. Korvette's uh, sale price used to be three cents below our regular price, and now Korvette's, uh-

Rob Witter: 22 cents above it.

Tom Pomposello: Right. It's 22 cents above our regular price.

Fred Seibert: And so you're based on anarchy.

Tom Pomposello: Um, okay, you can say that. We'll let you get away with it. You see, uh, it's hard to say... We're, we're not capitalists the way a whale isn't a fish.

Fred Seibert: Mm-hmm.

Tom Pomposello: You know? It's hard to say that you're not capitalist when you're operating within a, within a, within a capitalist context. There's still that same old, uh, s--t, you know, exchange of money for goods and everything. I...

Fred Seibert: But I was gonna ask you that. I've, I've talked with a few kids and they... one kid said, "Oh, it's a record shop run by a couple of anarchists."

Tom Pomposello: (laughs)

Fred Seibert: And then the other kid that was there said, "Yeah, but they're not really anarchists 'cause look at all this money they're making off of us." Even though they-

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Some people are convinced that you're trying still to cash in on people, uh-

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. Yeah.

Fred Seibert: ...even though you're doing it in a sneaky sort of way.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. A lotta people have gotten that impression. We can say very plainly that we don't make a lotta money, we really don't. We work 72 hours plus sometimes on Sundays fixing up the place, and also doing the books. Comes out maybe to 80, 90 hours a week, and we never have brought home more than $40 a piece.

Rob Witter: We've only... First, we've only gotten paid like the last couple... this week. Keeps giving me these little notes, you know.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: Saying, "Go out and have a good time, here's two bucks."

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Do you see... your business increasing?

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, business has been picking up quite a bit. Um, a lotta people are digging the prices and digging the atmosphere, which is what we wanted to happen. Um, I can see people really being uptight about the idea that it is just two guys who, who formed this record store on a formula. They've got long hair and they don't wear suits and ties. And, uh, they formed a record store and they still pump us.

I don't know, people...can be very naïve. Records cost us a lotta money. Uh, we pay the same prices basically anybody else. We get our records for about between $2.60 and $2.70, and we never charge more than $2.97, unless it's a higher list price album or a double album.

And, I don't know, by and large, I would say very, very few people understand what we're doing. People, as I told you this before, either fall into two categories, the type of people who come into our store. A, you know, uh, the invariable question is, uh, how do you manage to sell your records so cheaply? And they think we're schmucks for not charging them like everybody else does. And, the other type of people who come into the store think maybe this store is really revolutionary and they're trying to do something really right-on. And that's just not true either. The store's at a point where all we're really doing, at this point in time, as much as I hate to admit this, is doing favors for people.

It's hard to do... It's hard to do anything other than that... operating within the context with which we're operating. We're giving away free records, free used records.

Fred Seibert: Right. I noticed that. I picked up [some] last night myself.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. And we're also operating sort of a used record exchange. We get our used records from...

Fred Seibert: Do you buy those from people around the town?

Tom Pomposello: Right. And... there's an outlet in the city where we get it.

Fred Seibert: Is that working out? Do people enjoy that? I know one thing, that people are very upset about from, from the major record stores is that you have to go in and buy a record without listening to it, and the return policy is, is rotten. I know you say you work in a non-return policy.

Tom Pomposello: Well, by non-return policy we mean that when we buy from our distributors, we can't return merchandise, with the exception of defective merchandise. If we were to work on a return policy, we would be paying 20 cents more for our records. It's a privilege which you have to buy.

Fred Seibert: Do you [take] returns ... from kids, if they're defective?

Rob Witter: Kids bring in like open records and say they didn't like it and we can't really take them back, you know-

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: ... because, 'cause then... 'cause all it takes is 10 records to, to pay for that.

Fred Seibert: Right on.

Tom Pomposello: Not because we're mean you-know-whats.

Rob Witter: Yeah, right.

Fred Seibert: Right. I suppose that's why some of the stores have a 50 cent or 75 cent return charge.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. Uh, because a, a store like Goody's does that. And they can get away with it because, uh, they can just return a whole slew of merchandise as defective and nobody would ever look Goody's in the eye.

Fred Seibert: Mm-hmm.

Tom Pomposello: That's an interesting thing to talk about later on. How we, we suspect that Goody's is gonna pressure us.

Fred Seibert: Okay. I, I wanted to ask... You said you're here as an alternate form of, of, uh, business. I guess you have to say you cater mostly (laughs) to the young.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. We really sneered when, when that ... phony plastic hippy shop down the street from us, “Hangups,” ran ads in... the stuff that's getting passed off as alternate, you know, alternative newspapers.

Rob Witter: Well, I don't... They, they've expanded into three or four stores. And, uh, I remember when they first opened up, it was, uh, an exciting event around... around the whole area, in fact, 'cause they were the only ones around. And then they started to expand from posters into clothes and...

Tom Pomposello: And exorbitant prices.

Rob Witter: Exactly.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, that's about where it's at. You see, they, they did a, uh, uh... They bought time on [W]NEW-[FM, New York]...

Rob Witter: I know, I've heard it.

Tom Pomposello: ...recently. And the ad went something like, uh... They did it in cooperation with Limbo and something else like that.

Rob Witter: Mm-hmm.

Tom Pomposello: And the ad went, "A new kind of capitalism based on, uh, cooperation, not competition." We really sneered and laughed at that and thought it was really startling. But when it comes right down to it, that's what we are more or less. It's very, very hard to say that we're a new kind of alternative institution. We like to think of ourselves like that, but we're really not.

Fred Seibert: For the area, you are.

Tom Pomposello: Well, that's because our prices are so cheap, but big deal. See, what's really happening, um, I pay the same price for records, and maybe even more, say, than a place like Goody's because I don't have their buying potential. We pay the same price and we make all this money, the, you know, the $2.60 we make or the $2.97 we charge on a record, we see maybe 37 cents of it. You know? Which a good percentage goes to overhead.

Fred Seibert: Uh-huh.

Tom Pomposello: Um, the other $2.60 goes, you know, to make Capitol Records, and Columbia Records, and RCA Records rich. You know, got to keep the war rolling along.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Um, well, anyway, do you see that you're gonna do anything with it? Uh... have you bothered the other record stores? Have they said anything? Very nearby there's a, a big Huntington record institution, as far the people are [concerned], you know, they bring all their stereos there to be fixed and they buy their records and ...the store never has the records you want, and...

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: They do charge a little less than Sam Goody now.

Rob Witter: Yeah, well, we got visited by them.

Fred Seibert: Really?

Rob Witter: Yeah. One night. They didn't tell us who they were, but they came in like, and they pointed to a record that like nobody who was like 55 would know about.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, it was the, the new Traffic album.

Rob Witter: Yeah. Yeah, it was, "Is this the new Traffic?" You know.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: And it floored us, you know. There [were] a lotta people in the store, and everybody was kind of looking at them anyway.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. A funny thing is, he bought it from us for $3.57.

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: It obviously wasn't for him. He could just go sell it in the store the next day for $4.89.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: (laughs) Still make $1.40.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Um, have they said anything to you though? I mean, officially.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, the day we opened we contrived all these letters from all the record stores in the area, uh, you know, letters of resignation.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello:

Yeah. We wrote... Well, we forged one letter from this store. You tell him the letter, 'cause you made it up.

Rob Witter: You made that up.

Tom Pomposello: Oh, okay. Well, anyway, it said, the letter said, "Dear Kropotkin, we give in. Good luck in business, and then we signed it, uh, forged the signature. So if they're listening, they can get us on libel. Um...

Fred Seibert: Well, didn't they see it when they went in the store?

Tom Pomposello: They saw it.

Rob Witter: ...and then...Yeah, the old lady walked out. She was laughing, 'cause I was sitting on the steps, and...

Fred Seibert: But they haven't said anything besides...

Rob Witter: No.

Fred Seibert: And you say you foresee Goody's pressuring you, have they?

Tom Pomposello: Uh, we haven't, we haven't had any pressure yet.

Rob Witter: I think somebody visited us from there.

Tom Pomposello: Oh, that's, yeah, that’s [right].

Rob Witter: This guy drove up in a Cadillac or something. One time. This is just one. You know, he walked across the street, looked in. There's nobody in there and he laughed, walked back to his Cadillac and drove away. You know... (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: We've been very fortunate, I think, all the times we've gotten visits there've been like around 30 people in the store, so it's looked really good.

Rob Witter: Well, it's good.

Tom Pomposello: But you see, Goody's is such a big outfit, um, that what I could see happening, um... Maybe I'm really projecting this and building it up to a point where, um, you know, I'm ego-tripping and thinking how important we are, you know, it's just not true. I think we could, we could do maybe $3-4,000 worth of business a week and not dent what Goody's doing.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: Um, all they've gotta do probably is say the word and exert a little bit of pressure on our distributors and, uh, we stop getting the albums we want when we want them.

Fred Seibert: Do you think that will happen?

Tom Pomposello: Um, it's really hard to say. I really don't know. See... I read the article that you were talking about earlier too, in Rolling Stone. As a matter of fact, that, that article did influence us in many respects. Not the article as much as the people, because I'd heard about this before I read it in Rolling Stone.

Fred Seibert: Mm-hmm.

Tom Pomposello: Um, it's really hard to say, because nobody out here on the island has tried what we've tried. I suspect that a lotta other people will, because... a lotta times we do give the impression in the store that we're doing really well, because it looks like there's a lotta people and a lotta people buying records. But I mean, you gotta sell... We've gotta sell three albums to make a dollar.

Fred Seibert: And like you said, it goes to overhead. And [has] your landlord said anything?

Tom Pomposello: No, not at all.

Rob Witter: He hasn't... he just-

Tom Pomposello: We're after him to put a bathroom in.

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Has most of your stuff been from kids in the immediate area, or do you get them from other parts of the town?

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, we-

Fred Seibert: Huntington Township is very large.

Tom Pomposello: Right. Mainly from Huntington, although there are still people in Huntington who don't know about us.

Fred Seibert: True.

Tom Pomposello: What a shame. And-

Fred Seibert: Well, what, you've been open six weeks now?

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Give yourself a chance. I mean, you know, you're getting-

Tom Pomposello: We did have a kid hitch in from... He hitched in from Flushing [Queens, NY] with an order that he took from his friends for about 20 records.

Fred Seibert: How long ago was that?

Tom Pomposello: Oh, about two weeks ago. But, he heard about it from a relative who was in Huntington. So I mean, the word just hasn't reached Flushing. Well, it will...

Rob Witter: Another guy from Syosset [Long Island, NY] too. Another guy from Syosset came down to get some.

Fred Seibert: Are you gonna do any... advertising?

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, we've done some advertising.

Rob Witter: Yeah, we had one in the [Long Island] PennySaver just recently.

Tom Pomposello: Mm-hmm.

Rob Witter: And we really haven't seen the effects of it yet, you know, business hasn't increased or anything.

Tom Pomposello: Advertising is expensive as hell.

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Tom Pomposello: That's what the problem is. And we've depended mainly in the past on... our flyers, our groovy little flyers and word of mouth.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: And it's been pretty effective, but, um, there's no question about it, we've gotta get some kinda advertising out, because people have gotta know about us, and we've gotta increase our volume a bit if we're gonna stay in business.

Rob Witter: Mm-hmm.

Tom Pomposello: Uh, we can we can live on $50 a week. It's not, it's not as hard as you might expect. We both have cheap apartments.

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Tom Pomposello: And, uh, food is expensive.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: Especially with a baby, but we're making it. We'll do it.

Fred Seibert: Um, okay. Think you'll put anybody else outta business?

Tom Pomposello: No.

Rob Witter: No, definitely.

Fred Seibert: Definitely not?

Tom Pomposello: I know we've seriously dented the business of that other record store that's in town, but it's not... again, it's not primarily a record store. It's primarily a, a stereo...

Rob Witter: TVs.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: What do you see as your ultimate goal that you'll never reach? Putting Sam Goody out of business?

Tom Pomposello: Well-

Rob Witter: Well, that was just, you know. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Yeah.

Rob Witter: Wishful thinking. But like, no, it'd be nice like a lotta kids like, have asked us like about other record stores, and like... You know what I mean? Like they ask us how we set it up and that 'cause they can talk with us. You know what I mean?

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: And so like it would be nice like if say we can't pull maybe from the south shore, so great, 'cause there is... like there's so much potential all over, you know? Like maybe somebody opening up one down there would be nice. You know what I mean? And then if there was, say, a group of us, you know, like who felt the same way.

Fred Seibert: Then maybe you could put some pressure on people.

Rob Witter: Right. Then it would put some pressure on them. But one store and local, in just one local area isn't gonna do anything really, because like, it's like (laughs) so many people, like, and records are so powerful, like, you know, everybody's getting them.

Tom Pomposello: See, we re- we really are not primarily doing this to put anybody out of business, although I wouldn't mind putting anybody out of business because they're robbers and they deserve to be put out of business. Uh, I mean, I really question the legitimacy of a place like Goody's with the, with the buying power, uh, w- where they can buy, uh, you know, 1,000 records that they're sure are gonna go for, for two bucks a copy, maybe not that much, maybe 2.30 a copy, and then selling them for f- you know, for 4.09. I mean, that's really outrageous. And it's not-

Rob Witter: Definitely.

Tom Pomposello: And Goody's isn't just doing it, uh, on, uh, records. They also have a tape department, where they really rack up, on an instrument department, and, uh, tape and stereo equipment.

Fred Seibert: Do you, um, do you see any day where, where there'll ever be enough of you to get together and say something to the record manufacturers?

Tom Pomposello: No. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Never.

Tom Pomposello: Quite frankly, no.

Rob Witter: We'll be out of it by then, probably. (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Uh, we should tell you about the things that go on with, with our, with our distributors. I walked into our distributor one day to pick up some records, and the Capitol Records salesman and the Columbia Records salesman were both there, and they just could not believe it. You know, when we come in, we're like the standing joke at the distributor.

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Cannot see how two guys with long hair can make it in the record business. And, uh, you know, th- they ask us the same questions, "How can you sell them so cheap then? You don't sell accessories. You don't make money on anything else. How do you do it?" And it just blows their mind that we're willing to work 72 hours or 80 hours a week for like $50, because to them, that's failing. (laughs)

Rob Witter: Exactly.

Tom Pomposello: That's bankruptcy to them.

Rob Witter: Exactly. Degenerate hippies, get a haircut.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: You know? Then make it in business.

Fred Seibert: Okay, um, you said you had some things you want to talk about.

Tom Pomposello: I'll prove to you how it's not a liberation record store, but it tries to be. Um, okay, are we a liberation record store? Um, Hayden, in his, h- his book on the trial, which was just published in Ramparts... I don't know why I put a plug in for them, those robbers. Okay, you can leave the plug in. It doesn't matter.

Fred Seibert: Okay.

Tom Pomposello: Um, outlined, um, in, in the last part of his book, the direction that he thinks the left has gotta go, go into right now, and, um, he, he stated four conditions for what a liberated zone or a liberated area, or if you wanna apply it to a liberated store, what would it consist of. So let me give you the four, um, conditions, and you tell me where you think we fit, 'cause I really don't know if we fit any of them.

He said, "First, they will be utopian centers of new cultural experiment. Second, the territories will be internationalist. Cultural experiment without internationalism is privilege. Internationalism without cultural revolution is false consciousness."

Fred Seibert: You could apply there.

Tom Pomposello: Uh, yeah-

Fred Seibert: I mean, if you can apply a record store to internationalism.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, I agree. Um, third, he said that the territories would be centers of constant confrontation. Uh-huh. "Battlefronts inside the mother country." And fourth, he said that, um, they would be centers of survival and self-defense. See, the only thing I- I- I can see us applying to at all would be, um, utopian centers of new cultural experiment. Leave out the utopian, say, centers of new cultural experiment.

Now, you've gotta ask yourself two questions, first of all, as we put in our manifesto, music is an integral part of our culture, and like much of our culture, robber barons have fixed it so that we must pay exorbitant prices for our, you know, for our music. Um, is music really part of our culture? I really question that.

Fred Seibert: You do?

Tom Pomposello: Mm-hmm.

Fred Seibert: Okay. Why do you question? I, I personally think it is.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: I think it's getting to be maybe at this time, at this point in time, an overbearing part of our culture.

Tom Pomposello: Okay. It brings a lot of people together. And, uh, maybe it's radicalized a lotta kids, if not politically, at least musically.

Fred Seibert: Right. Definitely musically.

Tom Pomposello: Okay. However, as we were saying before, um, you know, when I have to pay 2.60 to get an album, and the groups, the heavy rock groups that we're s- we're looking to as our idols and our-

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: ...right-on revolutionary brothers, um, are not boycotting record companies that, um, are, are charging, you know, people 2.60 for the records and then having them j- jack up from there. Maybe that's impractical. We've gotta ask ourselves what we're doing at this store that's so important. Are we wasting our time?

See, we're not in this pri- primarily just to have something to do. This record store wasn't supposed to be an occupation for, for the two of us. Um, for the two of us, it was gonna be more or less a, a front for our politics, and a way to do something revolutionary. This is about the closest we could get. And, uh, what I'm saying is I- I'd hate to see our store stagnate at this point, and I wanna see it take on new directions, but, uh, it can't unless we all get together and do it. And that's what... That was my... you know, w- what I was saying about the artists in the business, who, uh, are also a great... in, in, in a great way responsible for, um, the prices, which are outrageous. There's no question about it. Even 2.97 is outrageous. There's still no question about that.

Fred Seibert: Definitely. Do you want... You were saying something before.

Rob Witter: Yeah, I was jut gonna say like the one example of how, uh, the using the music like it's coming out there as a part of, say, the new culture or something like that, and trying to push it as that is like on the Chicago album they say, "We put all our energies and our forces into the revolution, and all those connected with the revolution." You know what I mean? And (laughs) that's Columbia too, you know, I mean-

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: ... Columbia is at, boy, they know where it's at. You know what I mean? And then they keep, you know... They're not doing it though.

Fred Seibert: Well, so-

Rob Witter: It's ridiculous.

Fred Seibert: Well, Columbia is using it as a- another gimmick to make money.

Rob Witter: It's a hype. It's a hype.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: That's what it is. And they... Everybody, you know, says Chicago is where it's at.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: The, the culture is the most easily exploited thing.

Fred Seibert: Are you looking at your record store, you say, as a front for your politics.

Tom Pomposello: Right.

Fred Seibert: Is that eventual like going in through a social type of, of, uh, upheaval through your politics there? You're not being blatantly political where you're-

Tom Pomposello: Exactly.

Fred Seibert: ... where you've got, uh, signs up in the store, "Kill the pigs."

Rob Witter: It would be nice if we were like a little bit, well, powerful, maybe, a little bit, at least show some signs of power, like in the community, but like everybody goes, "Kropotkin, (laughs) Kropotnik," or something like that. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: Laugh and sneer, you know. Everybody, they say, "No problem. Just let them go." You know what I mean? We'll never go anywhere.

Fred Seibert: Have you gotten anything from, um, from the, uh, "straight world" where, uh, people have come in and say, "Ah, you're gonna go out of business in two weeks," or-

Tom Pomposello: Oh, all the time. Not so much from the, from the straights who come in, because they really don't know what the record business is all about, but from our distributors all the time. It's one of the reasons why we're having such a hard time getting credit extended. More or less, we're operating on a COD basis.

Fred Seibert: Mm-hmm. Can you... or, do you find that you'll be able to afford to do that for long?

Tom Pomposello: Oh, yeah, it's no problem. It's a pain in the neck more than anything else. It's not really a problem.

Rob Witter: It's really hard though. (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: It's just that, uh, you know, you've gotta budget yourself, and, you know, you can't buy records on Saturday, and Saturday is your biggest day, so consequently you've gotta balance your money so that you'll have enough to give a big order for Friday.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: It's a pain in the neck. When in reality you should be able to order... I mean, they even find this hard to extend us this amount of credit, where we can give a big order Friday, pay half of it on Friday and pay the balance on Monday.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: Which I mean, you know, they really wanna be sticklers. I think they would like to see us go out of business. Yeah, our distributor laid it right on the line to us, when I wanted to open an account with us, and he wanted to know more or less what we were doing, 'cause he thought it was pretty strange, again, that young guys with long hair could try and do a big time operation. How he got the impression we were a big time operation I'll never know.

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: But he did lay it right on the line when he said to me, "I'm a businessman, and, uh, I sell a commodity for a certain price, and it gets resold for a certain price. You're cheapening the commodity that I deal in." You know?

Fred Seibert: He really thought that?

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: I don't know, from his point of view, um, he should be very happy. He's getting that much more money from your business, uh, if, if that's what he's looking for.

Tom Pomposello: Uh, the way he looks at it is that we're hurting the entire record business on Long Island.

Rob Witter: Probably because like, as Sam Goody keeps going up, then maybe, like, uh...

Fred Seibert: He can go up.

Rob Witter: He can go up too, or something.

Tom Pomposello: Exactly.

Rob Witter: Right. You know. He can like, instead of making 40 cents on a record, he can make 50 cents...

Fred Seibert: Is he the same distributor that distributes Goody?

Tom Pomposello: No.

Rob Witter: Nah. No. He's not big enough really.

Fred Seibert: Is this the only available guy?

Tom Pomposello: No, we have, we have a number of distributors.

Rob Witter: Yeah. Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Uh-huh. Are any of them more cooperative?

Tom Pomposello: One of them is. One of them is more or less becoming kind of a personal friend to us.

Fred Seibert: This is Tuesday Night at the Movies with Fred Seibert. We're on WKCR-FM radio in New York at 89.9 on your dial. And we've been talking with some people from a liberation record store, Kropotkin, out on Huntington, Long Island.

The article that, that you were talking and I was talking about in Rolling Stone, [the] most important thing they stressed was get a good distributor who is sympathetic.

Tom Pomposello: Impossible.

Rob Witter: Yeah, it's really hard to, because they're all out to really...

Fred Seibert: Is that around here, or...

Rob Witter: Well, we don't know. I mean, really, we don't know how it is elsewhere, but it probably is the same. You know what I mean? Everybody's just out to burn. You know what I mean? They all, you know, they'd like to... Well, they don't really wanna put us out of business, but like, they'd like to turn us into what they are, you know what I mean, and help them make more, and they'll help us make more, or something like that.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: Rob everybody.

Fred Seibert: Right. So you're not really, uh...

Rob Witter: That's the cooperation.

Fred Seibert: ...too optimistic about them?

Rob Witter: No, not too much. No. It'd be nice if like somebody could open up a... Well, it'd be hard, like start maybe from a company, a distributor, and- (laughs)

Fred Seibert: I was, I was gonna say-

Rob Witter: ...don't get along.

Fred Seibert: I was just about to say, can you see some day, like you said, more people open up, then eventually maybe a distributor will open up, a freak distributor, whatever you want to call it.

Rob Witter: It's pretty hard.

Tom Pomposello: It's mostly impossible, because of the tremendous amount of capital involved, and we're trying to get away from tremendous amounts of capital.

Fred Seibert: There's no way, um...

Rob Witter: But look, suppose like the only thing he could do that would be really... that would help, would be only to deal with us, and that would be, you know... (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Well, I said, if, if you opened up... If somebody opens up many, uh... If, if more kids open up stores, say around the island...

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. I would personally like to see more kids do what we did in different areas, certainly not in Huntington. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Um, but I would like to see more people do what we did. I do know that it'll be extremely hard. This sounds terribly immodest, but it is true. If we didn't have the background that we had in the record business we would've never been able to pull it off. We had a few lucky breaks. Um, we also knew how to [open at] the right time and the right place. And also we were very fortunate that we didn't get shafted, although there were many times when people tried to shaft us.

Rob Witter: It'd be hard like, if you were like, say, you worked at Sam Goody's and one of those guys that walks around, and I don't know what color shirt he wears or something like that, and say like then a year later, he would do it, but I imagine that like that he never sees anything except for like records.

Fred Seibert: Yeah.

Rob Witter: And just like watches people. You know what I mean?

Tom Pomposello: And it's not just a matter of knowing records-

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Tom Pomposello: ...and what sells.

Rob Witter: That's like the... That's nothing really. That's like the easiest part. See, you know, you can get like where we are, like we have, uh, Dud's Corner, like you were telling, like stuff that doesn't move.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: We have to get rid of it, because we can't keep anything. We can keep stuff, but it's like somebody'll always come in. You know what I mean? And that'd be nice to get to the point where we can like carry a lotta records and expect like someone to come in at least once a week and maybe ask us for it. You know. People are really stunned like when they ask us like if they have somebody like, uh... Suppose they said Cat Mother's first albums, like that, which isn't selling now, you know. We didn't have it, like we say, "We don't have it." And then, you know, "Take 'em back."

"What."

"Yeah, you don't have it?" And that. It's really...

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: It's really crazy.

Tom Pomposello: All in all, what we're trying to say is that we're very fortunate that we didn't flop.

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Tom Pomposello: And we haven't flopped. By our standards, we're successful. By, uh, our bourgeois establishment standards, we're a flop. We were a flop from the day we opened and we always will be a flop.

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: But by our standards, we're, we're making out fine, and we're very... both of us are very satisfied. Um, I'm not trying to dissuade anybody from doing what we're doing. As, as I said before, I'd like to see a lotta other people do it, because that's what we've gotta do.

Fred Seibert: Sure.

Tom Pomposello: Um, then again, if you're not... if you do consider what we are, an alternative institution, um, if we're not, and we're probably not, then we've got no right doing what we're doing. Like I said, the only way I can envision us is people who are doing people like us a favor. And that's all the legitimizing I need for being in the business that I'm in.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: See, again the concept of whether or not the store is a front for our politics has to be answered in terms of two questions. I mean, are the records that we handle radical? Is there such a thing as radical records?

Fred Seibert: Right. Is there?

Tom Pomposello: See, I don't think there really are. And in addition to that, even if there were, I don't think that we have a right to en- to enforce our taste. That's the reason we handle Grand Funk Railroad and the Iron Butterfly, because there are kids who like them, and, you know, they wouldn't know good music if it bit them on the ass, but they've got a right.

Rob Witter: Thanks, Frank.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: They've got a right to, you know, to buy what they wanna buy. Or else you have to look at the thing from a from a different perspective. Is the store political in the sense that it's cheap, it's a place where you can come in to rap, and it's different. It is different. And it is a place where you can come in to rap. And it is cheap. I don't know if that qualifies as being radical in any sense of the word.

Rob Witter: Well, it can be considered socially radical, I suppose.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Yeah. Right.

Tom Pomposello: Well, I mean, that's what we were talking about before in terms, again, here I go, with the base structure and superstructure thing. That we have to get into a new form of social lifestyle before we can effect any other kind of real meaningful social change. I'm not convinced that that's true.

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Ah, but, uh, but I mean, that's, that's...

Rob Witter: Might as well try it.

Tom Pomposello: Right.

Fred Seibert: Uh, just one, just one thing. Down the street from you is another...

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: ... hippie head shop.

Tom Pomposello: Right.

Fred Seibert: For Huntington. Uh, yeah, I, I've been in there a few times, and the atmosphere is, is one of extreme unfriendliness, I found.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. And the prices are extremely high.

Fred Seibert: The prices are extremely high.

Tom Pomposello: Tie-dye shirts for $5.

Tom Pomposello: Unless you walk in there with a certain length hair, a certain uniform, hip uniform on, you're... you will get, uh, completely shunned by the management. Uh, do you see it though, even though that things like this are happening all over...

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: ... those type of boutiques are, are opening up all over the place.

Tom Pomposello: Right.

Fred Seibert: And, you know, they're not doing much business in a lot of places.

Tom Pomposello: Right. We've already spoken to people who are interested in doing the type of luncheonette. I mean, that's really important. I've tried going into restaurants with my wife and because my hair is long and I don't wear a tie, I've had tremendous hassles. I mean, that's, that's almost a given for anybody with long hair in this country.

Fred Seibert: Sure.

Tom Pomposello: I think that, again, this idea of building up alternative institutions where we can go. I mean, have liberated crash pads, have anything, where we can go, have a place for us, an outlet for us, is, is extremely important. And, um, that's why we're doing what we're doing, in summation. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Well, carrying albums now. You carry one single. Are you gonna see yourself getting into Top 40?

Tom Pomposello: Um, I don't know. It's a pain-

Rob Witter: Oh, yeah.

Tom Pomposello: It's a pain in the neck. We hate it because we make three cents on it.

Rob Witter: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: Well, I hated them long before that. I've never bought one, you know.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: In my life. (laughs) And I don't intend to.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, the only 45 we've seen fit to handle is, you know, the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young thing, “Ohio.”

Fred Seibert: Is that because of its politics?

Tom Pomposello: Exactly.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: Well. And sold well. It means like...

Fred Seibert: Say something about your manifesto too. Or did you?

Rob Witter: We kinda said it a little bit. He was saying it. He recited it. He had it memorized.

Tom Pomposello: It took me 10 minutes to write and 10 minutes to memorize.

Rob Witter: We always like... And if we write anything... Whenever he writes anything, he goes, "Well, make it just short." And it ends up to be like a page and a half or something.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: (laughs) And we always have to edit it.

Tom Pomposello: Right. Our ad in PennySaver, which was supposed to be short and to the point. 54 words. (laughs)

Rob Witter: The lady was nice, she goes... I go, "Is this okay?"

And she goes, "Yeah, but there's a lotta words there." (laughs)

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: It cost us. Next time we'll just put, "Records", or something like that, and do it really cheap.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: Took us 15 minutes.

Tom Pomposello: Edit that out. Boy, did that sound dumb. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: What, about your page and a half?

Tom Pomposello: Um... You'll probably leave the stuff in where we say, "Edit that out," huh?

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Fred Seibert: I don't know, it depends. Do you see the store expanding?

Rob Witter: Well, now the store's starting to become called Kropotkin East. (laughs) A lot of people are thinking, you know, getting on that name, like, so like make believe we have a Kropotkin West or something like that.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Are you doing that on purpose?

Rob Witter: Well, it's kinda just... you know.

Tom Pomposello: It just happened.

Rob Witter: Just, yeah, it just happened.

Tom Pomposello: I had nothing to do with it.

Rob Witter: We were kidding around like that, you know, you know, follow the Fillmore, you know, [Bill] Graham ...

Fred Seibert: A lot of poster shops have done that around the island, and discotheques. You know, they're starting to put one in Southampton.

Tom Pomposello: Yes. I don't think we'll ever call ourselves Kropotkin East or Kropotkin West.

Rob Witter: No.

Fred Seibert: Anyway, you were saying you wanna improve the store.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, well, our profits... Uh, I'd like to make a little bit more money to live a little bit better. I really hate living in my apartment.

Fred Seibert: Well, $30 a week is even, uh, for a non-capitalist, uh, is a, is a rough thing to work on in, in the way things are.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Especially around Huntington, I know that the prices in some places are really exorbitant because there are other robber barons besides the record stores.

Tom Pomposello: I should like very much to make a dollar an hour. (laughs)

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: In other words, make $72 a week.

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: I would like that feeling-

Rob Witter: That'd be nice.

Tom Pomposello: That might happen. We- we're reinvesting quite a bit of our money in- into improving the store. The first day we opened, we had about 110 different albums and half a box of backup stock. (laughs)

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Now we have about, oh, about 150 different albums.

Rob Witter: Well, we've had, at some time or another, over 200 different albums though.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: And like within a week we had gotten up to almost 150, but we still didn't have enough stock, and they went out really fast. Now we're like... What we're building on now is like keeping 10 or 15 of one that's moving fast, and say, something that's even moving slow, at least have a good backup on it so that we can, you know...

Instead of like... At first, we were saying, well, we'll try to get as many records as we can." But like, that was no good because, like, you'd run out of them too fast, so now we just, like, try to, say, stay level at maybe 150 for awhile.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. Again, here's the advantage of having credit.

Rob Witter: Yeah. Right.

Tom Pomposello: It's very hard building up a backup stock without credit, burp.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Uh, at one time or another you only keep 150, you say, different albums, because those are the ones that sell.

Tom Pomposello: Right. We'd like to get a bid in with back stock. Um, we take on the average of three special orders a day, which means that most of the kids that come into the store get satiated. (laughs) Uh, you know, 150 albums is really... covers that scope as far as rock music goes, contemporary rock music of what people want. And we have just about everything that's important.

Rob Witter: 'Cause they cover right now, like I mean, we don't have, like, uh, 'cause those 150 don't include like “Freewheelin',” Bob Dylan, and stuff like that, you know.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: We have like stuff that's been out for a few months, or stuff that even if it's been out for more than that has... is still selling very, you know, big.

Fred Seibert: “Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Rob Witter: Yeah, well, we don't even have that, because...

Tom Pomposello: You didn't have to say that, did you?

Fred Seibert: Me?

Tom Pomposello: No, him. Can I say something that should be interjected?

Fred Seibert: Sure.

Tom Pomposello: In one spot or another. There's a store out in Hicksville which sells... which is star- starting to get a reputation for itself, which sells any two albums, regardless of the list price for $5.98.

Fred Seibert: I've heard about that place.

Tom Pomposello: Yes.

Fred Seibert: Someone said, "Kropotkin isn't so great, look at this store." I forgot what it's called.

Tom Pomposello: Right. Right. Okay.

Fred Seibert: Tell me about that.

Tom Pomposello: Okay. We should tell you the scoop on that. In the record business there is what's known as overflow stock. When a record reaches a point where there are too many issued, even though it was an extremely big seller, uh, a good example of this would be some of the Creedence albums for example, which were big sellers, but there still were too many.

Rob Witter: Air Force. (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Or Ginger Baker, Air Force. Another good example. Where there were too much... where there were too many issued. Um, they wind up in warehouse outlets somewhere in the city on 8th Avenue. (laughs)

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: And you can go in there and buy almost any record for $2.00 brand new, and it's what's known as overflow merchandise, and you buy it from a jobber. Therefore, they have a policy of selling you any two records for six bucks, in other words, those two records cost them four bucks. And they're still making, uh, a third.

And they don't have, and they don't have new, new merchandise. For example, you couldn't go in there and find, uh, you know, the new Traffic album or the new Creedence album. You might find it three or four months later. When they say any two albums, what they mean is any two albums you can find, stock. I mean, they're making more than 37 cents on a record.

Fred Seibert: Right.

Tom Pomposello: I had to throw that in there because people are getting the impression that if a big-time capitalist store in the mall can sell them so cheaply then what's so revolutionary about Kropotkin, when, you know, they're selling them for the same price? In addition, we don't demand that you buy two records...to get the $2.97 price.

Fred Seibert: Right. How much do you sell a day? How many records? Or a week, say?

Rob Witter: A week, we're up to around 500, and we kinda leveled off for awhile because our advertising hasn't really gotten around. And it's been about 500 for-

Tom Pomposello:Yeah. I would say our mean average, we do about 100 a day, maybe not quite.

Rob Witter: That's almost it.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: Do you see ... within three or four months, five months, going to 150 a day or 200 a day?

Tom Pomposello: Maybe when college opens and some college newspaper does a story on us, it might help.

Rob Witter: Now, what is... We're getting into some underground magazines too, like the four stores in, uh, the Clog Shop, the Pinata Party, the Grape Nuts, like...

Tom Pomposello: (laughs)

Rob Witter: Or, um, did this thing where, in the Long Island Duck, we took out a full page ad, like, and it's, it's almost like the same thing that Limbo and Hangups did, you know.

Tom Pomposello: That's right.

Rob Witter: Cooperation or something like that, you know. (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Snicker, snicker, snicker.

Rob Witter: Cooperate with them, you know. You know, it's not that, but I mean, we all are friends and everything, but- (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Well, it's, it's a good way, um... Are you gonna start trying to do that, say, in the bigger magazines, Rolling Stone?

Rob Witter: Um, that's really... Advertising is really expensive. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Right. Well, if you ever move up to $150 a day, maybe (laughs) maybe you can try it out.

Rob Witter: Yeah. Well, we would have to really be... We'd have to at least double what we are now to do anything a little bit more important. But we're getting advertising done. We'll be in like, maybe like five, say five underground... at least five so-called underground newspapers, whether they're underground or not. You know what I mean? Like the Free Press. These are all high school, like Long Island Duck.

Fred Seibert: Yeah.

Rob Witter: Dog Breath. You know. Velvet Underground. PennySaver.

Fred Seibert: (laughs) Big underground. Your records,you have 150, and with the exception of three special orders a day, you know, that people are more or less satiated.

Tom Pomposello: That's the precise word I used.

Fred Seibert: Right. Uh, do you see the... your... any part of your revolutionary, uh, mood in there to educate them?

Tom Pomposello: Yeah, we try. Yeah.

Fred Seibert: As far as music goes?

Tom Pomposello: We try to rap as much as we possibly can. One of the big things we've taken to rapping about is drugs.

Fred Seibert: Why don't you say something about that.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah. For example, the... just simply the foolish attitudes that people in our area have toward drugs. We've had kids come into our store and say, "Ah, I'm really tripping, man. Uh, blank, blank, just gave me two tabs and I'm really flying."

Rob Witter: (laughs) You can find him at this address and everything. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: You know, and drop, and drop names.

Rob Witter: And still there's 30 people in the store, you know.

Fred Seibert: Oh, right. (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: Our classic story is the one guy who, who was in there browsing for awhile and he said, "Um, I have to leave now, but can I leave a note for my friend, uh, when he's gonna come here? Can I leave it up on your bulletin board?"

And I said, "Sure."

And so he writes the note and it says, "Eric, I got your mescaline from Tony in the village."

Rob Witter: (laughs)

Tom Pomposello: "You can pick it up at my house if you want. Here's my phone number for when you can call me."

See, the atmosphere in Huntington right now is extremely relaxed, um, on the part of the administration toward drugs. But that's the way it always is. They let it get relaxed and then, boom, you know, suddenly people-

Fred Seibert: Well, it's kind of ridiculous is what the attitude is on drugs.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: What is... Well, so I, I assume your, your drug raps have been sort of anti-drug raps.

Tom Pomposello: Well, they haven't been anti-drug raps, all like... all we've been telling people is be cautious and don't be fools.

Fred Seibert: What have they been saying?

Tom Pomposello: A lotta people, a lotta people dig it, and they say, "You're absolutely right." But it's like water off a duck's back. You know? It, it really... It's... There are some people who've been affected by it, I'm sure. And there are many people who haven't. Uh, we were thinking of closing the store down for a couple hours one night just to do a drug forum, um, which I think we're going to, going to definitely do, because there's a lotta foolish attitudes going on.

Rob Witter: They're too carefree. You know what I mean?

Tom Pomposello: Definitely.

Rob Witter: They're always doing it like in... and like plenty of guys even have come up to us and say... said, uh, like, just... We're standing back of the counter and they go, "You got any grass?" You know? "You got some grass?" Something like that. And like, that's... (laughs)

Fred Seibert: (laughs)

Rob Witter: For us to even, you know, just... it's just so stupid for us to even say anything, we just go... you know, what can we do? You know? (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Right.

Rob Witter: Like so many kids, like, you know, they come and they walk over in the corner and they start talking and that, you know, and, uh, they call you up on the phone and everything that... (laughs) It's really funny. And they tell you, you know, "I'm tripping like in, uh... I got it from this guy." And it's really... It's just, you know, it's foolish, as he says. And like they're gonna get busted. A lotta them have been busted already twice. You know what I mean? And they just, you know, continue doing it.

Fred Seibert: Do you see any type of anything like that happening, fix-ups by people around, that are... that would try to get you out of business because they, they think that you're a bad influence on, on their kids in the community?

Tom Pomposello: Um, I don't know. Huntington is starting to, starting to emerge as kind of a liberal community, kind of. More of a... Not a liberal community as much as a... as a community that tolerates. It's one of the only towns in Suffolk County where you don't get double-takes if you have long hair.

Fred Seibert: Yeah. That's true. But, um, on-

Tom Pomposello: I don't really think that many of the parents who you would normally expect to react that we're a really corrupt place are reacting that way. More or less they're starting to think of, uh... I think many of them are relating to us in a positive respect. We get a lotta mothers coming in here to buy birthday presents.

Fred Seibert: Right, and on the same end though, there are people in, in the town that think that... that say if they heard this, would be very upset and try to get you out of business the next day.

Tom Pomposello: That's right. I'm counting on them not hearing it.

Fred Seibert: I've been reading they've been having problems on multimedia shows held at one of the schools.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: They had the song, “Superstar” in it.

Tom Pomposello: I know. We supplied it.

Fred Seibert: They are not being called communist. Right.

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.

Fred Seibert: They're calling it communists, um, anti-religious and things. Do you... You don't think anything like that'll happen?

Tom Pomposello: Um, last night, I was rapping with a cop. (laughs)

Fred Seibert: Right. You told me. So, well...

Tom Pomposello: Um, he said, uh, "Well, we like to see, uh..." And he just stopped right there. So I really don't know what his attitude was. Maybe he was trying to, uh, to rap to us just for the heck of rapping, because he was pounding his beat and had nothing better to do.

We haven't experienced any pressure yet. And it's impossible to say whether, uh, we're going to experience any pressure. I kinda suspect we will, but, uh-

Rob Witter: Originally, he fell for it.

Tom Pomposello: If we win the... If we win the support of the kids, um, and the kids let their parents know that, "Heck, they're not doing anything down there except selling records cheaply." Because that's what it appears to what we're doing. And in actuality, that's what we are doing.

Rob Witter: Right now. Yeah. (laughs) That's all we do.

Fred Seibert: Okay. You were saying you wanted to hold this drug forum maybe, that you'd hold, you know, a couple of hours at night. Do you see yourselves trying to develop that kind of community within the kids? Some sort of community. One of the things I think that-

Tom Pomposello: Yeah.