The Military and Geopolitical News Monitor for the OSIMINT page

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Draken International acquires twelve South African Atlas Cheetah fighter aircraft

Lakeland, FL (December 11, 2017) - Draken International, a global leader in advanced adversary air services, has announced the acquisition of twelve South African Atlas Cheetah fighter aircraft, reinforcing the company’s focus on providing advanced capabilities to its clients. As the demand for increased capacity of adversary resources continues to soar throughout the Department of Defense (DoD) and globally, Draken’s new Cheetah jets will provide the USAF, USN, and USMC an advanced radar-equipped supersonic platform to train against.

Viewed as a major achievement for the South African Defense Industry, Denel Aeronautics, the aircraft design authority, remains committed to the expeditious transfer and complete regeneration of nine Cheetah C models (single-seat) and three D models (two-seaters) to ensure Draken’s fleet achieves operational status by mid-2018. In addition to the procurement of the Cheetah fleet, Draken and Denel have created a partnership that will include follow-on service support to help ensure performance reliability. Draken is currently the only commercial air services provider supporting the DoD with 4th generation capabilities. The company’s A-4 Skyhawks equipped with APG-66 radars, and L-159 Honey Badgers with GRIFO-L radars, have proven to be highly effective adversaries for the USAF, ANG, USMC and international partners. Supplementing the Draken fleet with these 4th generation Cheetahs will offer customers an extremely capable yet highly cost-effective platform. The twelve Cheetahs are complemented by Draken’s recent acquisition of 22 modernized radar-equipped Spanish Mirage F1Ms.

Draken’s core competency is its ability to acquire and operate affordable, supportable, credible and capable fighter aircraft. Draken also remains dedicated to tracking and evaluating aircraft globally with proven success operating fleets of aircraft that include the A-4 Skyhawk, L-159 Honey Badger and Aermacchi MB-339. With both the newly acquired Cheetahs and the Mirage F1Ms modernized in the 1990’s, these highly capable platforms were selected over early model F-16s and non-modernized Mirage F1s based upon their true 4th generation capabilities. Developed as a variant of the Mirage III, the Mach 2.2 Cheetahs are equipped with radars, radar warning receivers, and other advanced avionics. The Cheetahs also have an average of 500 hours on each airframe and are considerably younger than many of the F-16’s, F-15’s and F/A-18s they will challenge in the Red Air capacity.

Sean Gustafson, VP of Business Development at Draken stated, “Our customers within the USAF, USN, and USMC have asked Draken to evolve our capabilities in order to simulate the 4th generation adversaries the United States may have to face in the future. While our extensive fleet of A-4K Skyhawk and L-159 Honey Badgers are modernized with sophisticated radars and sensor suites, it’s a challenge to deliver modern enemy capabilities at a low price point, which is a fundamental requirement for our industry. However, with the recent purchase of our low-time Spanish Mirage F1M’s and our South African Cheetahs, we now have the ability to deliver supersonic, modernized, and truly threat representative 4th generation capabilities at a very affordable price point.”

The demand for capable adversary aircraft within the DoD continues to exceed expectations and Draken is working diligently to meet that demand. Along with the procurement of 22 modernized Mirage F1Ms and F1Bs, the Cheetah will be offered for various contracts within the USAF, USN, USMC, and US-partnered militaries. Draken remains a pioneer in the ADAIR service industry providing essential training to all military services. As Draken’s current contracts evolve to handle additional requirements, so will our ability to provide enhanced support for combat readiness training.

Gustafson further stated, “As the leader in the commercial air service industry, not only by the number of operational aircraft, but by the number of contracts and total annual flight hours, Draken will continue to raise the bar for all to strive for. Capacity and capability are the dominant themes for the ADAIR business driven by the contractual requirements of our customers. As the only provider of Red Air for the USAF, including the weapons school and Red Flag, Draken is committed to delivering extensive capacity in order to manage a majority of the enormous ADAIR demand throughout the entire DoD. This is why we have purchased the A-4, L-159, Mirage F1M, and now the Cheetah, the first truly 4th generation platform in the industry.”

Draken is committed to providing US and allied fighter pilots the most advanced live air training solution by investing and expanding the largest, most advanced fleet of tactical fighter aircraft in the industry. Their entire organization, including ownership, management, pilots, and maintenance personnel will continue to provide the best service available globally.

About Draken International

Draken International is the world’s largest operator of ex-military aircraft. The company is based out of Lakeland Linder Regional Airport in Lakeland, FL. The organization sets a new standard in airborne adversary support, flight training, threat simulation, electronic warfare support, aerial refueling, research, testing, as well as other missions uniquely suited to their fleet of aircraft. With over 100 tactical fighter aircraft incorporating modern 4th generation capabilities, the company is uniquely positioned to answer the growing global demand for commercial air services. Draken employs world class, military trained fighter pilots including USAF Weapons School Instructors, Fighter Weapons School Graduates, TOP GUN Instructors, Air Liaison Officers, and FAC-A Instructors. For additional information, visit www.drakenintl.com.

http://www.drakenintl.com/blog/blog/news-and-press/draken-international-adds-twelve-atlas-cheetahs-to-their-radar-equipped-supersonic-fleet

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sri Lanka formally hands over Hambantota port on 99-year lease to China

Beijing to hold 70 p.c. stake in the strategic port; Opposition and trade unions dub the $1.1 billion deal as “a sellout.”

Sri Lanka on Saturday formally handed over the strategic southern port of Hambantota to China on a 99-year lease, in a deal dubbed by the opposition and trade unions as “a sell-out.”

The government’s grant of large tax concessions to Chinese firms have also been questioned by the Opposition.

Two Chinese firms — Hambantota International Port Group (HIPG) and Hambantota International Port Services (HIPS) — managed by the China Merchants Port Holdings Company (CMPort) and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority will own the port and the investment zone around it, officials said.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe during a visit to China in April had agreed to swap equity in Chinese infrastructure projects launched by former president Mahinda Rajapaksa in his home district.

Sri Lanka owed China $8 billion, then Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake had said last year.

‘To be major port in Indian Ocean’

“With this agreement we have started to pay back the loans. Hambantota will be converted to a major port in the Indian Ocean,” Mr. Wickremesinghe said while addressing the handing over ceremony held in parliament.

“There will be an economic zone and industrialisation in the area which will lead to economic development and promote tourism,” the Prime Minister said.

The Sri Lankan government had signed a $1.1 billion deal in July to sell a 70 per cent stake in the Hambantota port to China.

Sri Lanka received $300 million as the initial payment under the 99-year lease agreement.

The port, overlooking the Indian Ocean, is expected to play a key role in China’s Belt and Road initiative, which will link ports and roads between China and Europe.

'Will not be used as a military base'

In order to allay India’s security concerns over the Chinese navy’s presence in Sri Lanka, Mr. Wickremesinghe had earlier ruled out the possibility of the strategic port being used as a “military base” by any foreign country.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/sri-lanka-formally-hands-over-hambantota-port-on-99-year-lease-to-china/article21380382.ece/amp/?__twitter_impression=true

1 note

·

View note

Text

China ‘ready to mass produce’ strike-capable CH-5 UAV, says report

The first mass-production model of the CH-5 UAV conducted its first test flight from an airfield in China's northern Hebei Province on 14 July. Source: Xinhua

China has announced that it is ready to mass produce the Cai Hong 5 (Rainbow 5, or CH-5) strike-capable unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that was unveiled at Airshow China in November 2016, according to a 15 July report by the China Daily newspaper.

The announcement was made shortly after the first mass-production model of the CH-5 conducted its first flight from an airfield in China’s northern Hebei Province.

Ou Zhongming, project manager of the CH series at the Beijing-based China Academy of Aerospace Aerodynamics – the country's largest exporter of military UAVs – was quoted by the state-owned newspaper as saying that several countries, including current users of other CH models and new clients, are in talks with the academy to procure the CH-5.

"Today's [14 July] flight means the CH-5's design has been finalised and we are ready to mass produce it," he was quoted as saying, refusing to name potential buyers.

Shi Wen, chief designer of the CH series, told the paper that the CH-5 outperforms all of its Chinese-made counterparts when it comes to operational endurance and payload capacity. “The UAV is as good as the US-made General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper: a hunter-killer drone often deemed by Western analysts as the best of its kind,” he claimed.

The prototype CH-5 was first flown in August 2015. Built by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) the UAV has a wingspan of 21 m, can stay in the air for a maximum of 60 hours, and has a service ceiling of 7,000 m, according to specifications briefed to Jane's by a senior CASC official in November 2016.

0 notes

Text

Thailand plans joint arms factory with China

Thailand’s defense technology agency plans to set up a joint center with China to produce and maintain military equipment in the latest sign of the strengthening security relationship since a 2014 coup.

The plans to establish the facility - and discussions on a Chinese naval center to serve submarines Thailand ordered this year - point to a growing Chinese security presence in the oldest U.S. ally in the region as elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

The Thai government’s Defence Technology Institute (DTI) will set up Thailand’s first commercial joint defense facility with China in the northeastern province of Khon Kaen in July, a defense ministry spokesman said.

It will be responsible for assembly, production and maintenance of Chinese land weapon systems for the Thai army.

“All our production will be for domestic official usage,” defense ministry spokesman Kongcheep Tantravanich told Reuters, adding that it could become an assembly and maintenance center for all states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Specific details, he said, were subject to further discussions between the ministry and China North Industries Corporation (NORINCO) - which makes tanks and weapons among other heavy equipment.

NORINCO did not respond immediately to an emailed request for comment. Its website describes it as “a pioneer and leader of Chinese military trade, and an important team to implement China’s Going Global strategy”.

Kongcheep said the Chinese would provide training and technology transfer, but details of any Chinese personnel in Khon Kaen were among things being discussed.

The Chinese Defense Ministry did not respond when contacted by Reuters for comment.

BIG PURCHASES

China has become an increasingly important source of weapons for Thailand, particularly since the United States and Western countries downgraded ties after the army seized power in 2014.

Major purchases since 2015 include orders for 49 Chinese tanks and 34 armored vehicles worth over $320 million - much more than the army has bought from other countries, although it also ordered helicopters from both Russia and the United States.

The biggest Chinese purchase is the Royal Thai Navy’s order for three submarines at a cost of over $1 billion.

Thai and Chinese armies and air forces have begun joint exercises, complementing Thailand’s continuing drills with the U.S. forces. On the civilian front, Thailand and China plan development of a high-speed rail link as part of Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative.

Relations with the United States are warming again too, however, particularly since new U.S. President Donald Trump hosted junta leader Prayuth Chan-ocha at the White House.

The joint weapons manufacturing center in Khon Kaen - apparently similar to one in Pakistan - could complement China’s growing military presence in neighboring Cambodia, said Paul Chambers, who has researched Thai military and regional security.

“It opens the door for the potential of growing Chinese military influence in mainland Southeast Asia,” said Chambers, of Naresuan University in the northern Thai province of Phitsanulok.

New legislation taking effect next year will allow Thailand’s Defence Technology Institute to operate on a commercial basis, but it will remain entirely under government ownership.

Thailand’s Defence Ministry said the government was also holding preliminary discussions with Ukraine, Russia and South Africa about joint defense manufacturing facilities, similar to the deal with China.

Reporting by Panu Wongcha-um; Additional reporting by Ben Blanchard in BEIJING; Editing by Amy Sawitta Lefevre and Matthew Tostevin

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-defence/thailand-plans-joint-arms-factory-with-china-idUSKBN1DG0U4

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Game of Drones: U.S. poised to boost unmanned aircraft exports

The Trump administration is nearing completion of new “Buy American” rules to make it easier to sell U.S.-made military drones overseas and compete against fast-growing Chinese and Israeli rivals, senior U.S. officials said.

While President Donald Trump’s aides work on relaxing domestic regulations on drone sales to select allies, Washington will also seek to renegotiate a 1987 missile-control pact with the aim of loosening international restrictions on U.S. exports of unmanned aircraft, according to government and industry sources.

At home, the U.S. administration is pressing ahead with its revamp of drone export policy under heavy pressure from American manufacturers and in defiance of human rights advocates who warn of the risk of fueling instability in hot spots including the Middle East and South Asia.

The changes, part of a broader effort to overhaul U.S. arms export protocols, could be rolled out by the end of the year under a presidential policy decree, the administration officials told Reuters on condition of anonymity.

The aim is to help U.S. drone makers, pioneers in remote-controlled aircraft that have become a centerpiece of counterterrorism strategy, reassert themselves in the overseas market where China, Israel and others often sell under less-cumbersome restrictions.

Simplified export rules could easily generate thousands of jobs, but it’s too early to be more specific, said Remy Nathan, a lobbyist with the Aerospace Industry Association. The main beneficiaries would be top U.S. drone makers General Atomics, Boeing (BA.N), Northrop Grumman (NOC.N), Textron (TXT.N) and Lockheed Martin (LMT.N).

“This will allow us to get in the game in a way that we’ve never been before,” said one senior U.S. official.

‘BUY AMERICAN’ AGENDA

Regulations are expected to be loosened especially on the sale of unarmed intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance drones, the most sophisticated of which carry high-resolution cameras and laser-guided targeting systems to aid missiles fired from warplanes, naval vessels or ground launchers.

Deliberations have been more complicated, however, on how to alter export rules for missile-equipped drones like the Predator and Reaper. Hunter-killer drones, which have essentially changed the face of modern warfare, are increasingly in demand and U.S. models considered the most advanced.

The push is not only part of Trump‘s “Buy American” agenda to boost U.S. business abroad but also reflects a more export-friendly approach to weapons sales that the administration sees as a way to wield influence with foreign partners, the senior official said.

Under a draft of the new rules, a classified list of countries numbering in double digits would be given more of a fast-track treatment for military drone purchases, a second senior official said. The favored group would include some of Washington’s closest NATO allies and partners in the "Five Eyes" intelligence alliance: Britain, Australia, Canada and New Zealand, according to the industry source.

Rachel Stohl, director of the conventional defense program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said if U.S. drone export rules become too lenient, they could give more governments with poor human rights records the means to “target their own civilians.”

Trump’s predecessor, President Barack Obama, revised the policy for military drone exports in 2015. But U.S. manufacturers complained it was still too restrictive compared with main competitors China and Israel.

U.S. drone makers are vying for a larger share of the global military drone market. Even before the coming changes, the Teal Group, a market research firm, has forecast sales will rise from $2.8 billion in 2016 to $9.4 billion in 2025.

Linden Blue, CEO of privately held General Atomics, the U.S. leader in military drones, visited the White House recently to lobby for his industry, a person familiar with the discussions said.

Among the U.S. changes will be a formal reinterpretation of the “presumption of denial”, a longstanding obstacle to most military drones sales, that would make it easier and faster to secure approval, the officials said.

Britain, and only recently Italy, are the only countries that had been allowed to buy armed U.S. drones.

A long-delayed $2 billion sale to India of General Atomics’ Guardian surveillance drones finally secured U.S. approval in June. But New Delhi’s request for armed drones has stalled.

A major hurdle to expanded sales of the most powerful U.S. drones is the Missile Technology Control Regime, or MTCR, a 1987 accord signed by the United States and 34 other countries, which set rules for the sale and purchase of missiles.

It categorizes drones with a range greater than of 185 miles (300 km) and a payload above 1,100 pounds (500 kg) as cruise missiles, requiring extremely tight import/export controls. To gain an international stamp of approval for the relaxed U.S. export rules, U.S. officials want the MTCR renegotiated.

State Department officials attending an annual meeting of the missile-control group in Dublin next week will present a “discussion paper” proposing that sales of drones – which did not exist when the agreement was created – be treated more leniently than the missile technology that the MTCR was designed to regulate, according to a U.S. official and industry sources.

There is no guarantee of a consensus. Russia, which has NATO members along its borders, could resist such changes, the U.S. official said.

CHINA AND ISRAEL

China, which is not an MTCR signatory, has pushed ahead with drone sales to some countries with close ties to Washington, such as Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria, but which have failed to pass U.S. regulatory muster.

Chinese models such as the CH-3 and CH-4 have been compared to the Reaper but are much cheaper. U.S. officials said Beijing sells them with few strings attached.

The Chinese foreign ministry insists it takes a “cautious and responsible attitude” to military drone exports.

Israel, which is outside the MTCR but has pledged to abide by it, competes with U.S. manufacturers on the basis of high-tech standards. But it will not sell to neighbors in the volatile Middle East. Israel sold $525 million worth of drones overseas in 2016, according defense ministry data.

U.S. drone makers and their supporters within the administration contend that other countries are going to proliferate drones, so they should not be left behind.

Additional reporting by Catherine Cadell and Ben Blanchard in Beijing, Dan Williams in Jerusalem; Editing by Chris Sanders and Grant McCool.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trump-effect-drones-exclusive/exclusive-game-of-drones-u-s-poised-to-boost-unmanned-aircraft-exports-idUSKBN1CG0F4

#United States#drone market#drone strikes#public policy#mtcr#cruise missile#china#international trade#israel

1 note

·

View note

Text

Israel to boost G550 surveillance fleet

The Eitam and Shavit of 122 Squadron during Israel's 68th Independence Day flypast

With demand for surveillance aircraft rising in the face of new threats in the Middle East region, Israel's air force is increasing the size of its fleet of special mission-adapted Gulfstream G550 business jets.

The head of the service's aircraft department – who can be identified only as Col H – confirms that an additional special mission asset based on the G550 is under construction. He declines to identify which role the aircraft will conduct once in operational use.

Israel's air force currently uses two variants of the G550: an airborne early warning and control system model named "Eitam", and a "Shavit" version tasked with communications/electronic intelligence-gathering tasks. Flight Fleets Analyzer records the service as having two and three of these types, respectively.

With the current assets aged between 10 and 12 years, the new aircraft will be equipped with upgraded systems offering enhanced performance.

The "Nachshon" squadron, which operates both variants of the modified business jets, is one of the Israeli air force's busiest units, and the new addition will allow it to better respond to operational requirements.

https://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/israel-to-boost-g550-surveillance-fleet-441814/

04OCT17

0 notes

Text

FBO: Triton Mission Control Facility (UAE)

The US Navy’s plan calls for hangar space to house a total of four drones, plus equipment to control the aircraft and new taxiways to link the site to the base’s existing runways, according to the posting on FedBizOpps, the government’s main contracting website.

The U.S. Air Force will construct this infrastructure in an area already used to park tanker aircraft.

Solicitation Number: N6945016R1103

Notice Type: Award

Contract Award Date:September 27, 2016

Contract Award Number: N6945016C1103

Contract Award Dollar Amount:$8,501,000

Contract Line Item Number: 0001

Contractor Awardee:Whitesell-Green, Inc. (DUNS 053002721)

3881 North Palafox Street, Pensacola Florida 32505

0 notes

Text

Truths Mapped Out: India Cannot Afford To Have China Controlling Doklam Plateau

As I write this, India finds itself in a border stand-off with China. But unlike other times when India and China squared off due to difference in ‘perception’ of Line of Actual Control (LAC) along their vast border from eastern Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh, the present stand-off is because of Chinese incursion in a region which is disputed territory between China and Bhutan. India has gotten involved because development in this area has serious security ramifications for India.

However, none of the reports barring one gives correct information about the geographical region where this stand-off has taken place and the likely reason for this new conflict. Even the report by Manoj Joshi only gives a broad outline of the area.

The objective of this report is to understand the boundary issue, claims of either party (China and Bhutan), geography in the area and Indian sensitivities. The thrust of this write-up is to clear the ambiguity about the exact area, where the present stand-off is taking place, and why India is reacting much more strongly – to the extent of helping to keep the China’s People's Liberation Army (PLA) out of Bhutanese territory.

Story so far – Confusion!

When the news story broke, it spoke about the Chinese removing Indian Army bunkers in Tri-Junction Area after the Indian Army prevented the Chinese from undertaking road construction activity. These reports mentioned certain key areas like the tri-junction, Dhoka La and Doklam Plateau.

This caused confusion because if you look at the map on Google Earth, these areas are not contiguous. Have a look at the map below. I’ve marked position of Dhoka La, India (Sikkim)-Bhutan-China (Chumbi Valley) boundary tri-junction and Doklam Plateau (as shown on Google Earth). Doklam Plateau from the tri-junction is about 30 kilometres as the crow flies while Dhoka La is about 5 kilometres south of boundary tri-junction.

So, a question arises – if the Chinese were building a road in the Doklam plateau on the China-Bhutan border, how did the Indian Army stop their work? And how does the boundary tri-junction area and Dhoka La come into the picture?

Bhutan-China border dispute

As per the Royal Government of Bhutan (RGOB), there are four areas of boundary-alignment dispute between China and Bhutan. However, as per the Chinese, there are seven such areas of boundary dispute. It is this mismatch in the number and extent of disputed areas which has led to the present stand-off.

I’m not getting into the entire Bhutan-China boundary issue, but will restrict myself to the current area of conflict.

As per the statement of the King of Bhutan in the National Assembly, there are four areas under dispute:

1. Up to 89 sq km in Doklam are under dispute (along Gamochen at the border, to the river divide at Batangla and Sinchela, and down to the Amo Chhu River)

2. Approximately 180 sq km in Sinchulumpa and Gieu are under dispute. The border line stretches from Langmarpo Zam along the river up to Docherimchang, through the river divide to Gomla, along the river divide to Pangkala, and finally down to the Dramana River.

3. Starting from Dramana, along the border line up to Zingula, and along the line of river divide down to Gieu Chhu River, and finally to Lungkala

4. Starting from the middle of Pasamlum, along the border-line and the river divide to Dompala and Neula, going from Neula along the border line and the river divide to Kurichhu Tshozam, along the river divide to Genla then to Mela, and go all the way to the east

Point (1) above is centred along and east of the India-Bhutan-China boundary tri-junction area. Point (2) refers to the area marked as Doklam plateau on Google Earth and shows as disputed with a broken line. As per the RGOB, there is no contiguity between areas covered under points (1) and (2) while Chinese claim an intermediate area as well. This makes the Chinese claims much larger than the Bhutanese interpretation and the root cause of the present conflict.

I’ve not been able to access any corresponding maps from the RGOB which show the alignment of the above area. As Joshi writes in his Indian Express article, “However, none of these features are visible on publicly available maps and it requires an effort to locate them.” I’ve created some indicative maps after searching through multiple sources and will come to that shortly.

And while I could not find any RGOB map showing disputed areas, I did come across a Chinese map which shows the seven disputed areas as per them. Please see the map below:

Areas with red and blue line indicate disputed areas as per the Chinese. The blue line indicates border alignment as per RGOB while the red line indicates the alignment of Bhutanese boundary as per the Chinese.

The disputed area in the west is the centre of the present conflict. And as per the Chinese, there are three major boundary alignment issues within this sector. Compared to this, RGOB claims only two non-contiguous areas of dispute. As the Chinese map shows, the Chinese claim is much larger than what the RGOB considers. The details of the three disputed areas in this region are as follows:

1. The mountain ridge from Batang La to Merukla/Merugla upto Sinchela

2. The mountain ridge from Sinchela to River Amo; along River Amo, from River Amo to its confluence with River Langmarpo;

3. Region along the River Langmarpo from the confluence of River Lang-marpo and River Amo up to the confluence of Docherimchang; along River Rong from River Docherimchang confluence to Gomla; Gomla ridge from Gomla to Pankala, and Pankala ridge from Pankala to Dramana ridge; Dramana ridge from Dramana to River Tromo and River Zhiu confluence, River Zhiu from River Tromo- River Zhiu confluence to Lungkala; (Source: Bhutan News Service)

If you look at the RGOB and Chinese interpretation of the boundary dispute, you realise that point (1) in both the interpretations of boundary alignment is the same. But in case of the Chinese, point (2) and (3) taken together, create a contiguous disputed area and vastly expand the area which they claim as being part of Tibet. From the Bhutanese perspective, point (3) in the Chinese claim is the same as per their understanding but is not contiguous to area under Point (1).

The blow-out map below shows how the Chinese claims are with respect to present alignment:

The Chinese are using their usual tactics – of claiming a ridge-line/water-shed (and corresponding mountain passes) which gives them depth and allows them to control west-east or vice versa movement. In case of Sino-Indian boundary in eastern Ladakh, the Chinese claim line lies along the ridge to the west of the Indian claim line and controls all the important mountain passes which can facilitate east-west or vice-versa movement. In this case, the boundary envelope has been pushed east with the following objectives:

1. Give depth to Chinese positions in the Chumbi Valley. As has been widely reported, Chumbi Valley is extremely narrow with steep mountain sides on either side. This gives very less real estate to the PLA to station troops and provisions. Further, this puts them at a disadvantage vis-a-vis the Indian position on the ridges to the west along the Sikkim-Tibet border.

2. The present main access route into Chumbi Valley and Yadong is S-204. Given the depth of the Chumbi Valley and its alignment, it is susceptible to Indian interdiction. The Chinese can consider developing a loop in S-204, which is further east and passes through the claimed area. This will give it a relatively better protection against Indian fire assault.

3. The most important gain is towards the south part – opens up the restricted funnel of Chumbi Valley and brings it that much closer to the Indian Siliguri corridor. The Indian area in the Siliguri corridor comes under long range artillery fire from within Chumbi Valley.

Doklam Plateau

The present stand-off is in the Doklam plateau area, region marked in blue circle in the previous map. If we revisit the Chinese boundary alignment claim in this region, it mentions the following:

1. Mountain ridge from Batang La to Merukla/Merugla upto Sinchela

2. The mountain ridge from Sinchela to River Amo; along River Amo from River Amo to its confluence with River Langmarpo

The map below highlights these areas and the alignment:

In case Chinese assertions are expected, then the India-China-Bhutan boundary will be at Gymochen. And Dokal La, which is presently on the border between India (Sikkim) and Bhutan, will become a pass on the Sino-Indian border.

A closer look at the satellite imagery shows that a road leads up from the Chumbi Valley to Senche La, crosses over to Bhutanese side, runs parallel to the Merug La-Senche La ridge line and then crosses back into Chumbi Valley at Merug La. A part of this road/track from Senche La also comes towards Doka La. It seems that the Chinese have extended tracks from the Merug La-Sinche La ridge line onto the Doklam plateau and have over the years slowly creeped forward claiming and controlling a larger part of the plateau.

The map below shows various roads/tracks in the region:

Present Issue

What seems to be happening is that the Chinese are trying to further expand their hold on the plateau. From the available news, it seems that the Chinese were trying to create concrete roads in the region. The maps already show tracks which came about as Chinese saw no objection from RGOB. And in typical Chinese fashion, they’ll now claim existence of these tracks as proof of ownership — apart from historical claims.

Any further advance in this area poses a security threat to India. Working in tandem with RBA, the Indian Army seems to have stopped this construction activity within Doklam plateau. This partly explains the apoplectic response from the Chinese —Indian Army is operating on Bhutanese territory and working in tandem with RBA to prevent further Chinese construction activity. Hence, the repeated references to this area having nothing to do with Sikkim-Tibet border and tri-junction.

India simply cannot afford to have the Chinese control the Doklam plateau. It has to prevent any further occupation creep beyond what has already happened. If the Chinese were to occupy the Doklam plateau and place the boundary on the ridge-line going east from Gymochen towards the Amo-Chu river, they control a dominating ridge-line which overlooks the Indian territory across Bhutan.

https://swarajyamag.com/defence/truths-mapped-out-india-cannot-afford-to-have-china-controlling-doklam-plateau

by Rohit Vats

0 notes

Text

Is Russia Practicing a Dry Run for an Invasion of Belarus?

Russia does military exercises regularly, but this year’s version, underway right now, deserves especially close attention. It’s called Zapad (“West”) and involves thousands of troops doing maneuvers on the borders of the Baltic states and Poland. The motivating scenario is to defend against an imagined invasion of Belarus by foreign-backed extremists. One of the fictional enemy states, “Vesbaria,” seems to be a thinly disguised Lithuania; the other, “Lubenia,” looks a bit like Poland. There will no doubt be the usual low-level provocations, with Russian planes buzzing borders, that will make the whole passive-aggressive show of strength look more like an invasion of the West than the other way around.

One extra element this time, however, is that these are joint exercises with Belarus, and not everyone in Belarus is happy to play host. The exercises are being staged in the northwest of the country, given the name of another fictional state, “Veyshnoria.” This is the historical heartland of real Belarusian nationalism, where Belarusian activists in the early 20th century competed with Poles, Lithuanians, and Jews to claim the old Tsarist administrative region of Vilna. Unfortunately for the Belarusians, much of this became Vilnius, the capital of modern-day Lithuania. But the rest remains in the northwest of modern Belarus, with the division testament to the long-standing love-hate relationship between Baltic peoples and Belarusians. Hence the Baltic-style spelling of Veyshnoria.

But the region also voted for President Aleksandr Lukashenko’s main opponent, the nationalist Zianon Pazniak, the last time Belarus had a real competitive election, back in 1994. So Zapad is directed as much against an “internal enemy” as against NATO powers, namely nationalists backed by the West. And that, worryingly, is the same scenario that Russia claimed to detect in Ukraine in 2014.

Some Belarusians have had fun with this. Veyshnoria now has its own Twitter account. You can buy T-shirts and mugs. Some 7,000 people have applied for its passports.

But there’s a serious aspect to all this, too. Russian exercises have a habit of becoming real. The Kavkaz (“Caucasus”) maneuvers in 2008 were basically a dry run for the invasion of Georgia. The last version of Zapad in 2013 preceded Russian action against Ukraine. The most notorious exercise of all was in 1981, when massive maneuvers were used to intimidate Communist Poland into suppressing the Solidarity movement. The fear this time is that Russian troops might manufacture an excuse to stay behind. In which case, the same scenario of nationalist extremists could be used as an excuse to “save” Lukashenko or even depose him. The official figure of only 12,700 soldiers involved would not be enough to occupy Belarus, but other estimates are 10 times as high.

Other neighbors are equally alarmed. NATO now has revolving forward deployments in Poland and the Baltic states. The U.K. has 800 troops in Estonia, the United States up to 1,000 in Poland. Ukraine’s official statement declares that “such exercises have been used repeatedly to achieve hidden military-political goals.… Transition of the state border and military invasion into the territory of Ukraine is not excluded.”

But Belarus bears the closest scrutiny. Tensions between Belarus and Russia have been growing acutely since 2014 — if not yet by enough for Belarus to dare to pull out of Zapad completely (though it has invited in neutral observers). In observing the exercises, the West would be wise not to treat Belarus as a potential belligerent but rather as an increasingly reluctant ally of Russia.

Lukashenko’s priority has always been survival. Belarus’s priority has always been protecting its sovereignty. The close relationship with Russia used to help on both counts. Now it is seen as laying Belarus open to the same kind of “hybrid war” or “active measures” used by Russia against Ukraine, especially as Moscow’s definition of “loyalty” has grown ever more demanding since 2014.

Lukashenko has taken elementary precautions to try to ensure that his security services are more loyal to him than the Ukrainian equivalents were to former President Viktor Yanukovych. But this has proved a Sisyphean task, as they are so closely institutionally connected with Russia. Senior Belarusian officers and KGB (a name Belarus is still proud to use) still do their training in Russia.

Lukashenko has maneuvered to appear diplomatically neutral. The capital of Belarus has hosted the Minsk process on peace in Ukraine. Belarus has not backed Russia militarily over Crimea or in eastern Ukraine and has resisted fierce pressure for several years to host a Russian air base on its territory.

Lukashenko has tried to balance Russia by expanding his options with the West. Belarus had been under sanctions since a rigged election in 2010 and subsequent crackdown against protests. But all political prisoners were released in August 2015. The EU then lifted its sanctions in February 2016 (though the United States was unable to follow, as its hands are more closely tied by the Belarus Democracy Act, passed in 2004). Lukashenko has sought loans, flirted with the IMF, and deepened relations with any organization that won’t lecture him too hard about his democratic credentials. This year, Belarus took the chair of the Central European Initiative, and the city of Minsk hosted the Parliamentary Assembly for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. EU officials have explored ways to make Belarus a real, rather than nominal, member of its flagship Eastern Partnership policy. In just two days in July, no fewer than four separate EU delegations visited Minsk.

Lukashenko, who was indifferent or even hostile to traditional Belarusian nationalism before 2014, has quietly pushed a program of “soft Belarusianization.” He has rejected Russian President Vladimir Putin’s pet idea that Belarus is part of the “Russian world.” Schoolbooks are being rewritten.

Lukashenko has endorsed pre-Soviet historiography beloved by nationalists, like the ancient history of Polatsk (in the north of Veyshnoria), as “our historical cradle … a peaceful, hard-working, and friendly state,” independent of both Moscow and Kiev. Lukashenko has even used Belarusian in public speeches, which is a first.

Peace has become Belarus’s new brand. It appeals to a very conservative population and gives Belarus another card to play with the West by posing as a “donor of security in the European region.” On a visit to Minsk in August, the streets were lined with state-sponsored billboards proclaiming, “We Belarusians are a peaceful people,” which is also the first line of the national anthem.

Lukashenko doesn’t want Ukrainian-style revolution either, but this is a tougher task. Traditionally, Lukashenko, who has survived in power as a dictator since 1994, has bought political acquiescence with economic growth. For 20 years, Belarus was not booming exactly but avoided the extremes of social dislocation, corruption, and oligarchy seen in Russia and Ukraine. The economy grew fairly solidly until 2008. Its initial wobbles thereafter could initially be blamed on the global economic crisis, but severe systemic problems set in in 2014. GDP fell by 3.9 percent in 2015 and 2.6 percent in 2016.

The secret of Lukashenko’s success was Russian subsidies — namely cheap oil and gas, though the benefit of these schemes was often split with Russian oligarchs. But, reeling under sanctions, Russia could no longer afford to be so generous. Moreover, it didn’t want to be, so long as Belarus was not playing ball over foreign policy. Russia also had to sort its own economy out first, via a sudden and unilateral devaluation in 2014 that hit Belarusian exports hard. Both countries have also struggled with lower oil prices. Lukashenko’s other main lifeline is the two modern oil refineries he inherited from the Soviet Union.

All this has undermined Lukashenko’s social contract with his traditionally passive population. Outside of Minsk, provincial towns depend on big state employers, which now only offer lower wages and part-time work. Migrant work in Russia has collapsed. The new reality is that there are two Belaruses: Minsk has a booming IT industry, but in the regions people struggle by on average wages as low as $150 a month.

This was the background to the unprecedented social unrest the regime faced this spring. Big demonstrations attracted thousands of people — and in small towns like Polatsk and Vitebsk, not just Minsk. The trigger was Lukashenko’s misguided “parasite tax,” a ham-fisted attempt to relieve pressure on the beleaguered state budget by forcing the economically “inactive” to pay a poll tax of about $250. But the definition of “inactive” was extremely broad, including young mothers and those looking after relatives, netting about 450,000 people in a workforce of 4.5 million. The result was a revolt of “his people,” rather than the traditional opposition, which Lukashenko had to allow breathing space. The decree was suspended but not withdrawn — a revised version is due in late September. Hundreds of people were eventually arrested and given administrative fines, but there were no serious sentences, unlike in previous protests. The long-term problem wasn’t solved.

Russia was reluctant to throw Belarus a lifeline. Compounded economic disputes have festered since 2014. The best that Lukashenko could get was a belated deal with Putin at St. Petersburg in April but with all sorts of strings attached. An additional loan of $1 billion was promised. Gas prices were discounted through to the end of 2019. Crude oil supplies to Belarus’s refineries were increased. But the hidden strings were unknown; Lukashenko spent most of the meeting alone with Putin. Belarus admitted that it had to pay arrears of $726 million in gas payments. Putin suggested that Belarusian refined oil should be diverted to Russian rather than Baltic ports. Rumors flew of an unknown security agenda or of unfinished business due to be completed by pressure during Zapad. Putin himself has taken a moderate line, but Russian nationalist critics of Lukashenko are being given a lot of media space.

How should the West respond? There should be contingency planning if Russian troops do outstay their welcome. The West should be better placed than it was over Ukraine in 2014 to detect fake scenarios (attacks on Russian troops, incursions over Baltic or Ukrainian borders) or invented excuses to impose a de facto Russian base in Belarus.

In the longer term, the West should remember that supporting dictators for reasons of realpolitik doesn’t always work out well. Whatever Lukashenko’s desire for a more “balanced” foreign policy, he hasn’t liberalized his country’s domestic politics. (It has even maintained the death penalty, the last country in Europe to do so.) But Belarus has to change. Its economic model is unsustainable, its security strategy extremely fragile. The West should encourage Belarus to take every small step in the direction of reform and proper sovereignty. The West should also encourage Russia not to overreact to such steps while preparing for it to do just that.

http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/09/18/is-russia-practicing-a-dry-run-for-an-invasion-of-belarus/?utm_content=buffer7b2b6&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

Andrew Wilson 18SEPT2017

0 notes

Text

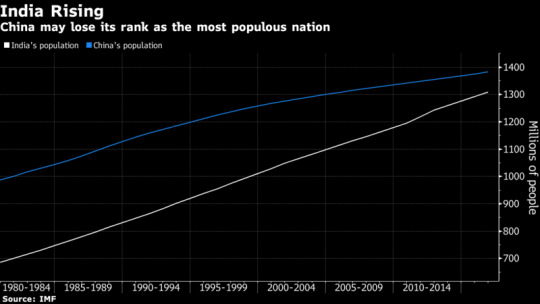

Superpower India to Replace China as Growth Engine

India is poised to emerge as an economic superpower, driven in part by its young population, while China and the Asian Tigers age rapidly, according to Deloitte LLP.

The number of people aged 65 and over in Asia will climb from 365 million today to more than half a billion in 2027, accounting for 60 percent of that age group globally by 2030, Deloitte said in a report Monday. In contrast, India will drive the third great wave of Asia’s growth – following Japan and China -- with a potential workforce set to climb from 885 million to 1.08 billion people in the next 20 years and hold above that for half a century.

``India will account for more than half of the increase in Asia’s workforce in the coming decade, but this isn’t just a story of more workers: these new workers will be much better trained and educated than the existing Indian workforce,’’ said Anis Chakravarty, economist at Deloitte India. ``There will be rising economic potential coming alongside that, thanks to an increased share of women in the workforce, as well as an increased ability and interest in working for longer. The consequences for businesses are huge.’’

While the looming ‘Indian summer’ will last decades, it isn’t the only Asian economy set to surge. Indonesia and the Philippines also have relatively young populations, suggesting they’ll experience similar growth, says Deloitte. But the rise of India isn’t set in stone: if the right frameworks are not in place to sustain and promote growth, the burgeoning population could be faced with unemployment and become ripe for social unrest.

Deloitte names the countries that face the biggest challenges from the impact of ageing on growth as China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Thailand and New Zealand. For Australia, the report says the impact will likely outstrip that of Japan, which has already been through decades of the challenges of getting older. But there are some advantages Down Under.

``Rare among rich nations, Australia has a track record of welcoming migrants to our shores,” said Ian Thatcher, deputy managing partner at Deloitte Asia Pacific. “That leaves us less at risk of an ageing-related slowdown in the decades ahead.’’

Japan’s experience shows there are opportunities from ageing, too. Demand has risen in sectors such as nursing, consumer goods for the elderly, age-appropriate housing and social infrastructure, as well as asset management and insurance.

But Asia will need to adjust to cope with a forecast 1 billion people aged 65 and over by 2050. This will require:

Raising retirement ages: Encouraging this could help growth in nations at the forefront of ageing impacts.

More women in the workforce: A direct lever that ageing nations can pull to boost their growth potential.

Taking in migrants: Accepting young, high-skilled migrants can help ward off ageing impacts on growth.

Boosting productivity: Education and re-training to bolster growth opportunities offered by new technologies.

— With assistance by Garfield Clinton Reynolds

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-17/superpower-india-to-replace-china-as-growth-engine?

by Michael Heath

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What the World’s Emptiest International Airport Says About China’s Influence

The four-lane highway leading out of the Sri Lankan town of Hambantota gets so little traffic that it sometimes attracts more wild elephants than automobiles. The pachyderms are intelligent — they seem to use the road as a jungle shortcut — but not intelligent enough, alas, to appreciate the pun their course embodies: It links together a series of white elephants, i.e. boondoggles, built and financed by the Chinese. Beyond the lonely highway itself, there is a 35,000-seat cricket stadium, an almost vacant $1.5 billion deepwater port and, 16 miles inland, a $209 million jewel known as “the world’s emptiest international airport.”

Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, the second-largest in Sri Lanka, is designed to handle a million passengers per year. It currently receives about a dozen passengers per day. Business is so slow that the airport has made more money from renting out the unused cargo terminals for rice storage than from flight-related activities. In one burst of activity last year, 350 security personnel armed with firecrackers were deployed to scare off wild animals, the airport’s most common visitors.

Projects like Mattala are not driven by local economic needs but by remote stratagems. When Sri Lanka’s 27-year civil war ended in 2009, the president at the time, Mahinda Rajapaksa, fixated on the idea of turning his poor home district into a world-class business and tourism hub to help its moribund economy. China, with a dream of its own, was happy to oblige. Hambantota sits in a very strategic location, just a few miles north of the vital Indian Ocean shipping lane over which more than 80 percent of China’s imported oil travels. A port added luster to the “string of pearls” that China was starting to assemble all along the so-called Maritime Silk Road.

Sadly, no travelers came, only the bills. The Mattala airport has annual revenues of roughly $300,000, but now it must repay China $23.6 million a year for the next eight years, according to Sri Lanka’s Transport and Civil Aviation Ministry. Over all, around 90 percent of the country’s revenues goes to servicing debt. Even a new president who took office in 2015 on a promise to curb Chinese influence succumbed to financial reality.

To relieve its debt crisis, Sri Lanka has put its white elephants up for sale. In late July, the government agreed to give China control of the deepwater port — a 70 percent equity stake over 99 years — in exchange for writing off $1.1 billion of the island’s debt. (China has promised to invest another $600 million to make the port commercially viable.) When the preliminary deal was first floated in January, protests erupted in response to the perceived sell-off of national sovereignty, a reminder of Sri Lanka’s colonial past under British rule. “We always thought China’s investments would help our economy,” says Amantha Perera, a Sri Lankan journalist and university researcher. “But now there’s a sense that we’ve been maneuvered into selling some of the family jewels.”

As the United States beats a haphazard retreat from the world — nixing trade agreements, eschewing diplomacy, antagonizing allies — China marches on with its unabashedly ambitious global-expansion program known as One Belt, One Road. The branding is awkward: “Belt” refers to the land-bound trading route through Central Asia and Europe, while “Road,” confusingly, stands for the maritime route stretching from Southeast Asia across the Indian Ocean to the Middle East, Africa and Europe. Still, the intentions are clear: With a lending and acquisitions blitz extending to 68 countries (and counting), OBOR seeks to create the ports, roads and rail and telecommunications links for a modern-day Silk Road — with all paths leading to China.

This is China’s long game. It’s not about immediate profits; infrastructure projects are a bad way to make money. So why is President Xi Jinping fast-tracking OBOR projects amid an economic slowdown at home and a crackdown on other overseas acquisitions? Economics is a big part: China wants to secure access to key resources, export its idle industrial capacity, even tilt the world order in its favor. But there is also a far greater cultural ambition. For centuries, Western liberalism has ruled the world. The Chinese believe their time has come. “China sees itself as a great civilization that needs to regain its status as leader of the world,” says Kadira Pethiyagoda, a fellow at the Brookings Institution Doha Center. “And America’s retreat gives China the space to do that.”

It’s tempting to see OBOR as a muscled-up Marshall Plan, the American-led program that helped rebuild Western Europe after World War II. OBOR, too, is designed to build vital infrastructure, spread prosperity and drive global development. Yet little of what China offers is aid or even low-interest lending. Much OBOR financing comes in the form of market-rate loans that weaker countries are eager to receive — but may struggle to repay. Even when the projects are well suited for the local economy, the result can look a bit like a shell game: Things are built, money goes to Chinese companies and the country is saddled with more debt. What happens when, as is often the case, infrastructure projects are driven more by geopolitical ambition or the need to give China’s state-owned companies something to do? Well, Sri Lanka has an empty airport for sale.

Sri Lanka may be a harbinger for debt crises to come. Many other OBOR countries have taken on huge Chinese loans that could prove difficult to repay. For example, Chinese banks, according to The Financial Times, recently lent Pakistan $1.2 billion to stave off a currency crisis — even as they pledged $57 billion more to develop the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. “The projects China proposes are so big and appealing and revolutionary that many small countries can’t resist,” says Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at New Delhi’s Center for Policy Research. “They take on loans like it’s a drug addiction and then get trapped in debt servitude. It’s clearly part of China’s geostrategic vision.”

This charge conjures the specter of colonialism, when the British and Dutch weaponized debt to take control of nations’ strategic assets. China insists it is nothing like a colonial power. Its appeal to developing countries, after all, is often based on a shared negative experience of colonialism — and the desire to have cooperative “win-win” trade and investment relationships. Unlike Western countries and institutions that try to influence how developing countries govern themselves, China says it espouses the principle of noninterference. If local partners benefit from a new road or port, the Chinese suggest, shouldn’t they be able to “win,” too — by securing its main trade routes, building loyal partnerships and enhancing its global prestige?

The last time China was a global power, back in the early 1400s, it also sought to amplify its glory and might along the Maritime Silk Road, through the epic voyages of Zheng He. A towering Ming dynasty eunuch — in some accounts he stands seven feet tall — Zheng He commanded seven expeditions from Asia to the Middle East and Africa. When he came ashore on Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) around 1406, his fleet commanded shock and awe: It was a floating city of more than 300 ships and some 30,000 sailors. Besides seeking tributes and trade — the ships were laden with silk, gold and porcelain — his mission was to enhance China’s status as the greatest civilization on earth.

After Zheng He’s death at sea in 1433, China turned inward for the next six centuries. Now, as the country has become a global power once again, Communist Party leaders have revived the legend of Zheng He to show China’s peaceful intentions and its historical connections to the region. His goal, they say, was not to conquer — unlike Western empires — but to establish friendly trade and diplomatic relations. In Sri Lanka today, Chinese tour groups often traipse through a Colombo museum to see the trilingual stone tablet the admiral brought here — proof, it seems, that China respected all peoples and religions. No mention is made of a less savory aspect of Zheng He’s dealings in Ceylon. On a later expedition, around 1411, his troops became embroiled in a war. Zheng He prevailed and took the local king back to China as a prisoner.

The unsanitized version of Zheng He’s story may contain a lesson for present-day China about unintended consequences. Pushing countries deeper into debt, even inadvertently, may give China leverage in the short run, but it risks losing the good will essential to OBOR’s long-term success. For all the big projects China is engaged in around the world — high-speed rail in Laos, a military base in Djibouti, highways in Kenya — arguably its most perilous step so far may be taking control of the foundering Hambantota port. “It’s folly to take equity stakes,” says Joshua Eisenman, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “China will have to become further entwined in local politics. And what happens if the country decides to deny a permit or throw them out. Do they retreat? Do they protect?” China promotes itself as a new, gentler kind of power, but it’s worth remembering that dredging deepwater ports and laying down railroad ties to secure new trade routes — and then having to defend them from angry locals — was precisely how Britain started down the slippery slope to empire.

Brook Larmer is a contributing writer for the magazine. His last article was about a Chinese-owned uranium mine in Namibia.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/magazine/what-the-worlds-emptiest-international-airport-says-about-chinas-influence.html

0 notes

Text

Boeing flags inexperience of Indian private sector 'strategic partners'

In New Delhi on Thursday [07SEPT17], the world’s largest aerospace corporation, The Boeing Company, openly expressed what many global arms vendors have complained about in private: The Indian private sector is not yet capable of manufacturing complex military aircraft under transfer of technology (ToT).

Pratyush Kumar, Boeing’s India chief, proposed that highly experience defence public sector undertakings (DPSUs) – like Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL) – be coopted, since that is where aerospace expertise and experience lies in India.

Speaking “from the vantage point of a company that has been in the aerospace industry for 100 years, across the world,” Kumar in effect proposed a major reorientation of the defence ministry’s new Strategic Partner (SP) policy.

The policy aims at creating capable defence manufacturers in the private sector, to compete with the DPSUs and Ordnance Factories (OFs) that have historically dominated defence manufacture in India. The policy requires private firms chosen as SPs to enter technology partnerships with nominated global “original equipment manufacturers” (OEMs), and jointly bid for contracts to build aircraft, helicopters, submarines and armoured vehicles for the military.

But Kumar, speaking at a seminar organised by the Centre for Air Power Studies, the air force’s think tank, pointed out that successful examples of ToT-based manufacture involved “co-opting of public enterprise and private enterprise in a way that leveraged the investment made in the public enterprise for multiple decades”.

The Boeing chief said he “tried hard, and could not find a single example [of successfully building an aircraft under ToT] where it was just the brand new private enterprise with limited aerospace experience. Look at Turkey, look at Japan, look at Brazil — look at multiple countries. In all cases, there is a fine balancing act of co-opting the capabilities of both public and private enterprise.” Other foreign companies are less forthright than Boeing. With two multi-billion dollar aircraft acquisitions already launched via the SP route — for single-engine fighter aircraft and helicopters — foreign OEMs have begun partnering Indian private firms. Lockheed Martin has partnered Tata Advanced Systems Ltd (TASL) and Saab has partnered the Adani Group, anticipating a tender for the single-engine fighter.

This although TASL has never assembled an aircraft, while the Adanis have never built a single aerospace component. Foreign OEMs resent having to partner novices, but comply quietly so as not to rock the boat, said a foreign executive based in India.

Boeing is more forthright, bolstered by the confidence of being the most successful arms vendor in India over the last decade. Since 2009, Boeing has sold India aircraft worth $12 billion. These include eight P-8I maritime aircraft in 2009, and then four in a follow-up order; ten C-17 Globemaster III heavy lift aircraft in 2011; and 15 Chinook CH-47F and 22 Apache AH-64E helicopters in 2015.

While these were all sales of ready-built aircraft, Boeing is perhaps anticipating having to “Make in India” with an SP in another forthcoming contract — the navy’s multi-billion dollar acquisition of 57 ship-borne fighters for its aircraft carriers. In that acquisition, for which a tender is awaited, Boeing’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornet would possibly compete with Dassault’s Rafale-Marine; Saab’s Sea Gripen and an upgraded version of the Russian MiG-29K/KUB. Aspiring Indian SPs, like TASL, admit that their role in an SP contract would remain “build to print”, i.e. manufacturing sub-assemblies and assemblies to blueprints provided by the OEM. Yet, it would provide a lucrative growth opportunity.

“The need of the hour is for the ministry of defence to go forward with the two very large aerospace orders [for] single engine fighter and helicopters. Frankly, in my mind, there is nothing else to it,” said TASL chief, Sukaran Singh, at the same seminar.

In contrast, HAL chief T Suvarna Raju talked up his engineers’ design skills and experience. Pointing to the range of helicopters HAL has designed ground-up – the Dhruv advanced light helicopter, Rudra armed helicopter, and the eponymous Light Combat Helicopter and Light Utility Helicopter – he declared: “Each component of our helicopters demonstrates the skill sets of HAL designers, of their capabilities and innovation efforts. Look at the carbon composite blades and the transmission system, composite body structure, glass cockpit and many more…” The air force, however, continues to back the SP policy. “The only way to sustain the momentum in the aerospace manufacturing space is to start manufacturing here and strategic partnership model is a step in the direction,” said Air Marshal Shirish Deo, the air force’s vice-chief. The SP policy has been in the making since 2014-15. It remains contested and a work in progress.

http://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/boeing-flags-inexperience-of-private-sector-strategic-partners-117090800051_1.html

Ajai Shukla First Published: Fri, September 08 2017. 01:49 IST

#india#us#arms transfer#transfer of technology#us-india#india-us#boeing#defense relationship#ajai shukla

0 notes

Text

China deepens overseas port holdings

China is moving to deepen its overseas port holdings with the purchase of Brazilian port operator TCP Participações for nearly $1bn, the latest inroads into South America for a Chinese state-backed group.

China Merchants Port Holdings on Monday said it had agreed to buy 90 per cent stake of TCP Participações for $924m. The deal will give the company its first port operating capabilities in Brazil.

The company will buy the shares from investment funds including Fundo de Investimento em Participações, Soifer, Pattac and Tuc Par. The remaining 10 per cent of TCP will be held by Soifer, Pattac and Tuc Par.

Earlier this year China Merchants Port, which is part of a state conglomerate with holdings in banking and shipping, said it would invest more than $1bn to develop and operate Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka. That deal was part of a Chinese government drive to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in a series of ports, roads and other infrastructure spanning across Eurasia and into South America.

The initiative is often referred to as China’s New Silk Road and is one of President Xi Jinping’s top global efforts. Over the past year, it has helped accelerate China’s drive to take over and operate ports around the world.

In the year to June, Chinese groups announced plans to buy or invest in nine overseas ports in projects valued at a total of $20.1bn, according to a study by Grisons Peak, a London-based investment bank. That was a sharp increase from the $9.97bn in Chinese overseas port projects in the same period a year earlier, according to Financial Times calculations.

As ports around the world attract Chinese investment, so too have global shipping companies. In July, Cosco agreed to buy Hong Kong’s Orient Overseas Container Line in a $6.3bn, which would make state-owned Cosco the world’s third-biggest container shipping group.

While Chinese regulators have tightened controls this year on overseas investment by private companies, acquisitions by state groups have been easier to execute. Overseas deals connected to China’s New Silk Road initiative have been encouraged by the country’s leaders, and most of such investment has been made by state-backed groups.

While far from Beijing’s focus on Eurasia, Latin America also has become a beneficiary of the New Silk Road project and an increasingly attractive destination for Chinese investment in infrastructure over the past two years.

Chinese companies have agreed to $7.9bn in Latin American infrastructure deals since the start of the year, according to Dealogic, and are on track to surpass last year’s deal volume of $9.9bn.

Brazil has been the primary target, with nine of the 10 largest infrastructure deals in the region done in the country since 2013. Utility and energy deals have been at the top of the list for government-controlled groups such as State Grid, which has spent more than $13bn in the country since July 2016.

https://www.ft.com/content/451e1b80-912c-11e7-bdfa-eda243196c2c

04SEPT17

0 notes

Text

Mexican port growth outpaces US, Canada

Cargo volumes through Mexican ports increased by 5.5 percent in 2016, outpacing its two North American Free Trade Agreement counterparts, despite the weakening peso, gas price hikes, and transportation-link blockades. Yet the year ahead may be even more difficult for Mexico, given the uncertainty over its trade with the United States, and will likely be far tougher than for its counterparts.

Mexican ports handled 4.1 million loaded twenty-foot-equivalent containers in 2016, up from 3.9 million TEUs in 2015, according to figures released by the Mexican Secretariat of Communications and Transport, which oversees the port system. That was slightly better than the 5.1 percent year-over-year increase in 2015.

It was also stronger than the 2016 performance of US ports, where the volume of loaded TEUs increased by 3.3 percent over 2016. Mexico also seems to have done better than Canada. Although national figures for Canadian ports are not available, laden volumes through four of the country’s largest ports — Vancouver, Montreal, Prince Rupert, and Port Saint John — grew by just over 0.5 percent.

The volume of loaded containers imported into Mexico, which accounts for about 60 percent of Mexico’s loaded container volume, increased by 5 percent year-over-year in 2016 as loaded exports increased by 6 percent. The figures were driven in part by strong volume growth at the largest Gulf Coast port, Altamira, and at Lazaro Cardenas on the Pacific Coast, while volume slowed at the nation’s busiest container port, Manzanillo.

Under normal circumstances, solid 2016 figures would mean Mexico’s logistics industry is entering 2017 with a promising hand, especially given the federal government’s vigorous commitment to spend $5 billion on upgrading the port system. Port improvements set to come online in the next 12 months include a new terminal built by APM Terminals that is set to open on Feb. 27 at the Port of Lazaro Cardenas; a new rail tunnel at Manzanillo to open by the end of the year; and a continuing construction project at the nation’s largest port on the Gulf of Mexico, Veracruz, that is planned to increase its 900,000-TEU capacity five-fold by 2030. Mexican officials recently called Veracruz the nation’s biggest infrastructure investment in 100 years.

Yet the industry instead begins the year facing the turmoil of the Trump administration’s threat to renegotiate NAFTA and put up tariffs on Mexican goods coming into the United States, and the administration’s pressure aimed at dissuading US companies from investing in Mexican projects. All of which could reduce trade and container volumes.

Of particular worry is President Donald Trump’s focus on the automobile industry, which has become the backbone of the Mexican manufacturing sector and now includes more than a dozen plants — among them for Ford, Chrysler, Fiat, and General Motors. Already, Ford — under pressure from Trump — has retreated from a plan to build a new factory in Mexico that would support 700 jobs, although it still plans to shift production of its Focus model from Michigan to Mexico.

“Most of the automotive production in our country is destined for export,” said Guillermo Deister Mateos, head of SCT’s maritime and port strategic planning unit. About 80 percent of the 3.4 million cars made in Mexico in 2016 were exported, including 1.1 million through the ports, he said.

Moreover, imports of car parts to be fitted into new cars were one reason for the increase of loaded container volumes through Altamira, he said. The volume of full TEUs through the port grew by 8.6 percent in 2016, over the previous year, including a 12 percent increase in imports, government figures show.

Mario Veraldo, managing director for the middle Americas, including Mexico, for Maersk Line, said it’s too early to speculate about Trump’s impact on the Mexican port industry in 2017 because so few details are known.

“Protection is very bad for all the countries involved,” he said, adding that Trump’s policies may provide impetus for Mexico to further diversify the customer base beyond the United States, which has started already.

On the export side, Mexico is increasingly “relevant” in the refrigerated business, catering to food producers, especially of bananas and avocados, who want an “end-to-end cold chain,” he said. “[Mexican] reefers are making their way into new markets like China, and, for example, bananas are going to Europe.” Likewise, the port of Lazaro Cardenas benefitted from a large volume of aluminum exported to Southeast Asia. On the import side, auto-parts are increasingly coming to Mexico from Asia, he said.

Veraldo said Maersk expected slightly bigger growth in Mexican cargo volumes in 2016, but the weak peso hurt the economy. The peso fell more than 20 percent against the dollar in 2016, making imports into Mexico more expensive and exports cheaper for foreign buyers, which likely contributed to the change in Mexico’s cargo volume patterns compared with 2015. The 5 percent increase in imported loaded TEUs was smaller than the 10 percent year-over-year increase in 2015, and the 6 percent increase in loaded export volumes was a strong improvement over the 1.5 percent decline year-over-year in 2015.

Along with the weakening peso, Mexico’s logistics industry in 2016 was affected by civil disturbances as a result of the government’s decision to raise fuel prices, which increased the price of diesel by 16 percent, boosting the cost of moving freight and prompting blockades of highways that temporarily affected the Port of Veracruz. In July, angry teachers mounted a blockade of freight rail lines into the ports of Lazaro Cardenas and Manzanillo, bringing the movement of thousands of containers to a standstill in a nationwide series of protests over education reforms.

Veraldo said those disturbances did not appear to have had much impact on Mexico’s annual terminal volumes. And port volumes were shaped by other local issues at each port.

The relative weakness of Manzanillo’s cargo volume, which grew by just 2.5 percent in 2016, and the strength of that in Lazaro Cardenas, which enjoyed a 10 percent increase, stemmed in part from Manzanillo’s status as the nation’s busiest port, Deister Mateos said.

“Manzanillo has always been an attractive port for cargo going to central and northern Mexico but also to the southern states of the United States that connect via railroad to the port,” he said. In 2016 “the port was saturated and had a serious lack of space.” As a result, some shippers decided to move their cargo to Lazaro Cardenas, Deister Mateos said.

The space shortage will soon be resolved by the construction of a new port, called Cuyutlan, which is in the planning stage and will be built next to the existing Manzanillo port, he said. And later this year Manzanillo will another long-running difficulty, the fact that the rail freight access to the port is limited to four times a day by having to run through the city center, Deister Mateos said. The new rail tunnel will provide 24-hour access to the port, he said.

Similarly, Mexico’s third-largest port, Veracruz, will experience a major development in 2017 with the relocation of the ICAVE Terminal, operated by Hutchison Port Holdings, from the old port to the new section under construction, he said.

Contact Hugh R. Morley at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter: @HughRMorley_JOC.

https://www.joc.com/port-news/international-ports/port-l%25C3%25A1zaro-c%25C3%25A1rdenas/mexican-port-growth-outpaces-us-canada_20170215.html+&cd=6&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

02SEPT17

0 notes

Text

Why India did not win the Doklam standoff

The end of a standoff between India and China over a remote road on the Doklam plateau has prompted a vibrant discussion about the lessons learned. The emerging consensus is that India “won” and China “lost.” India’s willingness to challenge China is even viewed as providing a model that other states can use to counter Chinese coercion. If others stand up, China will back down.

Nevertheless, this consensus is misplaced. And the sports analogy of winning and losing obscures much more than it reveals.

To start, it remains unclear that India “won.” From India’s point of view, the status quo ante of June 2017 was restored, a victory. Yet from China’s perspective, Indian forces withdrew from Chinese territory (also claimed by Bhutan, but not by India). Moreover, on the ground at the site of the confrontation, Indian forces pulled back first. Meanwhile, Chinese forces remain in Doklam, even if Beijing chose not to press ahead with the road extension that sparked the standoff.

There is also no indication from Chinese or Indian statements that China had to make any concessions to convince India to withdraw its troops. The PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson underscored that China’s claims and behavior will not change, noting that China would “continue with its exercise of sovereign rights” in the disputed area. In other words, China will still conduct patrols in Doklam and maintain the portions of road that had been built before the standoff started in early June.

China also had other reasons to seek de-escalation, none of which can be attributed to India’s intervention. An active confrontation would have cast a pall over the upcoming BRICS summit that China is hosting in Xiamen in early September. And on the eve of the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Party Congress, Xi Jinping likely wanted to avoid any risky escalation that could affect the significant transfer of power that will occur. Once these events pass, however, China may be less constrained and more willing to tolerate risk on the border with India.

Moreover, even if India scored a tactical win by thwarting China’s road extension, it may have lost at the strategic level. Ironically perhaps, India’s actions underscored to China the importance of enhancing its military position in the Doklam bowl. Before the standoff in June, China’s permanent presence in the area had been quite limited. China had maintained a road in the area for several decades, but did not garrison any forces. In contrast, India has maintained and developed a forward post at Doka La adjacent to Doklam.

Now that India has chosen to confront China at Doklam, however, China may well seek to rectify this tactical imbalance of forces. In fact, the Chinese spokesperson suggested a move in this direction by saying China would continue to station forces (zhushou), most likely a reference to troops deployed to Doklam after the standoff began. If China does this, it would likely build facilities farther away from India’s position at Doka La, making it more challenging for India to intervene and block China next time. When India challenged China’s construction crews in June, it only had to move its forces a hundred meters from the existing border. In the future, India may be faced with the uncomfortable choice of deciding whether to risk much more to deny China a greater presence farther inside Doklam or to accept it. This will be a tough decision for any leader to make. Even if India won this round, it may not win the next one.