The Outside Corner is a blog dedicated to the analysis of baseball and football. The author is a lifelong sports nerd with too much time on his hands. Recommended Reading:  Baseball Reference blog   Cold Hard Football Facts   FanGraphs   River Ave Blues

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Why I use pitches/out and not pitches/PA

I got into a friendly Twitter debate a few weeks ago about whether pitches/out offers merits relative to pitches/plate apperance as a measure of pitcher efficiency. I strongly believe that it does, and I'd like to offer a couple of thought playful thought experiments as evidence.

Imagine two pitchers of opposite skill levels in the extreme -- one really good and one really bad.

Let's say the first pitcher is so amazing at his craft that no hitter is ever able to actually hit a ball he swings at, and he has such great control that he can throw the ball for a strike whenever he wants to. Naturally, every pitch this pitcher throws will be a strike.

And now let's say the second pitcher is me. Now, in my defense, my last competitive appearance as a pitcher was quite successful. I pitched one relief inning, with one strikeout, one ground ball fielded cleanly with a throw to first, and one popup caught. All in that inning. Also, I was 12.

Today, my fastball probably tops out around 65 mph. From 60 feet, 6 inches away, I could probably hit the strike zone in one out of every ten tries. I would probably hit a number of batters, walk a great deal of others, and surrender long hits to the rest. The only way I could get outs is by sheer luck of BABIP or over-aggressive baserunning.

The first pitcher's p/PA will always be 3. Mine will probably range between 2 and 4. In other words, there is not much difference, despite the monumental difference in talent level between the pitchers.

Meanwhile, the first pitcher's p/out will also always be 3. Mine will probably range between 30 and 40. In other words, that gives you an idea of how much worse I am than that first pitcher. And that's why I think p/out will give you a better idea of pitcher efficiency than p/PA.

0 notes

Text

Changes in Strasburg's pitching grips since college

I stumbled upon an ESPN video of Stephen Strasburg from 2009 showing the grips on his four pitches. He still throws four pitches, but two of them different grips now. Here's a quick look at those two:

Breaking ball:

In 2009, Strasburg called this pitch a slider. It's now commonly referred to as a curveball, and the newer grip is certainly closer to a standard curveball grip. It has big sweeping action like a slider, but it drops a good amount, too, and is thrown significantly slower than his fastball.

"Sinker"

The other change is on what Strasburg called his sinker. Previously he used a non-standard "one-seam" grip. Now it appears he uses a standard two-seam.

0 notes

Text

David Phelps's new (improved?) cutter

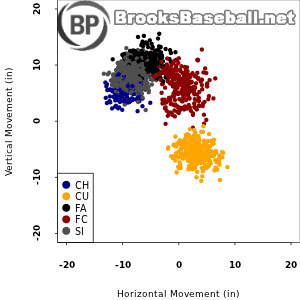

While digging around in Yankee pitcher David Phelps's data, I noticed something a little unusual about his cut fastball: it looks like there's two distinct "clusters" of pitches. Check it out for yourself on the right. (This graph includes data from the 2011 Arizona Fall League and 2012 MLB seasons. MLB Advanced Media calls his pitch a slider; I'm using Brooks Baseball's designation as a cutter, which is supported by photographic evidence.)

I found that the division in spin signatures is something that can probably be explained by a mid-2012 stint Phelps had in AAA. (Phelps started the year in the big leagues, was demoted on June 15 to make roster room for David Robertson, then re-promoted when Andy Pettitte was injured two weeks later.)

Apparently in the short time he spent in the minors, he made some sort of adjustment to his cutter that is clearly visible by looking at the "before" and "after" spin deflections.

What adjustment he made, exactly, is unclear. In included a trendline to show that the pitch not only got more "rise" after his demotion, but its distribution across the chart is slightly different. That, coupled with the fact that the PITCHf/x data show no change in release point, invite the idea that he has slightly modified his grip or release action.

Due to an insufficient sample size, it's hard to say if his cutter got markedly better because of this change. (He only threw 74 of them post-minors in 2012.) I'll be watching this season to see how the adjustment turns out. In any case, Phelps's cutter will be an important tool for him as he becomes a likely candidate for the back end of the Yankees' starting rotation in 2013 and beyond.

Great thanks to MLB Advanced Media and Sportvision for the PITCHf/x data used in this post, as well as Harry Pavlidis for the Pitch Info/Brooks Baseball pitch classifications.

0 notes

Text

A scouting report on Rafael Soriano

Rafael Soriano has been a productive relief pitcher since 2003. He figures to close for the Nationals in 2013. However, he has experienced a number of arm injuries and is 33 years old. Soriano’s ERA is consistently quite low (career 153 ERA+), although there are risk factors for a drop-off in performance during his time in Washington.

Reportoire

Four-seam fastball: 91–94 mph. In many respects, his best pitch. Opponents have hit .180 against it since 2007, ranking 5th out of 173 relief pitchers who’ve thrown more than 1000 four-seamers since 2007. Lateral movement is minimal, often giving it the appearance of a cutter. Has good life, as shown by high whiff/swing rate (has never been below 23%). Velocity has dropped slightly in recent years, but he figures to stay pretty close to his 2012 numbers. Thrown fairly high in the zone, which has made him a fly-ball pitcher (0.63 GB/FB since 2007, per Brooks Baseball). Typically gets above-average frequency of pop-ups. He is not afraid to pitch up and in to righties, but he avoids throwing in to lefties.

Slider: 80–86 mph. Used nearly as often as his fastball (> 40%). Thrown to hitters from both sides of the plate, typically low and away. Especially common against lefties with 2 strikes. Even with frequent use, its whiff rate is average (≈ 30%).

Two-seam fastball: 91–94 mph. Used exclusively on lefties, especially early in the count. He runs it off the outside corner. Has decent tailing action relative to four-seamer, but little sink. Primarily a show-me pitch.

Defense-independent pitching

Soriano’s strikeout totals have been good-to-great throughout his career (26% K, 9.4 K/9). His walks fluctuate, winding up near the league average overall (8% BB, 2.9 BB/9). Home run rate is also about average (0.9 HR/9). That typically creates a good pitcher but not someone whose career ERA+ is 153. In fact his career ERA (2.78) is tiny compared to his career FIP (3.30) and xFIP (3.69). He also outpaces his SIERA (3.11) and tERA (4.06).

As a fly-ball pitcher, Soriano’s xFIP is somewhat “artificially” high because his home-run rate as a percentage of fly-balls is consistently better-than-average. Still, his ability in five of the last seven years (including his four best ERAs) to significantly outperform his FIP is significant and has a probable explanation.

It turns out that Soriano has benefitted hugely from an impressive career BABIP of .249 (FanGraphs) or .251 (Baseball Reference). In his masterful 2010 season, it was just .199. (In his previous, merely respectable season, it was .280.)

The last couple of years have seen a rebound of his BABIP to .279 and then .274. If this represents a trend, Soriano’s performance in the future could suffer. Last season, he had an anomalously high LOB% of 88% (he’s typically closer to 75–80%). It’s not hard to see how a middling walk percentage suddenly becomes more dangerous if hitters are starting to make better contact. In fact, Soriano’s ERA from 2009–2012 correlates strongly with his BB% (.94) and BABIP on his fastball (.63). Strikeouts had almost no correlation.

Potential red flags

As discussed above, Soriano relies almost entirely on two pitches, and a key to his success has been making his fastball hard to hit well. He’s very effective against right-handed hitters partly because he can pitch them inside without fear. If Soriano’s velocity continues to decline, it could spell trouble for that strategy. Being a fly-ball pitcher with a hittable fastball and occasional tendency to walk hitters would be a bad recipe for a 9th-inning guy. Soriano has thrown a changeup and cutter in the past, and if his fastball loses potency he might need to re-expand his repertoire.

He has a long history of arm troubles, with a Tommy John operation in 2004, several DL stints for elbow inflammation, and various other maladies. His mechanics put strain on his elbow during the cocking phase, which explains the history of elbow issues. He also throws an unusually large percentage of his pitches as sliders, which is thought to be harmful to the elbow. As a 33-year-old, his body won’t heal faster than he did when he was 25 and had Tommy John surgery.

Other tidbits

He’s not much of a fielder, either in range or graceful handling.

Outlook

For most of his career, Soriano has been a very good, albeit often overpaid relief pitcher. He has the mental fortitude to be a closer, and when he’s good he has the stuff for it. He will need to be very careful about his walk total and the effectiveness of his fastball. He is also at an above-average risk for arm injuries.

For the sake of preserving his elbow and to compensate for potential fastball velocity loss, perhaps the Nationals will encourage Soriano to rediscover his cutter or changeup.

This report was made possible due to the data at Baseball Prospectus, Baseball Reference, Brooks Baseball, and FanGraphs.

0 notes

Text

A scouting report on Dan Haren

From 2005 through May 2012, Dan Haren was about as reliable a starter as there was in the big leagues. In mid-2012, however, a back injury threw him off rhythm and led to his first DL stint. In five starts beginning June 9, Haren’s ERA was 8.67 with a .695 opSLG. Outside of those five starts, his season ERA was 3.55.

Repertoire

Sinker: 88–91 mph. Used against lefties and righties alike. Thrown most often early in the count or when behind. Keeps it away from hitters, and tends to throw it fairly high in the zone. This could explain a below-average ground ball rate on the pitch. Velocity has dropped somewhat the last several years. Does not have a great amount of lateral or vertical movement.

Cutter: 84–87 mph. Most common pitch, especially to righties. Pounds the low outside corner to righties and down and in to lefties. Has also lost velocity in recent years. Above-average lateral movement. Good whiff rate.

Splitter: 82–86 mph. Third most-used pitch. Saw increased usage in 2012. Typically used when ahead and with two strikes. Has lost effectiveness as a swing-and-miss pitch since 2009 (from 40% to about 25%). Still has by far the lowest BAA and ISO of any of his pitches.

Curveball: 76–79 mph. Thrown with a “spike” grip. Has gone from being a main weapon to a little-used “show me” pitch. Often used to “steal” strike one against lefties. Almost never used against righties at all. Not a great amount of depth, although it has some lateral movement.

Four-seam fastball: 88–90 mph. Infrequent offering. Sometimes used as a two-strike pitch against lefties.

Defense-independent pitching

Haren’s most distinguishable asset is his control; he typically walks less than 2 batters per 9 innings. His strikeout totals are average, but his SO/BB ratio is still outstanding. He gives up a fair amount of home runs, however, so his FIP is good but not amazing. His career BABIP is .291, indicating no unusual trends in that department.

He has historically been a very durable pitcher; he started at least 33 games and logged at least 215 innings for seven straight seasons (2005–2011).

Potential red flags

His solid mechanics should protect him against serious arm injuries, but the back stiffness issue was enough of a concern to lead the Chicago Cubs to scrap a deal for Haren early this offseason.

His velocity has declined consistently for several seasons and could continue to do so in 2013. Haren has never been an overpowering pitcher, and pitchers can be effective without great speed. Still, all things being equal, faster pitches get hit less often. It will be essential for Haren to command his pitches, or else he will start getting hit hard.

Other tidbits

For a pitcher, Haren is an excellent hitter. He is a career .223 hitter with 21 doubles in 264 at-bats.

His fielding is decent. His range is limited, but he makes few errors (.972 fielding percentage).

Outlook

Haren is probably in line for a resurgent 2013 season. He will have the benefit of playing the National League again, an offense that should provide good run support, and a good bullpen behind him. If his back stays healthy, he will be a valuable addition to the Nationals rotation.

Baseball Reference, Baseball Prospectus, Brooks Baseball, and FanGraphs were eminently helpful in the making of this post.

0 notes

Text

Don't vote for Todd Frazier over Bryce Harper as NL RoY

With the Washington Nationals having been eliminated from the playoffs, the next thing for their fans to anticipate is awards season. Gio Gonzalez is a strong contender for the Cy Young Award, and young Bryce Harper is the clear choice for National League Rookie of the Year. The voters atThe Sporting Newspicked Harper third, however, behind Arizona’s Wade Miley and Cincinnati’s Todd Frazier. The choice of Miley is, I guess, defensible. He plays a premium position (starting pitcher) and performed objectively well in that role. Frazier, however, is not the National League Rookie of the Year. He had a solid offensive year but did not finish in the top 10 in any offensive category. His defense was unspectacular, finishing with -0.2 defensive wins above replacement, according to Baseball Reference. He finished at 1.7 WAR, or 2.2 if you extrapolate to 162 games. Harper was an electric player in 2012. His raw stats — .270/.340/.477, 22 home runs, 9 triples, 18 steals, 98 runs, 8 outfield assists — are impressive enough. He also walks all over Frazier in the WAR department, at 5.0 overall, 1.4 on defense, and 5.8 on a 162-game basis. His baserunning ought to be marked even higher, but there is no real way to quantify all of the singles he turned into doubles, doubles he turned into triples, and hits he created by hustling down the line. What makes Harper so compelling to me is that he was able to demonstrate his offensive prowess despite being treated by pitchers as though he was Mark McGwire in his prime. According to FanGraphs, using MLB Advanced Media’s PITCHf/x classifications, Harper saw fewer four-seam fastballs as a percentage of his pitches seen (26%) than any hitter in baseball. And the notoriously aggressive Josh Hamilton was also the only hitter who saw fewer pitches in the strike zone than Harper did. The fact that, at 19, Harper was being treated as an elite power hitter speaks to a tremendous amount of respect from his peers. The fact that he could perform despite that obstacle speaks to his tremendous ability. And the unquantifiable energy he brought to a slumping Nationals offense in April is exactly the kind of “x factor” that can’t be captured by sabermetrics. In any case, Harper had the most impressive season by a teenager in decades.

0 notes

Text

Phil Hughes is pitching well: why?

Last summer, I highlighted the major hype surrounding the cut fastball, or "cutter," that swept up the baseball world. It seems to have died down somewhat this year, and for good reason -- it's not a miracle pitch. In particular, I pointed to pitchers developing arm problems from throwing too many cutters -- the prime example being Yankee starter Phil Hughes.

Hughes started throwing the cutter in 2009 and has relied on it heavily both as a starter and in his short tenure in the bullpen. His reliability as a pitcher has varied, including this year. But his last four starts have gone really well -- three of them qualified as quality starts, and three of them netted him wins. The major difference is crystal clear: Hughes has dropped the cutter.

According to Texas Leaguers, Hughes threw the cut fastball about 12.4% of the time in April. Since the beginning of May, it's below 2%. And tonight, Hughes threw zero cutters for the first time in a start since September 24, 2008.

I think the death knell for his cutter came on May 17, his last start against Toronto. His first 26 pitches were fastballs, and he only threw five cutters all game. Two of them resulted in base hits, and the last one Jose Bautista hit 353 feet to left field for a home run.

He hasn't thrown one since.

Hughes has experimented over the years with numerous pitches, including a two-seam fastball and a slider. But perhaps he can succeed with his current repertoire of fastball, 12-6 curveball, and changeup. It's worked so far.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dwight Freeney suckage update

He had zero tackles yet again today, the fifth time this season. Wide receiver Reggie Wayne, with one tackle on an interception return, was more productive.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The amazing Freeney

Colts defensive end Dwight Freeney is such an impact player, he's tied for 86th in the NFL among defensive linemen in tackles (and tied for 387th overall)!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a little observation

Vince Wilfork has more interceptions this season than does Darrelle Revis.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yankee Stadium's foreign inspiration

I've finally realized what the exterior of New Yankee Stadium reminds me of! Of all things, it's Turkmenistan's presidential palace. Behold:

And Yankee Stadium III:

If the Yankees are going to open a facility that caters primarily to the super-wealthy, why not learn from the best plutocrats in the world -- Central Asian dictators!

0 notes

Text

Joe Girardi's little bullpen that could

Ramiro Mendoza

Jeff Nelson

Mike Stanton

Graeme Lloyd

Jason Grimsley

Randy Choate

Chris Hammond

Felix Heredia

Paul Quantrill

Tom Gordon

Tanyon Sturtze

Scott Proctor

Ron Villone

Kyle Farnsworth

Mike Myers

Brian Bruney

Joba Chamberlain

Edwar Ramirez

Jose Veras

David Robertson

Alfredo Aceves

Damaso Marte

Phil Coke

Boone Logan

In case you're wondering, this is a list of the pitchers who have made 50 appearances as a Yankee reliever since 1997. In other words, these are the pitchers who have had some staying power in the Yankee bullpen -- all while the closer has remained the same person. Not exactly a picture of consistency, is it?

That's what makes the Yankees dangerous this year, is that their bullpen is brutally consistent. Officially, the Yankee bullpen's ERA is 3.00. But if you take the ERAs of the guys working in their pen now -- Rivera, Robertson, Ayala, Logan, Hector Noesi, Cory Wade, and post-DL Rafael Soriano -- it is a tiny 2.11. They're blessed to have not just the best closer in Rivera, but also the best setup man in Robertson. That is why Brian Cashman didn't make a deal at the trade deadline.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first class of baseball's Hall of Very Good

Apparently there is an NFL Hall of Very Good, dedicated to those players who had successful careers but fell a little short of the Hall of Fame. (These players must have also retired at least 25 years ago.)

I think baseball would have a sizable Hall of Very Good, with 142 years of professional baseball history to choose from. Just as the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown started with an opening class of five in 1936, the BHoVG should do likewise with these shoo-ins whose careers could easily have led to enshrinement in Cooperstown:

Buck O'Neil -- Buck played in the Negro Leagues from 1937 to 1955, a career .288 hitter who played first base. His most important work in baseball came after his retirement, though. He became the first black coach in MLB history in 1962, signing as a scout for the Chicago Cubs. His work was highly regarded and he signed Hall of Fame outfielder Lou Brock to his first pro contract. In his later years, he became an ambassador for baseball as a whole: he served on the Veterans Committee of the Hall of Fame from 1981-2000 and was instrumental in getting Negro League players inducted. I first knew of him through Ken Burns's Baseball documentary, in which Buck was widely featured. Inexplicably, a 2006 special committee of the Baseball Hall of Fame to select Negro League players passed over O'Neil. The Hall of Very Good will have to do.

Gil Hodges -- A good number of people who played for the Brooklyn/LA Dodgers in the 1950s made it into Cooperstown -- namely, Sandy Koufax, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, and Roy Campanella. One notable exception is Hodges, an eight-time All-Star who hit more home runs (311) and RBI (1001) in the 1950s than anyone except Snider. He was a three-time Gold Glover, as well, and later became a successful manager of the Washington Senators and 1969 World Series-winning New York Mets. The closest he came to enshrinement in the Hall of Fame was 1983, his final year of eligibility, when he garnered 63.4% of the ballots.

Bob Johnson -- A forgotten slugger of Connie Mack's 1930s Philadelphia Athletics, Johnson was a consistent run producer who was also selected to eight All-Star teams. A guy who could hit for average as well as power, Johnson hit over .300 five times and retired with a .296 average. He also hit 20 home runs in a season nine consecutive times and had eight 100-RBI seasons. For his career, he averaged 25 home runs, 34 doubles, eight triples, 108 runs, 112 RBIs, and 93 walks per 162 games. His career OPS ranks 65th all-time. Despite these impressive statistics, Johnson never received serious consideration for Cooperstown.

Carl Mays -- Mays will always be remembered first for being the only pitcher to ever kill a batter with a pitched ball. In 1920, he beaned popular Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman in the head with a fastball; Chapman died hours later. The Chapman incident overshadowed a great pitching career spanning 15 seasons, leading to 207 wins against only 126 losses and a 2.92 career ERA. He led the AL in shutouts and complete games twice, and wins once. He was also a career .268 hitter. The Veterans Committee considered Mays for induction in 2008, but did not select him.

Ron Santo -- The heavy-hitting third baseman had 342 home runs over a 15-year span (1960-1974) during which pitchers generally dominated, reaching the 30-homer plateau in four straight seasons. He won five Gold Glove awards for his fine fielding ability and good range, and he led the National League in walks four times. By coincidence, the legacy of Carl Mays appeared to Santo in 1966, when he became the first player in MLB history to wear a batting helmet with ear flaps. (His cheekbone was broken by a pitch two weeks earlier.) Cub fans will never forgive the BBWAA for neglecting to induct Santo, who Bill James believes is the sixth-best third baseman ever.

#NFL#MLB#Hall of Fame#Hall of Very Good#Buck O'Neil#Gil Hodges#Bob Johnson#Carl Mays#Ron Santo#baseball

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One unusual result of the "shift" being used against Adam Dunn.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statistical anomaly of the day

Red Sox ace Josh Beckett is having a stupendous year -- a 2.07 ERA and only 5.7 hits allowed per 9 innings. According to folk science, the reason for that is because it's an odd-numbered year. Seriously -- check out his performance in the following categories in odd- and even-numbered years (2001-2011):

To put those numbers in perspective, imagine if we extrapolated each of those out for his whole career. Odd-year Beckett would have an ERA similar to future first-ballot Hall-of-Famer Greg Maddux, would be 24th all-time in SO/BB ratio, and would be 10th in career winning percentage. Batters facing Beckett in odd-numbered years would have the slugging ability of White Sox outfielder Juan Pierre -- a fine ballplayer, but pretty much the definition of a contact hitter. (The guy's hit 15 home runs in 12 years.)

On the other hand, even-year Beckett wouldn't even crack the top 1000 in career ERA, would rank 62nd in SO/BB, and would be 470th in winning percentage. If next year follows the trend, Beckett will follow up a possible Cy Young Award-winning 2011 season with a very mediocre 2012 season.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The wonder of Tim Wakefield's knuckleball

Tim Wakefield is baseball's most distinctive pitcher today for a number of reasons. His average pitch speed is only 66 miles per hour. (For reference, teammate Jon Lester's average pitch speed is 88.6 mph.) He's 44 years old and throws exactly as he did when he was 24. And, as I discovered by accident, Wakefield has one of the strangest strike zones in baseball. He consistently gets umpires to call high balls strikes, but has low strikes called balls. Take his performance yesterday against Baltimore:

Using Brooks Baseball's PitchFX tool, I took the graph of Wakefield's pitches and manually removed all the ones at which Oriole batters swung. The pink squares are called strikes, and the green squares are called balls. As you can see, Wakefield threw six balls that were well within the strike zone, but were called balls. Five of these were down in the zone. Conversely, eight balls -- all of them high -- were called strikes.

I was curious if maybe home plate umpire Chris Guccione just had a bad night. But looking at the strike zones of the other pitchers in that game, nothing seemed terribly wrong. And looking back at Wakefield's previous starts, there's a pattern. During Wakefield's June 19 outing against the Milwaukee Brewers, batters only took two low pitches in the strike zone. Both were called balls. Meanwhile, Wakefield got the benefit of nine high strikes that were out of the strike zone.

I also wanted to see if maybe Mets pitcher R.A. Dickey, the only other knuckleballer in the big leagues, experienced this trend. I concluded that, no, his strike zone is pretty similar to everyone else's. And then I noticed one other thing -- Wakefield tends to throw higher in general than other guys. Compare Wakefield and Dickey's knuckleballs to right-handed hitters this season (courtesy of FanGraphs):

Dickey's pitches out of the zone tend to be low, while Wakefield's are almost exclusively high. So this leads to one final question: Did umpires adjust to Wakefield throwing high so often, or did Wakefield adjust to umpires' high strike zones?

Note: This post was originally published on July 19, 2011 at rozenson.tumblr.com.

0 notes

Text

The cut fastball: both sides of the story

The buzz around Major League Baseball these days is the surge of the cut fastball, or cutter. A number of people are attributing an increasing frequency of cut fastballs to the renewed dominance of pitchers across the league. As a fanboy of Mariano Rivera, the maestro of the cutter, I’ve watched closely as it’s starting to be picked up by mainstream sports commentary. As an example, Sports Illustrated dedicated a feature to the pitch in typical mega-hyped style:

There is a mysterious and magical pitch that is changing baseball. The pitch is saving careers, perhaps even extending them, turning journeymen into shutdown relievers and restoring the dominance of aging All-Stars. It’s the secret reason why the game’s power balance has shifted from the hitter to the pitcher. The pitch screams toward the hitter with the speed and the spin of a fastball and on a plane as flat as a vinyl LP and then, just as it begins to cross the plate, the ball darts like a badminton birdie. “Your brain is telling you fastball,” says Angels rightfielder Torii Hunter. “Then the ball breaks, and you’re done.”

The pitch is the cut fastball—the cutter—and it has ignited a quiet revolution, from Philadelphia, where the Phillies’ brotherhood of aces has adopted it as its signature weapon; to Texas, where an overachieving Rangers pitching staff rode the pitch all the way to last year’s World Series; to Anaheim, where a veteran with a waning fastball has taken the pitch and turned himself into a Cy Young candidate virtually overnight. “A couple years ago I didn’t even throw it, and now I have no idea where I’d be without it,” says Angels righthander Dan Haren. “Every pitcher who throws it falls in love with it.”

The pitch is not only why the Yankees’ Mariano Rivera is the greatest closer ever, but also why the reigning NL Cy Young Award winner, Roy Halladay, is having one of his most dominant seasons, at age 34. The pitch is why virtual unknowns such as Cleveland’s Josh Tomlin, St. Louis’s Jaime Garcia and Tampa Bay’s James Shields are blooming into All-Stars—and All-Stars such as Haren, Philadelphia’s Cole Hamels and Boston’s Josh Beckett are as good as, or better than, ever.

It’s pretty silly to call a cutter “mysterious and magical.” Rivera’s thrown it since 1997, and other big stars like Andy Pettitte and Greg Maddux relied on it for years.

Anecdotally, pitchers might be throwing more cutters than ever. But reliable pitch classification data indicates that cutter usage is basically flat over the last few years — between 4.2% and 4.9% of all major league pitches each year from 2007-2010.

In addition, it’s irresponsible for Sports Illustrated not to mention the risks of developing a cut fastball in one’s reportoire. Phil Hughes of the Yankees lost several MPH on his fastball and is on the disabled list, and one writer thinks it’s because he’s throwing so many cutters lately:

Hughes started throwing a cutter a couple of years ago, and relied on it heavily last season.

Over the last several years the cutter has become the in-vogue pitch in the big leagues, a pitch that breaks late mostly because of pressure applied by one or two fingers on the ball. Mariano Rivera, of course, is proof that it’s not necessarily harmful, but pitching coaches say the grip and release is freakishly natural for Rivera, while it can cause strain for many pitchers.

In any case, the point is there’s no guarantee that this is a short-term issue for Hughes. The Yankees are saying it’s “dead-arm” syndrome, fatigue that pitchers typically experience in spring training as they build arm strength. But it’s rare when such a thing lasts more than several days.

If it’s true that the cutter is spreading like wildfire, then pitching coaches need to more closely supervise that process. Otherwise, the pitch that supposedly prolongs the careers of old vets might cut youngsters’ careers short.

Note: This post was originally published on June 19, 2011 at rozenson.tumblr.com.

1 note

·

View note