Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Early to rise: How to vote early in Minnesota in 2022

(This public service announcement is brought to you by Vinny, photographed in 2020 and still thriving in 2022!)

Here's how you can vote safely and early in the November 8 election in Minnesota, where early voting starts Friday, September 23. (See this guide for how to vote in every state.)

1. Request an absentee ballot now. Track your ballot status at MNVotes.org. Voters without email can print out and mail a paper application. Voters in special situations can have a previous acquaintance pick up and deliver a ballot. If you don't have Internet access, call (877) 600-8683 for help.

2. Register to vote now if you haven't. You can register online by Tuesday, October 18, or by mail if your form is received by that date. You can also register in person at your county elections office by Monday, November 7 (and vote early while you're there), or at your polling place on Election Day, Tuesday, November 8. Bring a photo ID and proof of current address to register in person, and any time you vote (in case you need to re-register).

3. Look up your sample ballot. Research the record, policies, and endorsements of the candidates for school board, U.S. congress, district court, state legislature, governor, sheriff, or anything else. Make your "cheat sheet" now for when your ballot arrives.

4. Check your mailbox for your absentee ballot starting Friday, September 23. When it arrives, keep it someplace dry. Don't mark it until you show it to your witness, a Minnesota voter or notary from any state, whose signature is required for your absentee vote to be counted.

5. Vote absentee with your witness present. Before you begin, show your witness that your ballot is blank. Find the three smaller envelopes in the same ballot package, one brownish and two white. Have these ready, along with your "cheat sheet" and your Minnesota state ID or driver's license or social security number, if you have one.

Mark your ballot in private. You can also have an assistant mark it according to your directions. When done, put your ballot in the brownish "Ballot Envelope." Then, before your witness, put the "Ballot Envelope" in the white "Signature Envelope" and seal it. Complete and sign the "Signature Envelope" and have your witness do the same. If the witness is a notary, have them affix a notarization stamp.

6. Mail your ballot using the mail-in envelope. To be counted, your absentee ballot must reach officials by Election Day, Tuesday, November 8. I recommend mailing it Tuesday, October 25. Remember, no added postage is necessary: All Minnesota return envelopes for ballots come prepaid, with an election barcode putting it ahead of other first-class mail.

There are good reasons for confidence in this system: Despite changes slowing the mail in 2020, the U.S. Postal Service successfully delivered the general election that year, and Minnesota allows you to track your ballot online, and cancel it anytime before 5 p.m. on Tuesday, November 1, something you might consider if it's delayed (or if you wish to change your vote).

Even if your ballot is delayed and you miss the November 1 deadline to cancel, you can vote early again in person at your county elections office, or on Election Day at your polling place, just to make sure your vote is counted, because there's no way to accidentally vote twice in Minnesota. For example, if your mail-in ballot were processed while you were standing in line to vote, the system would recognize it, and reject the second ballot.

7. Or, if you prefer, drop off your sealed absentee ballot at any county or city elections office. You can do this between Friday, September 23, and 5 p.m. on Monday, November 7. Again, voters in special situations can have a previous acquaintance pick up and deliver a ballot instead.

Another possibility: Drop off your sealed and witnessed ballot at an outdoor walk-up or drive-through voting station. City elections offices in Duluth and Minneapolis have provided this service before, and may run such stations again, weather and staff permitting, from Friday, November 4, to Monday, November 7.

You can also drop off your sealed and witnessed absentee ballot before 3 p.m. on Election Day, Tuesday, November 8, but be sure to deliver it to the office that sent it to you, not to your polling place, where (if you make this mistake, or even if you don't) you can still vote in person if you're in line before 8 p.m.

8. Track your ballot online to make sure it's been received and counted.

9. If all else fails, vote in person on Tuesday, November 8. Remember that your polling location may have changed from past years. Polls are open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. Consider wearing a mask to reduce spread of COVID-19.

10. Celebrate! Democracy means participation, liberty, equality, and majority rule. Just by participating, you made your community more democratic. That's reason enough to stay up with popcorn!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early to rise: How to vote early in Minnesota

(This public service announcement is brought to you by Vinny, our coronacat, photographed July 26, 2020.)

Here's how you can vote early and safely in the November 3 election in Minnesota, where early voting starts September 18. (See this guide for how to vote in every state.)

1. Request an absentee ballot now. Voters without Internet access can call (877) 600-8683 to get one. Track your ballot status at MNVotes.org.

2. Register to vote if you haven't. Register online by Tuesday, October 13, or at your county elections office by Monday, November 2, or at your polling place on Election Day, Tuesday, November 3.

3. Look up your sample ballot. Research the record, policies, and endorsements of all the candidates for school board, district court, state senate, or anything else. Make your cheat sheet now for when your ballot arrives.

4. Check your mailbox for your ballot starting Friday, September 18, when early voting begins. Keep it someplace dry. If you get it after Tuesday, October 6, consider skipping Step 5.

5. Mail your ballot. While the mail delivery delays are real, they seem to be under control here. Plus, you can track your ballot online and cancel your ballot before 5 p.m. Tuesday, October 20, if it seems to have gotten lost — in other words, if it's taking longer than seven days to arrive, which is well outside the normal first-class timeframe of two-to-five days.

Remember: No added postage is necessary. All Minnesota ballots come ready with first-class postage, plus an election mail barcode that may put it ahead of other first-class mail. For mail-in ballots to be counted, they must be postmarked by November 3 and reach your county by November 10. But the USPS is advising mailing your ballot by Monday, October 19. I'm advising you mail it by Tuesday, October 6.

6. If you prefer, drop off your completed and sealed absentee ballot at any county or city elections office starting Friday, September 18, up until 5 p.m. on Monday, November 2. There are also other options for early in-person voting — Hennepin County has 40-plus locations. Someone can drop off your ballot for you if they don't mind completing some paperwork at the counter. Have them bring their own pen.

7. Or, if you prefer, drop off your completed and sealed absentee ballot at an outdoor voting station, whether walk-up or drive-through. Cities such as Duluth and Minneapolis have offices for elections services that offer these stations if weather permits. Though they haven't announced such stations yet, if they do, it would likely be from Friday, October 30, through Monday, November 2. Again, someone can drop off your ballot for you, but they'll have to complete some paperwork at the station.

8. Track your ballot online to make sure it's been received and counted.

9. If all else fails, vote in person on Tuesday, November 3. Remember that your polling location may have changed from past years to allow for more social distancing.

10. Wait for the election results. They should come in by January 20, 2021.

1 note

·

View note

Text

You send me: Why Minneapolis elected Ilhan Omar for this moment

(Mural by Mohammed "Aerosol" Ali in Birmingham, England, July 2019, painted in "solidarity" with her; photographed by the artist for BBC News.)

Why is my freshman congresswoman being "primaried" in the August 11 election, by a political newcomer who raised six times as much money between April and June, including half a million dollars from big donors favoring conservative policies toward Israel?

You probably already answered that question as near to your satisfaction as you can, if you live in the Fifth District of Minnesota and can vote, or mailed your ballot in anticipation of alleged presidentially-induced delays at the post office.

But if the suspicions raised by this race about either leading candidate remain, like piles of un-recycled mailers, I have a theory as to why: A politics based on the presumption of guilt came to town. It lost, or won, but affected us either way. Because suspicion poisons everything. Without the ability to really test the null hypothesis — the default truth that what you see is a coincidence — belief can be a light out of the darkness, a north star into a black hole, or the sparkle in the eye of a face at the bottom of a well.

So let's talk about what we know. As Rachel Cohen reports in Jewish Currents, the contest here for the Democratic-Farmer-Labor nomination for Congress doesn't seem to be about actual policy differences between the candidates regarding Israel or the Palestinians. Omar and her lead challenger, Antone Melton-Meaux, have the same position on the Boycott Divest Sanctions (BDS) movement, for example, which is really more of a BD movement at this point. Both candidates defend the right to boycott, as Omar did last year with a resolution co-sponsored by John Lewis, a right most federal courts have also upheld, overturning recent anti-BDS laws in three states (though not Minnesota, where Omar argued against the law that passed). Both candidates also oppose BDS strategies, reasoning that they're counterproductive to encouraging negotiations toward a two-state solution. To the same end, they join most Americans in opposing Israel's plan to annex much of the West Bank, though Omar would condition aid against it, and Melton-Meaux would not.

Beyond that consensus, Omar has expressed approval of BDS itself, via a single text message from a campaign aid to the website Muslim Girl in 2018, stating that Omar "supports" the "movement." That message, along with her refusal (on expressly articulated principle) to join the House in condemning BDS, gave reporters license to call her and Lewis's resolution "pro-BDS," and Omar the "face of the movement." On the same narrow basis, Melton-Meaux claimed in April that the congresswoman "supports sanctions on Israel."

People are what they do, and I'm not here to attack Melton-Meaux, who seems to have done good things before writing that astoundingly disingenuous op-ed. But his campaign is about Omar, not him, or rather about someone who isn't really Omar at all, which is the problem. Omar never called for sanctions against Israel or any other country. To the contrary, she has consistently and vocally opposed sanctions, sometimes to a political fault: Her "present" vote on the Armenian genocide was a stand against sanctions on Turkey. Her argument in every case is that sanctions harm people, not governments — which appears to be right, to take the example of Iran. Even her bill to sanction Brunei, for stoning people to death for being LGBTQ, targets the travel and assets of officials, not civilians.

Whatever you think of that position, it's integral with Omar's opposition to arbitrary force or punitive retribution of any kind. She's called for an end to the "cycle of violence" everywhere, whether from undeclared war, terrorism, riots, repression, or criminal justice that metes out more harm, as she sees it. Nine months after being smeared as a coddler of terrorists for writing a judge to ask for leniency in the sentencing of a young man who had not yet taken up arms with Isis, Omar did the same for the middle-aged man convicted of threatening her life. In both cases she asked for a "restorative" approach that would help the person repair himself, not just the community.

With similar trueness, after she and Lewis introduced their "right to participate in boycotts" resolution, Omar spoke of "support" only for "efforts to end the [Israeli] occupation and achieve [a] two-state solution," and argued against condemning BDS on the grounds that "if we are going to condemn violent means of resisting the occupation, we cannot also condemn nonviolent means."

A Somali-born refugee and the first Muslim to wear an hijab in Congress, Omar may recognize better than most how essentialist judgments can thwart a person's autonomy. That she became the media "face" of BDS, while her identically-voting white colleagues of Christian or Jewish heritage did not, is one of many such ironies not lost on her, I imagine. But acting as if some double standards are too contemptible to dignify with an answer, or even an acknowledgment, seems to be part of her armor against them.

(Hugging John Lewis in 2018, in an uncredited photograph posted by the congresswoman this year on his 80th birthday.)

Of all the falsehoods sent sailing like stones at Omar, none bothers me more than the idea that the personal attacks against her didn't happen — that a massive, dangerous smear campaign was just "Twitter fights" with the president, or criticism of her "record." The torrent of Omar fictions began in August of 2018, a week after her primary win, and by July 2019 reached a crescendo of six fake stories per month debunked by Snopes. In the first month of her term, she was accused of defending Isis, based on that letter to a judge, a claim pandering to "sharia" conspiracists like her would-be assassin. In February came unfounded and increasingly dishonest charges of antisemitism, based on Omar's seemingly unwitting use of two antisemitic tropes (hypnotism and money), for which she apologized unequivocally, followed by a third one (dual loyalty), for which she did not, by that point apparently not wishing to enable those seizing on her words to keep changing the subject from what she'd been talking about: the Palestinians, and how any discussion of their treatment is policed out of existence. This time, the charges against her pandered to Christian evangelicals, with the apparent hopeful side-goal of alienating some Jewish voters from her or her party's base. But the criticism of her words was roundly picked up by Democrats, whom Omar joined in the House to vote for a resolution condemning antisemitic language. Only Republicans voted against it.

Then came the video in April shared by the president of the United States, a montage of Omar and 9/11 that aimed far beyond the earlier audiences, this time to falsely link the congresswoman with the worst attack on U.S. soil in history. If the videographer thought Democrats wouldn't defend her, they were wrong. But death threats against Omar increased. April also brought a disinformation campaign about Omar and U.S. and Somali casualties in the Battle of Mogadishu, this time aimed at veterans, whose benefits the congresswoman has consistently voted to keep and expand.

In July came the apotheosis: the president's serial fabrications about Omar on camera and at rallies. He riffed on much of the above, but added the lie that she had expressed "love" for al-Qaeda, that she said al-Qaeda made her "proud," an appalling implicit incitement to violence that Republican leaders mostly played along with. It was, I wrote at the time, "the break with reality that a more fundamental break with humanity requires," in a month of detention center atrocity stories in the news, and with growing numbers of young Jewish activists arrested in front of ICE offices across the country chanting "Never again is now," including here. Trumpists were plugging their ears and going "na-na-na-na-na-na-na" to all this. Which was scary, because a reality war could go anywhere — and that's exactly what it did. The president’s tweet of a video with a September 13 timestamp claiming to show Omar celebrating 9/11 was the same basic impulse that would kill 150,000 Americans in a viral pandemic due to denial, inaction, and corruption.

The warning of a year ago also came after the Poway synagogue shooting in April, which brought home, as Omar and Illinois Representative Jan Schakowsky were early to note, how much antisemitism and Islamophobia had merged on the extremist right. Muslims and Jews had already been grappling with their entangled oppressions for years, partnering on issues like gun violence, as a local group of women did here starting in 2016. Particularly in the wake of the El Paso shooting, the ongoing lying about Omar's immigrant community had a uniting effect outside the president's cult.

(Volunteers sweeping and painting names at the George Floyd memorial in Minneapolis, June 12, 2020; photographed by me with the subjects' permission.)

None of those lies will wash here, where the George Floyd street memorial is a garden of flowers and art six miles north from the Bloomington mosque that was bombed three years ago, in the neighboring Congressional Third District. Contrary to Islamophobic fantasy, the Fifth is 63% white, with an active Jewish left and center, of which many are also on record in support of Omar, including Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey. Given the math of her 2018 landslide, Omar could have won her seat without a single Somali American vote. Her current campaign's internal polling shows an approval rating of 74%.

To supporters I know across demographic categories, Omar is someone there for everyone — and a threat exactly because she challenges leaders who aren't. Like the largest protest movement in American history, which began in her district on May 25 — she puts the moral dilemma of American exclusion, of all exclusion, at the center of politics. Her "radical love" is the inverse of John Lewis's "good trouble," because left humanists have a parent's love of country, not a child's. They hold the world to something better. A month ago, Omar called on reporters to ask state and U.S. senators who were blocking meaningful police reform these questions: "How come you are not listening to the cries of the mothers and the fathers in our communities? How come you are not listening to the people who are telling you that we don't feel like our lives matter equally in this country?'"

I have never seen a U.S. representative host so many town hall meetings on issues important to her poorest and least powerful constituents — two events per month, from one spring to the next. At one, on Black mental health, I watched an audience member literally seek help for herself and her family from the experts onstage. Observing such events, New Hope city councilman Cedrick Frazier wrote that at every meeting with Omar he saw, she "stayed long after the event ended to talk with and answer questions from the people in attendance."

She has also consistently shown up at important protests, not necessarily to speak, but just to be there, as when she went unrecognized in her mask and headscarf at the first, overwhelmingly nonviolent George Floyd protests. She meets regularly with important local activist groups, like MN350 and MIRAC, whose memberships spiked last summer. That increase, beyond our physical proximity to Floyd's life and death, suggests why the movement and unrest happened here as it did. Fifth District residents who took to the streets in response to his killing — (again) overwhelmingly with nonviolence, often numbering in the tens of thousands, and protesting every weekend day for six weeks after the last fires from three nights of riots were out — built on already record-high levels of left activism and organization before the pandemic: for immigrant rights, the climate, and Black lives. It was protesters — medics but also ordinary participants — who used their bodies to shield and rescue all but two souls in the uprising.

This outcome reflected a culture as well as an infrastructure, and it touches everyone. Omar's teenage daughter, Isra Hirsi, helped lead the U.S. chapter and St. Paul march of the global Youth Climate Strike on September 20 — one of the largest international protests before the Floyd marches. Young MN350 volunteers poured into presidential primary campaigns, especially for Omar's friend Bernie Sanders, whose local appeal to voters was headquartered out of her own campaign office. MIRAC's Mari Mansfield painted the long list of names on the street at the George Floyd memorial on 38th and Chicago, of unarmed people of color killed by police. "It's all civil disobedience now," she said, when I lamented missing a MIRAC training on it before the pandemic. The Black Lives Matter protests in every corner of Minnesota will have similar ripple effects going forward.

Omar herself turned her office into a food distribution center after the unrest, and raised hundred of thousands of dollars for local organizations seeking to transform policing. “I saw Ilhan in the streets nearly every single day," wrote Minneapolis city council vice president Andrea Jenkins. “Unbeknown to most of us at the time, Ilhan’s father was in the hospital with COVID-19.” Nur Omar Mohamed’s death was announced on June 16.

(”Close the camps” protesters blocking traffic outside the ICE office at Fort Snelling on July 30, 2019; Youth climate strikers in St. Paul, September 20, 2019; both photographed by me.)

My point is not that Omar is a leader for this moment, but that this moment already elected her two years ago. The congresswoman speaks to both left and humanist values because both of those things are resurgent in mirror opposition to Trump. Like so many of her constituents, but also American leftists more generally, she draws no distinction between appealing to the best in everyone and defending like a sister those left out of that "everyone." "We need to jettison the zero-sum idea that one person's gain is another's loss," she wrote in the Washington Post earlier last month. "I want your gain to be my gain; your loss to be mine, too."

At her police reform press conference, with the Minnesota Legislature's People of Color and Indigenous Caucus, Omar set off another extremist conservative firestorm when she announced that, "We are not merely fighting to tear down the systems of oppression in the criminal justice system. We are fighting to tear down systems of oppression that exist in housing, in education, in healthcare, in employment, in the air we breathe." But that statement is threatening only if you believe, as some Americans apparently do, that "systems of oppression" benefit you.

In her first 19 months in the 116th U.S. Congress, Omar introduced 39 bills, four of which have passed, all amendments. She also succeeded in getting her MEALS Act — providing kids school lunches regardless of whether schools are open in the pandemic — included as part of the CARES Act. You can read the other 34 bills and judge for yourself if there's a wasted effort among them. (She's made a case for each, which is for you to weigh.) But there's something self-fulfilling about claiming a lawmaker doesn't get anything done when you're blocking or ignoring their legislation. Much as the burden of proof is always on the accuser — because you can't prove a negative — I'll leave it to Omar's opponents to make the argument that any of these laws would be bad for the United States: that, no, we should not eliminate fossil fuel subsidies, keep corporations convicted of fraud out of politics, cancel student debt, award grants to zero-waste projects, stop stigmatizing kids unable to pay for school meals, make school lunches free, cut off military aid to human rights abusers, or join the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Similarly, in a pandemic, I'll let them explain why we should not aid small businesses, cancel rent and mortgages, cancel school lunch debt, or move food stamps fully online.

Omar co-sponsored 601 other pieces of legislation, 72 of which passed the House, nine the Senate, and seven into law by the grace of the president's signature. Those dramatically dwindling numbers suggest a political problem that is not Ilhan Omar. She has addressed that problem, whether you agree or disagree with her, by endorsing progressive candidates nationwide, including here in her own district, where she campaigned for Richfield mayor Maria Regan Gonzalez and Crystal city councilperson Brendan Banks. She's also built her Democratic coalition. After the censure from Democrats and the president's attacks on her last year, she made a public show of unity with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who has now endorsed her.

Omar is not the Mother of Dragons some imagine. She's just been through the worst fires of war and politics, and has come out the other side a congresswoman from Minneapolis. Most likely, that's what she'll remain next term.

0 notes

Text

Want to shape your political party? Go caucus on Tuesday. Here's how.

In Minnesota, the primary election is Tuesday, March 3, 7 a.m. to 8 p.m.—Super Tuesday. That's when you can vote to choose a party nominee for president. (You can also vote early, up to the day before.)

But your local precinct caucus is a week earlier, Tuesday, February 25, 7 p.m. to 10 p.m., with doors open at 6 p.m. Why go to the caucus if there's a primary a week later? Because the caucus is where you can help write the party platform. You can also volunteer to become a precinct delegate, and more.

What follows is a basic how-to for Tuesday caucus night, regardless of the party you're influencing. I mostly cribbed this from the Northstar Chapter of the Sierra Club. Party links and resolutions are below.

Find your caucus:

Caucusfinder.sos.state.mn.us

Goals for caucus night:

Volunteer to become a delegate.

Introduce a resolution, or more than one of them.

Becoming a delegate gives you another voice and vote on your resolution later, at the organizing unit convention. From there, you can approve resolutions and elect delegates for the district, state, and national conventions to be held over the next five months. Caucuses are the first step to representing your state at that convention this summer. In parallel, you can become a delegate for your county, to endorse county-level candidates.

Before the caucus:

1. Prepare your resolution. Between now and Tuesday, print out one or more of the resolutions linked below. Use this as a model, or just introduce it as your own. Follow this format:

"Whereas...

"Whereas...

"Whereas...

"Be it resolved that the ____ party supports ________."

Practice reading it, and think about your personal reasons for endorsing it. Also come up with questions for local candidates about the issue.

2. Amplify your impact. Post on social media about your caucusing ahead of time using hashtags for your cause—e.g. #CaucusForClimate. Wear buttons. For the climate issue, you can pick up buttons Monday at TakeAction Minnesota, 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., 705 Raymond Ave. #100, St. Paul, MN 55114. Invite 10 people to caucus.

3. Get there early on Tuesday. Eat beforehand and leave travel and parking time. Introduce yourself to the caucus chair and mingle. Get to know some of your neighbors who are politically involved. These are your potential allies for passing your resolution.

Caucus schedule:

6 p.m. door

7 p.m. start

Party business and rules

Candidate pitches

Electing delegates

Introducing resolutions

Candidate pitches:

These can happen at any time. Candidates come in, participants drop everything and listen. Ask direct questions about your issue or resolution.

Become a delegate:

Check your availability. The organizing unit convention is usually on a whole weekend day. Volunteer only if you can make it. Open your calendar and be ready.

Raise your hand.

Share why you want to be a delegate. Keep it concise. Be real. If you haven't been one before, say so. "I'd be a great delegate because I represent the voice of..."

Get your name on the list. Make sure your name is on the list at the end, because that's what's handed by the chair to the convention.

You can also be an alternate.

Introduce your resolution.

Raise your hand.

Read your resolution. Bring it on paper to read it. Stand up by your chair, or go to the front.

Listen. The room will offer up to 3 statements in support or against.

If you get a question, remember: You don't need to have all the answers. Say why your values align with the issue.

Hand in your resolution.

Vote with ayes and nays. Either the resolution passes or doesn't.

FAQ:

How many resolutions can we introduce? As many as you want. But if everyone comes with a stack of resolutions, the chair may just let you introduce one.

How can we track the progress of resolutions beyond the precinct level? I'm still working on getting an answer to this.

Can we caucus at any political party we choose? Yes, if you affirm that you align with the party's values.

Can we caucus for more than one party in the same night? No, you need to choose one party to caucus.

Can I participate without attending? Yes. Emailed absentee forms were due Saturday, but you can drop off, or have someone drop off, an absentee form and resolutions in person—see links below.

Party caucus links:

https://www.dfl.org/caucuses-conventions/precinct-caucus/

https://mngop.com/caucus2020/

https://www.sos.state.mn.us/elections-voting/how-elections-work/political-parties/

DFL non-attendee form: https://www.dfl.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Precinct-Caucus-Non-Attendee-Form-2019-09-24_Call_FINAL_Rev_A_adopted_21_September_2_003_1-1.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2EF03ZI25pHIUnxbSC_Wj42txrt-Y56hl90xaGpG3rUwbgNoSn2e5suY8

Resolutions to introduce, whatever party you're caucusing for:

Ranked-choice voting: https://www.fairvotemn.org/event/rcv-precinct-caucuses

MN350 Green New Deal resolution: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1tqbOzBfT1kOGdbZdikIUq3Fjd5Y5V8-k1-4i2s2h8WY/edit?usp=sharing

DFL Environmental Caucus resolutions: https://www.dflec.org/resolutions

Education Minnesota resolutions: https://educationminnesota.org/EDMN/media/edmn-files/advocacy/election%202020/2020-Precinct-Caucus-Guide.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1MFdrenl1ajS4WGypjIc_AMwmLQB9RuedVuIHiOv9_umYGkGwdHqvrtTs

100% clean energy: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1jzsn0Akj7_xBt7dbJcdCSNIfazlN34YhrJVzIFCnt7w/edit?usp=sharing

Clean transportation: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v_CRU9ik_iD6gjYeYEQd8WkGUwejmF2XTOAkFEKbcKw/edit?usp=sharing

Stop Line 3: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iP31-HX-GQIoaNlM1Nc9df0tF5WKqNkr4GUfcVxcmUk/edit?usp=sharing

Various Minnesota Voice democracy platform resolutions: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0ByQpX2PKmtozZjNpdHNlMFlkMlE/view?usp=sharing

Single-use plastic: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1YwwcGx97fSYNT0aqrEEvISvqs_YmZtGiAyC7BGoWJ7E/edit?usp=sharing

MN350 video about caucusing: https://vidmails.com/v/Pgqs2Pit8D

Video on fully funding Minnesota schools (in Education Minnesota resolutions above): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPyAtuXdgB0

For the Stop Line 3 resolution, you can add the following:

According to the Minnesota Department of Commerce, the proposed Line 3 expansion doubles the old oil pipeline's capacity and triples its carbon pollution.

That's because the new Line 3 would (a) make heavy tar sands crude oil massively more available to the global market and (b) reroute the current light crude oil running through it to other lines.

As a result, the added greenhouse gas impact from the Line 3 expansion would be more than the entire state of Minnesota emitted in 2016, and five times what our state expects to emit in 2050.

For details, see this report released by a coalition of 13 groups: https://mn350.org/giant-step-backward/

Early voting regardless of the caucus:

https://www.sos.state.mn.us/elections-voting/other-ways-to-vote/

Election day voting regardless of the caucus:

https://www.sos.state.mn.us/elections-voting/election-day-voting/

0 notes

Text

Things I learned from our kitten, Alex.

Get up right away.

Get up when your people get up.

Sleep more later if you need to.

Play every morning, afternoon, and evening.

Play when you get up and before you go to bed.

Play until you are out of breath.

Chase your people when they’re up for it.

Ask your people to play.

Catch air.

Wiggle your butt as you stalk and prepare to pounce.

Shoot yourself through tunnels.

Test your strength.

Drag things many times your size.

Hide things in your people’s shoes.

Remember your family, but love the people you’re with.

Look at the people you love.

Look at them for no reason other than to look at them.

Close your eyes when you’re happy.

Show the people you love that you love them.

Do this first thing every morning and last thing every night.

Connect physically with your people.

Give them a nose kiss.

Put your hand on them meaningfully.

Lick their hand.

Sit on them.

Hug them.

Rub your scent on your territory.

Relax when you have company by flopping on the floor.

Make every surface your bed.

Find the highest point in any room and look down on everything.

Jump even when it’s difficult. You may be stronger now.

Find dark, closed-in spaces and crawl into them.

Go to these spaces when you need them for comfort.

Look out the window at the yard.

Look for your animal friend outside.

Go outside for fresh air every morning, afternoon, and evening.

Go outside before meals and before bed.

Smell the air.

Smell where others have been.

Look around and listen.

Talk to your people.

When you need something, ask.

Explore a new frontier every day.

Learn to do new things every day.

Find new ways to play with your things.

Try the new thing your person wants to try.

Ask your person to try new things they hadn’t thought of.

Smell the flowers.

Eat the flowers.

Throw up when you need to.

Throw up in threes.

Accept gifts with excitement.

Sleep on your gifts.

Listen to guidance.

Don’t listen to guidance.

Bite for fun, but gently.

Lick the hand you bite.

Be a fierce beast, but remember it’s just play.

Trot out when your people come home.

Flop in the arms of your visiting friend.

Celebrate every meal by rubbing up against the cook and spinning around in a circle.

Watch and lick your lips as your people make you your meal.

Eat your food and then wash your hands.

Give people space but check in on them.

Comfort your people when they are down.

When enough is enough, separate your people from their computer.

Ask to be brushed.

Purr loudly when you are brushed.

Cuddle.

Bathe before bed.

Play with water.

Sleep with your people.

Sleep near them.

Check in with your people before you sleep somewhere else.

Touch hands before you go to sleep.

0 notes

Text

Here’s to life

At 90, Jazz Legend Irv Williams Is on a Roll

By Peter S. Scholtes (from Metro Magazine, 2010; photo from WBSS)

On his first night in Minneapolis, in 1942, Irv Williams walked from the train station to the Nicollet Motel, where he was told there were no more rooms. He tried the Andrews Hotel, where they wouldn't let him in. Noting his Navy uniform, a stranger offered to help, vouching for him at the nearby YMCA. Williams checked his small case, and went for a walk, looking for other black folks. It was Saturday night in August, and he had not seen a one.

Eventually, he met a black couple, who told him about a nice club, the Elks Rendezvous, near Lyndale and Sixth Avenue North. Williams caught a cab, which arrived in the cul-de-sac of an old mansion on a hill. Inside was a big dance floor with a few people dancing, and a band playing on a bandstand. "You a musician?" asked the trumpet player, Rook Ganz, seeing the insignia on Williams's shoulder. "Where's your horn?"

Williams had been transferred as part of the Navy band, and his tenor saxophone, like his sleeping bag, was still in transit. "Wait a minute," said the trumpeter. Then the sax player, Howard Walker—they called him Rail—came over and asked Williams to sit in. "Man, I don't have any diseases," he said, "but I got an extra mouthpiece that I very seldom use."

The reed was soft, much softer than Williams was used to. But he played. And everybody thought it was... "wow."

"So I was inducted into the Twin City black community my first night," says Williams, telling the story now. "They showed me a good time. I met some ladies."

The bass player, Oscar Pettiford, befriended Williams before going on soon after to play with Woody Herman and Duke Ellington. Williams and some of the other Navy musicians made the Elks Rendezvous their occasional hangout, heading over with their horns on Saturday nights after playing the USO Club above the State Theatre. Once they got off, they had liberty until Monday morning, and some of the guys didn't make it back.

____

Sixty-eight years later, Williams is playing happy hour at the Dakota on Nicollet, where a drink, Mr. Smooth (Crown Royal, sour, griottine cherries) has been named for him. His breathy tone is as easy as thought, his improvisation as lyrical as something he's been waiting to say all his life.

His hand shakes a little when he changes his reed during a solo by his partner, piano player Peter Schimke. The song is "In a Sentimental Mood," and Williams, sitting in a brown turtleneck and jacket, white-haired and round glasses, taps his foot straight through.

Williams celebrated his 90th birthday last year at the Dakota and the Artists' Quarter, surrounded by friends, family, and the jazz community that reveres him. After the war, he rounded up his old Navy seven-piece and returned with them to Minneapolis and the Elks Rendezvous. His kind of jazz, what the Pettiford family had played, was a smaller world here than in St. Louis, where he had heard Charlie Parker at the Comet Theatre and played in Dewey Jackson's band, jamming in nearby Brooklyn, Illinois—the all-black meatpacking town—with Clark Terry and Miles Davis. ("Shorty," Davis said to Williams when they ran into each other in Harlem in the '50s, "you were one of my heroes.")

But Williams made his home in Minnesota, returning after tours with Ella Fitzgerald and Horace Henderson, and after recording with Dinah Washington. He married twice and had nine children, with 17 grandchildren, their pictures adorning the walls of his Lowertown apartment in St. Paul, along with plaques for community service in music education.

When Williams plays, there's no shaking. His Dakota gig is weekly: Like Kico Rangel and Cornbread Harris, two other local musicians at it since the '50s, Williams keeps working. But playing can be a strain. He has glaucoma and prostate cancer. One afternoon, he lifts the miniature Schnauzer he walks four times a day, Ditto, off his lap to go find a piece of paper, and comes back with a blood test listing his cancer stage as "final."

He repeats the word and laughs. Williams called his last album, in 2007, Finality, announcing in the liner notes that it would be his final recording. But I'd heard this from Williams before, after 2001's Stop Look and Listen, his first release to feature one of his original compositions. Williams went on to make four more albums in four years, starting with 2004's aptly titled That's All? (issued, like all his CDs, on his own Ding-Dong Music label). The best among these might be 2006's Duo, which consists only of Williams and Schimke, and opens with the achingly emotional "Betsi's Song," which Williams wrote for one of his daughters.

The tone on that album is so intimate, you might miss the music's sophistication. "Irv is best known for his work playing from the Great American Songbook," says Schimke. "But even in a traditional setting, he has this uncanny ability to navigate in and out of the harmony."

And, sure enough, Williams is at work on a new album, rewriting some charts before bringing them to longtime bassist Billy Peterson for rehearsal. There are originals among them, and, for the first time, he plans to sing a few. "Too Early for Memories," is about Alzheimer's, he says, singing the opening line: "Grandma doesn't know me anymore." When I ask Williams if he has known anyone who went down that path, he answers, "Have I ever."

Williams says his style hasn't changed much over the decades. "Technically I've tried to get better," he says, "but I don't want to lose the central part of my playing by getting too technical."

When he finishes a song at the Dakota, he'll typically add a little blat or two at the end, sort of an announcement of, "I'm done." "It's just for fun," he says, laughing. "Everybody thinks it's funny. And nobody else can do it on the saxophone." Williams doesn't take endings too seriously.

[original end note] Irv Williams performs Fridays at the Dakota Jazz Club & Restaurant from 4:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m.

0 notes

Text

Best movies of the Trump era

Following up on my Top 30 TV shows of the past year and a half, here's my Top 20 films of the same period. Considerably less informed, but, given what I've seen from the top of box-office or critics' lists, that may be a mercy.

Moonlight All of us raise all our children. (2016)

A Man Called Ove The politics of not giving up. (2015)

I Am Not Your Negro Lends the power of editing to James Baldwin's insight that displaced shame generates racism, and vice versa—one measure of the man being that he delivered this prophesy with sadness. (2016)

Let's Get the Rhythm Girls' handclapping games as the secret of life. (short documentary)

Jane War, dreams, and cooperation among mammals.

Get Out As pulpy, pessimistic, and inelegant as so much horror. But the sinking-into-dark scene brings an old feeling to the screen for the first time, and for all time.

Trolls First emotional antidote to Trumpism. (2016)

Barry Tackling the same subject as Get Out, but with a disappointed optimism embodied by the New York that made hip hop.

Spider-Man: Homecoming Refreshing humor and affection for young people.

I Don't Feel at Home in This World Anymore Cathartic prosocial comedy.

The Post Businesses need consciences too.

Allied Caring for each other as anti-fascist thriller. (2016)

The Zookeeper's Wife Caring for animals as anti-fascist thriller.

Gifted Family is whom you love.

Wonder Cool teachers help.

Thor: Ragnarok Doctor Strange Marvel movies get less strenuous, more lovely. (Doctor Strange from 2016)

The Big Sick American hospital waiting room humor and romance, just this side of cynical.

The Incredible Jessica James If sex-positivity, learning to teach, and making good use of Chris O'Dowd is the new formula, I'll take it.

The Lego Batman Movie Best Batman, and the only sign of life from DC.

Easy to lose your bearings in this era (honorable mentions): The Little Prince (2015) (You've got to want to be moved, but James Franco’s fox is for the ages.) Murder on the Orient Express (As inconsequential as a fine mustache.) Our Souls at Night (Grandparent romance.) Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Rebuke of the essentialism that swallowed a franchise.) Logan (See above.) Snatched (Because Amy Schumer.) Winter River (Snowy, anti-corporate rez whodunnit at least has atmosphere.) Brawl in Cell Block 99, Shot Caller, Logan Lucky (Prison and heist thrillers as class destiny—the third one less gory, and with a good soundtrack.) The Polka King (Optimism as a con—but sides with the con anyway.) Viceroy's House (History was even worse, but any anti-partition movie is welcome.) Me Before You (2016), The Leisure Seeker (Wish these expressions of love did not endorse suicide over care.)

0 notes

Text

Best TV of the Trump Era

My Top 30 television shows of the past year and a half:

Halt and Catch Fire Family is the love you have when dreams die, and where new ones grow.

Game of Thrones The belief that people can change pitted against the end of the story.

Stranger Things 2 Like every '80s sleepover movie ever melded into one primer on how to be a person—friend, babysitter, parent, pet owner.

GLOW Pro wrestling "let's put on a show" as feminist revolution, with Marc Maron finding his perfect Judy Garland in Alison Brie, who plays like Shelley Long fronting a punk band.

Schitt's Creek Where to begin to understand young people.

The Handmaid's Tale Dystopia as a way of clarifying where things are going.

Better Call Saul Visual storytelling from a stranded past.

The Night Of... Dread leavened by a love of sound design, human connection, and the Bill of Rights.

Conan (Conan in Haiti, Conan in Israel specials) I Love You, America (With Sarah Silverman) Love is funnier and more subversive than derision.

Star Trek: Discovery Madam Secretary The Tick Heroes for our times.

Black Mirror Dystopia as a way of clarifying where things are.

The Deuce American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson History told in the close-up of relationships.

Veep Curb Your Enthusiasm The smallness of Seinfeld made radical, humane, vulgar, and sex-positive.

For the People Surprisingly witty, sexy, and principled district court procedural, deeper than its powdered surface.

The Walking Dead Get busy living. (Would be higher if not for losing its conviction at the end of Season 7.)

Orange Is the New Black TV's racial awakening keeps getting deeper.

The Looming Tower Evil is made, not born.

Breaking the News on KARE 11 For once, an actual liberal media, but one that gives breathing space to viewer disagreement.

Maria Bamford: Old Baby Maron Lifelong learners.

Victoria The frivolity you expect with the significance you don't.

Love You More Master of None Love Insecure Romantic comedy living down its past.

Easy to lose your bearings in this era (honorable mentions): Westworld (Dystopia as a way of clarifying how we got here.) The Crossing (The present as utopia compared to a preventable future.) Barry (Empathy for narcissism as sweet as Bill Hader’s voice.) Lady Dynamite (Drop-off in second season as hard to explain as the brilliance of the first.) Mindhunter (Psychologists and researchers as heroes. If only it were about something other than serial killers!) The Joel McHale Show (A shattered nation longs to care about stupid bullshit again.) Young Sheldon (Probably a sign of progress. For watching with my mother-in-law.) The Opposition with Jordan Klepper (Know your enemy as well as love them.) Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (Doesn’t quite have the visuals to match its songs, or the tunes to match its lyrics, but what lyrics!) Difficult People (Lots of laughs, not quite a rhythm, but the surreal political nightmare that kept peaking through was classic.) Portlandia Saturday Night Live (Great satire of Trump, or anything else, would require not sharing his extrinsic values—obsession with looks, success, intelligence, popularity, competition, etc.—which SNL increasingly has since David S. Pumpkins, while remaining as forward-looking on race and sexuality.) Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (See above.) The Daily Show with Trevor Noah (See above.) Sherlock Bojack Horseman (Lost me when it went underwater.) The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (Deeper and less explicable drop-off than Lady Dynamite.) Daredevil (First season.) Luke Cage (Early episodes.)

Comfort in reruns (or just memories and recommendations): The IT Crowd In Treatment (John Mahoney R.I.P.) Show Me a Hero Inside Amy Schumer Moone Boy Friday Night Lights Last Tango in Halifax The Sopranos Parenthood The Muppets Girls Homeland w/ Bob and David Arrested Development Hell on Wheels Death in Paradise The Wire

0 notes

Text

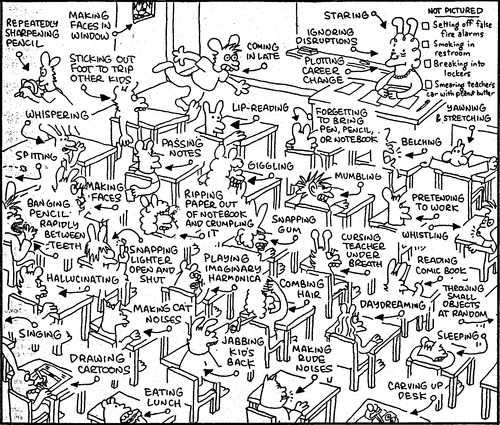

Notes on Jones's 3rd Edition and cooperative learning.

As I hope is clear from my Fred Jones essay, not all "group work" is cooperative learning. Even CL with the crucial elements of positive interdependence and individual accountability can be misused, and each strategy has its own learning curve, often with skills that require coaching. The same principle applies to any other unconventional teaching method, including project-based learning (PBL). It only stands to reason that the less traditional a technique is, the longer it will take for best practices to spread. More important, CL and PBL are only as good as the discipline structure and incentive system you have in place to support them.

So it's distressing to find Jones not acknowledging any of this in the third (electronic) edition of Tools for Teaching (2014), where he dismisses cooperative learning with a single paragraph in Chapter 1, writing that it "results in a lot of chit-chat without anyone working too hard--except for the high achiever of the group who does the assignment for everyone else." At the risk of stating the obvious, this is an example of a badly taught cooperative group lesson. (At least Jones hasn't excised all references to cooperative groups from the 2007 second edition.)

Cooperative learning has been around for decades. Couldn't Jones have taken a minute to study how "natural" cooperative learning teachers use it? Many of these teachers already apply his techniques of motivation and discipline to CL--for instance, using preferred activity time for groups when all members show mastery. Teachers who simply hand out worksheets, let students "work with partners," and hope for the best are probably the same ones who would be less adept at motivation and discipline anyway. Isn't this problem at least part of the story behind the relative success or failure of seemingly more "democratic" and "autonomous" methods?

So comparing cooperative learning to (say) direct instruction is inherently misleading. I imagine cooperative learning could be more widely abused because the hazardous, watered-down version of CL is easier to apply. But if you decide to ride a bicycle, the way to get there safely is to wear a helmet and learn to use the brakes, not conclude that walking is always better. It's a sign of the charged and remote state of thinking on teaching that the best known advocate for cooperative learning (Alfie Kohn) rejects incentives, the best known defender of teachers unions (Diane Ravitch) thinks discipline is a cultural problem, and the best known teacher of positive discipline (Jones) now rejects cooperative learning.

In his third edition, Jones rightly sees John Hattie's landmark book Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement as a justification of sorts for the approach he recommends to "say, see, do" teaching, but goes on to frame Hattie's findings as a rejection of cooperative learning and other more peer-driven methods. [*Note from 2019: Since writing this five years ago, I have read this 2018 critique of Hattie by Robert Slavin, the great education researcher, who calls into question the basic math behind Hattie’s theory. I still think Hattie seems like an excellent teacher himself, with a compelling explanation of why students learn better with teachers. But he may have built his house on sand.] I'd be skeptical of this meta-meta-analysis even if Jones represented Hattie's findings fairly: For one thing, any study, as Jones suggests, necessarily accounts for students who go "backwards" amid the misuse of strategies (those who fall off the bike without a helmet). All you have to do is watch a great teacher use cooperative groups to see all students, including outliers, increase achievement when it's done well.

But Jones invents his own categories of "Large," "Medium," "Small," and "No improvement" to summarize Hattie's findings as follows (I've omitted some approaches for space), when it comes to the "effect size" of different teaching methods on student improvement:

Large. Teaching approaches that show "large" "significant improvement" include (to paraphrase Jones quoting the book):

Frequent feedback between teacher and student.

Spaced practice as opposed to massed practice.

Formative evaluation.

(and in the more innovative realm...)

Reciprocal teaching (summarizing, questioning, clarifying, and predicting possible outcomes as a means of solving problems).

Comprehensive interventions for learning disabled students.

Medium. Those that show "medium" improvement include:

Meta-cognitive strategies.

Self-verbalization.

(and in the less traditional realm...)

The teaching of systematic problem solving.

Small. Those that show "small" improvement include:

Study skills.

Concept mapping.

Worked examples.

Peer tutoring.

(and in the online realm...)

Direct instruction on video.

No improvement. Those that show no improvement include:

Frequent testing.

Matching style of learning.

(and in the less traditional realm)

Cooperative learning.

Computer assisted instruction.

Inquiry based teaching.

Net loss. Those that show a "net loss" of improvement include:

Individualized instruction.

Teaching test taking skills.

Mentoring by older students.

Increased homework.

Competitive learning.

(and on the innovative side)

Student control over learning.

Problem based learning.

Distance learning.

Team teaching.

Home-school programs.

Web-based learning.

Bizarrely, Jones moves Hattie's goal posts to create those tiers--admitting that "Due to the way findings fall into clusters, I will stretch Dr. Hattie's cut point" for significant improvement from a deviation of 0.40 to 0.45--which has the effect of bumping cooperative learning (in its lowest effect size, 0.41, when compared to heterogeneous classes) out of Hattie's "zone of desired effects" and even out of Jones's own made-up "small" category and into his own made-up "no improvement" category (Hattie, p. 212). Did Jones think no one would notice? And can he be unaware that Hattie is a proponent of cooperative learning?

To clarify, Hattie's own categories put anything above a deviation of 0.40 as "above average" and "desired," which would include cooperative versus heterogeneous learning (0.41) (Hattie, p. 17). For Hattie, anything above a deviation of 0.60 is "excellent" which nearly includes cooperative versus competitive learning (0.54) and cooperative versus individualistic learning (0.59, the same effect size as direct instruction, by the way) (Visible Learning, p. 17), 212). Both of the latter effect sizes would put cooperative learning in Jones's own "small" range--if he included them. (For reference, the Johnsons found an effect size of 0.64 in a 2002 meta-analysis comparing cooperative to individualistic learning.) As Hattie writes, "There seems a universal agreement that cooperative learning is effective, especially when contrasted with competitive and individualistic learning" (Hattie, p. 212).

Jones also misreads Hattie to claim that an improvement of 0.40 is "roughly what you might expect from a typical kid sitting in a typical classroom for a year." To the contrary, as Hattie writes, "0.40 does not mean that this is the typical effect of teaching or teachers," because "In most studies summarized in this book, there is a deliberate attempt to change, improve, plan, modify, and innovate" (Hattie, p. 17). (In 2006's Reading Educational Research, Gerald W. Bracey writes that "generally, effect sizes between +0.20 and +0.30 are where most people think an ES has practical ramifications. For example, if we could find an instructional treatment that produced an effect size of +0.30 in achievement for African Americans three years in a row versus some more traditional instructional treatment, we would come very close to wiping out the black-white achievement gap"; Bracey, p. 73.)

Jones is right to cite the hidden opportunity costs of using one just-okay strategy to displace a better strategy, and the effect size of cooperative learning does seem small next to, say, frequent feedback. But this may be a measure of feedback's comparatively smaller bicycle helmet problem. And feedback with monitoring is an essential feature of effective cooperative learning! Even project-based learning can be effective when highly mediated by teachers and peers--as in Hattie's example of teaching cliff rescues, which sounds a lot like the best PBL (Hattie, p. 25).

As Robert J. Marzanno points out, the wrinkle of these broad categories of strategy is they include a range of use from good to bad. An "examination of the research on feedback," Marzanno writes, "indicates that even this 'very high yield strategy' doesn't always work to enhance student achievement," as Kluger and DeNisi found in 1996, showing that 30% of 607 studies on feedback showed a "negative effect." For me, seeing online learning, older-student mentoring, and something as vague as "student control over learning" near the bottom of Hattie's scale just reminds me that these strategies are in their infancy. The bottom line should be "what works when done right," not "what works most commonly." This is inevitably a judgment, and, as Gerald W. Bracey writes, "There is no escape from using judgment" (Reading Educational Research, 2006, p. 72).

Of course, there's nothing rash in telling beginning teachers that some methods can be misused: Jones takes care to do the same with his own strategies. But it's hasty to lump cooperative learning in with results that, according to him, "show that minimal guidance doesn't work" or "that students construct meaning much more efficiently when the teacher plays an active rather than a passive role in structuring the learning experience and providing feedback." Why can't a teacher be active while students are also active with each other?

Guidance in learning is hardly a zero sum game, as Jones himself demonstrates. In his fine new passages on the neuroscience of practice, drawing on Daniel Coyle's The Talent Code in the new Chapter 20 for Tools for Teaching, Jones vividly describes the "attentive repetition" required to learn a new skill, which "only comes from wanting something badly." He cites role models, a culture of achievement, and extensive play as fuel for this jet in young learners--but the play element may be the most crucial. At a certain point, Jones writes of Brazilian soccer, "the coach is no longer teaching the game. The game is teaching the game," with "instant feedback provided by the game itself." Having drilled certain skills and knowledge to perfection, the coach can sit back. He "plays a relatively passive role. It could not be otherwise because of the speed of play."

Jones may not know it, but he's describing cooperative learning--and I'd argue that the Brazilian coach isn't as passive as he seems. When students are applying already-mastered knowledge in ways that are inherently open-ended or complex, increased interaction with peers is the stuff of real, higher-order learning, and is always subtly guided. The impression Jones might have of alternatives to direct instruction is a teacher hiding behind his desk. But the reality of effective CL and PBL is always a teacher closely monitoring the proceedings and frequently intervening.

I don't wish to pursue CL or PBL as dogma any more than I want to denigrate direct instruction, which can also be hugely effective (and can also be misused, as I've seen first-hand). But can considerations of discipline and general teacher effectiveness ever be separated from findings such as Project Follow Through's ten-year study (cited by Jones citing Hattie) showing that direct instruction works best for "disadvantaged students"? Jones would be more persuasive if he at least acknowledged that the spectrum of effective teaching isn't a spectrum at all, something that implies one dimension, but instead a multi-dimensional, interconnected system. As I've learned from Jones, teaching is more like a game: complex, interlocking, and always involving interaction in a group.

Posts and essays in this series:

How to keep school from Dumbing Us Down.

Why classrooms aren't communities.

What, me motivate? Part I

School and the Law of the Jungle

Teaching or violence?

Lesson plan template (January, 2014)

What, me motivate? Part II

What, me motivate? Part III

Authority and freedom revisited: John Locke and A.S. Neill

Notes on Jones's 3rd Edition and cooperative learning

1 note

·

View note

Text

Giving or taking over?

One: The law of death or glory. I don't know you, but I'm guessing your oppression was not overturned last night. You may have a good idea of what ending that oppression would feel like, whether it's a revolution, passing a new law, or getting a new job. For most people, I imagine, that thing didn't happen. For radicals, a revolution would involve some kind of "structural change" in the world, though they disagree about what this means. Maybe it comes down to the whole world getting a new job. But that it didn't happen, either.

Or did it? Writing last month about teaching and violence, I proposed an idea so unusual, and yet so inescapable, that I'm still wrapping my head around it: that movements to change the world, short of outright military campaigns, are, and always have always been, about teaching rather than fighting. The idea applies to revolutions themselves, which aren't just about power changing hands, but hands changing power. To the extent that movements involve confrontation, these confrontations always teach, and hold out the possibility for reconciliation. Without this element, all battles are war, suicide, or both: the logic of Kaiser Soze killing his family to win (in 1995's The Usual Suspects, where the villain showed "these men of will what will really was").

I followed this idea to its logical, more bewildering conclusion: that there are parallels between movements confronting uncooperative power and teachers confronting uncooperative students. The connection goes unseen because the skills of effective teaching--"say, see, do" lessons, giving incentives, cooperative groups, and "meaning business"--are obscure. Most people still think you can punish children into learning. We see authority as something taken, not given. And the very idea of giving is distorted where metaphors of competition, battle, commerce, and retribution dominate. This vocabulary is all some of us have. But we diminish ourselves by thinking we win affection, fight for good, pay it forward, teach somebody a lesson, and are rewarded for our efforts. Language insists we don't give anything, including a crap.

This blindness, I've argued, stems from an oppression that comes from within, a false and corrupting ideology that has no common name, so I call it the Law of the Jungle (Kipling's original idea narrowed to its crude common usage). Here is a toxin that poisons even the ideas of movements that would end oppression, benefitting all illegitimate authority. So the new left of 1962, taking shape at the Port Huron convention of Students for a Democratic Society, began as a community "both 'fraternal and competitive,'" according to participant Paul Potter, quoted by Sara Evans in Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement & the New Left (1980, p. 113). But "As SDS grew, community suffered and competition heightened" (p. 113). As ruthless arrogance grew thick, the movement marginalized women and damaged men, who "felt inadequate and 'put down'" (p. 154).

In the sexual revolution that followed, men and women could embrace what David Thomson calls "the modern itch, the movie urge" to have everyone, like any moviegoer, "less inclined to fix upon the means of choice in love and marriage than yield to the parade of dreams that are more likely to become glamorous and sexual" (The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood, 2004, p. 217-218). A generation raised on movies attached itself "to a medium which in its deepest being urges detachment," Thomson writes, or danced to songs of love at first sight (p. 218). Starting out as the narcissists they revealed in song and unlearning the Law to become better people was part of the drama and evolution of the Beatles.

The Law is obsessed with winning, fighting, having, or dying--"death or glory," as the Clash sang in 1979. It has little use for compromise, real controversy, cooperation among differing views, or admitting weakness. Which is why many radicals favor consensus over pluralism--at best synthesizing opposing perspectives, at worst cutting away opposition--while equating revolution with cathartic violence. "Are you taking orders, or are you taking over?" the Clash sang two years earlier, in empathy with riot--the moment when a third option between taking orders and taking over seems impossible, before the realization that you're doing neither sets in. But the drama and evolution of the Clash was their half-conscious realization that revolutionary romanticism is another Hollywood cowboy or soldier story. Even the supposed arrival of the left counterculture to the big screen in the 1970s was really the Law blended with wary irony, where The Godfather (1972) and its sequel (1974) bound the audience to Michael Corleone's cool view of enemies, his calculation that Cuban rebels are admirable because they fight to the death, and so they can win. Michael punishes underlings, family, and government to death because that's the only card he has.

The better teacher was McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), the class clown as instinctive Yippie (or early Sex Pistol). But even there, Jack Nicholson's willfulness was meant only for death or glory (or escape), not change. As a middle-school kid in the early '80s, I drew and published a cartoon of a rebellious student who turned into a jungle-cat superhero and attacked his teacher--a likeness of my own teacher at the time. To be honest, I didn't know what I was doing. I instinctively sided with kids sent to the office for disruption because the teacher made discipline a public spectacle (the old "names on the board" technique), so in the moment I didn't care if the boys were bullies. Only after I was marched in to apologize by another teacher did I begin to see my target as a person, obviously hurt by what I did, and only now do I see him as just another struggling teacher, one who hadn't yet learned the skills of classroom management.

Two: The authority of giving. People carry these figures of authority in their heads throughout their lives, and some make eternal war on them. This sense of fighting intensifies the more you feel that you have somehow cooperated with the oppressor, as George Orwell or Malcolm X felt they had done. So when some radicals realize they can't punish the world into changing, an odd defeatism settles over them, a kind of revolutionary all-or-nothing-ism: the syllogism neatly dividing the world into oppressed and oppressor, McMurphy and Nurse Ratchet, justifying the (perpetually) coming conflict to make solidarity along these severely drawn lines--often with a kick of self-loathing privilege. Reality for these revolutionaries is Cuba in 1959, with the guerrillas about to sweep through. It becomes very easy to believe that all is lost, in this mindset, because in fantasy, it usually is. And there are so many Hollywood versions of this story, often involving a sci-fi hero who presses the right button to reveal all, and make power crumble.

I don't mean to disparage militants doing good work, movies processing these feelings, inevitable revolutions, or even dreams and utopias. How else can you teach something good that's not already there? My worry comes when dreams defeat the dreamers, the psychic toll taken by the Law on those who see humanity as losing. This frightened pessimism is the mentality that envies Kaiser Soze, and limits what we see as revolutionary even before totalitarianism takes hold (which it always does in the Law), because we don't notice how revolutions are underway all around us--how we train for the job before getting it.

To take a mundane and blessedly middle-class example, last week my neighbors gave me tools and advice to help me fix our snow blower--the kind of problem I used to daydream about as a renter. As the machine came to life, I felt something more than gratitude: It was power and, for lack of a better word, faith. Power because I'd learned to fix something that had seemed unfathomable. Faith because I found that a neighborhood--a network sometimes viewed with suspicion or competition, like school or work--might also contain a community. I wish this feeling was what Star Wars (George Lucas's 1977 Vietnam parable) had talked about instead of the aptly named Force. (After my Grandma died, I learned that she took my brother and me to Star Wars all those countless times in the '70s without ever liking it. That was real faith.)

Many come by this insight of giving every day, and change the world in small ways without acknowledgment. Others teach large numbers of people using the same strategy. But as I cleared the sidewalks for neighbors the other night, this pride and optimism mingled with news, art, and internet noise reminding me (as any corporate employee knows) that oppression hasn't ended, that the Empire stands. There was first the entirely fictional "suppressed" Grammy speech by Lorde, circulated in social media, where the singer (an imagined reader of Naomi Klein) urged fans to send "the psychopaths that currently run the world to the planet's prisons," and added, "Peace cannot happen with reconciliation. That was Nelson Mandela's mistake."

There was also The Lego Movie (2014), a kind of Star Wars remake that called for just this reconciliation--telling "President Business" that maybe he didn't have to be the bad guy after all--and attacked by Fox Business at the same level of inanity on which hoaxes operate, with one guest echoing Hoover's FBI to cite It's a Wonderful Life (1946) as evidence of Hollywood's anti-capitalist bias. (George Bailey was a banker too, guys.) And there was The Daily Show's Jason Jones hugging a Russian gay-rights protester, a grandmother who quoted TV's Angel to say that if "nothing we do matters, then all that matters is what we do." In the Minneapolis Jones mentioned, there were also free Art Shanties, a screening of 1977's Eraserhead (showing the Law's dread of human need--pictured above with the Olympics bear mascot), and an amazing piece of music and dance by an artist I know, about his loneliness in the network that saved him after he appealed for a kidney donor through Facebook (Antarctica, which was like a live Eraserhead, pictured at the top under a photo from the recent Ukraine protests).

You have your own news, and I'm sure it was more significant. But if it involved changing the world, take a moment to reckon with this month's cover essay by Adolph Reed Jr., in Harper's, boldly titled "Nothing Left: The long, slow surrender of American liberals" (his battle metaphor right up front). Then watch what I've come to think of as its unwitting answer and negation: a real speech, and a moving one, by actor Ellen Page, coming out as gay before an audience of actual youth workers, advocates, and young people on Valentine's Day in Las Vegas (embedded above, transcript here).

That last moment blots out the rest, which says something about how change works. But start with Reed, subscribing to Harper's if necessary (it's great), and take my word that the author can be brilliant, even here. He sings the old song that cultural politics can't challenge real "power" because they're not based in a majoritarian movement for economic justice. He would have us reforge the "labor-left alliance" of the It's a Wonderful Life era, a familiar old line he sees and raises on the symbolism of an African American president "sold, even within the left, as a hybrid of Martin Luther King Jr. and Neo from The Matrix."

For Reed, there's been no progress since the '80s, only "defeat and marginalization"--and why? Because the left "lacks focus and stability," drawing "its inspiration, hopefulness, and confidence from outside its own ranks"--"from this oppressed group" or that (students, Zapatistas, "the black/Latino/LGBT 'community'")--rather than doing "long-term organizing" around populist goals such as "single-payer health care, universally free public higher education and public transportation," and "federal guarantees of housing and income security."

But, to quote Ellen Willis 15 years ago, "I'd suggest a different explanation for the [economic] majoritarians' failure: their conception of how movements work and their view of the left as a zero-sum game--we can do class or culture, but not both--are simply wrong" (Don't Think, Smile!, 1999, p. x). As Willis writes, "People's working lives, their sexual and domestic lives, their moral values are intertwined... If [Americans] do not feel entitled to demand freedom and equality in their personal and social relations, they will not fight for freedom and equality in their economic relations" (p. x-xi). Predatory power in one arena feeds predatory power in another.

What's more, "It's not necessary, as many leftists imagine, to round up popular support before anything can be done; on the contrary, the actions of a relatively few troublemakers can lead to popular support" (p. xvi). This is how the radical "gesture" Reed denigrates can teach the country, as Willis experienced first-hand at the lonely start of the women's liberation movement.

The pattern Willis outlines is familiar to anyone involved in successful social movements such as LGBT equality. As "radical ideas gain currency beyond their original advocates, they mutate into multiple forms," she writes. "Groups representing different class, racial, ethnic, political, and cultural constituencies respond to the new movement with varying degrees of support or criticism and end up adapting its ideas to their own agendas" (p. xvi-xvii). With popularity, the culture-teachers bring "pressure on existing power relations. Liberal reformers then mediate the process of dilution, containment, and 'co-optation' whereby radical ideas that won't go away are incorporated into the system through new laws, policies, and court decisions" (p. xvii).

Willis calls this dynamic "a good cop/bad cop routine," where liberals eventually "dismiss the radicals as impractical sectarian extremists, promote their own 'responsible' proposals as an alternative, and take the credit for whatever change results" (p. xvii). While this "process does bring about significant change," she worries that "denying the legitimacy of radicalism... misleads people about how change takes place," and leaves us "unprepared for the inevitable backlash" (p. xvii).

Here is where Willis, who died in 2006, joins Reed in warning that the political right takes the marginalization of radicals as an "opportunity to fight back. Conservatives in their turn become the insurgent minority," and "the liberal left keeps retreating" (in another metaphor of war)--so that "the entire debate shifts to the right" (p. xvii).

Three: The leap of faith. The same process applies to conservative ideas, I would add--some argue marriage is one of them. But contrary to the economic determinism of leftists and child-rearing determinism of conservatives, our "debate" is more changeable than we might think--as marriage equality shows. The "good cop/bad cop routine" could more accurately be described as a "good teacher routine" within any effective protest movement going back to civil rights: giving incentives and setting limits to get power moving. The goal is always to change minds--something you can either do badly or well. Because what's the alternative? Smashing heads?

People baffled that LGBT equality groups would donate money to Republican candidates who supported the cause, or that disability activists would let Bush Senior take credit for the Americans with Disabilities Act, miss how "raising costs" on bad policy only goes so far. Why not let President Business be the good guy? Great teachers connect, offer respect and humor, and give good reasons for cooperation, which is always a gift. They establish boundaries in ways that save those who would test them from embarrassment. In other words, they build authority--exactly the sticking point for the libertarian left of Willis.

In the anthology Anarchist Pedagogies (2012), edited by Robert H. Haworth, the word authority is mentioned 69 times, all but five with a negative connotation. To anti-authoritarians, authority usually means taking power away--through coercion, deception, commands, threats, terror, manipulation, surveillance, punishment, and bribery. But authority also involves giving power. The author in authority could as easily be the pull of art, the charisma of show, love of family, the weight of knowledge, the legitimacy of representation, duty of order, or the leap of faith. So the book's five positive references to authority tell how it can be shared or ceded between radical street medics, scientists, and (hey) Zapatistas.

Of course, giving and taking can blur when different kinds of authority overlap, as in a democracy bought and paid for, or art that lies, or love made conditional through withholding (the disastrous advice of Dr. Phil and others). Unlike those examples, fully legitimate authority affirms an odd duality for those who are under it: You are good, and the rules matter. Every other approach to teaching or activism subtly undermines both ideas. The ultimate goal of all discipline, like all effective world-changing, is reconciliation. This was Mandela's grace.