Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

tumblr

13.3 The Rhine Gorge is one of the most famous river stretches in the world: a symbol for Germany. Filled with Medieval castles and natural landscapes, its views inspire the imagination. The Romantic stretch flows geographically between two towns: Bingen am Rhein in the South and Koblenz in the North. Video Credit: United Nations World Heritage Committee

0 notes

Text

Koblenz: Deutsches Eck

13.2 A monument stands at the town of Koblenz where two important rivers meet: the Rhine and Moselle. The site is named Deutsches Eck, a former stronghold of the Medieval Teutonic Knights. Today, an equestrian statue of Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm I marks the site, suggesting to the mind the importance of Koblenz to the German soul.

0 notes

Text

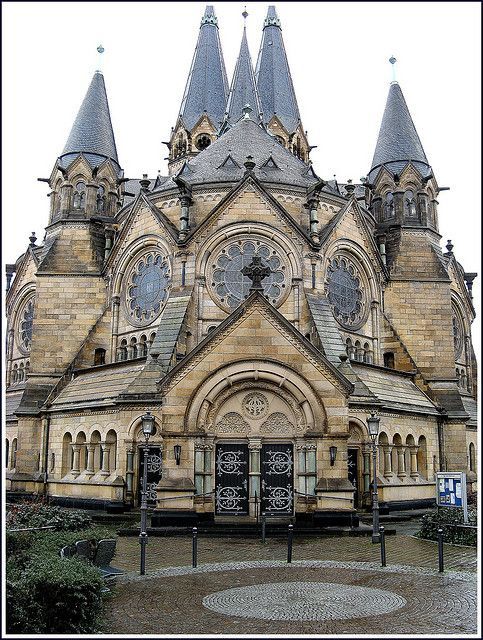

Fairy Tale Castles along the Rhine: Koblenz

13.1 Two pictures each: from bottom to top, the castles of Koblenz are Stolzenfels, Thurant, Ehrenbreitstein, and the Marksburg.

0 notes

Text

13. Koblenz, Germany

At the Northern end of a historic river valley stands proud Koblenz, an Ancient town that seems to hold a portion of the German soul. Like two bookends of a rich fantasy novel, Koblenz and its opposing town, Bingen am Rhein, guide river traffic in and out of the fabled Rhine Gorge. In this geographic river formation, a treasure chest of Romantic views awaits the ship-bound traveler. Both natural beauty and human constructs adorn the cliffs with stunning artistry. Between the two towns, Koblenz is actually older, making it the oldest Romantic river town in the Upper Middle Rhine Valley.

Human fortifications date in Koblenz as far back as 1000 B.C., because at the same site as the town, two great rivers meet: Rhine and Moselle. These flowing waters make for a strategic trade position on the Ancient continent, as is evident to all. Julius Caesar builds the first bridge in Koblenz in 55 B.C. across the Rhine to the town of Andernach. Then, the Romans construct Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, which guards Koblenz from above.

Although the Romans would love to hold on to the jewel of Koblenz forever, the town is a high-priority strategic target, and thus highly-coveted. As early as 259, the Franks invade and destroy the Roman bridge. This puts the fort at risk. Still, the area remains in Roman hands long enough for two religious cults to emerge: one to Mercury, and another to the Celtic-Roman deity Rosmerta. In the pre-Christian era, Koblenz becomes an important polytheistic stronghold.

When Rome falls, Koblenz falls into the hands of the Franks, permanently, who rise to become the dominant German Kingdom, creators of the Holy Roman Empire. After the death of Kaiser Charles the Great, Koblenz becomes an inheritance to his son, Kaiser Louis the Pious. Then, the town passes on to Kaiser Charles the Bald in 837. Over the next few years, the heirs of Charles the Great meet at Koblenz regularly in order to discuss the terms for the division of the Empire in the famous Treaty of Verdun, in 843. This is one of the most consequential moments in European history: the beginning of the near thousand-year fracturing of the Holy Roman Empire of Germany into multiple pieces. What happens in Koblenz explains why Germany never develops a coherent State government, until perhaps the Modern era.

Though not far from France, Koblenz becomes a part of the Kingdom of Germany. In 1018, Kaiser Henry II presents the town of as a gift to the Archbishop of Trier, one of the three permanent Electors of the Kaiser. In the feudal Christian system, it is important for Monarchs to curry favor with spiritual figures, and the donation of Koblenz is a great symbolic gift that strengthens ties between Church and State. It also makes Koblenz a symbolic seat for the Archbishop-Elector, one of the most powerful men in Low Medieval Europe. Because of this, Trier holds tightly on to Koblenz, until the eighteenth century, making the town a personal residence for the Archbishop-Elector as of the seventeenth century. Kaiser Conrad II even receives his official election at Koblenz, making the town of the many unofficial capitals of the Holy Roman Empire.

Once sacked by Norsemen, Koblenz learns the hard way that the town must protect itself with staunch defenses. To this end, there seem to be three strategies. First, town leaders construct many defensive castles, such as the Marksburg, Stolzenfels, Lahneck, and Thurant. This leaves behind a rich density of beautiful Medieval architecture in the town. Second, leaders donate a part of the municipality to the Teutonic Knights, who create the Deutsches Eck to guard the intersection of the Rivers Rhine and Moselle. A monument at the Teutonic location stands to this day. Third, town leaders are always careful to maintain the fortifications at the mighty Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, left behind by the Romans. This explains why the massive complex still dominates the skyline above Koblenz, to this day. The presence of the Teutonic Knights, together with the high number of castles and fortifications, guarantees physical security, and the naturally heavy river traffic guarantees the economic prosperity of Koblenz throughout the Middle Ages. By the 13th century, Koblenz joins the other towns of the Valley in the Rhinish league of cities, as an added security measure. And the many steep cliffs provide a formidable natural defense.

Yet total mayhem comes to Germany in the Thirty Years’ War of 1618-48, and Koblenz is not spared the misery. Following the war, the Archbishop-Elector of Trier comes to the rescue and helps Koblenz rebuild. It is common in Germany for the same pattern to take place: after conflicts tear a town to pieces, a spiritual figure comes to the rescue.

Wars among the European powers of France, Austria, and Prussia tear Germany a part multiple times, and all these powers vie for control of Koblenz across the eighteenth century. In the end, Prussia wins, and Koblenz becomes the Prussian seat of government in the Rhineland, forever entrenching the town as part of Germany, where it surely belongs.

However, for a brief time, France occupies the Rhineland after WWI, attempting to gain control of Koblenz. The German population in the town defiantly insists on using the German spelling, “Koblenz,” rather than “Coblenz,” after 1926. In WWII, the town receives heavy bombing from Allied forces, but between 1947-50, Koblenz serves again as the seat of government in the Rhineland, serving at the center of rebuilding efforts in the region. Today, Koblenz belongs to Germany, as it should, and it is at the Northern apex of the UN World Heritage Site for the Upper Middle Rhine Valley.

Koblenz seems to have an unusual amount of Cultural appeal. Its four riverside fortresses appear like castles in the clouds, and a lovely Old Town is a delight to experience. It is a remarkable place with an even more remarkable history, and any traveler who takes a river ride through the Gorge will receive a regal send-off at the terminus at Koblenz.

0 notes

Text

12. Bingen am Rhein, Germany

The Rhine Gorge is an internationally-recognized World Heritage Site that runs through many small German towns with picturesque views and stunning scenery. The UN calls the Gorge the “most Romantic stretch of river in the world.” Traffic enters the river at the town of Bingen am Rhein in the South, and water flows Northward to the town of Koblenz, which represents the exit. Though not as old as Koblenz, Bingen am Rhein has a history that defines the character of the Romantic Rhine, one of the most sought-after tourist destinations in the world. For this reason, Bingen am Rhein is toward the very top of the list for the most authentic river towns in Germany.

The Rhine Gorge is a natural geographic formation in Western Germany. It constitutes several miles of river, banked on both sides by canyon, densely-packed with scenic views of castle, fortress, and Medieval tower. There are many Romantic river towns clustered together in this tight space, one after another, which makes a boat ride an ideal way to see the rich density of Cultural heritage. Because of this, the Rhine Gorge is a travel destination for millions of tourists, each year. People come from all over the world to see the river between Bingen am Rhein in the South and Koblenz in the North. When people think of “Germany,” many think immediately of this specific stretch of river.

Although Celts build the original town of “Bingium,” the Romans occupy it in 77 A.D. Eventually the town takes the name “Bingen am Rhein.” The reason why the Romans make a presence in the town is that they see its high potential for trade, at the intersection of the Rivers Rhine and Nahe. In their strategic way, the ancient Roman architects take advantage and build a wooden bridge across the Nahe, along with a defensive bridgehead castle. A Westward military road then connects the riverhead castle of Bingen am Rhein with the ancient city of Trier, the oldest and largest Roman city North of the Alps. The connection to Trier will ensure a general flow of material blessing and prosperity over the course of centuries to Bingen am Rhein, which then passes onto all the towns in the Rhine Gorge.

However, the connection to Trier also puts Bingen am Rhein, along with its other towns in the Gorge, at the mercy of powerful military forces, from the start. In the Roman era, a powerful religious cult forms around the Mithraic movement, all across the Empire, a movement based on the sacrifice of bulls. By 236, an authentic Mithraic monument appears in Bingen am Rhein, which makes the city a point of pilgrimage for religious devotees and Roman soldiers who worship Mithras.

A century later, Christianity has clearly overtaken Bingen am Rhein. This is very early in history for a German town to already be Christian. Because of this, Bingen am Rhein becomes an important point of early Christianity, North of the Alps. The local presbyter is a man by the name of Aetherius of Bingium, whose gravestone is still visible in the most historic religious building in the municipal area: St. Martin’s Basilica, a lovely Medieval Church with a distinct red and white coloring.

On the Roman map, Bingen am Rhein lies just a short distance from the Limes — the intercontinental wall of antiquity that, for many centuries, guards the upper limits of the Roman Empire from “barbarians.” Naturally, when the Limes falls to successive waves of barbarian attacks, control of Bingen am Rhein passes into the hands of the Germanic people, and the Kingdom of the Franks comes to control the town. However, the Franks do not hold on to this particular town for long. Instead, they pass it on to the mighty Archbishop of Mainz, who has the power to both rule and protect the town.

The Archbishopric at Mainz is the most powerful seat in the Catholic Church, outside Rome. Many Archbishops of Mainz take pride in protecting Bingen am Rhein, but the most infamous and cruel, and also influential, Archbishop, from the perspective of Bingen am Rhein, is Hatto II. In the tenth century, he changes the history of the entire Rhine Gorge when he builds a quaint tower on top of an old Roman castle site, at Bingen am Rhein. The people call the construct of Hatto the “Mouse Tower, and it becomes one of the most recognizable and important structures in the history of the region, not only defining the local architecture of Bingen am Rhein, but also defining the economic character of the entire Upper Middle Rhine Valley. Early in its existence, the tower becomes the source of a fascinating origin folktale, told here.

The legend surrounds the origin of the name, “Mouse Tower.” When Hatto builds the tower, he is one of the most powerful men in Europe, and according to legend, he abuses his power, and exploits and oppresses the peasants and merchants under his rule. Especially in the town of Bingen am Rhein, he finds a unique way to exploit the river traffic that passes by the town: that is, he uses the tower as a platform for archers and crossbowmen to assault the crews of ships, that do not comply, with a rain of arrows, as a forcible means to collect unreasonable amounts of monetary tribute. Thus, the tower is nothing more or less than a levy, or a toll collection point. And Hatto uses the levy tower as a place of extortion.

During a famine in 974, the poor in Bingen am Rhein run out of food, and Hatto greedily stores all the food up in locked-up barns, but he raises the prices so much, that most cannot afford to buy it. Because of this, the peasants become hungry, and thus angry, and threaten to rebel. In response, Hatto devises what he thinks is a rather clever plan: that is, he tells the peasants that the food is all locked in a single barn, even though it is, in truth, completely empty. And when the peasants break in, he quickly shuts the door behind them and sets the barn on fire. As the peasants burn alive, the voice of Hatto is heard to say, “Hear the mice squeak!” Several variations of the tale emerge, where he always says something cruel like this.

The folktale maintains that, as Hatto makes his jolly way back to his castle, an army of mice immediately attacks him, as punishment. Hatto flees from the mice and hops on a boat, seeking the safety of the tower on the other side of the river, but the mice follow him, drowning by the thousands in the river behind him. Thousands more mice make it across the river, eating their way through the tower door and up to the highest level, where Hatto is caught, trapped. The mice cover up his body and eat his body alive, gnawing the flesh from his bones. Thus, the tower takes the name, “Mouse Tower.” Similar stories, about mice who punish cruel Medieval rulers, pop up in multiple cultures and geographies around Europe, such as Poland.

A century after the construction of the legendary Mouse Tower in Bingen am Rhein, the most important historical figure in the history of the town is born, namely, Hildegard von Bingen. Students of European history may recognize her name, and her name includes a convenient clue to the town of her birth. As a benevolent Catholic Abbess, she looks out fiercely for the underpriviledged citizens of Germany. She is basically the opposite personality from Hatto II. In fact, Hildegard is literally one of the most important figures in the history of the Catholic Church. She is a woman of many titles: saint, feminist, genius polymath, Medieval musician, and prolific prophetess. Impressive, no doubt, are her visions, set to music, which constitute some of the most vital and fascinating works of Christian Mysticism, period. Stories of her childhood indicate that she is sickly at birth, but her sickness contributes to her receptivity to the Spirit of God.

The town of Bingen am Rhein probably takes on slightly more character traits from Hildegard, than it does from its Archbishops. Just like Hildegard herself, the town is remarkably revolutionary in nature, establishing itself firmly in opposition to traditional structures of hierarchy, standing up for the poor. There is an unusual frequency of peasant uprisings against Church and State in the town, a sign of the free spirit of the people. Throughout history, the Archbishops of Mainz must deal regularly with these rebellions, and a dispute between one Archbishop and the Emperor leads to a full destruction of Bingen am Rhein, in 1165.

Finally, in the thirteenth century, the old Mouse Tower enters its heyday of profitability, as a levy tower, and the toll collection system in Bingen am Rhein becomes such a successful financial model, that by the fourteenth century, a staggering number of sixty similar structures have sprung forth, downstream, between Bingen am Rhein and Koblenz. Then, around the massive toll system of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley, a local feudal system develops. Various nobles build an increasing number of mighty castles and fortresses, in order to defend the toll collection points, until the whole Rhine gorge is quite literally covered in various and sundry castles, forts, towers, and other beautiful stony constructs.

This stretch of river in the Rhine Gorge is essentially a microcosm for the economic model of European feudalism, on full display, a flourishing, zoomed-in version of the history of the Germanic world especially, all within a single stretch of a few miles of river. It is astounding. In order to compete with each other, each feudal lord builds himself the most impressive structure possible, and gathers his own military unit, and the conflicts between the various lords and castles along the river are the stuff of literal legends. Today, the many fabled towers and castles that dot the Upper Middle Rhine Valley represent some of the densest cultural wealth that the German-speaking world has to offer, anywhere.

The most famous military fortress in Bingen am Rhein is Klopp Castle, of the thirteenth century. It is majestic, and it serves partly as an anchor for military defense of the town, but more importantly, serves as a means to gain important status for the town, so that Bingen am Rhein can join the larger Rhine League of Towns, a much-needed security blanket for the collective towns of the Rhine gorge.

Still, association with the Rhine League does not help the town avoid destruction in 1525, when, like Wiesbaden, Bingen am Rhein joins in the social revolution called the Peasants War, a failed German revolution by the peasants against feudal nobility. Like in most towns that join this revolution, many residents of Bingen am Rhein suffer a great slaughter, in this conflict. The ensuing centuries constitute a painful time for the whole Rhine gorge, in the form of multiple wars and municipal fires.

Like many German towns in the West, from 1792 until 1813, beautiful Bingen am Rhein is French, under foreign occupation, but the Congress of Vienna in 1815 puts the town squarely back on the map of Germany, where it belongs.

Throughout the centuries, poems and folktales a plenty have taken inspiration from the Rhine Gorge. It is among the most Romantic river stretches in the world, and Bingen am Rhein is the first town a person encounters on a boat ride through the Valley. Any list of candidates for “most authentic German city” would be lacking, without Bingen am Rhein, simply because of what the Upper Middle Rhine Valley means to German Culture.

0 notes

Text

Hessian State Theater, Wiesbaden

11.3 After the German Empire forms in 1871, its first Emperor Wilhelm I builds a beautiful site for opera, plays and music performances in Wiesbaden, his favorite spa destination. The theater is based on models from Prague and Zurich.

0 notes

Photo

11.2 The geothermal baths, springs, and waters of Wiesbaden go back to the Roman era

0 notes

Photo

11.1 Kurhaus Wiesbaden, a temple of this world. In the nineteenth century, the Kurhaus functions as the spa center and casino that serve as the fulcrum of economic turnaround, in the gambling city.

0 notes

Text

11. Wiesbaden, Germany

Built on a foundation of natural springs discovered in the Roman era, Wiesbaden is the first “spa town” of Germany.

Wiesbaden is a stunning city with a rich history that is well-appreciate across all of Europe. It origins go to 6 A.D. Back then, Rome rules the province of Lesser Germania from the dual capitals Mainz and Cologne. Across the Rhine River from Mainz, Roman legionnaires discover a series of hot springs. These natural baths represent an ideal point from which to refresh military horses. Furthermore, the minerals from the gaseous spring water become a resource for the characteristic red hair dye that achieves widespread popularity in this period, among Roman women. Because of this, the newly-discovered hot springs draw immediate international attention, and in 71 A.D., the Romans construct a strongly-fortified stone bridge to cross the Rhine and grant the city of Mainz access to the hot springs.

Over time, around the baths, there develops a new municipality. Its name is “Wiesbaden” which literally means, “meadow baths,” a reference to the 26 naturally-flowing hot springs that well up from the land. Wiesbaden is the original definition of a “spa town” in German territory, one of the oldest such examples in all of Europe. Countless German cities follow the example of Wiesbaden, many of which now take the prefix title “Bad” before their name, perhaps a throwback to the name Wiesbaden.

Though originally a Roman town, lovely Wiesbaden becomes Germanic rather early in its history. The transition begins when the Romans, in 121, begin to staff town defenses with mercenary Germanic warriors. Then, in 260, a wild tribe from Swabia, the Allemani, fully seizes control of Wiesbaden. The Romans never again control the city.

Over time, the the Franks conquer the entire Allemani domain, and this leads to the gradual absorption of cities like Wiesbaden into the Frankish Kingdom. As a Frankish city, Wiesbaden becomes the site of a royal castle, the beginning of the royal era of the city. The hot springs are always a popular attraction for the royal class, and with the Franks, the name “Wiesbaden” receives honorary Imperial mention in the chronicles of Charlemagne. The famous Emperor is possibly inspired by Wiesbaden, when he builds his throne in Aachen, itself a spa town with royal baths.

By 1232, Wiesbaden has grown to such a place of cultural, economic, and political influence within the Holy Roman Empire that it becomes an official Free Imperial City. This is an honorary distinction. It makes the municipality one of the hundred-odd autonomous city-states that have no feudal lord besides the Emperor himself. Yet this official status only lasts in Wiesbaden for a meager ten years, because of a sudden and vicious war between Emperor Frederick II and the Pope. This leads the Archbishop of Mainz, Siegfried III, to order the thorough destruction of Wiesbaden. This is also the beginning of a darker time in the history of the city.

From this point forward, never again does Wiesbaden count as a “Free Imperial City,” and the status of the city declines slowly during the Middle Ages, though the city certainly continues to operate as a symbolic power center of a prominent Germanic family, the Counts of Nassau. One of these Counts, Adolf of Germany, even rises to the surprise title of “King of Germany,” which makes him a leading finalist for the title of Holy Roman Emperor, and yet Adolf never receives official sanction from the Pope, and dies fighting off one of his successors.

Historically, it almost feels as if Medieval Wiesbaden, with its natural blessings, is always just one step away from heights of true grandeur. For whatever reason, it is usually the meddling of a bureaucratic religious figure, like an Archbishop in Mainz or a Pope in Rome, that stifles the ambitious hopes of the city.

Still, adaptable Wiesbaden is always rebounds. It is a vibrant economic center throughout most eras of Germanic history, simply by virtue of its healing baths, and in 1329, it is no surprise that Emperor Louis the Bavarian smiles favorably upon town fortunes, and makes a “concession” to the city, for its loss of Free Imperial status, when he grants coinage rights to the Counts of Nassau, a right which effectively restores the power of Wiesbaden to run many of its own municipal affairs. In this way, Wiesbaden is almost an “unofficial Free City” in the Holy Roman Empire. There are actually many of these.

Along with much of Germany, Wiesbaden descends into its true period of suffering in the Reformation. The descent begins around 1517, through the controversial figure of Martin Luther, after the surprise, nationwide publication of his local writings without his consent, through the use of the Gutenberg printing press, a technology that emerges across the River from Wiesbaden, in Mainz. One of the main points of contention that Luther makes, in his popular texts, is that scripture is the only authority for power from God, and that formal church authority, without truth, means nothing. One of his famous statements is that a farmer, in possession of scripture, has more authority than the Pope, absent of scripture. In response, German laypeople begin to assert their own authority to interpret scripture, a move which Luther not only supports, but indeed demands.

Yet the peasants, surely due to their destitute living conditions, seem to read even more deeply into the demands of Luther, than he intends, and many peasants naturally want to extend their newfound spiritual authority toward the seizure of political and economic empowerment. Luther seems surprsied by this. Athough he is happy to see peasants learn to read the Bible, and heal their souls by the word of God, he does not remotely support their uprising. Rather, Luther seeks the coveted stability in Germany that has never existed, that would finally come with a stronger Imperial central government. Luther is a monarchist, and certainly no sixteenth century pioneer or advocate for early democracy, and the word “freedom” to which he refers is mostly spiritual, in nature. Nonetheless, the loose interpretation of his popularized writings leads to the outbreak of the first widespread “German” national revolution, called the Peasants War of 1525, in which the peasant class seeks to secure a very literal form of freedom, or social mobility.

In this context, the town of Wiesbaden, in a heroic act, is one of the few cities in Germany to actively take the side of the peasants. This says something about Wiesbaden. Most German cities and nobles, along with Luther himself, take the traditional side of the Emperor instead. In the tragic conflict that ensues between the uprising peasants and the staunch upper classes, hundreds of thousands of peasants, armed largely with torches, garden-hoes, and pitchforks, become victims of outright slaughter at the hands of heavily-armed and highly-organized forces of the Holy Roman Empire. No matter their courage, the peasants never stand a fool’s chance, without larger support. The Empire brutally crushes the rebellion, and subsequently, punishment comes to the city of Wiesbaden for its participation in the uprising. The Emperor strips away official town privileges for forty years. This is a cruel but serious setback in the development of European democracy, though certainly not the first, nor last, failed revolution in German history. It is also a setback for Wiesbaden, but it does not destroy the revolutionary spirit of the city, which is made of stronger stuff.

A second tragedy, in this era, falls upon Wiesbaden in the form of two municipal fires, in 1547 and 1561, which are powerful enough to literally destroy all the Medieval buildings. As a result, there remains not a single building in the town that predates the early seventeenth century. Yet not to be outdone, the greatest tragedy of all time in Wiesbaden is the gargantuan Thirty Years’ War, after which there are no more than 40 living residents in the city, in 1648.

Decimated Wiesbaden understandably fails to rebound in the century after the War, when in 1771, a last-ditch attempt to rebuild the dead city finally comes from the Counts of Nassau, who legalize gambling. During the ensuing era of Napoleonic occupation, the Wiesbaden Casino opens in 1810, and in the presence of organized gambling, the natural town spas begin to receive significant economic patronage, once again.

The nineteenth century represents the era of remarkably fast turnaround for the city. Within five years of the casino grand opening, the Congress of Vienna grants Wiesbaden a high priviledge, making it the official, and no longer just unofficial, capital of Nassau, which marks the highest official status that Wiesbaden has enjoyed since 1242. The city certainly deserves feudal recognition, and many feel that this recognition comes far too late in the history of the city. Nonetheless, a late, blessed period descends upon the inhabitants of Wiesbaden, and it is to this period that one can attribute the magnificent and highly-romantic appearance that the city presents, today.

Still, even after recognition as the capital of Nassau, the political history of the city is by no means finished. In keeping with its legacy from the German Peasants War, as a “revolutionary city,” Wiesbaden courageously joins in a second German Revolution, that of 1848, in which the European academic classes demand constitutions in many countries. German academics hope to finally overcome the shadow of the dead Holy Roman Empire and establish, at last, a fully-unified Germany. The demands of the revolution include freedom of assembly and freedom of the press, somewhat in imitation of the democratic revolutions of America and France. Yet just like the Peasants War of 1525, the Revolution of 1848 meets resistance from the thick German aristocratic nobility, and while some scrappy concessions fall from the table, as a whole, the revolution is a failure, and the lower classes remain thoroughly dissatisfied with their petty gains, in the difficult struggle. Germany produces no unified nation at this time, nor any sort of satisfying democracy. And yet, in Wiesbaden, the revolution is a relative success: the feudal Counts of Nassau grant the people their own constitution. This demonstrates the generally progressive nature of the town, which seems to follow an enlightened pattern that goes back as far as the Roman era, when the Roman overlords simply hand the town over to the Allemani without much struggle.

Again, in 1866, the revoutionary city of Wiesbaden rebels against Prussian overlords, and takes the losing side of Austria in the Austro-Prussian War. While this appears to be a “defeat” for the city, it is definitely not a setback. Really, it turns out to be a positive development, for though it leads to the temporary and forced prohibition of gambling in Wiesbaden, it also spells the end of the long reign of the feudal Dukes of Naussau, who, all things considered, are rather benevolent overlords, but who are overlords, nonetheless. Enjoying a sense of newfound freedom, ironically in the authoritarian Prussian regime, Wiesbaden finally enters its heyday as a free, fully-funtioning, international, cosmopolitan spa town. This strike of good fortune, of course, is only made possible by the unique allure of the hot springs, which always enables the city to attract the upper crust of society, such as Prussian monarchs and Russian nobility. King Wilhelm I, for example, is so impressed with Wiesbaden, that he directs and promotes the construction of the renowned Hessian Theater, a great Baroque work of art (see photos above). Then, the same Wilhelm I becomes the first Emperor of the Second Reich, and his son, Wilhelm II, builds a summer residence in Wiesbaden. Other frequent guests to the city include some of the greatest artists in the world, such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Johannes Brahms, and Richard Wagner. Around the turn of the twentieth century, the lavish city with a population of 86,100 entertains 126,000 visitors per year, a truly staggering tourist industry. So powerful is the allure of Wiesbaden, at this time, that it becomes home to more millionaires than any other German city.

As a final revolutionary act, Wiesbaden serves as host to two notable anti-Nazi resistors: Ludwig Beck and Martin Niemöller. General Beck is the author of a 1944 assassination attempt on the life of Adolf Hitler. Although the attempt fails, it nonetheless serves as a symbolic light of hope to the German people. Meanwhile, Niemöller is a theologian, founder of the Confessing Church resistance movement against the Nazis, and he gives his last open sermon at the Market Church at Wiesbaden, prior to his arrest.

Oddly enough, Wiesbaden avoids total destruction during Allied bombings in WWII, leaving 75% of the city intact. The reasons why the Allies treat Wiesbaden with such surgical precision, similar to how they treat Regensburg, are not entirely clear. There is nothing “rational” about which culturally-rich cities become targets of indiscriminate carpet bombing, and which do not. Wiesbaden is just lucky, in a sense, in that only 25% of the city meets destruction. There is, of course, an unsupported theory, which posits that wartime Americans love Wiesbaden so much, that they decide not to bomb it out, so that they can inherit the spa town and turn it into one of their cherished military bases, post-war, which they do.

Finally, in the organization of West Germany after WWII, the German province of Hesse selects Wiesbaden as its capital city. This is a remarkable honor, given that Hesse is a historic region that also includes the alpha world city of Frankfurt, as well as historic cities like Marburg, Darmstadt, and Kassel. Yet in a way, Wiesbaden is a highly-appropriate selection for Hessian capital. Wiesbaden is a wealthy city, and Hesse is a very wealthy province, with a higher per capita GDP than any other German province, besides the city-states.

Overall, the legacy of Wiesbaden is mainly two-fold: one, it is the original cosmopolitan spa town in German-speaking lands, a model for all subsequent generations, opening its baths to people from all over the world. Two, in a related sense, the town is one of the greatest symbols of democracy in the Germanic world, a revolutionary hotbed that is certainly “ahead of its time” from the Peasants War of 1525, to the Revolution of 1848, down all the way through the modern, authoritarian Prussian and Nazi regimes, all of which represent periods where Wiesbaden nobly takes the “losing side” in a humanitarian struggle for freedom.

In spite of this, perhaps Wiesbaden is nowhere near the top candidate for “most authentic German city,” for even though the city is always a sophisticated place, it nonetheless loses its eminent status early, during the thirteenth century, and never really becomes the true “Free Imperial City” that it promises to be, within the Medieval world order. Furthermore, the entire Medieval Old Town of Wiesbaden is non-existent, as of the sixteenth century, a tragic loss. Still, the Medieval losses provide room for the surges of status and architecture that come to distinguish the city in the 1800s, which really make up for a lack of older structures, proof that Medieval prominence is not the only way for a German city to develop into a great beauty. Anyone who has been to Wiesbaden, for any amount of time, will attest to its status as a European jewel. Currently, Wiesbaden is the tenth richest city in Germany, perhaps the most revered German resort town, a fact which would surely make the humble horseback Roman legionnaires proud, who stumble unexpectedly upon the hot springs in 6 A.D.

0 notes

Text

Back to Nature in Garmisch-Partenkirchen

10.3 Bavarian Alps in Garmisch-Partenkirchen: Nature’s call

0 notes

Text

Houses of Garmisch-Partenkirchen

10.2 The many housing styles of Garmisch-Partenkirchen

0 notes

Text

Four Seasons in Wamberg, Garmisch-Partenkirchen

10.1 A small and isolated High Alpine village resides within the municipal borders of Garmisch-Partenkirchen. It is called Wamberg.

0 notes

Text

10. Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

The municipal area of Garmisch-Partenkirchen is the most authentic town in the German Alps and a center of Bavarian Culture. It is famous as the center of the 1936 Winter Olympic Games, the year when Alpine skiing is introduced to the world.

Although mostly famous as a modern ski town, the Alpine municipality of Partenkirchen originates in 15 A.D. as an important Roman point along the intercontinental trade road between Augsburg and Venice. The road through the Alps is not easy to cross, but it constitutes the way to travel between North and South, upon the ancient continent. Then, Medieval Garmisch develops next-door to Partenkirchen in the valley, and the two separate towns prosper and grow into simple, distinct, quaint villages, full of square wooden houses, and an Old Church.

Medieval Garmisch and Partenkirchen remain separate for most of history. 1492 represents the discovery of America, which brings a strangely dark era to the two towns. Sudden trade possibilities between the New World and the Old make the North-South Alpine trade route too dangerous to compete. Because of this, many towns in the Alpine valley together experience an economic depression. In turn, the inhabitants of Garmisch and Partenkirchen begin to turn on each other and also against themselves.

First, a mob turns against the Church, because many people hold God responsible for the economic misfortune. And tragically, although the Church forbids witch-hunts, the will of the people is unstoppable, and up to ten percent of the population burns at the stake or hangs through crude garroting. The vigilante trials, sentences, and executions among the people take place at Werdenfels Castle, which becomes a place of superstitious spiritual terror. People believe the castle is haunted, which only adds fuel to the fire for further witch-hunts.

The townspeople ultimately fear the retribution of God. Because of this, they tear down the lovely Old Church, and designate it as a hay barn. Then, over the centuries, Werdenfels Castle becomes such a symbol of darkness, that the people tear it down as well, in 1750. After this last destruction, only some of the ominous ruins of Werdenfels Castle remain intact, because many of its constituent stones are forever relocated to the New Church, which the people build in order to repent with God.

Finally, late in history, the townspeople of Garmisch and Partenkirchen rediscover the ruined Old Church, demoted to crude barn status, and they notice that the building contains Medieval frescoes. This inspires a reconstruction and restoration of the Old Church. Nobody rebuilds Werdenfels Castle.

In spite of some very dark times, the dual towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen are blessed, and ultimately enjoy a very fortunate and privileged position in the Germanic world. In the nineteenth century, the famous King Ludwig II of Bavaria likes to visit the area so much, that he sneaks the construction of one of his smaller castles onto an isolated mountain peak, within the municipal areas. The name of the castle is “King’s House on Schachen,” and one can only access it via a three- or four-hour hike, into the Alpine trails. While the King pretends to use the isolated house as a “hunting lodge,” historians know that Ludwig is not actually fond of hunting, and he secretly uses the estate as a personal cabin, for leisure, games, and other forms of simple entertainment.

King’s House on Schachen is important in the history of botanical gardening. A unique Alpine garden welcomes visitors, set upon the stony grasses of the estate, and the garden is one of the oldest of its kind, anywhere in the world. It draws hikers and features mountain plants all the way from the Alps to the Himalayas. From the King’s House, a spectator can even view the Zugspitze, the tallest mountain in Germany.

Besides Ludwig II, the most renowned resident of Garmisch or Partenkirchen is Richard Strauss, the late and great composer of the Romantic movement. Born in Munich in 1864, Strauss is closely associated with Garmisch, even though he first finds success in Vienna and Berlin, because in 1908, he hires an architect to construct a personal Villa in the Alps, seeking a secluded and hidden location. At first, Strauss only intends to spend the summers in Garmisch, but his plans change dramatically, when his Jewish daughter-in-law Alice becomes a prominent target of Nazi officers in 1938. Richard anxiously hides Alice, along with her husband and children, in the secluded mountain Villa, in order to protect them from the concentration camps. Isolated Garmisch provides adequate Alpine protection for his small family, but all other Jewish relatives of Alice die in the camps, and Richard is forced to live out the rest of his days in the Alpine Villa in Garmisch, with his family.

During the Nazi era, the cities of Partenkirchen and Garmisch ironically reach their zenith in popularity, because the dictator Adolf Hitler forces the two cities to merge and become the site of the 1936 Winter Olympics. These games feature a new Olympic event, Alpine skiing. Thus, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, one of the most popular of all Olympic sports is born. Since then, the popularity of Alpine skiing has exploded across the mountain world.

Due to its fascinating history, Garmisch-Partenkirchen is not only a lovely resort town, but it is really nothing less than the most authentic mountain town in the German Alps, filled with quaint, charming, and zany constructs. Especially Partenkirchen, the older of the two towns, has many fresoed buildings and cobblestone streets that are representative of another time. At its heart, the municipality is basically the very archetype of a mountain town, in the consciousness of Western Civilization. The oldest houses are tiny wooden structures, spaced far apart, organically. It almost feels like the cows and horses own the open space, and indeed, during certain times of day, the busy road traffic stops, in order to let the livestock pass, and pose for pictures. That is why the most efficient way to access the famous city is by train, and the city is well-connected to places like Munich, Innsbruck, Dortmund, Hamburg, Bremen, and Berlin, which are giant population centers in Germany.

Although one might not know it, lest one had time to venture around, the whole municipal area of Garmisch-Partenkirchen consists of multiple smaller villages and private residences, tucked away within isolated pockets, and one of these villages, known as Wamberg, sits so high in the mountains, that a visitor might only know of its existence, if one possessed the power of flight — or perhaps one might be able to see it, while sailing through the air from the top of the Olympic ski jump, or certainly from atop the Zugspitze. Essentially, Garmisch-Partenkirchen is full of surprises, not your typical, clichéd resort town. It is immersed in over two thousand years of quirky, sometimes scary, Germanic history and culture, and it is the original German Alpine jewel.

0 notes

Text

Romanesque Churches of Andernach

9.1 A Medieval escape to Andernach is complete with an escape into its Churches.

0 notes

Text

9. Andernach, Germany

Andernach is the oldest Romantic river town of the Rhine. It has an exemplary collection of well-preserved Medieval structures.

Many German cities have a castle or two; some lucky cities have multiple castles that take you back in time to the Middle Ages, but the rarest city “feels” like a castle, from one end to the other. That is what makes Andernach so special. It is one of the oldest, most complete, and best-preserved Medieval cities in Germany, and it just happens to sit along the Rhine River, at the most Romantic stretch.

Some of the best cities in Germany are small, simply because these largely escape the destruction of WWII bombers. Andernach is small enough to escape most of the destructive conflicts of history. Only the natural process of time seems to have decayed its Medieval buildings, and time has only made the city appear more charming.

Andernach originates in 12 B.C., under the Celtic name of “Antunnuac,” which translates to, “farm or village of Antunnos/us” — a man who has not been identified. From these humble origins, Andernach grows into first a Roman, and then a Germanic, town with a formidable and sophisticated system of defense structures. It is important for any river town to defend itself against invaders, especially given the high-density Rhine traffic.

The Old Town Wall of Andernach includes an authentic castle that is the southern-most anchor to the Electorate of Cologne. The wall also has plenty of gates for control over what goes in and what comes, and towers from which to see and operate defenses.

Andernach gives rise to two lovely Romanesque Churches, both dedicated to the Virgin Mary. One is urban, which provides an important place of refuge, and the other a rural abbey that is even more isolatedd. The abbey is special. It is called Maria Laach, and it is set upon a volcanic lake, the largest of all such lakes in the Eifel region. Yet the abbey itself is perhaps even more beautiful than its natural surroundings. A venture inside reveals many treasures from the world of Medieval spirituality.

A major tourist draw to Andernach is a Medieval “Old Crane,” a piece of fifteenth-century river technology that traditionally requires multiple men, and also an official sanction of permission from the Empire, in order to operate. The crane has a lever and treadwheel system that can lift heavy loads to and from river craft. Examples of a typical load on the crane might include millstones for the local mill, tuff-stones for construction in the Netherlands, and wine-casks. Few German municipalities have such an authentic piece of Medieval industrial machinery to show off to town visitors.

Finally, from the Baroque time period, the central Old Town is complete with a Renaissance-style “Haus von der Leyen,” a royal estate that now serves as a welcoming municipal museum. From end to end, a walk through the city is an effective and seamless way to journey through time, from Roman to Medieval to Baroque to Modern, and this is a striking feature of Andernach. Virtually every street corner is rich in some period of history.

Namedy Fortress sits among the rural city outskirts, along with a rare cold-water geyser that is the tallest in the world. These peripheral sites complete Andernach and make it the “German ideal” of synthesis between rural and urban, Nature and human settlement. Altogether, Andernach sits only a short distance North of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley, which is in fact the most popular and Romantic section of river to visit, anywhere in Germany. It would be a shame to see the rest of the Valley only to miss Andernach. It is one of the greatest jewels of the Rhine, where time stops, as if frozen in place.

0 notes

Text

8. Kempten, Germany

The beautiful appearance of Kempten betrays a violent history -- a tragic tale of resilience that mirrors the history of Germany itself.

Though not nearly as famous as other Bavarian cities, Kempten originally forms in Celtic times. It is technically older than either Augsburg or Regensburg, and while it flies under the radar of most observers, in subtle ways Kempten qualifies as one of the most authentic German cities.

The first mention of the settlement, on paper, is 50 B.C., under the Celtic name, “Cambodunum.” It is only a small municipality at this early date, but its mention is so early that it constitutes the first official documentation of any city on paper, anywhere in Germany. In 15 B.C., the exact same year that Caesar Augustus orders the construction of nearby Augsburg, Kempten falls into the Roman Empire. Because of this, Kempten is linked together with Augsburg for the rest of history, and the two cities belong to the same Germanic province: Swabia. In Germanic times, the two cities compete for status as Swabian capital. Augsburg wins the contest, in the end, but Kempten remains an important Swabian city.

After two destruction events in Roman times, Kempten falls to the Germanic tribe called the Allemani. The opposite of the systematic Romans, the Allemani constitute a mobile, restless, and free nomadic tribe, and under their tenuous watch, the city comes, once again, under existential threat. In 683, a battle with the Franks brings the city down to ruin, the third such instance in the young life of the city. Even Augsburg does not suffer as much tribulation in its early history. Kempten seems doomed to more than its fair share of trials and tribulations.

Thankfully, in the year 700, the Medieval wheel of fortune finally turns favorably upon Kempten, in the form of the construction of a church for the Benedictine order of monks. The church takes the name of Kempten Abbey, and this becomes the new namesake for the city. From then on, the old name “Cambodunum” falls permanently out of use.

Charlemagne has a personal connection to Kempten that is very fortunate for the city. That is, he marries an Allemani princess, named Hildegard, and she loves Kempten Abbey in a special way, partly because of its beauty, and partly because of her Allemani roots. Kempten is still an Allemani city when Hildegard marries the Emperor, and she uses her direct connection to Imperial resources to provide the city with decades of financial and lobbyist support. This would be a major boon for any city, and it elevates Kempten to a high-status cultural center within the Holy Roman Empire.

Throughout the entire life of Charlemagne, the Imperial elite continue to use Kempten as a spiritual place of refuge. Furthermore, Kempten Abbey has a stunning architecture which serves as a quintessential model for the rest of the Christian world, at the time. Yet the charmed period of good fortune in Kempten lasts only as long as the protective aura of the royal couple, and when Hildegard and Charlemagne die, the city falls naturally back into its old cycle of destruction-events. Constant violence ravages the municipal area for an entire century, until the devastation finally ends, and urban reconstruction can begin anew.

From the ashes, a pattern emerges: the city always rises on the backs of its spiritual leaders. The Abbots of Kempten obtain the title of “Princes” in 1062, after which date Kempten Abbey becomes, quite officially, one of the three most powerful abbeys in the Holy Roman Empire, a status which lasts until 1803. Overall, Kempten feels very “all-or-nothing,” in its history. Either the city is being completely destroyed, or else it is one of the most prominent municipalities in the Holy Roman Empire. There is no in between, and amazingly, each time the city falls to total destruction, a new replica of the city emerges in its place. The city is like a cat with nine lives. It is nothing if not resilient.

However, the city almost destroys itself, when a fracture emerges in its Medieval municipal government. The fracture is based on a conflict between Church and State, or between spiritual and secular leaders. Predictably, these two separate branches of nobility often have separate interests, and they are not always happy to share power. The condition of dichotomous rulership divides Kempten between two separate governments. One calls itself the Free City of Kempten; it is a spiritual government of Abbots. The other calls itself the Imperial City of Kempten; it is run by secular oligarchs. Although the two sections of the city occupy the same municipal boundaries, they duke it out for many centuries against each other, and both governments go by the name of “Kempten.” Thus, there are really two cities within one.

Of course, it is Jesus who says, “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” and the potential for downfall becomes even greater in Kempten when the Reformation movement of Christianity begins to sweep like wildfire across Europe. In the Reformative century, the two cities known as “Kempten” polarize and entrench themselves against each other, along exactly opposite sides of the theological divide. As expected, the Abbot-supervised Free City of Kempten remains staunchly Catholic, while the Imperial City of Kempten becomes openly Protestant.

Then, in the Thirty Years’ War, the two halves of Kempten destroy each other, quite literally, with the help of Germanic as well as Swedish troops. Certainly, by no means does 1637-38 mark the first total destruction-event in the history of Kempten, but the ravages of the Thirty Years’ War are famously horrific, and they bring about the absolute darkest downfall in the whole history of Kempten, which is saying a lot.

Finally, while the city still sits in its own ashes, Kempten claims its chance to not only rebuild, but also to reassert its central position in the post-war Holy Roman Empire, when the greatest Abbot in the history of the city emerges, Roman Giel of Gielsberg. He is a far-sighted, though controversial, religious figure, and to the surprise of all, he orders the immediate construction of St. Lorenz Basilica, the first large church to emerge after the Thirty Years’ War, anywhere in Germany. Almost like a rose blooming in a desert, this “miraculous” construction puts Kempten directly back into the spotlight of Germanic Culture, a call back to the glory days of Princess Hildegard and Charlemagne, back when the original Kempten Abbey brings the spiritual elite to the city on a regular basis, from all over the Empire. Truly, it is almost inconceivable, to think that a church as beautiful as St. Lorenz Basilica could emerge directly after the Thirty Years’ War, the most destructive single event relative to the population in all German history. Perhaps this is the lasting genius of the Abbot’s plan. The project of construction certainly costs years of peasant labor. It pushes the rural farmers, as well as the urban craftsmen, to the absolute limit of their capacities. The human cost is significant, when the population is already starving, and who knows if the Abbots really care, but there is no doubt that St. Lorenz Basilica gives the inhabitants of the city a vital sense of purpose, a point of focus around which they can mobilize in their misery, something they desperately need in order to kickstart their stagnant, post-war economy.

After its return to glory under Roman Giel of Gielsberg, Kempten still remains divided into two political parts, a condition that is unchanged since the thirteenth century. Ironically, it is not until the great Napoleonic Wars, and the destruction they bring, that the two split halves of Kempten finally manage to stitch themselves back together, this time in unity under Bavarian rule, and in 1819, all the old boundaries officially fall, so that Kempten finally becomes a free and unified city again, for the first time in six hundred years.

In the end, Kempten is actually one of the most powerful Germanic cities in the Holy Roman Empire, as long as it is not being destroyed at any given moment. The tragic story of the city, with its multiple instances of destruction and rebuilding, and its long struggle between division and unification, is an effective microcosm to the history of Germany itself, a tragic and fractured country which experiences the three most destructive wars in human history and always finds a way to rebuild, and even stitch itself back together, each time. An effective motto of Germany might as well be, “Still standing,” which would also be a perfect motto for the city of Kempten. Because of this, Kempten is unquestionably one of the best and most authentic examples of a German city. It is a model for the beauty and resilience that can still shine through centuries of turmoil. You can’t keep Kempten down, and you can’t keep Germany down, so you might as well get used to it. And Kempten is actually quite lovely. It is the largest city in the Allgäu, one of the most visited regions of Bavaria. It is a true Bavarian jewel, a miracle of German resilience.

0 notes