Photo

Estelle Egglishaw

1939 — 2022

I am very saddened to note the passing of Estelle Egglishaw (née Bisson), of St. Brelade, Bailiwick of Jersey, on May 26.

When I met Estelle in 2015, she was assisting visiting family researchers at the Jersey Archives on Clarence Road in St. Helier. Through her helping me with my research, I learned that she had known my Great Uncle Harold Brideaux.

More importantly, I learned that she was one of Jersey’s greatest treasures. She was one of the diminishing numbers of original Jèrriais speakers of Jersey—the original Norman dialect of the island’s people. I am not surprised that the Channel Islands Family History Society honoured her with a lifetime membership.

Estelle was an expert on the nuances and idiomatic colour of Jèrriais, which is challenging to meaningfully transmit to many of those who attempt to learn the language today. She loved the work of the Jersey artist and lithographer, Edmund Blampied, whose art she believed embodied the life and culture of Jèrriais. And she was a walking encyclopedia (Jerripedia, really) of Jersey history and culture. She was also an expert florist, who provided floral arrangements for royal visits to Jersey.

Had she warned me I was going to be the recipient of so much information when she invited me to dinner a year later, I would have bought my recorder to the table, manners be damned. During that same visit, it was Estelle who made use of her social connections to help me find the remains of L’Amiral, a Brideaux homestead for over a century in St. Ouen Parish, and the nearby Les Vaux Brideaux fields.

Jersey is impoverished by her passing but made all the richer by her legacy.

#jersey#jerseyci#jèrriais#jerriais#Estelle Bisson#Estelle Egglishaw#stbrelade#jersey heritage#jersey channel islands#jerseyarchives

1 note

·

View note

Photo

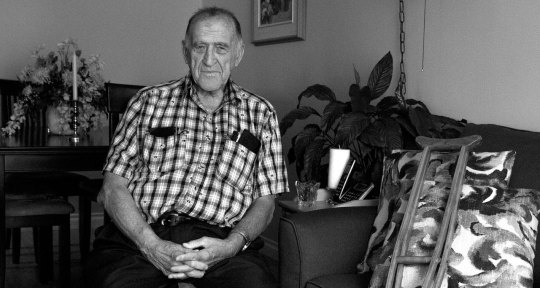

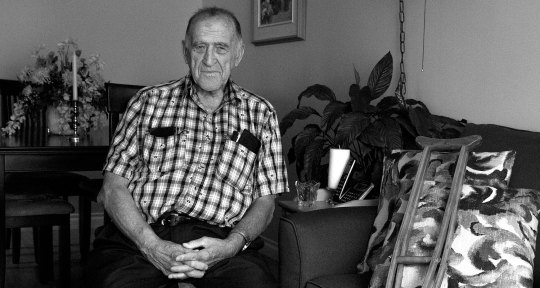

Charles Brideaux

1929 — 2021

I’ve learned the sad news of the passing of Charles Edwin Brideaux, age 91, of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario on January 1. I wrote about Charles in a previous post, and his adventures as a stevedore during the golden years of shipping on the Great Lakes. Charles was the last of Edwin Charles Brideaux (1887-1966) and Phyllis Marie Chestle’s (1905-1986) surviving children. Having been predeceased by his wife and one of his sons, and having experienced several tribulations, Charles was in every sense a survivor. I will always be grateful for having had the honour to meet and interview Charles.

#Charles Brideaux#Charles Edwin Brideaux#Philip Brideaux#Sault Ste Marie#Edwin Charles Brideaux#JerseyCI#Jersey#Brideaux

1 note

·

View note

Text

William Morvan, 1930 — 2019

Marjorie Brideaux, 1944 — 2019

September has been a sad month. On September 21, William "Bill" Morvan passed away in Jersey at age 89. I wrote about him at length in February 2016, about his contributions to the States Assembly as a senator, and to the hospitality industry through Morvan Hotels — not to mention his membership in a receding community of native Jèrriais speakers on the island. He was also connected to my family: my great grandfather Philip John Brideaux married Marie Morvan after he returned from South Africa to Jersey at the turn of the 20th century.

And on September 11, my mother, Marjorie Brideaux, passed away in Calgary. I have written of the arrivals and departures of various people in Jersey and the Brideaux lineage, so it is surreal to be writing of her now, too. She married into the Brideauxs in 1968, bringing with her the public service legacy of the large Bennett family in Canada. I’m too close to my subject to write anything but a novella, so I will simply say this. Chief among her strongest qualities was resilience, demonstrated through all of her many tribulations. That’s the gift she gave to me, to demonstrate throughout all of mine.

0 notes

Photo

"Coumment qu'tout a changi, hélas!"

Ruth Amy-Le Moucheux and the Jèrriais Language

On my previous visit to the Bailiwick of Jersey, Joy and Maurice Marie invite me back to their home in St. Brelade parish to meet and talk with Joy’s niece, Ruth Amy-Le Moucheux. As I sit in their living room with Ruth, I am at first unaware that she is a past-president of l'Assemblée d'Jèrriais. She is steadfastly modest, but overflowing with knowledge about Jèrriais, and memories of its trajectory from the end of the Second World War to the present.

Ruth was born in 1946 (the year of my great grandfather’s passing in St. Mary parish) at Rozel sous le Moulin, St. Martin parish, not far from where my Great Uncle Harold Brideaux would later settle. “My grandfather was a farmer,” she explains, “and I spent a lot of time down in Rozel Bay [on Jersey’s north coast]. All my grandfather’s land, the valleys and all that, went down Rozel Valley. So it was really beautiful to go and pick the primroses. When my grandfather gave up the farm, we moved to La Butiere, which is on the Rozel main road. My father was a grower there, and went to work in the market afterwards, when he gave up growing.”

Beginning in the 1950s, Ruth was educated at Springside School at Faldouët, near Gorey on the east coast. Springside was run by Mrs. Hilda Ahier, and later her sister Miss Linda Le Seelleur, during an era when attending small private schools, founded and run by visionary educators, was not uncommon. “Mrs. Ahier was married to Captain Frank (Francis) Ahier, who was in the navy. Miss Le Seelleur used to teach us piano. Luckily, Mrs. Ahier and Miss Le Seelleur spoke Jèrriais, because I couldn’t speak English. So they taught me my English.” Afterwards, Ruth attended the Girl’s Collegiate on La Colomberie in St. Helier. The original building on the site, dating back to the late 1700s and heavily transformed through the 1800s, was demolished and replaced in 1998, after protracted and acrimonious debate.

At the Girl’s Collegiate, Ruth’s teachers were fascinated by her Jèrriais and encouraged her to speak it during a period where Jèrriais was looked down on. The Jèrriais accent was wrung out of schoolchildren through elocution lessons or masked from teasing English peers. “The parents sort of thought it was going to ruin their English. You know, you’d have an accent because you were speaking. Like many of us, I was brought up on a farm so, you know, we were really countrified, weren’t we. We went to chapel. I was a Methodist. We were at St. Martin’s. Well a lot of the people there—the Germains, Fauvelles, and that—we all spoke Jèrriais at church. Some children were discouraged from speaking Jèrriais. But I didn’t care. Because Jèrriais was my language, our language, the language my parents spoke, my grandparents spoke, I was brought up to speak it, so really, I didn’t care what the [English] girls thought. I stuck to it and spoke Jèrriais. And later, Amelia Perchard [the late poet, writer and playwright of Jèrriais] taught me how to write Jèrriais.” At the same time, Ruth’s teachers pushed her to compete in the Jersey Eisteddfod festivals.

As I've discovered in my visits to Jersey, preservation efforts of the island’s Jèrriais language well precdes the Second World War. During the German Nazi occupation of Jersey from 1940 to 1945, islanders could avoid Nazi censorship through the public performance of plays in Jèrriais. They could avoid Nazi surveillance of the citizenry by speaking in Jèrriais. While many German soldiers could speak French, they could not understand the centuries-old Norman dialect, which sounded like French, but wasn’t. Moreover, their most learned academics at headquarters couldn’t understand its written form (L'Office du Jèrriais, 2010).

Although the growing influence of English language and culture in the Channel Islands went back to at least the nineteenth century, it increasingly took hold following the war. Despite the resurgence of Jèrriais during the Occupation, returning evacuees from England brought back children schooled solely in English, and St. Helier’s transformation into an international offshore banking centre entrenched Anglo influence. As Ruth mentions, that influence had made Jèrriais culturally unfashionable. Just two years after the war, St. Ouen-born Frank Le Maistre, the noted editor, writer, and scholar of Jèrriais, proclaimed the languages of the Channel Islands to be dying (Le Maistre, 1947). The Auregnais language of neighbouring Alderney is already extinguished, for example, the entire island having been evacuated in advance of the German invasion. The Sercquiais language of the neighbouring Isle of Sark had fewer than 20 speakers in 1998; over 20 years later, that number is most certainly thin (BBC, 2014). Le Maistre went on to compile the famous Dictionnaire Jersiais-Français in 1966 and later was awarded the Order of the British Empire.

To get a sense of this one particular way I've observed the language persevere among the Jèrriais community, one must understand two things: the deliberate, celebratory creation of Jèrriais poetry and plays throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; and their recitations and performances during the Jersey Eisteddfod festivals, among other occasions.

The Eisteddfod is a Welsh name, and an ancient Welsh tradition, involving the celebration and performance of all facets of Welsh literature, language and culture. The Eisteddfod concept inspired other communities and countries outside of Wales to do the same, including Jersey. The Jersey Eisteddfod was established in 1908, growing to become a comprehensive competition of works and performances encompassing all aspects of Jersey culture, including Jèrriais. Many of the entrants were schoolchildren, and teachers became important brokers and champions for participants. Although songs were sung and plays were performed, Jèrriais competitions were characterized by many poetry recitations, monologues and dialogues in Jèrriais. Entrants were evaluated by panels of elder Jèrriais speakers, scoring entrants on facets like pronunciation, accent, and cadence, and giving awards. Those children whose families were losing their Jèrriais had an opportunity to preserve it. Those children whose families had lost their Jèrriais had an opportunity to revive it. And so a great tradition of writing Jèrriais poetry and plays has flourished around the festival.

As I learn in conversing with the island’s Jèrriais-speaking elders, the Eisteddfod is a major part of sustaining the community of speakers. And the Eisteddfod has been a major part of sustaining Ruth’s Jèrriais. “We used to go in the Eisteddfod, recite learned plays, and everything, it was quite simple really because Amelia Perchard wrote masses of Jèrriais plays and poems for the Eisteddfod. And we used to do the plays. When we did our plays it was lovely. We must’ve gone in for plays, what, ten years? Yes? Auntie [Joy] and I did the duologue. And you were good!” Ruth points at Joy. “She is good! And she won the cup in Jersey French. She had honours!”

I ask Ruth whether she can still recite any of the Jèrriais poems she delivered at past Eisteddfod festivals. Ruth thinks for a moment. "Well one favourite one I’ve got—I mightn’t be able to remember all of it because it is quite long—I think Auntie knows it. It’s all about life. Jersey life. It’s titled Pensées d'à ch't heu, by Amelia Perchard."

Ruth recites the first two stanzas:

Coumment qu'tout a changi, hélas!

Dépis les jours dé ma jannèche,

La vie paisibl'ye dé ches temps-là

N'est qu'eune mémouaithe, pour ma vieillèche.

Tch'est qu'éthait janmais pensé d'vaie,

Dans not' Jèrri changements patheils?

Dites-mé, est-i' pôssibl'ye qu'il faut

L' "Conmité d'Bieautés Naturelles",

Pour prêsèrver not' héthitage?

Est-che qu'les Jèrriais n'sont pus d'aut' sages?

Ah! Tchi bonheu qué les anciens,

Heûtheurs au Paradis d's Êlus

Né connaissent pon la vie d'à ch't heu,

Et n'peuvent pon vaie tch'est qu'j'sommes dév'nus!

Tout l'monde remplyis dé jalousie,

Envieurs et auv' qu'eune ambition -

Dé pathaître mus qué lus vaîsîns!

Pouv'-ous m'dithe don qu'il' ont raison?

N's'raient-t-il pon pus heûtheurs, pouôrres corps,

S'i' s'contentaient pûtôt d'lus sort?

Here is how it sounds when Ruth recites it:

vimeo

Ruth joined l'Assemblée d'Jèrriais at a young age, becoming secretary in her teens, and eventually becoming its president for a short time. “It must’ve been about 1969 when I became Secretary. Because I’d have been 16. I was young because Dad was in it, you see. Dad was treasurer for many years. Mother was on the committee. Auntie and Uncle [Joy and Maurice] have been on the committee.”

Almost five decades on, many in the community of Jèrriais speakers who had coalesced around l'Assemblée in the postwar years are still here yet. The population of Jersey has diversified as people from around Europe migrate to the bailiwick, but most islanders are solidly English-speaking, and over 30 per cent are British-born (States of Jersey, 2012). There are perhaps 2000 Jèrriais speakers left. Many islanders regard Jèrriais as part of a bygone era, even though the language greets you as you pass through the airport, and the public transit buses sport the names of Jersey’s 12 parishes written in Jèrriais along their sides. The island has evolved far from its Norman culture since being orphaned from the medieval Duchy of Normandy in the mid-1200s. Most British assume the island is part of the United Kingdom, which it isn’t. Owing largely to its loyalty to Angevin rule during the 1204 French invasion of Normandy, and having fallen under the care of the Plantagenet kings following the 1259 Treaty of Paris, Jersey (and neighbouring Guernsey) remains a crown dependency. While loyal to the Queen, it is otherwise not a part of the United Kingdom or the European Union.

This nuanced historical context is understandably lost on many. That’s perhaps why, in December 2018, some islanders were grumbling about the relevancy of a proposition, brought to the Assembly of the States of Jersey (Jersey’s parliament) by one its members, that Jèrriais be incorporated into official government signs and letterhead, as part of an effort to preserve and promote the language. At the time, residents were more preoccupied with the debate about the location of a much-needed new hospital, and raised the usual concerns about money. Money, however, was not an issue. The signs would be replaced, as they wore out, with bilingual replacements at no extra charge. The heartening result was that on February 12, 2019, not only did the States Assembly agree to the proposition, but also agreed on an amendment to adopt Jèrriais as one of the official languages of the States Assembly, alongside English and French.

Would that my St. Mary parish-born grandfather, whose first language was Jèrriais, could have witnessed this. Symbolism and ceremony were important to him. For Ruth, life simply continues as one of the island’s last native Jèrriais speakers.

“It’s lack of speaking right now. Lack of speaking at all. But we’re going to start now, we’ve made a resolution, Joy and I, that in the future when we speak to one another on the phone, it’s going to be en Jèrriais. So I’m going to instigate that.”

0 notes

Photo

Joyce Gilbert

1926 — 2017

It’s with great sadness that I’ve learned of the passing of Joyce Gilbert (née Brideaux) in St. Martin, Bailiwick of Jersey, on October 22.

Joyce was the last Brideaux born a Brideaux living in Jersey. She was the daughter of Herbert Brideaux (son of Elias Jean, son of Elias Jean) and Laura Renouf.

Joyce, along with her late husband Brian Gilbert, were pillars of l'Assemblee du Jèrriais and active in promoting and preserving the Jèrriais language. Joyce is also responsible for most of the ancestral research available on the Brideauxs in Jersey. I’ll be forever grateful of her legacy.

0 notes

Photo

The Carboniferous Counties: The Brideauxs in Wales, Part One

Francis Philip Brideaux (son of Francois Brideaux and Mary Hamon, grandson of Thomas Brideaux and Ester Lempriere) married Mabel Guillou in St. Helier, Jersey, not long after the turn of the 1900s. At the time, they could not have imagined that their union would result in an enormous family dynasty centered in the Rhymney Valley of South Wales.

Francis Philip’s family were living at 4 Belmont Gardens, in St. Helier, when the Germans invaded Jersey and began their five-year occupation in World War Two. The family did not seem especially content with that, because two of the Brideaux sons, Dennis and Ronald, were imprisoned on different occasions for not playing along. Ronald was given five days in prison in October 1943 for “failing to appear at work without sufficient grounds.” In March, 1944, Dennis was imprisoned for three months by the occupiers for “offering resistance.”

One member of the family, however, had left the island by the time of the Occupation. Francis Philip’s son, Frank (1912-1966), settled abroad, in Wales, where he worked in the coal mining industry. There, he met and married Adele Matilda Meyrick (1914-1999). Together they had five sons and four daughters, all of whom went on to have families of their own, who in turn now have families of their own. Many of the clan have stayed in the Rhymney Valley, settling mainly in and near the towns of Maesycwmmer and Caerphilly, in some cases within a few doors of each other.

Most of the valley falls within the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire (now largely Caerphilly County Borough). The Rhymney Valley itself is part of The Valleys, a series of valleys in South Wales fanning from Carmarthen in the west to modern Monmouthshire in the east, and from just below the Brecon Beacons in the north to the coastal plains of the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary in the south. The Heads of the Valleys Road —the A465 — joins the northern ends of the South Wales Valleys, running westwards below the Brecon Beacons before curving down southwest towards Neath, near Swansea (where more Brideauxs live).

The Valleys are the heart of mining and mining heritage in Wales. They are a part of the great South Wales Coalfield, which was extensively developed from the late 1800s. The population rapidly increased as collieries spread throughout the valleys, with settlements terracing up their sides. Coal went back down the valleys by train to the shipping ports at Cardiff, Newport, Swansea and others. The waste rock from which the coal was extracted went mostly to the hilltops to form coal tips (spoil tips). As my Arriva train from Cardiff Central Station winds its way up the Rhymney Valley, I can see the remains of the tips on the tops of some hills. The valley is dramatic, curvy, and lush, and the line follows the west side of the valley.

My rail stop is Hengoed, on the west side of the Rhymney River. On the east side is my destination, Maesycwmmer, where Frank Brideaux first settled. The Hengoed rail station lies in the shadow of an impressively tall, stone railway viaduct named (depending on which side of the river you live) the Maesycwmmer Viaduct. I can’t help but notice it as we pull into the station. Built over 150 years ago, the viaduct once supported a coal-ferrying railway, but is now part of a regional cycling path network.

I disembark from the train to be greeted by Frank Brideaux’s third daughter, Janet, who is married to Owen. Janet has been my main contact since discovering the Welsh Brideauxs and, like me, is researching the Brideaux ancestral history. Their home is on the eastern side of the valley with a beautiful view south, back in the direction of Llanbradach and Caerphilly.

Janet has taken the time and trouble to round up most of the clan, who are all waiting in the Maesycwmmer Inn for me to meet. When we enter, it takes me a few moments to realize that every single table in the pub, except for one, is packed with Brideauxs. There are children running about, and infants being held in laps. All the adults have a pint. My short term memory is quickly overwhelmed as I’m introduced to Brideaux after Brideaux. Somewhere in the handshakes, I am introduced to Philip Brideaux, and for the first time in my life, I realize that I am not, in fact, the only Philip Brideaux alive. Not surprisingly, this leads to a photo of the two of us together, and I’m amazed to compare us: a bespectacled writer from Calgary, Canada, next to a hard-working coal miner from Maesycwmmer, Wales.

One of the few open chairs I can find puts me in front of Maurice “Banjo” Brideaux. Maurice is one of the family’s elders, born in 1947 in Maesycwmmer, where he has lived most of his life.

As we talk, I have to concentrate hard over the noise of the pub to understand his Welsh accent, particularly with Welsh place names. I can only guess how “American” my Western Canadian accent must sound by comparison.

“I got eight grandchildren, and two great granddaughters, they’re the two little ‘uns running around by you now,” he says. “When I first left school I started as a grocery boy for the cooperative, riding a push-bike delivering groceries. And then working on the buildings. From there then I went to work in steelworks. And then my cousin got me a job on the Gas Board. I stayed there then for twenty-two years. And I retired then when I was just over 45.”

Maurice’s retirement reminds me of Charles Brideaux’s in Sault Ste. Marie, who bought a pool with his retirement pension. “I had a lump sum then. Bought myself a car, passed my test, and never looked back,” says Maurice. “And I got a static caravan up in Tenby, where we go every year like. So we spend most of the time up there like, back and forth like.”

One of Maurice’s best memories is attending the Rolling Stones’ first concert ever in Cardiff, on September 11, 1964 at the Sophia Gardens Pavilion (which no longer exists). “We got down there, and they didn’t come on ‘til late. They was late comin on. So we missed the last train home. And we had to walk home from Cardiff then.” According to Google, this is apparently about a four-and-a-half hour walk. (“Oh aye, it was to the top of the mountain. Fair old way.”)

Maurice also had a penchant for dressing up as different characters, particularly around Christmas. “I’d dress up as somebody or other, dressed up as Boy George, or quite a few different people like, you know. One year I was dressed up as Wonder Woman. Well, I dress up as her, with a pair of shorts on, a little boob top, I had a pair of wellingtons, I painted them red, all glitter over them. And then, when I walked in, I had this tiara on and a wig. I walked in, and my son was playing a disco tune, he put Wonder Women on, and when that come on, I jumped out. And what I had done, I had a pair of rubber gloves, I’d blow them out and I had the fingers sticking out over the top.”

Sitting next to Maurice is one of his younger brothers, Peter Brideaux. As we introduce each other, Peter slips a small gift into my hand. It’s a lapel pin, depicting two crossed flags, that of Canada and of Wales. I think it’s a wonderful gift and immediately pin it to my coat. As Peter explains, it’s symbolic of the meeting of Brideauxs from either side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Peter is married to Helen, with a son, and a daughter and three grandsons. Like Maurice, Peter has lived in the valley all his life. When Frank Brideaux passed away, Peter was only 14. Out of economic necessity, he finished his schooling shortly afterward at the local secondary modern school and went straight into the building industry, based on experience he’d built up through a family friend driving construction vehicles. “I was basically told that I had to finish education as soon as I can, to come out and get a job and earn money, fetch money into the house, and that’s the way it was then, you know?” Without his father’s income, the family needed his help.

“I did have a job set up right there for me before I left school, so it wasn’t a big disappointment, I mean, but I really wanted to stay in school and do my exams, to come out there with some sort of qualification. But as it was, I left school at 15, and without any qualifications whatsoever, but 50 years later I managed to make a living for myself, and I’ve built a family, so I wouldn’t change anything now.”

Until he was 16, he could only drive the construction vehicles on building sites, and be ferried between sites by other crew members. When he was 16, he was able to drive himself and bought a motor scooter.

“I drive all types of machines, both wheeled machines and tracked machines. JCBs, Caterpillars, Komatsus, Kubotas, there’s all different makes. Hitachi machines, there’s loads and loads of them but they’re all basically the same to drive. It’s like jumping into different cars. It’s just a matter of sorting out where the controls are, you know. Different buttons and switches but all the controls are exactly the same on everything so if you can drive one, you can drive them all.” Dozers, graders, backhoes, crawlers… “Yeah, I can drive most things. I learned to drive them all basically, over the years. I’ve had 50 years driving them so there’s not a lot that I’ve come across that I can’t drive.”

Peter worked for his first company for over 12 years before layoffs sent him to another company for another year. His third job was driving machines around on the surface of the coal pits. “I’d be picking up coal with a machine and putting it on the conveyer belt, and feeding it into the washery. And the coal would go into a washery where it was washed and all the muck removed from it. Then the washed coal was loaded into a railway wagon and sent down to the local coal fired power station, which is still operating at the moment in Aberthaw, not far from Cardiff Airport. So, eight-and-a-half years there with that company, and then five-and-a-half years, with a local company from Caerphilly. And that was just going around to all the local building sites then, driving a JCB backhoe. But the company I’m with now, might’ve been 22 years.”

Being a licensed machine operator came in handy beyond the day job. In the early 1970s, Peter lived in Tirphil, further north up the valley, shortly after getting married. Early one morning, vandals jumped on a large 360 track machine, in a construction site across the street, and managed to start it up and put it in gear. Then they bailed out and fled, letting the machine run out of control.

“They were building a school opposite us. So, even in bed, me and the wife, we could hear this machine starting up, and I could hear this crashing going on. It smashed through the scaffolding, and out onto the road, and it was headed to our block of flats. So I jumped out of bed — I only had a pair of boxer shorts on — ran down the stairs, across the road, and into the machine. I stopped it just as it was comin’ out onto the road. If it was anybody else it would’ve come into the flats because there was nobody to stop it. The police come there, obviously. So the next morning, I had to phone work and tell them that I couldn’t get to work, because the police are coming to my flat to interview me, and the boss wasn’t very happy because I took the day off.”

* * *

In the morning, Janet and Owen take me out on a tour of the region, starting with an attempt to find a route to a coal tip I’ve spotted across the valley. We don’t manage to find a route up and in, but it’s still a great opportunity to get a sense of the valley and its terraced coal mining villages, including a stop at the Welsh National Mining Memorial and Universal Colliery Memorial Garden in Senghenydd. Young students from the local primary schools in the Aber Valley helped make countless ceramic name tiles making up the memorial. They are the names of men and boys who lost their lives in the many accidents and disasters in the collieries. Senghenydd is also the site of Britain’s worst coal mining accident, in which an explosion underground at the Universal Colliery killed well over 400 miners on October 14, 1913.

The coal tip I want to see is one of many in the valleys. The towering piles of black waste rock have extended the summits of hills, giving the grassy mounts dark, rocky peaks. Some of the older tips are a dirty olive from being grassed over. Over the years, many of the tips have been slowly, methodically removed, truckload by truckload, but swaths of the landscape of the South Wales Valleys has nonetheless been irrevocably shaped and transformed by coal mining. One of the more stunning examples of this is the view across the valley at the Big Pit National Coal Museum at Blaenavon, where Janet and Owen next take me.

The area around Blaenavon, including Big Pit, is a UNESCO World Heritage site, and Big Pit has remained open and accessible as a museum. Janet stays behind while Owen and I put on miner’s helmets with lamps and batteries, as well as emergency rebreathers around our waists, before being taken down into the mine from by a tour guide — who once worked Big Pit himself before its closure in as an operational mine in 1980.

We start by riding 300 feet down the mineshaft from the pit head in a large elevator. The air cools as we descend, and we emerge into a dark tunnel with old, thick, heavy wooden beams holding it up. Our helmet lamps provide light to see the way, bouncing and reflecting off wet stone walls with crystallized mineral stalactites. Water burbles in the dank silence through gutters running on either side of the tunnel. There are very few sources of electricity down here. Gas seepage from lower rock strata, deep below, and its possible buildup in mines (especially disused mines), has always been a serious threat to miners: the silent poison of carbon monoxide, the devastating volatility of methane and hydrogen (known as firedamp), or even the ability of coaldust to ignite explosively. Anything that contains a battery, or that could spark, must be taken off and turned over to pit head staff for safekeeping: watches, cellphones, penlights, matches, lighters, and so on. Tour guides carry gas monitors, and there are telephone stations at various positions.

In fact, it was firedamp and an electrical spark from signalling equipment that possibly caused the Universal Colliery explosion at Senghenydd. Any coal dust present (which was the cause of a previous explosion in the very same mine) would have exacerbated the explosion. Of the hundreds of miners who survived the initial explosion but were trapped, many or most died from asphyxiation by afterdamp, the mixture of poisonous gases remaining after all the oxygen is consumed by a firedamp explosion. Resulting fires blocked rescuers from reaching whomever might be still alive, and days passed before a recovery operation could begin.

The tunnel runs at a downward angle, turning back on itself in the opposite direction and going deeper. For large stretches we must stoop low as we walk to avoid banging our headlamps against the roof. In one passage, we turn off our headlamps to get a sense firsthand of absolute darkness. Miners trapped underground in an accident might have to await rescue in this absolute darkness for days.

Our guide shows us a series of empty stables, made of whitewashed stone and brick, where the mine’s pit ponies (or colliery horses) were housed in the 1800s through to the mid 1900s. The ponies spent most of the year underground in the dark tunnels, ferrying coal to the pit head, but were brought up once a year into the sunlight on “holidays.”

Pit ponies were eventually replaced with rail cars and conveyer belts. Our guide shows us the trestles for the conveyer belt at Big Pit, explaining how the quicker way out of the mine at the end of the day was to lie down on the conveyer instead of walking for hundreds of metres. This, of course, was not at all safe or sanctioned, and not only just because a miner had to know when to roll off the conveyer to avoid being entrapped in machinery.

Once back at the surface we rejoin Janet, and we tour the pithead baths building which has been converted to a cafeteria. The baths building was built around 1939 after growing social activism in coal mining communities was successful in convincing mining companies to provide facilities for miners to clean up at the end of the shift. That’s because coal dust and the underground environment left miners dirty beyond dirty. And combined with damp clothing, it caused health problems, including pneumonia and lung disease.

“Before the baths, the miners would go home to their families black with coal dust,” explains Janet. “In the villages, the wives would pull large tubs of hot water into the middle of the kitchen and get the bath ready for their husband before he came home every working day. The water would be black when he was done washing.” The pit baths relieved the burden on families and helped control coal dust in their homes.

From the Big Pit site, Janet and Owen take me to a beautiful lookout along B4246 above the Usk Valley, where Torfaen County meets Monmouthsire.

We then turn westward onto the Heads of the Valleys Road before taking the A470 north into the Brecon Beacons. Brecon Beacons National Park is large, and we only have time to drive through its centre. I’ve wanted to see the Beacons for a long time. The Beacons are very old, and most of the formations are a more visible example of a great swath of ancient sedimentary deposits, mostly red sandstone, found across the North Atlantic, that date back over 400 million years. The Beacons look like mountains, but they are, in part, large chunks of these red sandstone sedimentary deposits. These are sediments which came from the erosion of the mountains of the Caledonian Orogeny, during an impossibly ancient time in Earth’s history when life on land was only just beginning to flourish with any significance. The remains of the Caledonian mountain chains can be seen from the Northeastern United States, to Scotland and Norway, among other Nordic regions. The Beacons took their present shape when rivers, ice sheets and erosion from several cycles of glaciation cut through and carved them out over the past 2 million years.

About 100 million years or more after the rise of the Caledonian mountains, the region around South Wales was part of a different continent, and even at a different latitude much further south. What would become the Brecon Beacons was beginning to build from the outwash of the eroding Caledonian Mountains to the north. What are now the South Wales Valleys were then part of a shallow sea, which eventually filled with eroded sediment from the newer, eroding Variscan mountain chains to the south, and resulted in tropical swampland. The swampland became part of a vast band of tropical swamps and forests cutting across this ancient continent sitting astride the Earth’s equatorial region. The continent was Laurussia, and the period was the Carboniferous. Across the millennia and countless dry-wet cycles of the Carboniferous Period, the remnants of successive swamps and forests were lain down over the previous, until the crushing layers of sediment and peat baked and carbonified, forming vast pockets, or seams, of coal. Several hundred million more years passed as Laurussia became part of the Pangaean supercontinent. The region drifted into the northern hemisphere as Pangaea broke apart in all directions. At the dawn of the Anthropocene Epoch, humans discovered the surviving network of coal seams that had once been tropical swampland — the South Wales Coalfield.

* * *

The need for change in the pits of not only Wales, but all of Great Britain, spurred Prime Minister Clement Atlee’s Labour government to nationalize the coal mining industry following the Second World War. The National Coal Board was formed in 1947 to run the industry. By the early 1980s, the National Coal Board’s subsidies could not keep up with operating losses, the coal industry was in retraction, and cheaper coal from Europe was undercutting the board’s prices. Shifting government policy and pressures on the National Coal Board led to pit closures and layoffs.

The National Union of Mineworkers increasingly faced off against Margaret Thatcher’s neoconservative government. The union had staged a major strike in 1972 and again in 1974 in response to Edward Heath’s policies on miners’ wages. In 1984 the union’s leader, Arthur Scargill, decided that a major industrial action was again necessary in response to Thatcher’s pit closures and subsidy reductions.

In the middle of the resulting industrial action was Philip Albert Brideaux...

0 notes

Photo

Phil and Marilyn: The Brideauxs in Ontario Part 2

The house was almost completely on fire. Phil Brideaux could see the flames from his car on the highway. It was about 4:15 AM on November 18, 1982 and Phil was, as usual, on the road. He was returning to Sault Ste. Marie from one his many business trips to Sudbury, Ontario, and was passing through the Garden River First Nation.

Phil wrenched the car over to the side of the road and jumped out before leaping over snowbanks and dashing toward the house. He likely did not have a plan in mind, likely was acting on instinct, and likely had no idea what he was in for. Another passing motorist, a man from Edmonton, happened by about the same time, and jumped out to join Phil. The two shouldered their way into the burning house.

Years ago, when photographing firefighters, I learned that the problem with deliberately entering a house on fire without a self-contained breathing apparatus and some sort of Nomex fabric protection, is that you are putting yourself at great risk of being severely burned or asphyxiated. That’s because the interior of a burning wood frame structure bears no resemblance to dramatized depictions on television and movies: clear sight lines inside; spot fires burning here and there; breathable air; the ability to see and communicate with others; actors jumping through small banks of flames. The tropes are well known, but the real environment of a burning interior is completely hostile to survival.

The smoke from even a smaller fire contained in the corner of one room will eventually fill every cubic inch of a house, thick and black. You will not be able to see your hand in front of your face. You will have no idea what’s in front of you, or where you are. Even one lungful of smoke could knock you flat. Smoke is not a gas like carbon dioxide from a tailpipe. While it does contain poisonous gases, it’s mostly made up of tiny, solid, semi-combusted particles. The particles are hot, will coat the inside of your windpipe and lungs, will cause burning and swelling, and will quickly suffocate you if you are not pulled out in time.

The other problem is sometimes superheated air (of which one lungful will be fatal), or at least, very high heat from the flames. If you’ve ever been close to a building on fire, you may have felt the intense heat radiating off the structure. The heat alone can easily burn exposed skin if you are inside, and firefighters sometimes emerge from intensely burning structures with patches of first degree burns from any spot not fully covered by their bunker gear and Nomex hoods.

Absolutely none of this occurred to Phil, but he quickly found out. The two men made several forays into the house, being driven back each time by smoke, flames, and intolerable heat. Inside the house, six members of a family were trapped.

* * *

The first time I ever googled my name, I discovered another Phil Brideaux, whom I’d never heard of. I was named after my great grandfather, Philip John Brideaux (1866-1946), and yet here was another Philip John Brideaux from Sault Ste. Marie, and somehow associated with the Sault Steelers — a team in the Northern Football Conference league of Ontario.

Phil’s wife, Marilyn, was equally curious about me. She had two important questions on her mind when she messaged me: who the heck was I? And what was I doing with her husband’s name? And so it happened that I traveled to Sault Ste. Marie to meet Marilyn on a rainy, October weekend not long after the leaves had turned.

* * *

The area in and around Sault Ste. Marie reminds me of Bragg Creek, Alberta (near where I grew up), except for being punctuated by the searching fingers of the western end of Lake Superior. This region is part of the traditional lands of the Ojibwe people: the low, rolling, boreal foothills of the Canadian Shield curving around the taupe beaches and grey-blue lakescapes of Batchawana Bay. The city itself looks south over the St. Marys River towards Michigan, and west over Whitefish Bay — southeast of where the Great Lakes freighter SS Edmund Fitzgerald broke in two and sank in a fierce winter storm in 1975.

At Sault Ste. Marie, you have the choice of taking the Trans Canada Highway east toward Sudbury, or north and then west to follow the long, curving shore of the lake to Thunder Bay. South will take you across the International Bridge to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and down Interstate 75 toward Saginaw and Flint, and eventually Detroit, far to the south.

These are the environs in which Edwin Charles Brideaux settled, after a winding journey that took him from Jersey, Channel Islands, to New England and then Québec. He was the second Brideaux to venture to Canada, having been preceded by my great grandfather Philip John (1866-1946), who worked briefly on the Gaspé Peninsula in the late 1880s, shortly before his subsequent adventures as an army cook in South Africa.

Edwin and his wife Phyllis Marie Chestle had six children, of which Philip John was the youngest. It might have been the case that Edwin and Phyllis decided to name Philip after Edwin’s uncle, Philip John Brideaux, of Hartford County, Connecticut (son of Elias Jean Brideaux the Elder, 1806-1877, of Jersey, Channel Islands). That’s because Edwin’s first trip to North America had been with his brother Walter to New England, where they worked on Philip John’s dairy farm.

Marilyn Baker met Phil in Sault Ste. Marie when he worked as a rail car checker for the Algoma Central Railway. “That meant that he went through a pair of running shoes every three months because he walked up and down the yard, checking the numbers of the cars and putting stickers on them that said ‘this car’s going on that train,’ and ‘this one’s going on that train.’ He did that for a number of years. Then he got a job with what then was called Dominion Bridge. And I don’t understand exactly what it was that he did there, but it’s now a subsidiary of Essar Steel Algoma,” Marilyn explains.

Marilyn and Phil married in June, 1968. It was clear to her that Phil took after his father Edwin’s temperament as a self-reliant man who preferred to forge his own path. “He didn’t like being told what to do,” she says. “He wanted to be his own boss. So he decided to quit working for other people and try ventures of his own. Some were successful, some were not!” She laughs.

One of those ventures was to become a distributor for Loto-Canada, a 1970s national lottery. Together they sold lottery tickets from Sault Ste. Marie to Tobermory, on the Bruce Peninsula. Phil also began working with the Soo Greyhounds, a team in the Ontario Hockey League, and then became heavily involved with the Sault Steelers football team. “He became President of the Executive,” says Marilyn. He was not only president, but sold team advertising, managed ticket sales and collection, manned the public address system at games, and managed the team’s travel for road games.

“And he drove their team bus,” she adds. “I think if they’d asked him to play he would have tried that too. He used to bring the bus home and park it in our driveway, when they’d come back from a road trip, and the kids would get paid a little to help clean the bus. And then all the shirts came into my basement, and I washed them and sewed them all back together. It was a family venture.”

By this time, Phil had become a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Junior Chamber of Commerce. With the lottery winding up, he moved on to a new venture: photography.

“He loved just wandering in the bush and taking pictures. He’d lie down on his stomach and take pictures of some little red berry attached to some leaf, or climb through brambles and everything, to get just the right picture of this little waterfall,” says Marilyn. “Sometimes it would take him a long time to either get to his destination or get home because he’d do all these little side-treks whenever he’d see something off the side of the highway.”

His business model was to offer his services as a school photographer, while also running a photo processing lab to handle the picture orders. True to his workaholic self, Phil began crisscrossing Northern Ontario, serving clients at primary and secondary schools, logging thousands of highway miles. However the competition was fierce, and growing all the time. By 1981, the business was failing, and Phil and Marilyn were forced to declare bankruptcy.

“We lost our house, we lost our vehicles, we lost everything. So we had to rent a house, which we did through 1982, when the bankruptcy was discharged. Phil went to work for one of his competitors as a school photographer to help pay the rent.”

But of course, Phil was already working on other ideas. The first was becoming a photographer-sales rep for a Toronto-based company which produced yearbooks for church congregations. When he wasn’t photographing for his school photography employer, he was on the road selling yearbook packages and photo services to churches around Northern Ontario.

And somewhere between folding his business and starting the new employment, he’d accidentally become a band manager for two acts in the entertainment business.

“Phil’s best friend’s wife had a friend who was a singer. And this singer was upset with her manager. Somehow or another Phil got pulled in, and became her new manager. And then she had another fellow that she knew who was on the music circuit as well. His name was Eric Shane, and he had a group called Eric Shane and the Shane Gang [everyone in the room laughs]. And he was looking for a manager too, so everything came together.”

With his two photo jobs and two management gigs, as well as his role with the Sault Steelers, Phil was very busy, and constantly on the road. “He was traveling all the time, and he’d have to go back and forth between communities in Northern Ontario and home here, so many times, that he was burning the candle at both ends,” says Marilyn.

* * *

Burning the candle at both ends was what Phil was doing the early morning of November 18, 1982 when he spotted the house fire.

In 1999, I photographed a group of firefighters as they kicked their way into a burning tenement building on Sherbourne Street in Toronto. Fully suited and carrying a charged handline, they fought their way upstairs to the source of the fire in a bedroom, and knocked it down. It wasn’t until they had ventilated the smoke out a broken window (by setting the hose spray to mist), that they discovered the body on the bed. Finding and rescuing people trapped inside a burning structure is difficult enough as it is for professional firefighters.

That’s why it’s a remarkable feat that Phil and the other man managed to get far enough inside the burning house to rescue one of the family members: a six-year old boy.

The other five members of the family, trapped in the flames, could not be reached, and did not survive.

* * *

Phil’s participation with the Junior Chamber of Commerce and the Steelers reflected his dedication to the life of the community and its youth. His many business ventures reflected his dedication to supporting his family as a self-reliant entrepreneur who never wanted to depend on anyone else. Yet it’s hard to estimate the impact on the psyche of an extroverted man faced with what Phil faced in the early hours of that November day. He could not help but carry with him the memories of what he saw and heard in the fire, even as he forged ahead with his busy routine through the Christmas season of 1982. He was already tired out enough from his many responsibilities, as well as managing the bankruptcy. Now he would have this traumatic experience to process as well.

A little over two months after the fire, on the late afternoon of January 31, 1983, Phil was taking both school pictures and church pictures in Sudbury, and had to come back to Sault Ste. Marie to ensure that his singer’s gig at the Holiday Inn was finalized. He told Marilyn to expect him between 7:30 and 8:00 PM. It was a bright, sunny and mild winter afternoon as Phil drove west from Sudbury.

Somewhere around Espanola, he rolled down his driver side window to keep his weary eyes from drooping.

* * *

“I was over at a house five blocks from where we lived, doing my ceramic class, when they knocked on the front door,” says Marilyn quietly. “They tracked me down to that house. I was in the basement in my class, and the owner of the house said, ‘Marilyn there’s a couple of police officers at the door that want to talk to you.’ And as soon as I was walking up the basement stairs, towards the door, I knew what it was, because I saw Phil’s best friend, Bob, standing with the officers. And the first thing that went through my head was, I want my mommy!”

There’s a silence in the room. There are 33 years of grief and sadness bound up in the silence. Marilyn’s eyes are brimming over.

“At first, the police thought that Phil had come around the bend, and out from the shadow of a rock cut, into the afternoon sun. They thought perhaps he got disoriented. But when they did their reconstruction, the marks on the road and the location of the pieces of the two vehicles didn’t match that theory.”

The eastbound driver survived the collision, but with grave injuries.

* * *

Despite a February blizzard, people who knew Phil came from all over the region to his visitation. They stood in line, out in the cold, for an hour, to pay their respects. The turnout at his funeral the next day was equally large.

“The funeral procession from the church to the cemetery was so long that we had to have police cars at the front and police cars at the back,’ says Marilyn. “But that’s what happens I guess when you’re only 38 years old. And you still have a vast circle.”

* * *

Later that Spring, Marilyn accepted the Commissioner’s Citation for Bravery from the Ontario Provincial Police on behalf of Phil for his heroic actions in the Garden River house fire. Thirteen years later, Phil was inducted posthumously into the Northern Football Conference Hall of Fame for his many roles with the Sault Steelers. As a friend wrote in the Sault Star shortly after his death, “There is no question that he was the team’s most valuable member.”

Marilyn keeps a space for him in her home in Sault Ste. Marie, where she lives quietly next door to her children. Out of her abundant generosity, she lets me sleep in this room for my visit. I sit quietly and cautiously in the middle of the space, gazing at the photos, the awards and the mementos of the man with whom I share a name. Phil Brideaux is my third cousin, twice removed. And I’m certain his vibrant spirit still whistles in the wind through the boreal forests of Northern Ontario, and across the waters of Lake Superior and Georgian Bay.

#marilyn brideaux#phil brideaux#philip brideaux#philip john brideaux#sault ste marie#sault steelers#soo greyhounds#edwin brideaux#edwin charles brideaux#phyllis marie chestle#phyllis chestle#jersey channel islands#jerseyci#heritage jersey#heritagejersey

0 notes

Photo

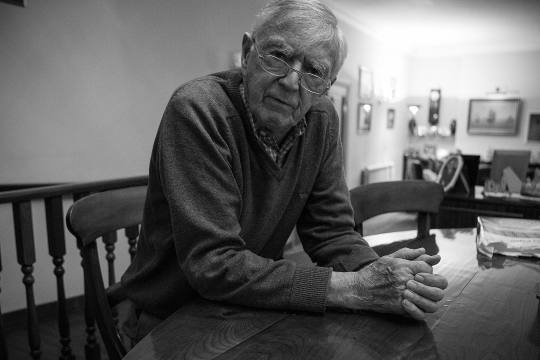

Charles Edwin: The Brideauxs in Ontario Part 1

The startling photo dominates the front page of the Ottawa Citizen for August 3, 1982. On Somerset Street West, an Ottawa Fire Department ladder truck sits amid the rubble of the tailor shop into which it has crashed. Debris covers its roof. To the fire truck’s left sits the remains of the van it first collided with in the intersection, causing the van to crash into a pole.

Below this photo is another photo, showing rescue workers extricating the driver of the smashed van. The driver is 52-year old Charles Edwin Brideaux.

Thirty-four years later, I’m sitting with him in Sault Ste. Marie, in Northern Ontario, near the eastern edge of Lake Superior.

“When I hit the pole, my son’s friend went out the side door and landed at the back end of the fire truck wheels. Another foot and she’d have been under them. She had five broken vertebrae,” says Charles. “Barry ended up with a dislocated, broken shoulder. And I stayed for 13 days in the hospital.”

* * *

Charles Edwin Brideaux is the eldest son of Edwin Charles Brideaux, who in turn was one of the youngest sons of Elias Jean Brideaux the younger.

In 1905, Edwin left Jersey for the second time and crossed the North Atlantic for Paspébiac, on the southern coast of the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec. Elias Jean had more or less compelled Edwin take an indenture on a local farm run by an acquaintance.

Edwin was not happy about it. He had previously emigrated with his older brother, Walter Brideaux, to the United States, where the two brothers went to work on the dairy farm of their uncle, Philip John Brideaux (1852-1910). This particular Philip John (one of many in the Brideaux tree) emigrated from Jersey some years before and settled with his wife May in Hartford County, Connecticut. There, Philip established the first herd of Jersey cattle in the United States.

Edwin did not enjoy Connecticut. Walter stayed, but Edwin returned to the Channel Islands, hoping to work on the family farm, and perhaps even one day inherit it.

His father was not pleased to see him back.

Elias Jean had made it a point to send his sons away one by one as they came of age, and insisted that they make their own fortune somewhere in the world. As Edwin apparently had not yet done so, he was not welcome back at L’Amiral.

“My dad wanted to stay,” says Charles. “And Elias Jean said ‘No, you’re going to go back. You’re going to go work for this farmer for three years for food, clothing and tobacco. And when you’re done there, you can do what you want.’”

So back Edwin went. He never again returned to Jersey, and Elias Jean died the same year Edwin’s indenture ended. True to Elias Jean’s wishes, his property passed to his eldest son Alfred John, and later to Alfred’s second son Lewis Elias.

Edwin spoke little of Jersey. “All he ever talked about of Jersey was the shore,” says Charles. “He never talked about the rolling hills, or the mountain, or Elizabeth Castle, or nothing. All he talked about was going down to the shore for the seaweed.”

Vraic: the Jèrriais word for the seaweed harvested by farmers from Jersey’s beaches, and spread as fertilizer over the island’s potato fields. During permitted times twice yearly, farmers gathered on the beaches from dawn until dusk and hauled up seaweed by horse cart, by hand, and in modern times by tractor. As a young boy, Edwin would have helped his family load up the carts with the vraic that washed up in abundance on the shores of St. Ouen’s Bay, and haul it back to the farm for spreading.

* * *

When his three year indenture on the Paspébiac farm was finished, Edwin ventured further inland up the St. Lawrence River to Montréal, Québec, where he landed a job repairing industrial scales. Algoma Steel in Ontario bought one, and Edwin was sent to Sault Ste. Marie to help install it and repair it. When he completed his assignment, Algoma Steel asked him to stay. Edwin decided to accept their offer and settled in the Sault — nearly 2000 kilometres west from where he’d originally started. He didn’t escape the snow, but he did meet and marry Phyllis Marie Chestle.

Together they had six children and Edwin settled down into family life. Sue was the eldest. Charles Edwin was the second eldest. Philip John was the youngest. When Charles was a toddler, Phyllis would load a roast beef in the undercarriage of his baby buggy and the family would take the International Transit Company ferry across the river to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, to visit her sister on Sundays.

In addition to becoming a father, Edwin became a gardener, and a Scout master. In Sault Ste. Marie, basic bushcraft was not a difficult skill set to come by, and Edwin formed a scout troop and established Camp Brideaux by the time Charles was two years old. “The boys used to come, and we’d want to go with them,” says Charles. “Dad would say ‘No, you can’t, you’re not old enough.’ We couldn’t wait be eight years old, every one of us wanted to get into that. Because those boys had so much fun with my father.” Today, Camp Brideaux no longer exists, but the road leading into the property is still visible from Baseline Road between Town Line and Airport roads on the western edge of Sault Ste Marie.

* * *

When Charles came of age in the late 1940s, he went to work for Canada Steamship Lines as a stevedore. There he helped load and unload the CSL freighters that plied the Great Lakes from Fort William (later to become Thunder Bay), at the head of Lake Superior, to Montreal on the St. Lawrence River.

“I was the guy who got 45 cents per hour for his work. Not until 1947 did they give us all a dollar an hour or so, for eight hours a day, for an eight-hour pay. But you never worked eight hours,” says Charles. “You’d work half an hour, and then you’d sit down for an hour. You sat around the room like this, 30 men. If a boat came in, you had eight hour’s work. But if a boat didn’t come in, you didn’t have that work.”

* * *

The Great Lakes are a spectacular feature of northeastern North America, amounting to a chain of giant, freshwater inland seas containing almost all the traits of the open ocean. Together with the St. Lawrence River, which drains the Great Lakes into the North Atlantic, shipping access reaches inland to the U.S. Midwest, connecting to westbound rail routes. A myriad of small rivers drain into the Great Lakes Basin, giving smaller boats access further inland to other communities west towards Manitoba and the U.S. Midwest, south to the American inland waterways, and north to James Bay and Hudson Bay. American author Holling Clancy Holling celebrated this in his 1941 children’s book, Paddle-to-the-Sea, which was made into a film in the late 1960s by the National Film Board of Canada.

During the Second World War, the Great Lakes were a giant whaleback of heavily-travelled shipping routes, anchoring the thriving, wartime manufacturing heartland of Canada and the United States. Iron taconite ore moved downbound from the side-by-side ports of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin, to rust belt cities along Lake Huron and Lake Erie. Coal from West Virginia and Pennsylvania moved upbound from ports like Buffalo, New York, and Toledo, Ohio, to Lake Michigan ports like Chicago, then on back to Duluth. Grain from Western Canada and the U.S. Great Plains shipped from Fort William, Ontario and Duluth to all points along the Great Lakes, and onward overseas.

Two major “gates” on the Great Lakes Waterway regulate the shipping lanes. One is the Welland Canal, bisecting the Niagara Peninsula to connect Lake Erie with Lake Ontario between Port Colborne and St. Catharines, Ontario. The Welland Canal allows boats to bypass Niagara Falls in a spectacular feat of engineering, consisting of a dramatic run of locks — a kind of giant water escalator.

The other is the Soo Locks, situated on the St. Marys River between Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The Soo Locks allow boats to bypass the St. Mary River rapids and travel between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Both points close in the winter season and reopen after the Spring thaw.

* * *

As a stevedore, Charles helped load and unload Canada Steamship Line lakers docking at Sault Ste. Marie. “We would unload the Winnipeg, the Fort William, the Fort Henry, the Fort York, the Fort Chambly…” says Charles. “The Fort Henry when they built it, it was the fastest ship going at that time. It could make Thunder Bay in eight hours. Then it would unload, load up, and come back in eight hours. Whereas the other boats took 12, 16 hours to get there. It was the same from Sarnia. The Fort Henry made it in eight. These boats would run from Montreal to Thunder Bay, with stops on the way like Thorold, Oakville, Sarnia and Sault Ste. Marie. They’d load canned goods and flour at places like Leamington. Then they’d unload at Thunder Bay, and it would go west by train. Then they’d load up again at Thunder Bay and go back down to Montreal.”

The most frequent commodity Charles helped load was the Algoma steel produced in Sault Ste. Marie. “We would load Algoma steel on the deck. Five feet high,” he recounts. “The ship would take it off as it went downbound. We had a one thousand-square foot warehouse, and it would be full by the time Winter came. Flour. All the stuff from Algoma steel. It would be full. And then we’d would dish it out every week. Every day, dish something out to somebody. When the 23rd of December came — when everybody else got laid off — there were four kept on. Myself, the foreman, the girl in the office, and the agent. Say a guy would come in, wants 30 bags of flour. He’d just pick up a pallet, set it on his truck and away he’d go. Someone comes in, wants 30 bags of sugar, it’d be the same thing.”

And sometimes accidents happened.

“Yeah, the Fort William accidentally dumped the steel over in Montreal once. We had loaded steel on the top deck, and at Montreal, the mate came in and he said, ‘I can’t open the doors ‘til they take the steel off the top,’ and, the other guy says, ‘Open the doors,’ and the mate says, ‘No can’t do it.’ The other guys says, ‘Yeah, you gotta open the door.’ Well. They opened the door and the bolt just went right over. Water pouring in. They just went like that. Tipped over sideways. And what a mess to clean up. Imagine, they had all that steel on there — let alone they had all the canned goods, the flour, everything inside the boat, yeah.”

Charles is referring to regulating the ship’s ballast when unloading cargo. The accident to which he refers happened on September 14, 1965, around 4:30 AM. The September 15, 1965 Montreal Gazette reported that shortly after the ship began unloading, a large explosion “turned the ship into a cauldron of flames,” after which the laker rolled to one side and partially sunk. Five sailors perished in the inferno. George Wharton, writing on the Great Lakes and Seaway Shipping website boatnerd.com, explains that the capsizing occurred first, as the “cargo was being moved to the upper deck at the same time as ballast was being pumped, making the vessel unstable.” The explosion that followed was a load of powdered calcium chloride on the ship mixing with the water as it capsized. This released a large quantity of highly volatile gas which caused the giant explosion and fire.

“We were lucky at Sault Ste. Marie. We were ‘high,’ so we didn’t have that problem. Our ramp to get in the boat was steep, going up. Same coming down. You know, our machines would just make it in to get over that hump,” says Charles.

The present shipping industry on the Great Lakes bears little resemblance to the boom years of the Second World War and Cold War. “It’s done. It’s done,” he says. “There’s no more package freighters. It’s mostly by truck. See, a man from Detroit wants a plate of steel. He drives up, picks it up, takes it back to his shop. A man that wants 30 bags of sugar, he has a truck come, he’ll be going to Loblaws or NoFrills [Ontario grocery store chains] with 30 bags, or put it into a warehouse, and the warehouse here will distribute it. Rail is good but it’s slow, and they don’t carry package freight. Rail carries logs, coal, paper, rolls of steel, that sort of thing. When you look at the businesses that are gone from Sault Ste Marie alone, that aren’t here anymore, it’s shocking. Our paper mill is gone.”

Charles retired from Canada Steamship Lines in the early 1970s. “I went 28 years there. And they handed me a pension of 1000 dollars. That was your pension. Not a month. That was your pension. ‘There’s your pension. Do what you want with it.’ So I bought a swimming pool. And it was one of the best thousand dollars I ever spent. I didn’t have to run to the beach with the kids anymore, or nothing, they just hop in their trunks and they’d be in the pool and out. And they’d get in again in a few minutes.”

* * *

Retirement allowed Charles to visit Jersey twice, to see the island from which his father had left behind. “I always wanted to go, and I never could afford it,” he says. “And then my mother said, before she passed away, that I was to take whatever money she left me and go to Jersey. I was married with three kids, but I did exactly that, because that was part of her wish to let me see what Jersey was.”

In Jersey, Charles finally met his cousin Joyce Brideaux and her husband Brian Gilbert, along with their family. “Oh I thought Jersey was wonderful. It was a beautiful time, they showed us the whole country, I saw everything you could have seen, that you’d want to see. Elizabeth Castle and all that.

“I liked the idea of their stores. If you went to the butcher shop, all you got was the butcher. If you went to the fruit store, all you got was fruit. If you went to the potato store, that’s what you got. Potato and onions. And then the only eight miles of four-lane highway, that really struck me.

“But see, first time I went, I was used to traveling on our [Canadian] roads. Well, I told Brian I didn’t want a car. Brian says ‘We’re getting you a car whether you want it or not, we’re not going run you around.’ I didn’t have any trouble with driving on the left. But I had trouble with meeting another car. I didn’t know what to do. There was no place to go, the roads were so narrow. And then finally this one driver stopped, and he said ‘Did you see that little space you’ve passed?’ and I said ‘Yup.’ And he said, ‘When you saw me, you should’ve pulled in there.’ So I backed up and pulled into it.

“The second time I went over, Joyce’s daughter Karen, and her husband David, tried to get me to stay, but I said no. In fact, Uncle Bert [Joyce Brideaux’s father Philip Herbert Brideaux] had asked my older sister Sue, and her husband Charlie, to come and work there, too. And my dad said to Charlie, ‘Look, you can go, but you’re not a Jerseyman. You’ll never get nowhere. You’re not a Jerseyman.’ And Dad drilled that into Charlie.

* * *

Charles and his son Barry, along with Barry’s friends, had driven up to Ottawa in his van for a roller skating competition the first weekend in August, 1982. At about 7:45 PM, as they were driving south on Lyon Street in an intense rainstorm, an Ottawa Fire Department ladder truck, heading east on Somerset Street to a call, t-boned Charles’ van at the intersection. The force of the impact drove the van into a light pole, and the fire truck into a tailor shop doorway, where two men were taking shelter from the rain. All of the firefighters were injured to various degrees, including two who were thrown off the back of the fire truck.

The men taking shelter in the shop doorway were both killed by the fire truck’s impact.

Charles and the fire truck’s driver were both trapped in their vehicles. “They couldn’t get me out. So they took the seat out to get me out,” says Charles. “And it turns out that the driver of the fire truck had a glass eye.”

“He had a glass eye,” I repeat for clarity.

“Yup,” nods Charles. “He had a glass eye. And how did he have a fire truck licence? His buddy took the driving test for him. So that was one of the things that came up in the court case.” That, and Charles had a green light when he entered the intersection.

The court case was to sort out the insurance claims. Charles and Barry, along with Barry’s friends from the van, all had lawyers. Charles returned to Ottawa some months later for the hearing. He and the others were eventually to receive a settlement, but whether, and how much, had to be worked out in court.

At the Ottawa courthouse, Charles sat in the hallway, outside the designated courtroom, waiting for his case to come to the top of the list. When it did, the Clerk of the Court stepped out into the hall to summon him. The Clerk was shorter in stature, in his late 70s, with a receding hairline and glasses. He stood in front of Charles. When he spoke, he spoke with a Jèrriais accent.

“I’m Mr. Brideaux,” my grandfather Wilfred Philip said to Charles Edwin. “And I’m looking for this young Mr. Brideaux.” Charles got up and unexpectedly found himself shaking hands with the man who turned out to be his third cousin, and the two walked into the courtroom together.

#jersey#jersey channel islands#jerseyci#heritage jersey#heritagejersey#jersey heritage#Jèrriais#vraic#gaspe peninsula#gaspe#paspébiac#paspebiac#saultstemarie#sault ste. marie#great lakes#greatlakes#brideaux#canada steamship lines

0 notes

Photo

La Route de Ste. Marie, Bailiwick of Jersey, Channel Islands

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Eisteddfod

In the midst of Jèrriais poetry recitation and singing, during Jersey's Autumn Eisteddfod, I slip into the kitchen at the back of St. Ouen Parish Hall. I'm looking for the source of the loud laughter and Jèrriais banter I've heard leaking out of the swinging door.

In the chilly, drizzly November afternoon, the kitchen is a glowing, warm cocoon of steamy windows, simmering pots, and a number of women busy with cooking and baking. The aroma filling the space travels in through the nostrils and straight to the marrow. At the centre of the clanging cookware and laughter is Joan Tapley. She's stirring a large pot of pea soup. Everything about the scene suggests that this will be the apotheosis of pea soup.

Joan assumes my sudden presence is all for a good cause and lets me take photos of her.

Later I'm welcomed into a dining area upstairs, where members of the organizing committee for the afternoon sit around a large table to break bread. Joan's pea soup is just part of the feast. Most of those here are members of l'Assemblée d'Jèrriais, and I struggle to follow their conversation with the small amount of French I know. It's not much help when listening to a centuries-old Norman dialect with old Norse words. The language is the foundation of their fellowship, the language of my grandfather and ancestors. I'm overwhelmed just to be sitting here, witnessing this.

Not surprisingly, the pea soup keeps me warm for the rest of the trip.

#Jèrriais#jerriais#jersey french#jerseyci#jersey channel islands#jersey heritage#heritage jersey#eisteddfod

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The First and The Last

I’m standing on a tract of land on the windswept northwest bluffs of the Bailiwick of Jersey, called Les Vaux Brideaux. It’s a small valley leading down from potato fields to the flat farmlands along the coast of St. Ouen’s Bay. It’s a surreal moment, because I’m researching my ancestors in Jersey, and this tract of land is where it all began.

The land appears to be associated with Pierre Brideaux, who barely appears in the island records, noted only as the father of his son, also named Pierre (1645-1682). Pierre the younger was born during the English Civil War, when Cromwell’s New Model Army battled Royalist forces in England. The Channel Islands in no way escaped the conflict, so Pierre the elder lived in interesting times.

Pierre the elder has no apparent baptism record in Jersey, and may have come from France, making him quite possibly the first Brideaux in Jersey. His descendants would increasingly migrate outwards across the island and then around the world. Three hundred and seventy-one years and thirteen generations of Brideauxs later, I’m stepping back onto this point of origin. And I’m thinking about my meeting the previous day with the last living Brideaux in Jersey.

“I am the only survivor of the Pierre Brideaux who came here in the 1600s,” declares Joyce Brideaux, during my visit the previous day. At 95 years old, she is the last Brideaux born a Brideaux — living here, where it all began.

I only find out about Joyce on my last day on the island during my February 2015 visit. Her husband Brian has recently passed away. Her daughter Glenda phones BBC Jersey to track me down after hearing me interviewed about my ancestral research, and my interest in the surviving Jèrriais community. Now another year has passed before I’m able to return and visit her, and I’m relieved that I can.

As I’m ushered in to meet her in the sitting room of a large house in St. Martin Parish, I can’t help but feel a sense of awe. She is my oldest living relative. She is responsible for the most comprehensive accounting of the Brideaux family to date, found online in Jerripedia. She was a pillar of l'Assemblée d'Jèrriais for many years along with her husband. She was born in 1921, the year my grandfather left the bailiwick for Canada. And she has the aura and the countenance of a genuine Jèrriais elder.

Joyce has lived in St. Martin Parish since 1949, when she married Brian Gilbert. They farmed for a number of years before becoming produce wholesalers. By 1960 they had more time to themselves, which is when they joined l'Assemblée d'Jèrriais — because, of course, they spoke Jèrriais.

“I have always spoken it from the cradle,” she says. “When I first started speaking, it was in Jèrriais, and my maternal grandfather — who was a great speaker — he was a Renouf, and he spoke nothing else but Jèrriais all his life. He wasn’t interested in English. Even though he was a good churchman, and went and read lessons at church, when he was speaking to anyone he always spoke in Jèrriais. My father, my grandfather, my mother and my grandmother, they were all Jèrriais people. Therefore we spoke Jèrriais all the time. My father-in-law spoke very good Jèrriais, but it was Jèrriais from La Rocque. And it wasn’t the same as the Jèrriais that we used to speak at St. John’s.”

Jèrriais has its own varieties?

“Oh, very much so,” she says. ”St. Ouen’s has its own accent. La Moye, St. Brelade’s, has got an accent as well. And La Rocque has different words for different articles, and different things or places. Town [St. Helier], of course, doesn’t speak Jèrriais, only what they’ve learned out of books. And it’s not the same thing. But St. Peter’s, St. Mary’s, St. John’s, St. Lawrence, and Trinity are very much the same. St. Martin’s, a little bit different, but not much. St. Saviour’s doesn’t speak Jèrriais. And St. Clement’s, very little.”

Joyce was fortunate to have both the language spoken in her home as well as in her school. This was not the norm for many Jèrriais-speaking families challenged by the growth of an Anglophone public sphere on the island.

“I was lucky. In the 1930s, when you went to school, it was frowned upon to talk in Jèrriais, because most of the teachers were English and they couldn’t understand what you were saying. So, if you were talking to somebody else in the playground or in school, and you spoke in Jèrriais, they didn’t know if you were talking about them. And so they said they didn’t want to have any Jèrriais spoken in the school, and that put a damper a bit on the Jèrriais. But for me, my teacher was from St. Ouen’s, and we always used to converse in Jèrriais. I used to go on the bus, and she was on the same bus as I was, going to school. So we always had a good chat in Jèrriais, and I never lost my Jèrriais.”

So it’s little surprise that Joyce and her husband Brian later became prominent members of l'Assemblée d'Jèrriais. They worked hard in maintaining the links forged by Norman speakers across the Channel Islands and mainland France.

“After Brian and I joined l'Assemblée in 1960, Brian became President of one department of l'Assemblée, and I became the secretary there. And then later he became the President of the whole committee, and I became the secretary for that. We used to go to the annual general meetings where he’d chair the AGM and I’d read out the minutes of the whole year. We had a great time, we traveled a lot in Normandy and saw our Normandy cousins. And we always went to Guernsey for their lunches and dinners. Brian used to have to speak in Jersey French, and of course the Guernsey people had to speak in Guernsey French, so we came to understand each other very well.”

Their travels on mainland France, both for l'Assemblée and for leisure, gave them opportunities to introduce Jèrriais to people who had no more heard of Jersey French than the many British who regularly vacationed on Jersey’s beaches. And to have some fun with that.

“Quite often we were in a restaurant, and we would start talking in Jèrriais. And of course all the tables around us would stop to listen because French people couldn’t make out which department of France we came from. And they used to say, ‘Oh, they must come from the south?’ And then they’d say, ‘No they can’t come from the south, because they don’t pronounce the end of their words. They don’t pronounce the t’s.’ Then the next day, if we went to breakfast or something, we’d be speaking in English, and then they’d say, ‘Well that was a funny language they spoke yesterday but they can still speak English just the same.’ Ah, we used to run them! Joke with them all over the place. It was great fun to do that.”

If Joyce is the last Brideaux, what happened to all the rest?

It seems they’ve all left the island or passed on. Some settled in Quebec. Others left and settled in Wales or New England. Joyce’s clan, possibly the largest clan of Brideauxs ever seen on the island, mostly left too. Her grandfather, Elias Jean Brideaux (1849-1908) had fourteen children, of which her father (Philip Herbert) was the second youngest. Elias Jean, who was a school attendance officer, sent his sons away one by one as they came of age, and insisted that they make their own fortune somewhere in the world. No one came back, but these expatriates are why Brideauxs are now to be found everywhere else.

“Uncle Walter and Uncle Fred went to America. Uncle Edwin went to Canada. Uncle Winter went to India. Uncle William to South Africa. Uncle Arthur went to St. Malo [France] and died there,” says Joyce, accounting for some of them.

And it turns out that I’m not the first Philip Brideaux to make a pilgrimage back to the homeland.