#paspébiac

Text

Retour à nos racines

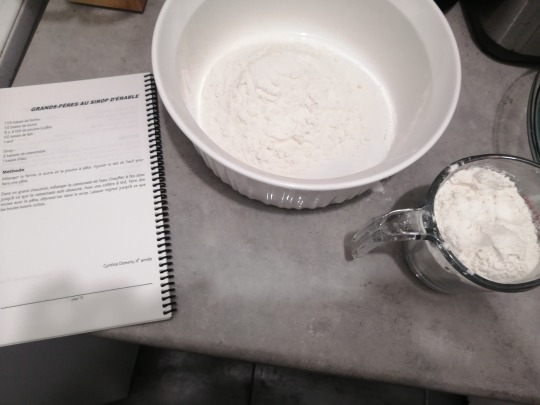

Lors d'une soirée spéciale, j'ai décidé de faire un saut dans le passé culinaire de mes origines, en préparant le fameux "Grand-père au sirop d'érable". Pourquoi ce plat, me demanderez-vous ? Eh bien, dans le coin d'où vient mon père, Paspébiac, les gens ne rigolent pas avec les desserts. Ils adorent tellement cuisiner qu'ils pourraient presque faire sauter des crêpes en dormant !

Ma grand-mère me le servait souvent, et chaque bouchée était un aller-retour direct pour l'enfance. Mais d'où vient donc cette douceur sucrée ? C'est un savoureux mélange de cultures entre les colons européens et les autochtones. Quand les premiers ont posé le pied sur ces terres, ils ont découvert non seulement un nouveau monde, mais aussi des habitants qui avaient déjà tout un savoir-faire culinaire.

Imaginez la scène : les colons, un peu perdus avec leur pâte à pain, rencontrent les autochtones qui, entre deux conseils de survie, leur montrent la magie de la sève d'érable. Et voilà comment le sirop d'érable a fini par se frayer un chemin dans leur pâte ! Depuis, cette recette se transmet de génération en génération, tel un secret de famille bien gardé. Elle est devenue une fierté québécoise, au point que même les écureuils en sont jaloux.

Ainsi, chaque fois que je prépare ce dessert, je rends hommage à cette belle histoire de partage et de gourmandise. Et je vous assure, il n'y a rien de mieux pour sucrer une soirée entre amis !

Recette :

1 ½ tasse de farine

3c. à thé de poudre à pâte

½ tasse de beurre

½ tasse de lait

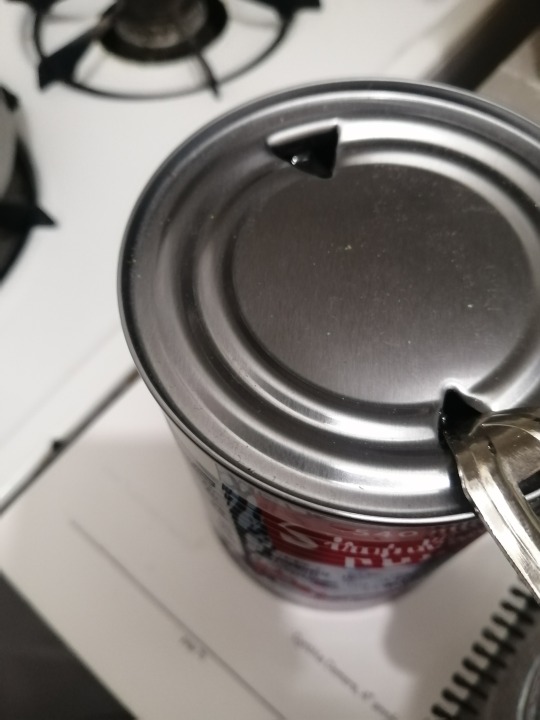

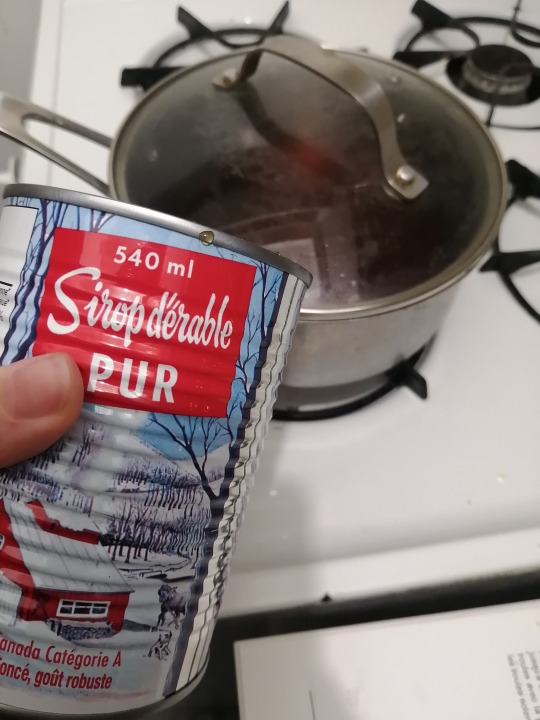

1 ½ sirop d’érable

1 tasse d’eau

Mélanger la Farine, le sucre et la poudre à pâte. Ajouter le lait et le beurre pour faire une pâte.

Mettre dans un grand chaudron l’eau et le sirop d’érable, puis porter à ébullitions.

Avec une cuillère faire des boules de pâte et tremper la cuillère pour les relâcher dans le bouillon de sirop.

Après que 5 minute c'est écoulé ont peu les sortir un par un et les placer dans un bol résistant à la chaleur.

LAB NUMÉRO 4

0 notes

Photo

Truck Tuesday!

Paspébiac, Québec, Canada

https://goo.gl/maps/UZzCEM5rZfW4mHyg7

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

J’en avais plein les yeux! #coucherdesoleil #sunset #gaspesie #gaspesiejetaime #paspébiac #soleil #sun #cestlete #itssummer #summertime #eblouissant #magnifique https://www.instagram.com/p/By_gMd6lzIl/?igshid=ek8gxwndy10

#coucherdesoleil#sunset#gaspesie#gaspesiejetaime#paspébiac#soleil#sun#cestlete#itssummer#summertime#eblouissant#magnifique

0 notes

Photo

Pissing singles cisnădie and pee woman Croatia

0 notes

Photo

Bus Day! Sunday!

Paspébiac, Quebec, Canada

https://goo.gl/maps/CdsJsJEs8JxzfVsp7

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

hockey contre le racisme.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Se régaler d’un bon spaghetti gratiné au restaurant l’Ancre, du Site historique du Banc-de-Pêche de Paspébiac. Ça débute bien le week-end. Vous connaissez ce lieu magnifique, porteur de l’histoire gaspésienne? ➡️ Visitez leur site : www.shbp.ca Et allez-y seul ou en famille! #sitehistoriquedepaspebiac #patrimoine #patrimoinemondial #restaurant #gaspesie #gaspesiejetaime #gaspesiegourmande #quebecoriginal #quebecmaritime #pêche #histoire #history #paspébiac #visite https://www.instagram.com/p/By-0zXelPi9/?igshid=komuu1op0d4o

#sitehistoriquedepaspebiac#patrimoine#patrimoinemondial#restaurant#gaspesie#gaspesiejetaime#gaspesiegourmande#quebecoriginal#quebecmaritime#pêche#histoire#history#paspébiac#visite

0 notes

Photo

Charles Edwin: The Brideauxs in Ontario Part 1

The startling photo dominates the front page of the Ottawa Citizen for August 3, 1982. On Somerset Street West, an Ottawa Fire Department ladder truck sits amid the rubble of the tailor shop into which it has crashed. Debris covers its roof. To the fire truck’s left sits the remains of the van it first collided with in the intersection, causing the van to crash into a pole.

Below this photo is another photo, showing rescue workers extricating the driver of the smashed van. The driver is 52-year old Charles Edwin Brideaux.

Thirty-four years later, I’m sitting with him in Sault Ste. Marie, in Northern Ontario, near the eastern edge of Lake Superior.

“When I hit the pole, my son’s friend went out the side door and landed at the back end of the fire truck wheels. Another foot and she’d have been under them. She had five broken vertebrae,” says Charles. “Barry ended up with a dislocated, broken shoulder. And I stayed for 13 days in the hospital.”

* * *

Charles Edwin Brideaux is the eldest son of Edwin Charles Brideaux, who in turn was one of the youngest sons of Elias Jean Brideaux the younger.

In 1905, Edwin left Jersey for the second time and crossed the North Atlantic for Paspébiac, on the southern coast of the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec. Elias Jean had more or less compelled Edwin take an indenture on a local farm run by an acquaintance.

Edwin was not happy about it. He had previously emigrated with his older brother, Walter Brideaux, to the United States, where the two brothers went to work on the dairy farm of their uncle, Philip John Brideaux (1852-1910). This particular Philip John (one of many in the Brideaux tree) emigrated from Jersey some years before and settled with his wife May in Hartford County, Connecticut. There, Philip established the first herd of Jersey cattle in the United States.

Edwin did not enjoy Connecticut. Walter stayed, but Edwin returned to the Channel Islands, hoping to work on the family farm, and perhaps even one day inherit it.

His father was not pleased to see him back.

Elias Jean had made it a point to send his sons away one by one as they came of age, and insisted that they make their own fortune somewhere in the world. As Edwin apparently had not yet done so, he was not welcome back at L’Amiral.

“My dad wanted to stay,” says Charles. “And Elias Jean said ‘No, you’re going to go back. You’re going to go work for this farmer for three years for food, clothing and tobacco. And when you’re done there, you can do what you want.’”

So back Edwin went. He never again returned to Jersey, and Elias Jean died the same year Edwin’s indenture ended. True to Elias Jean’s wishes, his property passed to his eldest son Alfred John, and later to Alfred’s second son Lewis Elias.

Edwin spoke little of Jersey. “All he ever talked about of Jersey was the shore,” says Charles. “He never talked about the rolling hills, or the mountain, or Elizabeth Castle, or nothing. All he talked about was going down to the shore for the seaweed.”

Vraic: the Jèrriais word for the seaweed harvested by farmers from Jersey’s beaches, and spread as fertilizer over the island’s potato fields. During permitted times twice yearly, farmers gathered on the beaches from dawn until dusk and hauled up seaweed by horse cart, by hand, and in modern times by tractor. As a young boy, Edwin would have helped his family load up the carts with the vraic that washed up in abundance on the shores of St. Ouen’s Bay, and haul it back to the farm for spreading.

* * *

When his three year indenture on the Paspébiac farm was finished, Edwin ventured further inland up the St. Lawrence River to Montréal, Québec, where he landed a job repairing industrial scales. Algoma Steel in Ontario bought one, and Edwin was sent to Sault Ste. Marie to help install it and repair it. When he completed his assignment, Algoma Steel asked him to stay. Edwin decided to accept their offer and settled in the Sault — nearly 2000 kilometres west from where he’d originally started. He didn’t escape the snow, but he did meet and marry Phyllis Marie Chestle.

Together they had six children and Edwin settled down into family life. Sue was the eldest. Charles Edwin was the second eldest. Philip John was the youngest. When Charles was a toddler, Phyllis would load a roast beef in the undercarriage of his baby buggy and the family would take the International Transit Company ferry across the river to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, to visit her sister on Sundays.

In addition to becoming a father, Edwin became a gardener, and a Scout master. In Sault Ste. Marie, basic bushcraft was not a difficult skill set to come by, and Edwin formed a scout troop and established Camp Brideaux by the time Charles was two years old. “The boys used to come, and we’d want to go with them,” says Charles. “Dad would say ‘No, you can’t, you’re not old enough.’ We couldn’t wait be eight years old, every one of us wanted to get into that. Because those boys had so much fun with my father.” Today, Camp Brideaux no longer exists, but the road leading into the property is still visible from Baseline Road between Town Line and Airport roads on the western edge of Sault Ste Marie.

* * *

When Charles came of age in the late 1940s, he went to work for Canada Steamship Lines as a stevedore. There he helped load and unload the CSL freighters that plied the Great Lakes from Fort William (later to become Thunder Bay), at the head of Lake Superior, to Montreal on the St. Lawrence River.

“I was the guy who got 45 cents per hour for his work. Not until 1947 did they give us all a dollar an hour or so, for eight hours a day, for an eight-hour pay. But you never worked eight hours,” says Charles. “You’d work half an hour, and then you’d sit down for an hour. You sat around the room like this, 30 men. If a boat came in, you had eight hour’s work. But if a boat didn’t come in, you didn’t have that work.”

* * *

The Great Lakes are a spectacular feature of northeastern North America, amounting to a chain of giant, freshwater inland seas containing almost all the traits of the open ocean. Together with the St. Lawrence River, which drains the Great Lakes into the North Atlantic, shipping access reaches inland to the U.S. Midwest, connecting to westbound rail routes. A myriad of small rivers drain into the Great Lakes Basin, giving smaller boats access further inland to other communities west towards Manitoba and the U.S. Midwest, south to the American inland waterways, and north to James Bay and Hudson Bay. American author Holling Clancy Holling celebrated this in his 1941 children’s book, Paddle-to-the-Sea, which was made into a film in the late 1960s by the National Film Board of Canada.

During the Second World War, the Great Lakes were a giant whaleback of heavily-travelled shipping routes, anchoring the thriving, wartime manufacturing heartland of Canada and the United States. Iron taconite ore moved downbound from the side-by-side ports of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin, to rust belt cities along Lake Huron and Lake Erie. Coal from West Virginia and Pennsylvania moved upbound from ports like Buffalo, New York, and Toledo, Ohio, to Lake Michigan ports like Chicago, then on back to Duluth. Grain from Western Canada and the U.S. Great Plains shipped from Fort William, Ontario and Duluth to all points along the Great Lakes, and onward overseas.

Two major “gates” on the Great Lakes Waterway regulate the shipping lanes. One is the Welland Canal, bisecting the Niagara Peninsula to connect Lake Erie with Lake Ontario between Port Colborne and St. Catharines, Ontario. The Welland Canal allows boats to bypass Niagara Falls in a spectacular feat of engineering, consisting of a dramatic run of locks — a kind of giant water escalator.

The other is the Soo Locks, situated on the St. Marys River between Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The Soo Locks allow boats to bypass the St. Mary River rapids and travel between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Both points close in the winter season and reopen after the Spring thaw.

* * *

As a stevedore, Charles helped load and unload Canada Steamship Line lakers docking at Sault Ste. Marie. “We would unload the Winnipeg, the Fort William, the Fort Henry, the Fort York, the Fort Chambly…” says Charles. “The Fort Henry when they built it, it was the fastest ship going at that time. It could make Thunder Bay in eight hours. Then it would unload, load up, and come back in eight hours. Whereas the other boats took 12, 16 hours to get there. It was the same from Sarnia. The Fort Henry made it in eight. These boats would run from Montreal to Thunder Bay, with stops on the way like Thorold, Oakville, Sarnia and Sault Ste. Marie. They’d load canned goods and flour at places like Leamington. Then they’d unload at Thunder Bay, and it would go west by train. Then they’d load up again at Thunder Bay and go back down to Montreal.”

The most frequent commodity Charles helped load was the Algoma steel produced in Sault Ste. Marie. “We would load Algoma steel on the deck. Five feet high,” he recounts. “The ship would take it off as it went downbound. We had a one thousand-square foot warehouse, and it would be full by the time Winter came. Flour. All the stuff from Algoma steel. It would be full. And then we’d would dish it out every week. Every day, dish something out to somebody. When the 23rd of December came — when everybody else got laid off — there were four kept on. Myself, the foreman, the girl in the office, and the agent. Say a guy would come in, wants 30 bags of flour. He’d just pick up a pallet, set it on his truck and away he’d go. Someone comes in, wants 30 bags of sugar, it’d be the same thing.”

And sometimes accidents happened.

“Yeah, the Fort William accidentally dumped the steel over in Montreal once. We had loaded steel on the top deck, and at Montreal, the mate came in and he said, ‘I can’t open the doors ‘til they take the steel off the top,’ and, the other guy says, ‘Open the doors,’ and the mate says, ‘No can’t do it.’ The other guys says, ‘Yeah, you gotta open the door.’ Well. They opened the door and the bolt just went right over. Water pouring in. They just went like that. Tipped over sideways. And what a mess to clean up. Imagine, they had all that steel on there — let alone they had all the canned goods, the flour, everything inside the boat, yeah.”

Charles is referring to regulating the ship’s ballast when unloading cargo. The accident to which he refers happened on September 14, 1965, around 4:30 AM. The September 15, 1965 Montreal Gazette reported that shortly after the ship began unloading, a large explosion “turned the ship into a cauldron of flames,” after which the laker rolled to one side and partially sunk. Five sailors perished in the inferno. George Wharton, writing on the Great Lakes and Seaway Shipping website boatnerd.com, explains that the capsizing occurred first, as the “cargo was being moved to the upper deck at the same time as ballast was being pumped, making the vessel unstable.” The explosion that followed was a load of powdered calcium chloride on the ship mixing with the water as it capsized. This released a large quantity of highly volatile gas which caused the giant explosion and fire.

“We were lucky at Sault Ste. Marie. We were ‘high,’ so we didn’t have that problem. Our ramp to get in the boat was steep, going up. Same coming down. You know, our machines would just make it in to get over that hump,” says Charles.

The present shipping industry on the Great Lakes bears little resemblance to the boom years of the Second World War and Cold War. “It’s done. It’s done,” he says. “There’s no more package freighters. It’s mostly by truck. See, a man from Detroit wants a plate of steel. He drives up, picks it up, takes it back to his shop. A man that wants 30 bags of sugar, he has a truck come, he’ll be going to Loblaws or NoFrills [Ontario grocery store chains] with 30 bags, or put it into a warehouse, and the warehouse here will distribute it. Rail is good but it’s slow, and they don’t carry package freight. Rail carries logs, coal, paper, rolls of steel, that sort of thing. When you look at the businesses that are gone from Sault Ste Marie alone, that aren’t here anymore, it’s shocking. Our paper mill is gone.”

Charles retired from Canada Steamship Lines in the early 1970s. “I went 28 years there. And they handed me a pension of 1000 dollars. That was your pension. Not a month. That was your pension. ‘There’s your pension. Do what you want with it.’ So I bought a swimming pool. And it was one of the best thousand dollars I ever spent. I didn’t have to run to the beach with the kids anymore, or nothing, they just hop in their trunks and they’d be in the pool and out. And they’d get in again in a few minutes.”

* * *

Retirement allowed Charles to visit Jersey twice, to see the island from which his father had left behind. “I always wanted to go, and I never could afford it,” he says. “And then my mother said, before she passed away, that I was to take whatever money she left me and go to Jersey. I was married with three kids, but I did exactly that, because that was part of her wish to let me see what Jersey was.”

In Jersey, Charles finally met his cousin Joyce Brideaux and her husband Brian Gilbert, along with their family. “Oh I thought Jersey was wonderful. It was a beautiful time, they showed us the whole country, I saw everything you could have seen, that you’d want to see. Elizabeth Castle and all that.

“I liked the idea of their stores. If you went to the butcher shop, all you got was the butcher. If you went to the fruit store, all you got was fruit. If you went to the potato store, that’s what you got. Potato and onions. And then the only eight miles of four-lane highway, that really struck me.

“But see, first time I went, I was used to traveling on our [Canadian] roads. Well, I told Brian I didn’t want a car. Brian says ‘We’re getting you a car whether you want it or not, we’re not going run you around.’ I didn’t have any trouble with driving on the left. But I had trouble with meeting another car. I didn’t know what to do. There was no place to go, the roads were so narrow. And then finally this one driver stopped, and he said ‘Did you see that little space you’ve passed?’ and I said ‘Yup.’ And he said, ‘When you saw me, you should’ve pulled in there.’ So I backed up and pulled into it.

“The second time I went over, Joyce’s daughter Karen, and her husband David, tried to get me to stay, but I said no. In fact, Uncle Bert [Joyce Brideaux’s father Philip Herbert Brideaux] had asked my older sister Sue, and her husband Charlie, to come and work there, too. And my dad said to Charlie, ‘Look, you can go, but you’re not a Jerseyman. You’ll never get nowhere. You’re not a Jerseyman.’ And Dad drilled that into Charlie.

* * *

Charles and his son Barry, along with Barry’s friends, had driven up to Ottawa in his van for a roller skating competition the first weekend in August, 1982. At about 7:45 PM, as they were driving south on Lyon Street in an intense rainstorm, an Ottawa Fire Department ladder truck, heading east on Somerset Street to a call, t-boned Charles’ van at the intersection. The force of the impact drove the van into a light pole, and the fire truck into a tailor shop doorway, where two men were taking shelter from the rain. All of the firefighters were injured to various degrees, including two who were thrown off the back of the fire truck.

The men taking shelter in the shop doorway were both killed by the fire truck’s impact.

Charles and the fire truck’s driver were both trapped in their vehicles. “They couldn’t get me out. So they took the seat out to get me out,” says Charles. “And it turns out that the driver of the fire truck had a glass eye.”

“He had a glass eye,” I repeat for clarity.

“Yup,” nods Charles. “He had a glass eye. And how did he have a fire truck licence? His buddy took the driving test for him. So that was one of the things that came up in the court case.” That, and Charles had a green light when he entered the intersection.

The court case was to sort out the insurance claims. Charles and Barry, along with Barry’s friends from the van, all had lawyers. Charles returned to Ottawa some months later for the hearing. He and the others were eventually to receive a settlement, but whether, and how much, had to be worked out in court.

At the Ottawa courthouse, Charles sat in the hallway, outside the designated courtroom, waiting for his case to come to the top of the list. When it did, the Clerk of the Court stepped out into the hall to summon him. The Clerk was shorter in stature, in his late 70s, with a receding hairline and glasses. He stood in front of Charles. When he spoke, he spoke with a Jèrriais accent.

“I’m Mr. Brideaux,” my grandfather Wilfred Philip said to Charles Edwin. “And I’m looking for this young Mr. Brideaux.” Charles got up and unexpectedly found himself shaking hands with the man who turned out to be his third cousin, and the two walked into the courtroom together.

#jersey#jersey channel islands#jerseyci#heritage jersey#heritagejersey#jersey heritage#Jèrriais#vraic#gaspe peninsula#gaspe#paspébiac#paspebiac#saultstemarie#sault ste. marie#great lakes#greatlakes#brideaux#canada steamship lines

0 notes

Photo

Telus expands 5G to Bonaventure, New Richmond and Paspébiac, Quebec

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

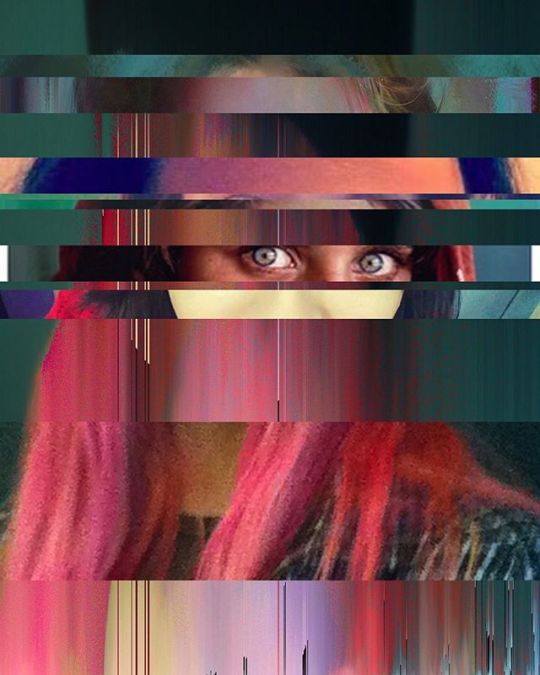

Dans le cadre de Culture à l’école, je me promène dans les classes du Québec pour jaser Bot et art numérique avec les élèves du secondaire. Touchante surprise ce matin dans la classe de Mme Marie-Claude à #Paspébiac. La jeune fille afghane aux yeux verts s'est invitée dans le portrait d'une étudiante! «The afghan girl» est une photo célèbre prise par le journaliste Steve McCurry et qui a fait la couverture du magazine National Geographic en juin 1985. Durant la guerre d'Afghanistan, Sharbat Gula (la jeune fille) a été forcée de quitter son pays vers un camp de réfugiés au Pakistan. 👀 💕 Cette photo est le résultat d’un autoportrait versé dans le dispositif #PortraitRobot #Culture #Bot #afghanistan #nationalgeographic #afghangirl #gaspésie #gaspesiejetaime #glitch #digitalart #art #ai #Google https://ift.tt/2SdwQ2O

0 notes