#Edwin Charles Brideaux

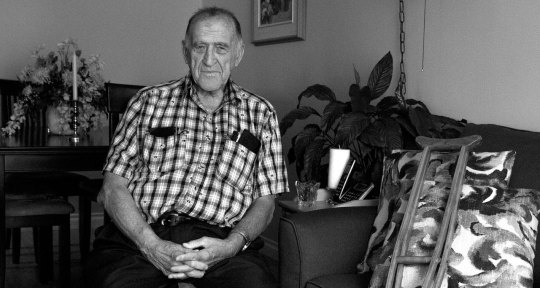

Photo

Charles Brideaux

1929 — 2021

I’ve learned the sad news of the passing of Charles Edwin Brideaux, age 91, of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario on January 1. I wrote about Charles in a previous post, and his adventures as a stevedore during the golden years of shipping on the Great Lakes. Charles was the last of Edwin Charles Brideaux (1887-1966) and Phyllis Marie Chestle’s (1905-1986) surviving children. Having been predeceased by his wife and one of his sons, and having experienced several tribulations, Charles was in every sense a survivor. I will always be grateful for having had the honour to meet and interview Charles.

#Charles Brideaux#Charles Edwin Brideaux#Philip Brideaux#Sault Ste Marie#Edwin Charles Brideaux#JerseyCI#Jersey#Brideaux

1 note

·

View note

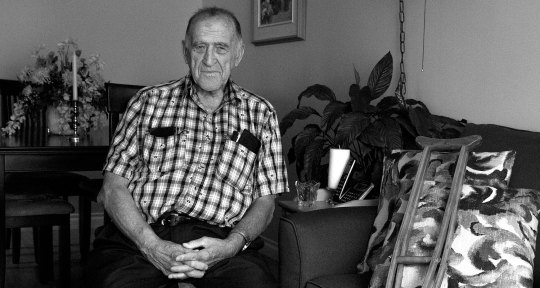

Photo

Phil and Marilyn: The Brideauxs in Ontario Part 2

The house was almost completely on fire. Phil Brideaux could see the flames from his car on the highway. It was about 4:15 AM on November 18, 1982 and Phil was, as usual, on the road. He was returning to Sault Ste. Marie from one his many business trips to Sudbury, Ontario, and was passing through the Garden River First Nation.

Phil wrenched the car over to the side of the road and jumped out before leaping over snowbanks and dashing toward the house. He likely did not have a plan in mind, likely was acting on instinct, and likely had no idea what he was in for. Another passing motorist, a man from Edmonton, happened by about the same time, and jumped out to join Phil. The two shouldered their way into the burning house.

Years ago, when photographing firefighters, I learned that the problem with deliberately entering a house on fire without a self-contained breathing apparatus and some sort of Nomex fabric protection, is that you are putting yourself at great risk of being severely burned or asphyxiated. That’s because the interior of a burning wood frame structure bears no resemblance to dramatized depictions on television and movies: clear sight lines inside; spot fires burning here and there; breathable air; the ability to see and communicate with others; actors jumping through small banks of flames. The tropes are well known, but the real environment of a burning interior is completely hostile to survival.

The smoke from even a smaller fire contained in the corner of one room will eventually fill every cubic inch of a house, thick and black. You will not be able to see your hand in front of your face. You will have no idea what’s in front of you, or where you are. Even one lungful of smoke could knock you flat. Smoke is not a gas like carbon dioxide from a tailpipe. While it does contain poisonous gases, it’s mostly made up of tiny, solid, semi-combusted particles. The particles are hot, will coat the inside of your windpipe and lungs, will cause burning and swelling, and will quickly suffocate you if you are not pulled out in time.

The other problem is sometimes superheated air (of which one lungful will be fatal), or at least, very high heat from the flames. If you’ve ever been close to a building on fire, you may have felt the intense heat radiating off the structure. The heat alone can easily burn exposed skin if you are inside, and firefighters sometimes emerge from intensely burning structures with patches of first degree burns from any spot not fully covered by their bunker gear and Nomex hoods.

Absolutely none of this occurred to Phil, but he quickly found out. The two men made several forays into the house, being driven back each time by smoke, flames, and intolerable heat. Inside the house, six members of a family were trapped.

* * *

The first time I ever googled my name, I discovered another Phil Brideaux, whom I’d never heard of. I was named after my great grandfather, Philip John Brideaux (1866-1946), and yet here was another Philip John Brideaux from Sault Ste. Marie, and somehow associated with the Sault Steelers — a team in the Northern Football Conference league of Ontario.

Phil’s wife, Marilyn, was equally curious about me. She had two important questions on her mind when she messaged me: who the heck was I? And what was I doing with her husband’s name? And so it happened that I traveled to Sault Ste. Marie to meet Marilyn on a rainy, October weekend not long after the leaves had turned.

* * *

The area in and around Sault Ste. Marie reminds me of Bragg Creek, Alberta (near where I grew up), except for being punctuated by the searching fingers of the western end of Lake Superior. This region is part of the traditional lands of the Ojibwe people: the low, rolling, boreal foothills of the Canadian Shield curving around the taupe beaches and grey-blue lakescapes of Batchawana Bay. The city itself looks south over the St. Marys River towards Michigan, and west over Whitefish Bay — southeast of where the Great Lakes freighter SS Edmund Fitzgerald broke in two and sank in a fierce winter storm in 1975.

At Sault Ste. Marie, you have the choice of taking the Trans Canada Highway east toward Sudbury, or north and then west to follow the long, curving shore of the lake to Thunder Bay. South will take you across the International Bridge to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and down Interstate 75 toward Saginaw and Flint, and eventually Detroit, far to the south.

These are the environs in which Edwin Charles Brideaux settled, after a winding journey that took him from Jersey, Channel Islands, to New England and then Québec. He was the second Brideaux to venture to Canada, having been preceded by my great grandfather Philip John (1866-1946), who worked briefly on the Gaspé Peninsula in the late 1880s, shortly before his subsequent adventures as an army cook in South Africa.

Edwin and his wife Phyllis Marie Chestle had six children, of which Philip John was the youngest. It might have been the case that Edwin and Phyllis decided to name Philip after Edwin’s uncle, Philip John Brideaux, of Hartford County, Connecticut (son of Elias Jean Brideaux the Elder, 1806-1877, of Jersey, Channel Islands). That’s because Edwin’s first trip to North America had been with his brother Walter to New England, where they worked on Philip John’s dairy farm.

Marilyn Baker met Phil in Sault Ste. Marie when he worked as a rail car checker for the Algoma Central Railway. “That meant that he went through a pair of running shoes every three months because he walked up and down the yard, checking the numbers of the cars and putting stickers on them that said ‘this car’s going on that train,’ and ‘this one’s going on that train.’ He did that for a number of years. Then he got a job with what then was called Dominion Bridge. And I don’t understand exactly what it was that he did there, but it’s now a subsidiary of Essar Steel Algoma,” Marilyn explains.

Marilyn and Phil married in June, 1968. It was clear to her that Phil took after his father Edwin’s temperament as a self-reliant man who preferred to forge his own path. “He didn’t like being told what to do,” she says. “He wanted to be his own boss. So he decided to quit working for other people and try ventures of his own. Some were successful, some were not!” She laughs.

One of those ventures was to become a distributor for Loto-Canada, a 1970s national lottery. Together they sold lottery tickets from Sault Ste. Marie to Tobermory, on the Bruce Peninsula. Phil also began working with the Soo Greyhounds, a team in the Ontario Hockey League, and then became heavily involved with the Sault Steelers football team. “He became President of the Executive,” says Marilyn. He was not only president, but sold team advertising, managed ticket sales and collection, manned the public address system at games, and managed the team’s travel for road games.

“And he drove their team bus,” she adds. “I think if they’d asked him to play he would have tried that too. He used to bring the bus home and park it in our driveway, when they’d come back from a road trip, and the kids would get paid a little to help clean the bus. And then all the shirts came into my basement, and I washed them and sewed them all back together. It was a family venture.”

By this time, Phil had become a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Junior Chamber of Commerce. With the lottery winding up, he moved on to a new venture: photography.

“He loved just wandering in the bush and taking pictures. He’d lie down on his stomach and take pictures of some little red berry attached to some leaf, or climb through brambles and everything, to get just the right picture of this little waterfall,” says Marilyn. “Sometimes it would take him a long time to either get to his destination or get home because he’d do all these little side-treks whenever he’d see something off the side of the highway.”

His business model was to offer his services as a school photographer, while also running a photo processing lab to handle the picture orders. True to his workaholic self, Phil began crisscrossing Northern Ontario, serving clients at primary and secondary schools, logging thousands of highway miles. However the competition was fierce, and growing all the time. By 1981, the business was failing, and Phil and Marilyn were forced to declare bankruptcy.

“We lost our house, we lost our vehicles, we lost everything. So we had to rent a house, which we did through 1982, when the bankruptcy was discharged. Phil went to work for one of his competitors as a school photographer to help pay the rent.”

But of course, Phil was already working on other ideas. The first was becoming a photographer-sales rep for a Toronto-based company which produced yearbooks for church congregations. When he wasn’t photographing for his school photography employer, he was on the road selling yearbook packages and photo services to churches around Northern Ontario.

And somewhere between folding his business and starting the new employment, he’d accidentally become a band manager for two acts in the entertainment business.

“Phil’s best friend’s wife had a friend who was a singer. And this singer was upset with her manager. Somehow or another Phil got pulled in, and became her new manager. And then she had another fellow that she knew who was on the music circuit as well. His name was Eric Shane, and he had a group called Eric Shane and the Shane Gang [everyone in the room laughs]. And he was looking for a manager too, so everything came together.”

With his two photo jobs and two management gigs, as well as his role with the Sault Steelers, Phil was very busy, and constantly on the road. “He was traveling all the time, and he’d have to go back and forth between communities in Northern Ontario and home here, so many times, that he was burning the candle at both ends,” says Marilyn.

* * *

Burning the candle at both ends was what Phil was doing the early morning of November 18, 1982 when he spotted the house fire.

In 1999, I photographed a group of firefighters as they kicked their way into a burning tenement building on Sherbourne Street in Toronto. Fully suited and carrying a charged handline, they fought their way upstairs to the source of the fire in a bedroom, and knocked it down. It wasn’t until they had ventilated the smoke out a broken window (by setting the hose spray to mist), that they discovered the body on the bed. Finding and rescuing people trapped inside a burning structure is difficult enough as it is for professional firefighters.

That’s why it’s a remarkable feat that Phil and the other man managed to get far enough inside the burning house to rescue one of the family members: a six-year old boy.

The other five members of the family, trapped in the flames, could not be reached, and did not survive.

* * *

Phil’s participation with the Junior Chamber of Commerce and the Steelers reflected his dedication to the life of the community and its youth. His many business ventures reflected his dedication to supporting his family as a self-reliant entrepreneur who never wanted to depend on anyone else. Yet it’s hard to estimate the impact on the psyche of an extroverted man faced with what Phil faced in the early hours of that November day. He could not help but carry with him the memories of what he saw and heard in the fire, even as he forged ahead with his busy routine through the Christmas season of 1982. He was already tired out enough from his many responsibilities, as well as managing the bankruptcy. Now he would have this traumatic experience to process as well.

A little over two months after the fire, on the late afternoon of January 31, 1983, Phil was taking both school pictures and church pictures in Sudbury, and had to come back to Sault Ste. Marie to ensure that his singer’s gig at the Holiday Inn was finalized. He told Marilyn to expect him between 7:30 and 8:00 PM. It was a bright, sunny and mild winter afternoon as Phil drove west from Sudbury.

Somewhere around Espanola, he rolled down his driver side window to keep his weary eyes from drooping.

* * *

“I was over at a house five blocks from where we lived, doing my ceramic class, when they knocked on the front door,” says Marilyn quietly. “They tracked me down to that house. I was in the basement in my class, and the owner of the house said, ‘Marilyn there’s a couple of police officers at the door that want to talk to you.’ And as soon as I was walking up the basement stairs, towards the door, I knew what it was, because I saw Phil’s best friend, Bob, standing with the officers. And the first thing that went through my head was, I want my mommy!”

There’s a silence in the room. There are 33 years of grief and sadness bound up in the silence. Marilyn’s eyes are brimming over.

“At first, the police thought that Phil had come around the bend, and out from the shadow of a rock cut, into the afternoon sun. They thought perhaps he got disoriented. But when they did their reconstruction, the marks on the road and the location of the pieces of the two vehicles didn’t match that theory.”

The eastbound driver survived the collision, but with grave injuries.

* * *

Despite a February blizzard, people who knew Phil came from all over the region to his visitation. They stood in line, out in the cold, for an hour, to pay their respects. The turnout at his funeral the next day was equally large.

“The funeral procession from the church to the cemetery was so long that we had to have police cars at the front and police cars at the back,’ says Marilyn. “But that’s what happens I guess when you’re only 38 years old. And you still have a vast circle.”

* * *

Later that Spring, Marilyn accepted the Commissioner’s Citation for Bravery from the Ontario Provincial Police on behalf of Phil for his heroic actions in the Garden River house fire. Thirteen years later, Phil was inducted posthumously into the Northern Football Conference Hall of Fame for his many roles with the Sault Steelers. As a friend wrote in the Sault Star shortly after his death, “There is no question that he was the team’s most valuable member.”

Marilyn keeps a space for him in her home in Sault Ste. Marie, where she lives quietly next door to her children. Out of her abundant generosity, she lets me sleep in this room for my visit. I sit quietly and cautiously in the middle of the space, gazing at the photos, the awards and the mementos of the man with whom I share a name. Phil Brideaux is my third cousin, twice removed. And I’m certain his vibrant spirit still whistles in the wind through the boreal forests of Northern Ontario, and across the waters of Lake Superior and Georgian Bay.

#marilyn brideaux#phil brideaux#philip brideaux#philip john brideaux#sault ste marie#sault steelers#soo greyhounds#edwin brideaux#edwin charles brideaux#phyllis marie chestle#phyllis chestle#jersey channel islands#jerseyci#heritage jersey#heritagejersey

0 notes

Photo

Charles Edwin: The Brideauxs in Ontario Part 1

The startling photo dominates the front page of the Ottawa Citizen for August 3, 1982. On Somerset Street West, an Ottawa Fire Department ladder truck sits amid the rubble of the tailor shop into which it has crashed. Debris covers its roof. To the fire truck’s left sits the remains of the van it first collided with in the intersection, causing the van to crash into a pole.

Below this photo is another photo, showing rescue workers extricating the driver of the smashed van. The driver is 52-year old Charles Edwin Brideaux.

Thirty-four years later, I’m sitting with him in Sault Ste. Marie, in Northern Ontario, near the eastern edge of Lake Superior.

“When I hit the pole, my son’s friend went out the side door and landed at the back end of the fire truck wheels. Another foot and she’d have been under them. She had five broken vertebrae,” says Charles. “Barry ended up with a dislocated, broken shoulder. And I stayed for 13 days in the hospital.”

* * *

Charles Edwin Brideaux is the eldest son of Edwin Charles Brideaux, who in turn was one of the youngest sons of Elias Jean Brideaux the younger.

In 1905, Edwin left Jersey for the second time and crossed the North Atlantic for Paspébiac, on the southern coast of the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec. Elias Jean had more or less compelled Edwin take an indenture on a local farm run by an acquaintance.

Edwin was not happy about it. He had previously emigrated with his older brother, Walter Brideaux, to the United States, where the two brothers went to work on the dairy farm of their uncle, Philip John Brideaux (1852-1910). This particular Philip John (one of many in the Brideaux tree) emigrated from Jersey some years before and settled with his wife May in Hartford County, Connecticut. There, Philip established the first herd of Jersey cattle in the United States.

Edwin did not enjoy Connecticut. Walter stayed, but Edwin returned to the Channel Islands, hoping to work on the family farm, and perhaps even one day inherit it.

His father was not pleased to see him back.

Elias Jean had made it a point to send his sons away one by one as they came of age, and insisted that they make their own fortune somewhere in the world. As Edwin apparently had not yet done so, he was not welcome back at L’Amiral.

“My dad wanted to stay,” says Charles. “And Elias Jean said ‘No, you’re going to go back. You’re going to go work for this farmer for three years for food, clothing and tobacco. And when you’re done there, you can do what you want.’”

So back Edwin went. He never again returned to Jersey, and Elias Jean died the same year Edwin’s indenture ended. True to Elias Jean’s wishes, his property passed to his eldest son Alfred John, and later to Alfred’s second son Lewis Elias.

Edwin spoke little of Jersey. “All he ever talked about of Jersey was the shore,” says Charles. “He never talked about the rolling hills, or the mountain, or Elizabeth Castle, or nothing. All he talked about was going down to the shore for the seaweed.”

Vraic: the Jèrriais word for the seaweed harvested by farmers from Jersey’s beaches, and spread as fertilizer over the island’s potato fields. During permitted times twice yearly, farmers gathered on the beaches from dawn until dusk and hauled up seaweed by horse cart, by hand, and in modern times by tractor. As a young boy, Edwin would have helped his family load up the carts with the vraic that washed up in abundance on the shores of St. Ouen’s Bay, and haul it back to the farm for spreading.

* * *

When his three year indenture on the Paspébiac farm was finished, Edwin ventured further inland up the St. Lawrence River to Montréal, Québec, where he landed a job repairing industrial scales. Algoma Steel in Ontario bought one, and Edwin was sent to Sault Ste. Marie to help install it and repair it. When he completed his assignment, Algoma Steel asked him to stay. Edwin decided to accept their offer and settled in the Sault — nearly 2000 kilometres west from where he’d originally started. He didn’t escape the snow, but he did meet and marry Phyllis Marie Chestle.

Together they had six children and Edwin settled down into family life. Sue was the eldest. Charles Edwin was the second eldest. Philip John was the youngest. When Charles was a toddler, Phyllis would load a roast beef in the undercarriage of his baby buggy and the family would take the International Transit Company ferry across the river to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, to visit her sister on Sundays.

In addition to becoming a father, Edwin became a gardener, and a Scout master. In Sault Ste. Marie, basic bushcraft was not a difficult skill set to come by, and Edwin formed a scout troop and established Camp Brideaux by the time Charles was two years old. “The boys used to come, and we’d want to go with them,” says Charles. “Dad would say ‘No, you can’t, you’re not old enough.’ We couldn’t wait be eight years old, every one of us wanted to get into that. Because those boys had so much fun with my father.” Today, Camp Brideaux no longer exists, but the road leading into the property is still visible from Baseline Road between Town Line and Airport roads on the western edge of Sault Ste Marie.

* * *

When Charles came of age in the late 1940s, he went to work for Canada Steamship Lines as a stevedore. There he helped load and unload the CSL freighters that plied the Great Lakes from Fort William (later to become Thunder Bay), at the head of Lake Superior, to Montreal on the St. Lawrence River.

“I was the guy who got 45 cents per hour for his work. Not until 1947 did they give us all a dollar an hour or so, for eight hours a day, for an eight-hour pay. But you never worked eight hours,” says Charles. “You’d work half an hour, and then you’d sit down for an hour. You sat around the room like this, 30 men. If a boat came in, you had eight hour’s work. But if a boat didn’t come in, you didn’t have that work.”

* * *

The Great Lakes are a spectacular feature of northeastern North America, amounting to a chain of giant, freshwater inland seas containing almost all the traits of the open ocean. Together with the St. Lawrence River, which drains the Great Lakes into the North Atlantic, shipping access reaches inland to the U.S. Midwest, connecting to westbound rail routes. A myriad of small rivers drain into the Great Lakes Basin, giving smaller boats access further inland to other communities west towards Manitoba and the U.S. Midwest, south to the American inland waterways, and north to James Bay and Hudson Bay. American author Holling Clancy Holling celebrated this in his 1941 children’s book, Paddle-to-the-Sea, which was made into a film in the late 1960s by the National Film Board of Canada.

During the Second World War, the Great Lakes were a giant whaleback of heavily-travelled shipping routes, anchoring the thriving, wartime manufacturing heartland of Canada and the United States. Iron taconite ore moved downbound from the side-by-side ports of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin, to rust belt cities along Lake Huron and Lake Erie. Coal from West Virginia and Pennsylvania moved upbound from ports like Buffalo, New York, and Toledo, Ohio, to Lake Michigan ports like Chicago, then on back to Duluth. Grain from Western Canada and the U.S. Great Plains shipped from Fort William, Ontario and Duluth to all points along the Great Lakes, and onward overseas.

Two major “gates” on the Great Lakes Waterway regulate the shipping lanes. One is the Welland Canal, bisecting the Niagara Peninsula to connect Lake Erie with Lake Ontario between Port Colborne and St. Catharines, Ontario. The Welland Canal allows boats to bypass Niagara Falls in a spectacular feat of engineering, consisting of a dramatic run of locks — a kind of giant water escalator.

The other is the Soo Locks, situated on the St. Marys River between Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The Soo Locks allow boats to bypass the St. Mary River rapids and travel between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Both points close in the winter season and reopen after the Spring thaw.

* * *

As a stevedore, Charles helped load and unload Canada Steamship Line lakers docking at Sault Ste. Marie. “We would unload the Winnipeg, the Fort William, the Fort Henry, the Fort York, the Fort Chambly…” says Charles. “The Fort Henry when they built it, it was the fastest ship going at that time. It could make Thunder Bay in eight hours. Then it would unload, load up, and come back in eight hours. Whereas the other boats took 12, 16 hours to get there. It was the same from Sarnia. The Fort Henry made it in eight. These boats would run from Montreal to Thunder Bay, with stops on the way like Thorold, Oakville, Sarnia and Sault Ste. Marie. They’d load canned goods and flour at places like Leamington. Then they’d unload at Thunder Bay, and it would go west by train. Then they’d load up again at Thunder Bay and go back down to Montreal.”

The most frequent commodity Charles helped load was the Algoma steel produced in Sault Ste. Marie. “We would load Algoma steel on the deck. Five feet high,” he recounts. “The ship would take it off as it went downbound. We had a one thousand-square foot warehouse, and it would be full by the time Winter came. Flour. All the stuff from Algoma steel. It would be full. And then we’d would dish it out every week. Every day, dish something out to somebody. When the 23rd of December came — when everybody else got laid off — there were four kept on. Myself, the foreman, the girl in the office, and the agent. Say a guy would come in, wants 30 bags of flour. He’d just pick up a pallet, set it on his truck and away he’d go. Someone comes in, wants 30 bags of sugar, it’d be the same thing.”

And sometimes accidents happened.

“Yeah, the Fort William accidentally dumped the steel over in Montreal once. We had loaded steel on the top deck, and at Montreal, the mate came in and he said, ‘I can’t open the doors ‘til they take the steel off the top,’ and, the other guy says, ‘Open the doors,’ and the mate says, ‘No can’t do it.’ The other guys says, ‘Yeah, you gotta open the door.’ Well. They opened the door and the bolt just went right over. Water pouring in. They just went like that. Tipped over sideways. And what a mess to clean up. Imagine, they had all that steel on there — let alone they had all the canned goods, the flour, everything inside the boat, yeah.”

Charles is referring to regulating the ship’s ballast when unloading cargo. The accident to which he refers happened on September 14, 1965, around 4:30 AM. The September 15, 1965 Montreal Gazette reported that shortly after the ship began unloading, a large explosion “turned the ship into a cauldron of flames,” after which the laker rolled to one side and partially sunk. Five sailors perished in the inferno. George Wharton, writing on the Great Lakes and Seaway Shipping website boatnerd.com, explains that the capsizing occurred first, as the “cargo was being moved to the upper deck at the same time as ballast was being pumped, making the vessel unstable.” The explosion that followed was a load of powdered calcium chloride on the ship mixing with the water as it capsized. This released a large quantity of highly volatile gas which caused the giant explosion and fire.

“We were lucky at Sault Ste. Marie. We were ‘high,’ so we didn’t have that problem. Our ramp to get in the boat was steep, going up. Same coming down. You know, our machines would just make it in to get over that hump,” says Charles.

The present shipping industry on the Great Lakes bears little resemblance to the boom years of the Second World War and Cold War. “It’s done. It’s done,” he says. “There’s no more package freighters. It’s mostly by truck. See, a man from Detroit wants a plate of steel. He drives up, picks it up, takes it back to his shop. A man that wants 30 bags of sugar, he has a truck come, he’ll be going to Loblaws or NoFrills [Ontario grocery store chains] with 30 bags, or put it into a warehouse, and the warehouse here will distribute it. Rail is good but it’s slow, and they don’t carry package freight. Rail carries logs, coal, paper, rolls of steel, that sort of thing. When you look at the businesses that are gone from Sault Ste Marie alone, that aren’t here anymore, it’s shocking. Our paper mill is gone.”

Charles retired from Canada Steamship Lines in the early 1970s. “I went 28 years there. And they handed me a pension of 1000 dollars. That was your pension. Not a month. That was your pension. ‘There’s your pension. Do what you want with it.’ So I bought a swimming pool. And it was one of the best thousand dollars I ever spent. I didn’t have to run to the beach with the kids anymore, or nothing, they just hop in their trunks and they’d be in the pool and out. And they’d get in again in a few minutes.”

* * *

Retirement allowed Charles to visit Jersey twice, to see the island from which his father had left behind. “I always wanted to go, and I never could afford it,” he says. “And then my mother said, before she passed away, that I was to take whatever money she left me and go to Jersey. I was married with three kids, but I did exactly that, because that was part of her wish to let me see what Jersey was.”

In Jersey, Charles finally met his cousin Joyce Brideaux and her husband Brian Gilbert, along with their family. “Oh I thought Jersey was wonderful. It was a beautiful time, they showed us the whole country, I saw everything you could have seen, that you’d want to see. Elizabeth Castle and all that.

“I liked the idea of their stores. If you went to the butcher shop, all you got was the butcher. If you went to the fruit store, all you got was fruit. If you went to the potato store, that’s what you got. Potato and onions. And then the only eight miles of four-lane highway, that really struck me.

“But see, first time I went, I was used to traveling on our [Canadian] roads. Well, I told Brian I didn’t want a car. Brian says ‘We’re getting you a car whether you want it or not, we’re not going run you around.’ I didn’t have any trouble with driving on the left. But I had trouble with meeting another car. I didn’t know what to do. There was no place to go, the roads were so narrow. And then finally this one driver stopped, and he said ‘Did you see that little space you’ve passed?’ and I said ‘Yup.’ And he said, ‘When you saw me, you should’ve pulled in there.’ So I backed up and pulled into it.

“The second time I went over, Joyce’s daughter Karen, and her husband David, tried to get me to stay, but I said no. In fact, Uncle Bert [Joyce Brideaux’s father Philip Herbert Brideaux] had asked my older sister Sue, and her husband Charlie, to come and work there, too. And my dad said to Charlie, ‘Look, you can go, but you’re not a Jerseyman. You’ll never get nowhere. You’re not a Jerseyman.’ And Dad drilled that into Charlie.

* * *

Charles and his son Barry, along with Barry’s friends, had driven up to Ottawa in his van for a roller skating competition the first weekend in August, 1982. At about 7:45 PM, as they were driving south on Lyon Street in an intense rainstorm, an Ottawa Fire Department ladder truck, heading east on Somerset Street to a call, t-boned Charles’ van at the intersection. The force of the impact drove the van into a light pole, and the fire truck into a tailor shop doorway, where two men were taking shelter from the rain. All of the firefighters were injured to various degrees, including two who were thrown off the back of the fire truck.

The men taking shelter in the shop doorway were both killed by the fire truck’s impact.

Charles and the fire truck’s driver were both trapped in their vehicles. “They couldn’t get me out. So they took the seat out to get me out,” says Charles. “And it turns out that the driver of the fire truck had a glass eye.”

“He had a glass eye,” I repeat for clarity.

“Yup,” nods Charles. “He had a glass eye. And how did he have a fire truck licence? His buddy took the driving test for him. So that was one of the things that came up in the court case.” That, and Charles had a green light when he entered the intersection.

The court case was to sort out the insurance claims. Charles and Barry, along with Barry’s friends from the van, all had lawyers. Charles returned to Ottawa some months later for the hearing. He and the others were eventually to receive a settlement, but whether, and how much, had to be worked out in court.

At the Ottawa courthouse, Charles sat in the hallway, outside the designated courtroom, waiting for his case to come to the top of the list. When it did, the Clerk of the Court stepped out into the hall to summon him. The Clerk was shorter in stature, in his late 70s, with a receding hairline and glasses. He stood in front of Charles. When he spoke, he spoke with a Jèrriais accent.

“I’m Mr. Brideaux,” my grandfather Wilfred Philip said to Charles Edwin. “And I’m looking for this young Mr. Brideaux.” Charles got up and unexpectedly found himself shaking hands with the man who turned out to be his third cousin, and the two walked into the courtroom together.

#jersey#jersey channel islands#jerseyci#heritage jersey#heritagejersey#jersey heritage#Jèrriais#vraic#gaspe peninsula#gaspe#paspébiac#paspebiac#saultstemarie#sault ste. marie#great lakes#greatlakes#brideaux#canada steamship lines

0 notes