Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Cultural workers are unionising!

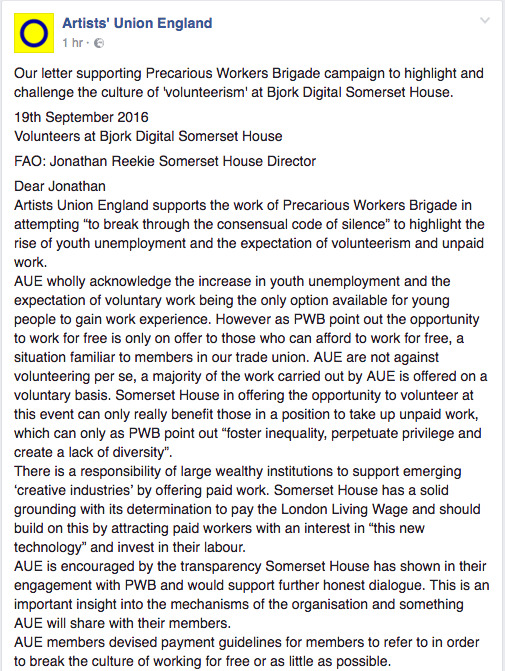

Very excited to see the recent unionisation by designers/cultural workers, archictectural workers and game workers - and, that they are organising in solidarity with all workers in the sectors and amazing unions. Check out and join them!

UVW-Design & Culture Workers (UVW-DCW): Calling all designers, architects, gallery workers, curators, interns and art educators. https://www.uvwunion.org.uk/design-culture-workers

UVW-Section of Architectural Workers (UVW-SAW): the first ever trade union to organise everyone in the architectural sector, including assistants, cleaners, students, admin staff, technicians, sole traders, and architects. https://www.uvwunion.org.uk/saw

Game Workers Unite UK branch of the IWGB: a worker-led, democratic trade union that represents and advocates for UK game workers' rights. https://www.gwu-uk.org/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A solidarity letter for Macao from Precarious Workers Brigade

We are a collective of activists who have been campaigning for over ten years against the growing deployment and normalization of free labour within the cultural sector. We wish to share this open letter in solidarity with Macao, to emphasize its importance in the international context. To explain why we, who live ‘abroad’, need Macao.

Macao is one of the most lively and important experiments in creating cultural institutions that are daring and sustainable at the same time. Its significance for contemporary cultural production extends beyond Italy and it is studies and followed with great interest by a number of practitioner’s networks and local governments. This is not just our evaluation of the many cultural projects and experimentation with different kinds of production hosted there. For us, who live in the ruins of Cool Britannia, the slogan used by the Tony Blair government to introduce the policy of its lefty-neoliberal ‘Creative Industries’, Macao offers a different vision for a future economy, one based on cooperation rather than competition. What is more, Macao is a much needed example of another model for organizing culture that is inclusive and democratic without becoming populist, without relying on a mix of self-exploitative free labour, mandatory internships and voluntarism.

There are very few other cultural organizations in the international landscape that have been experimenting with models of internal governance that directly remunerate reproductive labour, striving to equally redistribute care and maintenance functions among those involved. Not many other organizations consciously dedicate part of their energies, time and resources to actively support other campaigns and political processes beyond their immediate interests. Very few creative hubs keep an open structure of governance, based on assemblies and working groups, that is able to both remain open to new proposals and welcome new actors, while at the same time invent effective methods for running such a diverse number of projects and activities. Almost no other is experimenting with a basic income and alternative currencies engaging such a great number of participants.

We believe that it is responsibility of the Municipality of Milan to do all that is in its power to support and regularize the important ecology of practices that found a shelter in Macao. This starts from having the courage to interrupt the course of action that was recently set in motion with the sale of the Viale Molise buildings to a banking group such as BNP Paribas. The space of Macao can and should be kept into public hands as a great asset. It could - and should - become a pioneering example of a cultural institution governed as a common.

http://www.macaomilano.org/spip.php?article768

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antiuniversity 2018: Roleplay a Coop! 10 June 2018, 11am - 6pm

Fed up with your precarious working conditions as a cultural worker? Come and join us for a day of collective learning and fun discovering how to set up a co-op and roleplaying one. In the morning, we will be reading and discussing materials on how to set up co-ops; in the afternoon, we will split in groups to roleplay setting up and running a co-op. This will include a game of Co-opoly, the cooperative version of Monopoly. We will finish with a plenary session where we will share the different sets of rules established in each group, the issues encountered during our roleplay and the solutions that we found. Important: If you have had experience with radical co-ops in the 1970s and/or 1980s we really want to hear from you! BOOK YOUR PLACE HERE: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/antiuniversity-2018-roleplay-a-coop-workshop-tickets-46049545430

Date/Time: Sun, June 10, 2018, 11:00 AM – 6:00 PM

Location: 416 Redwood Housing Co-op Oxo Tower Wharf London SE1 9GY Organised by Precarious Workers Brigade + Friends, a group of cultural workers that met at the encounter "Culture + Work at Point Zero", organised by Precarious Workers Brigade in April 2018. Tired of our precarious working conditions, we are interested in learning about co-ops and exploring their possibilities as a way to a better and happier professional life. * This event is part of the Antiuniversity Now festival, 9-15 June 2018. See the full programme on www.antiuniversity.org By signing up to this event you will be added to the Antiuniversity mailing list. To opt out please email [email protected]

0 notes

Text

On ethics, solidarity, working together: a collective conversation

Based on a collective Skype conversation between Janna Graham and Precarious Workers Brigade, 11 June 2016. Published in ‘Una Ciudad Muchas Mundos’. Madrid: Intermediae (forthcoming)

Janna Graham (JG): Dear Precarious Workers Brigade, I was recently in Madrid with Manuela, at a session where groups came together to work on this code of ethical practices – to guide their embedded work as artists in local communities, working on issues like gentrification, bodies and mobilities and child care.The scene as I walked in was very familiar and would be to all of you: groups were sprawled across the floor with large pieces of paper and coloured marker pens, intently working through the various dimensions of what ethics could mean. From the outside it appeared like the moment when we came all together in 2010, a moment in which we were preparing ourselves for the joys and struggles of the fight against austerity, knowing little of what was ahead, how much we were to come together and learn and how much we would lose. But of course this moment in Spain is very different from that one we experienced. The intelligence gained from the mobilisations in the squares is palpable. Questions about how to cope with the institutionalisation and the ‘becoming hegemonic’ of social movements gaining political currency (can you imagine us facing this question now in the UK?), with how to maintain the accountabilities but also the intimacies and personal proximities of direct democracy while engaging with the governmental bureaucracies, how to make movements stronger and not weaker by the various moments in which movement activists are defeated by the apparatus they have only recently come to inhabit. With this in mind, we can maybe read this ethics document and reflect on our own experiences of questioning the ethics of our work.... One of the first points we might want to discuss is that we have never described what we do as Precarious Workers Brigade as embedded practice, (in the UK they usually call this kind of work ‘socially engaged’, which tells you something about how normalised conditions of non-embeddedness are in the art world here i.e. is art not always socially engaged? is it not always embedded, just usually to indulge ruling elites?). Despite this, in other aspects of our lives and work in the arts, many of us do intensive work in and within particular contexts. Do you think the two practices are related?

Lola: It’s funny this question, as it’s true many of us make our precarious livings doing ‘embedded’ art or research projects. The rehearsing of questions of ethics within the PWB group was very important to many of us in this. Not because it gave us strategies for working with those groups necessarily, but because it de-centred us as individual or solo practitioners and allowed us to think of ourselves as part of larger collectivities.

Carrie: Yeah, it took the emphasis off the genius, the artwork, all the things that an art world that cares very little about ethics places at the centre. Instead, we built our power, our own collectivities, our accountability to another mode of valorisation in which ethics was a central component.

Martha: It’s true, as a group, though we made things and ideas all the time, we never called ourselves artists. This meant and means that when we do enter into this other art world (the one that does not place ethics at the centre) - whether as individuals or as different versions of the collectivities formed in PWB - we felt more powerful to negotiate and to demand different terms and conditions for ourselves but also for and with our collaborators from outside of the art world. Our meetings, places for sharing experiences of oppression in and through cultural organisations and finding ways to work against them, produced a different kind of configuration of the artist/social/community, one that was based in radical social aims and in practices of solidarity.

JG: I remember the importance for the group of thinking through of the term and practice of solidarity, that we neither wanted to work solely on our own conditions nor do ‘outreach’ with those outside of the arts. From this ethical framework that you describe, solidarity was less a way to encounter ‘others’, ‘communities’ or 'the social’ and more a way to link our struggles within the arts to struggles in what were perceived to be in ‘other’ fields, like those of cleaners, who in fact do work in the art world, so the very in / out dichotomy is often a fallacy. Our discussions were about challenging the parameters of how this art world is defined and also who is perceived to be entitled to cultural practices. I remember this very specifically in an encounter with Latin American Workers Association at the beginning of our years of collaborations, when they asked what we ‘artists’ could bring to their movement and then quickly questioned themselves, suggesting they too were were artists in their social movement work. How do we think of the making of the ethics code in terms of solidarity?

Maggie: A group of us have been reading a text on solidarity (2), as it’s become a very trendy term. It's very interesting to watch people perform the theorisation of solidarity who clearly do not write from the position of this kind of expanded and transversal practice. They reproduce themselves as theorists, or as cultural workers playing with a new term.

Lola: For PWB solidarity is always a practice. It is very local and about reproducing social movements, people who learn and fight together. Practicing solidarity is not about reproducing privilege but a move toward communing and sharing.

Irene: And it has operated on a number of levels. It is intersectional and transversal solidarity with people who are not like ourselves.

Kara: I love this quote from collective Aboriginal activists groups in the 70s: “If you’ve come here to help me, you’re wasting your time. But if you’ve come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” (3)

Lola: But solidarity is also about solidarity between our very similar positions of exploitation, caring with and for people and being cared for ourselves. At times is has also been about supporting people as they are becoming politicised (like interns or cultural workers who did not want to admit that what they experienced was exploitation).

Adele: Solidarity started through committed mutual support, by creating spaces of sharing and listening. It was not about imposing artists into communities or particular situations.

Maggie: But as an artist or cultural worker you also have a certain power to be in solidarity, to divert resources to solidarity projects, to negotiate access to resources, visibility and cultural groups that don't have it. I recently negotiated to have a part of the budget liberated from claims and outcomes so that I could re-distribute it within a collective ‘commoning' process. We can use that privilege to take resources out to be shifted to people. How do we use our privilege, how do we use these institution that don’t deserve to have this work?

Martha: I think solidarity has to involve a kind of sabotage.

JG: It’s true. One of the things that we discussed in the events around the ethics code in Madrid, is how to engage in this work without it becoming individualised once again, without it being about the solo rogue or heroic practitioner who interiorises and both profits and pains from being the one inside the institution, the one who has the capacity to re-distribute. Even if negotiating individually as an artist for me PWB and other social movement collaborators have helped us to keep this interiorising tendency in check, to remain accountable to a community, and not to slide into modes of individualised subjectivation that, when beard alone, seem to result in either institutional heroics or ‘personal’ illness and depression. This seems really important to work out.

Carrie: Yes, there is an important difference between the ‘solidarity’ of the upper classes and those in struggle. Upper class solidarity - through which people establish strong alliances between themselves in order to maintain their position (the position of the ruling class) is not about recognising the other's conditions in order to care for them but in order to reproduce the privilege of the ruling class (even when that is the radical left). Regardless of their sometimes good intentions and radical rhetoric, many groups continue to manage the common resources using a top down approach. In the case of Common Practice, the group who wrote the text about Practicing Solidarity (2), ‘solidarity’ may not come from the upper classes per se, but still refers to a functional alliance between small art spaces. This is functional to maintain and secure public funding from the Arts Council of England against the giant cultural institutions. Little reference is made to how we might generate new forms of sustainability which are more inclusive, e.g. working with different kinds of art spaces which are not representing the art world or have never received Arts Council support or working with groups ‘outside’ of the arts who include creative practices within their social movement work. Solidarity implies some kind of symmetry, reciprocity, a commitment to the distribution of resources at all levels... not a top town approach in the name of professionalism, excellence, nor personal heroism.

JG: Shall we speak for a moment about the ethics code itself? (4) What do you think was its role in PWB? Why and how was it produced?

Martha: Well in some ways the forming of Precarious Workers Brigade itself mapped out the initial contours of an ethics code. A smaller group, then operating under the name Carrot Workers Collective, had been invited to do a residency at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA), a pretty well known gallery in London during their ‘Season of Dissent’. The Carrot Workers opened up the question of how to use such residencies to genuinely support political work in the art field to anyone who might like to join a conversation about it. Out of that conversation around the ethics of tokenistic/politically themed residencies we created Precarious Workers Brigade. In this larger collective, after a number of blocked attempts at using the ‘Season of Dissent’ residency at the ICA as a space for cultural workers, arts students and other communities to gather and prepare for the occupations and demonstrations of the anti-austerity movement, we used it instead to stage a people’s tribunal on the precarity (and hypocrisy) of the art field itself. (5)

Adele: In those early days the question of ethics came up a lot. I remember a very heated conversation around whether or not members of the group could claim the collective work as part of their individual practices, particularly when our political work was taking us away from our artistic responsibilities as art students or workers. This was not resolved and has remained a bit of a tension in the group, but even then signaled the need for something that we could refer to in order to navigate the complicated terrain we operate in as activists in the art field and to hold ourselves accountable to one another. Remnants of these discussions appear in the ethics code under the heading ‘authorship’.

Maggie: But the actual ethics code came later in our collective process. After the tribunal, we started to get all sorts of invitations to write texts, give talks, be on panels and do workshops. A lot of this wasn't really helpful, was distracting and extracting energies away from other things we wanted to do. At the same time, many of us were in the habit of perpetually saying yes. So we put in the ethics code some guidelines to ourselves to help us evaluate the usefulness of certain activities. There are sections on ‘When we say yes’ and ‘When We Say No’. We asked, for example, do we want to engage in consciousness-raising, if people are already conscious but inactive? Or what’s the balance and relationship between doing representational work i.e. in art galleries and on the ground/organising work i.e. running clinics for precarious workers, staging protests and actions etc.? We also asked questions about the conditions of production at the site of the invitation and who the work serves. This helped us to make decisions, to free up time, resources and energy. And it was also helpful in resisting the production logic that demands and places much value on the constant production of new things, rather than doing more with the tools and analysis we had already developed. We wanted to strike a balance between developing new tools and knowledge and making more readily available and usable our existing ones.

Kara: The process of writing the code also enabled us to make visible and remind ourselves and others what the collectives' aims were. Writing it helped us articulate why we are here and what kind of work we might need to focus on to achieve this.

Carrie: Like solidarity, ethics are practiced. Using the code also meant constantly re-visiting what we had written down at earlier stages in our processes, which was really useful in helping us re-evaluate the context around us and our relationship with it. Do certain things we are doing still make sense given how things have moved and shifted? Are the questions around ethics the same now as when we asked them in 2010? For example, when we began the group, the conversation around internships was not really out there, but now the Arts Council of England has tied labour standards around internships to public funding grants and other professional organisations have issued clear guidelines around the use of free labour in the arts. This does not mean that the problem is solved but does mean that we do not have to concentrate most of our time on consciousness raising and therefore perhaps need to accept invitations to speak in the art world less unless there is a genuine interest in organisational change.

Kara: It’s maybe important to say that we re-visit these questions of ethics in different ways. The first is situational, like Carrie describes, to help us make decisions about individual invitations but they also shape agendas of our larger meetings, usually on an annual basis. In the big meetings, we attempt to map out what we have done and what we would like to and the code plays a role in remembering our priorities, and setting new ones for the year, who is interested in working on what etc. Recently we have had large meetings reflecting on the last 5 years, not to self-congratulate or to put together a publication about the heydays of the PWB, but to reflect on where we are, what’s going on in people's lives, what are the needs, desires, of people in the group and the context in which we are operating. What does an ethical framework look like in today’s environment? How do we build self-care and acknowledgement of our own conditions into our planning? This is also an important point around ethics of a non-exploitative practice.

JG: It might be useful to say something about the form of the ethics code in relation to the idea of it being determined by its use, especially as our friends in Madrid may be thinking about how to develop their initial mapping into something that it readily available and usable across different platforms.

Adele: We were reflecting on this in relation to the code developed in Madrid, which addresses some very important points but in the translation comes across as perhaps a bit like a list of rules. For us the making of the code was to be neither slippery and non-committal around ethics but also to not be overly dogmatic in its form or its application. We found it very helpful to depart from a series of questions for discussion and collective decision-making. It wasn’t a bureaucratic terms of reference or something, but something direct and accessible to us that offered points for negotiation and discovery of what the ethics of the group were in relation to the invitations we received. Our response to these points and questions were gauged very differently if the invitation came, for example, from another social movement group, versus when they came from an establishment art gallery i.e. if the group was committed to social justice at its core we might not be so concerned about free labour (as we are all free labourers in PWB) but if it came from a gallery we had different responses. The questions of the ethics code and the various responses we received were also diagnostic, they helped us to use the invitations we received to diagram power relations across the field, relations we all know about but were now able to plot across different kinds of organisations.

Lola: It’s probably important to say that we ask ourselves these questions of the ethics code, but also the organisations that we are working with, hoping that they would cause them to reflect on their own working practices. So the checklist of ‘when we say yes and when we say no’ was turned into a set of questions for them. In this way we have not been as direct as, say our comrades in W.A.G.E. in the US, who have very clear guidelines around pay practices to which organisations can sign up and be certified. We have used different tactics depending on the various constituencies we work with i.e. intern campaigns around the ethics of payment have looked quite different from our solidarity work around immigration, cleaners etc. as each dimension and group galvanised around precarity has different conditions and terms around ethics. But we do make it a point to ensure the conditions of production are published alongside the texts and presentations that we make in cultural institutions.

Martha: Posing questions has also been a broader strategy for us, a way for us to gather particular constituencies. We use questions as a way to invite precarious workers into conversations in the first instance i.e. the question ’do you free lance but you don’t feel free?’ helped us to probe whether groups might want to gather around freelancing in the arts? As a group we are committed to processes like militant investigation and popular education, which begin with collective questioning rather than a list of do’s and don’ts. We think it’s important and vital that those most affected by an issue be the primary investigators of those conditions and the ones to pose questions of ethics.

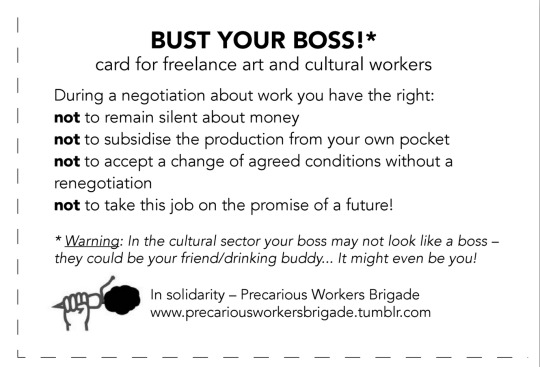

Manuela: It’s maybe important to say that the ethics code sits among other tools and materials for use in organising and collective work in and beyond the arts... the Counter-Guide to Free Labour in the Arts (6), the Bust Your Boss card (7), the Training for Exploitation? alternative curriculum (8), the anti-raids know your rights card (9), a free labour infobox template (10)... many of them have been taken up by people working in different positions in the arts, like students, teachers, interns, workers/employees... and indeed are also addressed to people working at these different levels. The ‘Surviving Internships’ (5) guide for instance talks about the problem of free labour in the arts, offering analysis and proposing solutions for prospective interns, current interns and employees that ‘have’ interns. Ethics here are usefulness in addressing these kinds of structural forms of injustice (internships) from the points of view of the different positions involved, and to propose forms of action and solidarity across the board, not just making it an issue for interns themselves. In the brainstorm for ethics guidelines that we elaborated in that workshop in Madrid, we also thought about three different levels of practice/involvement and the positions they imply - the level of the institution, the level of collective practice, and the level of outside collaborators or ‘outreach’ if you like. Maybe it’s a PWB habitus that made me propose these three levels in order to also try map out problems from different viewpoints, to see how problems play out at different levels. Do you have any thoughts on how this multi-level mapping/proposing has worked with the Surviving Internships guide, and/or how PWB tries to engage thinking and solidarity across different positions/levels in the arts?’

Kara: Yes, we have these different positions and levels involved in the ethics codes and tools because those were also the positions reflected in the group. We would not prescribe ethical positions for people but, as we said before, from the conundrums each of us was facing in our different fields of practice and out of a collective will to fight across divisions that are imposed by the structural inequalities and violences of the field. So the group involved art lecturers and their students, curators and interns at their organisations in the same meetings, for a period someone from the Latin American Workers group we were developing actions with in relation to the immigration raids, all of us working out what ethics meant across these different concerns. This was sometimes unsettling and uncomfortable as we were straddling two systems of work at the same time: one striving for an ethical way to be and another producing us in various forms of opposition with each other. The tensions of this transversality were important to work through in shifting our perspectives from the divisions created by institutional paradigms. Very practically though, having representatives from these various positions was crucial in producing actions as we would work from the various knowledges at different levels of an organisation to stage protests etc. It has also been important in terms of dissemination of tools, messages and actions, as we have not had to promote them outside of our own fields of reference, but rather through our own friendship and working networks. We have not done follow up research on the usage of these tools, but anecdotally we share moments of their use all the time and have grown a larger community of people who in term disseminate them as and when they are useful to people.

JG: On reflection of six years of working together, we began the process of building an organisation that was based in ethics rather than production, individual authorship etc. We spoke a bit about what this meant for us in our ‘other work’ in the art field at the beginning of the conversation, but at this point in history and particularly in the UK it seems important to think about what organisations based on this kind of an ethics code might look like, at the very least as the basis for formulating new demands.

Carrie: Yeah, that’s for sure; organisations based in ethics are far from trendy here! This would be a huge overthrow.

Adele: Well, at the very core is that cultural work be seen within the context of broader socially reproductive work, and the production of commons, not a separate sphere governed by bureaucrats, elites or special ‘creative’ people.

Martha: It would position itself in relation to specific issues, and those involved would be effected by these issues i.e. issues in the neighbourhood where the organisation was situated, or the conditions of it workers. It would use this as the basis for forming solidarity relationships.

Kara: It would make, commission and show work in the framework of this solidarity. It would not become closed, but rather invite others to join if they are willing to make commitments to the work.

Lola: It would understand itself as investigating and learning from its work. It would support its workers with care and viable (even joyful!) living and working situations. It would be non- hierarchical, it would create environments of support, and it would take sides and not be aligned with forces of exploitation. It would be free of all corporations and private interests.

Carrie: Like I said, arts organisations basing themselves on ethical questions would be a huge overthrow!

2 - Carla Cruz for Common Practice. Practicing Solidarity. London: 2016. http:// www.commonpractice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ CommonPractice_PracticingSolidary.pdf

3 - This quote was voiced by Lila Watson at the UN Conference on Women in 1985, but she suggests it emerged out of practices of collective struggles and should therefore not be attributed to her. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lilla_Watson

4 - http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/ethicscode

5 - See Precarious Workers Brigade, ‘Tools for Collective Action: People’s Tribunal’ in Dis magazine. http://dismagazine.com/discussion/21416/tools-for-collective-action-precarity-the- peoples-tribunal/

6 - Carrotworkers’ Collective. Surviving Internships – A Counter Guide to Free Labour in the Arts. 2011 https://carrotworkers.wordpress.com/counter-internship-guide/

7 - http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/Toolbox

8 - an updated version of ‘Training for Exploitation?’ has been published in January 2017 with Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Press and is available at: https://www.joaap.org/press/trainingforexploitation.htm

[The original 2012 draft is available here: https://carrotworkers.wordpress.com/2012/05/02/training-for-exploitation- towards-an-alternative-curriculum/]

9- http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/post/24253388147/migrant-bust-cards-are-here- translated-into-20

10 - http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/Toolbox

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 week until: Culture + Work at Point Zero (14/15 April, Limehouse Townhall, London)

Only 1 week to go to our 2 days of militant self-education, conviviality and strategising: Culture + Work at Point Zero, 14 + 15 April 2018, Limehouse Townhall*, 646 Commercial Rd, London E14 7HA Come join us to collectively take stock, self-educate, make new alliances, and plot what is to be done about the state of cultural labour at this critical moment. Here is the facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/207235243342932/ And: below a more detailed schedule of the two days *Unfortunately the space is not fully accessible. Please get in touch if you have access needs and we’ll do everything we can to enable your participation! ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SATURDAY 14 April: 11am - 11.30am Coffee 11.30am Welcome by PWB + Limehouse Town Hall and intro to the day’s working theme: - Life on Zero Hours - The Impossibility of our Conditions: This will cover things like working conditions, anti-racist (labour) organising, coming automation, post-work solutions, universal and unconditional basic income, universal credit, pensions, the nexus between gentrification and our precariousness... 12noon - 1.30pm Working session part 1 - in this part we will map: What are our observations/ analysis/practices in relation to this topic? What are the issues/concerns/gaps? What question(s) do we want to put on the table? 1.30pm - 2.30pm Lunch - we’re providing snacks, tea and coffee (donations welcome) 2.30pm - 4.30pm Working session part 2 - in this part we will move from mapping and analysis to proposals, plans, potential actions, collective statements, ... 4.30pm - 5pm Break 5pm - 6pm Plenary 6pm Collective dinner (vegetarian) - donations welcome ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SUNDAY 15 April:

11am - 11.30am Coffee 11.30am Welcome and intro to the day’s two working themes: - Cultural Democracy: Examining current and past initiatives that try to develop a blueprint for what truly progressive and comprehensive cultural policy might look like, including issues of governance, budgeting, decision-making, evaluation, collective ownership and administration of cultural spaces, and so on. - Cooperativization and Commoning: Considering and getting each other up to speed with most recent concrete proposals being put forward/experimented with around building different forms of organisation, including co-operativisation, mutual aid/mutual societies, unions, circular economies, crypto-currencies and so on. How do we organise in ways that place care and reproduction at the centre? 12noon - 1.30pm Splitting into working groups Working session part 1 - in this part we will map: What are our observations/ analysis/practices in relation to this topic? What are the issues/concerns/gaps? What question(s) do we want to put on the table? 1.30pm - 2.30pm Lunch - we’re providing snacks, tea and coffee (donations welcome) 2.30 - 4.30pm Working session part 2 - in this part we will move from mapping and analysis to proposals, plans potential actions, collective statements, ... 4.30pm - 5pm Break 5pm - 6pm Plenary

0 notes

Text

CULTURE + WORK AT POINT ZERO: 2 Days of Militant Self-Education, Conviviality and Strategising, 14+15 April 2018

Precarious Workers Brigade (PWB) invites you to a two-day assembly to take stock, self- educate, make new alliances, and plot what is to be done about the state of cultural labour at this critical moment. Almost ten years ago, PWB was formed from the skin of the Carrot Workers Collective to examine and transform the conditions of unpaid and precarious labour for cultural workers. Today we again feel the need to reflect, learn with other collectives and campaigns and decide how and in which form to deploy our energies in the years ahead. Because things have gotten worse. How can we discuss cultural democracy in increasingly post-democratic conditions and rising fascism? In the context of ‘post-work’ and increasing automation, how do we organise and imagine different forms of mutuality, commoning, cooperation and basic income beyond the wage? How can we reclaim the right to cultural activities as common spaces of joy and pleasure against the imposed austerity and accelerated gentrification? We are calling cultural workers, artists, cleaners, activists, educators, students, and all those who have a stake in these questions to join us. In these two days, we will hear from each other, we will share short provocations on core issues to prompt collective discussions, build common agendas and take action. More details coming soon - watch this space!

Facebook Event: https://www.facebook.com/events/207235243342932/

Dates + times: Saturday, 14 April: 11-6pm, followed by dinner Sunday, 15 April: 11-5pm Location: Limehouse Town Hall 646 Commercial Rd, London E14 7HA Nearest tube: DLR Limehouse or Westferry Childcare provided Unfortunately the space is not fully accessible. Please get in touch with us if you have access needs and we’ll do everything we can to enable your participation! Email: [email protected]

Photo: Still from Zero for Conduct (Zéro de conduite), dir. Jean Vigo, 1933.

1 note

·

View note

Text

We support the Women’s Strike 8th March 2018!

Precarious Workers Brigade supports the Women's Strike called for the 8th March 2018 across the UK and we invite all of our allies and friends to join too! The Women Strike is impossible. This is why it is necessary.

Check them out:

https://womenstrike.org.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/womenstrike.uk/

https://www.instagram.com/womenstrike.uk/

https://twitter.com/Women_Strike

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

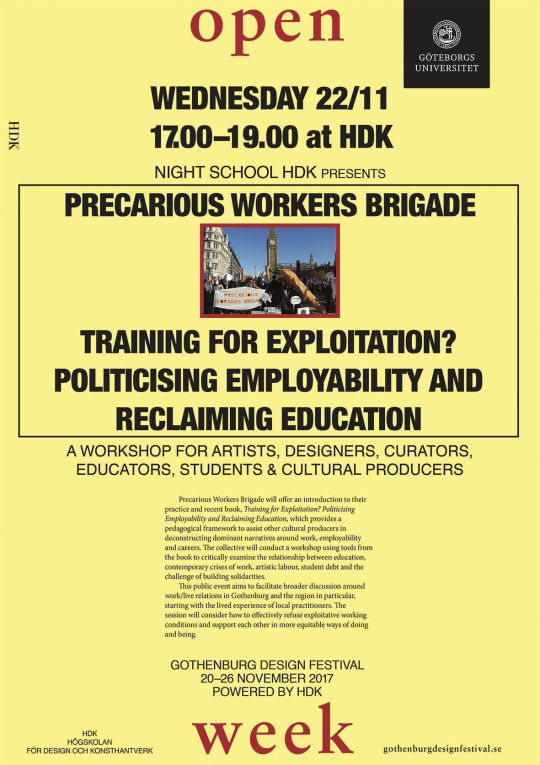

PWB workshop in Gothenburg, 22 November 2017

We are doing a workshop on the ‘Training for Exploitation?’ workbook in Gothenburg (HDK CAFÉ), 22 November 2017, 5–7pm https://www.facebook.com/events/283689615474627/

Free and open to all, come and join!

0 notes

Text

Learning to stand together - Elyssa Livergant interviews Precarious Workers Brigade

Elyssa Livergant and Precarious Workers Brigade, 2017. Learning to stand together - Elyssa Livergant interviews Precarious Workers Brigade. Contemporary Theatre Review Online, Interventions

The following interview with the Precarious Workers Brigade (PWB) reflects on the theme of collaboration in relation to work, the creative industries and Higher Education. As the PWB outline in their book Training for Exploitation? Politicising Employability & Reclaiming Education, a resource for students, teachers and cultural workers, exploitative labour conditions in the arts are often obscured by claims that celebrate autonomous and independent work. As we discuss below, ‘collaboration’ might very well operate as a term that ostensibly redeems various forms of exploitation in the cultural sector and higher education. Describing new forms of post-Fordist labour relations, ‘collaboration’ simultaneously valorises them as expressive of an affectual co-operation.

In its conflation of labour and community, ‘collaboration’ tends to perform as a social good while its politics go unacknowledged and unexamined. ‘Solidarity’, as PWB offer below, might be a term that offers a more critical position from which to organise and intervene in the prevailing political economy. In practice it foregrounds affinities, to help one another create more just and ethical conditions for work and life through collective transformation. But, as PWB helpfully underline below, terminology requires ongoing attentiveness.

To draw attention to the relationship between higher education and the cultural industries through the lens of collaboration means reflecting on the conditions of work in both sectors. Many of us teaching and studying in the humanities and those of us working in the cultural sector face similar forms of precarity. It also means asking critical questions about the configuration of the artist and the scholar as categories of worker who love their labour for its own sake.1 Doing what you love has, for certain sectors of workers, become the ideal panacea for exploitation while simultaneously obscuring the labour of others who are less lucky with the terms underpinning their exploitation.2 The rhetorical importance of internal rather than external rewards reverberates through the narrative of alternative value that drives theatre and performance pedagogy, the arts and parts of the cultural industries. A deep personal investment in work motivates scholars and cultural workers to keep going while binding them to a dangerous neoliberal regime that relies on self-exploitation, inequity and intensified workloads.

For those teaching and studying practice in theatre and performance departments, inviting a critical approach to conditions of work appears complex. The emphasis that performance-making places on intimacy, on individuals being available to themselves and others, on taking risks and on maintaining a level of mobility and flexibility embed both productive and problematic norms. How might we promote students to attend critically to that ambiguity while keeping a focus on their status as workers? Practice-based modules represent experiences of ‘work’ while simultaneously camouflaging the actual conditions of a sector that, by and large, does not remunerate. When remuneration is removed from the equation, work is no longer really ‘work’. And in the absence of work, the rhetoric of love, civicness, community and self-development rushes in to fill the gap.

As a group of teachers in higher education primarily working in visual art and design, the PWB noted this gap between the critical theories students engaged and the individualised narratives of selfhood promoted by practice-based modules. As employability moves ever closer toward the centre of education and the gap seems to grow even wider, the need for the resources they have begun to collect becomes ever more pressing. For example, in 2010 the Equality Challenge Unit highlighted a series of gaps in work placements as part of arts undergraduate programs. These included a lack of diversity in the cultural industries workforce; difficulty for working class students to juggle placements with part-time work; the ways work placements engender inequalities (racial, gender or disability); and a lack of clarity around what is considered work experience and what is unpaid labour.3

Casting young people as responsive and available commodities reproduces dominant fantasies that position them as individualised agents in service to an exploitative neoliberal capitalist economy. Both PWB and I believe that a combination of systemic critical analysis and micro-political reflection, and spaces to undertake this work, are necessary if we are to close the gap between our critical preoccupations, our affective desires and our practices. Their book, one of the impetuses for our conversation, offers a series of pedagogical approaches and exercises that help ensure industrial contexts and conditions aren’t merely a backstage concern.

Re-imagining theatre and performance’s experiential pedagogy, and challenging increasing pressures to demonstrate our students’, and our own, employability in the face of austerity, is an invitation to work together to explore ways to critically address working conditions. This co-labouring seeks to resist being leveraged by regimes of power through its invitation to critically reflect and act on our individual experience and shared position as precarious workers.

– Elyssa Livergant

Elyssa Livergant: Can you tell me a bit about how the Precarious Workers Brigade started?

Rosa: A smaller group of us started as the Carrot Workers Collective. Some of us were teaching in higher education; it was ten years ago now, and there was already a great deal of discussion around employability. At the time, it wasn’t framed in such a way, though – not as strongly. But there was a disconnect in the arts, humanities and cultural studies between what happens in students’ critical modules – where you would read your Marx and your post-colonial feminist theories and try to think through them – and the practice-based component of the course where the message that the institution formulates for students and the subjectivity it promotes is one of cutting edge competitiveness. There wasn’t much space to talk about that gap. This took on a specific urgency around 2010 with the introduction of student fees and the student struggle. At the time, some of us put forward a proposal for others to come join us in a workshop related to a residency at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London.4 And through that we met these great people; comrades who were also wrestling with these things. At that point, it made sense to change our group’s name to the ‘Precarious Workers Brigade’. The name not only resonates with working conditions of the cultural sector but also reflects how we, as cultural workers or students, operate in solidarity with other kinds of struggles.

Frida: The name also reflects our interest in acknowledging, investigating, thinking through different aspects of precarity, including but also beyond labour. For example, the idea and experience of debt. This aspect of precarity was becoming increasingly pressing in the early days of Precarious Workers Brigade, circa 2010, with the increase of tuition fees and wider cuts to the welfare state. The aim was to further open the group’s considerations and make those links.

Elyssa: How do you work together as a collective?

Frida: To address the question of working together we collectively formulated an ethics code help us navigate how we work as a group and in relation to invites and projects. It’s a compass we refer to when we make decisions about what we want to work on or why we should be working on it. This includes considerations around peoples’ interests, and an invitation’s relation to the political project of fighting precarity that we’ve outlined for ourselves. Our code of ethics offers us a set of questions that help us map the ‘opportunity’ in question in terms of the ethics associated with that invitation. That’s been quite helpful. We also send the same set of questions to people who invite us. Their answers to these questions help to make the nature of that project more transparent. And that kind of transparency is not a regular practice for workers in the industry. You often find out the details later, usually in the middle of the working on something, or not at all.

‘Bust your boss’ from Training for Exploitation?, p. 53. Download PDF.

Frida: Projects we take up often come out of the workshops that we do. Years ago, when we first drafted the pack that eventually became our most recent publication Training for Exploitation?: Politicising Employability and Reclaiming Education, a lecturer from a London-based art school came to one of our workshops explaining that she’d been asked to implement a year-long work placement into her course while students continued to pay part of their fees. She didn’t know how to think about that and it became a moment for her to come to the workshop and collectively think about it. And we realised that was an emerging issue and decided to produce some material around it.

Elyssa: What do you think about the term ‘collaboration’ in relation to the issues and struggles PWB addresses and are engaged in? Is it a term you come across or think about?

Frida: In the book, we note that the word ‘collaboration’ is often used to talk about content production. Art and design students do a lot of collaborative projects or collaboration. So, it’s often used on that level. But it’s rarely used to address issues of labour or how we relate to each other as individuals all looking for work. That process, the one of being a worker, is individualised. Where’s the collaboration there?

Elyssa: Theatre is thought of as a shared project that can’t exist without collaboration, without co-operation and co-working. Some of the claims for theatre’s resistant potential as an art form rests on it as a collaborative enterprise. Oddly enough, though, the material conditions of this co-labouring are rarely discussed.

Rosa: I’m thinking of the context of our conversation. About performing arts, specifically. Collaboration has been a preoccupation in this area for ages. It feels to me it’s becoming difficult to use it as a term without further qualification. Are we looking at collaborative organisational structures? Are we looking at collaborative economies around projects we might do? Or is it just one of those key words that covers up rather than explores what’s at stake? I wonder if one of the reasons it’s been around for so long is precisely how it obscures. I’m thinking of collaboration as one of the various terms that we can use to think about co-existence, co-dependency, being-together; but it is one that, in a way, is precisely productive already. So, you collaborate to produce work. What comes to mind piece by Florian Schneider from about ten years ago that was quite useful.5 Collaboration can be very opportunistic, it can be a collaboration with regimes of power. Recently, for me at least, solidarity is becoming a much more precise tool to think through these issues.

Frida: Collaboration doesn’t define the nature of the relations between the people who are in collaboration. In that sense, it obscures.

Elyssa: You mentioned employability as a term that informs higher education policy and practice. What is the employability agenda?

Rosa: The UK government has been speaking about employability since 1998. They define it as the ability to move self-sufficiently in the labour market, to realise potential through sustainable employment.6 This connects to some thinking by education scholar Tyson Lewis. He was noticing how students are told that through learning they should fulfil their potential as human beings, except that potential should also be something that capital wants. The problem is how to break that very important nexus. What is that leaving out as an option for individuals and for groups? I think it’s leaving out even the right to challenge the work ethic and the jobs that are available and the quality and conditions, terms of employment, of those jobs. And it places the anxiety and the violence of the job market and the economic crisis within the individual rather than in a systemic failure to redistribute opportunity.

Frida: Yes. It reinforces this idea that work is inherently morally good and is something that gives rise to identity, purpose and social recognition. To question work itself is completely taken off the table.

‘Analysing an advert for an internship/volunteer opportunity’, Training for Exploitation?, pp. 38-39. Download PDF.

Elyssa: While students may appreciate being critically aware about other practices and modes of thinking, they may not want to analyse and reflect on themselves as workers within a wider political economy. This year I convened a module called Livelihoods, a final year zero-credit compulsory undergraduate module focused on bridging the gap from university study to working life. Students choose six sessions to attend throughout the semester. One session focused on debt, and it was the most well attended session. Another session addressed freelancing and alternative models of co-operation and I invited Altgen, a group of young freelancers set up as a co-operative, to run a workshop. Students seemed to struggle to understand what co-operative models of organising labour had to do with them. In module feedback, some students commented that it was irrelevant to their future. In another session one of our graduate companies, who has been successful in the industry (and we should qualify what we mean by ‘success’), came in to talk about their career trajectory. They reflected on the important role housing benefits played in their development as a company. Some of the students seemed incredibly offended by this aspect of their presentation. They related being on benefits with a state of poor or non-achievement that was in opposition to their position as university students. How might you bridge that critical gap, between theory and students’ own condition as workers, and should you?

Frida: I remember hearing something from graduates already a year or two into their field. They said that moment was when they really needed our workshop but that they probably wouldn’t have understood its value while they were still in college. Since graduation they had been living and experiencing the issues and practices we were addressing. This, for us, was the big dilemma. We tried to reach interns, but they are dispersed and it is very difficult to draw people together. You would like universities to be an opportune place to engage these issues, especially as this is where students gather. And yet, university students might not be in that place where precarity is really felt as a pressing issue. It might be that they are yet to experience the affects of these crippling conditions. Or, perhaps, they may be holding on to the idea that they might be the exception to the rule.

EL: Possibly. I also wonder if anxiety is a strong force in that resistance. It’s too scary to think about what comes next.

‘Target practice’, from Training for Exploitation?, pp. 32-33. Download PDF.

Rosa: It’s funny that you mentioned someone on benefits. That option has changed, deeply. I was recently reading a piece by Ivor Southwood where he makes a link between employability, as its used in education, and the other place where it crops up, in government lingo around workfare. 7 The benefits regimes are more and more linked to compulsory retraining, to free labour. And that’s attached to sanctions. People who refuse to work for free may stop receiving benefits as a retaliation measure. But to your question about bridging a critical gap, different pedagogies come to mind that might be effective, one systemic and the other micro-political. On the one hand, I wonder how much we could address the politicisation problem sideways? Allowing students to have not only a good sense of industry income levels and precarity levels but more broadly to integrate that with an analysis of cultural policies and how education has been mobilised in relation to these policies. As a more general discourse this might help them to place themselves in a more societal socio economic analysis, which in the humanities not that many people do or are exposed to. On the other hand, and this is probably where Precarious Workers Brigade has had more experience, is to start where people are. To start with pedagogies on a micro-political level. To start with an analysis of your life, of your conditions now. Many of the radical pedagogies that we also mention in Training for Exploitation are useful for creating small processes and exercises that students can do individually or collectively, in their work placement or in class. What is your background? What do your parents do? Who pays for your life right now? What kind of networks of support do you rely on? Who’s a citizen? Who’s on a visa? And so on. It’s about staying with the process with that group and acknowledging that anxiety also exists for us as teachers, as people working in the academy.

Elyssa: Might it be productive to characterise the relationship between higher education and the cultural industries (or industry more broadly) mobilised through the employability agenda as a collaboration with regimes of power? And if so, what is made operable by that collaboration?

Rosa: The hesitation I’m feeling is that your question makes me think there would be some sort of collusion or agreement by default between the mission of educators and the interests of an industry. That makes me wonder immediately what the role of the student is in all of that. Perhaps, it might be more interesting to reflect on what the potential terrain for collaboration could be between the humanities and the cultural industries in the face of current challenges. The humanities, critical studies and reflective practices in further education, that kind of trajectory, is under attack. It is not valued for its capacity to produce a certain kind of subject. At the same time, within the current political shifts we’re living through, parts of the cultural industries (and we should discuss what counts as cultural industries but for now let’s use the term as a placeholder) are also under attack. There seems to be a deep transformation of both areas – the humanities and the creative industries. So, facing these challenges together might be a terrain for exploring collaboration. Perhaps one of the things the cultural sector could do a bit more effectively is to think about how we as workers collectively address governments, the private sector, the tourist industry, and the profits made from these. It would be a good time for the cultural sector to be much more of a presence in active citizenship because of the skills it can bring to those debates. Not as a protectionist thing, for example ‘look at us we’re an exception’, but because the arts and public support for education and arts is part of the vision of collectivity that is going down the toilet.

Elyssa: How might we think about the university as a site of co-labouring, a site populated by a range of workers who are faced with ever worsening labour conditions? I’m thinking of the recent announcement of mass lay-offs of academic and professional staff at the University of Manchester and the outsourced cleaners on strike at the London School of Economics and King’s College London.

Frida: To make visible that there are different forms of labour at play in the university, to bring that up and to encourage connections between the different struggles is important. While we may be in different modes of work, in different sectors, at the same time, we are all subjected to the same regime and we have more in common than in difference. The LSE cleaners are a good example of that right now. A small group of students have been very active in trying to make this struggle more visible on campus. There are attempts being made and perhaps we can do more. As workers, no matter what sector you are in, it’s almost certain that you’re facing bad practices and bad prospects. To make those connections between people rather than to divide them further is important. Again, solidarity as a key word rather than collaboration. I’m really not convinced by this word ‘collaboration’ – or at least it needs regular interrogation. The same goes for solidarity. Language can be tricky and we take it for granted at our peril.

Rosa: One of the assumptions that the university doesn’t acknowledge enough is that many students are workers already, just not in our sector or in the sector they are probably training for. I’ve been speaking with someone who is doing a project called Unpaid Britain, looking at the various ways employers from a range of industries avoid paying workers what they are due lawfully. Apparently, the creative industries are the first or second most toxic environment for work. The number of students in service industry work in London is high and few of them know they are entitled to paid holidays or sick leave or what unlawful termination is or what unions or processes they can access. I’m also not sure how many of our colleagues know these things, as they start to get axed. That’s when you discover – hey, there’s a union, I should go talk to the rep, something is coming down. Maybe this is helpful in terms of what the university might offer us – a place for thinking together about our status as workers rather than as entrepreneurial selves.

Further Resources

Carrot Workers Collective, Surviving Internships: A Counter Guide to Free Labour in the Arts, 2015, https://carrotworkers.wordpress.com/counter-internship-guide/

Fighting Against Casualisation in Education, https://fightingcasualisation.org

SMarteu, http://smart-eu.org/about/

Artists’ Union England, http://www.artistsunionengland.org.uk

Equity UK, Professionally Made Professionally Paid Campaign, https://www.equity.org.uk/campaigns/professionally-made-professionally-paid/

Gulf Labor Artist Coalition: Who’s Building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi?, http://gulflabor.org

Erik Krikortz, Airi Triisberg & Minna Henriksson (eds), Art Workers: Material Conditions and Labour Struggles in Contemporary Art Practices, 2015, http://www.art-workers.org

Basic Income Earth Network, http://basicincome.org

Notes:

As someone who has spent twelve years as a casualised worker in higher education and thirty-three years working as an artist and cultural worker a commitment to work and a life of precarity, associated with both sectors, is deeply embedded in my psyche. It is interesting to note that prior to his role heading the Prussian educational administration Humboldt proffered the Romantic era’s familiar character of the artist as a model for the ideal individual who ‘loves his labour for its own sake’ in his 1792 tract The Sphere and Duties of Government, trans. by Joseph Coulthard (Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1996 [1854 edition]), p. 28. ↩

Miya Tokumitsu, ‘In the Name of Love’, Jacobin, 13, 01 December 2014, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/01/in-the-name-of-love/ [accessed 30 May 2017]. ↩

Kim Allen, Jocey Quinn, Sumi Hollingworth and Anthea Rose, Work Placements in the Arts and Culture Sector: Diversity, Equality and Access (Equality Challenge Unit, 2010). The Equality Challenge Unit, a public body funded by the UK higher education sector to further support equality and diversity for staff and students, commissioned the study. It sought to address a lack of diversity in the cultural industries while acknowledging that HEIs are under pressure to boost employability of students. ↩

Precarity: The People’s Tribunal, ICA London, 20 March 2011. ↩

Florian Schneider, ‘Collaboration: The Dark Side of the Multitude’, SARAI READER 06: Turbulence, ed. by Monica Narula, Shuddhabrata Sengupta, Ravi Sundaram, Jeebesh Bagchi (Delhi: Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 2006), pp. 572-76. ↩

See Ronald W. McQuaid and Colin Lindsay, ‘The Concept of Employability’ Urban Studies, 42.2 (February 2005), 197-219 and UK Commission for Employment and Skills’, Employability Skills: A Research and Policy Briefing (March 2010). ↩

‘Against precarity, against employability’, Mapping Precariousness, Labour Insecurity and Uncertain Livelihoods, ed. by Emiliana Armano, Arianna Bove and Analissa Murgia (Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 70-81. ↩

1 note

·

View note

Text

Save the Common House

The Common House is a radical community-building space in East London, which we and many other fantastic groups, initiatives and activites have called our home for the last 4 years. It needs urgent financial support to stay open (more info below)!

https://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/savethecommonhouse/

The Common House is an experiment in building a commons – a space that is organised and structured by collective activity, not by money or property rights.

In a city where social space is increasingly private, we have been carving out a common space shared by a wide range of groups and projects. It is a space where individuals and collectives can meet, come together to share skills and ideas, support each other, heal, grow, and use our shared experiences to support political action for social, economic and environmental justice in East London and beyond.

The Common House also provide a space for groups with little or no resources, operating on the basis of mutual solidarity.

We have hosted over 7000 hours of community action at the Common House since September 2013 - including over 500 meetings, 350 classes and workshops,120 complementary healthcare sessions, 80 reading groups, and 110 film screenings. In other words, we have supported activities on a full-time basis for nearly four years through voluntary collective effort.

What would you be funding?

As no one is paid to run the Common House, your money would go towards securing the space and keeping the lights on while we source more sustainable, long-term funding. In doing so, you would be supporting all those that use the space - the following is just a snapshot of the kind of work the space has helped to facilitate over the past four years:

Accessible and affordable healing and community support: Common Hair haircuts, queer friendly yoga, community massage and Common House acupuncture clinic.

Forming and facilitating politicised peer support groups such as: Mental Health under Capitalism, London Gender Support, Feminist Fightback, Politics in Love, Sex and Relationships, Precarious Workers Brigade, Radical Education Forum, London Birth Gathering, East London Strippers Collective and No Fly on The Wall – a platform for black women, which also runs workshops and masterclasses.

Collective learning and doing through projects like: Riso Club – learning about and making Risograph prints; x:talk – a sex worker cooperative supporting peer to peer ESOL classes for sex workers; Autonomous Tech Fetish – hosting workshops on topics such as encryption; biometrics and health policy, Babels Blessing - running affordable classes in Yiddish, Arabic, Hebrew and Sign Language; Antiuniversity; In Sight Theatre - a collaboration between learning disabled and non learning disabled actors; Sex Worker Opera; and the Radio Ava Project - a radio station for and by sex workers.

The Common House has hosted, supported or occasionally even birthed some momentous political organising and campaigning, such as: United Voices of the World, the grassroots union who won an epic recent victory with the striking LSE cleaners, Black Dissidents, Corporate Watch, Anarchist Federation, East London Radical Assembly, Plan C, Radical Housing Network, who have recently been mobilising for Grenfell Tower, Occupy, Friends of the Joiners Arms, Liberate Tate, People and Planet, Sisters Uncut and too many more to mention.

With your support to keep the Common House open, much more can surely be done!

https://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/savethecommonhouse/

0 notes

Text

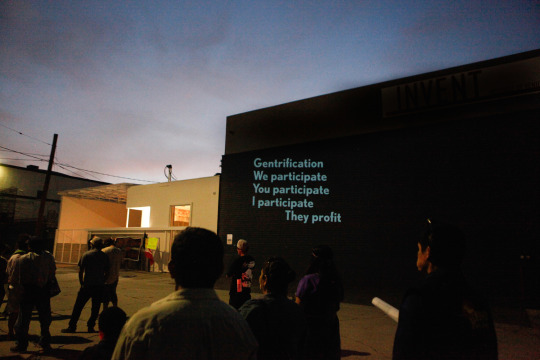

Letter in solidarity with the struggle of LA's Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement

If you are a group/collective/artist/campaign & want to sign, please contact Southwark Notes at: elephantnotes (at) yahoo.co.uk

Art Galleries: Stop the Gentrification of Boyle Heights and other Working Class Areas!

We, the undersigned, stand united in struggle with the residents of Boyle Heights in their resistance to the gentrification of their area. Since summer, 2016 they have staged a number of public protests against contemporary art galleries that have moved into their locality.

While it may be true that a number of these galleries did not take up residence in the area with the intent to facilitate its gentrification, their failure to take action in response to the residents demands make them complicit with this process. Boyle Heights has been home to Latina/o migrants and other migrant and working class communities since the start of the 19th Century. In recent years, the movement of contemporary art galleries into their area has symbolised the incursion of a hegemonic art world coded as white, middle and upper class. This, as in many other neighbourhoods around the world, has signalled to developers that this is an area ripe for development resulting in rocketed rent prices, and housing projects aimed at high earners and the ultimate displacement of Boyle Heights residents.

This process is by now so common that it is often portrayed as manifest destiny. The narrative of manifest destiny echoes the violence of colonial expansion: violent both in its waging of war against and displacement of indigenous and poor communities, and in consistently erasing their rights, voices and cultures. What the Boyle Heights residents are shouting is that this process is not inevitable, that local groups can and do fight to take back ownership over their area.

We extend our solidarity and support to them.

While everyone knows the arts and artists are catalysts in the process of gentrification, the arts community is often seen to be an innocent bystander or victim of this process. While this can certainly be the case (artists are sometimes among those displaced), the arts are not innocent. It is often through the arts that the cultures of existing resident communities are undermined legitimising the violence of their forced departure. It is common to hear, as we have in much of the reporting on the Boyle Heights situation (https://www.theguardian.com/…/artwashing-new-watchword-for-…), that art galleries and good coffee bring ‘culture’ to an area, as though the years of local residents’ production of their own culture, their own businesses, their own fabric of sociability and support is of no value unless it can be re-packaged and re-branded for more affluent communities.

Increasingly it is not only the presence of galleries but the involvement of artists in all manner of ‘engagement’ in the development process that signals it as the ‘better option’ than existing culture. Artists, often young, hungry and naive to such processes, are asked to help citizens to ‘vision’ (https://southwarknotes.wordpress.com/…/empowerment-for-sur…/) futures that developers and governments have no intention in realising with them. They are asked to document, ’celebrate’ and memorialise local cultures before they have even left and as though their disappearance were inevitable and not the site of an existing and very current struggle (http://www.metamute.org/…/art…/pyramid-dead-artangel-history). They are also asked to work with the police and government agencies to ‘solve’ social problems (begging, sex work etc) that are articulated by those who support the gentrification process rather than by residents themselves.

The arts organisations in Boyle Heights have said that they are there to support the residents, that they are on their side. But the residents have expressly indicated on a number of occasions how they would like this support to manifest itself: in the departure of art galleries from the area. Uninterested in showing this kind of support, the galleries are aligning themselves with the police (who claim to be mediators) and other forces to protect their interests and those of the property developers and would be residents that are indeed their patrons – exposing exactly the network of interests in which they are a part.

This is not to say that artists cannot play a role in local communities. Indeed many within the resident groups demanding the departure of galleries in Boyle Heights are artists. They are artists and residents with a stake in their local area, willing to listen and work in solidarity with their neighbours.

They join a growing group of artists and cultural workers fed up with the role of the arts in the gentrification process. These artists quit when they see that their work is being instrumentalised by the forces of displacement and development, get involved locally, hand their galleries and organisations over to direct governance by local communities who generate uses and aesthetics that challenge those of the visual and cultural hegemony of the marketised contemporary art world. They make work with residents in support of local struggles to be used by those struggles rather than conceived purely as material for circulation on the international art market.

These artists and galleries take a strong stand against the violent war waged on victims of the gentrification process.

We implore the galleries in Boyle Heights to join them and depart from the area.

In solidarity,

Southwark Notes (London)

Precarious Workers Brigade (London)

no.w.here (Artist run project space, London)

Design Action Research Hub, London College of Communications

56a Infoshop, (London)

Concrete Heart Land (London)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

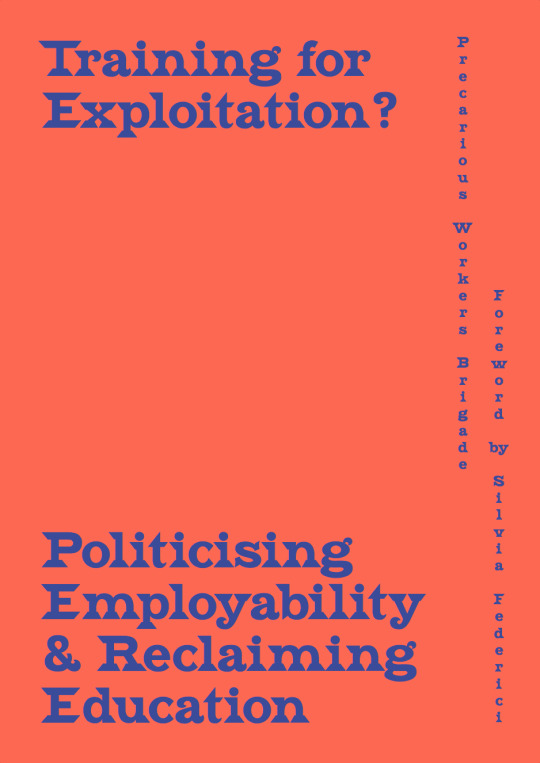

Out now: Training for Exploitation?

Our new critical workbook 'Training For Exploitation? Politicising Employability and Reclaiming Education' is now available internationally and as a free download through: http://joaap.org/press/trainingforexploitation.htm

This 96-pages workbook is a critical resource pack for educators teaching employability, ‘professional practice’ and work-based learning. It provides a pedagogical framework that assists students and others in deconstructing dominant narratives around work, employability and careers, and explores alternative ways of engaging with work and the economy. Training for Exploitation? includes tools for critically examining the relationship between education, work and the cultural economy. It provides useful statistics and workshop exercises on topics such as precarity, employment rights, cooperation and solidarity, as well as examples of alternative educational and organising practices. Training for Exploitation? shows how we can both critique and organise against a system that is at the heart of the contemporary crises of work, student debt and precarity.

'For many years the members of Precarious Workers Brigade have been developing insightful analyses, tools and actions questioning wageless and other exploitative forms of labour in the arts and education sectors. ‘Training for Exploitation?’ is no exception. As an educator I support the effort the book makes to provide the analysis and the tools needed to challenge the conversation, now predominant in the classroom, concerning ‘employability’. As a feminist I recognise many of these tools from past and contemporary practices of consciousness raising. They are effective and I encourage readers to use them'. - Silvia Federici

Written by PWB, Foreword by Silvia Federici Published by Journal of Aesthetics & Protest (JOAAP) Designed by Evening Class, Printed by Calverts 96 pages, black and white with color cover

The book is an open invitation to both educators and students to use and build on. We’d love to hear what you make of it!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

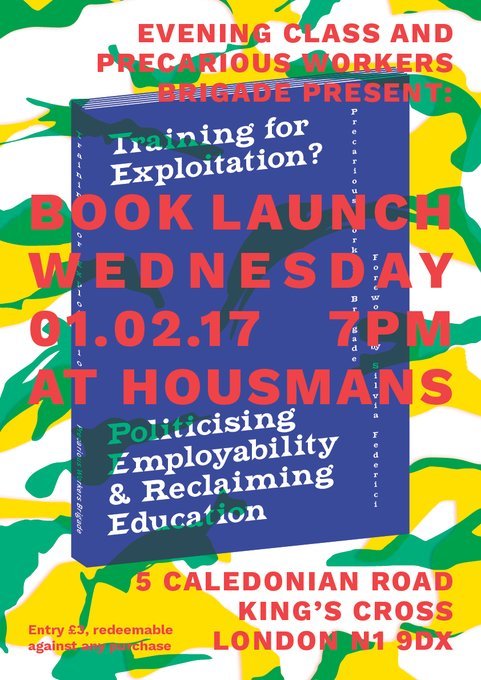

Join us for the book launch of ‘Training for Exploitation?’ on 1 Feb 2017

Join us and the book's designers, Evening Class, on 1 Feb, 7pm at Housmans bookshop for a celebratory launch of our new publication 'Training for Exploitation? Politicising Employability and Reclaiming Education'! Entry £3, redeemable against any purchase

With a foreword by Silvia Federici and published by the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Press, 'Training for Exploitation?' is a critical resource pack for educators teaching employability, 'professional practice' and work-based learning. Pre-order the book here: http://joaap.org/press/trainingforexploitation.htm. Free download available soon.

"For many years the members of the Precarious Workers Brigade have been developing insightful analyses, tools and actions questioning wageless and other exploitative forms of labour in the arts and education sectors. 'Training for Exploitation?' is no exception.As an educator I support the effort the book makes to provide the analysis and the tools needed to challenge the conversation, now predominant in the classroom, concerning 'employability'. As a feminist I recognise many of these tools from past and contemporary practices of consciousness raising. They are effective and I encourage readers to use them." - Silvia Federici (from the Foreword)

This publication provides a pedagogical framework that assists students and others in deconstructing dominant narratives around work, employability and careers, and explores alternative ways of engaging with work and the economy. Training for Exploitation? includes tools for critically examining the relationship between education, work and the cultural economy. It provides useful statistics and workshop exercises on topics such as precarity, employment rights, cooperation and solidarity, as well as examples of alternative educational and organising practices. Training for Exploitation? shows how we can both critique and organise against a system that is at the heart of the contemporary crises of work, student debt and precarity.

1 note

·

View note

Text

PWB Press Release: ‘Training for Exploitation? Politicising Employability and Reclaiming Education’. A forthcoming publication by PWB due out January 2017

Foreword by Silvia Federici. Published by Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Press. £5/10, available online for free. For further information see below, to reserve a copy email [email protected] or [email protected]

"Power was trying to teach us individualism and profit... We were not good students." Compañera Ana Maria, Zapatista Education Promoter

Training for Exploitation? is a resource pack for educators teaching employability and work-based learning. It provides a pedagogical framework aimed at assisting students to deconstruct dominant narratives, develop their critical faculties and explore alternative ways of engaging with work and the economy.

Work related learning is ever more prevalent in higher education– be it through work placements, industry projects or career advice sessions. You can’t walk in to a university these days without seeing the word employability: prizes are given for the most employable student; employability workshops cover topics such as networking and personal branding; and many work placements end up being little more than a way for companies to cash in on free labour disguised as training. But while offering to provide students with necessary skills and experience to make her more readily attractive and employable to the labour market, employability also taps in to and feeds individual insecurity, nurturing the sense of having to continually prove one’s worth and update one’s skills. The increase in student anxiety and mental health issues are often related to feelings of insecurity about the future and how to flourish in an increasingly competitive and insecure labour market.

This 97 page pack in workbook format includes:

tools for critically engaging with education’s relationship to work and the economy

ideas for topics and exercises

a bibliography of related texts

useful statistics and workshop exercises on topics such as precarity, employment rights, cooperation and solidarity

examples of alternative educational and organising practices, alternative economies and other ways of working

Published by the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest (http://www.joaap.org/) Designed by Evening Class

For further information or to reserve a copy, please email: [email protected] or [email protected]

Precarious Workers Brigade (PWB) is a UK-based group of precarious workers in culture & education. We call out in solidarity with all those struggling to make a living in this climate of instability and enforced austerity.

PWB’s praxis springs from a shared commitment to developing research and actions that are practical, relevant and easily shared and applied. If putting an end to precarity is the social justice we seek, our political project involves developing tactics, strategies, formats, practices, dispositions, knowledges and tools for making this happen.

http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/