Text

“We Sit Upon The Quay With Sphinxes...” – Notes

Six-line stanzas, but the part that makes this interesting is the interaction between metre and rhyme. While nominally this poem is in iambic tetrameter, the use of feminine rhymes,– i.e. rhymes that end on an unstressed beat,– in every odd-numbered line actually unbalances the rhythm of the metre. Here, the feminine rhymes essentially steal an unstressed beat from the first poetic foot of every even-numbered line. What ends up happening is a sort of rhythmic chain reaction, with the third and fifth lines of each stanza also beginning with stressed beats rather than the more typical unstressed beat of the iamb.

The result of this rhythmic sleight-of-hand is that the rhythm is made far stronger to the ear, while also given a great deal of motive force:– unlike my more melancholic and contemplative Tennysonian pieces, this is a poem that really wants to keep moving on. Funnily enough, this is also what makes the first line of each stanza fall rather jarringly on the tongue: these lines are the only ones to maintain the iamb in their first beat, and consequently feel extremely odd, if not unpleasant, when the poem is spoken aloud.

This strangeness of the opening iamb is quite deliberate though, as I’m sure you can guess. Anyone who knows me understands how much I enjoy using and experimenting with form, and the sort-of rhythmic reset forced by the iamb is intended to keep a listener from being too taken away by the musicality of regular metre and forgetting what it is they are actually listening to,– which moves from the mysterious to the macabre quite quickly indeed.

0 notes

Text

“We Sit Upon The Quay With Sphinxes...”

We sit upon the quay with sphinxes,

plying them with words and wine:

yours a vintage old as Rome is;

Istanbul’s a babe to mine,–

drinking as the twin pharoses

rise up from a starry line.

Above us in the rosy aether

thrums a faerie’s silk guitar,–

frosty whirligigs out-whisper

secrets netted from afar,

even as the swelling vesper

crosses over sail and spar.

Behind us are the golden chambers

where the rakes and princelings pass,–

nearby we can hear one clamber

down into the rooms of brass,

where a lady’s locks of amber

darkly frame the looking glass.

Beside us flops this smoky city

wheezing out with wild sound,–

echoes, mingling dumb and witty,

from the houses all around;

can you hear a noisome ditty

where the bondsmen lately drowned?

Before us laps the river, gnawing

at the barges tide by tide,–

do you think it will be snowing

here where line-ships gaily ride?

Do you hear the popguns going

over on the other side?

Beneath us in the loam and mortar,

beats the spirit of the world,–

sickly as the tepid water

into which the carmine curled;

have you answer to the slaughter

spread here like a flag unfurled?

We sit upon the quay like sages

delving down where life forgot,

on the stepping stones of ages

long made dust and proven naught,–

should we head back to our cages

now, before they have us shot?

0 notes

Text

Roman Caprices – Notes

References galore!– and into realms I hitherto had rarely travelled before: memes, movies, even video-games, intermixed into my usual hodgepodge of literature, classics and histories. And if I do make a mistake, then please be gentle in the comments.

Consider this following part just me showing that I've done my work. I’ll only go into the references because I never think that interpretation,– of the poem as a whole, of the content, of the ideas, etc.,– is the job of the person writing the poem. That’s really up to the reader.

Section I opens with a paraphrasing of Romans 3.13 (yes, that is a Bible reference and matching the form of the poem, i.e. a section of 3 lines followed by a section of 13), before moving on to a “Go home, you’re drunk!” reference. The first line also sounds awfully like a 60s film I saw years ago. Let me think. Oh yeah: ‘A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum’. The old women snipping at twine refers to Atropos, of the Fates, who cut the thread of life with a pair of scissors. Sweet white wine was also considered by the Romans as the highest form of wine, quite the opposite of what most people (not me, because I don’t drink and don’t know good from bad, haha) think today. ‘For reasons unknown’ also sounds very familiar to something Beckett wrote in Waiting For Godot.

Section II has the Sicilian gesture, essentially saying that his friend would ‘sleep with the fishes’. How about the ‘offer they could not refuse’? Obvious movie quote is obvious. Pollice Verso or ‘with turned thumbs’ is the gesture most closely associated with gladiatorial combat, but ‘two thumbs down’ is also a reference to Siskel and Ebert, the great movie critics. Gallia Transalpine (Southern France) and Gallia Cisalpine (Northern Italy) were both Roman provinces; essentially the friend is saying that he’s Italian and not from further afield. Naumachiae were massive staged naval battles the Romans watched for sport in basins larger than the Coliseum. They’d row out proper sized vessels and have the crews sort of massacre each other. Romans, eh?

Section III’s strange man is a reference to Diogenes of Sinope, the famous Greek Cynic (who lived centuries before the setting of the poem, but meh! This could all be going on in the speaker’s head so what does it matter?). ‘Taken a pilum to the knee’ should be familiar to video-gamers amongst you. Skyrim anyone? Lusitania was what we now call Portugal.

Section IV initially plays with the exotic imagery of Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, but couched in the vernacular of the stereotypical street hawker that one expects in the market of a foreign country. 30 denarii coincidently (or not) is the same price that Judas sold Christ to the Romans for. The idea of ages, (golden), silver, bronze and iron, is from Hesiod, the Greek poet, from his Work and Days, which outline the mythical ages of mankind. The brutish genius is none other than Ezra Pound, who settled in Italy in 1924 and whose poem Homage to Sextus Propertius provides the final line of the section.

Section V has the clean-shaven man from Lutetia, the Roman settlement of modern day Paris, so a stereotypical rude Parisian joke. And folks, that’s what you call comedy! Haha, no. There follows a reference to Aristotle’s poetics, i.e. ‘riddles and barbarisms’, which drops into the very modern ‘this is why we can’t have nice things’ reference. Crates is another Greek Cynic. Also, one to come and one to go? That sounds like Hatta and Haigha fron Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through The Looking Glass.

Section VI opens with an interesting observation on the Latin alphabet we all know and use. The letters G, J, U, W, Y and Z were not originally a part of the Latin alphabet, with G being introduced in the 3rd Century BC and Y and Z after the conquest of Greece in the 1st Century BC. J was a later development of I and is absent from earlier texts, and the same can be said of U and W, which developed from V (or VV in the latter case). Thus Julius Gaius Caesar would be written thus in classical Latin: IVLIVS GAIVS CÆSAR. ‘Proud distensions of empire’ is another line from Homage to Sextus Propertius.

Section VII is probably one of the most *ahem* adult (not mature) passages I’ve ever written. What more do you want me to say? Moving along, bastard-wine refers to either mulsum or posca, which were both low styles of wine. Why bastard? Well, both mulsum and posca were mixtures of wine, either white or red, with honey or flavouring herbs. Iove is Jove, as we’ve established with the alphabet. Romans are also fond of contractions, you know, primarily as it was a pain to hammer long names onto tablets and buildings. Caesar Imperator Augustus becomes Cae. Imp. Aug. respectively. How is this relevant? Well, Maximus Imperator Augustus must be either a pitiful attempt at nominatively compensating for something or merely the product of an overly inflated ego. Add the contraction and well... Do I really need to explain the joke?

Section VIII has relatively fewer references, I think, compared to the rest of the poem, but that’s not really saying much. Playing on the idea of Teutonic, the marches new and old refer to Neumark and Altmark, both provinces within the Margraviate of Brandenburg. Conflating wealth and stupid material things seems to be a problem with contemporary society in general. Or it might just be mainland China. Meh. The strange eidolon (let’s see how many of you know what that means without a dictionary!) echoes Yeats’ Second Coming, specifically the rough beast that ‘slouches towards Bethlehem to be born’.

Section IX starts off with the castrum, or fortified camp, which the Romans had all over the place, especially if the Astérix comics are to be believed. The border inferior refers to the border of the Roman province of Germania Inferior, which was one of two Germanic territories, the other being Germania Superior, that the Romans owned outside of Magna Germania. Another obvious video-game reference follows: ‘Thank you, said he, but our praetor is in another castrum’ = ‘Thank you Mario! But our princess is in another castle!’. The lines beginning ‘With veneer’ to ‘lost’ echo Shelley’s Ozymandias. Theoretically the subverted final line of the section is as true as the line it subverts. If all roads lead to Rome, they must simultaneously lead from Rome.

Section X actually mixes three references together, two from films, one literary. Remember Goodfellas? Joe Pesci’s speech about being funny, except reordering the lines and replacing the word ‘funny’ with the Latinate word ‘comic’. ‘I had choice words with another’ seems to be the spiritual successor of the Duke in Browning’s My Last Duchess. As to the last reference? Well, you tell me: ‘a dread judge’ that exclaims ‘I am the law!’. Sylvester Stallone says hi. Piso was a Roman judge who was famous for his extremely harsh execution of the law. ‘Fiat justitia ruat caelum’ or ‘Let justice be done though the heavens fall’ is the phrase most associated with his brand of justice.

Section XI plays off the name Piso (I have no idea if the ‘i’ therein is treated long but I’m going to pretend that it is) and turns it simply into ‘pissed’. Continuing the Roman trick of abbreviation, the speaker is thus pissed on (probably not literally) and pissed off. I do apologize; writing that out in full leave me feeling dirty, I must confess. C. f. is part of Roman naming convention (and again a set of abbreviations). The ‘f’ stands for filia, or daughter, with ‘C’ being the name of the father. As daughters tended to be named after their fathers in the Roman Empire, it’s not much of a stretch to guess what the lady’s name is in this poem (especially if you know me, that is). ‘Canis femineus’ means, I think, female dog. No prizes to anyone who can guess what the speaker is calling her.

Section XII is fairly straightforward, I think. Stolidus is an adjective, but as it refers to the baker, it essentially means ‘idiot’, literally ‘stupid [one]’. Amphorae were Greco-Roman containers used for storage and transportation, primarily for wine. As to the penultimate line of the section…I am not going to try to explain where ‘I got 99 problems’ came from.

Section XIII is very much what you see is what you get.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Caprices

I

A strange thing happened to me on the way to the forum today:

a man insulted me, saying that my throat was a sepulchre;

that I had sown deceit; and that the poison of asps was under my lips.

***

It is too much to begin with philosophy, the province of the wise;

and I will admit,– and to you alone,– that I am hardly wise

and any man that would pretend himself otherwise

is not to be trusted.

Most things today are hardly worthy of trust;

especially the promises of youth: what was assured to me

in days long past and strength long fled;– the world

I once was heir to,– and that life,– is now overgrown: I see

old women, snipping with gnarled scissors at braided twine;

old men, sipping at sweet white wine made for sweeter days;–

“Go home, senex!” I have called to them, “you are inebriated!”–

old lives travelling numbly towards their final terminus;

old loves won;–

but more often lost, for reasons unknown,

as men know not why the gods would ever favour one over another.

II

I know not why I sit here, recounting to you an unremarkable life,

my life and the spectres of days that flit across my mind.

I know not why you sit here, listening patiently to my rambling.

***

I daily suffer slights,– far too often at the hands of the low,–

and my friend,– wolfish; slavering; rather crude;–

from time to time offers me the token gift of reassuring words:

the generosity of a transalpine prince!

Cisalpine, he oft reminds me,

as we go to watch the gladiators strike each other down in the pit.

“I’d have stuck you easily if we were down there,” he said, laughing

when he drew from me no reply.

Were it a naumachia, a sea-battle,

I would have cast him into the waves in a Sicilian gesture;

or placed my foot o’er his neck, my sword upon his neck,

and given the spectators an offer that they could not refuse.

I would have watched the crowds give him two thumbs down.

III

I am too bitter, perhaps; but he oft heaps indignities onto my head:

he knows too well that I can do nothing to him; knows that

I am too old, and my wrath is much like that of a toothless hound.

***

Wandering the market, I observed, with scarce amusement

the spectacle of a strange man

who seemed to live in a clay wine-vat,

hurling insult onto all who passed him, especially those who hurried

as though in shame, with uneven gait on uneven cobbles,

as though they each had taken a pilum to the knee!

The fierce look on his masterful age-worn face reminded me

of the malformed pearl I pawned away three decades past

in mythical Sinae,–

ah! my heart grows warm with the thought of it,–

I found again whilst travelling through sunny Lusitania,–

or was it vacant Germania’s dreary marches?–

not two weeks ago!

IV

“Pearl ex India Orientali. Taken from robe of half-demon prince

who rules with iron rod from pleasure dome of cloud.

Good price I give you, special for you. xxx denarii.”

***

Laughing for some reason,– I still know not why,– I paid

my younger self what was owed him:

a debt of thirty years

in coins, of silver and of bronze, and

in years, of my life’s last and iron age;–

but not all of them, for a man must keep

some regret with him to seem truly learned,–

as for the pearl,

I had it sent off for safe keeping

only just yesterday;–

as the brutish genius who came to Rome

some eighty,– no,– ninety years ago had said:

‘long standing increases all things regardless of quality’.

V

Had he been a poet less profound, he might have added:

‘…in certain cases, that increase is purely on the horizontal’.

Poets,– even the least of them,– may say such things with impunity.

***

But how wonderful it is that the whole world lives under

the auspices of a single crown, a single coinage, a single law,

and a single mother tongue!

To this lady from Lesbos, I say,

“Away with you!”

and she is away; to the clean-shaven Lutetian, I call,

“Come!”

and he gestures at me energetically with a hand that answers

something altogether too vulgar to transcribe;–

and to this

some say that we must make provision for barbarisms and riddles:

this is why nice things cannot be had.

A pearl to Crates, I suppose.

VI

I will sprinkle my scripts liberally with ‘v’s for such is

the Roman manner; and don’t you tell me to dispense with it!

Or would you prefer to have the barbarians tri[v]mph?

***

Not, triumph, perhaps, but corr[v]pt;

but to that, I have an answer:

we must to bring them into the fold; make them Roman and Romans

and citizens,

so that they may breed some continuation of our ways

and become, with time and custom, stern outposts of dominion secure;

we must them corrupt and in doing subvert

those who would make us

no longer us!–

such were the words of the orator in the forum,

extolling proud distensions of empire;

expounding upon the greatest truth I know:

all the world is Caesar’s for he runs it best!

VII

Now there’s a thought that warms one in this long season

of melancholic bile-black winter;– and it hardly helps

that I’m not suited for the cold; not this kind of cold, at least.

***

Lately too,

I’ve been kept awake at night; outside my window,

when the hour is late and the moon waxes gibbous to

the stupid gibbering of the drunkards,-

you know who you are,–

raising bastard-wine and high heaven or whatever it is they worship

to the scurrilous whores of the barbican who bark obscenities

between rough patches and wet sounds,–

O! O! O! O Iove!–

outside my window,

keeping me awake;– and keeping my neighbour awake, I’m sure,–

and I’m sure I’d appreciate these moonlit Boreal nights the better

if Maximus [Imp.] Potentius would shut up!

VIII

I can see the dark forest outside my window, dark outside

my window,– but there is something there that unsettles me:

I can see a distant light shining far and far away.

***

There flames what seems a very extraordinary light

from across the marches in the east;–

across the marches new that lie beside the old

by barbarous tribes of ancient malcontent;

the seeds of what we call today civilization may germinate

into the crimson flowers of blazing war; supplanting

Roman honour and Roman civility and Roman rule

with impoverished and mistaken facsimiles;

conflating wealth and stupid material things with

nobility and erudition and meaningful discourse;–

that I could think I saw a strange eidolon slouching towards Rome

from out the burning tracts of empty sands and hungry forests

of nameless vast Teutonic lands.

IX

It is of no consequence; and several days later I rode out

to the castrum by the border inferior on an errand.

Arriving at my destination, I delivered a missive to an aide.

***

“Thank you,” said he, “but our praetor is in another castrum.

Will you stay the night or will you go directly?”

With veneer of cold rebuke and lips of marble,

that like a shattered monument half-sunk

condemns the works of passing days with glory lost,

I declined reply.

Around, a number looked on me an interloper

from a hostile home;

some had choice words;–

I merely gave them a Lutetian gesture and remounted,

turning my steed towards the gate,–

urging my steed down the endless road leads me far from home,

for all roads lead from Rome.

X

Who amongst us is a wise man, or a man of many seasons?

Who amongst us has yet to prove himself a charlatan?

Who amongst us is endued with knowledge unadorned?

***

One man once exclaimed that I made him laugh, that my speech

seemed somehow comic, as though I were a funny prop, an object

of laughter, as though I was there to somehow amuse him.

Comic! Is it my manner or my speech? How am I comic?

I had choice words with another thereafter.

I heard this morning

that that same man was executed yesterday for some petty crime.

The state is the better for it.

“In any equation, I rather be Piso:

in dispensing sentence with a masterful hand,–

for the sorrows of others are not my concern,–

a dread judge heedless of care or consequence;–

by blind Justice or idiot god, know that I am the law!”

XI

I am not Piso but merely pissed, and p. on, and p. off, I suppose.

I suppose that you would like to be a Piso as well, you dog.

I do wish that more people were not themselves but others.

***

That woman, who we have called our mutual acquaintance,

that patrician daughter of C. [or C. f. as per modern convention],

has been detestably beautiful,–

I’ve been told that men ought not

refer to a beauty like her in so unspeakably uncouth a fashion,–

regardless, it does not become her.

Allow me to elaborate through an example:

with one careless hand, one gesture, she discarded my gift

onto the blazing hearth,–

where offerings should have been

placed reverently and persistently and dutifully before,–

and watched it burn with a smile…

canis femineus.

XII

Dogs need no graves, nor long for orisons to send them off;

nor mind the half-baked doggerels of rough satiric pens;–

well-remembrance is an idle ornament on a life well-lived.

***

People have made funerals too grand, indeed too sentimental;

or make too much of the show of mourning,– and it is all for show,–

and hagiographies will always forget the most important details,

or omit the finest things in life:

what one had for breakfast;

or speaking with a friend on stately matters and the weather;

or mocking that stolidus of a baker for selling poor bread;

or hearing one’s neighbour cursing loudly incoherent

when he smashes his second amphora this week!

I too have heard my neighbour say, in trite attempt at humour,

that his life is difficult:

“I got xcix problems,” he said.

I can tell that being a cretinous asinine scumbag is not one thereof.

XIII

I do not think that he has spent much time looking at the stars,

watching the starlight foaming up from the endless falls

of eventide that nightly bathe swift Diana’s tranquil arbour-bed.

***

They will paganize my household gods, once I am gone.

They will spin what gold they may from the works I leave behind,

supposedly in my name.

I have often told people

that heavy coins have no place in an urn of brass.

After all, someone, someday, will doubtless try to fish them out,

and I would rather not be disturbed.

An urn of white ash

covered over with a grassless mound of earth is hardly splendid,–

but I cannot find it in me to be unhappy at the prospect:

the quiet, I am certain, will suffer me best.

It is time already?

Must I go?

0 notes

Photo

Drafts of Tanka: 利潤. As you can see, I occasionally switch between scripts when I work, with ‘Tanka poetry’ being in the Latin, and Sekigahara beneath being written in Kurrentschrift.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lines by Gerontius – Notes

For me, it always goes back to Tennyson; “The Lotos-Eaters” and “Tithonus” in particular. Rhyme Royal for the first and last stanzas, and the middle stanza is, save for its last line, all in iambic hexameters. I must confess that I find it easier to think in hexameters or heptameters rather than pentameters, but that might just be me.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lines by Gerontius

ab aeterno

Let us go. There is nothing for us here.

The world is all too much for us to bear,

and little that would bring us joy is near.

Consumed are we by time, and time by care,

and there is little in us left to share

when life’s assurances have proven wrong.

Our lives exceed us; we have lived too long.

How oft we hear those ghostly voices that remind

of happy days that once were ours long ago.

How oft we see those ghostly faces that remind

of friends all gone before us to the earth below;

yet lingering unlike ghosts, when motes of daylight break

on snowy mountaintops that dwindle distantly,

or ivied ruins left to moulder thoughtlessly,

or mossy plots of age-worn marble silently

recalling us from hope; or when by night we wake

from sad dreams of mingled faith and melancholy,

the grot and cell of all of us that yet remain.

Alone, the sailor disappears into the main.

Alone, the thrush sings shrilly in a darkling plain.

Alone, alone, we suffer only life through loss and pain.

Our lives exceed us; we have lived too long.

Sickly lies the heart, and weak is the will,

and weaker still are those that once were strong.

Must we endure when we have had our fill?

What friends of ours are there to greet us still?

It is time we made for another shore.

Let us go. We will no longer wait for more.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

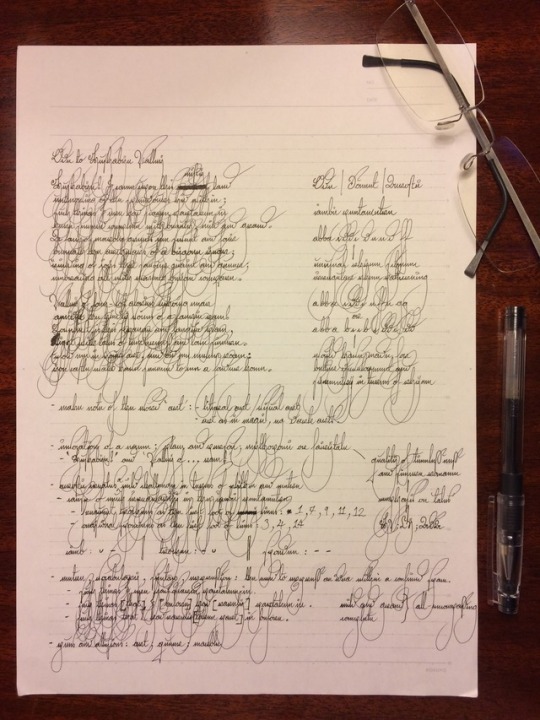

Someone asked if I prefer writing by hand or on the computer. Well...

Above is actually the final draft for the ode that I wrote for @hushabyevalley. Top left quadrant is the poem itself; top right are notes on rhyme schemes and meters; bottom half are the points I used to write the poem’s notes.

If anyone’s curious about the script I use, it’s actually a variation of a 18th century Germanic script called Kurrentschrift. It’s a little hard to read for most people as most Western scripts are in Latin script, I know, but I rather like how it looks. :)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tanka: 利潤 – Notes

In romanji, the title is rijun, or, when translated into English, profit.

I would recommend reading the history of the Sengoku period in general as it is a fascinating period, but of particular relevance to this poem is the Battle of Sekigahara, which took place in October when Japanese maple trees take on the red livery that they're famous for.

Kobayakawa Hideaki and Ōtani Yoshitsubu were both generals in the Western Army of Toyotomi Hideyori, facing off against the army of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Now, warfare in Japan in those days included a surprising amount of bribery as the daimyō of Japan had fairly mercenary views regarding their loyalty to the various factions and powers that waxed and waned on the Japanese isles. Kobayakawa was one of those lords that had been offered land and power by Tokugawa if he turned on the Western Army and, after no small amount of vacillation at the beginning of the battle, ultimately committed to Tokugawa’s cause and turned on the nearest forces of the Western Army, headed by Ōtani.

Long story short, the defection of Kobayakawa triggered the defection of a number of other daimyō which ultimately won the day for Tokugawa. Ōtani committed suicide upon being defeated and, not two years into the ensuing consolidation of Tokugawa rule as Japan’s last shogunate, Kobayakawa died rather suddenly, quite unable to enjoy the lands and fiefdoms gifted to him by Tokugawa. Just as Tokugawa outlived his feudal predecessors Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, so too did he live to consolidate his power over the country, thus being able to enjoy ‘the fruit of latter spring’, unlike the two ill-fated samurai Ōtani and Kobayakawa.

I’m not particularly well-versed in Japanese forms, but I am interested in experimenting therein. The tanka form contains lines of varying number of ‘on’ or 音 in the pattern of 5-7-5-7-7. From what I understand this is not a direct analogue to syllable or stress, which is one reason why adapting the form for Western languages is problematic, to say the least. One thing to note though is that long vowels in Japanese, such as ‘ō’ constitute two ‘on’ rather than just one, hence why I count ‘Ōtani’ as four ‘on’ rather than three. I may not be right about this.

Ah well.

#notes#tanka#japanese poetry#historical#sengoku jidai#sekigahara#tokugawa ieyasu#kobayakawa hideaki#otani yoshitsugu#profit

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tanka: 利潤

Kobayakawa

thus honoured Ōtani

when the leaves bloomed red.

Tokugawa alone will

eat the fruit of latter springs.

#poem#tanka#japanese poetry#historical#sengoku jidai#sekigahara#tokugawa ieyasu#kobayakawa hideaki#otani yoshitsugu#profit

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ode to Hushabye Valley – Notes

Sweet and sincere; apropos for the good lady @hushabyevalley whose art inspired it, I should hope.

Here’s the usual note that accompanies most of my poetry, and I must apologise: it’s long and while I would be overjoyed if one were to read it, I do realise it’s not particularly interesting. Nonetheless, I would like to explain the hows and whys of a dedicatory poem, so if you want to understand all the allusions of the poem, please read the bit up till the second line of ‘===’s. Under those will be a more technical look into the workings of the poem. If you happen to stick with me from start to finish, then you have my sincerest thanks :)

===

So, the poem begins with an invocation to Hushabye, the eponymous lady of both the fantastical valley and the castle that is situated therein. Please visit the good lady here or here.

Now, world-building is a fundamental aspect of high fantasy and science-fiction, and the world of Hushabye Valley is, at least to me, one that is suffused with romance, timelessness, fantasy, and quiet pathos,– something which I find in all three of the good lady’s ‘tales’: Hushabye Valley (fantasy), Calabi Yau Forest (fantasy), and Ada (sci-fi, but otherwise suffused with the same charm as the others). While the combination is becoming far more popular these days, high fantasy and slice-of-life are not related genres traditionally, as high fantasy is predominantly preoccupied with grand narratives and quests (think C. S. Lewis or J. R. R. Tolkein) while slice-of-life is focused on the memorable moments of everyday life. I find the good lady makes them work wonderfully well, hence the rather odd turn of phrase in ‘complete with beauty, mild and grand’. ‘Mild and grand’ are not cognate ideas, but by placing them both as interlinked qualities of a singular ‘beauty’, it (hopefully) suggests the all-encompassing nature of the splendours that Hushabye portrays in the valley.

Puns and allusions are important in an ode of this kind: in a celebratory poem, it should be evident to the addressee exactly what it is that they have done or created that has garnered said praise. In equal measure, if one is sincere about one’s praise or admiration, one’s writing should show a certain amount of knowledge and love of that which is spoken. Some of these are, admittedly rather straightforward, such as ‘misty’, which alludes to the good lady’s tumblr ask: ‘Throw a question into the mist’; ‘a face of marble’, to the rather adorable groundskeeper and main character of Hushabye Valley, Marble; and ‘the archways of a bygone year’, to the banner of Hushabye Valley’s Patreon page. The last one is a little tenuous, if I had to be honest, as the emphasis in the banner is on the four plinths that flank Marble, but I felt ‘archways’ scanned better poetically than ‘plinth’. If I had to use ‘plinth’ instead, I’d have rewritten the line as a hexameter one thus:

“Between the plinths engraved with words long worn away;”

‘Queer’ is another word I chose due to its double meaning, due to both its more traditional sense of strange or unusual,– and thus apropos to describe the faerie aspect of Hushabye’s ‘tales,– as well as the presence of yuri/girls’ love therein. I do realise that queer is a complicated word today, but I hope the phrase ‘love sincere’ dispels any doubts regarding which side of the fence my sympathies sit regarding the matter.

The word ‘art’ ties into the idea of magic and fantasy as magic, like alchemy, was considered a branch of learning historically, and thus described in the same way we would talk about liberal arts. Of course, Hushabye herself is an accomplished artist of the visual kind, making this another fairly straightforward piece of wordplay. ‘Enfold me in your art’ is just something that I ask of good narratives: I like being immersed in something if I sincerely enjoy it. This ties into the last line and my word choice therein.

Castle Hushabye is ‘a fonder home’ to the speaker of the poem, and it’s important to note the use of ‘fonder’ quite specifically. ‘Fonder’ is a comparative adjective, and when considered alongside the context of the speaker, who is evidently a traveller, it suggests that home or haven offered by Hushabye is a place that the speaker finder more loving (not merely lovely) than wherever the speaker originated from. Considering the state of the world today, I would happily escape into the good lady’s worlds and narratives and stay there.

While reading, I am reminded of one of Tennyson’s lyric interludes from The Princess:

The splendour falls on castle walls

And snowy summits old in story:

The long light shakes across the lakes,

And the wild cataract leaps in glory.

Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying,

Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.

O hark, O hear! how thin and clear,

And thinner, clearer, farther going!

O sweet and far from cliff and scar

The horns of Elfland faintly blowing!

Blow, let us hear the purple glens replying:

Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.

O love, they die in yon rich sky,

They faint on hill or field or river:

Our echoes roll from soul to soul,

And grow for ever and for ever.

Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying,

And answer, echoes, answer, dying, dying, dying.

Beauty and pathos mixed into one, much like the good lady’s tales. <3

===

Now to the more dry and technical parts of the piece. If you’ve no interest in the mechanics of poetry, feel free to head off. I promise I won’t mind.

I will admit, the poem was intended to be a far longer work when I first started work on it, but that was quickly whittled down when I decided it’d be an acrostic. Long poems are, in addition, generally not something that most people enjoy reading. As this was a poem intended to be read by the good lady herself, it had to be kept short.

The main thing I am genuinely unsatisfied with is the unusual rhyme scheme. It’s not irregular, per se, but rather it lacks a certain symmetry that I would have liked to have seen in a poem for someone whose work I sincerely enjoy.

The poem’s rhyme scheme follows thus (each letter representing a rhyme word):

a b b a c d d c || d e e d f f

The ‘d’ rhyme appears four times in the poem as opposed to the two times of every other rhyme, which is, from a poet’s perspective both incongruous and weird in a rather untidy way. Now, ideally, the rhyme scheme of the poem would have looked like this:

a b b a c d d c || e f f e g g

which would have been better as each quatrain is kept self-contained in terms of rhyme; or, alternatively:

a b b a b c c b || c d d c d d

would have been another acceptable alternative, slowly phasing through interlocking rhymes in a similar manner to Terza Rima or the Spenserian stanza.

An acrostic does pose a challenge poetically as, if I may put it this way, not all letters were created equal from a poetic stand-point. Different opening letters can create difficulties, whether it’s finding words with the correct rhythm or finding words that have a relevant meaning to the poem. Very frequently, the primary problem posed by an acrostic falls into one of three categories: words that begin with the correct letter but have absolutely nothing to do with the contents of the poem; words that fit perfectly into the poem but begin with the wrong letter; or words that have both the correctly letter and meaning but do not fit the rhythm.

This last point is actually the cause of a great deal of the metrical irregularity of the piece, with frequent trochees,– as seen in the first foot of lines 1, 7, 9, 11 and 12,– and more occasional spondees,– as found in the first foot of lines 3, 4, and 14,– beginning the lines of what should be predominantly iambic poem. Just a reminder for anyone who is less familiar with the poetic terminology, iambs, trochees, and spondees are metrical feet or stress patterns in poetry:

iamb: ˘ ¯ or unstressed-stressed (e.g. To be or not to be)

trochee: ¯ ˘ or stressed-unstressed

spondee: ¯ ¯ or stressed-stressed

In a short poem like this, one good skill to have is the ability to juggle the competing demands of metre and expression without being gagged by them. While one needs to express an idea within a confined space and obey the rules at the same time, one has to do things tastefully after all. An example of this would be in line 3:

¯ ¯ / ˘ ¯ / ˘ ¯ / ˘ ¯ / ˘ ¯

such things I ere had scarce partaken in.

While it does scan properly, it also falls rather awkwardly from a modern tongue due to the fairly archaic, but more flexible, syntax. Now if we were to expand it and rearrange the line into something more commonplace today, we can not only see how poetry condenses and re-patterns thought, but also how we ourselves have to ‘translate’ archaic poetry mentally to properly understand it.

Thus:

such things I ere had scarce partaken in

can be expanded to:

such things [that] I [before] had [rarely] [taken part] in

and can be further rearranged to make:

such things [that] I had [rarely] [taken part in] [before]

Moving onto structure: although I’ve split it into two stanzas, I would like to argue that the poem could and should be read, structurally, in three different ways: as an acrostic of two words, Hushabye and Valley; as an ode, with an unequal tripartite structure of strophe, antistrophe and epode; as a sonnet, with a false volta in line 9, and a true volta in line 13.

I need not go into the acrostic, I think, as it’s probably the most straightforward part of the poem. The ode is where the invocation to ‘Hushabye’ plays its part. Ode are explicitly poems that laud something or someone. In addition, the structure of the poem’s primary movements can be split into three, albeit unequal parts: the strophe, in which the speaker invokes ‘Hushabye’ and describes the initial wonder that he/she experiences; the antistrophe, directed instead to the ‘Valley’ itself, where the beauty that is lauded by the strophe is exchanged from more enduring qualities like ‘tenderness’ and comfort, ‘as suggested by the word ‘languid’. The epode is the sudden change from invocation to imperative as can be seen in the verbs ‘Enfold’ and ‘bid’.

As a sonnet, we have to read the poem as a single stanza. The rhyme scheme, however, supports this as it can neatly separate the poem into three quatrains and a couplet, the very same as many types of sonnet. From this perspective, the four lines beginning with ‘Valley’ instead belongs to the same continuum as ‘Hushabye’ and ‘A face…’, rather than being a distinct stanza of its own. This final way of looking at the poem, as a sonnet, is perhaps the only one which also offers a reason for the metrical shift in the final couplet. Rather than being in iambic pentameter, the two lines are actually alexandrines, i.e. iambic hexameter, with a caesura or break in the very middle of those lines, as can be clearly seen in:

‘Enfold me in your art, || and bid me never roam:’

The alexandrine is fairly unusual in English poetry but, when used in a predominantly pentametrical context, serves to slow the pace of the iambs and to create a falling motion, a perfect technique if one wanted to finish a poem in a manner that suggests as much affection as ease.

===

Long way to go, but if you’ve managed to get here, then you have my sincerest thanks and affection~

0 notes

Text

Ode to Hushabye Valley

Hushabye! I came upon this misty land

Unknowing of the splendours hid within:

Such things I ere had scarce partaken in

Here seem complete with beauty, mild and grand.

A face of marble greets me sweet and fair

Beneath the archways of a bygone year;

Yielding of joys that savour quaint and queer;

Embracing all with warmth beyond compare.

Valley of long-lost glories echoing near,

Amidst the kindly voices of a faerie race!

Loveliest is this strange and languid place,

Light with tales of tenderness and love sincere.

Enfold me in your art, and bid me never roam:

Yon castle walls have seemed to me a fonder home.

===

A fan-poem for @hushabyevalley

I know most people prefer receiving fanart, but all I have to give is my poetry. >.< I hope you like it!

(Also for anyone else reading this, please support the good lady on Tumblr or on Patreon. Thank you!)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

View of the Baltic – Notes

Reading more German poetry recently; more specifically the poetry of Theodor Storm.

Four stanzas using the fairly unusual rhyme scheme of A B A A B. Predominantly, but not wholly, uniform iambic pentameter. I would hesitate to associate this poem too strongly with the Romantic tradition, despite the subject matter, as the poem lacks that inward contemplation that is the signature of the Wordsworthian strain of literary Romanticism. Both the Victorian Romantic lyric poetry, embodied in Matthew Arnold, or the late Augustan lyric, found in its most mature form in Thomas Gray, are closer in spirit and temperament to the poem above,– at least in my opinion.

Long vowel sounds are best vowel sounds, by the way. To clarify somewhat: long vowel sounds have a very strong impact on pace and rhythm, serving to stretch the metrical feet while also evening out the stresses. The combination is both temporal and aural expansion (whereas unstressed beats and sharp consonants can lead to compression instead). ‘O’s and certain ‘a’ sounds tend to be the longest in the English language. ‘I’ and select ‘e’ sounds rank amongst the shortest. For something that describes a scene that is characterised by regularity and immutability, long vowels become highly useful in forcing the ear to linger on every word that’s spoken, and can aurally act out the changeless regularity of the scene depicted.

Repetition is another technique that I have a great deal of affection for, and it’s due to the potential for logical inversion or thematic variation that intrinsic to the technique. By repeating something, one emphasizes the similarity,– or difference,– of content or context between the repeated instances. It’s a beautiful way of emphasising an idea or an image while also creating a sort of logos, if we were to use Aristotelian terms. Why logos rather than pathos? Well, I would argue that repetition holds an appeal that is not intrinsically emotional. Mere repetition, at least I think, cannot generate an immediate emotional response. However, the variation, similarity, or inversion that repetition emphasises is itself intellectually satisfying or stimulating. Not to say that a repeated line can’t generate emotional pathos, but I would argue that this is based on content that’s being repeated rather than the technique of repetition itself.

Finally, if we were to speak of syntax and structure in the poem above, the one thing to notice is how varied the phrases are in length, and what that variation achieves. This is an enjambment-heavy poem, with the longest phrases occurring in the middle two stanzas. The first and last, in contrast, each feature very short phrases: to describe the movement of the waves in the first; to lead the narrative eye from the distant mounts all the way to where the dawn breaks through the cloudy sky. The key here is movement. The wave is the only thing moving in the scene, and the sudden dynamic shift in the narrative eye from the mound to the sky is the only major movement in terms of focus in the entire poem. We’ve spoken of vowels acting out the content of the poem. It’s no surprise that syntax,– supported by punctuation,– can do much the same.

0 notes

Text

Hear It Now: 1940 – Notes

I was listening to some of the old radio broadcasts when I got it into my head to rewrite and montage them into a poem. Most of these were the wartime broadcasts of Edward R. Murrow during his time in London Blitz.

Hm...

Not much to say really,– a combination of immediacy and distance underlies the dual action of event and emotion, with the radio providing a contextual conduit. Although everything happens in real-time on live radio, the physical distance is something that nonetheless contributes to a sense of detachment that pervades the poem despite the horror of the action. As Orwell suggests through his narrative in Homage to Catalonia, distance makes action seem unreal, or inconsequential. Sniping at other human beings far away in trenches become potshots at ants, and the machine-guns of an aeroplane high in the sky become the flutter of wings.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Geronzio di Padova – Notes

The principal inspiration for the poem are T.S. Eliot’s Gerontion; Dante’s Divine Comedy (more specifically segments of Inferno; the latter half of Purgatorio and the final canto of Paradiso); and a number of Tennyson’s late poems. Epigram is a snippet of conversation between Vladimir and Estragon from Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

The decision to use this epigram was because it most echoed the spirit of the speaker to me,– Vladimir and Estragon are trapped, essentially, by their desire to wait for Godot. Why they are waiting for Godot is unknown, but all that they do within the confines of the play amount to various attempts to kill time and fill the void that idleness has left them in until such time that Godot arrives. The speaker of the poem exists in a similar state, awaiting death, but stuck in the impotent limbo of old age, where all that he would like to experience is forever beyond his grasp. All that he has left to do is to paint and think and pass the days in frustration until such time that death should take him away.

The mode of the poem is where T.S. Eliot’s influence can be most seen. The Modernist dramatic monologue, in contrast to the highly focused Victorian dramatic monologue as formulated by Browning and Tennyson, is consumed by the aesthetic of literary montage, wherein the use of free verse, allusion, fragmentation, etc. are used to enrich the narrative or spoken voice of the poem while simultaneously overwhelming the reader-listener with the resulting linguistic panoply.

The nine stanzas of this poem are intended to, firstly, mimic the nine circles of hell that Dante traverses in Inferno, and to suggest that the speaker is currently experiencing his own proverbial hell in the poem, namely being trapped in the state of old age. The girl who he sees, by contrast, represents everything that he cannot have or has lost,– vigour, innocence, youth, and beauty,– and can only imagine by being in the grip of intense memory or else by lusting for this girl despite his physical frailty and impotence (suggested by the language of drought and being ‘unseasonable’). Of the damned though, he is one who is keenly aware of his suffering, but also too proud to suffer the pity of others, hence why his inner monologue is dominated by powerful yet self-destructive impulses (self-hatred, frustrated lust, denial, self-isolation, scorn for others, etc.). The most he can do is look forward to the moment he will cease to be, and dream the nights of all that he would but can no longer have,– something with most tellingly culminates in the image of the ‘sun amidst the stars’ which echoes Dante directly, who describes God’s eternal radiance, beauty and compassion in such a manner.

0 notes

Text

Sehnsucht – Notes

Et, voilà! An artifice which I pray may placate the poetic palate, if I may be so bold as to hope.

The poem is separated into four quintains,– that is to say in plainer speech, stanzas of five lines,– and follow the following rhyme scheme: abbaa

Structurally, however, the stanzas prove far more arbitrary,- enjambment occurs frequently, cutting syntactic lines across stanzas and lines, and creating a profound tension between sense and meter due to the unexpected fall of the caesura or pause.

Similarly, the assonance and internal rhyme,– observe how the phrase ‘consuming me’ seems more like the end rhyme of the second line than the word ‘weal’ due to the natural desire to close the couplet opened by ‘in fee’,– also serve to cut the across the rhyme scheme to create a kind of counter-metre and scheme to what the poem seems to present.

Regarding the language, I must confess I have a preference for archaisms;– however, considering the sense of age and long-nurtured loss that pervades the poem, I would like to say that archaisms are not in-apropos, as it were. When I speak of archaisms, I would like to suggest that archaisms also include the use of words in ways or meanings that have ceased to be commonplace. The words ‘weeds’ is a prime example.

The title and theme are broadly speaking the very same: Sehnsucht, which unfortunately has no equivalent word in English. An emotional state of longing, yearning or the sense of something profoundly missing, Sehnsucht has a deeper connection with things that are desired but unattainable. Indeed, I would like to stress that the following idea is the most important thing to bear in mind when attempting to understand the poem’s theme: a sense of profound longing for the unattainable.

It is a sense,– the merest ghost of a sensation,– of a profound longing that lingers on the heart. Just as a piece by Debussy or a painting of Monet is as much an impression of the thing rather than a thing itself,– a relationship directly underline by Magritte’s famous Pipe,– the poetic artifice is merely an impression of a longing for the unattainable or the unanswerable.

I would like to suggest, however, that an impression of a thing is by no means a lesser object than the thing itself. Here, what becomes of greatest interest is the form of the impression: which elements are felt most keenly in the impression, and which are excluded or diminished?– how are these elements made prominent by the artist?– how does the emotional distance afforded by the impression of the thing affect one’s subjective experience of that same thing? The art of impression,– or the shadow play of Plato’s cave,– is as legitimate as the art of the real.

0 notes

Text

View of the Baltic

The waves draw up the low and level strand:

long echoes roll and roar, recede, return

from out this ghostly misted hinterland

of copses thin, and rooted in the sand,

and solitude that deepens turn by turn.

All is still that yet breathes upon the mound,

and all that glori’d once now lies beneath;

to slumber nameless in the nameless ground

in this unknown retreat of half-heard sound,

and trackless sand, and all-forgotten heath.

Who was it first that clomb this grassless height

and look’d upon that changeless Baltic shore

in gladness; or strode down the yawning bight

when daylight yielded to the starless night,

and knew all was well, then and fore’er more?

No answer comes to greet the wandering soul;

no birdsong marks the coming of the day.

Upon the mounts, adown the barren knoll,

across the vacant strand, and past the shoal

the dawn gleams out from skies of utmost grey.

2 notes

·

View notes