Articles, Interviews, Essays and Videos on Latin American Art

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Acts of Decontextualising Again: On the Risks of Auto-Exoticism in “O Quilombismo” at House of World Cultures

Katerina Valdivia Bruch

What do the Dalit in India have in common with indigenous art from the Amazonas region in Perú, the Mapuche from Chile or the Afro-communities in Brazil? Resistance, resistance, resistance.

The exhibition “O Quilombismo” takes as a basis a book by Brazilian artist, scholar and politician Abdias do Nascimento, who wrote “O quilombismo: Documentos de uma militância Pan-Africanista” in 1980, while he was living in exile in the US. The notion encompasses the idea of a group of people, who escaped from slavery, establishing communities of “fraternal and free reunion, or encounter; solidarity, living together, and existential communion.”

In Berlin, under the term “Quilombismo” the exhibition presented works that refer to the Dalit, indigenous groups from the Amazonas region in Perú and the Mapuche in Chile, as if all have to do with the same cause. While the caste system existed before the British colony (ca. 1500 BC), the “quilombos” were communities created by Afro-Brazilians, who escaped from slavery in the sixteenth century. Another example of decontextualisation happens with the inclusion of art by popular artists from the Amazonas region (the shipibo-conibo community from Pucallpa). These and other indigenous groups suffered from the consequences of the rubber boom extractivism in the Amazon basin (ca. 1870-1920). Although they officially were not slaves, they were treated as such. The exhibition puts everything in the same basket, without differentiating the importance and the meaning of each one of these struggles.

The display resembles a traditional folk craft fair, with batik textiles hanging from the ceiling, traditional “arte popular” (popular art) pottery displayed on a half-moon base structure with two levels, or hand-woven textiles attached on the walls. Although the exhibition offers a supposed “pluriverse,” for me it presents a closed circuit, in which minorities are presented as the idealised exotic other. The artists are reduced to their identity, although identities are newer static. They are always in constant transformation. The opening ceremony included a Voodoo ritual, convened by the Voodoo priest Jean-Daniel Lafontant from Haití. While this ritual might have had a transformative power in its original context; in Berlin after two or three beers and some selfies with friends (with the ritual in the background), Berliners would have probably forgotten about it.

“We are coming in peace,” said Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, the newly appointed director and chief curator of House of World Cultures (Haus der Kulturen der Welt, HKW for its German acronym) during his opening speech. Although he has been active in the art scene for several years, his phrase appeared as if he and his team were arriving from a spaceship and landing at HKW to conquer the art scene with their “new” vision of the arts. However, his view of the arts is not new at all, as it is based on theories developed long time ago.

Beyond Abdias do Nascimento, throughout the 1970s and 1980s several Latin American art theorists discussed the importance of focusing on local contexts, which included reflecting on the local popular cultures with an anti-colonial and anti-imperialist tenor. Influenced by the theory of dependency, a group of Latin American theorists gathered in different international meetings and reflected on the creation of a social theory of art from a Latin Americanist perspective. Among them were Mirko Lauer, Juan Acha, Rita Eder, Aracy Amaral, Damián Bayón or Marta Traba. Although the discussions around “arte popular” (local popular art) were not exempt from contradictions, there were attempts to present popular art within contemporary exhibition settings. For instance, the first three editions of the Bienal de la Habana (1984, 1986 and 1989). Knowing this, I wonder why the curators at HKW did not invest more time in researching this Latin Americanist perspective, and present works that would be in tune with the localist and anti-colonial tendency of the arts of that time.

Today, it is common in the art world to decontextualise, in order to present the past from a “new” and “different” perspective. In this show, instead of going deeper into what “Quilombismo” means, the exhibition mixes completely unrelated topics in the same show. Additionally, one needs to check the reader all the time to find out about the works and the artists. Instead of learning and understanding, I came out of the exhibition with a huge question mark, thinking of what it was all about.

Although the art world is currently working hard on being “inclusive,” the fact is that we are experiencing censorship in the arts. This is exemplified in the constant exposure of the work by Ukrainian artists and Ukrainian flags waving on top of important museums; while Russian artists are not exhibited (since the current war in Ukraine, everything coming from Russia is considered as evil). While Berlin praises itself for being open to people from different cultural backgrounds, a week ago I witnessed a disappointing situation. On a rooftop terrace close to Berlin Zoo, two Muslim men were sitting in silence doing their afternoon prayer. After a few minutes, a waiter from the nearby bar came out and asked them to stop praying and leave the terrace. While the two men were not disturbing anyone, I wonder whose inclusion we are discussing.

In times of Chat GPT and AI, in the art world it is all about “our ancestors.” And yet, whose ancestors are we talking about? Did the ancestors do things better? Was there a paradise in the past that we need to recover? Paradoxically, the ancestors invented patriarchy and the caste system. Instead of putting people into boxes, defining them by their identity, and decontextualising the history of past social struggles, one shall think about what we have in common as human beings; collaborate despite our differences, and reflect on possibilities on how to do things better than our ancestors.

Image: Installation view of “O Quilombismo” at HKW. Photo: Katerina Valdivia Bruch

0 notes

Photo

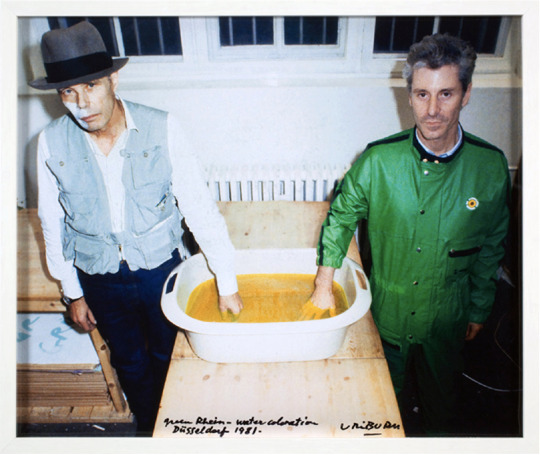

Although things have been changing in the last years, history of art has generally been written from a European or U.S.-American perspective. This situation has led to understand other art histories as derivative from the Euro-American canon. But, what happens if a European artist has been appropriating ideas from artists from other non-European latitudes? In her essay “La rivoluzione siamo noi: Latin American Artists in Critical Dialogue with Joseph Beuys, Katarzyna Cytlak” explores this topic, focusing on works by Joseph Beuys and his experience in Latin America. Beuys, considered one of the most famous German artists, has been celebrated for his “ecological works.” However, some of these ideas did not stem from his imagination, but were influenced by the ones of his Argentine peers, notably the works by Nicolás García Uriburu and Víctor Grippo.

As Katarzyna Cytlak noted:

“In the last years of his life, Joseph Beuys became interested in Latin American art as he reinforced his discourse on ecology. His collaboration with Nicolás García Uriburu reproduces the schema of the colonial power relationship, as the Argentinian artist is never officially mentioned in documentations of their actions. Beuys’s works from the mid 1980s, shortly before his death in 1986, could be described as derivative of Víctor Grippo’s and García Uriburu’s artworks.”

This essay not only shows that history needs to be rewritten. It also sheds light on the simultaneity of artistic explorations that were taking place in different parts of the world. To contrast the idea of derivative art, the works examined in this text indicate that Latin American artists had their own explorations, without having to adhere to what was coming from other latitudes.

*

Aunque las cosas han ido cambiando en los últimos años, la historia del arte se ha escrito generalmente desde una perspectiva europea o estadounidense. Esta situación ha llevado a entender otras historias del arte como derivadas del canon euro-americano. Sin embargo, ¿qué es lo que sucedería si un artista europeo se apropiara de las ideas de artistas de otras latitudes, no europeas? En su ensayo “La rivoluzione siamo noi: Latin American Artists in Critical Dialogue with Joseph Beuys” (La rivoluzione siamo noi: Artistas latinoamericanos en diálogo crítico con Joseph Beuys), Katarzyna Cytlak analiza este tema, centrándose en las obras de Joseph Beuys y su experiencia en América Latina. Beuys, considerado uno de los artistas alemanes más famosos, ha sido celebrado por sus “obras ecológicas”. No obstante, algunas de estas ideas no surgieron de su imaginación, sino que fueron influenciadas por la de sus pares argentinos, entre las que destacan las obras de Nicolás García Uriburu y Víctor Grippo.

Como se��ala Katarzyna Cytlak:

“En los últimos años de su vida, Joseph Beuys se interesó por el arte latinoamericano al reforzar su discurso sobre la ecología. Su colaboración con Nicolás García Uriburu reproduce el esquema de la relación de poder colonial, ya que el artista argentino nunca fue mencionado oficialmente en las documentaciones de sus acciones. Las obras de Beuys de mediados de la década de 1980, poco antes de su muerte en 1986, podrían describirse como derivadas de las obras de Víctor Grippo y García Uriburu”.

Este ensayo no sólo muestra que es necesario reescribir la historia. También arroja luz sobre la simultaneidad de exploraciones artísticas que se dieron en distintas partes del mundo. Para contrastar la idea de arte derivado, las obras discutidas en este texto muestran que varixs artistas latinoamericanxs realizaron sus propias exploraciones, sin tener que adherirse a lo que venía de otras latitudes.

Katarzyna Cytlak, “La rivoluzione siamo noi: Latin American Artists in Critical Dialogue with Joseph Beuys,” Third Text, vol. 30, n° 5–6, (2016): 346-367.

Click here to read the full essay / Clica aquí para leer el ensayo completo

Photo: Nicolás García Uriburu and Joseph Beuys, “Colouration of the Rhine,” 1981, colour photograph, 9 x 13 cm, private collection, Buenos Aires. Photo credit: Henrique Faria Gallery, New York and Buenos Aires.

#rethinkingconceptualism#rewrite#art history#conceptualart#conceptualism#joseph beuys#NicolásGarcíaUriburu#VíctorGrippo#KatarzynaCytlak

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Víctor Vich, one of the speakers of the symposium “Rethinking Conceptualism,” held last year, has contributed to LA ESCUELA with the essay New Pedagogies: Art Practices and Citizen Activism in Peru on three civil initiatives, that suggest “new ways of approaching history, our relationship with heritage, and linguistic diversity.” These examples of civic activism show how much one can learn from schools working with art collectives that are encouraging new ways to address pedagogy.

*

Víctor Vich, uno de los ponentes del simposio “Repensando el conceptualismo”, que tuvo lugar el año pasado, ha escrito el ensayo Nuevas pedagogías: prácticas del arte y del activismo ciudadano en el Perú para la LA ESCUELA. El artículo trata sobre tres iniciativas civiles, que sugieren “nuevas formas de abordar la historia, nuestra relación con el patrimonio y la diversidad lingüística.” Estos ejemplos de activismo civil muestran lo mucho que se puede aprender del trabajo entre colectivos escolares y artísticos, que proponen nuevas formas de abordar la pedagogía.

Foto: Proyecto Intangible: Acción N° 12 (2019). Espiral humano formado con 160 escolares de la IE 81526, centro poblado Santo Domingo, Perú. Cortesía: José Carlos Orrillo.

0 notes

Text

Argentine philosopher, sociologist and feminist activist María Lugones (1944-2020) was part of the coloniality/modernity group, who contributed to the theories on the decoloniality of gender. She claims that the category of gender is a colonial imposition, which erased the variety of gender conceptions that existed before colonisation.

Lugones introduced the concept of "coloniality of gender", extending Aníbal Quijano's notion of "coloniality of power". She sees a limitation in Quijano's theory for considering gender as hegemonic, patriarchal and heterosexual and for accepting a capitalist, Eurocentric and global understanding of gender, which does not take into account how non-white colonised women were subordinated and disempowered. With her intersectional approach, she broadens the feminist discourse, historically dominated by white women. Furthermore, she understands knowledge as something produced by communities, not just individuals, which means that we all learn from and about each other.

In this link you can download the essay "Coloniality and Gender" (in Spanish language), Tabula Rasa, No. 9, (July-December 2008): 73-101.

*

La filósofa, socióloga y activista feminista argentina María Lugones (1944-2020) formó parte del grupo colonialidad/modernidad, contribuyendo principalmente a las teorías sobre la descolonialidad del género. La teórica afirma que la categoría de género es una imposición colonial, que borró la variedad de concepciones de género que existían antes de la colonización.

Lugones introdujo el concepto de "colonialidad del género", ampliando la noción "colonialidad del poder" de Aníbal Quijano. Ve una limitación en la teoría de Quijano por considerar el género como hegemónico, patriarcal y heterosexual y por aceptar una comprensión capitalista, eurocéntrica y global del género, que no tiene en cuenta cómo las mujeres colonizadas no-blancas fueron subordinadas y deprovistas de poder. Con su enfoque interseccional, amplía el discurso feminista, históricamente dominado por las mujeres blancas. Además, entiende el conocimiento como algo producido por las comunidades, no sólo por los individuos, y todxs aprenderemos de y sobre lxs demás.

En este enlace pueden descargar el ensayo "Colonialidad y género", Tabula Rasa, Núm. 9, (julio-diciembre 2008): 73-101.

#rethinkingconceptualism#MariaLugones#decolonialityofgender#LatinAmericanWomenTheorists#gender#intersectional feminism#blog

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The cultural magazine Amauta was founded and directed by Peruvian writer, journalist and politician José Carlos Mariátegui. The magazine collected contributions from intellectuals of the Peruvian avant-garde of the time and was responsible for disseminating the indigenist movement. It also introduced in Peru the Latin American avant-garde, as well as different European currents of thought and artistic movements of the time (psychoanalysis, surrealism, cubism, futurism or the new Russian narrative). 32 issues were published in its four years of existence (1926-1930) and it was distributed both nationally and internationally.

Among its local collaborators were Peruvian intellectuals and artists from different regions of the country, such as the indigenists: the artist José Sabogal and Julia Condesido (Lima), the historian and anthropologist Luis Eduardo Valcárcel (Cusco), the poets Alejandro Peralta (Puno) and César Atahualpa Rodríguez (Arequipa), and the writer and poet Enrique López Albújar (Piura). In addition, the politician Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (La Libertad), founder of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA), collaborated from exile. Among his international contributors were Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Jorge Luis Borges, Miguel de Unamuno, André Breton and Diego Rivera.

Peruvian art historian Natalia Majluf co-curated with Beverly Adams (Blanton Museum of Art) the exhibition The Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s, which was presented at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS) (February 27-May 27, 2019) in Madrid, with stations at the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) (June 21-September 22, 2019) and the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin (February 16-August 30, 2020). The press release of MNCARS highlights the following:

“The project questions the binary oppositions between nationalism and internationalism, localism and cosmopolitanism, criollismo and indigenismo, or tradition and modernity that have so far organised the discussion on this period. The magazine reflects a less dogmatic and polarized reality. (…)

In the same way, even today the group of indigenist painters led by José Sabogal is seen from the perspective imposed by the modernists of the 1930s and 1940s, who labeled these artists as traditionalists, excluding them from their particular historical narrative of modernity. The exhibition not only recovers indigenism to the field of the avant-garde, but – more broadly – it applies Amauta’s pluralistic gaze to rethink Latin American art of this period.”

The José Carlos Mariátegui Archive has digitised the magazine, that you can download here >>

*

La revista cultural Amauta fue fundada y dirigida por el escritor, periodista y político peruano José Carlos Mariátegui. La revista recogió contribuciones de intelectuales de la vanguardia peruana de aquel entonces y se encargó de difundir el movimiento indigenista. Asimismo, introdujo en el Perú el pensamiento de vanguardia en Latinoamérica, así como distintas corrientes de pensamiento y movimientos artísticos europeos del momento (el psicoanálisis, el surrealismo, el cubismo, el futurismo o la nueva narrativa rusa). En sus cuatro años de existencia (1926-1930) se publicaron 32 ejemplares y tuvo una distribución tanto nacional como internacional.

Entre sus colaboradores locales destacan intelectuales y artistas peruanxs provenientes de distintas regiones del país, tales como lxs indigenistas: el artista José Sabogal y Julia Condesido (Lima), el historiador y antropólogo Luis Eduardo Valcárcel (Cusco), los poetas Alejandro Peralta (Puno) y César Atahualpa Rodríguez (Arequipa), y el escritor y poeta Enrique López Albújar (Piura). Además, colaboró desde el exilio el político Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (La Libertad), fundador de la Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA). Entre sus colaboradores internacionales se encuentran Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Jorge Luis Borges, Miguel de Unamuno, André Breton y Diego Rivera.

La historiadora del arte peruana Natalia Majluf co-curó con Beverly Adams (Blanton Museum of Art) la exposición Redes de vanguardia. Amauta y América Latina, 1926-1930, que fue presentada en el Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS) (27 de febrero al 27 de mayo de 2019) en Madrid, con estaciones en el Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) (21 de junio al 22 de septiembre de 2019) y el Blanton Museum of Art de la Universidad de Texas en Austin (16 de febrero al 30 de agosto de 2020). El dossier de prensa del MNCARS destaca lo siguiente:

“El proyecto cuestiona las oposiciones binarias entre nacionalismo e internacionalismo, localismo y cosmopolitismo, criollismo e indigenismo, o tradición y modernidad que han organizado hasta ahora la discusión sobre el período. La revista refleja una realidad menos dogmática y polarizada. (…)

De la misma forma, todavía hoy el grupo de pintores indigenistas liderado por José Sabogal es visto desde la perspectiva que impusieron los modernistas de los años treinta y cuarenta, quienes calificaron a estos artistas como tradicionalistas, excluyéndolos de su particular narrativa histórica de la modernidad. La exposición no sólo recupera el indigenismo para el campo de la vanguardia, sino que, de forma más amplia, aplica la mirada plural de Amauta para repensar el arte de América Latina de este período.”

El Archivo José Carlos Mariátegui ha digitalizado la revista, la cual pueden descargar aquí >>

Photo: Cover of the first edition of the magazine Amauta (septiembre de 1926), with an illustration by José Sabogal/Carátula de la primera edición de la revista Amauta (September 1926), con una ilustración de José Sabogal

#rethinkingconceptualism#latinamericanart#intellectualnetworks#amauta#JoseCarlosMariategui#BlantonMuseumofArt#MALI#MNCARS#NataliaMajluf#BeverlyAdams#avantgarde

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Hemispheric Institute of Performance & Politics was founded in 1998 by Diana Taylor, Professor at New York University. The institute “offers an anti-colonial model for engagement between ‘north’ and ‘south’ by promoting multi-sited, multilingual collaborations and acknowledging everyone as a potential producer of art and knowledge”, as it states on its website.

Moreover, the institute’s website hosts an impressive collection of documentation on performance and politics in the Americas, with archives with videos, interviews, dossiers and artists’ profiles. According to the web: “We also preserve performance practices and histories, making rare and valuable documentation available to a global audience.” It also publishes biannually the online journal e-misférica, that includes “academic essays, multimedia artist presentations, activist interventions, and translations, as well as book, performance, and film reviews.”

*

El Hemispheric Institute of Performance & Politics fue fundado en 1998 por Diana Taylor, profesora de la Universidad de Nueva York. Según la introducción en su página web, el instituto “ofrece un modelo anticolonial para el compromiso entre el ‘Norte’ y el ‘Sur’, promoviendo colaboraciones multisituadas y multilingües y reconociendo a todxs como potenciales productores de arte y conocimiento.”

Además, la página web del instituto alberga una impresionante colección de documentación sobre performance y política en las Américas, con archivos con videos, entrevistas, dossiers y perfiles de artistas. Según la web: “También preservamos las prácticas y las historias de la performance, poniendo a disposición de un público global documentación rara y valiosa.” Además, publica dos veces al año la revista en línea e-misférica, que incluye “ensayos académicos, presentaciones multimedia de artistas, intervenciones activistas y traducciones, así como reseñas de libros, performances y películas.”

Photo: Events by the Hemispheric Institute of Performace & Politics © Hemispheric Institute of Performance & Politics

#rethinkingconceptualism#LatinAmericanart#conceptualart#conceptualism#performance#performanceart#hemisphericinstitute

0 notes

Text

The magazine Plural was first released in October 1971. It was an initiative of the newspaper Excélsior and its managing director Julio Scherer. The magazine’s first period – and probably the best known – lasted until July 1976 under the editorship of Octavio Paz. During this time, Plural brought together intellectuals from both Latin America and other parts of the world, and was a cultural reference point for intellectual production.

It is also worth mentioning the importance of Kazuya Sakai, who collaborated with Paz from the very first issue, first translating an excerpt of “Essays in Idleness” by Japanese Buddhist monch and writer Yoshida Kenko and, from issue 2 onwards, he will be in charge of the design. In the beginning with Vicente Rojo, then on his own. The intellectual of Argentine-Japanese origin had various functions in the magazine: he translated oriental classics, wrote art criticism and worked as a visual artist. In issue 13 of October 1972, he was artistic director and editor-in-chief, a position he held until April 1976 (issue 55 of the magazine).

Among the contributors in the area of visual arts were Juan Acha, Damián Bayón, Jorge Alberto Manrique, Harold Rosenberg, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, José Luis Cuevas, Mathias Goeritz, Pablo Picasso, Vicente Rojo and Rufino Tamayo. Plural was published until December 1994.

*

En octubre de 1971 nace la revista Plural, una iniciativa del periódico Excélsior y de su director general Julio Scherer. La primera época de la revista – y quizá la más conocida – duró hasta julio de 1976, bajo la dirección de Octavio Paz. Durante esta etapa, la revista convocó a intelectuales, tanto de América Latina como de otras latitudes y fue un referente cultural de la producción intelectual.

Cabe señalar también la importancia de Kazuya Sakai, quien desde el primer número colaboró con Paz, primero traduciendo fragmentos de “El libro del ocio” del monje budista y escritor japonés Yoshida Kenko y, a partir del número 2, Sakai se hará cargo del diseño. En un primer momento con Vicente Rojo, luego en solitario. El intelectual de origen argentino-japonés tuvo varias funciones en la revista: tradujo clásicos orientales, realizó crítica de arte y trabajó como artista visual. En el número 13 de octubre de 1972 aparecerá como director artístico y jefe de redacción, cargo que desempeñará hasta abril de 1976 (número 55 de la revista).

Entre las y los colaboradores en el área de las artes visuales se encontraron, entre otros, Juan Acha, Damián Bayón, Jorge Alberto Manrique, Harold Rosenberg, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, José Luis Cuevas, Mathias Goeritz, Pablo Picasso, Vicente Rojo y Rufino Tamayo. La revista se publicó hasta diciembre de 1994.

Photo: Cover of the magazine Plural issue 42, March 1975, with an image by Kazuya Kasai | Carátula de la revista Plural número 42, marzo de 1975, con una imagen de Kazuya Kasai

#revistaPlural#OctavioPaz#KazuyaKasai#JuanAcha#DamiánBayón#VicenteRojo#rufinotamayo#rethinkingconceptualism

0 notes

Photo

The Reina Sofía Museum (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía) in Madrid is one of the museums with regular activities that exhibit, research and discuss different topics on Latin American art. The museum’s website has a number of resources that include interviews, videos, images, a radio show and publications. For instance, the fifth number of Carta(s) about the exhibition curated by Nelly Richard “Unfinished Timelines: Chile, First Laboratory of Neoliberalism”, that took place from 21 March to 24 May 2019. Following the web “The publication serves as a platform to establish a dialogue around memory and political struggle, taking the dictatorship and transition in Chile as an object of study and context in which the reflection will be located.”

You can download other issues of the publication Carta(s) here

*

El Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía en Madrid es uno de los museos con actividades regulares que muestran, investigan y discuten diferentes temas sobre arte latinoamericano. El sitio web del museo tiene una serie de recursos que incluyen entrevistas, videos, imágenes, un programa de radio y publicaciones. Por ejemplo, el quinto número de Carta(s) sobre la exposición curada por Nelly Richard “Tiempos incompletos. Chile, primer laboratorio neoliberal”, que tuvo lugar del 21 de marzo al 24 de mayo de 2019. Según la web: “La publicación sirve de plataforma para establecer un diálogo en torno a la memoria y la lucha política, tomando la dictadura y la transición en Chile como objeto de estudio y contexto en el que se ubicará la reflexión.”

Pueden descargar otras ediciones de la publicación Carta(s) aquí

Photo/Foto: Felipe Rivas San Martín, Bombardeo del Palacio de la Moneda, 11 de septiembre 1973. Fotografía intervenida con código QR, 2013

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The exhibition “Oscar Masotta. Theory as Action”, curated by Ana Longoni, in collaboration with Hiuwai Chu, Amanda de Garza and Guillermina Mongan, was presented at MUAC (Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo) in Mexico City, from 27 April to 20 August 2017, and at MACBA (Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona), from 23 March to 11 September 2018. According to the curatorial text: “This exhibition project, organized around different thematic nuclei, aims to reconstruct his complex intellectual and artistic career, emphasizing his crucial role as a driver of the Argentine avant-garde from the outset: the theoretical exercise as a mode of political action.”

You can download the catalogue of the exhibition here.

*

La exposición “Oscar Masotta. La teoría como acción”, curada por Ana Longoni, en colaboración con Hiuwai Chu, Amanda de Garza y Guillermina Mongan, se presentó en el MUAC (Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo) en Ciudad de México, del 27 de abril al 20 de agosto de 2017, y en el MACBA (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Barcelona), del 23 de marzo al 11 de septiembre de 2018. Según el texto curatorial: “Este proyecto expositivo, organizado a través de diferentes núcleos temáticos, se propone reponer su compleja trayectoria intelectual y artística, destacando su rol crucial como impulsor de la vanguardia argentina, a partir de su concepción: el ejercicio teórico como un modo de acción política.”

Pueden descargar el catálogo de la exposición aquí.

Photo: Installation view of the exhibition at MUAC | Vista de la instalación de la muestra en el MUAC.

0 notes

Photo

From 11-12 April 1995 took place the symposium “The Marco Polo Syndrome. Problems of Intercultural Communication in Art Theory and Curatorial Practice” at House of World Cultures (HKW). Gerhard Haupt, co-editor and co-director with Pat Binder of the online platform Universes in Universe, conceptualised the symposium and organised it in collaboration with Bernd M. Scherer (artistic director of HKW). Among the invited participants were Nelson Aguilar, Hans Belting, Carlos Capelán, Catherine David, Lorna Ferguson, Sebastián López, Jean-Hubert Martin, Valerie Smith and Gerardo Mosquera. The event included the publication of one issue of the magazine neue bildende Kunst (nr. 4/5, 1995) with the symposium papers and other essays related to the topic of the encounter. Gerardo Mosquera’s essay “The World of Differences: Notes about Art, Globalization, and Periphery” (in English and Spanish) is part of the publication, as well as the essay by Luis Camnitzer “The Corruption in the Arts/The Art of Corruption” (in Spanish and German).

Additional note: The title of the event was inspired by Gerardo Mosquera’s essay “The Marco Polo Syndrome: Some Problems around Art and Eurocentrism”, published in Third Text, vol. 6, 1992.

*

Del 11 al 12 de abril de 1995 tuvo lugar el simposio “El síndrome de Marco Polo. Problemas de la comunicación intercultural en la teoría del arte y la práctica curatorial” en la Casa de las Culturas del Mundo (HKW). Gerhard Haupt, co-editor y co-director con Pat Binder de la plataforma en línea Universes in Universe, conceptualizó el simposio y lo organizó en colaboración con Bernd M. Scherer (director artístico de la HKW). Entre los participantes invitados se encontraban Nelson Aguilar, Hans Belting, Carlos Capelán, Catherine David, Lorna Ferguson, Sebastián López, Jean-Hubert Martin, Valerie Smith y Gerardo Mosquera. El evento incluyó la publicación de un número de la revista neue bildende Kunst (nr. 4/5, 1995) con las ponencias del simposio y otros ensayos relacionados con el tema del encuentro. El ensayo de Gerardo Mosquera “El mundo de la diferencia. Notas sobre arte, globalización y periferia” (en inglés y español) de Gerardo Mosquera, así como el ensayo de Luis Camnitzer “La corrupción en el arte/El arte de la corrupción” (en español y alemán) forman parte de esta publicación.

Nota adicional: El título del evento se inspiró en el ensayo “The Marco Polo Syndrome: Some Problems around Art and Eurocentrism” de Gerardo Mosquera, publicado en Third Text, vol. 6, 1992.

Photo: Flavio Garciandía “El síndrome de Marco Polo”. Installation during the 2nd Havana Biennial, 1986 © Gerhard Haupt. Source: https://universes.art/en/

#Universes in Universe#Gerhard Haupt#Pat Binder#HKW#House of World Cultures#Bernd M. Scherer#Marco Polo Syndrome#Gerardo Mosquera#Luis Camnitzer

0 notes

Photo

Curator and art critic Gerardo Mosquera has dedicated several essays to questioning certain terminologies, for instance the terms ‘South’, ‘Latin America’ or the so-called ‘Latin American identity’, in order to revisit established cultural and artistic categories in a changing global art environment. In this regard, he co-authored with Nikos Papastergiadis the essay “The Geopolitics of Contemporary Art”:

“The broad aim of this essay is to provide an insight into some aspects of the function of art in a globalizing world. This is not to claim that art is now doing the work of politics but rather to see how art is a vital agent in the shaping of the public imaginary. We will address this problematic in three ways. It outlines the resistance to the politics of globalization in contemporary art; presents the construction of an alternative geography of the imagination; and reflects on art's capacity to be expressive of the widest possible sense of being in the world and of ‘being-on-the-globe’: a notion coextensive to that of Heidegger through which Manray Hsu has emphasized the effects of globalization. A worldview from the South disputes the validity of the centre-periphery model, and connects the critical insights generated by the debates on decolonial aesthesis with the widest possible sphere of cosmopolitan thinking. In short, our intention is to explore the worlds that artists make when they make art from the South.”

This essay was published in Platform 008 of the magazine Ibraaz, November 2014.

*

El curador y crítico de arte Gerardo Mosquera ha dedicado numerosos ensayos a cuestionar ciertas terminologías, por ejemplo los términos ‘Sur’, ‘América Latina’ o la llamada ‘identidad latinoamericana’, con el fin de revisar las categorías culturales y artísticas establecidas en un entorno artístico global en proceso de cambio. En este sentido, escribió con Nikos Papastergiadis el ensayo “The Geopolitics of Contemporary Art” (La geopolítica del arte contemporáneo):

“El objetivo general de este ensayo es proporcionar una visión de algunos aspectos de la función del arte en un mundo en vías de globalización. No se pretende que el arte haga ahora el trabajo de la política, sino ver cómo el arte es un agente vital en la formación del imaginario público. Abordaremos esta problemática de tres maneras. Se esboza la resistencia a la política de la globalización en el arte contemporáneo; se presenta la construcción de una geografía alternativa de la imaginación; y se reflexiona sobre la capacidad del arte para expresar el sentido más amplio posible de estar en el mundo y de ‘estar en el globo’: una noción coextensiva a la de Heidegger a través de la cual Manray Hsu ha puesto de relieve los efectos de la globalización. Una visión del mundo del Sur cuestiona la validez del modelo centro-periferia y conecta las ideas críticas generadas por los debates sobre la estética descolonial con la esfera más amplia posible del pensamiento cosmopolita. En resumen, nuestra intención es explorar los mundos que los artistas crean cuando hacen arte desde el Sur.”

Este ensayo fue publicado en Platform 008 de la revista Ibraaz, noviembre de 2014.

Photo: Carlos Capelán, “Relations of Power”, 2006. Courtesy the artist

#rethinkingconceptualism#GerardoMosquera#NikosPapastergiadis#contemporary art#South#LatinAmerica#GlobalSouth

0 notes

Photo

“Third Cinema: The Montreal Documents, 1974”. From 2-8 June 1974 took place the “Rencontres internationales pour un nouveau cinéma” in Montreal, Canada. Some of the most important representatives of militant cinema and Third Cinema from around the world participated in this meeting. Nowadays and given the sheer number and diverse backgrounds of the participants, the Montreal conference is considered as one of the most important events in political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s.

The list of more than 250 participants from 25 countries included filmmakers dedicated to political cinema, producers and ’68 film groups, film critics, historians and producers, members from film institutes and alternative distributors from Europe, Latin America, Africa and North America, as well as the Canadian organizers of the conference, André Pâquet and the Comité d’action cinématographique (CAC). One of the aims of this gathering was to forge and/or strengthen ties among politically committed cinema in the wake of the social changes that happened after 1968 in Europe and the emergence of Third Worldist filmmaking in Latin America, among other places.

The fourty-eight audiovisual recordings of the event remained unavailable until a few years ago. In 2012, film and cultural reseacher Mariano Mestman found these recordings in the archives of the Cinémathèque Québécoise. This footage gives record of the activities and discussions during the workshops that were around topics such as how films are shown, the participation of the people, Third World cinema or cinema as a tool for social change, among others. It also transmits very vividly some aspects of the discussions during the “Rencontres” in Montreal and allow us to reconstruct the climate and atmosphere of this intense political moment.

The documentation includes debates among Latin Americans, such as Miguel Littín (Chile), Julio García Espinosa (Cuba); Fernando Pino Solanas, Humberto Ríos and Edgardo Pallero (Argentina); and Walter Achugar (Uruguay); Africans, such as Med Hondo (Mauritania), Tahar Cheriaa and Férid Boughedir (Tunicia) and Lamine Merbah (Algeria); U.S. and European critics, for instance Guido Aristarco (Italy), Gary Crowds (US), Guy Hennebelle (France), Lino Micciché (Italy) or Jean Partick Lebel (France); Canadians filmmakers such as Fernand Dansereau, Gilles Groulx and Yvan Patry; as well as independent and political film distributors and groups like Slon/Iskra (I. Servolin, C. Marker, France), Tricontinental Film Center (R.Broullon and G.Lofredo, US), Mk2 (M. Karmitz, France), The Other Cinema (N.H.Williams, GB), Third World Newsreels (C. Choy and S. Robenson, US), Film Centrum (C. Svendstet/J. Lindqvist, Sweden), and many others.

Thanks to the collaboration of André Pâquet – organiser of the “Rencontres” in 1974 – and Jean Gagnon – current director of collections at the Cinémathèque – it was possible to do a digital transfer of the tapes, that are now available in DVD for public consultation in Montreal and Buenos Aires.

In 2013/2014, Mariano Mestman published his research and a DVD with three hours of audiovisual recordings in the publication “Estados Generales del Tercer Cine. Los documentos de Montreal, 1974” (in Spanish).

In 2015, the Cinématheque Québécoise published an online dossier with documents and video recordings of the “Rencontres” in Montreal (in French and English), as well as an edition for the Canadian Journal of Film Studies / Revue Canadienne d´Études Cinématographiques (V.24, N.2) dedicated to this meeting, edited by Mariano Mestman (Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires) and Masha Salazkina (Concordia University, Montreal).

Additionally, the Argentine Ministry of Culture presented two television programmes dedicated to the conference in Montreal, taking as a starting point political cinema from Latin America (in Spanish with English subtitles).

*

“Tercer cine: Los documentos de Montreal, 1974”. Del 2 al 8 de junio de 1974 se celebraron los “Rencontres internationales pour un nouveau cinéma” en Montreal, Canadá. En este encuentro participaron algunos de los más importantes representantes del cine militante y del Tercer Cine de todo el mundo. En la actualidad, y dado el gran número de participantes y la diversidad de disciplinas, la conferencia de Montreal se considera uno de los acontecimientos más importantes del cine político de los años sesenta y setenta.

En la lista de más de 250 participantes de 25 países figuraban cineastas dedicados al cine político, productores y grupos de cine del 68, críticos de cine, historiadores y productores, miembros de institutos cinematográficos y distribuidores alternativos de Europa, América Latina, África y América del Norte, así como los organizadores canadienses de la conferencia, André Pâquet y el Comité d'action cinématographique (CAC). Uno de los objetivos de este encuentro fue forjar y/o fortalecer los lazos entre el cine comprometido políticamente, a raíz de los cambios sociales que se produjeron después de 1968 en Europa, y el surgimiento del cine tercermundista en América Latina y en otras regiones del mundo.

Las 48 grabaciones audiovisuales del evento no estuvieron disponibles hasta hace un par de años. En 2012, el investigador de cine y cultura Mariano Mestman encontró estas grabaciones en los archivos de la Cinemateca de Quebec. Estas grabaciones registran las actividades y los debates de los talleres, que giraron en torno a temas como la presentación de películas, la participación del público, el cine del Tercer mundo o el cine como herramienta para el cambio social, entre otros. También transmite muy vivamente algunos aspectos de los debates durante los “Rencontres” de Montreal y permite reconstruir el clima y la atmósfera de este intenso momento político.

La documentación incluye debates entre latinoamericanos, tales como Miguel Littín (Chile), Julio García Espinosa (Cuba); Fernando Pino Solanas, Humberto Ríos y Edgardo Pallero (Argentina); y Walter Achugar (Uruguay); africanos, como Med Hondo (Mauritania), Tahar Cheriaa y Férid Boughedir (Túnez) y Lamine Merbah (Argelia); participantes de los EE.UU. y críticos europeos, como Guido Aristarco (Italia), Gary Crowds (EE.UU.), Guy Hennebelle (Francia), Lino Micciché (Italia) o Jean Partick Lebel (Francia); cineastas canadienses, tales como Fernand Dansereau, Gilles Groulx e Yvan Patry; así como distribuidores de cine independientes y políticos, y grupos como Slon/Iskra (I. Servolin, C. Marker, Francia), Tricontinental Film Center (R.Broullon y G.Lofredo, EE.UU.), Mk2 (M. Karmitz, Francia), The Other Cinema (N.H.Williams, GB), Third World Newsreels (C. Choy y S. Robenson, EE.UU.), Film Centrum (C. Svendstet/J. Lindqvist, Suecia), y muchos otros.

Gracias a la colaboración de André Pâquet - organizador de los “Rencontres” en 1974 - y Jean Gagnon - actual director de las colecciones de la Cinemateca - fue posible hacer una transferencia digital de las cintas, que ahora están disponibles en DVD para su consulta pública en Montreal y Buenos Aires.

En 2013/2014, Mariano Mestman publicó su investigación y un DVD con tres horas de grabaciones audiovisuales en la publicación “Estados Generales del Tercer Cine. Los documentos de Montreal, 1974” (en español).

En 2015, la Cinématheque Québécoise publicó un dossier en línea con documentos y grabaciones de vídeo de los “Rencontres” de Montreal (en francés e inglés) y una publicación para la Canadian Journal of Film Studies / Revue Canadienne d'Études Cinématographiques (V.24, N.2) sobre el encuentro, editada por Mariano Mestman (Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires) y Masha Salazkina (Universidad de Concordia, Montreal).

Además, el Ministerio de Cultura argentino presentó dos programas de televisión dedicados a la conferencia de Montreal, tomando como punto de partida el cine político en América Latina (en español con subtítulos en inglés).

Image: Poster of the “Rencontres internationals pour un nouveau cinéma” in Montreal. Graphic design: Noël Cormier

#rethinkingconceptualism#Mariano Mestman#Tercer Cine#Latin America#Rencontres internationals pour un nouveau cinéma#Cinématheque Québécoise

0 notes

Photo

We recommend to read the latest issue of the journal artelogie, entitled “Latin American Networks: Synchronicities, Contacts and Divergences” that includes some essays on networks of collaboration in the arts field in Latin America, as well as book reviews.

*

Recomendamos la lectura del último número de la revista artelogie, con el título “Latin American Networks: Synchronicities, Contacts and Divergences”, que incluye varios ensayos sobre las redes de intercambio artístico en América Latina, además de reseñas bibliográficas.

Photo: Julieta Hanono, Red de las poetas, 2019

0 notes

Photo

Juan Wilfredo Acha Valdivieso (1916 in Sullana, Peru - 1995 in Mexico City) was a chemical engineer and a self-taught art critic. He began writing about art in 1958 for the newspaper El Comercio, under the pseudonym of J. Nahuaca, composed of a wordplay with the letters of his real name.

Juan Acha was a keen supporter of the emerging artistic avant-garde during the late 1960s in Lima, and worked closely with the artists’ collectives Señal (1965-1966) and Arte Nuevo (1966-1968), among other artists. He was also one of the organisers of the “First Latin American Conference on Non-Objectual Art and Urban Art” at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín in 1981, where he would present his ideas regarding ‘non-objectualism’, a term that he would coin to describe the dematerialisation of the work of art.

In 2016, a series of events were held in Mexico City and Lima to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth (#Juan Acha100). As part of this tribute is the exhibition “Juan Acha. Revolutionary Awakening” at the MUAC (Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo), curated by Joaquín Barriendos, which takes as a starting point one of his publications that gives the exhibition its title. In his interview with curator Sol Henaro on the occasion of the exhibition, Barriendos will say: “It is important to understand the different facets of the theorist”, such as “social agitator, researcher and agent in dialogue with the young generation”.

The exhibition, based on the documents from the Archivo Juan Acha, analyses the connections between Lima and Mexico City, and the transition and fracture that the Peruvian art critic and theoretician experienced, when he decided to leave Peru to settle in Mexico City in 1972. From there, his theories will reach a Latin Americanist dimension.

*

Juan Wilfredo Acha Valdivieso (1916 en Sullana, Perú - 1995 en Ciudad de México) fue un ingeniero químico y crítico de arte autodidacta. Empezó a escribir sobre arte en 1958 para el periódico El Comercio, bajo el seudónimo de J. Nahuaca, compuesto por un juego de palabras con las letras de su verdadero nombre.

Juan Acha fue un entusiasta promotor de la vanguardia artística emergente a fines de los años sesenta en Lima, y trabajó estrechamente con los colectivos de artistas Señal (1965-1966) y Arte Nuevo (1966-1968), entre otros artistas. Asimismo, fue uno de los organizadores del “Primer Coloquio Latinoamericano de Arte No Objetual y Arte Urbano” en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín en 1981, donde presentará sus ideas sobre el ‘no-objetualismo’, término que acuñará para describir la desmaterialización de la obra de arte.

En 2016 se realizaron en Ciudad de México y en Lima una serie de eventos para conmemorar los cien años de su nacimiento (#Juan Acha100). En el marco de este homenaje se presentó la exposición “Juan Acha. Despertar Revolucionario” en el MUAC (Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo), curada por Joaquín Barriendos, que toma como punto de partida una de sus publicaciones que dará el título a la muestra. En su entrevista con la curadora Sol Henaro, con motivo de la muestra, Barriendos dirá: “Es importante entender las diferentes facetas del teórico”, tales como “agitador social, investigador y agente en diálogo con las juventudes”.

La exposición, realizada con los documentos provenientes del archivo Juan Acha, analiza las conexiones entre Lima y Ciudad de México, además de la transición y fractura que vivió el crítico de arte y teórico peruano, cuando decidió dejar el Perú para establecerse en Ciudad de México en 1972. Desde allí, sus teorías alcanzarán una dimensión latinoamericanista.

Photo: Juan Acha, © Archivo Mahia Biblos

0 notes

Photo

When does contemporary art begin? Art historian and curator Andrea Giunta follows this question in her book with the same name, in which she develops the notion of ‘simultaneous avant-gardes’ in the arts.

In her essay “¿Cuándo empieza el arte contemporáneo? Intervenciones desde América Latina” (When Does Contemporary Art Begin? Interventions from Latin America), she will say:

“When does contemporary art begin? The parameters are multiple. It begins, in a sense, when the idea of modern art is interrupted. Contemporary art is that which has stopped evolving (a precious idea in modern art). It is also the one that points to a significant deviation from the autonomy of language: the real world bursts into the world of the work, in which there is a violent penetration of the materials of life itself. The objects, the real bodies, the sweat, the fluids, the garbage, the sounds of everyday life, the remains of other worlds enter into the format of the work and exceed it. Much of this happened with Dadaism and Surrealism. However, its deepening and generalization occurred in the post-war period, mainly since the late 1950s. Such destabilization involves a critique of modernity that will deepen and take a visible, disruptive place within the postcolonial debate.”

The book “When Does Contemporary Art Begin?” was published in 2014 by Fundación arteBA in Spanish and English. You can download it here.

*

¿Cuándo empieza el arte contemporáneo? La historiadora y curadora de arte Andrea Giunta plantea esta pregunta en su libro homónimo, en el que desarrolla la noción de ‘vanguardias simultáneas’ en el arte.

En su ensayo “¿Cuándo empieza el arte contemporáneo? Intervenciones desde América Latina” dirá lo siguiente:

“¿Cuándo comienza el arte contemporáneo? Los parámetros son múltiples. Se inicia, en un sentido, cuando se interrumpe la idea de arte moderno. El arte contemporáneo es aquel que ha dejado de evolucionar (idea preciada en el arte moderno). Es, también, el que señala un desvío importante respecto de la autonomía del lenguaje: el mundo real irrumpe en el mundo de la obra, en el que se produce una violenta penetración de los materiales de la vida misma. Los objetos, los cuerpos reales, el sudor, los fluidos, la basura, los sonidos de la cotidianeidad, los restos de otros mundos ingresan en el formato de la obra y la exceden. Mucho de esto sucedió con el dadaísmo y el surrealismo. Sin embargo, su profundización y generalización se producen en el tiempo de la posguerra, principalmente desde fines de los años cincuenta. Tal desestabilidad involucra una crítica a la modernidad que se profundizará y tendrá un lugar visible, disruptivo con el debate poscolonial.”

El libro “¿Cuándo empieza el arte contemporáneo?” fue publicado en 2014 por la Fundación arteBA en 2014 en español e inglés. Pueden descargarlo aquí.

Image/Imagen: Kenneth Kemble, Muestra de Arte Destructivo en Galería Lirolay, 1961. Foto: Jorge Roiger. En Dixit. Courtesy/Cortesía: Cosmocosa/arteBA

#rethinkingconceptualism#Latin American art#When does contemporary art begin#Andrea Giunta#conceptualism in Latin American art

0 notes

Photo

In her article “Brazilian Modernism: Feminism in Disguise”, published in Frieze Masters, issue 7, 2018, with the title ‘Feminism in Disguise’, Claudia Calirman explains how women artists played a crucial role in the development of the arts in Brazil. During Brazil’s dictatorship (1964-1985), some of them created strategies to challenge both the repressive regime and the patriarchal structures.

According to Calirman:

“The 1960s saw an explosion of great women artists such as Lygia Clark, Anna Bella Geiger, Anna Maria Maiolino, Lygia Pape, Wanda Pimentel and Letícia Parente, among many others.

(…) many artists resisted being labelled as ‘feminists’ since it was perceived as limiting one’s artistic significance or, even worse, as being divisive and counterproductive. (…) Though many canonical works by leading female artists questioned assumptions around gender, their attempts to explore or respond to feminist issues were often disguised or hidden.”

Despite this, “they forged new ways of representing women’s subjectivities and – even if they did not label themselves feminists – conceived a particular form of feminism unique to their country at a critical historical juncture.”

*

En su artículo “Brazilian Modernism: Feminism in Disguise”, publicado en la revista Frieze Masters, n° 7, 2018, bajo el título ‘Feminism in Disguise’, Claudia Calirman explica cómo las mujeres artistas desempeñaron un papel importante en el desarrollo de las artes en Brasil. Durante la dictadura (1964-1985), algunas de ellas crearon estrategias que desafiaron el régimen represivo y las estructuras patriarcales.

Según Calirman:

“Durante los años sesenta hubo una explosión de grandes mujeres artistas, tales como Lygia Clark, Anna Bella Geiger, Anna Maria Maiolino, Lygia Pape, Wanda Pimentel y Letícia Parente, entre muchas otras.

(...) muchas artistas se resistieron a ser etiquetadas como ‘feministas’ ya que lo percibían como una limitación de la importancia artística de cada una o, peor aún, como algo divisivo y contraproducente. (…) A pesar de que muchas obras canónicas de destacadas mujeres artistas cuestionaban los supuestos en torno al género, sus intentos de explorar o responder a temas feministas a menudo fueron disfrazados u ocultados.”

Sin embargo, “forjaron nuevas formas de representar las subjetividades de las mujeres y – aunque no se autodenominaron feministas – concibieron una forma particular de feminismo única en su país, en el contexto de una coyuntura histórica crítica.”

Photo: Anna Maria Maiolino, “É o que Sobra” (What Is Left Over), from the series ‘Fotopoemação’ (Photopoemaction), 1974, digital print, 62 × 153 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan

#rethinkingconceptualism#Claudia Calirman#Brazilian women artists#Brazilian art#Brazilian modern art

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mail Art is based on ideas of openness, inclusion, network and community, with no commercial purpose. Its historical roots can be traced in the artistic expressions of dadaists, futurists and Fluxus artists. In Latin America, during the decades of 1960s-1980s, it was widely used by artists, who wanted to circulate their ideas without having to pass through censorship measures. One of its best known representatives is Uruguayan poet, performer and multimedia artist Clemente Padín (*1939 in Lascano). He was part of a network of mail and visual poetry artists around the world, who were engaged in similar projects.

Padín’s first experiences in the field of Mail Art were in the 1960s with the publication of the magazines “Los huevos del Plata” (1965-1969), “OVUM 10” (1965-1969) or “OVUM 2a época” (1972-1875), with what he would describe as creative postcards and visual poems. In 1974, he organised the first Latin American Mail Art exhibition at the Gallery U in Montevideo. From August 1977 to November 1979 he was imprisoned for his fake postal stamps that criticised the brutal repression during the military dictatorship in Uruguay.

In 2009, Red Conceptualismos del Sur in collaboration with the Museo Reina Sofía set up an archive of Clemente Padín’s artistic practice, in other to catalogue and preserve his oeuvre. The same year, this archive was granted on a loan basis to the Archivo General de la Universidad de la República (UdelaR) in Montevideo. In September 2020, Clemente Padín donated his archive to UdelaR. Today, the Clemente Padín archive is fully catalogued and open to public consultation. The historian Vania Markarian, who works at the Clemente Padín archive at UdelaR, has published “Los Huevos del Plata. Un desafío al campo intelectual uruguayo de fines de los sesenta” (pp.132-142), in “Recordar para pensar. Memoria para la democracia”, Heinrich Böll Foundation (2010).

*

El arte correo se basa en ideas de apertura, inclusión, redes y comunidad, sin fines comerciales. Sus raíces históricas se pueden rastrear en las expresiones artísticas de los dadaístas, futuristas y artistas Fluxus. En América Latina, durante las décadas de los sesenta a los ochenta, fue muy utilizado por aquellos artistas, que querían hacer circular sus ideas sin tener que pasar por la censura. Uno de sus más conocidos representantes es el poeta, performer y artista multimedia uruguayo Clemente Padín (*1939 en Lascano). Padín formó parte de una red internacional de artistas de arte correo y poesía visual alrededor del mundo, involucrados en proyectos similares.

Sus primeras experiencias en el campo del arte postal datan de la década de los sesenta con la publicación de las revistas “Los huevos del Plata” (1965-1969), “OVUM 10” (1965-1969) o “OVUM 2a época” (1972-1875), que él describiría como postales creativas y poemas visuales. En 1974 organizó la primera exposición de Arte Postal Latinoamericano en la Galería U en Montevideo. De agosto de 1977 a noviembre de 1979 fue encarcelado por sus falsos sellos postales, que criticaban la brutal represión durante la dictadura militar en Uruguay.

En 2009, la Red Conceptualismos del Sur, en colaboración con el Museo Reina Sofía, creó un archivo de su práctica artística para catalogar y preservar su obra. Ese mismo año, el archivo fue cedido en comodato al Archivo General de la Universidad de la República (UdelaR) en Montevideo. En septiembre de 2020, Clemente Padín donó su archivo a la UdelaR. Actualmente, el archivo de Clemente Padín ha sido totalmente catalogado y está abierto para su consulta pública. La historiadora Vania Markarian, que trabaja en el archivo Clemente Padín de la UdelaR, ha publicado “Los Huevos del Plata. Un desafío al campo intelectual uruguayo de fines de los sesenta” (pp.132-142), en “Recordar para pensar. Memoria para la democracia”, Fundación Heinrich Böll (2010).

Photo: “OVUM 2a época No. 1”, 14 sheets of different sizes , 30 x 21 cm, 1973

#rethinkingconceptualism#Clemente Padín#Museo Reina Sofía#Red Conceptualismos del Sur#Vania Markarian#mail art#UdelaR

2 notes

·

View notes