She/her | Ancient (35+ :) | 18+ ONLY! NSFW stuff secondjulia on Ao3 & YouTubemy fics on TumblrSandman art

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Joyeux Anniversaire Robespierre!

Ok ik I'm late but I have company law to deal with 🧎♀️🧎♀️🧎♀️

#I missed it but sharing anyway because this is nice & why not go all the way & wish Robespierre a happy birthday :)#This WAS supposed to be my Socially Acceptable Obsessions tumblr but I think that ship sailed a few months ago. Oh well#why tf can't I be into normal things#robespierre#other people's art#frev#french revolution

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the impending heat death of the internet, our library of alexandria, inches ever closer, here are some resources that will teach you everything you need to know about digital archiving.

Digital preservation is the only process that can and will preserve everything you love that (currently) only exists in the digital realm. It’s not 100% guaranteed to work, but let’s be real—your own painstakingly, personally, manually cultivated digital archive is all you’ll have left of the images, blogs, recipes, videos, fics, fanzines, games, servers, forums, articles, peer-reviewed scientific studies, “illegal” musicals and even the friends you found online, when the internet is completely gone.

And yes, you can trust me on this, because I've had to help family friends create a personal digital archive of their own. She chose to pay for archiving software in the end, but that's not important.

The basics of/anticipating potential roadblocks to adequate digital preservation:

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

What to expect from the quality of your digital archive in the future:

youtube

Also! Fun fact: you can download the files that make up your entire tumblr blog!

Any additional resources you have or know of would be greatly appreciated, so please don't hesitate to share them.

Please spread this post so that it finds the people who need it the most right now.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

ITS GREAT LAKES AWARENESS DAY!!!!!

On this excellent day, be aware that this is the largest group of freshwater lakes in the world, covering over 95,000 square miles and reaching depths of over a thousand feet. They are beautiful freshwater seas.

Also when you die in these lakes, the very cold, oxygen-poor conditions at the bottom preserves you perfectly for all eternity. You will not rot and nothing will eat you. You will exist for as long as the Great Lakes do. Many shipwrecks still have the crew on board. Be Aware.

41K notes

·

View notes

Text

Y’all remember that one scene from The Good Place? 😐

#oh I did need a little sandman after all the frev horror#sandman#dream of the endless#matthew the raven#other people's art

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharing space is nothing new. Sharing bathrooms is nothing new. The reactionary outrage is so manufactured.

55K notes

·

View notes

Text

I can never leave Tumblr because after years of sporadic therapy utterly failed to even approach the core of my problem some random tumblr user was like “I processed my trauma by writing a 10,000 word work of filthy fanfic erotica” and I was like “fuck it I’ve tried everything else” and now I’m 17 chapters and 20,000 words deep into an unpublishable work of obscenity and after careful literary analysis with one of the Beloved Mutuals I have come to some Terrible Revelations about my childhood and may now continue the process of Healing. Where else am I supposed to get this kind of experience. Who does this. Why are we like this. I’m never leaving. I love y’all.

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

I love this book except for its disdain for Camille.

I mean, I love Camille exactly because he's so confused and confusing and emotional and the portrait of him that has come down the ages feels so much more... human? real? messy? than the others*? It's like, there's Danton stoic and strong till the end and virtuous Robespierre and murderously angelic Saint-Just and... Camille, what are you doing? What are you... Get off the table, please... The— *hands over face* —lamppost thing again? Sweetie, what did you think was going to happen? Oh now you're poking that bear?

Having read more books now, I do see how authors can kind of choose how they shape their portraits of him — as a coward, a bumbling child, Danton's mouthpiece in the press — but it still bruises my heart a little to see his genuine human complexity crushed into a convenient character.

*It's not that I think the others were less human/real/messy, it that their portraits crafted by historians are like that.

Usually when an English speaker is getting into the history of the French Revolution and wants to go beyond Wikipedia, they stumble on The Twelve Who Ruled. It’s inevitable. Since 1941 it has been a staple of lecture halls and history aficionados alike.

For me it was one of the first things I read, many years ago, and it shaped, to some extent, how I approached the period. I read it again last year, expecting to see it differently. I didn’t. It’s an old book. But still, by the standards of 21st-century historiography, largely accurate.

So since it’s a book a lot of beginners encounter, and since I’ve had half a mind to review some of the dozens of books on the French Revolution I own, I thought it would be a good place to start.

I will be assessing this book (and all others I review) on a scale from 1 to 5 in eight categories:

Before we start, remember two things:

This is my review, which means it is, by definition, biased. I try to stay as neutral as possible, but no one is fully objective.

You should never take anything as fact. I research things. I enjoy researching things. I spend far too much time researching things. But I’m human, and that means I make mistakes. Challenge everything you read, including this.

Twelve Who Ruled: An In-depth Review

Historical Accuracy

For a book published in the 1940s, Twelve Who Ruled is remarkable in how much of it remains uncontested, especially given that archival access in France was impossible during the war. Using only the printed sources available to him, Palmer built a richly detailed narrative of Year II. He avoided major factual errors and did not indulge in the lurid exaggerations or mythologising that often plagued earlier accounts of the Revolution.

On the contrary, Palmer’s portraits of key figures and events have stood the test of time. His depiction of Robespierre, for example, was unmatched in its balance, nuance and restraint when the book was published. Subsequent scholarship has generally confirmed Palmer’s factual claims. Indeed, many of his interpretations have been validated by later evidence: for instance, he is one of the first to advance the argument that the Terror’s policies were reactive responses to severe crises, rather than a premeditated program of mass violence, and that Robespierre never exercised dictatorial authority.

Eighty years later, Twelve Who Ruled still holds up as a factually sound work. Far from perpetuating discredited myths, Palmer steered a middle course, avoiding both Thermidorian clichés about a “blood-mad” Committee and hagiographic Jacobin legends.

Historiographical Position

When situating The Twelve Who Ruled within the landscape of French Revolution historiography, it is important to remember that Palmer was writing in 1941, before most of the major scholarly camps had fully taken shape. His work does not fit neatly into the classic categories of Marxist, Revisionist, or post-Revisionist schools (1), though it engaged with and later influenced those debates.

Palmer’s approach was essentially a liberal narrative of the Revolution’s most turbulent phase. He focused on the pragmatic demands of governance during an existential crisis, rather than on class struggle or ideological abstraction. This already set him apart from the Marxist tradition. His attention remained squarely on the actions and dilemmas of the twelve men on the Committee of Public Safety, and on the political and military pressures that shaped their decisions.

He also diverged from what would later become the Revisionist school. While Palmer shared their scepticism of class determinism, he did not embrace their emphasis on ideology as the primary driver. His account treats the Terror less as a product of revolutionary rhetoric than as a contingent response to internal collapse and foreign invasion. He was wary of overly ideological explanations.

In short, The Twelve Who Ruled occupies a distinctive historiographical position. As the first serious monograph on the Committee of Public Safety, it predates the Cold War polarities that shaped later scholarship. In my opinion, Palmer might best be described as a pragmatic liberal historian of the French Revolution. He did not write in the Marxist tradition of Lefebvre or Soboul (though he admired Lefebvre enough to translate his work), nor did he share the iconoclastic edge of later revisionists like Cobban or Furet (2).

Use of Primary Sources

Writing during World War II from the United States, Palmer relied entirely on published primary sources available in America. These included a wide range of printed materials: the proceedings and debates of the National Convention, official documents and reports of the Committee of Public Safety, as well as memoirs, letters, and revolutionary newspapers.

This breadth of material allowed him to reconstruct the Committee’s decisions and actions almost day by day, giving his narrative credibility. Crucially, Palmer did not confine himself to Paris. Because he was interested in the representatives on mission and provincial enforcement of the Terror, he also consulted sources on events in Lyon, Alsace, and Brittany. For its time, the study had a notably wide geographic scope.

Even so, Palmer’s research was limited to what was in print. He lacked access to unpublished archives, local records, or police files that later historians would use to deepen the field of social history. His source base is political and governmental. It reflects the perspective of the revolutionary authorities, not that of ordinary people.

In short, Palmer worked almost entirely with documents written by the deputies and officials (all men) who “ruled.” As a result, the book pays less attention to marginal voices (3). The result is a body of sources broad in political scope, if limited in social depth.

Palmer’s use of sources is generally careful and even-handed. He provides context for the material he cites and avoids cherry-picking. His work relies on French-language sources, as expected for the subject (4). While not archive-based in the modern sense, the research was solid enough that the book’s factual foundation has remained largely intact even after eighy years of further research.

Methodological Rigor

The Twelve who Ruled is not overtly theoretical; its strength lies in a coherent narrative framework and a clear analytical focus. In an era when many academic historians were often abandoning narrative and turning to structural or conceptual models, Palmer resisted the trend. He showed that storytelling, when anchored in analysis, could still carry serious weight. He did not invoke grand theories (Marxist class theory, Tocquevillian social theory, etc.), nor did he fill the text with historiographical jargon. Instead, he focused on applying a steady interpretive lens to the events of 1793–1794.

The idea that the Revolution’s survival hinged on creating a unified, legitimate, and forceful authority during the crisis is the leitmotif of the book. Every chapter, whether addressing the war effort, economic controls, or factional purges, returns to this analytical core. In methodological terms, Palmer’s approach can be described as problem-driven narrative.He identifies the central issue (governing amid chaos) and examines how various factors (personalities, ideologies, circumstances) shaped the response attempted by the Committee of Public Safety. The result is a tightly focused analysis. Despite covering a tumultuous year, the reader always understands why events unfold as they do: because the revolutionaries were trying, with varying degrees of success and virtue, to resolve the Republic’s existential crisis.

In discussing key concepts such as “revolution,” “terror,” and “virtue,” Palmer adopts sensible, if traditional, definitions. He uses the term “Terror” in his title and narrative because it was (and remains) the conventional label for the period, but he is careful to unpack what it meant in practice. He does not treat “The Terror” as a monolithic or abstract force. Instead, he breaks it down into specific policies and events (the Law of Suspects, the Revolutionary Tribunal’s activities, pressure from the sans-culottes etc.) to show how violence was implemented pragmatically, not philosophically.

Notably, Palmer did not anachronistically impose the term “Reign of Terror” on everything, he knew that the term gained currency mainly after Robespierre’s fall. His narrative implies, in line with modern findings, that the revolutionary government itself did not treat “Terror” as a coherent policy slogan (5). Palmer’s treatment of terror as a concept is methodological. He presents it as an emergency government and analyses the mechanics and morality of state violence without becoming entangled in a semantic argument.

His treatment of “revolution” and “virtue” follows the same logic. He presents the Revolution as a struggle to preserve the Republic against its enemies, even at the cost of violating some of its founding principles. He regularly cites the ideals of liberty and equality, and the 1789 Constitution, not to celebrate them but to underline the irony of their suspension “until the peace.” The term “virtue” appears mainly in the context of revolutionary rhetoric, particularly Robespierre’s vision of republican virtue. Palmer does not deliver a philosophical essay on the term. He lets Robespierre and Saint-Just speak for themselves, then examines the consequences. His analysis makes it clear that he understands Jacobin virtue as a kind of austere civic morality, which he implicitly weighs against liberal values.

Methodologically, Palmer is rigorous and consistent. He poses an implicit question: how did twelve men govern a revolution in crisis?—and answers it through a chronological but analytical narrative. His framework is free of glaring contradictions. He weaves political, military, and economic history into a single, unified argument.

The clarity of Palmer’s conceptual handling is evident in how easily the argument can be distilled. Readers never wonder what Palmer thinks the Terror was. He sees it as a revolutionary dictatorship, a term he uses without apology. It was, in some respects, effective (securing military victory), in others, creative (experimenting with democratic forms and state control), and in many, morally troubling.

Narrative Style

This is a subjective category, but one of Palmer’s greatest strengths lies in his narrative style, which is both clear and engaging. Unlike some academic history books, Twelve Who Ruled reads almost like a story, albeit a richly documented one, of a dramatic year in French history. Palmer’s prose is accessible and relatively free of jargon. He was writing for an educated audience, but not exclusively for specialists, and this shows in the readability of the text.

The story is driven by the vivid personalities of the twelve Committee members and the high-stakes drama they lived through. At times, Palmer almost novelistically follows individual members into the provinces or captures the atmosphere in the Convention, which helps the reader visualise events. This blend of narrative colour and historical evidence keeps the text grounded.

That said, the book does not read like a novel throughout. Twelve Who Ruled is densely detailed, and Palmer does not simplify the complexity of Year II. Some sections, for example those on the organisation of war production or the Committee’s internal bureaucracy, are dry and require the reader to absorb a large amount of technical information. However, these are consistently interwoven with more dramatic material such as battles, trials, and political confrontations. The balance keeps the pacing steady across the text.

Palmer is particularly effective in his character sketches. Each of the twelve becomes memorable (Carnot the stern military organiser, Barère the silver-tongued pragmatist, Saint-Just the youthful ideologue etc.) without collapsing into cliché. These almost literary portraits make the reader more invested in the unfolding story.

Perhaps most striking is the absence of pretension in Palmer’s style.His prose has a classic literary quality: measured, erudite, but never self-important. Compared to many writers of historical research, Palmer’s style is disciplined. He doesn’t try to prove his intelligence with a flood of ornate language. He simply writes well.

Originality and Contribution

Upon publication, Twelve Who Ruled was an innovative and ground-breaking contribution to French Revolutionary studies. R. R. Palmer effectively pioneered the focused study of the Committee of Public Safety, a subject that, surprisingly, had never before been treated in a comprehensive monograph. In 1941, historiography on the French Revolution was rich in general narratives and class analyses of 1789 or the broader revolutionary period, but the intense year of the Terror and its governing body had received no sustained study. Palmer filled that gap brilliantly.

By focusing on the twelve men of the Committee and examining their rule as a collective, Palmer offered a new angle. Rather than writing a biography of Robespierre or a general history of the Revolution, he did something original: a group portrait of a revolutionary government in action. This approach yielded fresh insights by highlighting the role of less-famous figures like Billaud-Varene, Lindet, the two Prieur(s) or Saint-André in winning the war and running the country.

At the time, interpretations of the Terror tended to fall into polemical extremes, either apologetic or scathing. Palmer’s contribution was to demystify the Terror. He did not glorify it or denounce it in moral absolutes. He analysed it as a political and historical reality. That stance was unusual in 1941, especially for an American historian. His work managed to synthesise insights from competing schools: it acknowledged the Terror’s necessity in context, a point later taken up by leftist historians, while also recognising its moral and strategic failures, a view more often stressed by revisionists.

This balance gave the book lasting academic value. This synthesis gave the book a lasting academic impact, as it could be read profitably by people on different sides of the interpretive spectrum.

Authorial Bias and Political Agenda

Palmer’s personal values and context inevitably informed his work, yet Twelve Who Ruled is notably measured and fair-minded, without a heavy-handed political agenda. R. R. Palmer was a liberal-democratic American intellectual, and someone who valued the ideals of the Enlightenment and constitutional government. That perspective quietly shapes the book. Palmer clearly admires certain principles of 1789 and he often reminds the reader of what was lost when the Terror regime suspended civil liberties and elections. His sympathy for liberal democracy leads him to approach the Committee of Public Safety with a critical eye, especially regarding their use of coercion and violence. He does not defend the guillotine or the repression of dissent. On the contrary, he treats those as regrettable, if at times understandable, choices.

Crucially, Palmer’s liberalism does not reduce his book to a simple anti-revolutionary stance. If anything, there is a degree of admiration for the Committee’s sense of duty and purpose, even as he remains aware of the compromises they made. He describes the Committee’s rule as a “dictatorship,” but one born of necessity, reflecting a liberal’s reluctant concession that extreme times may call for extreme measures. His relief when the Terror ends is unmistakable. The tone around Thermidor suggests a welcome return to politics as usual, though he does not spare the Thermidorians from criticism either.

Throughout, Palmer shows a clear preference for moderation. He tends to praise figures like Barère or Carnot when they show pragmatism or hesitation toward the use of violence. Barère is labelled, for instance, a “reluctant terrorist,” someone who chose expediency over fanaticism. In contrast, Palmer is more critical of those he sees as driven by ideology. Figures such as Billaud-Varenne or Collot d’Herbois are portrayed less sympathetically, as hardliners whose insistence on revolutionary purity helped drive repression too far.

Even here, Palmer does not resort to caricature. He places the actions of extremists in context, explaining their behaviour as a product of pressure rather than inherent cruelty. His bias, to the extent that it appears, leans toward moderate, pragmatic politics. He gives implicit approval when the Committee acts with competence and restraint. He shows clear discomfort when ideological rigidity overrides practical judgment.

If anything, the book carries a mild Whiggish tone (6). Palmer seems to view the Terror as a detour from the path of democratic progress, a necessary detour but a detour nonetheless. This aligns with a classical liberal reading of the Revolution, where 1789 and 1793 are seen not as a permanent rupture, but as part of the long and painful emergence of liberal democracy. In the final chapters, Palmer’s relief at the Republic’s military victories and the subsiding of emergency measures feels almost celebratory, implying a return to the Revolution’s original liberal course. Yet, he also soberly concludes with the personal tragedies of the twelve, showing that history’s verdict is complicated.

It is also worth noting what Palmer does not do. Namely, propaganda.

Twelve Who Ruled is not a cautionary tale or propaganda tract. Given that it was written in 1941, with fascism on the rise, one might expect an American liberal to use the French Terror to denounce totalitarianism. But Palmer avoids crude analogies. He lets readers draw their own conclusions. A reader in 1941 might well think of Hitler or Stalin while reading about the dangers of concentrated power, but Palmer does not push that comparison. His portrait of the Committee, a dictatorial body that nevertheless saved France, complicates any simple moral about dictatorship. The lesson is not imposed.

Suitability for Teaching or Further Research

Over the years, Twelve Who Ruled has proven highly effective for teaching the French Revolution and remains a reliable point of entry for further research. Its structured narrative and wide scope make it a strong introduction for students and general readers, while its analytical precision offers more experienced readers material for reflection and debate. Within Anglophone historiography, few works cover Year II with the same aplomb.

The book’s focus on individual leaders and specific crises helps anchor the chronology of 1793 to 1794 in something tangible and humane. Because Palmer explains context as he goes, for example by giving background on the Vendée revolt, the Federalist insurrections, and the food shortages, it allows even newcomers to the topic to grasp the wider dynamics of the period.

Its limitations are those of its time. Now more than eighty years old, the book does not reflect more recent developments in the field. Questions of gender, global context, symbolic culture, and the experience of ordinary people are not part of Palmer’s framework.

Most importantly, the book is so well-written that even someone unaccustomed to reading non-fiction will find it engaging. It does not demand specialist knowledge, but it never talks down to the reader. As an introduction to the French Revolution, it is hard to beat. Few works manage to be this serious, this readable, and this enduring at the same time. It remains a book worth reading, not just for what it says about 1793, but for how well it says it.

Notes

(1) This is worth a post of its own, but in short—and this is an extremely simplified summary—the historiography of the French Revolution can be broadly outlined as follows:

Conservative reaction (1790s to 1890s): Sees the Revolution as a catastrophe that overturned legitimate order. Authors: Edmund Burke, Hippolyte Taine, Louis de Bonald.

Liberal narrative (1820s to 1910s): Praises the moderate reforms of 1789, condemns later extremism, and stresses continuity with the Old Regime. Authors: Adolphe Thiers, Alexis de Tocqueville, François Guizot.

Radical republican and proto-socialist (1840s to 1930s): Celebrates popular egalitarianism and defends Jacobin democracy. Authors: Jules Michelet, Louis Blanc, Jean Jaurès.

Marxist classical social school (1920s to mid-1960s): Frames the Revolution as a bourgeois class struggle that abolished feudalism and views the Terror as a necessary defence. Authors: Albert Mathiez, Georges Lefebvre, Albert Soboul, Michel Vovelle.

Revisionist critique (mid-1960s to late 1980s): Rejects the class model, emphasises political contingency and the culture of violence. Authors: Alfred Cobban, William Doyle, François Furet, Simon Schama, Patrice Gueniffey.

Post-revisionist and cultural turn (late 1980s to 2000s): Combines political and social analysis, focuses on language, symbols, and local experiences. Authors: Lynn Hunt, Timothy Tackett, Jean-Clément Martin, Mona Ozouf, Roger Chartier, Peter McPhee, Hervé Leuwers.

There are also several other areas of research like Gender History and Colonial Perspectives which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s.

(2) It goes without saying that recent post-revisionist trends, including cultural and gender-focused approaches, lie outside Palmer’s scope. These methodologies only emerged decades after 1941. Palmer does not, for example, examine revolutionary festivals, political symbols, or the “culture of citizenship” as later cultural historians would.

(3) This is not unique to Palmer. Most scholarship of his time ignores marginalised groups, including women, the poor, enslaved people, and colonial subjects.

(4) PSA: if you are reading a history book on a specific country or event, and most of its sources are not in that country’s language, stop reading.

(5) Palmer does recount the demand of 5 September 1793 to make terror “the order of the day,” but he treats it as a historical moment rather than an ideological programme.

(6) Whiggish refers to a teleological view of history, typically associated with 19th-century liberal thought. It sees the past as a steady march toward progress, constitutional government, and political liberty. A “Whiggish” historian tends to interpret events as steps on the road to modern democracy, even when those steps include violent detours.

#CHILDISH PRETENTIONS TO LEARNING#“All died with fortitude except Camille” << Ouch. Yikes asshole.#But my library has auto-renewals & I just keep not returning this book & reading parts over & over#I dread having to return it.#frev#the twelve who ruled#camille desmoulins#french revolution#book reviews#I have so much to say about Camille it would be weird to infodump#but I cannot pass up the chance to insert thoughts when the opportunity presents itself.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharing the Google Translate results so I can feel like I did something useful while I was supposed to be working....

Couthon, member of the National Convention

No. 62.

At Ville-Affranchie, October 30, Year II of the Republic, etc.

You haven't written me a line, my friend, since we parted; I'm angry with you because you promised that in any case of absence, you would give me news of yourself. Hérault was kinder than you; I received two of his letters. You know, my dear friend, that I need, to console myself for the ills that overwhelm me, expressions of interest from those I esteem; so tell me that you exist, that you are well, that you haven't forgotten me, and I will be happy.

I live in a country that needed to be completely regenerated; the people there had been kept so tightly chained by the rich that they were virtually unaware of the revolution. We had to go back to the alphabet with him; and when he learned that the Declaration of Rights existed, and that it wasn't a chimera, he became quite different. Yet, this is not yet the people of Paris, nor of Puy-de-Dôme, far from it. I believe that people here are stupid by temperament, and that the fogs of the Rhône and the Saône carry a vapor into the atmosphere that equally thickens ideas. We have requested a colony of Jacobins, whose efforts, combined with ours, will give the people of Ville-Affranchie a new education, which, I hope, will nullify the influences of the climate.

The cold, which is beginning to be felt keenly here, greatly increases my pain; I would like to go and breathe a little of the southern air; Perhaps I could render some service to Toulon: but I desire that it be a decree from the committee that sends me there, for, without it, the colleagues, or rather the friends with whom I work here, might well not let me go. Pass me this decree, and immediately the nimble general will set off, and either hell will intervene, or the system of vive-force will take place in Toulon, as it took place in Lyon. Farewell, my friend; embrace Robespierre, Hérault, and our other good friends for me. Toulon burned, for it is absolutely necessary that this infamous city disappear from the soil of liberty, Toulon burned, I return to you, and take root there until the end. My wife, Hippolyte, and I embrace you from the bottom of our hearts.

Signed G. Couthon.

P.S. We have agreed, with General Doppet, to send a reinforcement of fourteen thousand men to Toulon, well-armed and well-trained in the profession of war.

I have instructed Daumale, our secretary, who left a few days ago with dispatches for the committee, to ask if I could keep the telescope of the famous Prècy, of which I am jealous, as a historical piece. Let me know if the committee thinks I can, without any inconvenience, retain this piece.

To Citizen Saint-Just.

Does anyone here have that one letter from Couthon to Saint Just where Couthons complaining that SJ is not replying to him, that even Robespierre replied and to just give him a sign that he's alive? I feel like I'm going crazy trying to find it or that I just made it up...

#I know it's not funny but kinda lol @ People are stupid because of the FOG!#I probably fucked this up somehow. The copy-paste from the doc to Translate was not great. I tried to clean it up but my French sucks so...#Sorry if it's not good!#frev#french revolution#georges couthon#saint just

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

What if the whole frevblr unites and creates an accurate frev movie that is like 9 hours long and we stream it on all streaming platforms and cinemas and make sure the whole world sees it cause we are all fucking tired of seeing the French Revolution portrayed inaccurately in every single piece of media ever?

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

[the words remain]

a double poem for camille desmoulins and saint-just.

I cannot figure out how to make the formatting work on tumblr (please enlighten me if you know how to do it!), so i made the words in bold for saint-just and italic for them both. below the cut.

[camille] [saint-just]

it is not his death he is afraid of

it is the little pauses, gaps between the words

the deafening admission of the silence yet to come

ready to slash, to twist, to crown or to denounce

the leaders and the martyrs, soon to be forgotten

it is the crowds, implacable

and ready now to claim him for their own

to call him victim, and to call him traitor

to call him tyrant, in sweet relief for having found

someone to blame

someone to sacrifice

and he’d be willing

and he would think it just

for proclamations, for a call, for revolution

to let them draw his blood for ink

a fair price for his words

that once built a republic

he started it in summer heat

he’d see it fade away if he looked back (he doesn’t)

in summer heat it ends

a miracle, an after-image

and he blinks out the tears,

but crowds are getting louder

and guillotine awaits

he mounts the steps,

thinks of the speeches that he’ll never write

and throws away the years he could’ve had

is this the end?

as liberty has turned into another slogan

as justice falls in empty syllables

accused, convicted and condemned,

and yet: the words remain.

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Asked and answered! Thank you! Literally the only person I remembered from the French Revolution was Robespierre before I accidentally read the Demon of Writing and tripped and fell hard down this rabbit hole. Like, I could never even remember which Louis was king. It feels like I discovered a secret universe, except it's extremely not secret, we're just not taught practically anything useful about it.

Why's it so hard to find Saint-Just's writings in English? I have been reading your Organt translation (thank you!!) and I downloaded the Oeuvres linked on Wikipedia, but I have a shitty American high school education in French haha so... it's gonna be a task. I keep seeing references to his philosophy & politics but it's so hard to find the actual original sources. How is the work of someone so famous so obscure?! Is it somewhere that I just haven't found?

I'm not saying I won't sit here typing it into Google Translate but I'm sure actual translators would do better!

Thanks for your question! When I was first getting into Frev, I was frustrated by the same thing.

For Saint-Just in particular, I don’t think he’s studied much outside of France. If anyone attended primary school in France, I’d be interested in knowing how he is discussed in class, so feel free to chime in.

I can only speak to my American educational experience, but the French Revolution was discussed only briefly and very simplified: Marie Antoinette was super into cake and then Robespierre showed up and murdered everyone. The end.

In that context, SJ was a relatively minor figure; Camille gets a shoutout if the Bastille is mentioned, but that’s the extent of what we’re taught in America.

Organt isn’t considered a shining example of French literature in SJ’s time or in ours. It’s just not good compared to other writings from the time (although it has its moments). I don’t think there’s a demand for this relatively obscure text in English by the general public or historians broadly. It’s very niche and you only know about it if you happen to learn more about SJ specifically. Even he distanced himself from that work after it flopped. I’ve thought that he probably wouldn’t care to have it translated into more languages- his work and writings for the Revolution were closer to his heart in the end.

I’ll admit that I am disappointed that the biographies that exist about him have not been translated into English. To me, those would have more mass appeal to people than his poem (unless you are researching that work specifically).

I think Organt is still very interesting in that we see an SJ before the drastic change of his life. It’s an important base for him, but not so much outside of that context.

His speeches and other writings have a better chance of being translated into English. Again, there’s a lack of demand for it from the public. You’d have to have an academic intentionally publish those if only for the sake of contributing to the pool of resources and many of them are frying bigger fish. He’s famous to us because we’re into the French Revolution, but the average person outside of France probably only recognizes the Big Names like Antoinette, Robespierre, Marat, and King Louis (again, from my experience as an American).

It also doesn’t help that he had a whopping 2 years of participation before he died. Had he lived, I think he would have gone on to have a brilliant career and gained more prominent recognition. He accomplished a lot in the time he had, but the loss of his potential is a greater wound. Who knows? He could have been a bigger name if he had more time and thus we have more demand for his works in other languages.

For now, we get to have what he did leave behind and even “unofficial” attempts at translating his work and his story are important to the study of history. This lovely community here has shown how much they want to continue to tell the stories of not just SJ, but of the other revolutionary figures. Any knowledge is good knowledge, even if you have to struggle to get it yourself.

I know this was long, but these were just my thoughts. Others are free to add their own!

#The Demon of Writing needs to come with a warning - DANGER for those prone to getting stuck down rabbit holes#Or an advertisement for anyone looking for a new kinda awkward obsession#french revolution#saint just#frev

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

74K notes

·

View notes

Text

YOU!! YES, YOU!! GO WRITE THAT FANFIC YOU THINK NOBODY BUT YOU WILL READ!!

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

February has finally come to an end, and being the so-called "month of love" (or so the obscene number of pink Hallmark cards in supermarkets would have me believe), I thought—despite being very, very late for Valentine’s Day (when am I not late for everything?)—I’d take the opportunity to talk about Robespierre’s love life. Because surely, he had one, right?

Well... that depends on who you ask. Accounts of Robespierre’s romantic escapades range from total abstinence to secret debauchery and a supposed porn addiction, depending on which political or moral flavour the historian (1) writing the accounts subscribes to.

In case you’re dying of curiosity: there is precisely zero evidence that Maximilien Robespierre slept with anyone—man, woman, or even himself. Nothing. Nada. Zilch.

Does this mean he didn’t? Was he asexual? Abstinent? Just busy?

No. It simply means that if he did have any romantic or sexual encounters, he was extremely discreet about them (and why wouldn’t he be? It’s not as if he’d start randomly monologuing about his love life mid-speech at the Convention or the Jacobins).

As for his relationships with women, here’s what we do know:

As a politician, he was wildly popular with women, to the point of receiving marriage proposals in the mail.

He never married, and while rumours of his engagement exist, they remain just that—rumours. He died at 36, unmarried, childless, and leaving behind no diary or trove of love letters to illuminate his feelings.

He has been posthumously linked to three women: Anaïs Deshors, Éléonore Duplay, and Annette Duplessis. However, these claims are flimsy at best, often put forth by people with their own agendas.

He did, however, write love poems to several women in Arras: a Miss Orptelia Mondlen, a Mlle Henriette, an Émilie Demoncheaux (on the eve of her wedding, no less), and a certain Sylvie.

In short, if we want to find any direct evidence of Robespierre’s feelings towards women, we have to turn to his poetry. And since this is Robespierre—where everything must have some kind of political dimension—let’s talk about how his one publicly released love poem was used against him in the monarchist press.

Robespierre’s Love Poems

As mentioned, a number of love poems have been attributed to Robespierre, though not always convincingly. He wasn’t particularly eager to see them published, and only one ever made it to the general public during his lifetime—both times without his consent.

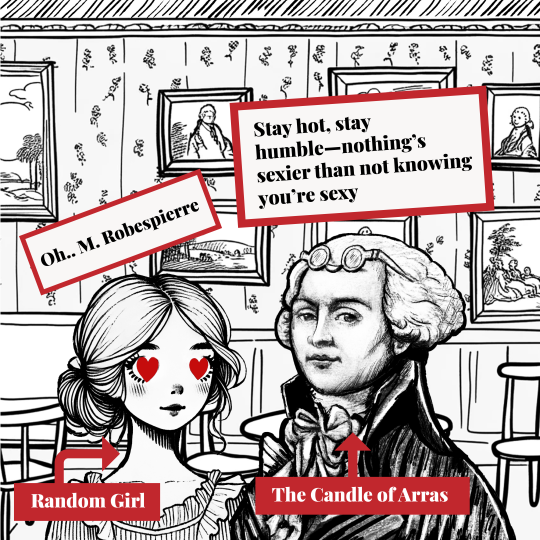

The poem in question is a madrigal dedicated, according to the Œuvres, to a “Miss Orptelia (possibly Ophelia?) Mondieu.” It was first published anonymously in 1787 in two different collections, without Robespierre’s knowledge. Later, it was republished—again without his consent—by the royalist writer François-Louis Suleau (2), who used it to mock him.

Here’s the poem:

Madrigal

Crois-moi, jeune et belle Ophélie, Quoi qu’en dise le monde et malgré ton miroir, Contente d’être belle et de n’en rien savoir, Garde toujours la modestie. Sur le pouvoir de tes appas Demeure toujours alarmée Tu n’en seras que mieux aimée, Si tu crains de ne l’être pas.

And my translation:

Madrigal

Believe me, young and beautiful Ophélie, No matter what the world may say, and despite thy looking-glass, Content to be beautiful yet know naught of it, Keep thy modesty always. Be ever wary of the power of thy charms; Thou shalt be all the more loved, If thou fearest not being unloved.

Baudelaire, he is not. But it’s charming in its own earnest, slightly awkward way, no? Hardly the stuff of grand, sweeping romance, but if someone wrote this for me, I’d at least pretend to be flattered.

So why was it mocked? Well, for Suleau and his fellow scribes at Actes des Apôtres (3), this was an opportunity far too delicious to ignore.

The Mockery of Suleau

In a November 1789 issue of the paper, Suleau went after Robespierre with sharp sarcasm, mocking him over a minor linguistic mistake in one of his speeches—using "aristocrassique" instead of "aristocratique"—and dismissing him as a mere "poor scholarship student," while feigning an air of condescending generosity. Then came the poetic insults: Suleau sarcastically presented the madrigal as a work of supreme literary genius, only to rip it apart.

He compared Robespierre’s writing to Tacitus, only to immediately undercut the compliment by drawing a parallel to Montesquieu—before mockingly dismissing the comparison, given Montesquieu’s "aristocratic tendencies."

The pièce de résistance? A biting final flourish in which he ironically declared Robespierre a polymath—poet, historian, geographer, naturalist, physicist, journalist, legislator—before delivering the ultimate insult: if Mirabeau was the “torch of Provence,” then Robespierre was merely the “candle of Arras.”

In case it wasn’t obvious, this had little to do with Robespierre’s poetic talents and everything to do with his politics.

Robespierre’s Response

How did Robespierre react? He didn’t. Not a word—not even to disavow the poem. Clearly, he subscribed to the "don’t feed the trolls" school of thought.

The fact that he didn’t deny authorship was enough for historians like Eugène Déprez (who compiled the first volume of Robespierre’s Œuvres Complètes) to confidently attribute it to him.

What Do His Poems Tell Us About Him?

Is that enough proof? Debatable. But even if we accept that Robespierre wrote this madrigal and the other five attributed love poems (mediocre as they may be), what do they actually tell us about him?

His greatest fan, historian Albert Mathiez, thought these poems proved that "far from possessing a barren heart, as some have claimed, he was endowed with a trembling sensitivity and by nature sought the company of the fairer sex."

Did he? Do these light verses really reveal that much?

Personally—and this is just an opinion, because when it comes to Robespierre’s love life, opinions are all we have—I think what these poems tell us most is that, back in the 1780s, Robespierre understood what was expected of a proper gentleman and was trying to play the part. In short, he was capable of fulfilling societal expectations.

That doesn’t mean he never had romantic feelings, but as far as we know, despite the interest some women clearly had in him, none of these romantic fantasies ever became anything more than words on a page.

Note (1) Frankly, the word "historian" is no guarantee of quality research when it comes to the French Revolution).

(2) François-Louis Suleau, a royalist journalist who attended school with Robespierre and Desmoulins, later becoming one of their most vocal critics.

(3) Actes des Apôtres was a royalist newspaper published during the early years of the French Revolution. Founded in 1789 by Jean-Gabriel Peltier and featuring contributors like François-Louis Suleau, the publication served as a satirical and polemical counter-revolutionary voice. It's actually quite funny to read.

#I did skip this post for a second with my brain being like NO SPOILERS!...#I'm reading “Robespierre & the Women He Loved”...#I know there's controversy over when spoilers expire but I think general consensus may be <200 years#Get it together brain.#frev#french revolution#robespierre

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 5th, 1794: Camille Desmoulins went to the Place de la Révolution to die.

There was no journal left to write, no crowd to stir, no chance to rewrite the last page. He had already said too much.

The Revolution had eaten through its own flesh, and Camille, once its poet, was now just another name on the list.

He left behind one final letter. Not quite a manifesto. Just a man, waiting to die, writing to his wife.

The Last Letter of Camille Desmoulins

Duodi germinal, 3 a.m. (April 1st)

Sleep has mercifully suspended my suffering. In sleep, one is free, unaware of captivity. Heaven has shown me mercy. Just moments ago, I saw you in a dream: I embraced you, Horace, and Daronnen (1), who was at home. But our little one had lost an eye to some fury that had attacked him, and the pain of this vision woke me. I found myself back in my dungeon. It was daylight. Though I could neither see you nor hear your replies, even as you and your mother spoke to me, I rose to write to you at least.

But opening the windows, the thought of my solitude, the dreadful bars and bolts that part me from you, vanquished all the strength of my soul. I melted into tears, or rather, I sobbed, crying out in this tomb: Lucile! Lucile! O my dearest Lucile, where are you?

(here, we notice the trace of a tear).

Yesterday evening I experienced a similar moment, and my heart broke anew when I saw your mother in the garden. A reflexive movement drove me to my knees against the bars; I clasped my hands together as if begging for her pity, she who must be weeping now in your embrace.

Yesterday I saw her sorrow

(here again a trace of tears)

In her handkerchief and veil, lowered as if she could not bear the sight. When you come again, let her sit a little nearer to you, so that I might see you both more clearly (2).

It is not dangerous, as far as I can tell. My spectacles are no good. I'd like you to buy me a pair like I had six months ago, not silver but steel, with two arms that attach to the head. Ask for number 15;: the merchant will know.

But above all, I implore you, Lolotte (3), by our eternal love, send me your portrait. Let your painter take pity on me, I who suffer only for having shown too much compassion for others. Let him grant you two sittings each day. In the horror of this prison, the day I receive your likeness would be a day of celebration, of pure rapture and intoxication.

In the meantime, send me a lock of your hair that I may press it to my heart. My dear Lucile! Here I am, back in the days of my first love, when I was interested in someone merely because they had come from your house. Yesterday, when the citizen who brought you my letter returned, I asked him "Well, have you seen her?", just as I used to ask Abbé Landreville. I found myself studying him as if something of you had lingered on his clothes, on his very person.

He is a charitable soul, for he delivered my letter intact (4). It seems I shall see him twice daily, morning and evening. This messenger of our sorrows has become as dear to me as a bearer of joys once would have been.

I discovered a crack in my cell; I pressed my ear to it, and heard a groaning. I hazarded some words, and a voice answered: a sick man in suffering. He asked my name. I gave it. “O my God!” he cried at hearing it, falling back upon his bed, and I distinctly recognised the voice of

Fabre d’Églantine (5).

(Yes, I am Fabre, he told me; but you, in here! Has the counter-revolution succeeded?)

Yet we dare not speak further, for fear that hatred might deprive us of even this small consolation. Should we be heard, we would surely be separated and confined more strictly. He has a room with a fireplace; mine would be a fair chamber... if a dungeon could ever be called fair.

But, dear friend! You cannot imagine what it means to be held in secret, not knowing why, never interrogated, never receiving a single journal. It is to live and be dead at once, existing only to feel oneself buried in a tomb. They say innocence is calm and courageous.

Ah!

My dearest Lucile! My beloved! Often, my innocence is weak like that of a husband, that of a father, that of a son (6)! If it were Pitt or Coburg who treated me thus…! But my colleagues! Robespierre, who signed the order of my imprisonment! The Republic, after all I have done for her! Is this the reward for so many virtues and sacrifices?

When I first arrived, I saw Hérault-Séchelles, Simon, Ferroux, Chaumette, and Antonelle (7). They suffer less than I do, at least they are not held incommunicado.

And I, who for five years devoted myself to hatred and peril in the name of the Republic. I who kept my poverty through the Revolution (8). I who have none to ask forgiveness but you, my dear Lolotte, and to whom you granted it, knowing my heart, despite its frailty, was not unworthy of you. I am cast into a dungeon, in secret, as though I were a conspirator! Even Socrates was allowed to see his friends and wife in prison when he drank the hemlock (9).

How much harder to be torn from you! Even the worst criminal would suffer too cruelly if separated from a Lucile by anything except death—which at least makes one feel such agony for but a moment. But a criminal could never have been your husband, and you loved me because I lived solely for the happiness of my fellow citizens... They call me...

Just now, the commissioners of the Revolutionary Tribunal have questioned me. One question only: “Have you conspired against the Republic?” What derision! Is it thus they insult the purest republicanism?

I see the fate that awaits me. Farewell, my Lucile, my dear Lolotte, my good little wolf, say farewell to my father. In me, you see the example of man’s barbarity and ingratitude. My final moments will not disgrace you. You see that my fears were justified, that my presentiments were always true.

I married a woman heavenly in her virtue. I was a good husband and a good son; I would have been a good father. I carry with me the esteem and the regrets of all true republicans, of all men, of virtue and of liberty.

I die at thirty-four, yet it is a marvel that I have survived these past five years and so many revolutionary precipices without falling into them. That I still exist and rest my head in calm upon the pillow of my writings; too numerous, perhaps, but all breathing the same philanthropy, the same desire to make my fellow citizens happy and free, writings that the tyrants’ axe shall never strike down.

I see now that power intoxicates almost all men, that they all speak as Dionysius of Syracuse (10):

“Tyranny is a fine epitaph.”

But take comfort, desolate widow! The epitaph of your poor Camille is nobler still: it is that of the Brutuses and the Catos, the slayers of tyrants (11). O my dearest Lucile! I was born to write verse, to defend the wretched, to make you happy, to compose, with your mother, with my father, and a few souls after our own hearts, a little Tahiti (12).

I had dreamed of a Republic that all mankind would adore. I could not believe men were so savage and so unjust. How could I think a few jests in my writings, aimed at colleagues who had provoked me, would erase the memory of all my services?

I do not deceive myself: I die a victim of those jests (13) and of my friendship with Danton (14).

I thank my assassins for letting me die with him and with Philippeaux (15). Since my colleagues were cowardly enough to abandon us, to lend an ear to slanders, of which I know nothing, save that they must be vile, I may say we die martyrs of our courage in denouncing traitors and of our love for the truth.

We can at least take with us this testimony: we perish as the last true republicans.

Forgive me, dear friend, my true life, which I lost the moment we were parted. I find myself dwelling on my legacy when I should focus only on helping you forget.

My Lucile! My good Loulou! My hen of Cachant (16)! I beseech you, do not linger on the branch, do not call to me with your cries; they would tear me to pieces in the depths of the grave. Go scratch the earth for your little one, live for my Horace (17); speak to him of me. Will you tell him, though he cannot yet understand, that I would have loved him dearly?

Despite my torment, I believe there is a God. My blood shall wash away my faults, the weaknesses of humanity, and God will reward what was good in me: my virtues, my love of liberty. One day, I shall see you again, O Lucile! O Annette!

Sensitive as I was, is death, which delivers me from witnessing so many crimes, so terrible a fate? Farewell, Loulou; farewell, my life, my soul, my goddess on earth! I leave you good friends, all men of virtue and feeling.

Farewell, Lucile, my Lucile! My dear Lucile! Farewell, Horace, Annette, Adèle (18)! Farewell, my father! I feel the shore of life receding before me.

I still see Lucile! I see her, my beloved! My Lucile! My bound hands embrace you still, and my severed head rests its dying eyes upon you.

Notes:

The original French text comes from the Correspondance inédite de Camille Desmoulins, published by M. Matton aîné (Ébrard, Paris, 1836). The translation is mine.

(1) Daronne was a nickname Camille had for his mother-in-law

(2) Camille was imprisoned in the Luxembourg. Families of prisoners would gather in the prison garden so their imprisoned relatives could see them from the jail cells above.

(3) Lolotte was Lucile’s nickname

(4) "Intact" in this case means uncensored, as prisoners' letters were routinely read and censored..

(5) Fabre d’Églantine (1750–1794) was a playwright, poet, and revolutionary politician, best known for creating the names of the months in the French Republican Calendar and for his close association with Danton.

(6) The phrasing is a bit awkward in English, but what Camille is trying to say is that human bonds make him vulnerable. He's not admitting guilt; he's defending his innocence, but he's acknowledging that emotional attachments can make one act from the heart rather than from strict principle or legality.

(7) Hérault-Séchelles was a member of the Committee of Public Safety and played a key role in drafting the constitution. Though not strictly aligned with the Dantonists, he was executed alongside them on April 5th.

Simion most likely refers to Jean-Baptiste Simon, less prominent, but known as a journalist and moderate revolutionary

Ferroux's identity is problematic. While there was a Ferroux imprisoned at that time, little is known about him as he wasn't a prominent figure. Some editions of the letter suggest this is a misrendering of either Philippeaux's name or refers to Jean-Pierre-André Amar.

Chaumette is Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette a leading figure of the Hébertist faction; radical dechristianiser; President of the Commune of Paris

Antonelle is François-Joseph-Marie Fayolle d’Antonelle A moderate republican, journalist, editor of Le Républicain, and supporter of the Girondins.

(8) Camille is very much stretching the truth here …

(9) Socrates was sentenced to death by the Athenian court in 399 BCE and died by drinking a cup of hemlock, a poisonous plant, as punishment for impiety and corrupting the youth.

(10) Dionysius I, tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily during the 4th century BCE, known for his authoritarian rule and for transforming Syracuse into a major military power. He became a symbol of despotism in classical literature and later political thought, often cited as an emblem of how power corrupts and tyranny can be glorified despite its brutality.

(11) Brutus and Cato the tyrannicides refer to Marcus Junius Brutus and Marcus Porcius Cato the Younger, two influential figures of the late Roman Republic who stood against dictatorship. Brutus helped kill Julius Caesar in 44 BCE to protect Rome's freedom, while Cato opposed Caesar through political means and chose suicide rather than live under his rule.

(12) The original is "composer, avec ta mère et mon père, et quelques personnes selon notre cœur, un Otaïti." Camille is referring to Tahiti (Otaïti being the 18th-century French spelling). After Bougainville's 1768 voyage, Tahiti captured the European imagination as an idyllic paradise, a place of natural abundance, innocence, and harmony, untouched by civilization's corruption.

(13) To see the jests he is referring to, I recommend you take a look at Camille's last publication, Le Vieux Cordelier. The first two issues aligned with Jacobin's sentiment, but from the third onward, he diverged from the party line and called for moderation. His tone, satirical, accusatory, and morally urgent, was perceived by many as politically subversive and ultimately led to his arrest.

(14) Georges Danton (1759–1794) was a leading figure of the French Revolution, known for his oratory, role in founding the Revolutionary Tribunal, and early leadership of the Jacobin movement. He and Camille Desmoulins were close friends and political allies… their relationship is far too involved and complicated to explain in a short note.

(15) Pierre Philippeaux (1754–1794) was a Convention member sent on mission to the West. His detailed report exposed the brutal repression in the Vendée, especially atrocities by Republican forces under Jean-Baptiste Carrier. Camille used this report in Le Vieux Cordelier to support his plea for clemency. Philippeaux's testimony provided concrete, documented evidence of revolutionary excesses, strengthening Camille's argument that the Revolution had strayed from its principles.

(16) Translation from the original notes of the 1835 edition of the letter: Cachant is a small village near Paris, on the road to Bourg-la-Reine, where Madame Duplessis owned a country house. During their visits to Mme Duplessis, Camille and Lucile had often observed a hen in Cachant that, grief-stricken at the loss of her rooster, perched day and night on the same branch. She would emit heart-rending cries, refuse all food, and seemed to long for death. This is the hen to which Camille alludes here.

(17) Horace was the young son of Camille Desmoulins and Lucile Duplessis, born in 1792 and just a toddler at the time of his parents’ execution in 1794.

(18) Translation from the original notes of the 1835 edition of the letter: Lucile's sister, who never married and lived with her mother, became her sole consolation after the deaths of Camille, Lucile, and M. Duplessis.

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Authors should not be ALLOWED to write about–” you are an anti-intellectual and functionally a conservative

“This book should be taken off of shelves for featuring–” you are an anti-intellectual and functionally a conservative

“Schools shouldn’t teach this book in class because–” you are an anti-intellectual and functionally a conservative

“Nobody actually likes or wants to read classics because they’re–” you are an anti-intellectual and an idiot

“I only read YA fantasy books because every classic novel or work of literary fiction is problematic and features–” you are an anti-intellectual and you are robbing yourself of the full richness of the human experience.

91K notes

·

View notes

Note

Archive of Our Own (ao3), the internet

18K notes

·

View notes