Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I find it really interesting that Mark has yet to have his "winning" moment, especially contextualized in a world where winning means killing or death. As you pointed out in your analysis, having your name be "Invincible" but losing every battle is a very different take on the classic superhero. Even in movies like Spiderman that center a similarly aged superhero, usually the hero is able to pull out a win at the end of the movie or season. I wonder if the narrative of the show will continue to depict Invincible in this way in the next season, and I wonder if maybe he will find a way to not have to change his ideology while still being a superhero.

@theuncannyprofessoro

A Cultural Studies Analysis on Invincible

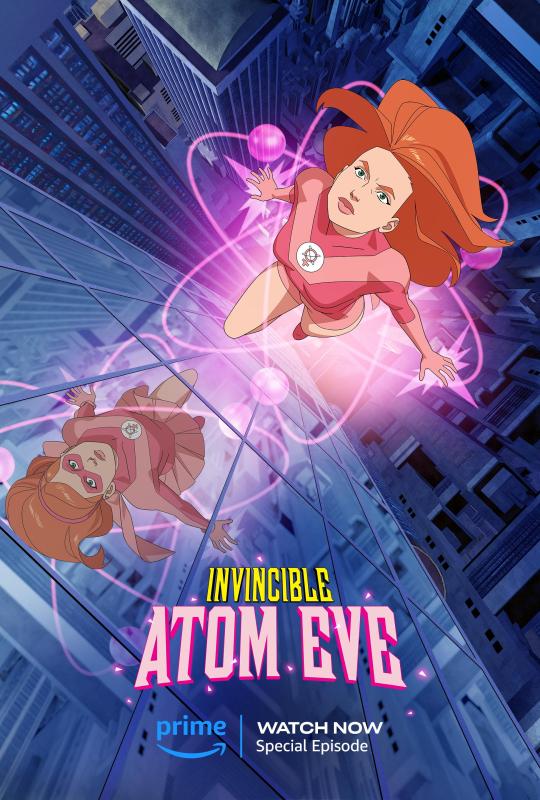

In my video essay, I looked at Prime Video’s Invincible (2021-) and analyzed the various themes of identity that appear throughout the show, all revolving around the main protagonist of the series, 17-year-old Mark Grayson. I pair this up with various Critical Studies sources that cover reception theory and critical race theory and intersect some of the arguments made to highlight cases of othering within the show. As mentioned, the analysis is centered around Mark’s identity as a superhero, as a young adult, and as a half-Human and half-Viltrumite, as he develops his powers and ‘learns the ropes’ of the superhero job.

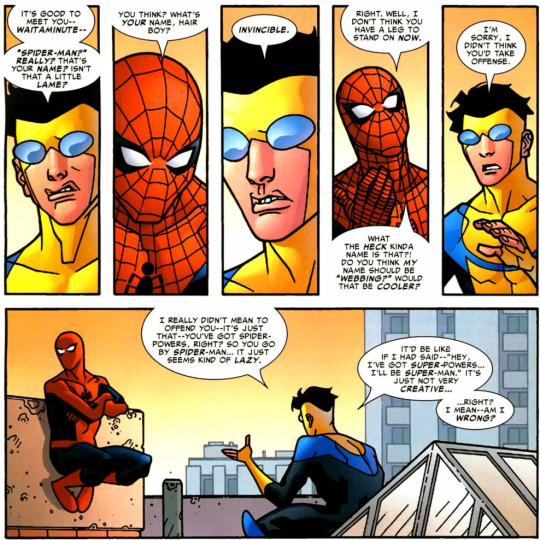

In regards to his identity as a superhero, I look at how Mark/Invincible is othered in the scope of superhero media through how his origin story diverts the theme of loss and redemption. Stuart Hall’s reception theory delves into the coding and decoding of messages in certain texts.[1] I pair his argument on how instances of codes can be made to appear as though they haven’t been constructed anymore because of how popular or generally used they’ve become in certain communities with Max Horkheimer’s and Theodor W. Adorno’s argument that in the production of mass culture, more specifically in media, the audience can more or less easily predict the structures and narrative elements of the piece.[2] Superhero media is one of the highest-grossing genres currently across both television and film, meaning that audiences have grown accustomed to the stories of the genre. A result of that is a discourse that mirrors the arguments made by Hall, Horkheimer, and Adorno. Fingers have been pointed specifically at large corporations such as Disney, who mass-produce superheroes in a manner that utilizes the same molds and structures repetitively and has greatly influenced superhero media across the Western production world especially. Attempts at creating unique texts in this genre have been made, resulting in the subgenre of ‘capepunk’, a genre that aims to tell more grounded and realistic superhero worlds and critique mainstream superhero media while making use of adult themes and explicit content. This genre has been popularized in recent years thanks to shows like The Boys (2019-) and Invincible, however, arguments have been made that these types of media eventually end up becoming the media that they’re trying to subvert and critique. I acknowledge that Invincible certainly does appear similar to the media it makes critiques on. It’s not convoluted or unique and fits the descriptions of media that Hall, Horkheimer, and Adorno describe. I do argue that it presents several cases in which it can break off from the mold and create new and refreshing cases that are coded.

The instance I look at in-depth is how Mark continuously faces loss and how this plays into his identity as a superhero. Comparing his journey to a common superhero origin story that is presented in most popular instances of the genre, Mark ticks most of the boxes, but one thing he manages to keep doing is losing. And it ends there. He doesn’t have some kind of redemption or resolution within the episode of the season or the next season, Mark will lose a fight and the episode will end there. We move on to whatever conflict he has to face in the following episode. This is an important aspect of Mark’s origin story, as it not only grounds his story but also reflects his ideology and how it changes. As he physically endures countless beatings and is left unconscious multiple times, his belief in what it means to be a superhero is challenged and broken each time. This repeated loss, however, is interpreted negatively in large circles in online forums who have expressed their annoyance at Invincible’s inability to win fights, or even whether he should be able to call himself ‘Invincible’, causing Mark to be othered from his superhero counterparts across the genre. Mark’s case is seen as unique, in some respects, an early failure in the image of a superhero. I believe this perspective is evidence of being unable to decode the message of the creators on the constant battle that Mark endures in his belief system, which is also symbolized by the title sequence of the show. The “INVINCIBLE” title card is splattered with more blood each episode of the first season, mirroring the repeated damage that Mark endures, while in the second season, the title card is completely covered in blood and begins to crack. The cracks grow in each episode, revealing a new layer underneath.

I bring up how this is made more clear in the second season, more specifically in the mid-finale, and present clips and narration on a case where Mark’s ideology takes a drastic shift. The entire premise of learning to fight with the mentality of killing the opponent creates an opportunity where Mark can go toe to toe with his opponent, yet this ideology conflicts with his identity as a superhero, and this conflict causes him to ultimately lose the fight. This ideology is not only tied into Mark’s identity as a superhero, as additionally, it is also his racial identity. As mentioned in the video, the Viltrumite alien race is coded with the definitions of colonialism, imperialism, and racism that Robert Stam and Louise Spence present.[3] They use their superhuman abilities to kill and conquer different alien races across the galaxy. Mark, the only Viltrumite in the entire galaxy that opposes this idea and seeks to protect his Earth, is othered by other Viltrumites. Interestingly enough, physically and biologically, Mark is a Viltrumite, but they are completely indistinguishable from humans apart from the supernatural abilities they possess and their prolonged life spans. Mark seeks to other himself as much as possible from the Viltrumites. This is symbolized by his superhero outfit that sports a color scheme of yellow, blue, and black and has a unique design, which is completely different from the white and grey uniforms that Viltrumites wear, depicting the uniformity of military garments. Mark’s father, Omni-Man, wears a unique combination of the base of the Viltrumite uniform with a human superhero design on it, symbolizing how he is caught in between these two worlds which is explored more in the second season of the show.

Mark steers away from conforming to Viltrumite ideologies and fights and prepares to save or liberate Earth (and potentially the galaxy) from Viltrumite's influence. I mention how his Asian identity fits the mold of Stam and Spence’s argument on naive integrationism, as the creators substitute an Asian character into a role dominantly played by white characters and never truly explore his Asian identity, however, I argue that Mark’s role as an active opposer of the coded ideologies Viltrumites embody, and therefore doesn’t play Stam and Spence’s argument.[4]

Invincible creates a unique plot in a medium that is saturated with the elements that the show subverts. Mark embodies roles that while othering him from his counterparts both beyond and within the scope of the show, present the case for an unlikely superhero who may be able to surpass those around him. Especially when he’s able to win his first major fight.

[1]Stuart Hall, “Encoding, Decoding,” 551

[2]Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” 98-99

[3]Robert Stam, Louise Spence, “Colonialism, Racism and Representation: An Introduction,” 753

[4] Stam, Spence, “Colonialism, Racism and Representation: An Introduction,” 757

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really like the premise of the show because as you said, the show takes a creature that has, in popular culture, been viewed as evil but contextualizes Louis as a character for the audience to root for him. I love your analysis that points to Louis not just as a mechanism for storytelling, but as the narrator of his own story as he tries to understand his journey as a vampire.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Representing a Black Vampire: Louis from Interview with the Vampire (2022)

youtube

Interview with the Vampire, the 2022 remake of Anne Rice’s 1976 book of the same title, tells the story of Louis de Pointe du Lac, an affluent Black man in 1910 New Orleans, as he is seduced and turned into a vampire by Lestat de Lioncourt, a French vampire who becomes his partner in immortality. Louis narrates his life in an interview, set in 2020, to Daniel Molloy, a famous journalist, and recounts his life before and after becoming a vampire, his struggles with moral questions of vampirism and immortality, and his toxic and unequal relationship with Lestat. The show is very intentional in positioning Louis, a gay Black man, as someone who is othered and misunderstood even before becoming a vampire. Scholar Victoria Herche uses Judith Butler’s discourse of queerness to analyze othering and the supernatural in Cleverman (2016-2017): “In reading the monster as a queer category, representations of the monstrous ‘other’, such as the Hairies and the Namorrodor, offer an alternative space beyond normativity and overcome binary constellations of the objectivized ‘other.’”[1] Monsters and supernatural beings, represented through vampires in the show, both signify “otherness” of existing beyond the human, as well as an empowerment for Louis as a marginalized person. In Episode 1, Louis becomes a vampire because of his relationship with Lestat, and in his speech to Louis, the French vampire acknowledges and affirms the othering and alienation Louis experiences, posing vampirism and a relationship with Lestat as a solution:

“This primitive country has picked you clean. It has shackled you in permanent exile. Every room you enter, every hat you are forced to wear [...] all these roles you conform to and none of them your true nature. What rage you must feel as you choke on your sorrow. [...] I can swap this life of shame, swap it out for a dark gift and a power you can’t begin to imagine. You just have to ask me for it. [...] I love you, Louis. You are loved. [...] Be my companion, Louis. Be all the beautiful things you are, and be them without apology. For all eternity.”[2]

The supernatural power of vampirism not only gives Louis superhuman abilities, but it empowers him to take action against the systemic racism and treatment he faces from white peers in his business of sporting houses (read: really fancy brothels). When Louis gains too much financial power, the white businessmen start a systemic effort to push him and other Black business owners out of the city and buy their properties. In retaliation, Louis hangs a sign, reading “Colored Only. No Whites Allowed” on the door of his largest, most successful business, and violently kills a city councilmember who has been working against him, symbolically hanging his corpse in public alongside a “Whites Only” sign. Before Louis kills him, the councilman condescendingly tries to talk him down, saying, “That’s your problem Louis, always has been. You’re arrogant. You haven’t accepted your place in this world.”[3] The supernatural power and protection that being a vampire affords Louis gives him the confidence and the means to take agency and revenge beyond “his place” within the social structure of white supremacy, which he never allowed himself to do before his transformation. Although vampirism has been associated with villainous action, which could serve to demonize rather than justify Louis’s actions, Interview with the Vampire positions this character as the narrator of his own story and therefore allows him to evaluate his own point of view and justify his actions. Traditionally, the role of “narrator-focalizer” in media, especially that which depicts stories of marginalized groups, is taken by a white narrator, who represents “the authoritative liberal perspective,” and “godlike, oversees and evaluates all the positions.”[4] Unlike other depictions of Black characters, who are depicted as villainous and unjustified in taking agency and especially violent revenge, Interview with the Vampire uses Louis’s own point of view on his story as narrative focalizer, and intentionally reverses traditional depictions of vampirism as villainous, showing his transformation as supernatural empowerment and his actions as justified.

This 2022 Louis represents a complete departure from Anne Rice’s 1976 character, who was a white plantation owner. The original book’s only depiction of Black characters were stereotyped enslaved people, who Rice demonized for practicing African descended religious forms and burning down the plantation to kill Louis and Lestat. Robert Stam and Ella Shohat, in their work, “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation,” cite Toni Morrison’s idea of “the contradictory nature of stereotypes:” “Black figures, in Toni Morrison's words, come to signify polar opposites: ‘On the one hand, they signify benevolence, harmless and servile guardianship and endless love,’ and on the other ‘insanity, illicit sexuality, chaos.’”[5] Depicting her monolithic Black characters and their religious forms as superstitious and “primitive,” while also making them the only people to figure out the supernatural reality of the main characters’ vampirism, Rice shows her racism through use of contradictory depictions. This novel, as well as many pieces of media that center the supernatural in New Orleans, position Black spirituality and religion as inherently evil, demonic, or at the very least, “uncivilized” and unscientific, below that of white religion and practice. Such is the case in the New Orleans-set show of American Horror Story: Coven, which positions Black and white witches in opposition to each other, and although Black witchcraft, specifically voodoo, “acts [in the show] as a mode of resistance to gendered and racialized oppression,” Jennifer O’Reilly argues that the show’s depiction of voodoo ultimately relies on racist tropes.[6] According to O’Reilly, “the narrative of voodoo as evil and dark persists in Coven and reifies notions of white racial supremacy.”[7] The 2022 Interview with the Vampire is in conversation with this racist and overdetermined depiction of Black supernatural forms in its source material, especially through voodoo in New Orleans, but the show makes absolutely no reference to voodoo or any other forms of Black spirituality. Some might argue that in not depicting this religious practice at all, Interview with the Vampire exists neutrally, not making a stance in either direction. However, I would argue that in the show’s painstakingly detailed references to the original 1976 novel, which does fall into this racist portrayal of Black characters and their religious forms, not including voodoo, especially in the setting of New Orleans, is significant and matters. The show does not exist in a vacuum, and it seems to intentionally break away from the stereotypical depictions that Hollywood is full of when it could very easily fall into them (as the 1994 film adaptation does). Using the example of Western Eurocentric representations of African religions, Stam and Shohat seek to in their writing to show that “the flawed mimesis of many Hollywood films dealing with the Third World, with their innumerable ethnographic, linguistic, and even topographical blunders, has less to do with stereotypes per se than with the tendentious ignorance of colonialist discourse.”[8] After listing Hollywood’s commonly presented racist discourses around African religion, which “enshrine prejudices in patronizing vocabulary,” the theorists propose alternatives: “In a less Eurocentric perspective, all these "deficiencies" might become advantages: the lack of a written text precludes fundamentalist dogmatism; the multiplicity of spirits allows for historical change; bodily possession betokens an absence of puritanical asceticism; the dance and music are an aesthetic resource,”[9] Interestingly, not only does Interview with the Vampire (2020) erase racist imaginaries of Black supernaturalism from its narrative, but it actually utilizes multiple elements of Stam and Shohat’s examples of decolonized approaches to representation, especially in its “lack of written text.”

The emphasis on oral storytelling in Interview with the Vampire, specifically that of Louis, uplifts his othered voice, and represents a break from the Eurocentric emphasis on the written word that Stam and Shohat refer to. To solve problems of media representations which serve to individualize, moralize, and essentialize “good” or “bad” characters, rather than discourses of power in the media, the theorists propose emphasis on the auditory rather than visual representation “as a way of restoring voice to the voiceless.”[10] The entire narrative of the show relies on the auditory overlay of Louis’ narration in his interview with the journalist Daniel Molloy. Although his reliability as a narrator is called into question many times by Molloy, his apparent untrustworthiness does not serve to discredit his voice as an underrepresented “Other” as it may seem, but rather complicates him as a character. Stam and Shohat make the point that marginalized characters are very easily portrayed as “good” or “bad,” which leads to essentializing and moralizing of those characters, especially when characters of color are seen to represent their entire communities rather than their individual selves.[11] They also note that often, even sympathetic portrayals of marginalized people maintain the presence of a “European or Euro-American character as a mediating "bridge" to other cultures,” aptly named as “bridge character.”[12] In other words, “Media liberalism, in sum, does not allow subaltern communities to play prominent self-determining roles, a refusal homologous to liberal distaste for non-mediated self-assertion in the political realm.”[13] Molloy, who comes from Anne Rice’s novel, represents this bridge character, but is not given as much narrative power as Louis has in the show. Interview with the Vampire effectively discounts the novel’s role of a bridge character, empowers Louis in the narrative, and allows him to play his own self-determining role. In addition, the Eurocentric valuing of the written word over oral storytelling is obliterated through the medium of television, which uplifts Louis’s narrative through auditory means, in comparison to the novel, which, as a book, inherently leans into the written word.

Interview with a Vampire (2022) is an incredibly effective remake of the original novel, casting off implicit discourses of white supremacy and Eurocentrism in exchange for genuinely good representation, and more nuanced and interesting storytelling. The show is incredibly aware of its source material, and clearly makes conscious efforts to diverge from previous problematic narrative elements and use the historical othering of supernatural villains, specifically vampires, to empower marginalized and othered communities and characters. Louis, as a vampire character, and a marginalized queer Black man, is made all the better for every single part of his identity, and Interview with the Vampire truly allows him to, as Lestat foretells in the very first episode, “Be all the beautiful things you are, and be them without apology:” a complex, flawed, and compelling character.[14]

Bibliography:

Herche, Victoria. “Queering the Dreaming: Representations of the ‘Other’ in the Indigenous Australian Speculative Television Series Cleverman.” Gender Forum 81 (2021): 30-47.

O’Reilly, Jennifer. “‘We’re More than Just Pins and Dolls and Seeing the Future in Chicken Parts’: Race, Magic and Religion in American Horror Story: Coven.” European Journal of American Culture 38, no. 1 (2019): 29-41.

Powell, Keith, dir. Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. Season 1, episode 3. “Is My Very Nature That of a Devil.” Aired October 16, 2022, AMC.

Stam, Robert and Ella Shohat. “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation.” In Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media. Routledge, 2014.

Taylor, Alan, dir. Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. Season 1, episode 1. “In Throes of Increasing Wonder...” Aired October 2, 2022, AMC.

[1] Victoria Herche, “Queering the Dreaming: Representations of the ‘Other’ in the Indigenous Australian Speculative Television Series Cleverman,” Gender Forum 81 (2021): 44.

[2] Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, season 1, episode 1, “In Throes of Increasing Wonder...,” directed by Alan Taylor, aired October 2, 2022, AMC. 00:59:32-01:03:09.

[3] Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, season 1, episode 3, “Is My Very Nature That of a Devil,” directed by Keith Powell, aired October 16, 2022, AMC. 00:36:04 -00:36:13.

[4] Robert Stam and Ella Shohat, “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation,” in Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media. (Routledge, 2014), 206.

[5] Ibid, 203.

[6] Jennifer O’Reilly, “‘We’re More than Just Pins and Dolls and Seeing the Future in Chicken Parts’: Race, Magic and Religion in American Horror Story: Coven,” European Journal of American Culture 38, no. 1 (2019): 39.

[7] Ibid, 36.

[8] Robert Stam and Ella Shohat, “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation,” 201-202.

[9] Ibid, 202.

[10] Ibid, 214.

[11] Ibid, 183

[12] Ibid, 205

[13] Ibid, 206

[14] Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, season 1, episode 1, “In Throes of Increasing Wonder...,” directed by Alan Taylor, aired October 2, 2022, AMC. 1:02:53-1:03:04.

@theuncannyprofessoro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched this show this past summer and it broke my heart. Not only was the animation style different than any other animated show I have seen, but the utter bleakness of the ending made me not want to watch anything after. I totally see your analysis when it comes to the color/lighting of the show, and I think it's really interesting that the show makes the demons and the scenes that are more sexual and contain drug abuse significantly more colorful and bright. I also think its interesting that Ryo is constantly painted in white color (lack of color i guess), and Akira has more darker colors surrounding him, because usually those shadows represent good vs evil, but in this show it is revealed to have been switched.

@theuncannyprofessoro

A Queering of Light and Color in Devilman Crybaby

Souring to popularity after its Netflix release in 2018, Devilman Crybaby has become one of the most shocking anime in recent years, critically acclaimed for its unique style and animation. Part of the appeal of Devilman Crybaby is the shock value and the dark themes that capture the viewers. The show incorporates disturbing concepts like the dark nature of humanity and the horrific consequences of unchecked desires and senseless violence. The story of Devilman Crybaby presents the worst parts of humanity and how it is incredibly easy for humans to turn on each other and ‘other’ those who don’t fit in. The show cautions that this ideal is dangerous and ultimately one that will lead us to the path of destruction. Devilman Crybaby uses lighting and different color palettes to distinguish between humans and demons, using the latter as an allegory for otherness.

In a chapter from Film Theory and Criticism, Sergei Eisenstein discusses the formalist qualities of film while focusing on Japanese cinematography and how it allows us to understand the important techniques used when creating art. He goes through the intricacies of cinema as an art form, leading with the idea that “cinema is, first and foremost, montage.” [1] This idea of montage is continuously brought up throughout the article, tying the idea into almost every aspect of film and cinematography. Montage can be thought of in its traditional way but also broken down into parts of a montage, signifying traditional shots while still using the theories relating to montage to understand them. Eisenstein argues that montage is in itself, conflict and therefore because montage shows up in every artistic form, conflict lies at the basis of every art. Conflict can take many forms and is important when creating an interesting shot. He classifies that the conflicts that are cinematographic are those “that are waiting only for a single intensifying impulse to break up into antagonistic pairs of fragments. Close-ups and long shots. Fragments traveling graphically in different directions. Fragments resolved in volumes and fragments resolved in planes. Fragments of darkness and light . . ."[2]

The fragments of darkness and light that exist in contrast with each other are very relevant to the way that Devilman Crybaby is portrayed. The show uses darkness and light to differentiate between the demons and the humans, using each form of lighting to easily distinguish between the two groups. The contrast between the bright white light and the darkness that is used to separate the humans and demons is incredibly obvious. Devilman Crybaby sets the tone for the show with the pure, human-like scenes enveloped in a bright white light. The use of lighting makes the viewer grow comfortable and expect that this is the way that the show will be portrayed and makes it even more shocking when the entire lighting scheme is replaced by shadows and darkness to represent the demons that are living amongst the humans.

The harsh contrast between the two forms of lighting also highlights how we are supposed to feel about each group. Because the majority of the scenes in the first half of Devilman Crybaby use the bright light and simplistic style and color design, the ‘othering’ occurs when the norm gets completely changed to darkness and a more saturated animation. This change in lighting happens as the viewer starts to understand that the demons are a representation of ‘otherness’ that we deal with in the real world. As the demon's existence is revealed to the public, we see the way that paranoia leads humans to turn against each other and look for signs of ‘otherness’, punishing anyone who even remotely sticks out. Towards the end of the series, it has been made clear that the real evil in Devilman Crybaby is not the demons themselves, but those who use fear and hatred to discriminate and punish those who are perceived as different. The changes in lighting are used to better show that duality because they are so contrasting.

Another aspect of formalism that is discussed in the chapter is the idea of color and how it can be used to convey particular meaning in film. Eisenstein argues that “A color shade conveys a particular rhythm of vibration to our vision. (This is not perceived visually, but purely physiologically, because colors are distinguished from one another by the frequency of their light vibrations.)” [3] Different shades of color are thought of differently and are easily about to be distinguished physiologically by the viewer. These shades of color can be used to create different feelings that the viewer subconsciously holds about certain aspects of a show. The heightening of tension between different colors and shades, heavily influences the “dynamic of our perceptions and of the interplay of color.” [4]

Using these ideas about color that are mentioned above, we can see that Devilman Crybaby’s use of color heavily affects the way that we perceive the show. The color palette chosen for the normal, human scenes in Devilman Crybaby is somewhat muted and dull. The color that is focused on the most during these parts of the show is white. The colors are relatively low contrast and the choice of hue contributes to the simplistic feeling that the art style focuses on. Contrasting the majority of scenes involving humans, the high contrast, bright colors are used to signify the demons. Because the viewer is able to adapt to the normal color palate relatively quickly, the introduction of the bright, harsh colors during the demonic transformations comes as somewhat of a shock. The viewer is able to differentiate the scenes and who is the main focus with the use of color, and how bold it is portrayed on the screen.

Devilman Crybaby uses lighting and color to portray the ‘otherness’ that the demons represent in the series. The viewer differentiates between light and dark lighting to see how each character is viewed by the world around them and whether or not they are a part of the norm.The primarily white, low contrast colors of the human world are changed to high contrast, bright colors and dark lighting to signify the demons. The colors further exaggerate this point when you start to notice the dramatic shift made in color whenever a demon is on the screen. The animation allows for this to be done in a way that completely fits with the style. The darkness and unnatural color becomes the symbol for anything that is not considered human in the show. Anything that is ‘other’.

[1] Sergei Eisenstein,“Beyond the Shot,” Film Theory and Criticism, (2009): 14

[2] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 20

[3] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 28

[4] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 29

@theuncannyprofessoro

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Price of Freedom: Deconstructing Ideologies in Attack on Titan

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EUdSXvMVHqfWuosnvoQdS3ce24Xgza3k/view?usp=sharing

Attack on Titan (2013-2023) is an anime based on the manga of the same name by Hajime Isayama that follows main character Eren Yeager as joins humanity’s fight against what is seemingly their greatest threat: the Titans.

To understand the way power is depicted in Attack on Titan, I employ the theories of French philosopher Louis Althusser[1] and his thoughts on how structures of ideology and state apparatus assign and take power from individuals. I argue that one of the most vicious examples of ideology is depicted in later half of the show through the military’s manipulation of the Warrior Unit, and Althusser’s work “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” can be used to help explain how Marley has managed to subjugate the Eldians in Marley and use them as weapons against their enemies. Althusser believes that for a state to maintain power it must “produce” ideologies to convince its people to stay in the position that they inhabit, to maintain order. Althusser describes ideology as “our imaginary relationship to real conditions,” and states that our perception of the world around us is not exactly our experience, but ideology that tells us we are free to recognize such things. Season 4 sees an introduction to Marley, a militarized state that maintains order through force — Repressive State Apparatuses (RSAs) — and indoctrination — Ideological State Apparatuses, (ISAs). These combined forces work to subjugate and manipulate the Eldians in Marley and convince them their enemies are the “devils” of Paradis, not the state of Marley repressing them. Isayama’s dedication to detail in his worldbuilding of the “multiple worlds' ' within the show is the foundation for characters that exist in completely different positions of power which in turn, reveal more about the world and humanity itself. The change in perspective in the beginning of Season 4 of the show allows the audience to understand the themes of the show from a completely different perspective and add nuance to characters originally thought to be villains.

Season 4 of Attack on Titan introduces the audience to Marley, the oppressive and colonial empire across the ocean from Paradis, and while the nation itself is perceived to be the Eren and the Survey Corps’ enemies, the show uses the narrative of the oppressed Eldians to show the complexity behind the supposed enemy and that the question of freedom is not one so easily answered. While the audience is used to the military and political world within the walls, in Season 4 we get to understand the military workings of Marley and their struggle to maintain their power using the Titans. While other nations like the Mid-East Forces have been working on technology and weapons to surpass titan power, Marley has only been focusing on Titans as the main source of their power. Now that the rest of humanity has caught up and is now exceeding such power, Marley faces an inevitable loss. To combat this, in Episode 61 “Midnight Train” Zeke (current Beast Titan) proposes an idea to resume the operation from Season 2 to capture the Founding Titan, as that would cement Marley as the possessor of all Titan power. While Zeke is Eldian, he is considered more important to Marley’s military due to his strength as the Beast Titan and his political knowledge. What I think is interesting about Marley’s use of the Titan power is that it must rely on the exploitation of Eldians, as they are the only ones who can turn into titans. While the average non-shapeshifting Eldian lives in specific zones within Marley, if you volunteer to be a part of Marley’s military, you are treated with slightly more respect because of the value you bring to the state. While this might not directly tie to Althusser’s example of policing in his paper, it does function in the same way that it is a militarized force in that they ensure compliance from the Eldians through violence. Just for background, volunteering to be a Titan shapeshifter is not an easy choice to make. If it were, then majority of the Eldians would be. Titan power limits the users lifespan to 13 years after they have gained it, and essentially devotes the Eldian’s life to fighting for the state that has subjugated and discriminated against their people for years. Marley’s military instates order by policing the Eldians within Marley and capitalizing off Eldian’s ability to turn into weapons for their own colonial practices.

In Episode 60, titled “The Other Side of the Sea,” the audience meets the Warrior Unit, a unit of the Marlyean military group that consists of Eldians trained to inherit titans and fight for Marley’s military as they battle over land with surrounding nations. I will focus on the children who are candidates to be the apart of the next generation of the Warrior Unit, specifically Gabi. Gabi is a passionate and strong girl whose main goal is to inherit the Armored Titan from her cousin who is the current Armored Titan, Reiner Braun. We meet the Warrior candidates who are in the middle of a territorial battle with another nation, and Gabi exclaims that to win this battle would prove to Commander Magath that she is the right choice to inherit the Armored Titan. Amidst the battle, Gabi explains to her fellow, less convinced peers that, “To shoulder the fate of us Eldians…and to slaughter that island of devils who’ve done nothing but make us suffer. (5:41-5:48). Here we see the impact of Marley’s indoctrination, depicted through the word “devil” in referring to people of Eldian descent. Even though Gabi is Eldian herself, she uses the word to refer to the Eldians on Paradis, who are the characters the viewers have been following since the beginning of the show. Her hatred of the Eldians is not due to her own experiences with them, but due to the discriminatory ideology perpetuated by the Marlyean government that they use to justify their treatment of Eldians and to maintain power over them. Gabi’s dialogue throughout the show reveals the intense amounts of indoctrination she has experienced, as she feels she needs to prove to Marley that not only is she a “good Eldian” but there are other “good Eldians” out there (5:48-6:02). Here we see her dedication to excel within a militarized system that only wants her for her titan abilities, displaying how the state perpetuates its ideologies onto its citizens.

By applying Althusser’s theories of RSAs and ISAs to Marley’s military forces and practices, the audience can understand other Eldian experiences, not just the Eldians in Paradis. Marley’s indoctrination has convinced Eldians in Marley to view the Eldians in Paradis as the reason for their treatment, while the characters who were perceived to be the villains of Season 2 (Eldians from Marley masquerading as Scouts): Bertholdt, Annie and Reiner, are nuanced due to the reveal that they were essentially manipulated to begin the attack from the first episode and to betray the Scouts. Isayama’s worldbuilding and depiction of power structures not only adds nuance to characters but displays the true dangers of state power.

[1] Althusser. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation)” 9, no. 1 (2006).

@theuncannyprofessoro

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do the sisters deal with their superhero responsibilities when they also have to deal with their familial relationships? How do they support each other when needed?

@theuncannyprofessoro

The Powerpuff Girls

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

The Powerpuff Girls constructs its world through a combination of structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history. Structurally, the series adheres to the superhero genre's conventions with the trio of Blossom, Bubbles, and Buttercup representing archetypal hero figures. The cultural studies lens is evident in the show's exploration of diverse characters and themes, challenging traditional gender norms by featuring female protagonists with distinct personalities. Cultural history manifests in the series' context, reflecting the late 1990s and early 2000s ethos, contributing to the development of the Powerpuff Girls' characters, their challenges, and the dynamics within their fictional world.

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities?

The Powerpuff Girls challenges gender norms by portraying the superheroes as three powerful and capable girls, transcending traditional gender roles in the superhero genre. However, the series does not explicitly delve into racial, sexual, or cultural identities. Instead, the characters' abilities and identities are more broadly representative, emphasizing universal themes of empowerment and teamwork, thereby fostering inclusivity. The focus is on their superhero roles rather than specific identity markers, aligning with the series' commitment to a diverse and inclusive narrative.

In what ways do costumes and concealing identities further separate the superheroes from normal society? How necessary is it for the superheroes to hide their true identities to successfully achieve their goals?

Costumes and concealed identities in The Powerpuff Girls serve to separate the superheroes from normal society by creating a distinct superhero persona. Despite their childlike bodies, the girls don't wear masks like the typical superheros, but their costumes signify their superheroic roles. The necessity of hiding their true identities is tied to protecting their personal lives and maintaining a sense of normalcy within the context of their youthful appearances. By concealing their identities, the Powerpuff Girls can navigate both the challenges of superheroism and the mundane aspects of their lives without undue interference or scrutiny. The juxtaposition of their childlike appearance with their superhero responsibilities adds an additional layer of complexity to the need for identity concealment.

How do the economic, political, and social events that occurred during the series’ creation and broadcast cultivate and inform the superheroes’ decisions and actions?

Drawing insights from Kevin D. Williams's article, which explores how superhero narratives reflect societal changes, we can apply this framework to The Powerpuff Girls. The late 1990s and early 2000s, when the series was created and broadcast, were marked by significant cultural shifts. The show aligns with broader societal trends of the time, emphasizing themes of empowerment and diversity, which are likely influenced by the cultural climate of that era. For instance, the late 1990s witnessed a growing awareness of gender equality, and the Powerpuff Girls, as female superheroes, may be seen as a response to or reflection of this cultural shift. The series captures the zeitgeist of the late 20th century and early 21st century, with its characters embodying the values and aspirations of the period.

How do the superheroes question themselves, each other, and their obligations and duties to the people around them?

The series engage in self-reflection and questioning throughout the series. Despite their superpowers, they grapple with typical challenges of growing up, forming their identities, and understanding their roles as superheroes. The dynamics between the sisters involve questioning and occasional conflicts, reflecting the complexities of sibling relationships. The superheroes' obligations and duties to the people around them are generally portrayed positively, with the girls embracing their roles as protectors of their city, but occasional moments of doubt or internal conflict contribute to their character development and the overall narrative.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do the supes and humans interact in general and how much of the supes' media personalities vs actual personalities are depicted in the show? Does their natural/authentic personality come across as more human?

@theuncannyprofessoro

We Don't Need Another Superhero: The Boys (2018)

William’s assertion that TV Superheroes symbolize our ever changing “American values” is proven true by The Boys’ (2019) critical reflection of the our 21st century nation’s hierarchical distribution of economic, social, & political power, aggressive foreign policy/patriotism post 9/11, and represents the (much needed) beginnings of progressiveness through its rebellious protagonists. The show surrounds Starlight, the newest member of the Seven (America’s favorite Superheroes/“Supes” managed by Vought, an antagonistic, all-controlling company), who, after being assaulted by her childhood idol on the first night, quickly learns that the group’s heroic image is “written by the marketers.” She teams up with Hugh–our human protagonist whose fiance was murdered by a Supe–and his gang of similarly wronged (and vengeful) misfits to destroy the Seven, and eventually, Vought. The narrative frames Superheroes as the actual villains; Williams states that “with great power comes great responsibility,” but in the Boys’ speculative America, this statement is pretty unfortunate.

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

The Boys contradicts mythos of the intrinsically good Superhero by exploring the hierarchical, power-based, hegemonic underground world of the Supes, who are closer to flawed–rather than superior–humans. Homelander’s hatred of humans and the Deep’s array of sexual assaults contrasts with their publicly perfect (mythos-based) personas. In terms of cultural studies, the international influence of Vought and its Supes mirrors our unjust attribution of social power. Ezekiel–an antagonist Supe whose homophobic Catholicism contrasts with his secret homosexuality; S1 depicts him angelically floating above crowded young fans while preaching. His sex & drug-filled life is hidden from the naive public, reminding us to question the ideology presented by God-like figures in contemporary society. Superheroes’ mode of “action and conflict” is brutal, gory, in line with 21st century’s chaotic foreign policy. Well described its international standpoint as “America the Violent,” The Boys opens with A-Train literally running through Hugh’s fiance on the street, leaving the bloody protagonist to hold his girlfriend’s (cut-off) hands (the Nation, 2023). If that’s not enough, Homelander kills humans for fun. His destruction mirrors Trump’s reign–“critics say President Trump’s foreign policy has seriously undermined America’s world leadership” (the Hill). Luckily, the fight for progressiveness is represented by both Supes and humans.

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities?

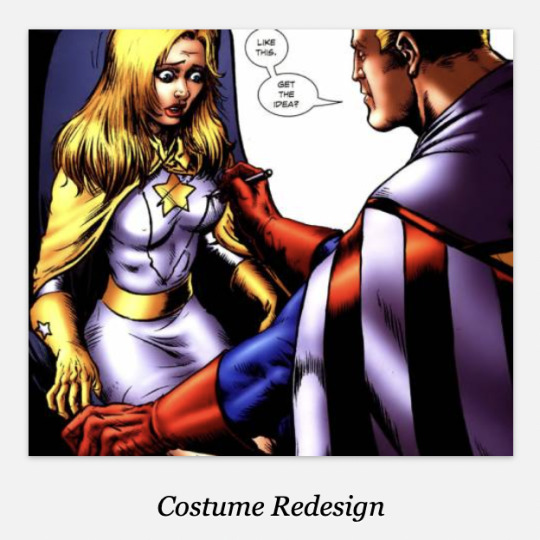

Despite Vought’s public diversity, their performativity is evident in the structural, identity-related barriers that hinder all members of the Seven (except Homelander, whose straight white identity is, uncoincidentally, the face of America). Homelander’s role in Vought’s decisions (and national power) contrasts with the company’s disregard of A-Train, a Black member of the Seven. His requests–such as an apology from Superhero Blue Hawk (a stereotyping racist who curb-stomped a Black man)--are typically ignored despite his sudden importance for #BLM marketing. Still, A-Train eventually kills Blue Hawk, framing him as stronger than the white, hegemonic structure that attempts to define him. Starlight’s entrance into the celebrity-Superhero world illustrates the struggle of gender; soon after signing her, Vought changes Starlight’s modest costume to a skimpy bikini, threatening to fire her if she doesn’t cooperate. The following scene depicts her in the bikini, men yelling to “show her boobs” in front of her young, innocent fans; gendered sexualization is framed as a barrier, overshadowing her identity as a strong Superhero. Maeve’s bisexuality sheds light on the heteronormativity of the Supe system; after years of hiding her bisexuality, heteronormative Homelander finds out and publicly outs her (in angry jealousy) as a lesbian. Vought’s binary view of sexuality results in their manipulation of this outing as a way to ‘diversify’ and profit–Maeve is marketed as the new face of lesbianism, illustrating her difficulty presenting her true Superhero identity in this binary system. Kimiko–a victim of human trafficking–illustrates intersectionality as female, Japanese, and Super; her cultural difference from the show’s world is evident throughout Season 1, when the boys attempt to ‘figure her out,’ somewhat like an unknown concept. Kimiko’s empowerment in later seasons indicates her contradiction of the hysterical, alien “Female,” and rather frames intersectionality as part of her uniquely heightened strength.

In what ways do costumes and concealing identities further separate the superheroes from normal society? How necessary is it for the superheroes to hide their true identities to successfully achieve their goals?

Costume reflects the humanity (or lack thereof) of Superheroes; Homelander is never shown without his costume on, which alludes to his lack of humanity and hatred of non-Supes. The costume represents his “real” persona while his humanity is “the facade” (1344). His “true,” villainous identity must thus be hidden in order to win the public’s affection and achieve his power-hungry goals. On the other hand, Starlight avoids costume and is framed as the most human Supe. In the first few episodes, we learn about her background through moments with Annie–her real name–while she sits at the bar, bowls, or walks through the park in ‘normal’ clothes. Still, she must hide her true identity to satisfy Vought’s hegemonic idea of success. Kimiko is never seen in costume, and is framed as the sweetest and purest Supe despite her introduction as the most alien. Her lack of interaction with the roles created by Vought (and the costumes that realize them) results in her formation of a singular identity rather than a “super” vs “normal” self like the Seven, and quickly settles into her Superhero strength.

How do the economic, political, and social events that occurred during the series’ creation and broadcast cultivate and inform the superheroes’ decisions and actions?

Superheroes’ paths are informed by economic (human trafficking), social (#MeToo, BLM), and political (terrorism, 9/11) events. Kimiko–a Japanese trafficking victim–fell into a vat of Compound V (Vought’s superhero serum) and gained unusually intense Super-strength. The economic value placed on her extreme strength results in her imprisonment as a lab rat and trafficking into the U.S. Her origin story addresses the nation’s concerning economic flow from human trafficking, pictured in relation to Compound V through Vought’s transnational trade. The #MeToo social movement affects Starlight after her sexual assault in by the Deep, a member of the Seven (E1). While the shows creators considered “behind-the-scenes” revenge narrative, they constructed Starlight’s public revenge with references to #MeToo after the movement’s coincidentally timed real-world emergence; the historical social movement shaped Starlight’s story (the Nation). “Flight 37”--a crashed plane hijacked by terrorists–is likely a political reference to 9/11. When Homelander tries–but fails–to save the plane, he simply leaves everyone to die and pretends he was never there. When the tragedy goes public, he expresses his sorrow through fake tears and a politically oriented speech; he demands the American need for real protection, specifically, Supes in the military. Homelander’s manipulation of a national tragedy to assist his right-wing agenda mirrors 21st century politics under Trump’s guidance.

How do the superheroes question themselves, each other, and their obligations and duties to the people around them?

Stan Edgar (a Vought executive) leads Homelander to question his own capability despite the Supe’s undefeated physical superiority. Edgar’s statement that Homelander is “not a God,” but “simply… bad product” results in Homelander’s atypically poor performance in a fight with Soldier Boy in the following scene (S3, the most important fight of the show). The physical manifestation of Homelander’s insecurity sheds a rare light on his humanity. His creation of an abusive workplace environment means that none of the Supes trust him, especially Maeve, as their past/media-friendly romance gives her more insight than the others. She consistently questions his intentions and thus keeps a poker face, smiling to avoid his (physically threatening) temper; her distrust shows as soon as Homelander leaves and a hidden fear replaces her fake smile. Starlight similarly distrusts and questions her obligation to remain in the Seven, and only stays to please her selfish mother. The eventual discovery that her mother selfishly injected baby Starlight with Compound V dissolves the Supe’s trust of and obligation to her mom; Starlight remains in the Seven, but for moral, personally driven reasons.

@theuncannyprofessoro #oxyspeculativetv

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

How did the animation spinoff communicate the points similar to the ones in The Boys? Do you think the stories would be just as impactful if they were live action?

@theuncannyprofessoro

The Boys: Diabolical Roundtable

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

As an intellectual property as a whole, The Boys constructs an at times scarily possible structural mythology around superheroes. Although to the public of the world they live in Vought presents the typical mythology of a powerful superhero that does anything and everything for the common good of the common person, structuring the mythology of The Seven into what we think of as a typical comic book superhero, as a viewer we are privy to what truly goes on beyond the news cameras and headline stories. The world and heroes that The Boys constructs are reflected through the cultural studies and cultural history of America through this gilded dynamic of what is presented in the media covering up what truly happened. The Boys: Diabolical hones in on this dynamic through a series of vignettes exploring what absolute power and media control can do—especially to the common person—engendering the cultural values and fears of our current time while simultaneously adding a new portrayal of literal and figurative power to our cultural understanding of it.

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities? Unlike many characters’ powers and roles in The Boys, the superpowers in Diabolical are mostly random. For the most part throughout the show, this is due to how superpowers are largely used to comedic effect, whether that be a silly power or comedic (but still gratuitous) violence. However, of the characters that appear from The Boys in Diabolical, there are two clear standouts; Homelander and Black Noir. Both were created by Vought, the ultimate conservative post-capitalist conglomerate, to play very specific roles heavily informed by their racial and gender identities. Homelander, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed white man who was essentially made in a lab to be Vought’s all-American poster boy serves as the pinnacle of a conservative pro-social message, while Black Noir, a black man who has been effectively silenced by Vought is used for his skills and abilities but is unable to speak or be his own hero.

In what ways do costumes and concealing identities further separate the superheroes from normal society? How necessary is it for the superheroes to hide their true identities to successfully achieve their goals?

Unlike many superheroes of the past, Diabolical exaggerates The Boys' distinct lack of superhero anonymity. Aside from the various stories centering around individuals' experiences with “Compound V,” almost all of the superheroes that appear in the show are not hidden behind masks but rather deliberately seeking attention from the public both to raise their “ratings” with Vought and to complete personal missions. Diabolical presents an alternative to the idea that a superhero must be a masked figure with no subjective “I” and demonstrates the grim reality of unchecked power and obsession with the “I”. Throughout the series, Diabolical asks; who needs to hide their identity when nothing can injure them in any way? Superheroes and powerful companies like Vought do anything they please in The Boys world and Diabolical dives into the personal consequences of that reality.

How do the economic, political, and social events that occurred during the series’ creation and broadcast cultivate and inform the superheroes’ decisions and actions?

Although this series of vignettes serves well as a comedic and at times lighthearted spin-off version of The Boys, there are particular episodes that explore the cultural history of the time that The Boys was originally adapted into a television series that make it such a powerful reflection of our own world. One particular episode, titled “One Plus One Equals Two,” plays strongly into the fears and anxieties of the concept of “fake news,” a concept that The Boys plays heavily on. However, Diabolical focuses less on media manipulation and more so on the personal effects that it can have on everyday people that are affected by Compound V. In one such episode, titled “Boyd 3D,” two everyday people become addicted to a temporary form of Compound V and their lives skyrocket to fame, only to fall apart just as quickly. The episode explores themes of social media selectivity and the reality behind the moments that we choose to share online with an emphasis on the corrupting effects of such power.

How do the superheroes question themselves, each other, and their obligations and duties to the people around them?

The superheroes in The Boys and Diabolical alike both question themselves, each other, and most of all their obligations constantly. Diabolical, however, has the freedom of unrelated episodes to explore more unique and inventive versions of superheroes and situations. In an episode titled “An Animated Short Where Pissed-Off Supes Kill Their Parents,” we meet dozens of superheroes who have powers that aren’t quite up to the crime-fighting task. However, because they were given those disappointing superpowers by their parents injecting them with Compound V, they were left as children at this school and abandoned by their parents. In the super world of Diabolical, superheroes are not superhumans with unquestionable morality but rather normal people who were thrust into a position of immense power in a world where morality and humanism are no longer a solid truth to stand on.

@theuncannyprofessoro #oxyspeculativetv

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think the decade changing costume and styling had an impact on the narrative of the show or do you think it was mostly for aesthetics purposes?

@theuncannyprofessoro

WandaVision (We Don't Need Another Superhero Roundtable)

youtube

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

In Avengers: Infinity War, Vision dies twice. In WandaVision it is revealed that in her grief, Wanda created a town and created a new version of Vision that can only exist within the town, even though he had died. The theme of resurrection from the dead is a popular theme in mythology. As one example, the phoenix, according to legend, is a bird with the ability to die and come back to life. It is said that when an old phoenix dies, it bursts into flames and a new phoenix is born from the ashes of the old. There are many different versions of this resurrection myth in Egypt, Europe and Asia.

WandaVision is steeped in cultural studies and cultural history. The world of WandaVision is set as a television show, so it is a television show within a show. Kevin Williams writes, “A cultural history adds the element of time to the study of the narrative’s values, namely how is the change in values over time reflected in the narrative?” WandaVision tackles cultural history by setting each of the episodes in a different time period. The first episode takes place in the 50s. Wanda and Vision are dressed and styled in 50s clothing and their home has the technology associated with the 50s and 50s-style furniture. The episode is shot in black and white like a 50s TV show. Wanda is portrayed as a typical 50s housewife and Vision is a 50s house husband with a job. The first episode they try to blend in with the 50s-style town, including at a dinner with Vision’s boss, even though they don’t have key knowledge. After interrogating Wanda and Vision, Mr. Hart chokes on his food and Vision uses his powers to save him.

In the second episode, WandaVision is transformed to a 60s setting. The show is still in black and white, but some strange items occur in color. At the end, Wanda learns she’s pregnant, she resets their reality and the show turns to color.

The third episode takes place in a 1970s setting and is in color as they prepare for the baby. The show keeps advancing through decades the 80s, 90s, 2000s until the last two episodes of the season when it breaks out of the television show model and focuses on Wanda’s real powers. The entire series is very much steeped in cultural aesthetics of the different decades as their clothing and styling change with each decade. The furniture in their home also changes with each style. Wanda and Vision attempt to blend in to each of the decades since the 50s without attracting attention even though they obviously have great powers that they can’t completely control.

youtube

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities?

Wanda’s gender identity as a woman plays an important role in her story. Ethnically, Wanda comes from Sokovia, a war-torn area that is likely modeled after Eastern Europe, possibly Yugoslavia. Her parents were killed when she was 10 and she was found by the SWORD people.

In episode 1, Wanda and her neighbor Agnes discuss techniques for seducing a man. When Vision’s boss arrives, Wanda makes a very romantic atmosphere and dresses in a fluffy white dress that is meant to seduce Vision. At the end of the episode, Wanda makes wedding rings for her and Vision. In this episode, Wanda’s role as a woman and romantic partner take center stage.

At the beginning of episode 2, after hearing thudding coming from outside, Wanda brings her and Vision’s beds closer together and then turns them into one bed. Vision tells Wanda to turn off the light, again focusing on Wanda as a romantic partner to Vision.

In episode 3, Wanda is pregnant. There seems to be a connection between the baby and her super powers. When Wanda is making the nursery, she feels the baby kicking and then loses control of her powers. Her progress moves up to six months. Vision says at the rate she’s going, they can expect the baby by Friday afternoon. When Wanda feels a tightening sensation, Vision says she’s experiencing Braxton-Hicks contractions. Her powers go haywire and there’s a town-wide blackout. Wanda wonders what will happen when the real contractions start. She wonders if the neighbors know that what’s going on is her fault. She says that people are always on the verge of discovering her secret. When Wanda has a real contraction, it begins to rain in the town. When Geraldine helps Wanda with her birth, electrical appliances turn themselves on, a chandelier crashes, pictures start spinning on the wall, and the fireplace ignites. After she gives birth, everything calms down.The show sets up a possible tension between her motherhood and her super powers, but after giving birth, she retains her powers and ultimately her children have super powers too.

More broadly, Wanda’s desire to live an idyllic life with Vision is the basis for the show. But in her determination to create this life, she is giving new identities to the people of Westview. They become characters on Wanda’s TV show and know no other lives. She in essence keeps the people of the town hostage. This relates to her identity as a woman because she is portrayed as a woman so intent on having a perfect family life with her husband and children that she will destroy the lives of others to achieve it. Wanda’s pursuit of her agenda at the expense of others is consistent with the observation by Kevin D. Williams that “As the questioning of American values and dissension within America concerning the War grew, so did the questioning of the superhero character. No longer was the superhero guaranteed to be an authoritarian do-gooder questioning nothing and blindly carrying out the crusade for American justice” (1336). Indeed, Wanda is a complex character who uses her powers for her own benefit not only to benefit others and even at the expense of others.

youtube

In what ways do costumes and concealing identities further separate the superheroes from normal society? How necessary is it for the superheroes to hide their true identities to successfully achieve their goals?

Wanda and Vision concealing their identities separates them from normal society because they have to go out of their way to make sure their neighbors don’t know what powers they have. WandaVision is consistent with Kevin D. Williams’ article “(R)Evolution of the Television Superhero: Comparing Superfriends and Justice League in Terms of Foreign Relations” when he writes, “Yet, in both series, heroes consciously struggle to maintain these secret identities, and they engage in deceit in order to keep the general public from learning their superhero status.” Wand and Vision don’t have to hide their powers when they’re alone, but in order to conceal the fact that she is a superhero who has taken over the town, without arousing suspicion from the townspeople, it is important for Wanda to conceal her and Visions’ identities.

In episode 1, when he’s at work, Vision’s boss says he’s like a computer and Vision says he’s made of organic matter. His boss then asks if there’s a skeleton in Vision’s closet. Later in the episode, Mrs. Hart almost discovers Wanda’s powers so Vision sings to distract her.

youtube

At a neighborhood watch meeting in episode 2, after being offered a danish, Vision says that he doesn’t eat food, receiving strange looks from the other characters present. To cover up his gaffe, Vision says he doesn’t eat food in between meals but at mealtimes.

In episode 3, Wanda tries to hide her pregnancy from Geraldine who arrives spontaneously. Wanda says it’s not a good time. Geraldine says she needs a bucket because her pipes burst. Wanda says she has a bucket in her kitchen. When Wanda wants to know more about Geraldine’s temp job, Geraldine goes on and on. A stork appears in the background. Wanda tries to make it disappear but her powers aren’t working. When Geraldine comments on the noise that the stork is making, Wanda says it’s her new icemaker.

In episode 5, Agnes shows up at Wanda’s door spontaneously. Vision has to quickly make himself look human because he wasn’t expecting her. Later in the episode, after Wanda tells the twins that taking care of a dog is a huge responsibility, Vision shows up. He looks human. He says he had a hunch someone would pop over. This is when Agnes shows up with a wooden house for the dog, and Vision continues his speech with “with exactly the item we require.” Wanda uses her magic to create a dog collar in front of Agnes. Vision doesn’t understand why. Wanda says that Agnes didn’t notice when the twins aged up from babies to five-year-olds. Vision says it’s not what they agreed upon. He says that Wanda made no effort to conceal her abilities. Wanda says she’s tired of hiding and that Vision doesn’t have to either.

Kevin Williams also writes that Justice League gives an opposing interpretation: the costume is the real character and a secret identity is the false secondary identity. This is true in the case of Wanda, who invented fake personas for her, Vision, and everyone in Westview. She pretends she doesn’t know her true powers, but she actually does, which is seen in episode 3, when she ejects Monica Rambeau out of the town and back into the real world using her powers and then fixes up the damage.

youtube

This quote can also be applied to the character of Agnes, who seems to just be Wanda’s neighbor and oblivious to Wanda’s power, but who later reveals herself to be a witch named Agatha Harkness at the end of episode 7. She was concealing her true identity and was just biding time before she revealed herself.

youtube

How do the economic, political, and social events that occurred during the series’ creation and broadcast cultivate and inform the superheroes’ decisions and actions?

Production of WandaVision began in 2019. During this year, Brexit occurred, President Trump was impeached, evidence for global warming became more clear as the Amazon rainforest burned an area the size of New Jersey, and protestors were in the streets in Hong Kong. Against this backdrop of national and global turmoil, the focus of WandaVision on a seemingly simpler, nostalgic past of sitcoms can be understood as an approach to escape from the threats of reality. During production, a new threat to civilization, the pandemic occurred. Production had to be halted in 2020 for the pandemic. It was completed later that year and WandaVision became one of the few shows that aired in 2021, the height of the pandemic. The longing for escapism through sitcoms and television during the pandemic may well have contributed to the success of the television show. Wanda keeping everyone in a contained bubble could have been an allusion to people having to isolate themselves during the pandemic. Further, the attention paid to TV sitcoms is on the one hand comforting and nostalgic. But the show captures the emotions of the pandemic-stricken world because it upended the calming notion of an unthreatening sitcom and instead turned it slowly but steadily into a scarier and creepier show with each episode nudging in the direction of sitcom turning to horror, similar to life in a pandemic.

How do the superheroes question themselves, each other, and their obligations and duties to the people around them?

In episode 8, Wanda and Agatha question each other. Agatha begs Wanda to reveal how she created the Hex and has Wanda revisit traumatic times from her life. When Wanda reveals how she created the town, Agatha says she knows what Wanda is. Agatha says that Wanda used chaos magic to create the town and that makes her the Scarlet Witch.

youtube

In episode 9, Agatha wants Wanda to surrender her power to her. Agatha says she’ll let Wanda “keep this pathetic little corner of the world all to herself.” Wanda throws her car into Agatha’s house. This is when the new Vision shows up. He lifts Wanda into the air and squeezes her head and says he was told that she was powerful, indicating that he believes that to be false. This is when the real Vision appears and throws the new Vision, which causes an explosion. Wanda says she should’ve told Vision everything the moment she realized what she had done. Vision says he understands why she made the world, but shows concern about it. Wanda says she can fix it. Vision seems doubtful. The new Vision emerges from the flames. Wanda tells Vision that Westview is their home and he says they will fight for it. When Vision and the new Vision fight again, Vision asks why Vision 2 is bent on destroying him. Vision 2 says that Wanda must be neutralized and Vision must be destroyed, and punches Vision in the head. Later, when Wanda is in the street, Agatha sends out a purple blast. She says that Wanda has never been up against another witch before. She says there’s an entire chapter devoted to Wanda in the Darkhold, which is the Book of the Damned. She says that the Scarlet Witch is not born, she is forged. She has no coven and no need for incantation. Wanda says that she’s not a witch, that she doesn’t cast spells, and that no one taught her magic. Agatha says that Wanda’s power exceeds that of the Sorcerer Supreme. She says it’s Wanda’s destiny to destroy the world. Wanda says she’s not what Agatha says she is.

youtube

Soon after this, Agatha cuts off Wanda’s control of the townsfolk. Wanda tells the townsfolk that they’re going to be fine, that she’s kept them safe. The townsfolk say that they feel her pain. Wanda lets out a scream, and accidentally starts choking the townsfolk. After stopping it, Wanda says she’ll let the people go. Agatha asks what’s stopping her. She tells Wanda to let the people go now and that heroes don’t torture people. Wanda sends up a beacon that is changing the town back to the way it was before she changed things. She tells everyone to leave. Vision then falls to the ground and begins to fall apart, as do the twins. Agatha informs Wanda that she tied her family to the twisted world and now one can’t exist without the other. Wanda puts the shield back up and Agatha blasts Wanda and her family. Wanda puts up a protective shield around them.

In the library, Vision says that he does not have one single ounce of original material. He says that Vision 2 has the data but his memories are being kept from him, and he no longer feels like the real Vision after meeting Vision 2. He says that Vision 2’s memory storage is not so easily wiped and unlocks it, causing Vision 2 to say that he is Vision, at which point he blasts through the roof.

Wanda brings Agatha to the past and shows Agatha the destruction she caused. Wanda says the difference between the two of them is that Agatha did it on purpose. Agatha reanimates the dead witches, who chant Wanda’s name. They say that she’s the Scarlet Witch, the Harbinger of Chaos. Agatha says Wanda can’t win, and says that power isn’t the problem. It’s knowledge. Agatha tells Wanda to give her her power and she will correct the flaws in Wanda’s original spell. She says that Wanda and her family and the people of Westview can all live together in peace. No one will have to feel Wanda’s pain again, not even Wanda herself. Wanda tells Agatha to take the power, that she doesn’t want it. Agatha says she wants all the power and Wanda tries to give it to her. Agatha then says that once a spell is cast, it can never be changed. The world Wanda made will always be broken, just like her. Agatha tries to blast Wanda but fails. Wanda reveals the runes she made, which means she’s the only one who can use her powers. She thanks Agatha for the lesson. She says she doesn’t need Agatha to tell her who she is and then transforms into the Scarlet Witch.

youtube

Wanda tells Agatha that she’s going to lock Agatha in Westview in the role she chose; the nosy neighbor. Agatha says Wanda has no idea what she unlocked and that she’s going to need her. Wanda says she knows where to find Agatha and turns Agatha into the nosy neighbor.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

How was your experience watching the show after growing up with it?

@theuncannyprofessoro

Superheroes Roundtable: Wordgirl

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

Wordgirl (PBS) represents a cultural shift towards the prioritization and valuing of literacy and education for young girls. When the show premiered in 2007, there were not many kids' superhero shows that featured female protagonists. This issue still persists today in both child and adult media. Not only does Wordgirl feature a young female protagonist, but her superpowers subvert traditional expectations of violence and fighting. To platform spelling and literacy as “powers” is to highlight the value of these abilities in our society.

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities?

It is interesting to consider this question in relation to Wordgirl’s character because while her gender is platformed and even included in the name of the series, her racial identity is purposefully abstracted and blurred. While Wordgirl is technically from the planet Lexicon, and thus is not affiliated with any known race or ethnicity, she has light brown skin and thus could arguably resemble/represent multiple different races. As a young woman of color, usually facing off against male-presenting adversaries, her identity never hinders her ability to defeat her enemies with her impressive vocabulary.

In what ways do costumes and concealing identities further separate the superheroes from normal society? How necessary is it for the superheroes to hide their true identities to successfully achieve their goals?

While I think in traditional superhero narratives, concealing identity is very necessary in ensuring the safety of the character in their day to day lives, I would argue that Wordgirl plays off of this trope and even satirizes it. Her disguise is a cape and a mask that covers just her eyes, and most of her enemies interact with her regularly when she is not in her superhero costume. It is very clear who her real identity is, however the show has her wear the cape and mask to call attention to these tropes and solidify its place as a less serious yet no less important superhero text.

How do the economic, political, and social events that occurred during the series’ creation and broadcast cultivate and inform the superheroes’ decisions and actions?

Besides the political relevancy discussed in question #1, individual epsidoes of the show sometimes mirror socio-political events. For example, an episode aired in 2009 in which one of Wordgirl’s recurring enemies, Toby, runs for president. Given that the episode aired the year following the 2008 presidential election, it is clear that the showmakers sometimes wanted to feature topics that were especially culturally and politically relevant.

How do the superheroes question themselves, each other, and their obligations and duties to the people around them?

The show picks up after Wordgirl has already decided that she wants to use her powers to save people and catch criminals. Because she is self assured and confident in her role and the way to harness her powers for good, an internal struggle surrounding her obligations does not have a place in the show. She fights crime and teaches villains how to spell not out of obligation but out of a desire to do so, which I think is a valuable type of empowerment to show in a series for kids.

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was your reaction to having Supergirl be framed as a damsel in distress throughout the show? Did this impact your viewing experience or confuse the supposedly feminist narrative?

@theuncannyprofessoro

Roundtable Presentation: We Don't Need Another Superhero

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

Supergirl’s true identity is Kara Zor-El, with her earth name being Kara Danvers. The show takes place in National City, and besides this world’s advanced technology and interaction with the extraterrestrial, it reflects a world much like ours. The politics of this world is similar in the sense that there are “anti-alien” political groups that lead the aliens of this world to find refuge in their own bars, neighborhoods, etc. In fact, Kara’s best friend, Lena Luthor, develops a piece of technology meant to identify who in a crowd is alien and who is not, a severe form of othering.

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities?

One of the main challenges for Supergirl is coming to terms with her identity and finding space for herself in a world dominated by male superheroes, specifically her cousin, Superman (aka Clark Kent). During the destruction of their planet, a teenage Kara is sent to earth to protect baby Clark. However, Kara arrives on earth much later than Superman because she ended up trapped in the Phantom Zone, a dimension of space where time doesn’t exist. Thus, although Kara is older, Clark is already an adult while Kara is growing up with her adoptive family. In a world where a male superhero with identical powers is established, Supergirl has to work twice as hard to make sure she isn’t just known as “Superman’s cousin.”