Production company blending classic cinema, timeless storytelling, and modern film-noir for today’s audience.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

🎬 Just Before Dawn (1946): Noir in a White Coat

🕯️ Murder, deception, and a doctor with everything to lose…

youtube

Watch free on YouTube: Just Before Dawn – Cinema Coded

A man dies after receiving his routine insulin shot. Then another. And another. All roads lead back to Dr. Robert Ordway, a respected physician now framed for a string of murders in this chilling, forgotten gem from the postwar noir era.

Just Before Dawn is the sixth installment of Columbia’s Crime Doctor series, but don’t let that fool you—it plays like a full-fledged noir. Warner Baxter leads with stoic dread, navigating a world of dimly lit clinics, hostile investigations, and whispered betrayals. Martin Kosleck’s eerie presence deepens the unease, suggesting unseen forces working behind every shadow.

Shot in razor-sharp black-and-white, the film’s cinematography leans hard into classic noir technique: venetian blinds cast prison-bar shadows, sterile rooms feel like traps, and every frame is thick with tension. Though filmed on soundstages, the anonymous American city it depicts becomes a landscape of suspicion and decay—typical of 1946, when public trust in science, authority, and postwar normalcy was rapidly unraveling.

With a brisk 65-minute runtime, Just Before Dawn wastes no time. It’s compact, tightly written, and expertly paced. The fear isn’t just who’s next—but how deep the betrayal runs.

📽️ Perfect for fans of vintage thrillers, medical suspense, and noir that cuts with surgical precision.

#JustBeforeDawn#FilmNoir#WarnerBaxter#ClassicCinema#MurderMystery#1940sFilm#PostwarParanoia#MartinKosleck#WilliamCastle#CinematographyMatters#1940sMovies#CinemaCoded#NoirVibes#VintageThriller#PostwarCinema#Youtube

0 notes

Text

John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966): A Surreal Noir of Second Chances

A Faustian Plot of Second Chances

Seconds is a 1966 science fiction-tinged psychological thriller with a premise straight out of a twisted fable.

It follows Arthur Hamilton (played by John Randolph), a middle-aged banker whose comfortable suburban life has left him deeply unfulfilled.

Approached by a mysterious organization known only as "the Company," Arthur is offered an illicit chance at rebirth: they will fake his death and surgically transform him into a younger man with a brand-new identity.

Desperate to escape his stifling existence, Arthur agrees. He emerges from radical plastic surgery as Tony Wilson (Rock Hudson), a handsome and ostensibly free-spirited artist living in Malibu.

At first, this Faustian bargain seems to promise the youth and freedom Arthur craved – he’s given a beach house, a new career as a painter, and even a romantic interest. But as Tony Wilson tries to navigate his second life, he finds the fresh start isn’t the paradise he imagined.

Adjusting to an invented identity proves harrowing: Tony is plagued by loneliness, disorientation, and creeping paranoia about the Company’s grip on his life. By the film’s end, the story turns dark and tragic, as Arthur/Tony discovers that some deals with the devil cannot be undone.

This brief plot setup sets the stage for a haunting exploration of identity and regret, giving context to the film’s bold stylistic choices in cinematography and performance.

James Wong Howe’s Experimental Cinematography

Cinematographer James Wong Howe’s work on Seconds is nothing short of astonishing – a visual tour de force that mirrors the film’s unsettling mood.

Frankenheimer and Howe craft a strikingly surreal look using every tool at their disposal, from bizarre lens choices to inventive camera movement. In fact, Seconds “looks like a Twilight Zone episode directed by Jean-Luc Godard,” blending an eerie Rod Serling–style tone with bold New Wave techniquestheasc.com.

The result is a film that feels as disorienting and claustrophobic as its protagonist’s mindset.

*Notable cinematographic techniques in Seconds include:

Extreme Wide-Angle Lenses & Deep Focus: Howe frequently employs very wide-angle lenses (as extreme as a 9.7mm fish-eye) that bend and distort the image, keeping foreground and background in unnervingly sharp focustheasc.comcriterion.com. These lenses were even strapped to actors for tracking shotscinema.ucla.edu, pulling us uncomfortably close to their perspective. The effect is often claustrophobic – walls and faces bulge toward the camera, conveying Arthur’s world closing in on him.

In the harrowing climax, for example, Tony (Rock Hudson) is strapped to a gurney as the camera – mounted right on the gurney with a wide lens – hovers inches from his panicked facetheasc.com. The surroundings warp inwards around him, visually trapping the character and inducing a visceral anxiety in the viewer. This kind of deep-focus, ultra-wide imagery was a Howe hallmark (he had pioneered it as early as Transatlantic in 1931criterion.com), but in Seconds he pushes it to an expressionistic extreme.

Extreme Close-Ups and Distortion: Even from the opening credits, Seconds announces its surreal style. Famed graphic designer Saul Bass created an unsettling title sequence featuring grotesque extreme close-ups of a face (presumably Arthur’s) twisting and contorting behind bold white typographytheasc.com. These nightmarish images were achieved in-camera with macro lenses and a flexible mirrored surface, literally warping the human visage. Throughout the film, Howe continues to use tight close-ups – often with wide lenses – that exaggerate facial features and make the viewer share in the characters’ discomfort. It’s an invasion of personal space: pores, sweat, and fear are magnified on the big screen, reflecting the intimacy of Arthur’s terror. One memorable shot shows Hudson’s eye in massive close-up, dilating with dread, evoking classic noir and horror iconography of a man witnessing his own doom.

High-Contrast Lighting (Chiaroscuro Noir Style): Although made in the mid-1960s, Seconds was shot in black-and-white – deliberately so, even as color had become the normlatimes.com. This choice allows Howe to paint with stark light and shadow, recalling the look of classic film noir. Interiors are cloaked in deep shadows and hard lighting, heightening the sense of moral ambiguity and dread. Howe, known as “Low-Key” Howe for his mastery of moody lightingnofilmschool.com, uses harsh key lights to carve striking contrasts on faces and sets. In the Company’s secret operating room and offices, the high-contrast lighting makes the space feel ominous and otherworldly – figures often appear in silhouette or half-lit, as if hiding secrets. This noir-like visual palette reinforces the film’s dark themes and keeps the atmosphere relentlessly tense.

Unconventional Camera Movement and Angles: Further amplifying the disorientation, Frankenheimer and Howe frequently shot with handheld cameras and odd angles. Some scenes were captured cinéma vérité style with multiple handheld Arriflex cameras rolling simultaneouslytheasc.com, a technique inspired by the frenetic energy of the French New Wave. For instance, an early sequence follows Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) on a busy commuter train: the camera jostles and jump-cuts from his anxious face to the rushing scenery outside, in a frenzy of motion that mirrors his inner agitationtheasc.com. In another scene, a drunken Tony hosts a cocktail party and begins to crack under the strain of his new identity – Frankenheimer actually had Rock Hudson consume real alcohol for raw effect, and four cameras roamed the party to capture the chaos in one taketheasc.comtheasc.com. The result is a feeling of uncontrolled, spiral descent. Additionally, many shots use canted (tilted) angles or place the camera in bizarre positions (even hidden inside objects in public scenestheasc.com) to keep the viewer unsettled. This dynamic camerawork, combined with the distorted optics, makes the film visually synonymous with anxiety.

All of these techniques coalesce to give Seconds a singular look that is both dreamlike and nightmarish.

The collaboration between Howe and art director Ted Haworth was crucial – sets were designed with forced perspectives and funhouse geometry to further warp the visualstheasc.comtheasc.com. In one hallucination sequence, Tony finds himself in a bizarre bedroom with skewed walls and a rolling checkerboard floor; Howe’s camera captures it in wide angle, transforming the room into a Kafkaesque nightmare realmtheasc.com.

The filmmakers even shot much of Seconds as a “silent” film, recording no live sound (because the cameras were so close to the actors that the noise would be overwhelming)theasc.com.

Dialogue and sound were looped in later, which gave Howe and Frankenheimer the freedom to prioritize striking visuals above all. As Frankenheimer quipped during production, “I believe that we are in the movie business, not the sound business. It’s the screen image that is important”theasc.com.

Indeed, in Seconds the image is everything – it tells the story of psychological torment in a way that words never could. The overall effect is “haunting” and “otherworldly”cinema.ucla.edu, placing the viewer directly in a state of surreal dislocation.

Howe’s Vision in Seconds vs. Other Films

James Wong Howe was already a legend in cinematography by 1966, renowned for his technical innovation and artistry across genres. However, Seconds stands out even in Howe’s illustrious career for its bold experimental style.

Many of the visual techniques in Seconds had roots in Howe’s earlier work – he was using deep focus and wide lenses decades before, even famously employing them in the 1930s. In fact, his use of deep-focus, wide-angle compositions in Transatlantic (1931) “presaged Gregg Toland’s work on Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane ten years later”criterion.com.

Throughout the ’40s and ’50s, Howe proved extremely versatile: he glided on roller skates with a hand-held camera to film a boxing match in Body and Soul (1947)criterion.com, and he won an Oscar for the naturalistic black-and-white cinematography of Hud (1963).

He was also behind the shadowy city visuals of Sweet Smell of Success (1957), where his “etching with shadow” gave New York a “crisp, threatening, noir-like” hardnesscinema.ucla.edu, and his mastery of deep focus made cramped interiors feel three-dimensionalcinema.ucla.edu.

Clearly, Howe was no stranger to high-contrast lighting or noir aesthetics.

What makes Seconds unique among Howe’s films is the sheer extremity of its techniques and how directly they serve the story’s psychological intensity.

While earlier projects showed Howe’s capacity for innovation (deep focus, wide angles, etc.), Seconds is a virtual showcase of his inventive versatilitycriterion.com.

The film allowed Howe to combine methods in unprecedented ways: body-mounted cameras, bizarrely exaggerated lens distortion, and a blend of documentary-style spontaneity with expressionist lighting.

Few of Howe’s previous films had pushed the visual storytelling to such a hallucinatory level. It’s as if all his ingenuity was unleashed to capture one man’s unraveling sense of self.

The difference is evident when comparing Seconds to a classic like Sweet Smell of Success: both are in stark black-and-white, but Sweet Smell’s style, though stylishly noir, remains grounded in realism, whereas Seconds dives headlong into surreal, subjective imagery.

Even within Frankenheimer’s own body of work, Seconds is distinctive – the director’s earlier thrillers (The Manchurian Candidate, Seven Days in May) are tense and stylish but still relatively conventional in camerawork.

In Seconds, Frankenheimer and Howe together take a daring leap, adopting techniques that in 1966 were more commonly associated with avant-garde European cinema than Hollywood. It’s no surprise that the film initially puzzled audiences; as one commentator noted, upon its premiere at Cannes it was “booed by the audience” for being too avant-garde and ahead of its timecinemaretro.com.

Today, however, Seconds is rightly celebrated as a cult classic – a film where a master cinematographer stretched the medium to new limits in service of a daring vision.

Performances: Rock Hudson and John Randolph as a Shattered Self

The performances in Seconds provide the vital human core to this technical tour de force. In an inspired casting against type, Rock Hudson – then known mostly for his charming roles in romantic comedies and dramas – takes on the role of Tony Wilson, the reborn younger version of the protagonist.

Hudson delivers what many consider the finest performance of his career, portraying a man who “runs the gamut of emotions from deep depression to pure elation to outright terror”cinemaretro.com. It’s a startling and deeply affecting turn: Hudson uses his matinee-idol presence in an ironic way, often hollowing out his usual confident demeanor to reveal Tony’s inner desperation.

In scenes where Tony is alone, grappling with regret, Hudson’s face carries a haunting emptiness – a sense that despite his handsome new exterior, the soul inside is lost and aching.

As the story progresses and Tony’s paranoia mounts, Hudson ratchets up the intensity. By the final act, when Tony realizes the horrific fate that awaits him, Hudson’s frantic, fear-stricken performance is downright harrowing.

The famous gurney sequence (captured in distorted close-up) is powered not only by Howe’s camera but by the look of abject panic in Hudson’s eyes and the trembling in his voice. This melding of actor and cinematography sells the emotional truth of the moment in a way that leaves the viewer rattled.

Equally important is veteran actor John Randolph, who portrays Arthur Hamilton in the film’s opening act. Though Randolph has less screen time than Hudson, he crucially establishes Arthur’s melancholy and dissatisfaction, which linger over the rest of the story.

With slumped shoulders and a weary, distant look, Randolph personifies the empty shell of a man who has everything society promised (a stable job, a home, a family) yet feels dead inside. His subdued, haunting performance in these early scenes earns our empathy – we understand why Arthur is tempted to throw his life away for a new one.

That empathy carries over when Hudson takes the baton as the same character in a new body. Notably, Randolph and Hudson never share the screen (they are literally the “before” and “after” of one man), but there is a spiritual continuity in their performances. Hudson maintains subtle echoes of Randolph’s sadness even as Tony initially tries to embrace hedonistic pleasures.

When Tony, in a moment of weakness, revisits his old life incognito and stands in the shadows watching his former wife, Hudson conveys Arthur’s heartbreak purely through body language – a slumped posture not unlike Randolph’s and a face clouded with longing and remorse. In that moment, the two actors feel eerily united as one tragic figure split in two.

It’s also worth noting the film’s intriguing supporting cast. Character actors like Will Geer and Jeff Corey appear as shadowy Company men, and both (like Randolph himself) were actors who had been blacklisted in Hollywood during the 1950s.

Their casting lends an extra-textual resonance – these performers knew something about having their identities and careers stripped away, and their presence reinforces the film’s themes of loss and disillusionment. But ultimately it’s Hudson and Randolph who anchor the film’s emotional and psychological tension.

Their dual performance makes us believe in Arthur/Tony as a single tortured soul. This is why, for all of Seconds’ flashy visual bravura, the film hits us at a gut level – we are invested in this man’s nightmare, right up to the devastating final frame.

Noir Themes: Identity Crisis, Paranoia, and Moral Ambiguity

While Seconds is often classified as a science-fiction thriller, it in many ways plays like a modern film noir. It takes the classic elements of noir – a disillusioned protagonist, a sense of paranoia, moral ambiguity, and striking visual style – and filters them through a 1960s lens of surreal psychological horror. Here are some key noir-like elements that define Seconds:

Identity Crisis: Noir has long been fascinated with questions of identity (think of films like Dark Passage (1947), where a man undergoes plastic surgery to escape the law, or Vertigo (1958), with its obsessions over changing identities). Seconds builds its entire narrative around an identity crisis. Arthur Hamilton literally becomes someone else, only to find that changing one’s face doesn’t change the person within. This nightmare of lost identity is the film’s driving force. The protagonist is a classic noir figure in that he’s fundamentally alienated – first from his old life, then from his new one. In true noir fashion, the attempt to reinvent himself leads not to freedom but to existential despair. By the end, Arthur/Tony realizes he no longer belongs anywhere: he’s a man with no identity at all, a victim of his own misguided choices.

Paranoia and Conspiracy: Seconds radiates an atmosphere of paranoia that would make any 1940s noir proud. From the moment Arthur contacts the Company, he steps into a shadowy underworld where no one is fully trustworthy. The Company itself is a secretive, sinister operation, and as Tony Wilson, he discovers that even his newfound friends and neighbors may be in on the conspiracy. In one suspenseful sequence, Tony hosts a cocktail party and, after drinking heavily, lets slip hints of his former life – he then realizes with horror that several party guests are actually Company plants keeping tabs on him. This revelation (and the sudden hostility of those guests) sends Tony spiraling into fear. The film’s second half is suffused with the anxiety that the invisible eyes of the Company are always watching. This paranoia is very much in the tradition of noir protagonists who feel the walls closing in. Director John Frankenheimer was known for his Cold War-era thrillers about conspiracies (The Manchurian Candidate being a prime example), and in Seconds he brings that same sense of oppressive surveillance and dread to a deeply personal story. By the final act, Tony is literally on the run within the Company’s labyrinth, a trapped man not unlike a classic noir fall guy hunted by forces he underestimated.

Moral Ambiguity and Fatalism: True to noir, Seconds operates in shades of gray rather than black and white (despite its monochrome cinematography!). Arthur’s decision to abandon his wife and old life is ethically troubling – it’s both selfish and pitiable. The Company’s services themselves raise moral questions: they exploit unhappy men’s desires for a profit, essentially selling false hope. There are no traditional “good guys” here; even our protagonist is complicit in a lie. As the story unfolds, a grim fatalism takes hold, another noir hallmark. Arthur/Tony’s attempt at rebirth seems doomed from the start by his own inner demons, and the Company’s machinations seal his fate. The tone of the film grows increasingly nihilistic, driving home that actions have irrevocable consequences. The ending (which won’t be spoiled in detail here) is as bleak as any noir finale from the 1940s – it carries a sense of inevitable doom, the result of the character’s tragic flaw (his inability to find contentment within himself). This moral bleakness is amplified by the film’s visuals: Howe’s stark lighting often casts literal darkness over characters at crucial moments, symbolizing the encroaching doom. In Seconds, as in classic noir, the American Dream has curdled into a nightmare, and our protagonist cannot escape the trap of his own making.

Visual and Aesthetic Parallels to Noir: Finally, Seconds shares with noir a distinctive visual language. As discussed, the black-and-white high-contrast cinematography and heavy use of shadows immediately evoke the noir style of the ’40s and ’50s. There’s a sequence in the Company’s offices – a long, sterile corridor leading to an operating room – that feels like a nightmare version of an insurance office out of Double Indemnity, all deep shadows and vanishing perspectives. The use of unusual angles and distorted reflections at times recalls the expressionistic touches of films like The Lady from Shanghai (1947) or Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958), which used wide-angle lenses to similar dizzying effect. Yet Seconds pushes these ideas into even more surreal territory, bordering on horror. It’s film noir meets Kafka, where the visual style doesn’t just set a mood but actively distorts reality. This fusion of noir and horror was quite ahead of its time, prefiguring the neo-noir and psychological thrillers that would become popular in the 1970s and beyond.

By weaving these noir elements into its science-fiction premise, Seconds creates a unique hybrid: part morality tale, part paranoia thriller, part identity-crisis noir. The film asks classic noir questions – Who am I? What have I become? – and answers them in the most unsettling ways.

Style, Narrative, and Theme in Harmony

One of the reasons Seconds endures as a favorite among classic film buffs and cinematographers alike is how perfectly its style, narrative, and themes complement each other.

Every stylistic choice serves the story’s central idea: the terror of getting exactly what you wished for.

The cinematography, for instance, isn’t just flashy for its own sake – it allows us to inhabit the protagonist’s disoriented mind. When the image bends and blurs, it’s as if Arthur’s very sense of self is warping.

The deep-focus wide shots keep reminding us that no matter where Tony goes, he can’t escape the reality of his situation; the world around him is inescapably present, pressing in on him from all sidestheasc.com.

Likewise, those invasive close-ups confront us with the characters’ raw emotions, laying their souls bare. It’s no accident that we often see Tony’s face in fragmented reflections (in mirrors, windows, etc.) – visually, the film is constantly mirroring his fractured identity.

Narratively, the film’s structure (moving from Arthur’s dour life to Tony’s seemingly liberated existence and then into mounting dread) is mirrored by the visual progression. In the early scenes, the camera often keeps its distance, observing Arthur’s life with a slow, suffocating stillness.

As soon as he becomes Tony, the camera becomes more playful and alive – at first, there are moments of almost lyrical freedom (the California beach, an outdoor Bacchus wine festival shot with an unhinged, “liberated” camera eyetheasc.com).

But as Tony’s psychological state deteriorates, the visuals turn chaotic and terrifying again, culminating in the jagged, horror-tinged finale. This alignment of form and content means the audience not only understands Tony’s journey intellectually but feels it viscerally.

By the time the film reaches its climax, style and narrative have fused into one: the story’s fear is in the lighting, in the composition, in the very motion of the camera. It’s a powerful example of cinematic synergy.

Thematically, Seconds explores the allure and folly of escaping one’s identity, and every aspect of the film reinforces that theme. The performances underline the human cost of this folly – through Randolph and Hudson’s work, we see that identity is not something you can just shed like old clothing.

The cinematography, with its distorted mirrors and double images, constantly poses the question: Can you ever really become someone else, or are you forever haunted by yourself? Even the production design – the maze-like corridors of the Company, the distorted sets – externalizes the theme that attempting to carve out a new identity can be a labyrinthine, losing game.

And Jerry Goldsmith’s eerie score, along with the sound design, adds an auditory layer of tension that complements Howe’s visuals (interestingly, much of the dialogue and sound were added in post-production, allowing the filmmakers to heighten every heartbeat, footstep, and whisper to enhance the mood).

In drawing connections between Seconds and other works, one finds that it sits at an intersection of influences yet creates something wholly its own. It channels the soulful dread of classic film noir, the visual daring of European art cinema, and the cautionary bite of a Twilight Zone-style morality tale, all wrapped in a distinctly 1960s concern about identity and conformity.

Some have compared Seconds to the legend of Faust (as the Rotten Tomatoes consensus cleverly notes, it’s a “paranoid take on the legend of Faust”rottentomatoes.com) – like Faust, Arthur sells his soul (or in this case, his identity) for youth and gets hellish consequences. The film’s noir aesthetics make that modern Faust story feel like an ages-old nightmare filmed through a fisheye lens.

For fans of classic Hollywood and film noir, Seconds offers a thrilling bridge between eras – it carries the DNA of the noir tradition into the radical stylistic experimentation of the 1960s. And for students of cinematography, it remains a touchstone, displaying James Wong Howe’s genius in full force.

Roger Deakins, one of today’s most esteemed cinematographers, even remarked that with all modern technology, “there is no one who can match James Wong Howe’s ability to control light in the service of the story”criterion.com.

Seconds is a prime example of that credo: every lighting decision, every camera trick is in service of the story’s emotional truth.

In the end, Seconds is an unforgettable synthesis of style and substance. It takes a deeply unsettling narrative about losing oneself, and elevates it with imagery that sears itself into the mind. The film’s claustrophobic, high-contrast visuals and intense performances work in tandem to pull the viewer into a nightmare that is at once surreal and all too human.

For classic film enthusiasts, Seconds is a gem worth (re)discovering – a bold experiment from the twilight of old Hollywood that still feels fresh, scary, and profoundly poignant. As the camera’s eye closes in for that final, chilling shot, we’re left marveling at how perfectly Howe’s cinematography, Frankenheimer’s direction, and the cast’s commitment have converged.

Nearly six decades later, Seconds hasn’t aged; it remains suspended in time, a haunting black-and-white memory of a dream – or perhaps a nightmare – that refuses to fade away.

Sources: John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (Paramount, 1966); American Cinematographer retrospectivetheasc.comtheasc.comtheasc.com; UCLA Film & Television Archive notescinema.ucla.edu; Criterion Collection essay by David Hudsoncriterion.com; Cinema Retro reviewcinemaretro.com; Rotten Tomatoes consensusrottentomatoes.com.

#FilmNoir#Seconds1966#RockHudson#JohnFrankenheimer#JamesWongHowe#ClassicFilm#Cinematography#BlackAndWhiteCinema#PsychologicalThriller#CultClassic#VisualStorytelling#FilmAnalysis#NoirAesthetic#HollywoodGoldenAge#SurrealCinema

0 notes

Text

Back Cover Blurb – Refined & Elevated

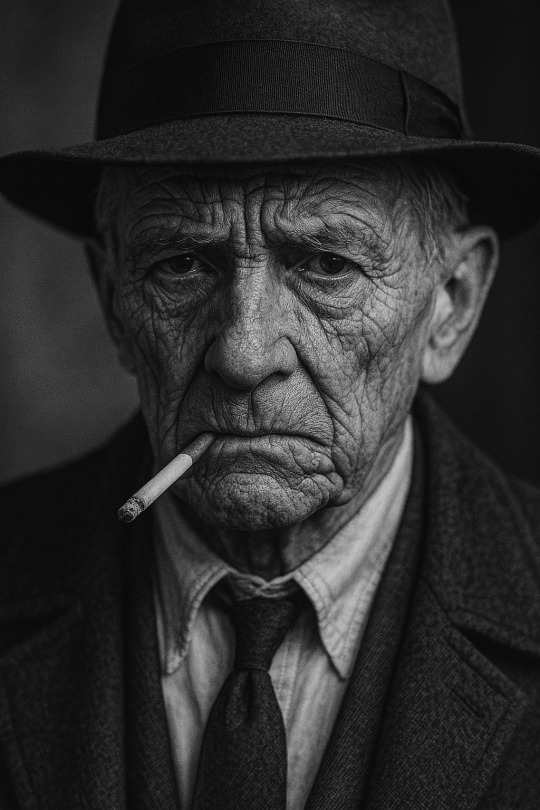

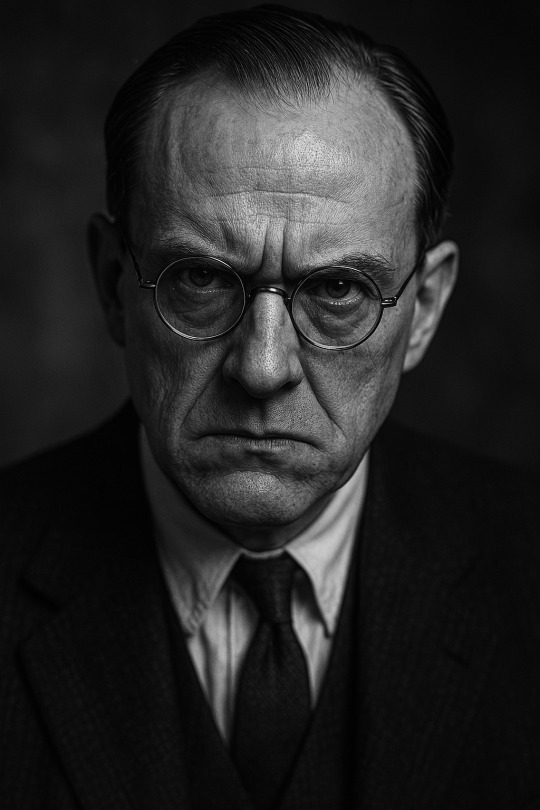

The city doesn’t sleep. It watches. It remembers. And now… it judges.

Detective Cal Harrow knows every crack in the pavement, every lie behind a smile. He walks with ghosts, talks to shadows, and trusts no one — not since the case that broke him. He’s chasing a man no one sees, but everyone fears.

Dr. Ellis Crane once spoke in lecture halls; now his words move through courtrooms, boardrooms, and crime scenes. His face rarely appears — but his signature is written in ruin. From behind polished lenses and locked doors, he engineers the world to his will.

One man clings to justice like a last cigarette. The other feeds on order like a god with a grudge.

Both are fractured. Both are fatal.

As buried sins claw their way back to the surface, the line between hunter and hunted disappears into the smoke.

Only one will write the final chapter. Only one will step out of the shadows.

The Man Behind the Mirror A Smither Scenes Production Where the past always finds its way home.

#NoirDetective#FilmNoir#ModernNoir#GritAndShadow#SmitherScenes#BlackAndWhiteCinema#NeoNoirVibes#HardboiledHero#CinematicMood#NoirRevival

0 notes

Video

youtube

What is Film Noir – Private Detectives, Corrupt Cops, and Femme Fatales

Film noir, a genre that emerged in the early 1940s, has captivated audiences with its dark, moody aesthetics and complex narratives. StudioBinder’s video essay, “What is Film Noir – Private Detectives, Corrupt Cops, and Femme Fatales,” offers an insightful exploration into the defining characteristics of this enigmatic genre.

The video delves into the quintessential elements that compose film noir:

Private Detectives: Often portrayed as cynical anti-heroes, these characters navigate a treacherous world filled with deceit and moral ambiguity.

Corrupt Cops: Law enforcement figures whose moral compromises blur the lines between right and wrong, adding layers of complexity to the narrative.

Femme Fatales: Seductive women who use their charm and cunning to manipulate others, often leading to the protagonist’s downfall.

Visually, film noir is renowned for its use of stark lighting contrasts, deep shadows, and urban settings that evoke a sense of unease and tension. These stylistic choices not only enhance the mood but also reflect the internal conflicts of the characters.

For filmmakers and enthusiasts aiming to capture the essence of film noir, understanding these thematic and visual elements is crucial. StudioBinder’s comprehensive production management software can assist in meticulously planning and executing projects that embody the film noir aesthetic. From crafting detailed shot lists to organizing shooting schedules, StudioBinder offers tools that streamline the filmmaking process.

To gain a deeper appreciation of film noir and its enduring influence on cinema, watch StudioBinder’s full video essay above:

0 notes

Text

The Dark Longing of Human Desire (1954) – Noir on the Rails

youtube

Film noir has always had a way of exploring the shadows we pretend not to see—hidden motives, guilty passions, and choices that derail lives in slow motion. Few directors captured this as starkly and sensually as Fritz Lang, and Human Desire (1954) is a steel-clad example of that brilliance.

Based loosely on Émile Zola’s novel La Bête Humaine, Human Desire reunites Lang with Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame, hot off the success of their previous collaboration, The Big Heat (1953). Where The Big Heat burned with righteous fury, Human Desire simmers with dangerous lust.

🔥 A Dangerous Triangle on the Tracks

The film follows Jeff Warren (Glenn Ford), a Korean War vet trying to settle back into civilian life as a railroad engineer. But peace and routine are quickly derailed when he becomes entangled with Vicki Buckley (Gloria Grahame), the troubled wife of Jeff’s volatile co-worker, Carl Buckley (Broderick Crawford). Their affair spirals into murder, deception, and the classic noir question: How far would you go for desire?

Lang uses the movement of trains—steel, relentless, inescapable—as a visual metaphor for fate. Every character is on a track they can't seem to change, despite warnings and red lights flashing in their path.

💔 Gloria Grahame: The Eternal Noir Muse

Grahame is unforgettable here. Her Vicki is vulnerable, sultry, manipulative, and trapped—often all in the same scene. Her chemistry with Ford is undeniable, and it’s hard not to feel the heat from their shared screen time. This film cemented her place as one of noir’s most complex female leads—more than a femme fatale, she’s a woman clawing for escape in a man’s world.

🛤️ The Ford-Crawford Dynamic

Human Desire also deepens the on-screen relationship between Ford and Broderick Crawford, who had already worked together in Convicted (1950) and would team up again in The Fastest Gun Alive (1956). Crawford’s performance as Carl is brutal and unnerving, making the character more monster than man—yet with just enough sadness to make you flinch.

Interestingly, the Ford-Crawford connection extended into the 1970s, when Crawford appeared in Ford’s TV series Cade’s County, specifically in the episode "Requiem for Miss Madrid." Even decades later, the energy between these two actors remained potent.

🎥 A Train Through Noir Territory

Lang’s direction makes Human Desire not just a story of lust and betrayal, but a commentary on postwar American masculinity, emotional dislocation, and moral compromise. This isn’t just pulp—it’s psychology with a noir coating.

If you loved The Big Heat, or films like Double Indemnity and Out of the Past, Human Desire deserves a spot on your must-watch list. It’s a film that smolders quietly, steadily—until the inevitable wreck.

🎬 Explore More:

The Fastest Gun Alive (1956) – Trailer – See Ford and Crawford face off in a dusty Western showdown.

Cade’s County: Episode 11 “Requiem for Miss Madrid” – A rare TV moment showcasing the lingering Ford-Crawford connection.

Whether you're a film noir connoisseur or just dipping your toes into the smoke-filled shadows, Human Desire is a haunting journey worth taking—preferably after dark.

#FilmNoir#ClassicCinema#HumanDesire#GloriaGrahame#GlennFord#FritzLang#BroderickCrawford#NoirOnTheRails#DesireAndDeception#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Shadows & Scandals: How Chaos Birthed Hollywood’s Darkest Film Noirs

Introduction Film noir is synonymous with shadows, moral ambiguity, and femmes fatales—but behind the camera, the genre’s gritty allure was often forged in chaos. From murderous actors to guerrilla filmmaking and censorship battles, the stories behind these classics are as twisted as their plots. Grab your trench coat and cigarette lighter as we dive into the madness that birthed Hollywood’s most iconic noirs, complete with rare photos and clips that bring these tales to life.

1. Detour (1945): The $20,000 Masterpiece of Desperation

youtube

Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour is the ultimate example of turning limitations into art. Shot in 6 days with a budget so low actors wore their own clothes, the film’s claustrophobic dread was born from necessity. Lead actor Tom Neal, who later murdered his wife’s lover in real life, brought an eerie authenticity to his role as a hitchhiker spiraling into doom. Watch the fog-drenched highway scene where Ulmer masked cheap sets with shadows here.

2. Gun Crazy (1950): The Bank Heist Shot Like a Crime

youtube

Director Joseph H. Lewis filmed Gun Crazy’s iconic single-take bank robbery with a camera hidden in a convertible, using real streets and unwitting bystanders. Peggy Cummins and John Dall performed their own stunts, including a carnival shooting sequence with live ammunition to capture genuine terror. See the daring heist scene here.

3. The Big Combo (1955): Torture by Hearing Aid

youtube

To bypass strict censorship, director Joseph H. Lewis implied a brutal torture scene using only a hearing aid’s screech and the victim’s contorted face. Cinematographer John Alton’s stark lighting turned empty soundstages into labyrinths of paranoia. Hear the infamous hearing aid scene here.

4. Robert Mitchum’s The Big Steal (1949): High on Noir

Mid-shoot, Robert Mitchum was arrested for marijuana possession. Studio RKO turned the scandal into a marketing ploy, while director Don Siegel scrambled to shoot around Mitchum’s court dates. The actor’s laid-back menace became the blueprint for antihero cool. Watch Mitchum’s devil-may-care performance here.

5. D.O.A. (1950): A Dead Man Directing

youtube

Edmond O’Brien plays a man solving his own murder after being poisoned—a metaphor for the film’s production. Director Rudolph Maté shot in real L.A. locations with natural light, racing against sunset and O’Brien’s intentionally worsening health. See the film’s frenzied opening here.

6. Touch of Evil (1958): Orson Welles’ Studio Nightmare

youtube

Orson Welles’ noir masterpiece was gutted by Universal, who reshot scenes and slashed his budget. Yet the legendary 3-minute opening tracking shot—filmed with a handheld camera and hidden extras—remains one of cinema’s greatest feats. Marlene Dietrich even bought her own thrift-store sequins for her role. Watch the iconic opening here.

7. Kiss Me Deadly (1955): The Mystery of the Glowing Box

youtube

The apocalyptic “whatsit” box that ends Kiss Me Deadly was a budget-saving accident. Director Robert Aldrich couldn’t afford special effects, so he left the box’s contents ambiguous—a decision that inspired Pulp Fiction’s briefcase. Witness the bizarre finale here.

Behind the Curtain: How Noir Defied the Odds

Censorship Dodges: From hearing-aid torture to implied affairs, filmmakers weaponized subtlety.

Lighting Alchemy: Cheap klieg lights and fog machines turned empty rooms into psychological battlegrounds.

Scandal as Marketing: Studios leaned into actors’ real-life crimes to sell tickets.

Conclusion: Noir’s Legacy of Creative Chaos Film noir’s shadowy beauty wasn’t just style—it was survival. These films prove that genius thrives under constraints, and sometimes the darkest art comes from the messiest productions. As Orson Welles once said: “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.”

Want more? Dive into these noirs on Criterion Channel or YouTube Classics.

(Note: Video links are to publicly available clips for educational purposes. Images sourced from Wikimedia Commons and Fair Use archives.)

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Nightmare (1956): A Haunting Tale of Dreams and Deception

The allure of classic film noir lies in its ability to weave suspense, psychological intrigue, and morally complex characters into gripping tales. Maxwell Shane’s Nightmare (1956) delivers all that and more, keeping viewers enthralled with its shadowy cinematography, haunting storyline, and stellar performances.

A Psychological Thriller Rooted in Noir

Based on Cornell Woolrich’s novel And So to Death (also known as Nightmare), the film plunges into the labyrinth of the human psyche. Jazz musician Stan Grayson (Kevin McCarthy) awakens from a harrowing dream—a vivid murder scene so real it feels like a memory. But is it? His desperate search for answers drags him into a spiralling mystery that blurs the lines between reality and delusion.

Stan's struggle is underscored by his relationship with René Bressard (Edward G. Robinson), a detective and his brother-in-law. Bressard’s scepticism and determination to uncover the truth create a dynamic tension that drives the film’s narrative. As secrets unravel and suspicions grow, Nightmare keeps the audience guessing until its chilling climax.

Edward G. Robinson: A Noir Icon

Edward G. Robinson, already a legend in film noir by 1956, brings his trademark gravitas to the role of René Bressard. His portrayal of a detective navigating the murky waters of Stan’s psyche anchors the film, offering both emotional depth and narrative clarity. Opposite him, Kevin McCarthy gives a riveting performance as a man trapped in his own mind, embodying the paranoia and confusion that define the film.

Stylish Noir Visuals

Nightmare excels in its visual storytelling, with stark contrasts of light and shadow creating a claustrophobic atmosphere. The cinematography mirrors Stan’s unravelling mind, using tight frames, deep shadows, and oblique angles to immerse viewers in his paranoia. Maxwell Shane’s direction enhances the tension, ensuring every scene crackles with suspense.

Themes of Guilt and Reality

At its core, Nightmare explores themes of guilt, memory, and reality. How much can we trust our minds? Are dreams simply figments of imagination, or can they hold deeper truths? These questions resonate throughout the film, inviting viewers to engage with its layered narrative on a personal level.

Why Nightmare Stands Out

While Nightmare is firmly rooted in the traditions of 1950s noir, its psychological focus sets it apart from more conventional detective stories. It’s less about solving a crime and more about uncovering the truth within—a thematic choice that elevates it into a uniquely introspective thriller.

Classic Film Enthusiasts, Take Note

For fans of Edward G. Robinson, Kevin McCarthy, or classic noir thrillers, Nightmare is a must-watch. Its blend of suspense, strong performances, and atmospheric visuals make it a standout entry in the genre. Whether you’re a longtime lover of 1950s cinema or a newcomer to the world of film noir, this psychological drama promises an unforgettable viewing experience.

Watch Nightmare (1956) in HD and immerse yourself in a world where dreams turn deadly, and nothing is as it seems.

#youtube#Nightmare1956#FilmNoir#ClassicThrillers#edward g robinson#PsychologicalDrama#Kevin McCarthy

0 notes

Text

Nothing to see here...

Just some badass horror icons.

Vincent Price, Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, and Basil Rathbone publicity still for The Comedy of Terrors (1963)

64 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Somewhere in the Night (1946): A Cinematic Journey Through Mystery and Amnesia

Somewhere in the Night (1946) is a classic film noir that keeps its audience gripped with suspense and intrigue from start to finish. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, the film takes us through a labyrinth of mystery and identity, following George W. Taylor (John Hodiak), a soldier who returns from World War II with amnesia. As Taylor tries to piece together his life, he stumbles upon a dangerous underworld of crime, lies, and deceit that brings him face-to-face with the darkest sides of human nature.

Stars of Somewhere in the Night

John Hodiak as George W. Taylor Hodiak plays the amnesiac war veteran at the center of the story, whose quest to uncover his past leads him into a dark, dangerous world.

Richard Conte as Paul Hanley Conte portrays a key character whose involvement with Taylor deepens the mystery, adding layers of intrigue to the film.

Nancy Guild as Christine Miller Guild plays the mysterious love interest, whose intentions are unclear and whose connection to Taylor’s past plays a crucial role in the narrative.

Herbert Marshall as Mr. Bassing Marshall plays a significant supporting role in the film, bringing an air of authority and suspicion to the story.

The film's plot is steeped in noir conventions, blending a labyrinthine mystery with deep emotional undertones. Taylor's quest to discover who he is mirrors a larger theme within the genre: the search for identity in a post-war world filled with uncertainty and moral ambiguity. As he ventures deeper into a conspiracy involving murder and betrayal, his amnesia serves as a powerful metaphor for the disillusionment of the time, reflecting the confusion many felt in the wake of the war.

Behind the Scenes: Writers and Director

Written by Morris R. Berthold and Robert L. Richards, the screenplay for Somewhere in the Night is full of sharp dialogue and dark, brooding characters. The film explores the complexity of human nature and the challenges of self-discovery, themes that resonate deeply within the noir genre.

The film was directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, an accomplished filmmaker known for his work in both drama and noir. Mankiewicz's directorial style in this film is subtle yet effective, using pacing and atmosphere to heighten the tension. His deft manipulation of suspense draws the viewer into Taylor's fractured world, using the mystery not just to propel the narrative, but to explore the psychological impact of amnesia and moral confusion.

Cinematography and Technical Strategy

Shot by Joseph Walker, the cinematography in Somewhere in the Night is quintessentially noir. The film utilizes shadow-heavy lighting to create a sense of dread and disorientation, effectively mirroring the protagonist’s inner turmoil. The shadows are not just a stylistic choice but also a narrative tool, emphasizing the uncertainty and danger that lurk around every corner.

Mankiewicz's use of dark alleys, tight spaces, and shadow-filled corridors builds an atmosphere of confinement and paranoia. These visual choices, coupled with the evocative score by David Raksin, keep the audience on edge as the story unfolds, reflecting the sense of entrapment that the characters—and the audience—feel throughout the film.

The movie also uses innovative camera angles to evoke a sense of confusion. In key moments, the camera focuses on Taylor’s confused perspective, placing the viewer directly in his shoes as he struggles with his identity. This visual technique not only strengthens the mystery but also emphasizes the noir theme of existential doubt.

Conclusion

Somewhere in the Night is an outstanding example of post-war film noir, where mystery, suspense, and psychological drama intersect in a visually compelling way. With Joseph L. Mankiewicz at the helm, this film is a testament to the director's ability to weave complex narratives and character-driven stories while using technical strategies to enhance the mood. With its strong performances from John Hodiak, Richard Conte, and Nancy Guild, the film remains a must-watch for fans of the genre and for those interested in classic cinema.

#youtube#filmnoir#classic cinema#josephmankiewicz#suspense#amnesia#detectivestory#mystery#John Hodiak#Richard Conte#Nancy Guild#CinematicIcons#Herbert Marshall#1940s film

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Spiritualist AKA The Amazing Mr. X (1948)

This film noir, also known as The Amazing Mr. X, masterfully combines mystery, suspense, and the supernatural. Directed by Bernard Vorhaus, the film weaves a chilling tale about a grieving widow who encounters a mysterious mystic, but what starts as an attempt to reconnect with her deceased husband soon becomes a web of deceit.

Plot Overview

Christine Faber, still mourning the loss of her late husband, is introduced to Alexis, a charming and enigmatic spiritualist. Alexis, played by Turhan Bey, claims he can help her communicate with her dead husband. However, his intentions appear far from genuine, and what follows is a suspense-filled story of manipulation, danger, and mystery.

The Cast

Turhan Bey as Alexis

Lynn Bari as Christine Faber

Cathy O'Donnell as Janet

Richard Carlson as Police Officer

Behind the Scenes and Lesser-Known Facts

Original Title: While it was initially released as The Spiritualist, the film is more widely known under the title The Amazing Mr. X. This change likely helped attract attention to its noir elements.

Casting Tragedy: Carole Landis was initially slated to star as Christine Faber, but tragically passed away just days before filming began. Lynn Bari took over the role.

Cinematographic Excellence: Known for its striking black-and-white cinematography, the film features the work of John Alton, whose use of shadows and lighting creates an atmosphere of suspense and tension that is a hallmark of film noir.

Public Domain: The film entered the public domain due to the original copyright holder’s failure to renew the copyright, which has allowed the film to be widely distributed, albeit in varying quality.

Cult Status: Although the film received mixed reviews upon release, it has since gained a cult following for its combination of supernatural intrigue and film noir style.

Conclusion

The Amazing Mr. X (or The Spiritualist) remains a captivating example of post-war film noir, blending elements of horror, thriller, and supernatural mystery. With standout performances from Turhan Bey and atmospheric cinematography, the film is an enduring classic for fans of suspenseful and eerie cinema.

#youtube#filmnoir#The Spiritualist#OldHollywood#Mystery#TheAmazingMrX#Bernard Vorhaus#Turhan Bey#Lynn Bari#Richard Carlson#Cathy O'Donnell

0 notes

Text

𝕭𝖑𝖆𝖈𝖐𝖜𝖆𝖙𝖊𝖗 𝕴𝖓𝖓 / 𝕭𝖆𝖗

The air is thick, the room deserted, and why is the floor wet? The open window stirs the curtains, but no one’s here. Feels alive with whispers—forgotten secrets. #FilmNoir #Mystery #Detective

0 notes

Text

𝕭𝖑𝖆𝖈𝖐𝖜𝖆𝖙𝖊𝖗 𝕴𝖓𝖓 / 𝕯𝖊𝖙𝖊𝖈𝖙𝖎𝖛𝖊'𝖘 𝕷𝖔𝖉𝖌𝖎𝖓𝖌 𝕽𝖔𝖔𝖒

Dimly lit, fog creeps through the window, dark figures lurk in the mist. A room thick with tension and secrets. #FilmNoir #Mystery #Detective

0 notes

Text

The Maestro Passes On

Devastated by the loss of David Lynch. 💔 He wasn’t just a filmmaker; he was a guide to the mysteries of the human psyche. From Twin Peaks to Mulholland Drive, his work shaped how I see storytelling—and the world. Rest easy, maestro. Your art lives on. 🖤

I’m heartbroken by the passing of David Lynch. 💔 He wasn’t just a filmmaker; he was a visionary who turned the surreal into something deeply human, capturing the beauty, horror, and mystery of existence like no one else could. From Eraserhead to Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet, and Mulholland Drive, his work shaped not only cinema but also how I see storytelling—and the world itself.

Lynch’s ability to explore the depths of the subconscious, exposing both its light and its darkness, was unparalleled. His films and shows weren’t just stories; they were experiences that stayed with you long after the credits rolled. They challenged you, haunted you, and made you think differently about reality.

I’ve followed everything he’s done, and his work has left a permanent mark on me. The world feels a little less magical today, but his art will live on, inspiring generations to come. Rest in peace, maestro. Thank you for everything. 🖤

#DavidLynch #TwinPeaks #BlueVelvet #MulhollandDrive #Eraserhead #Visionary #Filmmaker #ArtLivesOn #ThankYouDavid

#DavidLynch#TwinPeaks#BlueVelvet#MulhollandDrive#Visionary#Filmmaker#ArtLivesOn#filmnoir#Eraserhead#ThankYouDavid

0 notes

Text

🌟 Projects Available for Script Commissions or Producer Collaboration 🌟

Looking for your next innovative and marketable story? These projects are designed for producers seeking captivating scripts with flexibility for collaboration and adaptation. Let’s bring these stories to life!

👉 Explore more details here: smitherscenes.com/projects

Tequila Slammer

Genre: Thriller, Comedy Premise: A betrayed husband wakes up from a tequila-fueled car crash with no memory of who he is and must unravel his identity while evading Russian mobsters, a relentless bounty hunter, and corrupt cops. His journey reveals a twisted web of stolen cash and deadly secrets. Pitch: This project combines offbeat humor, action-packed sequences, and a stormy desert climax. It’s a rollercoaster of survival and redemption with a uniquely twisted storyline that producers can adapt into a thrilling cinematic experience.

Eyeball Lane

Format: 12-Episode Series Premise: Set in a surreal, dreamlike parallel universe, "Eyeball Lane" is a realm of transformation where flaws are exposed, debts are settled, and grievances are resolved through mystical rituals or sacrifices. Accessible only through dreams or deeds, this universe challenges morality and decision-making in its eerie yet captivating world. Pitch: A high-concept series blending dark fantasy and psychological drama, ideal for streaming platforms looking for fresh, thought-provoking narratives.

Blackwater Inn

Genre: Film-Noir Premise: A reclusive former naval detective investigates a fisherman’s murder near a mysterious coastal inn. His search uncovers smuggling, betrayal, and secrets tied to the region's shipbuilding legacy and haunting maritime past. Pitch: Rich with atmosphere and suspense, this noir mystery offers producers an evocative, character-driven story steeped in historical intrigue and layered secrets, perfect for fans of moody, immersive cinema.

📩 Ready to collaborate? Visit smitherscenes.com/projects to learn more and get in touch! Let’s create something extraordinary together. 🎬✨

#film production#screenwriting#thriller#comedy#film-noir#fantasy drama#TV series#innovative scripts#marketable projects#producer collaboration#script commissions#desert adventure#psychological drama#maritime mystery#suspenseful storytelling

0 notes

Text

The Blue Dahlia (1946) - A Noir Classic

Step into the shadowy intrigue of The Blue Dahlia, now vividly brought to life in color! This Paramount Pictures crime drama, written by the legendary Raymond Chandler, delivers a gripping tale of betrayal, murder, and redemption.

When Johnny Morrison (Alan Ladd), a decorated bomber pilot, returns from the war, he discovers his wife, Helen (Doris Dowling), in the arms of another man—Eddie Harwood (Howard Da Silva), owner of the Blue Dahlia nightclub. Her confession of a heartbreaking secret about their son's death drives Johnny away, but when Helen is found dead, all eyes turn to him as the prime suspect.

Featuring the iconic pairing of Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake (as the mysterious Joyce Harwood) and a stellar supporting cast including William Bendix and Howard Da Silva, this film noir gem is packed with suspense, emotional depth, and unforgettable performances.

Now colorized for a new generation of viewers, The Blue Dahlia retains all the mood and tension of the original while adding a fresh dimension to its visual storytelling.

Don’t miss this rare opportunity to experience a film noir classic in a whole new light!

Starring:

Alan Ladd as Johnny Morrison

Veronica Lake as Joyce Harwood

William Bendix as Buzz Wanchek

Howard Da Silva as Eddie Harwood

Doris Dowling as Helen Morrison

Tom Powers as Capt. Hendrickson

Hugh Beaumont as George Copeland

Genres: Crime Drama, Film Noir Language: English Available in: Colorized version (Item size: 583.9M)

Immerse yourself in this timeless tale of shadows and secrets. Let the tension pull you in, and let the color breathe new life into a noir masterpiece!

#FilmNoir#ClassicCinema#AlanLadd#VeronicaLake#TheBlueDahlia#CrimeDrama#VintageMovies#Colorized#Raymond Chandler#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Link

Rusty Knife (1958) is an important film in the career of director Toshio Masuda, marking his first significant foray into the world of Japanese cinema. The film exemplifies the post-war crime drama genre, which was particularly popular in Japan during the 1950s.

The story revolves around two ex-gangsters, played by Yujiro Ishihara and Akira Kobayashi, who are trying to distance themselves from their criminal pasts. However, their attempts at redemption are thwarted when they become entangled in a murder investigation, leading them to confront their pasts. The tension between their desire to move forward and the inescapable pull of their history is a key theme in the film, contributing to its noir atmosphere.

Both Ishihara and Kobayashi were highly popular Nikkatsu stars of the time, and their performances added a great deal of star power to the film. Masuda’s direction, combined with the strong performances, made Rusty Knife a critical success and helped establish him as a director with a distinctive voice in the Japanese film industry. This film also played a significant role in solidifying the "yakuza" genre in Japanese cinema, which would continue to evolve in the decades to come.

0 notes

Text

Discover the dark allure of Japanese cinema with the BFI's top 10 film noirs

From post-war shadows to moral complexity, these classics redefine noir through a uniquely Japanese lens. A must-watch for cinephiles! 🎥✨

10 Great Japanese Film Noirs: A Journey Through Shadows

The allure of Japanese noir is a masterful blend of postwar realism, cultural complexity, and an unmistakable flair for visual storytelling. From shadow-drenched crime dramas to existential sagas, Japanese filmmakers redefined the noir genre with their unique sensibilities. Here's a deep dive into ten standout films that showcase the rich texture of Japanese noir:

Stray Dog (1949) Akira Kurosawa’s early masterpiece, a gripping tale of a rookie detective searching for his stolen gun, immerses viewers in postwar Tokyo's searing summer streets.

I Am Waiting (1957) A poignant tale of broken dreams and crime, this Koreyoshi Kurahara classic explores the fragile hopes of a boxer and a cabaret singer trapped by their pasts.

Rusty Knife (1958) Directed by Toshio Masuda, this crime drama reveals the underbelly of postwar Japan, where corruption and violence thrive in a world struggling to rebuild.

Intimidation (1960) A taut 65-minute gem that lays bare class divides and moral corruption, directed by Koreyoshi Kurahara.

Zero Focus (1961) Yoshitaro Nomura crafts a Hitchcockian noir, unraveling a haunting mystery of lost identity and post-occupation secrets.

Pale Flower (1964) Masahiro Shinoda’s enigmatic noir follows a yakuza and a femme fatale in a moody dance of existential despair.

Cruel Gun Story (1964) Takumi Furukawa’s heist thriller, starring the iconic Jo Shishido, blends meticulous plotting with the chaos of betrayal.

A Fugitive from the Past (1965) Tomu Uchida’s epic crime saga explores guilt and redemption in the shadow of Japan’s postwar moral landscape.

A Colt Is My Passport (1967) This stylish Takashi Nomura film channels spaghetti western vibes into a sharp-edged tale of hitmen and honor.

Branded to Kill (1967) Seijun Suzuki’s avant-garde noir is an unforgettable, surreal journey into the fragmented psyche of a hitman.

Dive into these classics to experience the unique lens of Japanese noir, where crime, culture, and existentialism intersect.

2 notes

·

View notes