I’m a data analyst that’s into philosophy so philosophy and data will be my motif here.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

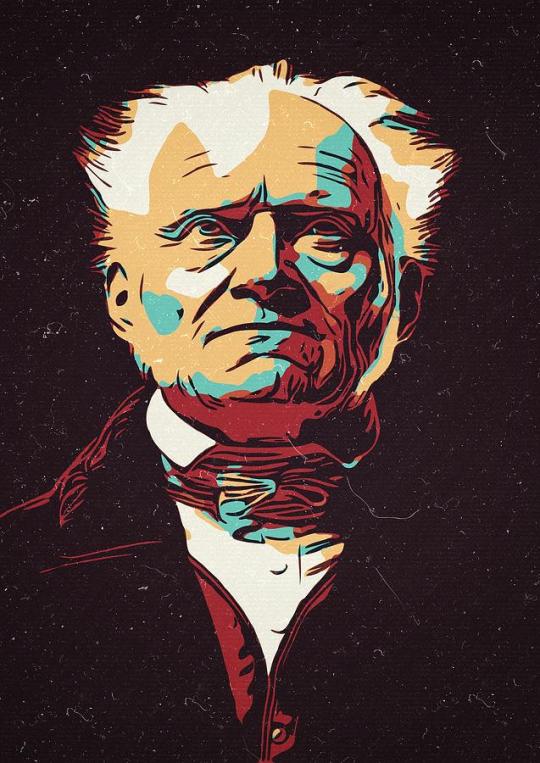

The Darkest Philosopher in History - Arthur Schopenhauer

Being one of the first philosophers to ever

really question the value of existence,

to systematically combine eastern

and western modes of thinking,

and to introduce the arts as a serious

philosophical focus, Arthur Schopenhauer

is perhaps one of the darkest and most

comprehensive philosophers in western history.

Schopenhauer was born in 1788 in what is

now Gdansk, Poland, but spent the majority

of his childhood in Hamburg, Germany after

his family moved there when he was five.

He was born to a wealthy family, his father

being a highly successful international merchant.

As a result of this, young Schopenhauer would

be expected to follow in his father’s footsteps.

However, from an early age, he had no interest

in business, and instead, found himself compelled

towards academics. And after going on a trip

around Europe with his parents to prepare him

for his merchant career, the greater exposure

he would receive to the pervasive suffering

and poverty of the world would cause him to

become all the more interested in pursuing

the path of scholarship and intellectually

examining, down to its very core, how the

world worked and why—or perhaps more accurately,

how and why it appeared to work so negatively.

After eventually going against his family’s

readymade path of international business,

Schopenhauer would attend the University of

Göttingen in 1809, where, in his third semester,

he would become more introduced and

focused on philosophy. The following year,

he would transfer to the University of Berlin

to study under a better philosophy program led

by distinguished philosophy lecturers of the

time.

However, Schopenhauer would soon find

academic philosophy to be unnecessarily obscure,

detached from real concerns of life, and often

tethered to theological agendas; all of which,

he despised. Eventually, he left the academic,

intellectual circuit, and spent the following

decade philosophizing and writing on his own.

By age thirty, Schopenhauer had published

the two works that would go on to define

his entire career, contain his complete,

unified philosophical system from which

he would never deviate, and eventually influence

the entire course of western thinking with.

The first groundwork of his philosophy

was established in his dissertation,

On the Fourfold Root of the Principle

of Sufficient Reason, published in 1813,

and his entire unified philosophical system,

including his metaphysics, epistemology, ethics,

aesthetics, value judgments, and so forth,

was laid out in his subsequent masterwork,

The World as Will and Representation, published

in 1819. Despite these impressive works going on

to hold major stake in western philosophy,

influencing some of the greatest thinkers

and schools of thought thereafter, during

this time, they would go mostly unnoticed.

Over the decades following his early

work, throughout his thirties and forties,

Schopenhauer would spend his time working to be a

lecturer at university, as well as a translator of

French to English prose, while continuing to write

on-and-off along the side. He found very little

success in all of it. His lectures were unpopular,

his translations received very little interest,

and his philosophical work remained mostly

overlooked. Only by around his fifties,

did Schopenhauer finally start to receive

any notable recognition, at all.

And only

after publishing a book of essays and aphorisms

in 1851, would he achieve the status of fame,

which he would remain in for the rest of his life

until he died in 1860 at the age of seventy-two.

In terms of Schopenhauer’s philosophical system

established within his work, it is relevant to

note that it leaned heavily on the work of his

predecessor, Immanuel Kant. In Schopenhauer’s

mind, he was completing Kant’s system of

transcendental idealism. Building off his

interpretation of Kant, Schopenhauer essentially

suggested that the world as we know and experience

it, is exclusively a representation created by our

mind through our senses and forms of cognition.

Consequently, we cannot access the true

nature of external objects outside our mental,

phenomenological experience of them. Deviating

from Kant, however, Schopenhauer would go onto to

argue that not only can we not know nor access the

varying objects of the world as they really are

outside of our conscious experience, but

there is, in fact, no plurality of objects

beyond our experience, at all. Rather, beyond

our experience is, according to Schopenhauer,

a singular, unified oneness of reality—a sort

of essence or force that drives existence

that is beyond time, beyond space, and beyond all

objectivation. Schopenhauer would go on to explore

and define this force by referencing and probing

into the experience of living within the body,

suggesting that this is the only thing

in the world that we have access to

that is not solely a mental representation of

an object but is also a firsthand, subjective

experience from within it. From here, Schopenhauer

would suggest that what is found from within,

at the core of our being, is an unconscious,

restless, striving force towards survival,

nourishment, and reproduction. He would term this

force the Will to live.

Essentially, this would

lead him to the conclusion that reality is made

up of two sides; one side being the plurality

of things as they are represented to a conscious

apparatus, and the other side being the singular,

unified force of the Will—hence the name of his

master work, The World as Will and Representation.

It is worth noting that the term Will can

perhaps be misleading in that it might seem

to imply an intention or human-like conscious

motivation, but the Will, for Schopenhauer,

is a blind, unconscious striving with no goal

or purpose other than to keep itself going

for the sake of keeping itself going. All of the

material world operates by and through this Will,

moving, striving, consuming, and violently

expressing itself in order to sustain itself.

Schopenhauer’s work was largely a response to

Kant and the western philosophical tradition,

but his work also contains distinct notes of

Hinduism and Buddhism. His conclusion of the

nature of reality is strikingly similar to that of

both. And his qualitative assessment of reality’s

negative relationship with the conscious self

mirrors ideas central to Buddhism. This made

Schopenhauer one of the first philosophers to

ever really combine eastern and western thinking

in such a systematically comprehensive way.

Especially similar to Buddhism, Schopenhauer

would top off his philosophical medley with a

layer of dark, unwavering pessimism. “Unless

suffering is the direct and immediate object of

life, our existence must entirely fail of its aim.

It is absurd to look upon the enormous amount

of pain that abounds everywhere in the world,

and originates in needs and necessities

inseparable from life itself, as serving no

purpose at all and the result of mere chance. Each

separate misfortune, as it comes, seems, no doubt,

to be something exceptional; but misfortune in

general is the rule.” Schopenhauer wrote. As a

qualitative assessment of the nature of reality,

he would describe the Will to live as a sort of

malevolent force that we, as individual selves,

become victims of in its process of continuation,

deceived by our own mind and body to go against

our fundamental interests and yearnings in order

to carry it out. Since the Will has no aim or

purpose other than its perpetual continuation,

then the will can never be satisfied. And

since we are expressions of it, neither can we.

Thus, we are driven to consume beings, things,

ideas, goals, circumstances, and all the rest,

constantly hoping we will feel a satisfaction or

happiness as result, while constantly being left

in the wake of each achievement unsatisfied.

"Human life must be some kind of mistake.

The truth of this will be sufficiently obvious if

we only remember that man is a compound of needs

and necessities hard to satisfy; and that even

when they are satisfied, all he obtains is a state

of painlessness, where nothing remains to him

but abandonment to boredom.” Schopenhauer wrote.

As the best possible ways of sort

of escaping and dealing with this,

Schopenhauer would put forth two primary methods:

one, engaging in arts and philosophy, and two, the

practicing of asceticism, traditionally being the

deprivation of nearly all desire, self-indulgence,

and everything past the bare minimum. In this

later method, Schopenhauer felt that by denying

the Will from being fed, so-to-speak, one would

turn the Will against itself and overcome it.

However, he also recognized the sheer

difficulty of this for the majority of people

and suggested the average person should

simply make their best efforts towards

letting go of ideals of happiness and pleasure,

and rather, focus on the minimization of pain.

Happiness in life, for Schopenhauer, is not

a matter of joys and pleasures, but rather,

the reduction and freedom from pain

as much as possible. “The safest way

of not being very miserable is not to

expect to be very happy.” he wrote.

Alternatively, engaging in arts and philosophy,

in Schopenhauer’s mind, served as another, more

accessible method. He felt that good art could

provide a source of clarity into the nature and

problems of being, without any of the illusion or

drapery. And while engaging in this sort of art,

one would have a transcendent-like experience

that provides a relief and comfort from existence.

As a result of this concept,

Schopenhauer would end up being one

of first thinkers to ever really introduce

philosophical significance to the arts,

and would eventually become known by

many as the ‘artist’s philosopher.’

Of course, throughout his work in general,

Schopenhauer makes large, often unprovable,

and unknowable claims about the nature of reality

and the value of existing within it. Some of which

is validly constructed and worth considering,

but some of which is likely not. Ultimately,

any attempt to define and assess the side of

reality beyond logic and reason through systematic

logic and reason is perhaps paradoxical in way

that is beyond repair. What precisely is the Will,

where does it come from, where does it

end, and how can we know or prove it?

And in terms of Schopenhauer’s suggestion

that one should turn against the Will

through an ascetic process of self-denial,

if all of life operates through the Will,

to turn against it, would seem to merely be the

Will turning against the Will for reasons that

favor it. And there can be no turning against

the Will if the Will is doing the turning.

Alternatively, considering the view of Friedrich

Nietzsche, a philosopher who notably followed in

Schopenhauer’s footsteps, the endless cycle of

desire and dissatisfaction caused by the Will

is actually a good thing that we can use as fuel

towards the process of self-overcoming and growth,

which we can then obtain life’s meaning

from. Of course, this is the more pleasant

of the two interpretations, but it isn’t clear

which is more apt and/or accurate, if either.

Ultimately, Schopenhauer is another surprising,

yet seemingly common story where a highly

important thinker, artist, or writer, barely

caught any recognition in their life, if at all,

only to die and end up with their name in

nearly every history book on the subject.

One trait these stories do all

seem to have in common, though,

is a refusal to stop, a refusal to budge from

pursuing and defending the world as one sees it.

Schopenhauer never deviated from the

philosophical system he created in his twenties

and never stopped confidently working to build

upon it and reinforce it throughout his life,

despite the world seeming to suggest to

him he should do otherwise. And yet, now,

it is hugely significant to the world that he did

exactly what he did. For some, his work might be

bleak and disconcerting, but for others, his work,

like all great works of dark, melancholic honesty,

is comforting, relieving, and legitimizing. It

reminds us that are not crazy, and our sadness

and suffering are not unfounded, even when they

may feel like it. We are merely put in a crazy,

sad, violent reality with a mind and body

that are often all in conspiracy against us.

Because of this and many other reasons

unmentioned, his work would go on to

influence artists like Richard Wagner and Gustav

Mahler; writers like Marcel Proust, Leo Tolstoy,

and Samuel Beckett; and thinkers like Friedrich

Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Ludwig Wittgenstein,

as well as many others, ultimately influencing

the course of modern thinking, forever.

Having been one of the first to properly

and philosophically bring the value of life

and the possibility of meaning into question,

Schopenhauer helped locate the early budding

problem of the growing agnostic world

that philosophy would need to address.

With humanity seemingly suspending

further out into a void of meaning,

his unyielding and fearless confrontation with

the nature of existence, including all its

horrors and miseries, revealed an opening of new

possibilities towards finding answers from within.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wait for the turbulence to dissipate and clarity to arrive.

The Mind is a Pond // themindthdimension

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Average Principle solution to the Repugnant Conclusion

I recently read about the Repugnant Conclusion, it's my first exposure to the subject. I'll try to summarise the gist of what the Repugnant Conclusion is. The original formulation by Parfit of the Repugnant Conclusion is:

> For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.

In other words, given a population A with a small number of people, each living with a very high level of well-being, for any small but positive level of well-being $\epsilon$, much smaller than A's average, we can imagine a population Z, with all members living $\epsilon$-good lives, large enough to be better overall than A—no matter how small $\epsilon$ is. This stems from a utilitarian perspective, where a population's "goodness" is defined as the aggregate (the sum) of the well-being of each of its individuals. But even if you don't come from a utilitarian view of ethics, if you just assume a basic additivity principle (i.e. that if you start with a population with uniform high well-being, and you add a handful of people with slightly lower but still positive well-being, then you end up with a population that is better overall), it turns out that the Repugnant Conclusion still follows. For more details, diagrams, and an explanation of how the Repugnant Conclusion is reached, see the article linked above.

While reading through the definition and presentation of the Repugnant Conclusion, one potential solution immediately came to mind: instead of evaluating a population by the aggregate of its individuals' well-being, we should use the *average* well-being. Unsurprisingly, philosophers had already thought of this before; this solution is the first one listed under the proposed solutions in the linked article. It turns out that it has some counterintuitive consequences that prevent it from being accepted by most philosophers. However, in my view, while the consequences mentioned in the article might be counterintuitive, that doesn't mean they're unacceptable. The article seems to dismiss this solution too quickly. In this post, I want to expose my thoughts and responses to the counterarguments presented in the article, and see what other people (you, the reader) think.

If we assume the Average Principle, a population's size is no longer directly influential in its evaluation; rather, what matters is the *distribution* of well-being. Thus, in the example above, population A would be much better than Z, independently of how large Z is, since A has a much higher average than Z (and, in this construction, the size of Z has no influence on the average since everyone is living at the same quality of life). So it completely avoids the Repugnant Conclusion. But it comes with some counterintuitive consequences; the article mentions two of these. The first is that

> for any population consisting of very good lives there is a better population consisting of just one person leading a life at a slightly higher level of well-being.

Or, reformulating it in terms of equality: for any population consisting of very good lives, there is an equally good population consisting of just one person leading a life at the same level of well-being as each of the former's members. The second is that

> for a population consisting of just one person leading a life at a very negative level of well-being, e.g., a life of constant torture, there is another population which is better even though it contains millions of lives at just a slightly less negative level of well-being.

In terms of equality: for a population consisting of just one person leading a life at a very negative level of well-being, e.g., a life of constant torture, there is another equally good population (equally bad) containing millions of lives at the same negative level of well-being (i.e. at the same level of suffering).

I think the reasoning that is leading us to consider these consequences as counterintuitive or undesirable is flawed. We might see the first consequence as undesirable because we see a larger number of people experiencing the same high level of well-being is intrinsically better than a smaller number. In the second case, the reasoning is similar: we see a larger number of people suffering at the same level as intrinsically worse. In both cases, we're relying on some form of *additivity* of well-being; we're judging one scenario better or worse than the other based on the *total* well-being, the *sum* of the individuals' well-being. In my view, this is wrong, or at least problematic.

Using the sum of well-beings as a meaningful metric implicitly assumes that there is a real entity that corresponds to that metric. In a way, it assumes that there exists some kind of aggregate subject who is experiencing all of its components' lives simultaneously. If such an entity existed (which presumably would coincide with the population), then the sum of its components' level of well-being would be a very sensible measure for *its* well-being. But in my opinion, the only scale at which experience (and thus well-being) is meaningful—i.e., exists—is the individual. Smaller scales clearly don't make sense, since almost by definition an individual is an atomic unit of experience; but larger scales don't make sense either. (Notice that I'm saying this for the existence of experience alone, I'm not saying that *everything* is only meaningful at this scale. This has nothing to do with individualism, but rather with the ontology of experience and sentience.) There is no such thing as a "sentient" aggregate of individuals, one to which a level of well-being can be assigned.

Consider the following example. Let f be a function that maps each letter of the English alphabet to a numerical index: "A" maps to 1, "B" maps to 2, "C" maps to 3, and so on. The domain of this function is the alphabet, while we can consider its codomain to be the real numbers. The real numbers have an addition operation: we can add two numbers, as in 1 + 2, to get another real number, in this case 3. In particular, we can add images under f together: f("A"), which is 1, plus f("B"), which is 2, gives 3, which is also f("C"). In symbols: f("A") + f("B") = f("C"). But does that mean that there is a homologous operation in the domain? I.e., does that mean that "A" + "B" = "C", or even that there exists *any* letter in the alphabet (or any other object, for that matter) that is equal to "A" + "B"? Not at all. Indeed, there is no operation of addition in the domain in the first place—you can't *add* two letters together. (Of course, we could *define* such an operation, but this would just be an exercise in mathematics—a place where we make our own arbitrary rules—, and it doesn't extend to the real philosophical example we're considering.)

This also applies to the well-being of the individuals of a population. That is, let S be the set of individuals of a population, and let f be the mapping that tells us the well-being of each individual, i.e. the function that maps each individual to their level of well-being, as a real number. (Let's leave aside the issue of whether such a quantification is even possible, for if we don't, none of this discussion would make sense.) Individuals x and y in S have well-being levels of f(x) and f(y) respectively. The latter are real numbers, so we can add these together: f(x) + f(y). But is this addition at all meaningful in the realm of individuals, of experience? I.e. does this mean that there is a corresponding entity (regardless of whether it is an individual, an aggregate of individuals, or something else) that has a level of well-being f(x) + f(y)? No: there is no "sum" subject x + y, one that is experiencing the lives of x and y simultaneously, so to speak. This is what I mean by saying that quality of experience is not additive: while we can add things together in the model of numbers, this doesn't translate to a meaningful addition of things in the reality of experience.

This extends to the matter at hand: by refusing additivity of the levels of well-being of any two individuals, we refuse additivity for an entire population. We can't judge a population by its *total* well-being because it is the sum of individual levels of well-being, which is meaningless because there is no aggregate subject experiencing all of the lives of those individuals at once.

Thus, if we are to evaluate a population by the level of well-being of its individuals, we must do so remaining at the scale of individuals, which is the smallest and simultaneously the biggest (and thus the only) scale at which a level of well-being makes sense. The only sensible way (that comes to mind) to do so is to use the *expected value* of the well-being of an arbitrary individual from the population—the average. For me, population A is better than population B if and only if I, as a *consciousness*, as an experiencing subject, have a better chance of leading a better life if I am randomly assigned to one of the lives in A rather than B.

So, in the first of the scenarios above, my expectations for a good life would be equal regardless of whether I was assigned into a population of one or a population of one billion. So the populations are equally good. Similarly, for the second scenario, my expectations would be equally dim regardless of the size of the population—I would live the same life of horrible torture regardless. I find this easier to accept intuitively if I think of the following modified scenario. Consider a population of millions living the same life of torture as the sole person in the population of one, but this time each individual is tortured in an isolated cage, and each cage is billions of light-years away from all other cages. None of these poor souls would ever be aware of the existence of others, and for *each* of them, at an individual level—which, for me, is the only meaningful level of experience—, the situation is the same as for the population of one.

I don't think in any way that this is a complete justification of the average principle, these are just my intuitions and first arguments that come to mind. But it certainly seems to me that we shouldn't be so fast in discarding this as a solution to the Repugnant Conclusion.

Links:

(https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/repugnant-conclusion/ )

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/repugnant-conclusion/#IntNewWayAggWelMeaVal

0 notes

Text

How does omniscience interact with randomness?

What are the implications of God's omniscience for randomness? For example, could God create a truly random number generator, such that even He doesn't know what number it will generate?

My hypotheses:

What I’ve stated is essentially an articulation of the classic Omnipotence Paradox, but restated to be about knowledge (omniscience) rather than power/ability (omnipotence). There are a variety of responses to these kinds of challenges, but common answer is that omnipotence only covers that which is logically possible.

The existence of truly unknowable numbers is logically incompatible with a God that knows absolutely everything. Therefore, either the numbers aren't truly unknowable, or God isn't truly omniscient.

In simple terms, one either needs to reject the existence of an all-knowing God, or one has to reject the existence of unknowable information.

0 notes

Text

Good Ol’ Boredom

Boredom is an abstract crisis of desire—one at home in a secularised world where attention has become a commodity.

Boredom isn’t a personal issue, it’s a symptom of the modern industrialised world.

The only problem I see is the attitude that boredom is a problem that requires an immediate solution.

The ability to sit with your own boredom and treat it like an 'ok' feeling is what allows you to pay attention to what is truly important in the moment without requiring a distraction to alleviate your sense of unease.

3 notes

·

View notes