Text

Concluding Razia’s Shadow: The Theme

What is the point of a story? When you are writing fiction, what is the purpose? Why must your imaginary adventure be heard? It is because you have a thought, a recognition, an insight that you haven’t heard addressed before; you have a theme (maybe several!) to share with the world. I’d like to show how musical Razia’s Shadow (RS) expresses its theme through the sum of all of its parts; then you, too, can follow their example and effectively apply themes in your stories!

According to Gotham Writers Workshop, a theme isn’t a lesson or moral; it’s a new angle on the human condition. Just as there are right or wrong ways to write stories, there are right and wrong ways to apply a theme. Famous novelist Flannery O’Connor defines the “right” application as “When you can separate [the theme] from the story itself, then you can be sure the story is not a very good one. The [theme] of a story has to be embodied in it, has to be made concrete in it.”

The theme of RS, as repeated through the musical, is:

“The unrelenting constancy of love and hope

Will rescue and restore you from any scope”

-The End and the Beginning, Lines 66-67

In less poetic terms, no matter how dismal circumstances seem, you can rely on love and hope as eternal concepts. Like O’Connor said a good theme should, all of RS is tied to emphasizing this one point.

RS’ begins its discussion of love and hope by giving the world a problem to be saved from. A slighted angel lashes out at his loved ones, and as punishment for his actions, the world is torn into two halves. Ironically, the angel’s betrayal stems from misunderstanding the intentions of people who love him. As a result of his punishment, both halves of the world, incomplete without the other, suffer and are doomed to fall to ruin unless they can be reunited. Act I perverts the images of love and hope through misunderstanding and tragedy, and now they must be righted.

Act II shows how love and hope can now save the world. The angel’s descendant, the protagonist, realizes he must revert his ancestor’s wrongs through “an act of love.” Many trials come against him, but he remains faithful–hopeful–in the purpose of his mission, allowing that hope to push him through each and every test. In the final scene, the protagonist must take a dagger meant for his love interest, committing the “act of love,” needed to reunite the world. He lays dying in his brother and love interest’s arms, at peace; his hope in his “destiny” has finally culminated. RS’ theme of love and hope saving the day is fully realized, and the story can come to an end.

A theme gives an audience, as well as a writer, a reason to care about the story. When the theme is woven in, inseparable from the characters and events that take place, it can challenge an audience’s way of thinking, go against popular ideas, or present new insights about the human condition. Themes are why storytelling and all the intricate pieces and parts that go into it are so important to not just writers, but an audience. The theme is also why RS is so important to me, and why I love to talk about it so darn much! Now, I’d like to let RS sum this up for me:

“So this is my cue of where to leave you

Now it's your story to retell and pass on

Because an idea is only relevant if it's being thought upon”

-“The End and the Beginning,” Lines 62-64

Sources:

“Flannery O'Connor.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 13 Apr. 2019,

https://www.biography.com/writer/flannery-oconnor.

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

Pei, Lowry. “Flannery O'Connor on Meaning.” On the Way to Writing, 12 Feb. 2011,

https://lpei4.wordpress.com/on-writing-esp-fiction-and-creative-process/flannery-

oconnor-on-meaning/.

Reissenweber, Brandi. “Does a Story Have to Have a Moral?” Gotham Writers

Workshop, Gotham Writers, https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/ask-

writer/does-a-story-have-to-have-a-moral.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aristotle’s Tragic Hero in “Razia’s Shadow”

Of all the movies you saw this year, how many gave the hero a happy ending? Probably the majority, right? As a culture, we’re accustomed to seeing the protagonist overcome the odds, get the love interest, and settle into their happily ever after before the credits roll or the last page turns. However, not all heroes leave on such a cheerful note. I’d like to look at Aristotle’s “tragic hero,” a hero that, through their actions and the forces around them, either teaches your audience a moral or grants them an emotional “catharsis.” To see how you can apply this hero and how they can benefit your story, let’s look at Adakias from the musical Razia’s Shadow (RS).

Fig. 1. Ray, Rebecca. “Types of Heroes in Literature.” Storyboard That, Storyboard That, 14 Mar. 2019, https://www.storyboardthat.com/articles/e/types-of-heroes.

Hamartia:

Adakias’ initial “flaw” that causes his downfall is his insistent belief that he is the “chosen one,” destined to bring his own world of “The Dark” back together with its split half, “The Light,” through an act of love.

By giving the hero an initial flaw, the writer sets up the progression of the story’s tragedy, as well as how the “Nemesis” portion will play out. It also makes the hero a more interesting character.

Hubris:

Adakias meets Anhura, a princess from The Light. The two of them fall in love and run away from her homeland and disapproving father. However, Adakias hides the fact that he is from The Dark.

The hubris allows the tension of the story to heighten. Adakias’ belief about needing “an act of love” leads him to actually fall in love; however, he neglects honesty in the relationship. This will have consequences.

Peripeteia:

Anhura suddenly falls ill. Adakias realizes that it is his fault, as someone from The Dark can cause someone from The Light to be sick by proximity. He must now set out to find a doctor, but still hides the truth from Anhura out of fear.

The hero’s good standing falls apart due to the consequences of their actions. Forces outside the hero’s control can also contribute to his fate. The story’s stakes intensify as a result.

Anagnorisis:

Adakias encounters two oracles who confirm he is destined to bring the divided worlds of The Light and The Dark back together. They also warn him to, “watch out for the wicked ones who call themselves beloved ones,” a line that foreshadows the final act (Line 25, “Holy the Sea”).

The hero now understands something vital about their current plight. This shift is often ironic, and subsequently creates further foreshadowing of the hero’s doomed fate.

Nemesis:

The antagonist, Pallis, catches Adakias after being in hot pursuit for the duration of the musical. Pallis attempts to kill Anhura to get Adakias to come home, but Adakias leaps in and takes the blow instead. Now mortally wounded, Adakias accepts his death as “the act of love” necessary to unite the Light and Dark once more.

The act that makes a tragic hero a tragic hero occurs. The hero fulfills their destiny, the outcome either good or bad, and suffers for it.

Catharsis:

The narrator closes the musical on a somber note, acknowledging that, “we lost Adakias, but regained our science,” (Line 68, “The End and the Beginning”). The worlds of the Light and Dark are reunited and certain destruction avoided thanks to Adakias’ sacrifice.

Though the irreversible tragedy of the story has taken place, the characters and world that remain can learn from what’s happened. The audience will carry the lessons of the hero’s flaw with them; a lesson learned without having to experience the consequences.

A tragic hero can add tension, conflict, and of course, emotion in a story. They also operate as an invaluable tool in getting across your own perspectives and morals without your audience having to go through the tragedy themselves. Try following Aristotle’s framework (and RS’ example!) if you too are interested in writing a hero that pulls at the heartstrings and teaches valuable lessons.

Sources:

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

Ray, Rebecca. “The Tragic Hero.” Storyboard That, Storyboard That, 6 Nov. 2019,

https://www.storyboardthat.com/articles/e/tragic-hero.

Ray, Rebecca. “Types of Heroes in Literature.” Storyboard That, Storyboard That, 14

Mar. 2019, https://www.storyboardthat.com/articles/e/types-of-heroes.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Patterson’s Laws of Villainy in “Razia’s Shadow”

What do villains like Hannibal Lecter, the Joker, and Loki have in common? You recognized them all! This is because their creators carefully crafted them as interesting villains. But how do you create a villain that your audience “simultaneously [loves] and [hates]”? According to the world’s bestselling author, James Patterson, and his MasterClass, “Three Tips for Writing a Great Villain,” there are tried-and-true methods for creating a successful baddie. To see how you can apply these tips to your work, let’s analyze the villain of musical Razia’s Shadow (RS).

1. Create a Three-Dimensional Villain

A villain can’t just rub their hands together and give a maniacal laugh; they require “interesting backstories, personal traumas, and motivations that drive them.” These aspects will make the character memorable and sympathetic, even if the audience hates all the dastardly things they’re doing to the hero at the same time.

In RS, the villain, Pallis, is elder brother to Adakias, the hero. From the start, the audience can relate to Pallis through his familial tie to his younger brother. When Adakias believes he must abandon his home to save the world from inevitable destruction (something RS’ world largely disbelieves in), Pallis forbids him from leaving. Adakias runs away, and Pallis is enraged; he pursues Adakias for the rest of the musical in order to bring him home. By giving Pallis a domestic connection to the protagonist, the audience can sympathize with his decisions, despite him pursuing the hero we’re supposed to be rooting for. Pallis is a three-dimensional villain.

2. Humanize the Villain

Villains with “human” qualities allow an audience to further connect with the character. Note that “human” qualities do not equal “heroic” qualities. For example, secretive, wrathful, prideful, greedy–none of these traits are heroic, but they are very human.

In RS, the audience, based on Pallis’ initial cold and demeaning attitude, might think Pallis hates his brother. However, the final scene subverts this assumption. Once Pallis finds his brother, he attempts to have him come home by killing Adakias’ love interest. Adakias takes the blow instead, and Pallis, his accidental murderer, relents for his actions and holds his brother’s hand as he dies. Pallis’ remorse humanizes him at the last second; he’s not a cold-hearted killer, but a brother whose rage blinded him.

3. Equip the Villain With Smarts

An ingenious villain who seems to know everything about everything on niche topics may not make for a realistic character, but they do make for a memorable and interesting one.

Pallis is not present for most of the musical and so the audience doesn’t see many aspects of his character. However, when they do see him, they find out that he has somehow managed to track Adakias throughout his entire journey–a journey that involved crossing a mountain to a forbidden land, meeting hostile royalty, sailing a treacherous ocean, and finally, encountering an insane doctor. The fact that Pallis was able to track Adakias, keep up with him, and surpass all obstacles on his own speaks to Pallis’ intelligence as a villain.

Patterson’s angle on villainy claims that a successful villain must be three-dimensional, humanized, and intelligent. Pallis demonstrates all three traits in RS, and thus, he can be labeled a “successful” villain. This success is further demonstrated in Pallis’ popularity in the RS fandom, which is equal to or possibly even greater than Adakias’. Try analyzing your own villain with Patterson’s three tips. You too can make a villain both successful and memorable to your audience!

Sources:

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

MasterClass, and James Patterson. “What Makes a Good Villain? 3 Tips from James

Patterson (with Video).” MasterClass, 7 Oct. 2019,

https://www.masterclass.com/articles/james-pattersons-three-tips-for-writing-a-

great-villain#2-humanize-the-villain.

Purdum, Todd. “How James Patterson Became the Ultimate Storyteller.” Vanity Fair,

Vanity Fair, 31 Jan. 2015, https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2015/01/james-

patterson-best-selling-author.

0 notes

Text

The Bechdel Test in Razia’s Shadow

With today’s media recognizing more and more the importance of female representation, it’s becoming vital that stories do a good job of creating interesting and respected female characters, lest female audiences label the piece as “sexist” or ignore it completely. The Bechdel Test, coined by Alison Bechdel, is a short and simple test that rates if a piece of media exhibits adequate female-to-male representation. While the test is made for movies, you can apply it to your own storytelling format just as easily: novels, video games, comic books, etc.! To see how not to pass this test, we’ll look through the lens of musical Razia’s Shadow (RS), a musical that, though it has its strengths, sadly can’t say much for its female representation. Through our application, you, too, can learn how to avoid failing the Bechdel Test in your writing.

The Bechdel Test has three rules:

1. [The story] must have at least two named female characters.

2. Said female characters must talk to each other.

3. What they talk about must involve something other than a man.

Let’s begin with Rule 1. Out of 15 characters, RS features two females. While the male-to-female ratio already looks abysmal, RS technically passes the first rule. The female characters include Nidria, a gifted and talented angel, and Anhura, a princess who will help save the story’s world. Here we have two named female characters who, as a bonus, have plot relevance! However, neither are active characters; everything that happens in the story happens to them, not because of them and their choices. They make all their decisions in the company of other characters; they do nothing on their own. Already we see how RS alienates its female audience with so few female characters and such little agency given to them.

While RS barely passes Rule 1, it totally drops the ball on Rule 2 (and consequently, Rule 3). Nidria is Act I’s love interest, while Anhura is Act II’s. The two Acts take place a hundred years apart; thus, Nidria and Anhura can never meet. Because of this, they don’t have the opportunity to talk about anything, let alone something other than a man. To add insult to injury, Nidria and Anhura do not have any dialogue/lyrics that are not in some way about their significant others, the male protagonists. Nidria has only one song, and it tells us information about the male protagonist; we never learn about Nidria’s life except for that which revolves around her love. Anhura is treated much the same. When presented with the shocking truth that her significant other, the protagonist, has been lying to her for the entire musical, Anhura doesn’t have any kind of response. After this, the musical’s final interaction takes place between the protagonist and his brother; nothing from Anhura. By giving the female characters no chance to interact as well as have nothing to discuss other than male characters, the storytellers are, on a subconscious level, degrading the women. This is apparent to a female audience and further alienates those readers from the story.

RS is by no means a perfect story, and that’s made most clear by pitting it against the Bechdel Test. RS ignores the importance and agency of female characters, and by disregarding the Bechdel Test, the story ends up isolating half a potential audience. In a worst-case scenario, this could even generate backlash! Take the time to run this simple test against your work and avoid RS’ mistakes; it could end up saving your story!

Sources:

Bechdel, Alison. “The Rule.” DTWOF: The Blog, 16 Aug. 2005,

http://alisonbechdel.blogspot.com/2005/08/rule.html.

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romantic and Familial Love in Razia’s Shadow

“Tale as old as time,” love is a tool that has always been used in fiction. Whether romantic or platonic, love establishes relationships for a character; sometimes said relationships even become the story’s focus. Let’s explore through musical album Razia’s Shadow (RS) how both romantic (eros) and familial love (storge) can help enhance your own writing.

The primary message of RS is, as stated by the musical:

“The unrelenting constancy of love and hope

Can rescue and restore you from any scope.”

–“Genesis”, Lines 35-36, Razia’s Shadow

This message refers to the power of eros and storge. In RS, two halves of a world are destined to be destroyed unless they can be reunited. To reunite them, the protagonist must sacrifice himself to save his significant other, as well as forgive his murderer, his brother.

Here, eros serves multiple purposes. The audience gets to enjoy the light-hearted and relatable aspects of falling in love through the main characters’ relationship. In addition, eros fuels the drama of the journey. The protagonist, Adakias, falls in love with a woman from the other half of the world, Anhura. By the laws of this universe, she falls ill simply by being within his proximity. To save her, Adakias crosses an ocean, negotiates with an insane doctor, and finally, takes a dagger meant for her from his own sibling and thus, “fulfills his destiny.” Here, eros is a malleable tool: it presents a fun aspect of the story, drives the plot forward, and resolves the primary conflict.

In storytelling, storge is often ignored in favor of eros. However, as Psychology Today states: “By preoccupying ourselves with [eros], we risk neglecting other types of love that are more stable or readily available and that may, especially in the longer term, prove more healing and fulfilling,” (Burton). Storge is just as important as eros in our day-to-day lives; thus, it should be equally important in storytelling. This is why it’s so important that RS shows us how to use storge.

When Adakias leaves his home to find out how to reunite the two halves of the world, his elder brother, Pallas, tries to stop him. Pallas’ familial love here, though well-meant, acts as an obstacle for our hero to overcome. Adakias runs away to pursue his goal, and Pallas, hurt and enraged, pursues him. The betrayal of storge creates an antagonist that is both sympathetic and has an established connection to the protagonist. In the final act, Pallas catches up to Adakias and Anhura and attempts to stab Anhura. Adakias takes the blow, and only then Pallas realizes what he’s done and relents. In his last moments, Adakias forgives Pallas, and the two reconcile as the world is reunited. Storge acts as a trial, a catalyst for creating a villain, and as a solution to the plot. Like eros, storge creates many storytelling opportunities for the writer.

RS emphasizes the importance of love of both a romantic and familial nature throughout its entire plot, using the relationships that stem from it as tools in shaping its story. Whether showing different aspects of a character, creating conflict, or solving a problem, “love” is a force to be reckoned with in storytelling.

Sources:

Burton, Neel. “These Are the 7 Types of Love.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 25 June 2016, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201606/these-are-the-7-types-love.

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

0 notes

Text

Hero’s Journey in Razia’s Shadow

Have you ever been writing a story and just weren’t sure where to take it? Lucky for writers, there is a tried-and-true formula used since the dawn of mythos: the “Hero’s Journey.” First conceived by Joseph Campbell then simplified by screenwriter Christopher Vogler, the Hero’s Journey is a 12-step framework that can be used and manipulated to create a fully-fleshed adventure. Let’s look at how you can use this structure in your own storytelling through the musical Razia’s Shadow (RS).

1. Ordinary World

Adakias is a young prince who lives in a divided world, one half known as “The Light” and the other “The Dark.” Each world suffers without the support of the other.

The world of the story is introduced, as well an internal conflict that needs to be resolved.

2. Call to Adventure

Adakias hears legend that a “Chosen One” will bring together the divided worlds through an act of love, thus preventing the worlds’ mutual destruction.

The main character is presented with what he must do to resolve the conflict.

3. Refusal of the Call

Believing he is the “Chosen One,” Adakias is willing to pursue his destiny, but is stopped by his brother, who believes Adakias is chasing a fairytale.

Unlike atypical heroes, Adakias does not refuse the call; his family does so for him. By putting Adakias at odds with his brother’s wants, the audience can immediately sympathize with him and view overcoming his brother as one of his trials.

4. Meeting With the Mentor and 5. Crossing the Threshold

Two oracles, the Bawaba Brothers, explain how the world came to be divided and confirm Adakias’ suspicions about being the “Chosen One.” Adakias is determined to reunite the worlds, but is not sure how.

The brothers appear near the end of the musical instead of, as it traditional, the beginning, where they serve as an omen rather than encouragement (unlike most fictional mentors.)

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

Adakias falls in love with Anhura, a princess from “the Light.” The two elope, Anhura falls ill, and they are forced to cross the ocean to find a doctor.

Adakias prepares for the “central ordeal” by going to more and more extreme lengths for Anhura.

7. Approach

Adakias brings Anhura to the only doctor who can cure her, but the doctor refuses to do so unless she stays with him forever.

Adakias is challenged one more time before his central ordeal.

8. Central Ordeal

Adakias is met by a pursuer, his brother, who has chased him all the way from his home to this point. His brother attempts to kill Anhura, and Adakias steps in the way to take the fatal blow.

This is the greatest challenge Adakias must face.

9. Reward

After Adakias’ act of love, the divide between the worlds is destroyed and the two halves reunited.

The hero passes his final test, and though he doesn’t get to witness it himself, he is rewarded with mending the two worlds and saving them from ruination.

At this point, RS elects to skip the last three steps in favor of having a tragic but worthwhile death for our hero. However, I’ve included them so that you can choose if you should utilize them in your own writing.

10. The Road Back

The protagonist faces one last obstacle.

11. The Resurrection

The protagonist, now successful in their quest, is thoroughly changed. They return to the “ordinary world” a different person.

12. Return with the Elixir (The Goal of the Quest)

Now that the protagonist is armed with the “elixir,” they can use it to help the ordinary world somehow.

Through direct use, manipulation, reordering, or completely cutting certain steps, RS helps demonstrate that the Hero’s Journey is a flexible structure that, if you’re in a pinch, can help guide your own storytelling.

Sources:

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Michael Wiese Productions, 2007.

0 notes

Text

Religious Themes in “Razia’s Shadow”

If I asked you to summarize the story of Adam and Eve, religious or not, you could do so easily, right? What about Noah’s Ark? The resurrection of Jesus Christ? These are all widely recognized stories, thanks to belonging to the most practiced religion in the world, Christianity, and because of their notoriety, storytellers often use them to enhance their writing (Grim). Musical album Razia’s Shadow, or RS, demonstrates how the simple yet effective implementation of Christian references can help shape a story. Perhaps after seeing its use here, you may consider using it in your own writing.

RS’ Act I is built around Christian theology. In it, the angel Ahrima is trying to impress his God (O the Scientist) through making spectacular creations. While Ahrima’s fellow angels are impressed, O gives a lukewarm response. In retaliation, Ahrima destroys not only his own creations, but the other angels’, as well. As punishment for his destruction, the world is split in two, one half “light” and the other “dark,” and Ahrima is banished to the latter. Act II is then spent bringing the world back together through love.

Similarly, in Isaiah 14, Lucifer is described as being one of God’s most powerful angels before trying to rise above Him in glory and power. As punishment for his pride, Lucifer is cast out of Heaven. These stories line up so closely that Ahrima is clearly meant to parallel Lucifer. In the end, both stories use “love” to amend the divide: Jesus Christ, through self-sacrifice, comes to redeem humanity and restore their connection to God. In RS, Act II’s protagonist, Adakias, does the same. His sacrifice is performed through familial love for his brother and romantic love for his partner, thus allowing him to bring the “light” and the “dark” back together.

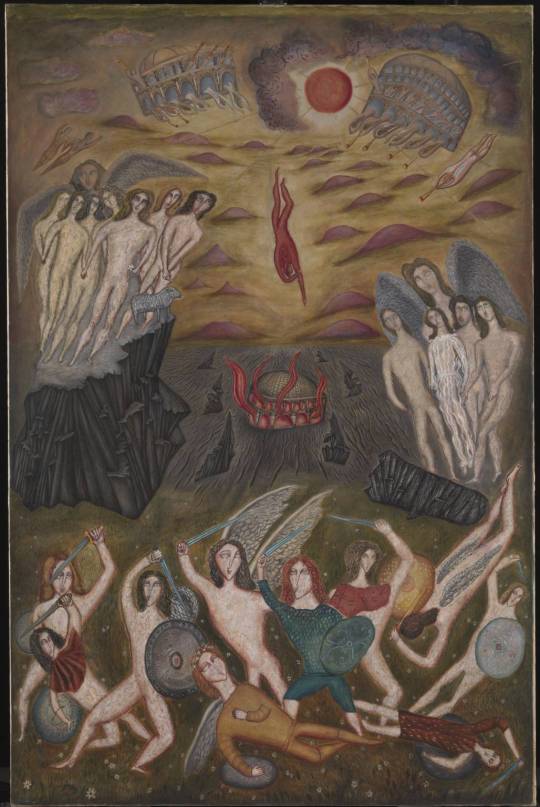

Fig. 1. Collins, Cecil. “The Fall of Lucifer.” 1933. Tate Archive TGA. Tate. Web. 11 Oct. 2019.

Why did the creators choose to write RS this way? Forgive Durden (the band behind the album) told their story through a musical, in which each song is only about 3-5 minutes. Time to get the musical’s story across was limited. By using religious allusions, they were able to give additional meaning to their work in a shorter amount of time. For example, the first song, “Genesis,” is an abstract song about the joy of creation; however, because of its title (a reference to the first book of the Bible), as well as the audience being told that O is the “architect” and Ahrima his “angel,” we immediately draw additional conclusions: O the Scientist is a god, and He and Ahrima must be creating the universe.

Forgive Durden uses religious allusions throughout RS to help the audience understand the world they’ve created, the rules of that world, and the relationships of the characters within it. By making comparisons to the widest religion there is, they quickly established several points in just a few words. This is a great skill to use in enhancing your writing so that you can spend less time summarizing and more time getting to your own ideas!

Sources:

Collins, Cecil. “The Fall of Lucifer.” 1933. Tate Archive TGA. Tate. Web. 11 Oct. 2019.

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

Grim, Brian J, and Hackett, Conrad. The Global Religious Landscape. The Pew Research

Center, 2012, The Global Religious Landscape,

https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/01/global-

religion-full.pdf.

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Biblica Inc., 2011.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Welcome to Razia’s Shadow!

What would you say if I told you that all the way back in 2008, Panic! at the Disco and Portugal. The Man, among other popular acts of the time, starred in a full-length musical? I’d like to introduce you to Razia’s Shadow (or RS, for short), an album released by indie rock band Forgive Durden (Limykelsy). Though you may have never heard of this musical before despite its stars, I would like to show you its merit through its dedicated fanbase and explore the reasons it may have gone unnoticed; then, just maybe, you’ll be interested in showing it a little love, too.

(Pictured: Album Cover Art)

There were multiple factors at play for RS’ limited reception. Forgive Durden had formed only two years prior to RS’ release and had one album; their audience had barely formed. In addition, their existing album had been created for punk rock audiences, not musical theater fans, and so any preexisting fans were met with something completely different than what they’d grown to love. As if this shaky foundation wasn’t enough, the band was falling apart by the time RS was conceived. Of its four members, all quit save for the original creator of the band and the musical, Thomas Dutton (Paul). With no band-mates left, Thomas had to turn to his brother, Paul, who was away at college studying music composition. Over weekends, Paul would come home to assist his brother alongside music producer Casey Bates (Paul). Under record label Fueled by Ramen, Thomas would recruit other musical acts of the time to serve as the cast, such as the aforementioned Panic! at the Disco and Portugal. The Man, as well as The Hush Sound, The Dear Hunter, and Say Anything, among others (“History of…”). Despite this All Star lineup, Forgive Durden hadn’t accrued enough of an audience yet for the musical to gain attention upon release. However, those who noticed the musical, like myself, realized they’d stumbled upon a diamond in the rough.

RS was met with (though little) positive reception. It is difficult even now to find any mention of sales numbers or official reviews, but, if you’re inclined to trust Wikipedia, the site hosts links to AbsolutePunk.net and Highbeam Review as having scores of 86% and a 9/10, respectively–the linked pages have since been deactivated and are no longer accessible from the Wayback Machine (“Razia’s Shadow…”). The most positive response to the album was a fan-made production using carefully handcrafted, fully-articulated puppets (FocusOnUProduction). Though the production has been taken down, you can still watch the crew interview here. Despite its inattention, fans and critics alike raved over RS.

RS is a beloved and well-crafted, but sadly ignored, album. Despite its shaky release, the musical is solidly made, which is reflected in the love of its critics and fanbase. Though you may have never heard of this album before, I hope that by seeing all the love and effort put towards this musical, you might just be intrigued to check it out, too.

Sources:

FocusOnUProduction. YouTube, YouTube, 1 Apr. 2011,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uNnAFqdHcaw.

Forgive Durden. Razia’s Shadow. Fueled by Ramen, 2008.

“History of Razia's Shadow.” Razia's Shadow,

http://www.raziasshadow.com/story.html.

Limykelsy. “About ‘Forgive Durden’.” Genius, 2018,

https://genius.com/artists/Forgive-durden.

Paul, Aubin. “Forgive Durden Overhauls Lineup, Records New Album.”

Punknews.org, Punknews.org, 24 Sept. 2019,

https://www.punknews.org/article/27540/forgive-durden-overhauls-lineup-records-new-album.

“Razia's Shadow: A Musical.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 July 2019,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Razia's_Shadow:_A_Musical.

8 notes

·

View notes