#'it's cultural appropriation' not when they are explicitly invited to participate

Text

Hey to people who try to push non Natives out of public events that the tribe itself purposefully is letting be open to outsiders please shut the fuck up

You are not the authority on this. The tribe itself, ESPECIALLY tribal elders, are. And if they want to let people in on parts of their culture that is their decision to make and you do not get to override that.

#'it's cultural appropriation' not when they are explicitly invited to participate#they are not stealing anything when they are invited in#native#native american#native american issues#indigenous culture#indigenous american

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

B’nei mitzvah in spaceship without Jewish community | Jewish character celebrating Christmas

Hi! Thank you so much for running this blog. I appreciate how much time and effort all the mods have put into it. I finished reading through the whole Jewish tag a few days ago, and I’ve learned so much! I’m writing a Voltron fic (I *know* lol) and decided to make one of the protagonists a white nonbinary Ashkenazi Reform Jewish girl. Her astronaut brother mysteriously disappears in space and is presumed dead, so she runs away from home a couple of months before her b'nei mitzvah to find him. Now, she’s in a group of rebels in space fighting against an Empire. I have two concerns:

1. Everyone on the ship misses home, so part of the way they cope is through getting in touch with their cultures. They’re gonna celebrate (a mostly non-Americanized) Christmas because it matters a lot to some of the characters for non-religious reasons. To what extent can my Jewish character participate in the celebration without it being weird? I want her to enjoy herself more because she’s with her friends than because Jesus etc. They’ll also celebrate Chanukah, if that helps. I know Chanukah isn’t a major holiday, so I also want to have her celebrate a more significant one like Rosh Hashanah and/or Purim with them. Is it okay for gentiles to participate in those holiday celebrations, or should she do that alone?

2. Throughout most of the story, she’ll struggle with choosing whether to prioritize fighting the Empire or finding her brother and bringing him home. When she eventually does find her brother (who also turns out to be a rebel), he lets her decide whether they stay or go home. I thought it would be nice if she decided to stay and keep fighting for the greater good after she finally has her b'nei mitzvah. Her friends and other experiences are also a big part of why she decides to stay, but the b'nei mitzvah would be what gives her the final push she needs to decide. I don’t know if it would be okay for me to write the ceremony itself or if she can even have one if only two of the eight people on the ship are Jewish. I read that not everyone has a b'nei mitzvah and that it’s not required, but I feel like it’d be a big deal to her character. Should I keep the b'nei mitzvah idea, or am I heading towards appropriative territory here?

I want to make her Jewishness a big part of her character’s growth, and I really want to make sure I do it respectfully and accurately. I plan on finding a sensitivity reader when I’ve made more progress with actually writing everything out. Thank you for any insight you might offer!

It feels off to me to join a community symbolically when you’re far away FROM the community. Why not just have had her already have done the ceremony before she has all these adventures? That way it could just be a straightforward story about a Jewish teen having exciting heroic adventures in space, rather than a story about what happens when you have to miss aspects of Jewish life because you’re in space. It would also make the “….well, I guess I’m around for Christmas” bit less weighted because then that would be the only one of those instead of having two of those.

–Shira

I’ll cover some other territory here. For those who don’t know, b'nei mitzvah is something you just automatically become at the correct age, the ceremony is simply to celebrate that with the community. Not all people have the ceremony, but if you are Jewish, and of age (for religious purposes), your status changes with or without it. Personally, I’m comfortable with showing a Jewish character finding a way to have a Jewish celebration when the circumstances are less than ideal, for me the other aspects of the story are more troubling.

On the subject of having a Jewish character celebrate Christmas with their friends… look I don’t like this trope. There are many Jewish people, who are completely secular, who don’t celebrate Christmas, because it is explicitly a Christian holiday, and secular Jewish people are still Jewish. Some Jewish people (secular or otherwise) do choose to celebrate other holidays, and I am very comfortable with those folks telling their own stories. What I’m not happy with is the push from outside of the community for every Jewish character to slide into assimilation.

Some Jewish people will go to Christmas parties and not eat the food, because they keep kosher, or won’t stay for a tree-lighting, because that feels like it goes too far, or will give presents but not receive them. There are a huge number of ways we might handle Christmas, and I appreciate that you plan to show holidays other than just Chanukah (and yes, it’s fine for non-Jewish characters to join her in her holidays, if she invites them), but I always question why a non-Jewish writer is so keen to show Jewish characters celebrating Christmas. The most generous version of me wants to assume that you get so much out of Christmas that you want to share it, but the part of me that knows about the pressures to assimilate, and the history of increased antisemitic violence around Christmas thinks… just leave this kid alone. She missed her celebration, she’s far from her community, and now she has to go put on a Happy Assimilated Smile for the culturally Christian folks around her.

From a nonbinary Jewish perspective, it’s a little unusual for your nonbinary character to use she/her pronouns, and use b'nei mitzvah as a gender neutral alternative to the gendered bat mitzvah. In secular life, at least in the US, it’s not uncommon for people to use multiple pronouns, but I haven’t met, or even heard of, a single person using gendered pronouns secularly, and using new neutral alternatives religiously. It absolutely could happen but, because it is so unusual, to me it reads as either invalidating the character’s gender, or tokenizing her in the religious sphere.

–Dierdra

Shira, I think that’s a really good idea to make the character post-b'nei mitzvah. That way you just have a Jewish character having adventures rather than her culture being The Conflict. (And also, a pre-b'nei mitzvah seems a bit young for this storyline? Can she really consent to fighting alongside the rebels? Do they habitually take unaccompanied children on their ship? To me a teenager would make more sense, but hey it’s not my story!)

Dierdra, your answer regarding the Christmas aspect was awesome and really thorough. Thanks for your thoughts on the pronouns as well, it also jarred with me but I was waiting to hear your opinion as you have lived experience. My worry is if you use gender neutral terms for one but not the other, you risk falling into to the stereotype that only marginalised religious folks have to change our language etc to be inclusive to LGBTQ+ people, but everyone else is fine.

I wanted to come back to the point about Rosh Hashana. First of all, thank you for acknowledging that we have holidays that are more important than Chanukah! Sooo many OP’s don’t know that. In terms of how she would celebrate it, I agree it’s fine to invite non-Jewish people along. However, given how community-based Jewish life is, making her keep Yom Tov on her own feels a bit like a torture story, especially when others have people to celebrate Christmas with. I wonder if you’ve thought about giving her a Jewish friend on the ship? Especially if you want her Jewishness to be part of her growth as you mentioned, an older Jewish friend and mentor could be a huge help :)

–Shoshi

As you can see, we have a wide range of possibilities for “what happens when you ask a Jewish person about celebrating Christmas.” I didn’t mind hanging around it as an outsider myself until a certain subset of Christians started being mean-spirited about it in the news plus some personal trauma that time of year, as long as everyone involved was clear that I was just participating from the outside and this didn’t somehow change me. (If I may make an analogy: compare it to going to a baby shower when you want to support your friend or family member but also really don’t want kids of your own. You’re going to have a whole different experience if your decision is respected vs. if all the other guests treat you like you being there means you’ll change your mind about not wanting kids.)

That being said, it’s still all over the map. Some people IRL are okay even going to mass with their partner’s Catholic family (without participating in communion obvs.) Some would never, ever do that and are sitting here with shocked faces that I even typed that. But what becomes important is the way it’s written. Sitting around listening to the Christmas story is probably a bad fit for your fanfic, but helping other people bake Christmas cookies or put ornaments on a tree could work. The ornament thing could remind her of decorating a sukkah, and she could point that out to the others.

I guess I’m saying is

keep her participation secular, and

keep her participation from leaning into the idea that we’re unhappy with our customs and would prefer to do it their way.

I have literally never in my life felt jealous of the kids who “got to do Santa” (for example) and while I’m sure some kids were and they’re valid too, I think it’s important to show that it’s not a universal phenomenon.

–Shira

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Punk Rock in Marxist-Leninism

As far back as I can remember, I’ve always hated punk rock; the reasons why having changed significantly. I heavily identified as Right-wing throughout my childhood through early adolescence, so punk rock was a piece of culture that I quickly realized was not for me, with its far-left anarchist aesthetic. If you’d shown and explained to me something like Holiday in Cambodia I wouldn’t have cared in the slightest. Anti-fascists often forget about how the far-right rarely considers the vast and vapid categorizations of different leftists and other anti-fascist types. Anarchists are just as anti-American as Stalinists; anarchists just don’t have a plan (besides the occasional riot) so they’re more docile and easier to ignore. They’re just extra annoying and snobby. The sonic elements of punk mixed in with the political atmosphere sealed it for me. I thought this entire genre of music sounded like some twerp in class who says shit about America just to ‘piss off the system’. Childish, really.

In high school, the first punk band I didn’t immediately hate was neo-Nazi band Skrewdriver. I was introduced to them on a bus for school, with only one black kid on the whole bus, having the song White Power being shown explicitly to them. I remember referencing it to him later in conversation and he said he hated that experience. To me though? Finally, I thought, some punk rock where I can very easily say ‘well I like the music, but I don’t like their politics’ and it isn’t SJW crap. If I were to say stuff like that about other punk rock bands that’d be blasphemy, so I avoided the leftists and found more Nazi punk, where the bad politics were more obvious.

As someone who’s always been into music, my childhood had a specific opinion that I now understand to be just a simple analysis- namely, that politically left-wing music doesn’t do anything to change the system whatsoever. On an open-mic day in my high school the buses had already arrived and then my band got to play Killing in The Name. The school, the ‘system’, allotted us more time because they wanted to hear a cool song. Nobody was inspired by that song that day to think critically about the condition of militarized police in America or how the Klan’s ideology controls the majority of America’s police. I know I didn’t. Frankly, I thought putting politics in music was a waste of time Right or Left. And I found more Rightist music later on, namely in black metal.

Black metal is a mirror image of punk, if that mirror were on two ends of a horseshoe. Both started out as what we today label ‘edgy’, yet generally non-political, and then got somewhat overtaken by the far right and far left. Black metal was firmly cemented in Nazi ideology by the mid-90s with Burzum and the history of the Norwegian second wave, as well as later bands like Germany’s Absurd to solidify National Socialist Black Metal as its own genre. Then there’re wackos like Peste Noire, who, with the help of figures like Anthony Fantano, are somewhat normalized and mainstream while also having deep French nationalist roots. But what makes black metal also similar to punk is the later insurgency movements from either political side into the other genre. Nazi punk distinguishes itself not by its members being skinheads, for skinheads began as a far-left movement, but rather with aesthetics like white and red shoelaces (wrapped straight) and, of course, swastikas. In the mid/late 2010s an anti-fascist black metal scene emerged in response to the atrocities of the Obama administration and Trump’s election victory. This was spearheaded by bands like Gaylord and Neckbeard Death Camp as well as others from Bandcamp and Soundcloud. It didn’t try to distinguish itself at all, in a crypto-anti-fascism directly proselytizing. Nazi punk and anti-fascist black metal are similar in that they, like all music as we’ll be seeing, also don’t achieve anything, but are specifically trying to change the strata of their own genre’s political associations. As my own father put it, there’s only two kinds of Oi – racist and non-racist.

Left-wing black metal was obvious folly that I participated in anyway. But even when I eventually started putting personal politics into my music from 2016 through 2019, I still avoided major bands like Rage and punk rock (besides Bad Religion, which I only liked because I saw a live cover). It was actually Peste Noire who showed me the wonder of sampling in music; yet another far-right appropriation of musical technique, sadly. It was only in late 2019 and 2020 that I listened to bands like Rage and Dead Kennedys, and seeing the amount of effort they put in their messaging left me cynically giggling. Paraphrasing other commentators, music has no effect on political change no matter how radical. Far-left Marxist, Bolshevik, anarchist and Social-Democratic musical compositions have existed since the nineteenth century and were plentiful in the entirety of the 20th century, albeit with significant change after the World Wars. But music is too individualistic to be politically effective as every individual person’s preferences are different. This is how Rage and anarchist punk rock sold so well in America and how I continued to enjoy Peste Noire long after I left the Right.

My music was also inspired by industrial metal band Rammstein, and I’ve since learned that, generally speaking, politically provocative art is an integral part of industrial music generally, which easily puts off someone not paying careful attention to the music. To paraphrase Žižek, artists like Rammstein and Laibach use fascistic language and imagery in a controlled way that lifts various signs from their associations of authoritarianism, leaving them inoffensive enough to gain mainstream credibility. Case in point, Slovenia’s Laibach has caused numerous controversies over their 41-year-career with their overtly militaristic theme, prolific German lyrics, and for having been branded as dissidents by the Yugoslav government, yet they are the only foreign band that has ever performed in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. They were invited to play in 2015 to celebrate the 70-year-anniversary of the fall of imperial Japanese rule on National Liberation Day. The government would clearly know better than to invite a legitimate fascist band; in their minds that would most certainly create an immediate attempt to try to cause some type of western imperialist unrest. One would wonder why they’d invite anyone at all. But nothing malevolent came about from it; the show went fine, and clips of it are on YouTube. I won’t try to make any comment on any individual in the DPRK or anywhere else, but it’s fascinating to think of what happens when Laibach is played through North Korean speakers, interpreted by those who have few else in common with the band other than they both have experience living under a régime inspired by Marx.

It must be a different experience from, say, the experience of Anarchy in the UK by Sex Pistols as sung on North Korean karaoke by VICE journalist Sam Smith. This leads me to my current gripes with punk rock, specifically in the year 2021.

Sex Pistols are the origin of punk rock’s association with anarchism due to the song mentioned above, but they are also the origin of punk rock’s association with Nazism due to Sid Vicious’ use of a swastika t-shirt. This is no paradox. Both are a result of Liberal nihilism, of having no true political leaning other than blind offensiveness and ideological motivation without one ever needing sincerity in belief. Either that or punk rock bands are explicitly Liberal/conservative, which is a discourse I remember from my childhood. Post-90s punk was too commercial, liberal, gay, et cetera, with bands such as Green Day having been seen as a perversion of the solidarity of the mostly cisgender heteronormative anarchist community of people who actually listen to punk rock. John Lydon is an open Trump-supporter. After the far-right January 6th attack on the Capitol, Dead Kennedys retweeted many Liberal commentators and politicians, including Republicans Mitt Romney and Arnold Schwarzenegger. I see not a problem with individual people and artists but a problem with punk rock as artistic expression; it has terminal hollow conformity. Overall, its association with petit bourgeois ideology leaves punk rock with little to give it credibility. Punk rock has always had an insincere, two-faced nature. ‘Punk’s not dead’ is the anti-fascist equivalent of ‘return to tradition’…or is it anti-fascist? Depends on who’s saying it, where’s being said, and who hears it.

Where to turn? Marxist-Leninists (and sometimes even anarchists) will argue that social bureaucracies such as Cuba, the People’s Republic of China, Vietnam and the DPRK provide an alternative to American global homogeny. Considering the American military spent over $700,000,000,000 on its military last year, and that many bases are specifically placed around those listed countries, their arguments aren’t entirely unconvincing. They also argue that because Marxist-Leninist politicians provided industrialization and progress for their nations without what Marxist-Leninists would personally term “imperialist war”, they should be praised, as well as the fact that many of the problems commonly associated with those countries are explicitly from American intervention to stop ‘the spread of Marxism’ and to keep them subordinated to western authority. However, as Bordiga writes in Characteristic Theses of the Party, the integral realization of socialism within the limits of one country is inconceivable and the socialist transformation cannot be carried out without insuccess and momentary set-backs. The defence of the proletarian regime against the ever-present dangers of degeneration is possible only if the proletarian State is always solidary with the international struggle of the working class of each country against its own bourgeoisie, its State and its army; this struggle permits of no respite even in wartime. This co-ordination can only be secured if the world communist Party controls the politics and programme of the States where the working class has vanquished.

Am I arguing for left unity, left solidarity, the whole “anarchists and Marxist-Leninists are going for the same communist goal” argument? No, I’m not talking about that. This has been said before but, historically speaking, there’s usually only one correct way to pilot a vehicle and thousands of wrong ways. But I’m talking about music. And I bring up Marxist-Leninism for what could be seen as a superficial reason; that the potency of Musikbolschewismus is greater than the potency of traditional anarchist punk rock. If we’re just talking about music to ‘piss people off’, which is what punk rock culturally amounts to, punk rock could be Marxist-Leninist in that that ideology has more of the nihilistic punk rock mentality than any band you could name. Because Marxist-Leninism can indeed be quite nihilistic, with Russian Bolshevik minority rule in foreign countries paralleling the worst aspects of American imperialism and its related apologia. As for industrialization, the USSR demobilized its military to a lesser extent than other European countries, organized more strictly than NATO. Their industrialization in question was related to impersonal and heavily regulated bureaucratic trade, the aforementioned occupation of eastern Europe and elsewhere, and warcraft: firearms, lightweight tanks, and thousands of nuclear weapons. In 2021, the history of Marxist-Leninist music is both far more potent and plentiful than anarchist punk rock; if a bit old-school, boringly classical, and used in the justification of unjust countries.

What I’m trying to say is this: what is the difference between an English band that wears swastika and MAGA t-shirts singing about how anarchy is good and another band that wears sickle and hammer shirts singing about how the USSR and the PRC are good? Both are nonsense but the latter is sincere with what they say… or are they? Considering punk rock’s edgy, yet ultimately cowardly and insincere anti-authority outlook, I can’t help but wonder what would be if Marxist-Leninism were to ever embrace the potentiality of its status and flaws and make annoying, loud guitar music. It wouldn’t be hard since, comparatively, the bad politics are more obvious. And once it gets started, it’d create a new cycle of the entirety of political thought in music; easily being able to be superior to Right-Libertarian punk rock and all the washed-up bands of the 70s-00s.

What’s the actual transgressive music we have today? Rap music has been mostly dominated by black Americans since the 80s, with a lot of rappers now being women. It is held to a different esteem than even the antisemitic ‘satanic panic’ of the 80s against heavy metal, since legal cases referring to rap lyrics are not unheard of and can even lead to conviction in modern times. It is much closer to the struggles of the global afro-diasporic community than with European writers from 80+ years ago. Punk rock never had, never could, and never will, have a scene of that calibre.

In conclusion, I hope I have provided a cynical pseudo-rehabilitation of punk rock through the example of Marxist-Leninism in a specific manner related to the overall creation of and interpretation of music, which is an important piece of international culture. I know Marxist-Leninist States to be corrupt and are not socialist, but to the eyes of an American, and to the ears of the average punk rock normie, Marxist-Leninism is just as anti-US government as the anarchists, only scarier, because they actually have a plan! So why can’t it be punk? The PRC’s State-sanctioned abductions are certainly not what Bordiga had in mind in regards to a proletarian government being against its own bourgeoisie. Internationality is the way forward. But it almost sounds like it’s against the system if one has that kind of understanding of ‘the system’. Who’s to say there isn’t an obscure 80s punk demo labelled Kidnapping Billionaires somewhere? Punk rock is nothing more than vapid noise to piss of conservatives. That’s it. It has no heart, spirit nor philosophy. The PRC even saying they would like socialism is too far for American conservative wormpeople, and legitimate reasons to criticize the PRC and other social bureaucracies get overshadowed by imperialist greed and racism. Music is not nearly the kind of tool of radicalism Zack de la Rocha thought it was, but with the internationality of Laibach we see it can do more than one can normally expect. It all depends on whether people can distinguish/separate the instrumentation from the proselytization.

#punks not dead#yes it is thank goodness#writing shit#music shit#nazis#racism#black metal#industrial#LAIBACH#rage against the machine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musings on viewer identification and spectatorship in Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018)

Bandersnatch is a beast of a film and I am surprised I haven’t seen more academic essays and film analyses of it. So here’s me taking a break from your regularly scheduled fannish content to take a stab at it:

First and foremost I'm here for investigating the relationship between the audience and the screen, how the audience participates emotionally in their experience of a cinematic narrative, how the audience identifies themselves in relation to a character on-screen... perhaps, even, how the audience then continues to engage with the media they consume outside of the immediate viewing experience in a larger cultural context

And sure, these are questions that come inherently with the territory of film. Any good movie should lend itself to such thought exercises about the form, and any good screenwriter should be contemplating such questions before they lay their fingers to the keyboard (one of the first rules I learnt in Howard and Mabley's The Tools of Screenwriting: films naturally invite audience participation, and when used appropriately, it's a formidable tool in cinematic storytelling).

But Bandersnatch not only lends itself to discussions of questions of audience participation - it deliberately asks such questions through its unique form, it plays around with audience participation in such a way that even the untrained eye is made to look twice at this experience...

(1) Bandersnatch is made for active and literal audience participation

Bandersnatch doesn't ask you to invest yourself emotionally in the plot, it doesn't ask you to identify with the protagonist, so much as it drops you feet-first into the thick of it - inviting you to cross the fourth wall and become Stefan at every single choice point

(this approach takes inspiration from the video game RPG format, of course, but every other aspect in this narrative adheres to cinematic conventions, it's almost like Charlie Brooker evolved a hybrid form in writing Bandersnatch. And besides...)

(2) Bandersnatch is simultaneously metafiction that questions the idea of cinematic identification

There's a weird tension in the RPG format, you are at once experiencing the narrative in the limited tunnel-vision POV of the protagonist, and making choices for them with a sort of bird's-eye view awareness of other possible outcomes if you so choose to explore other paths. But this tension has never been so clearly illustrated as here in Bandersnatch: upon every revisit of the film you are making your choices with prior knowledge of the narrative's general direction, with the film deliberately pushing the viewer to explore other options and pathways. Because of the film's form, the audience's experience becomes one of cognitive dissonance - we are at once invited to become Stefan, and yet reminded at every turn that we will always maintain a distance to the characters on-screen, for the power and the somewhat omniscient knowledge we hold over them is a clear reminder that we exist on a different plane of reality, peering into their world through a fourth wall that was never really broken, merely lampshaded.

(3) The medium-typical visuals in Bandersnatch serve to highlight its metafictiveness (and further drives cognitive dissonance in the viewer's experience)

Unlike the video game format, the cinematic form can never quite adopt the fully-immersive POV visuals that, say, a first-person shooter game could. Conventions of the medium, e.g. mise-en-scene, wide / medium / over the shoulder shots whenever 2 on-screen characters are in conversation - even POV shots, which are quickly followed by objective shots in observance of the Kuleshov effect, none of these types of visuals come close to delivering the immersive experience that first-person video games can provide, which quite literally frames the narrative, from start to end, through the eyes of the protagonist.

The Kuleshov effect used in Bandersnatch. A POV shot is enclosed by two shots of the character whose gaze the camera temporarily adopts. Notice how by panning out to show Stefan's back, the camera distances us from Stefan's perspective once more, so that we are effectively watching over Stefan’s shoulder and not through his eyes as his story unfolds.

Every time the camera shows us a medium shot or a close-up of Stefan, Bandersnatch inevitably reminds us that we are always going to maintain a distance from Stefan as a character. We do not become Stefan, we make decisions for Stefan remotely, and this puts us directly at odds with the impulse to participate in a film via identifying with the characters on-screen.

And the idea that we are supposed to occupy a role separate from Stefan as we participate in this film - it is not just something me and a dozen other essayists have been speculating about. This is an idea that, I believe, is fully intended by Brooker and his team. If you pay attention to the film's script and visuals, Bandersnatch tells us this explicitly, particularly in the pathways where the film gets meta about its nature as a Netflix title:

(a) the script: after Stefan asks for the viewer to “give me a sign”, if you chose the Netflix logo, the dialogue confirms for us (Stefan says it and so does Dr. Haynes) that we are an external force from the future, making decisions for Stefan remotely. Stefan is then revealed, even on the level of the in-text universe, to be a fictional character played by an actor called Mike - nothing more than the sum of well-acted lines of dialogue and movement, which rather throws a wrench in a viewer's attempt to identify with Stefan as a person if you ask me.

(b) more importantly, the visuals: if you unlock the 5/5 stars ending, we see that Pearl's in-universe copy of Netflix Bandersnatch contains the same opening shot of Stefan waking up on 9th July 1984 as we witness at the start of the film. This literally adds one more layer of fourth wall between us and Stefan's character as we realise the screen through which we have been viewing his story is actually further enclosed in Pearl's computer screen, further driving home the insurmountable distance between us and Stefan's character.

(4) Bandersnatch delivers on the central conceit of spectatorship in Black Mirror* - and elevates it

There's a distance between us and Stefan, because we were never Stefan, nor were we ever even in control of Stefan - merely spectators of his tragedy.

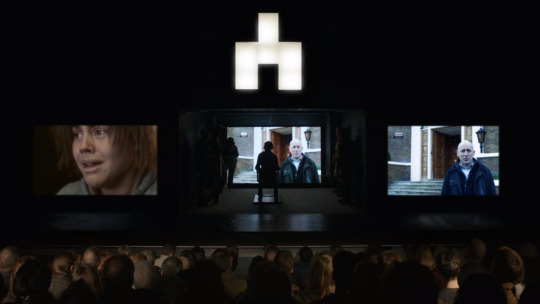

In true Black Mirror fashion, Bandersnatch subjects us to a complicity in other people's suffering by emphasising that we are in fact viewing their stories through a screen (within the screen). Think of S1E01 "The National Anthem" - how that episode embeds footage of the Prime Minister's struggle and eventual humiliation within TV screens on-screen as he concedes to the terrorist's demands, and in doing so, places our gaze from the perspective of the UK public passively spectating the events of his tragedy.

Or, think of how S2E03 "White Bear" ultimately places our gaze in that of the camera phone-wielding park-goers, who film and derive voyeuristic pleasure from Victoria's suffering.

At the reveal, the camera transfers our POV from Victoria's to that of the audience in the theatre. She is physically enclosed within the three walls of a traditional stage, and we peer in through the fourth wall (in addition to the fourth wall of the screen we were already viewing this episode through).

Victoria's live reaction to her criminal past is then broadcast on a screen for the audience's viewing pleasure - a screen within our screens that also adds another layer of fourth wall.

This idea of spectacle*, of course, is thematic of the show - the overarching commentary on our tendencies to consume, through the black mirror-screens of our viewing devices, incidents of no small consequence captured on news and social media as if they were merely reality TV entertainment.

What Bandersnatch does though, is that it doesn't just force us to watch as characters inevitably spiral towards tragedy and then call us out for deriving entertainment from the process. Bandersnatch takes it one step further. Its interactive feature tricks us into believing that we can shape the course of the story towards better endings, so that we are invited to experience this Black Mirror episode not just as passive spectators, but as active voyeurs whose participation causes the tragedy.

And that, I believe, is Charlie Brooker and co.'s intentions when they created Bandersnatch: to place us in a position where our relationship to Stefan's character is to be a voyeur of his tragedy. We are not Stefan, we do not become Stefan, nor do we get to shape his story in radically significant ways* - because just like Stefan, we are also bound by the limitations of the script we have been given. All we can do is spectate as Stefan's tragedy plays out, further exacerbated by our participation. It's symptomatic of Black Mirror's central conceit: we are all victims of a culture of spectacle that rules our everyday experiences of media consumption and our relationships with other humans. Likewise, Bandersnatch holds up that black mirror to our reality, almost as if to say, we are all Pac-man in the end, all we can do is consume, and in turn, be consumed by others as sources of entertainment.

(*) Notes:

When I say that we cannot shape the story in significant ways, I am only referring to the events of the story as they objectively happen on screen. I am aware of Roland Barthes's idea of "Death of the Author" and how the audience gets to be the author when we decode the meaning behind a scene and event and interpret a text according to our personal experiences of the story... But in the case of the choice points and outcomes we are presented with in Bandersnatch, Charlie Brooker holds the pen as the author of the film's pathways.

When I talk about the theme of “spectacle”, I am referring to the idea outlined by Guy Debord in his seminal work, The Society of the Spectacle. “The spectacle is not a collection of images; rather, it is a social relationship between people that is mediated by images." It’s this idea that how we engage with each other as individuals in modern society when our relationships are increasingly contextualised by mass media, consumer culture, and commodity fetishism. Lots of big buzzwords there, so for a crash course on this theory and how it relates to Black Mirror I highly recommend checking out Youtube channel Wisecrack's oldest video essay on Black Mirror.

I am also currently working on a separate meta to address the idea of spectacle in Bandersnatch, all the ways Bandersnatch inherits the hallmarks of a typical Black Mirror episode, and why the movie belongs squarely in the anthology. I will hopefully post it soon so stay tuned!

#black mirror#bandersnatch#stefan butler#black mirror meta#bandersnatch meta#don't fail me now tumblr; i had to repost this so it would hopefully show up in tags#white bear#the society of the spectacle#Eugenia writes meta#long post#Black Mirror Bandersnatch

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midsommar spoilers ahead – read at yer own risk.

This post contains discussions of suicide, murder-suicide, graphic ritualistic violence, dissociation and mental illness. These are triggers that also apply to the film, so please be careful if you decide to go and see this film.

I went to see Midsommar last night. I thought it was a fantastic film, that raised a lot of interesting themes about gaslighting, dissociation, belonging, fascism and free will.

I’ll start with the cinematography. This film is gorgeous. The scenery is so beautiful it’s almost unbelievable – rolling greens and constant blue skies. Probably not the normal setting for a horror film, right? Compare this to the cinematography of Aster’s other film, Hereditary, with its bleak, oppressive constant grey-tone, and you’d be forgiven for thinking that Midsommar was a departure from the horror genre all together. This works in Midsommar’s favour, though. It’s horror in broad daylight, constant daylight. I think it’s important to remember that the horror genre is not, and should not, be limited to just gruesome torture porn, or an endless assault of blood, gore and guts. I mean, I like bloody horror as much as the next person, but that is not where the genre should begin and end. Of course, Midsommar has some incredibly gruesome aspects (meaning that in Britain, the film has received a rating of ‘18’). The suicide of the two elderly members of the Hårga is played on screen with an unflinching gaze, and it is about as shocking as shocking gets. Especially when the elderly man jumps in such a way that he doesn’t immediately die, and instead shatters his legs. The other Hårga members caving in his skull with a large wooden mallet elicited pained gasps from many of the people sat in the cinema with me. It was brutal. But the main thing I took away from the film was an unrelenting reminder that grief is a transformative experience – not always for the better – and that vulnerable people can be drawn to bad people, bad organizations, or to make bad decisions, and we must question whether this means they are irredeemable.

This is actually where I started thinking about free will. The Hårga are a community bound by tradition. Their lives are to be a predetermined length, and within this, their lives are divided up into four ‘seasons’ of equal length. At the end of the winter of their lives, the period spanning 54 years old to 72 years old, you are expected to walk (literally) willingly, and freely, to your death. This is exactly what the two elderly members I just mentioned do. They are carried on sedan chairs to the top of a cliff, and then throw themselves to their deaths. Whilst I must be careful of cultural imperialism, I couldn’t help but wonder how much agency the Hårga have. Is this suicide an expression of free-will or an example of coercion driven by traditional practice? We can only speculate, but I wonder what would happen if someone refused to die at the predetermined age. This really cemented to me that the Hårga are not a peaceful community living in a psychedelic Swedish plane, but are in actuality, uncomfortably close to eco-fascism.

According to eco-fascist ideology, you’re expected to sacrifice your life in order that the group more generally can protect the interests of nature more broadly. This goes some way as to explain why the elderly members of the community, who are statistically more likely to be suffering from disease, ill-health or infirmity, are coerced to take their own lives. They have fulfilled their purpose, and they are invited? forced? to remove themselves from society. This is, of course, a society that is absolutely, entirely white. The only non-white bodies in the community are those of Josh, Simon and Connie – and these people end up dead, murdered in increasingly disturbing ways. Josh is killed whilst trying to take pictures of the Rubi Radr (the sacred text of the Hårga) – something he was explicitly forbidden to do – and his body is dragged away by a member of the Hårga who is wearing Mark’s skinned face as a mask. Connie and Simon both disappear at different points in the story, and both turn up dead. Simon is executed in a particularly graphic way – he is suspended in the chicken coop, as a blood eagle. The blood eagle is a form of ritualistic murder detailed in the Germanic and Nordic sagas, wherein the ribs are broken and the lungs are pulled out of the body, in such a way so that they look like ‘wings’. Simon’s lungs seem to inflate and deflate, as if they were breathing, but we cannot be sure whether he is still alive, or whether this is caused by Christian’s drug-addled brain.

This is where the film becomes uncomfortable for me. Connie and Simon are … very minor characters in this film. They don’t really serve any purpose other than to be tormented, murdered, sacrificed. They do not really interact with the main protagonists (Christian, Dani, Josh, Mark), other than a few pleasantries at the beginning, a shared horror at the suicide of the elders, and a very brief interaction between Connie and Dani when Connie discovers that Simon has ‘left the commune without her’. I am uncomfortable with calling Midsommar an explicitly feminist film as I believe the treatment of Connie, a sidelined, innocent, brown woman, who is brutally killed for no apparent reason other than her status as Other violates any claim the film might otherwise have as being explicitly feminist. But maybe this isn’t the point. I don’t think Midsommar has to be ‘explicitly feminist’ in order to make very valid points about how a very specific kind of female pain, grief and trauma is often ignored and overlooked. Connie’s body violates the very specific white ableness championed by the Hårga, and her experience as Other legitimizes her death. Dani’s body, a white body that does not violate any of their traditions, is permitted to live. She is permitted to access the underbelly of the commune, but this comes at a price, and I believe that price is a combination of her sanity, her sense of self, and any remaining link she had to her past.

That’s what I think Florence Pugh was so unbelievably good at depicting. I was absolutely blown away by her ability to howl like that. That sort of primal, unabashed screaming. I think the two times she -really- cries set up a really interesting dichotomy between female pain and male reactions to female pain. The first time that Dani really howls is when her parents and sister have died. It is dark, she starts this sort of crying whilst alone over the phone, and then Christian is with her but he feels entirely distant from her. The room is dark, he is rubbing her back and she is draped over him, but he feels entirely emotionally removed from the situation - he is not participating in her grief, he doesn’t look that affected by it. His presence makes the scene feel just that little bit more jarring. Actually, does he even say anything to her? As far as I remember, no he does not. She tells him they’ve died, we see a shot of him walking through the snow to her apartment, and then they’re in the apartment. He says nothing. The only noise is Dani’s screams. He is entirely silent. Compare this to the second time she howls, when she’s surrounded by the female members of the Hårga. This scene is entirely different. It’s light, and she’s surrounded by women who are touching her, caressing her, but most importantly, screaming with her. They howl and cry and scream with her. They are her perfect mirrors. They are ACTIVELY PARTICIPATING in her grief, they share in her trauma. This was probably the most harrowing shot of the entire film for me. Not the gore, not the mutilated bodies – but a woman, screaming and howling like a wounded animal, and having a horde of sympathetic women scream back at her. It’s hard to not feel drawn into this community. It’s hard to not forget the evil things they have done, or are willing to do. That is precisely what is so dangerous about the Hårga, or more generally, this very specific brand of eco-fascism.

Some quick fire symbolism stuff that I picked up on:

the symbolism of Christian wearing dark clothing and standing away from the rest of the group when they were celebrating Dani becoming the May Queen. The way he lurches around, looking entirely out of place - she is sat at the head of the table - dressed as they are, crowned with flowers, nature moves with her - she has basically entirely assimilated - he is still outcast.

I thought it was really interesting that the group of women during the dub-con Christian/Maya sex scene mirrored how Maya was feeling. I think the focus on women mirroring each other, appropriating and absorbing how each other is feeling is a fascinating detail. Christian, on the other hand, looks out of place in that room, a male body who only has one purpose and then is entirely redundant. This is reinforced by the bit where the girl he is sleeping with holds her hand out and he tries to grab it but instead one of the women grabs it. He basically serves no purpose beyond impregnating her - and even then he isn’t even that good at it, because one of the other women has to push on his butt to push him along in the process. Women as being the most active and present in sex, men just … seed? Is this a subversion of how sex is usually seen?

The disabled boy seems to serve no purpose in society other than being the oracle - he does not participate in the banquet or any of the celebrations. He is almost never on screen, apart from a few very close up shots of his face, and one occasion where the camera shifts to him from the sex scene - a very jarring decision, in my opinion. Panning to him during the sex scene was super interesting and really not expected. It was an interesting visual choice, and it made me think about whether the point was to emphasise how he will presumably never participate in sexual acts etc. because of the eugenics practiced by the Hårga. This was a pretty damning condemnation of the Hårga as an eco-fascist group who actively engages in eugenics/”selective breeding”. You can definitely see links here between the growth of fascism and eugenics in the early 20th century and the practices of the Hårga.

I really liked how the entire time they were at the commune almost felt like … a fever dream in a distant fairytale land. Walking through the large sun at the beginning, having to trek through the fields to get there, everything looking very idyllic and exactly how a young child would imagine a Swedish landscape to look. The perfect environment to discuss dissociation, in my opinion.

These are some scattered thoughts I had after viewing the film!!

Overall, I really enjoyed it, despite some of the troubling social themes, and it’s another absolute win for Aster in my book.

#midsommar#midsommar spoilers#tee hee i posted it early#i have so many more thoughts but this is already nearly 2k words so i didn't want to post something obscenely long

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

HENRI MATISSE’S DOMESTIC INTERIORS

John Elderfield reexamines Matisse’s Piano Lesson (1916) and Music Lesson (1917), considering the works’ depictions of domestic space during the tumult of World War I.

Those interested in modern art who have been in voluntary isolation with a partner and children since the spring may have wondered: do we have images of what family life was like for the great early modernists? The answer is: at first, yes. As the nineteenth century advanced, it became increasingly common for married bourgeois couples in France to sleep together in double beds, and for much of their private time after marriage to be consumed with children. Greater intimacy between husband and wife, accompanied by closer family relationships generally, meant that paintings abounded of bourgeois parents with their children, including paintings of artists’ families.1

And so it remained through Impressionism. But the sterner modernism that followed was less forgiving of such potentially sentimental subjects, which remained the province of more traditional painters—artists who remained happy to record parents with the children they had begun to call by silly but touching pet names (as they often also did each other), and who posed proudly as families in their overstuffed living rooms. But Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso?

Actually, three of Matisse’s most important paintings are of his family: The Painter’s Family, The Piano Lesson, and The Music Lesson.2 What follows concentrates on the last two, especially the third. As will become apparent, their implications bear significantly on our present domestic situations, isolated from the viral chaos around us, and not only because both of them depict home schooling.

Two Lessons, Two Styles

These two works were painted in the years 1916–17, but in what order is extremely pertinent to their meanings. Before Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the Museum of Modern Art’s founding director, published his great 1951 monograph on Matisse—the first to establish a plausible chronology of the artist’s work—it was not known which canvas came first. As Barr reported, Pierre Matisse, the artist’s younger son, was “quite certain that the more abstract of the two, The Piano Lesson, is the earlier,” while the artist’s wife, Amélie, remembered that “the more abstract canvas was as usual painted after the more realistic one.”3

Had Madame Matisse been correct, the reputation of The Music Lesson would be akin to that of the first, freer versions of other pairs of the artist’s paintings: though not of the same order as the succeeding, more rigorous composition, it would be seen as an accomplished work. However, as Barr realized, it was Pierre Matisse who was correct. As a result, The Music Lesson has widely been seen as a regression on the artist’s part—a move away from the radical invention of his work of the 1910s, and one leading to the more traditional naturalism that would flourish in the 1920s.

So infuriated about this interpretation was the critic Dominique Fourcade that in 1986 he described its proponents as evidencing “satisfaction in letting the artist die in 1916 with La Leçon de piano . . . even if that meant letting him be reborn from nothingness” in the 1930s, to again work “abstractly and without transition, to the cut-outs at the end of his life.”4 I was not alone in thinking that “letting the artist die” was hyperbole on Fourcade’s part, but it proved no exaggeration: a decade or so later, in 1998, art historian Yve-Alain Bois was writing that with The Music Lesson Matisse “takes leave of himself, and of what I have called his system,” by which Bois meant the conception of painting that the artist had formed a decade earlier and employed through the creation of The Piano Lesson.5 Clearly, if Matisse “takes leave of himself, and . . . his system” in The Music Lesson, then, for Bois, he does at that moment die, at least artistically. To compare these two paintings, then, is unlike comparing any other pair of paintings by Matisse: it is to adjudicate a controversy.

Family Paintings

Let us begin with what the two paintings have in common: size, medium, and subject matter. Both are about eight feet tall by seven feet wide, with The Piano Lesson very slightly the larger of the pair. This makes them the largest paintings Matisse ever made, with the exception of his few imagined compositions: Dance and Music, of 1909–10, and Bathers by a River and The Moroccans, both completed more or less at the same time as The Piano Lesson. Like most of Matisse’s paintings, they were painted in oil on canvas.

To turn to subject matter is to open the pages of a very extensive literature, some of which I myself have written and which interested readers can easily find.6 But at least a summary is needed here, for these two paintings are exceptional both in their particular choice of subject and in their relationship to works on a similar subject. In the latter respect they belong to a long sequence of the artist’s paintings of a privileged interior space, either home or studio or both at the same time. As with some but not all earlier such paintings—the most celebrated example being The Red Studio (1911)—the objects depicted within their interiors have allusive or symbolic qualities, either conventional or original to Matisse. And, like most but not all of the paintings in this subcategory, the manner in which the interior and the objects within it are painted explicitly participates in the shaping of these qualities.

To further reduce the field of comparison, these are, as we have heard, family paintings, preceded in this respect by only The Painter’s Family of 1911.7 To be precise, The Piano Lesson shows only one member of the family—Pierre, the artist’s younger son—while The Music Lesson, just like The Painter’s Family, shows all of its members: Matisse’s eldest child, Marguerite, stands beside Pierre at the piano; his older brother, Jean, sits at the left, smoking while reading; the artist’s wife, Amélie, is outside in the garden; and though Matisse himself goes unseen, he is alluded to through a prominent depiction of his violin, which rests on the piano. It is truly a painting of a painter’s family; and Matisse himself titled it La famille. It was renamed The Music Lesson by Albert C. Barnes, never one to shy from taking such liberties, after it entered his collection (now the collection of the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia) in 1923.8

These paintings, and especially the second, belong to a long tradition of representations of one and usually more members of a family in an explicitly domestic space, and engaged in an activity or activities appropriate to it. The most prominent antecedents are the paintings of, and made for, the comfortable bourgeois households of seventeenth-century Holland. Eugène Fromentin, in his book Les maîtres d’autrefois of 1876, proposed that Dutch art, famous for its domestic interiors, effectively began in 1609, with the beginning of the twelve-year truce in the Eighty Years’ War with Spain.9 Art historian Svetlana Alpers, to whom I owe this observation, points out that wartime paintings of guardrooms and garrisons were the forerunners of these domestic interiors; familial intimacy would have been understood to be the counterpart of martial camaraderie.

By now, alarm bells should be sounding, at least for those who know that the years 1916 and 1917, when Matisse made these two paintings, were very bad years indeed for France in World War I, with more than half a million dead in 1916 and almost as many the following year. Moreover, these works were painted in the living room of Matisse’s home, looking out onto its back garden, where his studio stood.10 The house was in Issy-les-Moulineaux, a suburb of Paris that had transformed itself into a center for the military aviation industry, producing fighter planes; and the household was impoverished by the war, whose guns could actually be heard from the garden on quiet days—guns, and also massive explosions from military mines, both utterly destructive of the French countryside. The loudest of these—on June 7, 1917, during the Battle of Messines—was the product of 600 tons of explosives that blew off the crest along the entire length of the Messines Ridge; it was heard as far away as Dublin.11 The British general who ordered this offensive famously remarked, “We may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography.”12 This was not only a war between nations but also had quickly become a war against nature.

It was around this time that The Music Lesson was painted, in midsummer 1917. That was also when—as Matisse wrote in a letter to his friend the painter Charles Camoin—“Something important has happened in my house: Jean, my eldest, has left to join the regiment at Dijon.”13 What may at first sight appear to be a scene of cultured and contented domestic harmony, then, was about to shattered. This is not only a family painting; it is also a war painting.

Much has been written of the reductive, “abstract” vocabulary of The Piano Lesson as the result of Cubist geometry, on the one hand, and wartime avoidance of luxury, on the other. These factors may indeed have been sources for Matisse as he painted this picture, but a source may or may not be called into play in the finished form of a work of art.14 As I see it, the war as a source is actually called into play more fully in The Music Lesson than in its predecessor, if less obviously. Knowing that Jean Matisse was headed for guardrooms or garrisons aids a martial association that may have been in his father’s mind, but this is present in the painting only for those who know it as well. In what follows, I shall propose that the imaging of this sociable canvas itself invites interpretation as describing a family in a moment of lockdown against mindfulness of anything troublingly external, whereas The Piano Lesson pushes out of our minds all but the moment of twilight grace that it represents.

Rooms with a View

Let us now look at what the two paintings represent, and how they do so. As we have heard, The Piano Lesson shows solely the artist’s younger son, Pierre. He stares out toward us, even while lost in concentration, practicing on a very bourgeois Pleyel piano beside a French window open to the garden. Pierre was sixteen when the picture was painted but looks much younger. Since he and his father were the musicians of the family, he may be thought to function as a surrogate for the painter. In the bottom-left corner of the painting we see Matisse’s Decorative Figure of 1908, arguably the most sexual of his sculptures. Behind Pierre we may think we see a woman seated on a high stool, a severe, supervisory, arguably maternal presence, but this is actually a painting on the wall, Matisse’s Woman on a High Stool (Germaine Raynal) of 1914, transformed to convey these qualities.15 On the rose cloth over the piano, a candle and a metronome recapitulate the opposition of vitality and logic that the sculpture and the painting introduce. Together, they also stress the measuring of time, while the carving around the reversed name of the piano on the music stand flows across time and space, like music, through the grillwork of the window.

Time has stopped at a moment of fading, late-afternoon light in a dimly illuminated interior. An unseen light to the right traverses the scene, striking the boy’s forehead and shadowing a triangle on his far cheek; brightening the salmon-orange curtain and the pale blue-gray of the partly closed right panel of the window; and illuminating a big triangular patch of lawn outside, the only visible feature of the darkened garden. It is the view of the room that matters.

The colors, including that green triangle no more distant than anything else, complement one another in ways that activate the stillness of the scene. The orange converses with the pale blue, and the rose with the green; these are interrupted by a yellow and a black, all of them reconciled by the surrounding soft gray, which they appear to tint. The colors also resist being fully incorporated into the work of objective depiction, largely because they occupy such stark, autonomous shapes. Instead, the strips and shards of color may be imagined as organizing a simulacrum of the spatial experience of such a scene. They alternatively attract and repel each other, as if magnetized, tipping backward and forward in space, even as they shift in position across the plane of the picture. To follow their direction in the means and pace of our attention is to imagine a movement akin to walking through a room and registering the effects of parallax—the apparent displacement of objects in space due to changes in the position of the observer.

With The Music Lesson, by contrast, everything appears utterly still, and no one looks out of the room; we are excluded. However, we do now see the garden. More precisely, we are shown a view not into the garden but of it, for Matisse has given it the appearance of a painted screen rolled down at the back of the living room, the gray frame around it containing a scene no more real than that of the woman on a high stool in the ocher-framed painting beside it. As such, it may be thought to conceal the reality of what is outside. Prominent beyond the pool is a much enlarged reprise of Matisse’s sculpture Reclining Nude I (Aurora) as re-represented in his Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra (both 1907), the luxuriant backdrop here substituting for the North African setting of the earlier painting, and similarly enhancing the nude’s sensuality.16 The garden erased by twilight in The Piano Lesson may seem a better response to a war that was more ruthlessly and extensively destructive of landscape than any previous. But as the critic Paul Fussell observed of the literature produced during World War I, “If the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”17

Whereas, in making The Piano Lesson, Matisse condensed, eliminating detail, in The Music Lesson he veiled and washed over drawn detail with thinly applied paint. He had been working like this since making his late, dark-and-sculptural Fauve paintings, such as Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra; and he continued to do so in a less sculptural way, and with a lighter palette, even while making more severe, opaque pictures throughout his so-called “experimental period,” of which The Piano Lesson was a summative work. The manner in which The Music Lesson was painted is less a fall from modernist grace, as many critics have characterized it, than a recovery of that late Fauve manner, but with a more intense, indeed almost hallucinatory palette.

Leave-taking

Bois said Matisse took leave of a “system” after painting The Piano Lesson. He characterized that system as “an all-over conception of the canvas” that is “the product of a total democracy on the picture plane, of a dispersion of forces: our gaze is forbidden to focus on any particular area of the picture.”18 I agree that that painting’s successor is a leave-taking painting, but not in that sense: I think Bois’s description also applies to The Music Lesson, and that it is as summative in its own way as its predecessor. The two works encapsulate the momentum of preceding domestic and studio interiors in two different keys, the earlier work drawing together the achievements of the four preceding extraordinary years, the later looking back a decade to see what earlier innovations should be preserved. And it is the later work, with its extraordinarily disjointed composition—of which more in a moment—that shuttles around our gaze the more frenetically.

The putative sweetness and naturalism of The Music Lesson may lull us into believing that it is an undemanding work, but it is as undemanding as, say, Watteau’s paintings of disconnected figures, made two centuries earlier, from which it draws inspiration. Barr perceptively described its style as “descriptive rococo.”19 The artist and critic Amédée Ozenfant invoked another eighteenth-century artist when he observed of the Nice-period paintings that followed The Music Lesson, “This hankering for comfort. . . . When I hear him taking this line à la Fragonard, I have the feeling it is a feint.”20 I myself have the feeling that The Music Lesson is a feint, challenging our preconceptions, at the end of Matisse’s most extremist period of modernism, as to what a modern painting can be.

I therefore find myself disagreeing not only with Bois, who sees The Music Lesson as Matisse’s leave-taking from his time as a modernist painter, but also with Fourcade, who wants to see the artist’s career as “an uninterrupted story.”21 Painting his son Jean’s leave-taking, Matisse does paint a leave-taking of his own, a moving on from what he had achieved over the past few years. He was very clear about this, saying, “If I had continued down the . . . road which I knew so well, I would have ended up as a mannerist.”22 What he ends up as—predicated in The Music Lesson—is an artist determined not to be constrained by the universalizing modernism that he had inherited; hence his fascination with the prerevolutionary eighteenth century.23 This led him to develop from previously unexplored features of his post-Fauve paintings a highly self-conscious, even metapictorial, art of spectacle.

Whereas the modernism of The Piano Lesson is so tautly drawn that we never think of an actual pianist wedged behind the sheet music, the naturalism of The Music Lesson invites us to imagine the members of the family having taken their places where Matisse shows them. If we do imagine that, we must conclude that all of them are oblivious to what is around them, and to each other—except for the intimate couple at the piano, Marguerite protective of her younger brother, Pierre, since the elder one will soon be leaving. Both Jean and Amélie are alone. If we know of his approaching mobilization, we may guess why. Amélie’s isolation—outside the oasislike part of the garden, with its voluptuous sculpture—leaves little to the imagination. Still, whether paired or alone, the family sit in a cramped, busily claustrophobic space. And whether music-making or reading or whatever it is that Madame Matisse is doing—knitting, perhaps—they are not at work; their occupations are pastimes, ways of passing the time. Yet if the The Piano Lesson evokes time measured, The Music Lesson suggests time paused—whether forever or just momentarily is unclear, but Matisse has certainly hit the pause button, with his family at once busily occupied and locked down in place.

Speaking recently of Matisse’s contemporaneous Garden at Issy, art historian T. J. Clark refers to “those pictures—the key pictures, most often, in modernism—where deep inward concentration on means, fierce enclosure in a pictorial world, results in a strength that is not like any kind of pictorial strength we have seen before.”24 The Music Lesson both reflects fierce enclosure and is a picture of one; however, it is a thing of parts and patches less well guarded than The Piano Lesson.

The vivid coloration of The Music Lesson adds an apparitional, somewhat exotic quality to this family tableau, the pink answering the green, the turquoise the brown, and the gray binding the other colors while also separating out the soon-to-be soldier. Barnes compared its large geometric planes of flat color to those of what he called “Oriental art,” an association also applicable to the garden statue and linking The Music Lesson to The Painter’s Family, which was influenced by Persian miniatures.25 As in that earlier painting, the planes, piled one above the other, clash dissonantly, and our unified experience of the picture is to be found in our experience of its discord, not in its formal coherence as a decoratively patterned surface.26 Here, the superimposed flickering filaments of overlaid curvilinear drawing, which camouflage the meeting of the planes as they speak to the garden foliage, increase the sense of a composition poised on the brink of decomposition. As art historian Karen K. Butler acutely observes, “Overall, the strong tension between geometry and arabesque, or order and chaos, creates a mesmerizing subliminal stasis.”27 She adds that while The Music Lesson has been associated with nationalistic wartime critiques of avant-garde art in favor of traditional themes—here, “la bonne famille française”—its formal discord is complemented by its “thematic opposition of tropical and sexual luxuriance with bourgeois order.”28

This is not a regressive work, and there is nothing in it of a retour à l’ordre. Certainly the feint that it has seemed to introduce would become a way of disarming an audience hostile to modernism, but this did not prevent the result from being surreptitiously challenging, often melancholic, and affecting as well as sweetly beautiful. And the sweetness and beauty are obviously as much a challenge to modernist taste as their opposites are to antimodernist ones. In the end, though, what is at once most challenging to accommodate in our familiar picture of Matisse, and most familiar in the art that surrounds us now, is the assertion of the viability of aesthetic spectacle—the false scenic magic of what Charles Baudelaire called “favorite dreams treated with consummate skill and tragic concision.”29

A Man Who Is Not at the Front

This said, I must turn in conclusion to a question that readers may have been asking: even if The Piano Lesson and The Music Lesson are war paintings in the sense that they reflect their creation during wartime—the forces of order and chaos at odds in the family-lockdown canvas especially—they offer no response to the true horrors of the battlefields. In an earlier issue of the Quarterly (Spring 2020) I wrote of how, a half century earlier, the French painter Édouard Manet had faced the question of how to be an activist in his art by vigorously drawing attention to a single indefensible episode of violence, the shocking execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, who had been imposed on that country as its ruler through French neocolonialism. What, then, are we to make of Matisse’s silence on the unparalleled slaughter during the years of World War I?

The answer has two parts. The first is that Matisse volunteered for military duty, and even purchased boots in anticipation of serving, but was rejected owing to his age (he was forty-four) and weak heart. He was deeply upset—disappointed and I think ashamed—at not directly serving his country, especially since many of his friends and colleagues did serve, including his close friends Camoin and the painter Albert Marquet, as well as Guillaume Apollinaire and Georges Braque, both of whom were badly wounded and returned as war heroes. Others, however, were successful in escaping service, Robert Delaunay fleeing to Switzerland and Marcel Duchamp to the United States, and we must forget the honor claimed by many of those in the United States who refused the draft during the Vietnam War if we are to understand the dishonor assigned to those who did so in France in 1914. For Matisse, that would have been out of the question.

Second: Matisse spoke of sharing the sense of helplessness and revulsion that so many were feeling over the war, but he did help in practical ways.30 One of the first results of Germany’s invasion of France, for example, was the occupation of Matisse’s northern hometown of Bohain-en-Vermandois, which meant that the artist’s brother, Auguste, and some 400 other townsmen were deported to a German prison camp, leaving his seventy-year-old mother, Anna, alone and in failing health. Matisse sold prints in order to send 100 kilos of bread each week to these prisoners, who were at risk of dying from hunger.31 (Buying each week what works out to be 500 baguettes was no mean task during wartime.)

Yet Matisse clearly felt deeply uncomfortable about the idea of making art that professed to make a difference to what was happening on the battlefields. “Waste no sympathy on the idle conversation of a man who is not at the front,” he wrote to a gallerist, “and besides a man not at the front feels good for nothing.”32 It was impossible for Matisse to conceive of making war posters, as Raoul Dufy did; and paintings of battlefields, such as Félix Vallotton made, were obviously out of the question.33 Speaking for himself, he would write in 1951: “Despite pressure from certain conventional quarters, the war did not influence the subject of paintings, for we were no longer merely painting subjects. For those who could work there was only a restriction of means.”34

Matisse’s reaction to the privations of the war took the form of a self-imposed restriction of means, making do with less in his art as well as in his life. This response, which was ethical as well as pictorial, only increased the intensity of what he achieved. He spurned ostentation in both his personal and his public life, including refusing to draw attention to himself by staging solo exhibitions in Paris while his compatriots were in arms. And even as the Cubists, following Matisse’s own earlier lead, were enriching the color of their works in 1914, he refused ostentation in his art, too—then broke free with The Music Lesson to make his perhaps most underestimated major painting.

~

John Elderfield · Fall 2020 Issue.

John Elderfield, Chief Curator Emeritus of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum, joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

-

1 See Anne Martin-Fugier, “Bourgeois Rituals,” in Michelle Perrot, ed., A History of Private Life, vol. 4, From the Fires of Revolution to the Great War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1990), pp. 261–337, esp. “From Marriage to Family,” pp. 321–22.

2 A fourth, lesser painting, Pianist and Checker Players of 1924, is a reprise of The Painter’s Family. Luxe, calme et volupté of 1904–05 is, obliquely, a family painting, albeit not set in an interior. Illustrations of these and other works mentioned but not illustrated in this essay may be easily found in my Henri Matisse: A Retrospective (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1992). The present text is a substantially revised and expanded version of my essay “Un nouveau départ,” in Cécile Debray, Matisse: Paires et séries, exh. cat. (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2012), pp. 119–24.

3 Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Matisse: His Art and His Public (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1951), p. 193.

4 Dominique Fourcade, “An Uninterrupted Story,” in Henri Matisse: The Early Years in Nice, 1916–1930, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), pp. 47–48.

5 Yve-Alain Bois, Matisse and Picasso, exh. cat., Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (Paris: Flammarion, 1998), pp. 29–30.

6 See my essays on The Piano Lesson in Matisse in the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1978), pp. 114–16, and in Stephanie D’Alessandro and Elderfield, Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913–1917, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 290–93. The former speaks more of iconography, the latter more of the pictorial process, and both essays contain references to other literature on this painting and The Music Lesson.

7 See note 2 above on one later painting, Pianist and Checker Players.

8 The finest account of this painting is Karen K. Butler, “The Music Lesson,” in Yve-Alain Bois, ed., Matisse in the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2015), 2:214–29.

9 See Svetlana Alpers, The Vexations of Art: Velázquez and Others (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 86–90. As Alpers points out, pp. 83–84, Matisse’s Still Life after Jan Davidsz. De Heem’s “La Desserte” (1915) belongs to this discussion; on which see my discussion of this painting in Matisse: Radical Invention, pp. 254–59.

10 Garden at Issy, a painting made in June–October 1917, around the same time as The Painter’s Family, includes a schematic image of the studio.

11 See D’Alessandro, “The Challenge of Painting,” and my “Charting a New Course,” both in Matisse: Radical Invention, respectively pp. 262–69 and 310–19.

12 See Peter Barton, Peter Doyle, and Johan Vandewalle, Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers’ War 1914–1918 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), pp. 162–83. In Matisse: Radical Invention, p. 319, I relate this explosion to Matisse’s Shaft of Sunlight, also of summer 1917.

13 The family had been dreading this event, but Jean had volunteered and was therefore able to choose how he wished to serve. Probably on the basis of what he had seen in Issy, he opted to become an airplane mechanic, and soon left, to everyone’s relief, not for the front lines but to begin his mechanic’s training in Dijon. He was disgusted with the job within a fortnight, but at least he was not fighting in the mud of the trenches. See Matisse, letter to Charles Camoin, n.d. [summer 1917], in Claudine Grammont, ed., Correspondance entre Charles Camoin et Henri Matisse (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1997), p. 105.

14 See Christopher Ricks, Allusion to the Poets (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 3–4.

15 Woman on a High Stool is a portrait not of Mme. Matisse but of Germaine Raynal, the then-nineteen-year-old wife of the critic Maurice Raynal, who was closely allied with the Cubists. Here, though, she fulfills a role in the painting, and by extension in the Matisse household, akin to that of the chilly, dignified Mme. Bellelli in Edgar Degas’s Bellelli Family of c. 1860, a figure who, in Martin-Fugier’s description, “accurately portrays the role of the bourgeois mother.” “Bourgeois Rituals,” p. 269.

16 Matisse’s The Moroccans, another painting of a North African motif, conceived in 1912, was finally completed in November 1916, between the two family paintings and at a time of increasing concern for African soldiers involved in the war and visible on the streets of Paris.

17 Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975), 231. Fussell continues, “Since war takes place outdoors and always within nature, its symbolic status is that of the ultimate antipastoral.” Matisse’s final two (of six) sessions of work on his Bathers by a River (conceived 1909), which took place in 1916 and 1917, transformed what had begun as a pastoral composition into what is commonly understood to be an antipastoral one. The Piano Lesson and The Music Lesson were among the paintings he made when taking a break from making the critical changes on that enormous canvas. Its six-part development is charted in Matisse: Radical Invention, pp. 88–91, 104–07, 152–57, 174–77, 304–09, 346–49.

18 Bois, Matisse and Picasso, pp. 29–30.

19 Barr, Matisse: His Art and His Public, p. 194.

20 Amédée Ozenfant, Mémoires, 1886–1962 (Paris: Segher, 1968), p. 215; quoted here from Pierre Schneider, Matisse (New York: Rizzoli, 1984), p. 506. I have discussed this statement previously in Henri Matisse: A Retrospective, pp. 37–41.

21 Fourcade, “An Uninterrupted Story.”

22 Matisse, quoted in Ragnar Hoppe, “På visit hos Matisse,” in Städer och Konstnärer, resebrev och essäer om Konst (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1931), 196, recording a visit to Matisse in 1919. Trans. in Jack Flam, ed., Matisse on Art (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. 75.

23 Edward Said has relevant things to say here in “Return to the Eighteenth Century,” in his On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Pantheon, 2006), pp. 25–47.