#1930's Era -Cabaret

Text

Come taste the wine... : 70th anniversary of Julie Andrews's 'cabaret debut' at the Café Dansant, Cleethorpes,

3 performances

Easter, 14-17 April, 1954

This week, seventy years ago, Julie Andrews made her official 'cabaret debut' at the Café Dansant in Cleethorpes. While not a major milestone in the traditional sense -- and one that seldom features in standard Andrews biographies -- the Cleethorpes appearance was nevertheless a significant event in the star's early career.

For a start, it was Julie's first appearance in cabaret -- the theatrical genre that is, not the Broadway musical which is a whole other Julieverse story. Characterised by sophisticated nightclub settings with adult audiences watching intimate performances, cabaret emerged in fin-de-siècle Paris before expanding to other European cities such as Berlin and Amsterdam (Appignanesi, 2004). Imported to Britain in the interwar years, cabaret offered a more urbane, adult alternative to the domestic traditions of English music hall and variety with their family audiences and jolly communal spirit (Nott, 2002, p. 120ff).

Julie's debut in cabaret was, thus, a significant step in her professional evolution towards a more mature image and repertoire. By 1954, Julie was 18, and well beyond the child star tag of her earlier years. Under the guidance of manager, Charles Tucker, there was a calculated strategy to reshape her stardom towards adulthood.

The maturation of Julie's image had begun in earnest the previous summer with Cap and Belles (1953), a touring revue that Tucker produced as a showcase for Julie, comedian Max Wall, and several other acts under his management. Cap and Belles afforded Julie the opportunity to shine with two big solos and a number of dance sequences. Much was made in show publicity of Julie's new "grown up" look, including the fact that she was wearing "her first off-the-shoulder evening dress" ('Her First Grown-Up Dress', 1953, p. 4).

The Cleethorpes cabaret was a further step in this process of transformative 'adulting'. Indeed, it was something of a Cap and Belles redux. Not only was Max Wall back as headline co-star, Julie even wore the same 'grown up' strapless evening gown. In keeping with a cabaret format, though, Julie was provided a longer solo set where she sang a mix of classical and contemporary pop songs including "My Heart is Singing", "Belle of the Ball", "Always", and "Long Ago and Far Away" ('Cabaret opens', 1954, p. 4).

That Julie should have chosen Cleethorpes for her cabaret debut might seem odd to contemporary readers. Today, this small town on the north Lincolnshire coast is largely regarded as a somewhat faded, out-of-the-way seaside resort. In its heyday of the mid-twentieth century, however, Cleethorpes was a vibrant tourist hub that attracted tens of thousands of holidaymakers each year (Dowling, 2005). With several large theatres and entertainment venues, Cleethorpes was also an important stop in the summertime variety circuit, drawing many of the era’s big stars and entertainment acts (Morton, 1986).

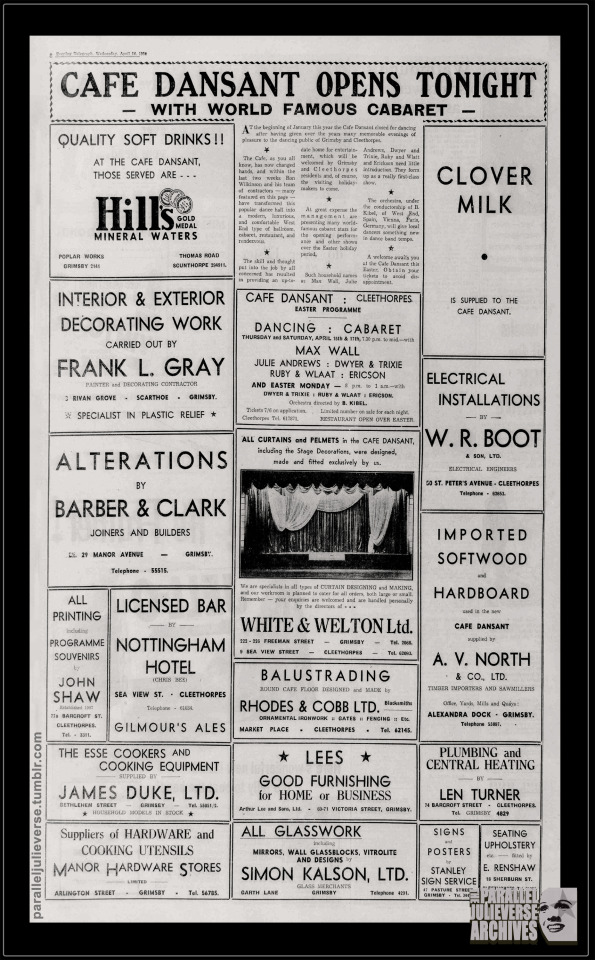

The Café Dansant was one of Cleethorpes' most iconic nighttime venues, celebrated for its elegant suppertime cabarets and salon orchestras. Opening in the 1930s, the Café was a particularly popular haunt during the war and post-war era when servicemen from nearby bases danced the night away with locals and visiting holidaymakers to the sound of touring jazz bands and crooners (Dowling, 2005, p. 129; Ruston, 2019).

By 1954, the Café was starting to show its age, and incoming new management decided to shutter the venue for several months to undertake a luxury refurbishment (‘Café Dansant closed', 1954, p. 3). A gala re-opening was set for the Easter weekend of April 1954, just in time for the start of the high season (‘Café Dansant opens', 1954, p. 8).

Opening festivities for the Café kicked off with a lavish five hour dinner cabaret on the evening of Wednesday, 14 April. Julie was “one of the world famous cabaret stars" booked for the gala event, and she received considerable promotional build-up in both local and national press (‘Café Dansant opens', 1954, p. 8).��There was even a widely circulating PR photo of Julie boarding the train to Cleethorpes at London's Kings Cross station.

In the end, Max Wall was unable to appear due to illness, and Alfred Marks -- another Tucker artist and former variety co-star of Julie's (Look In, 1952) -- stepped in at short notice. Rounding out the bill were several other minor acts, including American dance duo, Bobby Dwyer and Trixie; novelty entertainers, Ruby and Charles Wlaat; and magician Ericson who doubled as cabaret emcee.

Commentators judged the evening a resounding success. The "Cafe Dansant has got away to a flying start, after probably the biggest opening night ever seen in Cleethorpes," effused one newspaper report (Sandbox, 1954, p.4). Special mention was made of Julie who “received a great reception when she sang a selection of old and new songs, accompanied at the piano by her mother” (‘'Café Dansant reopening’, 1954, p. 6).

Following her performance, Julie joined the Mayor of Cleethorpes, Mr Albert Winters, in a cake-cutting ceremony and mayoral dance. Decades later, Winters recalled how he still “savour[ed] the memory of snatching a dance with the young girl destined to be a star… [S]he seemed very slim and frail,” he reminisced, “but she was a great dancer and I thoroughly enjoyed myself” (Morton, 1986, p. 15).

Julie stayed on in Cleethorpes for two more performances on Thursday 15 and Saturday 17 April respectively, before returning to London with her mother on Easter Sunday, 18 April. The very next day she commenced formal rehearsals for Mountain Fire, Julie's first dramatic 'straight' play and another step in her professional pivot to more adult content (--also, time permitting, the subject of a possible future blogpost).

A final noteworthy aspect about the Cleethorpes appearance is that it was during this weekend that Julie made the momentous decision to go to America to star in The Boy Friend. In what has become part of theatrical lore, Julie had been offered the plum role of Polly Browne in the show's Broadway production sometime in February or March of 1954 while she was appearing in Cinderella at the London Palladium. To the American producers’ astonishment --- and manager Tucker’s horror -- Julie was initially reluctant to accept, fearful of leaving her home and family. She prevaricated for weeks. Finally, while she was in Cleethorpes, Julie was given an ultimatum and told she had to make her decision.

In her 1958 serialised memoir for Woman magazine, Julie recounts:

“Mummie and I went to Cleethorpes to do a concert. It was a miserable wet day. From our hotel I watched the dark sea pounding the shore with great grey waves. I was called to the downstairs telephone.

“Julie,” said Uncle Charles [Tucker]‘s voice from London, “they can’t wait any longer. You’ll have to make your mind up NOW.”

I burst into tears.

“I’ll go Uncle,” I sobbed, “if you’ll make it only one year’s contract instead of two. Only one year, please.” …

Against everyone’s judgment and wishes I got my way…None of us knew that if I’d signed for two [years], then I should never have been free to do Eliza in My Fair Lady. And never known all the happiness and success it has brought me” (Andrews, 1958, p. 46).

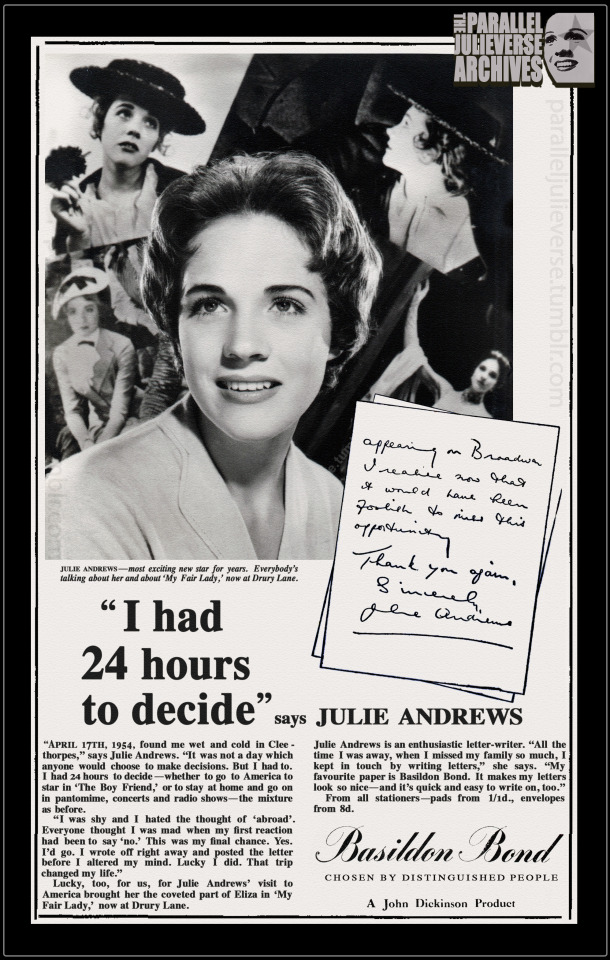

The Cleethorpes ultimatum even found its way into an advertising campaign that Julie did for Basildon Bond stationery in 1958/59, albeit with the telephone call converted into a letter for enhanced marketing purposes. Framed as a choice between going to America and the “trip [that] changed my life” or staying at home in England “and go[ing] on in pantomime, concerts, and radio shows—the mixture as before,” the advert highlighted the “sliding door” gravity of that fateful Cleethorpes weekend (Basildon Bond, 1958). What would the course of Julie's life been like had she said no to Broadway and opted to remain in the UK?

It is a speculative refrain that Julie and others have made frequently over the years. “If I’d stayed in England I would probably have got no further than pantomime leads,” she mused in a 1970 interview (Franks, 1970, p. 32). Or, more dramatically: “Had I remained in London and not appeared in the Broadway production of The Boy Friend…who knows, I might be starving in some chorus line today” (Hirschorn, 1968).

In all seriousness, it's doubtful that a British-based Julie would have faded into professional oblivion. As biographer John Cottrell quips: "that golden voice would always have kept her out of the chorus” (Cottrell, 1968, p. 71). Nevertheless, Julie's professional options in Britain during that era would have been greatly diminished. And she certainly wouldn't have achieved the level of international superstardom enabled by Broadway and Hollywood. Who knows, in a parallel 'sliding door' universe, our Julie might have gone on playing cabarets and end-of-pier shows in Cleethorpes...

Sources

Andrews, J. (1958). 'So much to sing about, part 3.' Woman. 17 May, 15-18, 45-48.

Appignanesi, L. (2004). The cabaret. Revised edn. Yale University Press.

Basildon Bond. (1958). 'I had 24 hours to decide, says Julie Andrews'. [Advertisement]. Daily Mirror. 6 October, p. 4.

'Cabaret opens Café Dansant." (1954). Grimsby Daily Telegraph. 15 April, p. 4.

‘Café Dansant closed.' (1954). Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 28 January, p. 3.

‘Café Dansant opens tonight – with world-famous cabaret’. (1954). Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 14 April, p. 8.

‘Café Dansant reopening a gay affair.’ (1954). Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 15 April, p. 6.

Cottrell, J. (1968). Julie Andrews: The story of a star. Arthur Barker Ltd.

Dowling, A. (2005). Cleethorpes: The creation of a seaside resort. Phillimore.

'Echoes of the past, the old Café Dansant'. (2009). Cleethorpes Chronicle. December 3, p. 13.

Frank, E. (1954). Daily News. 15 April, p.6.

Franks, G. (1970). ‘Whatever’s happened to Mary Poppins?’ Leicester Mercury. 4 December, p. 32.

'Her first grown-up dress.' (1953). Sussex Daily News. 28 July, p. 4.

Hirschorn, C. (1968). 'America made me, says Julie Andrews.' Sunday Express. 8 September, p. 23.

Morton, J. (1986). ‘Where the stars began to shine’. Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 22 September, p. 15.

Nott, J.J. (2002). Music for the people: Popular music and dance in interwar Britain. Oxford University Press.

Ruston, A. (2019). 'Taking a step back in time to the Cleethorpes gem Cafe Dansant where The Kinks once played'. Grimsby Live. 12 October.

Sandboy. (1954). 'Cleethorpes notebook: Flying start.' Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 19 April, p. 4.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

GREEN/Days

It's Ayumi Hamasaki's birthday on October 2 and we're extending the celebration in true ego-maniacal, splashy celebrity fashion, by drawing out the festivities for an entire week! Each day I will briefly discuss a totally random item chosen (not by me) from my Ayu collection. Prepare for praise, disappointment, and controversial opinions backed by love and respect as we take a casual look back in this blurry snapshot of her career in music. Happy Birthday to our Party Queen, Ayumi Hamasaki!

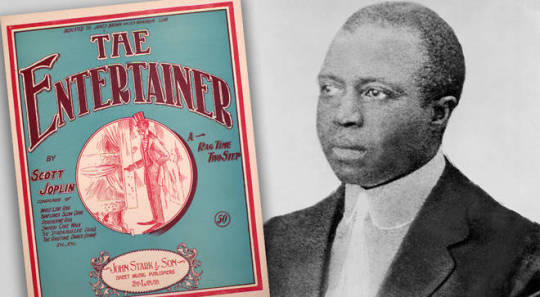

Here's an interesting question when it comes to Ayumi Hamasaki's "GREEN": what came first, the song or the concept? GREEN/Days (or Days/GREEN, depending on which version you bought) is Ayu's 44th single, released at the end of 2008 during her downfall in popularity. I think it was around this time that Ayu truly stopped taking into account what was expected of her and really just did what she wanted, for better and worse.

This single featured two new songs, "GREEN" and "Days," and re-recorded, 10th-anniversary versions of two singles, "TO BE" and "LOVE ~Destiny~." Which version you got, and in what order, depended on which of four different versions you bought. "GREEN" is an interesting song: it draws heavily upon classic Chinese instrumentation that weaves within it a very modern Ayumi Hamasaki rock song. It is propulsive and epic and has all the drama and intensity of Ayumi at this period in her music career. The music video reflects this heavily, with Ayumi playing a cabaret singer in 1930s-era China. The song and video were very strategic: just one year before, Ayumi started touring outside of Japan for the first time, making notable stops in Taiwain, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. And one month after this single was released, she performed her first featured show in Taipei. All of this accounts for the thematic influences in the music video and song.

The second song, "Days," is a typical winter-Ayu ballad. It reminds me of 2003's "No way to say" or even 2004's "CAROLS," including heavy use of slow-motion and CGI snow in the videos. Like the PV for "GREEN," Ayu's back-up dancer SHU-YA and his hair cut features prominently in the music video, here as an unrequited love interest. It's a solid song, but I wouldn't put it in the same category as some of her other iconic ballads.

Let’s talk about the re-recordings: In my opinion, if new vocals and arrangement don't somehow improve upon, or provide some kind of new insight into, the original, then there is no point in re-making a classic. That would be the case here for these, especially "TO BE," whose production, while busier, seems oddly thin. It is also a universal truth that Ayu's vocals, whether you like them or not, have definitely not improved since the original song was recorded. They might have more personality and emotion, but they don't sound technically better, and in many ways, they sound like somewhat-hurried live recordings. If you really want to hear "TO BE," it's better to hit up the original on LOVEppears.

The limited-edition packaging on this is identical to the only other single she released in 2008, Mirrorcle World, where both discs come housed in a long, vertical slip case almost 9 1/2 inches tall. There were three other versions released: a limited-edition and CD-only version entitled "Days/GREEN," which included the 10th Anniversary Version of "LOVE ~Destiny" and included the making-of feature for "Days," rather than "GREEN," on the DVD. There was also a regular CD-only version of "GREEN/Days" released with the same track listing as the limited edition.

This is a solid single release from Ayu, but it's not my favorite. "GREEN" is great, "Days" is good (but generic), and the 10th Anniversary Versions are unnecessary, if not a touch insulting. The limited-edition packaging is fun, but only if you can find a second-hand version for cheap. Ayu looks beautiful on the jacket art, but also somewhat sleepy, and none of it really reflects the tone of the content within. The real kicker is the album that these songs ended up on...

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baltimore New Year's Eve Spectacular Celebration

This Year's Special New Year's Eve Party Theme: ONE NIGHT IN PARIS: A Parisian Fantasy.

Come spend New Year's Eve in The City of Lights, Paris, and save the airfare! Share the romance and mystery of the world's most magical city, sample the food, the sounds, the ambiance of historic Paris, all tucked into the modern Hilton BWI. Dress in period costumes from many French historical eras, or today's finest evening wear. The people watching will nearly be as much fun as dressing up.Expect the finest food and drinks, spectacular entertainment, photo ops and special surprises. This will be the most dazzling time traveling adventure to begin your new year!Caring Communities Presents Charm City Countdown New Years Eve Baltimore Style.

We transport you to PARIS, France, to dine, dance, drink and dream in multiple party zones representing a variety of Parisian icons, districts and historical eras! Think American in Paris, Marie Antoinette, Midnight in Paris, Moulin Rouge and every other movie about Paris all rolled into one evening: One Night in Paris: A Parisian Fantasy!

What a great way to celebrate New Year's Eve in Baltimore!

We're reimagining each room into a different Paris icon, locale or historical venue. Sit at a quaint street cafe or sip wine on the Left Bank. Stroll the Champs-Elysees. Be entertained at a famous palace where kings sat upon thrones, or shake it up at a well known cabaret. All this, plus the tastiest food, modern drinks and classic favorites plus unique entertainment and great dance music. You are welcome to dress for the red carpet in elegant NYE cocktail attire or in your favorite French historical, traditional or regional garb.

Dress is of course central to our Paris theme. Paris has been the center of fashion design for over 100 years, and dozens of top designers work and sell fashion throughout the city. So top fashion is always in vogue. But Paris, called the City of Lights, has been a diverse metropolis for centuries. Traditional French peasant wear, striped shirts with berets, and parasol dresses would work well. Also period dress from the 1950's, 1930's, and 1900's is welcome. So are 18th century costumes, dance hall outfits and retro-historical Steampunk outfits. There are many options to dress for One Night in Paris.

BUY TICKETS NOW - Maryland NYE

0 notes

Text

Electronic Music History and Today's Best Modern Proponents!

Electronic music history pre-dates the rock and roll era by decades. Most of us were not even on this planet when it began its often obscure, under-appreciated and misunderstood development. Today, this 'other worldly' body of sound which began close to a century ago, may no longer appear strange and unique as new generations have accepted much of it as mainstream, but it's had a bumpy road and, in finding mass audience acceptance, a slow one.

Many musicians - the modern proponents of electronic music - developed a passion for analogue synthesizers in the late 1970's and early 1980's with signature songs like Gary Numan's breakthrough, 'Are Friends Electric?'. It was in this era that these devices became smaller, more accessible, more user friendly and more affordable for many of us. In this article I will attempt to trace this history in easily digestible chapters and offer examples of today's best modern proponents.

To my mind, this was the beginning of a new epoch. To create electronic music, it was no longer necessary to have access to a roomful of technology in a studio or live. Hitherto, this was solely the domain of artists the likes of Kraftwerk, whose arsenal of electronic instruments and custom built gadgetry the rest of us could only have dreamed of, even if we could understand the logistics of their functioning. Having said this, at the time I was growing up in the 60's & 70's, I nevertheless had little knowledge of the complexity of work that had set a standard in previous decades to arrive at this point.

The history of electronic music owes much to Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007). Stockhausen was a German Avante Garde composer and a pioneering figurehead in electronic music from the 1950's onwards, influencing a movement that would eventually have a powerful impact upon names such as Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Brain Eno, Cabaret Voltaire, Depeche Mode, not to mention the experimental work of the Beatles' and others in the 1960's. His face is seen on the cover of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band", the Beatles' 1967 master Opus. Let's start, however, by traveling a little further back in time.

The Turn of the 20th Century

Time stood still for this stargazer when I originally discovered that the first documented, exclusively electronic, concerts were not in the 1970's or 1980's but in the 1920's!

The first purely electronic instrument, the Theremin, which is played without touch, was invented by Russian scientist and cellist, Lev Termen (1896-1993), circa 1919.

In 1924, the Theremin made its concert debut with the Leningrad Philharmonic. Interest generated by the theremin drew audiences to concerts staged across Europe and Britain. In 1930, the prestigious Carnegie Hall in New York, experienced a performance of classical music using nothing but a series of ten theremins. Watching a number of skilled musicians playing this eerie sounding instrument by waving their hands around its antennae must have been so exhilarating, surreal and alien for a pre-tech audience!

For those interested, check out the recordings of Theremin virtuoso Clara Rockmore (1911-1998). Lithuanian born Rockmore (Reisenberg) worked with its inventor in New York to perfect the instrument during its early years and became its most acclaimed, brilliant and recognized performer and representative throughout her life.

In retrospect Clara, was the first celebrated 'star' of genuine electronic music. You are unlikely to find more eerie, yet beautiful performances of classical music on the Theremin. She's definitely a favorite of mine!

Electronic Music in Sci-Fi, Cinema and Television

Unfortunately, and due mainly to difficulty in skill mastering, the Theremin's future as a musical instrument was short lived. Eventually, it found a niche in 1950's Sci-Fi films. The 1951 cinema classic "The Day the Earth Stood Still", with a soundtrack by influential American film music composer Bernard Hermann (known for Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho", etc.), is rich with an 'extraterrestrial' score using two Theremins and other electronic devices melded with acoustic instrumentation.

Using the vacuum-tube oscillator technology of the Theremin, French cellist and radio telegraphist, Maurice Martenot (1898-1980), began developing the Ondes Martenot (in French, known as the Martenot Wave) in 1928.

Employing a standard and familiar keyboard which could be more easily mastered by a musician, Martenot's instrument succeeded where the Theremin failed in being user-friendly. In fact, it became the first successful electronic instrument to be used by composers and orchestras of its period until the present day.

It is featured on the theme to the original 1960's TV series "Star Trek", and can be heard on contemporary recordings by the likes of Radiohead and Brian Ferry.

The expressive multi-timbral Ondes Martenot, although monophonic, is the closest instrument of its generation I have heard which approaches the sound of modern synthesis.

"Forbidden Planet", released in 1956, was the first major commercial studio film to feature an exclusively electronic soundtrack… aside from introducing Robbie the Robot and the stunning Anne Francis! The ground-breaking score was produced by husband and wife team Louis and Bebe Barron who, in the late 1940's, established the first privately owned recording studio in the USA recording electronic experimental artists such as the iconic John Cage (whose own Avante Garde work challenged the definition of music itself!).

The Barrons are generally credited for having widening the application of electronic music in cinema. A soldering iron in one hand, Louis built circuitry which he manipulated to create a plethora of bizarre, 'unearthly' effects and motifs for the movie. Once performed, these sounds could not be replicated as the circuit would purposely overload, smoke and burn out to produce the desired sound result.

Consequently, they were all recorded to tape and Bebe sifted through hours of reels edited what was deemed usable, then re-manipulated these with delay and reverberation and creatively dubbed the end product using multiple tape decks.

In addition to this laborious work method, I feel compelled to include that which is, arguably, the most enduring and influential electronic Television signature ever: the theme to the long running 1963 British Sci-Fi adventure series, "Dr. Who". It was the first time a Television series featured a solely electronic theme. The theme to "Dr. Who" was created at the legendary BBC Radiophonic Workshop using tape loops and test oscillators to run through effects, record these to tape, then were re-manipulated and edited by another Electro pioneer, Delia Derbyshire, interpreting the composition of Ron Grainer.

As you can see, electronic music's prevalent usage in vintage Sci-Fi was the principle source of the general public's perception of this music as being 'other worldly' and 'alien-bizarre sounding'. This remained the case till at least 1968 with the release of the hit album "Switched-On Bach" performed entirely on a Moog modular synthesizer by Walter Carlos (who, with a few surgical nips and tucks, subsequently became Wendy Carlos).

The 1970's expanded electronic music's profile with the break through of bands like Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, and especially the 1980's when it found more mainstream acceptance.

The Mid 1900's: Musique Concrete

In its development through the 1900's, electronic music was not solely confined to electronic circuitry being manipulated to produce sound. Back in the 1940's, a relatively new German invention - the reel-to-reel tape recorder developed in the 1930's - became the subject of interest to a number of Avante Garde European composers, most notably the French radio broadcaster and composer Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) who developed a montage technique he called Musique Concrete.

Musique Concrete (meaning 'real world' existing sounds as opposed to artificial or acoustic ones produced by musical instruments) broadly involved the splicing together of recorded segments of tape containing 'found' sounds - natural, environmental, industrial and human - and manipulating these with effects such as delay, reverb, distortion, speeding up or slowing down of tape-speed (varispeed), reversing, etc.

Stockhausen actually held concerts utilizing his Musique Concrete works as backing tapes (by this stage electronic as well as 'real world' sounds were used on the recordings) on top of which live instruments would be performed by classical players responding to the mood and motifs they were hearing!

Musique Concrete had a wide impact not only on Avante Garde and effects libraries, but also on the contemporary music of the 1960's and 1970's. Important works to check are the Beatles' use of this method in ground-breaking tracks like 'Tomorrow Never Knows', 'Revolution No. 9' and 'Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite', as well as Pink Floyd albums "Umma Gumma", "Dark Side of the Moon" and Frank Zappa's "Lumpy Gravy". All used tape cut-ups and home-made tape loops often fed live into the main mixdown.

Today this can be performed with simplicity using digital sampling, but yesterday's heroes labored hours, days and even weeks to perhaps complete a four minute piece! For those of us who are contemporary musicians, understanding the history of electronic music helps in appreciating the quantum leap technology has taken in the recent period. But these early innovators, these pioneers - of which there are many more down the line - and the important figures they influenced that came before us, created the revolutionary groundwork that has become our electronic musical heritage today and for this I pay them homage!

1950's: The First Computer and Synth Play Music

Moving forward a few years to 1957 and enter the first computer into the electronic mix. As you can imagine, it wasn't exactly a portable laptop device but consumed a whole room and user friendly wasn't even a concept. Nonetheless creative people kept pushing the boundaries. One of these was Max Mathews (1926 -) from Bell Telephone Laboratories, New Jersey, who developed Music 1, the original music program for computers upon which all subsequent digital synthesis has its roots based. Mathews, dubbed the 'Father of Computer Music', using a digital IBM Mainframe, was the first to synthesize music on a computer.

In the climax of Stanley Kubrik's 1968 movie '2001: A Space Odyssey', use is made of a 1961 Mathews' electronic rendition of the late 1800's song 'Daisy Bell'. Here the musical accompaniment is performed by his programmed mainframe together with a computer-synthesized human 'singing' voice technique pioneered in the early 60's. In the movie, as HAL the computer regresses, 'he' reverts to this song, an homage to 'his' own origins.

1957 also witnessed the first advanced synth, the RCA Mk II Sound Synthesizer (an improvement on the 1955 original). It also featured an electronic sequencer to program music performance playback. This massive RCA Synth was installed, and still remains, at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, New York, where the legendary Robert Moog worked for a while. Universities and Tech laboratories were the main home for synth and computer music experimentation in that early era.

1960's: The Dawning of The Age of Moog

The logistics and complexity of composing and even having access to what were, until then, musician unfriendly synthesizers, led to a demand for more portable playable instruments. One of the first to respond, and definitely the most successful, was Robert Moog (1934-2005). His playable synth employed the familiar piano style keyboard.

Moog's bulky telephone-operators' cable plug-in type of modular synth was not one to be transported and set up with any amount of ease or speed! But it received an enormous boost in popularity with the success of Walter Carlos, as previously mentioned, in 1968. His LP (Long Player) best seller record "Switched-On Bach" was unprecedented because it was the first time an album appeared of fully synthesized music, as opposed to experimental sound pieces.

The album was a complex classical music performance with various multi-tracks and overdubs necessary, as the synthesizer was only monophonic! Carlos also created the electronic score for "A Clockwork Orange", Stanley Kubrik's disturbing 1972 futuristic film.

From this point, the Moog synth is prevalent on a number of late 1960's contemporary albums. In 1967 the Monkees' "Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd" became the first commercial pop album release to feature the modular Moog. In fact, singer/drummer Mickey Dolenz purchased one of the very first units sold.

It wasn't until the early 1970's, however, when the first Minimoog appeared that interest seriously developed amongst musicians. This portable little unit with a fat sound had a significant impact becoming part of live music kit for many touring musicians for years to come. Other companies such as Sequential Circuits, Roland and Korg began producing their own synths, giving birth to a music subculture.

I cannot close the chapter on the 1960's, however, without reference to the Mellotron. This electronic-mechanical instrument is often viewed as the primitive precursor to the modern digital sampler.

Developed in early 1960's Britain and based on the Chamberlin (a cumbersome US-designed instrument from the previous decade), the Mellotron keyboard triggered pre-recorded tapes, each key corresponding to the equivalent note and pitch of the pre-loaded acoustic instrument.

The Mellotron is legendary for its use on the Beatles' 1966 song 'Strawberry Fields Forever'. A flute tape-bank is used on the haunting introduction played by Paul McCartney.

The instrument's popularity burgeoned and was used on many recordings of the era such as the immensely successful Moody Blues epic 'Nights in White Satin'. The 1970's saw it adopted more and more by progressive rock bands. Electronic pioneers Tangerine Dream featured it on their early albums.

With time and further advances in microchip technology though, this charming instrument became a relic of its period.

1970's: The Birth of Vintage Electronic Bands

The early fluid albums of Tangerine Dream such as "Phaedra" from 1974 and Brian Eno's work with his self-coined 'ambient music' and on David Bowie's "Heroes" album, further drew interest in the synthesizer from both musicians and audience.

Kraftwerk, whose 1974 seminal album "Autobahn" achieved international commercial success, took the medium even further adding precision, pulsating electronic beats and rhythms and sublime synth melodies. Their minimalism suggested a cold, industrial and computerized-urban world. They often utilized vocoders and speech synthesis devices such as the gorgeously robotic 'Speak and Spell' voice emulator, the latter being a children's learning aid!

While inspired by the experimental electronic works of Stockhausen, as artists, Kraftwerk were the first to successfully combine all the elements of electronically generated music and noise and produce an easily recognizable song format. The addition of vocals in many of their songs, both in their native German tongue and English, helped earn them universal acclaim becoming one of the most influential contemporary music pioneers and performers of the past half-century.

Kraftwerk's 1978 gem 'Das Modell' hit the UK number one spot with a reissued English language version, 'The Model', in February 1982, making it one of the earliest Electro chart toppers!

Ironically, though, it took a movement that had no association with EM (Electronic Music) to facilitate its broader mainstream acceptance. The mid 1970's punk movement, primarily in Britain, brought with it a unique new attitude: one that gave priority to self-expression rather than performance dexterity and formal training, as embodied by contemporary progressive rock musicians. The initial aggression of metallic punk transformed into a less abrasive form during the late 1970's: New Wave. This, mixed with the comparative affordability of many small, easy to use synthesizers, led to the commercial synth explosion of the early 1980's.

A new generation of young people began to explore the potential of these instruments and began to create soundscapes challenging the prevailing perspective of contemporary music. This didn't arrive without battle scars though. The music industry establishment, especially in its media, often derided this new form of expression and presentation and was anxious to consign it to the dustbin of history.

1980's: The First Golden Era of Electronic Music for the Masses

Gary Numan became arguably the first commercial synth megastar with the 1979 "Tubeway Army" hit 'Are Friends Electric?'. The Sci-Fi element is not too far away once again. Some of the imagery is drawn from the Science Fiction classic, "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?". The 1982 hit film "Blade Runner" was also based on the same book.

Although 'Are Friends Electric?' featured conventional drum and bass backing, its dominant use of Polymoogs gives the song its very distinctive sound. The recording was the first synth-based release to achieve number one chart status in the UK during the post-punk years and helped usher in a new genre. No longer was electronic and/or synthesizer music consigned to the mainstream sidelines. Exciting!

Further developments in affordable electronic technology placed electronic squarely in the hands of young creators and began to transform professional studios.

Designed in Australia in 1978, the Fairlight Sampler CMI became the first commercially available polyphonic digital sampling instrument but its prohibitive cost saw it solely in use by the likes of Trevor Horn, Stevie Wonder and Peter Gabriel. By mid-decade, however, smaller, cheaper instruments entered the market such as the ubiquitous Akai and Emulator Samplers often used by musicians live to replicate their studio-recorded sounds. The Sampler revolutionized the production of music from this point on.

In most major markets, with the qualified exception of the US, the early 1980's was commercially drawn to electro-influenced artists. This was an exciting era for many of us, myself included. I know I wasn't alone in closeting the distorted guitar and amps and immersing myself into a new universe of musical expression - a sound world of the abstract and non traditional.

At home, Australian synth based bands Real Life ('Send Me An Angel', "Heartland" album), Icehouse ('Hey Little Girl') and Pseudo Echo ('Funky Town') began to chart internationally, and more experimental electronic outfits like Severed Heads and SPK also developed cult followings overseas.

But by mid-decade the first global electronic wave lost its momentum amidst resistance fomented by an unrelenting old school music media. Most of the artists that began the decade as predominantly electro-based either disintegrated or heavily hybrid their sound with traditional rock instrumentation.

The USA, the largest world market in every sense, remained in the conservative music wings for much of the 1980's. Although synth-based records did hit the American charts, the first being Human League's 1982 US chart topper 'Don't You Want Me Baby?', on the whole it was to be a few more years before the American mainstream embraced electronic music, at which point it consolidated itself as a dominant genre for musicians and audiences alike, worldwide.

1988 was somewhat of a watershed year for electronic music in the US. Often maligned in the press in their early years, it was Depeche Mode that unintentionally - and mostly unaware - spearheaded this new assault. From cult status in America for much of the decade, their new high-play rotation on what was now termed Modern Rock radio resulted in mega stadium performances. An Electro act playing sold out arenas was not common fare in the USA at that time!

In 1990, fan pandemonium in New York to greet the members at a central record shop made TV news, and their "Violator" album outselling Madonna and Prince in the same year made them a US household name. Electronic music was here to stay, without a doubt!

1990's Onward: The Second Golden Era of Electronic Music for the Masses

Before our 'star music' secured its hold on the US mainstream, and while it was losing commercial ground elsewhere throughout much of the mid 1980's, Detroit and Chicago became unassuming laboratories for an explosion of Electronic Music which would see out much of the 1990's and onwards. Enter Techno and House.

Detroit in the 1980's, a post-Fordism US industrial wasteland, produced the harder European influenced Techno. In the early to mid 80's, Detroiter Juan Atkins, an obsessive Kraftwerk fan, together with Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson - using primitive, often borrowed equipment - formed the backbone of what would become, together with House, the predominant music club-culture throughout the world. Heavily referenced artists that informed early Techno development were European pioneers such as the aforementioned Kraftwerk, as well as Yello and British Electro acts the likes of Depeche Mode, Human League, Heaven 17, New Order and Cabaret Voltaire.

Chicago, a four-hour drive away, simultaneously saw the development of House. The name is generally considered to be derived from "The Warehouse" where various DJ-Producers featured this new music amalgam. House has its roots in 1970's disco and, unlike Techno, usually has some form of vocal. I think Giorgio Moroder's work in the mid 70's with Donna Summer, especially the song 'I Feel Love', is pivotal in appreciating the 70's disco influences upon burgeoning Chicago House.

A myriad of variants and sub genres have developed since - crossing the Atlantic, reworked and back again - but in many ways the popular success of these two core forms revitalized the entire Electronic landscape and its associated social culture. Techno and House helped to profoundly challenge mainstream and Alternative Rock as the preferred listening choice for a new generation: a generation who has grown up with electronic music and accepts it as a given. For them, it is music that has always been.

The history of electronic music continues to be written as technology advances and people's expectations of where music can go continues to push it forward, increasing its vocabulary and lexicon.

Related Site study music

0 notes

Photo

What would you say to a Raymond Chandler-style murder mystery set in 1920s Germany that stars Volker Bruch (a subtle genetic blend of a Young Dennis Hopper and Montgomery Clift) as a PTSD-addled cop, and cute little Lisa Fries as a Weimar-era Nancy Drew? And done on a budget that would embarrass all of Hollywood combined, and crafted with attention to absurd, gorgeous detail that makes Wes Anderson seem carefree.

Hold that notion for a moment.

Babylon Berlin’s noir-infused narrative crawls alongside Germany’s rise to power, which we’ve seen in various productions dozens of times. But rather than stern drama, it’s instead a massive-scale fantasia (the most expensive television production in history) that employs the tropes and features of musicals, surrealism, police procedural, occult mystery, and cliffhanger serials.

Whole episodes seem at times solely devoted to offering brief devotions on the topics of architecture, psychoanalysis, fanaticism, Jugendstil Art Deco, surrealism, or cinema itself. But it’s all done as a delirious (if grim) visual tour, as opposed to a lecture.

I’m not doing the series justice here. Bear in mind that this is a Tom Tykwer project, and it revisits the imaginative, perverse energy of his Run Lola Run and Winter Sleepers work. It gets weirder and broader than all that, by far.

The aesthetic and vibe bring to mind Werner Herzog re-doing the entire “Avengers” British television series of the 1960s as a tribute to Fritz Lang and Neitzsche, or Paul Thomas Anderson reimagining Cabaret as one big episode of “Law & Order.”

It should be seen on a huge HD screen. Just wait until you get a load of the Hermann Platz and Rosenthaler Platz U-Bahn stations, or the Rotes Rathaus city hall on Alexanderplatz. It’s almost like the very sets and structures are characters in this bizarre, heartbreaking story.

Thanks to this series, I’ve had Roxy Music’s “Dance Away” in my head for the past few weeks. No, not the version we all grew up with. I mean the jazz age, klezmer-esque, Kurt Weill-ish version that—with a kind of reverse hauntology—woozily snakes its way through this mesmerizing, almost indescribable tale.

That song is about escaping the heartache of betrayal by getting lost in a pleasant diversion, to the point of obsession. That’s how romance and dating turn out sometimes. Babylon Berlin is about escaping betrayal and heartache because, well, that’s how history and culture turn out sometimes.

In 1920s Berlin, the dancing, along with numerous other diversions that are as perverse, frenetic, dark, and addictive as they want to be, take place in clubs and bars and brothels. Other folks are dancing in the streets, so to speak, in brutal clashes between numerous, barely distinguishable factions of Communists, Social Democrats, and the Berliner Polizist cops. There’s also a group of Trotskyites who can’t catch a break, and countless dual loyalties among Right and Left wings complicating the internecine fights that plague each political group. (Yes, the series does call for a Weimar politics flow chart at times.)

Most intriguing is that there’s hardly a Nazi to be found in the mix, unless you count the occasional dust-up with a few dozen Sturmabteilung bullies (those clumsy lads in sad, military-surplus brown shirts and little red arm bands).

There does seem to be a larger, more organized group waiting in the wings. Bunch of resentful holdovers from the First World War. Old, humorless guys in quite striking forest-green felduniform. Sure, it’s an army, but everyone in Germany in 1928 knows there aren’t going to be any more wars; that’s verrückt talk.

Speaking of crazy, the series has the main character’s mental illness, in the form of post-traumatic stress, function as a metaphor for the Weimar zeitgeist. It might seem like a facile reduction, especially if it were done in service to the notion that the cure is worse than the illness. But something else happens.

The close study of multiple characters in this series suggests that history may not always be guided by x-number of people getting swept up by something larger than themselves. Or by a mad leader.

Yes, a lot of folks march, shout, and fight in unison. But in this realm, major social changes are catalyzed by discrete (and often discreet), traumatic, life-altering personal histories that, solely by accident of geographical proximity, coalesce into what we would call a movement or a cause.

The world did witness the worst possible manifestations of “the madness of crowds” with what followed in Germany during the 1930s. But a deeper examination of what’s known as “the human experience” might reveal that each German was crazy alone before all of them were crazy together.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Electronic Music History and Today's Best Modern Proponents!

lectronic music history pre-dates the rock and roll era by decades. Most of us were not even on this planet when it began its often obscure, under-appreciated and misunderstood development. Today, this 'other worldly' body of sound which began close to a century ago, may no longer appear strange and unique as new generations have accepted much of it as mainstream, but it's had a bumpy road and, in finding mass audience acceptance, a slow one.

Many musicians - the modern proponents of electronic music - developed a passion for analogue synthesizers in the late 1970's and early 1980's with signature songs like Gary Numan's breakthrough, 'Are Friends Electric?'. It was in this era that these devices became smaller, more accessible, more user friendly and more affordable for many of us. In this article I will attempt to trace this history in easily digestible chapters and offer examples of today's best modern proponents.

To my mind, this was the beginning of a new epoch. To create electronic music, it was no longer necessary to have access to a roomful of technology in a studio or live. Hitherto, this was solely the domain of artists the likes of Kraftwerk, whose arsenal of electronic instruments and custom built gadgetry the rest of us could only have dreamed of, even if we could understand the logistics of their functioning. Having said this, at the time I was growing up in the 60's & 70's, I nevertheless had little knowledge of the complexity of work that had set a standard in previous decades to arrive at this point.

The history of electronic music owes much to Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007). Stockhausen was a German Avante Garde composer and a pioneering figurehead in electronic music from the 1950's onwards, influencing a movement that would eventually have a powerful impact upon names such as Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Brain Eno, Cabaret Voltaire, Depeche Mode, not to mention the experimental work of the Beatles' and others in the 1960's. His face is seen on the cover of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band", the Beatles' 1967 master Opus. Let's start, however, by traveling a little further back in time.

The Turn of the 20th Century

Time stood still for this stargazer when I originally discovered that the first documented, exclusively electronic, concerts were not in the 1970's or 1980's but in the 1920's!

The first purely electronic instrument, the Theremin, which is played without touch, was invented by Russian scientist and cellist, Lev Termen (1896-1993), circa 1919.

In 1924, the Theremin made its concert debut with the Leningrad Philharmonic. Interest generated by the theremin drew audiences to concerts staged across Europe and Britain. In 1930, the prestigious Carnegie Hall in New York, experienced a performance of classical music using nothing but a series of ten theremins. Watching a number of skilled musicians playing this eerie sounding instrument by waving their hands around its antennae must have been so exhilarating, surreal and alien for a pre-tech audience!

For those interested, check out the recordings of Theremin virtuoso Clara Rockmore (1911-1998). Lithuanian born Rockmore (Reisenberg) worked with its inventor in New York to perfect the instrument during its early years and became its most acclaimed, brilliant and recognized performer and representative throughout her life.

In retrospect Clara, was the first celebrated 'star' of genuine electronic music. You are unlikely to find more eerie, yet beautiful performances of classical music on the Theremin. She's definitely a favorite of mine!

Electronic Music in Sci-Fi, Cinema and Television

Unfortunately, and due mainly to difficulty in skill mastering, the Theremin's future as a musical instrument was short lived. Eventually, it found a niche in 1950's Sci-Fi films. The 1951 cinema classic "The Day the Earth Stood Still", with a soundtrack by influential American film music composer Bernard Hermann (known for Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho", etc.), is rich with an 'extraterrestrial' score using two Theremins and other electronic devices melded with acoustic instrumentation.

Using the vacuum-tube oscillator technology of the Theremin, French cellist and radio telegraphist, Maurice Martenot (1898-1980), began developing the Ondes Martenot (in French, known as the Martenot Wave) in 1928.

Employing a standard and familiar keyboard which could be more easily mastered by a musician, Martenot's instrument succeeded where the Theremin failed in being user-friendly. In fact, it became the first successful electronic instrument to be used by composers and orchestras of its period until the present day. http://www.chrisbitten.com/

It is featured on the theme to the original 1960's TV series "Star Trek", and can be heard on contemporary recordings by the likes of Radiohead and Brian Ferry.

The expressive multi-timbral Ondes Martenot, although monophonic, is the closest instrument of its generation I have heard which approaches the sound of modern synthesis.

"Forbidden Planet", released in 1956, was the first major commercial studio film to feature an exclusively electronic soundtrack... aside from introducing Robbie the Robot and the stunning Anne Francis! The ground-breaking score was produced by husband and wife team Louis and Bebe Barron who, in the late 1940's, established the first privately owned recording studio in the USA recording electronic experimental artists such as the iconic John Cage (whose own Avante Garde work challenged the definition of music itself!).

The Barrons are generally credited for having widening the application of electronic music in cinema. A soldering iron in one hand, Louis built circuitry which he manipulated to create a plethora of bizarre, 'unearthly' effects and motifs for the movie. Once performed, these sounds could not be replicated as the circuit would purposely overload, smoke and burn out to produce the desired sound result.

Consequently, they were all recorded to tape and Bebe sifted through hours of reels edited what was deemed usable, then re-manipulated these with delay and reverberation and creatively dubbed the end product using multiple tape decks.

In addition to this laborious work method, I feel compelled to include that which is, arguably, the most enduring and influential electronic Television signature ever: the theme to the long running 1963 British Sci-Fi adventure series, "Dr. Who". It was the first time a Television series featured a solely electronic theme. The theme to "Dr. Who" was created at the legendary BBC Radiophonic Workshop using tape loops and test oscillators to run through effects, record these to tape, then were re-manipulated and edited by another Electro pioneer, Delia Derbyshire, interpreting the composition of Ron Grainer.

As you can see, electronic music's prevalent usage in vintage Sci-Fi was the principle source of the general public's perception of this music as being 'other worldly' and 'alien-bizarre sounding'. This remained the case till at least 1968 with the release of the hit album "Switched-On Bach" performed entirely on a Moog modular synthesizer by Walter Carlos (who, with a few surgical nips and tucks, subsequently became Wendy Carlos).

The 1970's expanded electronic music's profile with the break through of bands like Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, and especially the 1980's when it found more mainstream acceptance.

The Mid 1900's: Musique Concrete

In its development through the 1900's, electronic music was not solely confined to electronic circuitry being manipulated to produce sound. Back in the 1940's, a relatively new German invention - the reel-to-reel tape recorder developed in the 1930's - became the subject of interest to a number of Avante Garde European composers, most notably the French radio broadcaster and composer Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) who developed a montage technique he called Musique Concrete.

Musique Concrete (meaning 'real world' existing sounds as opposed to artificial or acoustic ones produced by musical instruments) broadly involved the splicing together of recorded segments of tape containing 'found' sounds - natural, environmental, industrial and human - and manipulating these with effects such as delay, reverb, distortion, speeding up or slowing down of tape-speed (varispeed), reversing, etc.

Stockhausen actually held concerts utilizing his Musique Concrete works as backing tapes (by this stage electronic as well as 'real world' sounds were used on the recordings) on top of which live instruments would be performed by classical players responding to the mood and motifs they were hearing!

Musique Concrete had a wide impact not only on Avante Garde and effects libraries, but also on the contemporary music of the 1960's and 1970's. Important works to check are the Beatles' use of this method in ground-breaking tracks like 'Tomorrow Never Knows', 'Revolution No. 9' and 'Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite', as well as Pink Floyd albums "Umma Gumma", "Dark Side of the Moon" and Frank Zappa's "Lumpy Gravy". All used tape cut-ups and home-made tape loops often fed live into the main mixdown.

Today this can be performed with simplicity using digital sampling, but yesterday's heroes labored hours, days and even weeks to perhaps complete a four minute piece! For those of us who are contemporary musicians, understanding the history of electronic music helps in appreciating the quantum leap technology has taken in the recent period. But these early innovators, these pioneers - of which there are many more down the line - and the important figures they influenced that came before us, created the revolutionary groundwork that has become our electronic musical heritage today and for this I pay them homage!

1950's: The First Computer and Synth Play Music

Moving forward a few years to 1957 and enter the first computer into the electronic mix. As you can imagine, it wasn't exactly a portable laptop device but consumed a whole room and user friendly wasn't even a concept. Nonetheless creative people kept pushing the boundaries. One of these was Max Mathews (1926 -) from Bell Telephone Laboratories, New Jersey, who developed Music 1, the original music program for computers upon which all subsequent digital synthesis has its roots based. Mathews, dubbed the 'Father of Computer Music', using a digital IBM Mainframe, was the first to synthesize music on a computer.

In the climax of Stanley Kubrik's 1968 movie '2001: A Space Odyssey', use is made of a 1961 Mathews' electronic rendition of the late 1800's song 'Daisy Bell'. Here the musical accompaniment is performed by his programmed mainframe together with a computer-synthesized human 'singing' voice technique pioneered in the early 60's. In the movie, as HAL the computer regresses, 'he' reverts to this song, an homage to 'his' own origins.

1957 also witnessed the first advanced synth, the RCA Mk II Sound Synthesizer (an improvement on the 1955 original). It also featured an electronic sequencer to program music performance playback. This massive RCA Synth was installed, and still remains, at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, New York, where the legendary Robert Moog worked for a while. Universities and Tech laboratories were the main home for synth and computer music experimentation in that early era.

1960's: The Dawning of The Age of Moog

The logistics and complexity of composing and even having access to what were, until then, musician unfriendly synthesizers, led to a demand for more portable playable instruments. One of the first to respond, and definitely the most successful, was Robert Moog (1934-2005). His playable synth employed the familiar piano style keyboard.

Moog's bulky telephone-operators' cable plug-in type of modular synth was not one to be transported and set up with any amount of ease or speed! But it received an enormous boost in popularity with the success of Walter Carlos, as previously mentioned, in 1968. His LP (Long Player) best seller record "Switched-On Bach" was unprecedented because it was the first time an album appeared of fully synthesized music, as opposed to experimental sound pieces.

The album was a complex classical music performance with various multi-tracks and overdubs necessary, as the synthesizer was only monophonic! Carlos also created the electronic score for "A Clockwork Orange", Stanley Kubrik's disturbing 1972 futuristic film.

From this point, the Moog synth is prevalent on a number of late 1960's contemporary albums. In 1967 the Monkees' "Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd" became the first commercial pop album release to feature the modular Moog. In fact, singer/drummer Mickey Dolenz purchased one of the very first units sold.

It wasn't until the early 1970's, however, when the first Minimoog appeared that interest seriously developed amongst musicians. This portable little unit with a fat sound had a significant impact becoming part of live music kit for many touring musicians for years to come. Other companies such as Sequential Circuits, Roland and Korg began producing their own synths, giving birth to a music subculture.

I cannot close the chapter on the 1960's, however, without reference to the Mellotron. This electronic-mechanical instrument is often viewed as the primitive precursor to the modern digital sampler.

Developed in early 1960's Britain and based on the Chamberlin (a cumbersome US-designed instrument from the previous decade), the Mellotron keyboard triggered pre-recorded tapes, each key corresponding to the equivalent note and pitch of the pre-loaded acoustic instrument.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

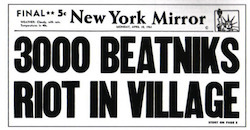

3000 Beatniks Riot

Half a century before Occupy Wall Street, young protesters occupied Greenwich Village's Washington Square Park. Like OWS, they ended up clashing with the police. Unlike OWS so far, their protest produced a small but practical and lasting change.

In the spring of 1961, the Washington Square Association, a community group of homeowners around the square, appealed to New York City's Department of Parks and Recreation to do something about the hundreds of "roving troubadours and their followers" playing music around the square's turned-off fountain on Sunday afternoons. They were mostly college kids, playing guitars and banjos and singing folk songs. The practice had started in the post-war years, when Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger planted the seeds of the folk musical revival in the Village. By 1961 it had grown enough that both the police and the neighbors found the "troubadours" and the tourists they attracted a nuisance. In his posthumously-published memoir, Dave Van Ronk recalls that there were various cliques in the park: a Zionist group singing and dancing "Hava Nagila," Stalinists, bluegrass fans, folk traditionalists. Black journalist John A. Williams reported that the locals' complaints were not really musical but social: "In the ensuing meetings with city officials, it became apparent that what was opposed was not so much folk singing as the increasing presence of mixed couples in the area, mostly Negro men and white women." In the late 1950s the parks commission began issuing permits to limit the number of musicians, allowing them to "sing and play from two until five as long as they had no drums," Van Ronk writes. This "kept out the bongo players. The Village had bongo players up the wazoo... and we hated them. So that was some consolation." He doesn't mention that those bongo-players were very often black. This racial aspect had an old historical precedent in Greenwich Village. In 1819, white residents of the area complained "of being much annoyed by certain persons of color practising as Musician with Drums and other instruments through the Village."

In 1961 the parks commissioner responded to the complaints by refusing to issue any permits at all. Izzy Young of the Folklore Center and others organized a peaceful protest demonstration. On Sunday, April 9, 1961, a few hundred young people gathered, attracting a few hundred more spectators. Among the latter was eighteen-year-old Dan Drasin, a mild-mannered kid who liked to hang out in the park. He brought one of the big, boxy film cameras of the era and documented the afternoon in a short black-and-white film, Sunday. The film shows clean-cut college and high school kids, many of the girls in Jackie O hairdos and heels, many of the boys looking like the young Allen Ginsbergs with serious, sensitive, owlish faces behind heavy black-framed glasses. They carry hand-written placards and cardboard guitars and argue with the dozens of beefy, florid-faced cops who've shown up. Izzy Young, also bespectacled and in jacket and tie, lectures the cops about the constitutional right to make music as the kids sit in a circle in the dry fountain and sing "This Land Is Your Land" and "The Star-Spangled Banner." As protests go it all looks low-key and polite. Then paddy wagons arrive and the cops haul off one nebbishy young man cradling an autoharp, pushing him into a prowl car. According to Drasin, most of the singers and musicians had left the park, leaving the few hundred spectators loitering around the fountain, when the cops' tempers finally boiled over. They wade into the crowd, shoving boys and girls to the ground, mauling them, dragging a handful into the paddy wagons. Reportedly they knocked some heads with their clubs, although it's not shown in the film. The whole event, Drasin says, lasted maybe two hours.

The next day, the New York Daily Mirror, the conservative Hearst tabloid, ran a giant war-is-over front page headline, "3000 BEATNIKS RIOT IN VILLAGE." Other local papers followed suit. That week's Voice scoffed at the Mirror's "hysterical" coverage, wondering if there were three thousand beatniks in the entire country that Sunday, let alone in Washington Square Park. By May, the outrage caused by the cops' overreaction forced the city to back down and issue permits, a practice that continues to this day.

Among the protesters hauled off that day was the Village character H. L. "Doc" Humes, identified in the Mirror as a "scofflaw" and the "mob leader." Humes was a gregarious polymath, a novelist and raconteur, co-founder of The Paris Review, designer of cheap housing made from old newspapers, director of a lost film updating the Don Quixote story as Don Peyote, LSD pioneer with Timothy Leary, later helper to Norman Mailer when he ran for mayor in 1969, later still a paranoid drug casualty who believed UFOs, CIA and the Pope in Rome were out to get him. He would not have been a stranger to the cops in the park that day. Just a few months earlier, he'd had a very public spat with Police Commissioner Stephen Kennedy.

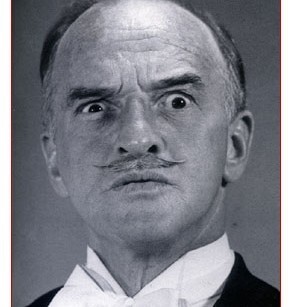

It started in October 1960, when cops shut down a performance by Lord Buckley at the Jazz Gallery in the East Village. Lord Buckley was a stately man with sleek gray hair and a pointy Daliesque mustache, who often performed in a tux and orated in a plummy, faux-British voice, seeming every bit the vaudeville and burlesque master of ceremonies he once was. But what came out of his mouth was pure hepcat jive he'd learned from the jazz musicians and pot-smokers with whom he'd associated since the 1930s. In the 1950s he started to recast biblical stories, historical texts like the Gettysburg Address, and Shakespeare in White Negro proto-rap: "Hipsters, flipsters and finger-poppin' daddies, knock me your lobes. I came here to lay Caesar out, not to hip you to him." It sounds like novelty schtick today, but in Eisenhower's America there was something inherently subversive about a man who looked like the maitre d' at a fancy restaurant jiving like a viper. "His Royal Hipness" had a lot of fans and friends downtown, where he performed and hung out whenever he was in New York.

The cops halted Buckley's gig because of a problem with his cabaret card. Since 1941, anyone who worked in a New York City nightclub, from performers to the hat check girl and the busboys, had to get fingerprinted and carry a picture ID card. If you had any police record, you couldn't have a card, which meant you couldn't work. It was intended to weed the Mob out of the nightclub business, but it could be disastrous for performers. Billie Holiday, Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker all had their cards yanked for drug violations; Lenny Bruce lost his because of an obscenity conviction; exotic dancer Sally Rand, refused a card in 1947 because the cops thought her fan dance too risqué, took the NYPD to court over it and won. Buckley lost his because he'd failed to report a pot bust that went back to the 1940s. Without the card, he couldn't perform in New York City, including a scheduled appearance on his old friend Ed Sullivan's tv show (they'd toured together with the USO during the war).

Despondent, Buckley called his pal Humes. Humes talked his Paris Review friend George Plimpton into letting Buckley give a little performance at a party in his Upper East Side apartment, with the idea that Plimpton's influential crowd might help him get Buckley's card reinstated. With Village jazzman David Amram at the piano, Buckley went into his schtick. The response was cool. Plimpton's literary swells had come to sip cocktails and talk about themselves, not listen to Village-y jazzbo jive. Buckley the old vaudevillian worked hard to win them over, pulling out bit after bit, overstaying his unwelcome. As the crowd grew increasingly bored and angry, Norman Mailer started heckling. Amram remembers that Buckley finally gave up, then "came over to the piano and whispered in my ear, 'Let's split and get out of here, man.'"

It turned out to be Lord Buckley's farewell performance. He died of a stroke shortly afterwards, at the age of fifty-four. Art D'Lugoff offered the use of the Village Gate for a memorial service, at which Ornette Coleman and Dizzy Gillespie played for a large crowd of Buckley's friends and admirers. He was laid to out at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel on the Upper East Side, New York's funeral home to the stars. (Rudolph Valentino, John Lennon, Jackie Onassis, Nikola Tesla, James Cagney, Igor Stravinsky, Norman Mailer, Heath Ledger, Judy Garland and Candy Darling were all laid out there.)

Humes, Mailer, Amram and others then started a public campaign to end the cabaret card system. Humes charged that police harassment had killed Buckley, and claimed that if Buckley had only slipped the right cop a hundred bucks the whole thing would have been settled under the table. That enraged Commissioner Kennedy, who retaliated by tossing Humes in jail for unpaid parking tickets and ordering up the biggest crackdown on cabarets and nightclubs in years, sending cops to more than 1200 venues looking for non-card-carrying workers. But this protest worked as well. Kennedy was sacked for his overreaction, and though it took another seven years, the cabaret card system was eventually abolished.

by John Strausbaugh

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Os 100 melhores filmes nacionais

Em 2015, a Associação Brasileira de Críticos de Cinema (Abraccine) publicou uma lista com os 100 melhores filmes brasileiros de todos os tempos de acordo com os votos de seus membros. Esta pesquisa foi a base para um livro chamado Os 100 Melhores Filmes Brasileiros, publicado em 2016. A idéia do ranking e do livro foi sugerida pela editora Letramento, com quem a Abraccine e a rede de televisão Canal Brasil co-lançaram o livro. A classificação foi feita com base em listas individuais feitas pelos 100 críticos da Abraccine, que inicialmente mencionaram 379 filmes. A lista completa foi disponibilizada ao público pela primeira vez em 26 de novembro de 2015, e o livro foi lançado em 1º de setembro de 2016.

A lista abrange quase todas as décadas entre a década de 1930 e a de 2010, sendo a única exceção a década de 1940. Um filme de 1931, Limite de Mário Peixoto, é o mais antigo e também o primeiro classificado, enquanto o mais recente é de 2015, A Segunda Mãe, de Anna Muylaert. A chanchada (comédias musicais dos anos 30-50) é representada por O Homem do Sputnik (1959), de Carlos Manga, enquanto há uma infinidade de filmes dos anos 60-1970, incluindo Cinema Novo e Cinema marginal. Quase um terço dos filmes era do período Retomada (1995 em diante), e a lista incluía não só longas-metragens, mas também documentários e curtas-metragens. O diretor do Cinema Novo, Glauber Rocha, é o cineasta com mais filmes na lista: cinco; seguido por Rogério Sganzerla, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Héctor Babenco e Carlos Reichenbach, cada um com quatro filmes.

1. Limite (1931), de Mario Peixoto

2. Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964), de Glauber Rocha

3. Vidas Secas (1963), de Nelson Pereira dos Santos

4. Cabra Marcado para Morrer (1984), de Eduardo Coutinho

5. Terra em Transe (1967), de Glauber Rocha

6. O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (1968), de Rogério Sganzerla

7. São Paulo S/A (1965), de Luís Sérgio Person

8. Cidade de Deus (2002), de Fernando Meirelles

9. O Pagador de Promessas (1962), de Anselmo Duarte

10. Macunaíma (1969), de Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

11. Central do Brasil (1998), de Walter Salles

12. Pixote, a Lei do Mais Fraco (1981), de Hector Babenco

13. Ilha das Flores (1989), de Jorge Furtado

14. Eles Não Usam Black-Tie (1981), de Leon Hirszman

15. O Som ao Redor (2012), de Kleber Mendonça Filho

16. Lavoura Arcaica (2001), de Luiz Fernando Carvalho

17. Jogo de Cena (2007), de Eduardo Coutinho

18. Bye Bye, Brasil (1979), de Carlos Diegues

19. Assalto ao Trem Pagador (1962), de Roberto Farias

20. São Bernardo (1974), de Leon Hirszman

21. Iracema, uma Transa Amazônica (1975), de Jorge Bodansky e Orlando Senna

22. Noite Vazia (1964), de Walter Hugo Khouri

23. Os Fuzis (1964), de Ruy Guerra

24. Ganga Bruta (1933), de Humberto Mauro

25. Bang Bang (1971), de Andrea Tonacci

26. A Hora e a Vez de Augusto Matraga (1968), de Roberto Santos

27. Rio, 40 Graus (1955), de Nelson Pereira dos Santos

28. Edifício Master (2002), de Eduardo Coutinho

29. Memórias do Cárcere (1984), de Nelson Pereira dos Santos

30. Tropa de Elite (2007), de José Padilha

31. O Padre e a Moça (1965), de Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

32. Serras da Desordem (2006), de Andrea Tonacci

33. Santiago (2007), de João Moreira Salles

34. O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro (1969), de Glauber Rocha

35. Tropa de Elite 2 – O Inimigo Agora é Outro (2010), de José Padilha

36. O Invasor (2002), de Beto Brant

37. Todas as Mulheres do Mundo (1967), de Domingos Oliveira

38. Matou a Família e Foi ao Cinema (1969), de Julio Bressane

39. Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos (1976), de Bruno Barreto

40. Os Cafajestes (1962), de Ruy Guerra

41. O Homem do Sputnik (1959), de Carlos Manga

42. A Hora da Estrela (1985), de Suzana Amaral

43. Sem Essa Aranha (1970), de Rogério Sganzerla

44. SuperOutro (1989), de Edgard Navarro

45. Filme Demência (1986), de Carlos Reichenbach

46. À Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma (1964), de José Mojica Marins

47. Terra Estrangeira (1996), de Walter Salles e Daniela Thomas

48. A Mulher de Todos (1969), de Rogério Sganzerla

49. Rio, Zona Norte (1957), de Nelson Pereira dos Santos

50. Alma Corsária (1993), de Carlos Reichenbach

51. A Margem (1967), de Ozualdo Candeias

52. Toda Nudez Será Castigada (1973), de Arnaldo Jabor

53. Madame Satã (2000), de Karim Ainouz

54. A Falecida (1965), de Leon Hirzman

55. O Despertar da Besta – Ritual dos Sádicos (1969), de José Mojica Marins

56. Tudo Bem (1978), de Arnaldo Jabor (1978)

57. A Idade da Terra (1980), de Glauber Rocha

58. Abril Despedaçado (2001), de Walter Salles

59. O Grande Momento (1958), de Roberto Santos

60. O Lobo Atrás da Porta (2014), de Fernando Coimbra

61. O Beijo da Mulher-Aranha (1985), de Hector Babenco

62. O Homem que Virou Suco (1980), de João Batista de Andrade

63. O Auto da Compadecida (1999), de Guel Arraes

64. O Cangaceiro (1953), de Lima Barreto

65. A Lira do Delírio (1978), de Walter Lima Junior

66. O Caso dos Irmãos Naves (1967), de Luís Sérgio Person

67. Ônibus 174 (2002), de José Padilha

68. O Anjo Nasceu (1969), de Julio Bressane

69. Meu Nome é… Tonho (1969), de Ozualdo Candeias

70. O Céu de Suely (2006), de Karim Ainouz

71. Que Horas Ela Volta? (2015), de Anna Muylaert

72. Bicho de Sete Cabeças (2001), de Laís Bondanzky

73. Tatuagem (2013), de Hilton Lacerda

74. Estômago (2010), de Marcos Jorge

75. Cinema, Aspirinas e Urubus (2005), de Marcelo Gomes

76. Baile Perfumado (1997), de Paulo Caldas e Lírio Ferreira

77. Pra Frente, Brasil (1982), de Roberto Farias

78. Lúcio Flávio, o Passageiro da Agonia (1976), de Hector Babenco

79. O Viajante (1999), de Paulo Cezar Saraceni

80. Anjos do Arrabalde (1987), de Carlos Reichenbach

81. Mar de Rosas (1977), de Ana Carolina

82. O País de São Saruê (1971), de Vladimir Carvalho

83. A Marvada Carne (1985), de André Klotzel

84. Sargento Getúlio (1983), de Hermano Penna

85. Inocência (1983), de Walter Lima Jr.

86. Amarelo Manga (2002), de Cláudio Assis

87. Os Saltimbancos Trapalhões (1981), de J.B. Tanko

88. Di (1977), de Glauber Rocha

89. Os Inconfidentes (1972), de Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

90. Esta Noite Encarnarei no Teu Cadáver (1966), de José Mojica Marins

91. Cabaret Mineiro (1980), de Carlos Alberto Prates Correia

92. Chuvas de Verão (1977), de Carlos Diegues

93. Dois Córregos (1999), de Carlos Reichenbach

94. Aruanda (1960), de Linduarte Noronha

95. Carandiru (2003), de Hector Babenco

96. Blá Blá Blá (1968), de Andrea Tonacci

97. O Signo do Caos (2003), de Rogério Sganzerla

98. O Ano em que Meus Pais Saíram de Férias (2006), de Cao Hamburger

99. Meteorango Kid, Herói Intergaláctico (1969), de Andre Luis Oliveira

100. Guerra Conjugal (1975), de Joaquim Pedro de Andrade (*)

101. Bar Esperança, o Último que Fecha (1983), de Hugo Carvana (*)

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

COSITAS QUE TIENE CUBA con Gaspar Marrero En Guantánamo – Orquesta Sensación con Abelardo Barroso "Una noche, en el antiguo cabaret habanero nombrado La Campana, se reunieron Jesús Gorís, propietario de los discos Puchito; Rolando Valdés, director de la Orquesta Sensación, y un veterano cantante entonces retirado. Este hace una petición: Rolando, yo quisiera grabar con tu orquesta un bolerito. Rolando Valdés sabía quién era aquel hombre. Había hecho época con el Sexteto Habanero y con el danzonete de los años 1930."... https://herenciarumberaradio.com/en-guantanamo-abelardo-barroso-con-la-orquesta-sensacion/ En COSITAS QUE TIENE CUBA," En Guantánamo"- Orquesta Sensación con Abelardo Barroso También pueden disfrutar de esta obra discográfica que forma parte de la historia de la música cubana en Estreno cada lunes y durante toda la semana al minuto 50 en la programación regular de Herencia Rumbera Radio vía nuestras plataformas virtuales Descarga y actualiza nuestra app https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=red.simpleapp.herenciarumbera Página Web https://www.herenciarumberaradio.com/ TuneIn https://tunein.com/radio/Herencia-Rumbera-s268720/ Radio Garden http://radio.garden/listen/herencia-rumbera-radio/7vF-acFD Únete a nuestro Canal de Telegram https://t.me/herenciarumberaradio Grupo de Chat Telegram: https://t.me/hrumberachat Listas de Radio Raddios https://www.raddios.com/12968-radio-online-herencia-rumbera-radio-online-lima-peru Radio Box https://onlineradiobox.com/pe/herenciarumbera/ Radios.com https://radios.com.pe/herencia-rumbera My Tuner https://mytuner-radio.com/radio/herencia-rumbera-433815/ Radio Streema https://streema.com/radios/Herencia_Rumbera Radio es https://www.radio.es/s/herenciarumbera Herencia Rumbera Radio difundiendo la Música Cubana y Afrolatina de todos los tiempos #HerenciaRumberaRadio #CositasQueTieneCuba #EnGuantánamo #OrquestaSensación #AbelardoBarroso https://www.instagram.com/p/CeheFiJMS3I/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

I was tagged by @bironism - merci mille fois, chérie! These questions were so inspiring!

Rules: answer the following questions and tag 10 blogs you would like to get to know.

What movie do you wish you were a character in?

The Third Man or some other post- (or pre-) war noir/espionage thriller for the intrigue and mystery of it all, The English Patient for the grand and tragic romance, most of all I’d like to be a Nouvelle Vague heroine/the subject of some Nadja à Paris-type documentary. Or The Love Witch for the costumes/makeup/magic powers.

Create your dream fragrance; what would the ingredients be like?

I don’t know much about the science of scent but my perfume would be dark and classic, have a slight tingle reminiscent maybe of incense or sandalwood or old dusty books, with some notes of camellia and citrus to give it a little lift.

As a siren, what bewitching song would you sing to lure people to their doom?

I’d probably like to live my fantasies of being a tragic jazz bar singer in the 1930s so my repertoire would be songs in various languages from this era, plus a lot of old French chansons (think Jacques Brel, Piaf, Juliette Gréco, probably some Gainsbourg)

*clicks shoes together three times* Anywhere in the world (fantasy or reality) where would you go?

I’d give anything to see the following cities in the 50s/60s: Paris, London, New York (also the 70s), Rome, Berlin (also 20s Berlin), I’d go to fin-de-siècle Vienna and Budapest, pre-Revolution Iran, pre-war Syria, Byzantine Turkey... as for realistic travels, the next places on my agenda that I am really desperate to see are Russia and the Baltic States (in autumn if possible), Greece and the Balkan states, more of Turkey, and India.