#A ROMAN BRONZE SPHINX

Text

A ROMAN BRONZE SPHINX

CIRCA 1ST CENTURY B.C. - 1ST CENTURY A.D.

Representations of sphinxes are known in Egyptian, Greek and Roman art, from the Great Sphinx in Giza dating the 4th Dynasty to diminutive 3rd Century Roman intaglios: it was a popular subject matter. Originally the sphinx was an Egyptian invention - the term comes from the Egyptian shepesankh or 'living statue', combining a human head with the body of a lion. In Egyptian times they were seen as protectors of temples and sanctuaries or as an image of royalty with the face of the Pharaoh. This Roman bronze however, is a more sensuous winged representation, seated and pushing back on her front legs with her body raised and head thrown back, her breasts are visible and her ribcage beneath. The details of her hair and wings are finely incised.

The dating of this bronze sphinx suggests that she would have been made during the rule of Augustus, whose seal ring, that he had inherited from his adoptive father, Julius Ceasar, depicted a sphinx. Augustus also employed the device of a seated sphinx on some of his coins minted circa 20 B.C.

#A ROMAN BRONZE SPHINX#CIRCA 1ST CENTURY B.C. - 1ST CENTURY A.D.#bronze#bronze statue#bronze sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman art

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780 - 1867)

Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1808

National Gallery, London

Oedipus, a figure from Greek mythology, stands nude and in profile before the Sphinx, who guards the entrance to the ancient city of Thebes. The Sphinx – a monster with the face, head and shoulders of a woman, a lion’s body, and bird’s wings – asks Oedipus to solve the riddle she poses to all travellers seeking to enter the city: ‘What has a voice and walks on all fours in the morning, on two at noon, and on three in the evening?’ Oedipus correctly answers that it is man who crawls on all fours as a child, walks on two legs as an adult, and uses a walking stick as a third leg in old age. The bones of a previous traveller, killed by the Sphinx for having failed to solve the riddle, lie at the bottom of the picture. Thebes is visible in the distance on the right.

The theme of a monster defeated by human intelligence clearly appealed to Ingres. The picture also complements another of his paintings, Angelica saved by Ruggierro, which shows a chivalrous knight attacking a sea monster to save a princess. But this is also a painting of a man facing his destiny, as Oedipus’s actions will lead him to become King of Thebes, as the oracle predicted at his birth, and to unknowingly marry his own mother, Jocasta. This unwitting tragedy and its consequences is the drama of Oedipus Rex, the middle play of Sophocles' Theban Plays.

This painting is a later, and smaller, version of one painted in 1808 and subsequently reworked in 1827 (Louvre, Paris). The first version of Oedipus and the Sphinx was essentially a figure study that Ingres painted while studying at the French Academy in Rome. It was sent to Paris to be judged by members of the Institut de France. As required by the Institut’s rules, the figure of Oedipus was based upon a live model, although the pose was derived from the classical statue, Hermes Fastening his Sandal (Louvre), a Roman marble copy of a lost Greek bronze. Oedipus’s body is presented as an arrangement of geometrical shapes; for example, the triangle formed by his left arm, thigh and chest is mirrored and inverted by his left upper arm and forearm. The use of profile for both Oedipus and the Sphinx, together with the shallow space in much of the picture, recalls classical friezes and ancient Greek vases, which Ingres used as the sources for his deliberately classical artistic style.

#Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres#French art#mediterranean#art#fine arts#1800s#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#oil painting#europa#mythology#mythological art#classical#Oedipus and the Sphinx#1808#painting#artwork

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dating to the third century, the bronze sphinx statue originated from Dacia, a Roman province that largely corresponds to modern-day Romania.

After being discovered in the 19th century, the statue was stolen from a European count sometime around 1848, Revesz said.

While it was never recovered, a detailed drawing of the sphinx remained. In the drawing, the inscription — composed of a handful of characters — can be seen on the base of the statue.

Translated into English, it reads: “Lo, behold, worship: here is the holy lion.”

Photo from the journal Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nothing but a drawing remains to remind one of the Dacian Sphinx, a bronze statue of a sphinx from the Ancient Roman province of Dacia (modern Romania) dated to be made in the 3rd century AD. The statue, discovered in the 19th century, was stolen and lost. The remaining drawing, though, is detailed enough to be studied.

The inscription under the Sphinx had puzzled scientists for a while, but the mystery has been resolved in the recent study by Peter Revesz, a professor at the University of Nebraska. He has concluded that the Sphinx was used by its original creators in votive means. He noticed the mirroring in the inscription and concluded that the writing is a proto-Hungarian metric poem written with Greek letters that says, if translated: Lo, behold, worship: here is the holy lion.

It is rather noteworthy that it has been decoded because, according to Revesz, the cult of the Sphinx was not a part of the mainstream Roman mythology. It provides an intriguing look into Rome's "minority religion".

Source: 🏺

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian Gods on Christian Era Roman Coins

Constantius II, festival of Isis issue, struck 352-355

Obverse depicts diademed bust of Constantius facing right.

Reverse depicts Anubis, standing left, holding caduceus and sistrum.

The festival of Isis coins are some of the most fascinating pieces struck by Rome in my opinion, especially when taking into consideration that these coins depicting Egyptian deities were still struck under notoriously Christian emperors.

Festival of Isis bronze, 4th century

Obverse depicts bust of Isis facing right, wearing hem-hem crown.

Reverse depicts Harpocrates standing left and holding a cornucopia

The festival itself was held to commemorate the arrival of the ship of Isis that departed from Alexandria and arrived in Rome on March 5th. The last known emperor depicted on a festival of Isis issue is Valentinian II, and the festival would stop being held in the city of Rome around 416.

Festival of Isis medallion, Valentinian I, 364-375

Obverse depicts diademed bust of Valentinian I facing right.

Reverse depicts Isis, holding sistrum and scepter, riding on Sothis.

Crispus, Festival of Isis issue, 316-326

Obverse depicts bust of Crispus facing right.

Reverse depicts Isis Pharia on galley, standing to left, head facing right, holding sistrum.

Festival of Isis bronze, 4th century.

Obverse depicts bust of Sol-Serapis facing right.

Reverse depicts winged sphinx advancing right.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Days of Deity Devotion

Day 3: Symbols and Icons of Athena

The Aegis — Made for Zeus but most often in use by Athena and Apollon, the aegis was originally a goat skin or shield with a gorgoneion and the power to cause panic. Later, it became a scaled breastplate as seen in a lot of art we have available today. Learn more

The Gorgoneion — A common apotropaic (protective) symbol of a gorgon (think Medusa) head.

Helmet (Corinthian Style) — This style of helmet is the one most frequently depicted in art.

Spear, Shield, Sword, Armor — All relate to Athena's war and protection aspect

Distaff and spindle — Used in weaving

Owls — The Little Owl was considered Athena's sacred bird, representing or accompanying her. It was depicted on Athenian coins, and often with her in art.

Snakes — Snakes are another sacred animal to her depicted with her in art works. Snakes symbolized wisdom and were also linked to Athena's adopted son and mystical king of Athens, Erectheus.

Horses, the Chariot — Poseidon was the father of horses, but Athena was the one who invented the bridle and chariot, she was the force that tamed horses for humans to ride.

Olive Tree, Olives — Just as Athena took the wild horse and tamed it, she also taught humans to cultivate the olive tree to make olive oil. In one myth, she gifted an olive tree to the city of Athens in a contest against Poseidon, after which the city adopted her name.

+The Sphinx — Often appears on her helmet, possibly relating to her aspect of cunning.

+Ivy — There is a regional epithet of hers which means "of the ivy", Athena Kissaia

Colors — Blue, Grey, Gold, Red, Ivory, Bronze (Some include emerald green too)

UPG Section

Books and Scrolls — I mean fairly obvious, right?

Knitting/Crochet Needles and Loom — Weaving aspects.

Spiders — Not because of the Roman myth (I'm more hard polytheist), just from experience and also because it makes sense. Most spiders are weavers, and patiently trap and ambush their prey. They even lure prey to them by plucking threads of their webs in some cases. They are more intelligent than we think, capable of foresight, planning and other complex mental processes!

Computers/Technology — To go with my UPG about her being patron of technology which I will cover later on.

Bees — I don't know if it is just to mess with me or not because I also worship Apollon but apparently she also likes bees and sends them as signs to me, but also I think it makes sense? It's fairly new so idk I might edit this out later if it turns out to be incorrect/miscommunication.

#30 days of deity devotion#helpol#paganism#athena devotion#hellenistic pagan#athena#hellenistic polytheism#athena deity#info post#upg/spg

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many ancient writers supported Herodotus’ record of underground passages connecting major pyramids, and their evidence casts doubt on the reliability of traditionally presented Egyptian history. Crantor (300 BC) stated that there were certain underground pillars in Egypt that contained a written stone record of pre-history, and they lined accessways connecting the pyramids. In his celebrated study, On the Mysteries, particularly those of the Egyptians, Chaldeans and the Assyrians; Iamblichus, a fourth-century Syrian representative of the Alexandrian School of mystical and philosophical studies, recorded this information about an entranceway through the body of the Sphinx into the Great Pyramid.

“This entrance, obstructed in our day by sands and rubbish, may still be traced between the forelegs of the crouched colossus. It was formerly closed by a bronze gate whose secret spring could be operated only by the Magi. It was guarded by public respect, and a sort of religious fear maintained its inviolability better than armed protection would have done. In the belly of the Sphinx were cut out galleries leading to the subterranean part of the Great Pyramid. These galleries were so artfully crisscrossed along their course to the Pyramid that, in setting forth into the passage without a guide throughout this network, one ceasingly and inevitably returned to the starting point.”

Local 19th-century Arab lore maintained that existing under the Sphinx are secret chambers holding treasures or magical objects. That belief was bolstered by the writings of the first-century Roman historian Pliny, who wrote that deep below the Sphinx is concealed the “tomb of a ruler named Harmakhis” that contains great treasure”, and, strangely enough, the Sphinx itself was once called "The Great Sphinx Harmakhis" who mounted guard since the time of the Followers of Horus”. The 4th-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus made additional disclosures about the existence of subterranean vaults that appeared to lead to the interior of the Great Pyramid.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The bronze sphinx statue, dating to the third century, was discovered in Dacia, a Roman province corresponding to modern-day Romania. The bronze sphinx statue bears several striking similarities to the famous Naxians’ Sphinx from 560 BCE.

Dacia is the ancient name for Romania and has seen the rule of various groups and empires throughout history. During ancient times, Dacia was part of the Dacian Kingdom before it was conquered by Rome.

It was determined that the inscription around the base of a bronze sphinx statue was written using the archaic Greek alphabet. However, the Greek alphabet phonetic values render a text that is non-sensical in the Greek language.

The words were written from left to right. The scribe was most likely attempting to express something in a language other than Greek by employing an archaic Greek alphabet. The phonetic values of the archaic Greek alphabet record a short rhythmic poem in Proto-Hungarian.

#history#archeology#archeologicalsite#sphinx#dacia#romanian#greek alphabet#language translation#decipher#inscription

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ancient Egyptian History in a nutshell

Pre-Dynastic Period (4,400-3,000 B.C): Egypt was united by Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson circa 2002

Early Dynastic Period (3,000-2,686 B.C): nothing important

Old Kingdom (2,686-2,160 B.C): Pyramids, Mastabas and Sphinxes, oh my

1st Intermediate Period (2,160-2,055 B.C): Civil Wars and Droughts

Middle Kingdom (2,055-1,650 B.C): more pyramids and more writing

2nd Intermediate Period (1,650-1,550 B.C): see Joseph: King of Dreams

New Kingdom (1,550-1,069 B.C): Hatshepsut, Aten, Deliver Us and the Bronze Age Collapse

3rd Intermediate Period (1,069-664 B.C): Nubia takes over, and the Ark of the Covenant is in Tanis

Late Period (664-332 B.C): Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians, oh my

Ptolemaic Period (332-30 B.C): nothing but Ptolemies and Cleopatras

Roman Period (30 B.C-395 A.D): grain and Christianity

0 notes

Text

Historical Accuracy

The discourse around Netflix’s Ancient Apocalypse is fascinating to me. I haven’t seen it and i know next to nothing about it’s creator, Graham Hancock, but the vitriol around this man and his theories is f*cking intense. The academic establishment hates this man and the media is definitely following suit. This man dares to postulate that there was a pre-Ice Age, sea fairing culture that suffered a fall, leading to it’s people integrating with the hunter-gatherers of the time and teaching them the seeds of society. He believes that there is ample evidence around the world pointing to this, Gobekli Tepe being a hug one. If you don’t know, Tepe is a civilization dating back almost twelve thousand years, who built a monolithic civilization something thought not possible until thousands of years later. There’s even evidence that the Sphinx in Egypt is much, much, older than what is common accepted. For all of these “insane” theories, Hancock is seen as a fraud and dangerous but, like, how?

Why is it so hard for people to accept that what we know as history is just a snippet of what we are? It feels like every other month, our genesis as a species is pushed back a couple dozen millennia. More than that, why is it so hard to believe that these people, who lived in a completely different version four world, was able to harness a completely different yet similar technology to ours? Roman streets still exist to this date, flawless in their construction, but our modern streets are riddled with potholes. We found legitimate Orichalcum at the bottom of the Mediterranean sea but that sh*t was considered mythological until then. No one even knows what Greek Fire is, but it, for sure, was used as a weapon of mass destruction back during the Bronze Age. Hell, no one even knows what caused the Bronze Age collapse and that sh*t was well within the wheelhouse of written historic record. Why is it so wild to believe that there was a civilization that had existed long enough to develop sea faring tech, long before other people? Why is it so hard to believe that there were isolated pockets of people who just observed the world closer than most, and decided to f*ck around and find out? That’s all it takes to develop anything really.

It’s incredibly disrespectful and wildly dismissive to just write off these theories, especially when they point to these advanced civilizations being from Africa or the Far East. I absolutely believe Atlantis existed and that it was situated in West Africa before that sh*t got washed away during a glacial melt. There is a ton of f*cking evidence which supports The Eye of Africa in Mauritania, being the site of the mythological super power. Imagine that. Imagine this very narrow, Eurocentric view of “history” which paints ancient Egyptians as Greeks (even though the Ptolemys were the last of the Dynastic families and literally caused the downfall of the millennia old civilization), absolutely eviscerated by the revelation that one of the oldest, most advanced cultures in the history of man, were African. Like, so far away from that light-skinned Middle Eastern by way of white folks narrative perpetuated throughout schools, African. And that’s just one of these pre-Ice Age civilizations. I personally believe there were many, many, more.

Civilization ebbs and flows. In ten thousand years, we will be long gone and whoever comes after us will think us primitive. They’ll come across our combustion engines and think, “Really?” I’m sure their tech will be just as advanced, maybe moreso maybe not, but it will look the same. It will do the same things but they would have gotten to that answer in a different way than us. Ingenuity isn’t tied to a level of intelligence, it just takes patience and experimentation. What has that got to do with Hancock and his black listing from modern academia? Absolutely everything. IF we know that tech, society, and civilization rise and fall at pretty regular intervals, then why is it so hard for anyone to think that sh*t started earlier? Why is it so hard to believe that sh*t existed in an advanced state, one alien to our perception of what advanced even is, but fell due to a complex system of issues? No one knows why agriculture started, they just have an idea of when. No one knows why we began to build, we just have an idea of when; One that keeps getting pushed farther and farther back. It’s not a stretch to think our story started much, much, earlier than we have accepted and it’s weird to me that there is so much resistance to this notion.

0 notes

Photo

Discoveries in Pompeii Reveal Lives of Lower and Middle Classes

The latest discoveries in the excavation of Pompeii’s Regio V neighborhood are fully furnished utility spaces, of great archaeological significance for the details they preserve of a common domestic context in the 1st century Roman town.

The room was found in the House of the Enchanted Garden, a beautifully frescoed home with a lararium (a shrine to the household gods) that is one of the largest ever discovered in Pompeii. In 2021, archaeologists undertook an excavation and restoration of rooms on the ground floor in front of the lararium and the stories above it. They uncovered four rooms, two on the ground floor and two above, that were furnished. One was unfinished, with unplastered walls and an earthen floor, a jarring contrast in a house so decorated with such fine frescoes. The unfinished room was used for storage.

Archaeologists were able to make casts of the furnishings in the room which left a cavity in the hardened ash that could be filled with plaster. One room contained a bed frame and a pillow. The texture of the fabric was imprinted in the ash and is visible on the plaster cast. It is a very simple cot with ropes strung across the sides. There isn’t even a mattress, let along any decoration. Next to the bed was a wooden trunk divided into two compartments. The lid was open, but broken when the beams and floorboards of the story above collapsed in the eruption. Inside the trunk, archaeologists found a terra sigillata saucer and a double-spouted oil lamp depicting Zeus in the act of transforming into an eagle. Next to the trunk was a circular three-legged table with a shallow ceramic bowl containing two small glass bottles, a blue glass saucer and a terra sigillata bowl.

In the storage room, archaeologists were able to make two casts: a shelf and a group of wooden planks in different sizes, cuts and finishes, tied together. This was probably a collection of raw materials for assorted home maintenance projects from furniture patching to roof repair. Outside the room in a small hallway another utilitarian treasure was found: a tall wooden cabinet with at least four doors and five internal shelves. The top of the wardrobe and the front doors were damaged when the floor above the room collapsed. The remains of jugs, amphorae, bowls and plates were found on the damaged top shelf.

The excavation of the upper rooms revealed materials that were in the process of collapsing onto the rooms below. Of enormous archaeological value is a unique group of wax writing tablets. The group consists of seven triptychs tied both vertically and horizontally by a cord. A large cupboard, collapsed in the eruption, was also excavated. It contained different types of common use ceramics for kitchen and dining, as well as fine terra sigillata ceramics and glass. There was also a set of small bronze vessels, including a basin with palm leaf-shaped handles and a small jug decorated with a sphinx and lion’s head. Another special treasure is an incense burner shaped like a cradle with a male figure at one end. The polychrome paint coloring the figure and decorating the cradle with geometric designs is perfectly preserved.

The excavation overlapped onto a residential property behind the House of the Enchanted Garden, and there the plaster cast technique revealed the imprint of cane lathing in the mortar of a collapsed false ceiling. The cast shows the guts of Pompeiian construction: bundles of caning tied together by a thin cord and covered by a gauze-like fabric to separate the lathing from the wet mortar. Casts were also obtained of what appears to be wood paneling on the north, east and south walls of the room. Some are carved with coffered decoration; others are inlaid with delicate bone elements.

#Discoveries in Pompeii Reveal Lives of Lower and Middle Classes#House of the Enchanted Garden#archeology#archeolgst#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman empire#roman history

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Accuracy

The discourse around Netflix’s Ancient Apocalypse is fascinating to me. I haven’t seen it and i know next to nothing about it’s creator, Graham Hancock, but the vitriol around this man and his theories is f*cking intense. The academic establishment hates this man and the media is definitely following suit. This man dares to postulate that there was a pre-Ice Age, sea fairing culture that suffered a fall, leading to it’s people integrating with the hunter-gatherers of the time and teaching them the seeds of society. He believes that there is ample evidence around the world pointing to this, Gobekli Tepe being a hug one. If you don’t know, Tepe is a civilization dating back almost twelve thousand years, who built a monolithic civilization something thought not possible until thousands of years later. There’s even evidence that the Sphinx in Egypt is much, much, older than what is common accepted. For all of these “insane” theories, Hancock is seen as a fraud and dangerous but, like, how?

Why is it so hard for people to accept that what we know as history is just a snippet of what we are? It feels like every other month, our genesis as a species is pushed back a couple dozen millennia. More than that, why is it so hard to believe that these people, who lived in a completely different version four world, was able to harness a completely different yet similar technology to ours? Roman streets still exist to this date, flawless in their construction, but our modern streets are riddled with potholes. We found legitimate Orichalcum at the bottom of the Mediterranean sea but that sh*t was considered mythological until then. No one even knows what Greek Fire is, but it, for sure, was used as a weapon of mass destruction back during the Bronze Age. Hell, no one even knows what caused the Bronze Age collapse and that sh*t was well within the wheelhouse of written historic record. Why is it so wild to believe that there was a civilization that had existed long enough to develop sea faring tech, long before other people? Why is it so hard to believe that there were isolated pockets of people who just observed the world closer than most, and decided to f*ck around and find out? That’s all it takes to develop anything really.

It’s incredibly disrespectful and wildly dismissive to just write off these theories, especially when they point to these advanced civilizations being from Africa or the Far East. I absolutely believe Atlantis existed and that it was situated in West Africa before that sh*t got washed away during a glacial melt. There is a ton of f*cking evidence which supports The Eye of Africa in Mauritania, being the site of the mythological super power. Imagine that. Imagine this very narrow, Eurocentric view of “history” which paints ancient Egyptians as Greeks (even though the Ptolemys were the last of the Dynastic families and literally caused the downfall of the millennia old civilization), absolutely eviscerated by the revelation that one of the oldest, most advanced cultures in the history of man, were African. Like, so far away from that light-skinned Middle Eastern by way of white folks narrative perpetuated throughout schools, African. And that’s just one of these pre-Ice Age civilizations. I personally believe there were many, many, more.

Civilization ebbs and flows. In ten thousand years, we will be long gone and whoever comes after us will think us primitive. They’ll come across our combustion engines and think, “Really?” I’m sure their tech will be just as advanced, maybe moreso maybe not, but it will look the same. It will do the same things but they would have gotten to that answer in a different way than us. Ingenuity isn’t tied to a level of intelligence, it just takes patience and experimentation. What has that got to do with Hancock and his black listing from modern academia? Absolutely everything. IF we know that tech, society, and civilization rise and fall at pretty regular intervals, then why is it so hard for anyone to think that sh*t started earlier? Why is it so hard to believe that sh*t existed in an advanced state, one alien to our perception of what advanced even is, but fell due to a complex system of issues? No one knows why agriculture started, they just have an idea of when. No one knows why we began to build, we just have an idea of when; One that keeps getting pushed farther and farther back. It’s not a stretch to think our story started much, much, earlier than we have accepted and it’s weird to me that there is so much resistance to this notion.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Archaeological Museum of Patra

Marble sarcophagus of attic type. On the long side is depicted a hunting scene. Two riders attack a lion and a lioness. The other long side is decorated with griffins and the short ones with Sphinxes. The scenes are related with eschatological beliefs. It was displayed in the area of the Roman Odeon.

Patras, Roman Period (150-175 A.D)

Entombment in this type of sarcophagi is rare, but well-preserved through time. A more common type of burial in the Roman period was within cinerary urns after the deceased had been cremated. Of particular interest are these cinerary urns imported from Italy:

The cinerary urns from the ancient cemeteries of Patras mostly date from Roman times. Clay and subsequent glass vessels were commonly usued for collecting ashes, while rectangular marble containers (cists) were used for the wealthy. These bear the quadrangular panel and relief decoration with symbols related to death and the afterlife. These objects were imported from Italy and since they date from the 1st cent. A.D. , they are believed to belong to the generation of Roman veterans who had not yet been Hellenized and kept the customs of their land of origin.

Cremation was an expensive custom, not seen frequently in the region before the Classical period, with the exception of some cases during the Bronze Age, but it became quite common during the Roman period.

Cremation demanded the opening of a deep, spacious trench in the ground, where the pyre was prepared with wood and branches. The deceased was laid on top of the pyre often in their coffin. On the pyre or around it were placed offerings. After the cremation process the remains were either left inside the trench and buried, or they were collected and stored in cinerary urns.

------------------

Recognize my worth, before I end up in one of these*, and donate a little something for this blogger / photographer:

https://ko-fi.com/isabia

If I were a burial what would I be? Would I be in a cist grave? Would I be in an elaborate sarcophagus? Would I be just dumped under a mound of rocks? Would they inter me in pot, or simply cover me with a couple of roof tiles? Or would end up in the tight confines of a cinerary urn?

#ancient greece#tagamemnon#burial customs#cinerary urns#urn#Sarcophagi#sarcophagus#greece#greek roman period#archaeology#classical studies#patra#Marble artifacts#marble reliefs#relief#greek museums#archaeological museum of patra#archaeological museums#museums#αρχαία ελλάδα#ελλάδα#πάτρα

503 notes

·

View notes

Text

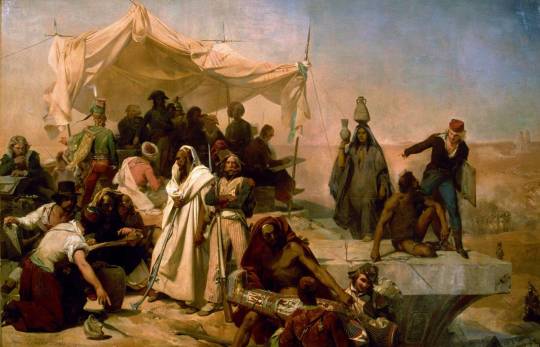

"Retour d'Egypte"

In this last year of the eighteenth century, the Parisian public rushed to grant Egypt the favors of fashion, when cabinetmakers, goldsmiths, painters and sculptors invented the "Retour d'Egypte" style (admittedly already in use in Rome by Piranesi in 1769 and in Paris by Séné in 1780), which was all the rage at the time: bronze figures wearing klaft supporting tables, consoles or pedestal tables, precious armchairs adorned with armrests in the shape of a sphinx, palm-shaped marquees, clocks influenced by Coptic art entered in force in the salons of the Faubourg Saint-Germain [..]

Bonaparte's own stepson, the future Prince Eugene, former member of the expedition, had his Parisian hotel in the rue de Lille overhauled [..] where the architect Bataille fits out an Egyptian-style portico and furnishes the apartments with an oriental boudoir decorated with a frieze representing a slave market and a harem. The rue de Sèvres is equipped with the famous Fellah fountain to distribute the waters of Gros-Caillou to the district. The English are not left out with the prestigious neo-Egyptian decorations created by Thomas Hoper in his London hotel on Duchess-Street or by Walsh Porter in his cottage in Craven. As for the pyramids, one now sees them in all the gardens (such as in Parc Monceau), but even more in the cemeteries, in Père-Lachaise mainly, under which several members of the expedition will be buried, the surgeon Dominique Larrey in particular. [..]

[Léon Cogniet (1794-1880)- L'expédition d'Egypte sous les ordres de Bonaparte.]

Even today, several streets in Paris evoke the expedition, such as the streets of Aboukir, Cairo or Heliopolis. And throughout the 19th century, the memory of the expedition made it possible to establish between France and Egypt privileged relations which reached their peak under the reign of Charles X [..] The expedition, again, provided painters the revelation of azure skies and golden light which, with Gros, Lancret, Chabrol, Lejeune, and later Delacroix, gave birth to the orientalist current expressed throughout the 19th century until the Third Republic. Egypt, of course, also inspired writers and travelers of the romantic era, such as Alexandre Dumas with his Voyage au Sinaï, Théophile Gautier with the Roman de la momie, Alfred de Vigny with the Plainte du Capitaine, but also Chateaubriand, Balzac, Flaubert, Nerval and Hugo, all fascinated by this real or imagined country.

Gonzague Saint-Bris- Desaix, le sultan de Bonaparte

#napoleonic#gonzague saint bris#desaix le sultan de bonaparte#retour d'égypte#arts and crafts#campaign of egypt

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeological Adventures in Egypt

Hello! I am Dr. Lisa Saladino Haney, Assistant Curator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and resident Egyptologist. An Egyptologist is someone who studies the history, material culture, architecture, religion, and writing of the ancient Egyptians – one of the ancient cultural groups living in Africa’s Nile Valley. Learning about ancient cultures helps us to better understand the world today and to appreciate the creativity and ingenuity of people who lived thousands of years ago. Archaeology is one technique that allows us to interact with and study the past and there are hundreds of archaeological sites and projects throughout the Nile Valley that constantly add to our understanding of what life was like.

Trying to determine some of my favorite archaeological sites from my travels in Egypt turned out to be an impossible task! Please join me on this photo exploration of a few of the many interesting archaeological sites in Egypt and learn where you can find more information about active archaeological excavations and other projects going on in those areas.

Saqqara

Saqqara is an important cemetery site associated with the ancient Egyptian capital city of Memphis, near modern Cairo. The cemeteries at Saqqara contain a number of tombs, both royal and private, including the famous Step Pyramid of the Third Dynasty Egyptian king, Djoser (ca. 2630-2611 BCE). The earliest burials at the site date to the creation of the ancient Egyptian state and it remained an important site through the Graeco-Roman Period.

Royal Tombs: The Step Pyramid of Djoser

The Step Pyramid of Djoser marks an important step in the development of the pyramid-shaped royal tomb. The complex was designed by the famous royal architect Imhotep, who would later become deified in ancient Egypt. You can see a bronze statue of Imhotep in Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt. A 14-year long restoration project at the site was just completed in 2020 which included strengthening the overall integrity of the structure by filling in gaps in its six rectangular mastabas as well work on the interior burial chamber and passages of the pyramid.

Check out some pictures from my visit to the Step Pyramid in 2011, early on in the restoration process, or, for a gallery of photos and more on the newly completed restoration, click here.

Views of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara showing the scaffolding used for the restoration project (photos by author).

Old Kingdom Mastabas: Tombs of Kagemni and Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep

The Old Kingdom (ca. 2649-2150 BCE) mastabas at Saqqara are some of the most beautifully preserved and decorated tombs. Here are two of my favorites from my last visit. The tomb of Kagemni is the largest mastaba in the cemetery associated with the reign of the Sixth Dynasty king Teti (ca. 2323-2150 BCE). Kagemni was a Vizier, the highest position in the royal administration.

The tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhoptep, also known as the tomb of the two brothers, dates to the late Fifth Dynasty and contains a number of exceptional scenes that underscore the closeness of the two men, both of whom served as overseers of the royal manicurists. Archaeologists uncovered a number of blocks from the tomb’s entrance repurposed in the nearby causeway of the pyramid complex of the late Fifth Dynasty king Unas (ca. 2353-2323 BCE). Thanks to the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, you can now go on a virtual tour of the tomb!

Here you see the names of the two tomb owners, Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep on a stone doorway inside their tomb as well the exterior of the mastaba (photos by author).

Scenes depicting Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep inside their tomb (photos by author).

Images from the Tomb of Kagemni at Saqqara depicting the tomb owner himself, a parade of offering bearers bringing animals, plants, food, and other supplies to the deceased, and a scene taking place on the Nile where we get an underwater view of a crocodile eating a fish (photos by author).

Beni Hasan

Beni Hasan is a cemetery site located in Middle Egypt, near the modern city of Minya, that was important during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030-1640 BCE). During that time some of the most elite Egyptians were buried on the escarpment (desert cliff) with one of the most beautiful views of Nile Valley around! For more on excavations at Beni Hasan in the early 1900s visit the Griffith Institute and for a virtual tour of the tomb of Kheti at Beni Hasan visit the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Top: A row of tomb entrances in the cliff face at Beni Hasan (photo by author). Middle: Image of the Nomarch Khnumhotep II fishing and fowling in his tomb (photo by author). Bottom: View of the Nile Valley from the tombs at Beni Hasan (photo by author).

Karnak

Karnak temple complex is one of the largest religious sites in the world. The first temple at the site was built during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030-1640 BCE) and the complex grew in size and complexity over time. The main temple at Karnak is dedicated to the Egyptian god Amun-Re, but there are smaller temples dedicated to Mut, Khonsu, and others. See if you can spot the snoozing pups in the pics below!

There are a number of ongoing excavations at Karnak that you can explore to learn more about the site. Check out this amazing minicourse on the Karnak Mut Precinct available on YouTube with Dr. Betsy Bryan, Alexander Badawy Chair of Egyptian Art and Archaeology and Director of Johns Hopkins’ excavations at the Mut Precinct.

Approach to Karnak Temple and processional way lined with Ram-headed sphinxes for the god Amun-Re (photos by author).

Sleepy Karnak pups (photos by author).

Inside Karnak Temple: Festival Hall of Thutmose III, Obelisks, exit towards the Sacred Lake, columns in the Hypostyle Hall (photos by author).

Lisa Saladino Haney is Postdoctoral Assistant Curator of Egypt on the Nile at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aisling McCrea, A message to an unknown reader…, Current Affairs (July 30, 2019)

I want you to picture the following scenario: You are an archaeologist, and you are digging at a site about 125 miles east of Karachi, Pakistan. A lot of the terrain in Pakistan is mountainous, difficult to inhabit, but not the part of the land we’re talking about. Check a satellite image of the region on Google Maps, if you’ve got a phone or a computer nearby: You are in that rich green ribbon of land that snakes down through the middle of the country. This is the Indus river basin, a place that has fed and raised cultures for thousands of years. Humans have wandered everywhere, but it was places like this, with running water and fertile soil, that first lured us into the role of settler. It was places like this where the combination of bountiful resources and our growing ingenuity first allowed us to develop systemic methods of agriculture, build cities, and begin our struggle to achieve things beyond mere survival, or so it is said. Because of this, river basins are nicknamed “the cradle of civilization.” Civilization is what we call it when humans begin to think of themselves not as dependents of their environment, but as masters.

From the distance of the satellite, note that you cannot see Pakistan’s cities or factories, or any sign of activity from the 200 million people living within the lines we call its borders. All that stands out to your eye is that luscious green ribbon, swirling from the mountains to the sea, a gift from God or the earth or whomever you believe to be the benefactor. You are an archaeologist, and this is where you are digging.

The site you are excavating was only recently discovered, a chance find by a construction crew. There are many sites in the region, all dating back to the Bronze Age, but we cannot discern the exact relationship between the settlements we’ve found, whether they considered themselves part of the same culture or were sworn enemies; part of the reason we do not know this is we cannot read their writing. Therefore, what you find in your excavation might be similar to other settlements in the region—simply an extension of the discoveries made before—or you might find something different. You are full of human curiosity, and ambition. You are hoping to find something different.

Here in the cradle of civilization, you find something buried. It is a bronze box covered in engravings, clearly designed by a skilled hand, and since you found it at the center of what appeared to be the site’s biggest temple, you judge it to be of some importance. You know the field well, and you know that this is unlike anything found before, and that excites you. The engraving contains a lot of symbols—part of the script no-one can read, it tells you nothing—and under the symbols, artfully etched, is the unmistakable image of a human skull.

For thousands of years and across continents, skulls have been used to signify danger. But history is long and full of turns, and even this most obvious and literal symbol could signify a multitude of things. You trace the skull with your finger, trying to connect with the intent of its long-dead creator. It seems designed to look intimidating, but when you first brushed the dirt from the surface and saw the graven image, you didn’t think for one second about danger—in fact, the first thing it reminded you of was the skulls on your brother’s goofy band shirts. (It wouldn’t make sense to think of danger. Whatever once threatened here is quiet. There is no danger here.) What could this skull have meant, you wonder, to the people who lived here? What’s the connection to the building, or the contents of the box? You think of human sacrifices, burial places, commemorations of wars.

Then you think of your career. You open the box.

In the 1960s, the U.S. Department of Energy began wondering what on earth it was going to do with all its nuclear waste. This question had never been highly prioritized before; in the years following World War II, the prevailing attitudes towards nuclear energy had run the gamut between sunny optimism and mortal fear, powerful emotions which leave little space for mundane concerns about the high-tech equivalent of garbage disposal. After research into nuclear fission had successfully served its first purpose—vaporizing and mutilating countless Japanese civilians—the U.S. government had been enthusiastic about the many potential uses of its superhuman creation, and invested heavily both in nuclear weapons and nuclear energy production for civilian use. It was predicted that nuclear power could do everything, from keeping the lights on to preserving food. A nation drunk on the promises of the atom had little interest in thinking about the hangover.

By the 1960s, however, the novelty of the so-called “atomic age” was starting to wear off, and the government realized it had a problem on its hands. The production of nuclear energy was creating large amounts of radioactive waste, which could not be converted into safe material, and which would remain dangerous to human beings for at least 10,000 years. (10,000 years is a conservative estimate. Many scientists have suggested that number should have one or two more zeroes on the end.) The waste was being kept in temporary storage facilities dotted around the country, and there was no obvious place where it could be safely deposited and sealed away. And even if a permanent place could be found, there was the question of how to keep people away from it.

The government’s concern was not so much for its contemporary citizens, who had been bombarded with enough Cold War propaganda to understand the threat of nuclear radiation. If a 20th-century American were to somehow get lost on their way home from the drive-in theater and stumble into a radioactive waste disposal site, all it would take to warn them off was a sign bearing the word “danger” and the image of the trefoil. (The trefoil is the internationally-recognized symbol for radiation, usually black on a yellow background, a circle surrounded by three blades. You knew the image before you knew the word.) Rather, the government’s concern was for the people who would come later. For comparison, the entire concept of complex human civilization, at least as we tend to define it, is about 5,000 years old. Now we had created something that would curse us for at least twice as long as that, maybe many times longer, and we had to work out not only how to bury it, but to protect whoever might disturb its burial place.

While Americans fretted over whether their grandchildren would grow up speaking English or Russian, the Department of Energy recognized that whoever came across their disposal site might be as distant to both those languages as we are to the dead scripts of the Indus valley. It was possible that they might not know written language at all. Perhaps they would have progressed so far beyond writing that the concept would be unthinkably primitive to them. Perhaps the opposite would happen, and they wouldn’t know anything of writing because the sum of human knowledge was lost to them in some catastrophic event—or even deliberately discarded, after the sum of human knowledge was examined and found, on the whole, not to have done us any good. No matter how desperately we wish to communicate with future peoples, there is no way to guarantee the sanctity of the written word, and it is considered likely that any written warning will be meaningless to them.

Communication through images seems an obvious choice—that’s the option we usually go for when we’re facing a language barrier—until you consider that the reader might have no concept of radiation. Right now the meaning of the trefoil is recognized across nations and languages, but that meaning is just an arbitrary one that we’ve constructed for ourselves, as fragile and temporally dependent as nations and languages themselves. To us, the sight of the trefoil signifies generations of scientific progress, terror, the future, something to be respected; an invisible energy that is sometimes used to kill hostile growths in our bodies, and in other cases will make them grow. None of that knowledge is communicated through the image. To our unknown recipient, it’s just a black circle and three blades. If you forget what it means to you, it could almost be a flower.

**

If one were looking for a hint at how these sites might be treated by our distant descendants, one might find it in the deserts of Egypt. Of all the myriad civilizations that ever lived and died in the “non-Western” world, Ancient Egypt is the only one most Westerners know much about, and there are two obvious reasons for this. First, Egypt’s exoticism and long history was a great source of fascination for the Greeks and the Romans—remember that the Great Sphinx was older to Caesar than Caesar is to us—and so it has somehow been pulled into Western canon, despite its location right in the middle of the region we are supposed to think of as the West’s eternal enemy. (This view is incorrect for many reasons, not least because nothing human is eternal.) Second, they left us the pyramids. The pyramids of Giza are not the world’s largest pyramids, nor the oldest, but for the last 4,500 years their image has captivated humanity across millennia and continents like nothing else on the planet. We cannot know the intent of the pharaohs, but one might guess they wanted to be buried somewhere that would assure they would always be remembered; by imprinting their deaths physically and unforgettably on the landscape, they were sending a message to future generations.

However, while the pyramids are still here, the meaning of the message is forgotten. Most people couldn’t tell you much about any individual pharaoh buried there. Almost no-one still believes that the pharaohs were gods. Some will want to tell you their own interpretation of the intended meaning or purpose of the buildings, or their theories about the culture in general; what was once a tomb for the world’s most influential figures is now reduced to a sort of personal amusement for amateur detectives. The burial chambers have been looted countless times. We unsealed the coffins and desecrated the dead, shipping them out to museums on new landmasses and displaying their bodies as curiosities, and no rumors of a curse could slake our thirst for trophies.

Very occasionally, we have a moment of vulnerability, of self-reflection. When it was announced last year that a new sarcophagus had been uncovered, and that it was filled with a mysterious red liquid, many responded to the news with expressions of dread. Was it because we still had a little lingering respect for a culture that had achieved so much, a culture that had not quite revealed all its mysteries to us, and its production of an as-yet unknown substance filled us with awe? Were we afraid that our knowledge of science had missed something old, and abhorrent, something lurking under the sands waiting to be set free?

The moment didn’t last long. A representative of Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities pointed out the liquid was most likely just sewage, and our discomfort promptly evaporated. Someone even started a petition demanding people be allowed to drink the “sarcophagus juice” so that they could “assume its powers.” A joke, of course, but jokes often contain a grain of truth. Across the entirety of our history as builders of civilizations, all our sins and achievements have stemmed from our metaphorical urge to drink the sarcophagus juice: to salivate at the promise of new knowledge and power, to disturb and break open anything that is unknown, to ransack the earth and, giving no thought to the consequences, consume whatever we find there.

***

By 1980, “atomic optimism” was dead, or at least dormant, in the United States. Throughout the 1970s, the anti-nuclear movement had gained momentum, along with the rest of the counterculture. A partial meltdown had just occurred at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania, stoking further panic about the dangers of radiation. There was still no confirmed plan to build a permanent waste disposal site.

The Department of Energy knew it was time to face some difficult questions. They assembled a team of experts from fields as diverse as environmental science, nuclear engineering, waste management, semiotics, linguistics, behavioral psychology and anthropology. They called it the Human Interference Task Force, and their goal was to develop a strategy to prevent any future nuclear waste depository from being disturbed by future generations. Although there was technology available to design a well-protected depository, the Task Force knew that there was little hope of building something totally indestructible. They could try and discourage interference with the depository by drawing on the concept of “hostile architecture”—designing a site that was deliberately difficult and uncomfortable to navigate—but a species that insisted on going to the Moon was unlikely to be deterred by a few spikes or a maze. Therefore, the main focus of the Task Force was not fortification, but communication. We could not keep people out by force; we could only plead.

In 1982, the German Journal of Semiotics (Zeitschrift für Semiotik) posed the depository problem to its readers, who responded with admirable, if slightly over-optimistic levels of imagination. One suggested solution was the development of a new breed of domestic cats, whose fur would change color in reaction to high levels of radioactivity. The world’s governments could then promote the development of art and literature in which cats changing color were an oft-repeated symbol for danger; thus, when future generations came across depository sites and tried to settle there, their cats would change color and they would become frightened and leave. Another suggestion was an “atomic priesthood,” a group of people who vowed to live near the sites, and passed on the secrets of radiation from generation to generation, in mythologized and ritualized form if need be. A theme that crops up again and again with the depository problem is the need for the message to be distilled into something simple and accessible: Call it universal, if you like, or primitive if you prefer.

Stanisław Lem, one of the world’s foremost science fiction authors, proposed that botanists use genetic modification to encode information about nuclear waste into the DNA of flowers, which could be planted and nurtured near the site. Although he admitted it was risky to assume future peoples would know how to decode the DNA, there was a sort of logic to it. To take plants that grew spontaneously and manipulate them to our liking, breeding and growing them at our convenience so we could propagate our own species was, after all, civilization’s first trick. Perhaps it had some lasting power.

The Human Interference Task Force began to draw up designs. A multiplicity of images, symbols and words were proposed as part of the initial blueprints for the depository site, with the Task Force noting that any method of inscribing the messages at the site would have to outlast theft, weathering, and changes in climate. Because we could not predict any future civilizations’ level of knowledge, the danger would have to be communicated in a way that was comprehensible to any type of reader. There could be some complex, technical messages at the site, but in case they couldn’t be understood, there needed to be some simpler messages too, and repeated in a number of ways so the meaning was less likely to be misinterpreted.

A 1993 report by Sandia National Laboratories—charged by the Department of Energy with the task of researching nuclear safety—took this concept further, and proposed some specific messages that might work. Some of the images might include: A periodic table. A world map of all known waste sites. A diagram showing the precession of stars in the sky over tens of thousands of years, from which readers might calculate the date the depository was built. (The places where we build depositories tend to be far from human life, and therefore relatively free from air pollution; if you want a perfect view of the night sky, go to a nuclear silo and look up.) There was some measure of disagreement on what type of pictographs to use. Some researchers wanted to focus on more functional pictographs, while others gave more prominence to “human facial expressions (horror and sickness).” The messages would begin from the outside, becoming more complex as one got closer and closer to the center. The Sandia report gives a suggestion for one of the more complex written warnings at a location close to the center. It was more technical in substance, though still simple in style:

“This place is a burial place for radioactive wastes. We believe this place is not dangerous IF IT IS LEFT ALONE! We are going to tell you what lies underground, why you should not disturb this place, and what may happen if you do. By giving you this information, we want you to protect yourselves and future generations from the dangers of this waste. The waste is buried __ kilometers down in a salt layer. Salt was chosen because there is very little water in it…We found out that the worst things happen when people disturb the site. For example, drilling or digging through the site could connect the salt water below the radioactive waste with the water above the waste or with the surface…”

The message goes on at some length, giving explanations as to the chemistry involved, the nature of illnesses caused by radiation, and the structure of the building. The writing would be inscribed on the wall, complete with instructional pictures. (Today, this scenario might remind one of an escape room or a puzzle in a videogame, amusing simulations of mortal danger made real.)

The writing would not be enough, though. The report also noted that the site would need to convey in its physical form a feeling, something that would touch the basest instincts of a living being. The authors noted in words, as best they could, what that feeling was:

“ This place is not a place of honor… no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here… nothing valued is here. What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us.

The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours. The danger is to the body, and it can kill.

This place is a message… and part of a system of messages …pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.”

**

At the end of the Sandia report, the writers quote a poem. If you’re into poetry, you might be able to guess what it is, and maybe the lines have already whispered through your mind as you’ve been reading this article.

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert… near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings;

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Ozymandias by Percy Shelley was published on 11 January 1818, at the height of what was called “Egyptomania,” the burning obsession of Western aristocrats with finding and swallowing up all the treasures of the Nile. Shelley might have been inspired by the romance of the desert for his setting, but the underlying message of his poem—even the greatest empires fall and are forgotten—can also read as a warning to his own nation’s empire, to the new wave of philosophers and scientists, to anyone so caught up in the heady power of 19th-century Britain that they forgot they were only mortal. Just 10 days before the poem was published, his wife, Mary Shelley, published a work of her own, a novel about a scientist who creates a monster he cannot control.

Not many paid attention to the warnings. The allure of power—power from knowledge, from technology, from resources, from land—dominated the mindset of those who ran empires, and those who ran empires dominated the world.

The same year Frankenstein and Ozymandias were published, Egypt conquered the Arabian Peninsula. This was a critical victory, because it put the holy cities of Mecca and Medina back under the control of the Ottoman Empire, the great power to which Egypt was subordinate. The Empire had held the holy cities for centuries, yet inexplicably, for the previous 13 years, Mecca and Medina had been out of their grasp, having fallen into the hands of a small upstart tribe with their own version of Islam—an extremely strict and literalist doctrine that seemed totally at odds with the rest of the world’s tendency towards modernization. But the recapturing of the cities meant balance was restored to the world, after this strange temporary interlude. The upstart tribe with its fundamentalist religion was brutally crushed, its leaders executed, and all was in its rightful place. If one were to go back in time to 1818, and ask a well-read man about the civilizational struggles in Arabia, it is likely he would have thought a lot about the strong, old, Western-facing Ottoman Empire—which had changed the shape of the world and produced so much of interest—and very little, if at all, about a defeated family called the House of Saud.

But the path of human history isn’t a straight line, and we can’t see what lies ahead of us. 100 years later, in 1918, the world’s most brutal war ended and the Ottoman Empire turned to dust, leaving the House of Saud space to consolidate their power. In 1932 the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was born. One of the king’s first moves was to invite American geologists, engineers, and businessmen to plunge through the sand and drill holes into the earth, suspecting that the ground beneath their feet was hiding black and glistening treasure that could make them rich.

In 1938, the Americans found what they were looking for, and the House of Saud turned from an upstart tribe to transformers of the desert, with the wealth and power to do anything they wished. Western cities grew upwards and outwards, feeding off the oil under the surface of Saudi land. In 1984, an exiled Saudi national named Abdul Rahman Munif wrote a novel about the oil boom called Cities of Salt, and when asked the meaning of the name, explained that one day the glimmering Saudi cities would dissolve and be forgotten, like salt in water. All this happened within a fraction of human history, and the finest minds of the early 19th-century could never have foreseen it—just as they couldn’t have foreseen how our lust for oil would cause the temperatures to rise.

**

The Department of Energy still does not have a permanent depository site, but it’s had a location picked out since the 1980s: Yucca Mountain, Nevada, 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas. Yucca Mountain is just by the Nevada Test Site, where nuclear weapons have been tested off-and-on since 1951 (the last test was in 2012). In this desert, workers would build mock neighborhoods of picture-perfect brick houses, sit families of mannequins at the dinner table, and see what remained of them after the mushroom cloud had dispersed. (No highly esteemed deed is commemorated here. What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us.) The location was partly chosen because almost no one lives there now, though remnants of the gold and silver mining industries have left the sands strewn with ghost towns. A lot of the names around here tell stories: Gold Center, Eureka, Saline, Chloride City, Hells Gate. Occasionally, you’ll see an indigenous name.

The Sandia report said the depository should send the message: We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture. This raises the question of who the “we” is supposed to be. It could mean the contemporary world in general, if we wanted to label ourselves one culture (we don’t know how apparent any differences would be to future readers between the United States and anywhere else.) Or it could mean the United States government. But there’s another “we” with a claim to this land. As far as the Western Shoshone people are concerned, Yucca Mountain doesn’t even belong to the federal government. The government claims to have legally purchased the land during the Civil War, when they needed it to acquire gold. The Western Shoshone dispute that the government has rights to the land, since the government only made a fraction of promised payment after it was appropriated. (This is not a place of honor.) Shoshone activists, as well as other peoples indigenous to the area, express their outrage both at the theft of their land and the polluting of the environment, but it does little good.

At any given point in time, some civilizations have power, and some do not. At the moment, the United States has power and the Shoshone do not, because in the European settlers’ quest to take the land, they had killed the majority of the people who were already there, wiping entire societies off the map as they went, whether intentionally by murder and cruelty, or unintentionally, by disease. (The danger is to the body, and it can kill.)

The Yucca Mountain plan is currently at a standstill, lacking in funding and lurking low on the priorities list, and for the moment, the permanent site shows no signs of being built. In its place, waste is temporarily being stored at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico, which one day might become the permanent site. If the site there is developed for permanent storage, its written warnings are to be in seven languages: the six official languages of the UN, and Navajo. One might interpret this as the federal government throwing a tiny token to the people it knows it has mistreated. Or one might consider it a recognition of the impossibility of predicting history’s twists and turns: We have no idea who might be here 10,000 years from now, and who might not.

**

When reading through the Human Interference Task Force and WIPP documents—after overcoming the initial wave of eldritch horror brought on by the sight of chapter headings like “Menacing Earthworks” and “Forbidding Blocks”— one starts to get the sense that something is unusual about these reports. For starters, the sheer level of vision on display is quite remarkable, making them at times seem more like science fiction novels than a government report. What’s more, from the perspective of our era—when the humanities and social sciences are frequently defunded, dismissed, and derided—it’s surprising to see an unquestioned faith in the essential relationship between “hard” science and social science. The U.S. Department of Energy understood that the nuclear waste disposal problem could not be solved by technological innovation alone; no alloy or neat little locking mechanism would save us from our future selves. Only by examining human nature, and allowing ourselves to conceive of a world beyond all contemporary understanding, could we attempt to protect the planet from the magnitude of what we’d done to it.

Perhaps, damaging though it was in terms of its siege mentality, there was something in the Cold War mindset that allowed the U.S. researchers to think in such epochal terms. The older researchers on the initial project would have grown up in the midst of the Second World War, the near-apocalyptic battle between inextricably opposed ideologies—fascism, communism, liberal democracy—that had all still been in their cradle just a century before, and had then grown into giants, who in their battles spilled blood into the earth and left cities in shreds. The younger researchers were bathed in the spirit of the Cold War, a Manichean atmosphere wherein the fate of the earth depended on the outcome of a constant struggle between two opposing forces, and where children learned that at the press of a button in Moscow, they might one day simply evaporate. This ingrained knowledge of the knife-edge fragility of civilization, a sense of an America proud and strong and wealthy and yet always teetering at the edge of a precipice, might have instilled in those researchers a quiet understanding that they, their hometown, their country, their planet was a place where all could be annihilated. Perhaps this enabled them to look calmly in the face of their own civilization’s destruction, and accept their obligation to do whatever they could for those who came next.

After the early ’90s, reports continued to come out, occasionally, but there were no big breakthroughs in the communication side of things, or any more radical approaches to the problem. This period, after the fall of the Soviet Union, is what Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history”: the epic battles between visions for humanity’s future were done, the West had won, we were all to put our imaginations away in safety deposit boxes and get to focusing on technocratic tweaks and institutional tune-ups for the rest of time. It is remarkable to note the difference in attitude toward the nuclear crisis in the Cold War, and the climate crisis today. Moderate proposals for a Green New Deal are hand-waved away as “unrealistic”; in response to suggestions of a move to renewable energy, sensible people shake their heads and point to their graphs of electricity prices, jobs, and GDP, graphs that stretch back 20 or 30 years, which is as far back as anyone can remember. Quietly, without fuss, long-term survival slips further and further down the priorities list.

The United States understands danger in the form of external threats, but not the danger within itself: the desire of civilizations to consume the land they perch on, to draw resources out from the ground and use them all up, to create great pestilences as a byproduct of its inventions, and realize (too late) the ramifications of what’s been done. There is something different between the inventive, enthusiastic way the U.S. Department of Energy reacted to the nuclear waste problem in the 1980s, and the timid, bounded way it reacts to climate change now. We have lost the ability to imagine the future.

Our nuclear waste sits in silos, waiting for a home; the question of what to do with them is in stasis. The Department of Energy has ensured that on a technical level, when they are eventually buried, they will survive any war or terrorist attack within the short-term—which, no matter how painful they might be to us, are bound to be mere scratches on the surface of the earth’s history. Wherever their resting place—as the situation stands, it will be somewhere quiet in the Southwestern deserts—when they are buried we will probably hear about them on the news, and there may be a wave of excitement, and then the dirt will be shoveled over them, and we’ll forget. A thousand crises will come and pass. Nations will be formed and abandoned, the sea will sweep in, the deserts will get hotter, the riverbeds will dry up. To think about a time 10,000 years from now is frightening, and bleak, knowing what we know about the current trends, but a stretch of time that long has room for faith as well as despair. Hopefully humanity will save itself, somehow; we will turn our desire to shape the earth to a good purpose, and build a new way of existing on the land, something none of us can predict. We can only pray that they will not be as greedy as us. We can only hope they hear our message.

**

Somewhere beyond any distance we can picture, an archaeologist is digging. The sand stretches all around him, to all horizons. He has hit stone, a monument to something, and after some time, it is revealed in its entirety. It it etched all over with lines of different shapes, that he cannot understand, but he understands enough to realize this was once a special place. To either side of the words, he recognizes drawings of human faces: one has a mouth open in terror, the other twisted in pain. This could be a memorial to some horrific event, or it could be a curse meant to punish unwanted intruders. Intruders were not well-liked by these people, or so the archaeologist has read, though he finds it difficult to understand their concepts of property and trespass.

Exhausted from digging, he sits at the foot of the monument, and he spends a moment taking in its magnificence, trying to connect with its makers. At the top of the monolith is a mysterious symbol—a circle, surrounded by three blades. The archaeologist smiles. He has never seen it before, but it fills him with a sense of serenity. It was a plant that grew in their time, perhaps, or the insignia of a nation, or a representation of a god. Whatever it was, it’s long gone now, but in any case it’s pretty. Like a child, he traces the trefoil in the sand, digging his thumb into the earth to make the center, dragging his fingers outwards one, two, three times. The ground moves easily for him, giving way to his desire to destroy the surface and create something new. He looks down at the trefoil he has drawn, his little sign that he has been here. He is just the latest in an immeasurable line of human beings who desire to put some sort of mark on the earth.

He is proud of his creation, but he forgets that it is drawn in sand. It’s visible only for a minute, before the winds blow it away.

25 notes

·

View notes