#Alf Henrikson

Photo

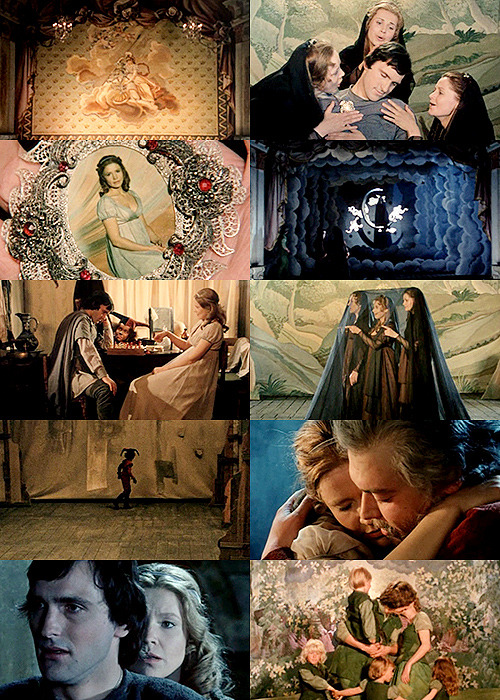

The Magic Flute (Ingmar Bergman, 1975)

Cast: Josef Köstlinger, Irma Urrila, Håkan Hagegård, Ulrik Cold, Birgit Nordin, Ragnar Ulfung, Britt-Marie Aruhn, Kirsten Vaupel, Birgitta Smiding, Erik Sædén. Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman, based on an opera by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder translated by Alf Henrikson. Cinematography: Sven Nykvist. Produ. tion design: Henny Noremark. Film editing: Siv Lundgren. Costume design: Karin Erskine, Henny Noremark.

For me, Ingmar Bergman's The Magic Flute is a kind of linguistic palimpsest, with the English subtitles* superimposed on the Swedish translation of the German original. Not that I know Swedish, but I've picked up enough of the sound of the language from watching movies that I can recognize a word or two. And I do know the German libretto fairly well from following along on recordings, so that when a singer begins a familiar aria, I hear the German in my mind's ear along with the Swedish being sung and then refracted through the words on screen. You'd think this would be distracting, but it isn't -- in fact, it only helps me appreciate the care Bergman took in making the film. Opera is not designed for the movies: It has moments of tightly choreographed action after which people stand still to sing, and you want more out of a movie than starts and stops. But what Bergman does so brilliantly is to supply close-ups and cuts that give the film an energy, often following the rhythms of Mozart's music. We don't get close-ups in the opera house -- thank god, because singing opera does unfortunate things to the singers' faces -- but Bergman has wisely chosen good-looking singers and had them speak-sing along with a previously recorded version, so there's little facial distortion. The Magic Flute is a problematic opera: Emanuel Schikaneder's libretto is a mess that never quite resolves the relationship between Sarastro, the Queen of the Night, and Pamina. Bergman solves this by creating one: In his version, Pamina (Irma Urrila) is the daughter of Sarastro (Ulrik Cold) and the Queen (Birgit Nordin), and he has abducted the girl because he doesn't trust his ex to raise her right. There's no justification for this in Schikaneder's text, and even Bergman hasn't quite resolved the problem of why Sarastro lets Pamina be guarded by Monastatos (Ragnar Ulfung), whose chief aim seems to be to sleep with the young woman. Nor has Bergman solved the misogyny and racism of Schikaneder's libretto. Women come in for a good deal of disapproval in the opera, and Bergman hasn't eliminated that. Monastatos is tormented by the fact that he's black -- a Moor -- although he is given a kind of Shylockian moment of self-justification, and even Papageno (Håkan Hagegård), who is the pragmatic, commonsense type, reflects that there are black birds, so why not black people. (I'm not entirely sure that line of Papageno's even makes it into the Bergman film.) Most productions today gloss over these antique prejudices as best they can, however, turning The Magic Flute into a kind of fairy tale for the kids, with colorful sets and cute forest animals dancing to Tamino's flute. Bergman is no exception in this regard: The film is set in the theater, and he opens with a close-up of a lovely young girl** with a kind of Mona Lisa smile, and follows her eye line as she gazes at the images painted on the curtain, then scans the other faces in the audience, old and young and of various ethnicities. The film, which like his other childhood-centered classic, Fanny and Alexander (1982), was made originally for television, is certainly one of Bergman's warmest.

*I don't know who did the English version, but it's a very good singing translation, not just a literal prose version of the original.

**She has been identified as Helene Friberg, who had bit parts in other Bergman films.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Egil Skallagrimsson is certainly no chivalrous and cheerful fairy tale hero. His sense of right and wrong is strong but peculiar. On a viking trail going east he at one point enters a farm in Courland, ties up the servants and ransacks the house, but on his way out he feels guilty, because taking things without the owner's knowledge is theft, and a despicable deed. Hence he returns, burns down the farm, and kills the people who come running out. Thereby he considers his righteousness restored.

Alf Henrikson, “Isländsk historia” (Icelandic History)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Magic Flute (1975). A production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera "The Magic Flute" is presented, this film which blurs the lines of it as a stage production - not only with aspects of the theater stage shown, but also the occasional shot of the audience members watching it, and the performers going through their backstage routines during intermission - and a movie as the set moves out from the confines of the stage.

Ingmar Bergman has such an incredible sense of depicting physical intimacy that it’s hard not to be caught up in his work. The way he captures faces, touches, closeness is pretty much perfect, and there are some great sequences in this particular film demonstrating that. As a movie though, this one’s pretty faithful to an opera I’m not super into, haha, and the film really is at it’s best when it bends the rules of recorded theatre. 7/10.

#the magic flute#1975#Oscars 48#Nom: Costume#Ingmar Bergman#Emanuel Schikaneder#Alf Henrikson#Josef Köstlinger#Irma Urrila#mozart#sweden#swedish#fantasy#opera#7/10

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alf Henrikson & Edward Lindahl: Asken Yggdrasil: En gammal gudomlig historia (1973)

0 notes

Photo

The Strongest (1929)

My rating: 4/10

Oof, animals were definitely harmed in the making of this movie. Also included: Some nice location shots, bad slapstick, a love triangle that must've been trite even back then, and Grandma angrily knitting in the corner and easily being the best part of the whole movie.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Anders Henrikson as Ole in Den starkaste: En berättelse från Ishavet (The Strongest: A Story from the Arctic Ocean) 1929. Directed by Alf Sjöberg and Axel Lindblom

Anders Henrikson on Pinterest

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(295/365) Vägen genom A (The Road Through A), steel statue by Thomas Qvarsebo, at Esplanaden/Alf Henriksonplatsen in Huskvarna, from another angle. The quote says: Dagen idag är en märkvärdig sak, tänk, evighet fram och evighet bak. (The day that is today is a remarkable thing, imagine, an eternity ahead and an eternity behind.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

So here’s the first time a country sent a song that was completely in a non-national language, and naturally the EBU shut that nonsense down with the language rule the following year.

Also, welcome to opera as a musical style!

#esc#eurovision song contest#year: 1965#draw: 10#performer: Ingvar Wixell#place: 10#country: sweden#language: english#points: 6#voting: 5-3-1 scoring#composer: Dag Wirén#lyricist: Alf Henrikson#returning nation

0 notes

Photo

NOTE: Despite the fact The Magic Flute was originally released on Swedish television on January 1, 1975, it debuted as a theatrical film in the United States later that year in November. As per the rules I set out for this blog, Bergman’s The Magic Flute will be treated as a theatrical film.

The Magic Flute (1975, Sweden)

I imagine that when some people read that this film review concerns an adaptation of an opera, they will stop reading at the word, “opera”. As someone who was taught classical music from an early age, I get it. Opera seems inaccessible, and a several-minute aria just to get a plot point across can seem daunting (not just for the audience, but the performer too). But as with any artistic medium, there will always be points of entry for newcomers. Ingmar Bergman’s 1975 adaptation of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute is one of them. The Magic Flute is one of the more accessible and most performed operas in Western classical music, and it just so happened to be Ingmar Bergman’s favorite. Bergman saw the opera when he was twelve years old, leaving an immediate impression. Unable to afford the record, he attempted to recreate The Magic Flute with marionettes at home. By the mid-1970s and having cinematic and stage production experience in his oeuvre, Bergman dared to imagine filming his favorite opera.

There are numerous cinematic opera adaptations. But they are underseen and largely unavailable to North American viewers – I am not including filmed opera performances in this distinction (e.g. the Metropolitan Opera’s popular live feeds that are presented in movie theaters and public television). Invariably, Bergman’s The Magic Flute is mentioned on the rare occasions when opera films are discussed. Sometimes, due to contempt for opera or a lack of understanding about classical music, it is the only such opera film discussed, and usually never from a musical lens.

In this adaptation, Bergman attempts to meld the distinct artifices of cinema and opera together. The viewer is never transported to a fantastical world, as the film possesses no “fourth wall” to begin with. We see an audience – look closely and you will see Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist in the audience – waiting in anticipation during the overture, and the action takes place on what appears to be a homely community opera house. On occasion, we will see the performers backstage preparing for their musical entrances. When their performance begins, they inhabit the world of the opera.

This peculiar dynamic Bergman creates is less believable on a more gargantuan stage. The stage’s production design and deliberately low-budget (but charming) costume design suggests we are experiencing a performance given by a small community opera company. La Scala this is not, nor is it the Met or Paris Opera. Bergman wished to shoot the film at the Drottningholm Palace Theatre in Stockholm, a small eighteenth-century theater that still uses mechanisms dating back to its inception. Unfortunately, that theater was deemed too fragile for film equipment. Nevertheless, Bergman and production designer Henny Noremark (who also served as co-costume designer along with Karin Erskine) concocted a workaround. On a soundstage at the Swedish Film Institute, the production design team painstakingly crafted a facsimile of the Drottningholm Palace Theatre’s interior. The Magic Flute appears to be an inexpensive production, but it is anything but. The stage is intimate, inviting, personable.

In brief, Mozart’s opera is set in Egypt and concerns a mother-daughter dispute rife with misunderstanding. The protagonist, Prince Tamino (Josef Köstlinger), is contacted by the Queen of the Night (Birgit Nordin). She asks him to free her daughter Pamina (Irma Urrila) from the clutches of a high priest named Sarastro (Ulrik Cold; doesn’t that sound like a villainous name?). After being shown a portrait of Pamina, Tamino falls instantly in love with her – that’s opera logic, you know. Tamino is joined in his adventures by Papageno (Håkan Hagegård), an overly talkative bird-catcher dressed like a bird. But Tamino will learn more about Sarastro’s priestly order and becomes interested in joining. The Magic Flute has been interpreted as heavily influenced by Masonic themes, and modern analyses clash as to whether its portrayal of the Queen of the Night is misogynistic (see: Sarastro’s belief that Pamina should not be subject to the Queen’s feminine manipulations) or proto-feminist.

Also featured are the conniving Monostatos (Ragnar Ulfung) and, in the second act, Papagena (Elisabeth Erikson). The Magic Flute benefits from an excellent recording by the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under the direction of conductor Eric Ericson.

Opera films tend to adhere closely to the work composer and librettist. Bergman exercises some liberties with Mozart’s music and Emanuel Schikaneder’s libretto*. Instead of the original German, this film uses a Swedish-language libretto by the poet Alf Henrikson (this Swedish-language version debuted at the Royal Swedish Opera in 1968). No offense against the Swedish language, but this Swedish-language version of The Magic Flute makes the musical phrasing awkward. Mozart’s opera was composed with German in mind. German may not be a listenable as Italian in an operatic setting (it could be worse, it could be English – as in the otherwise excellent 1951′s The Tales of Hoffman, adapted from Jacques Offenbach’s opera of the same name), but this should have been Bergman’s first choice.

The decision to cast singers with sweeter voices rather than full, unamplified ones assumes that an audience cannot tolerate a soprano’s high notes. "Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen" – commonly known as the Queen of the Night aria – demands full-bodied womanly rage to sing. The soprano should sing this forcefully, but not harshly. It feels like Bergman is asking Birgit Nordin to hold back her vocals during the aria (which also sounds rushed in the second half). Whether in an opera or an operatic adaptation for film, this is not an aria that should be sung with anything less than full power. Bergman should let Nordin sing this aria as it should be sung. To do so invites a starker contrast between those few minutes and the rest of the film – a show-stopper as Mozart intended it to be. Nevertheless, Bergman’s decision to prioritize acting over musicality – however it grates upon my senses – works for all the other roles. Nykvist’s cinematography pulls close to the actors’ faces, demanding more facial acting from the cast (who are all lip-syncing) than they might be used to. The cast succeeds in this challenge, approaching a type of acting they are unaccustomed to.

The setting of Bergman’s Magic Flute strips away much of the opera’s original Egyptian setting and settles for a vaguely European design. The Queen of the Night-Sarastro conflict becomes a parental dispute, as Bergman makes Sarastro Pamina’s father. A few trios in Act II have been eliminated. Also in Act II and to the film’s detriment, Bergman changes the order of appearance of two Papageno-centric scenes to the point where they no longer make any narrative sense.

Where Bergman’s The Magic Flute triumphs is its representation of the nature of live opera (and, by extension, live theater). When one experiences an opera or theater, everything onstage is an interpretation, a living fiction. The events onstage and the music transport one from reality, without ever truly leaving that reality. Moments in which Swedish text of the libretto appears in front of the actors (sometimes held by the actors themselves) precede the creation and widespread use of surtitles in opera houses today. By making somewhat indistinguishable the actors’ transition between the “real” and operatic worlds (during the intermission’s last moments, we see actors smoke a cigarette and two others playing chess), Bergman shows that the viewer is as much a part of the performance. We assign as much meaning to the unreality of an opera as the actors. The whimsical comedy of The Magic Flute – one filled with imperfect protagonists and subplots that never quite cohere – makes Bergman’s metatextual commentary more apparent and approachable.

The Magic Flute followed two heavy Bergman dramas in Cries and Whispers (1972) and Scenes from a Marriage (1973). Having watched twelve of his forty-five feature films, The Magic Flute is, by some distance, the liveliest Bergman film I have seen. I do not expect any others to be as light, as comedic as this – the key difference might be that Bergman is adapting material, rather than using an original screenplay of his. It is refreshing to see an Ingmar Bergman without a gripping existential crisis, mentally disturbed characters soliloquizing their plights.

In The Magic Flute, the relationship between our lived reality and theatrical artifice holds for every person that engages with the performing arts. Debuting in Vienna in 1791, The Magic Flute, Mozart’s final opera, was not composed for aristocratic patrons, but commoners. Almost two centuries later, the in-film audience of Bergman’s adaptation is comprised of various genders and races. That universality of the theatrical experience is reflected in their faces, interspersed on occasion alongside scene changes and still moments. The universality of Western classical music, in this case Mozart’s, is etched in their gazes. Nykvist’s camera keeps returning to one young girl in particular. She is always smiling, obviously enchanted by The Magic Flute. Perhaps she is feeling things akin to Bergman the first time he experienced The Magic Flute – unburdened by cynicism, more accepting of unreality.

My rating: 7.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

*A librettist is the opera term for a lyricist. The Magic Flute is a Singspiel opera, which means it contains snippets of dialogue. Schikaneder wrote both the lyrics and dialogue.

#The Magic Flute#Trollflöjten#Mozart#Ingmar Bergman#Josef Köstlinger#Håkan Hagegård#Birgit Nordin#Irma Urrila#Ragnar Ulfung#Ulrik Cold#Britt Marie Aruhn#Kirsten Vaupel#Birgitta Smiding#Elisabeth Erikson#Emanuel Schikaneder#Alf Henrikson#Sven Nykvist#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

1 note

·

View note

Note

1, 10, 15 for the identity ask thingy :D

1. if someone wanted to really understand you, what would they read, watch, and listen to?We could be here all day if I really wanted to answer this thoroughly, but I’ll try to be concise. I’ll limit myself to one of each - which, to be fair, doesn’t offer up a lot of understanding in the grand scheme of things. But I try. Read: His Dark MaterialsWatch: The Nightmare Before ChristmasListen to: The Lorry Gang’s Swedish audio book version of Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (see, I cheated a bit there, but I do things like this). 2. do you have a creed?I believe many different things about a great many other things. But if you allow me to be a tiny bit pretentious (and when am I not), I’ll offer up this Shakespeare quote (I did warn where this was going) that personally resonates with my view on life in general, and I suppose that’s why I’m pretty fond of it: “Love all, trust a few, do wrong to none.”It’s not for everyone, it’s certainly impossible, but it’s something I try to go by, at least as a starting point. 3. five most influential books over your lifetime.- Harry Potter by JK Rowling- His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman- The Book Thief by Markus Zusak- Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas Hofstadter- The Road Through A by Alf Henrikson (that’s my own translation of the Swedish book “Vägen genom A”, which I don’t think has any official English title.)(Special shoutout - because I can never stick to a list - to anything by Astrid Lindgren as well as Momo and The Neverending Story by Michael Ende.)

THANKS FOR ASKING :D

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(294/365) Vägen genom A (The Road Through A), steel statue by Thomas Qvarsebo, at Esplanaden/Alf Henriksonplatsen in Huskvarna. The statue celebrates Alf Henrikson, a writer from Huskvarna, and shares a title with one of his books.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anita Björk, Märta Dorff, and Ulf Palme in Miss Julie (Alf Sjöberg, 1951)

Cast: Anita Björk, Ulf Palme, Märta Dorff, Lissi Alandh, Anders Henrikson, Inga Gill, Åke Fridell, Kurt-Olof Sundström, Max von Sydow, Margarethe Krook, Åke Claesson, Inger Norberg, Jan Hagerman. Screenplay: Alf Sjöberg, based on a play by August Strindberg. Cinematography: Göran Strindberg. Art direction: Bibi Lindström. Film editing: Lennart Wallén. Music: Dag Wirén.

"Opening up" a play when it's made into a movie is standard practice. Directors don't want to get stuck in one or two sets for the entire film, so they shift some of a play's scenes to different locations or have new scenes written. But nobody has done it with such imagination and finesse as Alf Sjöberg, taking August Strindberg's Miss Julie out of the kitchen in which the play confines the characters and into the other rooms of the house and onto the grounds of the estate. Sjöberg plays fast and loose not only with space but also with time, giving us scenes from the childhood of some of the characters, showing us the cruelties that warped them into the twisted adults they have become. But he also does it by letting the characters from the past appear in the same room as their equivalents in the present, giving a sense of the indivisibility of past from present. Granted, Strindberg's play, with its long reminiscent speeches, facilitates this reworking of the drama by providing the material for Sjöberg's added scenes, but there's a fluidity to Sjöberg's melding of memories into the tormented present of Julie (Anita Björk) and Jean (Ulf Palme). There are some who argue that Miss Julie is meant to be a claustrophobic play, that dramatizing too much of Julie's relationship with her mother or Jean's early lessons in not transgressing the limits of class undermines the play's psychological realism with too much action and melodrama. The answer to this, I think, is that the play remains, and continues to be performed with success -- and, incidentally, to be filmed repeatedly in ways more faithful to Strindberg's original plan. What we have with Sjöberg's film based on Strindberg's play is a second creation, rather like Verdi's Otello and Falstaff, works that can stand on their own as masterpieces without denying the virtues of the Shakespeare plays on which they're based.

0 notes

Video

vimeo

TROLLFLÖJTEN. Göteborgs Stadsteater 2019

Av WA MOZARTBaserad på ALF HENRIKSONS ÖVERSÄTTNING AV EMANUEL SCHIKANEDERS LIBRETTO

Regi, bearbetning MELANIE MEDERLIND

Scenografi och kostym MAJA KALLL

Musikarrangemang TOMMY JONSSON

Med KAROLINA ANDERSSON, HANI ARRABI, THERESE ERCH, ERIC ERICSON, HANS-ERIK DYVIK HUSBY, CARINA M JOHANSSON, RAMTIN PARVANEHPraktikanter från Performing Arts School MATILDE HOLMSTRÖM ANDERSEN, DANIELLA HÖRSLYKKE, OSCAR LINDER, ARVID NYGRENKapellmästare, musiker SIMON LJUNGMAN, ERIK WEISSGLASKapellmästare, musikalisk instudering, musiker EMMA RUNEGÅRDMusikerPAULA HEDVALL, AXEL MÅRDSJÖ ljus CARINA PERSSON BACKMANLjud DANIEL JOHANSSONKoreograf LISA ALVGRIMDramaturg SISELA LINDBLOM

0 notes

Photo

#busstop #waitingforthebus #evening #commuting #buildings #skyandclouds (på/i Alf Henriksons Plats, Esplanaden, Huskvarna)

0 notes

Text

Use Your Own Language Day, part II

Fortsätter denna dag med fem dikter av Alf Henrikson, som siktade efter att roa och upplysa sina läsare snarare än Dikter Som Hög Kultur - och så lever många av hans alster fortfarande.

Människolott

Mannen från Hökarängen

suckade stilla och sa:

"Min fru äter skorpor i sängen.

Annars är allting bra."

Samma måne

Samma måne som lyser på tant

lyste på Platon, lyste på Kant,

lyste på Shakespeare och Dante,

lyste på Nero och Djingis Khan,

lyste på Shelley och Södergran,

innan den lyste på tante.

Samtal med datorer

Medan datorn och människan talas vid

flyger timmarna spårlöst bort.

Att sitta och prata med datorn tar tid.

Livet är kort.

Elektronerna dunsar sin kos utan spår

och livet går verkligen fort.

Datorn pratar och timmarna går

och inget blir gjort.

Verktygen

Aldrig blir hammaren omodern, eller tången och filen och sågen,

men en trettioårig skrivmaskin gör mig strax antikvarisk i hågen.

Den har hunnit bli löjlig och komisk, obsolet har den hunnit bli.

Inget är mera föråldrat än gårdagens sista skri.

Troende

Högfärdsblåsor utan like

tror att de ska få ärva Guds rike.

Inga ljusårs galaxer känns större än de.

Nåja, vi får väl se.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(294/365) Vägen genom A (The Road Through A), steel statue by Thomas Qvarsebo, at Esplanaden/Alf Henriksonplatsen in Huskvarna. The statue celebrates Alf Henrikson, a writer from Huskvarna, and shares a title with one of his books.

1 note

·

View note