#Archibald Motley Jr

Text

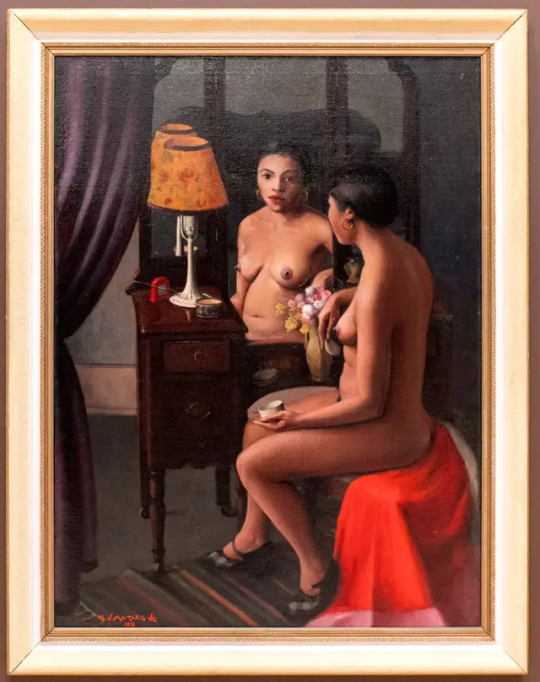

Archibald Motley Jr. , Saturday Night, 1935

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

While considered a contributor to the Harlem Renaissance, Archibald Motley Jr. never lived in Harlem and was in fact born in New Orleans. He lived in Louisiana until his family moved to Illinois, settling in Chicago's South Side.

A mixed race man, his experience living between black and white worlds made him keenly aware of the boundaries, privileges, and prejudices that came with race and skin tone.

His work, while beginning largely in portraiture, explored those realities, informed by his study of the Old Masters. His work also explores jazz culture with bright, colorful night scenes full of vivid figures in gleamingly city lights.

Motley's Life was complex and fascinating, if you'd like to see his work and learn more about him:

Whitney Museum of American Art - Archibald Motley

Motley Archibald Jr - Encyclopedia.com

Oral history interview with Archibald Motley 1979

#Black History Month#Black Art History#Art History#Archibald Motley Jr#Archibald Motley#Black Artist#Modernist#Mondernism#Art Deco#Painter#Modernist Painter#artdeco

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archibald J. Motley, Jr.., Blues, late 1920s. Oil on canvas.

Archibald Motley, Jr.’s painting captures the sights and sounds of a black-and-tan nightclub in the late ’20s, where patrons could be free from the strictures of white society. He painted this work while on a Guggenheim Fellowship in Paris but returned in 1930 to become a significant figure in the Harlem Renaissance and in the lively Chicago arts scene.

Photo & text: Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum

#vintage New York#1920s#Archibald Motley Jr.#Black painting#African-American painting#Harlem Renaissance#African-American art#black & tan#black & tan nightclub#painting

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archibald John Motley Jr. Tongues (Holy Rollers). 1929

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

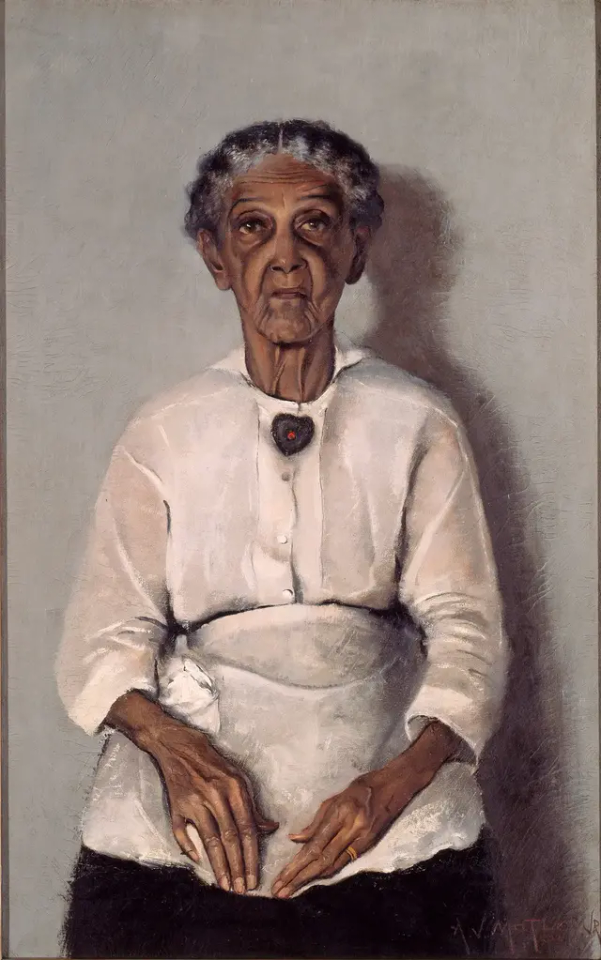

Portrait of My Grandmother (1922) by Archibald J. Motley Jr.

#Portrait of my Grandmother#1922#1920s#Archibald J. Motley Jr.#art#painting#portrait#portrait painting#Miss Cromwell

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

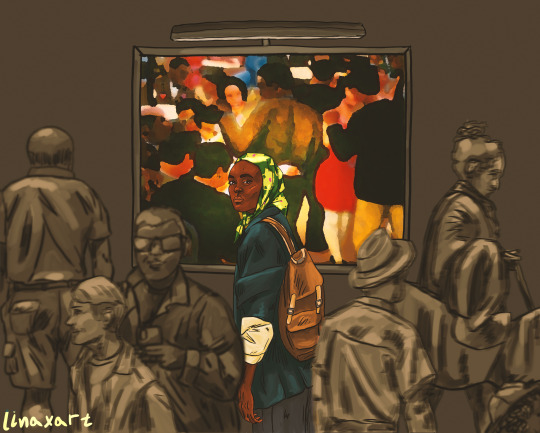

Incognito

with massive thanks to @goldheartedsky who had all the right ideas for this xxxx

#the old guard#nile freeman#tog#tog art#the old guard fanart#nile freeman fanart#nile tog#immortal family#digital art#fanart#sketchbook#Photoshop#accessible art#accessible fanart#artists on tumblr#so! Archibald J. Motley Jr. is a chicagoan black artist which goldie introduced me to#and I'd like to think nile art history freeman would have liked the opportunity to see his work in person#which is why she risked exposure to go to the museum

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archibald John Motley Jr. - The Octoroon Girl (1926)

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

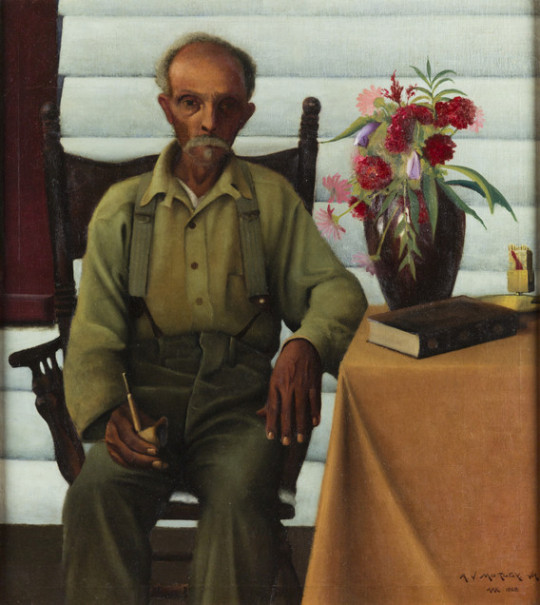

Uncle Bob. 1928, by Archibald John Motley Jr

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archibald J. Motley, Jr., Black Belt (1934)

Collection of the Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia © Estate of Archibald John Motley Jr. All reserved rights 2023 / Bridgeman Images

Image courtesy Hampton University

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archibald Motley Jr. Cocktails, 1926

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

Archibald John Motley, Jr., Tongues (Holy Rollers), 1929, Oil on canvas, 2/19/24 #moma by Sharon Mollerus

#Archibald John Motley#Tongues (Holy Rollers)#New York#1929#2/19/24 moma#Jr.#Oil on canvas#Museum of Modern Art#New York City#NY#flickr

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tongues (Holy Rollers)

Archibald John Motley Jr. 1929. Oil on canvas, 29 1/4 × 36 1/8" (74.3 × 91.8 cm). Bequest of Janice H. Levin (by exchange). © Archibald John Motley Jr.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Archibald John Motley Jr., Nightlife, 1943, oil/canvas (Art Institute, Chicago)

#archibald john motley#art#painting#american regionalism#modernism#african amerian artist#20th century

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Lesser-Known Modernism Inspired by African-American Culture

The Whitney Museum of American Art is presenting the career retrospective “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist,” which includes “Black Belt” (1934).Credit... Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia, Valerie Gerrard Browne

By Holland Cotter

Oct. 1, 2015

I don’t know how museums plot their seasons, but it was a good plan to have “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” be the first career retrospective to appear at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s new home. Motley is an important but still understudied figure. The show itself is neither large nor hot off-the-shelf. (It originated at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and has been traveling; this is the last stop.) But it has features that many bigger, sexier exhibitions lack: an affecting narrative, a distinctive atmosphere and a complicated political and moral tenor. It’s a tight, rich package. You take it away with you, complete.

And part of what you take away is an alternative version of the American modernism on which the Whitney is based. This other modernism developed outside of New York. It didn’t adopt abstraction as its defining advance style. It absorbed what was happening in Europe, but found its main power source in American culture, and specifically African-American culture. Archibald J. Motley Jr. — he used his full name professionally — was a primary player in this other tradition.

He was born in New Orleans in 1891 and three years later moved with his family to Chicago, which would become his permanent home. His African-born paternal grandmother, a former slave, came with them. There his father, a child of slaves, found work as a Pullman porter. His mother, of mixed racial descent, ran the house. When Motley’s teenage sister, Flossie, had a child, Willard, out of wedlock, the family raised him to believe that his mother and his uncle were his older siblings.

“Portrait of My Grandmother” (1922). Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

“Portrait of Mrs. A.J. Motley, Jr.,” from 1930. Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

Altogether, it was a household in which traditionally fixed categories of race and lineage were somewhat fluid. So was its relationship to class. The Motleys lived outside the so-called Black Belt of Chicago, the strictly demarcated African-American area also referred to as Bronzeville, on the city’s South Side. Their home was in a largely white immigrant neighborhood. Motley was one of the few black students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he received classical, European-based training as a painter. He married a white woman, Edith Granzo, his high school sweetheart.

Calibration of racial and social status by color is an underlying theme in the early portraits that open the exhibition, organized by Richard J. Powell, an art historian at Duke, and Carter E. Foster of the Whitney. Motley believed that information about the biology of race was important for both whites and blacks to have in the interest of mutual understanding.

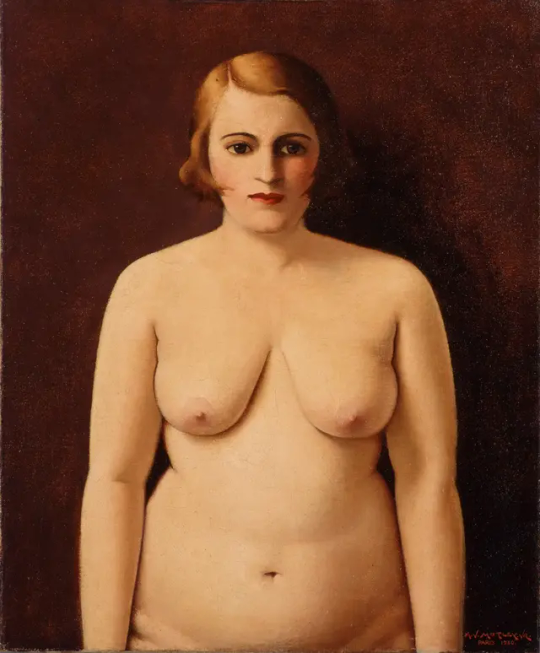

“Nude (Portrait of My Wife)" (1930). Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

“Brown Girl After the Bath” (1931). Credit... Emon Hassan for The New York Times

In a 1924 picture, a dark-skinned older women dressed in a gingham dress and head scarf is identified as “Mammy.” A painting done a year later of a lighter-skinned young woman in a chic flapper cap is titled “The Octoroon Girl,” using a term once applied to someone with one-eighth black ancestry. In a 1930 nude portrait, Motley’s wife stands erect, arms down, face forward, glowing gold, as if posed for an epidermal inspection. A year later, in a more relaxed painting called “Brown Girl After Bath,” the glow remains, but gold has been exchanged for copper.

These images surround Motley’s own 1933 “Self-Portrait (Myself at Work),” which, ethnically speaking, gives little away. Dressed in a smock and beret, the artist, who by then had spent a year in Paris, looks neither distinctly black nor white, just seriously Continental. A neo-Classical statuette stands on his worktable. A crucifix hangs on the wall. (Motley was a practicing Roman Catholic.) He holds a big palette in one hand and conjures a nude model, Pygmalion-style, with his brush. He was at this point already nearing the peak of his professional success. The historian and activist W. E. B. Du Bois had publicly called him “a credit to the race,” though there is little of an obvious race man in the image here.

“Self-Portrait (Myself at Work)" (1933). Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

This doesn’t mean that he kept himself at a remove from black popular culture. His deep but controlled immersion in it — wading in, stepping back — is what the exhibition as a whole is about. From an early age he had been a regular visitor to the Black Belt entertainment strip of jazz clubs, theaters, cafes and gambling joints known as the Stroll. And a section of the exhibition called “Nights in Bronzeville” is a record, in paintings, of his time spent there. If his portraits are an effort to capture and codify variations in racial appearance, his Bronzeville scenes, and their Paris equivalents, which he produced from the late 1920s onward, are attempts to find visual correlatives for the sounds of black music and colloquial black speech.

“Saturday Night,” from 1935, is a club scene. It takes what Motley learned about figure painting, color and composition, pushes that through an Expressionist filter, and sets it to a sinuous, thumping jazz score. The room is soaked in vermilion light. The band is far in the background, but its rhythms pulse through in the body of a single dancer who sways between the tables.

“Saturday Night” (1935).Credit...Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Valerie Gerrard Browne

“Carnival” (1937).Credit...Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Valerie Gerrard Browne

The same energy fills the night in “Carnival” from 1937, only now the music comes, outdoors, from an accordion-playing minstrel-show figure regaling a crowd of fairgoers. The smartly dressed visitors chat and preen. Stars shine overhead. A fat man in a straw skimmer, looking oddly isolated, moves through the center of the scene.

That man, or his equivalent, shows up in many of Motley’s city pictures. He’s an outrageous racial caricature: round-faced, popeyed, thick-lipped, a cartoon. Mr. Powell, in the catalog, pegs him as Motley’s alter ego, his way of acknowledging a feeling of distance from blackness but also an investment so thorough as to allow him to play with it, mess with it from the inside, as well as from the outside, pre-emptively expressing the racist hostility that is an unabating condition of American life. It’s a tactic used by writers like Zora Neale Hurston in Motley’s time, and in our own by comedians like Richard Pryor and artists like Robert Colescott and Kara Walker.

Motley continued to explore this risky mode of depicting social realities for the rest of his career which, gradually, went into decline. After his wife’s death in 1948, he made extended trips to Mexico, where his nephew Willard, a successful novelist, lived. Back in Chicago, to support his mother, who had remarried after his father’s death, he took a job with a company designing shower curtains. In 1955, he was jailed for six months for assaulting her abusive husband. In 1963, in his 70s, he began his last painting.

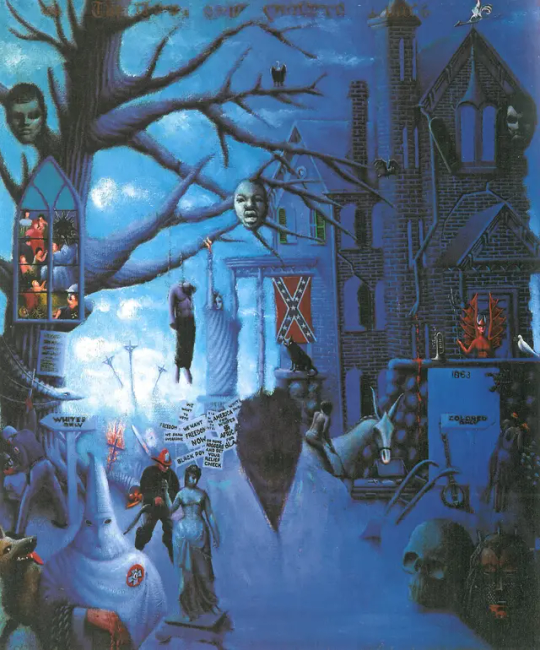

“The First One Hundred Years,” finished in 1972, was Archibald Motley’s final painting, and with its sweepingly topical content, it’s like no other picture he ever made. Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

With its epic-length title — “The First One Hundred Years: He Amongst You Who Is Without Sin Shall Cast the First Stone; Forgive Them Father for They Know Not What They Do” — and sweepingly topical content, it’s like no other picture he ever made. Set in a twilight blue space, it has the mood of a composite-style nightmare to which new elements were added over time: an African mask paired with a human skull; a devil’s head and a peace dove; a Ku Klux Klan figure and the Statue of Liberty, and a “coloreds only” sign; a lynching and a crucifixion. And dead center is a man’s head in the format of a bust-length portrait, with the face blacked out.

This painting, hung on a wall by itself, ends the show, just as Motley’s confident 1933 studio self-portrait began it. When he finished “The First One Hundred Years” in 1972, he put his brushes down and painted nothing more in the remaining nine years of his life. His work ends in profound political anger and in unambiguous identification with African-American history. I would say that, behind his gracious portraits and his later, radical, jazz-scored scenes of black urban life, those feelings were in some measure ever-present. They help explain his art’s unforgettably puzzling texture and its surprising weight.

“Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” runs through Jan. 17 at the Whitney Museum of American Art; 212-570-3600, whitney.org.

6 notes

·

View notes