#holland cotter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Most Wondrous Art in the World in 1,726 Objects

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Michael C. Rockefeller collection from Africa, the Ancient Americas and Oceania reopens with a pantheon of historic art stars.

In the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, a carved figure from Mali is the welcoming host.

This is a gift 🎁 link so there is no paywall. Below are some excerpts.

If you want to feel the charge of excitement that great art — no imaginative limits — and new thinking about it can bring, head to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s redesigned and reconceived Michael C. Rockefeller wing, and its collection of work from Africa, the Americas and Oceania that opens on Saturday. Go for the pure visual pleasure of the work there — believe me, it’ll have your eyes spinning — and go for the still unfolding histories it tells. [...] These 1,726 objects — majestic carved wood figures from Africa; pocket-size mythical beings, cast in gold, from Mexico; a communally painted, Sistine-worthy ceiling of the South Seas from New Guinea — are as beautiful as any art anywhere on this earth, and represent the spiritual, political and emotional lives of people spread over five continents and eight millenniums.

Surrounded and embraced by the creative power of Africa in the entry to the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, with clusters of work from many cultures.

The Arts of Africa

The main point of entry to the African collection is still from the Greek and Roman galleries, but now when we enter, under a high white ribbed-arch ceiling, we are in Africa, surrounded and embraced by it. In the center is a savanna of wood-carved sculptures, with enfilades of intimate exhibition spaces on either side and, leading off to the left, deep into the wing.

Vista of the Arts of the Ancient Americas, where venerable objects made of stone, metal and ceramic have been brought out into the light from Central Park.

The Arts of the Ancient Americas

The Art of the Americas display, with its primary entrance across from the museum’s Modern and Contemporary galleries, begins with some of the oldest objects in the collection. One is a near life-size Olmec head from Mexico cut from sea-green jade and dated from 900-400 B.C. Its features look human but also, with catlike eyes, not. Another is an extraordinary, fragmented ceramic figure made sometime between 200 B.C. and 400 A.D. in Colombia or Ecuador. It depicts an avidly energetic-looking super-ager — a shaman? — who seems to occupy nonbinary terrain between genders and species. (The figure’s spine resembles an iguana’s tail.)

The redesigned wing, by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture with Beyer, Blinder, Belle, features a Ceremonial House Ceiling by Kwoma artists, Papua New Guinea.

The Arts of Oceana

Meanwhile, the bulk of the museum’s Oceanic material has now been repositioned within the Rockefeller wing. Much can be found in a string of galleries that cuts diagonally across the wing, forming a kind of tidal stream linking the south-facing space to a brand-new gallery of similarly monumental scale.

South Seas Ceremonial House Ceiling from pieces of painted sago palm leaf stems. The panels, through their designs, are a map of the cosmos, mythical knowledge and clan histories.

The Asmat people of southwest New Guinea honored their ancestors with rituals that reminded the living to avenge their deaths. Their towering carved “bis” poles in the Oceania section, circa 1960, incorporate ancestor figures and were a focal point for memorial feasts.

#the metropolitan museum of art#rockefeller wing#arts of africa#arts of ancient americas#arts of oceana#art#sculpture#video#the new york times#holland cotter#christopher gregory-rivera#micheal c rockefeller collection#gift link#my edited gifs

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Lesser-Known Modernism Inspired by African-American Culture

The Whitney Museum of American Art is presenting the career retrospective “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist,” which includes “Black Belt” (1934).Credit... Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia, Valerie Gerrard Browne

By Holland Cotter Oct. 1, 2015

I don’t know how museums plot their seasons, but it was a good plan to have “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” be the first career retrospective to appear at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s new home. Motley is an important but still understudied figure. The show itself is neither large nor hot off-the-shelf. (It originated at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and has been traveling; this is the last stop.) But it has features that many bigger, sexier exhibitions lack: an affecting narrative, a distinctive atmosphere and a complicated political and moral tenor. It’s a tight, rich package. You take it away with you, complete.

And part of what you take away is an alternative version of the American modernism on which the Whitney is based. This other modernism developed outside of New York. It didn’t adopt abstraction as its defining advance style. It absorbed what was happening in Europe, but found its main power source in American culture, and specifically African-American culture. Archibald J. Motley Jr. — he used his full name professionally — was a primary player in this other tradition.

He was born in New Orleans in 1891 and three years later moved with his family to Chicago, which would become his permanent home. His African-born paternal grandmother, a former slave, came with them. There his father, a child of slaves, found work as a Pullman porter. His mother, of mixed racial descent, ran the house. When Motley’s teenage sister, Flossie, had a child, Willard, out of wedlock, the family raised him to believe that his mother and his uncle were his older siblings.

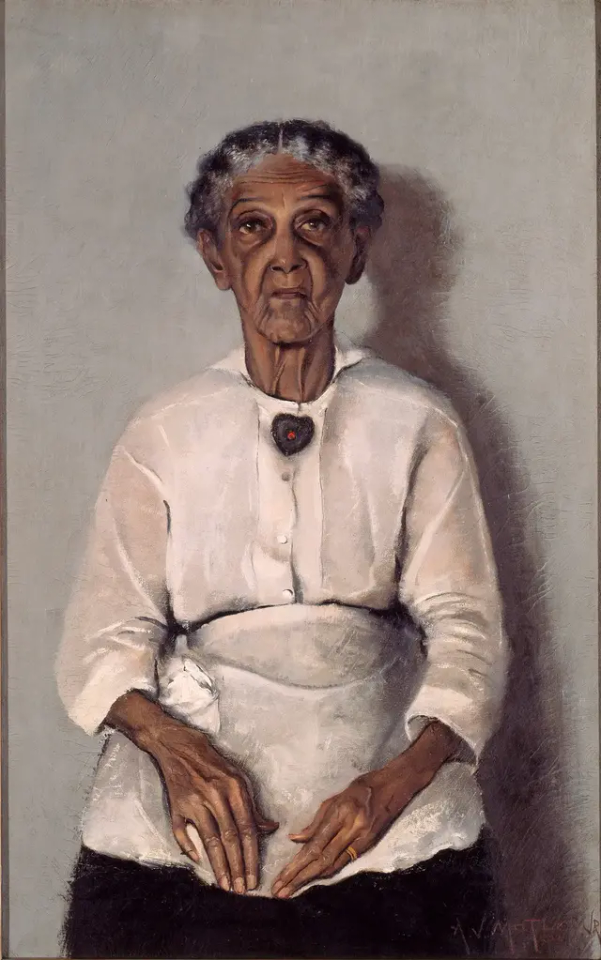

“Portrait of My Grandmother” (1922). Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

“Portrait of Mrs. A.J. Motley, Jr.,” from 1930. Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

Altogether, it was a household in which traditionally fixed categories of race and lineage were somewhat fluid. So was its relationship to class. The Motleys lived outside the so-called Black Belt of Chicago, the strictly demarcated African-American area also referred to as Bronzeville, on the city’s South Side. Their home was in a largely white immigrant neighborhood. Motley was one of the few black students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he received classical, European-based training as a painter. He married a white woman, Edith Granzo, his high school sweetheart.

Calibration of racial and social status by color is an underlying theme in the early portraits that open the exhibition, organized by Richard J. Powell, an art historian at Duke, and Carter E. Foster of the Whitney. Motley believed that information about the biology of race was important for both whites and blacks to have in the interest of mutual understanding.

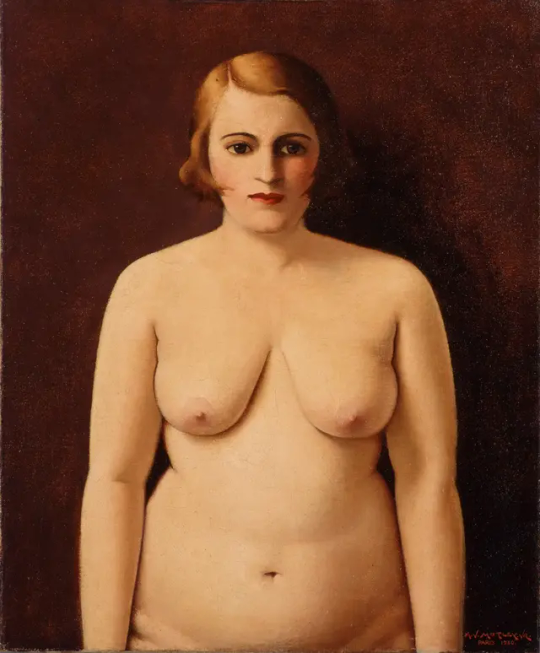

“Nude (Portrait of My Wife)" (1930). Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

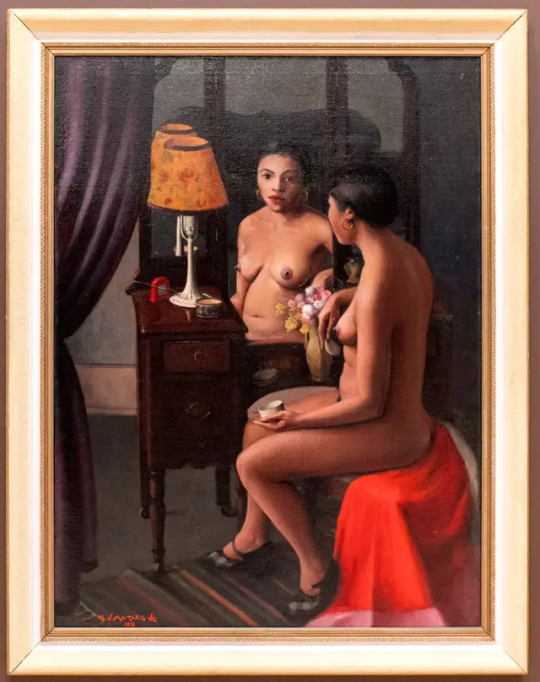

“Brown Girl After the Bath” (1931). Credit... Emon Hassan for The New York Times

In a 1924 picture, a dark-skinned older women dressed in a gingham dress and head scarf is identified as “Mammy.” A painting done a year later of a lighter-skinned young woman in a chic flapper cap is titled “The Octoroon Girl,” using a term once applied to someone with one-eighth black ancestry. In a 1930 nude portrait, Motley’s wife stands erect, arms down, face forward, glowing gold, as if posed for an epidermal inspection. A year later, in a more relaxed painting called “Brown Girl After Bath,” the glow remains, but gold has been exchanged for copper.

These images surround Motley’s own 1933 “Self-Portrait (Myself at Work),” which, ethnically speaking, gives little away. Dressed in a smock and beret, the artist, who by then had spent a year in Paris, looks neither distinctly black nor white, just seriously Continental. A neo-Classical statuette stands on his worktable. A crucifix hangs on the wall. (Motley was a practicing Roman Catholic.) He holds a big palette in one hand and conjures a nude model, Pygmalion-style, with his brush. He was at this point already nearing the peak of his professional success. The historian and activist W. E. B. Du Bois had publicly called him “a credit to the race,” though there is little of an obvious race man in the image here.

“Self-Portrait (Myself at Work)" (1933). Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

This doesn’t mean that he kept himself at a remove from black popular culture. His deep but controlled immersion in it — wading in, stepping back — is what the exhibition as a whole is about. From an early age he had been a regular visitor to the Black Belt entertainment strip of jazz clubs, theaters, cafes and gambling joints known as the Stroll. And a section of the exhibition called “Nights in Bronzeville” is a record, in paintings, of his time spent there. If his portraits are an effort to capture and codify variations in racial appearance, his Bronzeville scenes, and their Paris equivalents, which he produced from the late 1920s onward, are attempts to find visual correlatives for the sounds of black music and colloquial black speech.

“Saturday Night,” from 1935, is a club scene. It takes what Motley learned about figure painting, color and composition, pushes that through an Expressionist filter, and sets it to a sinuous, thumping jazz score. The room is soaked in vermilion light. The band is far in the background, but its rhythms pulse through in the body of a single dancer who sways between the tables.

“Saturday Night” (1935).Credit...Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Valerie Gerrard Browne

“Carnival” (1937).Credit...Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Valerie Gerrard Browne

The same energy fills the night in “Carnival” from 1937, only now the music comes, outdoors, from an accordion-playing minstrel-show figure regaling a crowd of fairgoers. The smartly dressed visitors chat and preen. Stars shine overhead. A fat man in a straw skimmer, looking oddly isolated, moves through the center of the scene.

That man, or his equivalent, shows up in many of Motley’s city pictures. He’s an outrageous racial caricature: round-faced, popeyed, thick-lipped, a cartoon. Mr. Powell, in the catalog, pegs him as Motley’s alter ego, his way of acknowledging a feeling of distance from blackness but also an investment so thorough as to allow him to play with it, mess with it from the inside, as well as from the outside, pre-emptively expressing the racist hostility that is an unabating condition of American life. It’s a tactic used by writers like Zora Neale Hurston in Motley’s time, and in our own by comedians like Richard Pryor and artists like Robert Colescott and Kara Walker.

Motley continued to explore this risky mode of depicting social realities for the rest of his career which, gradually, went into decline. After his wife’s death in 1948, he made extended trips to Mexico, where his nephew Willard, a successful novelist, lived. Back in Chicago, to support his mother, who had remarried after his father’s death, he took a job with a company designing shower curtains. In 1955, he was jailed for six months for assaulting her abusive husband. In 1963, in his 70s, he began his last painting.

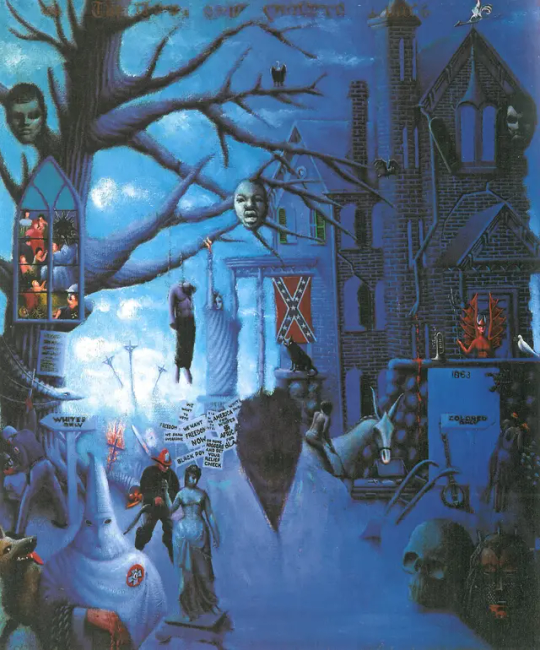

“The First One Hundred Years,” finished in 1972, was Archibald Motley’s final painting, and with its sweepingly topical content, it’s like no other picture he ever made. Credit... Collection of Mara Motley, MD, and Valerie Gerrard Browne

With its epic-length title — “The First One Hundred Years: He Amongst You Who Is Without Sin Shall Cast the First Stone; Forgive Them Father for They Know Not What They Do” — and sweepingly topical content, it’s like no other picture he ever made. Set in a twilight blue space, it has the mood of a composite-style nightmare to which new elements were added over time: an African mask paired with a human skull; a devil’s head and a peace dove; a Ku Klux Klan figure and the Statue of Liberty, and a “coloreds only” sign; a lynching and a crucifixion. And dead center is a man’s head in the format of a bust-length portrait, with the face blacked out.

This painting, hung on a wall by itself, ends the show, just as Motley’s confident 1933 studio self-portrait began it. When he finished “The First One Hundred Years” in 1972, he put his brushes down and painted nothing more in the remaining nine years of his life. His work ends in profound political anger and in unambiguous identification with African-American history. I would say that, behind his gracious portraits and his later, radical, jazz-scored scenes of black urban life, those feelings were in some measure ever-present. They help explain his art’s unforgettably puzzling texture and its surprising weight.

“Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” runs through Jan. 17 at the Whitney Museum of American Art; 212-570-3600, whitney.org.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

NY Times co-chief art critic Holland Cotter's Rabkin Interview dropped last week. Because Times employees are prohibited from receiving cash awards, Holland donated his to the Forge Project, which supports Native American arts criticism and education; and the International Association of Art Critics, which will create a fellowship for emerging arts writers.

[but they don't talk about that in the interview; Cotter just talks about loving art and stuff]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

View of the esxhibition “Mary Sully: Native Modern,” 2024 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Photo : Photo Paul Lachauer. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mary Sully—born Susan Mabel Deloria on the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota—was a reclusive Yankton Dakota self-taught artist who created highly distinctive work informed by her Native American and settler ancestry from the 1920s through the 1940s. The enchanting and revelatory “Mary Sully: Native Modern”gathers 25 drawings, primarily graphite and colored pencil triptychs that she referred to as “personality prints,” each evoking different Euro-American celebrities of her time. Sully’s grandson described her as “a solo artist in every sense of the word,” and accordingly, her works having remained unseen by almost anyone beyond her family during her lifetime. As Holland Cotter observed in the New York Times, she was “personally caught between cultures, ethnicities, social classes, gender expectations, hostage to a still crushing colonial history.”

Art in America

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Bands! - #1

I’m going to start this series of my favorite underground bands, and requests are welcome!

#1 - The Morgans

The Morgans were a short-lived London-based Alternative Rock band.

The band consisted of : Chloe LeFay (vocals), Lucy Cotter (vocals), Russell Pay (guitars), Pete Dixon (guitars), Eddy Brimson (bass, later replaced by Kevin Browne) and David Axford (drums, later replaced by Steve Holland)

The band gained some minor fame in the mid-1990s with some of their tracks being featured on punk and goth compilations. In November 1996 they played their last gig, supporting Theatre of Hate at Camden Palace.

LINKS!

Video of Half-Girl Half-Jesus, no proper YouTube channel for the band could be found.

youtube

Personal Opinion

I personally think these guys are AMAZING! Chloe LeFay’s voice is one of an angel, all the instruments are beautiful, everything. I recommend especially if you enjoy punk that has a hint of goth to it.

#underground#underground band#punk rock#punk#goth#goth music#90s music#music#riot grrrl#the morgans#chloe lefay#90s grunge#grunge#Youtube#Spotify

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What to See in N.Y.C. Galleries in February

This week in Newly Reviewed, Holland Cotter covers two group shows: one devoted to an important gallery from the past, the other focused on language and silence. Upper East Side Acts of Art in Greenwich Village Through March 22. Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Gallery, Hunter College, 132 East 68th Street, Manhattan; 212-772-4991, huntercollegeart.org. D.E.I. didn’t exist in the mainstream New York…

0 notes

Text

What to See in N.Y.C. Galleries in February

This week in Newly Reviewed, Holland Cotter covers two group shows: one devoted to an important gallery from the past, the other focused on language and silence. Upper East Side Acts of Art in Greenwich Village Through March 22. Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Gallery, Hunter College, 132 East 68th Street, Manhattan; 212-772-4991, huntercollegeart.org. D.E.I. didn’t exist in the mainstream New York…

0 notes

Text

[ad_1] The Dorothea & Leo Rabkin Basis in Portland, Maine, has named the winners of its 2024 grants for visible arts journalists, who embody Artwork in America senior editor Emily Watlington. The grants carry an unrestricted $50,000, and acknowledge the “artistic and mental contributions” of arts writers, per a launch from the inspiration. The opposite grant winners are Greg Allen, of greg.org; Holland Cotter, chief artwork critic for The New York Instances; Robin Givhan, senior critic-at-large for the Washington Publish; Los Angeles–based mostly author and painter Thomas Lawson; Siddhartha Mitter, a contract author and common Instances contributor; Cassie Packard, critiques editor at frieze and creator of 2023’s Artwork Guidelines; and TK Smith, a cultural historian and curator of the humanities of Africa and the African diaspora on the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory College in Atlanta. The Rabkin Basis launched the annual prize in 2017, and it nonetheless carries one of many largest purses out there to professionals who write for a normal viewers (quite than educational friends). This 12 months, for the primary time, the Rabkin Basis has commissioned portraits of the grant winners of their most well-liked workspace taken by artist-photographer Kevin J. Miyazaki. The venture, known as the Rabkin Interviews, additionally consists of an interview with Mary Louise Schumacher, the inspiration’s government director, to be revealed on Substack within the following weeks. “I’m grateful … that is going to assist me proceed to do the work for some time frame,” Mitter instructed the Basis, including that his biggest concern as an arts author is “survival” amid the present-day media panorama. “The broader drawback is there’s no present path to sustaining a follow as an arts author.” Judging the grants this 12 months have been Dennis Lim, inventive director of the New York Movie Competition; rashid shabazz, government director of the grant-making venture Essential Minded; and Alexandra Grant, a Los Angeles– and Berlin-based artist. “We needed to humanize the labors of those important writers,” Schumacher, a author herself, mentioned. “We imagine arts writers are within the heart of our most important conversations, assist us suppose collectively in public, create the unique area analysis for artwork historical past, and bear witness to the worth of what artists do.” [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

By M.H. Miller

Sept. 16, 2024

IN THE SUMMER of 1970, as part of the group exhibition “Information,” one of the first major surveys of conceptual art, the artist Hans Haacke presented a work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York called “Poll of MoMA Visitors.” Museumgoers were given slips of paper to deposit into one of two plexiglass boxes. On the wall was a sign about Nelson Rockefeller, then in his third term as governor of New York and running for a fourth. “Question,” it read, “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November? Answer: If ‘yes,’ please cast your ballot into the left box; if ‘no,’ into the right box.”

The Rockefeller family helped found MoMA in 1929. In 1963, Nelson’s brother David was elected the chair of the museum’s board of trustees. As governor, Nelson Rockefeller had begun calling for a broadening of the war in Vietnam and a South Vietnamese-led invasion of Cambodia and Laos as early as 1964. That wasn’t the family’s only connection to the conflict. Henry Kissinger, who worked for the Rockefellers in the 1950s and advised Nelson on his presidential campaigns beginning in 1960, was also Nixon’s national security adviser and the chief architect of the secret carpet bombing campaign of Cambodia that began in 1969 and is estimated to have killed more than 150,000 civilians. It led to the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, which Nixon announced on TV on April 30, 1970. The following day, students began demonstrating across the country in numbers that would soon reach the millions and, on May 4, the National Guard opened fire on protesters at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four.

Tensions were high at MoMA as well, where “Information” opened that July. Haacke kept the exact content of his work secret until he had finished installing it. Unlike a lot of conceptual art, it was simple but, in looking critically at a figure of great behind-the-scenes power at MoMA from the vantage point of an artist exhibiting at the museum, Haacke had created an entirely new art form. David Rockefeller was furious about the exhibition; Nelson Rockefeller’s office called John Hightower, the museum’s director, to ask for Haacke’s poll to be removed, but the work remained. It was among the factors that eventually led to Hightower’s forced resignation. Haacke would quickly become an art-world pariah. For a Guggenheim Museum show scheduled for the following year, he had created a new work called “Shapolsky et al.,” for which he used public records to chart the real estate holdings and shell corporations of the New York City landlord Harry Shapolsky, whom the district attorney had accused of being “a front for high officials of the Department of Buildings” and who had been found guilty of rent gouging. Because of the Shapolsky work, as well as another similar piece about a pair of real estate developers, the Guggenheim’s then-director, Thomas Messer, canceled the exhibition, describing Haacke’s work as “an alien substance” that he would not allow to “[enter] the art museum organism.” The curator Massimiliano Gioni, who co-organized a 2019 solo show of Haacke at the New Museum — the only major American museum ever to give him one — compared the Guggenheim’s censoring of “Shapolsky et al.” to the “legendary refusal of ‘Nude Descending a Staircase,’” referring to Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 Cubo-Futurist painting that was rejected from a Paris exhibition for being, as Duchamp would later describe it, too disrespectful of the nude form. “It’s such a defining moment,” Gioni said of Haacke’s canceled show. “It must have shocked him, but it also proclaimed his integrity, which is at a level that is still uncomfortable for some institutions.”

Before Haacke, museums were considered, in the words of the New York Times critic Holland Cotter, “genteel and politically marginal.” Robber barons might have donated to them to enhance their social clout, but such cultural largess was seldom questioned. Today, though, when phrases like “artwashing” and “toxic philanthropy” have entered the lexicon to describe the role that museums and other cultural organizations play in boosting the images of corporations and billionaires, Haacke’s work is more than just relevant — it’s prophetic. With persistent clarity, he seemed to understand, half a century before anyone else, the stakes of the uncomfortable relationship between art and politics.

ONCE A WEEK for three weeks last May, I met Haacke, who’s 88, at the Bus Stop Cafe on Hudson Street, an almost monastic diner of the kind that doesn’t really exist in Lower Manhattan anymore, where there was never any trouble getting a seat, no one was on a laptop and the waiter didn’t care that we never ordered any food. Each time, Haacke had a glass of cranberry juice. He always brought his son Paul, 47, who’s an adjunct professor of humanities and media studies at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and who didn’t say much other than to delicately push back on a date or some other small detail. (Paul had once worked as a fact-checker at magazines and now assumed that role for his father.)

Haacke isn’t reclusive, but he has tried his best to let his work speak for itself. He’ll occasionally agree to interviews but, as a rule, he won’t show his face in photographs. (Being photographed “would be a problem for me,” he said, the only time he adopted a slightly severe tone.) He’s rail thin, with a neatly trimmed gray beard and perfectly circular glasses, and wore a loosefitting flannel shirt. It was difficult to square what I knew of his work, unforgiving in its critique of wealth and power, with the man himself, who was reserved, friendly and at times so mild-mannered that his voice was inaudible under the sound of buses screeching to a halt a few feet away. He’s one of the most censored artists of the past 100 years, and yet he seemed incapable of expressing anger or resentment. This is how he described “MoMA Poll,” as it is now commonly known: “People would answer yes or no to a question that I put up. And for about 16 years after that, I was not invited to participate in anything at the Museum of Modern Art.” The most animated I saw him was when one of his neighbors from the nearby Westbeth apartment complex — the subsidized artist housing where Haacke has lived since 1971 — zoomed around the corner in an electric wheelchair. “Look how fast she’s going!” said Haacke, who was also using a wheelchair after a recent surgery. He sounded concerned and vaguely envious.

Haacke had been preparing for a major exhibition in Frankfurt that will open at the Schirn Kunsthalle in November and travel to the Belvedere Museum in Vienna. He also currently has work on view in New York, in a group show dedicated to the American flag at Paula Cooper Gallery. The Frankfurt show, a career retrospective, includes many artworks about his native Germany, among them another influential, often suppressed piece, 1981’s “Der Pralinenmeister,” about Peter Ludwig, a chocolate manufacturer and one of Germany’s most famous art collectors. Across 14 framed panels that include photographs of Ludwig and his factory workers, Haacke wrote a text detailing the overlap between patronage and commerce: Ludwig received tax advantages from donating artworks and displaying his collection publicly and would loan artworks to cities where he produced or distributed his chocolate. “Der Pralinenmeister” also notes that Ludwig’s factories housed female foreign workers in on-site hostels that didn’t offer day care, so women who gave birth were forced to leave or find foster homes for their children — or give them up for adoption. According to Haacke’s text, the company’s personnel department stated that it was “a chocolate factory and not a kindergarten.” Ludwig, who died in 1996, was reportedly interested in buying the work, perhaps to remove it from circulation, but Haacke wouldn’t sell it to him.

In works like “Shapolsky” and “Der Pralinenmeister,” Haacke said, “I had to do research like a journalist does.” He’d scour documents, noticing details that other histories ignored, and present facts, often via text, in a detached, almost omniscient voice. Early on, he was influenced by the American art writer Jack Burnham, who developed what he called systems aesthetics in the late ’60s, which Haacke described as “everything is connected to everything else.” (The subtitle of “Shapolsky” identifies it as “A Real-Time Social System.”) Through art, people like Ludwig had managed to quite literally buy themselves good will. Or as David Rockefeller put it in a quote that Haacke engraved on a plaque that he hung at an earlier show at the New Museum in 1986, “Involvement in the arts … can provide a company with extensive publicity and advertising, a brighter public reputation and an improved corporate image.”

HAACKE WAS BORN in Cologne in 1936, the same year that the Nazis marched into the demilitarized Rhineland. His father, a member of the center-left Social Democratic Party, worked for the city; when the Nazis took over, they demanded that everyone in Cologne’s government join the party. Haacke’s father refused and went to work as an accountant.

One of Haacke’s first memories is from when he was 6. “There was an air raid alert during the night, and we were in the basement, trying to wait it out,” he said. “The next morning, when I walked to school on the street where we lived, one building had been hit by a bomb. It was burned out. Otherwise, no other building was hit. I will never forget that.” Why that building and not his? He’d spend the rest of his life trying to extract meaning from such seemingly random events.

In 1956 he moved to Kassel, an industrial town in West Germany within 30 miles of Soviet-occupied territory. He wanted to attend the Kunsthochschule Kassel because, he said, it was “the only art school at that time that was still somewhat in the tradition of the Bauhaus,” which had taken a multidisciplinary approach to teaching subjects as diverse as pottery and typography. His plan was to become a high school art teacher.

Kassel is best known today as the location of Documenta, one of the world’s most important contemporary art exhibitions, held every five years. In 1959, in Documenta’s second iteration, Kunsthochschule students were tasked with running its day-to-day operations, and Haacke, who worked as a security guard and helped with installation, also took pictures, producing his first major work, “Photographic Notes, Documenta 2, 1959.” In a deadpan style, he showed visitors interacting with the exhibition and, in doing so, created a snapshot of Cold War-era West Germany. In one image, a little boy has his back turned to an abstract canvas by Wassily Kandinsky, who had been featured in the Nazis’ 1937 exhibition of so-called degenerate art; the child’s face is buried in a Mickey Mouse comic book instead.

Though he mostly studied abstract painting, he spent much of the ’60s thinking about how to reinvent the medium of sculpture. He met Linda Snyder, a Brooklyn native who had just finished her bachelor’s degree in French, in 1962, while he was in the United States on a Fulbright to study art. They married in Germany in 1965 and returned to the States by ocean liner. (They have one other son, Carl, a tech entrepreneur.) Upon reaching New York Harbor, Haacke received a telegram inviting him to put on a solo exhibition at the Howard Wise Gallery; his friend Otto Piene, a German artist who showed there, had arranged it as a wedding present. (“It was like a fairy tale,” Haacke said of his arrival in Manhattan. “I really was very lucky.”) Initially working out of a one-room studio on the Bowery, he made sculptures that featured natural materials: filling a plexiglass container with water that gradually evaporated and condensed, placing a white sheet above fans so that the material rippled endlessly, planting grass on a mound of dirt. His sculptures foreshadowed his later career, showing an artist obsessed with cause and effect, with decisions and their repercussions.

The shift in his work from physical and ecological systems to overtly political ones dates roughly to 1968. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., he wrote a letter to Burnham: “Linda and I were gloomy for days and still have not quite recovered. The event pressed something into focus that I have known for long but never realized so bitterly and helplessly, namely that what we are doing, the production and the talk about sculpture, has no relation to the urgent problems of our society. … Not a single napalm bomb will not be dropped by all the shows of ‘Angry Arts.’ Art is utterly unsuited as a political tool. … I’ve known that for a number of years, and I was never really bothered by it. All of a sudden it bugs me.”

As an artist, he knew he couldn’t stop a war or influence an election. (Most respondents of “MoMA Poll” seemed disinclined to vote for Rockefeller, but he won a fourth term as governor and served as vice president under Gerald Ford.) Yet “MoMA Poll” helped change how the public thought of the art they saw in a museum and its relationship to the world at large, and Haacke’s work ever since has been as unsparing and revelatory. In 1971, he began conducting demographic surveys of exhibition visitors at the Milwaukee Art Center, the John Weber Gallery in New York and other venues, creating one of the first empiric statements about the art business’s liberal insularity; in 1975, he charted the rise of art as an investment opportunity by tracing, across text panels, the provenance and sales history of Georges Seurat’s 1888 painting “Les Poseuses” (small version), which had passed through, among others, the hands of a Luxembourg-based holding company. And at the 1993 Venice Biennale, only a few years after German reunification, in an installation he titled “Germania,” he destroyed the marble floor of the German pavilion, which had been remodeled by the Nazis in 1938, and hung a picture of Adolf Hitler visiting the Biennale in 1934. At an optimistic moment for democracy and Germany, Haacke reminded people to consider the dark past alongside any brighter future. Paula Cooper, Haacke’s dealer, described waiting in line for the show behind Peter Ludwig. “He didn’t look happy,” she said.

TODAY, HAACKE OCCUPIES an unusual place in the contemporary canon: He has been illustrious and canceled, critically revered and commercially undervalued. He supported himself by teaching at Cooper Union for 35 years, and Gioni told me that he’s one of the only artists of his caliber who still owns much of his work. “Hans is extremely successful,” Gioni said, “but he lives his success in ways that are rarely celebrated by the art industry. He’s Franciscan in his modesty.” The art historian Benjamin Buchloh, who considers Haacke to be one of the most important postwar figures, said with disappointment that at this moment in time, “nothing could be further from the mind of the New York art world than Hans Haacke.” That his 2019 retrospective in New York was at the New Museum and not, say, MoMA “shows that institutions don’t feel comfortable with the challenge he poses, even now,” Buchloh said.

We often think of artists as being ahead of their time. Perhaps Haacke was so far ahead of his that it’s not fair to expect the world to catch up to him, this man who, out of what Gioni described as a “perverse form of love,” held museums to a higher moral standard than most religions require of their practitioners. One can, however, see his legacy in the rise of activist groups like the Guerrilla Girls in the 1980s, who’ve critiqued art institutions for their exclusion of female artists, and more recently Just Stop Oil, Occupy Museums and the photographer Nan Goldin’s P.A.I.N., which have forced museums to sever ties with collectors who came by their wealth through profiteering, like the Sackler family with their opioid fortune. Despite Haacke’s work being uncommercial, his influence has seeped into the wider culture, an uncommon feat for a conceptual artist. In reminding the public that museums, like universities, don’t exist on some higher plane above the scrum of politics and business but are in their own way corporations making decisions that can be as calculated as a bank’s, he created a subgenre of art that is now so widespread that we take its very existence for granted. His heirs include Darren Bader, Andrea Fraser, Walid Raad, Fred Wilson and any artist who has made the structural flaws of the art business into their subject. In the years since “MoMA Poll” went up, cultural institutions in general have been forced to look more closely at the sources of their funding. There was great outrage over the Koch brothers, for instance, who have long used their fortune to prevent federal climate change regulations, putting their names on the facades of venues like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Often the uproar fizzles out. (The public space in front of the Met was renamed the David H. Koch Plaza in 2014.) But it was Haacke who helped show people where to direct their indignation.

Unlike some of his peers, though, Haacke has never been a spokesperson for the causes championed in his work. His art isn’t didactic. He’s blunt but measured, driven by inquiry rather than impulse. He didn’t have a lot to say about the current state of the art world, where censorship and fear among galleries and museums navigating political fault lines have increased of late. He had spent too much of the last year in a hospital bed, unequipped to perform his usual investigations. The conduct of the art business — and the possibility of art actually influencing politics — was now a younger generation’s responsibility.

But Haacke had certainly left them an interesting road map. In our last meeting, we discussed what is probably his most hopeful work, “Der Bevölkerung” (2000), whose title translates as “To the Population.” It’s an enormous trough of soil with that phrase spelled out in neon letters, permanently installed in the courtyard of the Reichstag, the German parliament in Berlin. The idea was that throughout the year, representatives would bring soil from their districts, and it would mix together, home to whatever sprouted in it, a metaphor for the democratic experiment. The phrase “Der Bevölkerung” is a play on the inscription on the facade of the Reichstag: “Dem Deutschen Volke,” which means “To the German People.” Haacke proposed the work in 1999, at a time of increased migration to Germany from Turkey and other predominately Muslim countries. “Rather than a dedication to the German people, I wanted a dedication to the people who live in the country,” Haacke said, not just “those who were native German, so to speak.” The center-right Christian Democratic Union, which then held a majority of seats in parliament, was “solidly against” Haacke’s idea, he said, and pushed for the 669-member body to debate whether to let him install his art at the Reichstag.

“There was furious resistance to my proposal,” said Haacke, who attended the proceedings in April 2000. “I didn’t believe that it would pass. In the end, it did [by] two votes.” Among those in favor of the work were two women who voted against their own party, and one of them, Haacke said, “was from Nuremberg, where the Nazis were prosecuted for crimes against humanity.”

Next year is the work’s 25th anniversary. Anti-immigrant sentiment is on the rise in Germany, as in many Western nations, and the far right has gained more power there. But, Haacke told me, “things have changed. After a while, a considerable number of people from the parties that had voted against ‘Der Bevölkerung’ have contributed soil.”

It’s not only soil. In it are seeds from plants, and their blooming has become an annual ritual. “I insisted it should not be a garden,” Haacke said. “It was a wild growth.” More important, he added, “it’s ongoing.” The work wasn’t complete. By design, it never would be.

0 notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: What Our Critics Are Looking Forward to in 2024 by Holland Cotter, Alissa Wilkinson, Mike Hale, Salamishah Tillet, Jesse Green, Maya Phillips, Jason Zinoman, Margaret Lyons, Zachary Woolfe and Jon Pareles

By Holland Cotter, Alissa Wilkinson, Mike Hale, Salamishah Tillet, Jesse Green, Maya Phillips, Jason Zinoman, Margaret Lyons, Zachary Woolfe and Jon Pareles “Mad Max” gets a prequel, “The Wiz” returns to Broadway and Larry David gets another crack at a series finale. Published: January 1, 2024 at 05:01AM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/XWIN9Dw via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Cross-Cultural Exchanges from Vietnam, Ethiopia, the Caribbean

Solo shows also abound, from Charles Gaines to Harry Smith, while the women of Land Art and Fluxus keep rocking in major exhibitions. source https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/02/arts/design/holland-cotter-art-exhibitions-museums-fall.html

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

By BY ROBERTA SMITH, HOLLAND COTTER, JILLIAN STEINHAUER AND WILL HEINRICH from Arts in the New York Times-https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/arts/design/4-art-gallery-shows-to-see-right-now.html?partner=IFTTT David Byrd’s hospital paintings; Cory Arcangel’s video game installations; Lucas Blalock’s disquieting still-life images; and Hugh Steers’ portraits during the AIDS crisis. 4 Art Gallery Shows to See Right Now New York Times

0 notes

Text

New York Times Has a 'Manifesto' for Boston's MFA

New York Times Has a ‘Manifesto’ for Boston’s MFA

The other day the New York Times ran a big takeout by art critic Holland Cotter on what major U.S. museums should be doing nowadays with their time and money.

For Big Museums, It’s Time to Change

As the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston commemorate their 150th birthdays in a state of heightened scrutiny, our critic offers a five-point plan to save the souls of our…

View On WordPress

#Alice Neel#Ancient Nubia Now#“Why Are There No Great Women Artists?”#Boston Museum of Fine Arts#Holland Cotter#Linda Nochlin#Metropolitan Museum of Art#New York Times#Women Take the Floor

0 notes

Text

al things considered — when i post my masterpiece #806

first posted in facebook february 25, 2020

peter saul -- "washington crossing the delaware" (1975)

"there's a small group of people always watching me to make sure i'm still offending" ... peter saul

"saul’s politically charged, and often politically incorrect, paintings are rooted in a system of removal from the artist’s beliefs, void of morals and ambivalent in their politics. saul sources imagery from popular culture and current and historical events for his cartoonish and surreal depictions. the resulting paintings of the grotesque are more akin to social commentary than clear political statements" ... press release from venus over manhattan

"not to be shocking means to agree to be furniture" ... peter saul

"through a long career he has used offensiveness as a form of resistance — political, personal — and just by doing so given everyone permission to do the same. you won’t hear him acknowledge that though. more and more, in interviews in recent years, he has taken to insisting that all he’s ever really been interested in was opportunistically grabbing attention by being outrageous. saying this may be his way of slipping out of the categorizing grip of art history, preventing it from getting a handle on him. anyway, i don’t believe him. his art is the work of a brilliant showman who is also a canny ethicist" ... holland cotter

"i am now Imbarkd on a tempestuous Ocean from whence, perhaps, no friendly harbour is to be found" ... george washington

"i'll cross the delaware when i come to it" ... al janik

#peter saul#washington crossing the delaware#george washington#offending#venus over manhattan#politically incorrect#furniture#shocking#holland cotter#offensiveness#outrageous#cartoonish#friendly harbour#the delaware#surreal depictions#al things considered

0 notes

Photo

Holland Cotter on Thoreau in The New York Times: “Thoreau: American Resister (and Kitten Rescuer)” (what a title!)

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“So, in a blatant act of fake-news making, he flipped the story. He had the Union uniforms recolored gray, and the Confederate uniforms painted blue. In a scene showing the capture of a Confederate flag, the flag was painted out. He advertised ‘The Battle of Atlanta’ as a Confederate victory.”

Holland Cotter, “A Victory for the Civil War ‘Cyclorama’,” The New York Times, Feb. 21, 2019, web [https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/21/arts/design/confederate-monuments-cyclorama-atlanta.html]

0 notes