#BRO 1989 CAME OUT FIVE MINUTES AGO

Text

yall pray for my friend. aint nothing wrong w her shes jus convinced taylors announcing debut tv tonight

#BRO 1989 CAME OUT FIVE MINUTES AGO#N REP IS OBVIOUSLY COMING FIRST#SIGH my friends a huge debut girlie#shes upset she doesnt have debut tv yet n is TAKING IT OUT ON ME#taylor swift

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morrie’s Wigs: Behind The Curtain

‘And remember: Morrie’s wigs are tested against hurricane winds.’

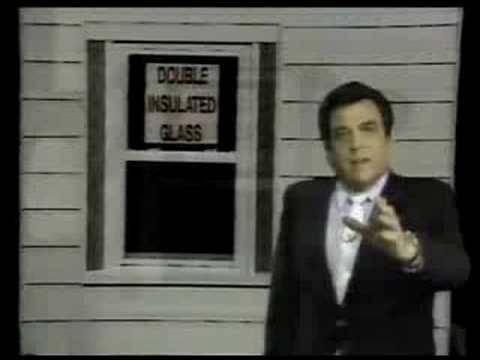

Sight unseen, such a line doesn't sound like classic movie dialogue. But none of this is normal. This 18-second fake ad, 37 minutes into Goodfellas: what an absurdly quotable piece of footage, a joy for everything it is and everything it isn’t. What an introduction to Morrie, the loveable schmuck, who just seems so happy – if only we could all be as happy as Morrie – so utterly behind this endeavour, so brazenly into the hard sell. The clincher of course is the cheapness: it’s all so wonderfully unsophisticated.

youtube

I wrote about this before, briefly, in my investigation into all things Morrie and actor Chuck Low. But more has come to light. So down we go. Another rabbit hole.

Goodfellas’ Morris Kessler was based on Marty Krugman, a 1970s bookmaker and owner of a hairdressers and wig salon, For Men Only, just up the street from Henry Hill’s Queens nightclub The Suite. As you can read here, the salon doubled as a collection point for betting slips and cash, and was also, in curtained off back rooms, a little den for a bit of gangster business. Henry and made man Paul Vario (Goodfellas’ Paul Cicero) bought hairpieces from Marty, whose wigs were known for their durability. Even underwater.

Much of the business’ reputation was due to Marty’s TV commercials, in which he himself hawked the hairpieces. They would broadcast late at night on Queens Public Television and featured Marty, according to Goodfellas’ source material, Nicholas Pileggi’s book Wiseguy, ‘swimming vigorously across a pool wearing his wig while an announcer proclaimed that Krugman’s wigs always stayed put.’

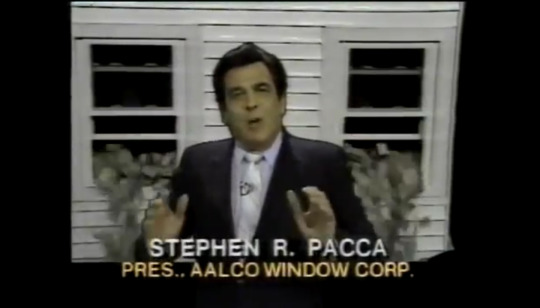

While researching Morrie a couple of years ago I found, via some audio footnotes on GQ’s Goodfellas oral history, that Scorsese had an idea to include a recreation of Morrie/Marty’s ad in the film. One night, according to Joe Reidy, the first assistant director on Goodfellas, Scorsese saw a crude TV commercial for a windows company called Aalco, and wanted it to look exactly like that. He had his people track down the company’s boss, a man named Stephen Pacca who, they discovered, was also the guy on screen, selling his own product. They called him in for a meeting in view of having him consult on the Morrie ad, then asked him make it himself, just as he did his windows ad. Scorsese left him to it.

I’d looked for Pacca and found that he’d died in 1994. But recently I got a message from his son, Stephen Pacca Jr, who’d seen my blog, loved the bit on his dad, and wanted to give me the whole story. I spoke to him, and to Joe Reidy.

“My dad had gotten into the business in the 1970s, we sold vinyl replacement windows,” says Pacca Jr of his father’s company, Aalco. In the 1980s, Pacca Sr separated from his wife and the business was hit with dire financial problems, and one night after work he and his cousin, the company’s general manager, went for a drink. “After a few drinks sat at the bar, my dad was looped,” says Pacca Jr. “He didn’t drink, so he didn’t have any tolerance for alcohol. He looked at my cousin and he said, ‘Johnny, I’ve got the solution to not go bankrupt – we’re gonna go on television.’ My cousin was looking at him like this was absurd. But my dad said, ‘We’re gonna make a commercial, we’re gonna go on television.’ And that’s exactly what they did.”

His father was probably inspired, says Pacca Jr, by the TV ads for electronics chain Crazy Eddie’s, which ran over 7,500 commercials throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. The company was named after its Brooklyn owner Eddie Antar; many assumed he was the one screaming his lungs out in the ads, although the on-screen huckster was actually radio DJ Jerry Carroll. “His commercials were a lot more popular than ours,” says Pacca Jr. “The guy was screaming: ‘Our prices are insane!!’ His commercials were wild.” Yes:

youtube

Pacca had not previously made anything for television. He approached WNYW – New York’s Channel 5 – and got them to fund the commercial (for around $7,000, says Pacca Jr) in exchange for Pacca buying over $30,000 of airtime a week. But he wrote and made it himself. “He got the help of an advertising agency, but it was just a small guy and all he really did was print my dad’s storyboards,” says Pacca Jr.

“All people remember about our commercial was the money coming out of the window. They don’t remember my dad’s name, they don’t remember the company name. Somebody opens an old window and my dad says, ‘Homeowners, don’t worry about money,’ and then 5000 single dollar bills go through the window. We built a chute behind the window and we had five people just dumping the money in this chute, with big fans, so the money would all blow out the window.”

It worked. “The whole success of that business was the commercial,” says Pacca Jr. “Our business skyrocketed. We had six girls in the office just answering phones. In one year, we went from $1.7m in sales and a staff of five, to $15m in sales and a staff of 250.” And this is why. In all its breathless glory:

youtube

“They were so badly made,” says Joe Reidy, Scorsese’s first assistant director on Goodfellas, of Stephen Pacca’s commercials – after the success of the first one, he did a few more. That original one though, says Reidy, was “the one that got Marty’s attention.” Scorsese kept seeing it on TV and was fascinated by it. “The idea of making the wig commercial was just because of Steve Pacca’s ad,” says Reidy. “While we were in pre-production on Goodfellas, the content of the commercial didn’t exist. Then Marty had this idea that Morrie would have this commercial running and it would play in his shop as part of the scene. So that was incorporated in the script, he and [co-writer] Nick Pileggi must have spoken about it.”

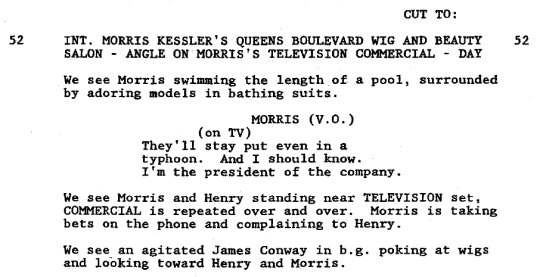

You can see in the Goodfellas shooting script, dated January 1989, that it simply has Morrie swimming across a pool, just as Marty Krugman’s ad is described in Wiseguy, with the addition of some minimal Morrie voiceover.

“Marty wanted to make it like that,” says Reidy. “He wanted us to track down who directed the commercial that Steve Pacca was in – we didn’t know he had made it. I can’t remember who actually found him, it could have been me. But we basically called the company to find out who made the commercial, and the call got kicked upstairs quite quickly because it was not a very big company, it went to him. And he said, ‘We made it.’”

Then Scorsese got on the phone. Pacca Jr remembers it well. “I’m sitting in the office one day with the girls answering the phones, and the head girl, Diane, she says to me, ‘Stephen, I got a man on the phone who says he’s Martin Scorsese, and he wants to talk to your father.’ Oh my god, it was really him! And he told my dad he wanted to make a commercial exactly like our window commercial. He was very emphatic about that, he said ‘I want the exact same commercial, but I just want it to be about wigs.’”

Pacca was asked to go and meet Scorsese, “who got very very excited about it,” says Reidy. “It was not even a matter of, ‘Do you wanna meet him and see if it would work out,’ it was, ‘We’re gonna use this guy no matter what.’ And once Marty met him, it was over, it was decided Steve would do it.” After an initial meeting at Scorsese’s office was a follow-up, in which an excitable Pacca went full dog and pony.

“He made a presentation for Marty,” says Reidy. “The man came in with storyboards. They were primitive, but he had designed a commercial, how it would go, he had written a script. He had basically everything in line for shooting it. He drew the wig coming off. He drew off screen, off the edges of the storyboard, where the fan would be placed [to simulate the hurricane winds]. He drew the fishing tackle pulling the wig off, so that people would know how it would be done.”

Swimming pool aside, the ideas were Pacca’s. “Mr Scorsese didn’t tell him to have the guy jump in the swimming pool,” says Pacca Jr. “He didn’t tell him anything. My dad told him what he’d do, that he’d have the actor talking and then we’d print his name at the bottom and then he’ll jump in the pool and the wig’s gonna stay on. And Marty just said, ‘Okay, whatever you say.’ He gave him carte blanche to do what he wanted.”

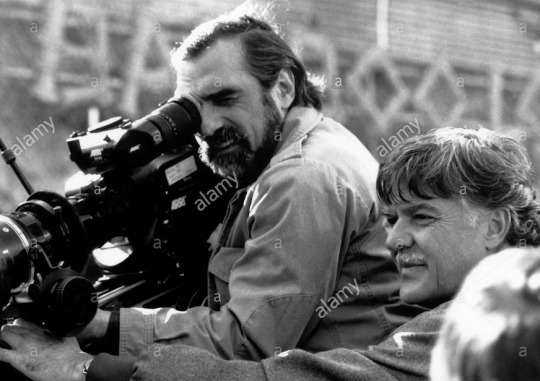

“What we all agreed on,” says Reidy, “was that Steve would not only direct it, but he would put everything together. The only things we would provide would be the camera and our Director Of Photography, Michael Ballhaus, to shoot it, but he’d take direction from Steve Pacca. Michael had two assistants, and a sound mixer and boom operator, but again only under Steve’s direction. All of the special effects, all the prop work, all the make-up and wardrobe would be done by Steve Pacca’s group, which were really people who worked in his office or installed the windows. Someone operating a fan? His guy, with a fan that they brought. A normal house fan.”

Warner Bros, says Reidy, decided that it would be a kind of unofficial part of the production, giving Pacca freedom to do whatever he wanted. That caused some confusion, says Pacca Jr – his father didn’t realise that Scorsese’s team would give him whatever support he needed, so he just went ahead and took it all on, using his company staff. He rented the Lodi Boys Club in New Jersey, which had an indoor pool, for the interior shoot. It was all too much.

“My dad didn’t realise how time-consuming making this wig commercial was gonna be,” says Pacca Jr. The shoot was only a day or two, but with pre- and post-production, the project took a month. “I said, ‘Dad why don’t you ask the guy to help you?’ He said, ‘No no no, he asked me to make this commercial and I’m gonna deliver him the finished product.’ He wanted to be very proud of his work, you know?”

At some point, chiefly because he wasn’t able to do his day to day job while doing this, Pacca snapped. “He called Mr Scorsese up,” says Pacca Jr, “and he told him he quit! I wasn’t in the room when he had the conversation, he told me afterwards. Mr Scorsese said, ‘What?! You quit? Steve, you can’t quit! There’s too much involved here, we’ve got too much going on!’”

The Morrie ad was the first thing being shot for Goodfellas, which itself was now about a week and a half away from filming. “Mr Scorsese said, ‘Is it about money?’” says Pacca Jr. “And my father said, ‘No no no, I just don’t have time for this, it’s costing me too much money. It is about money, but it’s not the money you’re giving me!’ He was giving my dad $2,500. But my dad, I bet you he spent $10,000 of his own money making this commercial.”

On what? “Well I don’t think he asked for money to rent the boys club. I don’t know who he used for actors, but I know he paid people. This guy’s gonna jump in the pool and his wig’s gonna stay on, it looks like it’s not a big thing, but it is! And Martin Scorsese went crazy: ‘I’ll give you more money!’ And my dad says, ‘You don’t have enough money to give me, because this is costing me my business! It’s not about dollars, it’s costing me time.’ So Marty says, ‘Look, whether it’s about money or not, I’m gonna give you £5,000 instead of $2,500 – please finish this commercial for me.’ So my father finally agreed to finish it.”

And a rejuvenated Pacca did the shoot. He got satin baseball jackets made for his crew, imprinted with the film’s working title, Wiseguy. Scorsese stayed away, determined not to dilute the purity of the project. The Goodfellas hair and wardrobe department provided Morrie’s wig and outfit, and checked that Pacca’s supporting ‘actors’ were dressed accurately for the period. Other than that, Pacca was allowed to just “make the commercial the way he would have made it if he were the wig man,” says Reidy. “The guys who came to do this, they didn’t know anything about filmmaking. The other women in the background [of the commercial]: these were all people Steve Pacca knew. We didn’t interfere, we didn’t suggest any way to make it better.”

Michael Ballhaus, the Goodfellas cinematographer who had previously worked with Scorsese on After Hours, The Color Of Money and The Last Temptation Of Christ, didn’t bring lights. “Michael had seen plenty of bad commercials to know that he wasn’t going to light it,” says Reidy. “He wasn’t going to do anything except turn the lights on inside the pool. And it was just sort of drab as a result. Michael knew that and was very excited about it, he said, ‘It’s gonna be great!’ It was very surreal because he was taking direction from a man who didn’t know anything about directing. Excuse me, no: Steve Pacca knew what he needed to do, what he wanted to do. And Michael was in the spirit, he was very enthused about it.”

Martin Scorsese and Michael Ballhaus on Goodfellas. Photo taken from Alamy, can you tell

And Pacca got Chuck Low to those locations, and told him what to do, and how to do it. Pacca Jr was at the shoot for a bit but, 28 years on, doesn’t remember much. “I just remember him jumping in the pool,” he says. “That was a highlight.”

Pacca edited the ad and submitted it just as we see it in the film. “Marty was so, so pleased with it,” says Reidy. “So happy. He was laughing, he was thrilled, it really broke him up. He really loved it.” And that was that. Scorsese shot Goodfellas, and invited Pacca to the premiere.

Pacca set up another business, for second mortgages, and made an ad for that too. This time he had a horse. “He brought it up the elevator at the Channel 5 studio,” says Pacca Jr. “The horse had saddlebags, and in the saddlebags was money, which all came out somehow.”

Pacca Jr told me a lot about his dad’s highs and lows, about how he’d make millions then go broke, then make millions again, then go broke again. At one point he built a recording studio in his office, “with speakers that cost $15,000 a piece. I guess he always had wanted to be in showbusiness in some way. He would sing, he would record music, he made a couple of records with pictures of him on the front. But it never took off.” Having grown up poor, says Pacca Jr, his father deemed it important to always have a new car so bought a new Cadillac convertible every year, whether he could afford to or not. He would, says Pacca Jr, drive through Harlem and have people wave and call out his name, such was his fame from the TV commercials. He was known to pull over and give homeless people $200: “He just was very generous to strangers.”

I asked Pacca Jr how his father died. Around 1989, he says, Pacca had kidney failure, and was put on dialysis for two years. Pacca Jr pleaded with him to take one of his kidneys, but he refused right up to the last minute. Finally, after a third emergency visit to hospital in the space of a month, he insisted. “I looked at him that day in the hospital and said, ‘Look, if you don’t take my kidney, you’re gonna die. It’s as simple as that. You almost died tonight.” Pacca agreed, and the operation was scheduled for Christmas Eve morning: “It was a nice Christmas present for me to give to him.”

In 1994 though, Pacca had a heart attack. “He climbed up to the fifth floor of a building, surveying the building to do 500 windows for a guy, and he sat down in the guy’s kitchen, turned blue and dropped dead. But he got three or four good years when he wasn’t suffering. I was happy to be able to be a part of that.”

We’ve all got a lot of happiness from Stephen Pacca. So think of him when you watch that Morrie’s Wigs ad. Just a simple window salesman who made a piece of movie history. And please. Don’t throw money out of the window.

And that’s that.

My Chuck Low extravaganza lives here, and my unhealthy unraveling of the Goodfellas dog painting is here.

#goodfellas#morrie#morrie's wigs#chuck low#martin scorsese#scorsese#stephen pacca#commercials#wigs#windows

51 notes

·

View notes

Link

Spike Lee’s Malcolm X is one of the towering cinematic achievements of the 1990s. The dramatic retelling of the life and history of Malcolm X is Lee’s crown jewel and one of the most acclaimed performances of actor Denzel Washington’s career. Twenty-five years later, its subject matter is just as timely as ever. And the story of its making is particularly resonant in a time when black stories are being rolled out on the big and small screens at a rate that we haven’t seen since, well…25 years ago.

The film’s history is famously complicated. There had been talk of a film about the life of Malcolm X since the late 1960s, when producer Marvin Worth secured the movie rights to his autobiography from Malcolm’s widow Betty Shabazz and author Alex Haley. Worth recruited James Baldwin to pen a screenplay. The experience proved ultimately fruitless and frustrating for Baldwin. Malcolm’s associates were pressuring Baldwin to deliver their version of Malcolm’s story, while the movie producers wanted to see their version on the page. Struggling with his own emotional burnout in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Baldwin was finding it hard to get this script going.

Blacklisted screenwriter Arnold Perl was brought in to assist with the screenplay, which was overlong and lacked a clear ending—largely due to Baldwin’s concerns about the Nation of Islam. But Baldwin was chiefly frustrated by Columbia Pictures’ machinations; he felt the white filmmakers were all-too-eager to levy blame at the Nation of Islam for Malcolm’s death as a way of softening the racism he’d suffered at the hands of whites. Vowing to never repeat the experience, Baldwin ultimately departed the film in the early 1970s. He would release his version of the script as the book One Day When I Was Lost in 1972.

For almost twenty years, Warner Bros (who’d gotten the rights after Columbia dumped the project) attempted to revisit the Malcolm X screenplay. David Bradley, Charles Fuller and David Mamet were considered for revisions to the script. There was talk of Sidney Lumet directing, and Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor were considered for principle roles. But nothing really materialized until Norman Jewison (In the Heat of the Night) was named as a likely director for the revamped project in the late 1980s. Spike Lee, a critical darling following acclaimed films like She’s Gotta Have It and School Daze, was particularly vocal in his criticism of a white director helming a film about the life of Malcolm X. A letter-writing campaign ensued against Jewison directing (Lee denied that he had anything to do with it.)

“I had problems with a white director directing this film,” Lee told the Los Angeles Times in 1992. “Unless you are black, you do not know what it means to be a black person in this country.”

The backlash against Jewison galvanized Lee’s campaign to direct the movie himself, noting that many affiliated with Malcolm wouldn’t have been comfortable sharing stories with white filmmakers.

“These people are very leery of opening up to white directors,” Lee also stated at the time. “Most black people are suspicious of white people and their motives. That's just reality.”

Lee’s bravado had become something of a hallmark for the director; he was now fully centered in the pop culture conversation following the success of 1989’s Do the Right Thing, and was being lauded as leader of a vanguard of new black filmmakers looking to stake their claim in cinema. Lee would be named director of the forthcoming film, but it wasn’t hailed as a victory for black filmmakers at the time. Quite the contrary, many elder civil rights leaders had a problem with Hollywood’s trendy new Negro filmmaker taking over the movie. One of the most vocal critics was Amiri Baraka, who felt that Spike would exploit the story of Malcolm X.

“We will not let Malcolm X’s life be trashed to make middle-class Negroes sleep easier,” Baraka famously said, criticizing Lee’s previous work as stereotypical. “People ask me, ‘Why you messing with Spike?’ Spike Lee is part of a retrograde movement in this country.”

Betty Shabazz served as a consultant to Lee on the movie and voiced her support for the director and expressed understanding of his critics. “Just because Spike Lee is doing a film, don’t mean he owns Malcolm,” Shabazz pointed out in the months prior to its release.

The pervading idea was that Spike Lee was going to make the Malcolm X movie that Hollywood wanted him to make. The apprehension was understandable, and after learning that Oscar-winner Denzel Washington would be playing the lead (he’d been cast by Jewison while he was still affiliated with the film), there seemed to be further evidence of Malcolm’s mainstreaming.

But the skepticism proved to be somewhat unfounded once the cameras started rolling. Lee brought a devotion and fervor to the project that led to clashes with Warner Bros. Most notably, his demand of a $33 million budget was reduced to $25 million as the studio balked at the idea of flying Washington and a crew to Mecca and Cairo to film scenes depicting Malcolm’s hajj. The studio wanted the scenes to be filmed in Arizona to cut costs; Lee stood his ground and the crew was able to film in The Holy City, becoming the first-ever non-documentary (and American film) to do so.

“What we really want to put out is what we feel is the true image of Malcolm because there have been so many misconceptions of what he stood for—Malcolm X hated white people, Malcolm X promoted violence, Malcolm X this, Malcolm X that.”

“A lot of people's perceptions [about Malcolm X)] came about by the media,” Lee said, adding that, “Malcolm X scared not only white people but many blacks of his generation as well.”

But the ballooning cost led to a clash between Lee and Completion Bond Company, which had assumed costs midway through production. The bond company declared that the movie would not be longer than 2 hours 15 minutes and explained that Warner Bros. would not provide any additional funding. Lee famously fought to finish the movie as he saw it; and money was donated by luminaries such as Prince, Oprah Winfrey, Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Janet Jackson, Duke Ellington School of the Arts founder Peggy Cooper Cafritz, and Lee himself.

The film would be released on Nov. 18, 1992. Spike Lee’s Malcolm X is a cinematic tour-de-force; a layered, gorgeous examination of a man’s complex and powerful life—with a towering performance from Denzel Washington, as well as Angela Bassett as Betty Shabazz and Delroy Lindo as Malcolm’s mentor in crime from his early days in Harlem. Lee’s typical heavy-handedness is decidedly muted in X; there’s a grace that belies his reverence for the material, even while opening the film with footage from the then-current and still-relevant Rodney King beating of 1991.

Lee famously urged students to skip school to see the movie upon its release; and drew heavy criticism when he said he only wanted to be interviewed by black media. Lee’s audaciousness has always been a gift and a curse, but in the tense aftermath of the L.A. riots and with an election year swirling, his approach seemed to amplify an ongoing conversation about race and racism that American still wrestles with 25 years later. And it definitely rankled people in high places.

youtube

The movie was famously snubbed at the 1993 Academy Awards. Washington received a nomination for Best Actor, but the film was not nominated for Best Picture nor was Lee for Best Director. Washington would lose Best Actor to Al Pacino for Scent of A Woman.

In fighting to make the film that he wanted to make—from his anti-Jewison campaign to his move to land outside funding—Lee upended the standard operating procedure Hollywood tended to exercise when making black films. Even when looking at some of the movies that have come in the years since X, it’s obvious that black period pieces are given limited room to be fully realized. Major studio biopics like Get on Up (about the life and career of James Brown) and 42 (about baseball legend Jackie Robinson) are rarely given the kind of funding that is granted to films such as Lincoln or Walk the Line. For X to be made the right way, it needed someone willing to fight against that. And in the end, the film was stronger for it—as was black filmmaking.

Even today, Malcolm X feels like the crescendo of sorts for the wave of black filmmaking that had come to the fore in the late 1980s/early 1990s. Beginning with Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It in 1986, a generation of rebel filmmakers that also included Keenan Ivory Wayans, John Singleton, Julie Dash, Reginald Hudlin, Robert Townsend, Matty Rich and the Hughes Brothers had redefined what it meant to tell black stories onscreen. Ambitious films like Jungle Fever and more modest successes like The Five Heartbeats had become standard-bearers of black cinema—some with mainstream co-signs and some without.

In Lee’s sprawling, ambitious biopic, filmgoers were given a black cinematic epic; it covers decades in the man’s life while also highlighting the black American experience from the ‘40s to the ‘60s. The great cultural awakening of black people over that same period of time is embodied in Malcolm’s life experiences—from rural and impoverished, to urban and disenfranchised, imprisonment and enlightenment. In the story of one man finding his purpose, Spike Lee gave us the story of a people finding their voice.

#spike lee#malcolm x#james baldwin#one day when i was lost#nation of islam#columbia pictures#arnold perl#david bradley#charles fuller#david mamet#sidney lumet#eddie murphy#richard pryor#norman jewison#amiri baraka#warner bros#completion bond company#prince rogers nelson#oprah winfrey#michael jordan#magic johnson#janet jackson#peggy cooper cafritz#angela bassett#betty shabazz#delroy lindo#rodney king#video#youtube#trailer

0 notes