#Booker T Washington High School

Text

The Texas Rocket Trail 2023 Ended in Southeast Texas/Smith Point Friday

Friday marked the end of the Texas Rocket Trail for Rockets 2023, as the second and final day of launches in Smith Point boasted good weather and a steady line of rockets coming for testing. The original schedule listed 22 rockets for testing, but by day’s end one carryover from Thursday added and 5 vehicles dropped off the docket, leaving only 18 to launch which still creates a full day.

Most…

View On WordPress

#Highschoolrockets#ItISRocketScience#Launcher01#RideTheSkies#Rockets 2023#rocketscience#RocketSeason#STEMRockets#SystemsGoNews#SystemsGoNM#Anahuac High School#Booker T Washington High School#Brazosport High School#Brazoswood High School#Captain Garrett#Channelview High School#Chelsea Burow#creative writing#engineering#engineers#Facebook#fredericksburg#Fredericksburg High School#Gary High School#Ginger Burow#GingerBurow#Goddard Level#Hardin-Jefferson High School#Harleton High Scool#houston

0 notes

Text

Public Domain Black History Books

For the day Frederick Douglass celebrated as his birthday (February 14, Douglass Day, and the reason February is Black History Month), here's a selection of historical books by Black authors covering various aspects of Black history (mostly in the US) that you can download For Free, Legally And Easily!

Slave Narratives

This comprised a hugely influential genre of Black writing throughout the 1800s - memoirs of people born (or kidnapped) into slavery, their experiences, and their escapes. These were often published to fuel the abolitionist movement against slavery in the 1820s-1860s and are graphic and uncompromising about the horrors of slavery, the redemptive power of literacy, and the importance of abolitionist support.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass - 1845 - one of the most iconic autobiographies of the 1800s, covering his early life when he was enslaved in Maryland, and his escape to Massachusetts where he became a leading figure in the abolition movement.

Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom by William and Ellen Craft - 1860 - the memoir of a married couple's escape from slavery in Georgia, to Philadelphia and eventually to England. Ellen Craft was half-white, the child of her enslaver, but she could pass as white, and she posed as her husband William's owner to get them both out of the slave states. Harrowing, tense, and eminently readable - I honestly think Part 1 should be assigned reading in every American high school in the antebellum unit.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs writing under the name Linda Brent - 1861 - writing specifically to reach white women and arguing for the need for sisterhood and solidarity between white and Black women, Jacobs writes of her childhood in slavery and how terrible it was for women and mothers even under supposedly "nice" masters including supposedly "nice" white women.

Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup - 1853 - Born a free Black man in New York, Northup was kidnapped into slavery as an adult and sold south to Louisiana. This memoir of the brutality he endured was the basis of the 2013 Oscar-winning movie.

Early 1900s Black Life and Philosophy

Slavery is of course not the only aspect of Black history, and writers in the late 1800s and early 1900s had their own concerns, experiences, and perspectives on what it meant to be Black.

Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington - 1901 - an autobiography of one of the most prominent African-American leaders and educators in the late 1800s/early 1900s, about his experiences both learning and teaching, and the power and importance of equal education. Race relations in the Reconstruction era Southern US are a major concern, and his hope that education and equal dignity could lead to mutual respect has... a long way to go still.

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois - 1903 - an iconic work of sociology and advocacy about the African-American experience as a people, class, and community. We read selections from this in Anthropology Theory but I think it should be more widely read than just assigned in college classes.

Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil by W.E.B. Du Bois - 1920 - collected essays and poems on race, religion, gender, politics, and society.

A Negro Explorer at the North Pole by Matthew Henson - 1908 - Black history doesn't have to be about racism. Matthew Henson was a sailor and explorer and was the longtime companion and expedition partner of Robert Peary. This is his adventure-memoir of the expedition that reached the North Pole. (Though his descriptions of the Indigenous Greenlandic Inuit people are... really paternalistic in uncomfortable ways even when he's trying to be supportive.)

Poetry

Standard Ebooks also compiles poetry collections, and here are some by Black authors.

Langston Hughes - 1920s - probably the most famous poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

James Weldon Johnson - early 1900s through 1920s - tends to be in a more traditionalist style than Hughes, and he preferred the term for the 1920s proliferation of African-American art "the flowering of Negro literature."

Sarah Louisa Forten Purvis - 1830s - a Black abolitionist poet, this is more of a chapbook of her work that was published in newspapers than a full book collection. There are very common early-1800s poetry themes of love, family, religion, and nostalgia, but overwhelmingly her topic was abolition and anti-slavery, appealing to a shared womanhood.

Science Fiction

This is Black history to me - Samuel Delany's first published novel, The Jewels of Aptor, a sci-fi adventure from the early 60s that encapsulates a lot of early 60s thoughts and anxieties. New agey religion, forgotten technology mistaken for magic, psychic powers, nuclear war, post-nuclear society that feels more like a fantasy kingdom than a sci-fi world until they sail for the island that still has all the high tech that no one really knows how to use... it's a quick and entertaining read.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erykah Badu Posing for her High School Senior Picture in 1989.

The Photo at the very bottom was also Taken in 1989.

Erica Abi Wright (born February 26, 1971), known professionally as Erykah Badu, is an American singer and songwriter. Influenced by R&B, soul, and hip hop, Badu rose to prominence in the late 1990s when her debut album Baduizm (1997), placed her at the forefront of the neo soul movement, earning her the nickname "Queen of Neo Soul" by music critics.

Erykah Badu was born in Dallas, Texas. Badu had her first taste of show business at the age of four, singing and dancing at the Dallas Theater Center and The Black Academy of Arts and Letters (TBAAL) under the guidance of her godmother, Gwen Hargrove, and uncle TBAAL founder Curtis King. By the age of 14, Badu was freestyling for a local radio station alongside such talent as Roy Hargrove. In her youth, she had decided to change the spelling of her first name from Erica to Erykah, as she believed her original name was a "slave name". The term "kah" signifies the inner self. She adopted the surname "Badu" because it is her favorite jazz scat sound; also, among the Akan people in Ghana, it is the term for the 10th-born child.

After graduating from Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, Badu went on to study theater at Grambling State University, a historically black university. She left the university in 1993 before graduating, to focus more fully on music. During this time, Badu took several minimum-wage jobs to support herself. She taught drama and dance to children at the South Dallas Cultural Center. Working and touring with her cousin, Robert "Free" Bradford, she recorded a 19-song demo, Country Cousins, which attracted the attention of Kedar Massenburg. He set Badu up to record a duet with D'Angelo, "Your Precious Love", and eventually signed her to a record deal with Universal Records.

Badu's career began after she opened a show for D'Angelo in 1994 in Fort Worth, leading to record label executive Kedar Massenburg signing her to Kedar Entertainment. Her first album, Baduizm, was released in February 1997. It spawned four singles: "On & On", "Appletree", "Next Lifetime" and "Otherside of the Game". The album was certified triple Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Her first live album, Live, was released in November 1997 and was certified double Platinum by the RIAA.

Her second studio album, Mama's Gun, was released in 2000. It spawned three singles: "Bag Lady", which became her first top 10 single on the Billboard Hot 100 peaking at #6, "Didn't Cha Know?" and "Cleva". The album was certified Platinum by the RIAA. Badu's third album, Worldwide Underground, was released in 2003. It generated three singles: "Love of My Life (An Ode to Hip-Hop)", "Danger" and "Back in the Day (Puff)" with 'Love' becoming her second song to reach the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at #9. The album was certified Gold by the RIAA. Badu's fourth album, New Amerykah Part One, was released in 2008. It spawned two singles: "Honey" and "Soldier". New Amerykah Part Two was released in 2010 and fared well both critically and commercially. It contained the album's lead single "Window Seat", which led to controversy.

Badu's voice has been compared to jazz singer Billie Holiday. Early in her career, Badu was recognizable for her eccentric style, which often included wearing very large and colorful headwraps. She was a core member of the Soulquarians.

As an actress, she has played a number of supporting roles in movies including Blues Brothers 2000, The Cider House Rules and House of D. She also has appeared in the documentaries Before the Music Dies and The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975.

AWARDS & NOMINATIONS

▪In 1997, Badu received twenty nominations and won three, Favorite Female Solo Single for "On & On", Favorite Female Solo Album for Baduizm and Best R&B/Soul or Rap Song of the Year for "On & On" at the Soul Train Lady of Soul Awards.

▪In 1998, Badu received fourteen nominations and won eight, including Favorite R&B/Soul or Rap New Artist at the American Music Awards; Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for "On & On" and Best R&B Album for Baduizm at the Grammy Awards; Outstanding New Artist and Outstanding Female Artist at the NAACP Image Awards; Favorite Female Soul/R&B Single for "On & On", Favorite Female Soul/R&B Album for Baduizm and Favorite New R&B/Soul or Rap New Artist for "On & On" at the Soul Train Music Awards.

▪In 2000, Badu received two nominations and won one, Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group at the Grammy Awards.

▪In 2003, Badu received twelve nominations and won two, including Video of the Year for "Love of My Life (An Ode to Hip-Hop)" at the BET Awards and Best Urban/Alternative Performance for "Love of My Life (An Ode to Hip-Hop)" at the Grammy Awards.

▪In 2008, Badu received eleven nominations and won two, including Best Director for "Honey" at the BET Awards and Best Direction in a Video for "Honey" at the MTV Video Music Awards. Overall, Badu has won 16 awards from 59 nominations.

▪In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Badu at number 115 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

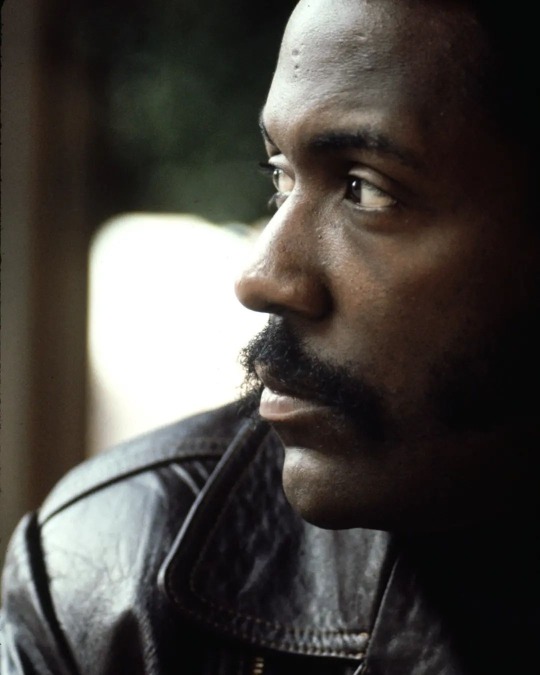

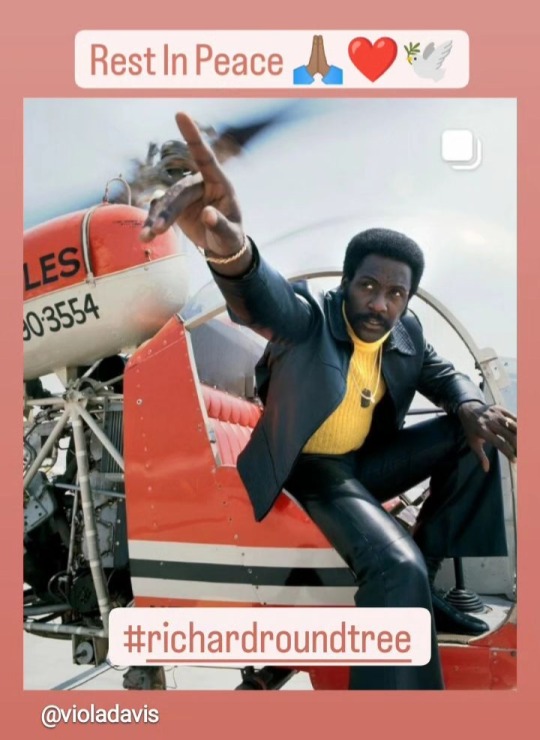

Richard Roundtree (July 9, 1942 – October 24, 2023) was an American actor, noted as being "the first black action hero" for his portrayal of private detective John Shaft in the 1971 film Shaft, and its four sequels, released between 1972 and 2019. For his performance in the original film, Roundtree was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year – Actor in 1972.

Born July 9, 1942, in New Rochelle, New York, to John Roundtree and Kathryn Watkins, Roundtree attended New Rochelle High School; graduating in 1961. During high school, Roundtree played for the school's undefeated and nationally ranked football team. Following high school, Roundtree attended Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois. Roundtree dropped out of college in 1963 to begin his acting career.

Roundtree began his professional career around 1963. Roundtree began modeling in the Ebony Fashion Fair after being scouted by Eunice W. Johnson. After his modeling success with the Fashion Fair, Roundtree began modeling for such products as Johnson Products' Duke hair grease and Salem cigarettes. In 1967, Roundtree joined the Negro Ensemble Company. His first role while a part of the company was portraying boxing legend Jack Johnson in the company's production of The Great White Hope. According to J. E. Franklin, he acted in the Off-Off-Broadway production of her play Mau Mau Room, by the Negro Ensemble Company Workshop Festival, at St. Mark's Playhouse in 1969, directed by Shauneille Perry.

Roundtree was a leading man in early 1970s blaxploitation films, his best-known role being detective John Shaft in the action movie, Shaft (1971) and its sequels, Shaft's Big Score! (1972) and Shaft in Africa (1973). Roundtree also appeared opposite Laurence Olivier and Ben Gazzara in Inchon (1981). On television, he played the slave Sam Bennett in the 1977 television series Roots and Dr. Daniel Reubens on Generations from 1989 to 1991. He played another private detective in 1984's City Heat opposite Clint Eastwood and Burt Reynolds. Although Roundtree worked throughout the 1990s, many of his films were not well-received, but he found success elsewhere in stage plays.

During that period, however, he reemerged on the small screen as a cultural icon. On September 19, 1991, Roundtree appeared in an episode of Beverly Hills, 90210 with Vivica A. Fox. The episode was "Ashes to Ashes", Roundtree playing Robinson Ashe Jr. Roundtree appeared in David Fincher's critically acclaimed 1995 movie Seven, and in the 2000 Shaft, again as John Shaft, with Samuel L. Jackson playing the title character, who is described as the original Shaft's nephew. Roundtree guest-starred in several episodes of the first season of Desperate Housewives as an amoral private detective. He also appeared in 1997's George of the Jungle and played a high-school vice-principal in the 2005 movie, Brick. His voice was utilized as the title character in the hit PlayStation game Akuji the Heartless, where Akuji must battle his way out of the depths of Hell at the bidding of the Baron.

In 1997–1998, Roundtree had a leading role as Phil Thomas in the short-lived Fox ensemble drama, 413 Hope St. He portrayed Booker T. Washington in the 1999 television movie Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters' First 100 Years.

Beginning in 2005, Roundtree appeared in the television series The Closer as Colonel D. B. Walter, U.S.M.C. (retired), the father of a sniper, and in Heroes as Simone's terminally ill father, Charles Deveaux. Next, Roundtree appeared as Eddie's father-in-law in episodes of Lincoln Heights. Roundtree then had a supporting role in the 2008 Speed Racer film as a racer-turned-commentator who is an icon and hero to Speed. He also appeared in the two-parter in Knight Rider (2008) as the father of FBI Agent Carrie Ravai, and co-starred as the father of the lead character on Being Mary Jane, which has aired on BET since 2013.

In 2019, Roundtree co-starred in the comedy film film What Men Want, and returned to the role of John Shaft in Shaft, a sequel to the 2000 film, opposite Samuel L. Jackson and Jessie Usher, who portray John Shaft II and John Shaft III, respectively. This time, Roundtree's character was described as Jackson's character's father, while acknowledging that Roundtree had pretended to be Jackson's Shaft's uncle in the 2000 movie. He also starred in the movie, Family Reunion in 2019.

Roundtree was married and divorced twice and had five children. His first marriage was to Mary Jane Grant, whom he married on November 27, 1963. Roundtree and Grant had two children before divorcing in December 1973. He dated actress and TV personality Cathy Lee Crosby shortly thereafter. Roundtree later married Karen M. Ciernia in September 1980; together they had three children. Roundtree and Ciernia divorced in 1998. Roundtree was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1993 and underwent a double mastectomy and chemotherapy.

Roundtree died of pancreatic cancer at his Los Angeles home on October 24, 2023, at the age of 81.

My deepest condolences to his family and friends. 🙏🏾❤️🕊

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Happened Today in Christian History

June 1, 1909: Rosa Jinsey Young, the valedictorian of Payne University, Selma, Alabama delivered a speech titled “Serve the People.” The nineteen-year-old sat to give her speech because she had worked so hard her body had broken under the strain. She said nothing of her suffering, however, and spoke a message of selflessness instead:

“Every vocation in life implies service. Those who are aspiring for high positions should seek to become the servants of all... The talent we possess is for the service of all. The truth we hold is the truth of all mankind... ‘He that is greatest among you shall be your servant,’ is the language of the Great Teacher. To serve is regarded as a divine privilege as well as a duty by every right-minded man... As we go from these university halls into the battle of life, where our work is to be done and our places among men to be decided, we should go in the spirit of service, with a determination to do all in our power to uplift humanity... It makes no difference how circumscribed opportunities may be, show yourself a friend to those who feel themselves friendless.”

Idealistic as her words may have been, Rosa Young turned them into reality.

Born in Rosebud, Alabama, she was the daughter of a black Methodist circuit rider, and was determined to use her education to better the lot of African-Americans. After several years teaching in Alabama towns, she yearned to open her own school. Believing that this good desire was from God, she stepped forth in faith and opened a private school near home for seven students.

In three terms, the school had grown to 215 students. However, the students’ families were poor and could pay little toward expenses. The cotton crop had fared poorly because of boll weevils and she had no money to keep the school open. After paying her sister, whom she had hired to help her, she only had a few cents left. She turned to her church, to well-to-do whites, and to anyone who might be able to help. Although she received small contributions, it was not enough.

Young went home and prayed. Then it occurred to her to write to the black educator Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute. Washington replied that he was unable to help, but advised her to contact the Board of Colored Missions of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS). According to Washington, Lutherans were doing more for African-Americans than any other denomination.

The LCMS sent pastor Nils Bakke to investigate. When he found she was telling the truth, he arranged for help. Young joined the Lutheran church and with its aid founded thirty rural schools, a high school, and a teacher training college, on whose faculty she served. She also planted Lutheran churches. Although derided for leaving the Methodists, she defended herself: “I was born and reared in gross darkness, wholly ignorant of the true meaning of the saving Gospel contained in the Holy Bible...I did not know that I could not read the Bible and pray enough to win heaven.”

Young worked tirelessly almost to the end of her 81 years, even mortgaging her own property to keep the work alive. In 1961, Concordia Theological Seminary in Springfield, Illinois awarded her an honorary Doctor of Letters degree. Ten years later, in 1971, she died, having contributed to the education of thousands of students while spreading the Gospel in Alabama. She titled her autobiography Light in the Dark Belt.

#It Happened Today in Christian History#June 1#Rosa Jinsey Young#valedictorian speech#Payne University

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

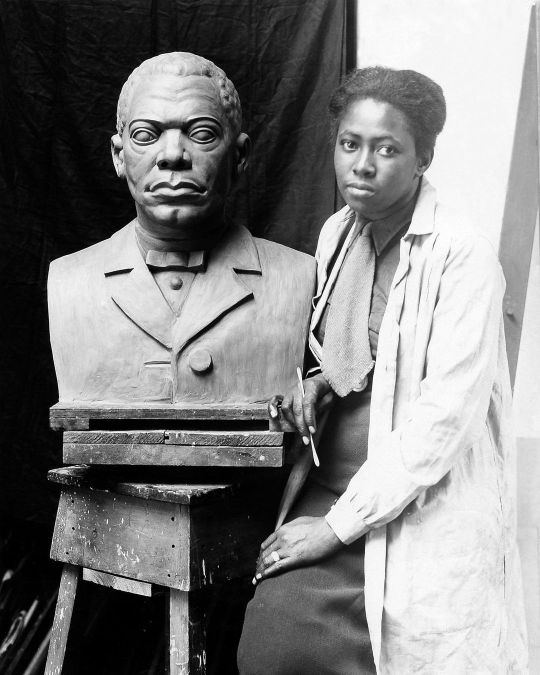

Selma Hortense Burke (December 31, 1900 – August 29, 1995) was a sculptor and a member of the Harlem Renaissance movement. She is known for a bas relief portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt that inspired the profile found on the obverse of the dime. She described herself as "a people's sculptor" and created many pieces of public art, often portraits of prominent African-American figures like Duke Ellington, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Booker T. Washington. She was awarded the Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award. She became involved with the Harlem Renaissance cultural movement through her relationship with the writer Claude McKay, with whom she shared an apartment in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood. She began teaching for the Harlem Community Arts Center under the leadership of sculptor Augusta Savage and would go on to work for the Works Progress Administration on the New Deal Federal Art Project. One of her WPA works, a bust of Booker T. Washington, was given to Frederick Douglass High School in Manhattan. She traveled to Europe twice in the 1930s, first on a Rosenwald fellowship to study sculpture in Vienna. She returned to study in Paris with Aristide Maillol. While in Paris she met Henri Matisse, who praised her work. One of her most significant works from this period is "Frau Keller", a portrait of a German-Jewish woman in response to the rising Nazi threat which would convince her to leave Europe later that year. With the onset of WWII, she chose to work in a factory as a truck driver for the Brooklyn Navy Yard. She returned to the US and won a scholarship for Columbia University, where she would receive an MFA. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #deltasigmatheta https://www.instagram.com/p/Cm1U_72rr7A/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

posting all about college on here, but i keep having thoughts..

i just feel like i'm missing something in these classes this semester. maybe it's because i'm so exhausted, or putting off a lot of my work, just putting things off. but it really feels like the learning is so surface level? i do all of the readings, i do notes, i even do a few extra things sometimes out of my own interest, and it's only when i do those extra things that i feel like i'm really learning something valuable and past the surface.

which is great and all, but i didn't really give these people my money to be the one educating myself. i could have done this kind of research when i'm bored on a saturday afternoon without splurging 10k on tuition fees.

it's mostly my american literature class giving me grief. it moves quickly. we read and talk about 1-2 authors a day, then move on after that hour is over. why are we learning about these people? what is their significance in american literature? what did they really achieve? what did their writing mean to people? how did it impact americans? why am i writing a response paper about w.e.b. du bois and booker t. washington if we never will come back to them and only learned about them for one day in a very surface level, digestible, quick manner?

overanalysis is one thing, but at least it paints a bigger picture in an american literature class.

i realize you put your own significance to these things, but what's unclear to me is, is this an english class or a history class? it's so formulaic. it feels like talking about literature to people who don't know anything about literature, or about history to people who just want to get the history down for an exam. it feels like a generalized class for high school students. i see the attempts to make it not so but the class is just organized poorly. not really digging it

i don't know, i just expected more. i feel like there should be more. i feel like there should be focus, instead of a wandering general theme. i guess it's because it's a 200 level course at a small college.

#like 10k on classes that feel like filler? really?#maybe college shouldn't have been so normalized. people now attend because they have to - because it's the most reliable path#to a successful career. and so that often means the classes are just an in-between#i'm an english major; i'm not exactly studying something with physical knowledge you must apply like engineering or vet work#but it's really such a waste. why have specific english programs if you're still going to teach them like a generalized education program?#i hope if i go for my bachelors the courses are better..

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"One of the most popular features on WDIA is 'Tan Town Jamboree,' the first program introduced by Nat Williams…The South's first Negro disk jockey, Nat is considered by both white and Negro listeners as one of the best early-morning personalities on the air when he broadcasts his 'Tan Town Coffee Club' at 6:30." – The Commercial Appeal (Memphis, TN), June 20, 1954

Nathaniel "Nat" D. Williams became the first black radio announcer in Memphis when he began broadcasting for WDIA in 1948. (This was in addition to his work as a high school teacher at Booker T. Washington High School, a columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier, a journalist for the Memphis World, and Master of Ceremonies for Amateur Night at the Old Palace Theater.) Williams was so successful at WDIA that the station switched to all-black programming and became the city's top station. After a boost to 50,000 watts, Williams and other WDIA personalities were heard across the Mississippi Delta.

Library of American Broadcasting archives | Tumblr Archive

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

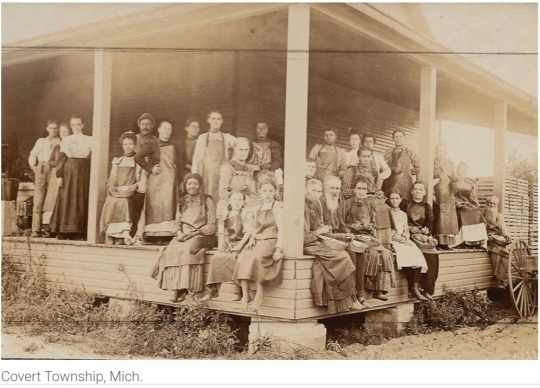

The Town That Desegregated in the 1870s: Race in America isn’t only a story of horror and oppression. By Robert L. Woodson Sr. (9- 8-2022)

Did you know that during the 1870s there was a little town in Michigan where white and black people lived together peacefully? Don’t feel too bad if you didn’t. Most schools don’t teach their students about Covert, Mich. The question is: Why not?

For far too many American schoolchildren, the only black stories they hear are ones of oppression and victimization. The Maryland Lynching Memorial Project asks students to write poetry about the black men and women lynched in the state. The group says it is working “to advance reconciliation . . . by documenting the history of racial terror lynchings.” Lynching, which victimized whites as well as blacks, is an important part of American history that shouldn’t be ignored. But should it be a primary lens through which we understand our racial history?

Teaching black students that their ancestors’ only role in American history was as targets of white brutality is both dangerous and disabling. It implies that blacks are powerless against racism, absolves them of responsibility for their choices and actions, deprives them of the belief that they can shape their own destiny, and encourages bitterness instead of hope.

What if students also learned about stories like Covert? There, men of all races flourished as equals, despite the post-Civil War chaos afflicting much of the country. “Here were religious, teetotaling Yankees, deeply accented Europeans, Indians still walking the deepest woods, and Pilgrims’ descendants, all trusting their businesses and safety to black men who judged and policed the community from lovely homes on rich farms,” historian Anna-Lisa Cox wrote in “A Stronger Kinship,” her 2006 history of the town.

The city had racially mixed communities when integration was illegal. Citizens freely elected black city officials, sheltered interracial couples and fostered school integration by declining to record the race of black students. Slavery and racial strife are hardly unique to America. But I wonder how many towns like Covert there were in 1870.

The residents of Covert resisting segregation is only one example of how racial harmony prevailed and black advancement occurred during Jim Crow. These same values of self-determination and perseverance in the face of opposition are alive and well today. We can look to the history of schools such as Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School, Atlanta’s Booker T. Washington School, and McDonough 35 High School in New Orleans. These black schools outperformed white schools by a large margin—all while their students were using hand-me-down textbooks in overcrowded and rundown buildings with half the budgets of white schools.

People are motivated to achieve when they learn about victories that are possible. If we want America’s young people to build a prosperous future together across racial and ethnic boundaries, we should teach them about our past successes, not only our past horrors.

Mr. Woodson is founder and president of the Woodson Center and author of “Red, White, and Black: Rescuing American History From Revisionists and Race Hustlers” and “Lessons From the Least of These: The Woodson Principles.”

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martin Luther King.

Martin Luther King Jr. nacido con el nombre de Michael King Jr. nace en Atlanta, Georgia, Estados Unidos, el 15 de Enero de 1929.

Fue un pastor de la iglesia bautista y un activista que hizo una gran labor social en Estados Unidos frente al movimiento de los derechos civiles para los afroestadounidenses.

Hijo del pastor de la iglesia bautista Martin Luther King Sr. y de Alberta William King. Martin Luther King Jr. tenía dos hermanos: Christine King Farris, mayor que el y Alfred Daniel William King que era menor que el..

Desde niño vivió la experiencia de una sociedad racista. Con 6 años dos niños blancos le dijeron a Martín que no estaban autorizados a jugar con el.

En 1939 cantó en el coro de su iglesia en Atlanta para la participación de la película ¨Lo que el viento se llevó¨.

King estudió en la Booker T. Washington High School de Atlanta hasta el 8 grado. No estudió el 9 grado. Con 15 años estudio en el Morehouse College, una universidad exclusiva para jóvenes negros, donde en 1948 se graduó de Sociología, se matriculó en el Crozer Theological Seminary en Chester (Pensilvania) donde se licenció en Teología en 1951. En Septiembre de 1951 empezó sus estudios de Teología Sistemática en la Universidad de Boston en la cual recibió el 5 de Junio de 1955 el titulo de Doctor en Filosofía.

Se caso el 18 de Junio de 1953 con Coretta Scott . Tuvieron 4 hijos: Yolanda King (1955), Martin Luther King III (1957), Dexter Scott King (1961) y Berenice King (1963).

King a los 25 años fue nombrado pastor de la iglesia bautista de la Avenida Dexter en Montgomery (Alabama).

El 1 de Diciembre de 1955 Rosa Park, una mujer negra, fue arrestada por haber violado las leyes racistas de la ciudad de Montgomery, al no ceder su asiento a un hombre blanco. King comenzó un boicot de autobuses con la ayuda del pastor Ralph Abernathy y de Edgard Nixon, director local de la Nacional Asociation for the Advancement of Colored People. La población negra apoyo el boicot, organizaron un sistema de viajes compartidos, Martin Luther King fue arrestado durante esta campaña. Él 30 de Enero de 1956 la casa de Luther King fue atacada con bombas incendiarias. Los boicoteadores sufrieron constantes agresiones físicas, pero el conjunto de los 40.000 negros de la ciudad siguieron su protesta llegando a caminar algunos 30 kilómetros para llegar a su puesto de trabajo. El 13 de Noviembre de 1956 termina el boicot gracias a una decisión de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos, declarando ilegal la segregación en autobuses , restaurantes, escuelas y otros sitios públicos.

King se adhirió a la filosofía de la desobediencia civil no violenta.

En 1958 mientras estaba firmando ejemplares de su libro en una tienda de Harlem, King es apuñalado por Izola Curry , una mujer negra que lo acuso de ser un jefe comunista. King se salvo por los pelos de la muerte, ya que la herida le había rozado la aorta. Perdonó a su agresora. Las protestas del boicot de autobuses duraron 381 días.

En 1959 abandonó su pastorado en Montgomery para ejercer en la iglesia baptista de Ebenezer en Atlanta

El 28 de Agosto de 1963 Martin Luther King junto a 200.000 personas que marcharon sobre Washington en apoyo de los derechos civiles, cuando llegaron al monumento de Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King pronunció su discurso más famoso ¨I have a dream¨.

En 1963 se puso al frente en Birmingham (Alabama) en una campaña a favor de los derechos civiles para lograr el censo de votantes negros y de esta manera tratar de acabar con el racismo.

Martin Luther King recibió el Premio Nobel de la Paz por su resistencia no violenta a la discriminación racial en 1964, para entonces Martín tenía 35 años de edad. Ha sido la persona mas joven en ganar el premio Nobel.

El 4 de Abril de 1968 King es asesinado en Memphis (Tennessee). James Earl Ray, un preso blanco que había escapado de la cárcel, fue arrestado por el asesinato, declarado culpable en Marzo de 1969. Fue sentenciado a 99 años de cárcel.

En el año 1986 se declaró que el 3 Lunes de Enero se convirtiera en feriado por ser el día mas próximo al nacimiento de Martin Luther King.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rockets 2023 Southeast Texas/Smith Point Launches Thursday Recap

Southeast Texas Rockets started off Thursday in Smith Point. After a rainy and stormy set up day on Wednesday, we enjoyed partly cloudy skies, and a breeze for most of the day. It was humid and steamy, and puddles riddled the site, but it was still a manageable weather situation for the launches.

The drawbacks for the day were that we started off with the Internet and the port-a-potties still MIA…

View On WordPress

#Highschoolrockets#ItISRocketScience#Launcher01#RideTheSkies#Rockets2019#rocketscience#RocketSeason#STEMRockets#SystemsGoNewMexico#SystemsGoNews#SystemsGoNM#Anahuac High School#Booker T Washington High School#Brazosport High School#Brazoswood High School#Captain Garrett#Channelview High School#Chelsea Burow#creative writing#engineering#engineers#Facebook#fredericksburg#Fredericksburg High School#Gary High School#Ginger Burow#GingerBurow#Goddard Level#Hardin-Jefferson High School#Harleton High Scool

0 notes

Photo

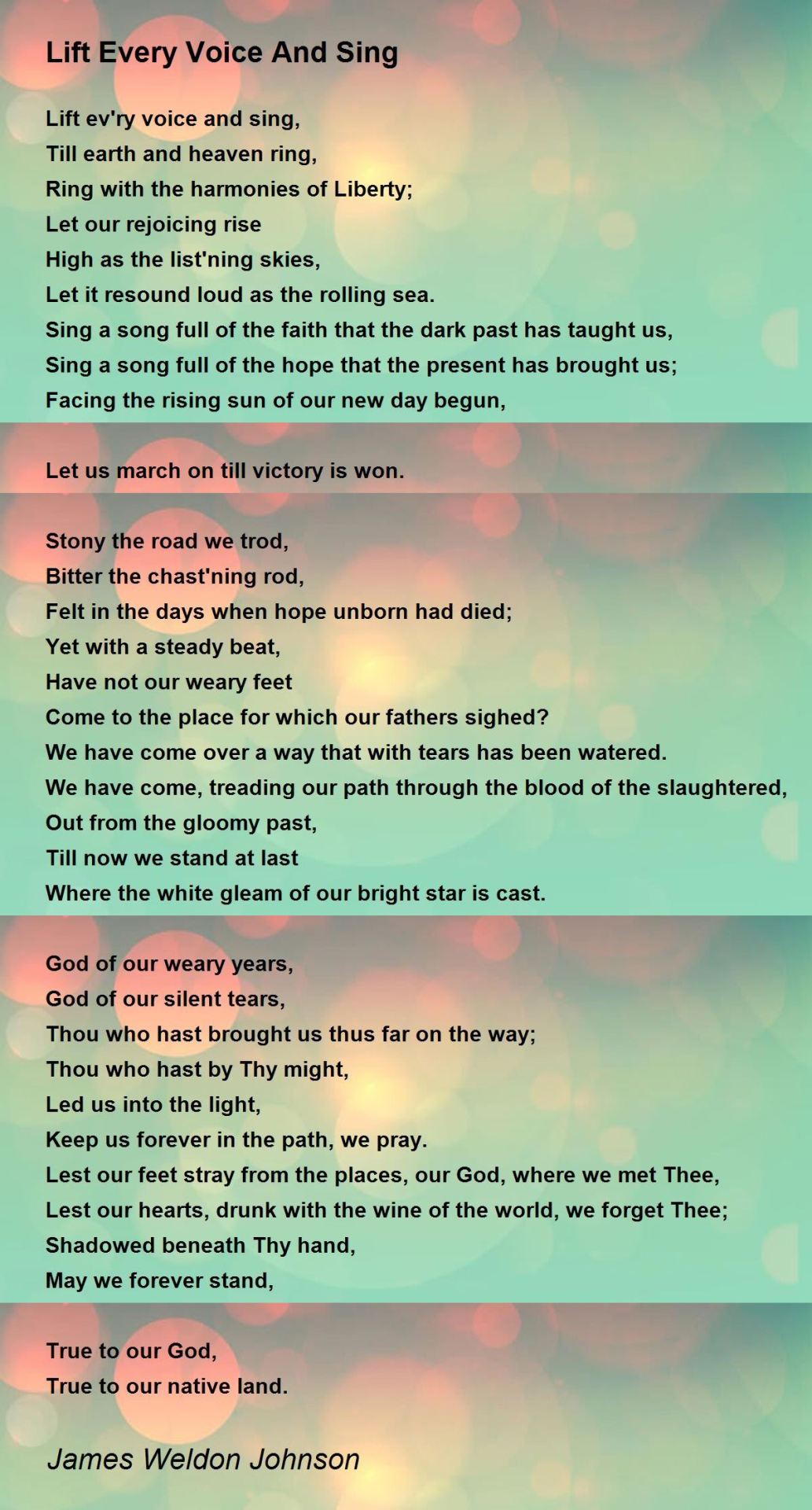

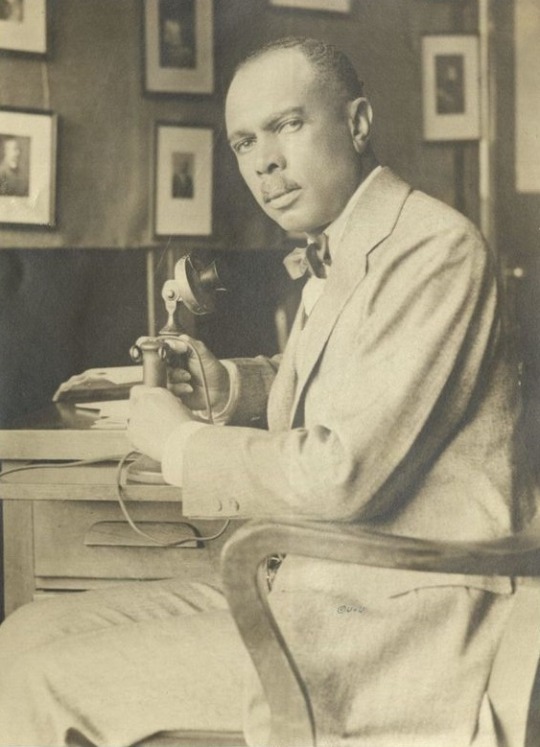

Lift Every Voice and Sing, written by James Weldon Johnson, music by John Rosamond Johnson. Brief history and meaning of the song, info about the lyricist/poet and also the composer, statement in Weldon's own words, full lyrics, official US stamp of James Weldon, and (at the bottom of the post) some music videos by: unknown artists, Alicia Keys, Stanford Talisman Alumni Virtual Choir, and Tasha Cobbs Leonard. Photos are of James Weldon and the last photo his brother John Rosamond.

I still remember all the lyrics to this Anthem. Growing up in the (back then) largest African American community of the USA, we use to sing this song at every special school event, at every church event, at any special event. For school we sang the US National Anthem (a requirement, mandatory for all US schools), then afterwards we sang the Black National Anthem (voluntarily, to us this song was specific to our ancestors' freedom)...Lift Every Voice and Sing. It was important we knew ALL the lyrics, the entire song...we sang it with pride and unity. The song was featured in our church hymn books and in our heritage history references.

This song is important to the black community, about their struggles and their hopes. From the depths of hell called slavery, to a new day of freedom and a life of liberty... There was faith and hope, there was opportunity, there was a future for themselves and their children. James Weldon Johnson wrote a vision for his people.

-

Lift Every Voice and Sing

By James Weldon Johnson

In his own words:

"A group of young men in Jacksonville, Florida, arranged to celebrate Lincoln’s birthday in 1900. My brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, and I decided to write a song to be sung at the exercises. I wrote the words and he wrote the music. Our New York publisher, Edward B. Marks, made mimeographed copies for us, and the song was taught to and sung by a chorus of five hundred colored school children.

Shortly afterwards my brother and I moved away from Jacksonville to New York, and the song passed out of our minds. But the school children of Jacksonville kept singing it; they went off to other schools and sang it; they became teachers and taught it to other children. Within twenty years it was being sung over the South and in some other parts of the country. Today the song, popularly known as the Negro National Hymn, is quite generally used.

The lines of this song repay me in an elation, almost of exquisite anguish, whenever I hear them sung by Negro children."

Full lyrics:

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who hast by Thy might

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand.

True to our God,

True to our native land.

Source:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46549/lift-every-voice-and-sing

-

"This poem was written in 1900 for the celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday at a segregated black school, and in particular to introduce Booker T. Washington–at the time the most recognized black person in the country.

Almost immediately, the audience recognized its power, and James' brother John set it to music. That version began to circulate taped in the back covers of hymnals in black churches, and it was adopted as 'the Negro National Anthem' by the NAACP in 1919.

The combination of pain, hope, faith, and a sense of steady progress, enhanced even more by the steady march of the musical setting, has made this part of the standard hymnody of many churches, both black and white."

-

"Often referred to as 'The Black National Anthem,' Lift Every Voice and Sing was a hymn written as a poem by NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson in 1900. His brother, John Rosamond Johnson (1873-1954), composed the music for the lyrics. A choir of 500 schoolchildren at the segregated Stanton School, where James Weldon Johnson was principal, first performed the song in public in Jacksonville, Florida to celebrate President Abraham Lincoln's birthday.

At the turn of the 20th century, Johnson's lyrics eloquently captured the solemn yet hopeful appeal for the liberty of Black Americans. Set against the religious invocation of God and the promise of freedom, the song was later adopted by NAACP and prominently used as a rallying cry during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s."

Lyricist: James Weldon Johnson

Forms: Hymn

Source:

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/lift-every-voice-and-sing

-

"The James Weldon Johnson stamp was issued February 2, 1988. James Weldon Johnson was a noted writer, lawyer, educator, and civil rights activist."

-

"James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) Author James Weldon Johnson published his first book of poetry in 1917 and was historian of the Harlem Renaissance."

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/james-weldon-johnson

-

"James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871 – June 26, 1938) was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920, he was the first African American to be chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novel, and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of black culture. He wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing', which later became known as the Negro National Anthem, the music being written by his younger brother, composer J. Rosamond Johnson.

Johnson was appointed under President Theodore Roosevelt as U.S. consul in Venezuela and Nicaragua for most of the period from 1906 to 1913. In 1934, he was the first African-American professor to be hired at New York University. Later in life, he was a professor of creative literature and writing at Fisk University, a historically black university."

Sources and full information:

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/james-weldon-johnson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Weldon_Johnson

-

Composer of Lift Every Voice and Sing

"John Rosamond Johnson (1873 – 1954; usually referred to as J. Rosamond Johnson) was an American composer and singer during the Harlem Renaissance. Born in Jacksonville, Florida, he had much of his career in New York City. Johnson is noted as the composer of the hymn 'Lift Every Voice and Sing'. It was first performed live by 500 Black American students from the segregated Florida Baptist Academy, Jacksonville, Florida, in 1900. The song was published by Joseph W. Stern & Co., Manhattan, New York (later the Edward B. Marks Music Company)."

"Teaming up with his brother James Weldon Johnson, James went on to compose dozens of songs, many of which appeared in Broadway musicals. He is well known today as the composer of 'Life Ev'ry Voice and Sing', a song that has played a central role as an anthem for African Americans."

"Composer, actor, and pioneer in his field, John Rosamond Johnson was one of the most successful of the early African American composers. Born on August 11, 1873 in Jacksonville, Florida, Johnson was the younger brother of prominent composer and civil rights leader James Weldon Johnson."

J. Rosamond Johnson was the younger brother of poet and activist James Weldon Johnson, who wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing". The two also worked together in causes related to the NAACP.

Sources and more information:

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/johnson-j-rosamond-1873-1954

https://songofamerica.net/composer/johnson-john-rosamond

https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200038845

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Rosamond_Johnson

-

Lift Every Voice and Sing with Lyrics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONgOH_tq7-Q

3 minutes 34 seconds video

[This is how we usually sang the song.]

Comment:

"This song was sung for the first time in 1900 by a choir of Jacksonville children for a celebration of Abraham Lincoln's birthday. James Weldon Johnson: a school principal, founder of the first Black high school in Florida, poet, lawyer, Republican, wrote it and his brother, John Rosamond Johnson, a pianist for from the Harlem Renaissance, set it to music.

These impressive men were well accomplished people and it sure seemed they took advantage of the opportunities available to them at the time." Cuahuil Tecan7

-

Alicia Keys - Lift Every Voice and Sing Performance

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DS60luWpBe0

2 minutes 25 seconds video

Comment:

"My grandma told me about this on the phone last night. Said it reminded her of the Sundays in church when they would sing this song as a congregation. She said it gave you a special feeling to sing it in unison, to sing about this unity among our people, and people would throw their heads back to sing it out, and the song would be in her heart for hours after the church service. Since my grandma attended several churches in her lifetime I asked her which one. 'All of them,' she replied." Valeria Wicker

-

Stanford Talisman Alumni Virtual Choir - Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8pGp7N9bG8

7 minutes 11 seconds video, song begins at 1:18 minutes

"We are Stanford Talisman, a group of singers on Stanford’s campus who since our origins have sung music stemming from Black liberation struggles across the world. Our alumni and current group came together to create a virtual choir of Lift Every Voice and Sing, the Black National."

"Stanford Talisman is a student a cappella group at Stanford University, dedicated to sharing stories through music. Started in 1990 by a Stanford student."

-

Tasha Cobbs Leonard - Lift Every Voice And Sing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgN35XWnPKg

3 minutes 44 seconds video

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started reading Booker T Washington's Up From Slavery for the first time since high school and I am already a fan of what the editor has to say in the preface.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Up From Slavery: Part 18

of 18 parts. Chapter XVII. Last Words

Before going to Europe some events came into my life which were great surprises to me. In fact, my whole life has largely been one of surprises. I believe that any man's life will be filled with constant, unexpected encouragements of this kind if he makes up his mind to do his level best each day of his life—that is, tries to make each day reach as nearly as possible the high-water mark of pure, unselfish, useful living.

I pity the man, black or white, who has never experienced the joy and satisfaction that come to one by reason of an effort to assist in making some one else more useful and more happy.

Six months before he died, and nearly a year after he had been stricken with paralysis, General Armstrong expressed a wish to visit Tuskegee again before he passed away. Notwithstanding the fact that he had lost the use of his limbs to such an extent that he was practically helpless, his wish was gratified, and he was brought to Tuskegee. The owners of the Tuskegee Railroad, white men living in the town, offered to run a special train, without cost, out of the main station—Chehaw, five miles away—to meet him. He arrived on the school grounds about nine o'clock in the evening. Some one had suggested that we give the General a "pine-knot torchlight reception." This plan was carried out, and the moment that his carriage entered the school grounds he began passing between two lines of lighted and waving "fat pine" wood knots held by over a thousand students and teachers. The whole thing was so novel and surprising that the General was completely overcome with happiness. He remained a guest in my home for nearly two months, and, although almost wholly without the use of voice or limb, he spent nearly every hour in devising ways and means to help the South. Time and time again he said to me, during this visit, that it was not only the duty of the country to assist in elevating the Negro of the South, but the poor white man as well. At the end of his visit I resolved anew to devote myself more earnestly than ever to the cause which was so near his heart. I said that if a man in his condition was willing to think, work, and act, I should not be wanting in furthering in every possible way the wish of his heart.

The death of General Armstrong, a few weeks later, gave me the privilege of getting acquainted with one of the finest, most unselfish, and most attractive men that I have ever come in contact with. I refer to the Rev. Dr. Hollis B. Frissell, now the Principal of the Hampton Institute, and General Armstrong's successor. Under the clear, strong, and almost perfect leadership of Dr. Frissell, Hampton has had a career of prosperity and usefulness that is all that the General could have wished for. It seems to be the constant effort of Dr. Frissell to hide his own great personality behind that of General Armstrong—to make himself of "no reputation" for the sake of the cause.

More than once I have been asked what was the greatest surprise that ever came to me. I have little hesitation in answering that question. It was the following letter, which came to me one Sunday morning when I was sitting on the veranda of my home at Tuskegee, surrounded by my wife and three children:—

Harvard University, Cambridge, May 28, 1896.

President Booker T. Washington,

My Dear Sir: Harvard University desired to confer on you at the approaching Commencement an honorary degree; but it is our custom to confer degrees only on gentlemen who are present. Our Commencement occurs this year on June 24, and your presence would be desirable from about noon till about five o'clock in the afternoon. Would it be possible for you to be in Cambridge on that day?

Believe me, with great regard,

Very truly yours,

Charles W. Eliot.

This was a recognition that had never in the slightest manner entered into my mind, and it was hard for me to realize that I was to be honoured by a degree from the oldest and most renowned university in America. As I sat upon my veranda, with this letter in my hand, tears came into my eyes. My whole former life—my life as a slave on the plantation, my work in the coal-mine, the times when I was without food and clothing, when I made my bed under a sidewalk, my struggles for an education, the trying days I had had at Tuskegee, days when I did not know where to turn for a dollar to continue the work there, the ostracism and sometimes oppression of my race,—all this passed before me and nearly overcame me.

I had never sought or cared for what the world calls fame. I have always looked upon fame as something to be used in accomplishing good. I have often said to my friends that if I can use whatever prominence may have come to me as an instrument with which to do good, I am content to have it. I care for it only as a means to be used for doing good, just as wealth may be used. The more I come into contact with wealthy people, the more I believe that they are growing in the direction of looking upon their money simply as an instrument which God has placed in their hand for doing good with. I never go to the office of Mr. John D. Rockefeller, who more than once has been generous to Tuskegee, without being reminded of this. The close, careful, and minute investigation that he always makes in order to be sure that every dollar that he gives will do the most good—an investigation that is just as searching as if he were investing money in a business enterprise—convinces me that the growth in this direction is most encouraging.

At nine o'clock, on the morning of June 24, I met President Eliot, the Board of Overseers of Harvard University, and the other guests, at the designated place on the university grounds, for the purpose of being escorted to Sanders Theatre, where the Commencement exercises were to be held and degrees conferred. Among others invited to be present for the purpose of receiving a degree at this time were General Nelson A. Miles, Dr. Bell, the inventor of the Bell telephone, Bishop Vincent, and the Rev. Minot J. Savage. We were placed in line immediately behind the President and the Board of Overseers, and directly afterward the Governor of Massachusetts, escorted by the Lancers, arrived and took his place in the line of march by the side of President Eliot. In the line there were also various other officers and professors, clad in cap and gown. In this order we marched to Sanders Theatre, where, after the usual Commencement exercises, came the conferring of the honorary degrees. This, it seems, is always considered the most interesting feature at Harvard. It is not known, until the individuals appear, upon whom the honorary degrees are to be conferred, and those receiving these honours are cheered by the students and others in proportion to their popularity. During the conferring of the degrees excitement and enthusiasm are at the highest pitch.

When my name was called, I rose, and President Eliot, in beautiful and strong English, conferred upon me the degree of Master of Arts. After these exercises were over, those who had received honorary degrees were invited to lunch with the President. After the lunch we were formed in line again, and were escorted by the Marshal of the day, who that year happened to be Bishop William Lawrence, through the grounds, where, at different points, those who had been honoured were called by name and received the Harvard yell. This march ended at Memorial Hall, where the alumni dinner was served. To see over a thousand strong men, representing all that is best in State, Church, business, and education, with the glow and enthusiasm of college loyalty and college pride,—which has, I think, a peculiar Harvard flavour,—is a sight that does not easily fade from memory.

Among the speakers after dinner were President Eliot, Governor Roger Wolcott, General Miles, Dr. Minot J. Savage, the Hon. Henry Cabot Lodge, and myself. When I was called upon, I said, among other things:—

It would in some measure relieve my embarrassment if I could, even in a slight degree, feel myself worthy of the great honour which you do me to-day. Why you have called me from the Black Belt of the South, from among my humble people, to share in the honours of this occasion, is not for me to explain; and yet it may not be inappropriate for me to suggest that it seems to me that one of the most vital questions that touch our American life is how to bring the strong, wealthy, and learned into helpful touch with the poorest, most ignorant, and humblest, and at the same time make one appreciate the vitalizing, strengthening influence of the other. How shall we make the mansion on yon Beacon Street feel and see the need of the spirits in the lowliest cabin in Alabama cotton-fields or Louisiana sugar-bottoms? This problem Harvard University is solving, not by bringing itself down, but by bringing the masses up.

If my life in the past has meant anything in the lifting up of my people and the bringing about of better relations between your race and mine, I assure you from this day it will mean doubly more. In the economy of God there is but one standard by which an individual can succeed—there is but one for a race. This country demands that every race shall measure itself by the American standard. By it a race must rise or fall, succeed or fail, and in the last analysis mere sentiment counts for little. During the next half-century and more, my race must continue passing through the severe American crucible. We are to be tested in our patience, our forbearance, our perseverance, our power to endure wrong, to withstand temptations, to economize, to acquire and use skill; in our ability to compete, to succeed in commerce, to disregard the superficial for the real, the appearance for the substance, to be great and yet small, learned and yet simple, high and yet the servant of all.

As this was the first time that a New England university had conferred an honorary degree upon a Negro, it was the occasion of much newspaper comment throughout the country. A correspondent of a New York paper said:—

When the name of Booker T. Washington was called, and he arose to acknowledge and accept, there was such an outburst of applause as greeted no other name except that of the popular soldier patriot, General Miles. The applause was not studied and stiff, sympathetic and condoling; it was enthusiasm and admiration. Every part of the audience from pit to gallery joined in, and a glow covered the cheeks of those around me, proving sincere appreciation of the rising struggle of an ex-slave and the work he has accomplished for his race.

A Boston paper said, editorially:—

In conferring the honorary degree of Master of Arts upon the Principal of Tuskegee Institute, Harvard University has honoured itself as well as the object of this distinction. The work which Professor Booker T. Washington has accomplished for the education, good citizenship, and popular enlightenment in his chosen field of labour in the South entitles him to rank with our national benefactors. The university which can claim him on its list of sons, whether in regular course or honoris causa, may be proud.

It has been mentioned that Mr. Washington is the first of his race to receive an honorary degree from a New England university. This, in itself, is a distinction. But the degree was not conferred because Mr. Washington is a coloured man, or because he was born in slavery, but because he has shown, by his work for the elevation of the people of the Black Belt of the South, a genius and a broad humanity which count for greatness in any man, whether his skin be white or black.

Another Boston paper said:—

It is Harvard which, first among New England colleges, confers an honorary degree upon a black man. No one who has followed the history of Tuskegee and its work can fail to admire the courage, persistence, and splendid common sense of Booker T. Washington. Well may Harvard honour the ex-slave, the value of whose services, alike to his race and country, only the future can estimate.

The correspondent of the New York Times wrote:—

All the speeches were enthusiastically received, but the coloured man carried off the oratorical honours, and the applause which broke out when he had finished was vociferous and long-continued.

Soon after I began work at Tuskegee I formed a resolution, in the secret of my heart, that I would try to build up a school that would be of so much service to the country that the President of the United States would one day come to see it. This was, I confess, rather a bold resolution, and for a number of years I kept it hidden in my own thoughts, not daring to share it with any one.

In November, 1897, I made the first move in this direction, and that was in securing a visit from a member of President McKinley's Cabinet, the Hon. James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture. He came to deliver an address at the formal opening of the Slater-Armstrong Agricultural Building, our first large building to be used for the purpose of giving training to our students in agriculture and kindred branches.

In the fall of 1898 I heard that President McKinley was likely to visit Atlanta, Georgia, for the purpose of taking part in the Peace Jubilee exercises to be held there to commemorate the successful close of the Spanish-American war. At this time I had been hard at work, together with our teachers, for eighteen years, trying to build up a school that we thought would be of service to the Nation, and I determined to make a direct effort to secure a visit from the President and his Cabinet. I went to Washington, and I was not long in the city before I found my way to the White House. When I got there I found the waiting rooms full of people, and my heart began to sink, for I feared there would not be much chance of my seeing the President that day, if at all. But, at any rate, I got an opportunity to see Mr. J. Addison Porter, the secretary to the President, and explained to him my mission. Mr. Porter kindly sent my card directly to the President, and in a few minutes word came from Mr. McKinley that he would see me.

How any man can see so many people of all kinds, with all kinds of errands, and do so much hard work, and still keep himself calm, patient, and fresh for each visitor in the way that President McKinley does, I cannot understand. When I saw the President he kindly thanked me for the work which we were doing at Tuskegee for the interests of the country. I then told him, briefly, the object of my visit. I impressed upon him the fact that a visit from the Chief Executive of the Nation would not only encourage our students and teachers, but would help the entire race. He seemed interested, but did not make a promise to go to Tuskegee, for the reason that his plans about going to Atlanta were not then fully made; but he asked me to call the matter to his attention a few weeks later.

By the middle of the following month the President had definitely decided to attend the Peace Jubilee at Atlanta. I went to Washington again and saw him, with a view of getting him to extend his trip to Tuskegee. On this second visit Mr. Charles W. Hare, a prominent white citizen of Tuskegee, kindly volunteered to accompany me, to reenforce my invitation with one from the white people of Tuskegee and the vicinity.

Just previous to my going to Washington the second time, the country had been excited, and the coloured people greatly depressed, because of several severe race riots which had occurred at different points in the South. As soon as I saw the President, I perceived that his heart was greatly burdened by reason of these race disturbances. Although there were many people waiting to see him, he detained me for some time, discussing the condition and prospects of the race. He remarked several times that he was determined to show his interest and faith in the race, not merely in words, but by acts. When I told him that I thought that at that time scarcely anything would go farther in giving hope and encouragement to the race than the fact that the President of the Nation would be willing to travel one hundred and forty miles out of his way to spend a day at a Negro institution, he seemed deeply impressed.

While I was with the President, a white citizen of Atlanta, a Democrat and an ex-slaveholder, came into the room, and the President asked his opinion as to the wisdom of his going to Tuskegee. Without hesitation the Atlanta man replied that it was the proper thing for him to do. This opinion was reenforced by that friend of the race, Dr. J.L.M. Curry. The President promised that he would visit our school on the 16th of December.

When it became known that the President was going to visit our school, the white citizens of the town of Tuskegee—a mile distant from the school—were as much pleased as were our students and teachers. The white people of this town, including both men and women, began arranging to decorate the town, and to form themselves into committees for the purpose of cooperating with the officers of our school in order that the distinguished visitor might have a fitting reception. I think I never realized before this how much the white people of Tuskegee and vicinity thought of our institution. During the days when we were preparing for the President's reception, dozens of these people came to me and said that, while they did not want to push themselves into prominence, if there was anything they could do to help, or to relieve me personally, I had but to intimate it and they would be only too glad to assist. In fact, the thing that touched me almost as deeply as the visit of the President itself was the deep pride which all classes of citizens in Alabama seemed to take in our work.

The morning of December 16th brought to the little city of Tuskegee such a crowd as it had never seen before. With the President came Mrs. McKinley and all of the Cabinet officers but one; and most of them brought their wives or some members of their families. Several prominent generals came, including General Shafter and General Joseph Wheeler, who were recently returned from the Spanish-American war. There was also a host of newspaper correspondents. The Alabama Legislature was in session in Montgomery at this time. This body passed a resolution to adjourn for the purpose of visiting Tuskegee. Just before the arrival of the President's party the Legislature arrived, headed by the governor and other state officials.

The citizens of Tuskegee had decorated the town from the station to the school in a generous manner. In order to economize in the matter of time, we arranged to have the whole school pass in review before the President. Each student carried a stalk of sugar-cane with some open bolls of cotton fastened to the end of it. Following the students the work of all departments of the school passed in review, displayed on "floats" drawn by horses, mules, and oxen. On these floats we tried to exhibit not only the present work of the school, but to show the contrasts between the old methods of doing things and the new. As an example, we showed the old method of dairying in contrast with the improved methods, the old methods of tilling the soil in contrast with the new, the old methods of cooking and housekeeping in contrast with the new. These floats consumed an hour and a half of time in passing.

In his address in our large, new chapel, which the students had recently completed, the President said, among other things:—

To meet you under such pleasant auspices and to have the opportunity of a personal observation of your work is indeed most gratifying. The Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute is ideal in its conception, and has already a large and growing reputation in the country, and is not unknown abroad. I congratulate all who are associated in this undertaking for the good work which it is doing in the education of its students to lead lives of honour and usefulness, thus exalting the race for which it was established.

Nowhere, I think, could a more delightful location have been chosen for this unique educational experiment, which has attracted the attention and won the support even of conservative philanthropists in all sections of the country.

To speak of Tuskegee without paying special tribute to Booker T. Washington's genius and perseverance would be impossible. The inception of this noble enterprise was his, and he deserves high credit for it. His was the enthusiasm and enterprise which made its steady progress possible and established in the institution its present high standard of accomplishment. He has won a worthy reputation as one of the great leaders of his race, widely known and much respected at home and abroad as an accomplished educator, a great orator, and a true philanthropist.

The Hon. John D. Long, the Secretary of the Navy, said in part:—

I cannot make a speech to-day. My heart is too full—full of hope, admiration, and pride for my countrymen of both sections and both colours. I am filled with gratitude and admiration for your work, and from this time forward I shall have absolute confidence in your progress and in the solution of the problem in which you are engaged.

The problem, I say, has been solved. A picture has been presented to-day which should be put upon canvas with the pictures of Washington and Lincoln, and transmitted to future time and generations—a picture which the press of the country should spread broadcast over the land, a most dramatic picture, and that picture is this: The President of the United States standing on this platform; on one side the Governor of Alabama, on the other, completing the trinity, a representative of a race only a few years ago in bondage, the coloured President of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute.

God bless the President under whose majesty such a scene as that is presented to the American people. God bless the state of Alabama, which is showing that it can deal with this problem for itself. God bless the orator, philanthropist, and disciple of the Great Master—who, if he were on earth, would be doing the same work—Booker T. Washington.

Postmaster General Smith closed the address which he made with these words:—

We have witnessed many spectacles within the last few days. We have seen the magnificent grandeur and the magnificent achievements of one of the great metropolitan cities of the South. We have seen heroes of the war pass by in procession. We have seen floral parades. But I am sure my colleagues will agree with me in saying that we have witnessed no spectacle more impressive and more encouraging, more inspiring for our future, than that which we have witnessed here this morning.

Some days after the President returned to Washington I received the letter which follows:—

Executive Mansion, Washington, Dec. 23, 1899.

Dear Sir: By this mail I take pleasure in sending you engrossed copies of the souvenir of the visit of the President to your institution. These sheets bear the autographs of the President and the members of the Cabinet who accompanied him on the trip. Let me take this opportunity of congratulating you most heartily and sincerely upon the great success of the exercises provided for and entertainment furnished us under your auspices during our visit to Tuskegee. Every feature of the programme was perfectly executed and was viewed or participated in with the heartiest satisfaction by every visitor present. The unique exhibition which you gave of your pupils engaged in their industrial vocations was not only artistic but thoroughly impressive. The tribute paid by the President and his Cabinet to your work was none too high, and forms a most encouraging augury, I think, for the future prosperity of your institution. I cannot close without assuring you that the modesty shown by yourself in the exercises was most favourably commented upon by all the members of our party.

With best wishes for the continued advance of your most useful and patriotic undertaking, kind personal regards, and the compliments of the season, believe me, always,

Very sincerely yours,

John Addison Porter,

Secretary to the President.

To President Booker T. Washington, Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, Tuskegee, Ala.

Twenty years have now passed since I made the first humble effort at Tuskegee, in a broken-down shanty and an old hen-house, without owning a dollar's worth of property, and with but one teacher and thirty students. At the present time the institution owns twenty-three hundred acres of land, one thousand of which are under cultivation each year, entirely by student labour. There are now upon the grounds, counting large and small, sixty-six buildings; and all except four of these have been almost wholly erected by the labour of our students. While the students are at work upon the land and in erecting buildings, they are taught, by competent instructors, the latest methods of agriculture and the trades connected with building.

There are in constant operation at the school, in connection with thorough academic and religious training, thirty industrial departments. All of these teach industries at which our men and women can find immediate employment as soon as they leave the institution. The only difficulty now is that the demand for our graduates from both white and black people in the South is so great that we cannot supply more than one-half the persons for whom applications come to us. Neither have we the buildings nor the money for current expenses to enable us to admit to the school more than one-half the young men and women who apply to us for admission.

In our industrial teaching we keep three things in mind: first, that the student shall be so educated that he shall be enabled to meet conditions as they exist now, in the part of the South where he lives—in a word, to be able to do the thing which the world wants done; second, that every student who graduates from the school shall have enough skill, coupled with intelligence and moral character, to enable him to make a living for himself and others; third, to send every graduate out feeling and knowing that labour is dignified and beautiful—to make each one love labour instead of trying to escape it. In addition to the agricultural training which we give to young men, and the training given to our girls in all the usual domestic employments, we now train a number of girls in agriculture each year. These girls are taught gardening, fruit-growing, dairying, bee-culture, and poultry-raising.

While the institution is in no sense denominational, we have a department known as the Phelps Hall Bible Training School, in which a number of students are prepared for the ministry and other forms of Christian work, especially work in the country districts. What is equally important, each one of the students works half of each day at some industry, in order to get skill and the love of work, so that when he goes out from the institution he is prepared to set the people with whom he goes to labour a proper example in the matter of industry.

The value of our property is now over $700,000. If we add to this our endowment fund, which at present is $1,000,000, the value of the total property is now $1,700,000. Aside from the need for more buildings and for money for current expenses, the endowment fund should be increased to at least $3,000,000. The annual current expenses are now about $150,000. The greater part of this I collect each year by going from door to door and from house to house. All of our property is free from mortgage, and is deeded to an undenominational board of trustees who have the control of the institution.

From thirty students the number has grown to fourteen hundred, coming from twenty-seven states and territories, from Africa, Cuba, Porto Rico, Jamaica, and other foreign countries. In our departments there are one hundred and ten officers and instructors; and if we add the families of our instructors, we have a constant population upon our grounds of not far from seventeen hundred people.

I have often been asked how we keep so large a body of people together, and at the same time keep them out of mischief. There are two answers: that the men and women who come to us for an education are in earnest; and that everybody is kept busy. The following outline of our daily work will testify to this:—

5 a.m., rising bell;

5.50 a.m., warning breakfast bell;

6 a.m., breakfast bell;

6.20 a.m., breakfast over;

6.20 to 6.50 a.m., rooms are cleaned;

6.50, work bell;

7.30, morning study hours;

8.20, morning school bell;

8.25, inspection of young men's toilet in ranks;

8.40, devotional exercises in chapel;

8.55, "five minutes with the daily news;"

9 a.m., class work begins;

12, class work closes;

12.15 p.m., dinner;

1 p.m., work bell;

1.30 p.m., class work begins;

3.30 p.m., class work ends;

5.30 p.m., bell to "knock off" work;

6 p.m., supper;

7.10 p.m., evening prayers;

7.30 p.m., evening study hours;

8.45 p.m., evening study hour closes;

9.20 p.m., warning retiring bell;

9.30 p.m., retiring bell.

We try to keep constantly in mind the fact that the worth of the school is to be judged by its graduates. Counting those who have finished the full course, together with those who have taken enough training to enable them to do reasonably good work, we can safely say that at least six thousand men and women from Tuskegee are now at work in different parts of the South; men and women who, by their own example or by direct efforts, are showing the masses of our race now to improve their material, educational, and moral and religious life. What is equally important, they are exhibiting a degree of common sense and self-control which is causing better relations to exist between the races, and is causing the Southern white man to learn to believe in the value of educating the men and women of my race. Aside from this, there is the influence that is constantly being exerted through the mothers' meeting and the plantation work conducted by Mrs. Washington.

Wherever our graduates go, the changes which soon begin to appear in the buying of land, improving homes, saving money, in education, and in high moral characters are remarkable. Whole communities are fast being revolutionized through the instrumentality of these men and women.

Ten years ago I organized at Tuskegee the first Negro Conference. This is an annual gathering which now brings to the school eight or nine hundred representative men and women of the race, who come to spend a day in finding out what the actual industrial, mental, and moral conditions of the people are, and in forming plans for improvement. Out from this central Negro Conference at Tuskegee have grown numerous state and local conferences which are doing the same kind of work. As a result of the influence of these gatherings, one delegate reported at the last annual meeting that ten families in his community had bought and paid for homes. On the day following the annual Negro Conference, there is the "Workers' Conference." This is composed of officers and teachers who are engaged in educational work in the larger institutions in the South. The Negro Conference furnishes a rare opportunity for these workers to study the real condition of the rank and file of the people.

In the summer of 1900, with the assistance of such prominent coloured men as Mr. T. Thomas Fortune, who has always upheld my hands in every effort, I organized the National Negro Business League, which held its first meeting in Boston, and brought together for the first time a large number of the coloured men who are engaged in various lines of trade or business in different parts of the United States. Thirty states were represented at our first meeting. Out of this national meeting grew state and local business leagues.

In addition to looking after the executive side of the work at Tuskegee, and raising the greater part of the money for the support of the school, I cannot seem to escape the duty of answering at least a part of the calls which come to me unsought to address Southern white audiences and audiences of my own race, as well as frequent gatherings in the North. As to how much of my time is spent in this way, the following clipping from a Buffalo (N.Y.) paper will tell. This has reference to an occasion when I spoke before the National Educational Association in that city.