#Brut Grotesque

Text

Sonoma

#Sonoma#Bakery#shop#pickup#artisan#locations#Australia#bread#croissant#type#typeface#font#Brut Grotesque#Typewriter Condensed#2023#Week 41#website#web design#inspire#inspiration#happywebdesign

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

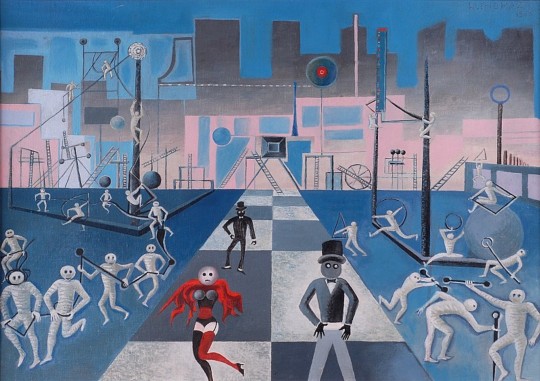

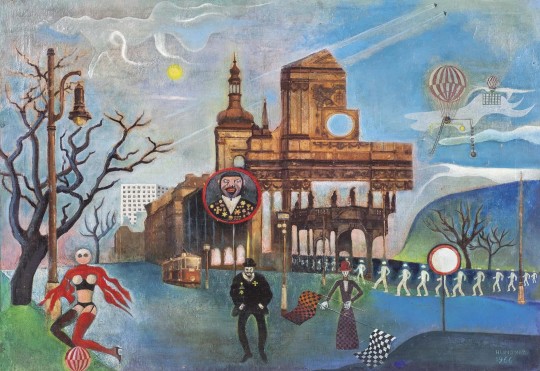

Josef Hlinomaz (1914-1978) — A Painstaking Electrification of Space [oil on panel, 1966]

192 notes

·

View notes

Photo

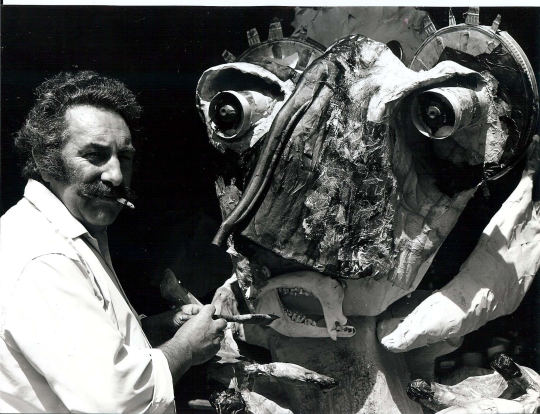

Alain Bourbonnais (1925 - 1988) was a French architect , designer and collector.

He is known for having built up the extraordinary art collection gathered at La Fabuloserie since 1983.

In 1972 Alain Bourbonnais decided to open the Atelier Jacob to present his own collection of art brut. In agreement with Jean Dubuffet, he calls this art “hors-les-normes”. In 1983, he created La Fabuloserie museum on a property he acquired in Dicy (Yonne), now managed by his daughters Sophie and Agnès Bourbonnais.

This private museum houses, among other things, the Turbulents by Alain Bourbonnais: monumental sculptures of grotesque, articulated and variegated characters influenced by carnival creatures and popular festivals.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

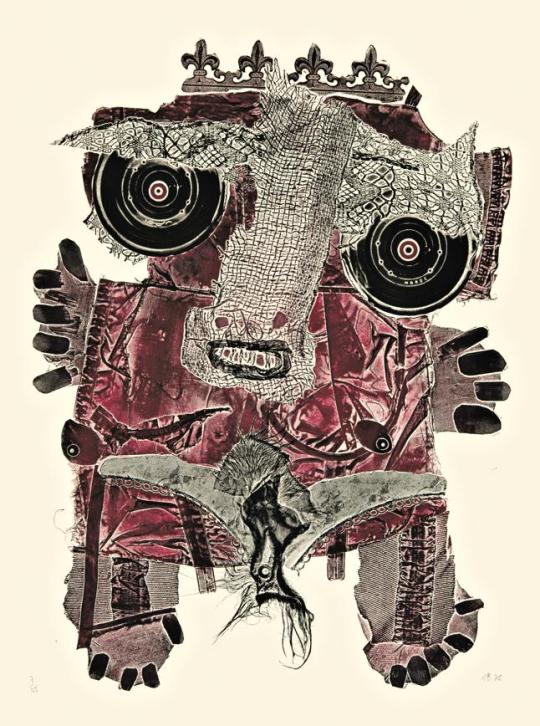

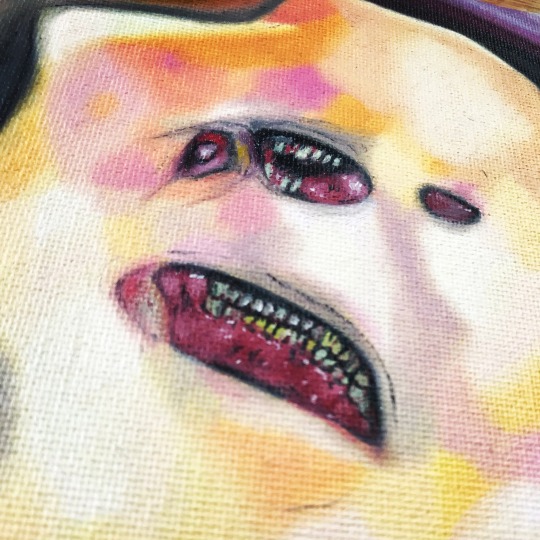

“Lady Papillon"(British girl) 2024

18”X24”

•Alejandro Caiazza’s Brut, Outsider, Folk, Neo-expressionist pieces balance the whimsical with the grotesque. Caiazza creates expressive figures in a vivid, textural style.

“The naive but sharply witty characters populating Caiazza’s images are reflected squarely in the behavior of society: ugly painted faces reflect ugly behaviors.”

• Alejandro Caiazza’s paintings often portray a humorous subject matter that rests on a dark palette and foundation, engaging the viewer in the silliness of the present with a warning of what is to come. Initially appearing whimsical and delightful with a child-like innocence, the work of Caiazza on closer inspection reveals much deeper and darker aspects of our human condition: drawing on inspiration from daily life and emotions, the uncertainty of social upheavals, and political strife.

*Based in NYC, Alejandro Caiazza’s artwork is currently exhibited at Van Der Plas Gallery (New York City) For more information call: 212.227.8983 #nycgallery

#AlejandroCaiazza #VanDerPlasGallery #newpaintings #newAmericanPaintings #theoutsiders #contemporypaintings #newyorkcity #theoutsider #primitiveART #artdealer #Artcollector #outsiderartist #jerrysaltz #violence #grotesque #NYARTBEAT #brut #NewYorkArtBeat #outsiderart #collectors #artlowereastside #LowerEastSide #expressionism #newfigurative #ArtBrut #voyagemia #newamericanpaintings #newamericanpainters #newamericana

1 note

·

View note

Text

This painting is shit but I’ll post it here anyway because it needs to be free

#red painting#my art#sickro0m#art brut#red#art#illustration#horror#creepy art#creepy#grotesque#macabre

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

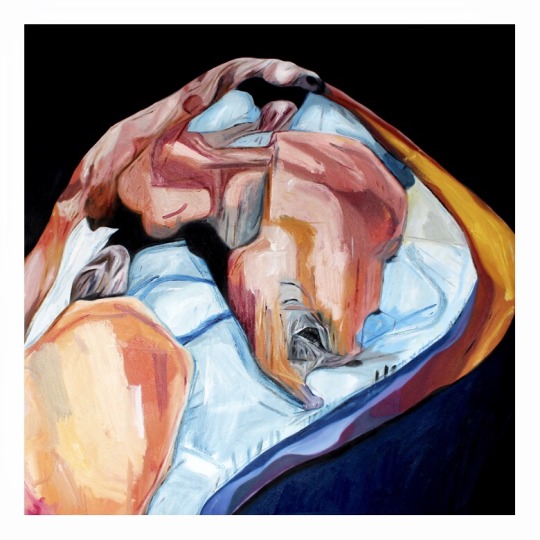

Bed. Oil on canvas, 80x80cm, 2019.

www.carpmatthew.com

#art#hell#love#carpmatthew#artists on tumblr#artist#london#gallery#contemporary art#art brut#art scene#politics#faith#mortality#horror#farce#outsider art#low brow art#emerging artist#grotesque#flesh#bed#surrealism

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

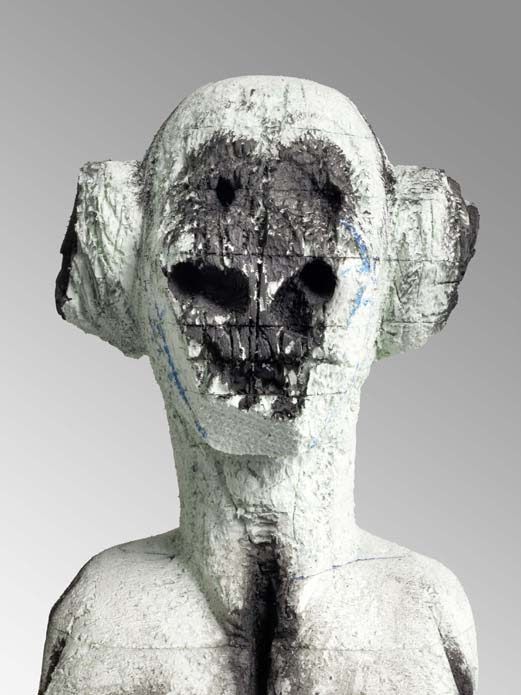

Huma Bhabha (b. 1962)

What is Love, 2013. Cork, styrofoam, acrylic paint, oil, stick, lipstick. 203 x 30,5 x 36 cm. Courtesy of VW (VeneKlasen/Werner)

The synthesis of science fiction, modernism and “pop” with the distant past underlies much of Bhabha’s work as evidenced in her totems and fragmented figures. Archaeology is an important touchstone for the artist, referencing the raw landscapes of her native Karachi to Robert Smithson’s Monuments of Passaic and the post-industrial cities of upstate New York, where she now resides. --Anti-Utopias, May 1, 2014

#Huma Bhabha#sculpture#Pakistan#contemporary#grotesque#brut#cut#destruction#head#portrait#defaced#monsters#exhibition

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The nightmarish dolls of French outsider artist Michel Nedjar, made from fabric scraps coated with mud and blood, c.1976-82. Resembling mutilated bodies and burnt corpses, Nedjar's haunting dolls are meditations on the horrors of the Holocaust. The self-taught artist was born in France in the aftermath of WWII, to a family of Jewish immigrants whose close relatives had largely been wiped out in the concentration camps.As a child, he developed an obsession with textiles and would accompany his grandmother selling rags at Paris flea markets. Following a period of deep depression in the late 1970s, Nedjar began making these grotesque dolls from scraps of fabric coated with mud and blood, as a way of confronting his grief, terror and rage about his family's tragic history.”

Collection of L'Art Brut in Lausanne, France.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

https://binu-binu.com/

#BINU BINU#soap house#soaps#shop#home scents#bath accessories#skincare#Korean public bath#typography#type#typeface#font#Brut Grotesque#Favorit Pro#2022#Week 27#website#web design#inspire#inspiration#happywebdesign

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Josef Hlinomaz (1914-1978) — Terminal Station [oil on canvas, 1966]

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

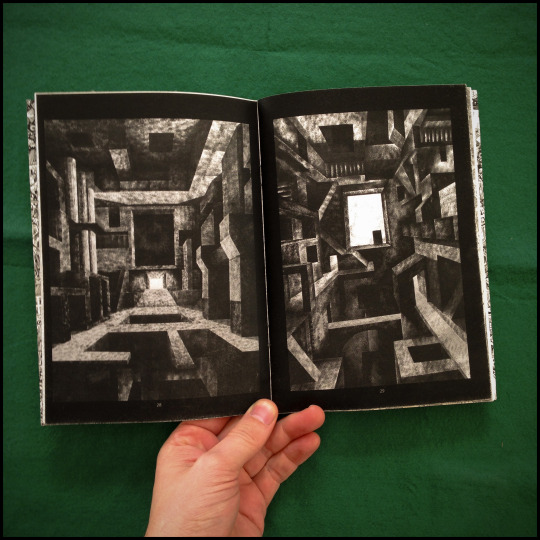

Bonjour,

Il y a quelques années, j'ai pu participer à un fanzine édité par le collectif Sous Vide installé à Grenoble.

Je ne me souviens plus exactement, ça devait être en 2014, à cette époque pas si lointaine, je dessinais encore dans un style très inspiré de la BD, au feutre fin noir. Je dessinais de manière obsessionnelle des environnements très glauques et cauchemardesques. Je m'y sentais un peu coincé aussi.

En consultant les travaux de dessin des autres auteurs présents pour ce fanzine, j'ai constaté que nous avions une esthétique commune assez proche, quelque chose de brut, d'expression crue et souvent violente.

J'ai eu une réaction assez vive, que je n'analyse pas encore complètement mais je voulais changer tout dans mon dessin. Je ne voulais plus de cette angoisse visuelle, j'etais dans une spirale repetitive qui, même si elle me permettait de dessiner en continu, me donnait une impression d'enfermement, de tourner en rond sans possibilités d'évolution.

Dès lors je me suis placé dans une logique d'interdit, à contre-courant de ce qu'on m'incitait à faire, d'expression automatique sans entrave. Je me suis interdit chaque element qui me venait spontanément, il fallait empêcher toute forme non réfléchie.

Très rapidement, mon dessin a glissé de l'illustration BD vers la représentation d'environnement massif d'inspiration brutaliste.

En supprimant tout ce qui me venait facilement, j'ai supprimé toutes les formes grotesques et vivantes qui peuplaient mes dessins pour aboutir à des paysages vides et austères que j'allais garder jusqu'à maintenant en 2021, où de nouveau j'éprouve le besoin de me bousculer.

Voilà le lien, il semble que le collectif soit devenu une association depuis.

#publication#fanzine#dessin#collectifsousvide#collectif#expressionisme#perspective#pierrebarrauddelagerie#brutalisme#encredechine#encre sur papier#encresurpapier#encrenoire#changement

1 note

·

View note

Photo

LA GUERRE INVISIBLE

LE THEATRE ET SON DOUBLE d’Antonin Artaud (1938)

Mise en scène de Gwenaell Morin

10-29 Mars à @lesamandiers

On peut être sûr que la pandémie mondiale actuelle n’aurait pas fait peur à Artaud. Prophète,il avait filé la métaphore de la contagion d’un Mal comme possible force spirituelle assez puissante pour ébranler les strates de la société; s’appuyant sur « la plus merveilleuse explosion de peste », celle de 1720 à Marseille, et son virus, pour expliciter sa théorie du théâtre. Il aurait peut-être accueilli cette terreur comme l’occasion de faire sauter l’esprit moutonneux et plat qui l’« emmerdait tout le temps » des hommes car « sous l’action du fléau, les cadres de la société se liquéfient. L’ordre tombe. Il assiste à toutes les déroutes de la morale, à toutes les débâcles de la psychologie, (…) ». Voilà la fonction du théâtre selon Antonin Artaud.

Ce sont ces effets dévastateurs dans les esprits qu’il doit produire sur le spectateur. Artaud écrit - il n’arrivera jamais vraiment à le mettre en pratique - ce que Morin nomme un « programme » à la trame poétique bouleversante avec la maladie comme métaphore, quarante ans avant Susan Sontag. Un texte unique, isolé, qui n’appartient à aucun courant, aucune avant-garde mais dont tout la monde du théâtre va un jour où l’autre se réclamer ou y faire référence. Pourquoi isolé ? D’abord sa forme, le style hyperbolique et infernal lui confère une poétique de la pulvérisation avec l’anéantissement de tout le théâtre de son époque comme objectif. Il n’est pas celui qu’on attend d’une ambition ouvertement théorique, c’est la forme de l’essai polémique qui est privilégiée. Cet exemplum de littérature apocalyptique soutient paradoxalement qu’il faut abolir le texte et la psychologie des plateaux de théâtre pour qu’il renaisse, l’homme avec. Comme tous les réformateurs du théâtre Stanislavski, Meyerhold et Brecht, c’est l’homme qui doit être changé par les moyens du théâtre. Un long poème contre le texte, contradictoire et révolutionnaire.

C’est surtout par le truchement de sa découverte du théâtre balinais lors de l’Exposition Universelle de 1937 à Paris et son voyage au Mexique que la théorie d’Artaud prend un contour prophétique et délirant.

Le deuxième grand choc que provoque ce texte, amené par ces découvertes d’arts non-occidentaux, c’est l’idée de retour à l’origine du théâtre, un ante-théâtre, c’est-à-dire son ensauvagement, un théâtre avant le théâtre où les signes remplacent les mots et les idées laissent la place aux corps. L’acteur devenant un « athlète du coeur ». Car , selon « le petit-bourgeois de Marseille » comme il l’écrit dans ses Cahiers de Rodez, la société dans laquelle nous vivons a oublié l‘aspect sacré du théâtre qui est un rite où l’on expurge tout le Mal de manière cathartique. Elle a oublié son pouvoir thaumaturge face à une société hagarde et malade.

C’est cette dimension qui intéresse Artaud qui va alors attaquer toute la littérature dramatique. Les répercussions seront intellectuellement énormes, on l’ a dit plus haut.

Que fait Gwenael Morin de ce texte par endroit indéchiffrable, hiéroglyphique ? Dans ce vaisseau de pestiféré ? Monter un texte si violemment anti-théâtral et qui n’ est pas du théâtre. Un texte fait de visions, de fulgurances oscillant entre lucidité et délire, sans nuances.

On connait l’obsession du metteur en scène pour déterrer les classiques ( Molière, Sophocle, Eschyle,..) de leur stupeur -cela, Artaud aurait aimé- et autres grands metteurs en scène ( Vitez, Fassbinder) , sa boulimie de plateau, de concret, de jeu d’acteur avec son Théâtre Permanent aux Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers. Il y a peu d’accointances entre le travail brut et artisanal à la fois de Morin et l’outrance, le refus systémique et permanent des conventions du plus célèbre patient de l’hôpital psychiatrique de Rodez. Pourtant, l’amour archéologique du théâtre de Morin devait le porter vers cet autre obsessionnel même s’il ne se réclame pas du tout de cette esthétique. Comme la plupart des gens de théâtre, la lecture de ce texte a marqué sa jeunesse. Mais c’est le Morin de la maturité qui le met en espace comme s’il fallait un temps long de gestation ou alors un retour aux origines (tiens ? ) de ce qui nous a transporté, soutenu plus jeune dans nos désirs les plus fous. C’est sans doute cette dernière hypothèse qui anime Morin pour ce spectacle. En exergue, le metteur en scène explique être tombé sur une édition trainant dans un théâtre, l’avoir feuilleté et s’être totalement retrouvé dans les idées du Théâtre et son double.

Seulement, mettre des idées sur un plateau c’est-à-dire concrétiser l’abstrait, qui plus est celles d’Artaud pour le théâtre, est à haut risque. La perdition est presque inévitable tant l’ambition est démentielle, tant le désir d’absolu de l’auteur se mêle dans son abord d’un art matériel et éphémère.

Cet absolu qui le tenaille, lui morsure tout le corps, le fait souffrir, le pousse à ce retour aux sources du théâtre. Pur dans sa théorie, impur dans ses actes, sacré et immoral, religieux et scandaleux.

Cet absolu qui veut atteindre le sacré et Morin dans sa nostalgie qui réactualise son idée du théâtre se rejoignent dans la salle des Amandiers transformée pour l’occasion en nef blanche et éphémère qui nous accueille sans sièges, vide, immense où tout est à inventer, à habiter.

D’emblée, Morin se fait bon élève et place un livre géant avec la couverture d’une vieille édition du Théâtre et son double, debout face à nous, placés de face par des ouvreurs incertains tellement l’atmosphère est performative et insaisissable. On comprend de suite la fragilité, la précarité du théâtre nu, avec seulement des corps, des mots et surtout des tripes.

Le livre-totem installé, entrée des acteurs, cercle, très beau choeur. Cercle, lien, prière, le sacré est convoqué.

Puis c’est le blasphème, les mots de malheur d’Artaud dit par l’acteur Richard Sammut, au centre du cercle , raisonnent dans la nef, tout le mal qui le ronge est exsudé. Ancré au sol, le ton est martial, La langue d’ Artaud est imprécatoire et nous regarde en face , nous dévisage, nous déshabille. Peu de déplacements, la langue qui rugit, vibre des pieds à la tête de l’acteur qui ne faiblit pas.

Le cercle éclate, quitte la scène et se mêle au public, donne la voix au public. Un spectateur lit une notice autobiographique de l’auteur qui rappelle les coups, les traumatismes reçus et alors en cours. Couteaux et séjours en hôpitaux s’entrelacent dans la construction d’une figure mythique du maudit. S’il pioche dans d’autres extraits de textes d’Artaud, c’est pour mieux se recentrer sur le personnage et aussi le mettre à distance lui et son oeuvre qui le submerge totalement. Pour ce fair , une mise en scène d’Artaud lui-même grâce à une perruque et le célèbre Pour en finir avec le jugement de Dieu , ovni radiophonique dit par Manu Laskar, retentit non sans grotesque ce qui brise l’ostentatoire imprécation de départ. On reste dans la métaphore religieuse mais au sens de relier car on est dans le public, on circule, il n’y a plus de scène, il n’y a en jamais eu en fait, il n’y a que des corps, le reste est littérature.

Et puisqu’il n’y a que des corps, il y à l’envers du sacré, du beau c’est-à-dire le scatologique, notre noire profondeur, notre âme si seule et malheureuse baignant dans une merde noire. C’est par ce prisme qu’Artaud voyait l’homme, le visible et il cherchait bien sûr comme tout prophète et martyr, l’invisible. Au nom de cela, il menait une guerre au réel, à l’homme de son temps.

Enfin, le troisième temps du spectacle est celui de la destruction caractérisée par un grand marteau que le metteur en scène impose dans l’espace de jeu. Destruction comme toute la dynamique du livre qui veut construire sur les ruines du théâtre, un art qui rend visible l’invisible et libère nos maux intérieurs par un transe de gestes .

Par Artaud, Morin retrouve le travail kinesthésique de l’acteur qui hurle, pleure, chute , cette « transe de gestes » en quête d’une présence. Et si Morin transformait ce désir de capter l’invisible par les corps d’Artaud en hommage à l’acteur de théâtre , toujours entre création et destruction, entre visible et invisible? Et si chez Morin l’acteur était la figure du sacré ?

M.Méric

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

•Alejandro Caiazza’s Brut, Neo-expressionist pieces balance the whimsical with the grotesque. Caiazza creates expressive figures in a vivid, textural style.

“The naive but sharply witty characters populating Caiazza’s images are reflected squarely in the behavior of society: ugly painted faces reflect ugly behaviors.”

• Alejandro Caiazza’s paintings often portray a humorous subject matter that rests on a dark palette and foundation, engaging the viewer in the silliness of the present with a warning of what is to come. Initially appearing whimsical and delightful with a child-like innocence, the work of Caiazza on closer inspection reveals much deeper and darker aspects of our human condition: drawing on inspiration from daily life and emotions, the uncertainty of social upheavals, and political strife.

*Based in NYC, Alejandro Caiazza’s artwork is currently exhibited at Van Der Plas Gallery (New York City) For more information call: 212.227.8983 #nycgallery

#AlejandroCaiazza #VanDerPlasGallery #newpaintings #newAmericanPaintings #theoutsiders #contemporypaintings #newyorkcity #theoutsider #primitiveART #artdealer #Artcollector #jerrysaltz #violence #grotesque #NYARTBEAT #brut #NewYorkArtBeat #outsiderart #collectors #artlowereastside #LowerEastSide #expressionism #newfigurative #ArtBrut #voyagemia #newamericanpaintings #newamericanpainters #newamericana

0 notes

Note

What makes the 14th century alliterative revival interesting to you? If I can ask?

(i’m going to do the best i can to answer this while every piece of premodern lit i own is taped up in a box somewhere. this post is also going to be very long because it’s my blog and i do what i want.)

first of all i just like alliteration in any form of poetry—i think it makes it more fun to read out loud and helps to accentuate and drive along the meter. it’s also the primary ornamental device in old english poetry—i think the ruin provides a pretty good ongoing example although the translation they’re using on wikipedia is a bit lackluster imo. the ruin is also interesting in itself for a variety of reasons but i’m personally a fan of the way the alliteration seems to ebb and flow in intensity throughout the poem as the poet moves between the city as it once was and the ruins that it is now. it’s also got a bit of internal rhyme near the start with the repetition of -orene words—gehrorene, scorene, gedrorene, forweorone, geleorene (undereotone if you squint)—that i love. this is largely beside the point. anyway it looks like this—

glædmod ond goldbeorht || gleoma gefrætwed,

wlonc ond wingal || wighyrstum scan;

seah on sinc, on sylfor, || on searogimmas,

on ead, on æht, || on eorcanstan,

on þas beorhtan burg || bradan rices. (the ruin, lines 33-37)

broadly, the rule is: four stresses per line, at least three of which alliterate (wlonc ond wingal || wighyrstum scan; or, more widely known and a bit looser, hwæt! we gar-dena || in gear-dagum...)

anyway post-conquest a lot of things change; partially because english isn’t the prestige language for a couple-three centuries afterwards so prestige poetry is in latin or norman french (or anglo-norman), partially because english itself is obviously changing through absorbing a lot of norman & otherwise-french influence, partially it is the nature of poetic form to adapt. i’ve seen some arguments that end-rhyme was introduced into french-etc. poetry through diffusion of arabic poetry out of al-andalus; i’m not qualified to comment but it sounds plausible. either way, at and after the time of conquest, french verse was generally octosyllabic, and rhyming or at least assonant—

Bels fut li vespres e li soleilz fut clers.

Les dis mulez fait Carles establer.

El’ grant vergier fait li reis tendre un tref;

Les dis messages ad fait enz hosteler;

Duze serjant les unt bien cunreez. (la chanson de roland, att. turold, c. 1040–1115, lines 157-161; assonant)

Quant des lais faire m’entremet,

ne vueil ubliër Bisclavret.

Bisclavret a nun en Bretan,

Garulf l’apelent li Norman. (bisclavret, marie de france, c. 1160–1215, lines 1-4; aabb rhyming)

alliterative verse didn’t entirely disappear, probably, but we don’t have evidence for it after the composition of layamon’s brut in 1190. the verse compositions in identifiable english that we have, like of arthour and of merlin or richard coer de lyon, tend to take after anglo-norman and french antecedents—

Merlin seyd to þe king

“Al y knowe þi glosing,

Y wot þou louest par amour

Ygerne þat swete flour.

What wiltow ȝeue me, ar tomorwe

Y schal þe lese out of þi sorwe?” (of arthour and of merlin, c. 1250–1300, lines 2477-2482)

He answeryd wiþ herte ffree,

“Þeron j moot avyse me.

Ȝe weten weel, it is no lawe,

A kynge to hange and to drawe…” (richard coer de lyon, c. 1300, lines 997-1000)

the above two are fairly representative of earlier (like, pre-chaucerian) middle english poetic literature. speaking broadly: short, metrical rhymed couplets. i should also mention, probably, that people at the time were fairly inconsistent about the scribal difference between u and v or y/i/j, that þ goes “th”, and that ȝ makes a variety of “g” or “g”-“y” cusp or “gh” or “ch” sounds and can also stand in scribally for a z or hard s.

anyway, the 14th century alliterative revival is what it sounds like: around 1350, primarily in the north and west of england, a lot of alliterative verse began to be written down. it’s…very different from the examples given above:

And þat þe myriest in his muckel þat myȝt ride;

For of bak and of brest al were his bodi sturne,

Both his wombe and his wast were worthily smale,

And alle his fetures folȝande, in forme þat he hade,

ful clene;

For wonder of his hwe men hade,

Set in his semblaunt sene;

He ferde as freke were fade,

And oueral enker-grene. (sir gawain and the green knight, “gawain poet”, c. 1370–1390, lines 142-150)

middle english alliterative verse by and large rejects end-rhyming (however, the exceptions to that rule are absolutely my favorites—more later), and brings back the four-stress line (both his wombe and his wast || were worthily smale) although in a longer and looser form than was common in old english, probably because of linguistic shifts and because of evolution of the medium. it is so fun to read out loud. sir gawain and the alliterative morte arthure are probably your most accessible examples—they’re both available in facing-page translation by simon armitage, who isn’t my favorite translator of sir gawain but does a good job of retaining the stresses. piers plowman is also representative, but reading it, to me, is a little like being trapped in the donut shop my grandpa hangs out at with a bunch of other old guys, except without donuts—it’s very old-man-yells-at-cloud. but really my interest with them is less with translation than with the way that the language sits in my mouth, and the way that i think alliterative verse sort of pulls the lines forward in a way that end-rhyme doesn’t necessarily—it feels more propulsive, more churning. it’s like a water-wheel, if that makes sense? it plays off the natural stresses of the english language in a really engaging way, and differently from iambic pentameter, which tends to get most of the spotlight when it comes to naturalistic rhythm in english poetry. and there’s a playfulness to a lot of it (especially the rhymed poems), or at least a sense of the ability to play with language, that i love and that i think a lot of people don’t really realize existed in medieval literature (or think only chaucer was capable of it.)

however! the works from the alliterative revival that combine alliteration and end-rhyme are some of my favorite poems in the english language (for a permissive definition of “english”), because they tend to develop these incredible complex, elaborate structures of rhyme and meter. so there are two poems in this category that i’m going to talk about, and i can go for…a long time on the second one. i’m not really going to bring up sir gawain on its own much more because, no room, but it’s really one of my favorite arthurian works, in part because of the alliterative verse, in part because i just love the figure of the green knight and the awful castle hautdesert threesome setup; it’s also one of the more accessible examples of the core of the genre (at least to me—i bounced really hard off of malory, the mabinogion is fun but deeply weird in a way that might put off beginners, and i think chrétien de troyes really depends on how you’re introduced—english translations of french arthuriana tend to be prose translations, which is a whole different post but suffice it to say i don’t think they work.)

first is the three dead kings, which is an expansion on the “as you are so i once was / as i am so shall you be” type of memento mori motif that was pretty common at the time; three kings on a boar hunt run into three corpses who identify themselves as their ancestors and tell them to stop fucking around and take death seriously. so, thematically—i think memento mori art and literature is a lot of fun, in general; the combination of the focus on life’s transience with macabre and often enthusiastically ghoulish imagery—

Lo, here the wormus in my wome — thai wallon and wyndon!

Lo, here the wrase of the wede || that I was in wondon! (the three dead kings, att. john audelay, c. 1426, lines 98–99)

—and the vision of life still continuing after death and among the dead, not necessarily solely in the sense of the resurrection but in a community of the dead on earth who speak to and concern themselves with the living, it’s just very fun. (afterlives by nancy mandeville caciola is an absolute blast on that front, by the way.) the three dead kings is also structurally complex in a really enjoyable way: it’s not bob-and-wheel (which you see very famously in sir gawain, the little two-word bob and four-line abab wheel at the end of each verse), but the five-line cdccd bit that i’d call a sort of wheel; and then the main body of each stanza has this very fun abababab scheme where the a- and b-words still half-rhyme with each other. from the stanza i quoted above, you get “fynden — fondon — lynden — Londen — byndon — bondon — wyndon — wondon”. i think it plays very well with the meter.

aside from that, i love the imagery of it; it ranges from, like i said, almost comically grotesque—the dead king whose legs are like leeks wrapped in linen, the worms wallowing and winding in the womb (interesting word choice, also)—to this very sere, wintry atmosphere; the last stanza has a half-line about the “red rowys of the day,” the red daylight, that i just love. and i’m a big fan of the way that, kind of like sir gawain in miniature, the three dead kings opens with this celebration of chivalric performance that’s suddenly pulled askew by the intrusion of supernatural—or, like, really, the most natural; what’s more normal than death, or than cyclical renewal?—forces.

the second poem is pearl. (the linked translation is not my favorite; simon armitage has a facing-page one that’s pretty good, but my favorite overall is marie borroff’s (rip), who also did my favorite sir gawain.) i’m going to do my best not to just go on and on about pearl for ages, because this post is already very long, but it’s also, i think, one of my favorite poems, period. its structure is very hard to talk about briefly, because the way that it’s built is integral to its subject. in brief: 101 stanzas, each of 12 lines in abababab-bcbc rhyme, divided into 20 cantos (the 14th canto has 6 stanzas, the rest 5), for a total of 1212 lines. within each canto, the first and last line of each stanza repeat these linking words and phrases (except the first line of each canto, which does so to the final line of the canto preceding, and the final line of the poem, which paraphrases the opening line.) this is all because pearl is in part about heavenly geometry, the square/cube of the heavenly city (12 furlongs on a side, filled with 144,000 maidens) and the circle/sphere of the pearl, and the way that those two shapes are interposed on each other—there’s a lot of structural/behind-the-scenes numerology and geometry to talk about, but like…i won’t right now. it’s also, in the poem itself, something that can’t fully be talked about—

An-under mone so great merwayle

No fleschly hert ne myȝt endeure,

As quen I blusched upon þat bayle,

So ferly þerof watȝ þe fasure.

I stod as stylle as dased quayle

For ferly of þat frelich fygure,

Þat felde I nawþer reste ne trauayle,

So watȝ I rauyste wyth glymme pure.

For I dar say wyth conciens sure,

Hade bodyly burne abiden þat bone,

Þaȝ alle clerkeȝ hym hade in cure,

His lyf were loste an-under mone. (pearl, “gawain poet,” c. 1370–1390, lines 1081–1092)

briefly—the narrator sees the heavenly city and nearly dies on the spot, only protected by the fact that this is all taking place in a dream-vision. borroff translates a bit of that as:

As a quail that couches, dumb and dazed,

I stared on that great symmetry

Nor rest nor travail my soul could taste,

Pure radiance so had ravished me.

like…i love that. so much of pearl is about mortal and divine perception, about the unknowability of death and the depth of grief and the final breakdown of the consolatio as a literary-philosophical genre, and about the way that the dead who have transcended death and come out the other side are residing because of that transcendence in a fundamentally alien sphere of cognition, marked out by the impossible-to-withstand radiance of the heavenly city.

but what pearl is about-about, it’s generally agreed, is the death of the narrator’s young daughter. she is the pearl who he lost; grieving her, he falls asleep in a garden and has a dream. in this dream, he wakes up in a fantastical garden or forest, divided by a river, and on the other side of that river is a beautiful young woman who identifies herself, and who the narrator identifies, as the “pearl”. the rest of the poem is a back-and-forth between the narrator and the pearl-maiden, which is largely him asking questions and her explaining biblical parables to him. but describing the conversation as that really does it an incalculable disservice, because what it is is, on the one hand, a grieving parent asking these very human, tender questions of his lost child—are you really her? why did you have to go? where are you? are you happy where you are?—while the child offers only these very stern, cold rebukes—þou most abyde þat He schal deme—and abstruse explanations of the parable of the vineyard; and on the other hand, someone who has been made greedy and grasping and willfully uncomprehending in his grief, refusing to understand that the child he lost is happier where she is now, and that she can be happier there, and that he cannot join her before his decreed time. and he’s not at fault for being that way, but he’s thinking in ways that are fundamentally limited by the mortal realm that he can’t yet exit and she’s thinking in ways that are incomprehensible to people who haven’t also undergone the same apocalyptic, in the word’s sense of “unveiling” (but also, i mean, she’s in the heavenly city), reorientation of thought and being. it’s a very tender poem that i think also manages to prefigure some of the staples of eldritch horror.

and i love how the structure plays into that; the alliteration is looser than the three dead kings—there’s basically no caesura (the || that shows up sometimes in three dead kings and is more or less mandatory in old english verse), and sometimes there’s only 2 alliterations to a line, because the lines are shorter, or none at all—but it’s still got these wonderful repetitions of sound across the stanzas, tied into the repetition of the key words at the beginning and end. the whole thing builds up and up and then collapses back onto the beginning, as the narrator gradually believes he’s understanding more and more and then, in his attempt to ford the river before his time, is thrown back into the mortal world; the poem’s like an impossible staircase. it’s this massive crystalline structure enclosing a deeply human core. there is, to my knowledge, nothing else like it. it—and the other works, including sir gawain, attributed to the “gawain poet” on the basis of stylistic similarities—survives in a single manuscript, cotton nero a.x, which fortunately survived the ashburnham house fire in 1731.

to close off on the alliterative revival at large, it fell out of fashion over the 1400s; in england, the chaucerian tradition—end-rhymed iambic pentameter—dominated, and while alliterative-meter poetry still had some currency in the scottish court that ended with james vi/i stuart’s ascent to the english throne and transfer of his court to london. in modern usage, alliteration as its own technique does crop up in poetry—and i’m always happy to see it—but alliterative meter (as in, four-stress lines, or even the looser form of sir gawain or the three dead kings) is much less common and most people encounter it either through translations of beowulf or through some of the poetry in the lord of the rings (from dark dunharrow || in the dim of morning…)

1 note

·

View note

Text

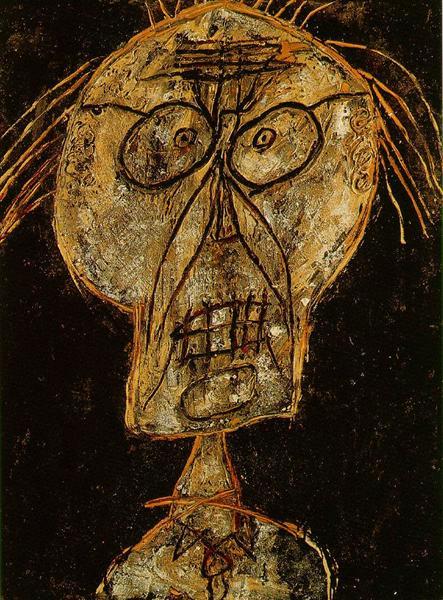

Jean DuBuffet

Jean Dubuffet was a French Painter and Sculptor Dubuffet was the founder of an entire art movement, ‘Art Brut’ (Outsider Art or Raw Art) Dubuffet tore down the boundaries of the established art world and opened art up to self-taught outsider artists. His adoption of the term Art Brut or raw art, referred to the art of children, prisoners, and the mentally ill.

Frustrated by intellectual approaches to art, Dubuffet continued to take interest in the artwork of outsiders. In attempting to recreate what he saw as their uncontrolled style, he chose to paint in seclusion where he could experiment with new methods and concepts. Dubuffet never took inspiration from pop culture at the time of him working. Heavily influenced by the paintings of Jean Fautrier, Dubuffet began to take a similar approach to the texture of his paint, combining sand, gravel, tar, and straw to his paintings to create a thick emulsion. As Dubuffet became increasingly obsessed with texture, he began to drastically limit his palette, focusing on dark, monochromatic surfaces and figures.

The content featured in his work included the countryside, including childlike depictions of cows and milkmaids. Although he created many portraits based on urban individuals exaggerating features and proportions to create grotesque caricatures and challenging cultural standards of beauty.

Dubuffet did not believe in the separation of the beautiful and the ugly and believed that ugliness did not exist. He expressed this in many of his paintings such as the painting ‘The Monseiur Plume’ 1947.

His work has inspired my own work greatly because his work because often in a lot of my own work I do not want to discuss theory or philosophy I just want to think more about fantasy and experiment. In addition to this, Dubuffet inspired me to explore documenting / diary writing in my own work which inspires my paintings.

Grand Monseiur of The Outsider

Oil and Emulsion on Canvas

1947

Site with Four Characters, 1981

Times and Places, 1979

0 notes

Text

Detail from a work in progress.

www.carpmatthew.com

#art#hell#love#carpmatthew#artists on tumblr#artist#london#gallery#contemporary art#art brut#art scene#politics#faith#mortality#horror#farce#outsider art#low brow art#emerging artist#grotesque#mouth

14 notes

·

View notes