#Cafe press exploits artists

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

CAFE PRESS WILL USE YOU FOR AI

The highlighted portion of Terms & Conditions reads in its entirety:

"By submitting Your Content to us, you grant us a nonexclusive, worldwide, royalty free, fully paid-up, transferable, sublicensable, perpetual, irrevocable license to reproduce, distribute copies of, prepare derivative works based upon, publicly perform, publicly display, train artificial intelligence on, and otherwise use and exploit Your Content for the purpose of providing the Services and promoting to you other services we believe will be of interest to you."

Oh, but by golly, you'd better be in full legal control of your materials, or that's a violation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

watching your devil side

one.

///

The sun blazed through the large airport windows and the soft, hazy morning mist descended upon Naples. You hadn’t been in the since your last photo shoot for some jewellery line two years ago but you heard news about an old friend while preparing a home base for your art exploits in Europe.

The little kid you once saved from a beating after a pick-pocketing incident in Naples when he was ten and still had black hair was now the Don of the Passione and blond if your sources were right. You had meant to visit him two years ago but he was a hard kid to track down and meet within a time span of three days. However, now, you had all the time in the world with your current job as an artist and you were going to buy him an espresso like you promised all those years ago.

You tapped the screen of your phone and hummed.

I didn’t know you turned blond, you sent a text message and signed it with your typical Devil Yin attached to let him know it was you.

Your luggage trembled as you traversed through the bustling airport, looking for a sign with your name on it. The private driver you hired had given you explicit instructions.

A tall man with silvery hair and in his fifties stood among the small crowds waiting for other passengers but held a small sign with your name written boldly in black. You shot him a friendly smile and waved. He bowed his head and tucked away the sign, gesturing for you to follow him.

“Hello, sir. You weren’t waiting long, were you?”

“Not at all, young miss,” he answered as he led you to a black car, “please, hand me your luggage. I trust your flight went well?”

“As well as any fourteen hour flight can go,” you replied wryly.

He opened the door for you and you slipped into the backseat, crossing your legs. The silky fabric of your pants pressed into your skin and you itched to get out of them to let your body breath after the stale plane air.

“Still the villa in Napoli, miss?”

“Yes, take your time. I still need to decompress from the trip and car rides are perfect for that.”

Your phone buzzed in your pocket and you pulled it out.

How did you know that?

You smiled and typed out quickly. I just do. Remember that espresso I promised you six years ago? You’re old enough to drink one now, don’t you think?

I accept your offer. Where are you staying? I’ll send a car over.

You texted him the address to your villa and told him to meet you at lunch. That would give you enough time to decompress, get ready, and unpack half of your things. You were staying in Italy for a while, after all.

///

A black sedan with a polite but distant driver picked you up thirty minutes before noon and deposited you in front of a little cafe tucked in between a bakery and a bookstore. You walked in, the sharp but comforting scent of espresso wafted and curled around you.

A blond head of dramatic curls peeked out from a booth along with a shock of black-blue hair.

“I, Giorno Giovanna, will be a Gangstar!” The kid proclaimed.

That looked enough like a dramatic Gangstar to you.

“Giorno Giovanna?” you asked.

The boy turned around and sharp turquoise eyes landed on you. “It’s really you, Yin.”

“The one and only.” Your gaze slid to the man sitting beside him and you blinked. “Bruno Buccellati?”

“Devil Yin,” he greeted, a welcoming smile on his face. “It’s been a while.”

“...well, it seems like I’m caught as a disadvantage,” you said, “may I sit?”

“Yes, of course.” Giorno waved his hand. “Actually, you decided to visit at a good time.”

You sat down across from them and scrutinised the two. They were well put together with expensive suits, styled hair, and gleaming jewellery. “I’ve heard. Don of the Passione at sixteen is quite a feat. You really did become a Gangstar. Congratulations.”

Giorno smiled. “Thank you, but that’s not why your visit is...fortunate.”

“I assume the reason is why you’re here as well, signore Buccellati,” you said, guarded.

Buccellati smiled. “Perhaps Bruno would be best, signorina Yin.”

That wasn’t actually your name but you didn’t comment further, scanning the cafe. A red-patterned hat caught your eye, peeking out from another booth, and another booth with a familiar looking man with long silver hair caught your eye.

The presence of the Capo of Squadra Guardie del corpo along with his team was either a very good thing or a very bad thing and you sure hoped it was the former. You did not want to get shot at when you were trying to buy an espresso for a brat you met six years ago. You didn’t even know if this was a good idea considering the pendulum could swing any way and you wouldn’t know it.

“Hello!” A waitress swanned in, smiling prettily. “Is there anything I can get for you today?”

“A caffè lungo,” you said, staring at the two men across from you.

Giorno smiled charmingly at the waitress. “The same as her.”

“A caffè macchiato,” Bruno said.

You narrowed your eyes at them when the waitress disappeared with your orders.

“Now, why is Leone Abbacchio, signore Buccellati’s right hand man, and some strange teenager with a stand also in this cafe?” You leaned back. “I guess this isn’t the casual meeting I proposed?”

Giorno and Bruno exchanged glances and a smile cracked the blond’s facade.

“Still as perceptive as ever,” he said.

“And that’s not an answer.”

Bruno leaned forward, hands brace on the table. “We have a proposal for you, signorina Yin.”

“Listen, I’m just here to buy Giorno the espresso I promised he could have when he turned sixteen the last time we met. Not for any business with the Passione.”

He smiled, amused and infinitely a softer charm compared to the teenager beside him.

“Come work for me in the Passione as an assassin,” Giorno said lowly. Calm, steady, and self-assured, and the turquoise eyes intense as he stared at you.

You looked at the waitress reappearing with your drinks, waiting for her to set them down and leave their presence once more. She probably knew they were the mafia with how quickly she scurried away.

“No,” you said and pushed Giorno’s drink at him while sliding the macchiato towards Bruno. The man accepted it graciously but your gaze didn’t leave Giorno’s unchanging expression.

“No?” he asked calmly.

“I quit the business, Giorno.” You shook your head and slid your phone across the table towards him with one of your galleries from Seattle, Washington. “I’m a painter and model now with a lot of money in stocks. I can’t go around assassinating people without drawing attention to myself. I put that life behind me for a reason.”

"We need someone of your calibre especially after the power change," he insisted. "Our assassination team lost two members before the change in power. They need a new but experienced hand and with your skills, their repertoire would expand. The amount of missions would increase for them."

You tilted your head. “...I’ll give you twenty minutes to give me the full story and another five to convince me.”

He smirked.

///

You cradled your empty cup, staring into the ceramic.

“That’s a ride,” you finally said. “A very, very long ride with too many lane changes and things going downhill but I don’t see what this has to do with you wanting me to become an assassin.”

“La Squadra Esecuzoni were being underutilised by Diavolo and we don’t want them to feel the same as they had beneath him,” Bruno explained.

“You’re afraid they’ll rebel.” You set down the cup. “And that’s not something you can afford right now. Aren’t they satisfied with the territory you’ve given them?”

“No,” Giorno said, leaning forward on folded hands. “They want more after helping us overthrow Diavolo.”

“I won’t become an assassin again,” you said.

Giorno’s expression furrowed and Bruno’s shoulders tensed, ever so slightly, but they wouldn’t force you to bend to their will. They were too nice for that.

“But... I think there’s a way I can help you.”

“Without becoming an assassin?” Bruno asked.

"I have a job in mind for them. How do they feel about being bodyguards?" You set your hands on the table between you. “I might need some while I’m here.”

“Bodyguards?” Giorno blinked.

“Did you know I was held hostage a few months ago by some pirates in the Indian Ocean? None of my friends answered my texts for two weeks. It really hurt my feelings.”

The two men in front of you exchanged looks.

///

It was rare for Risotto to call a team meeting nowadays. The last time had been hunting down Diavolo with Buccellati's squad but he was dead and Giorno hadn’t done anything yet.

Risotto sat at the head of their conference table in their new headquarters.

"The Boss has a new mission for us,” he announced. Red eyes surveyed their reactions. “As bodyguards to an important client.”

"What the fuck?" Ghiaccio said. "We're fucking assassins and he's sending us as bodyguards? Who the fuck does he think he is? Is he downgrading us?"

“Buccellati’s squad can’t handle it?” Prosciutto raised an eyebrow.

"We have no choice but to accept." Risotto slid a document into the centre of the table. “It’s a long term contract. Two of us at all times. Cash salary.”

“Di molto,” Melone breathed, eyes wide. “That’s a lot of money.”

“Holy shit.” Formaggio leaned forward to look closer at the papers. “Who the fuck are we protecting? A princess?”

“Is that a clause for vacation pay?” Illuso asked, incredulous. “They’re offering hitmen vacation pay?”

Prosciutto ran his fingers over the numbers, brows furrowed. “How did Giovanna secure something like this?”

Pesci’s eyes flickered between the other members then his black eyes landing on his mentor and asked nervously, “This is good... right, bro?”

Prosciutto didn’t answer, deep in thought as he leafed through the papers.

“Why the fuck is he giving us this mission instead of Buccellati’s squad? They’re meant for guarding. What’s Giovanna planning?” Ghiaccio scowled, arms crossed. “He would not give us something like this without leverage.”

“Giovanna said the client specifically requested us.” Risotto’s deep voice interrupted him before he could fall into a rant.

Ghiaccio adjusted his red glasses and smoothed his blue curls.

“Giorno said the client wants us to meet them at Passione headquarters.” Risotto folded his hands over the table, the black sclera of his eyes emphasised the red of his gaze. The resolve in his eyes silencing the rest of the members’ protests. “I will take Prosciutto and Illuso with me.”

“This is a hard offer to turn down,” Melone said.

“Do you have to say something we already know?” Illuso sighed.

///

Summary: La Squadra Esecuzioni ends up helping Bruno’s squad defeat Diavolo and everyone lives but the journey hasn’t even begun. Giorno becomes Don of the Passione and revolutionises the mafia but La Squadra finds themselves underutilized despite the new territory they've been given. At least, until you, an old friend of Giorno’s, takes a trip back to Naples. What they never expect is that you're a whirlwind in disguise and they can't help but get caught in your restless winds.

This entire storyline takes place in the year 2020 and everyone is alive. I can’t write a story without modern day technology or memes. Yes, this is a shitty first chapter. It might get better from here on out but we’re trying to establish a snappy first base for the zero attention span squad (me, that squad is me.)

(ao3 link)

#watching your devil side#jjba#risotto nero x reader#prosciutto x reader#la squadra esecuzioni#la squadra#melone x reader#ghiaccio x reader#pesci x reader#illuso x reader#formaggio x reader#vento aureo

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three Sides to the Story

Fandom: Miraculous Ladybug Pairings: Adrien/Marinette Summary: It's been almost three years since Adrien Agreste walked out of Marinette's life. An accidental meeting at a party starts a course of events that will either drive them together or further apart. Meanwhile, Plagg and Tikki have had enough of their holders' indecision and obliviousness.

Read it on A03

Chapter 1: 10th March

It was opening night of the latest production at Opera de Paris and Adrien, at 21 years old, was deemed ready to attend in his father’s stead. Adrien would watch La Boheme from Gabriel Fashion’s box, then rub shoulders with the city’s elite at an extravagant after-party at Le Grand Paris Hotel.

Gabriel Agreste was becoming increasingly reclusive, and aside from business meetings he barely left the mansion at all these days, so Adrien was expected to do more. Juggling his International Business degree with family responsibilities and modelling (as well as saving Paris from regular akuma attacks) was wearing him down. He’d have to get used to it because in less than eight months, he’d be starting work full time at Gabriel Fashions and he’d be under his father’s scrutiny more than ever before.

“Adrien, I need to you model competition entries for the graduate designers internship so please try not to gain any more muscle in the next week.” Gabriel Agreste raised an eyebrow at his son as the seamstress let his tuxedo jacket out again.

“Yes, father.” Adrien dutifully replied.

“I mean it. Your measurements have already been sent out and the finished pieces must fit you for the fashion shoot.” Gabriel reiterated.

Adrien didn’t answer. He hung his head in a display of acquiescence. Tell Hawkmoth to stop with the akuma attacks and I’ll stop gaining muscle. He thought, bitterly.

“I expect you to be available for individual shoots with each of the students, Adrien, so don’t make plans for the next few weeks.” Gabriel added.

“Yes, father.”

He often yearned for the comparably carefree days of collège and lycée. At least he had his friends around him then. He still saw Nino for lunch a few times a week (often accompanied by Alya), and he was always invited his to games night with the boys from their class, even though he and Max humiliated the rest of them at every game. At least, now that Fashion Week was finished, he’d be able to spend more time with them. He missed their daily companionship, though. And, it pained him to admit, he missed Marinette.

They weren’t friends anymore. He knew he deserved it, deserved her anger, but nearly three years without her in his life was too long. He was studying at Université Paris-Sorbonne (only acceptable to his father because it was located close to the mansion and on the understanding that he would continue to model Gabriel fashions until graduation), while she was at ESMOD towards the north of the city. Even if their paths were likely to cross, he doubted she’d want to speak to him any more. He didn’t mean to hurt her and it was unlikely he’d ever get the chance to apologise.

“Your date is here.”

Nathalie stood in the doorway of his room. He wasn’t sure how long he’d been lost in his thoughts, but at least he’d managed to get dressed in spite of his reverie. His bowtie was crooked so Nathalie straightened it for him. She brushed a speck of fluff from his shoulder and regarded him with scrutiny. Satisfied, the ghost of a smile crossed her lips.

“Very handsome.” She said, almost proudly.

★・・・・・★・・・・★・・・・・★

10th August - 2½ years ago

“You look very handsome, Adrien dear.” Sabine Cheng wore the sweetest smile as she regarded him.

It was enough to calm his nerves and reassure him that the straight legged black wool trousers and dark grey shirt with raw-edged seams were the right choice. Jeans were his uniform and he felt safe in them, but his father insisted he choose an outfit from Gabriel’s newest pret-a-porter collection.

“And just where are you taking our little girl tonight?” Tom asked.

Every time Adrien arrived, Tom tried to do the protective dad thing, but his stern tone was always betrayed by the twinkle in his kind eyes. The warm hug as he greeted the teenager was a giveaway, too. Both of Marinette’s parents were amazing; protective without being overbearing, but permissive. They trusted their daughter, and they seemed to trust Adrien too.

“We’re going to grab some food then we’re going to a jazz club in the Latin Quarter. Adrien told them.

“If the reports are correct, Andre and his ice cream cart are on Pont du Sully tonight, if you two wanted to stretch your legs after dinner,” Tom said as one eyebrow arched so high it almost disappeared into his hairline. It earned him a “Chérie, s'il te plait, don’t put pressure on them.” from Sabine.

Adrien was about to respond but, just then, Marinette came down the stairs in and he forgot how to speak.

She was wearing a black Bardot-style top tucked into a pencil skirt that stopped just below her knees. Bare legs lead to black peep toe shoes with a kitten heel. Her hair was twisted into a messy bun at the nape of her neck, emphasising her bare shoulders. She wore minimal makeup, just mascara and a sheer red lipstick, allowing her natural beauty to shine through.

“Wow” Adrien breathed. “You… er. Amazing. You look amazing.

”Demurely, she nodded to acknowledge his compliment.“You look very handsome.” She said, raising up on her tiptoes to place a soft kiss on his lips. “So, where are you taking me tonight?”

“There’s a bistro near Boulevard St. Michel I like. What do you think?” He said.

“Le Quartier Latin?” She grinned. “Vive la vie bohème.”

★・・・・・★・・・・★・・・・・★

Mireille Caquet stood in the hallway dressed in a champagne-coloured strapless brocade gown with a full pleated skirt. It was from Gabriel’s latest couture collection. Adrien’s waistcoat was made from the same fabric.

“You look nice.” He said, carefully kissing her cheeks, making sure to avoid transferring any of her expertly applied makeup onto himself.

“Likewise, Mr Agreste,” Mireille responded. “Shall we?”

La bise. That was the extent of his love life these days.

His father would select young rising stars who reflected the brand’s values to accompany Adrien to public events. They would wear Gabriel’s designs, be photographed on the arm of Paris’s most eligible bachelor and in return, they would gush to the red carpet press about how wonderful Adrien is and, ‘oh, this? It’s a Gabriel, of course’. It was mutually assured exposure.

Mireille was a popular up and coming TV personality; perfect for Gabriel’s brand. Adrien liked her and they had become good friends over the course of these ‘PR dates’. He knew she was dating Theo Barbot, the artist, so nothing would ever happen between them and he was fine with that. There was no obligation.

The performance was exquisite. La Boheme was one of his favourite operas and Adrien lost himself in the story. He laughed as Schaunard recounted his exploits with the parrot, cheered internally for Musetta and Marcelo and felt his stomach knot as the embroiderer’s illness and Rodolfo’s sacrifice became apparent. The final curtain fell and his eyes shone with tears as he stood to applaud the cast.

The house lights illuminated and Mireille slipped her arm through his as the auditorium emptied. They were ready for the real performance now - the after-party with Paris socialites and celebrities.

An hour later, Adrien was standing one of the smaller ballrooms of Le Grand Paris, a glass of Champagne in one hand. He was bored. He’d spoken to most of the notable people, introduced Mireille to a few TV execs, shmoozed an industry bigwig or two. He’d done his duty.

Mireille appeared once more at his side, reading his expression.

“I know of another after-party that’s more our speed.” She said, smiling.

»»————-————-««

The venue was a late night cafe near the Square du Temple. (They were not far, he realised, from his classmate Alix’s house, it was the venue of many legendary parties in his school days.) It was dimly lit and noisily busy inside. Mireille held his hand and pushed them through the crowds to the private room at the back of the cafe. It was less crowded in here, but no less rowdy. Mireille spotted Theo and left Adrien alone to greet her lover.

Adrien loosened his bowtie and unfastened the top two buttons of his shirt. He looked around the room and smiled. Opera singers, stagehands and musicians mingled freely. He relished every opportunity to be around Paris’s artistic community. He knew his father used to move in similar social circles (that was how he’d met Adrien’s mother) but these days he was all business. Growing up around photographers, hair stylists and makeup artists, Adrien was most at ease amongst creative types.

“Vive la vie bohème,” he said, to nobody in particular.

That was when he saw her.

She was standing by the bar with a glass of red wine in her hand. Her attention was on a flamboyantly dressed woman who was speaking passionately about something, if her over the top gesticulations were any indication. Her blue-black hair hung in loose curls down her back and bluebell eyes peeked through almost-too-long bangs. She wore sheer red lipstick, lending sophistication to her youthful complexion. Next to her, with one hand around her waist, stood a man. His blonde hair was styled high on his head and thick black eyeliner gave him an androgynous look.

A familiar strawberry blonde mop of hair appeared in his peripheral vision. Nathaniel was often at these parties and he and Adrien always took some time to catch up. They were never that close at school, Nath was too shy to make many friends, but art school had brought him out of his shell.

“She’s still the most beautiful girl in the room, huh?” Nathaniel said, following Adrien’s gaze.

“She is.” Adrien sighed, momentarily forgetting himself. “Ahem, I mean��� oh, hell. You know the struggle, right?”

Nathaniel patted him on the shoulder in solidarity. “I sure do, man.”

They smiled wistfully at each other, averting their eyes to look once more at Marinette.

“You’ve got to let it go, Adrien. She’s moved on. You should too.” Nathaniel said. “We all have That One in our pasts. She’s always going to be the one that got away.”

#ml fic#ml fanfic#adrienette#marinette x adrien#adrien has angst#miraculous ladybug#my fiction#my writing#a03 fic#Three Sides to a Story

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If New York’s Madison Avenue is popularly regarded as the symbolic headquarters of the American advertising industry, then Times Square would surely be the showroom. Positioned at the very heart of the nation’s commercial capital, Times Square has long been a prized platform for the latest and greatest in spectacular outdoor advertising. As early as the 1910s, the area was renowned as what O.J. Gude, the pioneer of illuminated display, called a “phantasmagoria of lights and electric signs” (Taylor, 236) –– and, a hundred years later, Times Square still attracts crowds from around the world who flock to experience its distinctive blend of kinetic urban energy and promotional razzamatazz.

The vital blocks of Times Square between 44th and 46th streets have been an especially desirable focus for advertisers in their ongoing efforts to capture consumer attention with shock-and-awe ballyhoo. Over the decades these two blocks have been home to such promotional wonders as a gigantic neon sign with truck-sized bubble-blowing goldfish, an illuminated box of tissues woven out 25,000 light bulbs, towering bottles of soft drink four storeys tall, a Marilyn Monroe colossus, and, a 120-foot (36.6m) long waterfall flanked by a mammoth pair of neoclassical statues (Levi and Heller, iv; Shepherd, B5).

In 1956, the Arkraft Strauss Sign Corporation, New York City’s preeminent sign designer and manufacturer, consolidated a range of formerly separate advertising spaces above the western side of the block between 45th and 46th streets to create what was proudly proclaimed as “the biggest billboard in the world” (Starr and Hayman, 194). Dubbed ‘the Astor-Victoria billboard’ because it sat atop two movie theatres thus named, the huge advertising hoarding ran the full length of the city block along Broadway and wrapped partially around the sides down W.45th and 46th streets. It rose to a towering height of 60-feet (18.3m) and had an overall surface area of 15,000 square feet (1394m2), or a third of an acre (“New Super-Billboard,” 3).

The gargantuan billboard’s first ‘tenant’ was a hugely controversial advertising poster for Baby Doll, Warner Bros’ steamy 1956 film based on a Tennessee Williams’s one-act drama (Berger, 23). Designed for maximum visual impact, the poster for Baby Doll featured a towering image of the film’s young female star, Caroll Baker, sprawled across the horizontal length of the city-block hoarding –– “almost as big as the Statue of Liberty,” trumpeted the film’s pressbook (Palmer and Bray, 130). Semi-clad in a revealingly loose nightshirt, Baker was depicted lying in an over-sized cot sucking her thumb, gazing out from the billboard with sultry allure. In convincing the studio to finance this unprecedented promotional endeavour, the film’s producer-director, Elia Kazan argued the billboard would make Baby Doll “the talk not only of Broadway, but of the show world, of cafe society, of the literati, of the lowbrows, and of everybody else” (Palmer and Bray, 130). And he was right. The Baby Doll colossus of Times Square was an instant cause célèbre: suburban visitors gawped with wide-eyed disbelief, conservatives were scandalised, and the Catholic Archbishop of New York fulminated from the pulpit of St Patrick’s (Haberski, 61ff). Newspapers across the country carried stories––and pictures–– of the scandalous billboard, ensuring practically everybody in America knew of the film. It was a PR masterstroke that paid off handsomely.

The spectacular success of the Baby Doll campaign instantly marked the Astor-Victoria billboard as the premiere New York venue for blockbuster movie promotions. Over the ensuing two decades, the billboard would host a cavalcade of big screen luminaries including James Bond, The Vikings, Dracula, Krakatoa, Doctor Dolittle, and, even, The Bible. It was also used to promote the odd Broadway spectacular. Not surprisingly, rental of the site was at a premium with average leasing costs in the 1960s of over $30,000 per month (“Advertising”, 27). Because of the expense, the billboard typically saw rapid turnover. Most displays would feature for two or three months at most, before being painted over to make room for the next promotional colossus.

In mid-1968, the billboard hosted one of its most lengthy––and iconic––campaigns when Twentieth Century-Fox took out an extraordinary six month lease to advertise their big new Julie Andrews musical, Star! Like all of the advertising displays featured on the Astor-Victoria site, the Star! display had to be hand-painted because the billboard dimensions were simply too big for preprinted posters. Working from a studio-produced plan, the crew of 12 artists, sign hangers and outdoor painters spent over 1500 man-hours and 100 gallons of paint to produce the finished product. Work on the billboard started in mid-May and was finally completed in early-June (Messick).

The Star! billboard was a prominent feature of the mid-Manhattan landscape right through the celebrated ‘summer of ‘68’ till after the film’s New York premiere on October 22, before finally being painted over in late-December. Because the Star! billboard was in situ for so long, especially through the peak summer season, it pops up frequently in photographs, postcards, tourist snaps, newsreel footage and even the occasional oil painting. Indeed, at times it seems as if more people possibly took pictures of the Star! billboard in Times Square than saw the actual movie when it come out in October!

After Star!’s departure at the end of 1968, the iconic Astor-Victoria billboard suffered a slow but steady decline. In 1972, the Astor movie theatre closed its doors, lying fallow for many years, while the Victoria rebranded as a porn venue (Morrison, 158). As the 70s wore on, the billboard was still used for the occasional Hollywood blockbuster, but it was increasingly reduced to advertising B-grade exploitation pics and flash-in-the-pan rock groups. In 1982, the whole site and, with it, the billboard fell victim to the wreckers’ ball as part of the city’s master plan for the gentrification –– some might say the “Disneyfication” –– of Times Square (Shepherd, B1).

In a neat historical coincidence, the former Astor-Victoria site was eventually redeveloped as the Marriott Marquis, a hulking 50-storey hotel with a huge basement theatre that opened in 1985. The Marquis was the very theatre where Julie Andrews made her long-anticipated return to Broadway in 1995 in the musical stage version of Victor/Victoria (1995-97). It was a move that effectively saw Julie’s name back up in lights in more-or-less the exact spot where the Star! billboard had towered in 1968.

But there’s a further historical twist! In late-2014, the Broadway facade of the Marriott Marquis was redeveloped to accommodate a massive state-of-the-art LED advertising screen that was breathlessly claimed to be –– you guessed it –– “the world’s biggest billboard”. So half a century later, the western side of Times Square is once again home to a giant billboard the size of a football field.

Now, we can’t help but wonder if these historical synergies aren’t possibly trying to tell us something…like, oh I dunno, that this new state-of-the-art advertising screen in Times Square should host a special homage to mark the 50th Golden Anniversary of Star! Just imagine a digital recreation of the 1968 Star! billboard shimmering in 24 million-LED-pixel high definition glory across the night skies of midtown Manhattan! Anyone feel like starting a GoFundMe campaign? :-)

Sources:

“Advertising News.” The Film Daily. 6 February 1964: 27.

Berger, Meyer. “A Red-Blond Beauty with 75-Foot Legs? Why, it’s Baby Doll of Times Square.” The New York Times. 22 October 1956: 23.

Haberski, Raymond. Freedom to Offend: How New York Remade Movie Culture. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2007.

Lehnartz, Klaus. New York in the Sixties. London: Dover Books, 1978.

Messick, Kit. Artkraft Strauss Records, 1927-2004. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. 2011.

Morrison, Andrew Craig. Theaters. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.

“New Super-Billboard for Times Square.” Advertising Age. Vol. 27, no. 42. 15 October 1956: 3.

Palmer, R. Barton and Bray, William Robert. Hollywood’s Tennessee: The Williams Films and Postwar America. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009.

Shepherd, Richard F. “Times Square: Trying to Keep the Panache.” The New York Times. 5 February 1987: B1-B5.

Starr, Tama and Hayman, Edward. Signs and Wonders: The Spectacular Marketing of America. New York: Currency, 1998.

Taylor, William R. ed. Inventing Times Square: Commerce and Culture at the Crossroads of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

Levi, Vicki Gold and Heller, Steven. Times Square Style: Graphics from the Great White Way. New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

© 2018, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved

#julie andrews#star!#fiftieth anniversary#star!50#times square#new york#1968#billboard#advertising#hollywood#musicals#film poster#manhattan#broadway#marriott marquis#theatres

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(NOTE: If you want an accurate idea of the real-life spy that Oscar Isaac will be portraying in his next film, “Operation Finale,” read this. What a story! 😱)

***

For a long time, when I was growing up in the building I still live in on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, I knew one neighbor only as Peter. Tall, bronzed and muscled, Peter lived on the 13th floor. If I was riding the elevator alone with him, he always said, “Hello, how’s your mother?” in an Israeli accent after (sometimes) removing a cigarette from his mouth. When I’d see him talking with my 4-foot-10-inch mother in the lobby, her tiny hands gripping shopping bags from Gimbels, they were so different in size that they looked absurd. Mom knew Peter was an amateur artist; she had once been in his apartment to admire his work. She was an amateur artist, too, and my father teased her that she had a crush since that time she went with him to Pearl Paint on Canal Street to buy more oils.

Then in 1986, everyone in my building found out that Peter was not only an artist; he was also a Nazi hunter. It was the 25th anniversary of the trial and hanging of Adolf Eichmann, and a wave of newspaper articles accompanied a special exhibit at the Jewish Museum. Peter the elevator charmer was none other than Peter Malkin, the former Israeli spy who snatched Eichmann off an Argentine street in 1960. Eichmann, of course, was at that time the most wanted Nazi at large — an ardent believer in the Nationalist Socialist agenda, and a former architect of the Final Solution as the SS Obersturmbannführer in charge of Jewish affairs.

After the excitement those articles caused, he got a book deal. “Eichmann in My Hands” (Warner, 1990), co-written with Harry Stein, shed more light on his role in the capture of Eichmann. Here he claimed that he had been a Mossad agent for 28 years but never killed anyone. Mom wondered if I, too, wanted to read the book, but I was just post-college having fun, and the Holocaust was far off my radar. That sentiment annoyed her greatly.

I recently thought of Malkin again while writing other Lower East Side stories. I tried to find his old book on my bookshelf, but then remembered it was one of the books my husband made me give away after insisting I was a book hoarder and promising I would never miss it. I walked to Strand to see if the store had it. It did, one copy. Signed by Malkin.

I sat in a Broadway cafe with a friend who was amused by my excitement at Malkin’s scratchy signature: “Who? Should I know of him?” Now I was determined to really get to know my elevator companion whom my mother so admired. If I hadn’t appreciated him before, I would do so now.

Peter Zvi Malkin was born in 1927, in a village in Eastern Poland that had roughly 1,400 Jews before the Holocaust, nearly 70% of its population. He had a few persistent memories of that time, including a one-door, one-window heder, a tiny school.

Then, in 1933, when he was almost 5, his family moved him to Haifa, to escape rising anti-Semitism. His parents also took his brothers, Jacob, 6, and Yechiel, 17, leaving behind their eldest child, 23-year-old Fruma, a blue-eyed blonde who lived next door and was a second mother to Peter. She and her husband had three children, but her son Takele was closest to his age; the child was his daily playmate, and his best friend.

Poland in these uneasy times had an exit visa shortage, and cutting through red tape required money the family did not have. Fruma pleaded with her parents to save funds, and she promised they would reunite in the Holy Land shortly. Her parents acquiesced. In his memoir, Malkin recalled boarding a ship, and in British Mandate Palestine he entered a strange new world of foreign sounds and tastes, like oranges, dates and prickly pears. His father and his elder brother found work making bricks in Haifa — and by 1938, with news in the papers worsening, Malkin’s mother was making desperate trips to the local government department to, once and for all, get her daughter and grandchildren out.

Young Peter was a risk-taking kid, often exploring where he should not. People noticed, people talked, and soon someone at Haganah, the pre-state underground militia, heard about his exploits.

In 1941 he was selected at the tender age of 14 to join its secret ranks. Here, he got intensive training in explosives. After the final year of British rule, the group became the core of the new Israel Defense Forces — and with Malkin’s proven knack for detonating bombs, he was a sapper during the Israeli-Arab war of 1948.

A year after Israeli independence in 1948, Malkin joined the Mossad, Israel’s new Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations. Concurrently, he joined the Department of Internal Security, known as Shin Bet. He artlessly wrote on his application “I like adventure” as his main reason for applying, and despite eyebrows lifted at that answer, they offered him the job, starting at $40 a month. Safecracking and explosives were his fortes, and he trained in many more specialized skills. His cover was as an artist who traveled for inspiration, but he actually took art very seriously, having started painting at 16.

While spying, Malkin often drew stained-glass windows in churches. “I spent a lot of time in churches,” he said in one interview. “If you go to a synagogue, someone is always asking if you’re alone, if you’re married. In a church, in a hundred years no one would ask.”

At the start of 1960, Malkin was debriefed on his latest assignment, which shocked even him. He was to capture Adolf Eichmann. The new mission was called Operation Attila, and Attila was Eichmann’s code name. That May, Malkin and six other Israeli men flew to Buenos Aires, where the Mossad believed it had pinpointed Eichmann’s whereabouts. Mossad’s headquarters in Tel Aviv decided that Malkin would lead the capture, but then another agent would take over interrogation.

How had Eichmann gotten here?

After the collapse of the Third Reich, he was briefly caught, but in 1946 he had escaped from captivity in the United States and spent years hiding in Germany. In 1950, Eichmann went to Italy under the assumed name of Ricardo Klement, but only after a monk got him a Vatican refugee Red Cross passport. On July 14, 1950, he disembarked in Argentina, and for 10 years he worked in a variety of jobs in Buenos Aires. Eichmann was briefly a gaucho.

In August of 1952 he was joined by his wife, Vera Lieble, and his sons, Klaus, Horst and Dieter: The sons were instructed to refer to him as Uncle Ricardo. The Eichmanns had a fourth son while living in Argentina, Ricardo, who reminded Malkin of his lost blond playmate, his sister’s son Takele.

Lothar Hermann was almost blind, and became the unlikely source who had put the Mossad onto Eichmann. A former dissident and a Dachau camp survivor who, after Kristallnacht, left Germany for Argentina, Hermann had lost his sight, the result of severe beatings from the Gestapo. The family lived as non-Jewish Germans, and his daughter, Silvia, knew Eichmann’s eldest son, Klaus, who still used the family name Eichmann at his father’s insistence, even though Eichmann himself went under Ricardo Klement. One day, in an outdoor restaurant, Hermann and his daughter sat down at the table next to Eichmann and Klaus, and Silvia Hermann decided to make introductions. Her father may have been blind, but he had seen Eichmann when imprisoned and had heard his voice. He immediately contacted both German and Israeli authorities about this suspicious “uncle” and they sent someone to investigate in January 1958. After a quick inspection of the unimpressive middle-class Olivos neighborhood where the suspect was dwelling, the Mossad discounted the intelligence; it seemed impossible for a once lofty Nazi to be living there.

In 1960, a new Mossad team found that the man was still living in Buenos Aries, and still under the alias Ricardo Klement, but now renting an even more unimpressive suburban home on Garibaldi Street in the dreary suburb of Villa San Fernando. Hiding near a creek, the team spied on Attila, a thin man in thick black-rimmed glasses. The weather was not kind and they were often cold, as none of these crackerjack minds had realized that May was the start of winter in the Southern Hemisphere.

Through his field glasses, an agent observed a celebratory family dinner March 21 and did the math: The Klements’ anniversary celebration corresponded to what would have been the Eichmanns’ 25th, “silver” anniversary. Attila unfailingly returned home by the same bus each evening from his administrative job at a Mercedes-Benz factory; the bus arrived at his stop at around 7:20. The snoops were increasingly sure that Atilla was Eichmann, and that getting him when he was near the bus stop was the best plan of action. They decided on May 11 as the day it would all go down.

On this cold, rainy day, the green-and-yellow commuter bus pulled up on Eichmann’s stop along Route 202. Atilla did not get off. But minutes later, a little past 7:30 a.m., the next bus arrived.

Malkin wore fur-lined leather gloves so as not to have to touch the man during the scuffle. He wrote, “The thought of placing my bare hand over the mouth that had ordered the death of millions, of feeling the hot breath and saliva on my skin, filled me with an overwhelming sense of revulsion.” “Un momentito, Señor,” Malkin said, using the Spanish phrase he had practiced for this moment.

Unarmed, he grabbed Atilla’s right hand, spun the man around by the shoulders and pinned his arms behind his back. The man’s scream was piercing. Malkin pressed his hand over his mouth. Atilla’s false teeth dislodged. The leather gloves were quickly “soaked through with his spittle.” He took him on his shoulders, and spirited his target into a waiting black Mercedes-Benz. A fellow spy drove them both to a “safe house” in a rented villa 90 minutes south, in a more upscale neighborhood in the Florencio Varela district, where there was a garden with Moorish arches, a plush carpet and a stone wall to keep out nosy neighbors. In the safe house, Atilla denied he was Eichmann even as the doctor quickly examined his mouth lest he had poison hidden on him. Then Atilla was checked for a scar of 3 centimeters beneath the left brow, two gold bridges in the upper jaw, a rib scar of one centimeter, a Secret Service tattoo, his shoe size and other markings.

“You have SS number 45526?’ Mossad interrogator Hans asked Atilla.

“No! 45326.”

The men were startled.

“Was ist deine name?” another agent named Zvi Aharoni demanded.

“Ich bin Adolf Eichmann.”

In a small bedroom, a blanket concealing the only window, Eichmann was blindfolded and manacled by his ankle, in striped pajamas. Hans worked on him to see if he knew where other prominent Nazis were hiding, including Josef Mengele.

At night the spies stayed inside in the villa. As the team whiled away the hours with chess and cigarettes, a female agent arrived to cook and clean. In the pre-PC era when he got his book deal, Malkin wrote that the men had hoped for a sexy woman to arrive and change the atmosphere. But instead they had been sent Rosa, a chunky Orthodox Jewish spy whom he knew back from Tel Aviv. Oh well, at least now they had a cook. Eichmann ate only kosher food during his 10-day stay in the safe house.

Malkin was assigned to feed and shave the prisoner, and to make sure he moved his bowels. He also oversaw his deep knee bends — Eichmann had to stay in shape to survive the trial. While Malkin sat in the room on his shift, he began to secretly draw him, using the sketch pencils, acrylic paints and makeup he carried in his disguise kit. All he had in his possession was a South American travel guide he had purchased for the trip. He used its map-covered pages for a canvas.

He had plenty of time alone with Eichmann over 10 days, and he surreptitiously began with a black-and-gray portrait overlaying a map of Argentina. On the next page, he imagined him in SS regalia. “I continued drawing in a kind of frenzy. Now I had him watching a railroad train, counting the cars; now in abstract, lying prone atop a flatcar, bearing a machine gun; now, on facing pages, appeared Hitler and Mussolini; now my parents and, in muted pastels, her eyes immense and brooding, my sister,” he wrote. The Mossad wanted Eichmann to sign a form saying he was traveling to Israel on his own accord. He would not sign for Hans, who had spoken to him so harshly. Malkin decided to give it a try, never admitting he chatted regularly with Eichmann, partly to understand the mentality that had sent millions, including 150 of his relatives, to their deaths. They spoke in broken German and a half-Yiddish that Eichmann understood well. The man who had a master file he labeled “The Final Solution” maddeningly claimed he was no anti-Semite, that he even studied Hebrew with a rabbi in Berlin. To study how to kill them better, Malkin suggested.

“I have nothing against the Jews,” Eichmann insisted. This did not sway his guard, who had lost so many relatives. “On the contrary, I love Jews.” To add insult to injury, Eichmann went on to recite the Shema: “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One…” He asked to be tried in Germany. “You must be tried in Israel,” Malkin told him. He told him that if he signed, his wife and little ones could come to the trial. (This actually happened in Ramale Prison on April 30, 1962, and Vera Eichmann’s visit was revealed only recently.)

Eichmann called Malkin by his agent code name, Maxim: “Do you dance, Maxim? Do you like music? I hope you like Viennese waltzes.”

“We found ourselves co-conspirators of a sort,” Malkin wrote. “He knew as well as I did to fall silent at the sound of approaching footsteps.”

Malkin served him a good red wine that a fellow operative had been saving for the Sabbath, and played flamenco music on an old record player in the villa. Music cheered the Nazi. Malkin toasted him. He sneaked him a Kent. More relaxed, Eichmann confided to Malkin that he had lived in fear. “For 15 years I expected what has happened to me — and it has happened.” He also admitted that he had spoken to a fortuneteller in Argentina, who told him he would not live past 57; he believed her.

Eventually, Malkin got the signature.

With so many spies in one house, Rosa and Malkin now shared the room that had two single beds. One night, he whispered to her that he was talking to their prisoner against orders. Sympathy was an uncrossable line, and Rosa was horrified, but she listened to what they had discussed. Afterward, she scolded him: “You act like you’re in love with him!” Eventually so many emotions were brought up by the capture that Malkin joined Rosa in her bed one night, and he held the woman, clothed, in his arms, crying.

The operation to commandeer Eichmann was timed close to festivities celebrating 150 years of Argentine independence from Spain, which made it possible for the Mossad to fly the first El Al plane to land in Argentina without suspicion, even though there were no scheduled flights between the two countries. The delegation was in fact an operational cover, and included Mossad and Shin Bet security service people. Operation Atilla was so top secret that the delegation leader Abba Eban, then minister of education and culture, may not have even known about Eichmann’s capture. When Eban disembarked, he gave a speech in astonishingly perfect Spanish, after strains of “Hatikvah” played. Malkin and his spy pals were at the airport to watch. They waited for word on what day the plane was leaving, which turned out to be less than 48 hours later, on May 20. When told all was a go, Malkin quickly used his makeup kit to change Eichmann’s appearance on the flight to Argentina, dressing him in an El Al uniform as a steward. Eichmann loved being in uniform again, and straightened his posture. It was not lost on Malkin that Eichmann was leaving the country with a Jewish star on his hat. “Recognize that star?” he asked him pointedly.

As they headed to the airport, Malkin’s teammate, Dr. Klein, rolled up Eichmann’s sleeve to give him an injection. Were they killing him? No, Malkin assured him, this was the day he was going to go to Jerusalem, and they needed him as mellow as possible. Eichmann was ushered on board the El Al aircraft with the forged passport for Israeli agent Zeev Zichron. Malkin had made up Eichmann up to look like the passport photo of Zichron.

Mossad agents decided it was best to tell the other passengers on board, since it was a lightly populated flight and many of those delegates who had come for the Independence Day festivities were not allowed back on and had to fend for themselves to get home. The passengers were understandably flabbergasted that they had to book alternate commercial flights. One of the men on board, however, was El Al’s chief mechanic, who fell to pieces, having lost his 6-year-old brother in the camps. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion announced to the Knesset that Adolf Eichmann had been captured on May 23, 1960. You can imagine the hullabaloo in Israel. But there were no medals or interviews for the agents. Rather, there was absolute authority of safety rules — they were instructed to tell no one of their involvement.

In 1961, starting on April 11, Eichmann was put on a trial that would last for more than four months.

Every word of the trial was filmed to document evil that much of the world was denying. Eichmann, however, did not view himself as evil, saying famously, “Nothing is ever as bad as it appears, or one could put it another way, nothing is ever as hot as when it is cooking.” Malkin went just once to the courthouse, walked near Eichmann’s glass isolation booth, locked eyes with Eichmann and nodded. He never went back. He said he didn’t want to hear the trial.

On August 14, Eichmann was sentenced to death and found guilty on all crimes against humanity and the Jewish people.” He was hanged June 1, 1962 and his last words (in German) were: “Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria.” Eichmann was cremated at a secret location, and his ashes were disseminated into the Mediterranean Sea, beyond the limits of Israel’s official waters. No country would endure his grave, nor would his grave ever be a site of pilgrimage.

Malkin stayed mum on his involvement, but broke the rule once, in the spring of 1967, when his mother fell ill and he got permission to abandon an assignment in Athens. His beloved ima was dying in a Haifa hospital, 12 years after Eichmann’s ashes had been scattered. “Mama, I captured Eichmann. Fruma is avenged,” he told her. She did not answer. He repeated his claim. Gradually her eyes opened. Her hand squeezed his. “I understand,” she managed to say.

Well, there was one other time he let out the truth, the day he hailed a cab in New York City with a Mossad friend in the back seat. Malkin recognized a Polish accent. It turned out the cabbie was from the same town Malkin had fled as a young boy. He knew how Fruma was killed, and how all the others in town met their deaths. In 1941, he said, the Jews in town were rounded up near the fountain, then taken to a camp outside Lublin. The driver had survived as a slave laborer and escaped, but not before the man had witnessed Eichmann making rounds. His seatmate poked him and whispered, “Are you going to tell him?” No, he could not. He left the cab and turned back to see his friend talking to the driver, who was now looking his way, wonderstruck. The driver called out, “Is this true?” Finally, Malkin called back, “Yes!” The driver gave Malkin’s Mossad friend back the cab fare. He could not take any money — his passenger had already repaid all Jews a thousandfold. By most accounts, by this time he was already the most successful agent in Israel’s history, the Jewish James Bond. After he caught Eichmann he also nabbed Israel Baer, the Soviet mole whom the Russians had sent to Israel. Baer had claimed to be born to Austrian Jews. Malkin was rightfully proud that he clandestinely acquired a list of ex-Nazi nuclear scientists collaborating with the Egyptians. He once eavesdropped on a meeting of Arab officials by hiding under their conference table. He eventually rose to become chief of operations in the Mossad.

But he did not work for Israel only. On Malkin’s passing in 2005, Robert Morgenthau, now a renowned former Manhattan district attorney, said of my neighbor, “I think he was the outstanding intelligence agent of the 20th century.” Starting in the late 1970s, Malkin assisted Morgenthau on several investigations, including one involving CIA agents suspected of selling weapons and explosives to Africa. In addition to consultant fees, Morgenthau repaid Malkin by expediting his green card.

Not all Peter Malkin anecdotes are so heavy: I chuckled reading how he once used his expert disguise gifts on his mother before a mission; he arrived at her Sabbath dinner in Haifa, pretending he was a foreign student who showed up at her door at the request of her son. Via an unspecified spy apparatus, he changed the sound of his voice and the appearance of his mouth. For several minutes he had her convinced, but then she realized who was really sharing challah with her. “You are going to kill me!” she cried. However, further in the meal his mother guessed that he was going away on a top-secret mission. “Even a secret agent,” he said, “can’t lie to a Jewish mother.”

In the spring of 2005 I first found out that my own mother had stage IV ovarian cancer, a disease she would battle for the next two years. At the time of the diagnosis I was working on a book with her, a funny novel about the members of her retirement club, the Happiness Club, who were always complaining about their children not coming for a visit. She had taken notes on several Happiness Club members, including a Holocaust survivor named Irene Zisblatt, whom she recorded in the late 1990s for the Century Village retirement newspaper she edited, the Hawthorne Herald. She asked my brother and me to turn the newspaper article into a documentary. We were insulted that she was suggesting our next film together. Spielberg saw value where we did not, and Zisblatt’s story was included in the documentary he produced, “The Last Days,” which won an Oscar in 1998. The second it won, the phone rang — “Told you so,” my mom said.

I laughed again about that call so many years later. My mother was right about bothering to get to know your neighbors, and your duty to the future if you are a storyteller.

The other day, while my daughter did her eighth-grade homework, I rode the elevator to Malkin’s old floor and rang his doorbell. A middle-aged woman whom I have seen in the laundry room but had never spoken to answered.

I explained what I was writing. “Oh I recognize you,” she said. “You have a young daughter, right? A teen. An Australian husband?” She introduced herself for the first time: Irena Nuic-Werber. She was in real estate. She briefly asked me to wait, as she wanted permission to participate in my article by name, for normally she and her husband are very private people. Yes, her husband Daniel was quite honored. He felt it was important to help celebrate Malkin.

“When we bought [the apartment,] there was his art up to the ceiling — vibrant colors, red, yellow, orange. Many of his artworks were painted on maps. It was breathtaking,” Nuic-Werber told me. “We did not meet him, obviously, but we bought from an attorney who knew him well, who had stories. We were very touched to live here, as much of my husband’s family perished in the Holocaust.” Tears welled in her eyes. “We think of his apartment as a sacred place,” she said, “In Israel, you know, he is very famous. I wish he was more well-known in America.”

###

#oscar isaac#peter malkin#operation finale#adolf eichmann#laurie gwen shapiro#article#forward#true story

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

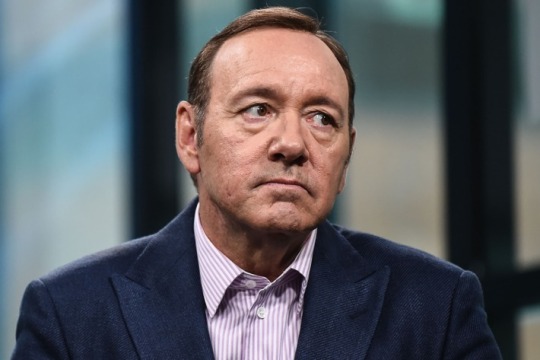

No Heroes Left: How I Was Fooled by Kevin Spacey

He’s plastered on my wall, he wrote me a letter to say thank you, and I saw him perform on stage. To have your hero disgraced is to almost hear him deceased. And rightly so. My sense of utter betrayal and unmitigated anger will never match those who were abused by Kevin Spacey. I’m even starting to think if eulogising the man is a good idea, but it’s a good lesson in how idolisation can destroy your perception and feed their image. Congratulations Mr. Spacey, you made me feel like an outright fool.

Fans of Kevin Spacey, like me, were seduced by his magnetism. A magnetism which was not so much through versatility, but by his own persona. It’s how we all identified him: the lather-like voice, a snide head-tilt now and again, and a commanding theatrical presence which yelled, “Look at the professional!”

Looking through the allegations thus far, the narrative is painfully there: a young person looks up to Kevin Spacey, Kevin plays with his own standing in the industry, plays out the slippery act, then he just can’t help himself. The Anthony Rapp allegation took place in 1986 (the year Spacey got his first significant film role as a mugger opposite Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson), and the latest allegation being July of last year. But hey, why does your conscience need to kick in if no one has found out? For someone predatory, like Spacey, it’s not about reflecting on the reprehensible actions. The sadness at looking at this from someone as ignorant as I am, is in looking at some of the roles he performed throughout his distinguished career. I was foolhardy enough to trace a faint association between his characters and a charismatic man.

How could I be looking at the man who brought to life St. Jack Vincennes on screen? It’s possibly my most favourite role of his. L.A. Confidential is a film I watch each year before Christmas (as the first act is set during festive season). There is one scene where once an up-and-coming young actor - who was earlier in the film busted by Spacey’s Vincennes - is broke after his arrest. He is brought before Vincennes at a high-ranking party with a proposition by slimeball rag-gossip journalist Sid Hudgens: the kid will be paid a measly sum to perform oral sex on the District Attorney. The pivotal moment in L.A. Confidential strikes a dagger through the bravado of Vincennes. In the midst of an awkward conversation, he knows the kid is about to be sent to the dreck of Hollywood’s seedy exploitation:

“You know, when I came out to L.A., this isn’t exactly where I saw myself ending up”

“Yeah well...get in line, kid”

This scene ends with Jack hesitantly taking a $50 from Sid Hudgens to stay quiet and bust the young actor in the act. Next is a scene which gets to nub of my conflict in watching Kevin Spacey on screen now. Jack is having a stiff drink in the Frolic Room on Hollywood Boulevard. In a brilliant moment of crisis of conscience, Jack is sitting at the bar staring at a forlorn, sack-of-shit, half-drained reflection of himself. All the while, Dean Martin’s ��Powder Your Face With Sunshine (Smile, Smile, Smile)” is cruelly playing in the background. Jack takes a moment, ponders his payoff $50 bill, and then decisively takes off without finishing his shot of whisky. Unfortunately, he’s too late and before he knows it finds the kid murdered in the motel.

The rest of the Vincennes strand is not just about him trying to find justice for the kid, but it’s also about redeeming himself. Kevin Spacey is playing a character in blissful compliance, who hangs onto the glamorous side of fame, has his sham and boastful exterior peeled back, and eventually tries to do the right thing. The last two points are a bitter and hurtful contrast to what we now know.

Then we need to talk about his ideals up to the point of the revelations. He famously said, “the less you know about me, the easier it is to convince you I am that character on screen”. Fair enough. Unlike many who pushed in the press to out Kevin, I was never bothered. It seemed clear from the outset that he was never going to come out easy, so why try? Is it our business? All I wanted to hear was his goodwill toward fellow actors and actresses. He stated that one of his most personal affinities was with Jack Lemmon, who got Kevin’s start in Broadway and taught him to pass the buck should the time arise. Kevin co-starred with Jack in the revival of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, at the same time the alleged abuse began - in 1986. It’s hard to grasp what would’ve been a sublime watershed moment for Spacey, it occurred at the same time he decided to make non-consensual advances toward a fourteen-year-old.

Kevin was never shy to present himself as a man of theatre. Imagine my excitement when I was fourteen. I was walking toward the junction of Waterloo Road and The Cut. My uncle pointed at The Old Vic and told me Kevin Spacey was about to become the new artistic director. Suddenly, the location lifted above the ground and felt the like centre of the world. My hero, Kevin Spacey, was only a commutable distance away. I remember sitting in a cafe on Baylis Road, not even half paying attention to what my uncle had to say. I kept staring at The Old Vic.

The next year, I was able to watch Kevin Spacey for the first time on stage. He was acting in a little play called National Anthems (American Beauty-lite). Arriving at The Old Vic gave me the most severe case of butterflies. The pedigree and aforementioned magnetism of the man was too much to handle before the curtain rose. I couldn’t lend an ear at that moment. At this time, I probably doubt I could love my mum as much as I could love Kevin Spacey. When he took to the stage, it was distracting. Instantly looking at the flesh of your idol, and in my mind I started cataloguing his screen roles. It was his screen material battling against his physical stage entity. It was fascinating.

Afterwards, I went home with an almost devout admiration for Kevin Spacey. He even took the time to sign autographs at the stage door. As his tenure at The Old Vic wore on, I saw him in more productions such as The Philadelphia Story, Richard II, I saw him return to Eugene O’Neill in A Moon for the Misbegotten, and David Mamet in Speed-The-Plow. I even went to see Robert Altman’s bash at Arthur Miller’s Resurrection Blues - a production so barbed with bad reception, it was closed after just three weeks.

When Kevin’s incumbency came to an end, he raised The Old Vic from a marginal theatre south of the Thames. I felt a sense of pride, and slight smugness against the naysayers. Granted his stardom brought more punters, but so be it. Especially when the competing theatre is the National just a few blocks away. He popped along to acting workshops ran by the NYT, he went on Parkinson (our premier talk show at the time) to promote theatre as being like watching a sport, and he had his own foundation to support talented young actors.

As time wore on and as I climbed out of adolescence, my Kevin Spacey fandom gradually became more muted. To me, Kevin was more of a showman and his shtick became less to marvel at. Nothing quite matched his enigmatic and cool characters in the Nineties. One of my favourite films is Seven, and I’ll never forget his entrance: he practically shouted at the top of his lungs that he arrived on screen. He lived up to the exceptional and tactile craft of that film. But maybe that’s what happens when you grow up; you tend to get these sorts of affections towards your idols, and then have a reality check.

However, it did not escape the influence Spacey had on many people like me, and unfortunately to those who had stayed silent for too long. I cannot imagine how devastating a sexual violation must be, at the hands of someone we thought we could respect. And of someone who had the gall to try and play his “coming out” as being connected to his predatory behaviour. As many commenters have already pointed out, this could only serve as fuel to the bigoted myth that gay people are sexual predators.

This, above all, is our own doing. And, admittedly, my doing. We’ve let the victims down. Back in 2005, Kevin filed a false police report that a mugger in Clapham Common assaulted him in the early hours. Before the metropolitan police were about investigate, he later changed his story to that of ‘he tripped over his dog’. I remember people telling me this sounded dubious. After all, Clapham Common has a reputation in the community for men exchanging sexual favours. He might’ve been embarrassed, but why was he quick to change his account? Was there shame? Maybe it was something else. After what we’ve heard, who’s to say he was the victim? At the time I didn’t want to hear it; because heroes don’t lie, they’re not amoral, and they don’t prey.

It’s worshiping heroes that set us up for crushing disappointment. We see it everywhere, and with social media we can get our undies in a twist loud and proud. My attitude was the reason why it took long for someone to pluck the courage, and peel back the illusion that Kevin Spacey is an extension of his mesmerising characters. As I type this, a breaking story has popped up that twenty people have now testified that inappropriate behaviour occurred frequently at The Old Vic. Of course every new detail is a blow to what I thought I believed in, but at the end of the day, I’m glad this is happening. Stardom should never, EVER be a tool against anyone too intimidated to raise their hand. This is a long time coming for the victims. If we think our sacrifice is grave, beg to think about the person who is trying to quell back the tears at night, staring at the ceiling, alone in the world. All the while, Kevin Spacey chucks the script and waits finish his shot of whisky at the bar.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with recent writer-in-residence, Dana Grigorcea

Dana Grigorcea was born in Romania in 1979 and now lives in Zürich. She studied Dutch Philology, Theater and Film Directing, and Quality Journalism. Dana worked in the media industry in Austria, Germany and France. Among her German novels are Baba Rada (2011), Das primäre Gefühl der Schuldlosigkeit (2015), and Die Dame mit dem maghrebinischen Hündchen (2018). She has been awarded several prizes, including the Schweizer Literaturperle and the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize, and was shortlisted for the Swiss Book Prize 2015.

Your recent books include a novel (An Instinctive Feeling of Innocence), a novella (Die Dame mit dem maghrebinischen Hündchen), and a book of non-fiction (Über Empathie oder Macht uns die Kunst zu besseren Menschen?). You’ve also published children’s books. How do you choose what format your next book will take, and where do you draw inspiration from?

I write about topics and stories I find pressing: about the search for meaning, sense, and sensuality; about the search for home and the loss of all certainty; about fear and overcoming it. I strive to find the right tone, the right form for every story. In An Instinctive Feeling of Innocence, the story of a love triangle unfolds alongside the story (and history) of Bucharest, in dramatic as well as comic episodes—so it had to be a novel. Die Dame mit dem maghrebinischen Hündchen (“The Lady With the Little Maghrebian Dog”) is a classic love story, told in a linear narrative, and it felt natural to keep it in the short form of a novella. I also write essays, especially when German newspapers and other publications invite me to: I’m happy to express my opinions on current events, politics, and what art means to us nowadays. My book-length essay Über Empathie (“On Empathy”) is a reflection on whether art makes us more sensitive, and whether it can make us better, more empathetic people. I start out with stories from Romania and Switzerland, share some anecdotes from reading tours—including experiences in Siberia and elsewhere—and use them to explore exactly what it is that art means to us, and what it does to us.

As for the children’s books, I use them to address issues my kids have. Sometimes they don’t want to go to bed, even though they’re both exhausted and overexcited. So I came up with the story of a wolf who desperately wants to sleep, but can’t. My kids listened, then said, “But going to sleep is easy, you just close your eyes and wait a bit,” and then they showed the wolf how it’s done. That story, sparked by such a practical goal, was a hit in German-speaking countries, and the title was Mond aus! (“Turn the Moon Off!”). Then I just kept going: I wrote a haircut story for kids who are afraid to go to the hairdresser and change their appearance; then came a scratch-and-sniff book about vegetables, starring a prince who has to go to the market and cook for the princess; and a story about sibling rivalry in a flower garden—the fight is triggered by the big sister, who knows everything, even the names of all the flowers.

Is this your first stay in New York? What were your first impressions of the city, and has anything about New York surprised you?

This was my second visit to New York—the first time I came with my husband, the writer Perikles Monioudis, who knows the city well. He’d come shortly after 9/11 to write a book about the aftermath, and the city’s indestructible spirit. I feel like I know the city pretty well, too, from movies and literature—every time I turn the corner I recognize something, everything’s so familiar—and yet at the same time I’m always surprised that it actually exists, that it’s not just a figment of our collective imagination.

You were born in Bucharest, Romania and were raised bilingually. What made you decide to write your literary texts exclusively in German? To what extent does writing, thinking, and feeling in your two mother tongues differ?

I write in German because I’ve lived mainly in German-speaking countries for about twenty years now, and because I want to write in my readers’ language and hear their reactions firsthand. I also love the language because it allows for such long sentences, and exploiting its elastic syntax can turn sentence construction into an amusing game—I like getting to the last word, the verb, without losing the thread. The German language helps me structure the plot, too: much like with its syntax, you can weave in and out and maybe get a bit sidetracked, but what you’re writing still has to make sense and, in the end, get to the point—period.

In translation, my sentences are often halved or even quartered, depending on the language. In Romanian and English, for example, people usually communicate more concisely, in tighter sentences—anything else sounds like blabber or sheer delirium.

Here I’d like to acknowledge my English-language translator, Alta Price, who managed to faithfully convey the atmosphere of my Bucharest novel An Instinctive Feeling of Innocence in English. Translation is a high-wire act that requires intuition and precision, and only real artists can pull it off.

One of your most recent books, Über Empathie, is about the power of art and empathy. What made you want to write about this subject matter, and what role does empathy play in today’s society? What role should it play?

As an artist, I deal with the meaning of art: I write literature and travel in artistic circles, and on my many reading tours I usually meet people who hold art in high esteem. Are people who deal with art better than others, are they the more sensitive members of society? Can art transform us for the better in these turbulent times? Can it make us more empathetic? Empathetic people, who really see and respect one another, are essential to democracy. We’re currently witnessing how traditional democracies we thought were utterly stable are on the brink of being toppled. Can we effectively oppose populism, intentionally stoked fear, and apathetic individualism with art? I think so.

You participated in several public events as part of this year’s Festival Neue Literatur. What is your experience with reading your work in public and/or speaking about your books? Is this something you find enjoyable and fruitful?

The Festival Neue Literatur in New York and the Zeitgeist Festival in Washington, D.C. marked the end of my first North American book tour, after delightful events in San Francisco, Seattle, and Chicago. It seemed to me that every audience was interested, receptive, eager, and open to the humorous twists and turns of our conversations, so it was a pleasure to present the book here in the US. When you see everyone looking so busy, people rushing through the city, hurrying by with headphones on, staring at their phones and laptops—even in cafes and strolling around the park—you don’t expect to meet many people who are willing and able to spend their leisure time with a book. Reading in places like the powerHouse Arena in Brooklyn and McNally Jackson in Manhattan were a revelation to me.

The panel discussions and literary conversations were dynamic and fast-paced yet profound. My translator Alta Price was always there, and when she talked about translating my book I felt like the privileged witness of an alchemical process.

At the Festival’s opening-night event, Germanist and theatrical artist Endre Malcolm Holéczy introduced us. He’s a true man of letters, had read my book An Instinctive Feeling of Innocence quite closely, and expertly conducted a clever and entertaining conversation. His enthusiasm for the novel was, of course, extremely enjoyable.

Interview translation by Alta L. Price

0 notes

Link

Artists: Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff

Venue: The Downer, Berlin

Date: June 18 – August 1, 2020

Click here to view slideshow

Full gallery of images, press release and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of The Downer, Berlin

Press Release:

I’ve known Calla and Max for a decade now. I’ve seen the spaces that their work endeavored to create. I have happily (occasionally begrudgingly) been a part of some of their exhibitions and projects during the course of this time. I once read from receipts pictured in a series of photographs after having installed them in front of a live audience; I performed in a play they wrote and directed about an in-fighting but enterprising band of squatters who run a ramen restaurant out of an apartment they share; I helped assemble banquettes in their theater, hung and painted backdrops, operated the video camera, mopped floors, and built architectural models. I’ve sold their work to collectors and donated my own paintings to their benefit auctions. Our lives are closely connected and likely will be for their remainder. This show has nothing to do with our shared history, so I will refrain from dredging up too much more of it after this paragraph. But unlike any other thus far, this show is charged with a particular energy for me. Calla and Max had a big influence on the circumstances that brought me to Berlin, Also, it was through their initiative that the Downer began.

In my eyes, the core of Calla and Max’s work is the idea of community and shared experience. It examines the ways in which these ideas can be deployed against authority or serve to reinforce it. For as long as I’ve known them, and longer, their work has brought people together. Using friends as models, actors, performers and collaborators, they have created and fostered communities. As the complexities and personalities of those communities bristled against one another, they have likewise served as mediators, confidants and — conversely — the objects of disparagement. They have founded and operated bars, venues and theaters, with each space comprising some ratio of these component parts. Their first was a ‘bar’ in their shared studio at Cooper Union — which was more of a sculpture that encouraged people to get together and have a beer. Then followed Times Bar in Berlin, founded in collaboration with Lindsay Lawson, New Theater and TV Bar, which just reopened after a few months of Covid-19 provoked shutdown (and which you should go visit). Calla and Max’s practice is, on one hand, institutional critique and, on the other, embodiment of the institution.

The series of photos that I installed and read from in 2013 pictures artists sorting through their receipts, presumably in preparation to submit them to the tax office. The photographs don’t picture the artists themselves, just out of focus glimpses of them in front of or behind receipts piled on kitchen and cafe tables. Each piece was given the instructive title of the artist’s first name, the city (always Berlin) and a period of time (i.e Spring 2013). In a simple gesture the gut-leadening feeling of dealing with anything related to taxes is communicated. For artists and artworkers in particular, who exist in an industry where passion for art is often exploited to extract unpaid labor, the quarterly conundrum of what is and isn’t a warranted write off is evoked. Was that book for enjoyment or research? Was that dinner business or pleasure? Should I have been paid for this or was I volunteering? Where do fun and labor coincide and how can they be properly distinguished when friendships blur into professional relationships? This anxiety isn’t really related to taxes — that question is quickly answered with, “write off as much as you can get away with” — but these photos indicate a deeper existential uneasiness about the ways in which we are evaluated. Moreover, they say something about the ways in which we evaluate our own lives and work, and the relationships that often straddle the blurry boundary between them.

My definition of a scene would be: a recognizable movement in which the participants’ activities — as artists, performers, personalities, whatever, really — draw them into the same chapter of collective imagination, compounding the significance and reach of their ideas. Scenes have driven the advancement of art for a few hundred years and have been allowed to more or less write their own histories. The overlapping scenes that Calla and Max have cultivated over the past decade provided fodder for their own artistic work, as well as giving inspiration and a platform to their myriad members. Relationships extend beyond Berlin and the physical spaces they have helmed, situating Calla and Max’s work within a growing, networked alliance of artists — many of them also involved in organizing project spaces or artist run galleries.