#Chy Lung & Co.

Text

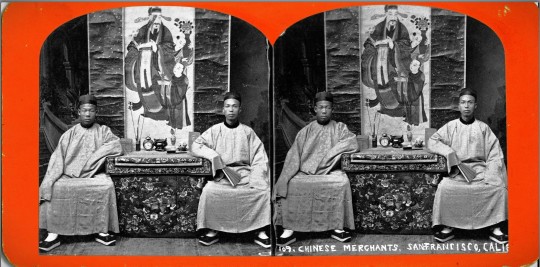

“109. Chinese Merchants, San Francisco, Calif.” c. 1890 – 1899? Stereograph by Nesemann Woods Gallery, Marysville CA (from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection of the University of British Columbia Library).

Merchants of Old Chinatown

In the late 1840s and the 1850s, Chinese merchants and traders made their initial foray into California. By February 1849, the number of Chinese had increased to 54 and by January 1850, historians would count 787 men and two women in San Francisco. In December 1849, the Alta California newspaper reported that 300 Chinese convened a meeting at the Canton Restaurant on Jackson Street for the purpose of organizing the “Chinese residents of San Francisco” and engaging the services of lawyer Selim E. Woodsworth to “act in the capacity and adviser for them.”

In his book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, historian John Tchen wrote about the vanguard of old San Francisco Chinatown’s merchant elite as follows:

“These pioneers hailed primarily from the Sanyi (Saam Yap) or Three Districts [三邑], as well as the Zhongshan area in the immediate vicinity of Canton. It's important to note that Nanhai (Namhoi) and Panyu (Punyu) stood out as the most prosperous districts within Guangdong Province. Their economic pursuits ran the gamut from cultivating fertile agricultural lands, breeding silkworms and fish, to crafting silk textiles, producing ceramics for both domestic and international markets, and engaging in various other commercial endeavors.

“What set apart the merchants and artisans from Sanyi and Zhongshan was their mastery of a more refined city dialect compared to their Siyi (Sei Yap) counterparts, who mainly consisted of poorer, rural communities. Remarkably, over 80 percent of Chinese immigrants in North America originated from the Siyi [四邑] region. A noteworthy portion of these Sanyi merchants belonged to the emerging class of compradores, individuals who facilitated business transactions on behalf of Western trading companies. These California-based Sanyi merchants thus brought prior experience in dealings with Western entrepreneurs, and California was seen as a promising arena to expand these lucrative connections.”

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May of 1869, the more sophisticated and adventurous members of San Francisco’s pioneer Chinese merchant community would begin exploring other cities in the United States in search of opportunity.

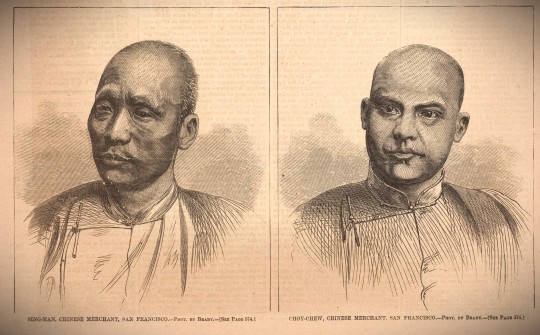

“Sing-Man, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco” and “Choy-Chew, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco,” Harper’s Weekly, September 4, 1869, wood engraving on paper. Artist unknown, artist after a photograph by Mathew Brady, 1869 (from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).

For example, in the Harper’s Weekly article (Sept 4, 1869, page 574), the reporter identified merchant Choy Chew as a San Franciscan and a talented linguist of sufficient intellect and stature to be invited to give a speech at a European-American banquet. He reportedly visited Chicago with a fellow merchant, Sing Man, before traveling to New York where the pair were regarded as “representatives of Chinese industry and commerce.”

At the banquet in Chicago, Choy Chew delivered the following remarks:

”Eleven years ago I came from my home to seek my fortune in your great Republic. I landed on the golden shore of California, utterly ignorant of your language, unknown to any of your people, a stranger to your customs and laws, and in the minds of some an intruder — one of that race whose presence is deemed a positive injury to the public prosperity. But gentlemen, I found both kindness and justice. I found that above the prejudice that had been formed against us, that the hand of friendship was extended to the people of every nation, and that even Chinamen must live, be happy, successful and respected in ‘free America.’ I gathered knowledge in your public schools; I learned to speak as you do; and, gentlemen, I rejoice that it is so; that I have been able to cross this vast continent without the aid of an interpreter; that here in the heart of the United States I can speak to you in your own familiar speech, and tell you how much, how very much, I appreciate your hospitality; how grateful I feel for the privileges and advantages I have enjoyed in your glorious country; and how earnestly I hope that your example of enterprise, energy, vitality, and national generosity may be seen and understood, as I see and understand it, by our Government …

”We trust our visit, gentlemen, may be productive of good results to all of us; that the two great countries, East and West, China and America, may be found forever together in friendship, and that a Chinaman in America, or an American in China, may find like protection and like consideration in their search for happiness and wealth.“

-- from the Scientific American, new series, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 131 (August 28, 1869)

The founding in 1888 of the Merchants’ Exchange in old San Francisco Chinatown represented the logical culmination of several decades of robust business operations by the pioneer Chinese merchants in the city and beyond.

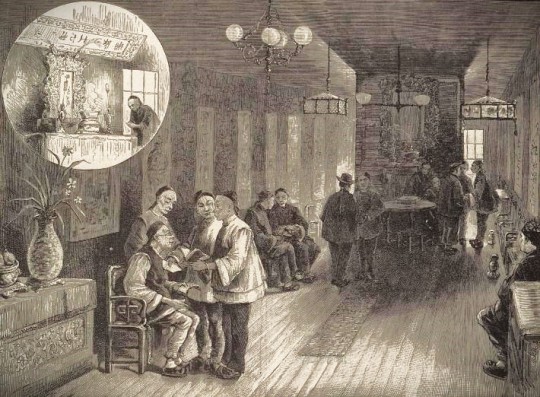

“Chinese Merchants’ Exchange, San Francisco.” Lithograph from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 26, March 18, 1882 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In his book, A Guide Book to San Francisco (published by The Bancroft Company in 1888), John S. Hittell described the Chinese Merchants Exchange as follows:

“At 739 Sacramento Street are the new rooms of the Chinese Merchants' Exchange. They are fitted up in the ordinary Chinese style, and though presenting no special attraction to the visitor, the business transacted there is of considerable importance. A Chinese merchant, contractor, or speculator never starts on any enterprise alone. He always has at least one partner, and in most cases several. He makes no secret of his transactions, but converses about them at the exchange, and often goes there in search of capital when his own means are insufficient. He sometimes applies to that institution to find him a capable man to manage a new business which he is about to start. If, as often happens, one be selected who is in debt to other members, they make arrangements which will not interfere with the new enterprise; and the debtor is not unfrequently released from his obligations.”

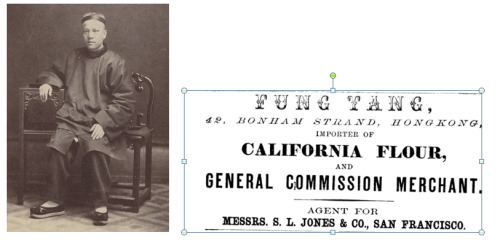

Fung Tang

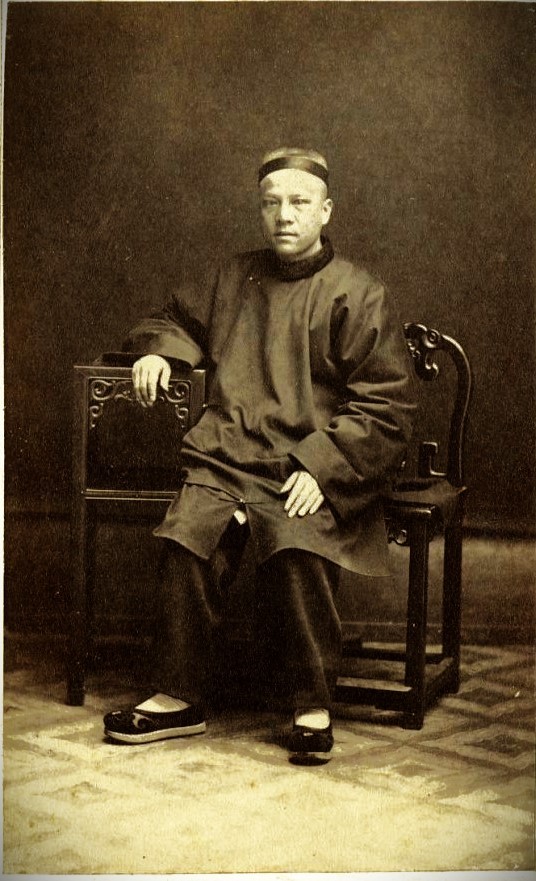

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

The address of the Merchants’ Exchange at 739 Sacramento Street was hardly surprising, as it shared the same building which had housed the mercantile house of a legendary merchant, Fung Tang. Historian York Lo, in his article for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, described Fung as “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the pioneer Chinatown photographer, Kai Suck. A professional studio portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. In fact, Fung appears to have deployed the same portrait now reposing in the collection of the California Historical Society as part of his commercial advertising in Hong Kong.

An advertisement for Fung Tang’s flour import business in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service, including his election to the board of directors of the Tung Wah clinic (the original predecessor organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encouraged to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

Tchen asserts that the influx of British and other Western imperialist powers into China’s major treaty ports transformed the status of merchants engaged with Western trading companies. Rather than operating on the margins of Qing-era society, the merchants gained unprecedented prestige and influence. Beyond China's borders, they experienced far more freedom to engage in trade and amass substantial profits without the worry of state-imposed restrictions. They rapidly acquired the necessary language skills and business acumen to navigate their newfound opportunities.

San Francisco’s early Chinese merchants swiftly grasped the English language and American business practices, excelling in American-style transactions, and developing strategies for fostering positive relations with the general San Francisco populace. The local press affectionately labeled them "China Boys." They made conscious efforts to participate in the celebrations of significant American holidays, further endearing themselves to the San Francisco community.

This approach significantly bolstered their rapport with the local population, as evidenced by the California Courier's glowing praise: “We have never seen a finer-looking body of men collected together in San Francisco. In fact, this portion of our population is a pattern for sobriety, order, and obedience to laws, not only to other foreign residents, but to Americans themselves," declared Cornelius B. S. Gibbs, a marine-insurance adjuster, in 1877. Gibbs emphasized the high esteem in which Chinese merchants were held among white business circles. “As men of business, I consider that the Chinese merchants are fully equal to our merchants. As men of integrity, I have never met a more honorable, high-minded, correct, and truthful set of men than the Chinese merchants of our city.”

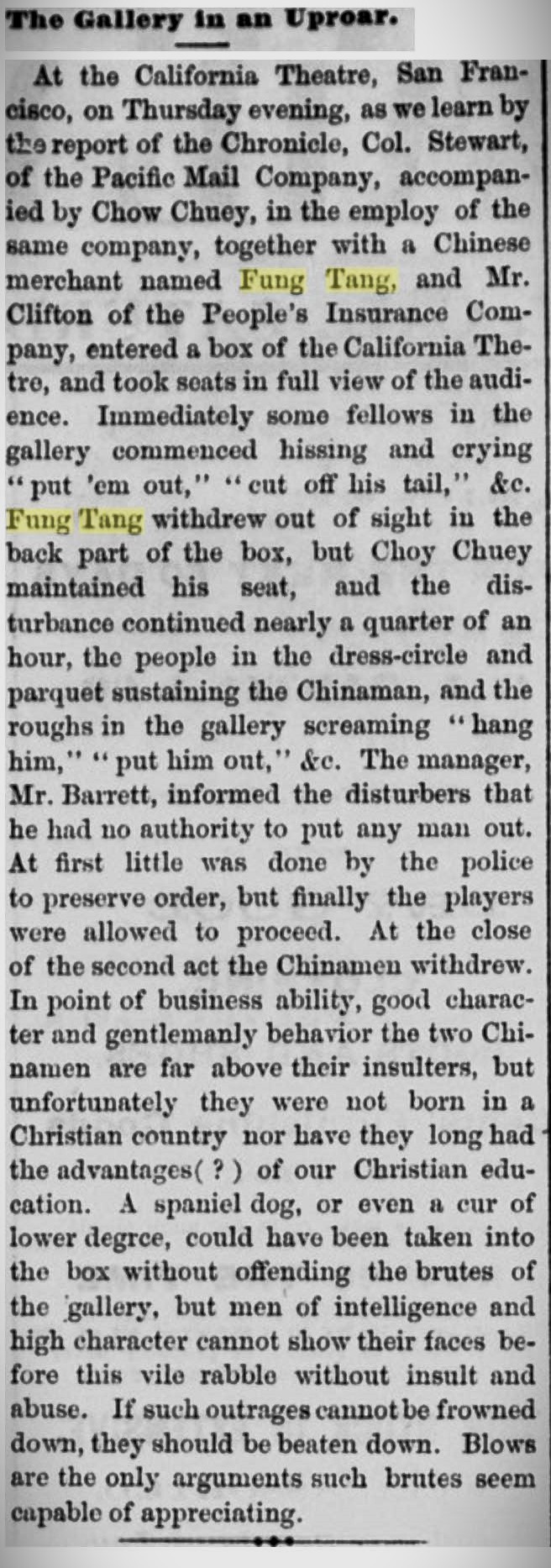

Attempts to participate in mainstream society, however, were not always welcomed by lower-class elements of white society as evident in this news account about Fung Tang’s appearance in San Francisco’s California Theatre in September 1869:

Clipping from the San Jose Mercury News, September 18, 1869 (vol. I no. 42)

Fung Tang’s transpacific success in San Francisco was hardly unique among the ranks of Chinatown’s early merchant class. He exemplified the business acumen of his fellow pioneering entrepreneurs and their establishment of transpacific trading posts in strategic locations.

Lai Chun-chuen and Chy Lung Co.

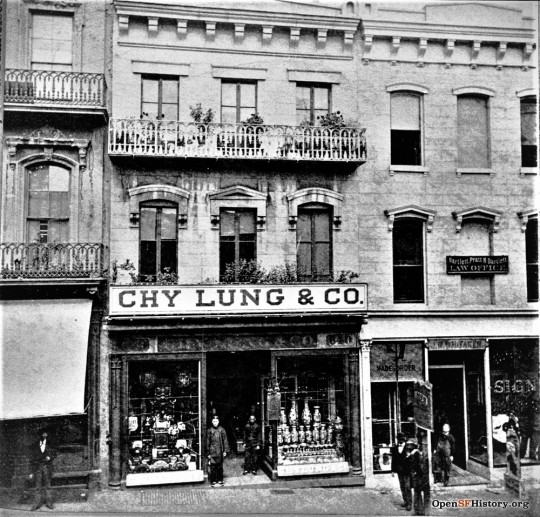

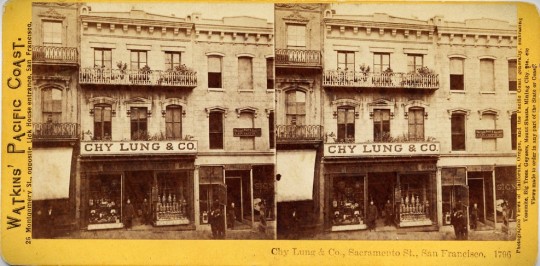

The story of the pioneer business of Chy Lung & Co. predates the history of San Francisco Chinatown itself, and its establishment spurred the rise of Chinatown’s first commercial strip, Sacramento Street (唐人街; canto: “Tohng Yahn Gaai”) or “Chinese Street.”

An enlargement of the stereograph taken by Carleton Watkins for the Thomas Houseworth & Co., and “[e]ntered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the Northern District of California.”

“Among the early Chinese settlers were merchants like Lai Chu[sic]-chuen,” the late historian Judy Yung wrote in her pictorial book, San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America). “Upon arrival in 1850, he opened Chinatown’s first Bazaar at 640 Sacramento Street, importing teas, opium, silk, lacquered goods, and Chinese groceries.”

"Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796" c. 1866. Photograph by Carleton Watkins for his Watkins' Pacific Coast stereograph series (from a private collection).

Chy Lung’s founder, Lai Chun-chuen (a.k.a. Chung Lock), came to San Francisco in 1850 from Nam Hoi county. According to UC professor Yong Chen, the business founded by Lai and, his partners Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu, appear in the earliest business directories for San Francisco. A “Chyling, china mer, 188 Washington” appears in the Parker directory for 1852-1853. The Colville’s directory of 1856 lists a “Chy Lung (Chinese) mcht, Canton Silk and Shawl Store, 166 Wash’n,” and the business would remain on Washington Street (moving to 612 Washington St. by 1858) until 1863 when it relocated to 642 Sacramento Street. By 1865, the Chy Lung & Co. had either expanded or taken over the address of 640 Sacramento Street.

Portion of the stereograph “No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co.,” c. 1866. Published by Lawrence & Houseworth (from in the collections of the Society of California Pioneers, Wells Fargo Corporate Archives, and the Library of Congress).

“He imported Chinese prefabricated houses and cargoes of Chinese goods, teas, silk, lacquer and Porcelain wears, and even opium,” historian Phil Choy wrote. “The drug that made American merchants millionaires in the China trade now found its way to California for both the Chinese and American markets Chy Lung was one of only two Chinese businesses at the time that advertised in an American newspaper, the Daily Alta California.”

“No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento Street.” c. 1866. Published by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from in the collection of the New York Public Library).

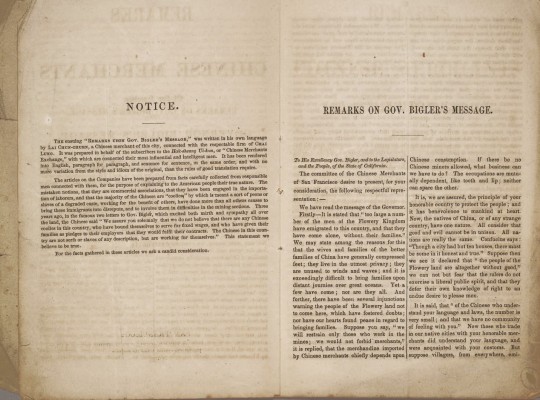

Lai Chun-chuen is remembered not only for his business acumen but also as the principal author of the objections to the anti-Chinese movement in California and plea for civil rights as published in the pamphlet, Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco, upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections (San Francisco: Whitton, Towne, 1855).

The preface to Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections of 1855 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The second line of the first paragraph identifies Lai Chun-chuen as “a Chinese merchant of this city, connected with the respectable firm of CHAI LUNG.”

Chy Lung & Co. continued to play a leading role in the Chinese merchants exchange until Lai Chun-chuen’s death on August 30, 1868. The business remained a fixture of the Chinatown business community for the rest of the 19th century, and it adopted the new communications technology of the telephone, as shown by the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902.

The listing for Chy Lung & Co. as it appeared in the Wells Fargo directories of Chinese business for 1878 and 1882.

The Chy Lung & Co. business, and others established by Chinatown's merchants, soon comprised a source of both tangible and symbolic power within the rapidly growing Chinese community in the American West. As the Chinese immigrant population swelled, businesses catering to their specific needs diversified and expanded. A hierarchical structure emerged, influenced by both economic factors and the district of origin. The wealthier Sanyi individuals typically presided over larger, commercially successful enterprises, including import-export firms. Those from the Nanhai District dominated the men's clothing and tailoring sector, as well as butcher shops. The neighboring Shunde District populace exercised control over overalls and workers' clothing factories.

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

Meanwhile, Chinese hailing from the Zhongshan District, which represented the second-largest Chinese population in California, were prominent in the fish and fruit orchard businesses, as well as in the production of women's garments, shirts, and underwear.

"Quan Quick Wah"

“Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). A descendant of the large, confident man shown in traditional robes identifies him as San Francisco merchant “Quan Quick Wah.” Based on other photographs of this Chinatown location, the pair appears to be walking on the west side of Waverly Place toward its intersection with Clay Street. In his book about Genthe’s Chinatown photographs, historian Jack Tchen wrote about this imposing figure followed by a bodyguard as follows: “The powerfully built man dressed in traditional silk robes has been described as a tong leader. Whether he was a tong leader, a wealthy merchant, or both, his dress and carriage convey a strong presence. Tong leaders came to rival the power of wealthy merchants. The man following the merchant or tong leader is said to have been his bodyguard, protecting him from the attack of a rival tong. In the photograph the two are passing under ornate cloth lanterns that indicate a pawnshop business.”

"Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). This full photograph in the Library of Congress shows that Genthe’s image fortunately included a portion of the sign for the entrance to a basement restaurant. The signage (which appears in other photographs of this area), indicates that the merchant and bodyguard were photographed walking on the west side of Waverly Place (at about no. 23 and 25 Waverly) and toward the southwest corner of its intersection with Clay Street. Tchen’s guess that the background store frontage was a pawnshop is probably correct, as the “Qung Hing Art Co.” pawnshop occupied space at 25 Waverly during the 1890s. The headquarters of the merchant-controlled, Ning Yung district association was located at 23 Waverly.

Yee Ah-Tye

In old Chinatown, merchants’ personal use of bodyguards or alliances with fighting tongs were common. The organization and fragmentation of district and clan associations, along with sharp business competition, often placed lives, as well as livelihoods, at risk. For example, the Kong Chow association traced its origin to about 1853, when the influential community leader, Yee Ahtye (a.k.a. “George Athei”) persuaded members of his Yee clan of Sunning, which had remained in the Sze Yup Co. (after a number of clans split off to organize today’s dominant Ning Yung Association), to finally secede. The action by the Yee clan was joined by clans from Hoiping and Enping counties after a dispute over the presidency of the Sze Yup Co. in 1862. The resulting new association, the Hop Wo, soon challenged the merchant Ah-Tye for the custody of a piece of land on which Ah-Tye had allowed the Sze Yup Association to build a headquarters building. Yee eventually deeded the land to a new Kong Chow Association, which his fellow Sunwui merchants founded in 1866. The dispute over this property raised to such a level that Yee and his associates were compelled to organize a secret society, the Suey Sing Tong, to protect the asset and enforce his decision.

Portrait of Yee Ah-Tye (courtesy of the Chinese Six Companies). Yee was an elite merchant of Chinatown and was considered a co-founder of the Suey Sing Tong.

Born around 1829 in Guangdong province, Yee Ah-Tye had arrived in San Francisco just before the gold rush at around 20 years old. In spite of his humble beginnings, Yee had learned English in Hong Kong and swiftly ascended to a position of authority within the influential Sze Yup [pinyin: "Siyi"] Association. The Sze Yup Association, along with similar Chinese district associations, played a crucial role in assisting newly arrived Chinese immigrants during the 19th century. The organizations provided accommodation and job opportunities.

Aside from his many business accomplishments, Yee famously cross paths with the legendary, San Francisco madam Ah Toy. The conflict arose when Ah Toy accused Yee of demanding a tax from her prostitutes on Dupont Street. Despite her origins in China, Ah Toy had by then lived in America for three years and become familiar with its legal system. She boldly threatened to take legal action against him, a move she would not have dared to undertake in China.

The August 1852 report in the Daily Alta California newspaper highlighted Ah Toy's shrewdness, emphasizing her knowledge of living in America and her ability to navigate the legal system. She resided close to the police station, fully aware of where to seek protection, having faced legal proceedings herself numerous times. The reporter gleefully suggested that Yee use caution about overstepping his authority, warning that he might lose his dignity and end up in custody.

A year later, Yee faced legal trouble himself, being arrested for assault and grand larceny. The San Francisco Herald alleged Yee “inflicted severe corporeal punishment upon many of his more humble countrymen … cutting off their ears, flogging them and keeping them chained for hours together.”

After moving to Sacramento in 1854, Yee also relocated his business activities in 1860 to La Porte, California, where hydraulic and drift mining operations for gold occurred. Yee acquired a partnership in a store called Hop Sing & Company which supplied merchandise and Chinese contract laborers. By 1866, it was the richest Chinese store in that town, with a value of $1,500 (about $36,000 in 2005 dollars).

According to one of his descendants, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, the pioneer Yee Ah Tye reportedly lived thirty-four years in La Porte as a successful merchant, running the Hop Sing and Company store and representing the Chinese community in the area. He had three wives and four children, three of whom were girls. Unlike most other Chinese fathers at the time, he invested in the education of his daughters – he even bought a piano for his youngest daughter, Bessie, who became an accomplished pianist. As a leader in the Hop Sing Association, he founded a small hospital to serve the elderly Chinese men of La Porte.

“The temple ruins at San Francisco's Lincoln Municipal Park Golf Course was once part of the Lone Mountain Cemetery, a gift of Ah Tye,” Lani Ah Tye Farkas wrote in 2000. “Other glimpses of his life in America can be seen in deeds, mining claims, tax assessments, newspaper articles, and land that he once owned. Yee Ah Tye's legacy, however, is in his descendants. Many Chinese with common last names like Chan, Lee, and Wong may have no relationship with one another. However, the descendants of Yee Ah Tye have borne his unique last name through six generations, in the words of the Yee family genealogy, ‘spreading like melon vines, increasing continuously’” Yee died in 1896. (see: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/pc289j76z)

Contract Labor

At the lower end of the business hierarchy, the Siyi or Four District residents comprised the largest and least affluent group of Chinese immigrants. They typically occupied occupations such as laundries, small retail shops, and restaurants and the bulk of the laborers in the contract labor system.

In the period preceding the Civil War, there was a concerted effort by certain individuals to introduce contract laborers into the United States. A letter penned by C. V. Gillespie to Thomas Larkin on March 6, 1848, sheds light on this initiative. Gillespie expressed a keen interest in the idea of bringing Chinese emigrants to the country, suggesting that a variety of skilled workers and laborers could be sourced:

"One of my favorite subjects or projects is to introduce Chinese emigrants into this country,… Any number of mechanics, agriculturists and servants can be obtained. They would be willing to sell their services for a certain period to pay their passage across the Pacific…."

The practice of importing contract laborers to the United States began in the late 1840s and continued through the 1850s. However, enforcing labor contracts proved to be a challenging endeavor on American soil. A case in point involved an Englishman who, upon bringing fifteen Chinese laborers to the country bound by a two-year contract, found that they immediately reneged on their agreement upon arrival. Authorities, at the time, were reluctant to intervene in such disputes.

In 1852, Senator George B. Tingley introduced a bill in the California State legislature aimed at legalizing and facilitating the enforcement of contracts allowing Chinese laborers to sell their services to employers for periods of up to ten years at fixed wages. This proposal, however, faced significant public backlash and was ultimately defeated after a heated debate. The subsequent year saw members of Chinese companies admitting that they had initially imported workers during the early years of the Gold Rush. Yet, due to unprofitability and difficulties in enforcing labor contracts, they abandoned this practice.

“San Francisco Chinese Merchant” no date. Photographer unknown, possibly by Ann Ting Gock (from a private collection). This rare and unusual image suggests that the individual might not have been a mere merchant at all, but a member of the Chinese consular staff. He is seen wearing his 清代官帽 (canto: "ching dai gwun moe") or official's headwear. The Qing official headwear or Qingdai guanmao (Chinese: 清代官帽; pinyin: qīngdài guānmào; lit. 'Qing dynasty official hat'), also referred to as the “Mandarin hat” in English, is a generic term which refers to the types of guanmao (Chinese: 官帽; pinyin: guānmào; lit. 'official hat'), a headgear, worn by the officials of the Qing dynasty in China. The merchant is attired in a "changshan" or "changpao" or long robe. The robe worn in the photo was derived from the Qing dynasty-period "qizhuang" (the traditional dress of the Manchu people). Changshan were, and are, traditionally worn for formal pictures, weddings, and other formal Chinese events.

Credit-ticket System

Beyond the initial years, it became widely acknowledged that Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States voluntarily, free from any servile contracts or duress. Many emigrants either financed their own passage or received assistance from relatives and friends already residing in California. The prevailing method for the majority of Chinese immigrants during the 19th century was the credit-ticket system. Under this system, an emigrant would receive financial support for their passage in a Chinese port. Upon reaching their destination, the emigrant was expected to repay this debt using their future earnings. It is important to note that this system differed from the contract labor arrangement, where laborers were bound to serve for a specified duration.

The precise origins of the credit-ticket system remain uncertain. However, merchant brokers in Hong Kong were established to provide advanced passage funds, approximately forty dollars, to the emigrants. Corresponding entities in the United States were responsible for collecting these debts and aiding the newly arrived immigrants in finding employment.

Two merchants with pipes. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The stores and offices that the merchants of Chinatown had opened starting in the mid-19th century became the basis of real and symbolic power in the growing regional community of Chinese living in the American West. That power, including the ability to mobilize for social change within the narrow role afforded Chinese in the society, manifested itself in the family and district associations headed by local merchants.

“The merchant class has traditionally been the one sector of Chinese society able to foster unity and bring about social change,” wrote historian Thomas W. Chinn about the role of the merchant class in San Francisco Chinatown (and beyond). “The merchant-directors of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association must be well-established businessmen in the local community as well as outstanding members of their own family associations. They have already played a leading role in their own social circles before becoming merchant-directors, and they enjoy a great deal of respect. . . Thus the friendly corner grocer may simultaneously be the president of his family association and his district association as well as a merchant-director.”

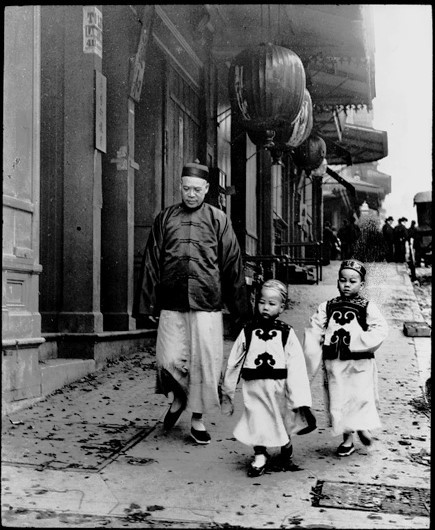

Lew Kan

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.” The photograph appears to have found the trio walking down the south side of Sacramento Street below Dupont Street.

By the time photographer Arnold Genthe had photographed merchant Lew Kan and his two sons on Sacramento Street (as well as two other earlier photos of their four sisters in Portsmouth Square), Lew had already attained legendary status as one of Chinatown’s leading merchants. Born in 1851, Lew entered the US in 1866.

Author Roland Hui (in his biography of pioneer Chinese American industrialist Lew Hing), wrote about Lew Kan and his dry goods business called Lun Sing & Co. at 706 Sacramento Street as follows:

“He started Lun Sing, one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, around 1867, a year after he immigrated to the U.S. In 1896, the business gained notoriety by harboring a young Chinese revolutionary named Sun Yat-sen during his first visit to the continental United States. Sun advocated overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing a Chinese republic. His ideas were too radical for the politically uninitiated Chinese community. Kang Youwei, the architect of the ill-fated “Hundred Day Reform” in China in 1898, favored establishing a constitutional monarchy around Emperor Guangxu. Forced into exile after the power-hungry Empress Dowager crushed his reform, Kang launched the Chinese Empire Reform Association, also known as Baohuanghui (Save the Emperor Society), the following year in Victoria, Canada. Baohuanghui quickly gained widespread support among overseas Chinese since the idea of having an emperor at the top of the social order who ruled with the Mandate of Heaven had been ingrained in the Chinese psyche for thousands of years. The San Francisco Baohuanghui chapter was founded in 1899 at 146 Waverly Place. Lew Kan supported Kang’s political agenda despite having met Sun several years earlier, and in 1901 became the president of the San Francisco chapter of Baohuanghui. Many scholars observed that Baohuanghui was the first organization that evoked the patriotic sentiments of overseas Chinese. And when Liang Qichao, Kang's most famous student, stopped over in San Francisco during his 1903 America tour, thousands of Chinese flocked to listen to his speeches. As the man who organized these community-wide activities, Lew Kan's stature and influence in San Francisco Chinatown must have been substantial. In addition, he was one of the wealthiest Chinese merchants, reportedly owning several general merchandise stores with an estimated net worth of $2 million. That was an astronomical sum in those days. In addition, he was a director of the Kong Chow Company, a district association representing Xinhui."

Decline of Merchant Influence

The organizational expression of Chinatown’s merchant elite, the Chinese Six Companies, wielded considerable authority within San Francisco and beyond. The Six Companies and its constituent district associations comprised the quasi-government of Chinese America, offering social services, mediating disputes, and representing the community's interests to external forces. With the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882, their grip on power began to weaken.

Portrait of a merchant with fan and scroll. No date, photograph possibly by Shew’s studio (based on the detail of the end-table), from the collection of the Stanford Libraries.

The decline of the Six Companies’ influence can be attributed to various reasons. One significant factor was their inability to adapt swiftly to the evolving socio-economic landscape within Chinatown. As the community faced new challenges, including the punitive extension of Chinese exclusion with the Geary Act of 1892, the Six Companies struggled to effectively navigate these changes, leading to a loss of faith among the populace in their ability to address emerging issues.

The Geary Act of 1892 extended and strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, requiring most Chinese Americans – native and foreign-born -- to carry an internal passport in the form of certificates of identity or face arrest and deportation. It intensified discriminatory measures against the Chinese community, fostering widespread discontent and resistance.

In response, the Six Companies initiated a national boycott against the Geary Act. The boycott aimed to unify Chinese immigrants and their supporters across the United States, urging them to refuse compliance with the law as a form of protest. It gained substantial momentum, with significant participation from Chinese communities in various cities, voicing opposition to the Act's discriminatory provisions.

The board of directors of the Chinese Six Companies, no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Based on the screen panels in the background (which remain in the Six Companies’ meeting hall at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco), the photo appears to have been taken after 1906.

Despite its initial vigor, several factors led to the ultimate collapse of the national boycott against the Geary Act. First, the federal government intensified its efforts to enforce the Geary Act. Authorities conducted widespread raids and inspections, threatening deportation and imposing harsh penalties on those failing to comply. The fear of reprisals and the potential disruption to livelihoods coerced many Chinese immigrants into reluctantly acquiescing to the Act's demands.

Second, the broader American society exhibited little sympathy or support for the Chinese community’s plight. The prevailing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country and the lack of significant political backing from other institutions diminished the effectiveness of the boycott. Without widespread solidarity, the Chinese American community struggled to sustain its resistance.

Finally, the decision by the US Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), dealt a major legal setback to Geary Act resistance and undermined the credibility of the Six Companies. The decision validated the Geary Act and created an environment of fear within the Chinese American community. The inability to overturn the Geary Act by legal means diminished trust in the Six Companies’ capacity to protect the community's interests.

Photograph of a merchant from Chinese Business Partnership Case File for Quong Lee Company, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from the files of the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office). The immigration investigative case file indicates that the individual in this photo was certified as a business partner and a "merchant" who was “able to travel to and from the U.S. as a ‘Chinese subject of exempt class’ under the ‘Chinese Exclusion Acts’ (1882-1943).” The Quong Lee & Co. (a.k.a. Quong Lee, Quong Lee Sing) operated what business directories from 1875 to 1905 variously described as a “tailor,” “general merchandise,” “clothing,” and “dry goods” business continuously at 828 Dupont Street. By the time this merchant sat for his photo in 1896, the national boycott led by Chinese merchant organizations against the Geary Act of 1892 had collapsed, and studio portraits such as this became an essential pieces of evidence to support applications for the coveted merchant exemption from the extended Exclusion Act.

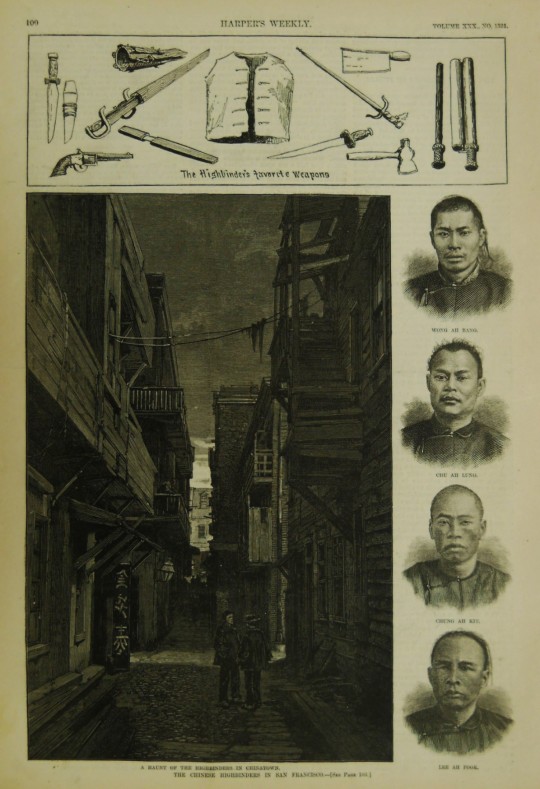

This heightened sense of vulnerability played into the hands of tongs, which, capitalized on the weakened merchant community. Amidst the faltering influence of the Six Companies, tongs emerged as influential entities that would come to dominate Chinatown’s socio-political structure and shape mainstream society’s perceptions of the Chinese community for the next three decades.

“High-binders Retreat” no date. Photograph by Goldsmith Brothers (from the Cooper Chow Collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). Tong members at ease in front of their fraternal order's headquarters.

Tongs, in contrast to the Six Companies' diplomatic approach, adopted a more assertive stance in responding to discrimination and persecution faced by the Chinese community. Their readiness to protect their members (which also included merchants), and defy external pressures resonated with many disillusioned residents.

“A Haunt of the Highbinders in Chinatown.” Harpers Weekly, February 13, 1886 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

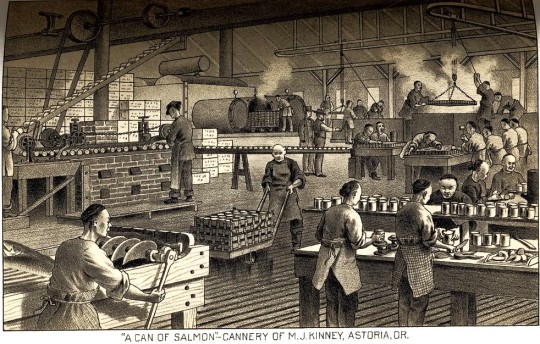

Moreover, the tongs during this period had begun to diversify their activities beyond traditional, illicitl sources of income such as prostitution, gambling, and drug distribution. Tongs began engaging in both legitimate businesses, including labor contracting for the Alaskan canneries. This diversification allowed them to accumulate resources, expanding their sphere of influence within Chinatown and beyond as alternative community governance structures, while still reserving often violent means to protect their interests.

Chinese salmon cannery works in Astoria, Oregon, c. mid-1880s. Drawing from West Shore, June 1887, from the Special Collections, University of Washington). The early 20th century would be marked by violent struggles between tongs such as the Suey Sing and Bing Kung for control over the labor contracting business for the canneries.

The ascendancy of tongs at the turn of the century coincided with the republican movement in China. Historian Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong, the original triad society, had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society’s newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

The tongs’ economic power and their active involvement in fundraising for the republican movement not only showcased their financial strength but also demonstrated their ability to wield influence as an overlapping and sometimes counter-force with the merchant elite. This dual role as (1) economic powerhouse within the local community, and (2) significant contributor to a revolutionary cause overseas underscored their influence. The growth of that influence came at the expense of the merchant elite in shaping both local and international affairs.

Merchants, however, would continue to exert influence through clan organizations, tongs, business associations, Nationalist Party of China chapters, and Chinese “consolidated benevolent associations” in San Francisco Chinatown and communities across North America through the exclusion era, war, and peace.

The meeting hall of the Chinese Six Companies, c. 1920 (by then incorporated as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco. Photographer unknown (from the Jese B. Cook collection of the Bancroft Library).

Chinatown's merchant community would face new challenges to their capacity as civic leaders when the political center of gravity across US Chinatowns would shift again in the last quarter of the 20th century.

[updated 2023-12-28]

#Chinatown merchants#Sing Man#Choy Chew#Chinese Merchants Exchange#Fung Tang#Lai Chun-chuen#Chy Lung & Co.#Yee Ah-Tye#Chinese Six Companies#Kai Suck#Ann Ting Gock#Lew Kan#Chee Kung Tong#Quong Lee & Co.

0 notes

Photo

“Chinese Mercantile House, Dupont St.” Photographer unknown (from the collections of the Society of California Pioneers or the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection of the San Francisco Library

Two Pioneer Chinese Mercantile Houses

The above photograph and the Houseworth stereoview, variously titled as the Chinese mercantile house or houses on Dupont Street claimed a copyright 1866, and, hence, our friends at OpenSFhistory.org have indicated 1866 as the year during which it was taken. However, the year in which the original photograph was taken can be more accurately determined by comparing the visible address number with the business directory listings of the time.

“394. Chinese Mercantile House, Dupont street.” Stereograph by Lawrence & Houseworth, Thomas Houseworth & Co., from the collection of the California State Library.

The stereograph clearly depicts two buildings housing the offices and warehouses of Hop Kee & C. and Hop Yik & Co. Both firms figured prominently in the early economic life of San Francisco’s Chinese community and beyond.

The Harris, Bogardus and Labatt and the Colville directories of 1856 show Hop Kee & Co. located at 171 Dupont St. The business address listings, therefore, coincide with the numerical address plaques affixed to the ground floor façade of the Hop Kee building seen in the center of the photo. Hop Kee would remain at this address at least through 1860 when (according to the Langley directory for the year commencing in September 1861), it began operating from 705 Dupont.

“South side of Sacramento Street. West of Kearny St.,” c. 1860’s. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

The visible business signage for the Hop Yik & Co. in the stereograph of Dupont presents even more of a mystery because the business directories of the time (particularly the 1860 listing for Hop Kee at 171 Dupont) do not show Hop Yik operating from a building next door to Hop Kee on this portion of Dupont Street (prior to both moving to the 700-block of the same street). In fact, photographic evidence places Hop Yik at its headquarters located at 705 Sacramento Street during the 1860’s as seen in the above photo.

A notice from the Daily Alta California of August 12, 1865, announcing the removal of Hop Yik & Co. to 707 Dupont Street.

Thanks to an ad placed by Hop Yik & Co. in the Daily Alta California in the summer of 1865, it appears that both companies reunited to operate next door to each other when Hop Yik moved to 707 Dupont Street. Unfortunately, the ad fails to recite the prior address of Hop Yik, and the directories are unreliable and inconclusive because they omit mention the Hop Yik company entirely.

Thus, one can only presume that Hop Yik & Co. had either (a) moved to Sacramento Street after sharing the 100-block of Dupont with Hop Kee & Co. (when the two companies were photographed as adjacent to each other), and prior to Hop Kee’s move in 1861 to the 700-block of Dupont; or (b) Hop Yik had remained on the 100-block of Dupont until Hop Yik’s move in 1865 to space again adjacent to Hop Kee.

What can be concluded confidently is that the photo was not taken in 1866. More likely, the Hop Kee and Hop Yik companies were photographed when they briefly occupied spaces on the 100-block of Dupont and adjacent to each other for a brief period prior to and during 1861 (until Hop Kee’s move that year).

“394. Chinese Mercantile Houses, Dupont Street, San Francisco.” Stereograph (on yellow card mounting) by Lawrence & Houseworth, Thomas Houseworth & Co.

Having addressed the rough and confusing tandem movement of both merchant establishments during the 1860’s, several other observations are worthwhile.

On the left edge of the frame, a vertical, Chinese medicine (herbalist) shop placard appears to read as follows: 廣同仁生熟藥材發客 (canto: “gwang tuhng yahn saang suhk yeuk choy faat haak;” mando: “Guǎng tóngrén shēng shú yàocái fā kè”). I use the word “appears” because the second-to-last character is smeared. However, fellow analyst, Wong Yuen-ming, points out that the ideogram “發” customarily precedes 客 in commercial advertising even to this day; it denotes literally “send off” or delivery of the prescription. The full line translates literally as “Guang tong ren's raw and cooked medicinal materials are sent to customers.” Further, Y.M. surmises that the characters ”廣同仁”or, literally, Guang[tong] colleagues, represents a homophone that may also be a pun or play on words for “廣東人,”or Cantonese people.

Many photographs of pre-1906 Chinese businesses convey information that has been lost to historical memory, and this stereoview represents on such example. First, and as the late community historian Thomas Chinn observed, Chinese businesses operated well beyond what would become the traditional, segregated borders of San Francisco Chinatown. Chinese businesses operating in the 100-block of Dupont would have been unheard of, especially after the city’s large anti-Chinese riot of 1877 when dozens of Chinese laundries operating outside the then-hardening borders of Chinatown were burned. Second, the movement of both the Hop Kee and Hop Yik companies to the 700-block of Dupont exemplified the general spread of Chinese business occupancy from its original focal point on Sacramento Street toward the north up Dupont Street.

From the September 10, 1855, issue of the Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California

The precise year during which the Hop Kee & Co. established itself in San Francisco remains unclear. However, Hop Kee had already attained by 1855 a position of prominence as a merchant house in San Francisco. Its stature was such that “Hop Kee & Cie” co-signed the open letter of September 10, 1855, in the Daily Alta California, decrying the negative shift in attitudes against, oppressive legislation, and often violent treatment of, the Chinese that had already occurred by the fall of 1855, particularly in California’s gold fields. The open letter read as follows:

To the American Citizens.

AMERICANS: We the undersigned, Chinese merchants, come before you to plead our cause and that of all our countrymen, residents of San Francisco, or diffused throughout California.

We ask for the moral and industrious of our race liberty to remain in this State, and to continue peaceably and without molestation in our various labors and pursuits.

We have no wish to recriminate -- nevertheless, there is no person in this State, or even in the entire world, who does not know with what lack of favor we have been treated in California. Neither injustice nor severity has been spared us. We came to this country expecting to meet with a liberal and hospitable reception, worthy in every particular the generous character which report has given to Americans.

Many among us have been attracted here by promises and the offer of a free passage, made for the purpose of inducing a larger emigration. And when, after leaving our country, we arrive here with our fortunes and our industry what do we encounter? Instead of the equality and protection which seemed to he promised by the laws of a great nation to those who seek a shelter under its flag, an asylum upon its territory, me find only inequality and oppression.

Frequently before the Courts of Justice, where our evidence is not even listened to -- where, if it obtain a hearing, by favor, but rarely is any account made of it. Inequally before public opinion -- which is so far, apparently, from considering us as men, that many of your countrymen feel no scruple in making our lives their sport, and in using us as the object of their most cruel amusement. Oppression by the law, which subjects us to exorbitant taxes imposed upon us exclusively oppression without the pale of the law, which refuses us its protection, and leaves us a prey to vexations and humilities, which it seems to invoke upon our heads by placing us in an exceptional position.

Believe us, we have exaggerated nothing in this picture; we have related the facts as they are and as you well know that they are. We do not speak with bitterness or rancor; we do not speak to repine over what has passed, nor over what exists, but to ameliorate our condition in the future.

We see well that you appear to desire our departure from a country to which we have been in a manner invited. But, in good faith, how can this be accomplished immediately, at any rate? Our number is great in California perhaps over 50,000. How, then, can such a multitude of persons (brought to California at a time' when the fever for emigration immeasurably enhanced the means of transport, and who have since successfully arrived here through a number of of years) -- how can they, at a given moment, provide themselves with the means of quitting this country in a body, in order to seek elsewhere some less inhospitable land?

We leave it to yourselves to say if this thing is possible. We ask you, however, what you would say if tomorrow, by the operation of iniquitous and vexatious lawn, all the Americans doing business in China should be compelled to leave the ports which are now opened to them under treaty arrangements? All your journals, the organs of public opinion, would demand the dispatch of an armed force powerful enough to obtain reparation for the wrongs which those Americans had suffered. Will you then do that to us which you would not allow us to do to you?

You reproach us with the name of idolators, you shame us for not practising the religion of Christ; but if we mistake not, Christ commanded his disciples to consider all men as brethren, to treat all men as brethren. Is it a faithful following of the Christian religion, that religion of love and meekness, to place under the ban of humanity an entire race of men, to treat then as an inferior species, as if unworthy of any pity? We, even we, would not this thing for one great philosopher, Confucius, whose teachings we respect and practice, has included humanity, charity and even politeness.

We are not ignorant that many among us are addicted to professions and modes of life which are degrading, and that therein is one cause of the reprobation which you pronounce upon us all -- But is this just? Should you render a whole race responsible for the reprehensible acts of a portion of it? Those whose conduct is m conflict with public morality, those who violate your laws, deserve punishment, and the same laws ought to furnish you with the means of attaining them. without recurrence to exceptional measured, unworthy of a free people, and involving the serious objection of crushing the innocent with the guilty, the good citizen with the malefactor.

No. Americans, we cannot believe that such an idea is harbored in your minds. You are too generous, too enlightened, not to revolt from an act so odious; not to perceive the impolitic of excluding a race of active industrious men, content with small recompense for their work, at the very time that California is in need of all the laborers that can be brought to bear in the development of her agricultural and other branches of industry. It is superfluous to mention the serious effect on your market which must inevitably be produced by the simultaneous departure of sixty thousand persons.

Americans! We appeal to our generosity, to your good sense; we trust that you will appreciate these observations, and that they may aid you in forming another opinion, less exaggerated than that you now entertain respecting us. We think that, after reading them, instead of considering us as detrimental or inimical, you will look upon us as useful laborers, desirous of contributing to the general wellbeing of the society of which we are members, and as such entitled to justice and good will.

[signatures]

Receipt issued in July 1858 to Chang Tsoo and Chaok Fan, the local representatives for the San Francisco Chinese merchants, for payment of surveying 20 Victoria town lots in 1858. Courtesy BC Archives

In 1858, the Hop Kee & Co.’s major real estate acquisition of 20 lots in Victoria, B.C., essentially established Canada’s oldest Chinatown – at the dawn of the Fraser River gold rush. Historian and professor Daniel Marshall recounts that “Kwong Lee & Company were working as the northern agents for Hop Kee & Company of San Francisco, and the archival trail provides a fascinating collection of documents (financial papers, receipts and so forth) that confirm this. More importantly, as we shall see, are the names of individuals noted on these documents that, in effect, link our 1858 Chinese gold seekers to one of the most prominent and highly regarded members of the early nineteenth-century Chinese Transpacific trade.”

For more details, see: https://theorca.ca/resident-pod/the-forgotten-context-of-canadas-oldest-chinatown-part-ii/

Among other documentary items, Marshall cites a Sacramento Daily Union article from June 24, 1858, which reported as follows:

“Sam Wo & Co., and Hop Kee & Co., the Chinese merchants, have purchased an entire square for Chinese purposes. No more lots are now sold by the Government; the rush on the land office was so great that it was thought proper to close it.”

In spite of the evident and growing hostility to the Chinese over the preceding two decades, Hop Kee appeared to prosper and maintain its position of prominence as one of the “leading Chinese mercantile houses of California” as described in newspaper accounts of the time. A typical account of a banquet held in honor of the then-Speaker of the House (and later the 17th Vice President of the United States), Schuyler Colfax during Colfax’s tour of the western territories in 1865 was recounted in the Daily Alta California of August 18, 1865, as follows:

The above story reports that Wong Cheong Ngan of the “Hop Yik Store” and Chang Hung of the “Hop Kee Store” represented their companies at a banquet held by the Chinese Six Companies at the Hang Heong Restaurant at 808 Clay Street on August 17, 1865. Colfax, along with author Samuel Bowles and Lieutenant Governor of Illinois William Bross, had set out across the western territories from Mississippi to the California coast to record their experiences. They compiled their observations in an 1869 book called Our New West. Numerous towns and streets in at least nine states were eventually named in Colfax’s honor.

Aside from starting the Chinese business community’s now 170 year-old practice of ingratiating itself with public officialdom, the historical record shows that the merchants of both the Hop Kee and Hop Yik companies also engaged in strategic philanthropy. Five years later, and as reported in the November 22, 1870, issue of the Daily Alta California, the Rev. Otis Gibson publicly thanked Chinatown’s merchants for its raising funds for furnishing the Chinese Mission Institute of the Methodist Episcopal Church on Washington Street.

Both the Hop Kee & Co. and Hop Yik & Co. joined other merchants at the $5 level (although not as generous as the Chy Lung & Co., profiled elsewhere in this blog) in supporting the establishment of the Mission home.

As the newspaper reported at the time, “[t]he Chinese, seeing the practical workings, have themselves commenced to take an active interest. A subscription was circulated among their merchants to raise funds for the purchase of the necessary seats for the school rooms. . .”

Thus, the merchant community had already understood the benefits from the pursuit of strategic philanthropy.

The earliest known depiction of the Chinese Mission Institute founded by the Rev. Otis Gibson.

Even as the Chinese were driven off of their settlements throughout rural California and the American West, Hop Kee & Co. continued to thrive. The firm (through what appeared to be a mis-identified representative), was mentioned among other prominent merchants in a first-person account by Brigadier-General James F. Rusling (ret.) of a banquet at the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco as described in his book, Across America: Or The Great West And The Pacific Coast, published in 1874.

Exterior view of the Occidental Hotel, San Francisco, c. 1865; from the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS CAL,38-SANFRA,12—1. The hotel opened in 1861 and was destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906.

General Rusling wrote about the banquet event as follows:

“We had seen a good deal of the Chinese generally, but on the evening of Dec. 31st were so fortunate as to meet most of their leading men together. The occasion was a grand banquet at the Occidental, given by the merchants of San Francisco, in honor of the sailing of the _Colorado_, the first steamer of the new monthly line to Hong-Kong. All the chief men of the city--merchants, lawyers, clergymen, politicians--were present, and among the rest some twenty or more Chinese merchants and bankers. The Governor of the State presided, and the military and civil dignitaries most eminent on the Coast were all there. The magnificent Dining-Room of the _Occidental_ was handsomely decorated with festoons and flowers, and tastefully draped with the flags of all nations--chief among which, of course, were our own Stars and Stripes, and the Yellow-Dragon of the Flowery Empire. A peculiar feature was an infinity of bird-cages all about the room, from which hundreds of canaries and mockingbirds discoursed exquisite music the livelong evening. . . .”

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

“The creature comforts disposed of, there were eloquent addresses by everybody, and among the rest one by Mr. Fung Tang, a young Chinese merchant, who made one of the briefest and most sensible of them all. It was in fair English, and vastly better than the average of post-prandial discourses. This was the only set speech by a Chinaman, but the rest conversed freely in tolerable English, and in deportment were certainly perfect Chesterfields of courtesy and propriety. They were mostly large, dignified, fine-looking men, and two of them -- Mr. Hop Kee, a leading tea-merchant, and Mr. Chy Lung, a noted silk-factor--had superb heads and faces, that would have attracted attention anywhere. They sat by themselves; but several San Franciscans of note shared their table, and everybody hob-nobbed with them, more or less, throughout the evening. These were the representatives of the great Chinese Emigration and Banking Companies, whose checks pass current on 'Change in San Francisco, for a hundred thousand dollars or more any day, and whose commercial integrity so far was unstained. . . .”

“Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796″ Stereograph by Carleton Watkins. The company’s co-founder, Chung Lock, was one of the first merchants to establish a business in San Francisco in 1850. His well-known company had branches in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Yokohama. As none of the principals in the company were named “Chy Lung” (and Chung had passed away in 1868), General Rusling’s account of the banquet described above from his book of 1874 probably identified a representative of the Chy Lung company, as well as one from Hop Kee.

By 1875, Hop Kee’s directory listing advertised the company as dealing in wholesale provisions of rice, tea, sugar, oil, etc., and operating a boot and shoe factory at 804 Sacramento, as well as selling dry goods from a store at 804 Washington. After 1879, Hop Kee’s business listing as a “merchandise, and boot and shoe manufs,” disclosed a business address of 806 Sacramento Street with “salesrooms” at 723-725 Clay and 712 Commercial Streets. By 1884, the Langley directory shows “Hop Kee & Co. (Lee Chew Fan and Loo Chuck Fan) wholesale boot and shoe manufacturers” as having moved to 615-617 Dupont St.

At no time did Hop Kee’s advertising mention the lucrative product line offered by its company facilities in Hong Kong.

Lai Yuen and Fook Lung 5-tael cans, c. 1890s, probably genuine. Kam Wah Chung Museum, Oregon

As researcher Chuimei Ho writes at https://www.cinarc.org/Opium.html#anchor_128, Hop Kee & Co.’s name, and the opium supplied from its processing facility in Hong Kong, figured prominently in the customs forfeiture case of Three Thousand Eight Hundred and Eighty Boxes of Opium v United States, decided in Circuit Court D, California, on September 20 1883. (see https://law.resource.org/pub/us/case/reporter/F/0023/0023.f.0367.pdf)

In that case, Chuimei writes that the claimant “Kennedy had ordered the opium, 4000 taels (2000 pounds) in all, from Choy Suey and Choy Lum, owners of Tai Hung & Co. at 1014 Dupont [Grant] Street in San Francisco. They in turn had purchased the opium, already refined, from firms named Hop Kee and Tuck Kee & Co., also in San Francisco. Until 1880, it was testified, Hop Kee had operated a “manufactory” of prepared (refined) opium in Newark, New Jersey. At Kennedy’s instructions, the Choys repackaged the Hop Kee/Tuck Kee opium to look like the Lai Yuen and Fook Long brands. Perhaps because this was not a crime in California, Choy Lum was quite open about what he had done. He used old 5-tael cans, soaking and rubbing off the labels and putting new ones on, packing each group of 200 cans into a larger tin with a new cover soldered on by a local tinsmith, Ah Hock.” [emphasis added]

Chuimei continues to recount that “almost all of the activities described above were legal, in American if not Hawaiian law, that the witnesses, Chinese and European, testified freely, and that the only person involved who was in legal trouble was Kennedy. And even he was in no danger of prison: the issue at hand was simply whether Customs officials could keep the opium or whether they would have to give it back” (about which the court ruled in favor the government).

Dissolution of Partnership of Hop Yik & Co.

The Hop Yik & Co. mercantile group underwent change in June 1868 when three of its partners bought out two others, as published in a notice of partnership dissolution printed in the Daily Alta California of July 13, 1868. The firm continued to do business, as indicated by a listing in the Langley directory of 1871. By the next year, however, the name of Hop Yik & Co. no longer appears in general or Chinese business listings.

As for the other Chinese mercantile house of photographic note, the Hop Kee & Co.’s San Francisco operation drops from view after 1884. Neither it or its former neighbor, Hop Yik, survived to the advent of the Chinese telephone exchange of the late 1890’s. Although research continues, one can only assume that both pioneering Chinese merchant firms had passed into San Francisco history before the end of the 19th century.

“394. Chinese Mercantile House, Dupont Street” from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection -- circa 1861.

#Chinese mercantile houses#Hop Kee & Co.#Hop Yik & Co. San Francisco Chinatown#Dupont Street#fung tang#Chy Lung & Co.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Untitled photo used for the c. 1865 stereograph “393. Chinese Market Places -- Sacramento Street” by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from the collection of the Society of California Pioneers).

Scenes from Where We Began: Sacramento Street -- 唐人街

According to the founding historians of the Chinese Historical Society of America, Thomas Chinn and Phil Choy, “[t]he early Chinese stores were mostly on Sacramento Street between Kearny and Dupont (now Grant Avenue) Streets. To this day, older Chinese still call Sacramento Street ‘Tong Yan Gai’ or “Chinese Street.” Beginning with the 1850’s San Francisco’s Chinatown began to take shape.

A view east down Sacramento Street toward the bay, c. 1852-1855. Photographer unknown (from a private collection). Signage for some of the earliest Chinese businesses in San Francisco can be seen in the left foreground. An advertisement for “Gray’s Coffin Warehouse” appears on the side of a building at left; its owner, Nathaniel Gray, operated a funeral home at 205 Sacramento Street in 1852, according to the Morgan city directory, and at Sacramento and Dupont, according to the Parker directory for 1852-1853.

A close-up of the Chinese business signage along Sacramento Street, c. 1852-1855. On the left side of the street, the vertical signage reads: 中和堂各省藥材 (lit. “Central Harmonious Hall medicinal materials from various provinces;” canto: “Jung Wo Tong gok sahn yeuk choy”). The signage across the street at right is another 堂 also selling 各省藥材 or medicines.

“Sacramento Street in May 1854.” Drawing attributed to German artist Charles Christian Nahl (1818-1878) from a private collection. In this view west up the incline of Sacramento Street, the artist’s ersatz Chinese-character signage for Chinatown’s earliest pioneer businesses mirrors the signage seen in the preceding photo of an easterly view the street and the coffin seller’s business on the north side of the street at right.

Untitled view of the Chinese markets on the south side of Sacramento Street, San Francisco, c. 1865. This photograph (from the collection of the Society of California Pioneers) served as the source for stereograph no. 393 produced by Lawrence & Houseworth.

“393. Chinese Market, Sacramento Street, San Francisco.” c. 1865. This photographic variant of the Chinese stores on the south side of Sacramento Street (from a private collection), was also numbered “393” and registered in 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth. The image depicts more the northern side of the street in the left background.

“Sac. St. SF Chinatown 1865″-- Photographer unknown (detail from the San Francisco Library Historical Photo Collection)

By 1850, Chinese businesses and residents had expanded from Sacramento Street and began occupying buildings on Dupont from Sacramento to Jackson Street and on Jackson Street from Kearny to Stockton.

“In San Francisco's Chinatown of the early 1850's: “. . . The majority of the houses were of Chinese importation, and were stores, stocked with hams, tea, dried fish, dried ducks, and other . . . Chinese eatables, besides copper pots and kettles, fans, shawls, chessmen, and all sort of curiosities. Suspended over the doors were brilliantly-colored boards, about the size and shape of a headboard over a grave, covered with Chinese characters, and with several yards of red ribbon streaming from them; while the streets were thronged with . . . Celestials, chattering vociferously as they rushed about from store to store, or standing in groups studying the Chinese bills posted up in the shop windows, which may have been play-bills —for there was a Chinese theatre — or perhaps advertisements informing the public . . .

“Sac. St. SF Chinatown 1865″-- The San Francisco Library Historical Photo Collection lacks any information about the photographer for this easterly view of the south side of early Chinatown’s Sacramento Street from Stockton Street. However, the photograph is the same image from which the Lawrence & Houseworth produced the stereograph “393. Chinese Market, Sacramento Street, San Francisco” (also from the San Francisco Library Historical Photo Collection).

“By the mid-1850's San Francisco's Chinatown had grown to be a bustling place with thirty-three general merchandise stores, fifteen apothecaries, five restaurants, five butchers, five barbers, three tailors, three boarding houses, three wood yards, two bakers, five herb doctors, two silversmiths, one wood engraver, one curio carver, and one broker for American merchants and a Chinese interpreter.” -- Thomas Chinn and Phil Choy

South side of Sacramento Street, probably below Dupont Street, c. 1860s. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

“South Side of Sacramento St. West of Kearny St. 1860s.” Photographer unknown (from the collections of the Bancroft Library and Martin Behrman Negative Collection of the GGNRA). By the time this photo was taken c. 1865, the pioneer mercantile house Hop Yik & Co. had moved into the building at 705 Sacramento Street (seen in the left of the photo), adjacent to the double-door building of the Broderick Engine Co. 1. Unfortunately, little is known about the Hop Yik business which may have moved from Sacramento street by the time of the publication of the San Francisco Directory of October 1868 (published by Henry G. Langley), which shows a “Hop Yike & Co. (Chinese) merchants” at 707 Dupont St. The business name had disappeared by the time of the publication of the Chinese Business Houses in San Francisco found in the Bishop & Co. directory of 1875.

“392. View among the Chinese on Sacramento Street, San Francisco” c. 1865. Stereograph by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from the Robert N. Dennis Collection of the New York Public Library).

The source photo for the Thomas Houseworth & Co. stereograph "392. View among the Chinese on Sacramento Street, San Francisco" (from the collection of the California Society of Pioneers).

“It should be noted that the segregated pattern which so marked Chinatown in the later years of the nineteenth century had not been established. For in that period a Chinese candle factory was established at Third and Brannan Streets. Rincon Point was host to a Chinese fishing village. The Ning Yung Company was located on Broadway Street, the Young Wo Company on the slopes of Telegraph Hill, while the Yan Wo Company was in Happy Valley (in the vicinity of the present . . . Palace Hotel.)”

-- From Chinn, Thomas W., Ed.; Lai, H. Mark and Choy, Phillip P., Assoc. Ed., A History of the Chinese California: A Syllabus, pp.10-11.

“Rue de Sacramento, a San Francisco.” c. 1868. Drawing by H. Clerget, based on a c.1865 photograph.

“Chinese Butcher Shop, Sacramento Street, San Francisco, California” was taken by John James Reilly, circa 1877, and printed as an albumen stereograph

For the historian, the name of Tung Foo Co. and its address number at “743” appear clearly on this photograph which depicts the exterior of a two-story Chinese butcher shop. Half a dozen men wearing long aprons stand in the main entrance. The commercial street on which it was located was printed on the border of the stereograph, a zoom-able image of which may be viewed on the OMCA Collections page of the Oakland Museum. The museum catalogs the photo as having been taken circa 1875. http://collections.museumca.org/?q=collection-item/2008973

“No. 115. Chinese Butcher Shop, Sacramento Street, San Francisco.” Photograph by J.J. Reilly (from the collection of the Oakland Museum of California).

By consulting contemporary business directories, we can better establish the year in which Mr. J.J. Reilly took his photograph. Based on a quick review, the Oakland Museum’s estimate of the year during which the photograph was taken is probably incorrect. An examination of both the San Francisco Directory of October, 1868 (published by Henry G. Langley) and The New City Annual Directory of San Francisco as published by the D.M. Bishop & Co. in 1875 (the latter’s separate section on “Chinese Business Houses” located in a separate section at the back of the main directory), disclose that the butchers of Tung Foo & Co. operated at the address of 729 Sacramento Street.

Operating a business on Chinatown’s main street, 唐人街 (canto: “tohng yahn gaai”), i.e., Sacramento Street, must have remained desirable to the proprietors of Tung Foo. The publication of the “Annual Directory of San Francisco” by the D.M. Bishop Co. in 1877, shows in its listing for the “Tung Foo Co., butchers and provisions, 743 Sacramento” that it had moved to 743 Sacramento Street (as shown at page 1484).

A comparison with the San Francisco Board of Supervisors special committee map of July 1885 shows that a decade later, the city survey showed a “general merchandise” establishment occupying the same address. In all likelihood, the business was probably the Tung Foo Co., as the last 19th century Langley Directory of 1896 containing a section for Chinese businesses showed the same company operating on Sacramento Street.

Thus, the historical record supports the conclusion that the hardworking gentlemen appearing in the photograph remained on Chinatown’s first main street for at least four decades preceding the great fire that would destroy the entire neighborhood.

Elevated view of Chy Lung & Co. at 640 Sacramento St., taken for Thomas Houseworth & Co., circa 1865. (From the Marilyn Blaisdell collection)

No discussion would be complete without mentioning the Chy Lung & Co., which was located for decades at 640 Sacramento Street. The Langley directory in 1868 listed the business as a purveyor of “(Chinese) toys and fancy goods.”

History prof. Yong Chen (UC Irvine) in a monograph for the Western Historical Quarterly in 1997, wrote about Chung Lock, its legendary proprietor, as follows:

"In a big funeral ceremony held late in August 1868, Chinese San Francisco buried one of its founding fathers, Chung Lock (who was usually styled Chy Lung). As one of the first Chinese immigrants to cross the Pacific Ocean to join the Gold Rush, Chung came to America in 1850 at the age of 35. Chung and his fellow pioneers helped transform the economic and social landscape of California, where they soon became a leading minority group and a major labor [contractor]. Most Chinese immigrants were laborers, and Chung was among the fortunate few who were able to accumulate considerable wealth in an unfamiliar and increasingly hostile environment. “By 1868, when he died of dropsy, this husky man had become a successful Chinese merchant as the co-owner of the firm "Chy Lung and Co.,” which three branches in China [Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong] and one in [Yokohama] Japan. In a lengthy report about his death, the Alta California [September 1868, 2] called him a “universally respected and esteemed … gentleman,” praising him for his generous philanthropy among both whites [the Sanitary Relief Fund during the Civil War and the “great Sacramento flood of 1861”] and Chinese and his ‘business sagacity.’ Undoubtedly, his business acumen was attributable to the good education he had received and to the entrepreneurial spirit he had acquired in his native Nanhai County in the Pearl River Delta region in east Guangdong Province. “Chung Lock [mando: “Chen Le”] reportedly founded the business with Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu.”

Chung Lock’s business associates would carry on the business to at least 1902, according its listing in the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902. As indicated by the 1903 telephone book, however, contains no listing, and the pioneering store appears to have closed its business prior to the 1906 earthquake.

Drawing of Sacramento Street, circa 1878

The view east down Sacramento Street and its intersection with Waverly Place, angled toward the north side of the street with its south side in shadows. Photograph by A.J. McDonald, no date (from a private collection).

“Chinese Quarters. San Francisco, Cal., no date. Photograph by A.J. McDonald reprinted on a postcard (from a private collection).

According to local historian, Art Siegel, A.J. McDonald operated in San Francisco between 1887 and 1895. McDonald’s photo of an easterly view down Sacramento Street is notable for its lack of cable car tracks and the absence of the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Building’s tower in the background. The absence of such landmarks provides clues about when the photo was taken –pre-November 1891. Cable car historians, Robert Callwell and Walter E. Rice, wrote about the Sacramento Street line as follows:

“The Ferries & Cliff House Railway purchased Hallidie's Clay Street line in 1888 to gain access to the Ferry Building - at the time, the most important public transportation terminal on the West Coast. That September, the company began service on a line between the Ferry Building and Presidio Avenue, using Sacramento and Clay Streets between the Ferry Building and the car barn area, and the Washington-Jackson line between there and Presidio Avenue, with outbound cars operating on Powell and inbound cars operating on Stockton between the two sections of the line. In November 1891, the company opened its fourth line, the Sacramento-Clay line. That line operated on Sacramento and Clay Streets between the Ferry Building and Larkin Street, and on Sacramento between Larkin and a terminal at Walnut Street, just west of Presidio Avenue.”

-- Callwell, R. & Rice, W.E., Of Cables and Grips: The Cable Cars of San Francisco (2d Edition, 2005, Library of Congress ISBN-978-0-9726162-2-5)

“1292A” circa 1893. Photographer unknown from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection. This photo looks northeast on Sacramento Street and its intersection with Waverly Place in the foreground. Cable car tracks, buggies, and a horse drawn delivery wagon coming up hill can be seen. The tower of the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Building (opened in 1893) is in the distance.

“267 Chinese Grocery” c. 1892-1895. Photograph by R.J. Waters (from a private collection. Based on the incline of the sidewalk and the address number, the photo probably depicts the grocery store located at 821 Sacramento in San Francisco Chinatown. According to the Horn Hom & Co. calendar and directory of 1892, the store was operated by the Yue Kee company (裕記; canto: “Yew Gay”). By 1894 -1895, the Langley directories listed a grocer named “Hong Ian & Co., 821 Sacramento” at the location. Waters’ photo served as the source for several postcard reproductions.

“1. Chinese Merchandise Store.” Postcard based on a photograph by R.J. Waters (from the collection of Wong Yuen-Ming).