#Chinese Merchants Exchange

Text

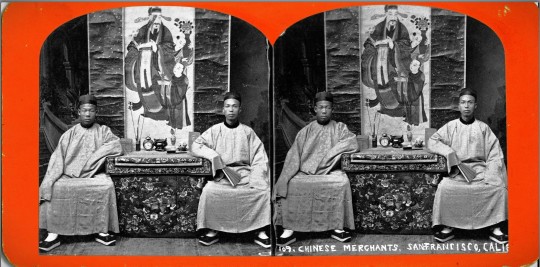

“109. Chinese Merchants, San Francisco, Calif.” c. 1890 – 1899? Stereograph by Nesemann Woods Gallery, Marysville CA (from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection of the University of British Columbia Library).

Merchants of Old Chinatown

In the late 1840s and the 1850s, Chinese merchants and traders made their initial foray into California. By February 1849, the number of Chinese had increased to 54 and by January 1850, historians would count 787 men and two women in San Francisco. In December 1849, the Alta California newspaper reported that 300 Chinese convened a meeting at the Canton Restaurant on Jackson Street for the purpose of organizing the “Chinese residents of San Francisco” and engaging the services of lawyer Selim E. Woodsworth to “act in the capacity and adviser for them.”

In his book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, historian John Tchen wrote about the vanguard of old San Francisco Chinatown’s merchant elite as follows:

“These pioneers hailed primarily from the Sanyi (Saam Yap) or Three Districts [三邑], as well as the Zhongshan area in the immediate vicinity of Canton. It's important to note that Nanhai (Namhoi) and Panyu (Punyu) stood out as the most prosperous districts within Guangdong Province. Their economic pursuits ran the gamut from cultivating fertile agricultural lands, breeding silkworms and fish, to crafting silk textiles, producing ceramics for both domestic and international markets, and engaging in various other commercial endeavors.

“What set apart the merchants and artisans from Sanyi and Zhongshan was their mastery of a more refined city dialect compared to their Siyi (Sei Yap) counterparts, who mainly consisted of poorer, rural communities. Remarkably, over 80 percent of Chinese immigrants in North America originated from the Siyi [四邑] region. A noteworthy portion of these Sanyi merchants belonged to the emerging class of compradores, individuals who facilitated business transactions on behalf of Western trading companies. These California-based Sanyi merchants thus brought prior experience in dealings with Western entrepreneurs, and California was seen as a promising arena to expand these lucrative connections.”

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May of 1869, the more sophisticated and adventurous members of San Francisco’s pioneer Chinese merchant community would begin exploring other cities in the United States in search of opportunity.

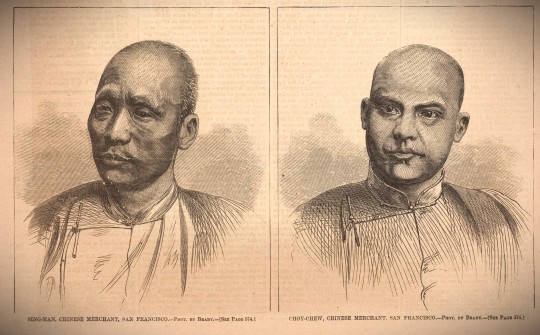

“Sing-Man, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco” and “Choy-Chew, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco,” Harper’s Weekly, September 4, 1869, wood engraving on paper. Artist unknown, artist after a photograph by Mathew Brady, 1869 (from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).

For example, in the Harper’s Weekly article (Sept 4, 1869, page 574), the reporter identified merchant Choy Chew as a San Franciscan and a talented linguist of sufficient intellect and stature to be invited to give a speech at a European-American banquet. He reportedly visited Chicago with a fellow merchant, Sing Man, before traveling to New York where the pair were regarded as “representatives of Chinese industry and commerce.”

At the banquet in Chicago, Choy Chew delivered the following remarks:

”Eleven years ago I came from my home to seek my fortune in your great Republic. I landed on the golden shore of California, utterly ignorant of your language, unknown to any of your people, a stranger to your customs and laws, and in the minds of some an intruder — one of that race whose presence is deemed a positive injury to the public prosperity. But gentlemen, I found both kindness and justice. I found that above the prejudice that had been formed against us, that the hand of friendship was extended to the people of every nation, and that even Chinamen must live, be happy, successful and respected in ‘free America.’ I gathered knowledge in your public schools; I learned to speak as you do; and, gentlemen, I rejoice that it is so; that I have been able to cross this vast continent without the aid of an interpreter; that here in the heart of the United States I can speak to you in your own familiar speech, and tell you how much, how very much, I appreciate your hospitality; how grateful I feel for the privileges and advantages I have enjoyed in your glorious country; and how earnestly I hope that your example of enterprise, energy, vitality, and national generosity may be seen and understood, as I see and understand it, by our Government …

”We trust our visit, gentlemen, may be productive of good results to all of us; that the two great countries, East and West, China and America, may be found forever together in friendship, and that a Chinaman in America, or an American in China, may find like protection and like consideration in their search for happiness and wealth.“

-- from the Scientific American, new series, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 131 (August 28, 1869)

The founding in 1888 of the Merchants’ Exchange in old San Francisco Chinatown represented the logical culmination of several decades of robust business operations by the pioneer Chinese merchants in the city and beyond.

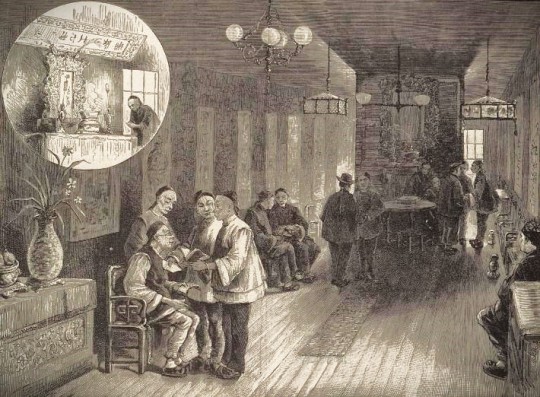

“Chinese Merchants’ Exchange, San Francisco.” Lithograph from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 26, March 18, 1882 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In his book, A Guide Book to San Francisco (published by The Bancroft Company in 1888), John S. Hittell described the Chinese Merchants Exchange as follows:

“At 739 Sacramento Street are the new rooms of the Chinese Merchants' Exchange. They are fitted up in the ordinary Chinese style, and though presenting no special attraction to the visitor, the business transacted there is of considerable importance. A Chinese merchant, contractor, or speculator never starts on any enterprise alone. He always has at least one partner, and in most cases several. He makes no secret of his transactions, but converses about them at the exchange, and often goes there in search of capital when his own means are insufficient. He sometimes applies to that institution to find him a capable man to manage a new business which he is about to start. If, as often happens, one be selected who is in debt to other members, they make arrangements which will not interfere with the new enterprise; and the debtor is not unfrequently released from his obligations.”

Fung Tang

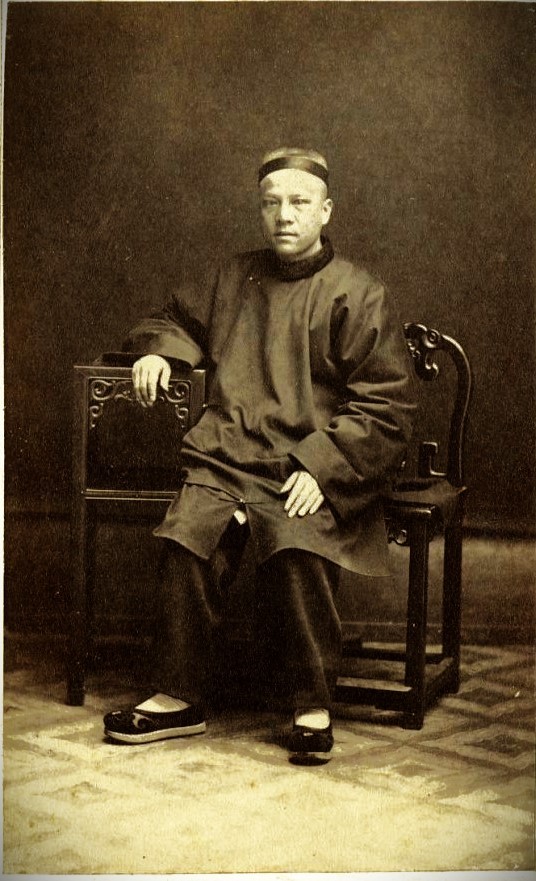

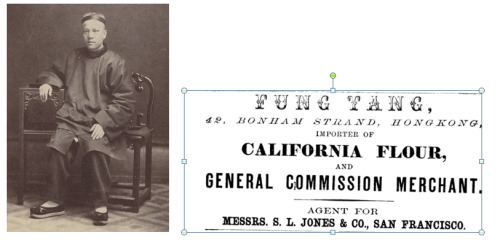

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

The address of the Merchants’ Exchange at 739 Sacramento Street was hardly surprising, as it shared the same building which had housed the mercantile house of a legendary merchant, Fung Tang. Historian York Lo, in his article for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, described Fung as “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the pioneer Chinatown photographer, Kai Suck. A professional studio portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. In fact, Fung appears to have deployed the same portrait now reposing in the collection of the California Historical Society as part of his commercial advertising in Hong Kong.

An advertisement for Fung Tang’s flour import business in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service, including his election to the board of directors of the Tung Wah clinic (the original predecessor organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encouraged to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

Tchen asserts that the influx of British and other Western imperialist powers into China’s major treaty ports transformed the status of merchants engaged with Western trading companies. Rather than operating on the margins of Qing-era society, the merchants gained unprecedented prestige and influence. Beyond China's borders, they experienced far more freedom to engage in trade and amass substantial profits without the worry of state-imposed restrictions. They rapidly acquired the necessary language skills and business acumen to navigate their newfound opportunities.

San Francisco’s early Chinese merchants swiftly grasped the English language and American business practices, excelling in American-style transactions, and developing strategies for fostering positive relations with the general San Francisco populace. The local press affectionately labeled them "China Boys." They made conscious efforts to participate in the celebrations of significant American holidays, further endearing themselves to the San Francisco community.

This approach significantly bolstered their rapport with the local population, as evidenced by the California Courier's glowing praise: “We have never seen a finer-looking body of men collected together in San Francisco. In fact, this portion of our population is a pattern for sobriety, order, and obedience to laws, not only to other foreign residents, but to Americans themselves," declared Cornelius B. S. Gibbs, a marine-insurance adjuster, in 1877. Gibbs emphasized the high esteem in which Chinese merchants were held among white business circles. “As men of business, I consider that the Chinese merchants are fully equal to our merchants. As men of integrity, I have never met a more honorable, high-minded, correct, and truthful set of men than the Chinese merchants of our city.”

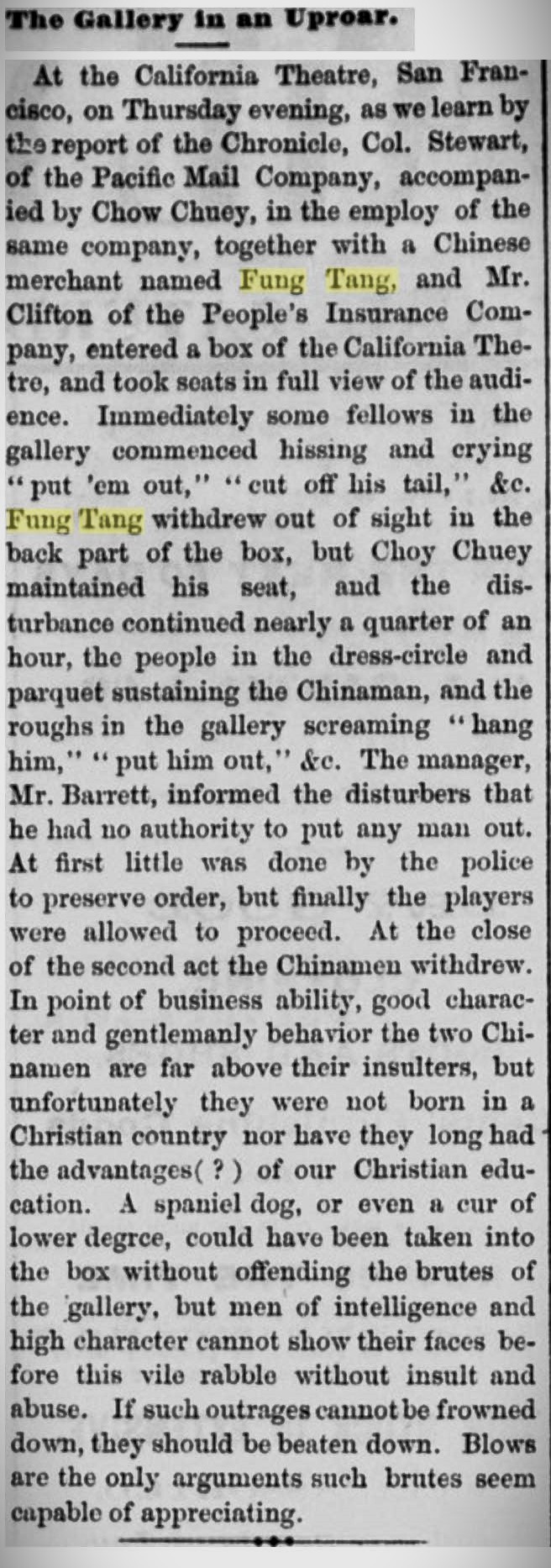

Attempts to participate in mainstream society, however, were not always welcomed by lower-class elements of white society as evident in this news account about Fung Tang’s appearance in San Francisco’s California Theatre in September 1869:

Clipping from the San Jose Mercury News, September 18, 1869 (vol. I no. 42)

Fung Tang’s transpacific success in San Francisco was hardly unique among the ranks of Chinatown’s early merchant class. He exemplified the business acumen of his fellow pioneering entrepreneurs and their establishment of transpacific trading posts in strategic locations.

Lai Chun-chuen and Chy Lung Co.

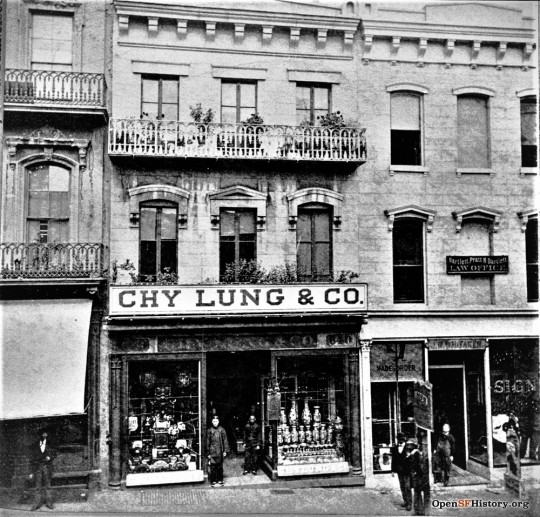

The story of the pioneer business of Chy Lung & Co. predates the history of San Francisco Chinatown itself, and its establishment spurred the rise of Chinatown’s first commercial strip, Sacramento Street (唐人街; canto: “Tohng Yahn Gaai”) or “Chinese Street.”

An enlargement of the stereograph taken by Carleton Watkins for the Thomas Houseworth & Co., and “[e]ntered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the Northern District of California.”

“Among the early Chinese settlers were merchants like Lai Chu[sic]-chuen,” the late historian Judy Yung wrote in her pictorial book, San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America). “Upon arrival in 1850, he opened Chinatown’s first Bazaar at 640 Sacramento Street, importing teas, opium, silk, lacquered goods, and Chinese groceries.”

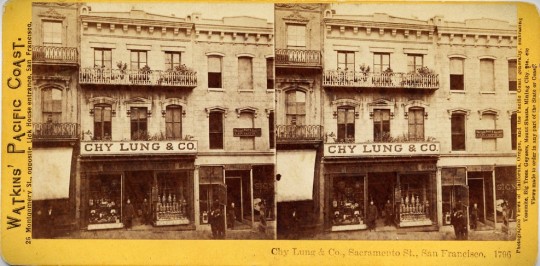

"Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796" c. 1866. Photograph by Carleton Watkins for his Watkins' Pacific Coast stereograph series (from a private collection).

Chy Lung’s founder, Lai Chun-chuen (a.k.a. Chung Lock), came to San Francisco in 1850 from Nam Hoi county. According to UC professor Yong Chen, the business founded by Lai and, his partners Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu, appear in the earliest business directories for San Francisco. A “Chyling, china mer, 188 Washington” appears in the Parker directory for 1852-1853. The Colville’s directory of 1856 lists a “Chy Lung (Chinese) mcht, Canton Silk and Shawl Store, 166 Wash’n,” and the business would remain on Washington Street (moving to 612 Washington St. by 1858) until 1863 when it relocated to 642 Sacramento Street. By 1865, the Chy Lung & Co. had either expanded or taken over the address of 640 Sacramento Street.

Portion of the stereograph “No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co.,” c. 1866. Published by Lawrence & Houseworth (from in the collections of the Society of California Pioneers, Wells Fargo Corporate Archives, and the Library of Congress).

“He imported Chinese prefabricated houses and cargoes of Chinese goods, teas, silk, lacquer and Porcelain wears, and even opium,” historian Phil Choy wrote. “The drug that made American merchants millionaires in the China trade now found its way to California for both the Chinese and American markets Chy Lung was one of only two Chinese businesses at the time that advertised in an American newspaper, the Daily Alta California.”

“No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento Street.” c. 1866. Published by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from in the collection of the New York Public Library).

Lai Chun-chuen is remembered not only for his business acumen but also as the principal author of the objections to the anti-Chinese movement in California and plea for civil rights as published in the pamphlet, Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco, upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections (San Francisco: Whitton, Towne, 1855).

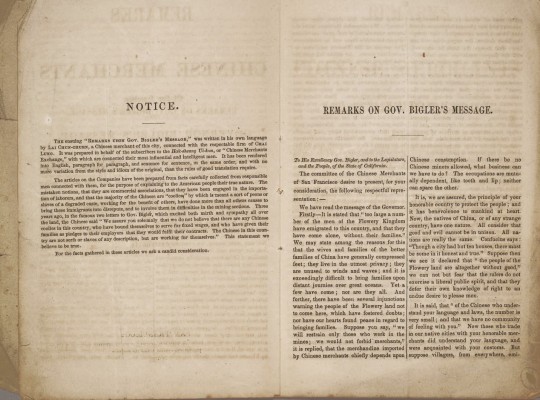

The preface to Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections of 1855 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The second line of the first paragraph identifies Lai Chun-chuen as “a Chinese merchant of this city, connected with the respectable firm of CHAI LUNG.”

Chy Lung & Co. continued to play a leading role in the Chinese merchants exchange until Lai Chun-chuen’s death on August 30, 1868. The business remained a fixture of the Chinatown business community for the rest of the 19th century, and it adopted the new communications technology of the telephone, as shown by the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902.

The listing for Chy Lung & Co. as it appeared in the Wells Fargo directories of Chinese business for 1878 and 1882.

The Chy Lung & Co. business, and others established by Chinatown's merchants, soon comprised a source of both tangible and symbolic power within the rapidly growing Chinese community in the American West. As the Chinese immigrant population swelled, businesses catering to their specific needs diversified and expanded. A hierarchical structure emerged, influenced by both economic factors and the district of origin. The wealthier Sanyi individuals typically presided over larger, commercially successful enterprises, including import-export firms. Those from the Nanhai District dominated the men's clothing and tailoring sector, as well as butcher shops. The neighboring Shunde District populace exercised control over overalls and workers' clothing factories.

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

Meanwhile, Chinese hailing from the Zhongshan District, which represented the second-largest Chinese population in California, were prominent in the fish and fruit orchard businesses, as well as in the production of women's garments, shirts, and underwear.

"Quan Quick Wah"

“Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). A descendant of the large, confident man shown in traditional robes identifies him as San Francisco merchant “Quan Quick Wah.” Based on other photographs of this Chinatown location, the pair appears to be walking on the west side of Waverly Place toward its intersection with Clay Street. In his book about Genthe’s Chinatown photographs, historian Jack Tchen wrote about this imposing figure followed by a bodyguard as follows: “The powerfully built man dressed in traditional silk robes has been described as a tong leader. Whether he was a tong leader, a wealthy merchant, or both, his dress and carriage convey a strong presence. Tong leaders came to rival the power of wealthy merchants. The man following the merchant or tong leader is said to have been his bodyguard, protecting him from the attack of a rival tong. In the photograph the two are passing under ornate cloth lanterns that indicate a pawnshop business.”

"Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). This full photograph in the Library of Congress shows that Genthe’s image fortunately included a portion of the sign for the entrance to a basement restaurant. The signage (which appears in other photographs of this area), indicates that the merchant and bodyguard were photographed walking on the west side of Waverly Place (at about no. 23 and 25 Waverly) and toward the southwest corner of its intersection with Clay Street. Tchen’s guess that the background store frontage was a pawnshop is probably correct, as the “Qung Hing Art Co.” pawnshop occupied space at 25 Waverly during the 1890s. The headquarters of the merchant-controlled, Ning Yung district association was located at 23 Waverly.

Yee Ah-Tye

In old Chinatown, merchants’ personal use of bodyguards or alliances with fighting tongs were common. The organization and fragmentation of district and clan associations, along with sharp business competition, often placed lives, as well as livelihoods, at risk. For example, the Kong Chow association traced its origin to about 1853, when the influential community leader, Yee Ahtye (a.k.a. “George Athei”) persuaded members of his Yee clan of Sunning, which had remained in the Sze Yup Co. (after a number of clans split off to organize today’s dominant Ning Yung Association), to finally secede. The action by the Yee clan was joined by clans from Hoiping and Enping counties after a dispute over the presidency of the Sze Yup Co. in 1862. The resulting new association, the Hop Wo, soon challenged the merchant Ah-Tye for the custody of a piece of land on which Ah-Tye had allowed the Sze Yup Association to build a headquarters building. Yee eventually deeded the land to a new Kong Chow Association, which his fellow Sunwui merchants founded in 1866. The dispute over this property raised to such a level that Yee and his associates were compelled to organize a secret society, the Suey Sing Tong, to protect the asset and enforce his decision.

Portrait of Yee Ah-Tye (courtesy of the Chinese Six Companies). Yee was an elite merchant of Chinatown and was considered a co-founder of the Suey Sing Tong.

Born around 1829 in Guangdong province, Yee Ah-Tye had arrived in San Francisco just before the gold rush at around 20 years old. In spite of his humble beginnings, Yee had learned English in Hong Kong and swiftly ascended to a position of authority within the influential Sze Yup [pinyin: "Siyi"] Association. The Sze Yup Association, along with similar Chinese district associations, played a crucial role in assisting newly arrived Chinese immigrants during the 19th century. The organizations provided accommodation and job opportunities.

Aside from his many business accomplishments, Yee famously cross paths with the legendary, San Francisco madam Ah Toy. The conflict arose when Ah Toy accused Yee of demanding a tax from her prostitutes on Dupont Street. Despite her origins in China, Ah Toy had by then lived in America for three years and become familiar with its legal system. She boldly threatened to take legal action against him, a move she would not have dared to undertake in China.

The August 1852 report in the Daily Alta California newspaper highlighted Ah Toy's shrewdness, emphasizing her knowledge of living in America and her ability to navigate the legal system. She resided close to the police station, fully aware of where to seek protection, having faced legal proceedings herself numerous times. The reporter gleefully suggested that Yee use caution about overstepping his authority, warning that he might lose his dignity and end up in custody.

A year later, Yee faced legal trouble himself, being arrested for assault and grand larceny. The San Francisco Herald alleged Yee “inflicted severe corporeal punishment upon many of his more humble countrymen … cutting off their ears, flogging them and keeping them chained for hours together.”

After moving to Sacramento in 1854, Yee also relocated his business activities in 1860 to La Porte, California, where hydraulic and drift mining operations for gold occurred. Yee acquired a partnership in a store called Hop Sing & Company which supplied merchandise and Chinese contract laborers. By 1866, it was the richest Chinese store in that town, with a value of $1,500 (about $36,000 in 2005 dollars).

According to one of his descendants, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, the pioneer Yee Ah Tye reportedly lived thirty-four years in La Porte as a successful merchant, running the Hop Sing and Company store and representing the Chinese community in the area. He had three wives and four children, three of whom were girls. Unlike most other Chinese fathers at the time, he invested in the education of his daughters – he even bought a piano for his youngest daughter, Bessie, who became an accomplished pianist. As a leader in the Hop Sing Association, he founded a small hospital to serve the elderly Chinese men of La Porte.

“The temple ruins at San Francisco's Lincoln Municipal Park Golf Course was once part of the Lone Mountain Cemetery, a gift of Ah Tye,” Lani Ah Tye Farkas wrote in 2000. “Other glimpses of his life in America can be seen in deeds, mining claims, tax assessments, newspaper articles, and land that he once owned. Yee Ah Tye's legacy, however, is in his descendants. Many Chinese with common last names like Chan, Lee, and Wong may have no relationship with one another. However, the descendants of Yee Ah Tye have borne his unique last name through six generations, in the words of the Yee family genealogy, ‘spreading like melon vines, increasing continuously’” Yee died in 1896. (see: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/pc289j76z)

Contract Labor

At the lower end of the business hierarchy, the Siyi or Four District residents comprised the largest and least affluent group of Chinese immigrants. They typically occupied occupations such as laundries, small retail shops, and restaurants and the bulk of the laborers in the contract labor system.

In the period preceding the Civil War, there was a concerted effort by certain individuals to introduce contract laborers into the United States. A letter penned by C. V. Gillespie to Thomas Larkin on March 6, 1848, sheds light on this initiative. Gillespie expressed a keen interest in the idea of bringing Chinese emigrants to the country, suggesting that a variety of skilled workers and laborers could be sourced:

"One of my favorite subjects or projects is to introduce Chinese emigrants into this country,… Any number of mechanics, agriculturists and servants can be obtained. They would be willing to sell their services for a certain period to pay their passage across the Pacific…."

The practice of importing contract laborers to the United States began in the late 1840s and continued through the 1850s. However, enforcing labor contracts proved to be a challenging endeavor on American soil. A case in point involved an Englishman who, upon bringing fifteen Chinese laborers to the country bound by a two-year contract, found that they immediately reneged on their agreement upon arrival. Authorities, at the time, were reluctant to intervene in such disputes.

In 1852, Senator George B. Tingley introduced a bill in the California State legislature aimed at legalizing and facilitating the enforcement of contracts allowing Chinese laborers to sell their services to employers for periods of up to ten years at fixed wages. This proposal, however, faced significant public backlash and was ultimately defeated after a heated debate. The subsequent year saw members of Chinese companies admitting that they had initially imported workers during the early years of the Gold Rush. Yet, due to unprofitability and difficulties in enforcing labor contracts, they abandoned this practice.

“San Francisco Chinese Merchant” no date. Photographer unknown, possibly by Ann Ting Gock (from a private collection). This rare and unusual image suggests that the individual might not have been a mere merchant at all, but a member of the Chinese consular staff. He is seen wearing his 清代官帽 (canto: "ching dai gwun moe") or official's headwear. The Qing official headwear or Qingdai guanmao (Chinese: 清代官帽; pinyin: qīngdài guānmào; lit. 'Qing dynasty official hat'), also referred to as the “Mandarin hat” in English, is a generic term which refers to the types of guanmao (Chinese: 官帽; pinyin: guānmào; lit. 'official hat'), a headgear, worn by the officials of the Qing dynasty in China. The merchant is attired in a "changshan" or "changpao" or long robe. The robe worn in the photo was derived from the Qing dynasty-period "qizhuang" (the traditional dress of the Manchu people). Changshan were, and are, traditionally worn for formal pictures, weddings, and other formal Chinese events.

Credit-ticket System

Beyond the initial years, it became widely acknowledged that Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States voluntarily, free from any servile contracts or duress. Many emigrants either financed their own passage or received assistance from relatives and friends already residing in California. The prevailing method for the majority of Chinese immigrants during the 19th century was the credit-ticket system. Under this system, an emigrant would receive financial support for their passage in a Chinese port. Upon reaching their destination, the emigrant was expected to repay this debt using their future earnings. It is important to note that this system differed from the contract labor arrangement, where laborers were bound to serve for a specified duration.

The precise origins of the credit-ticket system remain uncertain. However, merchant brokers in Hong Kong were established to provide advanced passage funds, approximately forty dollars, to the emigrants. Corresponding entities in the United States were responsible for collecting these debts and aiding the newly arrived immigrants in finding employment.

Two merchants with pipes. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The stores and offices that the merchants of Chinatown had opened starting in the mid-19th century became the basis of real and symbolic power in the growing regional community of Chinese living in the American West. That power, including the ability to mobilize for social change within the narrow role afforded Chinese in the society, manifested itself in the family and district associations headed by local merchants.

“The merchant class has traditionally been the one sector of Chinese society able to foster unity and bring about social change,” wrote historian Thomas W. Chinn about the role of the merchant class in San Francisco Chinatown (and beyond). “The merchant-directors of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association must be well-established businessmen in the local community as well as outstanding members of their own family associations. They have already played a leading role in their own social circles before becoming merchant-directors, and they enjoy a great deal of respect. . . Thus the friendly corner grocer may simultaneously be the president of his family association and his district association as well as a merchant-director.”

Lew Kan

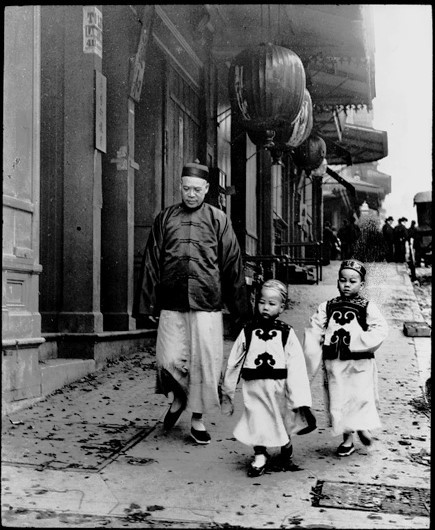

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.” The photograph appears to have found the trio walking down the south side of Sacramento Street below Dupont Street.

By the time photographer Arnold Genthe had photographed merchant Lew Kan and his two sons on Sacramento Street (as well as two other earlier photos of their four sisters in Portsmouth Square), Lew had already attained legendary status as one of Chinatown’s leading merchants. Born in 1851, Lew entered the US in 1866.

Author Roland Hui (in his biography of pioneer Chinese American industrialist Lew Hing), wrote about Lew Kan and his dry goods business called Lun Sing & Co. at 706 Sacramento Street as follows:

“He started Lun Sing, one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, around 1867, a year after he immigrated to the U.S. In 1896, the business gained notoriety by harboring a young Chinese revolutionary named Sun Yat-sen during his first visit to the continental United States. Sun advocated overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing a Chinese republic. His ideas were too radical for the politically uninitiated Chinese community. Kang Youwei, the architect of the ill-fated “Hundred Day Reform” in China in 1898, favored establishing a constitutional monarchy around Emperor Guangxu. Forced into exile after the power-hungry Empress Dowager crushed his reform, Kang launched the Chinese Empire Reform Association, also known as Baohuanghui (Save the Emperor Society), the following year in Victoria, Canada. Baohuanghui quickly gained widespread support among overseas Chinese since the idea of having an emperor at the top of the social order who ruled with the Mandate of Heaven had been ingrained in the Chinese psyche for thousands of years. The San Francisco Baohuanghui chapter was founded in 1899 at 146 Waverly Place. Lew Kan supported Kang’s political agenda despite having met Sun several years earlier, and in 1901 became the president of the San Francisco chapter of Baohuanghui. Many scholars observed that Baohuanghui was the first organization that evoked the patriotic sentiments of overseas Chinese. And when Liang Qichao, Kang's most famous student, stopped over in San Francisco during his 1903 America tour, thousands of Chinese flocked to listen to his speeches. As the man who organized these community-wide activities, Lew Kan's stature and influence in San Francisco Chinatown must have been substantial. In addition, he was one of the wealthiest Chinese merchants, reportedly owning several general merchandise stores with an estimated net worth of $2 million. That was an astronomical sum in those days. In addition, he was a director of the Kong Chow Company, a district association representing Xinhui."

Decline of Merchant Influence

The organizational expression of Chinatown’s merchant elite, the Chinese Six Companies, wielded considerable authority within San Francisco and beyond. The Six Companies and its constituent district associations comprised the quasi-government of Chinese America, offering social services, mediating disputes, and representing the community's interests to external forces. With the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882, their grip on power began to weaken.

Portrait of a merchant with fan and scroll. No date, photograph possibly by Shew’s studio (based on the detail of the end-table), from the collection of the Stanford Libraries.

The decline of the Six Companies’ influence can be attributed to various reasons. One significant factor was their inability to adapt swiftly to the evolving socio-economic landscape within Chinatown. As the community faced new challenges, including the punitive extension of Chinese exclusion with the Geary Act of 1892, the Six Companies struggled to effectively navigate these changes, leading to a loss of faith among the populace in their ability to address emerging issues.

The Geary Act of 1892 extended and strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, requiring most Chinese Americans – native and foreign-born -- to carry an internal passport in the form of certificates of identity or face arrest and deportation. It intensified discriminatory measures against the Chinese community, fostering widespread discontent and resistance.

In response, the Six Companies initiated a national boycott against the Geary Act. The boycott aimed to unify Chinese immigrants and their supporters across the United States, urging them to refuse compliance with the law as a form of protest. It gained substantial momentum, with significant participation from Chinese communities in various cities, voicing opposition to the Act's discriminatory provisions.

The board of directors of the Chinese Six Companies, no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Based on the screen panels in the background (which remain in the Six Companies’ meeting hall at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco), the photo appears to have been taken after 1906.

Despite its initial vigor, several factors led to the ultimate collapse of the national boycott against the Geary Act. First, the federal government intensified its efforts to enforce the Geary Act. Authorities conducted widespread raids and inspections, threatening deportation and imposing harsh penalties on those failing to comply. The fear of reprisals and the potential disruption to livelihoods coerced many Chinese immigrants into reluctantly acquiescing to the Act's demands.

Second, the broader American society exhibited little sympathy or support for the Chinese community’s plight. The prevailing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country and the lack of significant political backing from other institutions diminished the effectiveness of the boycott. Without widespread solidarity, the Chinese American community struggled to sustain its resistance.

Finally, the decision by the US Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), dealt a major legal setback to Geary Act resistance and undermined the credibility of the Six Companies. The decision validated the Geary Act and created an environment of fear within the Chinese American community. The inability to overturn the Geary Act by legal means diminished trust in the Six Companies’ capacity to protect the community's interests.

Photograph of a merchant from Chinese Business Partnership Case File for Quong Lee Company, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from the files of the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office). The immigration investigative case file indicates that the individual in this photo was certified as a business partner and a "merchant" who was “able to travel to and from the U.S. as a ‘Chinese subject of exempt class’ under the ‘Chinese Exclusion Acts’ (1882-1943).” The Quong Lee & Co. (a.k.a. Quong Lee, Quong Lee Sing) operated what business directories from 1875 to 1905 variously described as a “tailor,” “general merchandise,” “clothing,” and “dry goods” business continuously at 828 Dupont Street. By the time this merchant sat for his photo in 1896, the national boycott led by Chinese merchant organizations against the Geary Act of 1892 had collapsed, and studio portraits such as this became an essential pieces of evidence to support applications for the coveted merchant exemption from the extended Exclusion Act.

This heightened sense of vulnerability played into the hands of tongs, which, capitalized on the weakened merchant community. Amidst the faltering influence of the Six Companies, tongs emerged as influential entities that would come to dominate Chinatown’s socio-political structure and shape mainstream society’s perceptions of the Chinese community for the next three decades.

“High-binders Retreat” no date. Photograph by Goldsmith Brothers (from the Cooper Chow Collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). Tong members at ease in front of their fraternal order's headquarters.

Tongs, in contrast to the Six Companies' diplomatic approach, adopted a more assertive stance in responding to discrimination and persecution faced by the Chinese community. Their readiness to protect their members (which also included merchants), and defy external pressures resonated with many disillusioned residents.

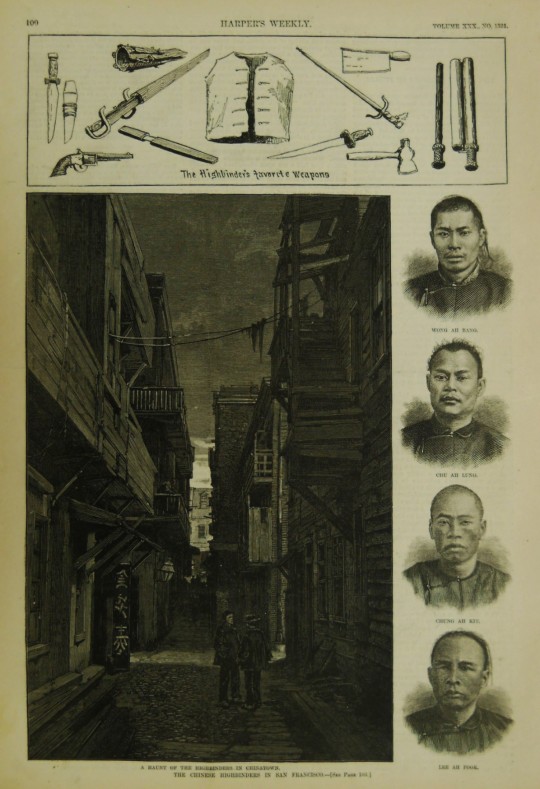

“A Haunt of the Highbinders in Chinatown.” Harpers Weekly, February 13, 1886 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

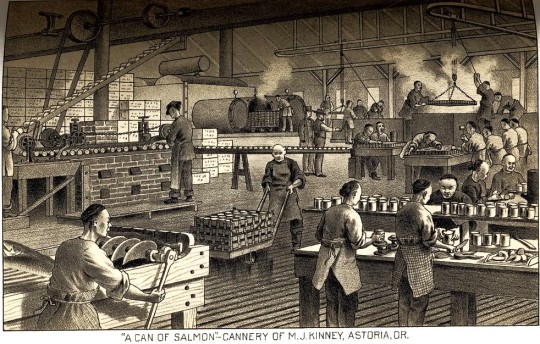

Moreover, the tongs during this period had begun to diversify their activities beyond traditional, illicitl sources of income such as prostitution, gambling, and drug distribution. Tongs began engaging in both legitimate businesses, including labor contracting for the Alaskan canneries. This diversification allowed them to accumulate resources, expanding their sphere of influence within Chinatown and beyond as alternative community governance structures, while still reserving often violent means to protect their interests.

Chinese salmon cannery works in Astoria, Oregon, c. mid-1880s. Drawing from West Shore, June 1887, from the Special Collections, University of Washington). The early 20th century would be marked by violent struggles between tongs such as the Suey Sing and Bing Kung for control over the labor contracting business for the canneries.

The ascendancy of tongs at the turn of the century coincided with the republican movement in China. Historian Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong, the original triad society, had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society’s newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

The tongs’ economic power and their active involvement in fundraising for the republican movement not only showcased their financial strength but also demonstrated their ability to wield influence as an overlapping and sometimes counter-force with the merchant elite. This dual role as (1) economic powerhouse within the local community, and (2) significant contributor to a revolutionary cause overseas underscored their influence. The growth of that influence came at the expense of the merchant elite in shaping both local and international affairs.

Merchants, however, would continue to exert influence through clan organizations, tongs, business associations, Nationalist Party of China chapters, and Chinese “consolidated benevolent associations” in San Francisco Chinatown and communities across North America through the exclusion era, war, and peace.

The meeting hall of the Chinese Six Companies, c. 1920 (by then incorporated as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco. Photographer unknown (from the Jese B. Cook collection of the Bancroft Library).

Chinatown's merchant community would face new challenges to their capacity as civic leaders when the political center of gravity across US Chinatowns would shift again in the last quarter of the 20th century.

[updated 2023-12-28]

#Chinatown merchants#Sing Man#Choy Chew#Chinese Merchants Exchange#Fung Tang#Lai Chun-chuen#Chy Lung & Co.#Yee Ah-Tye#Chinese Six Companies#Kai Suck#Ann Ting Gock#Lew Kan#Chee Kung Tong#Quong Lee & Co.

0 notes

Text

900 Artifacts From Ming Dynasty Shipwrecks Found in South China Sea

The trove of objects—including pottery, porcelain, shells and coins—was found roughly a mile below the surface.

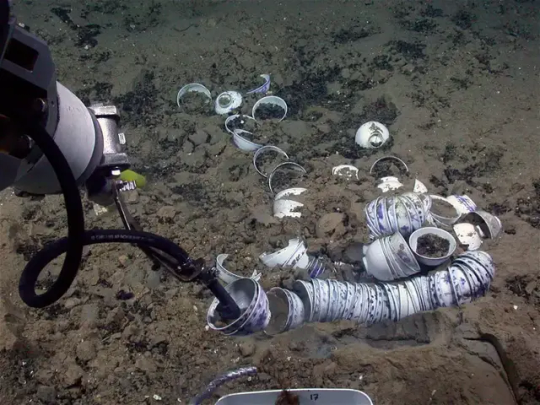

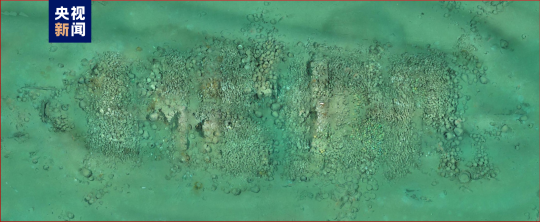

Underwater archaeologists in China have recovered more than 900 artifacts from two merchant vessels that sank to the bottom of the South China Sea during the Ming dynasty.

The ships are located roughly a mile below the surface some 93 miles southeast of the island of Hainan, reports the South China Morning Post’s Kamun Lai. They are situated about 14 miles apart from one another.

During three phases over the past year, researchers hauled up 890 objects from the first vessel, including copper coins, pottery and porcelain, according to a statement from China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration (NCHA). That’s just a small fraction of the more than 10,000 items found at the site. Archaeologists suspect the vessel was transporting porcelain from Jingdezhen, China, when it sank.

The team recovered 38 items from the second ship, including shells, deer antlers, porcelain, pottery and ebony logs that likely originated from somewhere in the Indian Ocean.

Archaeologists think the ships operated during different parts of the Ming dynasty, which lasted from 1368 to 1644.

Many of the artifacts came from the Zhengde period of the Ming dynasty, which spanned 1505 to 1521. But others may be older, dating back to the time of Emperor Hongzhi, who reigned from 1487 to 1505, as Chris Oberholtz reported last year.

Archaeologists used manned and unmanned submersibles to collect the artifacts and gather sediment samples from the sea floor. They also documented the wreck sites with high-definition underwater cameras and a 3D laser scanner.

The project was a collaboration between the National Center for Archaeology, the Chinese Academy of Science and a museum in Hainan.

“The discovery provides evidence that Chinese ancestors developed, utilized and traveled to and from the South China Sea, with the two shipwrecks serving as important witnesses to trade and cultural exchanges along the ancient Maritime Silk Road,” says Guan Qiang, deputy head of the NCHA, in the agency’s statement.

During the Ming dynasty, China’s population doubled, and the country formed vital cultural ties with the West. Ming porcelain, with its classic blue and white color scheme, became an especially popular export. China also exported silk and imported new foods, including peanuts and sweet potatoes.

The period had its own distinctive artistic aesthetic. As the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art writes, “Palace painters excelled in religious themes, moralizing narrative subjects, auspicious bird-and-flower motifs and large-scale landscape compositions.”

The shipwreck treasures aren’t the only recent discoveries in the South China Sea, according to CBS News’ Stephen Smith. Just last month, officials announced the discovery of a World War II-era American Navy submarine off the Philippine island of Luzon.

By Sarah Kuta.

#900 Artifacts From Ming Dynasty Shipwrecks Found in South China Sea#island of Hainan#Ming dynasty#shipwreck#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient china#chinese history#chinese art#ancient art

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stone Turtle of Karakorum, Mongolia, c. 1235-1260 CE: this statue is one of the only surviving features of Karakorum, which was once the capital city of the Mongol Empire

The statue is decorated with a ceremonial scarf known as a khadag (or khata), which is part of a Buddhist custom that is also found in Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan. The scarves are often left atop shrines and sacred artifacts as a way to express respect and/or reverence. In Mongolia, this tradition also contains elements of Tengrism/shamanism.

The city of Karakorum was originally established by Genghis Khan in 1220 CE, when it was used as a base for the Mongol invasion of China. It then became the capital of the Mongol Empire in 1235 CE, and quickly developed into a thriving center for trade/cultural exchange between the Eastern and Western worlds.

The city attracted merchants of many different nationalities and faiths, and Medieval sources note that the city displayed an unusual degree of diversity and religious tolerance. It contained 12 different temples devoted to pagan and/or shamanistic traditions, two mosques, one church, and at least one Buddhist temple.

As this article explains:

The city might have been compact, but it was cosmopolitan, with residents including Mongols, Steppe tribes, Han Chinese, Persians, Armenians, and captives from Europe who included a master goldsmith from Paris named William Buchier, a woman from Metz, one Paquette, and an Englishman known only as Basil. There were, too, scribes and translators from diverse Asian nations to work in the bureaucracy, and official representatives from various foreign courts such as the Sultanates of Rum and India.

This diversity was reflected in the various religions practised there and, in time, the construction of many fine stone buildings by followers of Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity.

The prosperous days of Karakorum were very short-lived, however. The Mongol capital was moved to Xanadu in 1263, and then to Khanbaliq (modern-day Beijing) in 1267, under the leadership of Kublai Khan; Karakorum lost most of its power, authority, and leadership in the process. Without the resources and support that it had previously received from the leaders of the Mongol Empire, the city was left in a very vulnerable position. The residents of Karakorum began leaving the site in large numbers, until the city had eventually become almost entirely abandoned.

There were a few scattered attempts to revive the city in the years that followed, but any hope of restoring Karakorum to its former glory was then finally shattered in 1380, when the entire city was razed to the ground by Ming Dynasty troops.

The Erdene Zuu Monastery was later built near the site where Karakorum once stood, and pieces of the ruins were taken to be used as building materials during the construction of the monastery. The Erdene Zuu Monastery is also believed to be the oldest surviving Buddhist monastery in Mongolia.

There is very little left of the ruined city today, and this statue is one of the few remaining features that can still be seen at the site. It originally formed the base of an inscribed stele, but the pillar section was somehow lost/destroyed, leaving nothing but the base (which may be a depiction of the mythological dragon-turtle, Bixi, from Chinese mythology).

This statue and the site in general always kinda remind me of the Ozymandias poem (the version by Horace Smith, not the one by Percy Bysshe Shelley):

In Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,

stands a gigantic leg

which far off throws the only shadow

that the desert knows.

"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,

"the King of Kings; this mighty city shows

the wonders of my hand."

The city's gone —

naught but the leg remaining

to disclose the site

of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder —

and some Hunter may express wonder like ours,

when thro' the wilderness where London stood,

holding the wolf in chace,

he meets some fragment huge

and stops to guess

what powerful but unrecorded race

once dwelt in that annihilated place

Sources & More Info:

University of Washington: Karakorum, Capital of the Mongol Empire

Encyclopedia Britannica: Entry for Karakorum

World History: Karakorum

#archaeology#history#anthropology#artifact#ancient history#mongol empire#mongolia#karakorum#middle ages#ancient ruins#art#turtle#bixi#ozymandias#poetry#mythology#genghis khan

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Penang is well-known for its vibrant Straits Chinese Peranakan culture, but if you know where to look, there’s another chapter to its history. While the focus is often on the marriage between overseas Chinese traders marrying local Malay women, the truth is, the Chinese were not the only traders conducting business in George Town. Merchants from around the region were familiar with Penang, having already flowed through Penang on various trading missions.

Between the 10th and 18th centuries, traders and migrants from India, Persia, and the Middle East arrived in Penang. Their marriages with local Malay women gave rise to a new branch of the Peranakans, known as Jawi Peranakan, with Jawi denoting Southeast Asian Muslims, and Peranakan taking its meaning from the Malay word ‘anak’, or child. Over time, this group expanded to include those who had Arab-Malay ancestry. In Penang, they were also once known as Jawi Pekan.

The Jawi Peranakan cuisine, much like its Chinese cousins, draws on cultural exchanges between Malay cuisine and its Indian, Arab, and Persian influences. Jawi Peranakan dishes tend to feature ingredients from India and the Middle East, including ground almonds and cashews, saffron, and rosewater. The cuisine of the Jawi Peranakan was generally recognized to be more lavish, and was often served during feasts and special occasions.

To get a taste of this chapter of Peranakan history, visit Jawi House, located on Armenian Street in the heart of George Town’s downtown heritage district. The house was recently renovated in 2012 according to UNESCO World Heritage Guidelines, but it has existed for six generations. It was established by the Karim family of Punjabi-Jawi Peranakan history, and today functions as not just a restaurant showcasing a modern take on Jawi Peranakan cuisine, but also as a small gallery charting the family’s history as well as classic handcrafted art.

Helmed by Chef Nurilkarim Razha, a descendant of the Karim family, the restaurant offers up iconic Jawi Peranakan fare. Popular dishes include lamb bamieh, a fragrant, aromatic Persian-inspired okra and tomato-based lamb stew; serabai, a Malay kuih which resembles a tangy, spongier pancake made from fermented rice batter and served with caramel kaya (coconut jam); and nasi lemuni, an herbaceous rich rice dish cooked with butterfly pea flowers and the herb Vitex trifolia.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Defense of Our Nightingales

When I was a child, I'd spend each weekend with my Nana, and she would take me to the library for books and then read to me every evening.

One story that deeply impacted me was The Emperor's Nightingale by Hans Christian Anderson, which he wrote in tribute to Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind.

There are many versions and retellings, but it is essentially the tale of a Chinese emperor and his beloved nightingale that goes something like this:

Once upon a time in China, there was a great palace made of porcelain and surrounded by beautiful gardens. Behind the gardens was a wooded area that stretched to water. Within the woods lived a nightingale with the most beautiful song. So beautiful, in fact, travelers would come from all over to hear the bird.

When the Emperor received word of this, he immediately commanded that the nightingale be brought to court so that it could sing for him. The nightingale was put in a gilded cage and presented to the Emperor. He was quite surprised that it was such a simple-looking bird that could make such an incredible tune.

He fell in love with the bird and its abilities and would cry when he heard it sing. Everyone at court celebrated the wonderous creature.

One day, a rich merchant gifted the Emperor with a mechanical nightingale made of gold and bedecked with gems. Overjoyed by this modern technical marvel, the Emperor had the real bird and mechanical bird attempt to sing together.

It did not work because the real bird sang its own melodies, not a predictable string of notes.

When the mechanical nightingale sang alone, the melody imitated the beauty of the real bird well enough, and it was much more attractive to look at. It didn't tire. It didn't need to be tended. It didn't long to fly. So the Emperor preferred it.

Heartbroken, the real nightingale decided to fly back to the woods.

Upon realizing his departure, everyone slandered the bird for deserting the court. They threw all of their loyalty to the new mechanical bird, harshly besmirching the real nightingale in the process.

The mechanical bird was given a seat beside the Emperor's bed and gave public concerts each week, while the real nightingale was banished from court.

Over the years, the emperor became bored with the mechanical bird's repetitive songs, and eventually the machine wore down and fell silent anyway.

Then one day, the Emperor fell ill. On his death bed, he begged for his golden bird to sing a comforting song, but it did not. Yet outside his window, the real nightingale sat perched on a branch watching over him.

The bird sang a tune so lovely, that Death itself agreed to leave the emperor alive in exchange for more music.

(In other versions I've come across, the nightingale died of a broken heart, and so the emperor succumbed to his illness.)

This story DEEPLY DISTURBED me as a kid. I refused to go anywhere near life-like baby dolls or animatronic toys from then on. (Huge robotic rats at Chuck E. Cheese or miniature stuffed animals never bothered me--but if it looked like something fake was imitating real life, I absolutely rejected it.) I went to Disney years ago for my 30th birthday and the Tiki Room honestly made me break out in a flop sweat and hives--that's how visceral my reaction is to this fable, even as an adult.

That's great, Roo, but why are you bringing this up?

Lately, I keep thinking about Hybe's plans to embrace AI.

I understand that Artificial Intelligence is inevitable, and when it comes to practicum (like dissecting virtual animals so the real ones are spared, or using simulation labs to teach medical students how to perform complicated procedures that won't put live patients at risk), I'm generally on board. Technology is a useful tool.

But the idea that a lifeless, soulless, hollow machine could ever replace our artists, our writers, our singers...?

It sickens me.

Don't people understand, it's the unique foibles, the fragile propensity to make and then overcome errors, and the ability to evolve and change during the acts of creation that separates art from product?

The world is filled with sound. The same musical notes will exist long after humanity is wiped out.

But without a soul to appreciate it, without a beating heart to create music based on real emotion, without a spirit to put a unique signature on it... it's just noise.

The music industry wants to sell repetitive noise, crafted expeditiously by modern technological marvels, packaged in fake gold and jewels.

People will tire of it quickly.

But by then... what will have happened to our artists' hearts?

Who will save us from death and despair?

I will always choose the real nightingales.

Always.

I hope you will, too.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worldbuilding: Loading Cultural Bullets

Here’s an underused story setting element that might come up more often; the diplomatic cultural visit.

Up until fairly modern times, sending a full-time ambassador to a foreign land to hang around and pass diplomatic messages back and forth was... not so much of a thing. Travel was hard, groups mostly only came into contact on borders (suspicious) and through merchant trade (desirable and so even more suspicious). Nobody sane deliberately went to another land to put themselves in the middle of politics. That’s the kind of thing that could result in your head and your neck parting ways, very messily. See the history of the Polo family (yes, that Polo, named Marco) desperately trying to come up with excuse after excuse to leave the court of Kublai Khan when it became evident the ruler was on the way out.

So generally what happened instead was that an ambassador’s party would be sent on a semi-regular basis - reign changes, every few years, sometimes both - to bring tidings of well-wishes, death threats, and what have you. Messages would be exchanged, pomp and splendor would be seen, trade would happen (sometimes under the guise of tribute and return-gifts), and any survivors would then return to their country of origin. If they were lucky.

And then there might be less regular embassies, often to show off your home culture to the people you were trying to impress. A few examples include the treasure fleets of Zheng He, a massive display of Ming Dynasty power and technology around the coasts all the way to India; the Great White Fleet of Theodore Roosevelt, meant to impress upon Europe and other places (including Japan) that the U.S. was no mere scrabbling frontier nation but a force to be reckoned with; and the T’ongsinsa of Joseon Korea visiting Tokugawa Japan.

Those last visits actually shared some motives in common with the Great White Fleet, to deter war with Japan. Though Joseon’s aim (besides hoping to avoid any repeat of the Imjin War) was also to show how civilized they were, and exchange a lot of literary and cultural knowledge. It apparently was a visit eagerly looked forward to on both sides; even if sometimes individuals couldn’t talk to each other, a shared intellectual knowledge of Chinese made a lot of brush-talk possible, and the poetry exchanges were apparently Not To Be Missed.

Consider all this as a setting for your characters. They could be directly involved in the embassy. They could be random scholars or adventurers hoping to meet the embassy, or steal their secrets, or just get a glimpse of the spectacle. They could be the poor beleaguered local law enforcers who have to maintain security when feelings are running high. Just ask any con staff who’s wrangled SF fans how tense it can get! What are the cultures in your world? Who might they want to show off to?

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

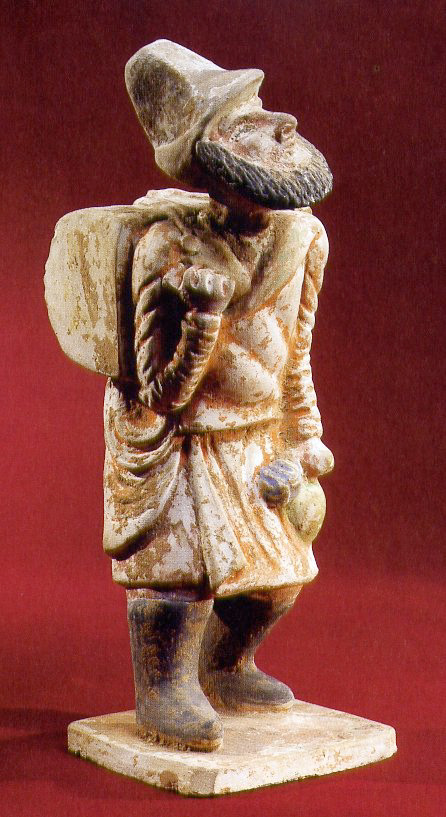

Foreign merchant (with Sogdian appearance) in China 618-907 CE

By the time the Hephthalites (White Huns) were destroyed the Sogdians had such a widespread influence that they were able to continue to enjoy their prosperity for another century. However, the crippling of the Hun's power by the Turks and Persians also eliminated Sogdiana's safety net and made them vulnerable. The chaos created to the east by the Turkic An Lushan rebellion in China and the chaos created to the west by the Sassanid's blundered aggression closed the doors on the Sogdian era of prosperity that had begun under Hunnic rule. Even after the An Lushan rebellion ended, China [one of the Sogdian's most important trading partners] was in ruins and vulnerable to other threats. Trade routes were choked off by hostile armies. Instability meant more danger for travelers. Sassanid rule had become so dysfunctional that the primitive Arab Muslims were able to conquer Persia, afterward pushing on into Sogdiana. The Hephthalites were no longer there to stabilize the Persian government as they had done in the time of Peroz and Khuvad. The Sassanids had gained their financial freedom from the Hephthalites and then, less than a century later, used that freedom to destroy themselves.

"In July of 751, a Tang army was defeated at the battle of Talas at the hands of a Turgesh-Arab alliance. The defeat effectively ended the Tang’s ability to intervene in Asia beyond the Tarim Basin. This defeat and the Tang’s subsequent inability to project force beyond the Tarim Basin played as important role in the downfall of the Sogdians as the Arab invasions themselves. With the Tang military held behind the Pamirs, the Tibetans moved to occupy the passes leading into China and into Kashmir, creating a chokehold on valuable trade networks the Sogdian merchants depended on for their livelihoods. Campaigns in 747 CE and 753 CE served to ease these Tibetan holds on the passes, but relief was only temporary. The Tang loss at Talas freed the invading Arabic forces to take control of Central Asia as well as weakening the Tang’s ability to cope with longstanding enemies closer to home. The situation for both the Sogdians and the Tang was only going to worsen. Taking advantage of the inner turmoil caused by An Lushan’s rebellion, Tibetan troops marched on and captured Chang’an in 763 CE. Rather than attempting to hold the city the Tibetans gradually withdrew along the Gansu corridor. Movement up this major trade artery by a hostile army could only have disrupted the Sogdian’s trade network, which was already likely in poor condition due to rebellions and the depredations of preceding armies. As the Tibetans withdrew they occupied the cities they encountered along the way, taking first Liangzhou (764) in the east and eventually Hami (781–782) in the west. At least two key Sogdian colonies at Hami and Chang’an, would have been seriously damaged by the rampaging Tibetans.

It is also quite likely that throughout their operations in China, Sogdian wealth would have proved a tempting target for looting by invading armies such as the Tibetans or rebelling generals. The Tibetan occupation of the passes restricted any influx of Sogdian immigrants into China to bolster the reeling Sogdian communities. With China wracked by invasions and rebellions, their Chinese colonies in ruins, the mistrust of the Sogdian people by the Tang due to the rebellion of An Lushan, and their homeland occupied by invading armies, the Sogdian trade network and nation could not but have suffered grievously. Previously the Sogdians had shown a remarkable ability to escape destruction, but the combination of forces besieging them eventually proved too great.

The Sogdians embodied the spirit of the Silk Road perhaps better than any other people. The Silk Road functioned as a conduit for exchange of both ideas and goods. The Sogdians for hundreds of years served as an invaluable vehicle for that exchange."

-The "Silk Roads" in Time and Space: Migrations, Motifs, and Materials. Edited by Victor H. Mair. Sino-Platonic Paper 228.

#sogdiana#tang dynasty#chinese art#ancient history#silk road#history#antiquities#art#sculpture#statue#ancient art

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xuanzang's Cassock (2012) 玄奘袈裟

Director: Zhang Xin

Screenwriter: Wu Huaijie

Starring : Song Tao / Ji Wen

Genre: Drama

Country/Region of Production: Mainland China

Language: Mandarin Chinese

Date: 2012

Duration: 83 minutes

Type: Crossover

Summary:

The movie "Xuan Zang's Kasaya" tells the story of the treasure "Hundred Gold Clouds and Water Moji Kasaya" left by Master Xuanzang, an eminent monk of the Tang Dynasty, who was dedicated in Mogao Grottoes on the eve of the Revolution of 1911. Suddenly, various forces gathered in Dunhuang, each with different purposes in search of the treasure cassock. Rongqing, the Minister of Academic Affairs, strongly recommended Yao Kun, a bachelor of the Hanlin Academy, to go to Dunhuang to search for Xuanzang's cassock, hoping to use the magic power of the treasure to save the precarious Qing Dynasty. Yao Kun and his cousin, antique businessman Xia Zifeng, disguised themselves as businessmen and headed to the desert. Yao and Xia went to the "Sihai Inn" and met the proprietress Yu Niang. They also met Guan Yanfei and Guan Yanruo, brothers and sisters, sons of the Gansu General Soldier. The Guan brothers and sisters also came here to find the cassock. His elder brother Guan Yanfei was secretly coerced by Yuan Shikai.

In order to protect the family from Yuan Shikai's persecution, he secretly assisted the commander Cang Lang sent by Yuan Shikai to snatch Xuanzang's cassock and sell it to foreigners in exchange for arms. The simple and reckless Guan Yanruo thought he was looking for the cassock. It was for the sake of the imperial court, and out of eagerness to protect the treasure. He was afraid that something might happen if the cassock fell into the hands of a merchant, so he wanted to find the cassock before Yao and Xia, so he opposed them at every turn. The clues to find the cassock were so intertwined and obscure that everyone racked their brains and couldn't find the way. In the end, the knowledgeable Yao Kun first found the clue. Guan Yanfei took advantage of his plan and simply used Yao Kun to follow him to gradually get closer to the treasure cassock.

In the confrontation with Yao Kun, Guan Yanruo was gradually moved by Yao Kun's integrity and kindness and developed a good impression. In the process of searching for Kasaya, he discovered that his family was being controlled by Yuan Shikai's special envoy, Cang Lang. The search for the cassock was also ordered by Yuan Shikai, not to protect the national treasure. As everyone gets closer and closer to the cassock, Cang Lang forces Guan Yanfei to do whatever it takes to get the cassock as soon as possible. In order to get the final clue, Guan Yanfei puts Yao and Xia into a dungeon. After being tortured, Xia Zifeng told Guan Yanfei where the cassock was buried in order to save his cousin Yao Kun. So Canglang took Guan Yanfei and his men straight to Baobogou. At this time, Guan Yanruo used a trick to kill Yao Kun and Xia Zifeng. During the escape, the three were discovered by the Qing soldiers guarding them, and they were assisted by Yu Niang at the critical moment.

After defeating the Qing soldiers and rescuing them, it turned out that Yu Niang was a private treasure-protecting organization that had been operating near Dunhuang. After learning that Yao Kun was ordered to protect the cassocks, she had already sent people to observe secretly. In the end, while protecting the treasure With the help of others, Yao Kun and others got the cassocks first, but were surrounded by soldiers brought by Cang Lang and Guan Yanfei. When they were desperate, Yu Niang and her men arrived again. It turns out that Yu Niang and Xia Zifeng are both folk treasure protectors, and they lurked in the desert to protect the national treasure. A melee broke out between good and evil. Guan Yanfei tried to protect his sister and had a dispute with Canglang. Guan Yanruo was injured by Canglang in the melee. Guan Yanfei also died under Canglang's knife while trying to save his sister. In the end, Yao Kun killed the wolf and ended the melee. Yao Kun returned to the capital with the treasure cassock. Looking back on what he saw and heard during the treasure hunt, he deeply felt that the Qing government could no longer save the country. And the Qing Empire that he worked hard for ended its 268-year rule in depression... No so-called "divine power" can withstand the rolling tide of history.

Source: https://movie.douban.com/subject/20427158/

Link: N/A

#Xuanzang's Cassock#玄奘袈裟#jttw media#jttw movie#movie#lost media#live action#crossover#tang sanzang reference

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Youjinbou to Nigeria Hanayome

『用心棒と逃げた花嫁』《保鑣和落跑的新娘》

By: Rico Sakura

Traveling Merchant x Fugitive Prince

The third prince, Amiru, fled on the eve of his political marriage and met Sai, who claimed to be a traveling merchant. Although Amiru was very wary of this man who confidently said he wanted to help him, he still naturally took his hand. As soon as Sai catches a flaw, he will tease the innocent Amiru. Although Amiru is very unhappy about this, the two become more and more inseparable from each other while exchanging loneliness and their thoughts. However, the pursuers gradually approached. What is the true identity of the mysterious Sai...? Then, the two people attracted to each other will...

Japanese: https://www.cmoa.jp/title/254679/vol/1/

Chinese: https://www.bookwalker.com.tw/product/175579

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! You said you'd be accepting WBW/STS asks, so: here's an ask! Happy WBW!!

What's art like in your WIP's world? How does it differ from place to place, what form does it take, what subjects does it portray, etc.? You don't need to answer all of these, just ramble to your heart's content!

And, if you don't have a lot of worldbuilding around art, tell me about your world's language(s)! I'd be just as interested in hearing that!

Let's pretend it's still Wednesday please. And thanks fir the ask! I really missed these exchanges, they were my life all summer and I'm super sad it kinda died down and that I disappeared. But I'm trying to get back on track! So!

As for art, I am kinda in a slump right now, because that is a part of the worldbuilding I jave absolutely not flashed out. I think I will try to stay true to the historical settings, but maybe adding some more fantasy elements here and there.

As fir languages OH BOY. I love languages. I am studying them, and their mechanics 24/7. I made that my uni major. I feed on linguistics, all the throats movement to articulate the sounds. The structures of every sentence broken down. The language learning aspect.

I am pretty sure this book is born 69% because I wanted an outlet for all that.

So

There are actually a lot lot lot of languages. First of, the one that is called Common. Is a superlanguage that is kinda spoken all around Unyon'he. Obviously though not everyone can speak it properly. Think Latin in the middle ages. It was spoken by ecclesiastical people and whatnot, but commoners could not speak it at all. Except that at least 4/5 of my charachters have recieved higher education so they can. What makes it worse though, is that all the countries that spoke Latin where of the same linguistic roots, that us Indo European.

My five countries instead speak all different languages, based on real world Arabic, German, Chinese, Portuguese/Spanish, and Finnic/Swedish. So all of a different root. At this point I think I should reconsider Commin language as a whole core concept because it is just so fucking difficult.

Unless I make it a god given language which yeah. Could work.

MOREOVER! Think about dialects. So each country is divided in regions, and more or less they all have different dialects. And what about all the nomad merchants in Tijara? Yep. Complicated.

And then there are sign languages of course, which are very important bc Nayeli is very much deaf, thank you, and it is the only way she can communicate with the rest of the Squad.

So how many languages are there? 30/40 I guess. Yay for me!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Account of Central Tianzhu (LS54)

天竺, Middle Chinese *Then-trjuwk, Standard Chinese Tiānzhú, and 身毒, Middle Chinese *'Jwien-dowk, Standard Chinese Yuāndú, both derive from Iranian Hinduka and ultimately from Sanskrit Sindhu. As such these names have the same etymological origin as India.

師子, Middle Chinsee *Srij-tsi, Standard Chinese Shīzǐ, is the Sinhala kindom on Sri Lanka.

…

The state of Panpan, during Emperor Wen of Song's Yuanjia era [424 – 453] and Xiaowu's Xiaojian [454 – 456] and Daming [457 – 464] eras dispatched envoys with tribute to present.

…

The state of Gantuoli is located on an island in the Southern Sea. Their customs are roughly similar to Linyi and Funan. They produce ban班 cloth, jibei [tree cotton], and betel nut. The betel nuts are especially excellent, the pinnacle among the various states. During Xiaowu of Song's reign [454 – 464 AD], King Shipoluo Ranfuliantuo dispatched Senior Clerk Zhuliutuo to present gold, silver, and precious vessels.

…

The state of Central Tianzhu is located several thousand li south-east of Greater Yuezhi. The land is 30 000 li square. It is also named Yuandu. In the Han period Zhang Qian was sent to Daxia where he saw Qiong bamboo canes and Shu cloth. People of the state said they bought it in Yuandu. Yuandu is precisely Tianzhu. Probably the transmitted transcription of the sound and character are not similar, they really are the same. In the times of Han, they were controlled by and belonged to Yuezhi. Their customs and native characteristics are similar to the Yuezhi, but they are low-lying and humid, and feverishly hot. The people are weak and fearful in battle, and are weaker than the Yuezhi. The state is near a great river named Xintao which springs forth from Kulun and divided to become five rivers. Collectively they are called the Geng River [I.e. the Ganges]. Its water is sweet and pleasing. In it is true salt, coloured exactly white like water essence.

Native customs produce rhinoceros, elephant, marten, gerbil, hawksbill turtle, “fire blend” [huoqi火齊], gold, silver, iron, gold threads woven into complete gold felt, finely rubbed white folded [fabric?], excellent furs, and wool rugs. “Fire blend” is shaped like mica and is coloured like purple gold. It has a glowing sparkle. If divided up, it is thin like cicada wings. If piled up, it is like the layers of gauze or crepe. To their west they exchange and trade with Daqin and Anxi within the seas. There is much of Daqin's precious things – coral, amber, golden blue-green gems, pearls, gemstone-jade, tumeric, and storax. Storax is made by combining various fragrant saps and boiling them, it is not naturally from a single thing. It is also said that the people of Daqin gather storax, first press it for the sap to use as a fragrant ointment, and then sell its dregs to merchants from various states. Thus when it in turns come to the Central States, it is not very fragrant. Tumeric is only produced in the state of Jibin. The flowers are coloured exactly white and are delicate. It and those lotus flowers that are enclosed in the lotus leaves resemble each other. The people of the state first take it and send it up to the Buddhist temples, and for a number of days the fragrance wither, and then they clear away and remove it. Merchants seek out hirelings from within the temples, and so move it to sell to other states.

Emperor Huan of Han's 9th Year of Yanxi [166 AD], the King of Daqin, Antun, dispatched envoys to come and present from outside the frontiers of Rinan, during the Han period it was the only communication with them. The people of that state travel as merchants, from time to time arriving in Funan, Rinan, and Jiaozhi. Among the people from the various states on their southern frontiers there are few that have reached Daqin.

Sun Quan's 5th Year of Huanwu [226 AD], there was a merchant from Daqin, Ziqinlun, who came to Jiaozhi. The Grand Warden of Jiaozhi, Wu Miao sent him off to Quan. Quan asked about the region's native songs and customs. Lun provided detailed answers to the matters. At the time Zhuge Ke chastised Danyang, and captured short people from Yi and She [counties]. Lun saw them and said:

In Daqin [we] rarely see this [kind of] people.

Quan had men and women, ten each, and the selected envoy Liu Xian of Kuaiji sent off with Lun. Xian suffered a mishap on the road, and Lun then went straight back to his home state.

In the time of Emperor He of Han [r. 88 – 105 AD], Tianzhu several times dispatched envoys with tribute to present. Later the Western Region turned to rebellion and consequently they were cut off. Arriving at Emperor Huan's 2nd Year [159 AD] and 4th Year of Yanxi [161 AD], they frequently came from outside the frontiers of Rinan to present.

In the Wei and Jin periods, they were cut off and did not again communicate. However in the time of Wu, the King of Funan, Fan Zhan, dispatched a relative, Suwu, as envoy to their state. From Funan he issued forth from the mouth of the Juli, circled around a great bay in the sea, and straight north-west entered successive bays bordering several states. It could have been more than a year when he arrived at the mouth the Tianzhu river. He travelled against the water for 7 000 li and then arrived there. The King of Tianzhu was startled and said:

At the sea coast furthest away they still have this person.

He promptly shouted out orders to observe and take a look inside the state, and carried on selecting Chen and Song, two persons, with four Yuezhi horses as repayment to Zhan, and dispatched them to go back with Wu and others. After a total of four years exactly they arrived. At that time Wu dispatched Central Gentleman Kang Tai as envoy to Funan. When he saw Chen, Song, and others, he comprehensively asked about Tianzhu's native customs, as follows:

The Way of the Buddha is what fosters the state. The people are sincere and varied, and the land is fertile and well-watered. Their king is titled Maolun. The capital is a walled city. Water springs forth in a split flow, entwines it in a knot of channels [?], and flows down into the great river. Their palace halls all are engraved and patterned with inlays and carvings. There are bending streets, markets and residential compounds, buildings, storied houses and towers, bells, drums, tones and music, clothes, decorations and fragrant flowers. Communication flows by water and land, a hundred merchants exchange and gather, and there are strange playthings and precious jewels to indulge the heart's desires. To their left and right are Jiawei, Shewei, Yebo, and others, sixteen great states, their distance to Tianzhu is perhaps two or three thousand li. They all together respect and serve them, and consider them to be at the centre of Heaven and Earth.

…