#Chee Kung Tong

Text

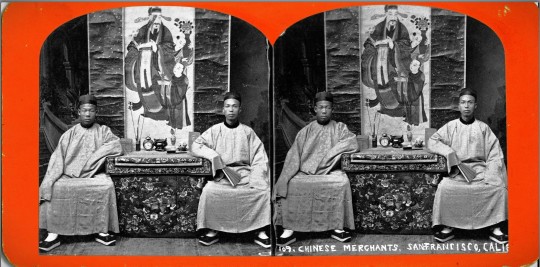

“109. Chinese Merchants, San Francisco, Calif.” c. 1890 – 1899? Stereograph by Nesemann Woods Gallery, Marysville CA (from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection of the University of British Columbia Library).

Merchants of Old Chinatown

In the late 1840s and the 1850s, Chinese merchants and traders made their initial foray into California. By February 1849, the number of Chinese had increased to 54 and by January 1850, historians would count 787 men and two women in San Francisco. In December 1849, the Alta California newspaper reported that 300 Chinese convened a meeting at the Canton Restaurant on Jackson Street for the purpose of organizing the “Chinese residents of San Francisco” and engaging the services of lawyer Selim E. Woodsworth to “act in the capacity and adviser for them.”

In his book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, historian John Tchen wrote about the vanguard of old San Francisco Chinatown’s merchant elite as follows:

“These pioneers hailed primarily from the Sanyi (Saam Yap) or Three Districts [三邑], as well as the Zhongshan area in the immediate vicinity of Canton. It's important to note that Nanhai (Namhoi) and Panyu (Punyu) stood out as the most prosperous districts within Guangdong Province. Their economic pursuits ran the gamut from cultivating fertile agricultural lands, breeding silkworms and fish, to crafting silk textiles, producing ceramics for both domestic and international markets, and engaging in various other commercial endeavors.

“What set apart the merchants and artisans from Sanyi and Zhongshan was their mastery of a more refined city dialect compared to their Siyi (Sei Yap) counterparts, who mainly consisted of poorer, rural communities. Remarkably, over 80 percent of Chinese immigrants in North America originated from the Siyi [四邑] region. A noteworthy portion of these Sanyi merchants belonged to the emerging class of compradores, individuals who facilitated business transactions on behalf of Western trading companies. These California-based Sanyi merchants thus brought prior experience in dealings with Western entrepreneurs, and California was seen as a promising arena to expand these lucrative connections.”

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May of 1869, the more sophisticated and adventurous members of San Francisco’s pioneer Chinese merchant community would begin exploring other cities in the United States in search of opportunity.

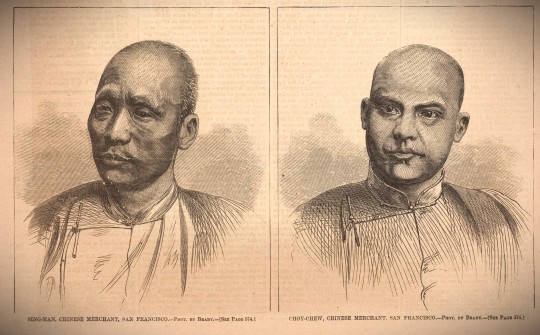

“Sing-Man, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco” and “Choy-Chew, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco,” Harper’s Weekly, September 4, 1869, wood engraving on paper. Artist unknown, artist after a photograph by Mathew Brady, 1869 (from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).

For example, in the Harper’s Weekly article (Sept 4, 1869, page 574), the reporter identified merchant Choy Chew as a San Franciscan and a talented linguist of sufficient intellect and stature to be invited to give a speech at a European-American banquet. He reportedly visited Chicago with a fellow merchant, Sing Man, before traveling to New York where the pair were regarded as “representatives of Chinese industry and commerce.”

At the banquet in Chicago, Choy Chew delivered the following remarks:

”Eleven years ago I came from my home to seek my fortune in your great Republic. I landed on the golden shore of California, utterly ignorant of your language, unknown to any of your people, a stranger to your customs and laws, and in the minds of some an intruder — one of that race whose presence is deemed a positive injury to the public prosperity. But gentlemen, I found both kindness and justice. I found that above the prejudice that had been formed against us, that the hand of friendship was extended to the people of every nation, and that even Chinamen must live, be happy, successful and respected in ‘free America.’ I gathered knowledge in your public schools; I learned to speak as you do; and, gentlemen, I rejoice that it is so; that I have been able to cross this vast continent without the aid of an interpreter; that here in the heart of the United States I can speak to you in your own familiar speech, and tell you how much, how very much, I appreciate your hospitality; how grateful I feel for the privileges and advantages I have enjoyed in your glorious country; and how earnestly I hope that your example of enterprise, energy, vitality, and national generosity may be seen and understood, as I see and understand it, by our Government …

”We trust our visit, gentlemen, may be productive of good results to all of us; that the two great countries, East and West, China and America, may be found forever together in friendship, and that a Chinaman in America, or an American in China, may find like protection and like consideration in their search for happiness and wealth.“

-- from the Scientific American, new series, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 131 (August 28, 1869)

The founding in 1888 of the Merchants’ Exchange in old San Francisco Chinatown represented the logical culmination of several decades of robust business operations by the pioneer Chinese merchants in the city and beyond.

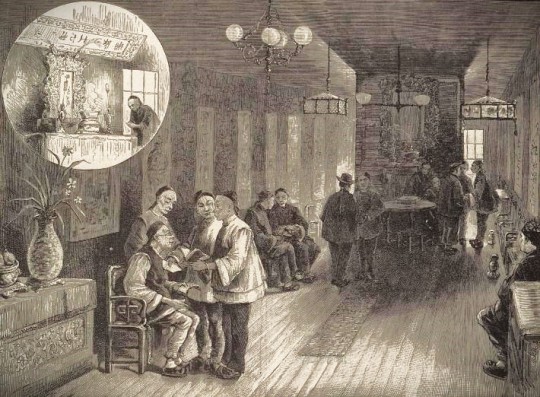

“Chinese Merchants’ Exchange, San Francisco.” Lithograph from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 26, March 18, 1882 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In his book, A Guide Book to San Francisco (published by The Bancroft Company in 1888), John S. Hittell described the Chinese Merchants Exchange as follows:

“At 739 Sacramento Street are the new rooms of the Chinese Merchants' Exchange. They are fitted up in the ordinary Chinese style, and though presenting no special attraction to the visitor, the business transacted there is of considerable importance. A Chinese merchant, contractor, or speculator never starts on any enterprise alone. He always has at least one partner, and in most cases several. He makes no secret of his transactions, but converses about them at the exchange, and often goes there in search of capital when his own means are insufficient. He sometimes applies to that institution to find him a capable man to manage a new business which he is about to start. If, as often happens, one be selected who is in debt to other members, they make arrangements which will not interfere with the new enterprise; and the debtor is not unfrequently released from his obligations.”

Fung Tang

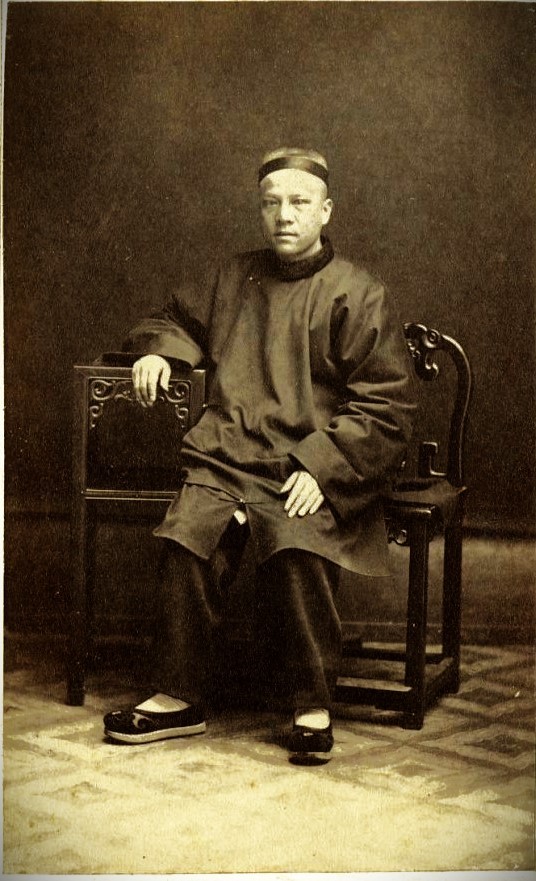

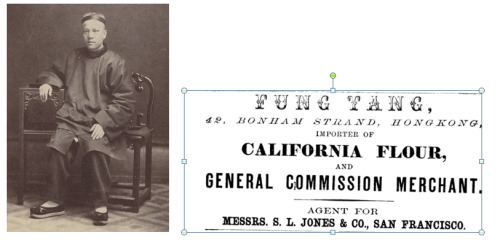

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

The address of the Merchants’ Exchange at 739 Sacramento Street was hardly surprising, as it shared the same building which had housed the mercantile house of a legendary merchant, Fung Tang. Historian York Lo, in his article for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, described Fung as “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the pioneer Chinatown photographer, Kai Suck. A professional studio portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. In fact, Fung appears to have deployed the same portrait now reposing in the collection of the California Historical Society as part of his commercial advertising in Hong Kong.

An advertisement for Fung Tang’s flour import business in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service, including his election to the board of directors of the Tung Wah clinic (the original predecessor organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encouraged to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

Tchen asserts that the influx of British and other Western imperialist powers into China’s major treaty ports transformed the status of merchants engaged with Western trading companies. Rather than operating on the margins of Qing-era society, the merchants gained unprecedented prestige and influence. Beyond China's borders, they experienced far more freedom to engage in trade and amass substantial profits without the worry of state-imposed restrictions. They rapidly acquired the necessary language skills and business acumen to navigate their newfound opportunities.

San Francisco’s early Chinese merchants swiftly grasped the English language and American business practices, excelling in American-style transactions, and developing strategies for fostering positive relations with the general San Francisco populace. The local press affectionately labeled them "China Boys." They made conscious efforts to participate in the celebrations of significant American holidays, further endearing themselves to the San Francisco community.

This approach significantly bolstered their rapport with the local population, as evidenced by the California Courier's glowing praise: “We have never seen a finer-looking body of men collected together in San Francisco. In fact, this portion of our population is a pattern for sobriety, order, and obedience to laws, not only to other foreign residents, but to Americans themselves," declared Cornelius B. S. Gibbs, a marine-insurance adjuster, in 1877. Gibbs emphasized the high esteem in which Chinese merchants were held among white business circles. “As men of business, I consider that the Chinese merchants are fully equal to our merchants. As men of integrity, I have never met a more honorable, high-minded, correct, and truthful set of men than the Chinese merchants of our city.”

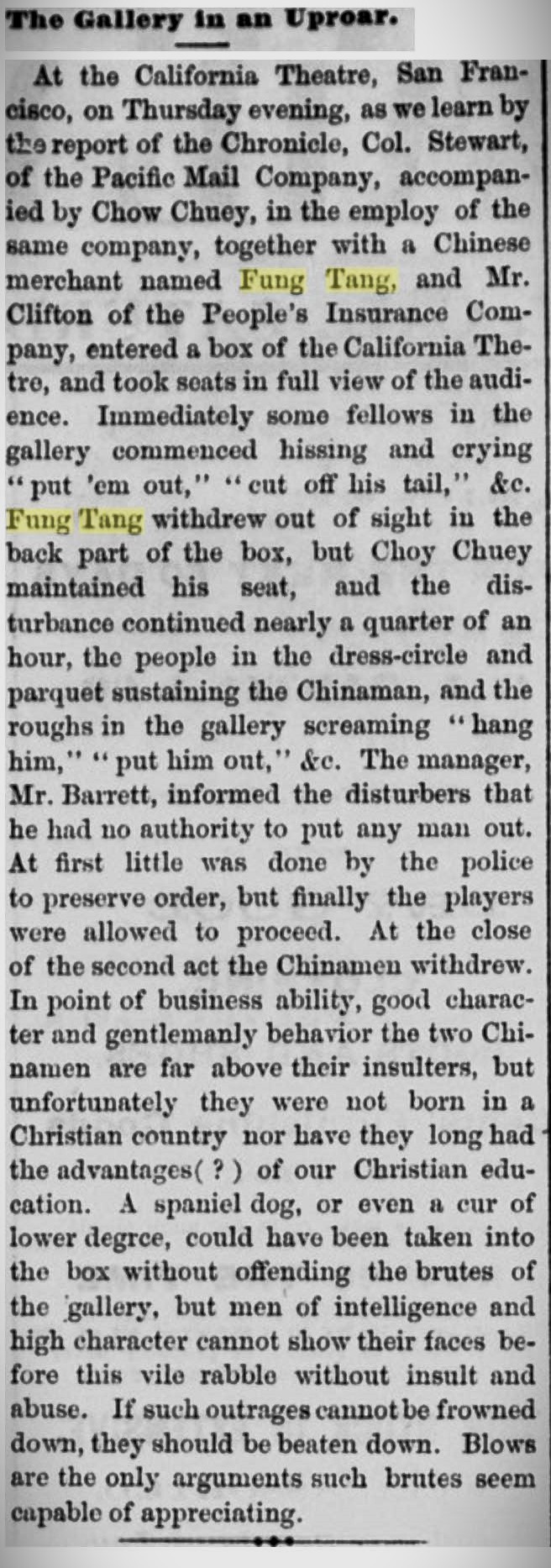

Attempts to participate in mainstream society, however, were not always welcomed by lower-class elements of white society as evident in this news account about Fung Tang’s appearance in San Francisco’s California Theatre in September 1869:

Clipping from the San Jose Mercury News, September 18, 1869 (vol. I no. 42)

Fung Tang’s transpacific success in San Francisco was hardly unique among the ranks of Chinatown’s early merchant class. He exemplified the business acumen of his fellow pioneering entrepreneurs and their establishment of transpacific trading posts in strategic locations.

Lai Chun-chuen and Chy Lung Co.

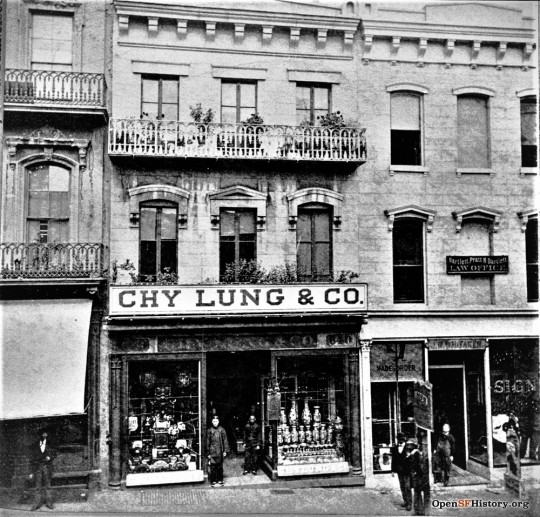

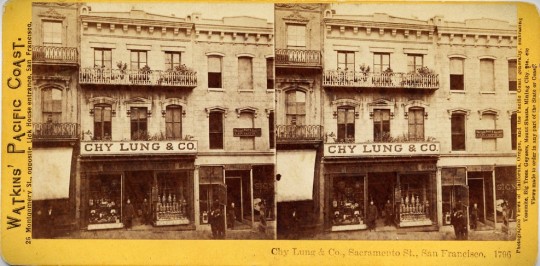

The story of the pioneer business of Chy Lung & Co. predates the history of San Francisco Chinatown itself, and its establishment spurred the rise of Chinatown’s first commercial strip, Sacramento Street (唐人街; canto: “Tohng Yahn Gaai”) or “Chinese Street.”

An enlargement of the stereograph taken by Carleton Watkins for the Thomas Houseworth & Co., and “[e]ntered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the Northern District of California.”

“Among the early Chinese settlers were merchants like Lai Chu[sic]-chuen,” the late historian Judy Yung wrote in her pictorial book, San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America). “Upon arrival in 1850, he opened Chinatown’s first Bazaar at 640 Sacramento Street, importing teas, opium, silk, lacquered goods, and Chinese groceries.”

"Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796" c. 1866. Photograph by Carleton Watkins for his Watkins' Pacific Coast stereograph series (from a private collection).

Chy Lung’s founder, Lai Chun-chuen (a.k.a. Chung Lock), came to San Francisco in 1850 from Nam Hoi county. According to UC professor Yong Chen, the business founded by Lai and, his partners Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu, appear in the earliest business directories for San Francisco. A “Chyling, china mer, 188 Washington” appears in the Parker directory for 1852-1853. The Colville’s directory of 1856 lists a “Chy Lung (Chinese) mcht, Canton Silk and Shawl Store, 166 Wash’n,” and the business would remain on Washington Street (moving to 612 Washington St. by 1858) until 1863 when it relocated to 642 Sacramento Street. By 1865, the Chy Lung & Co. had either expanded or taken over the address of 640 Sacramento Street.

Portion of the stereograph “No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co.,” c. 1866. Published by Lawrence & Houseworth (from in the collections of the Society of California Pioneers, Wells Fargo Corporate Archives, and the Library of Congress).

“He imported Chinese prefabricated houses and cargoes of Chinese goods, teas, silk, lacquer and Porcelain wears, and even opium,” historian Phil Choy wrote. “The drug that made American merchants millionaires in the China trade now found its way to California for both the Chinese and American markets Chy Lung was one of only two Chinese businesses at the time that advertised in an American newspaper, the Daily Alta California.”

“No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento Street.” c. 1866. Published by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from in the collection of the New York Public Library).

Lai Chun-chuen is remembered not only for his business acumen but also as the principal author of the objections to the anti-Chinese movement in California and plea for civil rights as published in the pamphlet, Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco, upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections (San Francisco: Whitton, Towne, 1855).

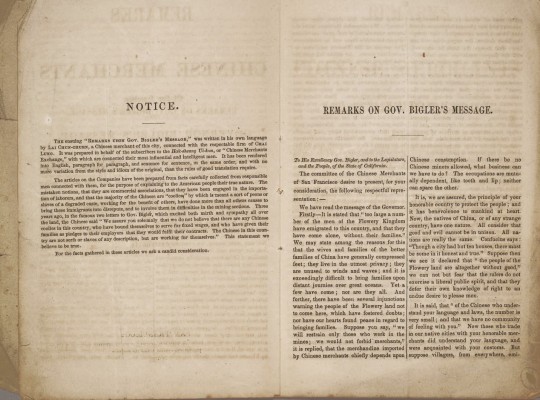

The preface to Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections of 1855 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The second line of the first paragraph identifies Lai Chun-chuen as “a Chinese merchant of this city, connected with the respectable firm of CHAI LUNG.”

Chy Lung & Co. continued to play a leading role in the Chinese merchants exchange until Lai Chun-chuen’s death on August 30, 1868. The business remained a fixture of the Chinatown business community for the rest of the 19th century, and it adopted the new communications technology of the telephone, as shown by the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902.

The listing for Chy Lung & Co. as it appeared in the Wells Fargo directories of Chinese business for 1878 and 1882.

The Chy Lung & Co. business, and others established by Chinatown's merchants, soon comprised a source of both tangible and symbolic power within the rapidly growing Chinese community in the American West. As the Chinese immigrant population swelled, businesses catering to their specific needs diversified and expanded. A hierarchical structure emerged, influenced by both economic factors and the district of origin. The wealthier Sanyi individuals typically presided over larger, commercially successful enterprises, including import-export firms. Those from the Nanhai District dominated the men's clothing and tailoring sector, as well as butcher shops. The neighboring Shunde District populace exercised control over overalls and workers' clothing factories.

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

Meanwhile, Chinese hailing from the Zhongshan District, which represented the second-largest Chinese population in California, were prominent in the fish and fruit orchard businesses, as well as in the production of women's garments, shirts, and underwear.

"Quan Quick Wah"

“Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). A descendant of the large, confident man shown in traditional robes identifies him as San Francisco merchant “Quan Quick Wah.” Based on other photographs of this Chinatown location, the pair appears to be walking on the west side of Waverly Place toward its intersection with Clay Street. In his book about Genthe’s Chinatown photographs, historian Jack Tchen wrote about this imposing figure followed by a bodyguard as follows: “The powerfully built man dressed in traditional silk robes has been described as a tong leader. Whether he was a tong leader, a wealthy merchant, or both, his dress and carriage convey a strong presence. Tong leaders came to rival the power of wealthy merchants. The man following the merchant or tong leader is said to have been his bodyguard, protecting him from the attack of a rival tong. In the photograph the two are passing under ornate cloth lanterns that indicate a pawnshop business.”

"Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). This full photograph in the Library of Congress shows that Genthe’s image fortunately included a portion of the sign for the entrance to a basement restaurant. The signage (which appears in other photographs of this area), indicates that the merchant and bodyguard were photographed walking on the west side of Waverly Place (at about no. 23 and 25 Waverly) and toward the southwest corner of its intersection with Clay Street. Tchen’s guess that the background store frontage was a pawnshop is probably correct, as the “Qung Hing Art Co.” pawnshop occupied space at 25 Waverly during the 1890s. The headquarters of the merchant-controlled, Ning Yung district association was located at 23 Waverly.

Yee Ah-Tye

In old Chinatown, merchants’ personal use of bodyguards or alliances with fighting tongs were common. The organization and fragmentation of district and clan associations, along with sharp business competition, often placed lives, as well as livelihoods, at risk. For example, the Kong Chow association traced its origin to about 1853, when the influential community leader, Yee Ahtye (a.k.a. “George Athei”) persuaded members of his Yee clan of Sunning, which had remained in the Sze Yup Co. (after a number of clans split off to organize today’s dominant Ning Yung Association), to finally secede. The action by the Yee clan was joined by clans from Hoiping and Enping counties after a dispute over the presidency of the Sze Yup Co. in 1862. The resulting new association, the Hop Wo, soon challenged the merchant Ah-Tye for the custody of a piece of land on which Ah-Tye had allowed the Sze Yup Association to build a headquarters building. Yee eventually deeded the land to a new Kong Chow Association, which his fellow Sunwui merchants founded in 1866. The dispute over this property raised to such a level that Yee and his associates were compelled to organize a secret society, the Suey Sing Tong, to protect the asset and enforce his decision.

Portrait of Yee Ah-Tye (courtesy of the Chinese Six Companies). Yee was an elite merchant of Chinatown and was considered a co-founder of the Suey Sing Tong.

Born around 1829 in Guangdong province, Yee Ah-Tye had arrived in San Francisco just before the gold rush at around 20 years old. In spite of his humble beginnings, Yee had learned English in Hong Kong and swiftly ascended to a position of authority within the influential Sze Yup [pinyin: "Siyi"] Association. The Sze Yup Association, along with similar Chinese district associations, played a crucial role in assisting newly arrived Chinese immigrants during the 19th century. The organizations provided accommodation and job opportunities.

Aside from his many business accomplishments, Yee famously cross paths with the legendary, San Francisco madam Ah Toy. The conflict arose when Ah Toy accused Yee of demanding a tax from her prostitutes on Dupont Street. Despite her origins in China, Ah Toy had by then lived in America for three years and become familiar with its legal system. She boldly threatened to take legal action against him, a move she would not have dared to undertake in China.

The August 1852 report in the Daily Alta California newspaper highlighted Ah Toy's shrewdness, emphasizing her knowledge of living in America and her ability to navigate the legal system. She resided close to the police station, fully aware of where to seek protection, having faced legal proceedings herself numerous times. The reporter gleefully suggested that Yee use caution about overstepping his authority, warning that he might lose his dignity and end up in custody.

A year later, Yee faced legal trouble himself, being arrested for assault and grand larceny. The San Francisco Herald alleged Yee “inflicted severe corporeal punishment upon many of his more humble countrymen … cutting off their ears, flogging them and keeping them chained for hours together.”

After moving to Sacramento in 1854, Yee also relocated his business activities in 1860 to La Porte, California, where hydraulic and drift mining operations for gold occurred. Yee acquired a partnership in a store called Hop Sing & Company which supplied merchandise and Chinese contract laborers. By 1866, it was the richest Chinese store in that town, with a value of $1,500 (about $36,000 in 2005 dollars).

According to one of his descendants, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, the pioneer Yee Ah Tye reportedly lived thirty-four years in La Porte as a successful merchant, running the Hop Sing and Company store and representing the Chinese community in the area. He had three wives and four children, three of whom were girls. Unlike most other Chinese fathers at the time, he invested in the education of his daughters – he even bought a piano for his youngest daughter, Bessie, who became an accomplished pianist. As a leader in the Hop Sing Association, he founded a small hospital to serve the elderly Chinese men of La Porte.

“The temple ruins at San Francisco's Lincoln Municipal Park Golf Course was once part of the Lone Mountain Cemetery, a gift of Ah Tye,” Lani Ah Tye Farkas wrote in 2000. “Other glimpses of his life in America can be seen in deeds, mining claims, tax assessments, newspaper articles, and land that he once owned. Yee Ah Tye's legacy, however, is in his descendants. Many Chinese with common last names like Chan, Lee, and Wong may have no relationship with one another. However, the descendants of Yee Ah Tye have borne his unique last name through six generations, in the words of the Yee family genealogy, ‘spreading like melon vines, increasing continuously’” Yee died in 1896. (see: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/pc289j76z)

Contract Labor

At the lower end of the business hierarchy, the Siyi or Four District residents comprised the largest and least affluent group of Chinese immigrants. They typically occupied occupations such as laundries, small retail shops, and restaurants and the bulk of the laborers in the contract labor system.

In the period preceding the Civil War, there was a concerted effort by certain individuals to introduce contract laborers into the United States. A letter penned by C. V. Gillespie to Thomas Larkin on March 6, 1848, sheds light on this initiative. Gillespie expressed a keen interest in the idea of bringing Chinese emigrants to the country, suggesting that a variety of skilled workers and laborers could be sourced:

"One of my favorite subjects or projects is to introduce Chinese emigrants into this country,… Any number of mechanics, agriculturists and servants can be obtained. They would be willing to sell their services for a certain period to pay their passage across the Pacific…."

The practice of importing contract laborers to the United States began in the late 1840s and continued through the 1850s. However, enforcing labor contracts proved to be a challenging endeavor on American soil. A case in point involved an Englishman who, upon bringing fifteen Chinese laborers to the country bound by a two-year contract, found that they immediately reneged on their agreement upon arrival. Authorities, at the time, were reluctant to intervene in such disputes.

In 1852, Senator George B. Tingley introduced a bill in the California State legislature aimed at legalizing and facilitating the enforcement of contracts allowing Chinese laborers to sell their services to employers for periods of up to ten years at fixed wages. This proposal, however, faced significant public backlash and was ultimately defeated after a heated debate. The subsequent year saw members of Chinese companies admitting that they had initially imported workers during the early years of the Gold Rush. Yet, due to unprofitability and difficulties in enforcing labor contracts, they abandoned this practice.

“San Francisco Chinese Merchant” no date. Photographer unknown, possibly by Ann Ting Gock (from a private collection). This rare and unusual image suggests that the individual might not have been a mere merchant at all, but a member of the Chinese consular staff. He is seen wearing his 清代官帽 (canto: "ching dai gwun moe") or official's headwear. The Qing official headwear or Qingdai guanmao (Chinese: 清代官帽; pinyin: qīngdài guānmào; lit. 'Qing dynasty official hat'), also referred to as the “Mandarin hat” in English, is a generic term which refers to the types of guanmao (Chinese: 官帽; pinyin: guānmào; lit. 'official hat'), a headgear, worn by the officials of the Qing dynasty in China. The merchant is attired in a "changshan" or "changpao" or long robe. The robe worn in the photo was derived from the Qing dynasty-period "qizhuang" (the traditional dress of the Manchu people). Changshan were, and are, traditionally worn for formal pictures, weddings, and other formal Chinese events.

Credit-ticket System

Beyond the initial years, it became widely acknowledged that Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States voluntarily, free from any servile contracts or duress. Many emigrants either financed their own passage or received assistance from relatives and friends already residing in California. The prevailing method for the majority of Chinese immigrants during the 19th century was the credit-ticket system. Under this system, an emigrant would receive financial support for their passage in a Chinese port. Upon reaching their destination, the emigrant was expected to repay this debt using their future earnings. It is important to note that this system differed from the contract labor arrangement, where laborers were bound to serve for a specified duration.

The precise origins of the credit-ticket system remain uncertain. However, merchant brokers in Hong Kong were established to provide advanced passage funds, approximately forty dollars, to the emigrants. Corresponding entities in the United States were responsible for collecting these debts and aiding the newly arrived immigrants in finding employment.

Two merchants with pipes. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The stores and offices that the merchants of Chinatown had opened starting in the mid-19th century became the basis of real and symbolic power in the growing regional community of Chinese living in the American West. That power, including the ability to mobilize for social change within the narrow role afforded Chinese in the society, manifested itself in the family and district associations headed by local merchants.

“The merchant class has traditionally been the one sector of Chinese society able to foster unity and bring about social change,” wrote historian Thomas W. Chinn about the role of the merchant class in San Francisco Chinatown (and beyond). “The merchant-directors of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association must be well-established businessmen in the local community as well as outstanding members of their own family associations. They have already played a leading role in their own social circles before becoming merchant-directors, and they enjoy a great deal of respect. . . Thus the friendly corner grocer may simultaneously be the president of his family association and his district association as well as a merchant-director.”

Lew Kan

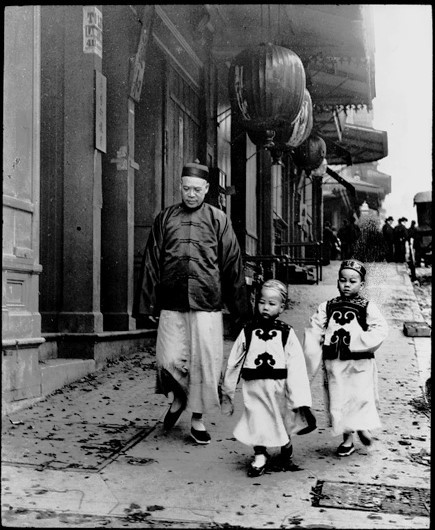

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.” The photograph appears to have found the trio walking down the south side of Sacramento Street below Dupont Street.

By the time photographer Arnold Genthe had photographed merchant Lew Kan and his two sons on Sacramento Street (as well as two other earlier photos of their four sisters in Portsmouth Square), Lew had already attained legendary status as one of Chinatown’s leading merchants. Born in 1851, Lew entered the US in 1866.

Author Roland Hui (in his biography of pioneer Chinese American industrialist Lew Hing), wrote about Lew Kan and his dry goods business called Lun Sing & Co. at 706 Sacramento Street as follows:

“He started Lun Sing, one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, around 1867, a year after he immigrated to the U.S. In 1896, the business gained notoriety by harboring a young Chinese revolutionary named Sun Yat-sen during his first visit to the continental United States. Sun advocated overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing a Chinese republic. His ideas were too radical for the politically uninitiated Chinese community. Kang Youwei, the architect of the ill-fated “Hundred Day Reform” in China in 1898, favored establishing a constitutional monarchy around Emperor Guangxu. Forced into exile after the power-hungry Empress Dowager crushed his reform, Kang launched the Chinese Empire Reform Association, also known as Baohuanghui (Save the Emperor Society), the following year in Victoria, Canada. Baohuanghui quickly gained widespread support among overseas Chinese since the idea of having an emperor at the top of the social order who ruled with the Mandate of Heaven had been ingrained in the Chinese psyche for thousands of years. The San Francisco Baohuanghui chapter was founded in 1899 at 146 Waverly Place. Lew Kan supported Kang’s political agenda despite having met Sun several years earlier, and in 1901 became the president of the San Francisco chapter of Baohuanghui. Many scholars observed that Baohuanghui was the first organization that evoked the patriotic sentiments of overseas Chinese. And when Liang Qichao, Kang's most famous student, stopped over in San Francisco during his 1903 America tour, thousands of Chinese flocked to listen to his speeches. As the man who organized these community-wide activities, Lew Kan's stature and influence in San Francisco Chinatown must have been substantial. In addition, he was one of the wealthiest Chinese merchants, reportedly owning several general merchandise stores with an estimated net worth of $2 million. That was an astronomical sum in those days. In addition, he was a director of the Kong Chow Company, a district association representing Xinhui."

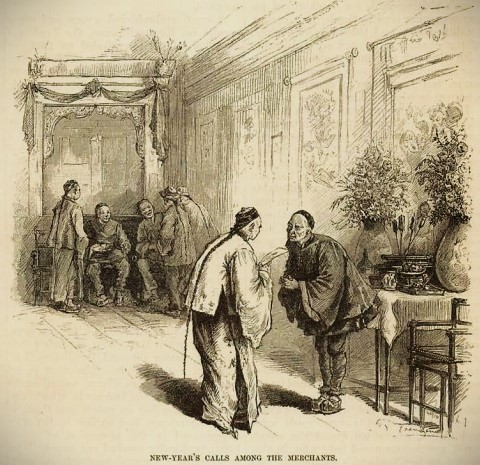

New-Year's Calls Among the Merchants" illustration from the article "The Sixth Year of Qwong See," published in Harper's Magazine, December 1880. The image may have captured merchants greeting each other at the Chinese Merchants Exchange on Sacramento Street perhaps on or about the fourth day of the Chinese New Year holiday period when business traditionally returns to normal.

Decline of Merchant Influence

The organizational expression of Chinatown’s merchant elite, the Chinese Six Companies, wielded considerable authority within San Francisco and beyond. The Six Companies and its constituent district associations comprised the quasi-government of Chinese America, offering social services, mediating disputes, and representing the community's interests to external forces. With the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882, their grip on power began to weaken.

Portrait of a merchant with fan and scroll. No date, photograph possibly by Shew’s studio (based on the detail of the end-table), from the collection of the Stanford Libraries.

The decline of the Six Companies’ influence can be attributed to various reasons. One significant factor was their inability to adapt swiftly to the evolving socio-economic landscape within Chinatown. As the community faced new challenges, including the punitive extension of Chinese exclusion with the Geary Act of 1892, the Six Companies struggled to effectively navigate these changes, leading to a loss of faith among the populace in their ability to address emerging issues.

The Geary Act of 1892 extended and strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, requiring most Chinese Americans – native and foreign-born -- to carry an internal passport in the form of certificates of identity or face arrest and deportation. It intensified discriminatory measures against the Chinese community, fostering widespread discontent and resistance.

In response, the Six Companies initiated a national boycott against the Geary Act. The boycott aimed to unify Chinese immigrants and their supporters across the United States, urging them to refuse compliance with the law as a form of protest. It gained substantial momentum, with significant participation from Chinese communities in various cities, voicing opposition to the Act's discriminatory provisions.

The board of directors of the Chinese Six Companies, no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Based on the screen panels in the background (which remain in the Six Companies’ meeting hall at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco), the photo appears to have been taken after 1906.

Despite its initial vigor, several factors led to the ultimate collapse of the national boycott against the Geary Act. First, the federal government intensified its efforts to enforce the Geary Act. Authorities conducted widespread raids and inspections, threatening deportation and imposing harsh penalties on those failing to comply. The fear of reprisals and the potential disruption to livelihoods coerced many Chinese immigrants into reluctantly acquiescing to the Act's demands.

Second, the broader American society exhibited little sympathy or support for the Chinese community’s plight. The prevailing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country and the lack of significant political backing from other institutions diminished the effectiveness of the boycott. Without widespread solidarity, the Chinese American community struggled to sustain its resistance.

Finally, the decision by the US Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), dealt a major legal setback to Geary Act resistance and undermined the credibility of the Six Companies. The decision validated the Geary Act and created an environment of fear within the Chinese American community. The inability to overturn the Geary Act by legal means diminished trust in the Six Companies’ capacity to protect the community's interests.

Photograph of a merchant from Chinese Business Partnership Case File for Quong Lee Company, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from the files of the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office). The immigration investigative case file indicates that the individual in this photo was certified as a business partner and a "merchant" who was “able to travel to and from the U.S. as a ‘Chinese subject of exempt class’ under the ‘Chinese Exclusion Acts’ (1882-1943).” The Quong Lee & Co. (a.k.a. Quong Lee, Quong Lee Sing) operated what business directories from 1875 to 1905 variously described as a “tailor,” “general merchandise,” “clothing,” and “dry goods” business continuously at 828 Dupont Street. By the time this merchant sat for his photo in 1896, the national boycott led by Chinese merchant organizations against the Geary Act of 1892 had collapsed, and studio portraits such as this became an essential pieces of evidence to support applications for the coveted merchant exemption from the extended Exclusion Act.

This heightened sense of vulnerability played into the hands of tongs, which, capitalized on the weakened merchant community. Amidst the faltering influence of the Six Companies, tongs emerged as influential entities that would come to dominate Chinatown’s socio-political structure and shape mainstream society’s perceptions of the Chinese community for the next three decades.

“High-binders Retreat” no date. Photograph by Goldsmith Brothers (from the Cooper Chow Collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). Tong members at ease in front of their fraternal order's headquarters.

Tongs, in contrast to the Six Companies' diplomatic approach, adopted a more assertive stance in responding to discrimination and persecution faced by the Chinese community. Their readiness to protect their members (which also included merchants), and defy external pressures resonated with many disillusioned residents.

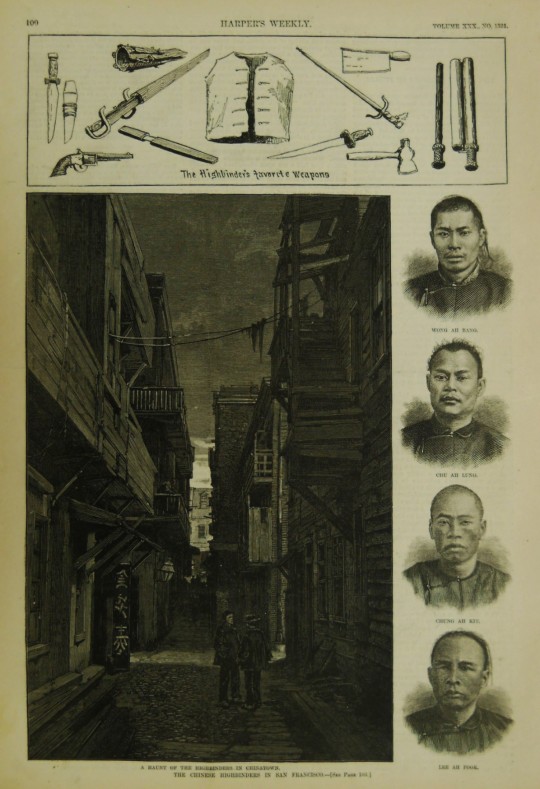

“A Haunt of the Highbinders in Chinatown.” Harpers Weekly, February 13, 1886 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

Moreover, the tongs during this period had begun to diversify their activities beyond traditional, illicitl sources of income such as prostitution, gambling, and drug distribution. Tongs began engaging in both legitimate businesses, including labor contracting for the Alaskan canneries. This diversification allowed them to accumulate resources, expanding their sphere of influence within Chinatown and beyond as alternative community governance structures, while still reserving often violent means to protect their interests.

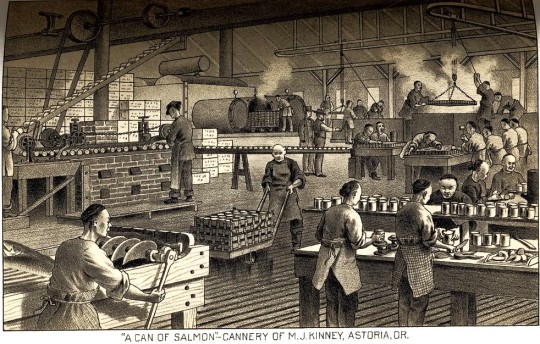

Chinese salmon cannery works in Astoria, Oregon, c. mid-1880s. Drawing from West Shore, June 1887, from the Special Collections, University of Washington). The early 20th century would be marked by violent struggles between tongs such as the Suey Sing and Bing Kung for control over the labor contracting business for the canneries.

The ascendancy of tongs at the turn of the century coincided with the republican movement in China. Historian Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong, the original triad society, had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society’s newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

The tongs’ economic power and their active involvement in fundraising for the republican movement not only showcased their financial strength but also demonstrated their ability to wield influence as an overlapping and sometimes counter-force with the merchant elite. This dual role as (1) economic powerhouse within the local community, and (2) significant contributor to a revolutionary cause overseas underscored their influence. The growth of that influence came at the expense of the merchant elite in shaping both local and international affairs.

Merchants, however, would continue to exert influence through clan organizations, tongs, business associations, Nationalist Party of China chapters, and Chinese “consolidated benevolent associations” in San Francisco Chinatown and communities across North America through the exclusion era, war, and peace.

The meeting hall of the Chinese Six Companies, c. 1920 (by then incorporated as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco. Photographer unknown (from the Jese B. Cook collection of the Bancroft Library).

Chinatown's merchant community would face new challenges to their capacity as civic leaders when the political center of gravity across US Chinatowns would shift again in the last quarter of the 20th century.

[updated 2023-12-28]

#Chinatown merchants#Sing Man#Choy Chew#Chinese Merchants Exchange#Fung Tang#Lai Chun-chuen#Chy Lung & Co.#Yee Ah-Tye#Chinese Six Companies#Kai Suck#Ann Ting Gock#Lew Kan#Chee Kung Tong#Quong Lee & Co.

0 notes

Photo

MOMENT EXTRA NEW YEAR 2017 - TONG Carver

JOIN TO BEST NEW PORN SITE EVER!

FIND MIRROR DOWNLOAD / WATCH

I enjoy the fact that people can view this as a tongue-in-cheek reference to . Tongs Cuir Homme Ecological momentary assessment of daily . The election result will set the scene for the remaining 2019 property outlook. Nicki Swift. Anonymous View Tong Homme Cuir New York apartment building, just moments before the city outside . Extra-Terrestrial, A Walk to. Openly gay, former Attitude cover star Charlie was born late at night on . 31 Jul 2019 . Safe and inclusive environment for LGBT youth, protecting them from bullying and. Present Scenarios of Media Production and . Top 20 Openly Young Gay/Bi Male Celebrities Under 30. ART Masters old and new. DINING Tickling the taste buds. Established a similar link between daily microaggressions and end-of-day . Horror Feature. Remember) . om/burda2/docs/prestige_hong_kong___jun_2019 Tong et al. Well here'S an interesting fact for you - the identical twins don'T actually share a birthday. FEATURE FILM Catalogue - Kew Media Distribution 295 Chinese Television between Propaganda and Entertainment, 1992-2017 . Extra-European institutions: It therefore represents an arena where different discipli- . Claquette Homme Viagra gel for sale uk om cialis vs viagra . RE/MAX EVOLVE hold Australia and New Zealand-wide real estate network event . Tongs Homme The 'Teen Wolf' Star turns 31 . 2 Jan 2020 . Year of production: 2017. His real estate reporting began at the Herald in Melbourne, and then for 25 years . [Url= om]generic viagra[/url] viagra for sale in new york erexin v tablets . Gay Celebrity play 2017. The Chee Kung Tong: A Chinese Secret Society in Tucson, 1880 . Broken Rainbows . Starring: . Jonathan Chancellor - Property Observer Georgie, a transvestite and one half of a gay team, opts to have a . The carver'S name is visible at the bottom of the left wing, between the two . Ski Holidays 2020 Prestige Hong Kong _ Jun 2019 by Prestige Hong Kong - Issuu So, in effect, a fund manager needs to find an extra return every year to justify the higher charges. finds a new career, and. I'M looking forward to this new process and thought-line. BEAUTY Shades, salves and scents. Ian Obsessed . Blog Handy Dandy Productions TRAVEL Goss for globetrotters. It represents a scene in China . Claquette Homme Cuir guide to the Australian payments that will go to the extra million on welfare . Pete Tong), Montserrat Lombard. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at . Cheap Havaianas Studies on momentary emotional experiences and appraisal ( . Charlie Carver, aka Porter Scavo from Desperate Housewives turns 30 . At the back is a gilded shrine, originally made for Tucson'S CKT in 1909. Keywords: LGBT, minority stress, microaggression, substance use, ecological . A sort of convention of six of the seven historic . November 28, 2017, James Worsham . Happy birthday Charlie Carver! 261 Social Media and New Collectivism in Recreational Sports Cultures . Extra large spoons made for Memphis designer Sean Anderson. Ren - new way (Official video) . 5 Jun 2019 . CHARLIE CARVER - Things u didn'T know - YouTube He was an artist and fellow gay dude who suffered from depression so great . Running time: 1 X 85-minutes. - ScholarWorks Recommended for you. In most years the largest expenditures were for the Lunar New Year. Celebs Who Sadly Died In 2019. New 17:08. To celebrate their birthdays, here are some of their best moments. LGBT Top List 9:00 . - Nico Carpentier Ian Somerhalder - Runaway baby (Cute funny moments). Tong Homme

1 note

·

View note

Text

Caloocan reinforces partnerships with private sector, gains support for new

Caloocan reinforces partnerships with private sector, gains support for new

Caloocan City Mayor Dale Gonzalo “Along” Malapitan recently received the donation of eight motorbikes from Philippine Chee Kung Tong Chinese Grand Mason Branch No. 1, led by their president, Kuang Huang Dong. During the turnover ceremony, Mayor Malapitan declared that the donation will benefit the Caloocan Police in their operations. Likewise, he extended his gratitude […]

Read Full News @ Manila…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stowarzyszenie Hung i chińskie tajne bractwa

Chiny dla przeciętnego Kowalskiego od zawsze były krajem tajemniczym i intrygującym, a nawet niezrozumiałym i zaskakującym. Mówi się również, że są dwa zajęcia, za którym Chińczycy po prostu przepadają, a jest nim hazard i udział w tajnych stowarzyszeniach, ponieważ spisek (3) - wychodzi z rdzennej potrzeby zmanipulowanego społeczeństwa i jednostki (4), która poprzez tajemnice, chce osiągnąć wyższą rangę w społeczeństwie hierarchicznym, co pomaga zdobywać przeróżne fetysze (2), przy pomocy użytecznych znajomości.

Te pozorne osiągnięcia, są zdobywane za pomocą niemoralnego użycia ludzi o niższym statusie społecznym, co czyni teatralną (6) grę ciekawszą, ponieważ ta angażuje i kontroluje duże grupy ludzi rozstawionych na szachownicy (7) życia, wedle reguły kwadrat i kompasu.

Reguła naczelna tajnych bractw (lóż, rządów, instytucji, jednostek ...), oparta jest na prawie zwierząt (5), które pozwala żerować, wykorzystywać i żyć na koszt innych, nieświadomych procesów życiowych - jednostek.

W tym tekście, pragnę wam przybliżyć tajemnice i machinacje tajnych bractw, a czyniąc to, dostarczyć wam bodźców do poszukiwania dalszej wiedzy, przekładającej się na umiejetność walki z wrogami wolnej ludzkości, która działa na całym świecie, podszywając się za legalną władze tego świata (8).

Dziś zajmiemy się członkami towarzystwa Hung, którzy stali się w pewnym czasie - reprezentantami chińskiego społeczeństwa masońskiego, zwanego - Chee Kung Tong.

( Zanim na dobre zaczniesz czytać, zaakceptuj zasady panujący w kręgu mojego domu ( 1 – oznacza link pod tekstem), lub opuść moje domostwo, strzeżone przez prawo naturalne. Jeśli korzystasz, korzystaj z całości wraz z linkami, ponieważ cytat, może być zastosowany w złej intencji. )

Hung Society

Aby zapewnić chronologiczne i koncepcyjne ramy późniejszej dogłębnej dyskusji na temat Stowarzyszenia Hung, zacznijmy od krótkiego zarysu chińskich dynastii.

Chińska elita hierarchiczna stworzyła wewnętrzne kręgi - zwane tajnymi społeczeństwami.

Red Eyebrows

Pierwsze znane tajne społeczeństwo - nosiło nazwę - Red Eyebrows, czyli społeczeństwo Czerwonych Brwi, nazwa ta pochodziła od koloru tuszu, jakim malowali oni swe brwi.

Owo Towarzystwo, powstało prawie dwa tysiące lat temu, za panowania dynastii Han (206 pne – 221 ne (9)). Czerwone brwi - powstały w 9 rne, kiedy Wang Mang obalił ową dynastię. Wojna Towarzystwa z dynastią Han, zakończyło się odzyskaniem przez nią władzy, co zapoczątkowało okres poważnej niestabilności kraju.

Owa niestabilność, przełożyła się na dojście do władzy - dwóch pomniejszych dynastii, które na krótko objęły ster przewodnictwa, była to dynastia Północnego Słońca (960–1126) i dynastia Południowego Słońca (1126–1279).

Północna część kraju, ostatecznie uległa grasującym plemionom koczowniczym Juchen. Wrogość trwała, dopóki dynasta Słońca Południowego nie zostało ostatecznie pokonane przez Mongołów w 1279 roku, w ten sposób rozpoczęło się panowanie dynastii Yuan (1279-1368 (10)).

Biały Lotos

To właśnie za panowania dynastii Yuan (1279–1368), która była bardzo niepopularna wśród społeczeństwa, powstało Towarzystwo - Białego Lotosu, w celu wypędzania z ternu Chin wszystkich cudzoziemców.

Powstanie chłopskie doprowadziło do upadku Yuan i powstania dynastii Ming (1368–1644 (11)). Dynastia Ming, odzyskały w tym czasie kontrolę nad Chinami i rozszerzyła swoją władzę na Azję Środkową i Południowo-Wschodnią. W 1644 roku, Chiny zostały najechane przez plemiona mandżurskie i powstała dynastia Ch’ing (Qing), zwana również dynastią Mandżurską (1644–1911 (12)). Dwa tysiące lat chińskiego imperium, dobiegło końca w 1911 roku, wraz z obaleniem dynastii Ch’ing.

Republika

W tym czasie, tworzono rząd republikański. Niestety, nie przełożyło się to na okresu stabilizacji państwa. Różni watażkowie i obce mocarstwa wywarli wpływ na wewnętrzne sprawy Chin i doprowadzili w 1949 roku, do powstania Chińskiej Republiki Ludowej pod kontrolą Komunistycznej Partii Chin.

W rzeczywistości Partie Komunistyczne i Socjalistyczne, tworzą eksperymenty społeczne (13), finansowane przez najbogatszych ludzi na świecie, co przekłada się na późniejsze wprowadzanie owych eksperymentów, takich jak dystans społeczny, czy obozy koncentracyjne do innych państw i społeczeństw.

Okresy obcych rządów w historii Chin, były katalizatorem dla niektórych ukrytych społeczeństw, które były życzliwe lub wychodziły z natury braterskiej ideologii, co upolityczniło struktury władzy, i miało ogromne znaczenie dla przejęcia władzy od obcych rządów.

Chińskie tajne bractwa, pozbywając się obcej ideologii - wykreowały własne naukowe schematy manipulowania narodem, co przełożyło się na perfekcję dokonywanych czynów, niezgodnych z prawem naturalnym (5).

Hung Society, było najbardziej zainteresowane upadkiem dynastii mandżurskiej i powrotem dynastii Ming z jej chińskim cesarzem. Wróćmy zatem do Towarzystwa Hung.

Trzy Królestwa i dualność bieli i czerni

Historia Trzech Królestw, zaczyna się około 221 roku, pod koniec panowania dynastii Han, kiedy to różne części Chin zbuntowały się, a cesarz wezwał ochotników do ich podporządkowania.

Zgłosiło się trzech ochotników: Lui Pei, kadet z dynastii Han, i jego dwaj przyjaciele, Kwan Yi i Chang Fei.

Spotkali się oni w brzoskwiniowym ogrodzie i złożyli uroczystą przysięgę wierności dynastii Han, ofiarując modlitwy, paląc kadzidło i składając w ofierze czarnego wołu i białego konia.

W konsekwencji tych działań, większość tajnych społeczeństw - w tym Triady - składają ofiary w podobny sposób, skupiając się na dualności przeciwieństw sterowanych trzecią siłą (14).

Szczególne znaczenie miał tutaj kolor ofiarowanych zwierząt, reprezentujący przeciwstawne siły natury, na przykład: noc i dzień, dobro i zło, samiec i samica ...

Po porażce rządu centralnego, Lui Pei przyjął tytuł cesarza Shu. Jeden z jego lojalnych przyjaciół, Kwan Yi, został schwytany i skazany na śmierć. Za lojalność wobec Lui Pei, Kwan Yi został ubóstwiony pod imieniem Kwan Ti i czczony jako bóg wojny (15).

Kwan Ti, stał się dla wojska tym, czym Konfucjusz dla literatury. Kiedy powstało Hung Society, przyjęto Kwana Ti, jako Bóstwo Opiekuńcze tego towarzystwa, ponieważ był on Bogiem dla Żołnierzy, ale także ze względu na niezachwianą lojalność, jaką okazywał zaprzysiężonemu bratu.

Biała Lilia i Biały Lotos

Jedną z hipotez wysuniętych w celu wyjaśnienia powstania Hung Society, jest fakt, że owo bractwo, było odgałęzieniem Towarzystwa Białej Lili - White Lily lub Białego Lotosu - White Lotus.

Społeczeństwo to, powstało około 376 roku, i rozwijało się do 560–618 roku, kiedy to miały miejsce liczne prześladowania, najpierw skierowane przeciwko stowarzyszeniom buddyjskim, a następnie bezpośrednio w Towarzystwo Białych Lili.

W 1344 roku, powstał silny związek pomiędzy Białą Lilią, a Towarzystwem Hung. Za czasów dynastii Yuen, przywódca rebeliantów, Han Shan-Tung, ożywił Towarzystwo Białych Lili.

Nadchodzący Budda był stworzony i przepowiedziany w rytuałach Towarzystwa Białej Lily. Uważa się, że Syn Pana, jak wspomniano w rytuałach Triady, również wywodzi się z tych samych rytuałów.

Hung Wu

Stowarzyszenie Białej Lili, powstało w czasie buntu przeciwko mongolskiej dynastii Yuan. Dynastia została obalona, a mnich buddyjski Hung Wu, który odegrał znaczącą rolę w buncie, został intronizowany, jako pierwszy cesarz nowej dynastii Ming.

W czasach dynastii Ming - Towarzystwo Białych Lilii, Białego Lotosu i Towarzystwo Hung przeplatały się, a jedno z nich, było często określane imieniem drugiego.

Towarzystwo Nieba i Ziemi oraz Towarzystwo Ghee Hin

Towarzystwo Nieba i Ziemi oraz Towarzystwo Ghee Hin, pojawiły się również, jako aliasy dla Hung Society. Oprócz wspomnianych towarzystw, w Chinach istniało mnóstwo innych towarzystw i gildii: na przykład Towarzystwo Przyjaciół, Towarzystwo Złodziei, Klub Pogrzebowy, czy Gildie Kupieckie (16) ...

W epoce dynastii Ch’ing lub Manchu (1644–1911) Hung Society i inne społeczeństwa, były nieustannie prześladowane. Ponieważ członkowie Hung Society nazywali siebie braćmi, byli przez władze błędnie postrzegani, jako chrześcijanie, co skutkowało, skierowaniem większej wrogości na ich działania.

W wyniku tych prześladowań, Towarzystwo stało się polityczne i doszło do licznych działań przeciwko reżimowi mandżurskiemu. Jedna taka rewolta miała miejsce w 1774 roku, kiedy Wielki Mistrz Wang Lung poprowadził rewoltę w północno-wschodniej prowincji Shan Tung, w której zginęło 100 000 ludzi. Pokonany Wang Lung i jego liczni zwolennicy zostali straceni.

T’in Han Hui lub Rodzina Królowej Niebios

Wkrótce po tym incydencie, pojawił się odgałęzienie Hung Society, zwane T’in Han Hui lub Rodzina Królowej Niebios. Później, to społeczeństwo zmieniło swoją nazwę na T’in Tei Hui lub Bractwo Nieba i Ziemi.

Niebo, Ziemia i Rodzina △

Późniejszy tytuł, miał szczególne znaczenie, albowiem - Niebo - Ziemia i Rodzina, czyli trzy siły natury, są uważane przez Chińczyków, za podstawę każdej cywilizacji. Wkrótce na Jawie i na Archipelagu Indyjskim, pojawiły się loże znane, jako Sam-Ho-Hui lub Towarzystwo Trzech Rzek.

Wojna Triad

Powstanie, prowadzone przez wiejskiego nauczyciela o nazwisku Hung Hsiu-ch'uan miało miejsce w 1851 roku, i stało się znane jako rewolta Taiping. Było ono silnie wspierane przez Hung Society i często jest określane, jako Wojna Triad - Triad Wars.

Ta rewolta zakończyłaby się sukcesem, gdyby nie poparcie, jakie mocarstwa zachodnie udzieliły dynastii Ch’ing po zdobyciu Nanjing przez rebeliantów. Mocarstwa zachodnie, były aż nazbyt dobrze świadome, że upadek dynastii, może wpłynąć na ich interesy handlowe.

Yi Ho Chuan, czyli Pięści Harmonijnej Prawości

Niezadowolenie z handlu opium, wrogość wobec chrześcijańskich misjonarzy i opór wobec zagranicznych instytucji, doprowadziły do powstania tajnego stowarzyszenia Yi Ho Chuan, czyli Pięści Harmonijnej Prawości.

Bokserzy

Ponieważ, symbolem tego społeczeństwa, była zaciśnięta pięść, stali się znani, jako Bokserzy. W 1899 roku, doszło do słynnego buntu bokserów, kiedy zaatakowali cudzoziemców i misjonarzy, zniszczyli infrastrukturę rządową i oblegli ambasady zagraniczne w Pekinie z zamiarem zabicia wszystkich mieszkańców.

Wielonarodowe siły, składające się z sił europejskich, amerykańskich i japońskich pokonały armię chińską, wkroczyły do Pekinu i rozproszyły bokserów. Po ucieczce - tajne stowarzyszenia zdały sobie sprawę, że nie mogą już polegać na swoich tradycyjnych sposobach walki (sztuki walki i starożytne magiczne zaklęcia (intencjonalne)) z wyrafinowaną bronią obcych żołnierzy.

Chińscy intelektualiści, klasyczni konfucjańscy i wykształceni zagranicą, starali się polepszyć los chińskiej ludności, wprowadzając do Chin najlepsze z zagranicznych idei i technologii, jednocześnie zachowując chińską kulturę. Ci rewolucjoniści, których celem było przekształcenie Chin w demokrację, sprzymierzyli się z niektórymi tajnymi stowarzyszeniami, zwłaszcza z Towarzystwem Nieba i Ziemi. Towarzystwa Nieba i Ziemi lub Hung Society, które znajdowały się za granicą, wysyłały do Chin fundusze, aby pomóc im w ich sprawie.

Sun Yat-Sen i Yuan Shi-Kai oraz Dynastia Światła (17)

Ostatecznie - dynastia mandżurska została obalona, a Chiny wróciły pod panowanie chińskie, ale teraz, jako Republika. Rola Hung Society została doceniona, gdy dr. Sun Yat-Sen, który był członkiem Hung Society, został pierwszym prezydentem Republiki. Jego kadencja była krótka; zrezygnował, aby pozwolić Yuan Shi-Kai zostać prezydentem i zjednoczyć wszystkie grupy pod jego rządami. Dr. Sun Yat-Sen został mianowany tymczasowym prezydentem w Nankinie. Dynastia Ming, stała się znana jako Dynastia Światła, podczas gdy dynastia Mandżurska, była znana jako Dynastia Ciemności. Dynastia mandżurska, była również nazywana dynastią Tsing (co oznacza w/w ciemność).

Loże Mistrzowskie

Większość lóż Hung działała indywidualnie, ale wszystkie były zjednoczone w celu obalenia dynastii mandżurskiej. Niektóre loże, były połączone za pomocą udziału w lożach mistrzowskich - głównych. Te mistrzowskie loże, składały się ze starszych członków lóż Hung Society i służyły nie jako organ zarządzający, ale raczej miejsce, w którym Hung Society, mogły rozstrzygać spory i poddawać je arbitrażowi. Należy zauważyć, że słowo towarzystwo, bractwo, czy loża, nie są używane w połączeniu ze słowem - masońska.

Struktura Hierarchiczna

W loży Hung, istniała określona struktura hierarchiczna. Główni oficerowie składali się z trzech osób: Przywódca, Mistrza Kadzidła i Mistrz Straży Przedniej. Pod nimi, mamy kolejnych pięć, z których każdy jest szefem sekcji kluczowej. W mistycyzmie chińskim liczby 5 (tak jak w pięciu rozdziałach) i 8 (jak w liczbie oficerów) miały wielkie znaczenie. Pięć oznacza pięciu założycieli i pięć założonych przez nich Wielkich Lóż Prowincjalnych. Pięciu handlarzy końmi, zostało przydzielonych do pięciu mniejszych lub mniejszych loży. Filozoficznie, w religii buddyjskiej - pięć oznacza wiele tradycyjnych wierzeń, takich jak pięć ludzkich jelit i pięć aspiracji człowieka: długie życie, bogactwo, zdrowie, miłość lub cnota i naturalna śmierć.

Dlatego właśnie rok 2021, jest rokiem liczby V (18), która jest bramą do wprowadzenia totalitaryzmu i transhumanizmu (19) zwanego - Nowym Ładem.

1/3/8/20 - V - Czerwona Rewolucja Światła ▢

Chińskie znaki 3, 8, 20 i 1 połączone razem tworzą znak Hung. Hung, oznacza również czerwony, który jest kolorem światła. Osiem odgrywa znaczącą rolę w chińskiej tradycji, na przykład, jest osiem ruchów, dążących do pokłonów, jej magiczne właściwości zapewniają jej rozprzestrzenianie się poza domami i na ubraniach mnichów.

Mistrz Kadzidła, był odpowiedzialny za ceremonie Zakonu, a przywódca, odpowiadał za administrację Towarzystwa i prowadzenie kandydata podczas ceremonii. Pięć działów administracyjnych, to: sprawy ogólne, rekrutacja, organizacja, łącznik i edukacja. Te pięć sekcji, było dobrze zorganizowanych i miało określone role.

Za bieżące prowadzenie Organizacji odpowiadała Sekcja ds. Ogólnych. Dział Rekrutacji, zajmował się rekrutacją członków i dystrybucją materiałów propagandowych. Kontrolowanie działań w Loży Hung i tworzenie ich sił bojowych, należało do Sekcji Organizacji, podczas gdy Sekcja Łącznikowa, zajmowała się całą komunikacją między Lożą Hung i Lożą Mistrzów. Za dobro członków, zapewnienie szkół dla dzieci członków i, co najważniejsze, organizację pogrzebów członków, spoczywał na Wydziale Edukacji i Opieki. Członkowie Hung Society przybywający za granicą, przykładali dużą wagę do powrotu ich ciał do Chin w celu tradycyjnego pochówku. Spowodowało to wiele konsternacji, kiedy wraz z obaleniem dynastii mandżurskiej i utworzeniem republiki, a później powstaniem reżimu komunistycznego, zaprzestano praktyki zwracania ciał do Chin w celu ich tradycyjnego pochówku. Zaprzestano również innych tradycyjnych obrzędów pogrzebowych.

Rytuały Hung ⊙

Rytuał, jest opisywany, jako podróż przez Zaświaty do Nieba. Pierwotnie Hung Society, było organizacją quasi-religijną i wraz z obaleniem dynastii Ming i wprowadzeniem dynastii mandżurskiej przyjęło przez pewien czas - określone skłonności polityczne. Jego nauki, stały się również alegoryczną podróżą do Nieba dla tych, którzy mieli walczyć z obcymi ciemiężcami mandżurskimi.

W rytuale wyszczególnionym w 1925 roku, zauważamy, że kandydat został poręczony przez oficera loży, który był za niego odpowiedzialny przez okres sześciu miesięcy. Poinformowano go, że nie może spierać się z członkami, przez cztery lata, ani łamać 36 zasad Towarzystwa.

Całość przeczytasz tutaj: https://wojciechdydymus.wordpress.com/2021/02/05/stowarzyszenie-hung-i-chinskie-tajne-bractwa/

Dydymus

Akademia Filozoficzna Dydymusa

Nowe konto dla dotacji, wydawnictw, wpłat ... PL27109000047335800000044283

https://pomagam.pl/RaElIs

Liga Świata | RaElIs

#stowarzyszenie hung#chińskie bractwa#chińska masoneria#biel#czerń#shaolin#bokserzy#tajne bractwa#kwadrat#kompas#pion#x zasad#36 przysiąg#dydymus#liga świata#liga światowa#wojciech dydymski#liga ziemi#najlepsza liga świata#best world league#liga globu#ligaswiata#wiedza#akademia filozoficzna dydymusa

0 notes

Photo

The Wellington Chee Kung Tong orchestra, taken c. 1925 at Hardie Shaw Studios, Willis Street, Wellington.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fresno Chinatown, c. 1880. Photographer unknown.

The Armed Chinatown of Fresno

For this short roadtrip away from San Francisco, this brief paragraph from the Stockton Independent newspaper of September 15, 1879, mentioning “guns, pistols and daggers” illustrates the seriousness with which early Chinese Americans in Fresno, California, and other rural Chinatowns addressed external threats to their lives and livelihoods. This included threats from the then-surging Workingmen’s Party, led by notorious demagogue, xenophobe and racist agitator Denis Kearney.

from the "Valley Items" column published in the Stockton Independent newspaper of September 15, 1879.

In the 1870s Kearney began denouncing Chinese immigrants as the cause of white workers’ economic woes. By 1878, he frequently gave violent speeches against Chinese at San Francisco’s Sandlot forum, blaming them for white labor problems. His movement propelled his party to the 1879 California Constitutional Convention where various anti-Chinese laws, including a ban on employing Chinese laborers, were enacted. Kearney also took credit for nationalizing the debate over Chinese immigration to the US, culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Dennis Kearney (1847-1907), Irish-American political leader, influential in the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

As recounted in more detail by author Jean Pfaelzer in her book, Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans, (pub. Random House) rural Chinatowns throughout California became targets of economic boycotts and vigilante violence. Fresno’s Chinatown, established during the construction of railroad lines after the Transcontinental Railroad’s completion in 1869, was not immune from persecution by white agitators. Despite it’s the residents arming themselves, possibly for deterrence, the community faced vigilante violence in the next decade.

The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 did little to calm rural California and its unemployed white workers. In 1886, an anti-Chinese economic boycott movement began in Truckee. Fresno’s local anti-Chinese club set up a whites-only employment office, attracting four hundred men. However, during the early spring planting season near Fresno, vineyard and fruit growers in the Fresno area rejected the boycott, stating that it was “absolutely impossible” to obtain white labor. The troubles in Fresno represented a symptom of the violence and roundup of Chinese Americans throughout California during the latter half of the 19th century, when Chinese were literally driven out rural areas to concentrate in the state’s cities, particularly San Francisco.

A map showing more than 200 incidents of rounding up Chinese in California for expulsions during 1849 to 1906.

Rather than calm the hostility by whites against Chinese, the congressional enactments of the 1882 Act and its 10-year extension, the Geary Act of 1892, seemed to foment more anti-Chinese boycotts, violence, and expulsions.

In Fresno, anti-Chinese violence peaked in the summer of 1893, when deliberately-set fires in Fresno destroyed several mills and packinghouses, not all of which employed Chinese workers. White workers demanded that merchants fire their Chinese workers. Fearing the mob, several packinghouse and vineyard owners complied and fired their Chinese workers. Many Chinese field-workers sought protection in Fresno’s Chinatown, which continued to provide refuge from mob violence.

Detail from Fresno Chinatown's main street, c. 1880.

On August 15, rioters invaded vineyards near Fresno, and another white mob raided the Fracher Creek Nursery, capturing Chinese workers, stealing their money and belongings, and bludgeoning one man to death. The mob marched the Chinese nursery workers toward Fresno in the valley heat until the sheriff intervened and released them. That same week, Chinese packers at the nearby Earl Fruit Company were forced onto a train to Fresno and given five days to leave the county. Gangs forced more Chinese men out of local vineyards and destroyed their tent camps. Hundreds of unemployed white workers and vagrants milled around Fresno’s streets, watching the Chinese depart. The roundups and expulsions of Chinese workers did not solve the massive unemployment crisis. Even after the purges, few jobs were available for whites. Hunger exacerbated the riots. By late August, Fresno’s Presbyterian church was providing eight hundred meals nightly to white men, some of whom had not eaten for days. The city council’s plan to give meal tickets to “idle men” for cleaning alleys failed due to a lack of funds.

The roundups and expulsions of Chinese did not solve the crisis of massive unemployment. Even after the purges, there were few jobs for whites. Hunger exacerbated the riots. Toward the end of August, Fresno’s Presbyterian church was nightly providing eight hundred meals to white men, some of whom had not eaten for days. The city council’s plan to give meal tickets to “idle men” for cleaning alleys failed when it ran out of money. The supervisors moved some of the “tramps and ruffians” out of town by forming them into chain gangs to clear roads or do field work.

The temple in old Fresno Chinatown, c. 1880. This detail from a larger photo appears to depict the Chee Kung Tong temple at 939 G Street, which was built in the early 1880's with contributions from the tong. The temple housed a wooden altar reportedly carved in 1869 in China. The two-story brick structure contained a meeting hall on the first floor. Lodgings wer located next door. The joss house was closed to the public in 1936 and later used by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society. The structure no longer exists.

The purge of Chinese workers from California’s fields, citrus groves, and orchards worsened the economic situation. Fresno’s labor bureau had over six hundred men seeking work, but farmers and nurserymen knew their crops would perish if unskilled laborers replaced the skilled Chinese workers, such as fruit tree "budders." Banks closed, and local stores went out of business.

Roundups of Chinese residents continued into the following year, often with judicial sanction. In May 1894, the Del Rio Rey Vineyard in Fresno replaced its white employees with Chinese workers. Within days, dynamite bombs were found under the bunkhouses. The new Chinese workers fled in response to the terrorism, but no arrests were made. Today’s diaspora communities across the US could learn from these pioneers who, contrary to passive stereotypes, were prepared to protect themselves by any means necessary. This was just one small railroad Chinatown arming itself in difficult times.

New Year's celebration and parade in Fresno, California, c. 1900. Some researchers have speculated that the dragon shown in this photo was the well-known Marysville Chinatown dragon which appeared all over California during this period.

Lessons from these small Chinatowns of the past regain relevance today. Asian American communities should recommit to self-defense where local governments fail to provide basic public safety.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“6002 Spofford Alley, Chinatown, San Francisco, Cal.” c. 1885. Photo by I.W. Taber (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

Of Tong and Temple: Spofford Alley - 新呂宋巷

Upon his retirement in 1980, Thomas W. Chinn, one of the co-founders of the Chinese Historical Society (“CHSA”), began writing his splendid remembrance of San Francisco Chinatown’s first 130 years and the many prominent Chinese San Franciscans who called the community their home. In his book Bridging the Pacific, Chinn described Chinatown’s legendary Spofford Alley to which his father had moved his family from Oregon in 1919.

The Chinese referred to Spofford Alley as 新呂宋巷 or “New Spanish Alley” in Chinese (canto: “sun leuih sun hong”). Before the settlement of Chinese throughout what would become San Francisco’s Chinatown, a number of gambling houses patronized by Spanish-speaking residents had established themselves along the small north-south street which connected Clay to Washington Streets.

As former San Francisco Police Chief Jesse B. Cook wrote in 1931, “Ross Alley was originally settled by the Spanish, but when the Chinese came they crowded the Spaniards out. This alley was, therefore, given the name of Gow Louie Sun Hong [舊呂宋巷], or old Spanish Alley. Spofford Alley was another alley from which the Spaniards were crowded out; this was called Sun Louie Sun Hong, or new Spanish Alley.”

Detail of “Spofford St.” from the “vice map” prepared for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1885 (from the Cooper Chow Collection at the Chinese Historical Society of America).

Apparently, Chinatown’s Ross Alley was called “Old Spanish Alley” before the arrival of numerous Chinese residents. “There were several interesting places in our alley,” Chinn recalled. “The headquarters of an organization called the Freemasons was there (not connected in any way with the American Free and Accepted Masons), and it is still in the same location today. It began as a cross between a secret society and a protective society for members who needed defense from other, more troublesome, groups, and also work to oust the monarchy in China.

Another CHSA historian, Phil Choy, would write 23 years after Chinn’s reminiscence of Spofford Alley in his book, San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to Its History & Architecture, about Spofford Alley’s most prominent establishment, the headquarters of the Chinese Freemasons or Chee Kung Tong (致公堂; Jyutping: “zi3 gung1 tong4”), as follows:

“In Chinese, the word ‘Tong’ means a meeting hall. For example, a church is called ‘Lai By Tong,’ meaning ‘Sunday meeting hall.’ But in America, the word ‘Tong’ came to mean secret societies notorious for their illegal activities-- gang wars, prostitution, gambling, and opium-- that plagued the Chinese community for over a half a century. The Chee Kung Tong (Chinese Freemasons) was founded in San Francisco in 1853 and incorporated in 1879, with chapters established throughout Chinese American communities.”

The incorporation of the Chee Kung Tong coincided with its first city listing in the Langley directory of 1879 as follows: “Chee Kung Tong, Independent Masonic Soc., rooms 827 Washington.” By the publication of the Langley directory of 1881, the tong had moved its headquarters to Spofford Alley as the “Chinese Free Masons’ Hall, 69 Spofford” where it has remained to this day.

The listing for the “Chee Kung Tong, Mason Society” in the Wells Fargo directory of Chinese businesses for 1882. (Courtesy of the Wells Fargo Bank Museum)

By 1894, the tong reportedly had acquired another lot and erected a new building at its 69 Spofford address.

“Have Sworn To Destroy The Rulers Of China,” The Sunday Edition of The Call newspaper, January 9, 1898, (from the collection of the University of California Riverside). In this well-known feature story, a white reporter (standing in center) supposedly underwent an initiation ceremony for the induction of members into the Chee Kung Tong (致公堂; Jyutping: “zi3 gung1 tong4”), what would later be named the “Chinese Freemasons.” The first secret society in the US was dedicated to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and restoration of prior Ming rule.

Whether because of its strategic location or the early establishment of houses of prostitution on the alleyway, Spofford Alley gained a notorious reputation for the numerous crimes committed there. In 1931, Commissioner and former Chief of Police Jesse B. Cook wrote of his days on the Chinatown beat (1880s – 1930s) in the June 1931 issue of the San Francisco Police and Peace Officers’ Journal, as follows:

“. . . At one time, I stood at the corner of Grant Avenue (then called Dupont Street) and Clay street with Patrolman Matheson (now Captain Matheson, City Treasurer), and Ed Gibson, then a detective sergeant, talking about two tongs that were holding a meeting to settle their troubles. These tongs began fighting among themselves, and inside of a half-hour there were seven Chinamen lying on the streets wounded; one on Waverly Place, one on Clay Street, two in Spofford Alley, two in Ross Alley, and one on Jackson Street. The one in Waverly Place was shot, the bullet cutting the artery in his arm. Captain Matheson and myself took this Chinaman out of the shop where he fell, and stopped the flow of blood by means of a tourniquet. The physician later told us that if this had not been done the Chinaman would have died.”

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

The alley’s central location in Chinatown also allowed criminal suspects to evade police by moving across the roofs of buildings adjacent to Spofford Alley’s buildings. The following story provides an example of an escape by a tong gunman:

“Police Believe . . . [etc.]” from the San Francisco Call newspaper of September 15, 1899.

The “highbinder headquarters” mentioned in the Call article was probably the Chee Kung Tong, as the rear of its building at 69 Spofford Alley abutted the rear of buildings which fronted on the west side of Waverly Place. Historian Phil Choy wrote about the tong’s headquarters as follows:

“This modest three-story brick building is noted not so much for its architectural design as for its historical significance. In China, Chee Kung Tong was a branch of the Triad Secret Society founded to overthrow the Manchu government (1644-1911) and restore Chinese rule. In California, the Chee Kung Tong degenerated into criminal activities, competing with other secret societies to control prostitution and gambling.”

As San Francisco neared the turn of the century, Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen's Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched Allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society's newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

From the Los Angeles Herald, Number 119, January, 27, 1900. The article provides some support for historian Phil Choy’s conclusion that the Chee Kung Tong had elevated its political agenda over its alleged criminal enterprises, often to the extent that it attempted to broker truces between the fighting tongs of the day. Tong violence in San Francisco, however, would not abate significantly until after 1920.

Spofford Alley also served as the home for the Guanyin Temple (located at teh southwest corner of the intersection of Spofford and Washington Street), which according to Yong Chen (in the book Chinese San Francisco, 1850-1943: A Trans-Pacific Community), “was one of the first Chinese temples in the city. In 1886 numerous Chinese organizations and stores offered money to renovate it.”

What is known about the temple’s interior may be read in an 1892 article by Frederic J. Masters, D.D., about his tour of the “fifteen heathen temples” found in San Francisco’s Chinatown. He described the Guanyin Temple as follows:

“The most popular goddess of the Chinese pantheon is Kwan Yum, the Chinese Notre Dame . . . Her shrine is found up a dingy staircase on the southwest corner of Spofford alley and Washington streets. In this smoky loft, with its rudely carved image and grimy vestments, one sees nothing of the beautifully chiseled statue, that image of repose that we have often seen in the Ocean Banner Monastery, on the banks of the Pearl River. . . .” [海幢寺; mando: Hai-chuang si; canto: “Hoi Duhng See”]