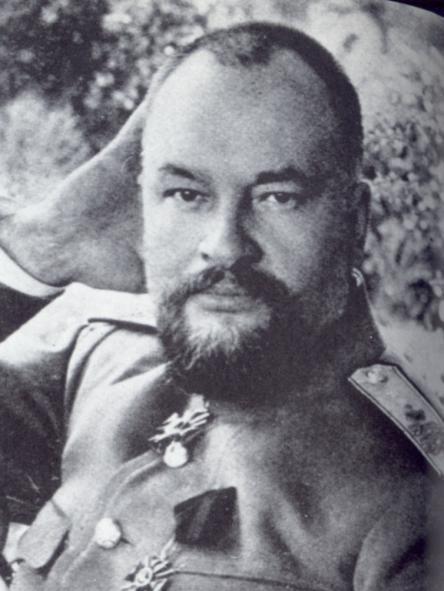

#Eugene Botkin

Note

hi! So I was just rewatching the movie Romanovs an Imperial Family and I noticed that at Tobolsk they (the guards) took pictures of the family (front and side profiles) and I was also just watching Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and I noticed that they also took pictures at Tobolsk. Did this happen in real life or is it just a myth? (If it’s a myth you can put it on the list for your series :)

Thank you!

Hi! Thank you so much for your question lovely! It made me dig a lot deeper into whether this was actually true and I am pleased to say that it isn't a myth, but something that actually happened. Here are some details!

Pierre Gilliard's diary mentions the family having to have identification photos taken. On 17 September 1917 he wrote that "ID cards with numbers, equipped with photographs" were taken of the family. According to Paul Gilbert, who runs the Nicholas II website and has a great article about this, Alix also wrote about this in her diary.

Pierre Gilliard also wrote about this in his memoir Thirteen Years at the Russian Court, Page 286:

In September Commissary Pankratof arrived at Tobolsk, having been sent by Kerensky. He was accompanied by his deputy, Nikolsky—like himself, an old political exile. Pankratof was quite a well-informed man, of gentle character, the typical enlightened fanatic. He made a good impression on the Czar and subsequently became attached to the children. But Nikolsky was a low type, whose conduct was most brutal. Narrow and stubborn, he applied his whole mind to the daily invention of fresh annoyances. Immediately after his arrival he demanded of Colonel Kobylinsky that we should be forced to have our photographs taken. When the latter objected that this was superfluous, since all the soldiers knew us—they were the same as had guarded us at Tsarskoie-Selo—he replied: " It was forced on us in the old days, now it's their turn." It had to be done, and henceforward we had to carry our identity cards with a photograph and identity number."

It's worth mentioning that all the staff that worked at the palace before the Revolution did indeed have to carry ID passes with photographs.

We have a brilliant example of what one of these passes in Tobolsk might have looked like in the form of passes for Botkin and Demidova, which are now Museum of the Family of Emperor Nicholas II in Tobolsk. I sadly couldn't find Demidova's, so have just attached Botkin's.

Captioned: 'Identity card (pass) E. S. Botkin for the right to enter the house number 1 (“Freedom House”) dated November 6, 1917.'

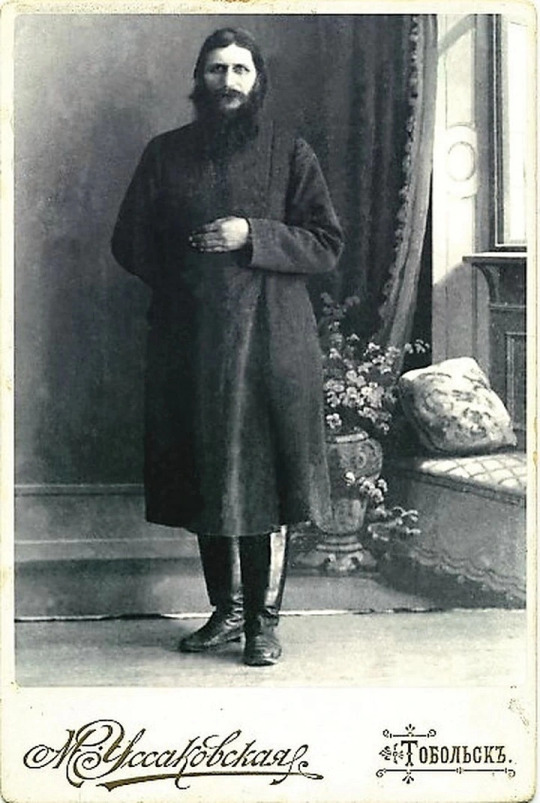

Which brings me on to a lady named Maria Mikhailovna Ussakovskaya. For clarification, I don't know if she was the person who took the photos for definite, but she was a prominent photographer in the area and could have been hired to take the photos. She did 100% have some connection to the Romanov family, as I'll explain later.

Maria was a photographer in Tobolsk, in fact she was the first woman photographer from the region that operated professionally, and she had her own salon. She even photographed Rasputin - you can see her surname embossed on the cabinet card here, reading Уссаковская

She photographed the family's entourage, too, as the staff were able to move freely about Tobolsk. Shown here are (left-right): Catherine 'Trina' Schneider, Count Ilya Tatishchev, Pierre Gilliard, Countess Anastasia 'Nastenka' Hendrikova, and Prince Vasily Dolgorukov. Note Maria's surname embossed again onto the card, showing it was taken and produced at her salon.

Invoices for the family show that the Romanovs had several payments sent to Ussakovskaya for postcards and "correcting negatives", so we know that there definitely was a relationship between the two parties. She took photos of the exterior of the house in Tobolsk, and postcards were sent by the Grand Duchesses showing the house, so they might have used her photos.

Letter sent from Maria to Nikolai Demenkov, her 'crush'

Which then begs the question of what happened to these ID photos...

Apparently, Maria Ussakovskaya's daughter Nina owned some photographic plates of the Romanov family. It's not explained whether these were casual photos taken of the family, or ID photos, but according to Paul Gilbert "in 1938... fearing arrest, [Nina] destroyed all the photographic plates".

Owning any Romanov or Tsarist related items, including photographs and postcards, was an arrestable offence. The rise of the gulags in the 1930s with the Stalinist regime probably prompted Nina to destroy what she owned.

Personally, I don't have much hope that any of the photos of the family will ever turn up. But there is always a small chance, I suppose :)

To conclude: yes, this happened, photos were definitely taken of the family for identification passes. Pierre Gilliard is a trustworthy source and the fact that it was written in his diary and also Alix's diary is pretty much concrete evidence. The existence of Maria Ussakovskaya and her association with the family also points towards this, alongside the bills and invoices sent to the family at Freedom House.

Maria with her husband, Ivan.

SOURCES:

The woman who photographed the Imperial Family in Tobolsk by Paul Gilbert

Thirteen Years at the Russian Court by Pierre Gilliard

#q#ask#answered#OTMA#Romanovs#Romanov family#Tobolsk#Freedom House#Exile#Captivity#Eugene Botkin#Evgeny Botkin#Anna Demidova#Pierre Gilliard#Alexandra Feodorovna#Maria Nikolaevna#sources#Thirteen Years at the Russian Court#my own

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

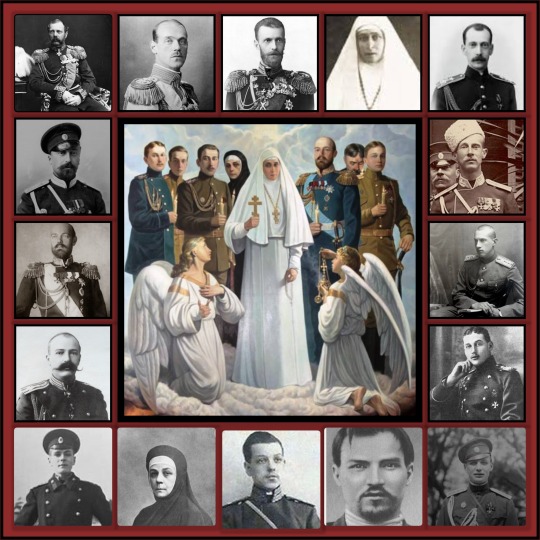

The Romanov Martyrs

I wanted to put together a little memorial that included all the members of the Romanov Family (as well as the members of their staff) that were murdered by the Bolshevik terrorists. This seems like a good week to keep them in our minds. Although we love and mourn the children especially, there were others we cannot forget.

Tsar Alexandre II was hunted down until finally blown to pieces.

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna lost two sons and five grandchildren (no wonder she could not accept they were dead)

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich was also hunted down and blown to pieces

Three Mikhailovichi brothers were murdered

Four Konstantinovichi were murdered, three of them brothers; I cannot imagine what their mother, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Mavrikievna, went through...and so on.

May they rest in peace.

#russian history#imperial russia#romanov family#Nicholas II#Tsar Alexander II#Empress Alexandra Feodorovna#Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna#OTMAA#Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Georgiy Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich#Prince Ioann Konstantinovich#Prince Igor Konstantinovich#Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich#Dr. Eugene Botkin#Anna Demidova#ivan karitonov#Akexei Trupp#Sister Varvara Yakolevna#Feodor Remez#mr. johnson

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

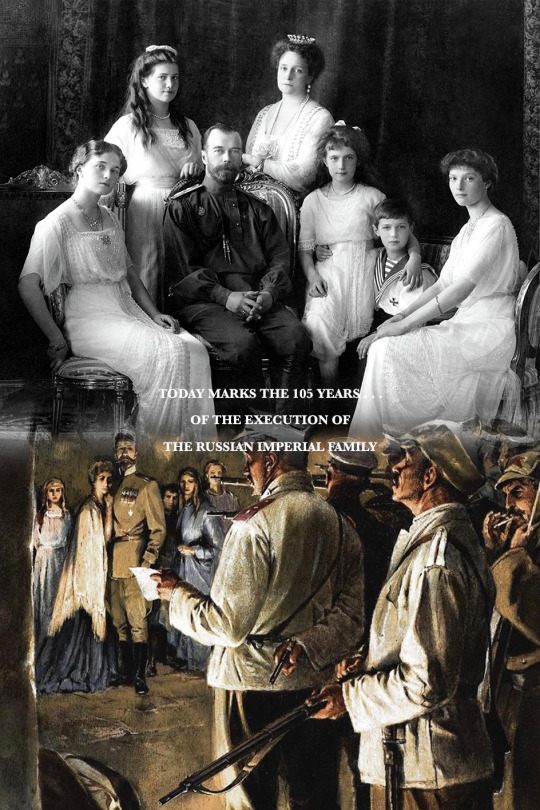

Execution of the Romanov Family

On this day, 105 years ago, the former Emperor of Russia, Nicholas II with his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, their five young children and four of their entourage: court physician Eugene Botkin; lady-in-waiting Anna Demidova; footman Alexei Trupp; and head cook Ivan Kharitonov, were murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House.

#romanovs#history#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#myedits

165 notes

·

View notes

Photo

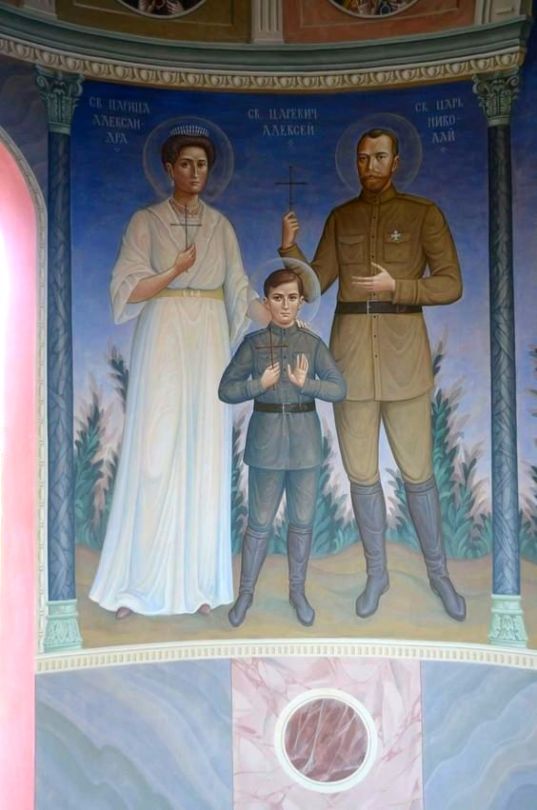

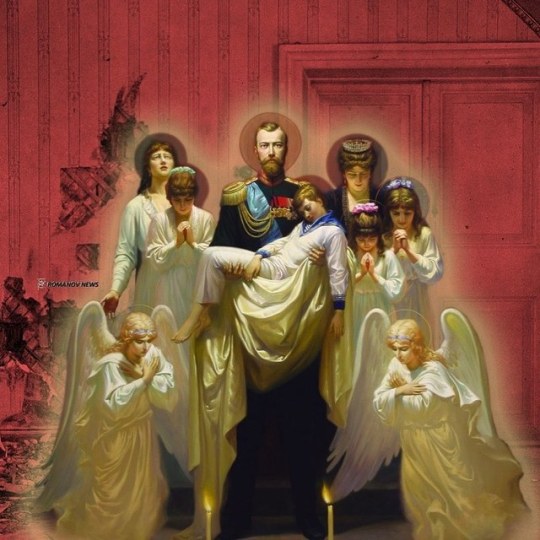

The Romanov martyrs (including doctor Botkin and nun Varvara) as depicted in one of the Orthodox churches

#Russia#Romanov#Nicholas II.#Alexandra Fyodorovna#Olga Nikolaevna#Tatiana Nikolaevna#Maria Nikolaevna#Anastasia Nikolaevna#Alexei Nikolaevich#Elizaveta Fyodorovna#Varvara Yakovleva#Eugene Botkin#icons

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

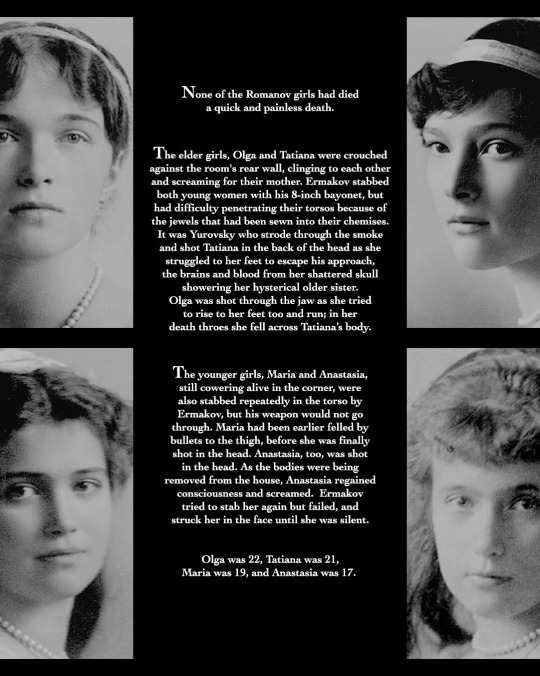

Yurovsky, in 1922, wrote “after checking again to see that all were dead, I ordered the men to start moving them.” The entire executions had taken fewer than ten minutes.

His finger caught the trigger, and, with a flash of smoke and a deafening noise, the first bullet smashed into Nicholas’s chest. “He reeled suddenly,” remembered Andrei Strekotin. In an instant his khaki tunic exploded in blood, as “all ten people firing” took direct aim at their former emperor. “I shot Nicholas,” Yurovsky later wrote, “and everyone else also shot him.” Kudrin, who opened fire the same instant as Yurovsky, squeezed off five rounds in rapid succession, each ripping into Nicholas, who, Strekotin remembered, “stood quivering as shot after shot pierced his body.” Three of these wounds, to the left side of his chest, were, in and of themselves, fatal, tearing through Nicholas’s rib cage, into the pericardial cavity, into his heart, and exiting out his back. With “wide, vacant eyes,” Alexei Kabanov recalled, “Nicholas lurched forward and toppled to the floor.”

***********

With the first shot, Trupp turned from the execution squad toward the northeastern corner of the room; two bullets, fired in rapid sucession, struck his left thigh, shattering his femur and breaking his leg. Unable to stand, Trupp crumpled to his knees; seeing him beneath the thick layer of smoke, one of the executioners in the first row took aim, firing a bullet into the right side of his head. Smashing through his skull, it killed him instantly.

***********

Kharitonov, standing against the northern wall, was hit with several bullets at once, the force so powerful, Yurovsky recalled, that he “sat down and died.”

***********

Drunk and consumed with his own lust for blood, Ermakoy turned from Nicholas to Alexandra, who, he recalled, stood “only six feet away.” He raised his Mauser as she turned her head away and began to cross herself; but before she could finish, as Andrei Strekotin recalled, he pulled the trigger. A bullet slammed into the left side of her skull, a spray of blood and brain tissue exploding from her right ear as the force drove her violently back, knocking her onto the floor.

***********

When Yurovsky entered the room, he saw Botkin, covered in blood, leaning on his right arm as he tried to raise himself from the floor. He stepped across the pile of blood spreading from the emperor’s body, held his Mauser close to Botkin’s head, and pulled the trigger. The bullet ripped through the doctor’s head, exiting out the lower right side of his skull, its force slamming his body against the floor in a shower of gore.

***********

Yurovsky fired the last bullets from his Mauser directly into the tsesarevich, who slowly slipped from his chair and crumpled to the floor. Paul Medvedev, who had staggered back into the room, saw Alexei on the floor, “moaning and alive.” Out of bullets, Yurovsky yelled to Ermakov, who turned back to the center of the room, pulling and eight-inch triangular bayonet from his belt as he stumbled over the growing pile of arms and legs. Crouched on the floor, he raised the knife; over and over, the glint of steel flashed in the dim electric light as he stabbed the supine boy, blood flying from the blade with each arc and seeping across the once-yellow floorboards. Yurovsky watched in horror as Alexei struggled against the powerful, wild Ermakov: “nothing seemed to work,” Yurovsky wrote. “Though injured, he continued to live.” None of the assassins knew that, beneath his tunic, the tsesarevich wore a shirt wrapped with jewels, which shielded his torso from both bullets and Ermakov’s bayonet. Finally, “unable to stand by,” Yurovsky pulled his second gun, a colt, from his belt, pushed Ermakov aside, and first two shots into the boy.

***********

Yurovsky, standing behind Tatiana, aimed his Colt and fired. The bullet tore into the rear of her head; it ripped through her skull instantly, blowing out the right side of her face in “a shower of blood and brains” that covered her screaming sister.

***********

In an instant, Ermakov, “wild-eyed and face splattered with blood,” moved forward. As Olga tried to rise, he violently kicked her back, sending her spinning toward the floor; at the same time he squeezed the trigger of his Nagant revolver. With a flash of smoke, the bullet caught her as she fell, just beneath her chin, breaking her jaw as it seared through her skull, lacerating her brain before smashing through the top of her forehead. In a second, she toppled across her sister, dead.

***********

Hearing their terrified screams, Ermakov turned from the lifeless body of their eldest sister, rounding on them with his blood-stained bayonet. Kabanov watched as he grabbed Marie, “stabbing her in the chest over and over again.” Yurovsky looked on in horror as Ermakov attacked her, but “the bayonet would not pierce her bodice.” She was, Yurovsky wrote, “finished off” with a shot to the head.

***********

Anastasia had backed into the corner next to the storeroom door. Ermakov turned on her, slashing frenziedly “through the air” as he approached. Drunk and crazed, he struck the pier, his bayonet slicing deeply into the plaster, before drawing back the blade and plunging it into Anastasia’s chest as she struggled to fend him off. In an increasing spiral of savagery, he swung his knife repeatedly, unable to penetrate her bodice. “Screaming and fighting,” Yurovsky wrote, she fell only after Ermakov put his gun to her head and pulled the trigger.

***********

Yurovsky and Ermakov had reached the open door to the corridor when, as Kudrin recalled, “something white moved in the corner.” It was Anna Demidova, who had fallen in a faint after being shot in the leg. ‘Thank God!“ she screamed. "God has saved me!” She tried to get to her feet, but Ermakov, bayonet held high, reached her, swinging out in delirium. “She grabbed it with her hands,” Kabanov remembered, “screaming and crying.” With her hands sliced to ribbons and unable to defend herself, finally she, too, fell still.

The Fate of the Romanovs - Greg King and Penny Wilson

#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#Anastasia nikolaevna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#TW: gore#tw: blood#tw: death#tw: violence#alexei trupp#eugene botkin#anna demidova#ivan kharitonov#long live the queue

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

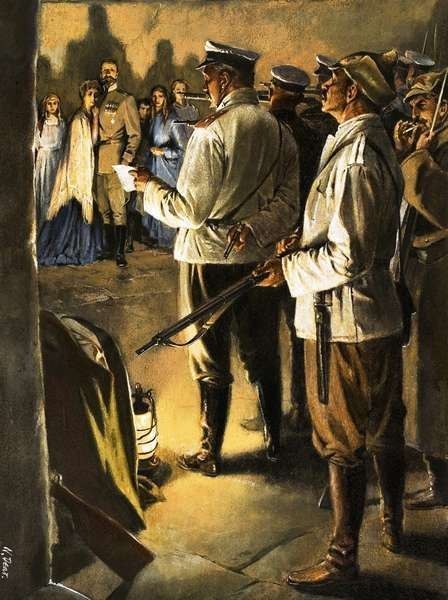

Painting depicting Emperor Nicholas II of Russia with his family and servants who were assassinated in Yekaterinburg in 1918.

#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#eugene botkin#alexei trupp#ivan kharitonov#anna demidova#romanov#russia#royalty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

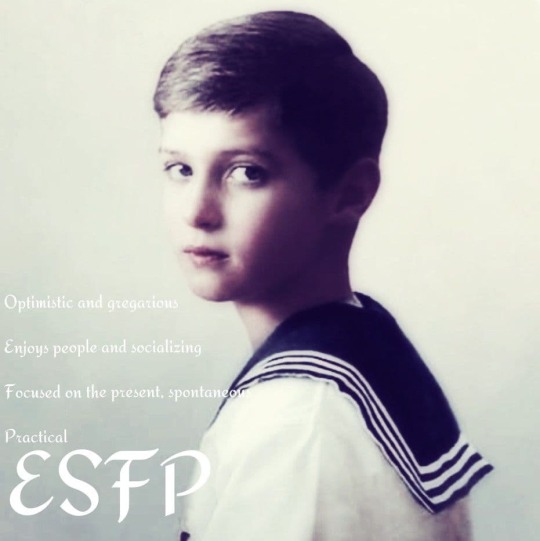

Tsarevich Aleksei Nikolaevich

Alexei was a handsome boy, and he bore a striking resemblance to his mother. His tutor Pierre Gilliard described the 18-month-old Alexei as "one of the handsomest babies one could imagine, with his lovely fair curls and his great blue-grey eyes under their fringe of long curling lashes". A few years later, Gilliard described Alexei as tall for his age, with "a long, finely chiseled face, delicate features, auburn hair with a coppery glint, and large grey-blue eyes like his mother". Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, his mother's lady-in-waiting, reflected that "he was a pretty child, tall for his age, with regular features, splendid dark blue eyes with a spark of mischief in them, brown hair, and an uptight figure".

Alexei was proud of and enjoyed his position as tsarevich. Buxhoeveden reflected that "he knew and felt that he was the Tsarevich, and from babyhood mechanically took his place in front of his elder sisters". He liked being kissed on the hand by the officers and "didn't miss his chance to boast about it and give himself airs in front of his sisters". He enjoyed jumping in front of the guards at the front of the Alexander Palace, who would immediately salute him as he walked past. Nicholas forbade the guards to salute Alexei unless another member of the family accompanied him. Alexei was embarrassed "when the salute failed him", which "marked his first taste of discipline". On one occasion, he ordered all of the Finnish officers on various ships to stand before him on the deck of the Standart. He began commanding them, but the Finnish officers did not understand Russian and stood in confusion until an aide informed them that Alexei wanted to hear them say, "We wish you health, your Imperial Highness." When he was told that a group of officers had arrived to call on him, the 6-year-old Alexei told his sisters, "Now girls, run away. I am busy. Someone has just called to see me on business."

Alexei's parents indulged his tantrums and mischievous behavior, and they rarely punished him. In 1906, Alexei and his family went on a cruise to Finland. In the middle of the night, the 2-year-old Alexei commanded the ship's band to wake up and play for him. Instead of punishing Alexei, Nicholas joked "that's the way to bring up an autocrat!" Nicholas called Alexei "Alexei the Terrible."

Alexei loved to attend army inspections with his father. When he was 3, he wore a miniature army uniform and played with a toy wooden rifle.From birth, he had the title of "Hetman of all the Cossacks." He wore a miniature uniform of a sailor of the Russian navy, and he had his own Cossack uniform with a fur cap, boots, and dagger. He ended his daily prayers with "Hurrah!" instead of "amen". When asked why, he replied that the soldiers on parade always said "Hurrah!" when his father finished speaking, so he should greet his Heavenly Father in the same way. Before he understood the nature of his disease, he said that he wanted to be a warrior-tsar and lead armies as his ancestors had.

Alexei resented that he was forbidden from doing what other boys could do because of his hemophilia. When his mother forbade him to ride a bike and play tennis, he asked angrily, "Why can other boys have everything and I nothing?" All four of his sisters were accomplished horsewomen, but he was forbidden from horseriding.

Alexei had few friends his age and was often lonely. Alexandra did not allow Alexei to play with his Romanov cousins because she was worried that they would knock him down when playing and he might bleed. Alexei's companions were his sailor-nanny Derevenko's two young sons. Derevenko watched them as they played, and he chastised his children if they played too roughly with Alexei.

Alexei was close with his sisters. Gilliard wrote that they "brought into his life an element of youthful merriment that otherwise would have been sorely missed".

Despite the hemophilia, Alexei was adventurous and restless. Doctor Eugene Botkin's children noticed Alexei's inability to "stay in any place or at any game for any length of time". When he was 7, he stole a bicycle and rode it around the palace. Shocked, Nicholas ordered every guard to pursue and capture Alexei. At a children's party, Alexei began jumping from table to table. When Derevenko tried to stop him, Alexei shouted, "All grown-ups have to go!" Recognizing Alexei's energetic nature, Nicholas ordered that Alexei be allowed "to do everything that other children of his age were wont to do, and not to restrain him unless it was absolutely necessary".

Alexei was disobedient and difficult to control. Olga could not manage Alexei's "peevish temper". The only person he obeyed was his father. Sydney Gibbes noted that "one word [from Nicholas] was always enough to exact implicit obedience from [Alexei]". Buxhoeveden remembered that Alexei had once thrown her parasol in the river, and Nicholas had chastised Alexei: "That is not the way for a gentleman to behave to a lady. I am ashamed of you, Alexei." After his father scolded him, Alexei was "scarlet in the face" and apologized to Sophie.

As a small child, Alexei occasionally played pranks on guests. At a formal dinner party, Alexei removed the shoe of a female guest from under the table, and showed it to his father. Nicholas sternly told the boy to return the "trophy", which Alexei did after placing a large ripe strawberry into the toe of the shoe.

As he grew up, Alexei became more thoughtful and considerate. When he was 9, he sent a collection of his favorite jingles to Gleb Botkin, Eugene Botkin's son. He asked Gleb, who was talented at drawing, to illustrate the jingles. He attached a note: "To illustrate and write the jingles under the drawings. Alexei." Before handing the note to Eugene Botkin, he crossed out his signature and explained, "If I send that paper to Gleb with my signature on it, then it would be an order which Gleb would have to obey. But I mean it only as a request and he doesn't have to do it if he doesn't want to."

Alexei enjoyed playing the balalaika.

Alexei's favorite pet was a spaniel named Joy. Nicholas gave Alexei an old performing donkey named Vanka. Alexei gave sugar cubes to Vanka, and Vanka pulled Alexei around the park in a sled during the winter.

According to Gilliard, Alexei was a simple, affectionate child, but the court spoiled him by the "servile flattery" of the servants and "silly adulations" of the people around him. Once, a deputation of peasants came to bring presents to Alexei. Derevenko required that they kneel before Alexei. Gilliard remarked that the Tsarevich was "embarrassed and blushed violently", and when asked if he liked seeing people on their knees before him, he said, "Oh no, but Derevenko says it must be so!" When Gilliard encouraged Alexei to "stop Derevenko insisting on it", he said that he "dare not". When Gilliard took the matter up with Derevenko, he said that Alexei was "delighted to be freed from this irksome formality".

"Alexei was the center of this united family, the focus of all its hopes and affections", wrote Gilliard. "His sisters worshipped him. He was his parents' pride and joy. When he was well, the palace was transformed. Everyone and everything in it seemed bathed in sunshine."

Gilliard eventually convinced Alexei's parents that granting the boy greater autonomy would help him develop better self-control. Alexei took advantage of his unaccustomed freedom, and began to outgrow some of his earlier foibles. Courtiers reported that his illness made him sensitive to the hurts of others.

Due to his disease, Alexei understood that he might not live to adulthood. When he was ten, his older sister Olga found him lying on his back looking at the clouds and asked him what he was doing. "I like to think and wonder", Alexei replied. Olga asked him what he liked to think about. "Oh, so many things", the boy responded. "I enjoy the sun and the beauty of summer as long as I can. Who knows whether one of these days I shall not be prevented from doing it?"

Nicholas' Colonel Mordinov remembered Alexei:

He had what we Russians usually call "a golden heart". He easily felt an attachment to people, he liked them and tried to do his best to help them, especially when it seemed to him that someone was unjustly hurt. His love, like that of his parents, was based mainly on pity. Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich was an awfully lazy, but very capable boy (I think, he was lazy precisely because he was capable), he easily grasped everything, he was thoughtful and keen beyond his years ... Despite his good nature and compassion, he undoubtedly promised to possess a firm and independent character in the future.

NOTE: Aleksei, a wonderful boy! So intelligent, bright and friendly! Rest in Peace Our Dear Tsarevich!

#romanov mbti#alexei romanov mbti#alexei nikolaevich#tsarevich alexei#aleksei romanov#alexei romanov#romanov#the romanovs#otma#imperial russia#russia#otmaa#edit#my edit#romanov edit

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

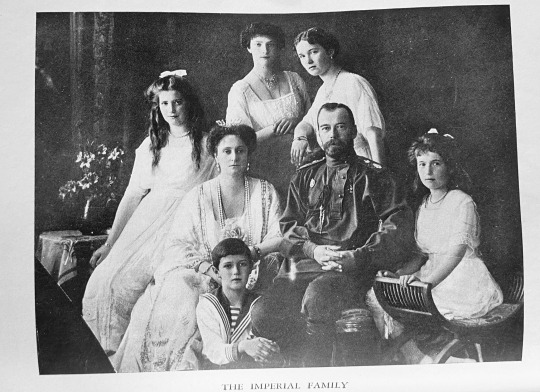

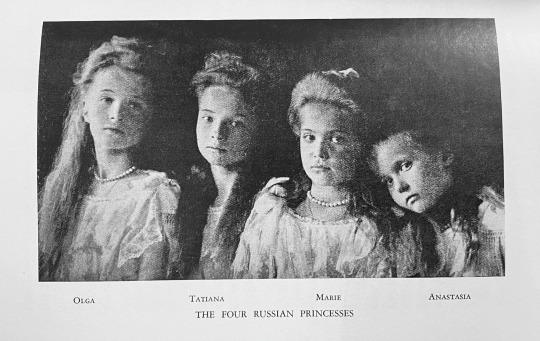

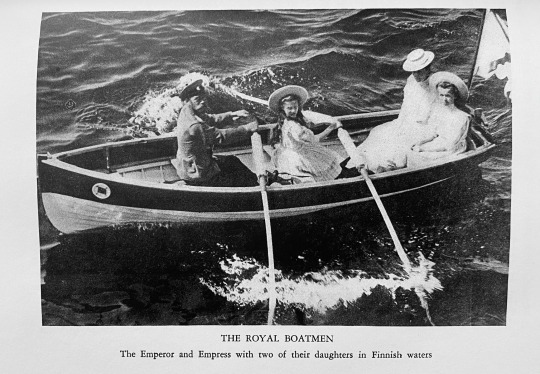

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his family as featured in Gleb Botkin’s The Real Romanovs (1931).

Gleb Botkin was the son of Dr. Eugene Botkin, who was the court physician for Nicholas and his family from 1908 to 1918. Dr. Botkin was close with both the Tsar and the Tsarina, and traveled with them to Yekaterinburg, where they were all executed on July 17, 1918. Gleb and his sister grew up alongside the imperial children, often playing together during the holidays. After the revolution, the two siblings fled to Siberia and Japan before settling in the United States in 1922. Gleb became acquainted with Anna Anderson, the most notorious of the Romanov impostors, in Germany in 1927. He recognized her as the Grand Duchess Anastasia, and became a fervent supporter of her claim for the rest of his life. He authored many novels and articles, including The Real Romanovs, and corresponded with the remaining Romanovs about “Anastasia.” Gleb, along with Princess Xenia Georgievna, paid for Anna to travel to France and the United States in 1928. Later that year, Nicholas II’s mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, died in her native Denmark. At her funeral in Copenhagen, many of the most prominent members of the family gathered to sign the “Copenhagen Statement,” which was a joint rejection of Anna’s claim. She lived in a state of tumultuous, on-and-off luxury and squalor in Europe from the 1930s to the 1960s. In 1968, Gleb and his friend John Manahan funded her journey to the United States. The three lived near one another in Charlottesville, Virginia. Anna and John were wed later that year, with Gleb as the best man. Gleb died the following year, and Anna passed in 1984. After her death, the remains of the Imperial Family were tested with Anderson’s DNA, proving once and for all that Anna was not the Grand Duchess Anastasia.

(I took these pictures myself! I have a copy of the original print of this book from 1931. These photographs are widely available on the internet, but I don’t believe the third one is very common. The two Grand Duchesses pictured are Olga and Tatiana.)

#grand duchess olga nikolaevna#grand duchess tatiana#grand duchess maria nikolaevna#grand duchess anastasia#tsarevich alexei#empress alexandra feodorovna#tsar nicholas ii#history#russia#royalty#gleb botkin

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

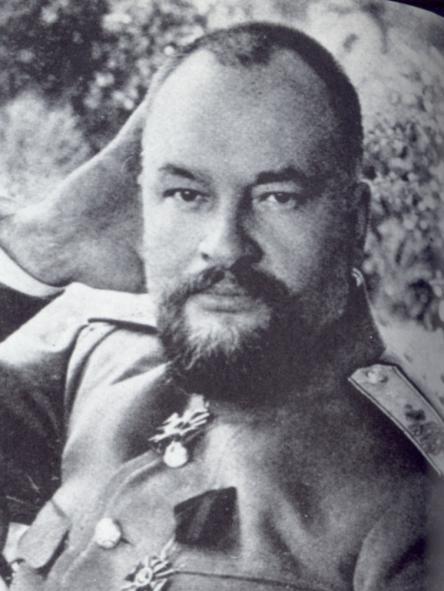

Eugene Botkin, 1916. Below is his last ever letter, written not long before he was murdered along with the Russian Imperial Family and three other servants on the 17th July 1918. Dr Botkin started this letter on 9th July 1918 but continued writing it on 17th July, when he heard the knock on his door, which was why letter ended abruptly. It was never finished or mailed. The letter was meant for his brother Alexander

“My dear, good friend Sasha, I am making the last attempt to write a real letter, - at least from here, - although this caveat is completely redundant; I do not think that it is in the cards for me to ever write from anywhere else again, - my voluntary imprisonment here is limited to my existence on this earth. In actuality, I have died – dead to my children, my friends, my work… I have died, but have not been buried yet, or rather was buried alive, - whichever you prefer: the consequences are almost identical, i.e. both one and the other have their negative and positive sides.

If I were literally dead, that is to say, anatomically dead, then according to my faith I would know what my children are doing, would be closer to them and undoubtedly more useful than now. I rest with the dead only civilly, my children may still have hope that we will see each other sometime in this life, while I, other than thinking that I can still be useful to them somehow, do not personally indulge myself with this hope, do not humour myself with illusions, but look directly into the face of unadorned reality.

Although for now, I am as healthy and fat as always, to a point where I feel disgusted every time I look in the mirror. I only console myself with the thought that if it would be easier for me to be anatomically dead, then this means that my children are better off, because when I am separated from them, it always seems to me that the worse off I am, the better off they are. And why do I feel that I would be better off dead, - I will explain this to you with small episodes, which illustrate my emotional being.

The other day, i.e. three days ago, when I was peacefully reading Saltykov-Schedrin, which I often read with pleasure, I suddenly saw the face of my son Yura in diminutive size, as if from far away, but [it was] dead, in a horizontal position, with closed eyes… The last letter from him was on 22 March o[ld] s[tyle], and since that time postal connection from the Caucasus, which even earlier faced great difficulties, probably stopped completely, as neither here nor in Tobolsk had we received anything else from Yura.

Do not think that I am hallucinating, I have had these types of visions before, but you can easily imagine, how it was for me to experience this particular thing in the current situation, which in general is quite comfortable, but to have no chance not only to go to Yura, but not even to be able to find out anything about him. Then, only yesterday, during the same reading, I suddenly heard some word, which to me sounded like ‘Papulya’, which was uttered in Tanyusha’s [his daughter Tatiana] voice, and I almost broke down in sobs.

Again, this was not a hallucination, because this word was uttered, the voice was similar, and not even for a second did I think that this was my daughter speaking, who was supposed to be in Tobolsk: her last postcard was from 23 May – 5 June, and of course these tears would have been purely egotistical, for myself, that I cannot hear and, most likely will never again hear that dear little voice and feel that affection that is so important to me, with which my little children spoiled me so. Again, the horror and sorrow which gripped me during the vision I described were purely egotistical too, since if my son had truly died, then he is happy, but if he is alive, then it is unknown what kind of trials he is going through or is fated to live through. So you see, my dear, that my spirit is cheerful, despite the torment I live through, which I bear, just described to you, and cheerful to a point where I am prepared to do this for many more years…

I am encouraged by the conviction that ‘one who bears all until the end is saved’, and the awareness that I remain loyal to the principles of the 1889 graduates. Before we graduated, while still students, but already close friends who preached and developed the same principals with which we started life, for the most part we did not view them from a religious point of view, I do not even know if too many of us were religious. But each codex of principals is a religion already, and for some it is most likely a conscious thing, while for others subconscious, - as it basically was for me, as this was the time of, not exactly uniform atheism, but of complete indifferentism, in the full sense of the word, - it came so close to Christianity that our full attitude toward it, or at least of many of us, was a completely natural transition. In general, if ‘faith is dead without work’, then ‘work’ cannot exist without faith, and if faith joins any of our work, then this is just due to special favour from God.

I turned out to be such a lucky one, through the path of heavy trials – the loss of my firstborn, the year-and-a-half-old little son Seryozha. Since that time, my codex has been widened and solidified significantly, and I took care that each task was not only about the ‘Academic’, but about the ‘Divine’. This justifies my last decision as well, when without any hesitation I left my children completely orphaned, in order to do my physician’s duty to the end, like Abraham did not hesitate to sacrifice his only son to God on His demand.

I strongly believe that the same way God saved Isaac, He will save my children too and be a father to them. But since I do not know how He will save them, and can only find out about it in the next world, my egotistic torment which I described to you, due to my human weakness, does not lose its torturous severity. But Job did bear more, and my late Misha always reminded me about him, when he was afraid that I, bereft of my dear little children, would not be able to bear it.

No, apparently I can bear it all, whatever God wills to burden me with. In your letter, for which I ardently thank you once more (the first time I tried to convey this in a few lines on a detachable coupon, hopefully you got it in time for the holiday, and also my physiognomy – for the other?), you were interested in my activities in Tobolsk, with a trust precious to me. And so? Putting hand on heart, I can confess to you that there, I tried in every way to take care of ‘the Divine, as the Lord wills’ and, consequently, ‘not to shame the graduates of year 1889′. And God blessed my efforts, and I will have until the end of my days this bright memory of my swan song.

I worked with my last strength, which suddenly grew over there thanks to the great happiness in the life [we had] together with Tanyusha and Glebushka [his son Gleb], thanks to the nice and cheerful climate and relative mildness of winter and thanks to the touching attitude towards me from the townspeople and villagers. As a matter of fact, in its center, albeit a large one, Tobolsk presents as a city that is very picturesquely located, rich with ancient churches, religious and academic institutions, [but] at the periphery it gradually and unnoticeably transitions into a real village. This circumstance, along with noble simplicity and the feeling of self-respect of Siberians, in my opinion gives the relationships among the residents and not visitors, the specific character of directness, naiveté and benevolence, which we always valued and which creates the atmosphere necessary to our souls.

In addition, various news spreads around the city very fast, the first lucky incidents for which God helped me be of use brought out such trust towards me, that the number of those wanting to get my advice grew with each day, up to my sudden and unexpected departure. Turning to me were mostly those with chronic illnesses, those who were already treated again and again, [and] sometimes, of course, those who were completely hopeless. This gave me the opportunity to make appointments for them, and my time was filled for a week or two ahead in each hour, as I was not able to visit more than six - seven, in extreme cases eight patients per day: since all these cases needed thorough review and much and much pondering.

Who was I called to besides those ill within my specialty?! To the insane, to those asking to be treated for drunkenness; [they] brought me to a prison to see a kleptomaniac, and with sincere joy I remember that the poor wretch of a lad, who was bailed out by his parents on my advice (they are peasants), behaved decently the rest of my stay… I never denied anyone, as long as the supplicants accepted that certain illnesses were completely beyond the limits of my knowledge. I only refused to go to those recently fallen ill if, of course, they needed emergency help, since, on the one hand I did not want to get in the way of regular physicians of Tobolsk, which is very lucky to have them in the capacity and most importantly, quality of relations.

They are all very knowledgeable and experienced people, excellent comrades and so responsive that the Tobolsk public is used to sending a horse or cabby to the doctor and receive him immediately. More valuable is their patience towards me, who did not have the ability to fulfill these types of requests, but on the contrary, was forced to make them wait a long time. It’s true that soon it became commonly known that I never refuse anyone and keep my word sacredly, a patient could wait for me with peace of mind.

But if their illness did not allow them to wait, then the patients went to local physicians, which always made me happy, or to Doctor Derevenko, who also possessed their vast trust, or they headed to the hospital, and this way it would happen that when I arrived at a time of prescheduled appointment, I did not find the patient there, but that was always convenient, since most of the time my schedule was so extensive that I wasn’t able to accomplish everything, at times debts formed, which I paid off when I did not find someone there.

To see [patients] at the house where I was staying was inconvenient, and anyway there was no room, nevertheless from 3 until 4 ½ - 5, I was always home for our soldiers, whom I saw in my room, the walk-through room, but since only our own [people] passed though there, it did not discomfort them. During the same hours, my town patients came to see me too, either for a refill of a prescription or to make an appointment. I was forced to make exceptions for peasants who came to see me from villages tens or even hundreds of versts away (in Siberia they don’t pay attention to distance), and who were in a hurry to get back. I had to see them in a small room before the bathroom, which was a bit out of the way, where a large chest served as an examining table.

Their trust was especially touching to me, and their confidence, which never betrayed them, that I will treat them with the same attention and affection as any other patient, not only as an equal but as a patient who has every right to my care and services, gave me joy. Those who were able to spend the night, I would visit at the inn early the next morning. They always tried to pay, but since I followed our old codex, of course I never accepted anything from them, so, while I was busy in an izba with a patient, they hurried to pay my cabby. This surprising courtesy, to which we are not used to at all in large cities, was occasionally highly pertinent, as at times I was not in a position to visit patients due to lack of funds and fast-growing cab costs.

Therefore, for our mutual benefit, I widely took advantage of another local tradition and asked those who had a horse, to send it for me. This way, the streets of Tobolsk saw me riding in wide bishop’s sleighs, as well as behind beautiful merchant trotters, but most often drowning in hay in most ordinary burlap. My friends were equally varied, which perhaps was not to everyone’s liking, but it was no concern of mine. To Tobolsk’s credit I must add that there was no direct evidence of this at all, and only one indirect, which in addition was not unquestionable.

One evening the husband of one of my female patients came to see me with a request to visit her right away, because she had strong pains (in the stomach). Luckily, I was able to fulfill his wish, albeit at a cost to another patient, for whom I did not schedule a visit, but rode with him to his house in a cab in which he came to get me. On the way he starts to grumble at the cabby, that he is not going the right way, to which the latter reasonably respon [letter ends abruptly].”

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE EXECUTION OF THE ROMANOV IMPERIAL FAMILY: Around midnight on 17 July, 1918, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of The House of Special (Ipatiev House) Purpose, ordered the Romanovs' physician, Dr. Eugene Botkin, to awaken the sleeping family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Yekaterinburg. The Romanovs were then ordered into a 6m × 5m (20ft × 16ft) semi-basement room. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat. Yurovsky's assistant Grigory Nikulin remarked to him that the "heir wanted to die in a chair. Very well then, let him have one." The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given to him by the Ural Executive Committee. Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said: "What, What?" Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised. The Empress and the Grand Duchess Olga, according to a guard's reminiscence, had tried to bless themselves, but failed amid the shooting. Yurovsky reportedly raised his Colt gun at Nicholas's torso and fired. Nicholas fell dead, pierced with at least three bullets in his upper chest. The other executioners began to shoot chaotically until all the victims had fallen. The last to be killed were Alexei and Anna Demidova, the lady-in-waiting of Tsarina Alexandra.

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I am making a last attempt at writing a real letter--at least from here--although that qualification, I believe, is utterly superfluous. I do not think that I was fated at any time to write to anyone from anywhere.

My voluntary confinement here is restricted less by time than by my earthly existence. In essence I am dead--dead for my children--dead for my work ... I am dead but not yet buried, or buried alive--whichever, the consequences are nearly identical...

The day before yesterday, as I was calmly reading ... I saw a reduced vision of my son Yuri's face, but dead, in a horizontal position, his eyes closed.

Yesterday, at the same reading, I suddenly heard a word that sounded like "Papulya". I nearly burst into sobs. Again--this is not a hallucination because the word was pronounced, the voice was similar, and I did not doubt for an instant that my daughter, who was supposed to be in Tobolsk, was talking to me...

I will probably never hear that voice so dear or feel that touch so dear with which my little children so spoiled me...

If faith without works is dead, then deeds can live without faith and if some of us have deeds and faith together, that is only by the special grace of God. I became one of these lucky ones through a heavy burden--the loss of my first born, six-month old Serzhi.

This vindicates my last decision...when I unhesitatingly orphaned my own children in order to carry out my physician's duty to the end, as Abraham did not hesitate at God's demand to sacrifice his only son.

Dr. Eugene Botkin’s unfinished letter to his brother Alexander, written the night before his murder with the Romanov family

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Tsarevich Alexei pulling? The weight of Russia, perhaps?

As a baby, the little Tsarevich was simply beautiful (the photos speak for themselves.) At fourteen, his mother's lady-in-waiting, Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, described him as "...a pretty child, tall for his age, with regular features, splendid dark blue eyes with a spark of mischief in them, brown hair, and an upright figure".

He was adventurous and restless by nature. Doctor Eugene Botkin's children noticed Alexei's inability to "stay in any place or at any game for any length of time." He could be difficult to control. Olga could not manage his temper (he once slapped her.) The only person he obeyed was his father. As he grew up, he developed a more mature and thoughtful side.

If he would have been healthy and Russia in a less turbulent phase of its growth, It is not difficult to imagine him as a dynamic, strong-handed Tsar executing many projects at once. Maybe he would have been the one to finish bringing Russia into Europe and the 20th century.

#russian history#romanov dynasty#imperial russia#naotma#Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich#vintage photography

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the early hours of 17th July 1918, the entire Imperial Family along with their servants, were brutally murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House.

Around midnight, Yakov Yurovsky ordered the family physician, Eugene Botkin, to awaken the family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Ekaterinburg. They were led in the semi-darkness steep, narrow stairs to the ground floor. Instinctively the Romanovs followed the order of precedence instilled in them, the Tsar in front but refusing assistance as he struggled with the burden of Alexei, who winced with pain from his bandaged leg; then Alexandra leaning heavily on Olga’s arm, followed by Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia. As they made their way to the stairs, the family paused and devoutly crossed themselves at the stuffed mother bear and her cubs that stood on the landing — a sign of respect for the dead, thinking as they did that they were going to be leaving the house.

Following the family came Dr Botkin, Alexei Trupp (Tsar’s footman), Anna Demidova (Tsarina’s maid), and Ivan Kharitonov (the family’s cook). They all exited the house, re-entering by another, adjacent door leading down into the basement. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat. Yurovsky's assistant Grigory Nikulin remarked to him that the "heir wanted to die in a chair. Very well then, let him have one."

The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given to him by the Ural Executive Committee:

“Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.”

Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said "What? What?" Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised.

#romanovs#history#royalty#myedits#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#otma#alexei nikolaevich#tsarevich alexei#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#imperial russia

988 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remember these victims:

Many have heard of the Romanov execution. However, surprisingly very few known that it was not just the Romanovs were killed on the night of July 17, 1918.

These are the forgotten victims. They were royal followers and friends of the Romanov family, who willingly joined them in exile.

Ivan Kharitonov, a cook for the Romanov family.

Ivan with his wife and daughter went into exile with the Romanov family.However, his family did not go with him to Ekaterinburg.

He was canonized as a passion-bearer in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Alexei Trupp, a footman in the Romanov household

Not much is known about Trupp. Many believe he went into exile with the Romanovs willingly. For he saw the family as friends.

He was canonized a martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church, despite not practicing the faith.

Anna Demidova, a maid who served mostly for Alexandra.

It is said she was the last to die. When the soldiers pulled their guns out, she fainted. After she awoke it is said she screamed:

“Thank God! God has saved me!”

At that moment the soldiers turned on her. Unlike the others Anna did not die from a bullet. Instead she was stabbed to death.

She was canonized as a martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Eugene Botkin, a court physician.

Botkin was hired to help treat Alexei’s hemophilia. At the time of his death, he was divorced with four children. Two of his children died in the First World War. His wife divorced him because of his loyalty to the Romanovs.

He considered the Romanovs not just friends, but also family. When the family went into exile, he saw it as a personal duty to join them.

He was canonized as a martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Nicholas Alexandrovich,” he said to the Emperor, “your relatives are trying to save you; therefore we are compelled to shoot you!”

“What?” Nicholas asked.

“This is what!” Yurovsky said, ordering his men to open fire. As the shots rang out there were “loud cries” and screams. “Death had been instantaneous,” reported Robert Wilton, for Nicholas, Alexandra, the three oldest grand duchesses, Botkin, Kharitonov, and Trupp. Alexei, said guard Paul Medvedev, “was still alive and moaned. Yurovsky went up and fired two or three ore shots at him. The heir grew still.” Anastasia, still alive, “rolled about and screamed,” Wilton wrote, “and, when one of the murderers approached, fought desperately with him till he killed her.” She finally fell, “pierced by bayonets.” Demidova was the last to die. The soldiers grabbed rifles from the corridor, chasing her back and forth across the rear of the cellar room and repeatedly stabbing her with bayonets as she screamed in vain. All of the Romanovs, remembered Medvedev, were “on the floor, with many wounds on their bodies. The blood was running in streams.”

The Resurrection of the Romanovs - Greg King & Penny Wilson

#romanov#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#anastasia nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#olga nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#anna demidova#alexei trupp#eugene botkin#Ivan Kharitonov#long live the queue

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

RS Notícias: Execução da família Romanov - História virtual - https://www.rsnoticias.top/2021/07/execucao-da-familia-romanov-historia.html

RS Notícias: Execução da família Romanov – História virtual – https://www.rsnoticias.top/2021/07/execucao-da-familia-romanov-historia.html

Os Romanov. Da esquerda para direita: Olga, Maria, Nicolau II, Alexandra, Anastásia, Alexei, e Tatiana. Retratados no Palácio de Livadia em 1913.

A família imperial russa dos Romanov (czar Nicolau II, sua esposa a czarina Alexandra e seus cinco filhos Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastásia, e Alexei) e todos aqueles que escolheram acompanhá-los no exílio – nomeadamente Eugene Botkin, Anna…

View On WordPress

0 notes